I. Summary

From fear of terrorism, from threats of the enemies of Afghanistan, today as we speak, some 100,000 Afghan children who went to school last year, and the year before last, do not go to school.

-President Karzai on International Women's Day, March 8, 2006.

During Ramadan [late 2005], the girls were still going to school. There was a letter posted on the community's mosque saying that "men who are working with NGOs and girls going to school need to be careful about their safety. If we put acid on their faces or they are murdered, then the blame will be on the parents." . . . After that, we were scared and talked about it, but we decided to let them keep going anyway. But after Eid, a second letter was posted on the street near to there, and the community decided that it was not worth the risk [and stopped all girls over age ten from going to school]. . . . My daughters are afraid-they are telling us "we'll get killed and be lying on the streets and you won't even know."

-Mother of two girls withdrawn from fourth and fifth grades, Kandahar city, December 8, 2005.

Brutal attacks by armed opposition groups on Afghan teachers, students, and their schools have occurred throughout much of Afghanistan in recent months, particularly in the south. These attacks, and the inability of the government and its international backers to stop them, demonstrate the deteriorating security conditions under which many Afghans are now living. While ultimate responsibility lies with the perpetrators, much about the response of the international community and the Afghan government can and must be improved if Afghanistan is to move forward. The situation is not hopeless, yet.

This crisis of insecurity, now affecting millions of Afghans, was predictable and avoidable. The international community, led by the United States, has consistently failed to provide the economic, political, and military support necessary for securing the most basic rights of the Afghan people. As detailed below, groups opposed to the authority of the Afghan central government and its international supporters have increasingly filled this vacuum, using tactics such as suicide bombings and attacks on "soft targets" such as schools and teachers to instill terror in ordinary Afghans and thus turn them away from a central government that is unable to protect them. Such attacks are not just criminal offenses in violation of Afghan law; they are abuses that infringe upon the fundamental right to education. When committed as part of the ongoing armed conflict in Afghanistan, these attacks are serious violations of international humanitarian law-they are war crimes.

Insecurity-including acts designed to instill terror in civilians, actual fighting between rival groups or armed opposition groups and international security forces, and rampant lawlessness-affects all aspects of Afghans' lives: their ability to work, to reach medical care, to go to the market, and to attend school. Afghan women and girls, who have always confronted formidable social and historical barriers to traveling freely or receiving an education, especially under the Taliban and their mujahedin predecessors, are particularly hard hit.

This report examines the impact of insecurity on education in Afghanistan, especially on girls' education. It concentrates on armed attacks on the education system in the south and southeast of the country, where resurgent opposition forces, local warlords, and increasingly powerful criminal groups have committed abuses aimed at terrorizing the civilian population and contesting the authority of the central government and its foreign supporters. This confrontation has stunted and, in some places, even stopped the development and reconstruction work so desperately desired and needed by local residents.

Attacks on all aspects of the education process sharply increased in late 2005 and the first half of 2006. As of this writing, more attacks have been reported in the first half of 2006 than in all of 2005. Previously secure schools, such as girls' schools in Kandahar city and in northernprovinces such as Balkh, have come under attack. There have been reports of at least seventeen assassinations of teachers and education officials in 2005 and 2006; several are detailed below. This report also documents more than 204 attacks on teachers, students, and schools in the past eighteen months (January 2005 to June 21, 2006).

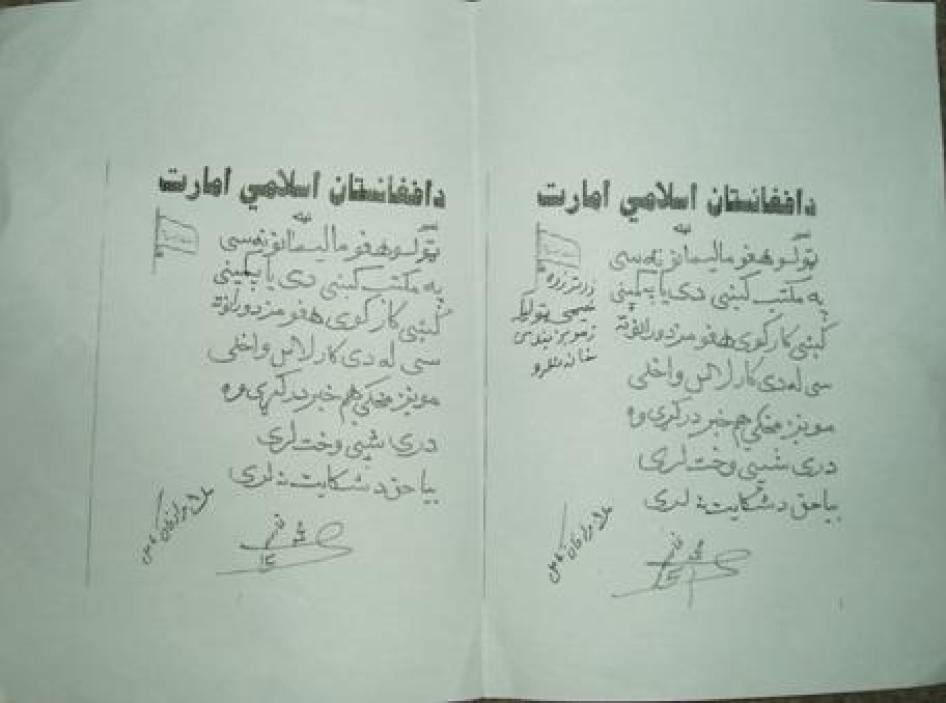

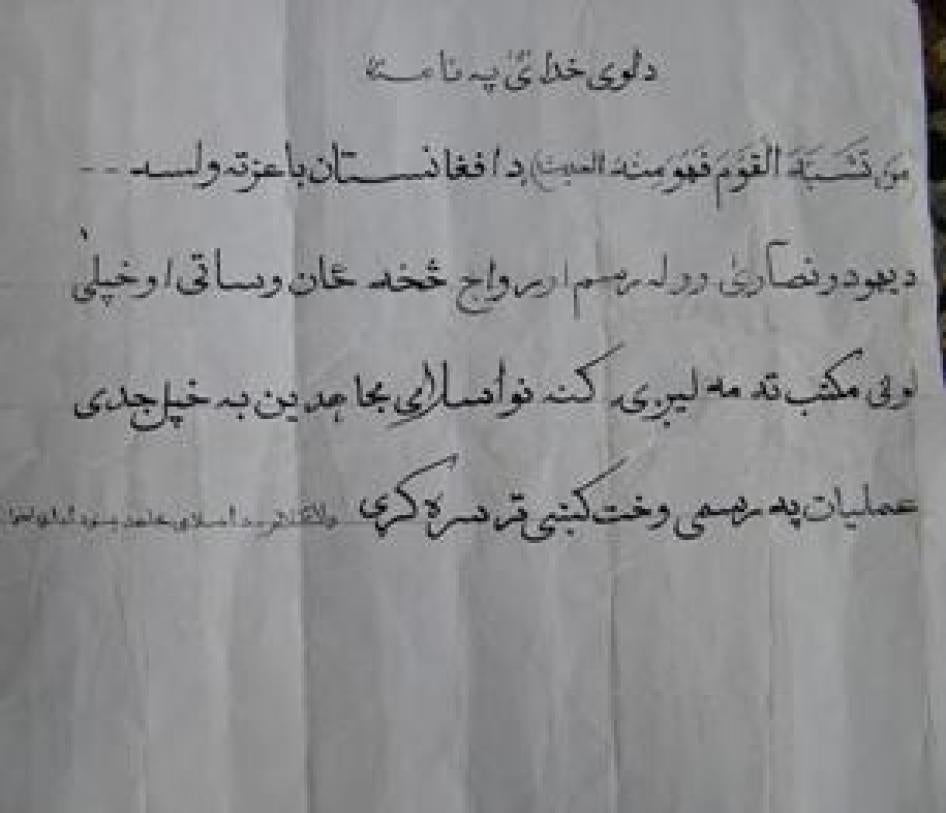

Even more common have been threatening "night letters," alone or preceding actual attacks, distributed in mosques, around schools, and on routes taken by students and teachers, warning them against attending school and making credible threats of violence.

Physical attacks or threats against schools and their staff hurt education directly and indirectly. Directly, an attack may force a school to close, either because the building is destroyed or because the teachers and students are too afraid to attend. Attacks and threats may also have an indirect ripple effect, causing schools in the surrounding area to shut down as well.

General insecurity and violence targeted against education also exacerbate other barriers that keep children, particularly girls, from going to school. These include having to travel a long way to the nearest school or having no school available at all; poor school infrastructure; a shortage of qualified teachers, especially women teachers; the low quality of teaching; and poverty. All of these factors affect, and are affected by, Afghanistan's varied but conservative culture. Each has a greater impact on girls and women, in large part because there are far fewer girls' schools than boys' schools.

Measuring the deleterious impact of insecurity on education provides a strong diagnostic indicator of the costs of insecurity more generally. Basic education is important for children's intellectual and social development and provides them with critical skills for leading productive lives as citizens and workers. Education is central to the realization of other human rights, such as freedom of expression, association, and assembly; full participation in one's community; and freedom from discrimination, sexual exploitation, and the worst forms of child labor. Education also facilitates many other socially important activities, such as improvements in the economy, development of the rule of law, and public health. Restrictions on girls' right to education especially hurt the country's development: for example, girls' and women's literacy is associated with lower infant and maternal mortality and, unsurprisingly, better education for future generations of children. Girls not educated today are the missing teachers, administrators, and policymakers of tomorrow. After the Taliban, Afghanistan cannot afford to lose another generation. Such a tragedy would compound the misfortune the already beleaguered nation has faced.

In focusing on the nexus between insecurity and access to education, we seek to establish new benchmarks for assessing the performance of Afghan and international security forces and measuring progress on the security front. The benchmarks most often used at present-numbers of Afghan troops trained and international troops deployed, or the number of armed opponents killed-are important, but they do not accurately assess the security situation. What is more important is how much these and related efforts improve the day-to-day security of the Afghan people. We urge that access to education be made one key benchmark.

We suggest this benchmark for three reasons:

- on a political level, because teachers and schools are typically the most basic level of government and the most common point of interaction (in many villages the only point of contact) between ordinary Afghans and their government;

- on a practical level, because this benchmark lends itself to diagnostic, nationally comparable data analysis (for instance, the number of operational schools, the number of students, the enrollment of girls) focused on outcomes instead of the number of troops or vague references to providing security; and,

- on a policy level, because providing education to a new generation of Afghans is essential to the country's long-term development.

Plight of the Education System

The Taliban's prohibition on educating girls and women was rightly viewed as one of their most egregious human rights violations, even for a government notorious for operating without respect for basic human rights and dignities. But even before the Taliban, the mujahedin factions that ripped the country apart between 1992 and 1996 often opposed modern education, in particular the education of girls.

Since the United States and its coalition partners ousted the Taliban from power in 2001, Afghans throughout the country have told Human Rights Watch that they want their children-including girls-to be educated. Afghans have asked their government and its international supporters to help create the infrastructure and environment necessary for educating their children.

A great deal of progress has been made. When the Taliban were forced from power, may students returned to school. According to the World Bank, an estimated 774,000 children attended school in 2001.[1] By 2005, with girls' education no longer prohibited and with much international assistance, 5.2. million children were officially enrolled in grades one through twelve, according to the Ministry of Education.[2] (All statistics on education in Afghanistan should be understood as rough approximations at best.)

Despite these improvements, the situation is far from what it could or should have been, particularly for girls. The majority of primary-school-age girls remain out of school, and many children in rural areas have no access to schools at all. At the secondary level, the numbers are far worse: gross enrollment rates were only 5 percent for girls in 2004, compared with 20 percent for boys.[3] Moreover, the gains of the past four-and-a-half years appear to have reached a plateau. The Ministry of Education told Human Rights Watch that it did not expect total school enrollments to increase in 2006; indeed, they expect new enrollments to decrease by 2008 as refugee returns level off.[4] In areas where students do attend school, the quality of education is extremely low.

Two critical factors are, first, that attacks on teachers, students, and schools by armed groups have forced schools to close, and, second, that attacks against representatives of the Afghan government and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), along with general lawlessness, has made it too dangerous for them to open new schools or continue to operate in certain areas. Where schools do remain open, parents are often afraid to send their children-in particular, girls-to school. The continuing denial of education to most Afghan children is a human rights crisis that should be of serious concern to those who strive to end Afghanistan's savage cycle of violence and war.

Sources and Impact of Insecurity

Insecurity in Afghanistan is most dire in the country's south and southeast, although it is by no means limited to those areas. The problem is particularly acute outside of larger urban areas and off major roads, where an estimated 70 percent of Afghans reside and where U.S. forces, the International Security Assistance Force led by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and Afghanistan's small but growing security forces rarely reach.

Three different (and at times overlapping) groups are broadly responsible for causing insecurity in Afghanistan: (1) opposition armed forces, primarily the Taliban and forces allied with the Taliban movement or with veteran Pashtun warlord Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, (2) regional warlords and militia commanders, ostensibly loyal to the central government, now entrenched as powerbrokers after the flawed parliamentary elections of October 2005, and (3) criminal groups, mostly involved in Afghanistan's booming narcotics trade-a trade which is believed to provide much of the financing for the warlords and opposition forces. Each of the above groups attempts to impose their rule on the local population, disrupt or subvert the activity of the central government, and either divert development aid into their own coffers or block development altogether.

In many cases that Human Rights Watch investigated, we were not able to determine with certainty either who was behind a particular attack or the cause. But it is clear that many attacks on teachers, students, and schools have been carried out by Taliban forces (now apparently a confederation of mostly Pashtun tribal militias and political groups) or groups allied with the Taliban, such as the forces of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar's Hezb-e Islami (previously bitter rivals of the Taliban). But the Taliban are clearly not the only perpetrators of such attacks, because in many areas local observers and Human Rights Watch's investigation indicated the involvement of militias of local warlords (for instance in Wardak province, where forces loyal to the warlord Abdul Rabb al Rasul Sayyaf hold sway) or criminal groups (such as those controlling smuggling routes in Kandahar and Helmand provinces).

The motives behind the attacks differ. In some instances, it appears that the attacks are motivated by ideological opposition to education generally or to girls' education specifically. In other instances schools and teachers may be attacked as symbols of the government (often the only government presence in an area) or, if run by international nongovernmental organizations, as the work of foreigners. In a few cases, the attacks seem to reflect local grievances and rivalries. Regardless of the motivation of the attackers, the result is the same: Afghanistan's educational system, one of the weakest in the world, is facing a serious and worsening threat.

Insecurity, and the attendant difficulty it causes for government agencies, foreign reconstruction groups, and aid organizations, has also distorted national-level reconstruction policies in Afghanistan. Southern and southeastern Afghanistan, which have suffered most from insecurity, have witnessed a significant drop in reconstruction activity.

Many NGOs, which play a significant role in providing education and other development activities in Afghanistan, no longer feel it is safe to operate outside of urban areas and off major roads linking them. As of this writing-midway through 2006-already twenty-four aid workers have been killed in Afghanistan this year, a significant increase from the rates seen in previous years, when thirty-one aid workers were killed in 2005 and twenty-four in 2004. Several large international NGOs told Human Rights Watch in December 2005 that they had curtailed their activities in the south and southeast or aborted plans to operate there as a result of insecurity. Afghan NGOs also face significant constraints. Together, security, logistical, and infrastructural limitations are keeping organizations out of the areas where their assistance is most needed. A senior Western education expert working in Afghanistan expressed his apprehension about this phenomenon: "We are very concerned about disparities that we're creating. We're not covering the whole country. There are some places in the country that have never seen a U.N. operation."[5]

The failure to provide adequate aid to southern and southeastern Afghanistan also has significant political impact because it has fostered resentment against the perceived failures and biases of the central Afghan government and its international supporters. Afghans in the largely Pashtun south and southeast complain when they see more development aid and projects go to non-Pashtun areas in other parts of the country. Lacking the ability to confront the security threats facing them, they feel that they are being doubly punished-by the Taliban and criminal groups who impinge on their security, and by international aid providers being driven away due to (justified) fear of the Taliban, other opposition elements, and criminal groups.

International and Afghan Response to Insecurity

The international community has shortchanged Afghanistan' security and development since the fall of the Taliban both qualitatively and quantitatively. International military and economic aid to Afghanistan was, and remains, a fraction of that disbursed by the international community in other recent post-conflict situations. For the past four years, Afghanistan's government and its international supporters, chiefly the United States, have understood security mostly as a matter of the relative dominance of various armed forces. Presented this way, addressing insecurity revolves around matters such as troop numbers, geographic coverage, and political allegiance. Development and reconstruction become viewed as part of a "hearts and minds" campaign necessary to placate a potentially hostile population-not as preconditions for a healthy, peaceful, and stable society, and certainly not as steps toward the realization of the fundamental human rights of the Afghan people.

The international community's chief tool for providing security and local development in Afghanistan has been the Provincial Reconstruction Teams (PRTs), military units ranging in size from eighty to three hundred military personnel combined with a small number (usually about 10 percent of the total) of civilians from a development background or the diplomatic corps. The PRT program, initially developed by the United States to compensate for the inadequate troop numbers committed to secure Afghanistan after the Taliban, eventually became the template for international security assistance. After three years, the PRT program has now expanded to most of Afghanistan's provinces; as of this writing there are twenty-three PRTs operating in Afghanistan (note, however, that the presence of small PRTs in a province does not necessarily mean there is geographic coverage of the province outside PRT headquarters). The United States still operates the most PRTs, all of them now in southern and southeastern Afghanistan, where military threats are more pronounced. Other countries, mostly under the umbrella of NATO, including the United Kingdom, Canada, the Netherlands, and Germany, as well as non-NATO U.S. allies such as New Zealand, also field PRTs. The U.K., Canada, and the Netherlands have begun moving PRTs into some provinces in southern Afghanistan since mid-2005. NATO is scheduled to take over security in southern Afghanistan by mid 2006.

The PRTs were conceived of as a blend of military frontier posts and humanitarian and development aid providers. This has proven to be an uneasy combination, from the military point of view as well as in terms of development. There is no coherent nationwide strategy for the PRTs, nor are there any clear benchmarks for their performance. Each PRT reports to its own national capital, and, despite some efforts at coordination, does not share information or lessons learned with other PRTs. The handful of public assessments of the PRTs' performance have generally agreed that thus far, the PRTs have succeeded in improving security and development only in fairly limited areas, primarily in northern and central Afghanistan. In this sense PRTs may be considered to have been successful within their limited areas of operation. But the PRTs have not provided an adequate response to the broader problem of insecurity in Afghanistan, as evidenced by the country's overall deteriorating security situation. Nor have they been particularly successful at providing development or humanitarian assistance.

Key Recommendations

The government of Afghanistan is ultimately responsible for the security of the Afghan people. The Afghan army and police forces operate with varying degrees of effectiveness. In practice, U.S.-led coalition forces and NATO provide much of the security structure throughout the country, and particularly in the south and other volatile areas. As the responsibility for providing security in southern Afghanistan shifts from the U.S.-led coalition to NATO forces, Human Rights Watch believes that a key measure of their success or failure should be whether children are able to go to school. This will require a military and policing strategy that directly addresses how to provide the security necessary for the Afghan government and its international supporters to develop Afghanistan's most difficult and unserved areas.

The Afghan government and the international community have not developed adequate policy responses to the impact of increasing insecurity on development in general, and education in particular-a particularly sensitive topic because education is often touted as one of the major successes of the post-Taliban government in Afghanistan.

Unfortunately, the international community and the Afghan government have failed to address this policy shortcoming in the "Afghanistan Compact," the blueprint for Afghanistan's reconstruction agreed upon after a major international conference in London in January 2006. While the compact lists security as one of the key components of Afghanistan's reconstruction, security is discussed in terms of troop numbers, instead of whether the composition and mission of these forces is sufficient to improve security for the population at risk. The compact explicitly links itself with the Afghanistan National Development Strategy, but development goals-more broadly speaking, the notion of human security-do not appear among the benchmarks used to measure security. In implementing the compact, the Afghan government and the international community should ensure that they refocus their security efforts on fostering a climate conducive to the necessary work of development and reconstruction.

Human Rights Watch urges the Afghan government, NATO, and U.S.-led coalition forces to implement a coherent, nationwide security policy firmly tethered to the development needs of the Afghan people. A critical benchmark of success in improving security should be whether Afghans can exercise their basic rights, starting with access to basic education. Such a benchmark should be explicitly incorporated into the Afghanistan Compact.

Human Rights Watch also urges NATO and the U.S.-led Coalition to improve coordination between their PRTs and the government; to improve communication with aid organizations, and, within six months, to assess whether they have committed resources (troops, materiel, and development assistance) sufficient to meet set goals.

Finally, given the emergence of schools as a frontline in Afghanistan's internal military conflict, Human Rights Watch urges the government and its international supporters to immediately develop and implement a policy specifically designed to monitor, prevent, and respond to attacks on teachers, students, and educational facilities.

More detailed recommendations can be found at the end of this report.

* * *

This report is based on Human Rights Watch research in Afghanistan from May to July 2005, and from December 2005 to May 2006, as well as research by telephone and electronic mail from New York. In Afghanistan we visited the provinces of Balkh, Ghazni, Heart, Kabul, Kapisa,Laghman, Logar, Kandahar, Nangarhar, Paktia, Parwan, and Wardak. We also spoke in person and by telephone with people from other provinces, including Helmand and Zabul, which we were unable to visit due to security concerns. During the course of our investigations, we interviewed more than two hundred individuals, including teachers, principals, and other school officials; students; staff of Afghan and international NGOs; government officials responsible for education at the district, provincial, and national levels; staff of the Ministry of Women's Affairs; members of the Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission; police officials; staff of the European Union, World Bank, USAID and its contractors, and the United Nations, including the U.N. Assistance Mission to Afghanistan, the U.N. Children's Fund (UNICEF), and the United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM); officials from NATO; and other experts on education or security in Afghanistan. Many Afghans asked that their names not be used, fearing retaliation for identifying opposition groups, including the Taliban and local strongmen, that they believe are responsible for the attacks on schools documented in this report. "I'm afraid of this attack, this terrorism," a man working in Logar told us. "Don't mention our names in this report. There is no security. We don't feel secure in border areas."[6] Similarly, many NGO staff and others working in the field of education requested anonymity, reflecting both fear of these groups and pressure to maintain a positive picture of education in Afghanistan in the face of crisis.

All numbers in this report regarding education should be understood as rough estimates only-data are incomplete and those which are available are often unreliable and conflicting.[7] Figures on school enrollment for 2005-2006 are those provided by the Ministry of Education to Human Rights Watch. The most comprehensive data on factors affecting participation in education available at the time of writing remains that of two nearly nationwide surveys conducted in 2003: the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) and the National Risk and Vulnerability Assessment (NRVA).[8] The 2006 briefing paper of Afghan Research & Evaluation Unit (AREU) entitled "Looking Beyond the School Walls: Household Decision-Making and School Enrollment in Afghanistan" also provides valuable insights regarding several key areas of the country.

Glossary

ANSO: Afghanistan Nongovernmental Organization Safety Office, which monitors security incidents that affect the operations of nongovernmental organizations.

Afghani:The currency of Afghanistan. The afghani traded at various levels in 2005-2006: one U.S. dollar bought between45 and 50 afghanis.

burqa and chadori: Terms used interchangeably in many parts of Afghanistan to describe a head-to-toe garment worn by women that completely covers the body and face, allowing vision through a mesh screen.

Dari: The dialect of Persian spoken in Afghanistan, one of Afghanistan's main languages.

hijab: Generally, dress for women that conforms to Islamic standards, varying among countries and cultures; usually includes covering the hair and obscuring the shape of the body.

ISAF: International Security Assistance Force provided by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization under mandate of the United Nations.

mujahedin: "Those who engage in jihad." By common usage in Afghanistan, and as used in this report, the term refers to the forces that fought successive Soviet-backed governments from 1978 until 1992, although many former mujahedin parties continue to use it in reference to themselves.

night letters ("Shabnameh"): Letters left in homes or public places, such as roadsides and mosques, threatening individuals or communities for engaging in certain activities. Letters may be anonymous or signed, and may warn against activities such as working with the government or with foreigners, or sending children, often girls in particular, to school.

Pashto: The primary language spoken by many Pashtuns.

Pashtun: The largest ethnicity in Afghanistan and a plurality of the population (Pashtuns also reside in Pakistan).

PRTs: Provincial Reconstruction Teams, military units ranging in size from eighty to several hundred, with a small civilian development component. Each PRT is fielded by a donor country as part of NATO or the U.S.-led Coalition forces. The make up and function of the PRTs differ based on the donor country, the mission of the PRT, and the location.

shura: "Council." The shuras mentioned in this report include both governmental and nongovernmental bodies.

II. Background: Afghanistan Since the Fall of the Taliban

The Taliban's Ouster, the Bonn Process, and the Afghanistan Compact

It has been more than four years since the United States ousted the Taliban from Kabul in retaliation for their support for Osama bin Laden and the large-scale murder of civilians in the United States on September 11, 2001. Much has improved in the lives of Afghans in the past four years, the most significant improvement perhaps being the ability to hope for a better future for Afghanistan's next generation. But the hopes of many Afghans are today beset by a growing crisis of insecurity.

This crisis was predictable and largely avoidable. The failure of the international community, led by the United States, to provide adequate financial, political, and security assistance to Afghanistan despite numerous warnings, created a vacuum of power and authority after the fall of the Taliban. Where the United States and its allies failed to tread, abusive forces inimical to the well-being of the Afghan people have rushed in.

The United States and the international community too often favored political expediency over the more painstaking efforts necessary to create a sustainable system of rule of law and accountability and in Afghanistan. The Bonn Agreement, which in November 2001 (before the Taliban had been ousted) established a framework for creating a government in Afghanistan after the Taliban, focused on political benchmarks such as the selection of a transitional government, the drafting of a constitution, and holding presidential and parliamentary elections; it did not include clear guidelines about how these institutions were to operate. The first clear signal that the international community, and in particular its de facto leader in Afghanistan, the United States, would tolerate and even support the return of the warlords came during the Emergency Loya Jirga ("grand council") convened in June 2002 to form Afghanistan's transitional government. Although many warlords had been kept out of the meeting under the selection provisions, a last minute intervention by Zalmai Khalilzad, then the U.S. ambassador to Afghanistan (and currently the U.S. ambassador to Iraq), and Lakhdar Brahimi, the special representative of U.N. Secretary General Kofi Annan, gave access to all the major regional militia commanders. Their intimidating presence immediately distorted the proceedings and disappointed Afghans hoping for a new beginning.[9] The authority and power of regional warlords and militia commanders grew with every step in the Bonn Process.[10]

The Bonn Process officially ended with the parliamentary elections of September 2005. Election day itself was relatively peaceful, but it followed a campaign marked by intimidation (especially against women candidates and voters) and voter discontent, ultimately reflected in a turnout much lower than expected.[11]

With the end of the Bonn Process, at the beginning of 2006 the international community established a new framework for its cooperation with the Afghan government for the next five years. This new frameworkknown as the Afghanistan Compactwas unveiled at an international conference in London in January 2006 with much fanfare and congratulatory rhetoric: The conference's official tagline was "Building on Success." The reality was more sobering. As U.N. Secretary General Kofi Annan was quick to point out in London, "Afghanistan today remains an insecure environment. Terrorism, extremist violence, the illicit narcotics industry and the corruption it nurtures, threaten not only continued State building, but also the fruits of the Bonn Process."[12] Events have since borne out the accuracy of Annan's cautionary statement.

Even though Afghanistan met the political markers established by the Bonn Process-drafting a constitution and electing the president and parliament-the situation in the country is far from healthy. The Taliban and other armed groups opposing the central government are resurgent. Parliament is dominated by many of the warlords, criminals, and discredited politicians responsible for much of Afghanistan's woes since the Soviet invasion in 1979. Production and trade of narcotics provide more than half of Afghanistan's total income and is a major source of violence, corruption and human rights abuse. Some of the same warlords in parliament or in key official positions in the government or security forces control the drug trade. Afghanistan remains one of the world's least developed countries,[13] and President Karzai's government remains completely reliant on international financial, political, and military support.[14]

Afghans look to President Hamid Karzai-and beyond him, to his international supporters-for realistic responses to the country's problems. The Afghanistan Compact was the international community's answer, at least for the next five years.

The Compact identifies three major areas of activity, or "pillars": security, governance and human rights, and economic development. The Compact also emphasized cross-cutting efforts to fight Afghanistan's burgeoning production and trafficking of heroin. The Compact established benchmarks for performance in each area, explicitly tied to Afghanistan's National Development Strategy (ANDS).[15] The Compact also established a Joint Coordination and Monitoring Board (JCMB) to ensure overall strategic coordination of the implementation of the Compact, with membership including senior Afghan government officials appointed by the president and representatives of the international community. The JCMB is co-chaired by a senior Afghan government official appointed by the president and by the special representative of the U.N. Secretary-General for Afghanistan.[16]

The Compact's preamble identifies security as "a fundamental prerequisite for achieving stability and development in Afghanistan."[17] Furthermore, the preamble highlights the inextricable link between security and development and committed the international community to support efforts to improve security in order to allow essential development to take place: "Security cannot be provided by military means alone. It requires good governance, justice and the rule of law, reinforced by reconstruction and development. . . . The Afghan Government and the international community will create a secure environment by strengthening Afghan institutions to meet the security needs of the country in a fiscally sustainable manner."[18]

Despite identifying the important relationship between security and development, the security benchmarks used in the Compact referred solely to military and policing, and focused on the size of the different forces, not on their actual capacity to provide security.[19] The ability to carry out the development that is earlier recognized as a "fundamental prerequisite" to security do not appear among these benchmarks.

Similarly, the Compact's benchmarks for development do not refer at all to the fact that, as was obvious while the Compact was being drafted in late 2005, security conditions precluded development and reconstruction in many areas of the country. For instance, the ambitious benchmarks for primary, secondary, and higher education, set out that by 2010:

Net enrolment in primary school for girls and boys will be at least 60% and 75% respectively; . . . female teachers will be increased by 50%; enrolment of students to universities will be 100,000 with at least 35% female students; and the curriculum in Afghanistan's public universities will be revised to meet the development needs of the country and private sector growth.[20]

There was no recognition that in many parts of Afghanistan, schools have become a frontline in the military conflict between the Afghan government and the armed opposition, as documented in this report. These attacks signal a major breakdown in security and in the ability of the central government and its international supporters to provide for the basic needs of the Afghan people and meet the goals established in the Afghanistan Compact.

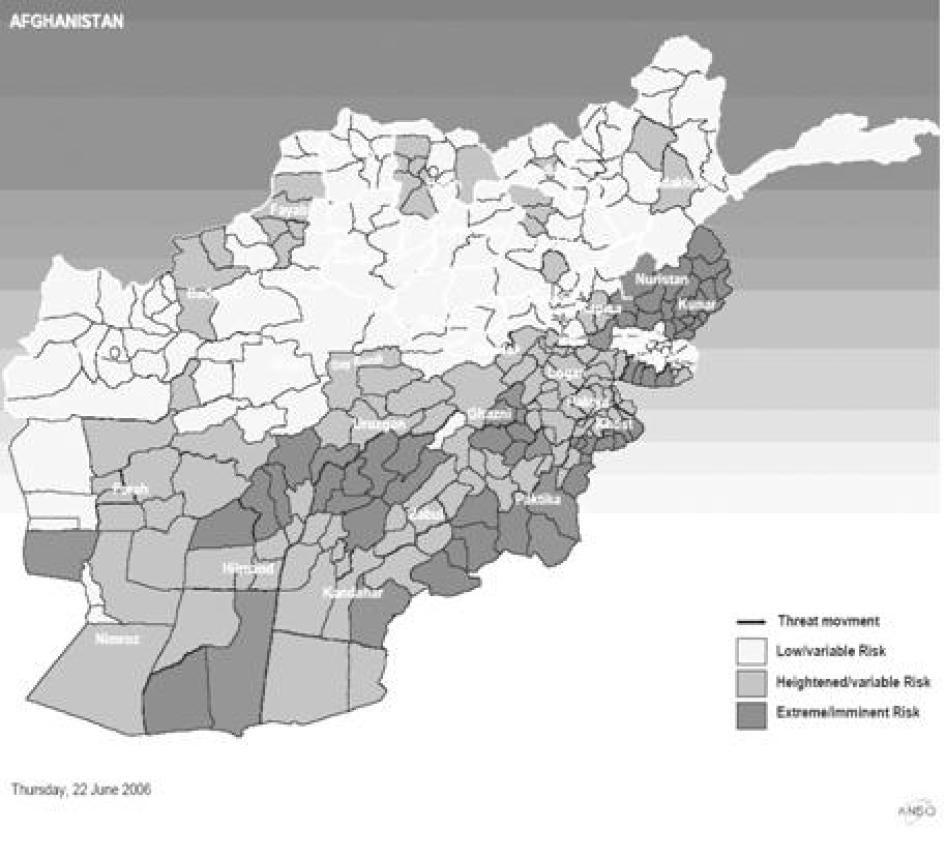

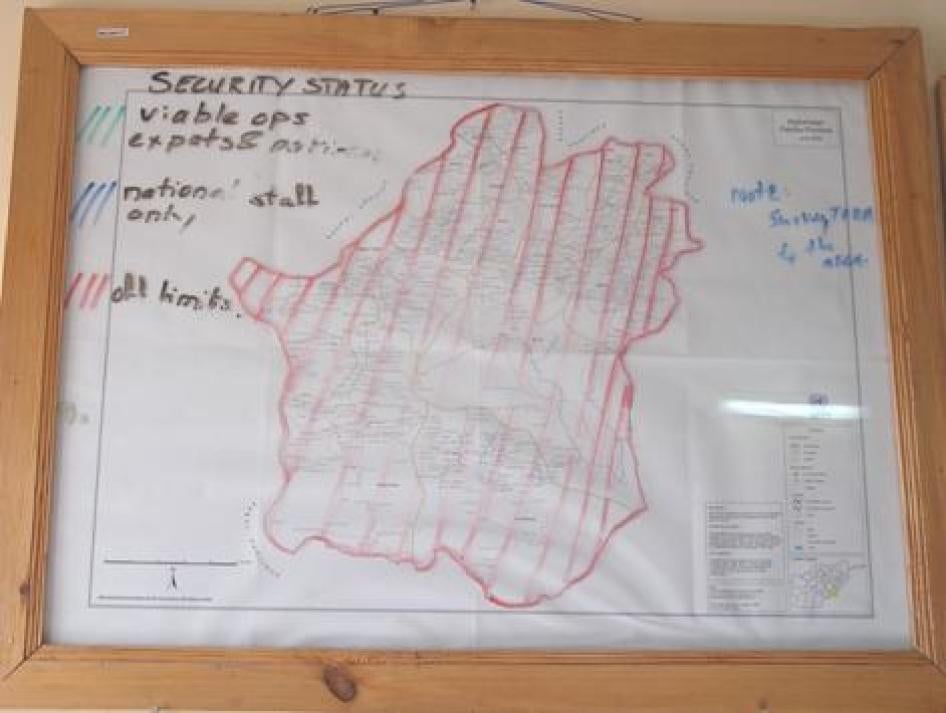

Afghanistan NGO Safety Office map of insecure areas, June 15, 2006. 2006 ANSO

Insecurity in Afghanistan

At its simplest, insecurity in Afghanistan can be understood as violence and the threat of violence, which, depending on the locale, are often quite pervasive. Direct sources of insecurity-that is, the agents responsible for the violence-can be characterized in three overlapping categories:

groups opposed to the central government, including the Taliban, groups linked to the Taliban, those allied with warlord Gulbuddin Hekmatyar; and tribal or ethnic groups opposed to government presence at any given particular time;

forces of regional military figures (warlords, but also some security officials, militia commanders, and even some governors with independent armed forces) who maintain their local authority while ostensibly operating under the umbrella of the central government in Kabul; and,

criminal enterprises, particularly those involved in the production and trafficking of narcotics.

The source and type of insecurity varies across the country, and can be distinguished between the north and south and between urban and rural areas. Insecurity is also perceived differently by men and women and by the local population and foreign aid workers and contractors. Wherever it happens and whoever causes it, the impact of insecurity is largely the same: it keeps Afghans from enjoying their most basic rights as human beings, rights such as the right to life, the rights to freedom of association and assembly, the right to obtain health care, the right to work and to participate in public life, and the right to education.

As explained in Afghanistan's 2004National Human Development Report, "[t]raditional security threats to the people of Afghanistan are both direct (violence, killings, etc.) and indirect. The latter emerge from a weakened state capacity and challenges to the legitimacy of institutions outside the capital, or from the withdrawal of international aid agencies from dangerous but needy zones."[21] In much of Afghanistan, the basic difficulties of living in a war-shattered, impoverished country gripped by draught and chronic food shortages aggravate the insecurity. As set out in more detail below, insecurity has limited the work of the government and of aid agencies in many areas of the south and southeast, exacerbating the insecurity Afghans in these areas experience.

Direct insecurity increased sharply in Afghanistan in 2005 and early 2006. The first half of 2006 (January to June) witnessed the greatest number of conflict-related deaths in Afghanistan since the fall of the Taliban, with nearly 1,000 people, both civilians and combatants, killed in conflict-related incidents in the first six months of the year.[22] This fatality rate is markedly higher than the previous rate of 1,600 people who died in conflict-related violence in 2005, according to the Afghan NGO Security Office (ANSO).[23] For the international community in Afghanistan, this has included attacks on both foreign militaries (NATO and U.S.-led coalition forces) and the humanitarian aid workers whose efforts are essential for maintaining and improving the lives of the Afghan people. For aid workers, 2006 has been a particularly bloody year, with 24 killed as of June 20, 2006.[24] This marks a serious escalation in the risk facing aid workers compared with the previous year, whenthirty-one aid workers were killed-itself a significant increase compared to twenty-four aid workers killed in 2004 and twelve in 2003, according to ANSO.[25]A May 2005 report by CARE and ANSO had already concluded that "though comparative statistics are not readily available, the NGO fatality rate in Afghanistan is believed to be higher than in almost any other conflict or post-conflict setting."[26]

Similarly, Afghan and international military forces have suffered some of their heaviest casualties in 2006. As of June 15, 2006, 300 U.S. troops had died in Afghanistan, as well as eighty-two from other countries[27]; of this total, forty-seven U.S. troops died in 2006, along with seventeen from other countries.[28] This trend continues from 2005, when ninety-one U.S. troops died in combat and from accidents in 2005, more than double the total for the previous year.[29]

Geographically, the sources of insecurity can be distinguished along a line dividing Afghanistan along a gentle gradient from the southwest to the northeast and passing directly through Kabul. North of this line, insecurity largely reflects the activity of narcotics networks and the growing authority and impunity of regional military commanders-warlords-who have returned and entrenched themselves by subverting the political process, most notably during parliamentary elections in September 2005.[30] Many regional commanders were able to use intimidation and fraud to place themselves or their proxies in the national parliament or the local shuras, or provincial councils, thus adding political legitimacy to their rule of the gun and the financial independence many of them enjoy due to the drug trade.[31] Alarmingly, groups allied with the Taliban and with Gulbuddin Hekmatyar have also begun operating more openly in the north, even in areas quite close to Kabul.

For now, it is in the interest of regional power-holders in the north to minimize blatant use of force in confronting one another (or the central government). While this state of affairs has allowed the residents of northern and western Afghanistan some measure of respite, their sense of insecurity-their fear that any gains they make could be taken away arbitrarily-remains high.[32] While factional fighting and overt violence has decreased in areas outside the south and southeast, insecurity remains high because of the near absolute impunity with which regional strongmen are able to act. The rule of law and the justice system remain very weak in Afghanistan, so it is not enough for incidents of actual violence to decrease for the sense of insecurity to lessen.[33] The problem of impunity must first be addressed.

South of the southwest-northeast line described above, all three sources of direct insecurity torment ordinary Afghans. Warlords in southern and southeastern Afghanistan have assumed many senior government and security posts. After the Taliban were overthrown, many warlords took on the mantle of government authority by rebranding themselves as security forces without changing how they operate.[34]

Many observers, including the United Nations, the United States, and NATO, consider the narcotics trade as the gravest threat to the security of Afghanistan.[35] The illicit drug trade accounts for an estimated U.S.$2.7 billion annually, surpassing the government's official budget, and equaling nearly 40 percent of the country's legal gross domestic product.[36] As Barnett Rubin has put it, "the livelihoods of the people of this impoverished, devastated country are more dependent on illegal narcotics than any other country in the world."[37] However, Rubin points out that according to U.N. estimates nearly 80 percent of this income goes not to farmers, but to traffickers and heroin processors.[38]

Criminal gangs involved in the drug trade are a major source of violence and insecurity in Afghanistan, as their interests seem to transcend any particular ideology and focus on maintaining their ability to operate without any inhibitions or monitoring from the government or its international allies. Despite over U.S.$500 million dollars dedicated to the counter-narcotics campaign by the United States and the United Kingdom, drug production raged out of control in 2005, and there are strong indications that it will reach record highs in 2006.[39] This vast criminal enterprise undermines the rule of law, challenges the authority of the central government, and provides easy and massive funding for military groups operating independently of the central government.[40]

Both the insurgents and the regional warlords assuming government authority have benefited from Afghanistan's booming drug trade and the criminal networks it has spawned-raising fears that Afghanistan is turning into a narco-state.[41] There is a very strong belief among Afghans and outside observers that senior government officials, including police chiefs, are involved in the drug trade.[42] Even the Taliban, who had effectively stamped out poppy cultivation during their reign, are now cooperating with criminal networks and apparently using it to finance their military and political activity.

Another factor complicating the security situation is interference by Afghanistan's neighbors. Afghanistan's Central Asian neighbors-Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan-each have significant ethnic and economic interests in Afghanistan, while Iran and Pakistan have historically maintained unofficial zones of influence across their respective borders. Afghans throughout the country, and particularly in the south and southeast, in interviews with Human Rights Watch in December 2005, were adamant in blaming Pakistan for directly controlling, or at least sheltering, the forces responsible for destabilizing southern and southeastern Afghanistan.[43]

The proximity of Pakistan and its tribal areas (typically described as ungovernable or lawless) is one reason why insecurity in Afghanistan is markedly higher in the country's southern and southeastern areas. It is in these areas where the Taliban and warlord Gulbuddin Hekmatyar have historically centered their operations. Both groups are predominantly Pashtun and derive their strength from Pashtun tribes straddling the Afghan-Pakistani border. U.S.-led coalition forces have concentrated their anti-Taliban activity and the search for Al Qaeda operatives in this area, at times engaging in heavy clashes with opposition forces.

Nearly a third of Afghanistan's population lives in the country's southern and southeastern provinces. The south is the heartland of Afghanistan's Pashtun community and the cradle of the Taliban movement.[44] By all accounts and benchmarks, security has deteriorated sharply in this area over the past two years.[45] Opposition forces and well-armed criminal gangs operate extensively in this area, and the population receives little succor from the regional warlords nominally operating under government authority.

In past years, opposition attacks decreased markedly during the winter months, when cold weather hampered movement, particularly across the mountainous border to Pakistan. In 2006, the attacks have continued at an ever higher pace and intensity. As one tribal elder from Helmand province told Human Rights Watch:

The people have no rule of law, it's the rule of the gun. The Taliban will kill you, or the government will kill you-one is worse than the other. There is absolute oppression and terror-there is no peace here. Might is right, the gun rules.

After the fall of the Taliban, we were happy because the United States saved us from terrorism, we thought it would help us with aid. We had a good memory because the U.S. had helped [us] in the 1970s. Unfortunately, the situation is the reverse of what we hoped. Our people's hopes have turned to dust. This is because of poor management, the presence of the commanders who have been put in charge by the government.[46]

In 2004, a more robust and aggressive strategy by the coalition managed to push the opposition forces out of some of these areas, prompting the U.S. and Afghan governments to pronounce (again) that the Taliban were on the verge of defeat.[47] But in 2005, Taliban and other opposition forces changed tactics, away from direct confrontations and instead began focusing on civilians and civilian institutions, such as teachers, low-level bureaucrats, schools, and aid workers, an approach similar to that used by anti-U.S. forces in Iraq.[48] At least nine clerics were killed in Afghanistan in 2005.[49]

A particularly alarming development was the introduction of the previously uncommon tactic of suicide bombings. As one veteran Western observer of security conditions in Afghanistan explained, "Some of the new incidents are more serious, but overall incidents have not increased. But there is a new quality: terrorism against soft targets, suicide bombs in Kabul. There are more areas where the Taliban are active."[50] Most of these attacks have taken place in southern Afghanistan, with nearly twenty in Kandahar province alone.[51] A self-described spokesman for the Taliban, Mohammed Hanif, boasted to the Christian Science Monitor in February 2006: "I confirm that there are 200 to 250 fidayeen [dedicated soldiers] who are prepared to carry out suicide attacks, and the number is increasing day by day."[52]

It is unclear if this shift in tactics represents any real growth in the strength or popularity of the insurgency. But if the perpetrators of these attacks intended to intimidate the civilian population and disrupt the reconstruction and development process, they have by and large succeeded. Nearly all of the civilians we spoke with say they feel even more threatened than before, and they now express fear about moving in previously safe zones, such as city centers, which have become susceptible to attacks and bombings. A tribal elder from Khojaki district in northern Helmand province explained:

The Talibs target anyone working with the government. Every night there is the government of the Talibs. By day, the government can send maybe one or two motorcycles, that's all. It was better before the parliamentary elections [in September 2005].[53]

Education in Afghanistan and its Importance for Development

Five years ago, Afghanistan was the world's most distressing example of the failure to provide children with an education. The Taliban denied nearly all girls the right to attend school, and insecurity, poverty, and the abysmal quality of remaining schools left many boys without an education as well. Aside from refugees educated abroad and a miniscule number of girls able to attend clandestine home schools, the misogynistic rule of the Taliban left an entire generation of girls and young women illiterate.[54]

However, opposition to non-madrassa based, so-called modern, education and to girls' participation predates the Taliban, when it first captured international attention. Education for girls was historically nearly non-existent in rural Afghanistan and almost exclusively confined to the capital. In 1919 King Amanullah seized the Afghan throne and began a rapid expansion of the country's secular education system, directly threatening the clergy's centuries-old monopoly on traditional madrassa education for boys. Amanullah's experiment with a secular and modern education system, particularly as it addressed the education of girls, aroused protest from country's religious establishment, who eventually supported the king's overthrow. With Amanullah's ouster, educational reforms were significantly slowed and in some cases reversed. Nevertheless, over the course of the twentieth century, and in particular during King Mohammed Zahir's long reign between 1933 and 1973, Afghanistan's education system steadily expanded, while continuing to be influenced by demands from the country's conservative culture and religious authorities.[55]

After the Communist coup d'etat of 1978, the education system was dramatically revamped to reflect the governing ideology. The curriculum downgraded the importance of religion and emphasized Marxist-Leninism. The Communist's educational policies set off a serious backlash, as the religious establishment, assisted by the militant Islamic groups, cast schools as centers for Communist Party activity.[56] Schools became one of the first military targets for the mujahedin and the long war against the Soviet occupation.[57]

With the fall of the Communist government in 1992, the country was divided among warring factions, many of them religiously-inspired mujahedin groups ideologically opposed to modern education and to educating girls. Millions of Afghans fled the country, particularly the educated. Of the schools not destroyed by war, many were shuttered because of insecurity, the lack of teachers and teaching material, or simply poverty.

Education under the Taliban went from wretched to worse. The Taliban focused solely on religious studies for boys and denied nearly all girls the right to attend school.[58] The Afghan government and its foreign supporters often cite the rehabilitation of the Afghan school system and the number of children in school as one of the chief successes of the international effort in Afghanistan.[59] Since 2001, the participation of children and adults in education has improved dramatically and, as explained below, there is great demand. Afghanistan has one of the youngest populations on the planet-although exact numbers do not exist, an estimated 57 percent of the population is under the age of eighteen.[60] Unexpectedly large numbers showed up when schools reopened in 2002, and enrollments have increased every year since, with the Ministry of Education reporting that 5.2 million students were enrolled in grades one through twelve in 2005.[61] This includes, they told us, an estimated 1.82-1.95 million girls and women.[62] An additional 55,500-57,000 people, including 4,000-5,000 girls and women, were enrolled in vocational, Islamic, and teacher education programs, and 1.24 million people were enrolled in non-formal education.[63] These numbers represent a remarkable improvement from the Taliban era. Indeed,more Afghan children are in school today than at any other period in Afghanistan's history.[64]

Despite these improvements, the situation is far from what it could or should have been, particularly for girls. The Ministry of Education estimates that 40 percent of children aged six to eighteen, including the majority of primary school-age girls, were still out of school in 2005. Older girls have particularly low rates of enrollment: at the secondary level, just 24 percent of students were girls in 2005;[65] and the gross enrollment rate for girls in secondary education was only 5 percent in 2004, compared with 20 percent for boys.[66] In six of Afghanistan's then thirty-four provinces, girls made up 20 percent or less of the students officially enrolled in school in 2004-2005.[67] Even at the primary level, girls are not catching up: the gap in primary enrollment between boys and girls has remained more or less constant despite overall increases in enrollment.[68]

Enrollment also has varied tremendously by province and between urban and rural areas.[69] Many children in rural areas have no access to schools at all. Seventy-one percent of the population over age fifteen-including 86 percent of women-cannot read and write, one of the highest rates of illiteracy in the world.[70]

Moreover, not all enrolled children actually attend school or attend regularly. The Ministry of Education told Human Rights Watch that 10-13 percent of children drop out each year,[71] but true numbers may be far higher: the 2003 Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) found seven provinces in which more than 20 percent of girls enrolled in school had not attended at all in the last three days.[72] "Enrollment data is from the beginning of year so it does not reflect kids who drop out during the year," explained senior staff of an NGO that runs education programs in many parts of Afghanistan.[73] Staff of the Afghan Independent Human Rights Commissionoffered a specific example: "Traveling around, we've seen that the Ministry of Education's numbers of kids in school are not accurate in areas of Paktika."[74]

As low as they are, enrollment rates appear to have reached a plateau. The Ministry of Education's director of planning told Human Rights Watch that the ministry expects the total number of students to remain unchanged from the 2005-2006 to the 2006-2007 school years and for new enrollments to slow in 2008 as refugee returns level off.[75]

Reconstruction of the country's education infrastructure has nevertheless been unable to keep pace with demand. According to the Ministry of Education, there were 8,590 schools in Afghanistan in 2004-2005, of which 2,984 had a dedicated school building, 2,740 were "buildingless" (held in tents or in open air); and the remainder were held in mosques or rented rooms and buildings.[76]

Of these schools, far fewer admit girls than admit boys. Schools are officially designed as either a boys' school or girls' school, with 19 percent of schools designated as girls' schools.[77] Twenty-nine percent of Afghanistan's 415 educational districts have no designated girls' school at all.[78] Some schools may admit students of the opposite sex, however: according to Ministry of Education figures, about one third of the country's schools had students of both sexes enrolled in 2004-2005.[79] In total, the ministry's data indicate that 49 percent of Afghanistan's schools admitted girls at some level, compared with 86 percent of schools that admitted boys.[80]

According to the head of the Ministry of Education's planning department, ministry regulations allow co-education up to grade three and, in remote areas, grade nine.[81] But practice varies widely. For example, a teacher in Balkh province told Human Rights Watch that he did not know whether strict separation of girls and boys "is law but this is certainly a policy. It was not the case in the past. It only started with the mujahedin regime [in 1992]. It is not applied in private schools."[82]

Demand for separation also comes from local residents.[83] Some communities refuse even to allow girls to attend a school that ever has boys in it; others allow girls to go in a separate shift or allow very young girls to attend classes with boys.

Official figures may over-represent the number of functioning girls' schools. (As explained below, the number of functioning boys' schools is also likely overstated because of closures following attacks.) Human Rights Watch received information about two instances of new girls' schools not being used for their intended purpose. Woranga Safi, the then-director of secondary education department at the Ministry of Education, described an incident in Takhar province that she said was a typical example of provinces failing to give attention to female education:

A brand new school had been built according to a plan established by the Ministry of Education in Kabul in cooperation with the provincial administration. It was a school dedicated for girls' education. It worked for a few days. It was then "hijacked" by local authorities and turned into a school for boys. The girls could not return to the school[84]

In Kapisa province, Human Rights Watch visited a newly-built girls' school that police had taken over for their own use because girls from the local community did not attend it.[85]

Secondary education, for which girls and boy are separated, is far less available to girls than to boys, and Human Rights Watch heard reports of certain provinces having no secondary schools for girls at all. However, neither the Ministry of Education nor UNICEF were able to provide us with a listing of provinces without girls' secondary schools. Human Rights Watch visited a girls' secondary school in Paktia, one of the provinces that does. According to the school's principal, it was the only school in the province offering education to girls grade eight or higher, and fifty-four girls were enrolled in these grades, including sixteen in class ten. No girls were enrolled in grades eleven or twelve in 2005-2006.[86]

The Structure of Afghanistan's School System

Under Afghanistan's Constitution, education is compulsory and free from grades one through nine and free up to the undergraduate level of university.[87] Children begin grade one at age six or seven. Primary education consists of grades one through six, junior (or middle) secondary education grades seven through nine, and upper secondary education grades ten through twelve. Formal education options also include vocational education and teacher education (grades ten through fourteen) and Islamic education (grades seven through fourteen).

In "cold" areas, the school year begins after the Persian New Year in March; in "hot" areas, the school year begins in September. The school year usually lasts nine months, divided into two semesters, with a two-and-a-half month break at the end of the academic year. The school day is short, typically lasting from three to three-and-a-half hours, which allows teachers to work at other jobs or schools to operate multiple shifts.

In addition to formal schools run by the Ministry of Education, other forms of education are available in certain areas. This includes literacy programs, community-based schools, and accelerated learning programs which typically target, but are not limited to, girls who cannot go to a regular school. Accelerated learning programs educate children who have missed some years of school but seek to rejoin the formal education system by studying the formal curriculum at an accelerated pace. These programs may be administered by NGOs or the government, with the largest being the USAID-funded Afghanistan Funded Primary Education Program(APEP), implemented primarily through Afghan NGOs.

International donors have long played a role in education in Afghanistan, and, since the fall of the Taliban, education has been almost completely dependent on international support, provided directly to the government or to private contractors and NGOs. The largest international donors for education in Afghanistan are the United States (via USAID) and the World Bank. Other donors include Denmark, Ireland, Japan, the Netherlands, Sweden, the United Kingdom, UNESCO, and UNICEF. Donor money has gone to school construction and rehabilitation, textbook printing and distribution, teacher training, and school equipment such as tents, blackboards, and carpets. According to the Agency Coordinating Body For Afghan Relief (ACBAR), since 2002, NGOs have assisted in repairing or constructing around 3,000 school buildings and in training 27,500 teachers.[88] In light of the very high numbers of children outside the education system, the focus of donors and the Ministry of Education has been on primary education largely to the exclusion of secondary.

Education is universally recognized as critical for children's intellectual and social development, providing them with critical skills for leading productive lives as citizens and workers. Education is also central to the realization of other human rights.[89] For girls, moreover, access to education correlates strongly with later marriage and childbirth,[90] which in turn correlate strongly with improved health, including significantly reduced maternal mortality.

Education not only benefits the children themselves, it also benefits the country's development. It is now well-established that increasing girls' and women's access to education improves maternal and child health, improves their own children's access to education, and promotes economic growth.[91] For example, research has shown that an additional year of school for girls can reduce infant mortality by 5 to 10 percent, and that reducing the gender gap in education increases per capita income growth.[92] Indeed, studies have found greater returns through higher wages on school investments for girls than for boys, particularly for secondary education.[93]

The low numbers of girls receiving secondary education and higher education is especially troubling and carries profound consequences for the future participation of women in the social, economic, and political life of the country. Without higher levels of education, women's opportunities to secure skilled employment, gain leadership roles in local and national government, or to impart education as teachers themselves, are severely restricted. As one woman leader in Kandahar pointed out: "This young generation can be trained well but what about older girls? They will remain illiterate. An illiterate woman cannot be a teacher. How can she train the next generation?"[94] Some of the most important development benefits of girls' education for a country also take place at the secondary school level.[95]

III. Attacks on Schools, Teachers, and Students

The tactics of the Taliban have changed. Now there are attacks on mullahs and teachers. Things are much worse.

-A teacher from Kandahar province[96]

When President Karzai stated in March 2006 that some 100,000 Afghan children who had gone to school in 2003 and 2004 no longer went to school, he said that this was in part "because some two hundred schools that we built were torched or destroyed."[97]

In fact, the number of schools put out of commission is even higher. Listing schools that were closed in 2005, provincial and district education officials told us of at least forty-nine in Kandahar,[98] fourteen in Ghazni,[99] and eighty-six in Zabul.[100] In January 2006, the director of education for Helmand province told journalists that 165 schools had been closed for security reasons.[101] According to Nader Nadery, of the Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission, "more than three hundred schools have been burned or, for the major part, have been shut down. . . . Most of the schools have been closed because of the fear of attacks by Taliban and Al-Qaeda forces, and, due to the insecurity that the people in the region [feel], parents are refusing to send their kids to schools."[102]

Attacks against schools, teachers, and students rose markedly in late 2005 and the first half of 2006. Human Rights Watch recorded at least 204 reported physical attacks or attempted attacks (such as bombs planted but found before they exploded) on school buildings from January 1, 2005 to June 21,2006, based on reports to ANSO, the United Nations, the media, and our own interviews.[103] Of these attacks, 110 occurred in the first half of 2006. This represents a significant increase in attacks reported to ANSO or otherwise recorded by Human Rights Watch in previous years.[104] Although Human Rights Watch was not able to independently verify most of these reports, our count for 2006 is essentially consistent with that of the World Food Programme, which stated that as of June 19, 2006, 119 schools had been attacked in 2006, "seventy-two of them completely or partially burned, and twenty-five have been subject to threats."[105]

Who and Why

Schools in Afghanistan have historically been targets of violence directed at the central government or perceived foreign interference (and frequently, both). In the current environment, the perpetrators of attacks on teachers and schools, and their motives, vary.

In several cases that Human Rights Watch independently investigated, we were unable to determine with certainty who was behind the attacks or why schools and school personnel were targeted, but certain general conclusions are possible. As set out above, insecurity in Afghanistan has a variety of sources and the people we spoke with identified a combination of motives. These fall into three overlapping categories: first, opposition to the government and its international supporters by Taliban or other armed groups, chief among them veteran anti-government warlord Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, (and including, at times, regional warlords with local grievances and criminal groups trying to restrict government activity); second, ideological opposition to education other than that offered in madrassas (Islamic schools), and in particular opposition to girls' education; and third, opposition to the authority of the central government and the rule of law by criminal groups-particularly those in the narcotics trade-anxious to avoid interference with their activity.

In many instances opposition forces or criminals attack schools and teachers as easy to reach symbols of the government (and often the only sign of the government in the area). Armed oppostion groups have changed their tactics to attack "soft targets," that is, low level government employees and symbols of government presence.[106] Teachers and schools, often isolated in rural areas, and with little or no security, present perfect targets for such attacks.

Another method of frustrating government policies is to stymie development projects. Opposition groups have explicitly adopted this position in some instances and targeted development agencies and NGOs. In several recent instances, opposition forces have killed foreign and Afghan staffers of development groups. The Taliban are most often blamed for these attacks, but it seems that other groups, at times with local grievances, or criminal groups eager to keep government influence at bay, are also responsible. For instance, ANSO reported that on February 4, 2006, in Saydabad district of Wardak province, "unknown men distributed night letters [threatening letters often left in public places at night] in the area. The night letter asked Afghans to join jihad and not to work for foreign organizations and the Afghan government. There was a specific warning to drivers who are transporting goods for organizations and government that they will be face severe consequences if they continue."[107] It is possible that the Taliban issued this warning; on the other hand, the area is quite close to Kabul and is dominated by forces allied with Abdul Rabb al Rasul Sayyaf, a radical warlord with a history of abusive behavior and now a prominent member of the Afghan parliament.[108] Wardak was also the site of several attacks on schools in 2005, which a local government official there attributed to "[p]eople trying to stop the improvement of this place. They target schools because of improvement."[109] Such warnings and attacks serve to maintain or strengthen local forces by weakening government authority.

Some attacks appear to be the result of tribal or private disputes surrounding the local disbursement of resources, including schools. The location of a school in southern Kandahar province, for instance, set off a long-running dispute between two tribes vying for government assistance. When one tribe attacked the school built on territory of the other tribe, it reflected local grievances as well as opposition to the government's policies in that region.[110]

In other areas, schools are attacked not as symbols of government, but rather because they provide modern (that is, not solely religious) education, especially for girls and women.

In a March 25, 2006 statement issued by the self-styled spokesperson of the Taliban Leadership Council, Mohammed Hanif, the Taliban explicitly threatened to attack schools because of their curriculum:

In general, the present academic curriculum is influenced by the puppet administration and foreign invaders. The government has given teachers in primary and middle schools the task to openly deliver political lectures against the resistance put up by those who seek independence. . . . The use of the curriculum as a mouthpiece of the state will provoke the people against it. If schools are turned into centers of violence, the government is to blame for it.[111]

The statement went on to target girls' education directly: "Another matter worth pointing out is that failure to observe the Islamic veil at girls' schools, co-education and visits by the American forces to schools are not acceptable to any Afghan. Therefore, we are strongly opposed to it and cannot tolerate it."[112] Around the same time, however, Hanif told a journalist: "We have not threatened anybody except those who work for Christians and for foreigners in Afghanistan. . . . We have never killed any teacher or any student."[113] In fact, Human Rights Watch has documented many instances, set out in detail below, when Taliban attacks were directed at girls' schools exclusively, or explicitly targeted teachers and schools providing education to girls.

Similarly, on April 27, 2006, anti-government warlord Gulbuddin Hekmatyar reportedly issued a press statement vowing to continue jihad against foreign forces and stating that "now the infidel forces had been forming education system and syllabus for Afghans to divert our youth from Islam to Christianity."[114]

The rest of this section surveys cases of attacks on teachers, students, and school buildings in several provinces from 2004 to 2006 and the use of so-called night letters to terrorize teachers, students, and parents. It also discusses the impact of crime and impunity on education.

Attacks by Taliban and Warlords on Education in Southern and Southeastern Afghanistan

The following case studies document attacks on schools in eight provinces in south and southeastern Afghanistan. These are the areas where there have been the greatest of attacks on teachers, students, and schools. Notably absent are the provinces of Uruzgan and Paktika, which have high levels of insecurity and low levels of development, but where insecurity has made it extremely difficult to get accurate information.

Kandahar City and Province

Kandahar city and its eponymous province comprise the second most important area in the country after Kabul. The city is the economic, political, religious, and cultural center of the Pashtun belt in the south and was the de facto capital of the Taliban while they were in government. Since the Taliban's overthrow, the international community, led by the United States has maintained a significant military presence there and made efforts to develop the area's economy (since late 2005, Canadian forces have taken the lead in providing security for Kandahar). Nevertheless, increasing insecurity has significantly constrained much of the development work, limiting it by and large to the city limits.

A representative on the Kandahar provincial council provided her impression of the impact of rising insecurity on education, particularly for girls, in Kandahar in December 2005:

The security situation was fine, but during the last two years it is growing worse day by day. In the first three years there were a lot of girl students-everyone wanted to send their daughters to school. For example, in Argandob district [a conservative area], girls were ready, women teachers were ready. But when two or three schools were burned, then nobody wanted to send their girls to school after that.[115]

In 2004-2005, 19 percent of officially enrolled students in Kandahar province were girls.[116] Outside of the city, however, only 10 percent of enrolled students were girls, and no girls were enrolled in four of Kandahar's fifteen educational districts.[117] According to USAID, two hundred schools in Kandahar were closed for security reasons by early 2006.[118]

Girls' schools in Kandahar city, in the past relatively secure, came under attack in 2006. ANSO, U.N. sources, and the press reported the following attacks in the city at the end of 2005 and in 2006:

- December 27, 2005: a hand grenade was thrown at Mirwais Mina girls' school in district 7. The school was empty at the time, but the windows were blown out and the walls, roof, and doors damaged. A suspect was arrested in February 2006.[119]

- January 7, 2006: unidentified men tied up two school guards and set fire to a co-educational primary school in Loya Wiyala village just outside Kandahar city.[120] The attack followed threatening letters, according to provincial deputy police chief Colonel Abdul Hakim Angar.[121]

- January 8, 2006: men set on fire Qabial co-educational primary school in Kandahar city, after locking three janitors inside.[122] The men were rescued. According to provincial deputy education director Hayatollah Rafiqi, on the same day more than a dozen armed men also set fire to classrooms and school documents at Zeray primary school in Kandahar province.[123] As a result, female students were unable to take exams.[124]

- Early March 2006: a homemade bomb was left next to the house of a teacher at Zargona Girls' High School in Kandahar city.[125]

- April 18, 2006: night letters warning women and girls not to attend schools and offices were found in district 10.[126]

Human Rights Watch interviewed a number of education officials from rural districts in Kandahar who described attacks on schools in their areas.

Maruf District, Kandahar

In 2004, the Taliban aggressively campaigned to close the schools in Maruf district, Kandahar, a partially mountainous area on the border with Pakistan. According to an education official from the area, in 2003 "all the people of the community contributed and helped the schools . . . . People were sending kids to school. Then the people who had been through the difficulty of migration were very happy to send their children-girls and boys."[127] But the following year, he explained, the Taliban began to threaten and beat teachers, and shot a principal (mudir). They also threatened a school full of children. Around the same time, several schools were burned or blown up. The Taliban went from village to village, calling meetings at the mosque and ordering all schools to be closed. They were successful: all forty schools in the district closed in 2004 and did not open again in the 2005-2006 school year.[128]

In June 2004, around three hundred students were attending Sheikh Zai Middle School, located on the outskirts of a community in the mountains of Maruf district.[129] Girls attended grades one through four; boys went until class six. There were ten registered teachers but only six were present on the day the Taliban came in June 2004. That morning, a person came to the school and warned the head teacher that the Taliban were coming. The head teacher got on his motorbike and went to the district center to inform the authorities. In the meantime, members of the Taliban arrived at the school. According to a man from the district who spoke with the teachers and some of the students shortly thereafter, the Taliban "went to each class, took out their long knives . . . locked the children in two rooms [where the children] were severely beaten with sticks and asked, 'will you come to school now?'"

The six teachers later told residents what happened to them. According to a resident, the teachers told him that:

They were taken out of school, their eyes were tied, they were continually hit, and they were taken to the nearby mountains on foot. . . All six were separated and nobody knew where the other was. One by one the teachers were asked why they didn't obey what had been announced on radios and in the mosque. They said they hadn't heard about it and the only thing they wanted was to educate children. The Taliban asked them individually, "Why are you working for Mr. Bush and Karzai?" They said, "We are educating our children with books-we know nothing about Bush or Karzai, we are just educating our children." After that they were cruelly beaten and let go. . . .