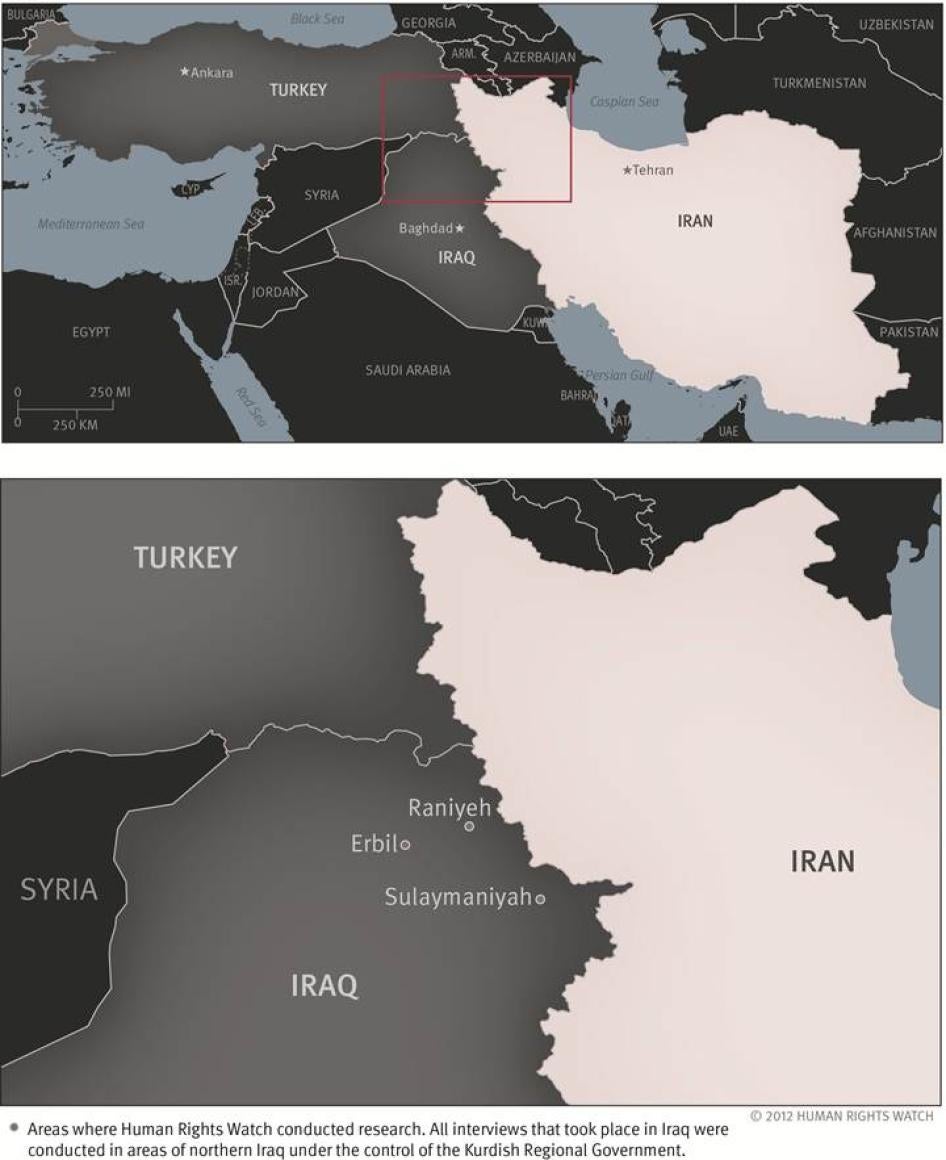

Map of Iran

Summary

Security forces arrested Rebin Rahmani on November 19, 2006, in Kermanshah, the capital of the western Iranian province of the same name. He had been researching the prevalence of drug addiction and HIV infections in Iran’s Kurdish-majority areas. Rahmani spent two months in detention facilities run by the Intelligence Ministry, and was interrogated by intelligence agents in both Kermanshah and Sanandaj, the main city in the adjacent Iranian province of Kurdistan. During his time in detention, he was subjected to several rounds of interrogation accompanied by physical and psychological torture. In January 2007, a revolutionary court sentenced Rahmani to five years in prison on charges of “acting against national security” and “propaganda against the state.” The sentence was handed down after a 15-minute trial during which Rahmani had no access to a lawyer.

Upon his release from prison in the latter part 2008, Rahmani learned that he had been dismissed from university and could no longer continue his education. He became active with a local rights group, but was forced to leave the country in 2011 and apply for refugee status in Iraqi Kurdistan due to mounting pressure against him and his family.

Rahmani is one of scores of journalists, bloggers, human rights activists, and lawyers who have fled Iran since the government embarked on a major campaign of repression following the widespread popular demonstrations against alleged vote-rigging in the June 2009 presidential election, which handed a second term of office to President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. The government’s repression has involved a range of serious and intensifying human rights violations that include extra-judicial killings, torture, arbitrary arrest and detention, and widespread infringements of Iranians’ rights to freedom of assembly and expression.

This report gathers evidence of this campaign of repression from some of its principal victims: Iranian civil society activists. Because Human Rights Watch is unable to work in Iran, most of documentation presented in the report is based on interviews with activists like Rahmani who fled the country to seek refugee status in neighboring Turkey and Iraqi Kurdistan following the 2009 post-election crackdown. The report focuses on four groups: human rights activists, journalists and bloggers, human rights lawyers, and protesters or persons who volunteered for the presidential campaigns of opposition members Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi and were targeted by security and intelligence forces. This report discusses why they left and some of the challenges they face in Turkey and Iraqi Kurdistan as asylum seekers and refugees.

Although most of the hundreds of thousands who took to the streets to protest

the June 2009 presidential election result had not been political or civil

society activists, they nonetheless found themselves targets of security and

intelligence forces. After public protests came to an end, the

authorities continued their relentless assault on all forms of dissent, targeting

civil society groups and activists who had little if any connection to the

protests themselves but whom they deemed to be supporters of a “velvet

revolution” working to undermine the foundations of the Islamic Republic.

Along with members of the political opposition, human rights activists, journalists and bloggers, and rights lawyers bore the brunt of these attacks. Security forces arrested and detained scores of activists, including those advocating on behalf of ethnic minorities, women, and students, and subjected many to trials that did not meet international fair trial standards. Dozens remain in prison on charges of speech crimes such as “acting against the national security,” “propaganda against the state,” or “membership in illegal groups or organizations.”

In addition to the several show trials that authorities convened before television cameras where civil society activists and members of the opposition were indicted for attempting to bring about a “velvet revolution,” one of several landmark events which cast a chilling shadow over Iranian civil society in the months following the June 2009 election was the so called “Iran Proxy” affair. In March 2010, the public prosecutor announced they had arrested 30 or so persons involved in what the authorities said was a plot by the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to destabilize the government. The prosecutor accused those arrested of implementing a plot code-named “Iran Proxy” under the cover of several local non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Revolutionary courts tried, convicted, and sentenced to lengthy prison sentences several of those arrested on national security charged based largely on forced confessions.

The post-2009 crackdown has had a profound impact on civil society in Iran. No truly independent rights organizations can openly operate in the country in the current political climate. Many of the most prominent human rights defenders and journalists are in prison or exile, and other activists are subjected to constant harassment and arbitrary arrest. An indication of the lengths to which the government has gone to stifle civil society and dissent is its targeting of lawyers who have chosen to defend activists and dissidents arrested and charged by the authorities. In recent years, the pressure on rights lawyers defending activists has been unprecedented. Several prominent lawyers, like Nobel Peace Laureate Shirin Ebadi, traveled to European countries and stayed there after it became clear they could not go back without facing harassment, arrest or imprisonment on politically motivated charges.

Others, like Mohammad Mostafaei and Mohammad Olyaeifard, sought refuge abroad. Mostafaei fled Iran after authorities repeatedly summoned him for questioning and detained his wife, father-in-law, and brother-in-law. He is currently residing in Norway. More recently, Olyaeifard, another prominent Iranian lawyer who represented many high profile cases before Iran’s civil and revolutionary courts, was forced to leave the country after serving a one year prison sentence for “propaganda against the state,” imposed by the authorities because he spoke out against the execution of one of his clients during interviews with international media.

The targeting of civil society began well before 2009. The election of Ahmadinejad to his first term as president in 2005 signaled the rise of a populist conservative force, headed by Revolutionary Guards and the associated Basij forces (a paramilitary volunteer militia closely linked with the Revolutionary Guards), with the blessing of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and his allies.

Under Ahmadinejad’s presidency, the attitude of the government shifted from the cautious encouragement of NGOs that had characterized the approach under Ahmadinejad’s predecessor, Mohamed Khatami, to one of suspicion and open hostility. The government increasingly applied a “security framework” in its approach to NGOs, often accusing them of being “tools of foreign agendas.” Authorities also suppressed the work of activists by denying permits to NGOs to operate, often refusing to provide written explanations when rejecting applications, as required by Iranian law.

The increased pressures on civil society activists under Ahmadinejad led some to seek refuge abroad. Since 2009, there has been a noticeable increase in the number of civil society activists who have applied for asylum and resettlement to third countries. According to statistics compiled by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) from 44 industrialized countries that conduct individual asylum procedures, there were 11, 537 new asylum applications from Iranians to these 44 countries in 2009; 15,185 in 2010; and 18,128 in 2011. The largest number of new asylum applications was lodged in neighboring Turkey, which saw a 72 percent increase in the number of Iranian asylum seekers between 2009 and 2011.

The majority of Iranian activists fleeing persecution or the threat of persecution registered refugee claims with the offices of UNHCR in Turkey or Iraqi Kurdistan. The Turkish government has only been willing to provide temporary asylum to Iranian refugees, contingent on UNHCR’s commitment to try to resettle them in third countries. Some activists, especially members of the Kurdish minority, have sought refuge in neighboring Iraqi Kurdistan. Many Iranian refugees there said they did not feel fully secure and were desperate to resettle to a third country as soon as possible.

Human Rights Watch calls on Iran to end its repression of protesters and civil society activists. Iranian activists, government critics, and dissidents should not face the stark choice of risking imprisonment or abandoning their country because they chose to exercise their rights to free speech, peaceful assembly, or association.

Human Rights Watch calls on the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG) to protect the safety and welfare of Iranian refugees and refrain from threats or harassment against those who continue to pursue nonviolent political or rights activities during their time as refugees, and the Turkish government to create conditions that will allow registered refugees and asylum seekers to live and work comfortably while they are waiting for resettlement to a third country. Turkey should also allow Dr. Ahmed Shaheed, the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Iran, access to the country in his official capacity so that he may meet with Iranian refugees and document cases of rights abuses per his mandate.

Finally, Human Rights Watch calls on countries outside the region to speedily process claims of Iranian refugees who urgently need to leave the region and to offer generous numbers of resettlement places for refugees with no other options for durable asylum.

Recommendations

To the Government of Iran

Arbitrary Arrests and Treatment in Detention

- Release all individuals currently deprived of their liberty for peacefully exercising their rights to free expression, association, and assembly;

- Ensure that all persons deprived of their liberty receive family visits, and inform families about the location and status of their family members in detention;

- Abolish the use of prolonged solitary confinement;

- Investigate and respond promptly to all complaints of torture and ill-treatment;

- Discipline or prosecute as appropriate security, intelligence, judiciary and other officials at all levels who are responsible for the mistreatment of detainees in custody;

- Bring Section 209 of Evin Prison and other detention facilities operated by the Ministry of Intelligence or other agencies under the supervision of the State Prisons and Security Corrective Measures Organization or shut it down.

Legal Reform

- Amend or abolish the vague security laws

under the Islamic Penal Code, entitled Offenses against the National and

International Security of the Country (the Security Laws) and other legislation

under the Islamic Penal Code that permits the government to arbitrarily

suppress and punish individuals for peaceful political expression, in breach of

its international legal obligations, on grounds that “national

security” is being endangered, including but not limited to the following

provisions:

- Article 498 of the Security Laws, which criminalizes the establishment of any group that aims to “disrupt national security”;

- Article 500, which sets a sentence of three months to one year of imprisonment for anyone found guilty of “in any way advertising against the order of the Islamic Republic of Iran or advertising for the benefit of groups or institutions against the order”;

- Article 610, which designates “gathering or colluding against the domestic or international security of the nation or commissioning such acts” as a crime punishable from two to five years of imprisonment;

- Article 618, which criminalizes “disrupting the order and comfort and calm of the general public or preventing people from work” and allows for a sentence of 3 months to one year, and up to 74 lashes;

- Article 513 of the Islamic Penal Code, which criminalizes any “insults” to any of the “Islamic sanctities” or holy figures in Islam and carries a punishment of one to five years, and in some instances may carry a death penalty;

- Article 514, which criminalizes any “insults” directed at the first Leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Ayatollah Khomeini, or the current Leader and authorizes punishment ranging from six months to two years in prison.

- Define both “national security” and the breaches against it in narrow terms that do not unduly infringe on internationally guaranteed rights of free expression, association and assembly;

- Excise from the Islamic Penal Code the laws that criminalize “insults” against religious figures and government leaders;

- Change provisions in the Code of Criminal Procedure that allow the right to counsel to be denied in the investigative phase of pre-trial detention. The government should guarantee the right of security detainees to meet in private with legal counsel throughout the period of their detention and trial;

- Take steps to uphold the Citizens Rights Laws, enacted by head of Judiciary Ayatollah Shahroudi on 2004, in Iran’s detention centers. Unlike other laws with a security caveat, the Citizens Rights Laws are intended to be applicable in all circumstances.

To the Government of Turkey

- Allow Dr. Ahmed Shaheed, the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Iran, access to the country in his official capacity so that he may meet with Iranian refugees and document cases of rights abuses per his mandate;

- Ensure law enforcement and other government officials treat Iranian refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants with dignity and respect for their human rights, without exception;

- Allow registered refugees and asylum seekers freedom of movement and choice of residence, with restrictions only to the extent necessary on a case by case basis for reasons such as public health and national security, and which are applied without discrimination on the grounds of national origin;

- Waive residency permit fees to registered refugees and asylum seekers and refrain from preventing them from exiting the country if they have been unable to pay such fees;

- Allow all registered refugees and asylum seekers to secure work permits without additional fees and other requirements;

- Provide all refugees and asylum seekers access to health services, health insurance, and medication on at least the same basis as other non-citizens lawfully present in the country;

To the Kurdish Regional Government

- Refrain from threatening or harassing refugees who continue peaceful political activities against the Iranian government while in areas controlled by the KRG;

- Do not demand that Iranian refugees and asylum seekers secure guarantees or protection from exiled Iranian political parties or Iraqi Kurdish political parties as a condition of residence or renewal of residence permits;

- Unify residence requirements for registered refugees and asylum seekers and allow them freedom of movement and residence in KRG territory subject only to restrictions on a case by case basis to the extent necessary for reasons such as public health and national security ;

To the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees

- Communicate with Iranian refugees and asylum seekers about their prospects for durable solutions;

- Closely monitor and report on alleged attacks, threats, or intimidation by Iranian security and intelligence against Iranian refugees and asylum seekers in northern Iraq;

To Other Concerned Governments, including EU Member States, Canada, Australia, and the United States

- Streamline security background checks and other regulatory checks in order to ensure reasonable timelines for admission of refugees already accepted for resettlement;

- Recognize that some Iranian Kurdish refugees are not able to integrate locally in northern Iraq, and consider them for resettlement;

- Consider admitting more Iranian asylum seekers, especially those who have left Iran because of persecution in response to their civil society or political activities, outside the UNHCR refugee process;

- Provide student visas to Iranian refugees who have been denied entrance to universities in Iran or prohibited from continuing their education because of their political or social activities.

Methodology

The Iranian government does not allow NGOs such as Human Rights Watch to enter the country to conduct independent investigations into human rights abuses. Many individuals inside Iran are not comfortable carrying out extended conversations on human rights issues via telephone or e-mail, fearing they are subject to government surveillance. The government often accuses critics, including human rights activists, of being agents of foreign states or entities, and prosecutes them under the country’s national security laws.

For this report Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 50 Iranian refugees and asylum seekers. The overwhelming majority where interviewed in in Turkey (April 2010) and Iraqi Kurdistan (October and November 2011). Of those interviewed, approximately 35 were election protesters, journalists and bloggers, rights activists, and lawyers who had left Iran since Mahmoud Ahmadinejad took over Iran’s presidency in June 2005, and especially after the disputed 2009 presidential election. In the interest of brevity and efficiency, however, Human Rights Watch selected only a few of the stories it documented for presentation in this report. Some of the individuals interviewed have since been resettled in third countries.

A handful of individuals whose experiences are reflected in this report communicated with Human Rights Watch via e-mail correspondence. Human Rights Watch has confirmed the validity of their stories by conducting additional research, primarily via secondary sources, and identified the information that was acquired via firsthand interviews and those which were gathered via e-mail communications.

Their stories represent a cross-section of the experiences of civil society activists who have been forced to leave Iran in the past few years.

In preparing the report Human Rights Watch also relied on previous information gathered through firsthand interviews conducted by the organization and used in reports, press releases, and other material published since 2005.

All of the interviews were conducted in Persian (Farsi). Most were conducted one-on-one, although a handful of the interviews took place in small group settings. Human Rights Watch informed all of those interviewed that their stories and identities may be used in reports and other material published by the organization. All agreed to the conditions and informed Human Rights Watch that they had no problem with their identities being reviewed. In a few cases, however, Human Rights Watch chose to hide the identities of those interviewed due to the sensitive nature of the issues discussed.

Human Rights Watch also met with and interviewed representatives of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, and received information from UNHCR offices in both Ankara, Turkey and Erbil, Iraq. Human Rights Watch also communicated via e-mail correspondence with UNHCR Ankara and Erbil several times prior to the publication of the report, provided them with an opportunity to review sections relevant to UNHCR’s operations in Turkey and Iraqi Kurdistan, and integrated their feedback and responses where appropriate.

Where noted, the age of interviewees corresponds to their age at the time the interview was conducted.

I. Background

The Rise of Civil Society in the Khatami Era

Iran’s civil society was a direct beneficiary of the policies instituted during the reformist administration of former President Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005). The country witnessed a dramatic rise in the number of independent newspapers and journals, intensified activity by labor groups and professional associations, and an increase in the number of registered (and unregistered) NGOs, including human rights groups. This opening was facilitated by a simultaneous rise in the number of Iranian internet users, particularly bloggers, which allowed NGO activists to reach out to partners across the country and abroad.[1]

Khatami’s government and his reformist allies in the parliament and civil society soon came into conflict with forces associated with the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. These institutions, which include the Guardian Council,the judiciary, and influential elements within Iran’s military, security and intelligence apparatuses, launched a fierce counter-offensive against reformists and prominent civil society actors.[2]

Factions loyal to Supreme Leader Khamenei also introduced greater restrictions on pro-reform newspapers and publications. The attacks on freedom of the press were primarily led by judicial authorities like Saeed Mortazavi, initially a judge in Tehran’s Press Court and later prosecutor general of Tehran, who ordered the closure of dozens of newspapers and dailies.[3] Editors of banned papers frequently applied for permits from the authorities under a new name, continuing the cycle. Mortazavi also prosecuted journalists and bloggers, and was later implicated in the deaths of one journalist and several protesters following the disputed 2009 presidential election.[4]

Despite the counterattack by conservative factions, at the end of Khatami’s presidency in 2005 there were 6,914 registered NGOs, an unprecedented number.[5] Khatami’s government actively promoted the development of civil society and the formation and activities of NGOs. On July 29, 2004, as a step towards institutionalizing NGOs and facilitating their functioning, the Ministry of Intelligence (MOI) submitted to the government draft executive regulations regarding the establishment and activities of NGOs. The government ratified these in July 2005.[6]

Prior to ratification of the executive regulations, NGOs were required to secure permits from either the Ministry of Interior or local government offices.[7]The new regulations created a three-tiered supervisory board made up of government officials and NGO representatives to review applications for permits.[8]

Article 1 of the regulations established councils on the municipal, provincial, and national levels to oversee and facilitate the formation of NGOs.[9]Members of the municipal-level councils include the mayor, a representative from the city council, and a representative from the NGO community.[10]Members on the provincial level include the governor, a representative from the provincial council, and an NGO representative.[11] On the national level, the council is made up of a deputy from the Ministry of Interior, a representative from the High Council of Provincial Representatives, and a representative of NGOs selected by the organizations themselves.[12] The regulations also established a process for appealing decisions by the supervisory board when NGO applications were rejected.[13]

Among NGOs established during the reform period were organizations dedicated to promoting civil and human rights inside the country. The most well-known was the Center for Human Rights Defenders, founded by Nobel peace laureate Shirin Ebadi and several other prominent lawyers in 2002.[14] That same year Dr. Sohrab Razzaghi, a law and political science professor at Allameh Tabataba’i University in Tehran, founded the Iranian Civil Society Organizations Training and Research Center (ICTRC) to provide capacity-building support for civil society organizations, promote greater access to information, and raise public awareness regarding the situation of human rights in Iran.[15] A year later, in 2003, journalist and rights activist Emad Baghi, a prominent writer and rights activist, launched the Association to Defend Prisoners’ Rights.[16]

During the first year or so of Ahmadinejad’s presidency, several additional prominent civil society and rights groups came into existence. The One Million Signatures Campaign launched a grassroots effort to promote broad awareness on women’s rights issues and collect signatures on petitions to reform gender-biased laws. The Committee of Human Rights Reporters and Human Rights Activists in Iran began their activities a year earlier in 2005.[17]

However, conservative factions were relentless in their efforts to undermine such reforms. Forces loyal to Supreme Leader Khamenei increased the pressure against President Khatami’s reform movement on multiple fronts. They attempted to impeach several of his cabinet ministers. Security forces arrested, and the judiciary tried and convicted, several prominent reformist allies of Khatami such as former Interior Minister Abdollah Nouri, former Tehran mayor Gholamhossein Karbaschi, and reformist cleric Mohsen Kadivar. When those attempts failed to intimidate the reformists, Khamanei loyalists intervened to block the passage of pro-reform policies and legislations.[18]

During Khatami’s second term in office, and the conservatives gradually began to gain the ascendancy in their political struggle with the reformists. Ahead of the 2004 parliamentary elections, the Guardian Council disqualified an unprecedented 3,600 candidates, many of them reformists. Approximately 87 sitting parliament members were among those disqualified.[19]More than 100 members resigned in protest.[20] It was now clear that the reform movement had been checked.

Targeting of Civil Society Activists During Ahmadinejad’s First Term

The election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad as president signaled the entry of the new populist conservative force, voted in with the support of Revolutionary Guards and the Basijand with the blessing of Khamenei and his allies.[21] Ahmadinejad’s cabinet members included individuals who were believed to be responsible for serious rights abuses, including the serial murders of dissidents in 1998, the closure of newspapers, and attacks against NGOs.[22]

Under Ahmadinejad’s first term as president, the attitude of the government shifted from tolerance and cautious encouragement of NGOs and grassroots movements to suspicion and hostility. The government increasingly applied a “security framework” to its approach to NGOs, often accusing them of being “tools of foreign agendas.” The councils established to approve and regulate NGOs now suppressed the work of activists by denying permits to NGOs to operate, often refusing to provide written explanations for rejecting applications as required by law.[23]

An example of the government’s increasingly hostile attitude toward civil society was its crackdown against the One Million Signatures Campaign. In 2006, after security forces attacked men and women gathered in Tehran to protest discriminatory gender-biased laws, women’s rights activists launched a campaign to oppose discriminatory laws that govern marriage and inheritance, compensation for bodily injury or death, and a woman's right to pass on her nationality to her children. Campaign members initiated a website and held regular workshops in Tehran and other cities in order to educate the public about legal challenges facing women and girls in the country.

Within months of the campaign’s launch, security forces began arresting volunteers who were out in the streets collecting signatures.[24]

Under Iranian law, the courts have the authority to decide whether a registered organization should be closed down.[25] In 2006, Ahmadinejad’s government introduced a draft NGO law intended to further restrict the activities of NGOs. Although this draft has been shelved by the parliament and not yet become law, it demonstrated the hostility of Ahmadinejad’s government to civil society, and there is concern that the new (and more conservative) parliament elected in February 2012 will take it up again. Organizations affected would range from human rights, environmental, and women’s organizations, through charities and organizations for the disabled, to employers’ and professional associations.[26] The bill would establish a Supreme Committee Supervising NGO Activities, chaired by the Ministry of Interior and including representatives from the Ministry of Intelligence, the police, the Basij, the Revolutionary Guards Corps, and the Foreign Ministry, and only a single person representing NGO interests. The committee would be able to issue and revoke all NGO registration permits and have ultimate authority over the composition of their boards of directors.[27]

On March 15, 2007, officers from the Ministry of Intelligence and Iran’s revolutionary courts, operating with a court order, closed down three NGOs: the ICTRC, the Rahi Legal Center (run by rights lawyer Shadi Sadr), and the Non-Governmental Organizations Training Center (managed by civil society and women’s rights activist Mahboubeh Abbasgholizadeh). Revolutionary courts later convicted all three on charges related to national security.[28]

In December 2008 security and intelligence officials shut down Shirin Ebadi’s Center for the Defense of Human Rights without producing a court order. They alleged the center was carrying out illegal activities that endangered national security. Since the closure, the center’s members have been harassed and some convicted and imprisoned.[29]

Crackdown on Protest and Civil Society after the June 2009 Election

During the lead-up to the June 12, 2009 election large demonstrations and rallies for reformist candidates Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi led many to believe that Ahmadinejad might be defeated. However on June 13, 2009, Iran’s Ministry of Interior announced that President Ahmadinejad had won the election with 62.6 percent of the popular vote. In response hundreds of thousands of Iranians filled the streets of Tehran and other major cities to protest peacefully against what they believed to be fraudulent election results.

Iranian authorities, initially taken by surprise, quickly declared the protests illegal. When hundreds of thousands of Iranians continued to take to the streets security forces responded with brute force. Anti-riot police, aided by intelligence agents as well as plainclothes and uniformed Basij paramilitary forces beat, arrested, and detained thousands. Excessive force, including the use of live ammunition against unarmed and for the most part non-violent protesters, led to the deaths of several dozen protesters between June and December 2009.[30]

Some protesters lost their lives not in street clashes but in detention facilities, where security forces subjected them to torture and ill-treatment, in some cases including rape and sexual assault. At least five detainees died due to abuses sustained at Kahrizak detention center outside of Tehran.[31] Five students were killed when plainclothes and uniformed security forces carried out a nighttime raid on dorms at Tehran University on June 14, 2009.[32]

Despite widespread repression in the weeks following the election, peaceful protest demonstrations continued. During the fall and winter of 2009, government forces attacked peaceful protestors in response to major demonstrations such as those held on November 4 (the anniversary of the 1979 takeover of the US embassy), December 7 (National Student Day), and in conjunction with the Shia religious holiday of Ashura on December 27. These attacks by security forces and Basij killed at least eight and injured many more.[33]

The government also continued to harass and intimidate activists, including individuals who worked for Mousavi or Karroubi’s campaigns, journalists, and human rights defenders, subjecting more than 100 to trials that were in part televised and did not meet international fair trial standards, and convicting others solely for exercising their right to peaceful dissent.[34]

The nature and size of the crackdown dramatically reduced the space for civil society and independent or critical voices in Iran. Activists, dissidents, and critics of the government faced a stark choice: risk arrest, detention, and conviction, or leave. Many chose the latter option. According the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the number of new Iranian asylum seekers in Turkey and several other countries has steadily increased since the government’s ferocious response to the post-election protest led to a new wave of emigration.[35]

II. Attacks on Civil Society

The “Iran Proxy” Affair and Local Rights Groups

In December 2010, the Iranian authorities started arresting members of a Tehran-based NGO which had been monitoring human rights violations in Iran for nearly five years. These were among the first steps in a government operation which was to culminate in the trial of 30 or more activists for alleged involvement in a foreign plot against Iran under the cover of human rights activism: the so called “Iran Proxy” affair. Along with other trials of opposition figures and alleged plotters such, the “Iran Proxy” trial cast a chilling shadow over Iranian civil society—which the Ahmadinejad government was already subjecting to severe repression.

The NGO in question was the Committee of Human Rights Reporters (CHRR). The security forces arrested two CHRR members, Saeed Kalanaki and Saeed Jalalifar, on December 1, 2009 and detained them in Evin prison. On the evening of December 20, 2009, security forces arrested three more CHRR members, Shiva Nazar Ahari, Koohyar Goudarzi, and Saeed Haeri when they were on a bus about to leave Enqelab Square in Tehran for the city Qom, where they had planned to attend the funeral of Grand Ayatollah Montazeri a prominent opponent of the government.[36]

On January 1, 2010, the Ministry of Intelligence (MOI) contacted Hesam Misaghi, who worked with CHRR, and several of his colleagues by phone and summoned them for interrogation. The MOI agent informed Misaghi that a warrant for his arrest had been issued, and threatened to raid his home if he did not voluntarily report to the MOI office. Later that day, two other CHRR members who had been similarly summoned to the MOI office presented themselves and were promptly arrested.[37]

Misaghi ignored the MOI summons and went into hiding Because of the increasingly tense security situation inside Iran (including at least one threatening phone call from the MOI to Misaghi’s family demanding that he turn himself in), his membership with the CHRR, his Baha’i background, and his work on protection of Iran’s lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community, Misaghi decided to leave the country and entered Turkey with his colleague Sepehr Atefi in January 2010.[38]

On January 2, 2010, the security forces detained two more members of CHRR, Parisa Kakaei and Mehrdad Rahimi, when they responded to a summons to report to the Ministry of Intelligence (MOI) in Tehran. During their detention the seven CHRR detainees faced severe pressure to confess falsely to having links with the banned Mojahedin-e Khalq organization.[39] None of the detainees were initially allowed access to lawyers or were formally charged.

On March 2, 2010, another one of Misaghi’s colleagues, Navid Khanjani, was arrested in Esfahan. The next day, March 3, security agents raided the homes of Misaghi and Atefi and presented their family members with arrest warrants indicating that the two were wanted for the crime of moharebeh, or “enmity against God.” The punishment for this crime is death. The individuals who arrested Khanjani informed him that they knew Misaghi and Atefi had escaped to Turkey, and that they would do everything in their power to bring them back to Iran.[40]

The extent of the government’s operation against NGOs heralded by these arrests became clear on March 13, 2010, a week before the Iranian New Year, when Tehran's Public and Revolutionary Prosecutor’s Office announced that security forces had arrested 30 people they said were involved in a CIA-funded project to destabilize the government with “cyber warfare.” The prosecutor's office maintained that a network of opposition groups implemented a project code-named “Iran Proxy” under the cover of local human rights organizations, including CHRR and two other groups:, the Center for Defense of Human Rights (CDHR), and Human Rights Activists in Iran (HRA).[41]

Less than two weeks after the announcement by the Tehran prosecutor’s office a member of HRA told Human Rights Watch that security forces arrested 15 of its members and attempted to arrest 29 others. Among those arrested was Farideh Rafiee, the sister of the group's former executive director, Keyvan Rafiee, who currently lives outside Iran. HRA maintained that Farideh Rafiee herself was not an HRA member.[42]

The government denounced all three groups publicly and accused the “network” of hacking into state-owned websites; organizing and supporting foreign opposition and terrorist groups, including the banned Mojahedin-e Khalq (MEK); conducting illegal protests; publishing false information; and engaging in “psychological warfare” and espionage. All three groups issued statements denying any involvement with the alleged "Iran Proxy" project and confirmed their financial independence from foreign governments. The Center for Defense of Human Rights, which had been forced to close in December 2008 but maintained its website, called the attacks a "frame job against human rights activists and civil society."[43]

The authorities provided no evidence to support their allegations.[44] Revolutionary courts have nonetheless tried, convicted and sentenced some of those arrested on politically motivated national security charges in separate trials based largely on forced confessions. Others remain out of prison on bail or are awaiting summonses to serve their prison terms. Of the eighteen members of CHRR, three including Shiva Nazar Ahari, Koohyar Goudarzi, and Saeed Jalalifar, recieved lengthy prison terms and are either behind bars, or can be summoned to prison at any time.[45] Five others in the group left Iran for Turkey and have since been resettled in Europe (see below for the story of Hesam Misaghi a CHRR member who fled to Turkey). A few members of the HRA are also serving prison sentences, and at least five CDHR members, including some of the most prominent rights lawyers in the country, have also been arrested in recent years and are currently in prison.[46]

Minority Rights Activists

As well as clamping down on Tehran-based rights groups like CHRR HRA, and CHRD, Ahmedinejad’s government increasingly applied a “security framework” in its approach to NGOs working on minority rights, accusing them, too, of being “tools of foreign agendas.”[47] The NGO councils that had been established under the Khatami government to promote and regulate NGOs were now tasked with suppressing the work of minority rights activists, especially those working on Kurdish, Azeri, and Ahwazi Arab issues, by denying permits to NGOs to operate and often refusing to provide written explanations for rejecting applications as required by law. [48] But even those minority rights organizations that were able to register and obtain permits still faced harassment and worse.

The Human Rights Organization of Kurdistan (HROK) is an example. Founded in 2005 by journalist Sadigh Kaboudvand, the group grew to include 200 local reporters throughout the Kurdish regions of Iran and provided timely reports in the now banned newspaper Payam-e Mardom (Message of the People), of which Kaboudvand was the managing director and editor. Intelligence agents arrested Kaboudvand on July 1, 2007, and took him to Ward 209 of Evin Prison, which is under Ministry of Intelligence control and is used to detain political prisoners. They held him without charge in solitary confinement for nearly six months.[49]

In May 2008, Branch 15 of the Revolutionary Court sentenced Kaboudvand to 10 years in prison for “acting against national security” by establishing the HROK, and another year for "widespread propaganda against the system by disseminating news, opposing Islamic penal laws by publicizing punishments such as stoning and executions, and advocating on behalf of political prisoners.” In October 2008, Branch 54 of the Tehran Appeals Court upheld his sentence.[50] Human Rights Watch has repeatedly called on the Iranian authorities to unconditionally free Kaboudvand and provide him with access to urgent medical care.[51]

Due to geographic proximity, the Iranian authorities’ sensitivity to ethnic rights issues, and cross-border cultural kinship, the majority of the ethnic minority rights activists who fled to Turkey and Iraqi Kurdistan[52] since 2005 are Iranian Kurds.

Women’s Rights Activists

Since Ahmadinejad became president in 2005, the government has also stepped up repressive measures against women’s rights organizations and activists. Security forces and judiciary officials have routinely subjected women’s rights activists to threats, harassment, interrogations, and imprisonment.

In June 2006, after security forces attacked men and women gathered in Tehran to protest discriminatory gender-based laws, women’s rights activists launched the One Million Signatures Campaign, a grassroots effort aimed at collecting signatures in support of a petition opposing Iran’s gender-biased laws, including those that govern marriage and inheritance, compensation for bodily injury or death, and a woman's right to pass on her nationality to her children. Campaign members initiated a website and held regular workshops in Tehran and other cities in order to educate the public about legal challenges facing women and girls in the country.[53]

The campaign both inspired and supported women’s rights activists working outside of Tehran. Many began working with the campaign or adopted its model of grassroots activism to educate the public and promote women’s issues in their hometowns. Local Kurdish women’s rights activists were among those who embraced the campaign’s model.

Within months of the campaign’s launch, security forces began arresting volunteers who were out in the streets collecting signatures. Sussan Tahmasebi, one of the campaign’s cofounders, was charged with spreading propaganda against the state and threatening national security after she organized a protest in support of women’s rights in June 2006. She was tried on March 4, 2007, and sentenced to 2 years in prison, 18 months of which was suspended. Tahmasebi appealed the ruling and was freed on bail pending the appeal, which is ongoing.[54]

On the day of her trial, women’s rights activists held a demonstration outside of the Tehran Revolutionary Court to protest increasing pressure on women activists. Tahmasebi left the court as security forces began to arrest the protesters and was arrested a second time, along with 32 others, and charged with threatening national security, assembly and collusion against national security, and disobeying the orders of police. She was later acquitted of these charges but continued to endure harassment by security forces, who searched her home and subjected her to numerous interrogations. She was banned from traveling on several occasions between December 2006 and January 2009.[55] Tahmasebi left Iran in 2010 and is currently in the United States.

Student Activists

Iran’s universities have increasingly become targets of government efforts to consolidate power and stifle dissent. Since 2005, President Ahmadinejad’s administration has pursued a multi-phased campaign to neutralize dissent at universities and “Islamicize” higher education. This campaign, spearheaded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, and the Ministry of Intelligence, includes imprisoning student activists; barring politically active students and members of Iran’s Baha’i community from higher education; using university disciplinary committees to monitor, suspend, or expel students; increasing the presence on campuses of pro-government student groups affiliated with the Basij; and restricting the activities of student groups.[56]

In 2009, the Ministry of Science, Technology, and Research declared illegal one of Iran’s largest and most important student groups, Tahkim-e Vahdat(the Office for Consolidating Unity).[57] During the crackdown that followed the disputed June 2009 presidential election, security forces attacked Tehran University and killed several students on June 14. In the months that followed authorities arrested more than 200 students, including several high-ranking members of Tahkim. Many of these arrests took place in November and early December 2009.[58]

As of May 2012 there were at least 32 students in prison throughout the country as a result of their political activities or affiliation with banned student groups, according to sources close to Tahkim.[59] Authorities held scores of students incommunicado for weeks before prosecutors filed charges against them and lawyers gained access to them. Many told human rights groups that security and intelligence agents had tortured and forced them to confess to crimes they had not committed. The Judiciary prosecuted the students in closed trials in Iran's revolutionary courts.[60]

Many of the students in prison held leadership positions in well-known student organizations critical of the government, including Tahkim. Majid Tavakoli, an Amir Kabir University student, belonged to the school’s Islamic Student Association and publicly criticized the government. In 2010 a revolutionary court sentenced Tavakoli to eight-and-a-half years in prison on various national security charges including “conspiring against national security,” “propaganda against the state,” and “insulting the Supreme Leader” and president. He is in Tehran’s Evin prison.[61]

On December 30, 2009, authorities arrested Bahareh Hedayat, the first secretary of the Women’s Commission of Tahkim and the first, and so far the only, woman elected to Tahkim’s central committee. They charged her with various national security crimes, including “propaganda against the system,” “participating in illegal gatherings,” and “insulting the president.” In May 2010, a revolutionary court sentenced her to nine-and-a-half years in prison.[62] Security forces arrested Milad Asadi, also a Tahkim central committee member, on November 30, 2009. A judge known as Judge Moghiseh from Branch 28 of the Tehran Revolutionary Court sentenced him to seven years in prison for similar national security-related “crimes.”[63]

Hedayat is serving her sentences in Tehran’s Evin prison, but authorities released Asadi after he and several other political prisoners were granted a pardon by Ayatollah Ali Khamenei in September 2011.

The Ahmadinejad administration also targeted other student organizations and their members, including Advar-e Tahkim-e Vahdat (Tahkim’s alumni group) and the Committee to Defend the Right to Education (CDRE). Several leaders of Advar are in Evin prison, including Ahmad Zeidabadi,Abdollah Momeni, Ali Malihi, Ali Jamali, and Hasan Asadi Zeidabadi. Security forces arrested Zeidabadi and Momeni, the group’s secretary-general and spokesperson respectively, in the aftermath of the election protests in 2009. Zeidabadi, Momeni, and Malihi are each currently serving sentences of 14 years and 11 months on various national security charges such as “participation in illegal gatherings,” “propaganda against the state,” and “insulting the president.”[64]

Zia Nabavi, a co-founder of CDRE, is serving a 10-year sentence in Ahvaz’s Karun prison. Ministry of Intelligence agents arrested Nabavi on June 15, 2009, and prosecutors charged him with various national security related crimes, including links to and cooperation with the banned Mojahedin-e Khalq organization (MEK).[65]Mahdieh Golroo, a student activist and another member of CDRE, was in prison since November 3, 2009, but has since been released. In April 2010, a revolutionary court convicted her of national security crimes and sentenced her to 28 months in prison.[66] Another cofounder of CDRE, Majid Dorri, is serving a six-year prison sentence for his student activities.[67]

Several hundred others have been expelled from campus because of their political activism or religious affiliation. Since 2005, authorities have barred more than 350 students from university education on political and religious grounds, according to a recent report by the UN special rapporteur on the human rights situation in Iran.[68]

Nabavi, Golroo, and Dorri formed CDRE in 2008 after authorities barred them from continuing their university studies. It is one of several student groups that publicized and resisted the government's policy of preventing students from continuing their higher education on political or religious grounds. Another similar group is the Population to Combat Educational Discrimination, which largely addressed the government's official policy of preventing Baha’is admission to or expelling them from universities once it becomes known that they are Baha’is. In 2009, authorities also prevented Ali Qolizadeh and Mohsen Barzegar, two recently arrested members of Tahkim-e Vahdat, from continuing their studies.[69]

According to a recent Tahkim report, since March 2009 there have been 436 arrests, 254 convictions, and 364 cases of deprivation of education against students. Tahkim also alleges that the judiciary summoned at least 144 students for investigations, and that officials have closed down 13 student publications.[70] As a result of these pressures, dozens of student and student activists, many of whom were deprived of continuing their education, left Iran to pursue their education elsewhere.

Journalists and Bloggers

Since President Ahmadinejad took power in 2005, dozens of journalists and bloggers have left the country because of increasing limitations on the press and threats against them. According to Reporters Without Borders, more than 76 journalists were forced into exile in and authorities have shut down at least 55 publications since 2009.[71]According to Reporters Without Borders as of August 2012 there were at least 44 journalists and bloggers in prison, making Iran one of the largest jailer of journalists in the world.[72] The Judiciary imposed harsh sentences on journalists and bloggers based on vague and ill-defined press and security laws such as “acting against the national security,” “propaganda against the state,” “publishing lies,” and insulting the prophets or government officials such as Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei or President Ahmadinejad.[73]

In September 2010, a revolutionary court sentenced Hossein Derakhshan, a prominent Iranian blogger, to 19-and-a-half years in prison for espionage, “propaganda against the state,” and “insulting sanctities.”[74] On January 17, 2012, Iran’s Supreme Court confirmed the death sentence for Saeed Malekpour, a blogger holding Canadian permanent resident status, convicted of “insulting and desecrating Islam” in October 2011. In December 2012 Malekpour’s lawyer announced that his client had repented and the Judiciary had therefore suspended his death sentence.[75] The judiciary has sentenced at least three other individuals, Mehdi Hashempour, Vahid Asghari, and Mehdi Alizadeh, to death on internet-related charges including “running obscene websites.”[76]

The government blocks many websites that carry political news and analysis, slows down internet speeds to hinder web access, and jams foreign satellite broadcasts. In March 2011, authorities announced that they were funding a multi-million-dollar project to build what they called a halal(i.e. permissible according to Islamic law) national internet in Iran to protect the country from socially and morally corrupt content. On January 4, 2012, local newspapers printed new regulations issued by Iran’s new cyber police unit that gave internet cafes 15 days to install security cameras and begin collecting personal information from customers for tracking purposes. Internet users and rights groups are concerned that an increase in recent interruptions to internet connectivity and blocked sites may be evidence that Iran is testing their new national intranet.[77]

On September 21, 2010, a revolutionary court sentenced Emad Baghi, the prominent writer and rights activist who founded the Association to Defend Prisoners’ Rights, to six years in prison for an interview he had conducted in 2007 with dissident cleric Grand Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri, which the BBC had rebroadcast in 2009.[78] An appeals court later overturned five years of Baghi’s sentence and prison officials released him on June 20, 2011.

Human Rights Lawyers

Since 2005, and especially since June 2009, authorities have imprisoned, prosecuted, or harassed dozens of defense lawyers. In August 2011, Nobel Peace Laureate Shirin Ebadi said at least 42 lawyers had faced government persecution since 2009. Several lawyers are currently serving prison sentences on politically motivated charges, while others like Ebadi have effectively been forced into exile, in Ebadi’s case after authorities shut down her Center for Defenders of Human Rights (CDHR) and declared it illegal.[79]

They have also resorted to other methods to prevent lawyers from practicing their profession freely. Such measures include unwarranted tax investigations under which the authorities freeze the lawyers’ bank accounts and other financial assets and which could lead to the disbarring of a lawyer.[80] Authorities have also limited the independence of the Iranian Bar Association by barring lawyers from running for high-level office in the association on discriminatory grounds, including their imputed political opinions and their human rights activities. For example, in 2008, Mohammad Ali Dadkhah, Hadi Esmailzadeh, Farideh Gheyrat, and Abdolfattah Soltani, all members of the Center for Human Rights Defenders, were disqualified by the judiciary from running in the election for the association’s Central Board because of their activities as human rights defenders.[81]

In September 2010, authorities arrested Nasrin Sotoudeh, who represented numerous political prisoners. On, January 9, 2011, Iranian authorities sentenced Sotoudeh to 11 years in jail for charges that included “acting against the national security” and “propaganda against the state.” She was also barred from practicing law and from leaving the country for 20 years. In September 2011, the Judiciary reduced her sentence to six years imprisonment.[82]

High-level Iranian officials denied accusations that Sotoudeh was arrested for her activities as a lawyer. In 2010 Mohammad Javad Larijani, the head of the Human Rights Council of the Judiciary, said that Sotoudeh had engaged “in a very nasty campaign” against the government, referring to interviews with her by foreign Persian-language media outlets in which she spoke in defense of her clients. On January 20, Sadegh Larijani, the head of the Judiciary, repeated the government's warning that lawyers should refrain from giving interviews that “damage our Islamic system of governance.”[83]

Since her arrest Human Rights Watch had other rights groups have repeatedly called on the Iranian authorities to release her unconditionally, and allow her regular visitation rights by her family. In November 2012 the European Parliament awarded Soutoudeh and the Iranian filmmaker, Jafar Panahi, the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought.[84]

In February 2011, a revolutionary court sentenced Mohammad Ali Dadkhah, cofounder and spokesperson for the Center for Defenders of Human Rights, to nine years in prison and banned him from teaching in universities and practicing as a lawyer for 10 years.[85] On April 28, 2012, Dadkhah learned that an appeals court had affirmed the lower court’s ruling. Authorities notified him that he would soon be summoned to serve his prison term.[86] Authorities transferred him to Evin prison on September 30, 2011. In February 2011, another revolutionary court sentenced Khalil Bahramian to 18 months in prison on charges of “propaganda against the state” and “insulting the head of the judiciary,” and imposed a 10-year ban on his practicing law.[87]

On March 4, 2012, Abdolfattah Soltani was convicted and sentenced to 18 years in prison on national security charges after two court sessions. The court’s judgment bars Soltani from practicing law for 20 years after his release because “the accused has used the law as a tool and cover to commit … crimes.” The sentence also requires Soltani, a Tehran resident, to serve his term “in exile” in a prison in the town of Borazjan, more than 600 kilometers south of the capital, in Bushehr province, because “his presence inside a Tehran prison will cause corruption.”[88] Authorities had previously alleged that Soltani, who had earlier spent time in Evin prison, improperly provided legal advice to other prisoners.[89]

Branch 26 of Tehran’s revolutionary court convicted Soltani of several national security charges, including “propaganda against the state,” assembly and collusion against the state, and establishing the CDHRs, the nongovernmental organization that Soltani co-founded with Ebadi in 2003 which the government says is illegal. The court also convicted Soltani of “receiving funds through illegitimate means,” referring to a human rights prize from the German city of Nuremberg which he received in 2009.[90] An appeals court later reduced Soltain’s prison sentence to 13 years but upheld the 20-year ban on practicing law.[91]

At least eight other lawyers, including Ebadi, Mohammad Mostafaei, Mohammad Olyaeifard and Shadi Sadr, have been forced to leave the country as a result of repeated arrests, detention, and harassment. Mohammad Mostafaei fled Iran after authorities repeatedly summoned him for questioning and detained his wife, father-in-law, and brother-in-law.[92]. Mostafaei represented high-profile defendants such as Sakineh Mohammadi Ashtiani, a woman sentenced to death by stoning, and numerous juvenile detainees on death row.[93] He is currently residing in Norway. Another one of Ashtiani's lawyers, Houtan Kian, is also in prison.[94]

More recently, Olyaeifard, another prominent Iranian lawyer who represented many high profile cases before Iran’s civil and revolutionary courts, was forced to leave the country after serving a one year prison sentence for “propaganda against the state,” imposed by the authorities because he spoke out against the execution of one of his clients during interviews with international media.[95]

III. Refugees’ Stories

Protesters

Mohammad-Reza Bigdelifard

Mohammad-Reza Bigdelifard, now a refugee in Turkey, told Human Rights Watch that he, his wife, and his brother-in-law worked as volunteers for a civil society group that supported the presidential campaign Mir Hossein Moussavi.[96] They were in charge of voting research and polling in various neighborhoods in Tehran, and coordinated their work with media outlets such as the official Iran Labor News Agency. In June 2009, Bigdelifard, his wife, and his brother-in-law joined several peaceful demonstrations in Tehran protesting the outcome of the presidential election.[97]

On Wednesday, June 17, Bigdelifard and his wife participated in a large demonstration at Tehran’s Haft-e Tir Square. Bigdelifard told Human Rights Watch that at one point during the demonstration, someone took a picture of the two of them standing behind a large banner that read: “Dust and Trash.”[98] Both Bigdelifard and his wife were wearing masks covering a portion of their faces.

The next day, Thursday, June 18, the picture was published widely in media outlets, including the reformist Iranian daily Etemad-e Melli, Hayat-e No, and websites such as the BBC. About a month later security forces raided Bigdelifard’s home in Tehran. They arrested him and confiscated his personal belongings, including his computer, documents, and CDs. Bigdelifard was handcuffed, taken to a parked car waiting outside, and blindfolded. He was transferred to an unknown location, possibly a secret detention facility, and kept there for approximately 34 days. He said he was blindfolded and cuffed most of the time.

Bigdelifard told Human Rights Watch that his captors routinely subjected him to physical and psychological torture. His captors regularly beat and whipped him, and he endured numerous interrogation sessions during which his interrogators accused him of having links with armed groups working to destabilize the state, as well as with opposition and reformist figures, and dissident sects. Authorities primarily relied on information gathered at his home during the day of the arrest in order to get him to confess to these trumped-up charges. Bigdelifard said that on several occasions authorities threatened him with execution, and carried out mock executions during which he (and several others) had nooses placed around their necks. On at least one occasion, authorities kicked the chair underneath his legs, but he simply fell to the ground.

Bigdelifard also told Human Rights Watch that his captors threatened him with sexual assault if he did not cooperate with interrogators and confess to his “crimes.”

One time my interrogator asked me to write down whatever he wanted me to. “If you don’t do what I say I’ll pull down your pants and fuck you,” he said. I refused. So he pushed me on a desk and pulled down my pants. I began to cry. He called someone else over. I could feel the warmth of someone’s penis against my back. I told him I’d write whatever he wanted. But he said it was too late.[99]

Bigdelifard said his interrogator did not act on the threat, but forced him to write down his confessions with his pants down.

Bigdelifard was eventually released from detention through the efforts of his brother, who bribed an influential member of the Revolutionary Guards. As a condition of his release, he was instructed not to discuss his experiences with anyone, and ordered to leave the country at once. He lived in hiding in a city in northern Iran for approximately eight months prior to escaping to Turkey. His wife and brother-in-law, who had escaped arrest and were in hiding themselves, joined Bigdelifard for the cross-border journey to Turkey.[100]

Shahram Bolouri

Shahram Bolouri, 27, also participated in protests following the disputed 2009 presidential election. He told Human Rights Watch that he documented violence against peaceful protesters by security forces. He disseminated photographs and videos of the post-election violence and provided eyewitness accounts to various media outlets. Prior to his 2009 election activities, Bolouri was a member of the Kurdish Society, an NGO in Tehran, and cooperated with other civil society organizations.

On June 23, 2009, security and intelligence agents raided his home in Tehran and arrested him. They held him in Tehran’s Evin prison for almost 8 months, 45 days of which was in solitary confinement. Bolouri told Human Rights Watch that authorities kept him in wards 209 and 240, controlled by the Ministry of Intelligence, before transferring him to the general ward. Bolouri said interrogators and prison guards subjected him to severe psychological as well as physical ill-treatment and torture.

My solitary cell [in Ward 240] measured 2.5 by 1 meter. It had a toilet and no windows. Prison guards would often come in and order me to stand, sit, and perform odd tasks just because they could. One of them once said to me, “You look like an athlete. Select your sport. Stand up and sit down for me. One hundred times, and make sure you count!” He made me do this several times even though I had a busted leg. I was sweating profusely but they didn’t let me shower. After two weeks the same guy opened the door to my cell and said, “Why does it smell like shit in here?” He ordered me to go take a shower and wash my clothes.[101]

On February 16, 2010, more than six months after he was detained, authorities released Bolouri on bail in the unusually high amount of US$ 200,000 after preventing his family from posting the amount for weeks. Bolouri said that the financial and psychological pressure authorities put on his family was sometimes worse than what he endured in prison. Human Rights Watch has documented numerous other instances where authorities required families to post unusually high bail amounts as part of a systematic strategy to harass detainees and their families.

In October 2010, a revolutionary court in Tehran sentenced Bolouri to four years in prison on charges of “assembly and collusion against the state by participating in protests and communicating with foreign broadcasts and disseminating news.”[102] Bolour appealed, but in June 2011, the Judiciary issued another ruling increasing his sentence to four years and six months. Bolouri decided to leave Iran after increasing pressures and harassment against him and his family following the appeals court ruling. He lodged a refugee claim with the UNHCR field office in Iraq on July 15, 2011, and is now seeking refugee status and resettlement in a third country.[103]

Media Byezid

Media Bayezid, a student activist and blogger previously expelled from Esfahan University after he participated in Student Day protests in 2005, joined Mehdi Karroubi’s presidential campaign in 2008. On the evening of June 12, 2009, Bayezid and others in Karroubi’s campaign were responsible for monitoring the vote count by the Ministry of Interior. He told Human Rights Watch that he and colleagues working for Mousavi’s campaign reported some voting irregularities to authorities. Instead of looking into them, Ministry of Interior officials warned both Karroubi and Mousavi’s campaigns that if there were any “disruptions” they would be held responsible.

Bayezid and others from Karroubi’s campaign went to Tehran to join post-election demonstrators after the official results were announced. He said he returned to Saqqez on November 7, which is when his problems began.

I got a call to meet someone at Payam-e Nur University in Saqqez when I returned who said he wanted to meet me. When I went there I noticed a green car with two persons who approached me. One of them said someone had complained that I was harassing them on the phone and I need to be questioned by [the police.] They put me in car, shoved my head down, and sped away. I later found out they were Ministry of Intelligence agents.[104]

He continued:

We went to the local setad-e khabari[105] of the Ministry of Intelligence. I was blindfolded. The interrogator came into the room and began accusing me of having contacts with Kurdish guerrilla groups. My father was in Koya [Iraqi Kurdistan] and I had crossed the border illegally into Iraqi Kurdistan several times. He accused me of having contacts with PJAK [Kurdish Party for Free Life of Kurdistan] and other banned Kurdish parties. When I refused to admit these contacts he slapped me and said, “This is not your aunt’s house!” Then he said they had been tapping my phone for a while and played recordings of my conversations.[106]

Bayezid said his interrogator questioned him for seven or eight hours. Authorities beat and harassed him several times during the 13 days they kept him at the Ministry of Intelligence detention facility. They eventually released Bayezid, but continued to summon him in for further interrogations until he decided to leave the country.[107]

Minority Rights Activists

Ahmad Mamandi

Hezha (Ahmad) Mamandi, a Kurdish rights activist, was one of the earliest members of the Human Rights Organization of Kurdistan (HROK). The judiciary initially sentenced him to an 11-year prison sentence in Evin prison on various national security-related charges. He told Human Rights Watch that intelligence agents had arrested him numerous times since 2005 because of his activities with HROK and other local rights groups.

I was at Azad University in Mahabad collecting signatures [in 2006] when several intelligence agents arrested me and another colleague, put us in a car, and drove us to the local detention facility. They interrogated me for two weeks. They asked lots of questions about HROK and its relations with America. They beat me several times, but were careful not to hit me in the face. I had no access to a lawyer. After two weeks they sent me and my colleague to a Mahabad revolutionary court. The court session lasted about two to three minutes. When we tried to speak to the judge he kicked us out of the courtroom. They transferred us to the central prison in Mahabad and I found out a bit later that we’d been sentenced to 20 months imprisonment for acting against the national security and disturbing the public.[108]

Mamandi told Human Rights Watch that on appeal the Judiciary decreased his sentence to 10 months and authorities freed him in 2006. Upon release, he continued his underground activities with HROK, but after authorities arrested Kaboudvand and Saman Rasoulpour, two of the group’s leaders, in 2006 and 2007 respectively, the group scaled back its activities.

In 2010, after the execution of Farzad Kamangar and several other Kurdish activists, Mamandi and his colleagues at HROK helped organize a region-wide strike in Iran’s Kurdish areas. Mamandi said the strike was effective and angered the authorities. He discovered that Intelligence agents had identified him and several others as organizers of the strike.

Several days later, on May 22, 2010, Manandi fled to Iraqi Kurdistan.[109]

Amir Babekri

Amir Babekri was a teacher and journalist in Piranshahr, a Kurdish-majority city in West Azerbaijan province. Babekri joined the HROK in 2005 and worked on various rights issues affecting Iran’s Kurds. He told Human Rights Watch that agents from the Revolutionary Guards intelligence unit arrested him at the primary school where he was teaching in December 2007.

Three armed men stuffed me into a Toyota and took me to a local detention facility. There they tried connecting me to Kurdish political parties. I rejected this. They threatened to send me to [the northwestern city of] Orumiyeh if I refused to cooperate. I told them to go ahead and do it. They hit me several times the last night I was there before being transferred to Orumiyeh but I was not tortured.[110]

At the Orumiyeh detention facility, he continued,

There were around 40 people in two separate rooms. The authorities had accused some of them with having ties to PJAK.[111] Every day there were interrogations, and we heard lots of screaming. I was interrogated for a total of 18 days, but they transferred me for questioning to another facility which was about five to six minutes away by car. I was blindfolded. There they subjected me and the others to various forms of ill-treatment. Sometimes they threw us out in the snow. Other times they would handcuff us to a wall and force us to stand on the tips of our toes. They also hit us over the head with batons.[112]

Babekri said his interrogator asked him lots of questions about his contacts at HROK. He said he was finally forced to acknowledge his membership in HROK, but refused to give up names of others who worked in the HROK underground network. Authorities eventually charged Babekri with moharebeh, or enmity against God, membership in an illegal group, and illegally crossing into Iraqi Kurdistan. He told Human Rights Watch that his indictment in a revolutionary court in Orumiyeh lasted two to three minutes. He had no legal representation, and recalled there were several Revolutionary Guards officers present inside the courtroom.

After four months the Judiciary tried him during a 30-minute court session. This time he had a lawyer present.[113]They had dropped the more serious moharebeh charge, but he was convicted on the charge of “propaganda against the state” and membership of HROK. The judge sentenced him to one year three months imprisonment.

As a result of continuing pressure by local authorities and his inability to teach in Piranshahr, Babekri decided to leave Iran and lodged a refugee claim with UNHCR in Iraqi Kurdistan on July 15, 2009.[114]

Rebin Rahmani

Kurdish rights activist Rebin Rahmani told Human Rights Watch that security forces arrested him on November 19, 2006, in Kermanshah, the capital city of the western Iranian province of the same name. At the time he was involved in a project researching the prevalence of drug addiction and HIV infections in Kermanshah province. After his arrest, Rahmani spent approximately two months in detention facilities run by the Ministry of Intelligence, and was interrogated by intelligence agents in both Kermanshah and Sanandaj, the main city in the adjacent Iranian province of Kurdistan. He told Human Rights Watch that during his time in these two facilities there he was subjected to several rounds of interrogation accompanied by physical and psychological torture.

In January 2007, a revolutionary court sentenced Rahmani to five years’ imprisonment on charges of “acting against national security,” and “propaganda against the state.” The sentence was handed down after a 15-minute trial during which Rahmani had no access to a lawyer. In March of that year his sentence was reduced to two years on appeal.

After his appeal Rahmani was primarily kept in Kermanshah’s Dizel Abad prison, but was transferred to detention facilities operated by the Ministry of Intelligence on several occasions for additional interrogations. He told Human Rights Watch that during his interrogations he was again subjected to physical and mental abuse amounting to torture, and kept in solitary confinement for long periods of time in an attempt to force him to falsely confess to links to armed Kurdish separatist groups. Interrogators also threatened to arrest his family members, and eventually arrested his brother in June 2008 in part to put pressure on Rahmani. As a result of these pressures, Rahmani attempted suicide on two occasions. Intelligence authorities were not able to bring any additional charges against him, he said.

Upon his release from prison in the latter part 2008, Rahmani learned that he had been dismissed from university and could no longer continue his education. He told Human Rights Watch that he decided to join the local rights group, Human Rights Activists in Iran (HRA), but used a pseudonym because he was afraid he would be rearrested by authorities. Prior to his eventual escape to Iraqi Kurdistan due to mounting pressure against him and his family, Rahmani interviewed victims and their families and prepared reports for HRA, most of which focused on rights violations perpetrated by the government in Iran’s Kurdish regions. He was also responsible for administering Kurdish-language content of the HRA website.[115]

During the crackdown in March 2010 against rights groups including HRA in Tehran and other major cities (described above), Rahmani escaped arrest because he was not identified as an active member of HRA at the time. But in May 2010, following his participation in a rally against the execution of several Kurdish political prisoners, local authorities put Rahmani under surveillance. In December 2010, security forces raided his house shortly after he attended a gathering outside Sanandaj prison to protest the imminent execution of Habibollah Latifi.[116]

Rahmani felt forced to escape to Iraqi Kurdistan and registered with the UNHCR office in Erbil on March 6, 2011.[117]

Fayegh Roorast

Fayegh Roorast, a Kurdish activist and law student at Orumiyeh University, told Human Rights Watch that prior to his arrest in January 2009 he cooperated with several rights and civil society groups such as HROK, HRA, and the One Million Signatures Campaign. He said Ministry of Intelligence agents began targeting him around the time when the judiciary sentenced Farzad Kamangar to death, in March 2008.[118] Roorast had conducted several interviews with foreign media outlets regarding the arrest of Kamangar, Zainab Bayazidi and other Kurdish rights activists.[119]

On January 25, 2009 intelligence agents attacked Roorast’s father’s shop and arrested his father. A little while later they entered Roorast’s home in Mahabad and seized his personal belongings, but did not arrest him at that time. Two days later Roorast as well as his brother, sister, and aunt were all summoned to the local Ministry of Intelligence office in Mahabad. He said officials accused all of them of working with banned Kurdish opposition groups, including the PJAK. Intelligence officials released the rest of his family but kept Roorast at the detention facility for about 17 days.

At the Mahabad Ministry of Intelligence facility they threatened and harassed me every day. My interrogator played good cop with me to urge cooperation, and bad cop when I refused to do what he wanted. He beat me and threatened to harm, even rape, members of my family. After five days of interrogations and beatings he said to me, “Until now you were only being interrogated. From now on I’m responsible for teaching you lesson.”[120]

Roorast said that he was later transferred to a Ministry of Intelligence detention facility in Orumiyeh.

The authorities held me in solitary confinement for several days. There were three interrogation, or torture, rooms downstairs. I heard lots of horrible sounds coming from there. They took me there about 15 or 16 times. The place reeked of urine and feces. There they subjected me to all types of torture, including hanging me by my wrists on wall so I’d be forced to stand on my toes, applying electric shocks to the tips of my toes and fingers, and beating me up. They asked me why I had kept lists of prisoners’ names and why I’d collected signatures for the One Million Signatures Campaign.[121]

Roorast told Human Rights Watch that he refused to provide names. Authorities released him in early 2010. He left Iran for Iraqi Kurdistan later that summer.

Student Activists

Hesam Misaghi

On January 1, 2010, the Ministry of Intelligence contacted Hesam Misaghi, a student activist and member of the Committee of Human Rights Reporting (CHRR) by phone and summoned him for interrogation. The Ministry of Intelligence agent informed Misaghi that a warrant for his arrest had been issued, and threatened to raid his home if he did not voluntarily report to ministry. Later that day, two other CHRR members who had been similarly summoned to the ministry presented themselves and were promptly arrested.[122]