Dedication

This report is dedicated to the families living in Khar Yalla, and, in particular, to Elimane Gueye (1956-2025), loving father and husband, who died in June 2025 of a prolonged illness that began after he was injured trying to build a sea wall to protect his family from coastal floods.

Summary

On the side of the busy highway that leads out of the city of Saint-Louis, in northwestern Senegal, is a site known as Khar Yalla. Its name means “waiting for God” in Wolof. Around 1,000 people have been living at the site, since 2016. They come from tightly knit, historic fishing communities on the Langue de Barbarie peninsula, located five kilometers from Khar Yalla, which is one of the most exposed places in Africa to sea level rise and other impacts of the climate crisis. A decade ago, the families lived in houses on the beach, within walking distance of their closest friends and relatives. Most men spent their days fishing, while most women cleaned, smoked, and sold the fish they brought back. But in 2015 and 2016, coastal floods destroyed their homes, making them internally displaced peoples (IDPs). Municipal authorities temporarily housed the displaced families in tents in the Langue de Barbarie, then moved them to Khar Yalla into houses that had been constructed for an earlier, failed planned relocation project that was meant to protect other families threatened by flooding. The families displaced by the 2015 and 2016 floods agreed to be moved to Khar Yalla, hoping that the site would offer temporary protection until they could rebuild on the Langue de Barbarie or be relocated by the government to new, permanent homes.

But as documented in this report—based on interviews with 101 people, including IDPs living in Khar Yalla, other members of their communities from the Langue de Barbarie, government officials, academics, civil society members, and other experts—Senegalese authorities still have not facilitated a durable solution for the IDPs through rights-respecting planned relocation or meaningfully consulted them about their needs and hopes for the future. Instead, for almost a decade, the Senegalese government has left the IDPs in a state of precarity denoted by Khar Yalla’s name, and in conditions that violate their economic, social, and cultural rights, including their rights to an adequate standard of living, adequate housing, education, health, and to take part in cultural life.

Khady Gueye’s experience is illustrative. In 2015, she was a 16-year-old star student, about to finish high school, when her home in the Langue de Barbarie was destroyed. After her family was displaced by floods, spent months in tents, and then moved to Khar Yalla, she left school. She could not afford to travel to her old one and struggled to access those closer to Khar Yalla. She also had to care for family members whose preexisting health conditions deteriorated after the family lost their home, including her younger sister, who had long been in ill health, and her father, who had acquired a disability several years prior due to injuries he sustained while trying to build a sea wall to protect the family’s home in the Langue de Barbarie. Her sister died soon after they arrived in Khar Yalla. Khady’s family had to use the only humanitarian aid the government ever provided them in Khar Yalla for the funeral. Khady is now a 26-year-old mother who shares a house with three bedrooms, a kitchen, and one toilet with 14 relatives. Her father passed away in June 2025, without ever having seen his family find a durable solution for their displacement. Khady and others have worked tirelessly to improve the living conditions in Khar Yalla. But after nearly a decade in limbo, Khady is growing desperate. “We feel forgotten by decisionmakers,” she said. “We’ve asked sometimes if the authorities consider us as human, as Senegalese. They are well aware of our situation. Most of them live nearby and pass by our homes every day. Why can’t they hear us?”

The living conditions Khady and others face in Khar Yalla violate their rights to adequate housing. There is severe overcrowding, most houses lack electricity, and there is no waste collection or disposal system. Every rainy season (June to September), Khar Yalla repeatedly floods, and septic water and garbage enter the houses. Additionally, households still have only the temporary, revocable occupation permits distributed by municipal authorities in 2016, which prohibit them from modifying the houses.

The people in Khar Yalla also endure other ongoing violations to their rights to an adequate standard of living, as well as their rights to education, health, and to take part in cultural life. Khar Yalla has no state-run, secular school, health clinic, or employment opportunities. There is no affordable transportation to schools, health care, or their jobs in the Saint-Louis city center or the Langue de Barbarie. Authorities have made no efforts to help the people in Khar Yalla retrain for other professions and thwarted the community’s own initiatives. The authorities have also done little to help the people in Khar Yalla with access to other income or direct provision of essentials such as food to ensure an adequate standard of living. As one woman in Khar Yalla told Human Rights Watch, “We have no support from the authorities, and when we tried to find our own solution, they stopped us.” Consequently, the people in Khar Yalla are dislocated from their culture, an estimated third of the children in Khar Yalla do not attend primary or secondary school, many people have foregone preventative care, and most breadwinners’ incomes have dropped to the point that families are often unable to put food on the table.

The families are living in protracted displacement in Khar Yalla because authorities have failed to facilitate one of the three possible settlement options identified as durable solutions in international guidance: dignified return, local integration at a site of temporary stay, or permanent relocation to a site where living conditions are comparable or better. The families in Khar Yalla cannot rebuild their homes in the Langue de Barbarie, because their land will soon become a no-build zone. Khar Yalla’s exposure to flooding and lack of essential services make it inappropriate for permanent human habitation, as Senegalese government and World Bank officials acknowledge. Thus, moving the IDPs to Khar Yalla did not constitute a relocation that could offer comparable living conditions to what the IDPs had lost, and the site is not appropriate for local integration. Moreover, authorities have actively prevented local integration by only giving the people in Khar Yalla revocable, temporary occupation permits for the houses and disrupting several of their attempts to improve the site or find in situ sources of employment. The families in Khar Yalla are not forced to live there, but they cannot afford to move elsewhere because of the depletion in income they have experienced since being displaced.

Meanwhile, the Senegalese government failed to include the Khar Yalla families in a planned relocation it is undertaking for other households from the same Langue de Barbarie communities, facing the same climate change impacts, including people who have not yet lost their homes. Coastal floods in 2017 and 2018 displaced hundreds more families from the Langue de Barbarie. In the aftermath, the Senegalese government requested and received a World Bank loan to launch the Saint Louis Recovery & Resilience Project (SERRP). Through SERRP, the government has now permanently relocated the families displaced in 2017 and 2018 to new, government-built houses in a site located 10 kilometers inland, called Djougop. The government is also relocating approximately 11,000 other people who have not yet been displaced but who currently live in the houses closest to the sea on the Langue de Barbarie. But authorities have left their fellow community members, who were displaced since 2015 and 2016, behind in Khar Yalla.

SERRP does not yet facilitate a viable durable solution for those being relocated through the program. Though a systematic analysis of SERRP is beyond the scope of this report, Human Rights Watch spoke to SERRP beneficiaries and local civil society leaders who criticized the consultation process and dissemination of information and described struggles to continue participating in their culture and earning an income from fishing. These and other concerns with SERRP notwithstanding, it offers a relocation site with several essential services that are absent in Khar Yalla, such as electricity, waste disposal, schooling, and in the future, a health clinic and food market. The government officials Human Rights Watch interviewed failed to provide credible explanations for why the families in Khar Yalla were left out of SERRP. Indeed, several local officials denied that these families had ever been displaced by climate hazards, even though it was the Saint-Louis municipal government that moved the families to Khar Yalla after the 2015 and 2016 floods.

Senegal is obligated under national and international law to respect and fulfill its people’s economic, social, and cultural rights and protect them from reasonably foreseeable risks to rights, including the impacts of sea level rise and other hazards intensified by climate change, in a way that does not violate their rights. Senegal is also required to facilitate durable solutions for internally displaced persons. It is laudable that the Senegalese government has proactively pursued strategies to protect climate displaced people, including planned relocation. Senegal has taken these issues more seriously than most other states. But its efforts should lead to durable solutions for those displaced by climate hazards, not protracted displacement leading to human rights violations, as has occurred for the IDPs in Khar Yalla.

As these families live through their ninth rainy season in Khar Yalla, at the time of writing, it is urgent that the government recognize that they were displaced by coastal floods in 2015 and 2016, meaningfully consult with them, and include them in an improved version of SERRP or facilitate another durable solution that ensures an adequate standard of living and respects their rights. In the interim, living conditions in Khar Yalla must be improved. Given the Saint-Louis municipal government’s inaction, intervention from the national government is urgently required.

To prevent future experiences like those of families in Khar Yalla, the Senegalese government should become the first African country to develop a national policy on internal planned relocation aimed at protecting the rights of internally displaced persons and facilitating durable solutions for them. It should also ratify the 2009 African Union Convention for the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons in Africa (Kampala Convention). By taking these actions, Senegal can become a regional leader in climate adaptation and protection for internally displaced communities.

The World Bank should reform its policies as well. In SERRP and the other climate-related planned relocation projects it has been involved in so far, the World Bank has applied policies designed for resettlements driven by development projects, such as dams and roads. But these policies do not reflect the unique nature of climate-related planned relocation. World Bank policies need to be replaced or updated to ensure that the climate-related planned relocations it funds are informed by consultation with impacted communities, based on comprehensive censuses, and anchored around the goal of protecting people and ensuring those living in protracted displacement can achieve a durable solution.

Recommendations

To the Senegal National Government

To the National Municipal Development Agency, Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development & National Committee on Climate Change, and Ministry of Territorial Communities, Planning and Development of Territories

For Khar Yalla

Together with regional and municipal authorities, plan relocation of the people living in Khar Yalla who were displaced from the Langue de Barbarie in 2015 and 2016, with their meaningful consultation and informed consent, to Djougop or another site where their economic, social, and cultural rights—including rights to an adequate standard of living, adequate housing, education, health, and culture—are respected and fulfilled.

Consistent with SERRP model, enable Khar Yalla families to choose between accepting new homes or receiving compensation for their old homes in the Langue de Barbarie.

Compensate Khar Yalla families for the economic and non-economic losses sustained during the nine years they have been in protracted displacement, cut off from fishing livelihoods.

Ensure consultation of women, older persons, and persons with disabilities.

In the absence of meaningful action by municipal authorities, dedicate maximum available resources to respect and fulfill the rights of the people in Khar Yalla while they await a permanent relocation elsewhere, including their rights to an adequate standard of living, adequate housing, health, and education.

Providing services and infrastructure: install electricity in homes and improve sanitation.

Ensuring homes are habitable: construct a dyke to protect homes from riverine flooding during the rainy season and resulting health risks, and support community-led planning to reduce overcrowding.

Insisting that municipal authorities provide the IDPs in Khar Yalla with secure tenure: authorize people to make necessary improvements to their houses and the site to address overcrowding, lack of shade, and other issues.

Facilitating access to work on-site: authorize the Khar Yalla women’s association to finish constructing their training center.

Formally recognize the Khar Yalla women's association as an implementation partner.

Ensuring access to essential services: provide free transportation or, with the Municipal Development Agency (ADM) and transportation unions, install bus stops near Khar Yalla and Djougop and subsidize or otherwise incentivize bus operators to transport passengers at both sites to city center and Langue de Barbarie. This is necessary to ensure access to essential services, including—

Nearby public schools;

Health care facilities, particularly for pregnant women, children, older people, and people with disabilities;

Culturally significant livelihoods; and

Other places necessary to realize their rights.

For national planning on planned relocation

Conduct and publicize a thorough review of past and ongoing planned relocation projects in Saint-Louis, including by documenting lessons learned from community members’ experiences through extensive consultations, and assessing the impacts of these projects on relocated persons’ housing, culture, education, health, and income.

Conduct a vulnerability and needs assessment of other communities in the Langue de Barbarie and elsewhere in Senegal who are displaced or at risk of displacement in the context of climate-related hazards, with particular focus on any communities who have self-identified as needing a planned relocation.

Prioritize currently already displaced communities such as Khar Yalla in future planned relocation decisions.

Develop a national climate-related planned relocation policy to protect rights of future communities facing sea level rise and other climate change impacts, that:

Is based on lessons learned from community members involved in prior planned relocation projects;

Is centered on protection, prioritizing people already in protracted displacement before people that have not yet lost their homes (e.g., by requiring a comprehensive census and integrated needs assessment for IDPs before scope of project is determined);

Conceptualizes planned relocation as a holistic process that recognizes non-economic dimensions, includes access to quality education and health care, as well as continued access to sites of livelihood and cultural importance;

Establishes transparency mechanisms, e.g., publishing rationale for decisions on scope of beneficiaries and information on funding allocation;

Requires authorities to establish robust criteria for planned relocation site selection that is safe from natural hazards, and that ensures living conditions are improved or equivalent to pre-displacement levels;

Requires substantial opportunities for impacted communities to give input on relocation process; and

Reflects fishing communities’ needs, including to ensure continued daily transport between the relocation site and site of origin.

To the Prime Minister and Parliament

Complete the ratification process for the AU Convention for the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons in Africa (“Kampala Convention”), which Senegal signed in 2009.

Implement national climate-related planned relocation policy and integrate it into the “Plan Sénégal” 2050 national development strategy and the Ministry of the Environment’s Vision 2050 plan; develop standard operating procedures (SOPs) to implement this policy, including institutional responsibilities and relevant coordination procedures.

Establish a climate-related planned relocation focal point with authority to coordinate across ministries and external actors.

Include climate-related planned relocation, and marginalized people’s perspectives thereof, in all related national planning efforts, including on climate change adaptation, disaster risk reduction, and sustainable development.

Pass legislation implementing the rights codified under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) into domestic law.

To the Governor and Prefect of Saint-Louis

Together with municipal authorities, prioritize timely, iterative consultation with people in Khar Yalla, and civil society partners, on future decisions impacting them, including by:

Meeting with working groups coordinated by Forum Civil;

Conducting a census to determine the number of households and individuals displaced by 2015 and 2016 flood currently residing in Khar Yalla; and

Undertaking a comprehensive needs assessment of people in Khar Yalla, on the full spectrum of rights, including rights to adequate housing, education, health, and taking part in cultural life.

Support and provide oversight of municipal authorities’ implementation of the above recommendations.

Together with ADM and other relevant national authorities, provide safe storage system for fishing boats and other equipment at the Langue de Barbarie for use by fisherfolk based in Khar Yalla and Djougop.

To the Saint-Louis Municipal Government (Mayor of Saint-Louis; Saint-Louis Municipal Development Agency)

Inform municipal officials that the families in Khar Yalla were displaced by the 2015 and 2016 coastal floods and have been left in limbo for nearly a decade.

- Together with regional and national authorities, support municipal and regional actors to implement above recommendation to facilitate rights-respecting relocation of IDPs in Khar Yalla to Djougop or another site.

Work with municipal and regional authorities to implement the above short-term recommendations to protect the rights of people in Khar Yalla while their planned relocation to Djougop or another site is being completed.

To the World Bank

If requested by the Senegalese government, extend SERRP funding or provide new funding, as needed, to facilitate rights-respecting planned relocation to Djougop or another site for the people in Khar Yalla, who were displaced from the Langue de Barbarie in 2015 and 2016.

Request national, regional and municipal authorities to construct bus stops and incentivize transportation to Khar Yalla and Djougop.

Compile and publicize lessons learned through SERRP and other climate-related planned relocations.

Build on compiled lessons and on guiding principles articulated in the World Bank’s West Africa Coastal Areas Resilience Investment Project Appraisal Document (PAD) Annex 9 “Community Development, Resilience, And Decision Making” to develop a new standalone policy on climate-related planned relocation or add an annex to existing policy on involuntary resettlement (OP 4.12, now ESS5) which operates under a different logic. This new climate focused policy or annex should:

Reflect the unique nature of climate-related planned relocation of entire communities;

Require grantees to develop census-taking and beneficiary identification approaches that prioritize those most in need of protection and a durable solution, including those who are living in protracted displacement and have experienced the most serious consequences of displacement for longest, in addition to those at risk of future displacement who have not yet lost their homes;

Include mechanisms for climate displaced communities—as opposed to their governments—to directly request planned relocation support;

Require grantees to conduct meaningful consultation with and incorporate views of all impacted communities, ensuring all adaptation decisions are driven by their needs.

Methodology

This report describes the human rights violations experienced by the people living in the Khar Yalla site in Saint-Louis, Senegal, to tell their hitherto overlooked stories of living in protracted displacement after climate-related disasters, draw attention to the dire conditions they are facing that require immediate resolution, and identify lessons to inform future planned relocations that the Senegalese government and World Bank may undertake.

This report is based on 101 interviews that Human Rights Watch conducted from October 2024 to July 2025, in-person or by videoconference or telephone. In April 2025, Human Rights Watch spoke to 69 people living in the Langue de Barbarie (origin site), Khar Yalla (IDP site), and Djougop (relocation site), through individual interviews and focus groups in each site. These interviews were coordinated by local partner Lumière Synergie pour le Développement (LSD), a Senegalese NGO focused on climate justice and international financial institution accountability. In Khar Yalla, Human Rights Watch conducted separate focus groups for men and women. All interviewees were over 18 years old, ranging in age from 19 to 74. Additionally, Human Rights Watch interviewed 7 local, regional, and national government officials in-person, and 25 experts, including officials from the World Bank and United Nations agencies, academics, journalists, climate activists, and representatives of NGOs familiar with planned relocation, climate adaptation, and issues facing fishing communities in Senegal. All interviews were conducted in safe locations, in French, Wolof, or English (LSD staff provided Wolof and French interpretation). All participants were informed about the purpose of the individual interviews and focus groups, the ways that their responses may be used, and that their participation is voluntary, and received no payment, service, or other personal benefit. LSD covered community members’ expenses to travel to interview locations, as they would not have had the financial means to do so themselves. The names of some community members interviewed for this report have been disguised with names and initials (which do not reflect real names), in the interest of the security of the individuals concerned.

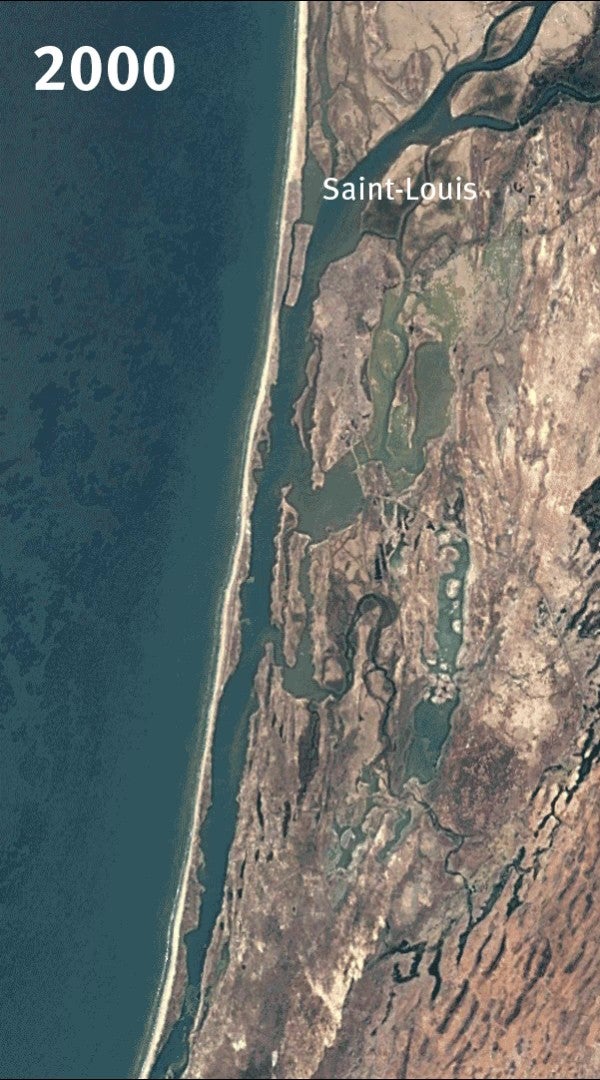

Human Rights Watch also analyzed dozens of satellite images covering more than 15 years of the different sites in this context; documents and data from the Senegalese government, UN agencies, the World Bank, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, NGOs; and academic publications.

In June and July 2025, Human Rights Watch sent letters to the World Bank, Saint-Louis local and regional actors (the Governor, Prefect, Mayor, Municipal Development Agency, and regional Environmental Ministry), and several national ministries (the Municipal Development Agency (ADM), Environmental Ministry, and Ministry of Local Authorities & Territorial Planning). At the time of publication, the World Bank and ADM had replied. The letters and responses are included in the Annex and referenced throughout the report.

Background

Planned Relocation as a Potential Durable Solution to Climate Displacement

While urgent action by all governments can still mitigate the worst climate change scenarios, extreme weather events will become stronger and global mean sea level “will continue to rise over the 21st century,” according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).[1] Sudden- and slow-onset disasters have already displaced millions of people within their countries’ borders. In 2024 alone, 45.5 million people were internally displaced by floods, storms, and other weather-related disasters.[2] This number will likely rise as the climate crisis accelerates.[3]

According to the UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, the Kampala Convention (which Senegal has signed but not ratified), and other international guidance, durable solutions to displacement can be achieved through three settlement options: dignified return to the person’s origin site, local integration in the area where a person seeks refuge, or relocation to another site that offers comparable or better living conditions.[4] If implemented in a human rights-respecting manner, planned relocation can facilitate a durable solution for those displaced by climate-related disasters, or at risk of future displacement.[5] In a planned relocation, an entire community moves collectively and permanently to a shared destination site that is less exposed to current and anticipated climate-related hazards.[6] Such planned relocations are driven not just by sea level rise and other visible effects of the climate crisis, but also by demographic, political-economic, and socio-cultural factors.[7] Under international guidance, planned relocations are considered a measure of last resort, pursued once efforts to adapt in place have been exhausted.[8]

Over 400 planned relocations have already taken place or are ongoing worldwide in response to disasters.[9] IPCC scientists predict that more will become necessary as the climate crisis intensifies.[10] Some relocations are initiated by communities.[11] Others are carried out by governments, with support from international financial institutions.[12] Planned relocations entail high financial costs and even higher emotional, cultural, and other costs to those who are relocated.[13] Well-executed planned relocations can enable displaced peoples to get back on their feet and build towards a future safer from climate hazards and other risks to their human rights.[14] But when poorly carried out, they can pose profound risks to rights.[15]

Climate Change Impacts and Displacement in Saint-Louis, Senegal

Senegal is exposed to multiple slow-onset effects of climate change, particularly sea level rise and other impacts to its long coastline.[16] Thousands of Senegalese people have already been displaced by storm surges that are likely to intensify as the climate crisis accelerates.[17] The city of Saint-Louis, a UNESCO World Heritage site that was formerly the colonial capital of Senegal and is now the capital of Senegal’s northwest Saint-Louis region, is one of the most exposed African cities to rising sea levels and coastal erosion.[18] One of its most at-risk areas is the Langue de Barbarie, a narrow, 40-kilometer-long peninsula that is around two meters above sea level and sits between the Atlantic Ocean and Senegal River.[19] On the peninsula, approximately 80,000 people live in several densely populated neighborhoods—Goxu Mbacc, Ndar Toute, Santhiaba, and Guet Ndar—which have been central to West Africa’s artisanal fishing sector for centuries.[20] The beaches of the peninsula are filled with brightly painted fishing boats, called pirogues, as well as piles of fishing nets, concrete barrels used to dry fish, and shelters where fisherfolk rest, eat, and repair nets and boat engines between trips on the sea.

Around two-thirds of the city of Saint-Louis is “prone to flooding in case of high tide, river discharge or heavy rainfall.”[21] Since 2010, increasingly severe and frequent storm surges and swells have hit the Langue de Barbarie.[22] In early 2015 and late 2016, coastal floods hit the Goxu Mbacc and Guet Ndar neighborhoods, destroying approximately 80 houses, as well as fishing boats and materials.[23] The families impacted by these floods are those still living in Khar Yalla today.[24] A subsequent coastal flood in August 2017 displaced around 199 families (approximately 2000 people), destroying houses, a school, a mosque, and dozens of fishing boats.[25] And in February 2018, around 59 families (around 590 people) lost their homes in yet another coastal flood.[26]

It has become increasingly difficult for fisherfolk to make an income in the Langue de Barbarie. Marked increases in coastal erosion, salinization, sea level rise, and fluctuations in water temperature and currents are reportedly linked to depletions in fish stocks and diversity, and have made it more dangerous to fish and harder to bring home enough fish to sell.[27] “I have personally seen the impacts of climate change, said Papa Nale Diop, an older fisherman.[28] “We don’t have fish at the time we are hoping for. And with the level of the sea rising a lot, we’ve had so many accidents at sea.”[29] Mame Mousse Ndiaye, a 40-year-0ld fisherman, remarked, “Previously, we had more fish at this time of year. Before, we understood the sea, and we used to have a lot of fish. Now we have more problems understanding.”[30] These climate-related hazards and their consequences on fisherfolk’s safety and livelihoods have been exacerbated by overfishing by foreign ships,[31] offshore oil and gas exploitation,[32] and a failed government flood mitigation project to dig an outlet through the Langue de Barbarie.[33]

Planned Relocation in Saint-Louis

In response to the challenges facing the Langue de Barbarie fishing communities, some community members have chosen to leave. Many of Human Rights Watch’s interviewees reported that male relatives or friends had planned or attempted irregular migration by boat (including in their own pirogues) to Spain’s Canary Islands, in part because they believed they could no longer make an income from fishing in the Langue de Barbarie.[34] A few wealthier families have built homes inland to protect themselves from coastal floods.[35]

But most of those living in the Langue de Barbarie whom Human Rights Watch interviewed expressed a desire to stay and did not intend to move inland before floods destroyed their homes and they were required to do so.[36] Other research has similar findings. For instance, academic research based on in-depth interviews and focus groups also found that permanently leaving the Langue de Barbarie has been “[h]istorically … out-of-the-question culturally.”[37] And 83 per cent of respondents to a 2023 survey conducted by Caritas International in Guet Ndar had not left their homes and had no intention to do so.[38]

By contrast, since at least the mid-2000s, Senegalese authorities have considered planned relocations of populations from the Langue de Barbarie in the name of protecting the peninsula’s residents from floods and other climate hazards.[39] In 2010, the city of Saint-Louis, led at the time by Mayor Cheikh Bamba Dièye, launched a project to plan relocation of flood-prone households in Guet Ndar and an informal settlement in Saint-Louis called Diaminar further inland, to the Khar Yalla site.[40] The project was funded by Japan, with technical assistance from the UN Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat).[41] A 2022 report from the national Municipal Development Agency (ADM) described the project as being “part of the strategic coastal retreat” from the Langue de Barbarie.[42] UN-Habitat prepared the Khar Yalla site for the relocation and built houses for the intended beneficiaries from Guet Ndar and Diaminar.[43] But the municipality failed to provide water or electricity at the site. The beneficiaries never relocated to Khar Yalla because they preferred to stay in their homes.[44] In 2016, Saint-Louis municipal authorities moved[45] the families displaced by the 2015 and 2016 coastal floods from tents in the Langue de Barbarie into the houses in Khar Yalla built for the prior, failed planned relocation project.[46]

Meanwhile, through SERRP, the Senegalese government is currently undertaking a larger-scale planned relocation that aims to both provide a reactive solution for people already displaced and an anticipatory strategy to prevent future displacement.[47] SERRP is partially funded by World Bank loans, the first of which Senegal obtained after the 2017 and 2018 coastal floods.[48] The relocation encompasses the IDPs from the 2017 and 2018 floods and around 11,000 people who are not yet displaced, but who reside in a 20-meter-by-3.6-kilometer band on the Langue de Barbarie, which the Senegalese authorities have designated as “high-risk [and] extremely vulnerable to coastal erosion.”[49] Residents of this 20-meter band can choose to be relocated to Djougop, a site ten kilometers inland, in neighboring Gandon Municipality, or receive compensation for their house in the Langue de Barbarie and find accommodation elsewhere.[50] The government’s stated plan is to demolish their homes after they leave and make the 20-meter band a no-build zone, with natural vegetation.[51]

Djougop is meant to have around 5,000 houses, a school, market, health clinic, and other services once the site is completed (projected December 2026).[52] As of February 2025, 4,500 people have been relocated to 167 completed houses in Djougop.[53] Construction of other infrastructure has begun but is not yet completed, as Human Rights Watch observed on-the-ground. As discussed further in the next section, the families displaced in 2015 and 2016 and moved to Khar Yalla were not included in SERRP.

I. Displaced by Floods to Khar Yalla

“The government said, ‘You’ll stay [in Khar Yalla] for a little while, and then we’ll find a solution that will enable you to go somewhere else’ … Now, almost 10 years later, the population is still there, with absolutely nothing.”[54]

2015 and 2016 Floods and Resulting Displacement

The people living in Khar Yalla today were moved there after they lost their houses on the Langue de Barbarie in coastal floods that hit the peninsula in early 2015 and late 2016.[55] Government data on the damage caused by these floods is scarce. But according to Iba Diagne, a 50-year-old, retired teacher and locally elected president of the northernmost fishing neighborhood, Goxu Mbacc, the 2015 flood destroyed 33 houses in his neighborhood, and the 2016 flood demolished approximately 50 houses in Guet Ndar, the southernmost neighborhood.[56] Diagne explained to Human Rights Watch that 80 per cent of the people who were moved to Khar Yalla in 2016 were from Goxu Mbacc, and included some of his former students.[57]

In both floods, the impacted families had little warning of the disaster and lost most of their possessions. “The sea destroyed our whole house and everything we had,” said Cheikh Sere, a 32-year-old teacher, now living in Khar Yalla.[58] “My mother refused to leave the house because she was old. We just had time to get her out before the flood came and destroyed all we had,” recounted one woman in Khar Yalla from Guet Ndar.[59] Thiare Fall, a 69-year-old woman in Khar Yalla, recalled, “After the floods, we had nothing left. We didn’t even have shoes when we left the house.”[60]

The families displaced by both the 2015 and 2016 floods were housed in tents provided by the authorities on a sports field in the Langue de Barbarie until late 2016.[61] During this time, they did not have adequate sanitation or clean drinking water, and their tents repeatedly flooded, destroying many of the possessions they had salvaged during the coastal floods.[62] “We had to do everything in the tents—cooking, bathing relieving ourselves—and we slept alongside our animals,” recalled Khady Gueye.[63] In October 2015, several of the displaced families protested outside the Saint-Louis mayor’s office, demanding assistance.[64] In late 2016, the mayor of Saint-Louis, Mansour Faye, and the then prefect of Saint-Louis, moved the displaced families to Khar Yalla.[65]

Origins of Khar Yalla Site

The Khar Yalla site to which the displaced families were moved had been built as part of a failed planned relocation project that was meant to model how to protect urban populations from climate-related hazards.[66] In 2009, the municipality of Saint-Louis requested foreign assistance to “relocate vulnerable populations living in flood-prone areas to safer sites.”[67] The Japanese government provided US$2 million and asked UN-Habitat to execute the project with the municipality.[68] The original goal was to move 150 households from Guet Ndar on the Langue de Barbarie and Diaminar—a flood-prone informal settlement on the mainland—into modular, prefabricated houses that UN-Habitat would construct on a site protected from flooding and close enough to the sea for inhabitants to continue their fishing livelihoods.[69]

But the project did not succeed. Its implementors chose Khar Yalla as the relocation site,[70] even though they knew at the time that it was flood-prone.[71] Ultimately, half the project’s funds went to raising the level of the housing foundations, leaving UN-Habitat with enough resources to build just under half of the originally planned number of houses.[72] Even then, the project was never completed. The intended beneficiaries from Guet Ndar and Diaminar never moved in, because while UN-Habitat upheld its side of the agreement and finished 68 houses in 2013, the municipality did not fulfill the responsibilities it had agreed to: providing a number of public and social services in Khar Yalla.[73] UN Habitat ended its involvement. The authorities did not repurpose the houses or authorize anyone else to live in them until 2016.[74]

Failures Unresolved, No Consultations

After moving the families displaced from the Langue de Barbarie in 2015 and 2016 to Khar Yalla, municipal authorities provided them with some assistance upon their arrival. Authorities divided families among the houses built for the prior, failed planned relocation project, and gave each household a temporary occupation permit, as well as “100,000 francs CFA[75] [around US$175], two 50 kg bags of rice, a 5 [liter] can of oil, two chairs, one mattress and one mat.”[76]

But, as discussed further in the following sections, municipal authorities did not rectify the failures of the earlier planned relocation project. Namely, the municipality still did not provide water, electricity, or other public and social services in Khar Yalla when it moved the families displaced in the 2015 and 2016 floods there.[77] Nor did authorities provide protections against flooding.[78] Furthermore, at the time of writing, the authorities had not consulted with the displaced people about their situation. Numerous people living in Khar Yalla recalled to Human Rights Watch that the authorities had assured them that they would only have to stay in Khar Yalla temporarily, until a more permanent solution was found for them.[79] They said that the authorities have never asked them about their needs, and that their primary interactions with officials occur ahead of elections, when politicians make unkept promises about improving conditions in Khar Yalla.[80]

II. Inadequate Housing in Khar Yalla

“The way we live in Khar Yalla is inhumane. We need solutions.”[81]

Senegalese authorities’ neglect of the displaced people in Khar Yalla for nearly a decade violates their economic, social, and cultural rights essential to an adequate standard of living, particularly their right to adequate housing. Several of the criteria that makes housing adequate under international human rights law are not met in Khar Yalla: habitability; availability of services, materials, facilities and infrastructure; security of tenure; and, as addressed in Section III, location with access to employment opportunities, schools, and healthcare services.[82] Municipal authorities have inhibited attempts by the families in Khar Yalla to improve conditions at the site.[83]

Uninhabitable Housing

Severe overcrowding makes the housing in Khar Yalla uninhabitable. Around 1,000 people are spread across just 68 houses.[84] Households can include multiple families and range from 10 to 35 people, sharing one kitchen, one toilet, three rooms, and a courtyard.[85] The houses were not designed to accomodate households of this size. Many families reported that they are forced to use their kitchen as an additional bedroom, given the lack of space, and to cook outside in the courtyard, where many keep livestock to protect them from theft.[86] This leads to sanitation issues.[87] In one house Human Rights Watch visited, 18 people who inhabit the space have to use the courtyard as a kitchen, where their three goats and five chickens also feed and defecate.

Overcrowding has become progressively worse over the nine years that the families in Khar Yalla have been living—and growing in size—in the site.[88] Mbaye F. is one of several people in Khar Yalla whose house is too crowded to accommodate her family.[89] She shares a house with 28 people from three different but related families and has to rent separate accommodation outside of Khar Yalla where she sleeps with her eight children.[90]

Every rainy season (June to September, approximately), the houses in Khar Yalla flood repeatedly, leading to health risks.[91] Satellite imagery analyzed by Human Rights Watch shows that, almost every year towards the end of the rainy season, the same flooding scenario repeats itself: water coming from the south, around the Diouk neighborhood, creates a passage to the south of the Khar Yalla neighborhood and flows into the floodplain around the Khar Yalla site. Several women explained that during storms, the families in Khar Yalla try and protect themselves with sandbags and by digging trenches to facilitate drainage.[92] But these efforts do not stop water from flooding the spaces between their houses or from entering their houses.[93] The aluminum sheets of the roofs get damaged during storms and leak; floodwater also frequently mixes with wastewater from septic tanks, which poses severe risks to residents’ health.[94] Residents reported increases in rashes, malaria, and other illnesses during the rainy season.[95] As one woman noted, when it floods, children in Khar Yalla “want to have fun and play in the water, but after they have health problems, like rashes and skin conditions.”[96] Khady Gueye explained that after storms, “The water turns green after some time and brings microbes that cause small rashes on the children. My youngest child gets lots of sores on his head during the rainy season.”[97] She added that older people are also particularly prone to health problems during the rainy season in Khar Yalla. “We brought a lot of older people back to Guet Ndar [to live with relatives], because it’s not healthy to live here.”[98] Khady was one of numerous residents who expressed their frustration to Human Rights Watch that after having been displaced by floods from the Langue de Barbarie, they still had to face the impact of floods. “We came from a place with floods and here we have floods,” she said.[99]

Lack of Services and Infrastructure

Water, Waste Disposal and Sanitation

Until 2022, the houses in Khar Yalla had no pipe-borne water, and the entire population of the site had to share one tap.[100] As discussed above, families in Khar Yalla report that septic water leaks into their water supply during heavy flooding. While other parts of Saint-Louis have waste collection systems managed by the state,[101] Khar Yalla has no system for disposing of household waste or wastewater.[102] Families dump their household waste into an expanse of dirt located past their houses and mosque. During the rainy season, flooding brings waste back into their houses; the wind does the same in the dry season.[103] This poses health risks: as the Senegalese NGO Rencontre Africaine pour la Défense des Droits de l'Homme (RADDHO) explains in a recent report on Khar Yalla, the population “live[s] or coexist[s] with household waste that is neither collected nor buried. This remains a constant danger to the health of the population.”[104]

Lack of Electricity

As of July 19, 2025, all but one house in Khar Yalla lacks electricity,[105] which has numerous negative consequences for Khar Yalla residents’ sense of physical safety, education, incomes, and food security. Multiple residents reported that they feared leaving their houses when it is dark.[106] Several shared that they had experienced thefts at night, and one mother described that her daughter was once assaulted when she went outside in the evening.[107] Additionally, “At night we don’t have lights for kids to be able to study,” explained Inda Diaw, a 65-year-old mother of eight.[108] Most residents felt they had no choice but to purchase solar units to provide their houses with some amount of energy, which cost 500,000-700,000 CFA (US$860-1,200), a heavy financial burden, particularly for families who have only precarious tenure over their houses.[109] A unit can power just a few devices—such as a small television and a couple of lamps—but cannot sustain a refrigerator or freezer, forcing families to buy ice to preserve their food.[110] The lack of electricity makes it much harder for families to store and preserve food, particularly the vegetables their family members buy in markets at the Langue de Barbarie and the fresh fish products they catch, which have historically been a no-cost staple of their complete diets.[111] As a result, families’ food-related expenses and food insecurity have increased since they were moved to Khar Yalla.[112]

Insecure Housing Tenure

UN-Habitat intended that the houses in Khar Yalla would be permanent dwellings that families could “expand to fit their needs,”[113] but the people in Khar Yalla are not allowed to make such improvements. The only form of tenure that the people in Khar Yalla have is the temporary occupation permits the Saint-Louis mayor’s office issued to them in 2016, which are revocable by the mayor.[114] According to community leaders, the permits also prohibit the people in Khar Yalla from adding rooms or other features to their houses that would alleviate the severe overcrowding or other issues they face.[115]

Khar Yalla families report that local authorities have blocked their efforts to improve their living conditions. For instance, families living in Khar Yalla asked municipal authorities for permission to increase the height of their walls to improve safety and privacy, and to plant trees to provide shade, as temperatures can approach 38° C (100° F) in Saint-Louis, and Khar Yalla lacks the sea breeze they had on the Langue de Barbarie to cool things down.[116] But families were denied permission to take these actions.[117] Their insecure tenure leaves them in a state of limbo. “We can’t be temporary for over ten years,” said Khady Gueye.[118] “I don’t want to live here,” said Mbaye F., “but we should have the right to build on more rooms for our children. But we’re afraid that if we did that, we would be evicted.”[119] One focus group participant said, “We lost everything [in the floods] and now we can’t live permanently in Khar Yalla.”[120]

By contrast, many of the people in Khar Yalla owned their houses in the Langue de Barbarie that were destroyed by floods,[121] and, as Khady Gueye recalled, her house and all the houses in her neighborhood had electricity and running water.[122]

III. Khar Yalla Site Is Cut Off from Education, Health Care, Culture and Livelihoods

“Before, when we were first told about Khar Yalla, we hoped to have a better life. But I do not have access to the life I had before, to a school or a hospital. Now I think life is not better here.”[123]

When the people in Khar Yalla lived in the Langue de Barbarie, they could walk to their work in the fishing sector, to school, and a hospital.[124] By contrast, Khar Yalla has no essential services or employment opportunities. It is five kilometers from the Langue de Barbarie, to which most adults still commute daily to maintain their livelihoods in the fishing sector.[125] The closest primary and secondary schools and health clinic that the people in Khar Yalla can access are 2.5 kilometers away in a neighborhood called Ngallèle; the nearest hospital is around five kilometers away, close to the Langue de Barbarie.[126]

These distances pose greater challenges than might appear on paper. The displaced people living in Khar Yalla cannot afford cars, and they report feeling unsafe when walking after dark between Khar Yalla and the city of Saint-Louis or Ngallèle.[127] There is no public transportation in the Saint-Louis region; the private buses and taxis people must rely on are costly and “unpredictable.”[128] Due to difficulties accessing essential services and their livelihoods, many people reported being unable to access emergency or preventative health care; many breadwinners in Khar Yalla can no longer make sufficient income through their traditional fishing livelihoods to support their families; many school-age children in Khar Yalla do not attend school; and all of the families in Khar Yalla have been cut off from their loved ones and centuries-old communities on the Langue de Barbarie.[129]

Human Rights Watch is not aware of any steps the government has taken to facilitate access to schools, health clinics, or the Langue de Barbarie for the people in Khar Yalla, or to provide education and health care services at the site or retrain them for jobs outside the fishing sector. Indeed, in Khar Yalla, municipal authorities have impeded the community’s own retraining initiatives. These actions and omissions by the government have contributed to the violations of their rights to an adequate standard of living, education, health, and to take part in cultural life.

Lack of Access to Education, Health Care and Culture

“When people get sick, have to go to school, buy food … they have to go to Saint-Louis. There’s none of that here.”[130]

Education

The community runs its own religious school for young children, but there is no state-run school in Khar Yalla, and community leaders estimate that today, a third of children of primary and secondary school age do not attend secular school.[131] Families cannot afford transportation fees to public schools or tuition fees to nearby private schools or need their children’s support to add to the family’s income or look after younger siblings, while their parents work all day at the Langue de Barbarie.[132] Mbaye F. can only afford transportation fees for three of her eight children to attend school, and relies on the income her other five children earn.[133] “Three of my children have stopped school all together,” Thiare Fall told Human Rights Watch, adding, “two of my daughters have struggled to continue their education here because transportation is too expensive and school is very far away.”[134] “When you're in a poor family, instead of paying the costs for one person to go to school, the parents prefer to spend it on household needs,” explained Khady Gueye.[135] Fatimata D. was about to finish high school when the floods destroyed her house and never completed her schooling, like Khady.[136] Now 26, Fatimata notes, “I always regret this, because I think education is a good thing for women. It provides opportunities that I can’t have in Khar Yalla.”[137] Ndaga Gueye, aged 27, managed to get into a local university but then had to leave after one year: “With my family’s income decreasing,” he said, “I had no choice but to abandon school and help my family earn money ... Young people feel like the government brought us here and then abandoned us.”[138]

Those young adults who have managed to remain in school struggle to keep up with their schoolwork because of the long commute to school. It can take Ousmane T., a 19-year-old student, hours to get to and from school, and if he is too late, his teachers refuse to let him in.[139] Because his commute leaves him with so little time for his homework, he noted, “I always dreamed of becoming a doctor, but I had to abandon that dream.”[140]

Health Care

The closest health clinic to Khar Yalla only offers vaccinations and non-emergency care.[141] For maternal health care, treatment of chronic illnesses, such as diabetes, and emergency services, people must travel five kilometers to the hospital in Saint-Louis. An ambulance can cost up to 25,000 CFA.[142]

Human Rights Watch heard from several people in Khar Yalla about times when they or others could not access health care during emergencies or routine care. A woman with breathing problems, who did not have enough money to go to the hospital, recently died in Khar Yalla.[143] Khady Gueye’s family did not have the money to take her now-deceased sister or father to the hospital for treatment for their illnesses. Of her sister, she noted, “By the time we could take her to the hospital, it was too late.”[144] Human Rights Watch spoke to a 33-year-old woman who had to give birth in the three-room house she shares with 28 people, without privacy or medical help.[145] She went into labor at night, when transportation is hardest to access, and while her husband and relatives were away working. The mother and baby survived, but her experience was harrowing. One 68-year-old woman with diabetes, reported that when they lived in Goxu Mbacc, she would routinely go to the doctor to get her blood sugar monitored and receive medications, but she has no access to health care in Khar Yalla and now she cannot afford the transportation fees to access treatment in other areas.[146] RADDHO has documented that there are no proactive efforts by the authorities to fill the gap by providing basic health care such as vaccinations for children or prenatal care in Khar Yalla.[147]

Dislocated from Communities and Culture

The Langue de Barbarie communities from which the people in Khar Yalla originate have a historic, unique culture based on fishing, their physical location, family and community structure, solidarity, and other elements. Guet Ndar, Goxu Mbacc, Santhiaba, and Ndar Toute have been inhabited by fisherfolk for hundreds of years.[148] Their communities are tightly knit and feel profound connection to the sea and the peninsula. Residents generally live with or within walking distance of their extended families, in houses passed down through the generations.[149] One older man from Guet Ndar told Human Rights Watch that the neighborhood “is our heritage. Our parents lived facing the sea, and we want the same for our children.”[150] “We don’t just live here,” said a local imam, whose mosque is near the ocean on the Langue de Barbarie, and who explained that the peninsula’s communities have spiritual beliefs and practices tied to living so close to the sea.[151] The communities also have strong governance structures and mutual aid systems that are tied to place and fishing. Neighborhood councils for Goxu Mbacc, Santhiaba, Ndar Toute, and Guet Ndar, and labor associations for different specialties in the artisanal fishing sector liaise between the Senegalese authorities and the communities.[152] Community members rely on each other when they are in need. As Faly Dioup Sarr, a 50-year-old manager of a fleet of fishing boats, describes, “If you don’t have money to buy fish, you can just go and take fish from another fisherman,” with the expectation that he could do the same by you if he needed help.[153]

The protracted displacement of the families in Khar Yalla and the practical difficulties of returning regularly to the sea have dislocated them from their communities and their culture in the Langue de Barbarie. A Red Cross Foundation paper noted that on top of the trauma of losing their homes, the IDPs are suffering from “flight from their … community.”[154] In an interview with Human Rights Watch, Thiare Fall, explained, “We have a very bad feeling [in Khar Yalla], because we don’t have all the members of our family here.”[155] She described that their families were “split up,” first the 2015 and 2016 floods, and then their displacement to Khar Yalla.[156] Many people in Khar Yalla shared with Human Rights Watch that they still feel rooted in the Langue de Barbarie but are struggling to maintain their relationships with loved ones there, given the practical difficulties of visiting regularly.[157] Multiple interviewees also expressed that they intensely miss intangible aspects of living proximate to the sea, such as their connections to spirits associated with the sea.[158] “We are [in Khar Yalla] in our bodies. But our minds, our lives, are still in Guet Ndar,” shared Fatimata D.[159]

Disruption of Livelihoods

Struggle to Maintain Traditional Fishing Livelihoods

For most people from the Langue de Barbarie, fishing is the only profession they know, and it has vital economic and cultural importance for the whole peninsula. Most interviewees in Khar Yalla reported that when they still lived in the Langue de Barbarie, they could make enough money from their jobs in the fishing sector to sustain their families.[160] Moreover, fishing is a way of life for their communities: members “self-identif[y] with their … occupation (‘mol’ or fisherfolk)” above their religion (Islam) or other attributes.[161] In the Langue de Barbarie communities, “Everything is based on fishing—marriages, vacation, family, celebrations,” Aly Tandian, a professor at the University of Gaston-Berger and an expert on migration and local fishing communities, told Human Rights Watch.[162] “[Fishing] is our whole life,” said one older man in Khar Yalla.”[163] “The activity we do as fishermen is our heritage–all of our ancestors and parents did it, and it’s the legacy I leave to my sons,” said Faly Dioup Sarr.[164] Most men and women from the Langue de Barbarie join the fishing sector as teenagers: men work as fishermen; women’s roles in the fishing sector include cleaning, selling, and smoking fish. Older and younger fisherfolk, alike, who are having trouble maintaining their livelihoods after being displaced from the Langue de Barbarie, voiced that they cannot see futures for themselves outside the fishing sector. “The only work we can do is fish work,” said one older fisherman in Khar Yalla.[165] A 22-year-old fisherman told Human Rights Watch, “It’s too late to do anything else.”[166]

Many interviewees in Khar Yalla told Human Rights Watch that the lack of affordable, reliable transportation between Khar Yalla and the Langue de Barbarie has made it much harder, if not impossible, to maintain their fishing livelihoods, for a few reasons. First, people in Khar Yalla are missing out on opportunities to work that are already becoming less lucrative due to the previously described climate and man-made impacts on the fishing sector.[167] Fishing boats tend to depart the Langue de Barbarie in the middle of the night or very early in the morning, when it is hardest to find transportation from Khar Yalla to the sea.[168] Thus, men living in Khar Yalla often literally miss the boat, and women from Khar Yalla may arrive too late to claim fish they can buy or process.[169] Second, those living in Khar Yalla have to spend large proportions of their earnings on transportation. Every day, Inda Diaw, makes at most 10,000 CFA (US$17) as a fish processor, and must spend at least 4,000 CFA ($7) of that on transportation.[170] Mbaye F., who has been sole provider to eight children since her husband migrated to Europe a few years ago and lost contact with her, has the same daily transportation expenses and earns just 5,000-6,000 CFA ($8.50-10.50) per day preparing and selling couscous for fisherfolks’ meals.[171] Third, fisherfolk in Khar Yalla who continue to commute also have to worry about their boats and equipment getting stolen, since they now must leave them near the sea without the ability to stand watch at night.[172]

The community in Khar Yalla has tried to support its members to keep working in the fishing sector, in the absence of government support. Community leaders partnered with a group of foreign university students studying abroad in Senegal to crowd-fund fees for a bus and driver to transport people to the Langue de Barbarie for a year.[173] But this effort has encountered challenges.[174]

The barriers to accessing the fishing sector have forced multiple people in Khar Yalla to abandon their traditional livelihoods. For instance, Fatou Fall Teuw, a 64-year-old woman in Khar Yalla, shared that she had to stop working as a fish processor when they were moved to Khar Yalla.[175] “The way is too far and it’s too expensive,” she explained.[176] Several older men and women also reported that they stopped working as fishermen after being moved to Khar Yalla, because it was too difficult for them to travel to the Langue de Barbarie.[177] “As an older person, I cannot keep up my job of going to the sea to sell fish every day,” said Thiare Fall.[178]

Authorities Thwarted Community’s Attempts to Retrain for New Livelihoods

People in Khar Yalla have also attempted to find alternative employment opportunities to fishing. No such options are available in Khar Yalla itself.[179] A number of young people have taken menial agricultural jobs outside Khar Yalla that pay just $5 per day, because they do not see other opportunities for themselves.[180] The Khar Yalla women’s association, led by Khady Gueye, helps young women who left school to financially support their families train for professions that do not rely on the fishing sector.[181] Two NGOs, the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation and WIN Senegal, donated 12 sewing machines to the association so that women could learn tailoring skills.[182] The foundation also raised funds to construct a concrete center in Khar Yalla to give women a more permanent, sanitary place to learn trades such as processing couscous, tailoring, and hairdressing.[183]

However, authorities have thwarted such initiatives and have made no effort to help people in Khar Yalla retrain for professions outside the fishing sector. Given that the municipality has still not provided electricity in the houses in Khar Yalla, people have been unable to use the sewing machines.[184] Moreover, Khady and staff at the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation report that the mayor’s office refused to meet with them when they tried to secure authorization to build the training center.[185] The community then began construction, until municipal public works officials—including an official who had previously refused to meet with them—arrived and ordered them to stop construction, on the grounds that they did not have authorization.[186] It now stands, partially built, in the center of the site.

Through its inaction and interference, authorities have prevented the people in Khar Yalla from being able to provide for themselves through fishing or by retraining in other livelihoods and have thereby failed to ensure their right to an adequate standard of living. The families in Khar Yalla have seen a reduction in their incomes since they moved to the site.[187] RADDHO found that few households in Khar Yalla make more than approximately $90 per month.[188] This is well below the international poverty line for a lower-middle income country like Senegal.[189] Families cannot afford to rent accommodation closer to the Langue de Barbarie or in other surrounding areas with better living conditions.[190] And multiple interviewees noted that they are experiencing food insecurity in Khar Yalla that they never had in the Langue de Barbarie, not just because of their reduced income, but also because they cannot benefit as much from the mutual aid system in the Langue de Barbarie.[191] For instance, Cheikh Sere, the religious school teacher in Khar Yalla, said, “When we lived in front of the sea and we had trouble affording food, we could get fish or exchange it for rice or other food from our neighbors. We cannot do that here. Sometimes we have trouble eating.”[192] Human Rights Watch is not aware of any efforts taken by the authorities to help the people in Khar Yalla with other access to income or direct provision of essentials such as food to ensure an adequate standard of living.

IV. Khar Yalla Families Are Left Behind

“The local authorities forgot the people who’d been displaced first.”[193]

The Senegalese government failed to include the Khar Yalla families in the permanent, planned relocation for households on the Langue de Barbarie that it is undertaking through SERRP, even though they were displaced by the same type of climate hazard as SERRP’s beneficiaries and have endured many of the same conditions in Khar Yalla that motivated the project. The Senegalese government should urgently remedy its failure to include the IDPs in Khar Yalla in SERRP, make policy reforms to ameliorate the present situation of the people living in Khar Yalla, and develop policies to prevent such oversights from happening again.

2017 and 2018 Flood Victims Temporarily Housed in Khar Yalla

Coastal floods in August 2017 and February 2018 displaced 199 families and 59 families, respectively, who lived in tents in Khar Yalla before being relocated to Djougop as part of SERRP.[194] Their tents were next to the houses inhabited by the displaced families who were moved there in 2016.[195] The Senegalese government provided some emergency relief to the 2017 and 2018 flood victims.[196] The Municipal Development Agency (ADM), which coordinates SERRP’s implementation, managed a census of those who would be moved on from Khar Yalla to Djougop as part of SERRP.[197] The officials carrying out the census spoke to and counted the families in tents, who were displaced by the 2017 and 2018 floods, but not those in houses.[198] By September 2019, authorities had relocated all the families living in tents in Khar Yalla to Djougop, and eventually gave them new houses.[199] Meanwhile, government officials have offered the additional 11,000 people who fall into the scope of SERRP—who have not yet been displaced but live in the 20-meter band on the Langue de Barbarie designated as high-risk of future flood damage—the choice of taking compensation for their house and finding accommodation elsewhere, or being relocated to Djougop.[200] The families in the houses in Khar Yalla reported that authorities have never approached them about being relocated to Djougop or offered them compensation for their destroyed homes or income lost since the floods.[201]

2015 and 2016 IDPs Left Behind Despite Similar Experiences

From SERRP’s inception, one of the project’s primary purposes was to get households displaced by floods out of Khar Yalla, which the project implementors did not consider appropriate for a permanent relocation site. In the World Bank’s 2018 appraisal document for SERRP for the first International Development Assistance (IDA) loan the Senegalese government requested for SERRP (US$30 million), it described the conditions in Khar Yalla as “extremely challenging and precarious,” due to overcrowding in the site and the lack of “sanitation services and inadequate access to water, electricity and transport.”[202] The first component of SERRP— ‘Meeting Immediate Needs of the Disaster Affected Population’—involved relocating the households in tents in Khar Yalla to a site “in an area not prone to flooding” and improving their living conditions in the interim.[203] The appraisal document emphasized, “there is an urgent need to move the displaced population out of the hazard prone area before the 2018 rainy season.”[204] This was not just because those placed in Khar Yalla “face significant health and flood risk,” but because they “may also experience considerable long term negative impacts since livelihood activities have been disrupted and many children have dropped out of school.”[205] As the World Bank explained in a letter to Human Rights Watch, Khar Yalla was rejected as an option for a permanent relocation site for those displaced by floods, because it “was already identified as a flood prone risk area” and failed to meet site selection criteria, such as “feasibility to connect the site to electricity and water network.”[206] The relocation site for SERRP, Djougop, was selected in part because it is not prone to flooding.[207] Echoing this conclusion, an ADM engineer noted that he and his colleagues were “shocked” to find that any houses had ever been built in Khar Yalla: because of the site’s exposure to flooding, he explained, it is “not a place where it is appropriate to build a permanent home.”[208]

The families displaced by the 2015 and 2016 floods were left out of the planned relocation to Djougop despite facing all these conditions in Khar Yalla. Their houses offer more protection than tents but still flood regularly in the rainy season. At SERRP’s inception, all the IDPs living in Khar Yalla had inadequate sanitation services, no water, no electricity, no transportation to schools, and no access to other essential services; all residents lost access to their traditional livelihoods; children living in houses and in tents alike were forced to drop out of school.[209] Since SERRP was launched, the only improvement for the families living in houses is that they finally received pipe-borne water in their houses several years ago.[210]

Moreover, the IDPs from the 2015 and 2016 floods were displaced in the same circumstances and from the same neighborhoods as those displaced in the 2017 and 2018 floods who have benefitted from SERRP. An ADM official coordinating SERRP told Human Rights Watch that one of the project’s purposes is to ensure that those from the Langue de Barbarie “who lost everything could get a new home and restore their living conditions.”[211] Yet even though the families still living in Khar Yalla lost their houses and possessions in coastal floods, they were given permits to temporarily occupy houses in a site where, many report, their living conditions are worse than they were in the Langue de Barbarie.[212]

In some cases, families are now divided between Khar Yalla and Djougop, which has created tensions. For instance, a 22-year-old fisherman living in Djougop shared that his family was moved on from Khar Yalla to Djougop while his aunt’s family, who lost their home first, was left in Khar Yalla.[213] He recounted, “She asked if she could have a room here” in his family’s new house in Djougop, “but my mom had to say that we’re full. We don’t have the space to offer her.”[214]

2015 and 2016 IDPs Receive Less Support for Housing, Essential Services, and Livelihoods than SERRP Beneficiaries

Authorities’ neglect and interference in Khar Yalla contrasts to the efforts authorities have taken for those relocated to Djougop, through SERRP. Djougop is designed to offer residents a new house, access to essential services, and livelihoods training.[215] Each household in Djougop receives a new house with electricity, the size of which is meant to correlate with the size of their house on the Langue de Barbarie.[216] A health clinic and school are under construction at the site; in the meantime, the state is running a makeshift school for children in Djougop.[217] The World Bank donated a vehicle and processing equipment to enable women in Djougop to transport fish from the Langue de Barbarie and keep their livelihoods in the fishing sector.[218] ADM officials told Human Rights Watch that they have tried—albeit unsuccessfully—to convince private transportation operators to better help Djougop, the SERRP relocation site.[219] Additionally, in Djougop, World Bank-funded programs to retrain people in professions such as hairdressing and tailoring have launched.[220] Residents of Djougop told Human Rights Watch that these programs were flawed, and described ongoing issues with some of the infrastructure in Djougop, such as the electricity.[221] Nevertheless, the programs still demonstrate commitment to support those displaced from the Langue de Barbarie not seen in Khar Yalla. Fama Sarr, president of a union of women in the informal fishing sector, expressed outrage at this differential treatment. “Those in Djougop have already benefitted from many more opportunities than those still in Khar Yalla,” she noted.[222] As one focus group participant in Khar Yalla said, “[We] came here first, before the people who moved to Djougop, and yet we don’t have a house [there], even though we lost our houses for the same reasons, because of the floods.”[223]

The families in Khar Yalla are demanding an explanation for this differential treatment, as well as compensation and inclusion in SERRP or an equivalent solution. Community leaders in Khar Yalla, the Langue de Barbarie, and their civil society partners reported multiple, unsuccessful attempts to get an explanation from the mayor’s office and other local authorities about why the government left them out of SERRP.[224] “There are a lot of things that we’ve lost – our rights, our income … and we want compensation,” said Cheikh Sere.[225] The overwhelming majority of Khar Yalla residents want the government to relocate them elsewhere, because they can no longer withstand the terrible living conditions in Khar Yalla. “They’re asking for a second SERRP,” said Mouhamadou Lamine Tall, who directs Forum Civil and Aar Sunu Aalam, which are advocating for improved government transparency and for marginalized residents of Saint-Louis and convene a civil society working group that has lobbied municipal authorities to improve conditions in Khar Yalla.[226] “We just want to have a good space to live with good conditions,” said Khady Gueye, “If there is no space in Djougop, we’ll find somewhere else. We just want to live somewhere in dignity.”[227] “I am ready to go any place better than Khar Yalla,” said Fatou Fall Teuw.[228] “The people of Khar Yalla are so tired. It’s time to support us,” said Mariama D.[229]

Responsibility for Failure to Include 2015 and 2016 IDPs in SERRP

The explanations officials gave Human Rights Watch for why the families still living in Khar Yalla were not included in the planned relocation to Djougop are not justifiable. Even though it was the Saint-Louis municipal government who moved the families living in Khar Yalla today to the site in 2016, multiple local government officials maintained to Human Rights Watch that the families living in the houses in Khar Yalla were not displaced by coastal floods, and thus were not relevant for inclusion in SERRP.[230] This misconception is disproved by the previous sections of this report, and by statements from other community leaders and members from the Langue de Barbarie who insist that the families in Khar Yalla came from G0xu Mbacc and Guet Ndar and lost their homes in floods.[231] Even officials outside the municipality, from ADM and the World Bank, acknowledge that the houses in Khar Yalla were occupied by people displaced by the 2015 and 2016 floods.[232] Meanwhile, in a letter to Human Rights Watch, ADM maintained that the Khar Yalla families were not included in SERRP because they “were considered as having been permanently relocated” and “had already benefited from social housing.”[233] For this reason, ADM explained, the Senegalese government limited the scope of the planned relocation to the 259 families displaced by the 2017 and 2018 coastal floods and the 11,000 people in the 20-meter zone demarcated as high-risk in the Langue de Barbarie.[234] Such reasoning is based on flawed logic. As already described, at the time SERRP was launched, the families living in the houses in Khar Yalla could not live there permanently.[235] They were only given temporary occupation permits, and moreover, the flood-prone site—with no water, electricity, or other essential services—was uninhabitable.

The flawed scoping process of SERRP highlights the need to conduct comprehensive vulnerability and needs assessments before a climate-related planned relocation begins, in order to identify which individuals and communities most need to be relocated. The authorities’ assessments undertaken for SERRP—the census of the 2017 and 2018 flood victims and studies demarcating the 20-meter zone in the Langue de Barbarie—fell short. The authorities failed to consult with the people who had already been displaced by the climate impacts that motivated SERRP, and who needed the kind of protection SERRP offered even more imminently than the approximately 11,000 people living in the 20-meter zone who have not yet been displaced.

It is urgent that the national, regional, and local agencies that implement SERRP promptly include the people displaced by the 2015 and 2016 floods in SERRP or another planned relocation. Action from regional and national actors is particularly urgent, given the municipal government’s inaction for nearly a decade. And as Mouhamadou Lamine Tall emphasized, the process for finding a solution for Khar Yalla should be consultative and involve multiple stakeholders: “We need an inclusive team—of NGOs, municipal authorities, and politicians—to work with the community on a durable solution.”[236]

Learning from Mistakes

Saint Louis is not alone: other communities in Senegal are facing climate displacement and planned relocation, including Pikine and Wakhinane-Nimzatt in Dakar, and Palmarin commune in the Fatick region.[237] The need for last-resort planned relocations is projected to become greater as climate change accelerates.[238] Existing national and regional guidance on climate adaptation and internal displacement, including the Kampala Convention, does not adequately address anticipatory, community-wide planned relocation in the context of coastal floods and sea level rise. It is therefore imperative that the Senegalese government adopt a national policy that explicitly focuses on protecting the rights of people displaced by climate-related hazards and involved in a planned relocation.[239] In particular, the policy should include mechanisms for climate displaced communities to request relocation support, prioritize meaningful consultation, and establish criteria for site selection to ensure beneficiaries’ rights are fulfilled in the relocation site.