Bottom of the Ladder

Exploitation and Abuse of Girl Domestic Workers in Guinea

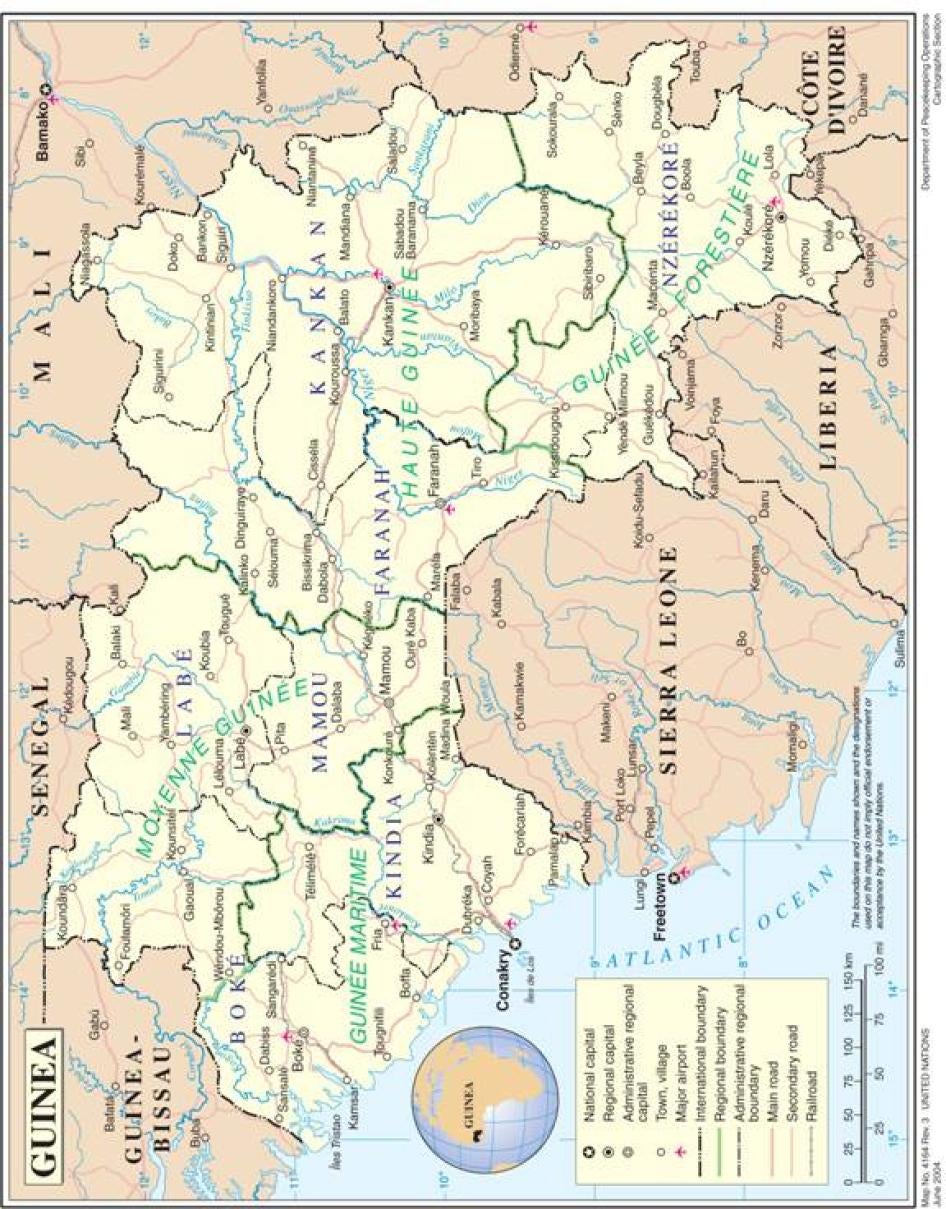

Map of Guinea

Map of Mali

Summary

I have to get up at 4a.m. and work up to 10p.m. I wash the laundry, clean the house, do the dishes, buy things at the market, and look after the children. I am told I get 15,000GNF [US$2.50] per month, but I have never seen that money.

ThrseI., age 14

Sometimes my employers beat me or insult me. When I say I am tried or sick, they beat me with a whip. When I do something wrong, they beat me too. When I take a rest, I get beaten or am given less food. I am beaten on my buttocks and on my back.

Rosalie Y., age 9

[The] husband wakes me up and rapes me. He has threatened me with a knife and said I must not tell anyone. He does it each time his wife travels. I am scared. If I told his wife, I would not know where to live.

Brigitte M., age 15

Domestic work is the largest employment category for children worldwide. In Guinea tens of thousands of girls work as child domestic workers. While other children in the family often attend school, these girls spend their childhood and adolescence doing "women's" house work, such as cleaning, washing and taking care of small children. Many of them work up to 18 hours a day. The large majority are not paid; a few others receive payments, often irregular, of usually less than US$5 a month. Many child domestic workers receive no help when they are sick and go hungry as they are excluded from family meals. They are often shunned, insulted and mocked. They may also suffer beatings, sexual harassment and rape. Despite these conditions, leaving their employer family is difficult for many child domestic workers who cannot reach their parents and have nowhere else to go. Such girls live in conditions akin to slavery.

In West Africa the recruitment of girls for domestic labor happens in a wider context of migration, gender discrimination, and poverty. Women's and girls' roles are still often limited to the role of wife and mother. Almost one-third of Guinean girls are never enrolled in primary school, and many more are pulled out during the first few years. Girls from poor rural areas in particular are often considered not worthy of education by their parents. Many parents send their daughters to live and work with families in the cities. Sending children to grow up with relativeschild fostering or confiageis a common social practice across Africa. Guinean child domestic workers often work in the house of a relative, where they have been sent by their parents at an age as young as five. Other girls from within Guinea or from neighboring countries work in the homes of strangers. Adolescent Malian girls in particular travel to Guinea for domestic work to earn money for their dowries.

If a host family treats a girl well, sends her to school and allows her to be in contact with her parents, she might have a better future than at home. As long as work does not interfere with their education, international law allows for children to carry out some light work, i.e. non-hazardous domestic tasks as part of daily chores. When adults host a girl as domestic worker, that child is dependent on them for care, and in that role they can be considered de facto, but not legal, guardians as well as employers. As primary care givers for the child at that time, they are expected to meet certain duties towards the child. Yet, many adults employing girl domestic workers do not behave like responsible guardians or employers, but instead like brutal masters. This is sometimes the case even with close relatives as well as with non-relatives. Girls' parents also often fail to check whether their daughters are treated respectfully. The exploitation of children as domestic workers is very widespread and largely socially accepted. Middle and upper class families, including government and NGO employees, often have child domestic workers in their homes and rarely consider their treatment an abuse. At the same time, it is difficult for the victims to seek redress as abuse occurs in the home and is hidden from public scrutiny. Some child domestic workers even become victims of trafficking, in so far as they are recruited, transported, and received for the purpose of exploitation, such as forced labor or practices similar to slavery.

Exploitation and abuse of child domestic workers is a violation of national and international law. The Guinean government is a party to the Convention on the Rights of the Child and all major international and regional treaties on child labor, gender discrimination, and trafficking. Under Guinean law, children have a right to education and primary school attendance is compulsory. The minimum age for employment is 16, but there is provision for children under 16 to be employed with the consent of their parents or legal guardians. Children over the age of 16 are permitted to work within certain limits, but must be afforded their full labor rights. In addition, Guinean law protects children against corporal punishment and other physical violence, sexual abuse, and trafficking. International law also provides clear prohibitions against certain harmful behavior to protect children from discrimination, physical violence, trafficking and the harmful consequences of child labor. It affords children the right to education and sets out how duties towards children should be fulfilled, whether by the state, parents, legal guardians or others in whose care a child finds himself or herself.

In recent years, the Guinean government and international actors have undertaken some promising measures to improve girls' access to education and fight child trafficking in particular, though the impact on girl domestic workers seems to be limited so far. In the context of the Education for All Fast Track Initiative, an international initiative by donors, UN agencies and developing countries, Guinea has taken steps to improve access to primary education, in particular for girls. Enrollment rates of girls have risen, but almost one-third of girls do not attend school at all. There have been few efforts specifically targeted at enrolling girl domestic workers, who have particular difficulties in accessing education.

The government has also created a special police unit, the police mondaine (vice police) to combat child prostitution, trafficking and other abuses against children. With limited resources, the police mondaine have started to seriously investigate cases and hand them over to the judiciary. However, there have been very few prosecutions so far. The judiciary suffers from serious institutional weaknesses, including lack of training and corruption. Many victims lack faith in the justice system. In practice guardians and other adults can and do commit physical and sexual abuses against girl domestic workers with complete impunity.

In June 2005, the Guinean and Malian governments signed an anti-trafficking accord and are now working on its implementation. Most activities focus on monitoring and controls at and near borders, as well as repatriation. While these activities can potentially stop trafficking, they are problematic in that they risk stopping legitimate migration and infringing on the freedom of movement of girls in particular.

Even if anti-trafficking measures were exemplary, they would not suffice to end abuses against child domestic workers. Many child domestic workers are isolated in their employers' homes and are unable to access any information or assistance from outside. They are stuck for years in abusive and traumatic situations. There is no child protection agency in Guinea to systematically monitor the well-being of children and, if necessary, facilitate their removal from abusive homes; while the Ministry of Social Affairs has responsibility for this issue, it is not operational. There is also no developed foster care system that can provide children with a monitored, protective alternative family environment. While there is a labor inspection service, it is understaffed and does not deal with the situation of child domestic workers.

Local non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and community associations do their best to fill this protection gap. With some support from international donors, they attempt to gather information about the treatment of child domestic workers, speak to their guardians about their treatment, and in the worst cases to remove them. They run shelters and small networks of foster families. These associations are a great comfort to child domestic workers and have changed the lives of many. Malian child domestic workers in particular have benefited from support within their community. Still, NGOs and community associations lack personnel, training, geographical reach and financial resources to address the magnitude of the problem, and lack the legal authority to represent the girls in their care before the courts.

In March 2007, a new national government was formed following popular protests against worsening living conditions, corruption and poor governance. According to the new prime minister, Lansana Kouyat, two priorities of the new government are strengthening the judiciary and improving the living conditions of the ordinary population, in particular the youth. The plight of girl domestic workers, in need of education, better working conditions, and protection against abuse and exploitation, fits squarely within this agenda. The Guinean government should, as a priority, establish a child protection system that allows for systematic monitoring of the well-being of children without parental care, in particular girl domestic workers and children living in the homes of persons other than their parents. It should also take measures to professionalize judicial staff, improve access to the justice system for ordinary people, and ensure that crimes against childrensuch as trafficking, exploitation, sexual and physical violencebe prosecuted. Furthermore, the new Guinean government should specifically target girl domestic workers when devising programs for access to education and apprenticeships.

Recommendations

Key recommendations to the Government of Guinea

- Set up a child protection system within the Ministry of Social Affairs that allows for systematic monitoring of children without parental care, in particular girl domestic workers and children living in the homes of legal and informal guardians. This should be established in close collaboration with international agencies and national NGOs, who are vital to implementing such a system.

- Carry out a mass public campaign and sensitization activities about the rights of child domestic workers, including the right to education, health care and labor rights, and make clear that violence against children, exploitation and trafficking are all illegal, prosecutable offences.

- In devising programs to improve access to education for girls, take specific measures for girl domestic workers. This should include dialogue with guardians and the creation of more schools that offer primary education beyond the enrollment age and provide a bridge to regular secondary school, the so-called Nafa schools, in Conakry and other urban centers

- Investigate and punish, in accordance with international standards of due process, those responsible for child trafficking, physical and sexual violence against children, and labor exploitation.

- Amend article 5 of the Labor Code and Decree 2791 on Child Labor so that the minimum age for work is set at 15.

Detailed recommendations

To the Ministry of Social Affairs, Women's Condition and Childhood

Child protection

- In conjunction with international agencies and national NGOs, set up a system for systematic child protection which is charged with:

- systematic monitoring of the well-being of children without parental care;

- dialogue with de facto guardians about their responsibilities for children in their care, and as employers, information on relevant laws on child protection and child labor, and the rights of child domestic workers;

- dialogue with de facto guardians to ensure girls are enrolled in school or allowed access to an apprenticeship, with the aim of preparing them for economic self-sufficiency in adulthood;

- intervention including removal of girl domestic workers from abusive environments and reunification with their families, if this is in the best interest of the child;

- if family reunification is not feasible or desirable, placing former child domestic workers in shelters or with foster families;

- continued monitoring of foster families and staff in shelters based on clear standards for the treatment of children, with immediate sanctions and removal of children in case of abuse;

- repatriation of children if this is in the best interest of the child;

- medical and psychological assistance for victims;

- rehabilitation of victims, including access to education or training, micro-credit schemes or other programs designed to assist social reintegration;

- legal assistance for child victims of abuse, to enable them and their families or legal representatives to bring court cases;

- referral of cases to relevant specialist institutions.

These child protection services should proactively reach out to families that host girl domestic workers. They should also be easily reachable by text messaging and a hotline.

- Take measures to implement the recommendations of the 2006 UN Secretary-General's Study on Violence Against Children on the national level, with special attention to those recommendations related to violence against children in the work place and in the home.

Trafficking

- Implement the 2005 Mali-Guinea Anti-Trafficking Accord, in particular, provisions regarding the identification of trafficking cases; the prosecution of traffickers; and voluntary repatriation and rehabilitation of trafficking victims.

- Ensure that anti-trafficking measures differentiate between trafficking and legitimate migration and do not restrict rights to freedom of movement.

- Ensure that child protection committees, which are being set up by the government with UNICEF support, have a broad child protection mandate and understand the difference between stopping trafficking and ensuring safe migration.

- Take measures to make migration safe within Guinea and in the region through dialogue with and regulation of intermediaries and transport agents that assist travel.

To the Ministry of National Education and Scientific Research

- In devising programs to improve access to education for girls, take specific measures to improve primary and secondary school enrollment in quality schools for girl domestic workers, including non-Guinean nationals. In particular, start a program of sensitization and dialogue with host families of child domestic workers to encourage school attendance. If necessary, start with pilot schemes in some areas. Increase the number of non-formal Nafa schools in Conakry and other urban centers. Use stipends and other incentives, such as free school meal programs, to encourage school attendance of girls, including child domestic workers.

- Design a program to monitor school attendance of girls, in particular girl domestic workers, and encourage drop-outs to re-enroll.

- Take specific measures to ensure that girl domestic workers can access vocational training and apprenticeships with a wide range of professional options.

- Carry out market and employment analysis in order to ensure that vocational training programs and apprenticeships are based on local needs.

To the Ministry of Labor, Public Service and Administrative Reform

- Take steps to eliminate child domestic labor under the age of 15. Enforce existing protections against child labor, including existing protections against carrying heavy loads and other hazardous types of work.

- Develop a list of forms of work that pose a high risk of being hazardous to children with technical support from International Labor Organization, and amend labor laws and the Decree on Child Labor accordingly.

- Develop a time-bound action plan, in view of eliminating the worst forms of child labor by 2016, in line with the recommendations of the ILO Africa Regional Meeting in April 2007.

- Create the position of Child Labor Inspector within the Ministry of Labor, and provide them with the means to carry out country-wide monitoring over the use of child labor, with a focus on eliminating all hazardous work for child domestic workers, including for those over the age of 15.

- Inform girl and women domestic workers about their right to seek redress for labor exploitation at labor tribunals.

To the Ministry of Justice

- In conjunction with other parts of the government and international police and legal experts, take steps to professionalize judicial staff, and curb corruption in the judiciary.

- Take steps to facilitate access to the justice system for ordinary people, including girl domestic workers and former girl domestic workers. Specifically:

- allow NGOs to intervene as parties (parties civiles) to a court case;

- train investigators and judges in techniques to investigate trafficking, sexual, physical and other violence against children;

- train labor tribunal officials in techniques to investigate labor exploitation of minors, in particular child domestic workers;

- train all judicial officials to understand the specific needs of child victims, in order to avoid re-traumatization during legal proceedings;

- ensure that court cases involving children can be heard in camera (non-public) where the best interests of the child and the interests of justice require;

- provide victims of child abuse and their families with appropriate information about each step of their court cases, so that they have access to the process and their interests are protected. Designate case workers within the judicial system who are in regular contact with the victim and her family;

- cooperate with national NGOs to improve access to justice.

- Investigate and punish in accordance with international standards of due process, those responsible for child trafficking, physical and sexual violence against children, and labor exploitation. Take measures to accelerate pending cases of alleged trafficking and child abuse.

- Disseminate public information about any successful prosecution and punishment of trafficking, labor exploitation, sexual violence and child abuse in Guinean courts.

To the Ministries of Social Affairs, Justice and Human Rights, Labor and Health

- Jointly devise and carry out a mass public campaign and sensitization activities with specialized audiences, in particular educators, labor inspectors, police and justice officials about the rights of child domestic workers, including the right to education, health care and labor rights. Make clear that violence against children, exploitation and trafficking are all illegal, prosecutable offences.

- Carry out sensitization activities on prohibited forms of child labor, including the worst forms of child labor. This should include information about the hazardous nature of carrying heavy water containers.

- Develop a program to inform girl domestic workers about their sexual and reproductive rights, and about HIV/AIDS prevention, including information about the correct and consistent use of condoms.

To the National Assembly

- Amend article 5 of the Labor Code and Decree 2791 on Child Labor so that the minimum age for work is set at 15. In particular, abolish the clauses that allow child labor for children if parents or guardians consent to it.

- Adopt the Child Code, which would provide comprehensive protections for children and allow NGOs to intervene as parties (partie civile) to a court case.

- Adopt implementing legislation for the protection and enforcement of children's rights as set out in international human rights treaties to which Guinea is a party.

To Guinean NGOs, youth associations and trade unions

- Advocate for the rights of child domestic workers and encourage girl domestic workers to organize and develop their own associations for the purposes of mutual support and advocacy.

- Set up programs of legal assistance to girl domestic workers, including for cases at labor tribunals.

To the Government of Mali

- Implement the 2005 Mali-Guinea Anti-Trafficking Accord, in particular, provisions regarding the identification of trafficking cases; the prosecution of traffickers; and voluntary repatriation and rehabilitation of trafficking victims.

- Ensure that anti-trafficking measures differentiate between trafficking and legitimate migration and do not restrict rights to freedom of movement.

- Take measures to make migration safe within Mali and in the region, including through dialogue with and regulation of intermediaries and transport agents that assist travel.

- Broaden the mandate of surveillance committees to address child protection issues in general, and ensure that committee members understand the difference between stopping trafficking and ensuring safe migration.

To all members states of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS)

- Implement the 2006 ECOWAS Plan of Action Against Trafficking in Persons, in particular, provisions regarding the prosecution of trafficking, and assistance for victims of trafficking.

To the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF)

- Provide technical and financial assistance to relevant Guinean government ministries and to national NGOs to carry out activities to monitor, assist and support girl domestic workers, as described above. This should include:

- support in setting up a child protection system;

- programs to improve access to school for girl domestic workers, including an increase of Nafa schools in Conakry and other urban centers;

- programs to improve access to the courts and labor tribunals for women and child victims, including girl domestic workers;

- programs to inform girl domestic workers about their sexual and reproductive rights, and about HIV/AIDS prevention, including information about the correct and consistent use of condoms.

- Help the government identify best practices for employment and treatment of girl domestic workers above 16, in Guinea or the region.

- Provide technical and financial assistance to the Malian and Guinean governments in implementing the 2005 Mali-Guinea Anti-Trafficking Accord.

- Ensure that anti-trafficking measures differentiate between trafficking and legitimate migration and do not restrict rights to freedom of movement. In particular, ensure that child protection committees, which are being set up by the government with UNICEF support, have a broad child protection mandate and understand the difference between stopping trafficking and ensuring safe migration; and take measures to make migration safe within Guinea and in the region, including through dialogue with and regulation of intermediaries and transport agents that assist travel.

To the International Organization for Migration (IOM)

- Provide technical and financial assistance to the Malian and Guinean governments in implementing the 2005 Mali-Guinea Anti-Trafficking Accord.

- Ensure that anti-trafficking measures differentiate between trafficking and legitimate migration and do not restrict rights to freedom of movement. In particular, take measures to make migration safe within Guinea and in the region, including through dialogue and contact with intermediaries and transport agents that assist travel.

To the International Labor Organization (ILO)

- Provide technical assistance to the National Assembly for amendments of the Labor Code and the Decree on Child Labor.

- Provide technical and financial assistance to the Ministry of Labor, in particular in creating Child Labor Inspector positions, and in elaborating a hazardous labor list.

- Provide technical and financial assistance for sensitization activities around the concepts of light work, child labor, and hazardous labor.

- Provide technical and financial assistance in developing a time-bound action plan for the elimination of the worst forms of child labor by 2016, as recommended by the ILO Africa Regional Meeting in April 2007.

- Provide legal advice to girl and women domestic workers seeking redress at labor tribunals for labor exploitation.

To the UN General Assembly

- Recommend the establishment of the position of UN Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Violence Against Children, in order to facilitate the implementation of the recommendations of the 2006 UN Secretary-General's Study on Violence Against Children.

- Recommend that the implementation of the study's recommendations be carried out with a strong gender analysis, and coordinated with activities initiated by the UN Secretary-General's In-depth Study on All Forms of Violence Against Women.

To donor countries, such as the European Union (EU) and its member states, and the United States (US)

- Provide technical and financial assistance to relevant Guinean government ministries and to national NGOs to carry out activities to assist and support girl domestic workers, as described above. This should include:

- support in setting up a child protection system;

- support for programs that aim to improve access to school for girl domestic workers.

- Provide technical and financial assistance to the Guinean government to professionalize judicial staff, curb corruption in the judiciary, and remove obstacles to the independence of the justice system. Fund government and NGO programs to improve access to the justice system for women and child victims, including girl domestic workers, and to support services such as shelter, legal aid, and health care.

Methodology and Terminology

Field research for this report was carried out during December 2006 and February 2007, in Conakry, the capital of Guinea, and two other locations of Lower Guinea, Forcariah and Kilomtre Trente-Six.

Human Rights Watch researchers planned the research in consultation with a range of national NGOs working in the area of child labor and exploitation. Three associations helped us make contact with girl domestic workers: Action Against Exploitation of Women and Children (Action Contre l'Exploitation des Enfants et des Femmes, ACEEF), Guinean Association of Social Assistants (Association Guinenne des Assistantes Sociales, AGUIAS) and High Council of Malians (Haut Conseil des Maliens). In addition, the international agency Population Services International (PSI) put us in touch with sex workers, two of whom had previously worked as child domestic workers.

A total of 40 girl domestic workers and former girl domestic workers were identified and interviewed. We attempted to get interviewees of different ages, in urban and rural areas, living with relatives or strangers, and in different current life circumstances. However, some girls did not know their precise age because they had no birth registration. They gave the age they were told they had, but this could have been inaccurate. Also, it proved harder to reach out to young girls, as they often have less opportunity to leave the house and establish contact with the outside world. Thirty-three of the 40 interviewees were children at the time of the interview, between the ages of 8 and 17.[1] Local NGO staff translated interviews from Malinke, Sousou or Peulh into French; they also helped carry out some of the interviews.

In addition, we interviewed four parents of girl domestic workers, two guardians of domestic workers, a deputy head teacher, a medical doctor, members of the Malian community in Guinea, national and international NGOs, UNICEF, ILO and diplomatic staff in Guinea. From the government, Human Rights Watch interviewed the then Minister of Social Affairs, Women's Promotion and Childhood,[2] as well as several officials in her Ministry; officials in the Ministry of Education; officials from the Ministry of Justice; and a police commissioner dealing with crimes against children.

Consultation with national NGOs was also instrumental in developing the report's recommendations.

Methodological challenges

Research into abuses against children, and in particular sexual violence against girls, is highly sensitive. Victims often feel ashamed about what happened to them or that their guardian will find out about their testimony. Furthermore, talking about their experiences might re-traumatize them.[3]

The length and content of the interviews was adapted to the age of the girl. Interviews with girls under ten did not last longer than 15 minutes, while those with older girls could take up to an hour. When girls needed immediate assistance, for example, because of continued experiences of rape by a guardian, local NGOs were informed and took action.

Thirty-six interviews were translated by locals who were known to the interviewee. We attempted to have a female interviewer and a female translator. However, this was not always possible. Thirty-one interviews were done by a female researcher and nine by male researchers. Several interviews were done with male translators.

Interviews were carried out in a quiet setting and the names of the interviewees kept confidential; all names used in this report for child domestic workers are pseudonyms, unless marked otherwise.

As the research took place during a period of political upheaval in Guinea, travel to Upper Guinea had to be cancelled. This study is therefore focused on the situation of girl domestic workers in the coastal region, commonly known as Lower Guinea.

Terminology

This report uses the words child domestic worker and girl domestic worker to describe the girls who are the subject of the research. The term child domestic worker is more commonly used but obscures the fact that almost all child domestic workers in Guinea are girls.

In general, we call the persons who recruit girls for domestic service intermediaries or recruiters. We only use the word trafficker when referring to persons that are involved in the crime of trafficking.

In order to describe the adults for whom the girl is working, the report uses the term host, guardian, or employer. These terms are quite different and point to the different roles and responsibilities such adults have. We also use the French word for guardian, tutrice (female) and tuteur (male), used by domestic workers themselves. The choice of these terms reflects that fact that adults who have girl domestic workers in their house have legal duties both as de facto guardians and as employers.[4]

I. The Context: Girl Childhood and Migration in West Africa

Poverty and economic crisis

West Africa is one of the poorest regions of the world and includes all five of the world's poorest five countries. The Human Development Index ranks 177 countries, with 177 being the lowest position. Mali is ranked 175th, and Guinea is 160th.[5] The whole region is economically dependent on a few export products.[6] While most countries in the region are endowed with vast natural resources, governments of West Africa have largely failed to use their mineral wealth to improve the lives of their citizens.

Within West Africa, Guinea in particular is replete with natural riches, including bauxite, iron, diamonds and gold. However ordinary Guineans appear to reap little benefit from this wealth. Indeed most of these are mined by foreign companies from Russia, Canada, and the United States among others.[7] The government has failed to use Guinea's vast mineral wealth to improve the lives of ordinary Guineans. The economic situation has been particularly difficult over the last five years. The rule of President Lansana Cont who came to power in a military coup in 1984, has been characterized by repression, corruption and poor governance. The International Monetary Fund (IMF), in 2000, offered to drop US$545 million of Guinea's debt under its Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative, but so far the country has not met IMF criteria regarding financial management and transparency.[8] Transparency International, in 2006, ranked Guinea 160 out of 163 countries, making it the country that is perceived to be most corrupt in Africa.[9]

Guinea's social indicators now resemble that of a country ravaged by war even though Guinea has not experienced any major armed conflict.[10] Economic growth, which averaged about 4.5 percent in the 1990s, has slowed since 2000 to an average rate of about 2.5 percent a year.[11]In late 2006, inflation was around 30 percent.[12]Basic commodities such as rice and fuel have become more and more expensive,[13] leading to popular protests in June 2006 and in early 2007.[14]The consequences of the economic crisis for education[15] and health[16] have been disastrous. The mortality rate of children under five is 163 deaths per 1000 live births.[17]

Gender roles and unequal access to education

In West Africa most girls are raised to become hard-working mothers and wives. At an early age, girls often start to learn basic tasks in the household and take responsibility for preparing food, fetching water, selling goods at the market, or raising smaller children. An estimated 85 percent of child domestic workers in Africa are girls.[18] Across the region, it is considered normal for children to work; a child's work is seen as his or her contribution to the family, and many children adopt this view. Typical work for children includes household work, agricultural work, or selling goods on the street. Such work often provides a vital economic contribution to a family's survival, but it may also prevent parents from sending their children, particularly girls, to school, and burden them with hard work.[19] In Guinea, estimates place the percentage of working children at 73, and 61 percent of them in domestic service.[20]

Far fewer girls than boys attend school in Guinea and the whole sub-region. Between 2000 and 2005, 29 percent of girls in Guinea were not enrolled in primary school, whereas only 13 percent of boys were not attending primary school. The difference between boys and girls was even starker at secondary school, where half as many girls as boys are enrolled.[21] This situation is similar across West Africa.[22]

Whenever families experience financial or social problems, girls are more likely to be pulled out of school than boys. This has become particularly problematic in the context of the AIDS epidemic, as girls are more likely to stop their education to care for sick parents.[23]

More than 50 percent of girls in Guinea are married before their 18th birthday. Many of these marriages are arranged without the consent of the girl. In addition, pregnancies which result at such an early age are often associated with health problems which cause higher rates of maternal and infant mortality.[24]

The low social status of women and girls in Guinea is reflected in high levels of violence. Women and girls are frequently victims of domestic and sexual violence, including in schools.[25] In 1999, a survey in Guinea put as high as 98.6 the calculated percent of women and girls who had undergone a procedure of female genital mutilation.[26] While illegal, the practice is firmly rooted in Guinean culture, and a girl without excision might have difficulty finding a husband. In the last eight years, the government and a local NGO have started to campaign against female genital mutilation, and some families now oppose it, or opt for a symbolic incision of the genitals.[27]

Migration and trafficking in West Africa

Migration

There is a long history of economic and labor migration in West Africa. Already in pre-colonial times West Africa had long-distance trade routes. Some of the patterns of labor migration that emerged during the colonial period are still of relevance today, such as the migration of agricultural laborers from Mali and Burkina Faso to Cte d'Ivoire.[28] Consequently, networks that assist relocation from one place to another are strong. Labor migration has also shaped Guinea's past and present. Migrants come from Mali and other neighboring countries to the Guinean capital and mining areas, for example, in Mandiana and Siguiri in Upper Guinea and Fria and Boke in Lower Guinea. At the same time there has also been a flow of Guineans migrating elsewhere. Many Guineans migrated to Senegal and to Cte d'Ivoire during the colonial period and up to today. Furthermore, there has been significant rural-urban migration within Guinea.[29]

Migration of children, in particular, has a long tradition. Younger children have often been sent to live with relatives in the context of traditional child-fostering practices.[30] For adolescents, leaving the village and seeking economic independence has been an important rite of passage both in the past and present.[31]

Migration in West Africa has often been helped by the presence of similar ethnic groups across national borders. For example, the Bambara in Mali and the Malinke in Guinea are historically one group, and they speak the same language.

Trafficking

While migration for jobs, education, or foster care is important, it can also lead to situations of exploitation and trafficking.Under international law, child trafficking consists of two elements: (1) the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring or receipt of the child; and (2) the purpose of exploiting the child. Exploitation can mean sexual exploitation; forced labor or services; slavery or practices similar to slavery or servitude.[32]

Trafficking of children for labor has increasingly become a problem in West Africa. Within the region, children are trafficked for domestic labor, agricultural labor, market labor and street selling and begging. Some children are also trafficked for prostitution and sexual exploitation. Most of the trafficking is done through small, informal networks, including families and acquaintances, that might not even operate on a continuous basis. In addition, children are trafficked to the Middle East and Europe from some countries, in particular Nigeria.[33] Important trafficking routes in West Africa are from Benin and Togo to Gabon in Central Africa, and from Burkina Faso and Mali to Cte d'Ivoire.[34] Many children are also trafficked from neighboring countries into Nigeria.[35] In Guinea, in addition to internal trafficking, there has been cross-border trafficking between Mali, Sierra Leone, Liberia and Cte d'Ivoire,although the exact scale of the problem is difficult to determine.[36] In recent years, there have been significant efforts to combat trafficking in West Africa, though these efforts might have sometimes stopped the migration of young people. Another problem is that trafficking victims, returned to their homes, have not stayed there either, but have often left again in search of work.[37]

II. Recruitment into Domestic Work

Girls enter domestic work in a variety of ways. Though the explicit aim of the placement process is not always to use the girl for household work, in reality, they almost always end up doing domestic work. Many girl domestic workers experience labor exploitation as well as child abuse and neglect. Recruiters and employers are primarily responsible for this, but parents also neglect their duty to care for their child and monitor his or her well-being, even from a distance. Finally, the government fails to prosecute crimes against children and guarantee that their rights be fulfilled.

Recruitment of girls from Guinea

In West Africa, children are often raised by close (uncle, aunt, grandparents) or distant extended-family relatives; this tradition is sometimes called child fostering, or in Francophone West Africa, placement or confiage.[38] While many such placements are done with relatives, parents also send their children to live with non-relatives, such as friends, godparents, acquaintances, or even complete strangers. Seventeen of the 32 Guinean girls interviewed indicated that they had been sent to their direct aunts and uncles. One had been sent to a cousin. The other 14 host families were not relatives.

Motives of parents

Frequently, parents send their children to live with relatives when these relations live in a larger city. Parents in the rural areas often consider life in the city as easier, filled with more opportunities, even when their relatives in the city are poor. In particular, parents often hope that their children will get an education or vocational training in the city and hence get a good job later.[39] Indeed, general standards of health, nutrition and education are much lower in the rural areas than in the urban areas.[40] Many families have large numbers of children and find it impossible to adequately feed them all; this problem is accentuated by polygamy and limited access to family planning, which means that one man has several wives and even more children to provide for. One father explained:

I have three wives and many children. I sent one of my daughters to live with my younger sister. She is in Tamagali, in the prefecture of Mamou. The girl is 11 years old. I sent her at the age of five. I sent her because I have many kids, and my sister offered to help me by taking one of my children.[41]

However, poverty and underdevelopment are not the only factors at play. There is also a strong bias against girls' education and independence in the rural areas, which serves to "track" girls into the path of domestic labor. Girls are expected to perform domestic work and then marry at a young age. Sending girls away to do domestic labor becomes one of few "career paths" available.[42]Parents sometimes "offer" their child as a helper in a relative's house or when they are requested to do so. For example, they may do so when their relatives do not have a child, almost as a way of "adjust[ing] the demographic imbalance."[43]

More specifically, parents send girls to do domestic work when the relative does not have a daughter, as illustrated by the case of eight-year-old Mahawa B. from Forcariah who was sent to her uncle and aunt's village in the same prefecture. She told us, "My uncle asked my mother to send a daughter. He does not have any daughters. My father has many children."[44] Mahawa was then sent to her uncle to do domestic work and agricultural labor on the family's plantation. Both her parents and her uncle and aunt considered it normal that such work is done by a girl. Her three brothers were going to school; she and her sisters did not. By sending Mahawa to her relatives, her parents prioritized her work over her education, something that frequently happens to girls in Guinea.

Relatives also frequently asked for a girl to be sent when a baby was born, so that she could help rear the child. At the age of five or six, Dora T. moved from Norassaba in Upper Guinea to Conakry, a distance of 500 kilometers:

A woman [Dora's aunt] came looking for me; she wanted me to take care of her child. She promised that afterwards I would go to school or do an apprenticeship. But since I am there, the child has grown up, goes to school now, but not me. Up to now, it is me who does everything in the house. My parents sent me here because the woman made the promise. My father is now very unhappy about the situation. When we arrived in Conakry, I cleaned the house, washed the clothes of the children, got the nursery child ready for nursery and stayed with the baby at home. Now that I am older, things are worse. Before I could not do everything, I was too small [five or six years old]. Now, I do everything in the household, I do hard work at home. Initially I was in contact with my father. But since the last time when he came, he has not been in contact again, because he was angry [with his sister]. Once he came to get me and take me back to the village. But she pretended that she was already used to me, that she really loved me, she cannot stay without me. So she promised that now, she would put me into school. That was about three or four years ago.[45]

In still other cases, parents send their children to stay with relatives because there is a crisis in the family, such as divorce or illness.[46] When parents divorce, children either with stay their mother, or their father sends them to a female relative, typically his sister.[47] In this case, relatives are seen as doing a favor to the parents, and "helping out" by taking in a child. Children were also sent to live with other families in the case of divorce. This happened to Justine K., who was sent to her aunt:

I came to Conakry as a young child after my parents divorced.My father sent me here from Kankan and gave me to my aunt.I have three other siblings, and they were all sent to other family members. Both my parents now live in Conakry, but my mom remarried, and I don't see her anymore. My father didn't remarry. At my aunt's house, I was responsible for all household work, and I wasn't paid.My aunt would beat me when she thought I hadn't done something. Sometimes it was with a piece of wood, and other times with a broom.[48]

After being abandoned by her husband, Aminata Y. from the village of Madina in Forcariah prefecture sent her five-year-old daughter Rosalie to live with a family friend. She has seven children and found she was unable to care for them all. The friend who lived nearby had offered to help her. However, she made Rosalie work so hard that four years later, her mother took her back. She explained, "My friend was mean with the girl."[49]

The illness of a parent is yet another factor which leads to child fostering. When parents become very ill and realize they might die, they often send their children to stay with relatives. There are an estimated 370,000 orphans in Guinea, about 8 percent of all children. These children include about 28,000 AIDS orphans.[50] This large number of orphans poses challenges for traditional systems of child fostering, as families may end up with more children than they can care for. Of the 32 Guinean girls interviewed by Human Rights Watch for this report, four were orphans and nine had lost one parent.[51] Two others had mothers that were permanently ill. Fourteen-year-old Fanta T. is among the orphans we interviewed; she told us:

My mother died of diabetes. My father died too. My mother sold pepper on the market; my father was a car cleaner. When my mother fell sick, she sent me to stay with my father's younger brother. I was eight years old then. I cleaned the house, did the dishes, went to the market, cooked, and looked after the children.[52]

Brigitte M.'s mother died when armed groups from Sierra Leone attacked the border town Pamelap. Brigitte lived with her father who slid into a state of misery as his other children left, and one son died. She recounted how her father decided to send her off with a complete stranger:

One day a woman came to the weekly market nearby. I was at the market too. I had hurt myself on the foot, and I cried from pain. The woman found me and consoled me, and suggested to my father that she could look after me and send me to school. He agreed. So I went with her. I was about eight years old. I have not been in contact with my father since. I don't know if he is still alive.[53]

As this case indicates, sometimes girls were sent to live with people unknown to the parents; in other cases girls were sent to family friends or powerful patrons.[54] At the age of 13, Anglique S. was sent by her family to live with their landlords, in a relationship that was reminiscent of feudal times. Her parents and older siblings are agricultural laborers on a plot of land; the owners do not pay them a salary but allow them to live there and keep enough rice and salt from the land for their own consumption.[55] She told us about her sister's and her own experience of being pressured to do domestic work without pay:

The people where I do domestic work own a plantation in our village. My parents work on this plantation, and guard it in their absence. My older sister went with these people to Conakry and did domestic work for them. She found them mean and left. She was then placed with the daughter of the lady, to look after her baby twins. She was often beaten and insulted. Finally, our brother went there and took her back home. Then they asked my mother to send me. But I did not want that because my older sister already had a bad experience. So I was sent to the mother instead. But she had the same bad attitude. My mother told me that I would have to stay there until God helped me.[56]

According to her brother, the family was happy to send Anglique to Conakry because "there are no options here for her, here is nothing, neither school nor jobthe only thing she can do here is find a husband."[57] He also explained that the owner's wife is Anglique's namesake, which he considered to be like a godparent. According to the brother, "We knew that one day they would take [Anglique] to Conakry." Although they promised that they would send the girl to school, this has not happened. However, Anglique has recently found an apprenticeship in tailoring, through the help of a local organization working with child domestic workers, Action Against Exploitation of Women and Children (Action Contre l'Exploitation des Enfants et des Femmes, ACEEF).

Motives of girls

Most girls are sent to host families at such a young age that they do not express any desire or make the choice to go themselves. Rather, it is likely that many of these younger children suffer from the sudden separation from their parents and other close relatives. However, some girls interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they were keen to seek out such work opportunities. They often felt that they should do so to contribute to their family's low income. For example, ThrseI. left her family at the age of 12 in Boke to earn money in Conakry:

A woman came and was looking for a domestic for her sister. The woman was a stranger to me. My mother did not want me to go but I wanted to earn money. So I came together with the sister to Conakry. I would like to leave, but my mother is not in Boke any more. She has gone to Guinea-Bissau. And I don't know where she is.[58]

Some adolescent girls also seek positions as domestic workers of their own volition. Francine B. from Conakry decided at the age of 16 to seek work because she was an orphan and had only limited support at the house of her sister, where she lived. Through an acquaintance of her brother, she found a Lebanese-Guinean couple who employed her as a nanny.[59]

Recruitment methods

When parents sent their daughter to stay with a relative, contact was easily made. When girls were not placed with direct relatives, contact with the host family often occurred through connections in the village or area. For example, parents sometimes placed girls with neighbors or people living nearby. When the host family moved away, the girl went with them. Parents also frequently sent their daughters to live with families from the same ethnic group or even village, and with whom they felt a connection even if there was no family relation or prior contact. Thirteen-year-old Sylvie S. from Kindia prefecture explained how this worked for her:

When I was small, a woman came to the village and asked for a child to be placed with a family in Conakry. I am not related to her. She was an acquaintance of a relative. I was placed in the family. The husband is a mason. There are no other children in this family. First when I came I did small things. I cooked and cleaned. Now I work a lot and I am not paid.[60]

Other girls were recruited by women recruiters who visited their villages and negotiated a girl's placement and terms with her parents. In some cases, the girls then worked for these women. In other cases, the women recruiters acted as intermediaries for a relative or friend who was seeking a child domestic worker. Georgette M. from Lola in the Forest Region of Guinea remembered:

I came two years ago. The tutrice is a teacher. My mother gave me to the woman. They are not part of the family. The woman's younger sister had come to Lola to find a domestic worker, and she took me back with her to Conakry. The mother of the lady [tutrice] is from Lola as well. My parents are farmers. I am not sure why my mom sent me here. Sometimes my mum writes to me. My tutrice buys things and sends them to my parents. For example she sends shoes or clothes. She does that every month and explains that herself to me. She has never given me a salary.[61]

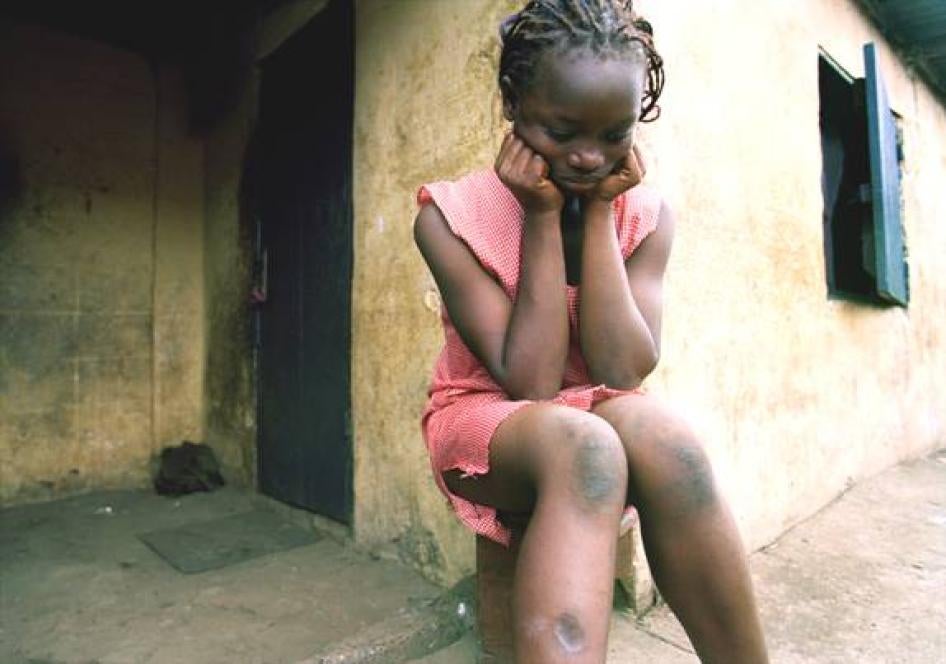

Girl domestic worker in Conakry. 2007 Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos

In Conakry, several women act as recruiters. They place girls from their home region with families in the capital. Girls may arrive in Conakry and go to such a woman on their own initiative and stay there until they find a placement.[62] A representative of the Ministry of Social Affairs observed:

It is easy to become an intermediary. You just place five girls from your village and that makes you an intermediary.[63]

In Middle and Upper Guinea, local NGOs have also reported the presence of intermediaries who send larger numbers of children into domestic service.[64]

The tutrices

Employers are mostly women from the urban middle classes. They tend to demand a girl from their poorer relatives in the countryside, or send intermediaries to find a girl in the home village or in Conakry.[65] Ironically, increased levels of education and employment among middle class urban women in Guinea and other parts of West Africa have led to a higher demand for domestic workers.[66] Nowadays, many African women in the city have a job and want cheap help at home to look after their children and the household. Rather than employing adults who are more likely to demand a salary, they use girl domestic workers. However, some host families are also poor and live in rural areas, particularly when the arrangement happens within the family.

Recruitment of girls from Mali

Across West Africa, girls have increasingly tried to leave their villages and seek work elsewhere. Adolescent girls from Mali sometimes work in neighboring countries, including Guinea, Cte d'Ivoire, and Senegal. In Mali and other Sahel countries, the coastal regions are considered wealthier and have therefore become popular destinations. Migrant girls usually work for employers with whom they have no family relation. Migration has given these girls the opportunity to experience urban life, learn new languages, and accumulate their own possessions. Girls in particular have often traveled to accumulate goods for their dowry.[67] This type of migration by adolescents is generally more self-directed by the child than confiage, even though some parents might give their consent to their child's departure, or even be involved in the process of organizing travel and work. For example, many children and young adults migrate from Burkina Faso, Mali, and other countries in the region to work in the cacao plantations of Cte d'Ivoire, even though the war and climate of xenophobia against people from the north have reduced the migration flow.[68]

Motives of girls

Malian girls often migrate to the capital Bamako, but also to neighboring countries including Guinea to assemble their dowry (trousseau de marriage). The dowry often consists of kitchen utensils, clothes and jewelry, which is, upon her engagement, given to the family of the future husband. This is not a new phenomenon, but the number of girls migrating seems to have risen, and girls are now migrating further away. Studies in Mali and Burkina Faso have shown that peer pressure to assemble precious and original items for the dowry has risen tremendously throughout the region.[69] As girls have traveled afar and come back with new items for their dowry, others have felt the need to do so too. After a period of work they return and get married.[70]

However, not all girls leave to get their dowries. Some girls leave simply because they want a degree of independence, and they want to obtain material possessions, such as clothes and bicycles. Others might leave for the dowry, but end up rejecting the husband proposed to them, and seek greater independence. This is what happened to Carine T. when she left Bamako:

A woman called Fatoumata told me she could help me to come to Conakry. [At that time] I worked as child domestic worker for a woman [in Bamako]. I was 15 years old then. She was the friend of Fatoumata's. Fatoumata is a trader and sometimes stayed with this woman when visiting Bamako. So I went to Conakry with the help of Fatoumata. Fatoumata placed me with a family of a customs official. The woman for whom I worked said she would pay my transport if I stayed for two years. If you do not stay for two years we will have to subtract this from your salary. I worked there for two years. The woman paid money to Fatoumata. Fatoumata took 20,000CFA [about US$27] off it for transport. I was not paid directly. The woman gathered it all up and gave it to Fatoumata at the end. She gave me the rest, 880,000CFA [about $1200]. After the two years, I bought fabric with the money and returned to Slingu. But I did not stay for a long time because I was supposed to get married to a man who I did not want to marry. My father chased me away. So I went back to Conakry.[71]

Several other girls had initially gone to Bamako for domestic work and then met women who told them that they could earn more money in Conakry. Seventeen-year-old Florienne C. recounted her experience:

I met a woman called Agios, a Guinean living in Bamako. She told me she could get me a job for 25,000 Francs [Guinean Francs, GNF, about $4.16] a month. So I traveled with her and three other girls to Conakry. This was in 2002 and I was 12 years old. When I arrived here, I was sent to work in Madina [a neighborhood of Conakry].[72]

Malian child domestic workers in Conakry have come from different areas, but in recent years, a large number of girls have come from the Sikasso area in southern Mali, in particular Selingu.[73] The departure of many girls from Selingu is partly explained by its proximity to the Guinean-Malian border. But it might also be explained through peer pressure and peer influencing. As more girls leave the village and later return with money, dowry prices rise, and other girls are motivated to leave.[74]

Methods of recruitment

According to Human Rights Watch interviews with victims, Malian girls are often recruited by female Guinean or Malian intermediaries in Bamako who convince them that if they work in Conakry, they will earn more and lead a better life than they do in Mali. The actions of some of these women might amount to trafficking, when they make false promises, place the girls knowingly with exploitative and abusive employers and keep some of the girls' money.

According to members of the Malian community, girls are frequently recruited in the Oulofoulogou and Medina Corah neighborhoods of Bamako. Several womenMalians and Guineansare well-known in the community for their role as intermediaries between Malian girls and Guinean tutrices.[75] The girls are frequently sent in groups to Conakry. According to Carine T.:

Fatoumata [pseudonym] sends many girls. She is based in Siguiri. She takes goods from there and sends them to Bamako. She recruits through some girls' friends she has in Bamako. She tells her friends she is looking for girls. The friends go from door to door, and some parents accept to send their daughters. Afterwards she goes into the streets and approach groups of girls. When she comes back to Conakry she takes back girls with her, from the train station. Then she distributes them to families.[76]

Two girls, Vivienne T. and Mariame C., told us that they were approached by a woman who got them interested by saying that they could earn a lot of money in Conakry. She frequently sent girls from Bamako to Guinea, and worked with a driver who took the girls there. Vivienne was 16 and Mariame was 14 years old when they were recruited by the woman in Bamako.[77]

A list[78] of seven Malian domestic workers in Conakry who arrived between September 2002 and November 2003 identified two women intermediaries who had sent these girls. According to a member of the Malian community, these women were well-known for their activities.[79]

However, in recent years, some intermediaries seem to have either reduced their activities, or they are operating more clandestinely.They tend to operate from Guinea rather than Mali, apparently because the Malian government scrutinizes their activities. One woman has allegedly reduced her work due to pressure from the Malian community in Guinea; another one has allegedly gone underground.[80]

The tutrices

Most families employing Malian girls are based in Conakry, and belong to the urban middle classes. Our research found cases of Malian girls working for a judge,[81] a border official, a pharmacist, a taxi driver and a businessman.[82] According to a Malian living in Conakry, Malian girls are considered more reliable and "controllable" than Guinean child domestic workers.[83]

Recruitment of refugee children from the region

In addition to the patterns of migration mentioned above, many children have crossed borders to escape violence or war. As a result of armed conflicts in neighboring Liberia and Sierra Leone, Guinea has hosted hundreds of thousands of refugees within its borders during the past decade. At the height of the crisis, more than half a million refugees lived within its borders.[84] As the situation in those countries has stabilized, most of the refugees have returned; but others, including those who came as children, have stayed and found employment in Guinea. In recent years, refugees from Cte d'Ivoire have also sought protection in Guinea. At present, there are about 30,000 refugees in Guinea, according to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).[85] Refugee children are in a vulnerable situation, particularly when they are separated from their parents. Many refugee children have become victims of labor exploitation, including as domestic workers.[86] For example, Julie M. from Sierra Leone was sent by her mother to Conakry when she was about seven years old, so she would escape the consequences of armed conflict in her home country. Her mother placed her with an acquaintance, where the girl worked as child domestic worker.[87] Eight-year-old Jacqueline C. is from Cte d'Ivoire and fled the war there with her mother and siblings. She was taken in by a well-meaning Guinean woman who explained that she and others took in individual members of refugee families. While Jacqueline C. is going to school, she is also spending most of her time doing domestic work.[88]

Risks connected to travel

Guinean and Malian girls face risks when they travel to seek work. They often travel with persons whom they don't know very well, but upon whom they are dependent during the duration of the trip. When 16-year-old Marianne N. left Conakry for Monrovia by bus, she was supposed to meet the brother of her neighbor, who would help her find work. But he did not turn up and she was stranded:

My neighbor thought her brother could help me find work. She took me to the bus station and called the brother. But when I arrived in Monrovia I did not find the brother. So the bus driver found a friend who hosted me. I stayed with him and he forced me to have sex with him. He told me otherwise he would kick me out.[89]

Susanne K. traveled by herself to Conakry after her parents died. She found herself in an equally vulnerable position:

I am from Kolifora near Bofa, in Lower Guinea. I am told I am about 14 years old. My dad was an Arabic teacher at a Koranic school and my mum a street seller. My dad died of something that caused pain in the belly, and my mother died shortly after. I left the village after my parents died. I was about six or seven. I had no money and made my way to Conakry by going with truck drivers. First I tried to go by foot, but I was very hungry. So I was forced to go with men who wanted to have sex with me.[90]

Traffic accidents are a serious problem in West Africa, particularly for poor persons traveling on cheap transport.The 2003 death of two Malian girls en route to Conakry for child domestic work highlighted this problem dramatically. Sata Camara, 15 years old, and 14-year-old Fati Camara (their real names) died on the spot. Five other girls between the ages of 12 and 18, also in the car, were injured.[91]After the car accident, the Malian community in Guinea mobilized against trafficking and exploitation of children.

Most girls from Mali cross the border without proper documentation. They rely on the intermediaries to organize the paperwork for them, and become dependent on them in that way. Intermediaries may bribe border officials in the absence of correct documentationfor children, this would include both an identity card and parental travel authorization.[92]

III. Life of Girl Domestic Workers in Lower Guinea

According to a recent ILO study on child labor in Guinea, based on interviews with 6,037 children, domestic labor is by far the biggest employment sector for children. Of working children 61.4 percent are domestic workers.The majority of them are girls.[93] Based on the relative (percentage) figures given in the study, about 1.2 million girls in Guinea are doing domestic work, including those who work for their own parents. The vast majority of children indicated that their work place is their home; it is likely that children working for relatives or other de facto guardians described their work place as the home, too.[94] Neither the government nor U.N. agencies have absolute figures on the number of girl domestic workers in Guinea.[95]

Once girls have arrived at their new host family, the harsh life of a child domestic worker starts. This is particularly the case for the vast majority who live with their employers. Many experience labor exploitation as well as child abuse and neglect. Girl domestic workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch described working excessive hours, carrying heavy weights at a young age, working for no pay, starving while the host family eats, and being insulted, shunned, beaten, sexually harassed and raped.

This is not the case for all girl domestic workers. Living and working away from the family can be a positive experience. Ten-year-old Christine C. prefers living with her cousin in Conakry to living with her mother in the village. She explained:

I was in the household of my cousin in Conakry. I went there when I was small. When my cousin got married, she asked for a girl to be sent to her and help her. So I was sent. When I lived with her, I cleaned the courtyard, fetched water, did the dishes, and washed the laundry. I was well taken care of. They did not have many things; my mom even had to send clothes from here. My cousin put me into school up to second grade. Then I had to go back to my mother. I had to come back because my mum needed a girl at home. I came back when I was eight or nine years old. My mother is old. I would like to go back to Conakry. I want to go to school with my girlfriends again.[96]

Indeed, child fostering can be useful for economic survival, education and socialization. These systems can work well when there is a viable social network of persons monitoring the child's well-being.

Certain factors increase a child's vulnerability, and hence the risk of abuse. Girl domestic workers tend to be vulnerable to abuse due to their gender, the absence of their biological parents, and their background from mostly poor rural families. If they do not have at their disposal networks of support, such as continued contact with their parents and integration into other social networks, they are at greater risk of abuse.[97]While studies in Africa have indicated that foster children and other non-related children are particularly likely to be kept out of school and experience abuse,[98] biologically-related children are not necessarily shielded from neglect and violence by their parents either.[99]

The double role of employer and guardian

The adults who employ and host girls as domestic workers have a double responsibility as employer and as de facto guardian of a child in their care.

As employers, they have to respect the labor rights of the girls. Children under 15 should not be employed at all; those over the age of 15 have the right to a fair wage, limited working hours, decent working conditions such as proper accommodation, nutrition and health care, rest during the day, weekly rest days and holidays.[100]

But the role of the host family goes beyond respecting the labor rights of the child. When adults decide to take in a girl as a domestic worker, she is effectively in their care, and they become de facto guardians with the responsibility to respect her rights.

Labor exploitation of girl domestic workers

Some girls become domestic workers so early that they cannot remember the age at which they started. Most of the 40 girls interviewed for this research started domestic work under the age of eight.

Under Guinean law, the general rule is that children under the age of 16 should not be employed and therefore cannot lawfully enter into an employment contract. However, Guinea law makes provision for those under 16 to be lawfully employed if their parents or legal guardians give consent. Such a "claw back" clause in the law effectively undermines any meaningful protection for children under 15, particularly girls who are often sent by their parents to work as domestic workers.[101]

Whether a girl is over 16, or under 16 and her parents have consented to her employment, where she is required to work full-time in the household beyond what may be reasonably considered light household chores, and even where such work is not coerced, a de facto employment relationship exists. All girls so employed must be afforded their full labor rights. At present, girls of all ages suffer labor exploitation, some of which amounts to forced labor.

Crude exploitation: Work for no or little pay

A recent study of child labor in Guinea by the International Labor Organization (ILO), based on interviews with over 6000 children, also found that "many children work but few are paid."The study found that 6.8 percent of boys and 5 percent of girls were paid. Children living in Conakry and those over 15 had slightly higher chances of getting paid.[102]

Most girls interviewed in the course of our research received no salary. Even those who had been promised a salary and given a specific figure frequently did not get paid. Of 40 Guinean and Malian girls interviewed, only ten had received any salary. Of those, five had had jobs in which they were paid the agreed salary in a regular manner; the other five were promised the salary but were only paid at the start, irregularly, or only part of the promised money. Four of the five who did get a regular wage had also held jobs in which they were not paid, irregularly paid, or paid less than had been agreed, including through payment in kind. Usually, girl domestic workers did not have a written contract.

Salaries for 40 girl domestic workers in Guinea

($1 = about 6000GNF, as of May 2007[103])

Monthly salary |

Number of girl domestic workers[104] |

Number that received a regular salary |

None |

30 |

-- |

Below GNF20,000 (=about $3.33) |

5 |

1 |

GNF20,000 50,000 (=about $3.33 8.33) |

2 |

2 |

Above GNF50,000 (more than about $8.33) |

3 |

2 |

Total |

40 |

5 |

In many cases, there were no discussions about salary at all. A girl was simply sent to work as child domestic worker for some of the reasons explained above.[105] When girls were placed with relatives or other people at a young age, their labor was not considered work worthy of pay; it was just seen as their contribution to family life. In many cases the girls themselves did not ask for a salary and even seemed surprised about the question. Parents and the employers themselves often defined the situation more in terms of child fostering; they did not look at it as child labor. Even when there was a salary paid, the girl was usually not involved in salary negotiations, rather she was told that she was going to get a certain amount. This was the case of 14-year-old Liliane K., who even sent some of her meager income to her mother:

I am from Kissidougou. My father died. My mother gave me to a woman who was our neighbor. My mother did not have a choice because she did not have money to look after her children. Because of the war, the neighbors wanted to leave Kissidougou and go to Conakry. My mother is still in the village. I was about nine when I arrived here in Conakry. I should normally get GNF10,000 [about $1.60] per month, but sometimes I only get 5,000 or 7,000. The tutrice says sometimes that she does not have enough money to pay me. I send some money to my mother. I give it to people who are going to the village. Since I am here, I have been told that my mother suffers a lot. I have never seen my mother or been in contact with her since I came here.[106]

Child domestic workers can never be sure they will get the promised salary. Justine K. was sent to live with her aunt in Conakry at a young age, but started to work for another family as child domestic worker to escape her situation:

I heard that a family was looking for a girl domestic worker. They offered GNF10,000 [about$1.60] per month. At the outset, I told them to keep my salary and give it to me every four months. But after the first year, they stopped giving me money and said they would send it to my parents instead.I don't even think they knew my parents, and my parents told me they never received the money.[107]

Older girls are slightly more likely to get paid. The ILO found this in its larger study, and it was also the case among the 40 girls interviewed by Human Rights Watch. Six girls interviewed had started working as child domestic workers at the age of 15 or older; five of them had received salaries. For example, Francine B., who found work with a Lebanese-Guinean couple, was paid GNF25,000 (about $4.16) on a regular basis.[108] Malian girls also sometimes managed to get jobs where they got a regular salary. In 2002-2003, the High Council of Malians drew up a list of seven Malian girl domestic workers in Conakry; they all received GNF7,500 (about $1.25).[109] Three of the Malian girls interviewed at some point received between GNF50,000 and GNF75,000 (about $8.30 and $12.50) and were paid regularly.[110] However, these three girls had only arrived at these jobs after having been exploited with no pay in previous jobs, and having received some help from fellow Malians to leave these jobs and find better positions. Nadine T., an 18-year-old Malian domestic worker, explained:

I came to Conakry two years ago. I met a woman at Bamako, Tigira Conde. She said it is good in Conakry. You can earn good money, and go dancing and have fun in Conakry. She sent me to work somewhere for six months. But I did not get a salary. I don't know if Tigira Conde got any money. I am now working elsewhere and doing fine there. I am paid GNF75,000 there.[111]

The Malian community is aware of these problems and has frequently intervened to assist the girls get their salary. In one such case, a young woman in her early twenties was assisted by members of the Malian community to get her salary for about eight years she had worked as child domestic worker without pay. The employer finally paid about GNF800,000 to the woman.[112] The Malian High Council has even demanded salary payments when girls were employed below the legal minimum age. In 2004, the High Council of Malians in Guinea identified two such girls, aged, 12 and 13, who had worked as child domestic workers without pay. Leading members of the High Council went to see the employers of these girls; as they refused to pay them, the High Council of Malians threatened to take the family to court. The salary was found to be about GNF800,000 (about $120). The tutrice eventually paid half of what was owed to the girls.[113]

Payments for intermediaries

In some cases, intermediaries who had recruited a girl from Mali received a portion or all of the salary. Florienne C., whose case is mentioned above, was exploited in that way. She had been told by her intermediary that she could earn GNF25,000 (about $4.16) in Conakry. When she arrived this did not happen:

I worked as domestic worker for one year and three months. At the end, my tutrice paid the money to the woman in Madina [the intermediary], and she took my money. It was GNF385,000 (about $64). The woman [intermediary] just refused to give me the money. I was sent elsewhere. But after one month I was dismissed. Then, I worked for two years at one place. When my father died, I returned home. I wanted to have my salary from the two years, but the tutrice decided to pay me in kind.[114]

Other members of the Malian community confirmed that intermediaries took some of the money paid for the service of child domestic workers.[115] According to a Malian girl living in Conakry, they are supposed to take half of the salary and give the other half to the girl herself.[116]

Most Guinean girl domestic workers interviewed did not know whether intermediaries received any money. However, in two cases the girls knew that their employer was sending money to the person who had sent them. Berthe S., 17 years old, lived with her aunt who sent her to do domestic work at the neighbor's. Her aunt received Berthe's monthly salary of GNF30,000 (about $5). In addition, the girl has to do domestic work at her aunt's place.[117] The host of Georgette M. from the Forest Region, whose case is described above, regularly sent shoes or cloth to her mother back in the village.[118]

There seem to be well-established networks of intermediaries who make money by placing Guinean children as domestic workers. According to a representative of the Ministry of Social Affairs:

There is a woman there who functions as intermediary and places the girls as domestic workers. At the end of the month the tutrices go there and pay this woman some money. She always gets money from placing the girls, while the girls themselves sometimes do not have a salary.[119]

Types of work