Delivered Into Enemy Hands

US-Led Abuse and Rendition of Opponents to Gaddafi’s Libya

Summary

All we seek is justice.… We hope the new Libya, freed from its dictator, will have positive relationships with the West. But this relationship must be built on respect and justice. Only by admitting and apologizing for past mistakes … can we move forward together as friends.

—Abdul Hakim Belhadj, military commander during the Libyan uprising who had been forcibly returned to Libya in 2004 with US and UK involvement, Libya, April 12, 2012[1]

When rebel forces overtook Tripoli in August 2011, prison doors were opened and office files exposed, revealing startling new information about Libya’s relations with other countries. One such revelation, documented in this report, is the degree of involvement of the United States government under the Bush administration in the arrest of opponents of the former Libyan Leader, Muammar Gaddafi, living abroad, the subsequent torture and other ill-treatment of many of them in US custody, and their forced transfer to back to Libya.

The United States played the most extensive role in the abuses, but other countries, notably the United Kingdom, were also involved.

This is an important chapter in the larger story of the secret and abusive US detention program established under the government of George W. Bush after the September 11, 2001 attacks, and the rendition of individuals to countries with known records of torture.[2]

This report is based mostly on Human Rights Watch interviews with 14 former detainees now residing freely in post-Gaddafi Libya and information contained in Libyan government files discovered abandoned immediately after Gaddafi’s fall (the “Tripoli Documents”). It provides detailed evidence of torture and other ill-treatment of detainees in US custody, including a credible account of “waterboarding,” and a similar account of water abuse that brings the victim close to suffocation. Both types of abuse amount to torture. The allegations cast serious doubts on prior assertions from US government officials that only three people were waterboarded in US custody. They also reflect just how little the public still knows about what went on in the US secret detention program.

The report also sheds light on the failure of the George W. Bush administration, in the pursuit of suspects behind the September 11, 2001 attacks, to distinguish between Islamists who were in fact targeting the United States and those who may simply have been engaged in armed opposition against their own repressive regimes. This failure risked aligning the United States with brutal dictators and aided their efforts to dismiss all political opponents as terrorists.

The report examines the roles of other governments in the abuse of detainees in custody and in unlawful renditions to Libya despite demonstrable evidence the detainees would be seriously mistreated upon return. Countries linked to these accounts include: Afghanistan, Chad, China and Hong Kong, Malaysia, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, the Netherlands, Pakistan, Sudan, Thailand, and the United Kingdom.

Finally, the report shows that individuals rendered to Libya were tortured or otherwise ill-treated in Libyan prisons, including in two cases where the Tripoli Documents make clear the United States sought assurances that their basic rights would be respected. All were held in incommunicado detention—many in solitary confinement— for prolonged periods without trial. When finally tried, they found that the proceedings fell far short of international fair trial standards.

Most of the former detainees interviewed for this report said they had been members of the Libyan Islamist Fighting Group (LIFG)—a group opposed to Gaddafi’s rule that began to organize in Libya in the late 1980s and took more formal shape in Afghanistan in the early 1990s. At that time, Islamist opposition groups were springing up across the Middle East, North Africa, and Asia in response to governments they deemed corrupt, oppressive, and not sufficiently Islamic.

Libya was no exception. In 1977, several years after Gaddafi took power, he imposed his unique political system, the Jamahiriya, or “state of the masses,” on the country. The government confiscated property, and began regulating every aspect of life, from religion to economics to education, in entirely new and often incomprehensible ways. Many Libyans, including traditional Muslims who were particularly outraged by the changes Gaddafi made to the practice of Islam and considered them blasphemous, expressed their opposition. Gaddafi put down dissent brutally, focusing in particular on Islamist opposition groups who, due to their alignment with Islamist groups abroad and the deep devotion of many members, he treated as a dangerous threat. Those suspected of even the slightest connection with the movement were rounded up, imprisoned, and sometimes executed, including in public and broadcast on television. It is in the context of this crackdown that the LIFG began to organize and set out, from bases both within and outside Libya, to overthrow Gaddafi.

Virtually all the former Libyan detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they fled the country in the late 1980s because of Gaddafi’s repressive policies against organized Islamic opposition groups and against persons perceived to be associated with such groups, due to their religious practices. Some joined the LIFG while in Libya and others once outside the country. All but one said they participated in the fighting in Afghanistan that eventually defeated the Soviet-installed government of Mohammed Najibullah in 1992 and used the training they gained there for LIFG-led anti-Gaddafi efforts.

After the September 11 attacks on the United States, being Libyan without documentation in Afghanistan, and being part of an armed Islamic opposition group, placed these Libyan expatriates at high risk of arrest. That was true even if—as all those interviewed for this report claim—their group was not at war with the West. And so many of them fled, along with their families, moving from country to country, including to destinations such as Malaysia and Hong Kong as well as Mali and Mauritania. It was in these countries that they were taken into custody before being sent elsewhere.

For many of the individuals profiled here, this will be the first time their stories are told because until last year they were locked up in Libyan prisons.

These stories provide new details about serious human rights violations in US detention sites, US and UK collaboration with the Gaddafi government, and the roles of several other countries that assisted in renditions. This information includes:

- New accounts of abuse in secret Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) black sites: Five former LIFG members told Human Rights Watch that they were detained in US run-prisons in Afghanistan for between eight months and two years. The abuse allegedly included: being chained to walls naked—sometimes while diapered—in pitch dark, windowless cells, for weeks or months at a time; being restrained in painful stress positions for long periods of time, being forced into cramped spaces; being beaten and slammed into walls; being kept inside for nearly five months without the ability to bathe; being denied food and being denied sleep by continuous, deafeningly loud Western music, before being rendered back to Libya. The United States never charged them with crimes. Their captors allegedly held them incommunicado, cut off from the outside world, and typically in solitary confinement throughout their Afghan detention. The accounts of these five men provide extensive new evidence that corroborates the few other personal accounts that exist about the same US-run facilities. One of those five, before being transferred to Afghanistan, as well as another former LIFG member interviewed for this report, were also held in a detention facility in Morocco.

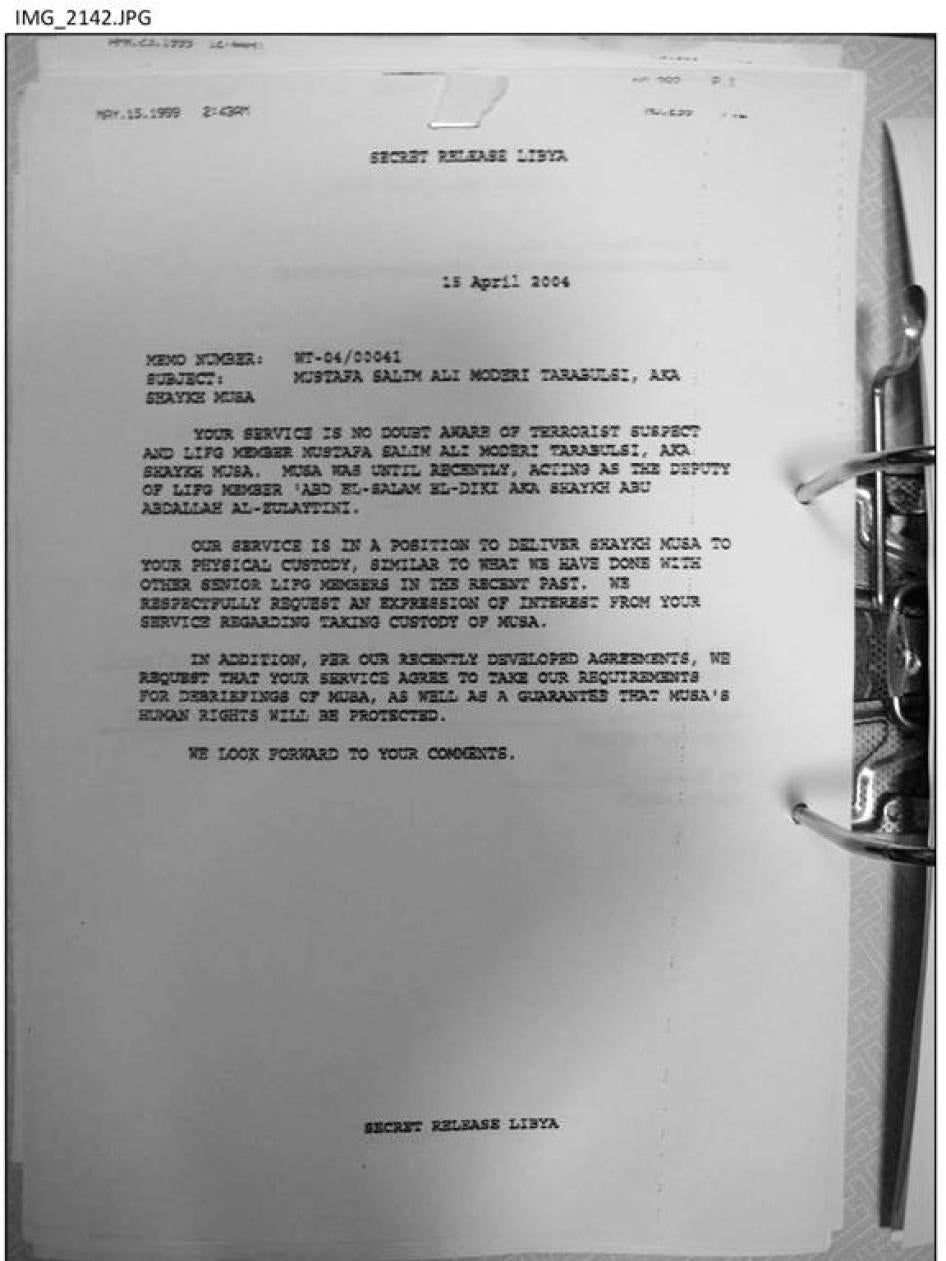

- New evidence of “waterboarding” torture and a similar practice during interrogations: One former detainee, Mohammed Shoroeiya, provided detailed and credible testimony that he was waterboarded on repeated occasions during US interrogations in Afghanistan. While never using the phrase “waterboarding,” he said that after his captors put a hood over his head and strapped him onto a wooden board, “then they start with the water pouring…. They start to pour water to the point where you feel like you are suffocating.” He added that, “they wouldn’t stop until they got some kind of answer from me.” He said a doctor was present during the waterboarding and that this happened numerous times, so many times he could not count. A second detainee in Afghanistan described being subjected to a water suffocation practice similar to waterboarding, and said that he was threatened with use of the board. A doctor was present during his suffocation-inducing abuse as well. The allegations of waterboarding contradict statements about the practice from senior US officials, such as former CIA Director Michael Hayden, who testified to the Senate that the CIA waterboarded only three individuals—Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, Abu Zubaydah, and Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri.[3] Former President Bush similarly declared in his memoirs that only three detainees in CIA custody were waterboarded.[4] Former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld has also denied the use of waterboarding by the US military.[5]

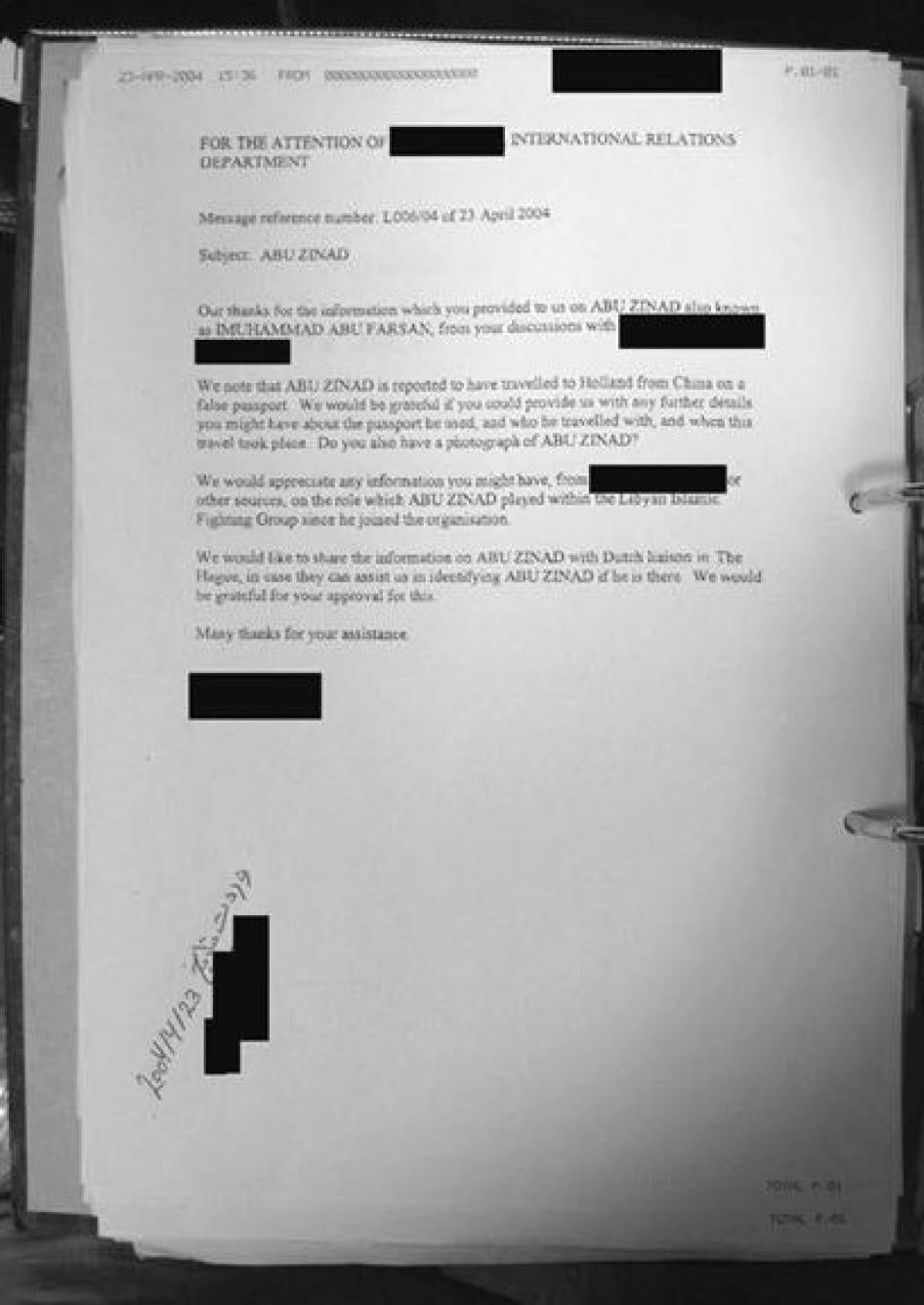

- Unlawful rendition: All interviewees said their captors forcibly returned them to Libya at a time when Libya’s record on torture made clear they would face a serious risk of abuse upon return. All had expressed deep fears to their captors about going back to Libya and five of them said that they specifically asked for asylum. One of them, Muhammed Abu Farsan, sought asylum in the Netherlands while in transit between China and Morocco. He said his asylum application was ultimately denied and he was sent to Sudan, where he held a passport. But Sudanese authorities kept him in detention and, shortly after his arrival, individuals representing themselves as CIA officers interrogated him on three different days. Within two weeks he was sent back to Libya. Though the Netherlands is the only government that actually had provided any of the Libyans we interviewed with an opportunity to challenge their transfer, the Tripoli Documents contain information suggesting Dutch officials might have been aware that Abu Farsan would ultimately be sent to Libya from Sudan. To the extent they knew that there was a genuine risk he would be returned to Libya, they violated his rights against unlawful return.

- More information aboutWestern collusion with the Gaddafi government: The Human Rights Watch interviews and the Tripoli Documents present new details showing a close degree of cooperation among the US, the UK, and other Western governments with regard to the forcible return and subsequent interrogation of Gaddafi opponents in Libya. Ten of the fourteen Libyans interviewed for this report were rendered back to Libya within about year of the date when Libya, the United States and the United Kingdom had formally mended their relations, seven within the five months. The mending of relations was very publically marked by a visit from British Prime Minister at the time, Tony Blair, to Libya on March 25, 2004. The collusion is ironic, given that years later these same governments would end up assisting Gaddafi’s opponents in their efforts to overthrow the Libyan leader. Several of those opponents are now in leadership positions and are important political actors in Libya.

- Ibn al-Sheikh al-Libi: Al-Libi’s case is significant, among other reasons, because the United States relied on statements obtained through his interrogation while in CIA custody to justify the 2003 invasion of Iraq: Al-Libi died in a Libyan prison in 2009—a suicide, according to Libyan authorities at the time—so it is difficult to obtain information about him today. But by talking to family members and others detained with him in Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Libya, Human Rights Watch has pieced together some new details about al-Libi’s time in CIA custody and circumstances surrounding his death. Human Rights Watch also observed photos of al-Libi that Libyan prison officials appear to have taken on the morning of his death which allegedly depict him in the manner he was found in his cell. The photos show bruising on parts of his body.

The United States, Libya, and most of the other countries discussed in this report are party to important international human rights treaties, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. Persons apprehended in armed conflict situations would also have been protected by the Geneva Conventions of 1949. These treaties prohibit not only torture, but all cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment. Importantly, they also prohibit sending an individual to a country where that person would face a genuine risk of torture or ill-treatment.

In discussing rendition policies, former Bush administration officials have tried to justify the forced returns that took place during the administration by saying they always got “promises” from the receiving countries or “diplomatic assurances” the transferees would be treated humanely. As evidenced by US State Department country reports on human rights in the mid-2000s, however, the US government was well aware of the torture and ill-treatment taking place in Libyan prisons.[6] The Gaddafi government’s many executions of its opponents after summary trials would have made it obvious to anyone involved in the rendition of LIFG members to Libya that they would be at grave risk. The US government’s perfunctory resort to diplomatic assurances—unenforceable agreements between governments to not harm a person being transferred, shown in the Tripoli Documents to have been used in two transfers—reflect a callous disregard for the lives and wellbeing of people who the United States never should have returned to Libya.

Several individuals interviewed for this report said they endured physical abuse and mistreatment in Libya, some of which amounted to torture. This included being beaten with wooden sticks[7] and steel pipes;[8] whipped,[9] including with ropes[10] and electric cables;[11] slapped, kicked and punched;[12] and administered electric shocks.[13]

At the same time, other interviewees said they were not subjected to physical abuse in Libyan custody. Some speculated this may have been due to prison reforms initiated by Muammar Gaddafi’s son, Saif Gaddafi, or agreements they had heard were made between the United States and Libya (perhaps diplomatic assurances) that transferees would not be mistreated.[14] But, neither Saif Gaddafi’s reforms nor US diplomatic assurances, if obtained, appear to have protected those detainees who were subjected to torture and ill-treatment. Nor did they protect detainees from being placed in solitary confinement—which can amount to torture—ensure their access to family members and legal counsel, or make sure they were promptly charged and fairly tried. Typically detainees had no lawyers and were denied family visits, sometimes for as long as two years.[15] All of those interviewed said they were held for years before finally being charged with any offense. Once charged, they were appointed a lawyer to whom they either never spoke or who did not assist in their defense.[16] They faced summary trials, and all detainees interviewed for this report were convicted, receiving sentences of lengthy prison terms up to life imprisonment, or the death penalty. At least three said they were subsequently interrogated in Libyan prisons by US, UK, or other foreign agents.[17]

Summary of the Cases

Detentions in Afghanistan and Morocco: Of the men interviewed for this report, the five who experienced the worst abuses and spent the longest period in secret US detention are Khalid al-Sharif (Sharif); Mohammed Ahmed Mohammed al-Shoroeiya (Shoroeiya); Majid Mokhtar Sasy al-Maghrebi (Maghrebi); Saleh Hadiyah Abu Abdullah Di’iki (Di’iki); and Mustafa Jawda al-Mehdi (Mehdi). All but Mehdi appear to have been held in the same locations for their first period of detention which they all said was in a US-run detention facility in Afghanistan. The four were then moved to a second location, apparently also in Afghanistan, to which Mehdi was later brought. In total, Sharif was in both locations for two years, Shoroeiya for about 16 months, Maghrebi for about eight months, and Di’iki also for about eight months. Mehdi was only in the second location and he appears to have been detained there for about fourteen months. Prior to his detention in Afghanistan, Di’iki said he was also held in a facility in Morocco for about a month where he said he was interrogated by US personnel though it is not clear if they were running the facility. In addition to these five, Human Rights Watch also interviewed Mustafa Salim Ali el-Madaghi (Madaghi), who was described in the Tripoli Documents as Di’iki’s deputy.[18] He was arrested in Mauritania, sent to Morocco, held there for about five weeks, and then rendered to Libya. All six were senior members of the LIFG. Khalid al-Sharif, deputy to Head of the LIFG, Abdul Hakim Belhadj (see below), being the most senior member.

Transfers to Libya That Began in Asia: For three interviewees, their returns to Gaddafi’s Libya began in Asia. Two of these three cases—those of Abdul Hakim Belhadj and Sami Mostafa al-Saadi, are already well documented. Information about US and UK involvement in their renditions was revealed when the Tripoli Documents were discovered last year and a number of the documents made public.[19] Belhadj is the former head of the LIFG and a longtime opponent of Gaddafi. He and his wife were taken into custody in Malaysia with the help of the United Kingdom’s Secret Intelligence Service (commonly known as MI6) and detained for several days by the CIA in Thailand. The United States then sent him to Libya around March 9, 2004. Libyan intelligence Chief Musa Kusa had Belhadj brought directly to him. “I’ve been waiting for you,” he reportedly told Belhadj.[20] Belhadj’s transfer occurred just weeks before UK Prime Minister Tony Blair flew to Tripoli on March 25 for a very public rapprochement with Gaddafi.[21] The same day, Anglo-Dutch oil giant Shell announced it had signed a deal worth up to £550 million (approximately $1 billion US) for gas exploration rights off the Libyan coast.[22]

Saadi had been a senior LIFG leader and was the group’s religious leader and religious law expert. The Tripoli Documents contain communications from the CIA offering to help the Libyan government secure Saadi’s return to Libya and confirming MI6 involvement as well. Saadi was rendered to Libya from Hong Kong just days after Blair’s visit to Libya. Five other former LIFG members interviewed for this report were also rendered to Libya that year, and two more the following April. Communications contained in the Tripoli Documents, relating to Belhadj and Saadi, are a key part of a lawsuit against the UK government.[23] They have also formed the basis of an investigation by the UK police into the government’s role in their rendition.[24]

In addition to these eight, Human Rights Watch interviewed another senior LIFG member, Muhammed Abu Farsan, who had been with Belhadj and Saadi in Asia before they were detained. As described above, Abu Farsan sought but failed to obtain asylum in the Netherlands, which sent him to Sudan. In Sudan he was interviewed by individuals representing themselves as being from the CIA on three different occasions. Within two weeks, Sudan returned him to Libya.

Transfer from Guantanamo Bay: We also interviewed Abdusalam Abdulhadi Omar as-Safrani, who as of this report’s writing was one of two former Guantanamo detainees sent back to Libya by the US. He said he was not a member of the LIFG. He was detained with Ibn-al-Sheikh al-Libi (see below) by US and Pakistani forces before being sent to Guantanamo.

Ibn al-Sheikh al-Libi (Sheikh al-Libi):Sheikh al-Libi, also reportedly not a member of the LIFG, was held in US custody for years, allegedly tortured, and then rendered to Libya. We could not interview him for this report because he died in Libyan custody, allegedly by suicide. His rendition and torture is of particular importance because it produced intelligence that the CIA itself has recognized was unreliable but that nevertheless played a significant role in justifying the US invasion of Iraq in 2003.

Detainees Rendered from African Countries to Libya: We interviewed four other Libyans picked up in different places in Africa and then transferred to Libya: one from Sudan, Ismail Omar Gebril al-Lwatty (Lwatty); one from Chad, Mafud al-Sadiq Embaya Abdullah (Embaya); and two from Mali, Abdullah Mohammed Omar al-Tawaty (Tawaty) and Othman Salah (Salah). These interviews contained less evidence than the others of foreign or Western government involvement in the actual transfer, though there are indications that Western governments were involved in the initial apprehensions and subsequent interrogations. The African countries themselves, however, were equally obliged not to render these individuals to Libya, without process and against their will.

Most of the Libyans profiled in this report were imprisoned until February 16, 2011, when the uprisings against Gaddafi began. LIFG leader Abdul Hakim Belhadj, his deputy, Khalid Sharif, and LIFG religious leader Sami al-Saadi were released a year earlier, on March 23, 2010, as part of a negotiated release of hundreds of prisoners. Belhadj, Saadi and Sharif had to publically renounce their aim of overthrowing the government by force as part of the deal.

Many of those interviewed were also involved in the

uprisings against Gaddafi. Sharif, Saadi, and Di’iki were all rearrested

during this time for anti-Gaddafi activities and held until August 2011, when

Tripoli fell to rebel forces. Belhadj commanded a brigade that played a key

role in the uprisings and the taking of Tripoli. Shoroeiya, Sharif, and others

interviewed for this report said that many former LIFG members who managed to

escape arrest after the uprisings began, but are not profiled here, participated

politically in the uprisings and militarily in organizing and training rebel

forces. Belhadj and Saadi both ran as candidates for their respective political

parties during the July 7, 2012 elections.[25]

US diplomats have engaged with Belhadj and his party since they

emerged as important players in Libya’s new democratic landscape, and

several US Senators, including John McCain, have met with him. Sharif is now head of the Libyan National Guard. One of his

responsibilities is providing security for facilities holding high value

detainees (mostly officials of the former Gaddafi government) now in government

custody. Di’iki also works at the Libyan National Guard and has similar responsibilities.. Mehdi and

Shoroieya are prominent members of the same political parties to which Belhadj

and Saadi belong, respectively.

Key Recommendations

To the United States Government

- Consistent with its obligations under the Convention against Torture, investigate credible allegations of torture and ill-treatment since September 11, 2001 and implement a system of compensation to ensure all victims can obtain redress.

- Acknowledge past abuses and provide a full accounting of every person that the CIA has held in its custody pursuant to its counterterrorism authority since 2001, including names, dates they left US custody, locations to which they were transferred, and their last known whereabouts.

- Create an independent, nonpartisan commission to investigate the mistreatment of detainees in US custody anywhere in the world since September 11, 2001, including torture, enforced disappearance, and rendition to torture.

To the Government of the United Kingdom

- Provide a full accounting of the involvement of British security services in the detention or transfer of individuals to other countries without due process since September 11, 2001.

- Set up a new, judge-led inquiry into the UK’s involvement in detainee abuse and renditions to torture with full independence from the government and authority to allow it to establish the truth.

To the Government of Libya

- Promptly investigate all allegations of torture and ill-treatment in detention facilities run by the state and armed groups in a thorough and impartial way.

- Hold accountable all those responsible for using torture or ill-treatment against persons in custody.

To the Governments of Pakistan, the Netherlands, China, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Thailand, Chad, Mauritania, Mali, Morocco, and Sudan

- Conduct a thorough and impartial investigation into the role each government played in either the detention and abuse or the transfer or rendition of individuals identified in this report to Libya, where they faced a substantial risk of torture or persecution.

- Where warranted, prosecute individuals found to have engaged in torture or cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment and provide a means for victims to obtain redress.

Methodology

This report is based primarily on interviews Human Rights Watch conducted during a research trip to Libya from March 14 to March 27, 2012; documents that Human Rights Watch discovered in Libyan foreign intelligence chief Musa Kusa’s office on September 3, 2011; and Human Rights Watch research on unlawful rendition and secret detention by the United States and other governments over the past decade.

During its March 2012 trip to Libya, Human Rights Watch conducted in-depth interviews with 14 former detainees who had been transferred to Libya between 2004 and 2006. Before each interview, we informed interviewees of its purpose and the kinds of issues that would be covered, and asked whether they wanted to participate. We informed them that they could discontinue the interview at any time or decline to answer specific questions without consequence. We did not offer or provide incentives to persons we interviewed. We conducted each interview individually and in private.

Human Rights Watch was previously aware that seven of these individuals had been transferred to Libya. We had already interviewed four of them in 2009 while they were still in Libya’s Abu Salim prison, but had conducted those interviews in an open courtyard, occasionally within the earshot of guards.[26] The fall of the Gaddafi government and the prisoners’ release from detention provided Human Rights Watch with an opportunity to speak to them in private, without the stress of prison conditions, and in greater depth about their experiences.

These interviews and documents led Human Rights Watch to other individuals who had also been unlawfully rendered, detained, and interrogated with varying levels of foreign government involvement. In addition, Human Rights Watch worked with Sheikh Othman, a former LIFG member who worked in the Tripoli Military Defense Council. He was in charge of compiling the names of those who had been returned to Libya against their will, with foreign government involvement. He himself had been rendered to Libya from Mali in 2006. Othman provided Human Rights Watch with the names and contact information for 21 former prisoners who he said were returned to Libya during the Gaddafi era with US, UK, or other foreign government involvement. Much of this information overlapped with information we already had, but some of it was new. Of those on Othman’s list that we were not able to interview, one was no longer alive (Ibn al-Sheikh al-Libi). Another, Abu Sufian Ibrahim Ahmed Hamuda Bin Qumu, the only other Guantanamo detainee to be returned to Libya besides Abdusalam Abdulhadi Omar as-Safrani, refused to speak with us. We were unable to reach six others. As a result, we were not able to confirm or deny these other alleged transfers to Libya. In addition, Othman said that another 15 people had been turned over to Libya from prisons in Sudan, more than 70 from Saudi Arabia, and at least eight from Jordan. Due to limited time, Human Rights Watch was not able to investigate these claims.

Human Rights Watch interviewed some family members of people who had been returned to Libya, as well as family members and former cellmates of Ibn al-Sheikh al-Libi, who died while in Libyan custody.

Tripoli Documents

On September 3, 2011, Human Rights Watch discovered a number of Gaddafi-era files, abandoned, in the offices of former Libyan intelligence chief Musa Kusa in Tripoli.[27] Scores of those documents—several of which are presented here for the first time—provide important information on the high level of cooperation between the United States and the United Kingdom in the rendition of Gaddafi’s political opponents to Libya. (See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the documents drawn on in this report.)

The documents include communications between Musa Kusa’s office and the CIA, and between Kusa’s office and the MI6. They show a high level of cooperation between the United States, the United Kingdom, and the government of former Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi on the transfer of Gaddafi’s opponents into Libyan custody. The documents are significant because they shed light on the still opaque CIA renditions program, identify former detainees by name, and provide corroborating evidence in several specific cases, most notably confirming the involvement of the US, the UK, and other governments.

Past Human Rights Watch Interviews in Libya

Since the September 11, 2001 attacks, Human Rights Watch, journalists and other nongovernmental organizations have reported on CIA secret detention sites, tracked the names of missing detainees believed to be in US custody, and requested information as to their whereabouts.[28] In 2006 and 2007, Human Rights Watch received reports from Libyans abroad that several individuals who had been in US custody had since been sent back to Libya. Some media outlets also reported these returns.[29] By February 2009, Human Rights Watch had the names of seven Libyans we believed had been detained by the CIA and transferred to Libya. In April 2009 Human Rights Watch got access to the notorious Abu Salim prison in Tripoli, the main prison where the government held political prisoners and the site of a massacre in 1996 where roughly 1,200 inmates were killed within a few hours. During the 2009 visit, we confirmed that five of the seven had indeed been transferred to Libyan custody and we were able to interview four of them, though only for a limited period of time and not entirely in private. The fifth, Ali Mohammed al-Fakheri, also known as Ibn al-Sheikh al-Libi, declined to speak with us. Two weeks later, according to the Libyan government, he committed suicide.[30]

I. Background

Libya from the 1970s to the 1990s

Twelve of the fifteen men profiled in this report said they left Libya between 1988 and 1990. Of the three others, one left in 1991 and the others in 1996.[31] Libya at the time was a brutal police state.[32] Dissidents were arbitrarily arrested and held for years without charge, and often for long periods in incommunicado detention.[33]Torture of those in custody was rampant.[34] Family members of suspected opponents of the government were harassed, threatened, and detained.[35] It was a country in which the death penalty could be imposed on “anyone who calls for the establishment of any association or party which is against the Revolution in purpose and means.”[36]

Leading up to this period Gaddafi had developed a unique political philosophy, a hybrid of socialism and Islam called the Third Universal Theory, which sought independence from communism and capitalism. This theory was enshrined in the “Green Book,” which he wrote to present his theory of a system of government called Jamahiriya, or “state of the masses.”[37] According to the Green Book, the Jamahiriya system was the final evolution of democracy, because citizens did not elect representatives but participated themselves directly in governmental affairs. All citizens were obliged to participate in Basic People’s Congresses in their local districts, where they could debate all matters of government. Parliaments were considered “a misrepresentation of the people,” and parliamentary governments were “a misleading solution to the problem of democracy.” Political parties were considered “contemporary dictatorships.”[38] New laws banned any group activity based on a political ideology opposed to these views.[39] As Gaddafi once declared, “It [the revolution] is a moving train. Whoever stands in its way will be crushed.”[40]

Gaddafi created Revolutionary Committees, an extensive surveillance system that mobilized citizens to support his political agenda.[41] The rights to freedom of speech and assembly were virtually non-existent.[42] Both local and international phone calls were routinely monitored, as evidenced by the extensive monitoring equipment found after Gaddafi’s fall.[43] In the years that followed, police and security forces arbitrarily detained hundreds of Libyans who opposed, or authorities feared could oppose, the new system, subjected them to arbitrary detentions, and many were killed.”[44] Libyan authorities referred to these individuals as “stray dogs.”[45] On many occasions, the executions were carried out in public and broadcast on television.[46]

Gaddafi also made major changes to the practice of Islam in Libya that he expected others to follow.[47] For example, the second source of authority in Sunni Islam, the Sunnah (the acts and sayings of the Prophet as told by his companions), was discarded.[48] The Islamic calendar was changed so that it no longer started with the date of the Prophet’s migration from Mecca to Medina, but rather with the date of his death ten years later.[49] Libya began fasting for the holy month of Ramadan on a different day from the rest of the Middle East.[50]

The most contentious of these changes was the discarding of the second Sunnah, which was deeply offensive and sacrilegious to Muslims, and not just those in Libya. Though Gaddafi was not the only one advocating this at the time, it was very much a minority position and put him at odds with the clerical establishment, as well as Islamists.[51]

In the early 1980s, a series of fatwas were issued against Gaddafi which proclaimed him a heathen.[52] Libyans who were opposed to Gaddafi’s changes began organizing. In turn Gaddafi stepped up surveillance and repression against them.[53] Many victims of the detentions, and killings going on at the time were members of Islamist opposition groups.[54] The former head of Libya’s foreign intelligence service, Musa Kusa, once reportedly boasted to foreign visitors that he monitored domestic Islamic extremists so closely that he knew the name of every Libyan with a beard.[55]

Even fleeing the country did not mean escaping Gaddafi’s reach. In the 1970s and 80s, Gaddafi’s government reportedly formed assassination squads that tracked down and killed his opponents abroad.[56]

Flight from Libya

State restrictions on the practice of Islam were the main reason most of the men interviewed for this report said they had left Libya, though some also cited more general freedom of expression issues. “I had a beard when I was at the university and it was obvious I used to pray,” said Mustafa Salim Ali el-Madaghi, one of the men who fled Libya in 1990 only to be sent back by foreign governments. “I was afraid to show anything like that because such an appearance was considered an act of outright opposition. I started to be followed by a security person…. All of this plus the continuous arrests of people made me decide to leave Libya because I knew that if I stayed I would end up in prison.”[57] Another former detainee, Abu Farsan, said he prayed at home and avoided the mosque because “going to the mosque was the route to prison.”[58]

Those interviewed said that after they had left the country, a number of friends and relatives who stayed behind were harassed, detained, or killed.[59] After he fled Libya in 1988, Sami al-Saadi said that security forces repeatedly harassed his elderly father, even breaking into his house and beating him. Two of Saadi’s brothers were also arrested and imprisoned in Tripoli’s high security prison, Abu Salim, where many political prisoners were held. After being held for several years without trial, both lost their lives in the 1996 Abu Salim massacre, in which prison guards killed some 1,200 prisoners after a revolt over prison conditions.[60]

All of the men interviewed for this report were in their late teens or early twenties when they left Libya. Some of them were founding members of the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG), discussed below. After leaving Libya, most were among a large group of Libyans who went to Afghanistan around this time, where they joined other Libyans there fighting with rebel groups, referred to broadly as “the mujahidin,” against Soviet military forces and the Soviet-backed Afghan government.[61] The United States, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, and several other governments backed the Afghan rebels with covert funding, weapons, and training for the fighters.[62] The Saudi government for example, contributed $350 to $500 million per year for the mujahidin through a US government controlled Swiss bank account.[63] “In Saudi Arabia, everyone was talking about the Afghan Jihad,” said Osmail Omar Gebril al-Lwatty, one of the rendered Libyans who fought in Afghanistan. “They made it so easy for us. There were camps where you could live normally and train, in Jalalabad and Khost, then you went to Peshawar to get equipped.”[64]

A well-known Palestinian cleric at the time, Abdullah Azzam, authored numerous statements and texts, one of which was published as a book, considered by many to constitute a fatwa (legal pronouncement), in which he argued that Muslims had a personal obligation to defend Afghanistan against the Soviets.[65] “I believed the people in Afghanistan were oppressed,” said Sami al-Saadi, when explaining to Human Rights Watch what took him to Afghanistan.”[66] He added that the Libyans who went also viewed their time in Afghanistan as a way to obtain military training that they could eventually use to overthrow Gaddafi.

Libyan Islamic Fighting Group

The date the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG) was founded is unclear. According to some senior members, the LIFG grew out of a secret group that was formed in Libya in the late 1980s out of frustration with Gaddafi’s rule and his crackdown on organized Islamist opposition.[67] Some scholars, however, assert that the group formed in Afghanistan in the 1990s.[68] “So many people think that we established our organization in Afghanistan and that it was due to the ideas in Afghanistan, but we started here in Libya in 1988,” said Mohammed al-Shoroeiya, who was the LIFG’s Deputy Head of the Military Council.[69]“We had one goal, getting rid of the Gaddafi regime.” In any case, the LIFG appears to have become a more organized and larger entity in Afghanistan during the 1990s.[70]

After the Soviets withdrew from Afghanistan in 1989, a struggle to remove the Soviet-backed proxy government of Mohammed Najibullah continued through the early 1990s. Infighting among many Afghan factions ensued and intensified, with many areas in Afghanistan, including Kabul, engulfed in civil war.[71] The fighting made it difficult for many Libyans to remain in Afghanistan. The LIFG began covertly sending operatives into Libya, staging operations against the government.[72] It also set up bases in Pakistan and Sudan, as well as in Europe and the Middle East. From 1995 until 1998, the LIFG waged a low-level insurgency, mainly in eastern Libya, intended to overthrow Gaddafi militarily. It staged three unsuccessful attempts to assassinate Gaddafi between 1995 and 1996.[73]

|

“The regime was like an upside down pyramid built upon the personality of Gaddafi. Get rid of Gaddafi and everything changes,” Shoroeiya said. “That was our goal.… We didn’t anticipate that other groups [in Afghanistan] would have ideas to fight against others in this world.” |

The LIFG did not formally announce its existence until Libyan authorities discovered it in June 1995, after a clash over the rescue of an LIFG member who was under armed guard in a hospital.[74] This clash forced the LIFG into the open and was the start of several serious battles between the LIFG and the Libyan government for the next three years. This included large-scale aerial bombardment of the LIFG’s strongholds in eastern Libya.[75] By 1998, the government succeeded in crushing the group’s Libyan operations, and many of its members fled. Some sought asylum in the United Kingdom and elsewhere in Europe, but a large number of them returned to Afghanistan, one of the only locations where, according to many of those interviewed for this report, Libyans who did not have proper papers or documentation were able to remain.[76] “At the time there was no other country that allowed us to be together and train,” said Muhammad Abu Farsan, an LIFG member who had fled Libya in 1990.[77] Many were also drawn to the Taliban’s concept of an Islamic state.[78] At the time, many others from the region, such as Morocco and Algeria, who sought to overthrow their governments for being insufficiently Islamic, also went to Afghanistan.[79] Al Qaeda tried to use these groups and their members to further its own aims but most of them reportedly resented these efforts.[80]

Some senior members of the LIFG said that al Qaeda tried to persuade the LIFG on several occasions in 2000 and 2001 to form an alliance with them, but that the LIFG refused.[81] At the time, the LIFG was the largest Arab armed group in Afghanistan besides al Qaeda.[82]

In meetings in Khandahar, Afghanistan, in April and May 2000, both Sami al-Saadi and Noman Benotman, senior LIFG members, said the LIFG demanded that bin Laden cease using Afghanistan as a base from which to launch operations.[83] After the September 11, 2001 attacks, most of the core leadership of the LIFG, with some exceptions, fled Afghanistan, sure they would be swept up in post-September 11 arrests and unwilling to stay behind and fight with the Taliban and al Qaeda.[84] Indeed, as is documented in this report, many senior LIFG members were arrested in 2003 and 2004. The biggest blow came in March 2004 when both Belhadj, head of the LIFG, and Sami al-Saadi, the LIFG’s religious leader, were taken into custody and sent back to Libya with direct US and UK participation.

Years later, there was speculation that two other longtime LIFG members—one of whom reportedly had been detained by US forces in Bagram, Afghanistan, but escaped, Abu Yahya al-Libi,[85] and another who remained behind in Afghanistan after the September 11 attacks, Abu Layth al-Libi[86]—had joined al Qaeda.[87]

In late autumn of 2007, these reports appeared to be confirmed when Abu Layth al-Libi announced that the LIFG had joined al Qaeda.[88] This assertion, however, was later rejected by core leaders of the LIFG, which posted statements on several websites saying it was unauthorized. The LIFG “had no link to the al Qaeda organisation in the past and has none now,” the statement read.[89]

In fact, by the time Abu Layth made the announcement, the core leadership of the LIFG, then imprisoned in Libya, had already begun reconciliation talks with the Gaddafi government.[90] The mediator for these talks was Saif al-Islam, one of Gaddafi’s sons.[91]Noman Benotman, a LIFG member based in the UK, was allowed to return to Libya for the talks.[92] Abu Layth al-Libi and Abu Yahya al-Libi reportedly opposed reconciliation.[93] In January 2008, Abu Layth was reportedly killed in a US air strike.[94]

Ultimately the LIFG leadership imprisoned in Libya did reconcile with the Libyan government. Part of that reconciliation involved the publishing of a book, over 400 pages long, called “Corrective Studies in Understanding Jihad Accountability and the Judgment of the People,” in which the LIFG renounced the use of violence to achieve political aims.[95] The book was authored by six of the LIFG’s most senior members: Belhadj, Saadi, Sharif, Abd al-Wahhab (the elder brother of Abu Yahya al-Libi), Mitfah al-Duwdi, and Mustafa Qanaifid. It ultimately resulted in the early release in March 2010 of three of the men interviewed for this report—Belhadj, Sharif and Saadi—along with hundreds of other prisoners.[96]

Clearly some prominent LIFG members did sympathize with and even joined al Qaeda, but the announced merger did not occur until years after the LIFG’s core leadership were detained, with US and UK help, and locked up in Libyan prisons. All of the former LIFG members interviewed for this report said that the LIFG never shared the ideology of al Qaeda or any of its goals. “It happened that we found ourselves in the same place at the same time as al Qaeda: in Afghanistan, where we sometimes fought next to them when it was to liberate the country, but we were never at their service,” said Belhadj, the head of the LIFG who would play a leading role in the resistance that overthrew Gaddafi in 2011. “There was no other place [besides Afghanistan] for us to go,” said Saadi, the LIFG’s religion and legal expert. He said that al Qaeda asked the LIFG to join them, as other jihadist groups had, but that the LIFG refused. “Our purpose, the object of our fight, was the Gaddafi regime and we did not want to open any conflicts up with Western governments or with anyone besides the Gaddafi regime,” he said.[97]

The US government took a different view. After September 11, 2001, Gaddafi condemned the attacks against the United States, said the US government had the right to retaliate, and urged Libyans to donate blood to victims. He later said that the United States and Libya had a common interest in fighting terrorism.[98] Shortly thereafter, on September 25, 2001, President George W. Bush signed an executive order freezing the assets of the LIFG in the United States.[99] One month later, senior administration officials went to Tripoli to meet with Musa Kusa, who handed over information on Libyans who he claimed were allied with al Qaeda, as well as the names of several Libyan militants living in the United Kingdom.[100] And in December 2004, after the United States and the United Kingdom had reconciled with Gaddafi and a number of LIFG leaders had been sent back to Libya, the US State Department placed the LIFG on its list of terrorist groups.[101] Later the State Department elevated the LIFG to an al Qaeda “affiliate.”[102]

Gaddafi’s Rapprochement with the West

Gaddafi’s willingness to provide intelligence about Islamist armed groups, and his agreement to give up Libya’s “weapons of mass destruction” program, appear to have been key to the thawing of relations between Libya and Western governments.[103] Some correspondence in the Tripoli Documents reflects this new relationship.[104] In September 2003, Gaddafi also agreed to pay compensation to family members of those killed in the bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland in 1988; in return, international sanctions against Libya would be lifted.[105] In February 2004 the United States opened a diplomatic mission in Tripoli and, in June 2006, the US State Department rescinded Libya’s designation as a state sponsor of terrorism.[106] The Tripoli Documents also show that at some point in March 2004, the CIA began to set up an office in Libya.[107]

On March 25, 2004, UK Prime Minister Tony Blair paid a visit to Libya, the first by a British prime minister since 1943. He and Gaddafi formally mended relations between the two countries and discussed their “common cause” in counterterrorism operations.[108] On the same day, Anglo-Dutch oil giant Shell announced it had signed a deal worth up to £550 million (approximately $1 billion US) for gas exploration rights off the Libyan coast.[109]

Gaddafi’s rapprochement with the West had profound effects on the LIFG. After the United States added the LIFG to its official list of foreign terrorist organizations, the United Kingdom followed suit in October 2005.[110] As one prominent LIFG member, Noman Benotman, said at the time, “Now anyone who is an enemy of Kadafi is also an enemy of the United States.”[111]

After the September 11 attacks and the US-led invasion of Afghanistan in October 2001, the Libyans who had been training with the LIFG in Afghanistan—as well as many other armed groups that had established a foothold in Afghanistan—broke apart and fled. Many of the Libyans initially went to Pakistan and then on to Asia, Africa, and elsewhere in the Middle East. Those who spoke to Human Rights Watch said that they constantly feared apprehension and that their worst fear was being captured and returned to Libya. Mustafa Jawda al-Mehdi said he begged his American captors not to send him back:

I informed them that I faced a real danger if they sent me back. I was wanted in Libya…. If I reached Gaddafi that was when the real ‘ceremony’ was going to begin. I was so clear. I said they will kill me, they will torture me…. It was the first time I cried actually, the first tears I wept were when they told me I was being handed over to the Libyans.

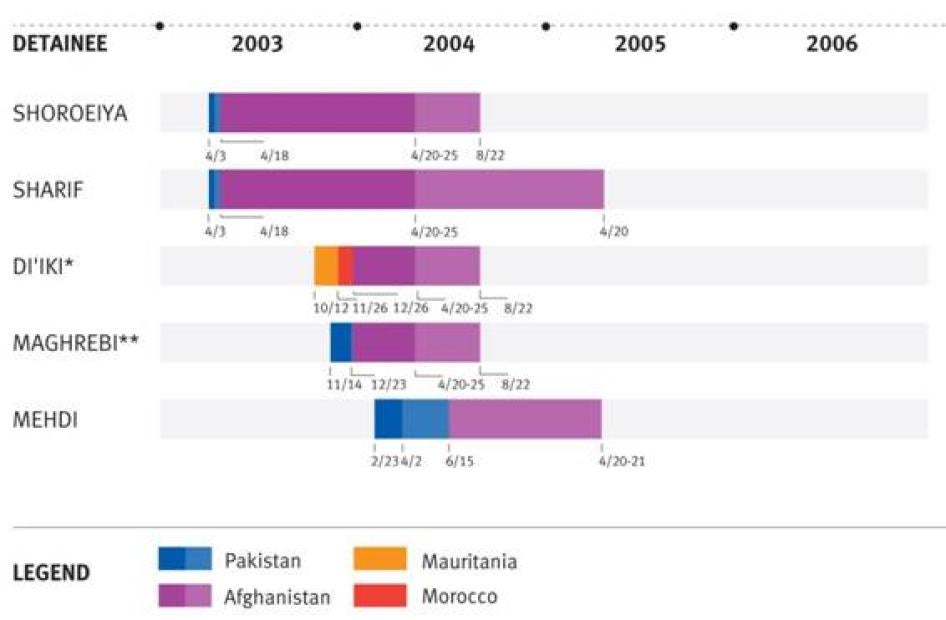

PLACES OF ARREST, DATES OF TRANSFER, AND TIME IN US SECRET DETENTION IN AFGHANISTAN OF FIVE LIBYANS HELD IN US CUSTODY

The dates in the table are approximations based on the accounts of the five Libyans as well as corroborating information from other detainees thought to be held in the same location. For example, the transfer between the different Afghan facilities is believed to have been around April 25, 2004, but that may not be the exact date for each detainee.

*) The dates for Di'iki are estimates. He said he was arrested on October 12, 2003, detained in the first location in Mauritania for about two to three weeks, and then in the second place for about two weeks. That would have occurred around November 12-19, 2003. He said he was then sent to Morocco, where he was held for about one month.

That took place around December 8-15, 2003. He said he was then transferred to Afghanistan in early January 2004; he thought it was around January 7, 2004. If that is correct, it would mean he was in detention either in Mauritania or Morocco for longer than he thinks, or he is mistaken about the date of transfer to Afghanistan. In either case, he said he was forcibly returned from a second facility in Afghanistan to Libya on August 22, 2004.

**)

The dates for the time Maghrebi was in the first and second location in Afghanistan

are estimates. He said that in the first location he was in his first cell for

about two months, then another cell for about 15 days and then a third cell for

another one and a half to two months. This would put him in the first cell

until around February 10, 2004, the second cell until March 10, 2004, and the

third cell until sometime between March 10 and April 25, 2004. Several other

detainees said they were transferred around April 25, 2004 to a second location

and Maghrebi said he was with about six other people during his transfer, so we

believe that he was moved to the second location on that same date. The April

25 date is consistent with his assertion that he was held in the second

facility for about four months and was returned to Libya on August 22, 2004

with Shoroeiya and Di'iki.

II. Detainee Accounts from Afghanistan and Morocco

This section focuses on six individual cases involving detentions in Afghanistan or Morocco and subsequent transfers to Libya. We have grouped them together because, of the 14 individuals interviewed by Human Rights Watch, these are the ones whose unlawful renditions to Libya were most clearly connected to the United States. They also are the ones who spent the longest period of time in US custody, and experienced the most serious abuse. Five of them reported being held in US-run prisons in Afghanistan for between eight months and two years before being transferred to Libya. Four of the five were detained in Pakistan before being transferred to Afghanistan and one was detained in Morocco before being sent to Afghanistan. A sixth individual, connected to the latter by a communication in the Tripoli Documents,[112] was also held in Morocco. Unlike the others, he was not sent to Afghanistan but rather straight to Libya from Morocco.

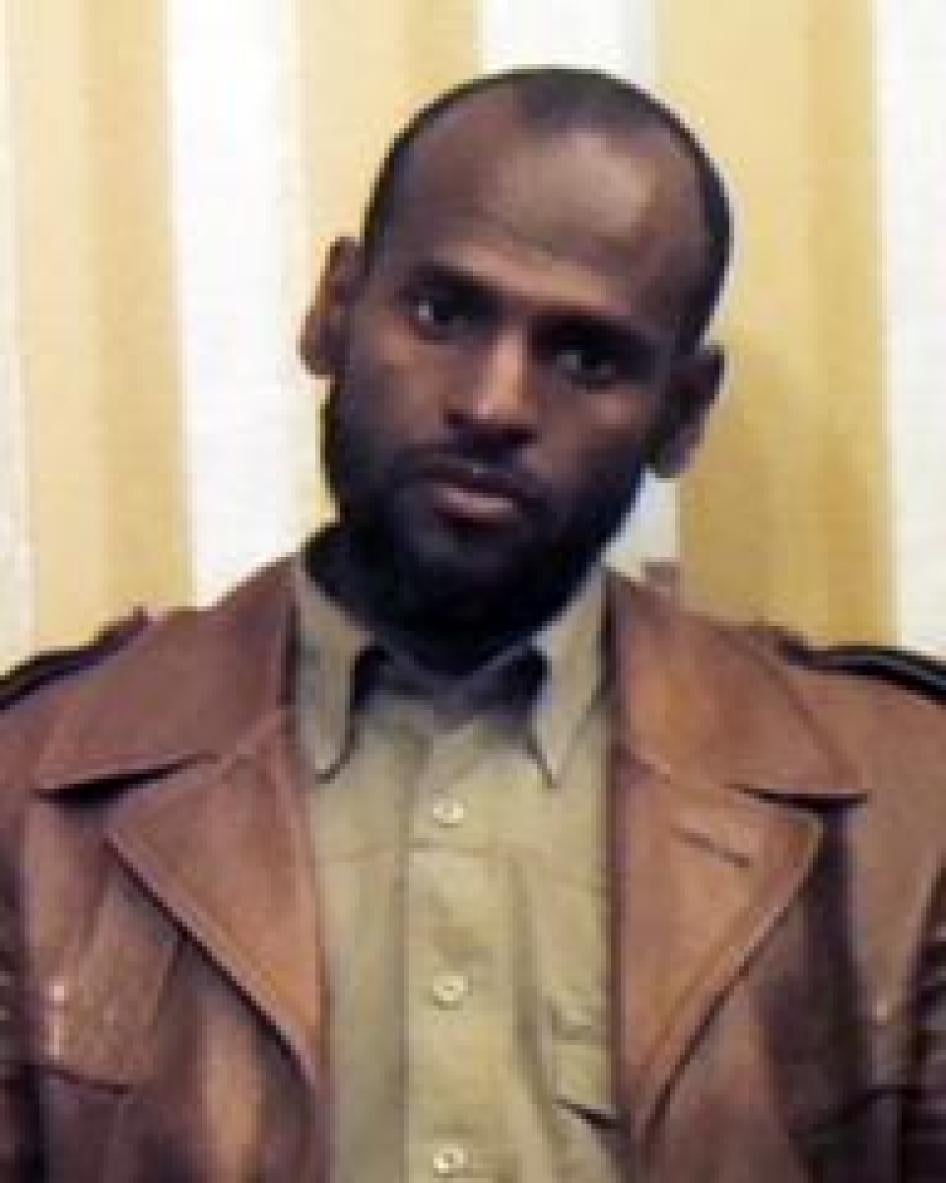

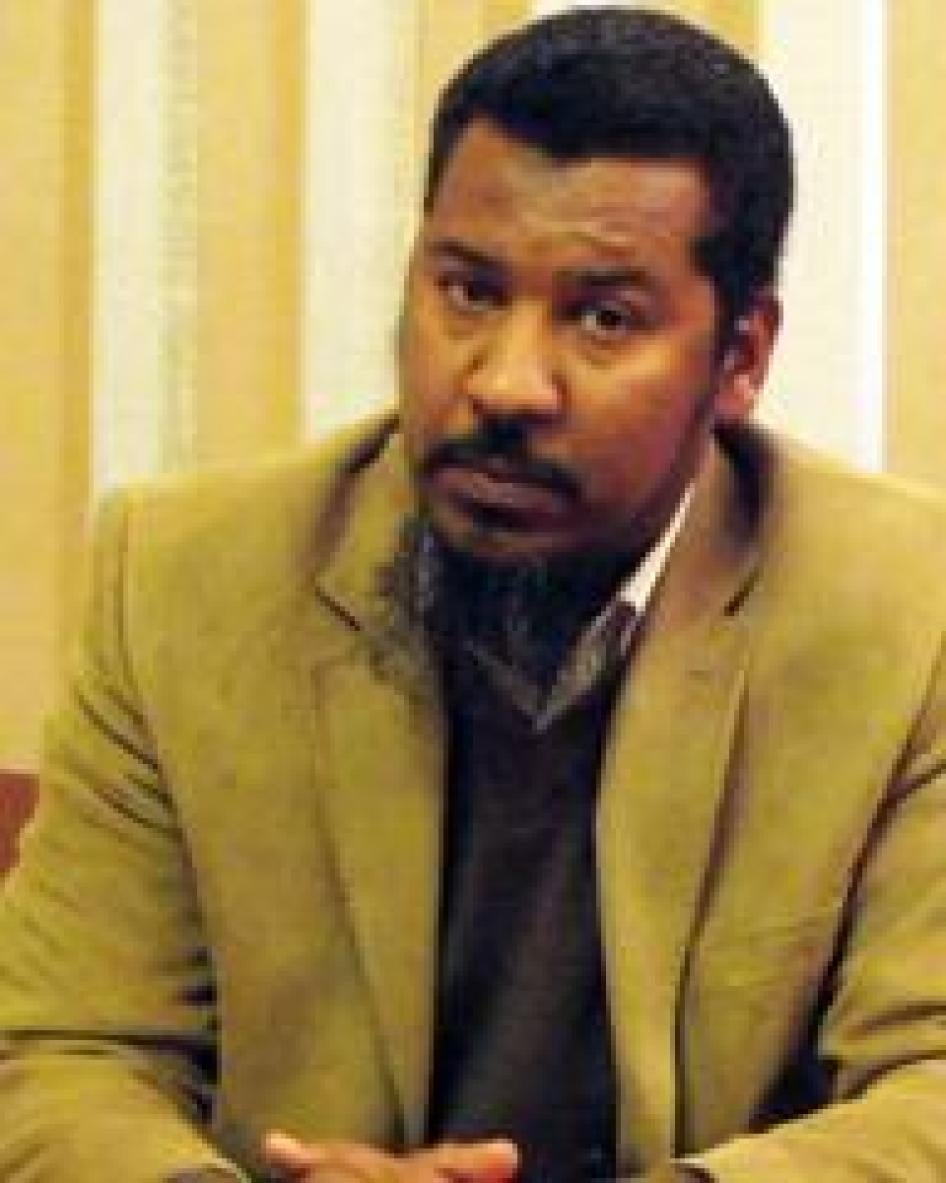

Mohammed Ahmed Mohammed al-Shoroeiya and Khalid al-Sharif

Mohammed al-Shoroeiya. © 2012 Human Rights Watch Mohammed al-Shoroeiya (Shoroeiya) [113] and Khalid al-Sharif (Sharif) [114] are two former LIFG members who said they left Libya in 1991 and 1988 respectively. Pakistani authorities arrested the two together in Peshawar, Pakistan, in April 2003. Pakistani and US personnel interrogated and then transferred them to US-run detention facilities in Afghanistan. While they were physically abused during interrogations in Pakistan, they said the mistreatment in Afghanistan was much worse. Shoroeiya and Sharif said that once in Afghanistan, they were detained and interrogated—for more than a year in Shoroeiya’s case, and for two years in Sharif’s case—by US personnel. This included being chained to walls naked—sometimes while diapered—in pitch black, windowless cells, for weeks or months at a time; being restrained in painful stress positions for long periods of time, being forced into cramped spaces; being beaten and slammed into walls; being kept inside for nearly five months without the ability to bathe; being denied food; being denied sleep by continuous, deafeningly loud Western music; and being subjected to different forms of water torture including, in Shoroeiya’s case, waterboarding.

Khalid al-Sharif © 2012 Human Rights Watch Following their US detention, they were rendered to Libya, where they were again abused in detention. Both were eventually summarily tried and convicted, with Shoroeiya sentenced to life in prison and Sharif sentenced to death by firing squad. Sharif was released on March 23, 2010, after nearly five years in prison, as part of a negotiated agreement involving other imprisoned LIFG leaders and hundreds of other prisoners. Shoroeiya was released on February 16, 2011, when the uprisings against Gaddafi began. Human Rights Watch interviewed Shoroeiya and Sharif separately on two different days in March 2012 in Tripoli and then again by phone from New York in May 2012. Human Rights Watch also spoke to Shoroeiya in Abu Salim Prison in Tripoli in April 2009. The men have been in contact with one another since their release from Libyan custody. |

Departure from Libya

Sharif was born in 1965 in Tripoli and left Libya in April 1988 when he was 23 because “the situation was getting worse,” he said. “Our religious people were subjected to abuse. We had no ability to express ourselves, no choices. Even attending the mosque was a crime.” He had been studying pharmacology at college in Tripoli. He and some others started a secret group to try and overthrow the government, but one of his friends was executed. After that, he and others in the group decided to leave Libya, out of fear, but also to organize and train. Sharif left Libya for Saudi Arabia, then Pakistan and Afghanistan. He became very active in the LIFG, eventually becoming the deputy head of the organization. In 1995 he moved to Sudan, where he said the LIFG started to take some action against the Libyan government. He said he was forced to leave Sudan in 1996 and went to Turkey, then back to Pakistan, where he lived until 2002. After the September 11 attacks, he and his family went to Iran, but in Iran he was detained and forced to return to Pakistan. He arrived back in Pakistan in early 2003.[115]

Shoroeiya is from Misrata in eastern Libya. He was born on March 22, 1969 and left Libya in 1991. He was in the middle of his studies in science but left, he said, because of threats against committed Muslims, especially those who were students. He first went to Algeria and then to join other members of the LIFG in Pakistan and Afghanistan. In 1995 he moved to Sudan, where the LIFG was based and planning actions against the Gaddafi government. The actions drew new recruits, he said, but the Sudanese government would not allow the LIFG to train the recruits, so they moved back to Afghanistan. He left Afghanistan for Turkey in 1999 and married an Algerian woman, Fawziya, while there. They returned to Afghanistan in 2000 and were in Kabul during the September 11 attacks, though they quickly moved to Karachi, Pakistan. He said that for him this was a very frightening time and that the LIFG did not agree with bin Laden’s actions. He told Human Rights Watch, “[f]or us there were huge differences between us [al Qaeda and the LIFG], but we knew that they were going to see us all as one group together. At that time, the US lost its ability to distinguish between people.” He began to feel that Karachi was not safe, so he moved to Peshawar. He wanted to try and get to Iran as other LIFG members had done, but his wife was pregnant so his ability to travel was limited.[116]

Arrest and Detention

Shoroeiya and Sharif were both arrested in Peshawar on April 3, 2003. Shoroeiya was living with his wife, Fawziya, and their 9-month-old daughter, Aisha. Sharif was staying on the second floor of Shoroeiya’s home. [117] Around noon, the house was suddenly surrounded by what seemed to both of them like scores of police, some in vans with black windows. [118] Sharif tried to escape by jumping out the window and climbing over a wall next door. In the process he broke his foot. [119] Shoroeiya was also injured during the arrest, breaking his leg. [120] Shoroeiya was detained for about ten days in a place he referred to as “Khyber.” Sharif said he was detained for about seven days in a building called the “army stadium” near a fairground. Both places were in Peshawar, but it is not clear if these were the same locations.

Both men were then moved to a facility in Islamabad, Pakistan’s capital. Sharif and Shoroeiya said they were in cells next to each other while in Islamabad.[121] Sharif said he knew he was in Islamabad because he had been living in Pakistan by then for many years and knew Islamabad well. He was not blindfolded, and on the second day of his arrival he was brought to a hospital in Islamabad to treat his broken foot.[122]

During this period both say they were interrogated by Pakistani and US personnel. Shoroeiya said there were two teams of Americans, one in Peshawar and one in Islamabad, all men. Sometimes he was hooded during interrogations, but not always. The Pakistanis at times beat him during these interrogations, in some cases after the Americans ordered them to do so. Whenever he was beaten, however, the Americans would leave the room.

Sharif provided additional details of his arrest and detention in Pakistan, including his reasons for believing his captors and interrogators were Pakistani and American. After the arrest, he was immediately blindfolded and hooded. The interrogation began on the same day as the arrest, right after he was taken to the detention facility in Peshawar. He said he believed it was a Pakistani Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) facility because during his detention the guards were wearing Pakistani military uniforms and the officers, who were in civilian clothes, had a file on him.

During his interrogation, Sharif’s blindfold and hood were taken off. He said that because of his broken foot he could not walk, and he would be carried into the interrogation room, an American on one side, a Pakistani on the other. He said the American, who spoke Arabic poorly, would ask the questions and when Sharif did not provide an answer they seemed to think was adequate, the Pakistani would step on his broken and untreated foot. The Pakistani officer would also beat Sharif and lash him with a whip all over his body.

Sharif said that while he was detained in Peshawar, a Pakistani officer who spoke to him in Pashto beat him. He spread Sharif’s legs apart and kicked him in his groin. The officer also hit Sharif on his head with a whip so violently that he nearly lost consciousness. While the Pakistani was beating him, a different American sat on a chair right in front of him.

On another occasion at the Peshawar facility, the first American asked him in his poor Arabic for help finding Abu Faraj al-Libi (now detained in Guantanamo). He offered millions of dollars as a reward. This questioning session did not involve any physical abuse. Sharif said that during the final few days of his detention he was not interrogated. He was then moved to Islamabad.

Both Shoroeiya and Sharif said they were interrogated by Pakistanis and Americans at the facility in Islamabad. Sharif said that a few hours after he arrived he was told he was going to be transferred to a place where he would be “better able to speak.” He said the comment felt like a threat.

CIA Rendition Transportation ProceduresThe accounts of many former detainees subjected to CIA renditions between the years 2002-2005 show standardized treatment during transfer. In most cases, the detainee was stripped of his clothes, photographed naked, and administered a body cavity search (rectal examination). Some detainees described the insertion of a suppository at that time. The detainee was then dressed in a diaper. His ears were plugged, headphones were placed on his head, he was blindfolded or provided black goggles, and his head was wrapped with bandages and adhesive tape. The detainee’s arms and legs were shackled and he was put into the transportation vehicle.[123] (Hereinafter “CIA rendition transportation procedures”). The UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners allow the use of instruments of restraint when prisoners are being transferred. However, some instruments may never be used, such as chains or irons, and others, including handcuffs and straitjackets, shall never be applied as a punishment.[124] The transfer of a prisoner also does not permit treatment that would amount to torture or cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment.[125] While the US was entitled to use constraints as necessary for transporting detainees by plane, some of these methods, particularly when used in conjunction with others, appear intended to punish the detainee or were, at a minimum, degrading. |

After one week in Islamabad, both said they were stripped, blindfolded, handcuffed, and their legs shackled.[126] Their captors also put ear plugs in their ears and hoods over their heads.[127] Shoroeiya said that they did some additional things to him, but they were things he could not describe to a female Human Rights Watch researcher.[128] Before being stripped, Sharif mentioned that they examined his mouth, ears, and eyes. The two said they were then taken on a vehicle, and then boarded onto a plane.

They flew for about half an hour to a location they believe was inside Afghanistan. Sharif said that after they disembarked, the detainees were thrown into the back of trucks. Sharif believed he was brought to a hangar-type facility near Kabul airport.[129] Shoroeiya also said he was in a hangar-type facility and believed it was in or near Bagram Air Base, which is about 40 kilometers north of Kabul airport.[130] Neither was sure of their locations but both said they knew they were in Afghanistan because of the time it took to fly to the location and the fact that the guards were dressed in traditional Afghan clothing when they first arrived, occasionally spoke to them in Dari (the local Afghan language), and served them Afghan food. Both knew they were detained in the same location because although they never saw each other, occasionally they were able to talk to one another over the loud music that played constantly.[131]

Both were detained in this first location in Afghanistan for about a year. Shoroeiya gave the exact dates, stating that he was there from April 18, 2003 to April 25, 2004.[132] Sharif said he was there for about a year from the time he arrived from Islamabad, though he did not know the exact date of his arrival, until sometime between April 20 and April 25, 2004. They were then moved to a second facility that they both also believed was in Afghanistan and run by Americans. Shoroeiya stayed there for about four months and Sharif for approximately one year.

The following is a description of the first facility in Afghanistan, where they allege the worst abuse occurred.

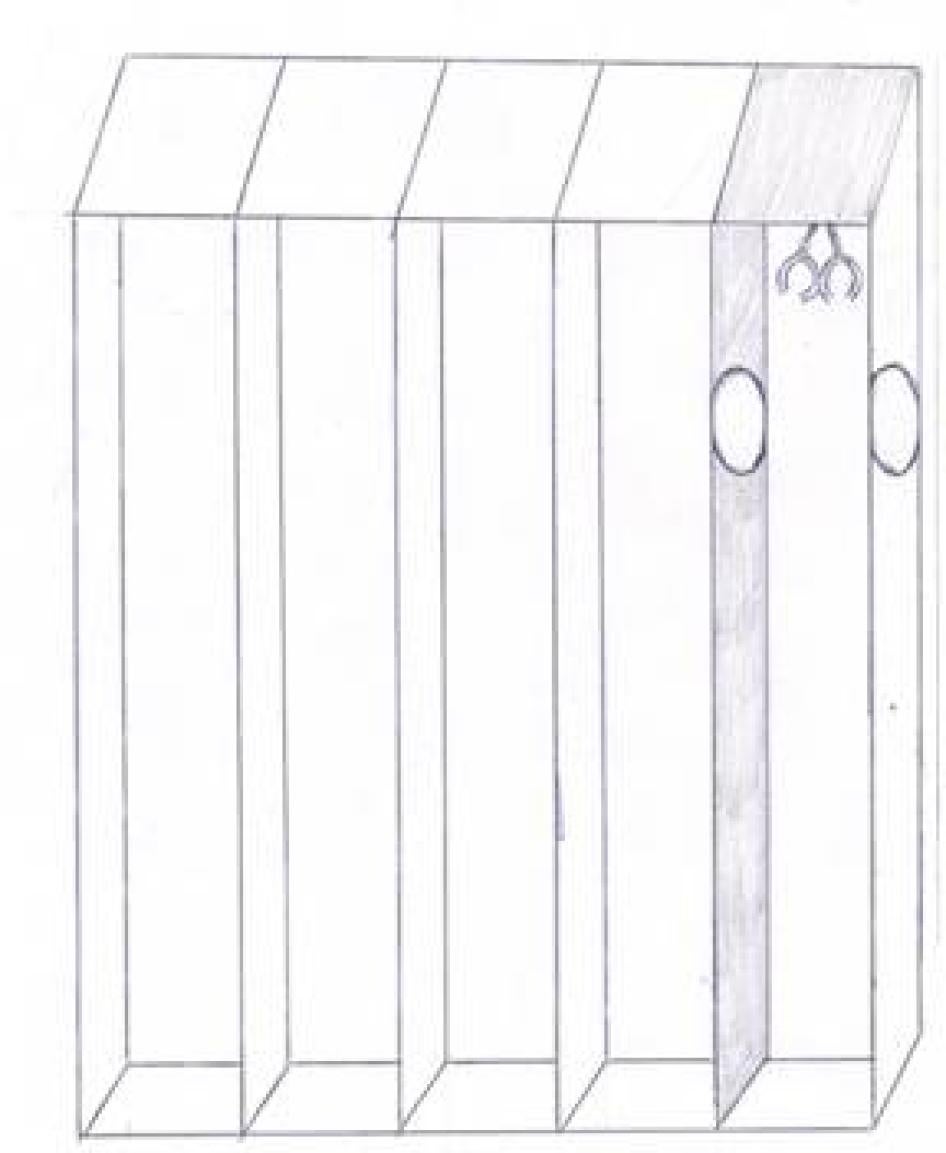

Afghanistan I

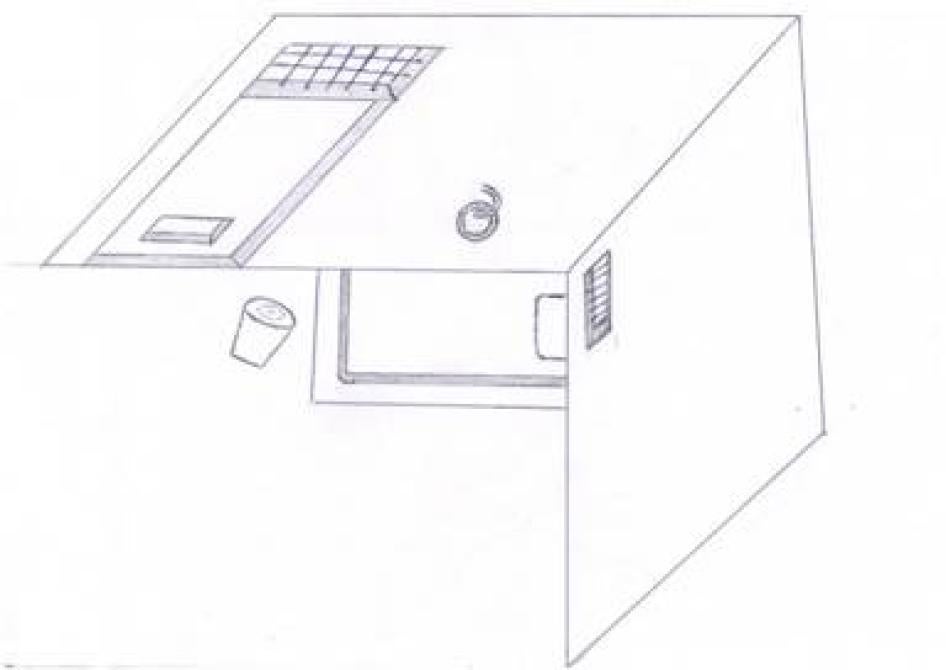

Shoroeiya had a thin mat in his cell, while Sharif said he had a carpet, perhaps a mat, in his cell. Both had a bucket in their cell they were to use as a toilet. The men said that chemicals were in the bucket that, when mixed with their urine and excrement, gave off a terrible stench. Shoroeiya drew a layout of the facility where he was detained and his cell for Human Rights Watch (see below). He was in cell one, which he said was slightly bigger than the rest of the cells. According to Shoroeiya, there were about 15 cells for prisoners in this same location.[134]

A sketch by Mohammed Shoroeiya depicts his cell. © 2012 Mohammed Shoroeiya

Though neither Sharif nor Shoroeiya saw other prisoners, occasionally they were able to talk when there was a break in the music or the volume lessened. Sharif said these periods were usually very short so he and the other prisoners would immediately take the opportunity to shout to each other. Once, the break lasted an entire day: “One day there was a day-long failure of the music so it was a great opportunity for us to talk,” said Sharif.[135] They would try and remember names and details of each other’s cases so that if anyone got released, they could communicate this information to their families and the outside world.

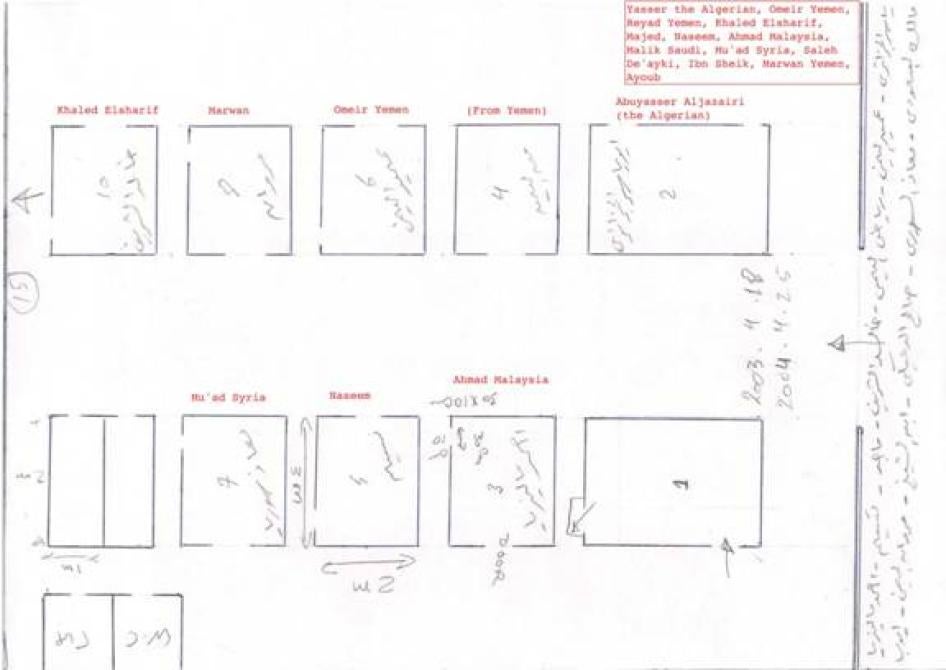

From this type of communication, Shoroeiya was able to provide a list of those who he believed were detained within this facility. Some he just knew by nickname or first name and where they were from.[136] They include:[137]

Abu Yasser al Jazairi, from Algeria;[138] Omeir, from Yemen;[139] Reyad, from Yemen; Khalid Sharif; Majed;[140] Nassem; Ahmad, from Malaysia; Malik, from Saudi Arabia; Mu’ad, from Syria; Saleh De’ayki;[141] Ibn Sheikh;[142] Marwan, from Yemen; and Ayoub.[143]

From the sound of their voices and information he obtained from other prisoners, Shoroeiya drew where he believed each individual was detained within the facility.[144]

Mohammed Shoroeiya drew this rough depiction of the facility in Afghanistan where he was held for nearly a year. The typed, red writing are English translations of the Arabic names Shoroeiya drew in pencil on this sketch. © 2012 Mohammed Shoroeiya.

Sharif also said that he was either able to speak to, or heard the voices of, other prisoners during his detention in this facility:[145]

Abu Nasseem al-Tunisi; Marwan al-Yemeni; Assad Allah—the son of Sheikh Ibn Omar Abdul Rahman—from Libya; Shoroeiya; Majed Adnan;[146] Salah al Di’iki;[147] someone from Malaysia whose name he could not remember; someone from Baluchistan; Abu Ammar, but he was not sure of his name; and Ibn Sheikh al-Libi.[148]

Sharif also said he learned the names of some prisoners he was told were there before he arrived, who he believed were transferred to Guantanamo.[149] They were:

Abu al-Faraj al Libi;[150] Nuqman from Zliten; Abu Ahmad; Abu Omar al Baidawi, from al Bayda; and Munir al Khomsi, from Khoms.

Sharif said his cell was about 4 x 3 meters. It had a steel door in the middle and a window with steel bars over the door. On what he described as the backside of the cell there was also another small window.[151] Shoroeiya did not provide measurements for his cell, but he said it was slightly bigger, and drew it as slightly bigger than Sharif’s cell. Shoroeiya’s cell also had a door with a window at the top with bars on it and a slot in the middle of the door that the guards used to pass food through and check on him occasionally. There was a small window, about 10 x 30 centimeters that had bars on it too, was about 13 centimeters from the ground, and provided some ventilation.[152] He added that it also “was a very good entrance for rats.”[153]

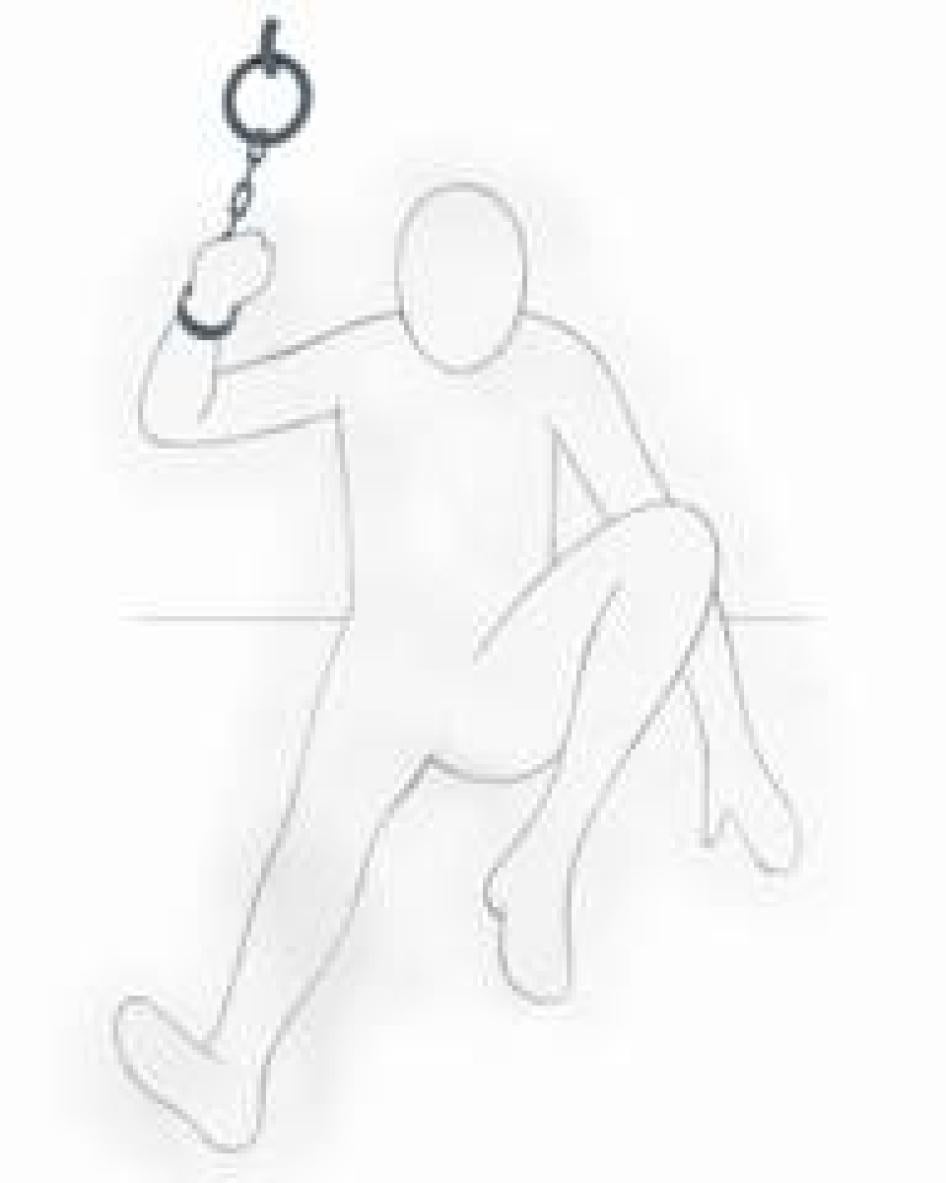

In their cells, during the first three to four months of interrogation, which both called the first “period” of interrogation, each was chained to two iron rings that came out of the wall. Shoroeiya said the rings were about one meter above the ground. They described being chained to these rings, sometimes by one arm so that the other arm and both legs were free (Position 1); sometimes by both arms with both legs free or at times chained together (Position 2); and sometimes both legs and arms were all shackled to the ring together (Position 3;). Later, after about a four-month period of intense interrogation and abuse, Shoroeiya said he was allowed to be unchained in his cell and to walk freely around it.

Position 1[154] |

Position 2 |

Position 3 |

“I would try to take that time to use the bucket for a toilet I had in my room, but could not do so all the time, so I usually would just pass urine through my clothes.”

Sharif said that at one point he spent two weeks in position 3, with both his arms and legs shackled to the iron ring. During this time, they would unchain him only once a day for half an hour to eat the one meal they gave him. Afterwards they would chain his hands and feet back up to the wall: “I would try to take that time to use the bucket for a toilet I had in my room, but could not do so all the time, so I usually would just pass urine through my clothes.”[155]

Shoroeiya said he was in either position 1, 2, or 3 in his cell for four months continuously after he first arrived. After four months he was not shackled or handcuffed but was able to move freely around his cell until he was moved to the second place of his detention in Afghanistan on April 25, 2004. Both men said they were not able to shower or bathe during the first several months of their detention.

“For the first three months we were not able to have any showers. We could not wash our bodies.”[156] Shoroeiya said of that same time period, “That whole time we didn’t even get a drop of water over our body. We couldn’t cut our hair or even the nails of our fingers. We looked horrible. We looked like monsters.”[157] After this first period, they were allowed to shower for 10 to 15 minutes weekly. They were also allowed some exposure to the sun, for a short period of time, mostly once a week for the whole year.[158]

Sharif said sometimes his captors sent him to a cell where his hands were suspended above his head for significant periods of time. One time this period lasted three days. During this time he was provided limited sustenance:

They only gave me water once, at night. They gave me a milkshake and a small cup of milk with cocoa. That was all I had for three days. They banned me from going to the restroom for those three days. I had to pass urine and go to the bathroom standing up. I wasn’t wearing clothes. At night, they gave me some water to drink but poured the rest of it over my body. I was trying to move to create some warmth in my body. Because of the lack of sleep for three days, I went hysterical. I thought I was going crazy. Everything was spinning around me and it was totally dark.[159]

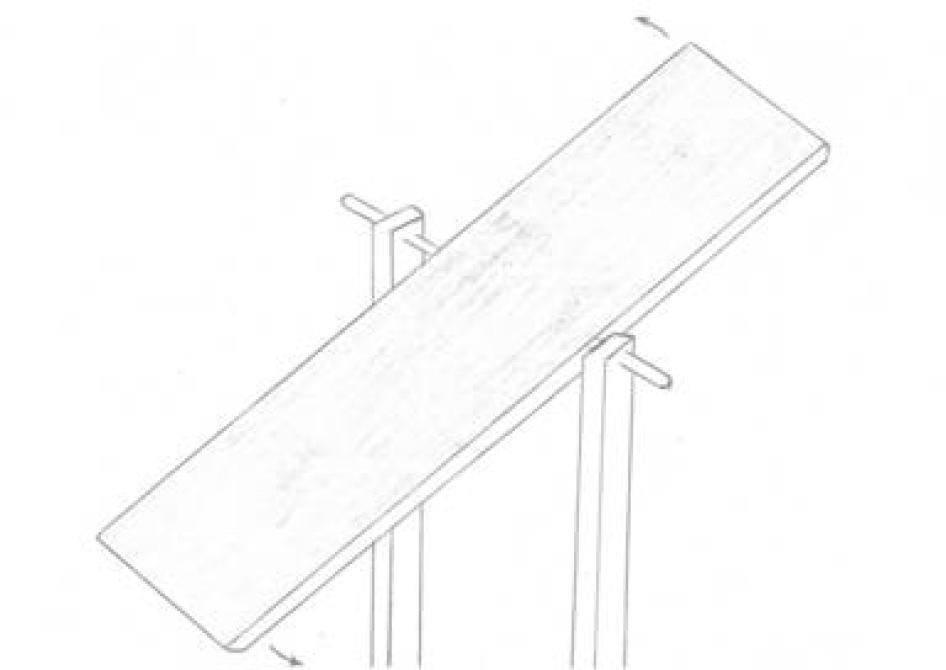

A sketch by Mohammed Shoroeiya depicts a narrow windowless box where he said he was held naked for one and a half days. © 2012 Mohammed Shoroeiya

On another occasion he said he was in a room that was about 1.5 x 1.5 meters.[160] Again his hands were suspended above his head from an iron bar that went between the walls. His feet could touch the ground but he also could only stand on one foot because his broken foot was still not healed. There were no windows and it was dark, but there were small, “yellow” holes. He could see a small red light that made him think there may have been a camera in there. They left him there for several hours.

Shoroeiya said that when he first arrived, he was also put in a place with his hands suspended above his head in a similar position, though he describes the conditions differently.

He said it was a very narrow room or box, about 0.5 meters wide and just high enough for him to stand with his hands above his head. He is 1.75 meters tall. His hands were handcuffed to a bar that went across the top of the room. There were other rooms next to his. His feet could touch the floor but he could only stand on one leg because the other leg was still broken and very swollen. Speakers built into the walls of the box were on each side of his head just centimeters to his ears blasting loud Western music. There were no windows. It was dark but there was just enough light to see what he said looked like blood stains on the walls. He was held there, with his hands suspended above his head, for one and a half days, with no food, naked, with the music blasting loudly the entire time.

“I found a woman there who was screaming and beat on the table. She literally told me, ‘Now you are under the custody of the United States of America. In this place there will be no human rights. Since September 11, we have forgotten about something called human rights. If you think you are going to stay here in a very good room and get your newspaper daily, you are wrong.’” |

Shoroeiya and Sharif both alleged this facility was run by Americans. With one exception, however, they said the Americans were not wearing official uniforms.[161] Shoroeiya said all of the Americans were dressed in black with caps on their heads and sometimes, when they carried out severe physical abuse, they wore masks. They were able to see some of this, despite the darkness, because guards and interrogators would come to them with lights on their foreheads and flashlights in their hands.

Afghan guards brought them food and maintained the facility, but mostly the Americans ran it. Shoroeiya said he knew the guards were Afghan because he spoke Dari and Pashto, and some of them spoke to him in these languages when he first arrived and occasionally afterwards. After some time, however, the guards stopped all interactions entirely. Shoroeiya said the guards wore traditional Afghan clothes in the beginning but then later began also wearing black clothes with military boots and facemasks similar to the attire of the Americans. Sharif said that when he spoke Pashto or Dari, the guards never spoke back but would sometimes give indications that they understood what he was saying. He also said their dress was “mixed,” with some in Afghan clothes and some all in black with black facemasks.[162]

When asked how they knew they were in US custody, they each said it was made very clear.

Sharif said that after he arrived at the facility:

I was approached by a tall, thin officer from the army [he was in uniform] who told me he was American. He was bald, but not naturally—his head was shaved. He had a lamp with a light on his head and was with a translator. And the room was totally dark—the only light in there was the light on his head. He started threatening me. He said, ‘Now we can kill you and no one will know. We want to hear about your last plan to strike America. All of what you said in Peshawar, we are not interested in that. We want new things now.[163]

Later this army officer would suddenly be very nice to Sharif, asking if his leg was hurting and promising to get him some medical attention for it.

Shoroeiya said that within the complex, there were several types of rooms. One was a group of rooms where he was interrogated. Another set of rooms were freezing cold and were used to submerge the prisoners in icy water while lying on plastic sheeting on the ground. A third set of rooms he called the “torture rooms,” where they used specific instruments. One of these instruments was a wood plank that they used to abuse him with water.

Although he did not refer to the abuse he received as waterboarding, the abuse he described fit that description.[164]

The Interrogators

Shoroeiya said the interrogators, all of whom he believed were American, came to him in three waves.[165] The first group would do a sort of soft interrogation, just asking questions. They were wearing what Shoroeiya described as “special forces” black uniforms with black caps on but no masks. Then the second group would come in. They were also wearing the same type of black uniforms with caps on, but unlike the first group, had what appeared to be some sort of bodyguards with them. “They were tougher,” he said. They had “some sort of specialists in this group who were very rough with us and who did the beatings,” he said. “The third group was the toughest.” They also wore the same black uniforms, but their faces were masked. They were the ones that used what he called “torture instruments:” the waterboard, the small box, and a tall, thin box. Sharif said the interrogators were assisted by interpreters who, based on their accents, he believed to be from different Arab countries, possibly including Lebanon, Egypt, Algeria, and Syria.[166] Sharif also mentioned that at times he had been interrogated by women while he was naked. It was not clear if this occurred in one or both of the places in Afghanistan where he was detained.[167]

Waterboarding

Shoroeiya said the board was made of wood and could turn around 360 degrees (see above).[168] Sometimes they would strap him onto the board and spin him around while wearing a hood that covered his nose and mouth. This would completely disorient him. While he was strapped to the board with his head lower than his feet, they would pour buckets of extremely cold water over his nose and mouth to the point that he felt he was going to suffocate. After the hood was put over his face, he said, “then there is the water pouring…. They start to pour water to the point where you feel like you are suffocating.”[169] When asked how many times this was done to him, he said “a lot …a lot … it happened many times …. They pour buckets of water all over you.”[170]

A sketch by Mohammed Shoroeiya depicts a wooden board to which he was strapped and on which his interrogators put him when he underwent abuse with water. © 2012 Mohammed Shoroeiya