Summary

The government of Azerbaijan continues to wage a vicious crackdown on critics and dissenting voices. The space for independent activism, critical journalism, and opposition political activity has been virtually extinguished by the arrests and convictions of many activists, human rights defenders, and journalists, as well as by laws and regulations restricting the activities of independent groups and their ability to secure funding. Independent civil society in Azerbaijan is struggling to survive.

In late 2015 and early 2016 the authorities conditionally released or pardoned a number of individuals previously convicted on politically motivated charges, including several high-profile figures whose arrests and convictions had drawn vocal criticism from governments, intergovernmental organizations and nongovernmental groups (NGOs). Many have sought to frame the releases as an indication of a shift in the government’s punitive attitude towards independent civil society activists and groups.

However, even as the government released some activists, bloggers, and journalists, authorities have arrested many others on spurious criminal and administrative charges to prevent them from carrying out their legitimate work. None of those released had their convictions vacated, several face travel restrictions, others left the country fearing further politically motivated persecution, or had to halt their work due to almost insurmountable bureaucratic hurdles hampering their access to funding. Authorities have also harassed the relatives of those attempting to carry out their activism from abroad, in some cases by bringing criminal charges against them. Numerous lawyers representing government critics in legal proceedings have been disbarred on questionable grounds, apparently to prevent them from carrying out their work.

Based on more than 90 in-depth interviews with lawyers, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), journalists, youth group members, political party activists, and relatives of these people, as well as detailed analysis of numerous laws and regulations pertaining to the work of NGOs, this report documents the government’s concerted efforts to paralyze civil society and punish those who criticize or challenge the government through prosecutions and legal and regulatory restrictions.

Abuse and Imprisonment of Government Critics

Following a well-established pattern from 2013 to 2015, in 2016 Azerbaijani authorities used a range of false, politically motivated criminal charges, including drug possession and illegal business activity to arrest at least 20 political and youth activists. Those detained have often been subject to ill-treatment including torture. For example, youth activists Giyas Ibrahimov, 22, and Bayram Mammadov, 21, are currently in detention awaiting trial on charges of drug possession, having signed false confessions under torture. Baku police detained Ibrahimov and Mammadov on May 10, 2016 after identifying them through CCTV footage as having painted graffiti on a statue of former president Heydar Aliyev, father of the current president. Police ordered the men to publicly apologize, on camera, in front of the monument, in exchange for their release. When they refused, police beat them, forced them to take their pants off, and threatened to rape them with truncheons and bottles. They signed the confessions after this.

In another case, in November 2015, security officials detained 68 people in Nardaran, a Baku suburb known for its Shia religious conservatism and vocal criticism against the government. Among them was Taleh Bagirov, a religious scholar, imam, and leader of the “Muslim Unity” public movement. Bagirov and 17 others are on trial, facing charges of terrorism, attempted coup, illegal weapons possession, and homicide. All the men alleged at trials that police repeatedly beat them to compel confessions and testimony. Authorities denied the allegations and did not investigate.

Since August 2016, the authorities have also accused some activists of possessing banned or potentially illegally imported materials related to Fethullah Gülen, the US-based cleric whom Turkey accused of organizing the failed July 2016 coup attempt there.

The authorities also used detention of up to 30 days to harass political and social media activists, on spurious misdemeanor charges of resisting police orders or petty hooliganism. The authorities used such tactics in particular against those involved in organizing, participating in, or vocally showing support for public protests against a controversial September constitutional referendum to expand presidential powers. Officials also targeted several political opposition activists who had criticized the country’s economic deterioration at the time when protests linked to economic concerns were taking place in several different cities from December 2015 to February 2016.

Numerous activists convicted in politically motivated trials from 2013 to 2015 remain unjustly imprisoned, including Ilgar Mammadov, whom the European Court of Human Rights found in 2014 had been imprisoned in retaliation for his criticism of the government, and whose immediate release has been repeatedly called for by the Committee of Ministers.

Decimating Civil Society

For many years Azerbaijan had a large and vibrant community of nongovernmental organizations devoted to such public policy issues as human rights, corruption, democracy promotion, revenue transparency, the rule of law, ethnic minorities, internally displaced persons, religious freedom, and the like. However, prosecutions of NGO leaders and new draconian laws and regulations have decimated civil society by virtually eliminating the space for the work of critical NGOs, particularly for those working on human rights, transparency, and government accountability.

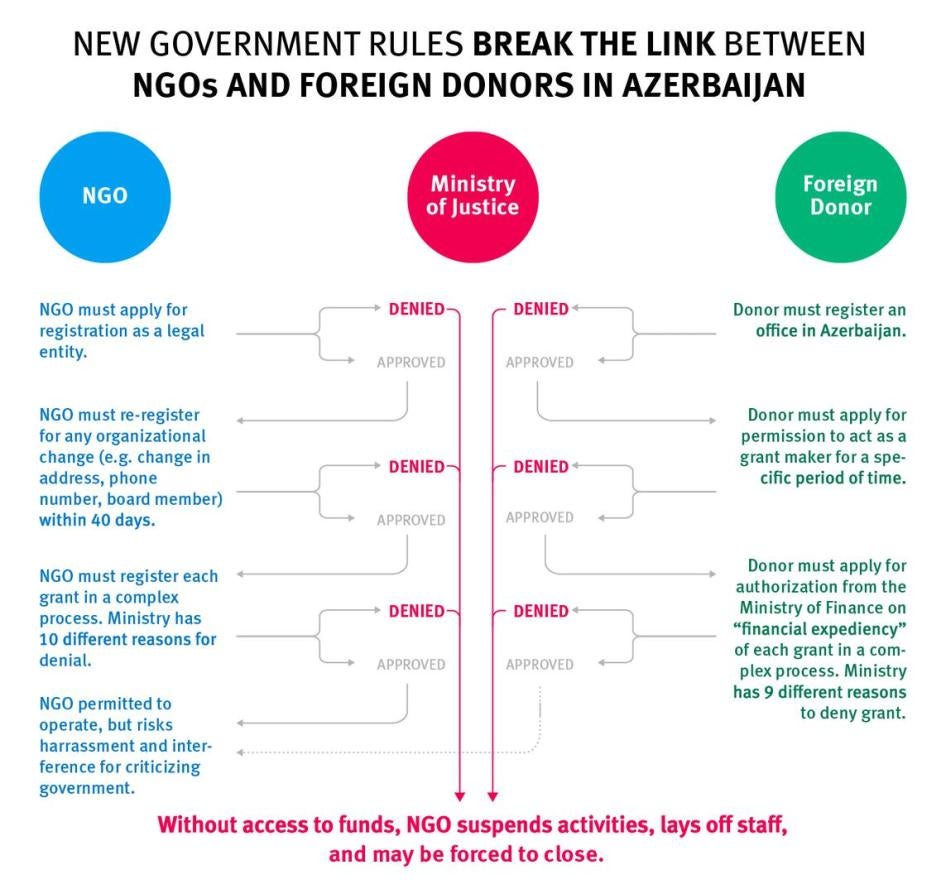

New rules require both the donor and the grantee to separately obtain government approval of each grant under consideration. Whereas previously, registration of grants essentially served a notification purpose, the Ministry of Justice and other agencies now have broad discretion to deny NGOs requests to register grants. NGOs and their staff risk criminal sanctions, including lengthy prison terms, for failure to abide by the grant registration regime. The government frequently denies registration to NGOs working on human rights, accountability, or similar issues on arbitrary grounds.

The laws also require foreign entities to obtain government permission to act as a donor in Azerbaijan, to register a presence in the country, and to obtain approval for each grant. The rules give the Ministry of Finance broad discretion to reject grants on 10 different grounds including on grounds that the ministry does not consider a grant to be financially “expedient” or that there is sufficient state funding in the grant’s proposed area of activities.

Just prior to the passage of the new restrictive laws, the General Prosecutor’s Office initiated a sweeping criminal investigation involving dozens of international donors operating in Azerbaijan and their grantees. The charges related to unregistered grants, although at the time, there was no criminal penalty for issuing or receiving an unregistered grant. As part of this investigation, the government seized bank accounts of domestic NGOs receiving grants from those donors under investigation. The donors were forced to stop their grant-making activities in Azerbaijan, eliminating key sources of funding for many independent civic groups. The majority of international donor agencies and organizations left Azerbaijan in the wake of the investigation and expanded government regulation. In early 2016 the broad criminal investigation was suspended, but not closed.

With the suspension of the investigation, the government unfroze the bank accounts of many groups. However, the act of unfreezing the accounts has not made it easier for the groups to operate, due to the obstacles to securing independent funding, as well as, in many cases, exorbitant tax fines.

Given the extent to which many local groups are dependent on international donor organizations for funding and other support, the cumulative effects of the government policy have been devastating. Anar Mammadli, director of the Election Monitoring and Democracy Studies Center, sentenced in 2015 on spurious charges related to economic crimes and released under a presidential discretion in March 2016, grimly summarized the situation for his work: “So, yes, we are free, but what can we do?! The only space for us now is on social media…or else, leave the country,” he told Human Rights Watch in September 2016.

Harassing Family Members and Targeting Lawyers

The Azerbaijani authorities have also arrested, prosecuted, and harassed activists’ family members with the apparent aim of compelling the activists to stop their work. The authorities have often targeted the relatives of outspoken journalists and activists who have fled abroad out of fear of persecution and continued their vocal activism in exile. In some cases, relatives in Azerbaijan have publicly disowned or renounced their relationships with their close relatives abroad, possibly as a means to avoid retaliation by the authorities for their relatives’ vocal criticism.

Among those facing retaliatory harassment is photo and video journalist Mehman Huseynov. Mehman’s brother Emin Huseynov, director of the media rights group, Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety, sought shelter in the Swiss embassy after his group’s offices were sealed shut by the authorities in August 2014. Later Swiss officials flew him out to Switzerland. Azerbaijani authorities have kept open a spurious criminal investigation against Mehman since 2012, cancelled his identification card and passport, preventing him from travelling abroad, and repeatedly question him about his work and about his brother Emin.

In recent years, the authorities have also targeted the few lawyers prepared to defend government critics in politically motivated trials, through arrests and prosecutions, investigations into lawyers’ organizations, travel bans, and questionable disciplinary proceedings which resulted in disbarments or threats of disbarment. Once disbarred, lawyers cannot represent clients in criminal proceedings. Travel bans prevent lawyers from representing clients at the European Court of Human Rights, receiving further education or training abroad, and participating in international events.

What Should Be Done?

Under international law, and as a state party to both the European Convention on Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the Azerbaijani government has specific legal obligations to protect the rights to freedom of expression, assembly, and association. International human rights law recognizes those freedoms as fundamental human rights, essential for both the effective functioning of a democratic society and the protection of individual dignity. Any limitations to those rights must be narrowly defined to serve a legitimate purpose and must be demonstrably necessary in a democratic society. Furthermore, the European Court of Human Rights has consistently made clear, including through five rulings against the government of Azerbaijan, that the right “to form a legal entity in order to act collectively in a field of mutual interest is one of the most important aspects of the right to freedom of association, without which that right would be deprived of any meaning.”

In line with its international commitments, the government of Azerbaijan should take immediate steps to ensure the unconditional release of political and civic activists, journalists, and human rights defenders held on politically motivated charges and end the use of trumped-up or spurious charges to prosecute government critics. It should also end harassment of activists and their family members.

The authorities should also immediately end the crackdown on civil society, including by ending undue interference with the freedom of the Azerbaijani people to form associations. The authorities should immediately revise the NGO law in line with the recommendations made by the Council of Europe’s Venice Commission, particularly ensuring that overly complicated registration requirements do not create undue obstacles to freedom of association. The government should also repeal regulations that prevent independent nongovernmental organizations from accessing non-state funding and present excessive obstacles to international donor organizations’ grant-making in Azerbaijan.

While many of Azerbaijan’s international partners have been critical of Baku’s serious failures to meet its human rights commitments, the criticism appears to have had little impact on these actors’ relationships with the government. Many actors appear to have prioritized the country’s geostrategic importance and hydrocarbon resources and have sought to deepen relationships and cooperation without insisting on clear human rights improvements. The European Union and the United States should impose visa bans on senior government officials such as ministry of interior officers and prosecutors responsible for the unjustified criminal prosecutions of human rights defenders, journalists and activists in retaliation for their peaceful exercise of their rights.

Azerbaijan’s international partners should also take a comprehensive and coordinated response to the government’s crackdown on independent voices and use their significant leverage, both bilaterally and through multilateral–including financial–institutions, to convince the government to reverse the crackdown. This should include clear benchmarks for human rights improvements and concrete policy consequences should those expectations not be met.

The government of Azerbaijan relies heavily on oil and natural gas export revenues, but the resource price slump in 2015 prompted the government to seek significant support from the Asian Development Bank, the World Bank, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, and the European Investment Bank, creating a key moment at which external influence could help to improve the human rights situation. In continuing to finance development projects that are clearly designed to advance the social and economic needs of the people, these institutions should not provide direct budget support until the government ceases its attack on civil society organizations and activists. Financial institutions should refrain from financing oil and gas projects until the government implements the corrective actions outlined by the board of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI)–a prominent international multi-stakeholder initiative that promotes government openness in natural resource management– particularly ensuring NGOs can receive funding from non-Azerbaijani government sources and an environment that enables public debate on the government’s economic and other policies.

Recommendations

To the Government of Azerbaijan

- Immediately and unconditionally release wrongfully imprisoned human rights defenders, journalists, civil society and political activists, including Ilgar Mammadov.

- Vacate convictions against those released and remove restrictions on freedom of movement.

- End harassment and threats against civil society and media workers.

- End harassment of the family members of activists, journalists, and others whom the authorities have placed under criminal investigation because of the exercise of political rights.

- End the politically motivated prosecutions of lawyers involved in the defense of government critics.

- Ensure that independent civil society groups can operate without undue hindrance or fear of reprisals and persecution.

- Remove undue restrictions to accessing foreign grants and amend legislation on NGOs in accordance with the recommendations of regional and international human rights institutions, particularly regarding the registration, operation, and funding of NGOs.

- Drop all tax-related cases against NGOs and their leaders and drop fines that relate to unregistered grants.

To the European Union and European Member States

- Ensure that public human rights benchmarks are an integral part of the negotiation of a new Partnership Agreement with Azerbaijan, clearly spelling out in any draft agreement the specific steps Azerbaijan should take in order to address concerns in these areas, and consider delaying the start of negotiations until Azerbaijan takes such steps. These should include, but are not limited to:

- Reform of laws and regulations governing nongovernmental organizations and their funding;

- Ensuring that the EU can without undue hindrance fund independent civil society organizations;

- Compliance with the Council of Europe’s Committee of Ministers calling for the release of Ilgar Mammadov.

- Impose visa bans on officials responsible for the ill-treatment of detainees, including unjustly imprisoned human rights defenders, journalists, and activists; also impose visa bans on senior government officials such as ministry of interior officials and prosecutors responsible for the unjustified criminal prosecutions ofhuman rights defenders, journalists and activists in retaliation for their peaceful exercise of their rights.

- Publicly and in all diplomatic engagement raise human rights concerns and call on the Azerbaijani government to take the specific steps listed above and more generally foster an environment in which political and civil society activists can express dissenting opinions freely, including through organizations, without fear of retribution.

To the United States

- Impose visa bans on officials responsible for the ill-treatment of detainees, including unjustly imprisoned human rights defenders, journalists, and activists; also impose visa bans on senior government officials such as ministry of interior officials and prosecutors responsible for the unjustified criminal prosecutions ofhuman rights defenders, journalists and activists in retaliation for their peaceful exercise of their rights.

- Publicly and in all diplomatic engagement raise human rights concerns and call on the Azerbaijani government to take the specific steps listed above and more generally foster an environment in which political and civil society activists can express dissenting opinions freely, including through organizations, without fear of retribution.

To Multilateral Development Banks

- Through diplomatic engagement with the Azerbaijani government and in public statements, raise concerns on the continued crackdown, emphasizing how the crackdown undermines civic participation, social accountability, and public debate, and the importance of an enabling environment for civil society for sustainable development.

- Refrain from providing countercyclical support or policy-based loans to the government until the government has taken the necessary steps to allow independent individuals and groups to participate in the crafting of the country’s development agenda and freely share their views about public affairs.

- Refrain from providing additional financing for extractive industries projects, like the Shah Deniz Gas Field Expansion, until the government is again compliant with the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI). This will help ensure there is a framework within which natural resource revenues can genuinely contribute to inclusive development.

United Nations

- Ensure meaningful follow up to the visits of the United Nations’ Special Rapporteur on human rights defenders and the Working Group on arbitrary detention.

- The UN Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment should request to visit Azerbaijan to examine the situation with torture and ill-treatment in custody and formulate detailed recommendations for steps to address problems identified.

- UN member states should monitor the implementation of the detailed recommendations made by the special rapporteurs on human rights defenders and on arbitrary detentions, as well as the concluding observations and recommendations made by the UN Human Rights Committee review of Azerbaijan in October 2016.

- Members of the Human Rights Council should follow up on their June 2015 joint statement on the situation of human rights defenders in Azerbaijan and call for the release of those still detained on politically motivated grounds and for the revision of legislations affecting NGO activities and access to foreign funding.

Council of Europe

- Secretary General of the Council of Europe Thorbjørn Jagland should continue his inquiry into Azerbaijan’s implementation of the European Convention on Human Rights, and insist on the Azerbaijani government’s full cooperation in the process.

- The Committee of Ministers should continue to closely monitor the implementation of the European Court of Human Rights’ decision on Ilgar Mammadov and ensure its full implementation.

- The Committee of Ministers should urge the Azerbaijani authorities to implement the recommendations made by the Commissioner for Human Rights Nils Muižnieks.

- The Parliamentary Assembly’s monitoring procedure on the honoring of obligations and commitments by Azerbaijan should continue to place strong emphasis on the monitoring and reporting of undue restrictions placed on the work of civil society groups in the country, making detailed recommendations on the steps the Azerbaijani government needs to take to address these concerns.

- Assist the Azerbaijani authorities in bringing its laws and rules regulating the work of civil society groups in line with Azerbaijan’s international obligations and recommendations made by the European Commission for Democracy through Law (Venice Commission).

Methodology

Research for this report was conducted by Human Rights Watch researchers in interviews and document reviews conducted between March and September 2016. Researchers conducted over 90 interviews with lawyers, staff, and leaders of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), journalists, youth group members, and political party members and activists, and their relatives.

Human Rights Watch researchers also reviewed laws, including legislative amendments, adopted since 2014, including to the Law on Grants, the Law on NGOs, and Code of Administrative Offenses, also relevant regulations and rules pertaining to the work of domestic and international nongovernmental groups. Researchers also obtained and analyzed copies of documents relevant to specific cases, including indictments of persons convicted on politically motivated charges and court judgments.

Human Rights Watch also conducted research into the engagement of multilateral development banks and the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) with Azerbaijan. We met with staff and board members of several multilateral development banks. Researchers also reviewed public statements by the European Union, various United Nations agencies, the United States government, and the Council of Europe, in response to Azerbaijan’s crackdown on civil society.

Many interviews were conducted in English and Russian by Human Rights Watch researchers who are fluent in both languages. Numerous interviews were conducted in Azeri by a Human Rights Watch research assistant who is a native speaker of Azeri. In a few instances the names of interviewees have been withheld at their request and out of concern for their security. Researchers explained to each interviewee the purpose of the interview and how the information gathered would be used. No compensation was offered or paid for any interview.

Most interviews were conducted by telephone or via internet communication. Human Rights Watch also interviewed NGO and youth activists, lawyers, political activists, and their relatives residing or traveling outside of Azerbaijan, including in Germany, the Czech Republic, the Netherlands, Poland, and Georgia.

The scope of this research was necessarily limited by constraints imposed by the Azerbaijani government, which is hostile to international scrutiny by human rights organizations. Human Rights Watch does not have direct access to Azerbaijan, after authorities prevented the organization’s researcher for Azerbaijan from travelling to the country in March 2015. Prior to this, Human Rights Watch researchers regularly traveled to Azerbaijan to conduct research and meet with government officials.

Since 2013, Human Rights Watch has closely monitored developments in Azerbaijan and issued numerous news releases, other publications, and videos, urging the authorities to end the crackdown and release human rights defenders, journalists, social media and youth activists imprisoned on politically motivated charges. We have called on the authorities to repeal regressive amendments and allow the unimpeded work of independent nongovernmental groups in accordance to Azerbaijan’s international commitments to uphold freedom of expression and assembly. We have also called on Azerbaijan’s international partners to play a positive role in ensuring the government protects fundamental human rights in Azerbaijan.

Some of the research presented in this report was published in Human Rights Watch news releases and other public documents from 2013 to 2016. The analysis of Azerbaijan’s legal obligations concerning of freedom of expression, assembly, and association has been largely reprinted from Human Rights Watch’s September 2013 report “Tightening the Screws: Azerbaijan’s Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent.”

Human Rights Watch also reviewed media interviews with government officials and official statements related to the findings of this report.

In September 2016, Human Rights Watch sent letters to the Azerbaijani Minister of Justice and General Prosecutor to obtain their response to the findings documented in this report, including their responses to allegations of torture and ill-treatment in custody, politically motivated prosecutions, excessive use of pretrial detention, arbitrary restrictions on freedom of movement, as well as the steps planned to bring legislation and regulations regarding NGOs into line with Azerbaijan’s international commitments, and to implement the Ilgar Mammadov v. Azerbaijan European Court of Human Rights judgment. Human Rights Watch did not receive any response to the letters.

I. Arrests and Convictions of Activists, Journalists, and Others

Throughout 2016, Azerbaijani authorities arrested numerous political and other activists, and bloggers, particularly in August and September, ahead of the September 26 constitutional referendum which expanded presidential powers. The authorities used a range of false, politically motivated criminal charges, including drug possession and illegal business activity. The authorities have also accused some activists of possessing banned or potentially illegally imported materials related to Fethullah Gülen, the US-based cleric whom Turkey accused of organizing the failed July 2016 coup attempt there.

The authorities also harass political activists, including those vocal on social media, through administrative or misdemeanor charges, which carry sentences from 15 to 90 days’ detention. The authorities targeted those involved in criticizing the September 2016 constitutional referendum or organizing or supporting public protests against the referendum, as well as those criticizing the country’s economic deterioration coinciding with protests across the country from December 2015 to February 2016.

The arrests follow a pattern well-established by the government in 2013 to 2015 when authorities arrested or convicted numerous human rights defenders, lawyers, and journalists on politically motivated criminal charges in retaliation for their activism, including at least 40 people in 2014 alone. Many were sentenced to long prison terms in deeply flawed trials. From late 2015 through May 2016 the government released a number of these individuals, including several whose cases had received international attention.

However, many others convicted in 2014 and 2015 in politically motivated trials remain in prison and have exhausted all domestic appeals. Most of the civic activists, journalists, and others released have been forced to stop their work due to restrictive laws and regulations related to nongovernmental organizations (described in more detail in the next chapter). Some activists have left the country altogether and their organizations have ceased to function.

Arrests and Convictions in 2016

Arrests of Individuals with Alleged Links to Fethullah Gülen

Beginning in August, the authorities targeted some outspoken critics claiming that they had ties to Fethullah Gülen, a US-based cleric whom the Turkish government has publicly blamed for the July 2016 attempted coup in Turkey. On August 15, Azerbaijan’s General Prosecutor’s Office announced that a criminal case had been opened to identify and punish the “Gülenists” in Azerbaijan.[1] In an August meeting with his Turkish counterpart, Azerbaijani Interior Minister Ramil Usubov vowed to take all necessary steps against Gülen supporters in Azerbaijan, stating, according to media reports: “We’ll do whatever we can do to eliminate this problem.”[2]

Fuad Ahmadli

State Security Service officials arrested opposition Azerbaijan Popular Front Party (APFP) member and activist on social media, Fuad Ahmadli, on August 18 in downtown Baku. During a search of Ahmadli’s house soon afterwards, police claimed to have found prohibited religious books and compact discs, and leaflets with Gülen’s speeches.[3] Authorities also accused Ahmadli, who is an operator at a local mobile telephone company call center, of illegally obtaining and sharing personal data and other information of mobile phone subscribers. Three other employees of mobile phone operators were arrested on the same charges.[4] Ahmadli is in pretrial detention on charges of abuse of authority and violating the law on operational search activities [surveillance].

A statement by the General Prosecutor’s Office and the Ministry of Interior about the case describes Ahmadli’s opposition political affiliation and cites the “material evidence attesting to [his] illegal activities” as “religious literature prohibited by law and CDs, printed speeches of Fethullah Gülen, and documents on members of the so-called Gülen community.”[5] On August 23, law enforcement authorities reported the merger of Ahmadli’s case with the case of another activist from the Azerbaijan Popular Front Party, Faig Amirov, also suspected of collaboration with the Gülen organization.[6]

Previously, Baku police detained Ahmadli in December 2015 and a court sentenced him to 10 days’ detention for disobeying police orders. Two days prior to his arrest, police officials invited Ahmadli and warned him about his critical Facebook posts.[7] Ignoring the warning, he posted criticism of the government’s currency devaluation and the economic downturn in the country, and asked whether people were desperate enough to protest publicly against the government’s policies.[8]

Faig Amirov

On August 20, two days after arresting Ahmadli, authorities arrested Faig Amirov, an assistant to the APFP chairman and financial director of the leading opposition newspaper Azadlig. During a search of Amirov’s apartment, police took dozens of Azadlig invoices. While searching the apartment and Amirov’s car, police allegedly found books and compact discs about Gülen. According to his lawyer, Amirov denies the books are his and believes police planted them in his car prior to the search. Because the books are imported, Amirov is at risk of charges alleging that the books lacked a special permit required for certain imported goods. The books are not on the list of banned religious literature regulated by the State Committee on Religious Matters.[9]

The statement by the General Prosecutor’s Office claimed that “Amirov, using his position as the financial director of Azadliq newspaper for personal gain, together with like-minded people in the Hizmet [Gülenist] movement is suspected of maintaining connections with people, whose names are on the list of ‘imams of Hizmet.’” The statement also alleges that Amirov distributed Gülenist materials through electronic media.”[10]

Authorities have charged Amirov with “inciting religious hatred” and “infringing the rights of citizens under the pretext of conducting religious rites.” In a public statement, Amirov’s lawyer said the prosecutors allege that Amirov is an imam and delivered sermons that inspired religious animosity.[11] He is in pretrial detention and faces between two and five years in prison if convicted.[12]

Elgiz Gahraman

On August 12, Baku police arrested NIDA youth movement member Elgiz Gahraman on charges of drug possession. NIDA, which is Azeri for exclamation mark, is a youth opposition movement active on social media and highly critical of the government. Police took Gahraman to the Interior Ministry’s Organized Crime Unit. After allegedly discovering 3.315 grams of heroin on him, the authorities charged Gahraman with illegal drug possession in a large quantity with an intention to sell. If convicted, Gahraman faces up to 12 years in prison.[13] On August 13, Baku’s Narimanov District Court authorized Gahraman pretrial detention for four months.

For several days, police did not inform Gahraman’s family of his whereabouts and did not give him access to a lawyer of his choosing; a state-appointed lawyer represented him at the hearing on pretrial measures. Gahraman was only allowed to see his own lawyer on August 19. According to the lawyer, Gahraman said that Organized Crime Unit officers beat him on the head and neck when they first detained him, but later gave him an ointment for his bruises, apparently to fade the marks left by the beating. The lawyer told Human Rights Watch that he saw no visible wounds on Gahraman during the visit.[14]

Gahraman’s lawyer also told Human Rights Watch that Gahraman felt compelled to sign a false statement confessing to drug possession following the beating and after officials also threatened him with sexual humiliation. The officials also made him sign statements about his connection with Fethullah Gülen.[15] Some pro-government media outlets in Azerbaijan had linked Gahraman to Gülen.[16] Gahraman denies any connection to Gülen.[17] On October 7, the Appeals Court dismissed his request to be released to house arrest.[18]

Arrests in Nardaran

Taleh Bagirov

Authorities arrested Taleh Bagirov, a religious scholar, imam, and leader of the “Muslim Unity” public movement, on November 26, 2015 during an operation in Nardaran, a Baku suburb known for its Shia religious conservatism and criticism of government policies.[19] The raid turned violent under unclear and disputed circumstances, with shootings leaving two police and seven civilians dead. Police detained 68 people. Officials have charged Bagirov with a number of grave crimes, including terrorism, attempt to violently seize power, illegal firearms possession, and homicide. In July, Bagirov stated at trial that Ministry of Interior Organized Crime Unit officials beat him repeatedly and injured him, including breaking his nose. The beatings were apparently to compel Bagirov to give testimony against two political opposition leaders as being the masterminds behind the alleged armed uprising.[20] Organized Crime Unit officials kept Bagirov in their custody, rather than transferring him to a pretrial detention facility and did not grant him access to his lawyer until December 29, more than a month after his detention.

Seventeen individuals being tried together with Bagirov also stated that police had beaten them repeatedly to compel confessions and testimony. Authorities denied the allegations but did not thoroughly investigate. Bagirov remains in detention pending trial and faces up to life in prison if convicted.[21]

The authorities had previously targeted Bagirov in politically motivated cases, and he served two years in prison from 2013 to 2015 on spurious drug possession charges. Police had arrested Bagirov in March 2013, one week after he gave a sermon in a mosque sharply criticizing the government.[22]

Fuad Gahramanli

On December 8, 2015, the Azerbaijani authorities detained Deputy APFP Chairman Fuad Gahramanli and charged him with inciting the public to overthrow the government and incitement of national, racial, social or religious hatred.[23] Gahramanli had posted on his Facebook page criticism of the government for the violence during the November 2015 police operation in Nardaran. The prosecutor’s office invited Gahramanli for questioning as a witness in the Nardaran investigation, and when he refused, in the absence of an official warrant, police forcibly took him from his house. The same night, after several hours of interrogation, Baku’s Nasimi District Court ordered him held in pretrial detention. Officials searched Gahramanli’s house and confiscated his computer.[24] The General Prosecutor’s Office accused Gahramanli of “making publications since September 2015 on Facebook, calling citizens to disobey the authorities, [and] carried out activities aimed at inciting religious hatred and animosity between the different currents of Islam.”[25] The trial is ongoing; Gahramanli remains in custody.

Arrests and Convictions of Other Political Activists and Critics

Natig Jafarli

On August 12, authorities arrested Natig Jafarli, a prominent government critic and executive secretary of the opposition Republican Alternative (REAL) movement, interrogated him, and charged him with illegal entrepreneurship and abuse of office. A court sent him to pretrial detention for four months.[26] Officials denied Jafarli access to a lawyer of his choosing during the interrogation and remand hearing. That same night, police searched Jafarli’s house and confiscated two computers and numerous legal documents. On September 9, Baku’s Nasimi District Court released Jafarli on his own recognizance. The criminal investigation against Jafarli is ongoing and he cannot leave Baku. If convicted, Jafarli could face up to eight years’ imprisonment.[27]

The REAL Movement (Republican Alternative), whose leader Ilgar Mammadov is currently in prison on politically motivated charges (see case description below), is a pro-democracy political group seeking the country’s transition from a presidential to a parliamentary republic guaranteeing democratic rights and freedoms.

The charges against Jafarli stem from a criminal case the General Prosecutor’s Office opened against numerous international and domestic nongovernmental groups in 2014 (see below). At the time of his arrest, Jafarli chaired REAL’s Referendum Initiative Group, which campaigned against the September 26 constitutional referendum and the proposed amendments.[28] As a respected economic expert, Jafarli had regularly posted on social media about Azerbaijan’s economic situation and allegations of misappropriation of state funds. Jafarli has come under pressure from the authorities in the past. Officials interrogated him at least 15 times in 2014 and 2015 as part of the General Prosecutor’s large criminal investigation involving dozens of international donors operating in Azerbaijan and their grantees (see below).

Giyas Ibrahimov and Bayram Mammadov

On May 10, 2016, Baku police detained youth activists Giyas Ibrahimov, 22, and Bayram Mammadov, 21, who both face bogus drug possession charges. The two were initially detained because police identified them on CCTV footage as having painted graffiti on a statue of former president Heydar Aliyev, father of the current president.[29] According to the men’s lawyer, Elchin Sadigov, police at Baku’s Narimanov district police station ordered them to publicly apologize, on camera, in front of the monument, in exchange for their release. When Ibrahimov and Mammadov refused, police beat them, forced them to take their pants off, and threatened to rape them with truncheons and bottles. Under duress, the men signed confessions to drug possession. Mammadov is a member of NIDA. Ibrahimov belongs to Solfront, another leftist youth group. Both are students at Baku Slavic University.[30]

Sadigov told Human Rights Watch that he was only able to meet his clients on May 12, after they had signed the forced confessions about drug possession. Sadigov stated that when he was able to meet with his clients, he saw visible bruises on both men, and said they had pain all over their bodies, particularly in their heads and abdomens.[31]

At the May 12 hearing, Ibrahimov and Mammadov retracted their forced confessions and stated that the police had beaten them and threatened them into confessing. They acknowledged to the judge that they had painted the graffiti. The court ordered their pretrial detention for four months. The authorities have failed to conduct an effective investigation into the alleged ill-treatment. The men’s family members allege that the searches of the men’s homes, during which the authorities claim large quantities of narcotics were found, were illegal, and the drugs were planted.[32] In September, Baku’s Khatai District Court extended the pretrial detention of Ibrahimov and Mammadov for another two months. The men remain in pretrial custody at this writing, each facing up to 12 years in prison if convicted.

Tofig Hasanli

On October 12, 2015, authorities arrested Tofig Hasanli, 46, a satirical poet, who often criticized the government in his poems, which he posted online. For five days his family had no knowledge of his whereabouts, and later learned that he was being held in pretrial detention on drug-related charges. Because of financial constraints, his family has not retained a lawyer of their choosing; Hasanli was represented by a state-appointed lawyer at the remand hearing.[33]

Hasanli faces up to 12 years in prison for illegal possession of drugs.[34] Several days prior to his arrest, Hasanli published a poem criticizing senior government officials and members of Azerbaijan’s parliament.[35] In a January 2015 media interview, Hasanli stated that officials in Lenkaran province in southern Azerbaijan had threatend to arrest him if he did not stop writing.[36] He is in detention awaiting trial.

Mammad Ibrahim and Other Activists of the Azerbaijan Popular Front Party

The authorities have also targeted numerous leading and rank-and-file political activists, in particular APFP activists, at least 12 of whom were either on trial or serving prison terms in 2016. For example, in March, a court convicted Mammad Ibrahim, advisor to APFP chairman Ali Kerimli, on spurious hooliganism charges and sentenced him to three years in prison.[37] Other APFP members in prison on politically-motivated charges include Fuad Gahramanli, Seymur Hazi, Faig Amirov, Fuad Ahmadli, Elvin Abdullayev, Jeyhun Isgandarli, Murad Adilov, Zeynalabdin Bagirzade, Mammad Ibrahim, Nazim Mahmudov, and Asif Yusifli.

Use of Administrative Law to Detain Activists

In addition to criminal prosecutions, the authorities have also used the administrative law which covers misdemeanor offenses, such as resisting police or disobeying police orders, to detain activists for up to 90 days. The use of such administrative offences seems to be direct retaliation for their activism, including ahead of the September 26 constitutional referendum and in conjunction with various protests in December 2015 through February 2016 against the country’s economic downturn. Unless otherwise noted, the administrative trials that led to the sentences were perfunctory, rarely lasting longer than 15 minutes, and the judicial decisions on which the detentions are based relied almost exclusively on police testimonies. In all cases documented by Human Rights Watch, the activists could not retain a lawyer of their choosing or mount an effective defense. Human Rights Watch documented 30 cases in which authorities used administrative law offences to jail political and civil activists in 2016.

Detentions in Advance of The September 2016 Constitutional Referendum

September 8-10, 2016

From September 8 to 10, 2016, authorities detained several activists ahead of a September 11 protest in Baku against the constitutional referendum and the economic downturn. The protest had been sanctioned by the city authorities. According to Mehman Huseynov, a 26-year-old well-known blogger, on September 10 plainclothes policemen forced him into a police car and took him to the Baku main police department. He described to Human Rights Watch what happened at the station:

I was taken to the chief, who told me that I should kneel in front of him and that it was the only way for me to talk to him. I said, ‘No.’ Then he tried to kick me and physically force me to kneel. I told him that his actions were illegal and anything he or they would do to harm me, President Aliyev will be held accountable for.

He then retreated and changed his tactics… He was trying to give me “friendly” advice to quit my activism. He said, ‘Aren’t you afraid that someone might kill you? Or throw you out your window?’

Then they changed the tactics again…threatening to rape me, unless I stopped my activism….[38]

After about four or five hours, officials told Huseynov that this was their last warning and that he was free to go home. They encouraged him to write about what happened to him in the police station. “I realized that this was a tactic to intimidate others who were planning to go to the protest [on September 11], so I did not write about what happened, but I told my friends,” he said.[39]

September 16, 2016

In advance of similar protests planned for September 17 and 18, which were officially authorized, police in nine cities detained or issued summons to at least 38 political activists. Most of those detained are from the Popular Front Party of Azerbaijan and the youth opposition group, NIDA. One NIDA activist told Human Rights Watch that he went to Baku’s Narimanov district police department on the morning of September 16 at the request of a neighborhood police officer. Police searched him, confiscated his phone and other belongings, kept him for over 12 hours, and threatened him with criminal drug charges if he continued to participate in opposition protests. He explained:

I was taken to the station chief’s room, who told me that I’ll get 10 days of administrative detention for participation in the demonstration. …Then they took me to another room. There were six or seven police officers there, who started calling me Ali Kerimli’s [opposition leader] agent. Then one officer ordered me to do push-ups. I refused. Then they threw me on the floor, punched me several times and forced me to do push-ups.

Then another officer told me, ‘do you see what I have in my pocket?’ He said it was heroin, which could be “discovered” in my pockets if I continued to participate in opposition protests.[40]

He was released around 9 p.m. after giving a statement that he would not participate in the next day’s protest and would appear in the police precinct next morning.

When the September 17 demonstration in Baku ended, police clashed with protesters and detained dozens.[41] Numerous video clips available online show police rounding up the demonstrators, roughing them up, and taking them away. Protesters in videos reviewed by Human Rights Watch were not seen resisting police or using violence.[42] At least 12 activists, mostly APFP members, were sentenced to eight days’ detention on misdemeanor charges of resisting police orders and at least one person was fined.[43]

Detentions in August 2016

Elshan Gasimov and Togrul Ismayilov

On August 15 in Baku, plainclothes policemen detained two REAL youth activists, Elshan Gasimov and Togrul Ismayilov, as they distributed fliers calling for no votes in the constitutional referendum. At Baku’s Sabayil district police station, officials denied them access to a lawyer or to speak to their families. Police questioned them about REAL finances, including the source of the financing for the fliers, as well as REAL movement’s future plans. The next day a court sentenced them each to seven days’ detention, allegedly for disobeying police orders to stop distributing the leaflets.[44]

Mesud Rzali

On August 12, 2016, police detained Mesud Rzali, 36, a member of the Azerbaijan Popular Front Party (APFP) and a social media activist. Rzali actively discussed political issues, including prosecutions of political activists and government corruption on Facebook. He was sentenced to 30 days’ detention on misdemeanor charges of resisting police. During police questioning, he was asked about his Facebook posts and warned to stop his activism. He was released early on August 29 without explanation.[45]

Detentions Related to Economic Protests

Between December 2015 and February 2016, the authorities sentenced numerous political party members and other political activists to detention on questionable misdemeanor charges. In this period people in cities throughout the country organized public protests against the currency devaluation, increased prices for food and other essential goods, and growing unemployment. Protests usually attracted a few hundred people.[46] Police broke up many demonstrations, and arrested some protesters.[47] Though the gatherings were largely peaceful, in some cases protestors clashed with police. For example, demonstrators in Siyazan, a town 115 kilometers north of Baku, clashed with riot police equipped with tear gas and rubber bullets. Police detained 55 people.[48]

Official statements claimed “religious extremists” and political opposition stirred up popular discontent against the government.[49] Opposition parties rejected the allegations and accused the government of using them as scapegoats in the face of broad public anger over government mismanagement of the economy.[50]

Human Rights Watch documented five arrests of political and social media activists in January 2016 after activists denounced the government’s currency devaluation and price increases. None of these individuals participated in the protests. They were each sentenced to detention ranging from 10 to 30 days.[51] Three of these cases are described below.

Turan Ibrahim

Baku police arrested social media activist and APFP member Turan Ibrahim on January 13, 2016. Ibrahim, who is the son of imprisoned opposition politician Mammad Ibrahim (see above), served one week in detention for allegedly “disobeying police.” According to Ibrahim, seven or eight police officers, who appeared to be waiting for him in front of his house, detained him and took him to a local police station.[52] He told Human Rights Watch that police threatened him with serious criminal drug charges if he did not sign a false statement that he had resisted police.[53]

Rail Rustamov

On February 17, 2016, Baku’s Sabirabad District Court sentenced APFP member and Facebook activist Rail Rustamov to 20 days’ detention for resisting police.[54] According to local police, Rustamov was speeding, was a threat to pedestrians, and disobeyed police.[55]

Rustamov’s father, Sahib Rustamov, is a senior member of the APFP leadership council. He told Human Rights Watch that he believes his son’s detention was in retaliation for his public criticism online; police have threatened and harassed the family in the past for their political activism.[56] Sahib Rustamov said:

The same day my son was detained, I was also brought to the Sabirabad police department. The police chief himself threatened and warned me about my Facebook activism. I was released after three hours. But they kept my son, for nothing else but his Facebook posts. We did not know when and how he was tried. We just heard that he is already in the isolator and sentenced for 20 days.[57]

Khalid Khanlarov

Blogger Khalid Khanlarov, 23, frequently criticized the authorities through a satirical Facebook page called “Ditdili” (Mosquito), and in January 2016 actively commented on the economic situation about public protests related to the economy. On January 23, 2016 a Baku court sentenced him to 25 days’ detention for resisting police. Khanlarov told Human Rights Watch:

I was invited to [Baku’s] Binagadi police station about three days before [my] detention, and warned about my activism on social media. For the next three days, I did not access the internet or share anything on Facebook, but [on January 23] I was invited to the Interior Ministry and from there I was taken to a police station and then to court….and I was sent to administrative detention for 25 days. I got to meet my own lawyer only after I was already in detention.[58]

Other Detentions of Political Activists and Critics

Ruslan Garayev

On June 20, 2016 police detained Ruslan Garayev, the head of the APFP youth committee’s Sumgayit branch, in front of his house. He was sentenced to 20 days’ detention on charges of petty hooliganism and resisting police, based on allegations that he had shouted profanities in the street violating public order and did not obey the police order to stop.[59] Garayev frequently writes blogs and social media posts critical of the government.

For two days following his detention, police did not inform Garayev’s family about his location. His lawyer told Human Rights Watch that he could not access his client for five days and was not allowed to represent Garayev at the administrative hearing.[60] Garayev stated that police questioned him about his political and social media activism, including a satirical photo he took of himself holding an energy drink in front of the statue of the late Azerbaijani President Heydar Aliyev. Garayev was released on August 10.[61]

Relevant Legal Standards

Azerbaijan is a party to both the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), which guarantee fair trial rights and protection against arbitrary detention.[62] For the purposes of international human rights law, the application of standards for rights protection depends not on whether a defendant is facing charges based in the criminal code or in the administrative code, but rather on the substance of the charge against the defendant and the severity of the punishment faced by the defendant. The European Court of Human Rights has in past years ruled that states with a system where individuals can face sanctions such as detention and heavy fines for administrative offences have an obligation to provide adequate due process and fair trial protections in the administrative proceedings in order to comply with the European Convention of Human Rights.

Activists and Journalists Remaining in Prison

Numerous activists convicted in politically motivated trials from 2013 to 2015 remain unjustly imprisoned, including Ilgar Mammadov, whom the European Court of Human Rights found in 2014 had been imprisoned in retaliation for his criticism of the government, and whose immediate release has been repeatedly called for by the Committee of Ministers. Mammadov and others have alleged physical abuse, arbitrary use of solitary confinement, and other abuses by prison staff. This section details Mammadov’s case and several other cases, but is not exhaustive.

Ilgar Mammadov

Ilgar Mammadov, a prominent political analyst and chairman of the opposition group REAL (Republican Alternative), has been in detention since February 4, 2013. The authorities arrested him on charges stemming from anti-government riots in Ismayilli, 200 kilometers from Baku, in January 2013.[63] He was accused of inciting violence and resisting police arrest, and in March 2014, a court sentenced Mammadov to seven years in prison after a politically motivated trial that violated due process and other fair trial protections.[64] Serious procedural violations during the trial included denying the defence the ability to cross examine, including where contradictory testimony was presented, and the exclusion of exculpatory evidence.

In May 2014, the European Court of Human Rights concluded, in a strongly worded judgment, that the actual purpose of Mammadov’s detention “was to silence or punish [him] for criticizing the Government.”[65] Citing that ruling, the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe has called for Mammadov’s immediate release nine times, most recently in September 2016, in order for the government to remedy the violation found by the Court.[66]

However, Mammadov remains imprisoned and has repeatedly come under pressure from the authorities to apologize to and pledge support for President Aliyev in exchange for release.[67] Mammadov twice publicly alleged that he had been attacked in prison for refusing to sign a letter of remorse to President Aliyev—once by a cellmate and once by prison officials. On July 29, 2015 Mammadov’s cellmate attacked him, striking him on the head several times. One of Mammadov’s lawyers, Javad Javadov, said that the attack was meant to pressure Mammadov to write an apology letter. In August, prison officials placed Mammadov in solitary confinement, which his lawyer believes was in retaliation for speaking out about the attack.[68] Council of Europe Secretary General Thorbjørn Jagland sent a letter to Azerbaijan’s Minister of Justice urging a thorough investigation of the attacks and pressure on Mammadov.[69]

A few months later, on October 16, 2015, after a meeting with his lawyer, prison officials took Mammadov to the prison’s administration offices. According to Javadov, two deputy prison directors beat Mammadov on the head and chest and then dragged him to the office of the prison director Eyvaz Asgarov, where they also punched and kicked him. Asgarov threatened Mammadov that he would never be released from prison alive.[70]

Mammadov’s lawyer, who was only allowed to see him on October 19, said that there were visible injuries on Mammadov’s neck and head and that he suffered severe headaches after the beating. After the meeting, his lawyer filed written appeals to the Minister of Justice, the General Prosecutor, and the Ombudsman to investigate the incident and Mammadov’s treatment. Soon thereafter, prison officials, without explanation, refused to allow Mammadov to speak with his family or make telephone calls for one month.[71]

A prison doctor only examined Mammadov five days after the beating and has not made his findings available to his family.[72] A representative of the Ombudsman’s office visited Mammadov ten days after the beating and claimed that since he could not see any visible marks on Mammadov he was not beaten.[73] Mammadov’s wife visited him in late October 2015 and said that one of his teeth was broken and that he continued to have persistent pain in his head.[74] The authorities have failed to effectively investigate the alleged ill-treatment. On April 29, 2016 a court rejected Mammdov’s motion for acquittal.[75] Mammadov appealed the decision and the Supreme Court will hear the case on November 18, 2016.

Ilkin Rustamzade

The authorities arrested blogger and member of NIDA youth group Ilkin Rustamzade in May 2013 on hooliganism charges for alleged involvement in filming a comedy video, but later charged him with inciting violence and organizing mass disorder. In 2014 a court sentenced him to eight years in prison.[76] He is currently being held in prison no. 13. Prior to his arrest, Rustamzade frequently posted criticism about alleged government corruption and human rights abuses on social media, including Facebook and Twitter. He had also created online events in Facebook in 2013 calling attention to the deaths of soldiers in non-combat situations and organizing mass protests in Baku.[77]

The December 2014 Appeal Court and October 2015 Supreme Court decisions left Rustamzade’s sentence unchanged. Prison authorities placed Rustamzade in solitary confinement twice in December 2014 as apparent retribution for his letters from prison critical of the government and his statement at the appeal hearing, in which he reported ill-treatment and abuses against other inmates in prison.[78]

Seymur Hazi

Seymur Hazi, a leading columnist with the opposition paper Azadlig (Liberty) and an anchor for the France-based pro-opposition television channel Azerbaijan Saat (Azerbaijan Hour), has been in detention since August 2014 after an unknown man assaulted him near his home. Hazi defended himself by striking the man with the glass bottle he was holding; the bottle did not break. The police quickly appeared and arrested the journalist. He was charged with “hooliganism committed with a weapon or an object used as a weapon.” On January 29, 2015, a court convicted Hazi to five years in prison.[79] He lost all appeals against his conviction.[80]

Faraj and Siraj Karimov

In July 2014 police arrested Faraj Karimov, 29, a well-known blogger and administrator of the “Basta!” (“Enough!”) and “Istefa” (“Resign”) Facebook pages, which had thousands of followers and served as platforms for criticism about human rights violations, social problems, and corruption in Azerbaijan. Police had detained his brother Siraj Karimov, 30, six days earlier. Both were arrested on dubious drug-related charges. Both Faraj Karimov and his father are the members of the opposition Musavat party and prominent political activists. Faraj Karimov also administered the Musavat Party website.

According to the Karimovs’ lawyer, neither brother had access to a lawyer of their choosing for several days following their respective arrests. Siraj Karimov alleged that Ministry of Interior Organized Crime Unit officials pressured him, under threat of physical harm to his family, to sign a confession to drug-related charges and that police questioned him about Faraj’s activities. A court sentenced Siraj to six years’ imprisonment for drug possession in March 2015. His family and lawyer believe that Siraj was targeted for his brother’s political and social media activism.[81] He was released on March 17, 2016 under a presidential pardon.

Faraj Karimov said the police questioned him exclusively about his Facebook posts.[82] Nevertheless, on May 6, 2015 a court sentenced Faraj Karimov to six-and-a-half-years in prison for drug possession. On May 24, 2016, the Supreme Court reduced his sentence to three years.[83] On October 4 Faraj Karimov was released under an amnesty.[84] Amnesty International had deemed the Karimovs “prisoners of conscience.”[85]

II. Restrictions on Non-Governmental Organizations

Numerous amendments to laws and new regulations put into effect in 2014 and 2015 have severely impacted the ability of NGOs to operate independently in Azerbaijan, further constricting what had already been a difficult operational environment for NGOs.[86] Changes to NGO registration requirements in 2013 and frequent and arbitrary denials of registration to NGOs critical of government policies, meant that many groups operated without registration for many years. The more recent changes curtailed the ability of both unregistered and registered NGOs to seek and receive foreign grants, the primary source of funding for many groups. Only registered NGOs may secure grants through a process in which the Ministry of Justice has wide discretion to deny approval.

Requirements on foreign donors to conduct grant-making activity in Azerbaijan also became more stringent, with donors now required to register a presence in Azerbaijan in a complicated procedure and subject to approval by the Ministry of Justice. To fund local groups, a registered foreign donor must apply to the Ministry of Finance for an opinion confirming that each grant is financially and economically “expedient.”

In 2014, the authorities opened a sweeping criminal investigation into several large donors and their grantees and levied tax penalties on unregistered grants, paralyzing the work of many groups for at least a year. Many groups, including numerous leading human rights groups, have not been able to operate since. Most international donor agencies and organizations left Azerbaijan in the wake of the investigation and expanded government regulation.

In 2014, the authorities also criminally prosecuted and sentenced dozens of NGOs and their leaders, including prominent activists, as well as journalists and others. Although many were released in 2016, as noted above, none have been able to fully resume their work due to the restrictive operational environment for NGOs. Some activists face restrictions, including travel bans, as part of their conditional sentences. Others have felt compelled to leave Azerbaijan out of fears of further persecution.

Cumulatively, these changes have criminalized independent, critical civil society and have made it virtually impossible for independent groups to operate freely. The authorities’ wide discretion to deny or approve registration of domestic and foreign groups and all foreign grants allows them to control which groups and individuals can meaningfully exercise their right to freedom of association, in violation of Azerbaijan’s international legal obligations. The legislative environment and prosecutions of activists and groups have been consistently criticized by authoritative international human rights bodies, yet Azerbaijan has taken no steps to amend laws or revise its punitive practices.

Restrictive Legislation and Regulations to Control NGOs

Arbitrary Denial of Registration and Vulnerability of Unregistered NGOs

NGOs in Azerbaijan are required to register as legal entities with the Ministry of Justice in an excessively bureaucratic process with almost unlimited discretion granted to the authorities to deny registration.[87] In some instances, the authorities have denied NGOs registration multiple times, including for minor errors. For example, the Election Monitoring and Democracy Studies Center (EMDS) has been unsuccessfully trying to register since 2008 after the authorities liquidated its predecessor.[88] In one instance Ministry of Justice officials denied the registration because the organization’s charter contained a one letter error in the spelling of the NGO law. EMDS unsuccessfully appealed the refusal through the courts and have applied to the European Court of Human Rights.[89]

The EMDS worked without registration from 2008 to 2013. Previously individuals affiliated with EMDS could sign grant agreements with donors, register them with the Ministry of Justice, and pay taxes on them; or EMDS conducted joint projects with a registered organization, and relied on this organization for funding. EMDS monitored elections and produced numerous critical reports from 2008 to 2014.

However, the lack of registration made the EMDS vulnerable. In 2014, the prosecutor’s office deemed all of the group’s activities “illegal entrepreneurship” on grounds the group was unregistered. The group’s director, Anar Mammadli, was convicted of illegal entrepreneurship and other charges in May 2014 and spent almost two years in prison before being pardoned in March 2016.[90]

Mammadli described the EMDS’s current situation:

We can’t work. … Since the government refuses to recognize us as a legal entity, we can’t do anything. We also can’t get any grants or implement any projects without registration, as [the authorities would consider it] “illegal entrepreneurship.” I can’t even speak on behalf of the group, use the NGO name, as that would be illegal, since officially there is no such group for the authorities. I can only speak as an individual.[91]

In addition to initial registration, NGOs are required to register with the Ministry of Justice every change to any founding documents or changes in leadership, and obtain a renewed registration certificate in order to continue operation.[92] Registration renewal is required within 40 days for changes of address, number of members, phone numbers, chairperson, and other minor changes. Only after confirmation of the ministry’s registration of changes, can an NGO continue enjoying the benefits of legal entities, like the use of bank accounts or concluding grant agreements. Failure to register such minor organizational changes may result in administrative fines or be the basis for criminal charges of “illegal entrepreneurship.”

In one case the Ministry of Justice refused to register changes to its founding documents requested by the Public Association for Assistance to Free Economy (PAAFE) seven times over eight months in 2014. According to PAAFE’s director, Zohrab Ismayil, the ministry claimed that the request to register the change was erroneously signed by the founder of the organization rather than by the chairperson. The ministry refused to recognize the power of attorney given to the founder. This absence of registration prevents Ismayil from using the group’s bank accounts, forcing PAAFE to stop their work.[93] (See more on PAAFE below).

Intrusive Investigations and Disproportionate Penalties for Registered NGOs

Amendments from 2014 to the Law on Grants, the Law on NGOs, and Code of Administrative Offenses expanded the authorities’ legal grounds to prosecute nongovernmental groups, including registered groups, and provided for higher financial and criminal penalties for minor infractions. The 2014 amendments gave extensive powers to the Ministry of Justice to monitor an NGO’s compliance with the law and impose harsh penalties for any breaches, including a power to petition a court to close down an NGO following two warnings by the ministry within any given year.

In December 2015 the Ministry of Justice adopted new rules on studying the activities of NGOs, which went into force in February 2016.[94] These rules grant the ministry broad powers to conduct intrusive “regular” as well as “extraordinary” inspections on NGOs for up to two months, with very few guarantees for protecting the rights of NGOs.[95] The rules do not set any restrictions on the frequency of inspections or the total number annually.[96] The ministry may conduct inspections to assess the compliance of the NGO’s activities with its own charter and Azerbaijani law. During the inspection it can require the NGO to submit a wide range of documents, including financial documents, budgets, and official correspondence. Failure to cooperate or provision of incorrect information could result in prohibitive fines.[97]

Control Over Resources

The 2014 legislative amendments to the Law on Grants and subsequent government regulations, building on restrictions introduced in 2013 and coupled with strict regulation of foreign donors (described below), have virtually eliminated possibilities for NGOs to receive grants from foreign donors, the only source of funding for most human rights and other NGOs frequently critical of government policies.[98] NGOs and individuals must register all grants with the Ministry of Justice in an onerous process, requiring groups to prepare and submit extensive documentation. The rules on grants provide the authorities 10 different grounds on which they can refuse to register grants.[99] An NGO cannot access funds or implement the grant until it receives notification of grant registration from the ministry.[100] Using funds without the ministry’s approval constitutes illegal entrepreneurship, a criminal offense. Banks cannot release funds to an NGO without a formal letter of registration of the grant funds from the Ministry of Justice. Without access to funds, many NGOs have been forced to suspend activities, dismiss staff, move abroad, or even close.[101]

Legal changes implemented in 2014 also require NGOs to report to the authorities all donations of any amount and the identity of the donor. Cash donations over 200 Azerbaijani manat (US$125) are prohibited and can only be completed by a bank transfer.[102] Failure to report a donation could result in a fine, ranging from 5,000 to 8,000 manat ($3,000 to $5,000).[103] All consultancy or service contracts must also be registered with the Ministry of Justice in onerous process.[104]

These limitations prevent groups like EMDS, which cannot secure foreign funding, from seeking funds from alternative donors. EMDS Director Anar Mammadli told Human Rights Watch that the requirement to notify the authorities of small donors could put those donors in danger, as it could lead to their harassment by the authorities. “For example,” he said, “I could easily crowd source few hundred manat to hold a workshop or roundtable, just by posting a request on social media, but I’ll have to report every small donation and that could put people in harm’s way.”[105]

Mammadli also explained other obstacles the law has brought to EMDS’s work, such as the inability to engage volunteers. “Another impediment to doing any work is that I can’t even have volunteers. As an election monitoring organization, we depended on volunteers. Now, after the changes in the law, [EMDS] needs to sign individual contracts with each volunteer and in order to be able to do that [EMDS] need to be registered.”[106]

Nigar N., whose organization was investigated in 2015 and 2016 (see below), explained that her organization cannot receive or register grants due to the new restrictive registration requirements, forcing the group to severely curtail its work. In a September 2016 interview with Human Rights Watch Nigar N. explained that the organization previously had 10 full-time and over 30 part-time employees. Currently the organization has only four full-time and six part-time staff. Nigar N. said, “Our NGO shrunk more than four times in a bit over a year. Prior to the crackdown our budget was about $300,000 a year. Now, zero. Not $10,000 or 5,000, but zero.”[107]

Nigar N. further described the precariousness of her group’s situation and the vulnerability of NGOs should they not meet all the demanding technical requirements in the reporting. “It’s impossible to plan anything as you never know what will happen tomorrow,” she said. “There’s so much gratuitous paperwork needed for the extensive reporting to the authorities. We are all stressed and afraid of making mistakes [vis-à-vis the authorities].”[108]

Nigar N.’s experience is not unique. About one-third of active civil society organizations in Azerbaijan suspended their activities in 2015, as they were unable to maintain their staff and offices, while another third had to close their offices and work from the homes of their staff. Significant time and resources were spent fulfilling state requirements on registration, operation, and reporting, as well as addressing inspections and inquiries from state agencies.[109]

Restrictions on Foreign Donors

The 2014 laws and subsequent regulations also dramatically increased government control over foreign organizations’ ability to give grants to NGOs in Azerbaijan. All potential foreign donors must register a branch or office in the country and then receive permission from the Ministry of Justice to act as a grant maker for a specific period of time.[110] Even after meeting these requirements, a donor must seek an opinion from the Ministry of Finance on the “financial-economic expediency” of each grant.[111] The rules on foreign donors also give the Ministry of Finance broad discretion, including nine different grounds, to deny grants, including on the grounds that there is “sufficient state funding” for an issue.[112]

The regulations do not provide for an appeals process in the event the ministry denies registration of a donation, grant, or service contract, except in cases of procedural violations, which can be administratively appealed.[113] The Ministry of Justice registered few grants in 2015. The list of approvals is not made public.[114]

Criminal Investigation into Foreign Donors and their Local Partners

In April 2014, the General Prosecutor’s Office initiated criminal investigations against several major international donors, including the National Endowment for Democracy, the Open Society Foundations, Oxfam, the European Endowment for Democracy, and others operating in Azerbaijan on charges of abuse of power and service forgery.[115] In October the investigation expanded into the activities of dozens of individuals and NGOs who had received grants from these donors, leading to repeated interrogation of NGO leaders and staff, prosecutions of some NGO leaders, and seizure of their bank accounts. In the course of 2015 the authorities froze the bank accounts of over 29 NGOs and numerous NGO leaders’ accounts.[116] The authorities also conducted extensive tax inspections into those NGOs, imposed travel bans on some individuals, and subjected some to intrusive physical checks at borders. The authorities suspended but did not close the investigations in early 2016.

Most large international donor organizations and agencies left Azerbaijan following the criminal investigation or because they have been unable to register in the country (see below), further obstructing opportunities for NGOs to engage with potential donors and secure funding. According to Mammadli of the EMDS, “We can’t access donor funds, as all donors working on sensitive issues, like good governance or rule of law, left the country.”[117]

IRFS

One of the organizations that was forced to close in the wake of the investigation was the Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety (IRFS), an NGO registered in 2006 and dedicated to monitoring and promoting media rights and freedom of expression in Azerbaijan. By 2014, IRFS had 35 full-time staff members, five volunteers and two offices in Baku. IRFS documented and exposed violations of freedom of expression and access to information and produced the online TV channel Objective TV dedicated to providing an alternative news source “to counter the increasing government control of traditional news sources.”[118]

According to IRFS Director Emin Huseynov, “Our offices were sealed shut in August 2014, and everything, including our equipment, documents, and all we had, was sealed with it. We had multimedia equipment valued at about $200,000. Our bank accounts were also frozen with about $40,000 in them and they remain frozen until now.”[119] Fearing politically motivated arrest in conjunction with the investigation, Huseynov sought shelter in Baku’s Swiss embassy. He remained at the embassy for 10 months, until the Swiss foreign minister flew him out of the country in June 2015. As described below, Huseynov’s brother remains in Baku and faces harassment and criminal prosecution.[120]

Public Association for Assistance to Free Economy