Map: The West Bank and Gaza Strip

Summary

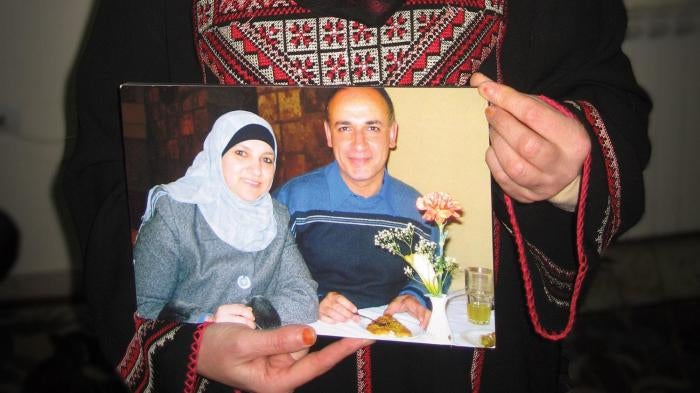

Muhammad N. was born in Gaza, where his parents and extended family live. But for more than 30 years the 66-year-old was able to visit the coastal strip—which Israel occupied in the 1967 Middle East war—for only three months at a time, and was not able to gain residency until four years ago.

Muhammad’s effective exclusion from his birthplace was rooted in a population census of Palestinians that Israel conducted in September 1967, shortly after capturing the Gaza Strip from Egypt and the West Bank from Jordan. The census counted the 954,898 Palestinians physically present in the West Bank and Gaza at the time, but did not include at least 270,000 Palestinians who were absent, either because they had fled during the conflict or were abroad for study, work, or other reasons.

At the time Israel conducted the census in Gaza, Muhammad was attending university in Cairo. “My father told me that when the [Israeli] soldiers came, he said that I was studying in Egypt … the soldier said, ‘So forget about him, he’s not here.’”

Israel subsequently recorded the names and demographic data gleaned from the 1967 census in a newly created registry of the Palestinian population. It refused to recognize the right of most of the absent individuals whom it did not register—including all men then aged 16 to 60—to return to their homes in the occupied territory.

From that time, Muhammad could only gain an entry permit for a maximum of three months. He eventually found work as an accountant in Abu Dhabi, married, and had a family. He applied for residency in the occupied Palestinian territory in 2000, but Israel stopped processing applications later that year, amid an escalation in Israeli-Palestinian violence. Israeli authorities eventually entered him, his daughter, and one of his sons in the population registry in 2007, but not his wife and another son. “It made no sense,” he said.

Since 1967, the population registry has been central to Israel’s administrative efforts to control the demographic composition of the occupied Palestinian territory, where Palestinians want to establish a state.[1] Israel has used Palestinians’ residency status as a tool to control their ability to reside in, move within, and travel abroad from the West Bank, as well as to travel from Gaza to Israel and the West Bank. A 2005 survey conducted on behalf of B’Tselem, an Israeli rights group, estimated that 17.2 percent of the Palestinians registered in the West Bank and Gaza, around 640,000 people, had a parent, child, sibling, or spouse whom Israeli military authorities had not registered as a resident.[2]

This report documents Israel’s exclusion of Palestinians from the population registry, and the restrictions it imposes on Palestinians who are registered. It finds that the Israeli measures vastly exceed what could be justified under international law as needed to address legitimate security concerns, and have dire consequences for Palestinians’ ability to enjoy such basic rights as the right to family life and access to health care and education facilities.[3]

Today, Palestinians must be included in the population registry to get identification cards and passports. In the West Bank, Palestinians need identification cards to travel internally, including to schools, jobs, hospitals, and to visit family, because Israeli security forces manning checkpoints demand to see such cards before allowing passage.[4] Israeli border officials, who control all entry and exit to the West Bank, also require Palestinians seeking to travel abroad to present an identification card or passport.

Since the outbreak of the second Palestinian intifada, or uprising, in September 2000, Israel has denied entry to the Palestinian territory to non-registered Palestinians and to non-registered spouses and other family members of Palestinian residents; for example, the number of entry permits to the West Bank and Gaza dropped from around 64,000 in 1999 to 192 in the 10 months after November 2000.[5]Israel has also effectively frozen the ability of most Palestinians who are registered as Gaza residents to move to, or even temporarily visit the West Bank, where many have relatives, own property, have business ties, or want to attend university.[6] Palestinians registered as Gaza residents who are already living in the West Bank face problems because Israel does not recognize their right to live there; unless they have special permits, it classifies them as criminal “infiltrators.”

Israeli authorities have sought to explain and justify these policies by referring to “the breakdown that occurred in the relationship between Israel and the Palestinian Authority” after “the outbreak of hostilities in September 2000.”[7] During the intifada, attacks by Palestinian armed groups killed hundreds of Israeli civilians. However, since 2000 Israel has continued to coordinate with the Palestinian Authority (PA), for example, by registering the births of children to registered Palestinian parents. Further, the Israeli rights group B’Tselem found that after September 2000, Israeli authorities frequently rejected Palestinians’ applications for residency without specifying any security threat.

Israeli authorities have argued that both these blanket restrictions on adding Palestinians to the population registry, and the partial, limited easing of those restrictions are political issues related to Israel’s relations with the Palestinian Authority, indicating that Israel views control over the population registry as a bargaining chip in negotiations. Israel’s control over the population registry has also significantly lowered the registered Palestinian population in the West Bank and Gaza, probably by hundreds of thousands of people.[8] Given that Israel has continuously increased the number of settlers in the West Bank, its reduction in the Palestinian population there, as Israeli rights groups have noted, is consistent with a policy based on “improper demographic objectives.”[9]

While security concerns could legally justify some restrictions on Palestinians’ rights, under international law such restrictions must be necessary and narrowly tailored to address specific threats. In contrast, in residency-related cases where Israeli military and judicial authorities have cited security concerns, they have often done so to justify restrictions that are so broad and general as to be arbitrary. For instance, Israel’s high court upheld the military’s blanket ban on all registered Gaza residents studying in West Bank universities because “it is not unreasonable to assume” that replacing the ban with a system of individually-screening applicants “will likely lead to an increase in terrorist activity.”[10] Such an approach, of allowing a complete ban on a basic right (education) on only the vaguest grounds of security, without individual determinations, violates human rights law.

Israel also claims that its human rights obligations, such as respecting the right to family life, do not extend to Palestinian territory, where it says international humanitarian law (the laws of war) applies exclusively. Therefore, Israel argues, it bears no responsibility under human rights law for harms inflicted on Palestinians by its policies relating to the population registry—even as it insists on maintaining its control over the registry.

Israel’s arguments have been repeatedly rejected by numerous legal authorities, including the International Court of Justice, which have confirmed that human rights law applies at the same time as international humanitarian law, including during military occupations. Israel is obliged to respect Palestinians’ human rights to freedom of movement, including the rights to move freely within and to leave and return to the West Bank and Gaza; the right to family unity; and other rights, including access to education.

Denial of Residency and Right to a Family Life

Even before the outbreak of Israeli-Palestinian violence in September 2000—in addition to the Palestinians it excluded from the population registry in 1967—Israel had for years denied or failed to process tens of thousands of applications for residency from the relatives, children, or spouses of registered Palestinians, on the basis of changing, arbitrary criteria.

After 1967, for instance, Israel granted residency to children under 16 who were born in the West Bank and Gaza, or who were born abroad if one parent was a registered resident. In 1987, with the outbreak of the first Palestinian intifada, the military ordered that children under 16 who were born in the occupied territory could only be registered if their mother was a resident, and that children born abroad could not be registered after the age of five, regardless of either parent’s residency status. As Israeli rights groups pointed out, in some Palestinian families, Israel thus considered that the older children were residents of the occupied territory but that their younger siblings born after 1987 were living there illegally. In 1995, Israel changed its policy and began to register Palestinian children who were born abroad to a registered parent, if the child was physically present in the West Bank or Gaza. However, in 2000 Israel stopped granting entry to all unregistered Palestinians more than five years old. In 2006 Israel began to grant entry permits to Palestinian children for the purpose allowing them to apply for registration, but it has refused to register children who turned 16 during the period from 2000 to 2006, when Israeli policies had made their entry and registration impossible.

Between 1967 and 1994, Israel also permanently cancelled the residency status of 130,000 registered Palestinian residents of the West Bank, in many cases on the basis that they had remained outside the West Bank for too long (in most cases, more than three years). Human Rights Watch interviewed Palestinians who said Israel cancelled their residency due to their failure to renew “exit permits” but who do not have foreign citizenship. The Israeli military does not allow Palestinians to appeal in such cases.

Until 2000, Israel allowed Palestinians who married non-registered foreigners or had a non-registered parent or child, to apply for “family reunification” with them; if approved, Israel would register the relative as a resident of the West Bank or Gaza. Israeli authorities granted far fewer requests than were submitted. By the late 1970s, Israel had granted around 50,000 family reunification applications, with 150,000 requests pending. Between 1973 and 1983, Israel granted approximately 1,000 requests annually, and only a few hundred per year subsequently.[11] In 1993 it instituted a quota of 2,000 requests per year, which it increased in 2000 to 4,000 per year.

As noted, after September 2000 Israel largely froze the “family reunification” procedure. It continued to register children who had at least one registered Palestinian parent and were born in the West Bank or Gaza, but stopped allowing most others to register, including the spouses and parents of registered Palestinians, even if they had lived in the occupied territory for years. The Palestinian Authority, which receives applications from Palestinians and transfers them to Israel for approval, estimated that from 2000 to 2005, it had relayed more than 120,000 applications for family reunification that Israel did not process.

From 2007 to 2009, Israel allowed a limited quota of Palestinians to register and to change their addresses, but set the quota in the context of political negotiations rather than on the basis of any obligation to respect Palestinians’ rights, such as the right to live with their families. These measures were inadequate even to clear the backlog of cases since 2000, and have created stark disparities within the same families among family members who have received very different treatment.

Restrictions on Gaza Residents

Although Israel withdrew civilian settlers and ground forces from Gaza in 2005, after 38 years, it continues to control the population registry there, and policies based on this control can severely affect Gazans’ lives.[12]

It is almost impossible for non-registered Palestinians in Gaza to enter Israel for medical treatments that are unavailable in Gaza’s lower-quality hospitals.[13] Since May 2011, when Egypt eased restrictions on the movement of people through the southern Rafah border it shares with Gaza, most registered Gaza residents have been eligible to travel abroad via Egypt.[14]However, non-registered Palestinians continue to face restrictions because Egyptian border officials still require Palestinians to present the identification cards that are linked to the Israeli-controlled population registry.

Since 2000, Israel has also prevented Palestinians who are registered as Gaza residents, but who live in the West Bank, from updating their addresses accordingly. Approximately 35,000 Palestinians from Gaza who entered the West Bank remain there without valid permits, according to Israeli military records; Israel has allowed around 2,800 people to change their addresses from Gaza to the West Bank. Under Israeli military orders in force since 2010, Gaza-registered Palestinians are not lawful residents of the West Bank but criminal “infiltrators,” although Israeli military authorities are not known to have prosecuted any Palestinians under these military orders.

In one case, Israeli military authorities registered Abdullah Alsaafin, 50, as a resident of Gaza, where he was born. His wife was registered as a West Bank resident. Alsaafin, his wife, and their four children are also naturalized British citizens. In 2009, while the family was living in the West Bank, Alsaafin’s oldest son left the West Bank to seek work abroad. Israeli border officials told him he would not be allowed to return because he was registered as a Gaza resident. Israel also unexpectedly changed the registered address of Alsaafin’s wife from the West Bank to Gaza. Israel considered her to be unlawfully present in the West Bank, and she was afraid to travel through checkpoints or to leave the West Bank for fear that Israel would bar her return. In August 2009, Alsaafin, who was working as a journalist, traveled to Gaza with his UK passport. Israeli officials at the Gaza crossing confiscated his press credentials, stamped his UK passport to indicate he was a Gaza resident, and refused to let him to return to his family in the West Bank. He could not leave Gaza for four months, when he was finally able to travel to Egypt.

In June 2011, following interventions by an Israeli rights organization, the Israel authorities re-registered Alsaafin’s wife and oldest son as West Bank residents, but then in November 2011 reversed this decision regarding his oldest son’s status and listed him again as a Gaza resident. Israel has refused Alsaafin’s requests to change his address or to let him visit or return to his family in the West Bank. He has found work training journalists in Beirut, Amman, and Abu Dhabi. “I communicate with my family through Skype and the internet,” Alsaafin said. “On paper, I am married, but in reality it’s as if I have no wife and children.”

Some Palestinians registered as Gaza residents can obtain temporary “permits to remain” from Israeli authorities in the West Bank, which enable them to pass checkpoints and in some cases to travel abroad. However, permit-holders said that Israeli authorities did not renew their expired permits quickly or predictably, and that they were afraid to travel while waiting for their permits to be renewed, because soldiers at checkpoints would consider them to be present unlawfully in the West Bank.[15]

Gaza residents without permits who are stopped at any of the scores of Israeli military checkpoints in the West Bank risk being forcibly transferred back to Gaza, even if they have lived in the West Bank for years and have family and professional ties there. Israel forcibly transferred at least 94 Gazans from the West Bank to Gaza between 2004 and 2010.

In many cases, the military has not provided specific security justifications for forcibly transferring Palestinians to Gaza. In 2010, Israel revised military orders to define all persons present in the West Bank without a valid permit—excluding Israeli settlers—as “infiltrators” subject to criminal penalties, including deportation. The military says the order applies to thousands of Palestinians from Gaza whom Israel previously allowed to travel to and reside in the West Bank. Israel has generally refused to issue permits to Gaza residents for entry to the West Bank since 2000, while Israeli restrictions make it virtually impossible for Palestinians from the West Bank to visit Gaza and return.

After September 2000 and subsequently, amid attacks on Israeli civilians by Palestinian armed groups, Israel also stopped allowing non-registered Palestinians to enter the occupied West Bank and Gaza.[16] (Israel retained direct control over all Gaza’s borders until 2005, and indirect control over the southern border with Egypt until Hamas took over in 2007).[17] Israel’s policy of denying entry made it virtually impossible for non-registered Palestinians outside the West Bank and Gaza to visit, much less live with their families. In most cases Israel continues to prevent non-registered Palestinians and Palestinians registered as Gaza residents from entering the West Bank.

A Bargaining Chip

Israel appears to view its control of the population registry as a political bargaining chip.

Israeli authorities have argued that Israel’s High Court lacks jurisdiction to address its control of the population registry because it is a political matter. The court subsequently dismissed petitions regarding the registry without considering the individual rights at stake, accepting the state’s argument that the court should not “interfere with policy that has been adopted by government with regard to the security situation and the development of relations between the Palestinian Authority and the State of Israel.”[18]

In 2007 Israel said it would consider up to 50,000 family reunification requests meeting specific criteria as part of a political “gesture” to the PA, in the context of peace negotiations. It processed a backlog of around 33,000 requests from November 2007 until March 2009, after which point it has not granted any further family reunification applications.

Moreover, the “gesture” applied only to Palestinians who met criteria based on other unlawfully restrictive Israeli policies; it excludes, for example, Palestinians who entered and remained in the West Bank and Gaza without Israeli permits, which Israel generally stopped granting after September 2000. More recently, Israel has taken positive but limited steps to address Palestinians registered as Gaza residents who live “illegally” in the West Bank. In February 2011, Israel agreed with the Quartet (the United States, European Union, Russia, and the United Nations) to process 5,000 address-change applications submitted by registered residents of Gaza who had moved to the West Bank. By October 2011 it had processed around 2,800 of 3,700 applications submitted.

Although the quotas cleared part of the backlog of recent applications, Israel is not processing Palestinian applications for family reunification or address changes on an ongoing basis. Nor do the quotas solve the core problem that Israel refuses to acknowledge its obligation to respect Palestinians’ rights to live with their families and to move within and travel abroad from occupied Palestinian territory. They also do not resolve the rights violations created by Israeli policies related to the population registry, such as criminalizing Palestinians who live in the West Bank but whose registered address is Gaza.

Legal Obligations

Rather than issuing post-hoc quotas that only partly repair the damage caused by its arbitrary policies, Israel should revise those policies to comply with its obligation to respect Palestinians’ human rights. As noted, all states are obligated to respect international human rights law as codified in the various human rights treaties to which that state is a signatory regardless of the parallel application of international humanitarian law.

In addition, as the occupying military power, Israel must respect international humanitarian law regarding the Palestinian population under its effective control. Israel has sought to justify its violations of protections of family rights under the law of occupation, including the Hague Regulations of 1907 and the Geneva Conventions, based on claims regarding its security.

While international human rights law and humanitarian law permits Israeli military authorities to restrict certain rights for security reasons, these restrictions must be narrowly tailored to a specific threat. Israel’s blanket restrictions on all Palestinians’ rights to freedom of movement, a home, and family life, which have separated families and destroyed livelihoods in cases where the authorities have not claimed that the people affected posed any security risk, greatly exceed this limitation.

The same restrictions on Israeli conduct exist in the portion of international humanitarian law governing Israel’s role as an occupying power. That law allows Israel to introduce laws and regulations in Palestinian territory that it occupies only as necessary to ensure security and to promote the welfare of the local Palestinian population, by enabling Palestinians to go about their normal daily lives. This necessarily entails living with one’s family and the ability to move freely for personal and professional reasons, for example to visit family, pursue higher education, or travel for a job.

Furthermore, Israel’s justification of aspects of its ongoing “freeze” on changes to the population registry by reference to the second intifada, and to Hamas’s control of the Gaza Strip, appears to collectively punish affected Palestinians for the acts of others, which applicable international humanitarian law and human rights law prohibits.

Given these obligations, Israel should abrogate all arbitrary restrictions on the recognition of Palestinians’ residency rights, including its continuing denial of residency to persons excluded from the 1967 census. It should also actively encourage Palestinians who claim to have been unfairly excluded from residency and whose family rights have been violated to apply or re-apply for residency and compensation for past violations.

Recommendations

To the Government of Israel

- Consistent with Israel’s obligations under international human rights and humanitarian law applicable to the West Bank and Gaza, recognize and respect the residency rights of Palestinians and their family members, including the rights to reside and travel where they choose and to freely enter and leave the territory;

- Immediately cancel arbitrary restrictions on

these rights, including by:

- Ending the freeze on family reunification

applications and beginning to process them immediately, and further,

- Ending the requirement that only Palestinians who entered the territory “lawfully” are eligible to apply for family reunification, in recognition of the arbitrary nature of Israel’s denial of entry permits to all non-registered Palestinians after September 2000;

- Ending any quotas on family reunification requests, and processing both backlogged requests and new requests expeditiously, notwithstanding applications that have already been considered as part of the 2007 “political gesture” to the PA, due to the arbitrariness of former restrictions on eligibility;

- Ending the freeze on family reunification

applications and beginning to process them immediately, and further,

- Allowing registered Palestinian residents of Gaza to change their registered addresses to the West Bank, move from Gaza to the West Bank, and travel between the two, except for narrowly tailored security reasons, and ending the freeze on changes to addresses;

- Ending the freeze on granting “entry” or “visitor” permits to non-resident Palestinians, residents’ non-registered spouses, children, and family members who seek to enter Palestinian territory;

- Cancelling any policy and any orders, regulations, or laws that deem Palestinians in the West Bank to be “illegally present” there on the basis that their registered address is Gaza;

- Amending or cancelling as necessary current military orders, regulations, or procedures that limit the categories of Palestinians registered as residents of Gaza who may apply to change their residency to the West Bank;

- Amending or cancelling as necessary any military orders, regulations, or procedures that limit the ability of Palestinians to leave and re-enter Palestinian territory as they wish, except for narrowly tailored security reasons.

- Open for consideration, based on criteria

consistent with human rights law and IHL, applications for residency by persons

who were previously excluded from eligibility for residency in possible

violation of Israel’s international legal obligations, including:

- Palestinians who were not registered in the 1967 census of the recently-occupied Palestinian territory because they had fled or were displaced during fighting or were abroad for any other reason at the time;

- Palestinians whose residency status was cancelled on the basis of unlawfully restrictive criteria, such as that they remained outside the West Bank or Gaza for periods that exceeded “exit visas” that were of short duration;

- Palestinians whose applications for family reunification were denied on the basis that they failed to meet various other arbitrary criteria, such as the requirement that a child’s mother be a registered resident of the West Bank or Gaza.

- Proactively seek to ensure that such persons are notified of their eligibility to apply or reapply for residency, including persons living outside the West Bank and Gaza, such as by publishing notifications, sharing relevant information with other governments and international agencies, and through any other means.

- Establish procedures to ensure that new applications are processed expeditiously, rather than adding to the large existing backlog, and that applicants are informed in writing of specific reasons for the denial of applications.

To the Government of Egypt

Revise policies at the Rafah border crossing with Gaza to ensure respect for the rights of Palestinians, including by ending the de facto requirement that Palestinians present Israeli-approved identity documents in order to enter Gaza.

To the Palestinian Authority

Resume accepting and processing all applications related to population registry issues, including applications for residency through family reunification, and address changes, without regard to the Israeli freeze on the population registry, such that an up-to-date file of applications will be immediately available when the Israeli side assumes its international legal obligations in this regard.

To the Quartet

Continue to encourage the Israeli side to meet its international legal obligations, including by allowing Gaza-registered residents to change their registered address to the West Bank.

To Third Party States

Consistent with their obligations as third parties under international law including the Geneva Conventions, ensure that their policies do not have the effect of recognizing or supporting Israeli actions or policies that violate its international legal obligations as the occupying power, such as by imposing differing restrictions on the entry of Palestinians depending on whether Israel considers them to be residents of the West Bank or Gaza, or with regard to unlawful Israeli restrictions against their citizens on the basis of their Palestinian origin.

Methodology

This report is based on interviews, conducted primarily in the spring of 2011, with 32 Palestinians who were unable to register as residents of the West Bank and Gaza, unable to change their residency from Gaza to the West Bank, or experienced other difficulties related to Israel’s restrictions on changes to the Palestinian population registry. All but three of the interviews were conducted in Arabic; all but one of the interviews were conducted in-person in the West Bank and Gaza.

Human Rights Watch initially identified these interviewees by contacting nongovernmental groups and journalists who had worked on or written about the issue of Israel’s population registry, as well as by asking individuals in Gaza and the West Bank if they were aware of the issue and anyone affected by it. Human Rights Watch did not seek to identify or interview people who did not have residency-related problems.

Most interviews lasted from an hour to several hours, except for two conversations which were briefer. In most cases Human Rights Watch had access to additional corroborating documentation such as passports, travel documents, visas, entry permits, photographs, and letters.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed or corresponded with Palestinian and Israeli officials responsible for population registry issues in the West Bank and Gaza. The report further draws on Israeli court rulings, government documents, and records, and information provided by Israeli authorities in the course of court proceedings or in response to requests by Israeli nongovernmental organizations. Human Rights Watch also interviewed Israeli lawyers who represented Palestinian clients in several of the cases discussed.

This report does not include research or interviews regarding the situation of Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem. East Jerusalem is considered part of the occupied West Bank under international humanitarian law.[19] However, Israeli authorities do not include East Jerusalem residents in the Palestinian population registry, the subject of this report.

I. Background to Current Israeli Policies

Control of the Registry from the Occupation to the Oslo Accords (1967- 1994)

Israel seized control of the West Bank and Gaza from Jordan and Egypt, respectively, in June 1967.[20] That year, Israeli military authorities declared the occupied Palestinian territory to be “closed areas” and required Palestinian residents to obtain permits from the military authorities in order to enter or leave.[21] In August and September 1967, the Israeli military conducted a census of Palestinians who were physically present in the occupied Palestinian territory, which became the basis for an Israeli registry of the Palestinian population there. The population of the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) and Gaza, as recorded by the 1967 census, was 954,898.[22] Following the census, Israel issued identification documents (ID cards) to Palestinians registered in the population registry. Under Israeli military orders, bearers of these ID cards were not granted Israeli citizenship but were allowed to reside, work, and own and inherit property in the occupied territory.[23] Non-registered Palestinians had to obtain temporary visitor permits in order to enter the occupied Palestinian territory, and could not permanently reside there. Among the Palestinians whom the 1967 Israeli census did not register were Palestinians from the West Bank and Gaza who were displaced during the fighting in 1967 and had not returned by the time of the census, as well as Palestinians who were residing abroad at the time for work, study, or any other reason. For example, one man, Muhammad N., who was born in Gaza told Human Rights Watch,

My father told me that when the soldiers came [to conduct the census], he told them that I was studying in Egypt, and the soldier said, “So forget about him, he’s not here.”Since that time, every time I wanted to enter to visit my parents here from Egypt, my father would have to ask the Israelis for a permit for me. I could stay for maximum of three months.[24]

The 1967 conflict displaced at least 270,000 Palestinians from the West Bank and Gaza.[25] Other estimates are significantly higher: for example, the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA) estimated that the 1967 conflict displaced about 390,000 Palestinians from the occupied Palestinian territory.[26]

The Israeli military’s control of the Palestinian population registry also affected the hundreds of thousands of Palestinians who left Gaza and the West Bank shortly after Israel occupied the territory.[27] Israeli officials encouraged Palestinians to emigrate after June 1967.[28] The Israeli military required Palestinians who left the occupied Palestinian territory to leave behind the ID cards they had received from the military government, and sign or thumbprint a form declaring, in Hebrew and Arabic, that they were leaving willingly and understood that they would not be able to return without a special permit; husbands signed for their wives.[29] Israel deleted from the population registry Palestinians who left and remained outside the occupied Palestinian territory for periods that exceeded the duration of the “exit permits” that the Israeli military issued to them upon their departure.[30] In such cases, Israel subsequently refused to allow them to reside permanently in the occupied Palestinian territory. For instance, Khadija, the wife of Muhammad N., quoted above, told Human Rights Watch that she left her home in Gaza after she was initially counted in the 1967 census:

It turned out that I was supposed to come back and renew my exit permission within six months. I missed the appointment and they cancelled me, but I didn’t know about the requirement. There was nothing I could do about it. Every time I came back to Gaza after that, I had to get a visitor’s permit beforehand.[31]

In total, the Israeli military has stated that between 1967 and 1994 it cancelled the residency of some 140,000 Palestinians; of this total, it re-registered about 10,000 people after 1995.[32] Currently, there is no procedure by which Palestinians can contest or overturn what the military refers to as “ceased residency” status.

In September 1967, the Israeli military established a “family reunification” process by which registered Palestinians could apply for residency in the occupied Palestinian territory on behalf of first-degree relatives who had been “permanent residents” before becoming refugees abroad.[33] This was the only process by which Palestinians could obtain permanent residency status in the occupied Palestinian territory, including those who sought to return to their homes. However, Israel severely and apparently arbitrarily restricted eligibility for “family reunification”. For example, it excluded all men between the ages of 16 and 60 who had left from being able to return and obtain residency status.[34] According to one Israeli source, Israeli authorities granted around 45,000 out of 140,000 family reunification requests submitted from 1967 to 1973.[35]

In 1973, Israel introduced stricter criteria for family reunification, and argued—as it continues to do—that it is not obliged to uphold family reunification as a human right for Palestinians in the OPT; rather, Israel argues that family reunification is a discretionary “special benevolent act of the Israeli authorities.”[36] Israel has also maintained that, in deciding whether to grant family reunification requests, the authorities may take into account “security considerations,” which it defined broadly to include “political considerations relating to the international relations of the state.”[37] By 1979, according to one estimate, 150,000 family reunification requests were pending, but the Israeli authorities granted approximately 1,000 requests annually from 1973 to 1983.[38]

Israeli authorities restricted the family reunification policy again in 1983, for the stated reason that, by that point, most “requests for family reunification [had] deviated from the original objectives of the said policy, dealing instead with families that had been created after the war.”[39] Israel limited family reunification to cases that met “highly exceptional and unique” humanitarian or administrative criteria. According to the Israeli human rights group B’Tselem, “figures published by various sources indicate that only a few hundred requests were approved annually after 1984.”[40]

The Israeli Civil Administration, the branch of the military, established in 1981, that is responsible for the Palestinian population registry, set a new hurdle for Palestinians in 1985: it began to deny visitor permits to the spouses, living outside the OPT, of registered Palestinian residents who had filed family reunification applications on their spouses’ behalf.[41] The Civil Administration also deemed spouses and other relatives to be illegally present in the OPT if they had overstayed their visitor permits while their family reunification requests were pending. On this basis, in 1989 Israel deported around 200 Palestinian women and children with pending family reunification applications from the occupied Palestinian territory. After these deportations of Palestinian civilians attracted international condemnation, and Israeli human rights organizations petitioned the High Court of Justice on their behalf, Israel allowed the women and children to return in June 1990 and granted them the status of “long-term visitors,” with renewable, six-month residency permits.[42] (The offer was also valid for similarly-situated applicants for family reunification.) Israel refused to extend that status to people who entered after June 1990, and again deported at least 10 women and children for overstaying their visitor permits in 1991.[43] Following fresh petitions by the Israeli rights group Hamoked, the Israeli military stated in 1992, and again in 1994, that it would grant long-term visitor permits to people who entered the occupied Palestinian territory during later time periods.[44]

The Israeli military has not always implemented its stated policies regarding these so-called “High Court populations” of Palestinians (those who entered during time periods specified in court proceedings). In some cases the Civil Administration issued members of these groups visitor permits valid for only one month rather than six months; from November 1995 to August 1996 it refused to extend the visitor permits at all, and stopped processing some family reunification requests.[45] In 2004, the Civil Administration, which was still processing the family reunification applications of some members of these groups, altered its policy and introduced a contrary, retroactive requirement that the person being sponsored for residency must have been physically present and had their “center of life” in the occupied Palestinian territory for an unspecified prior period. Previously, as noted, the Civil Administration had deported these Palestinians from the occupied Palestinian territory, and had refused to process family reunification applications on behalf of any person who was present in the territory.[46] Israel has not clearly defined its “center of life” criteria.[47]

The Oslo Period Prior to the Second Intifada (1995 -2000)

In 1995, Israel and Palestinian representatives signed an Interim Agreement, commonly referred to as the second “Oslo accord,” that formally transferred “powers and responsibilities in the sphere of population registry and documentation in the West Bank and Gaza Strip … to the Palestinian side.”[48] Under the Agreement, “the Palestinian side shall maintain and administer a population registry and issue certificates and documents of all types” (Article 2), and is obliged to “provide Israel, on a regular basis,” with information regarding the residents to whom it granted passports and identification cards. The Palestinian side must also “inform Israel of every change in its population registry, including, inter alia, any change in the place of residence of any resident” (Article 10 a-b). Pursuant to the agreement, the Palestinian side could exercise these rights regarding persons whom Israel had already registered as residents. With regard to the registration of new residents, according to the agreement, “the Palestinian side has the right, with the prior approval of Israel, to grant permanent residency” to foreign investors, spouses, children of Palestinian residents, and other persons, for humanitarian reasons, in order to promote and upgrade family reunification (article 11 a-c).

The agreement also granted to the Palestinian side “the right to register in the population registry all persons who were born abroad or in the Gaza Strip and West Bank, if under the age of sixteen years and either of their parents is a resident of the Gaza Strip and West Bank” (Article 12). Previously, from the first intifada in 1987 until January 1995, the Israeli military stopped registering all children (under 16) whose mother was not a resident of the OPT, even if the child was born there, and all children born abroad who were more than five years old, regardless of either parent’s residency status.[49]

The Interim Agreement thus provided, in general, that Israel was to maintain a copy of the population registry, which it would update with information provided to it by the Palestinian side, which would maintain the master document. However, Israel’s version of the registry continued to function as the original, because Israeli soldiers on the ground would act based on Israel’s version of the registry. In practice, the Israeli military authorities retained control of the population registry after signing the Interim Agreement. In the case of family reunification requests, for example, Israeli authorities cited the clause of the agreement that granted them the power of “prior approval” over the registration of new residents. Israel also capped the number of new residents whom the Palestinian Authority would be allowed to register at an annual quota; Israel announced a first quota of 2,000 family unification approvals in August 1993 as a positive political “gesture” in the context of ongoing peace talks. According to Khalil Faraj, deputy director of the PA’s Civil Affairs Ministry in Gaza, “the PA started in 1994 by asking Israel for 800 ID cards [i.e. newly-registered residents] for Gaza per year, and 1,200 for the West Bank. The quota request got bigger each year.”[50] In 1995, Israel refused the PA’s demand to end or increase the quota; from 1996 to 1998, the PA protested by not forwarding family reunification requests to Israel for approval.[51]

By mid-1998, there was a backlog of more than 17,500 requests for family reunification.[52] Israel raised the quota to 3,000 a year in October 1998, and to 4,000 a year in early 2000.[53] This higher quota remained in effect for less than a year, as Israel suspended processing requests after the outbreak of the second intifada in late September 2000.

Ayman Qandil, a West Bank-based official with the Palestinian Authority Ministry of Civil Affairs responsible for dealing with the population registry, described relations between the Palestinian and Israeli sides from 1995 to 2000:

We submitted lists of names to the Israelis to include in the registry, which was more practical than asking them to deal with applications on an individual basis. Under the Oslo agreement, the PA Ministry of Interior was supposed to get the file, but our Civil Affairs Ministry took it over at the beginning of 2000, because we were the ones charged with liaison with the Israeli authorities, and they had maintained control over the registry. The process [for Palestinians was that] you’d go to the Interior Ministry with your application, and they’d pass it to us at Civil Affairs, and we’d tell the Israelis, and they’d reply only if there was a security objection.[54]

The PA’s nominal authority to issue new ID cards (with prior Israeli approval) was limited in practice by Israel’s actual control over Palestinian movement to, from, and within the occupied Palestinian territory (Israel withdrew its settlers and ground forces from Gaza in 2005 but subsequently continued to control movement in and out of Gaza, including on the Egyptian border, until 2007).[55] Amira Hass, writing in the Israeli daily Haaretz, described the situation:

The PA cannot act unilaterally and issue Palestinian identity cards to people without Israel’s consent, because [Israel’s] control over the PA population registry is rooted in its control over the international border crossings and Palestinian movement within the West Bank: the minute an Israeli soldier at a checkpoint or border crossing checked such a card [issued by the PA without Israeli approval], he would discover that its holder does not appear in Israel’s computers, and treat the card as invalid.[56]

II. Israel’s “Freeze” of the Population Registry

Following the outbreak of the second intifada on September 29, 2000, the Israeli Civil Administration “froze” most changes to the population registry and this freeze remains in effect. The only changes it regularly continues to process are requests to register children under 16 years old who were born to a Palestinian parent who was a registered resident, and where the child is physically present in the territory at the time of application for residency.[57] It has ceased processing other requests.

According to Ayman Qandil, the Palestinian official at the Palestinian Authority Ministry of Civil Affairs responsible for dealing with the population registry, Israel did not provide the PA or affected individuals with prior notification of its freeze policy, but stopped accepting or acknowledging receipt of cases presented to it by the PA for family reunification, changes of address for Palestinians who had moved from Gaza to the West Bank, and other categories that were included in the Interim Agreement, such as “visas for foreigners who were working in the West Bank for NGOs or the PA, and requests from investors from other countries who were supposed to get visas because they were going to do business here.”[58]

Israel in 2007 pledged, as a political gesture, to process a quota of 50,000 applications for residency filed by registered Palestinians on behalf of unregistered parents, children, or spouses (called the “family reunification” procedure); it has processed around 33,000 applications. Israel similarly pledged in 2011 to process 5,000 applications by Palestinians to change their registered addresses from Gaza to the West Bank, because Israel considers them to be living in the West Bank illegally.

These positive steps fall short of what is needed to remedy the situation of Palestinians affected by Israel’s refusal, for more than 11 years, to change or update the population registry on an ongoing basis. By ending the family reunification procedure, the “freeze” ended the only available means for registered Palestinians to live with their families on terms that Israel considers lawful. The “freeze” also closed off the only avenue for Palestinians who were living in the West Bank but are registered as residents of Gaza to change their addresses. Whenever they seek to cross a West Bank checkpoint or to travel abroad, both “Gazans” and unregistered Palestinians or their families are at risk of harassment by Israeli security forces, detention, deportation abroad, forcible transfer to Gaza, or a ban on reentry. Israel’s “freeze” policy has separated families and unlawfully restricted Palestinians’ freedom of movement and their movement-dependent rights to work, study, seek medical care, and many other rights.

Freeze on Address Changes and “Illegal Presence” in the West Bank

Israel registers the addresses of Palestinian residents of the occupied territory, and ID cards indicate whether the bearer is a resident of the West Bank or Gaza. Military Order 297 of 1969, which remained valid until 1995, required residents of the occupied Palestinian territory to notify the Israeli military of a change of address within 30 days.[59] The 1995 Interim Agreement granted the Palestinian side the right to change the registered addresses of Palestinian residents.[60] Since 2000, however, Israel has refused to reflect most changes of address in the population registry. As a result, Israel has prevented Palestinians who had moved from Gaza to the West Bank from changing their addresses and thereby making their presence in the West Bank legal.[61] Israeli authorities have subsequently claimed that Palestinians who are registered as Gaza residents, but who are living in the West Bank, are there illegally.

The Israeli military estimates that around 35,000 Palestinians whose registered address is Gaza may now be present in the West Bank “illegally.” [62] Prior to the second intifada, Israeli military records show, 935 residents of Gaza traveled to the West Bank using individual permits to enter, and remained there, and another 7,919 Gaza residents entered the West Bank according to the “safe passage” procedure and remained there subsequently.[63] In addition, between late 2000 and April 2010, according to the Israeli military, 23,348 residents of Gaza used individual transit permits to travel to the West Bank, and have remained there.[64] Even Palestinians who were born in the West Bank are considered to be there illegally if their parents are registered as Gaza residents: according to the military, “2,479 Palestinians who were born in Judea and Samaria [Israel’s term for the West Bank] are registered as residents of the Gaza Strip.”[65]

Beginning in 2003, Israeli authorities arrested and forcibly transferred some Palestinians from the West Bank, including people who had homes, families, and jobs there, to Gaza on the basis that their registered address was there.[66] Israeli authorities stated that the deportations were conducted because Palestinians registered as Gaza residents were prohibited from being present in the West Bank, unless they had special permits (for example, temporary permits allowing for treatment in hospitals). Israeli rights groups have argued that Israeli policy since 2000 has created a “one-way street” from the West Bank to Gaza, citing offers by Israeli military authorities in various cases to grant West Bank residents a “single, one way permit to travel to Gaza” if they promise to remain there or sign undertakings not to seek to return to the West Bank in exchange for permission to travel to Gaza; in such cases Israeli authorities were willing to change the applicant’s address from the West Bank to Gaza.[67] Between 2004 and 2010, Israel deported 94 Palestinians from the West Bank to Gaza, but apparently transferred none in the other direction.[68] Israeli rights groups have noted a similar trend in the small minority of cases where Israeli authorities processed Palestinian requests for changes of address between Gaza and the West Bank since imposing a general “freeze” on such changes in 2000. Between2002 and May 2010, Israel approved 388requests by residents of Gaza to change their registered address to the West Bank, and 629 requests of West Bank residents to change their address to Gaza.[69]

Israel’s position is that it has always required military permission for any Palestinian to enter or be present in the West Bank—before as well as after the outbreak of the second intifada in 2000—on the basis of a 1967 military order declaring the West Bank to be a closed area for which all persons required military permits to enter and stay.[70] According to the state attorney, “Israel retained this power even after the transfer of civil powers to the Palestinians” under the 1995 Interim Agreement, and simply agreed to process Palestinian requests for address changes until September 2000, when “it was decided that as a rule, requests to permanently move from one region to the other would not be handled.”[71] The Israeli state attorney has repeatedly urged domestic courts not to adjudicate issues regarding Gazans’ residency in the West Bank on the basis that it is a political question relating to foreign relations between Israel and the PA.[72]

As discussed above, the Interim Agreement states that the Palestinian side need only notify the Israeli side of changes of address after the fact; Israeli military orders that incorporated the Interim Agreement contained no provision authorizing the military to expel a Palestinian from the West Bank to Gaza for failing to update his or her “place of residence.” Israeli rights groups have thus argued that subsequent military orders authorizing such expulsions are arbitrary within the framework of Israeli domestic law, in addition to violating Israel’s obligations under the law of occupation to respect Palestinians’ human rights.

Israeli human rights NGOs challenged the change in Israeli policy before the High Court, arguing that the military does not have the authority to exclude Palestinians residing in Gaza from residency rights in the West Bank or to “deport” Palestinians, whose registered address is in Gaza, from the West Bank to the Gaza Strip.[73] The groups argued that the policy would retroactively render large numbers of Palestinians “illegally present” even though they had entered the West Bank lawfully, such as the thousands of people who used the “safe passage” process in 1999 and 2000, when the Israeli military gave them permits to cross through Israel but did not provide or require a separate permit to reside in the West Bank. According to the military, “Gaza residents are not ‘exempt’ from the duty to obtain permits to enter and stay in Judea and Samaria. […] Anyone having entered the area prior to the year 2000 is required to return to his home in Gaza upon cancellation of the safe passage.”[74]

The Israeli High Court has held that under certain circumstances, and if accompanied by procedural protections such as a hearing, the military can “assign the residence” of a Palestinian from the West Bank to the Gaza Strip, forcing that person to move to Gaza, as a “preventive” measure needed for security reasons.[75] According to this procedure, the military commander of the West Bank must issue a “Designation of Residence Order” notifying those designated for expulsion of the intent to remove them, in order to enable the individual to appeal the decision before a military appeals committee and to petition the court.[76]

In contrast to expulsion for security reasons, however, the military did not issue a “Designation of Residence Order” or otherwise give prior notice to any of the Palestinians whom it deported on the grounds of being illegally present in the West Bank.[77] Unlike individuals designated as security threats, Palestinians who were unable to change their addresses from Gaza to the West Bank were deported without a hearing.[78] In response, the High Court ruled that the military “ought to” create a procedure that granted military judicial review to detained Palestinians pending their deportation, “according to clear and defined rules.”[79]

As a result, according to the state attorney, the Israeli military issued two orders that came into effect in April 2010. Order No. 1649 creates a military judicial committee to review the cases of Palestinians who are subject to deportation, a form of judicial process that did not exist under previous military orders.[80] The order provides that the military must bring the detainee’s case before a committee of military judges within eight days, but that the military could deport the detainee within 72 hours. The military has stated that it “intends” to inform the person slated for deportation of his rights within those 72 hours, including to have a person notified of his detention and to request the military committee to review his deportation order.[81] Before the military order came into force, Israel had deported some Palestinians to Gaza immediately upon arrest without detaining them for 72 hours.[82]

While Order No. 1649 creates a hearing, its companion, Order No. 1650, appears to dramatically increase the number of Palestinians who could be subject to deportation.[83] According to Order No. 1650, any person who entered the West Bank “unlawfully” or “who is present in the [West Bank] and does not lawfully hold a permit” is considered an “infiltrator” who may be imprisoned and deported.[84] The military subsequently stated that any person who lacks a military permit to reside in the West Bank would be considered “illegally” present.[85] As discussed, the military estimates that around 35,000 Gazan Palestinians currently live in the West Bank; the new military order renders them criminal infiltrators even though they are registered as residents of the occupied Palestinian territory.[86] Human Rights Watch is not aware that the Israeli military has criminally prosecuted or forcibly removed any Palestinians on the basis of Military Order No. 1650. Before the order came into force, Israel’s state attorney informed the High Court of Justice that the state had the authority to deport anyone “illegally” present in the West Bank, but that the general policy was not to deport “Gazans” who had moved to the West Bank before 2000.[87]

In prior cases, Israel had justified its forcible transfer of Palestinians from the West Bank to Gaza on the grounds that the occupied Palestinian territory is a “single territorial unit” and that their forcible transfer to Gaza amounted to “assigning their residence” within an occupied territory for security reasons, which the Geneva Conventions permit, rather than “deporting” them, which the Geneva Conventions prohibit as a war crime.[88]

Forcibly transferring Palestinians from the West Bank to Gaza would be consistent with Israel’s human rights obligations only in cases where Israeli authorities could show evidence that the person presented a clear security threat, that forcible transfer to Gaza would remove the threat, that forcible transfer was absolutely necessary, and where the authorities balanced the necessity of the transfer against the harm to the person’s rights, such as the right to a family. Israel would be obliged to allow the person to see and challenge the evidence against them and to present their own evidence.

The High Court has failed to overturn the military’s deportation of persons from the West Bank to Gaza for whom the military did not claim to present any security threat and whom it deported without granting them a hearing or any other process. For example, in 2009 the Israeli military blindfolded, handcuffed, and deported Berlanty Azzam, a student at Bethlehem University, two months before her final exams on the sole basis that she was “illegally present” in the West Bank. The state attorney did not present any evidence that she constituted a security threat, and argued rather that she was “illegally present” in the West Bank because she did not possess a valid “permit to remain” in the West Bank. Israeli authorities had denied her request for permission to study at a West Bank university, and she had entered lawfully in 2005 on a permit issued for religious worship; the military subsequently had denied her repeated applications to change her address from Gaza to the West Bank. The court rejected her petition to be allowed to return to the West Bank to complete her studies on the grounds that she had misused her permit in 2005.[89]

The military first began to issue “permits to remain” in the West Bank to Palestinian residents of Gaza in November 2007.[90]As the Azzam case indicates, Israel does not consider education to be a right that obliges it to grant permits to Palestinians from Gaza to remain in the West Bank in order to study. The Israeli military has argued, and the High Court has accepted, that “the universities [of the West Bank] are ‘hothouses’ for breeding terrorists,” where students from Gaza could become dangerous even if they have never taken hostile actions in the past.[91] The court, while acknowledging that “in an ideal world individualized investigations would be the best way to achieve a just outcome”, nonetheless accepted the argument that more attacks against Israelis would likely result if the military individually screened Palestinian applicants seeking to travel for educational reasons from Gaza to the West Bank, rather than their current policy of a blanket refusal to issue permits for education.[92] Similarly, according to Israeli policy as determined by the deputy minister of defense, “a family relationship, in and of itself, does not qualify as a humanitarian reason that would justify settlement by Gaza residents” in the West Bank.[93] The extraordinarily broad security rationale for denying Gaza residents the right to travel to the West Bank to study or even to visit family violates Israel’s human rights obligations, which permit infringing these rights only according to narrowly-tailored security requirements applicable on an individual basis.

Currently, according to the Israeli military, only Palestinians who are married with children, who can prove that they were present in the West Bank for the past eight years continuously, who pass security and police clearances, and who provide “humanitarian” grounds are eligible to apply for a temporary “permit to remain” in the West Bank.[94] Palestinians who obtain “permits to remain” must obtain advance permission, known as “coordination,” from Israel and a “non-objection certificate” from Jordanian authorities before being allowed to leave the West Bank (see below).

Israeli military policy is extremely restrictive regarding exceptions to the freeze on changes of address from Gaza to the West Bank. Under Israeli policy, three types of Palestinians are eligible to change their address from Gaza to the West Bank:

a) A resident of Gaza who suffers from an ongoing (chronic) medical condition which requires assistance by a family member who is a resident of the Judea and Samaria Area, and who has no other family member (not necessarily of the first degree) who is a resident of Gaza who is able to assist the patient.

b) A minor resident of Gaza who is under 16 years of age, where one of the parents, a Gaza resident, died and the other parent is a resident of the Judea and Samaria area, and there is no other relative who is a Gaza resident who can take care of the minor. If need be, the quality and extent of the existing relationship with the parent who is a Judea and Samaria area resident will be evaluated in relation to the degree, quality and extent of the relationship with other relatives in Gaza.

c) An elderly person (above the age of 65) who is a resident of Gaza and who is in a needy situation, which requires the handling and supervision of family relative who is a resident of the Judea and Samaria Area, who can assist him. In the event that it is necessary, the nature and scope of the existing relationship with the family relative who is a resident of the Judea and Samaria Area shall be examined in relation to the nature and scope of the relationship with other family relatives in Gaza.[95]

On February 4, Quartet Representative Tony Blair and the Government of Israel announced, as part of a package of measures for Gaza, the West Bank, and East Jerusalem, that Israel “has agreed to authorize 5,000 West Bank residents who currently hold Gazan IDs to change their address for ID purposes to the West Bank.”[96]

Ayman Qandil, the official from the PA Civil Affairs Ministry, told Human Rights Watch:

We tried to inform people as much as possible about this move, but we received slightly less than 4,000 names, not 5,000. All of the names on our list were older than 16 years, of course. So Civil Affairs submitted all the roughly 4,000 names to the Israelis, and then on April 6 they told us that they’d approved the address changes for 298 names.[97]

There were no apparent criteria for the names approved, and the Israeli side did not communicate any objections to any names, Qandil said. On August 2, the Palestinian daily Ma’an published the names of another 1,956 Palestinians whose address changes from Gaza to the West Bank had been approved.[98] The criteria for choosing the names to be approved were not stated.

By the end of October 2011, Israel had processed around 2,775 applications, from a total of 3,700 submitted by the Palestinian side, according to Gisha, the Israeli rights group that has tracked the process.[99]

Some Palestinians whose registered address is in Gaza have obtained renewable, three- or six-month “permits to remain” in the West Bank. With the permits, which the Israeli military began to issue in 2007, they can pass through the scores of checkpoints within the West Bank.[100] (The Israeli military maintains permanent checkpoints at crossing points from the West Bank into Israel, as well as within the West Bank, notably at crossing points in the separation barrier around East Jerusalem and elsewhere in the barrier, on roads leading to settlements, and elsewhere in “Area C”, in which Israel maintains total control. Area C is contiguous, and Palestinians must pass through it in order to travel between any two cities in the territory as well as between many towns and villages. Israeli settlements are located in Area C.) Nonetheless, many Palestinians said that they still limit their travel as much as possible. As one Palestinian man put it, “In general I don’t move around much in order to avoid any friction with soldiers at the checkpoints, who can detain you for half an hour or longer when they see you’re from Gaza, checking their records or just giving you a hard time.”[101] Permit-holders can also leave and re-enter the West Bank, via the Allenby Bridge border crossing with Jordan, if they obtain advance permission from the Israeli military, known as “coordination,” described below.

Several Palestinians living in the West Bank described different occasions when Israeli authorities temporarily stopped renewing “permits to remain” altogether—for four months in 2008, according to one man, a six-month period for another.[102] During these periods, they said, they refrained from traveling within the West Bank or attempting to leave.

For permit-holders wishing to cross to Jordan, the PA Civil Affairs office contacts the Israeli Civil Administration office located at the Erez crossing on Gaza’s northern perimeter, to request “coordination” for them to leave the West Bank via the Allenby Bridge.[103]

Gazans living in the West Bank described consistent problems with the coordination process. For example, Rina Ajrami, a registered Gaza resident who has lived in the West Bank since 2001, said:

The problem is that we don’t know whether or not we received the coordination until the day before or even the same day that we plan to travel. We apply for coordination first, then we arrange to get the necessary visa [to the intended foreign destination], and then we buy the plane ticket, but whether or not we can actually leave always depends on whether we get coordination. With coordination there’s nothing written down, no piece of paper. The PA liaison just tells you over the phone what the Israelis told them, and if your coordination is denied there’s no explanation. They just say there were “security reasons.”[104]

In cases where Israel refuses to grant coordination, according to the individuals Human Rights Watch interviewed, Palestinians are notified only days or hours before they are due to depart, by which point it is often too late to change their travel plans. Many said they had missed business meetings or other appointments abroad, as well as losing the cost of their airplane tickets, due to Israeli authorities’ denial of permission. One man said he had applied to leave the West Bank ten times, and received permission only once.[105]

Palestinians registered as Gaza residents must also obtain a “certificate of no objection” from the Jordanian authorities in order to enter Jordan.[106] Wafaa Abd al-Rahman is a registered Gaza resident who has not been able to change her address to reflect the fact that she lives in Ramallah. “In addition to coordination, you have to get a no-objection permit a month in advance from the Jordanian side,” she told Human Rights Watch.

At Allenby, the Jordanians sometimes take your passport and tell you go to meet with the mukhabarat [intelligence agency]. When you return from your trip, they usually take your passport at the airport in Amman and tell you that you need to retrieve it at the intelligence headquarters.[107]

The same restrictions apply to Palestinians seeking to return to the West Bank from elsewhere via Jordan: they must receive a no-objection certificate from the Jordanian authorities in order to enter Jordan (usually via Amman airport) and travel to the Allenby Bridge, and the Israeli military must grant them “coordination” to enter the West Bank. Omar Awad Allah, a Gaza-born employee of the PA Foreign Affairs Ministry, returned from abroad in order to take up a post in the West Bank in June 2009, but had to remain in Jordan for four months while waiting for Israel to coordinate his re-entry.[108]

Israeli Civil Administration procedures introduce an additional difficulty in cases where one parent is a registered resident of the West Bank but the other is a resident of Gaza or is not a resident of the occupied Palestinian territory. In such cases the Israeli authorities “list” some of the couple’s children on one parent’s ID documents and other children with the other parent’s file. For instance, Hossam Maghari, 45, from the al-Rimal neighborhood of Gaza City, moved with his family to Ramallah immediately after Hamas took control in Gaza on June 14, 2007.[109] His employer finally obtained a “permit to remain” in the West Bank for Maghari in late 2010. “They applied for permits for my family, too, but they were rejected,” he said. As a result Maghari’s wife and children are considered by the Israeli authorities as illegal residents within the West Bank, and refrain from travel that would require them to cross checkpoints due to fears that Israeli soldiers would detain them on the basis that they could not produce evidence of their lawful presence there.

The rest of my family doesn’t travel [within the West Bank] because they don’t have permits. We have cousins in Hebron and in Jericho, but we rarely visit them. We’re aliens in our own country. I can’t let my 17-year-old boy go on any trips that require him to pass through checkpoints.

At some point, apparently after 2005, the PA stopped accepting applications from Palestinians and stopped sending registry updates and requests to the Israeli Civil Administration altogether, because the Civil Administration refused to acknowledge them. Human Rights Watch spoke with several Palestinians who criticized the PA’s handling of the issue. A PA official with the Civil Affairs office, who himself resides in the West Bank although he is registered as a Gaza resident, confirmed that for a period of time the Civil Affairs office refused to accept applications, but gave preferential treatment to PA employees by keeping their applications on file, in the event that Israel would “unfreeze” the population registry.[110]

In December 2010, the Palestinian Supreme Court ordered the PA to resume receiving and notifying the Israeli side of applications by Palestinians registered as Gaza residents but living in the West Bank to update their addresses; the PA has done so.[111] The court’s verdict found in favor of Ihab al-Ashkar, a Palestinian living in the West Bank who is registered as a Gaza resident. Al-Ashkar told Human Rights Watch that he had previously hired Israeli lawyers in six unsuccessful attempts to persuade the Israeli Civil Administration to change his address to the West Bank. Although he was aware the process was “frozen,” in 2009 he attempted to submit an application for an address change to the PA Interior Ministry, but the ministry “refused even to let me apply.”[112]

Additionally, according to Palestinian rights groups, the PA is responsible for delaying and denying Palestinian passport applications from Gaza, including for unjustified “security reasons.”[113] After Hamas took over Gaza in June 2007, the Palestinian Authority transferred its offices relating to the population registry from Gaza to the West Bank, including responsibility for printing passports. According to the Independent Commission for Human Rights, the official Palestinian rights ombudsman with offices in both the West Bank and Gaza, the PA has not sent any blank passports to Gaza since November 2008, a policy that harms Palestinians who need medical treatment abroad, “students who are studying outside the country,” and “thousands of people” whose passports have expired.[114] It is not possible to print passports in Gaza, and passport renewal applications are processed in Ramallah.[115]

Freeze on Family Reunification

For the majority of Palestinians who are not registered residents of the West Bank or Gaza—including all Palestinians over 16 years old, their foreign spouses, and others—the only possibility to obtain residency rights recognized by Israel is if a first-degree relative (a spouse, parent, child, or sibling) applies on their behalf, in what is called the “family reunification” process.

When Israel “froze” the population registry after September 2000, it also refused to accept Palestinian applications for family reunification. As a result, many Palestinians with first-degree relatives outside of the occupied Palestinian territory have been unable to gain recognized residency status for them for more than a decade.[116]

Israeli authorities have not cited specific security concerns in rejecting applications for family reunification according to the freeze policy; they have simply stopped processing such applications. The policy violates Palestinians’ rights to a family life; in cases where Israel arbitrarily excluded Palestinians from the population registry or cancelled their registration, the policy violates their rights to be able to enter and leave the occupied territory.[117]

Shortly after enacting the freeze, Israel agreed to process a small number of family reunification requests that were classified as “exceptional humanitarian cases.” According to B’Tselem’s review of relevant cases, however, Israeli authorities “consistently refrained from stating the relevant criteria in determining whether a case comes within this category.”[118]

The PA Civil Affairs Ministry estimated that from the outbreak of the second intifada to August 2005, it relayed to Israel more than 120,000 requests for family reunification that Israeli authorities did not process.[119] An October 2005 survey, commissioned by B’Tselem, found that 17.2 percent of Palestinian residents of the West Bank and Gaza had at least one first-degree relative who was not registered in the population registry; in 78.4 percent of those cases, a family reunification request had been filed with the Israeli authorities but had not yet been processed.[120]

Israeli human rights groups petitioned the Israeli High Court of Justice to order an end to the freeze on family reunifications on the basis that it violated the right to a family. In a 2006 High Court of Justice case that dealt with a similar prohibition that froze the ability of Palestinian citizens of Israel to apply for family reunification with spouses from the OPT, the majority of judges opined that every person has the constitutional right to a family life “from the perspective of the geographic location of the family unit, which they have chosen for themselves,” but rejected the petition against the prohibition on the basis of security considerations.[121]

Based on a review of “dozens of requests involving residency in the West Bank” since Israel imposed the freeze of the population registry, the Israeli rights group B’Tselem found that Israeli authorities “refused in specific cases to delineate the threat to security if the request [for family reunification] were approved.”[122] Instead, the state attorney’s office has cited “the outbreak of hostilities in September 2000” and “the breakdown that occurred in the relationship between Israel and the Palestinian Authority” as sufficient justifications for the policy according to which “applications for family unification are not being handled by the Israeli side.”[123] However, according to the Israeli military, relations had significantly improved by June 2007, after Fatah formed an emergency Palestinian government in the West Bank in response to Hamas’s takeover of Gaza.

With the establishment of the new Palestinian government, the relations between the Civil Administration in Judea and Samaria and the local Palestinian security forces were renewed and reinforced, both in the civilian and security spheres, and working relations continue to exist for the benefit of regional development, addressing the needs of local citizens in various civilian matters and also for coordinating between the Palestinian security forces and the I.D.F.[124]

As discussed below, with the exception of a quota of family reunification requests granted between 2007 and 2008, and a quota of address change requests processed in 2011, Israel has continued to refuse to make changes to the population registry after 2007.

The state has also argued that the issue was a political matter relating to Israel’s ties with the PA, over which the court lacked jurisdiction. The state later adduced, as further support for this argument, Israel’s decision to sever all ties with the Palestinian Authority after elections in 2006 brought Hamas to power in the Palestinian government, which at that time administered parts of both the West Bank and Gaza.[125] Israel’s High Court of Justice has ruled that the Israeli military has limited authority to take political considerations into account with regard to the Palestinian population in the occupied Palestinian territory.[126]However, the High Court dismissed several petitions subsequently filed by human rights groups against the freeze by citing “the political/security situation that prevails in our region since September 2000” as a sufficient justification for the military’s policy.[127] The High Court has declined to exercise its jurisdiction in such cases without considering the question of the individual rights at stake:

It is not the practice of this court to interfere with policy that has been adopted by government with regard to the security situation and the development of relations between the Palestinian Authority and the State of Israel with respect to the return of residence or applications for family reunification that pertain to the region.[128]

Israeli rights groups continued to contest the freeze policy in court. Ido Blum, a lawyer at Hamoked, told Human Rights Watch: