Summary

In a February 2019 letter to the United Nations Office in Geneva, the government of Bahrain claimed that its courts “actually hand down very few death sentences.” In fact, since 2011, courts in Bahrain have sentenced 51 people to death, and the state has executed six since the end of a de facto moratorium on executions in 2017. As of June 2022, 26 men were on death row, and all have exhausted their appeals. Under Bahraini law, King Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa has the power to ratify these sentences, commute them, or grant pardons.

While the death penalty is not absolutely prohibited under international human rights law, article 6 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), dealing with the right to life, requires that death sentences “may be imposed only for the most serious crimes.” In the February 2019 letter to the United Nations, the Bahraini government wrote that the death penalty is “applied solely as a penalty for extremely serious offenses, such as premeditated murder as an aggravating circumstance.” The United Nations General Assembly, beginning in 2007 and most recently in 2020, passed resolutions calling on states to impose a moratorium on their use of the death penalty. Presently, some 170 states have abolished the death penalty or introduced a moratorium on its use in law or in practice, reflecting a growing international consensus against its use.

Article 14 of the ICCPR details fundamental fair trial rights, starting with the presumption of innocence. Bahrain acceded to the ICCPR on September 20, 2006. Bahrain’s constitution affirms that “an accused person is innocent until proven guilty.” The UN Human Rights Committee, which monitors state compliance with the ICCPR, has determined that in death penalty cases “scrupulous respect of the guarantees of fair trial is particularly important.”

Article 7 of the ICCPR prohibits torture and ill-treatment, and article 14(3)(g) states that a person is “not to be compelled to testify against himself or to confess guilt.” Bahrain is also a state party to the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. Bahrain’s constitution also prohibits torture and ill-treatment as well as the use of coerced confessions against criminal defendants at trial. Bahrain’s Code of Criminal Procedure includes the same prohibition against the admission of coerced confessions and other basic fair trial requirements such as access to a lawyer and the right to cross-examine witnesses.

In the prosecutions resulting in death sentences examined in this report, Bahraini courts manifestly failed to protect fundamental fair trial rights as provided for in international and Bahraini law. In other cases, the courts meted out death sentences for charges not involving the gravest offenses, namely non-violent drug crimes, violating international and Bahraini law.

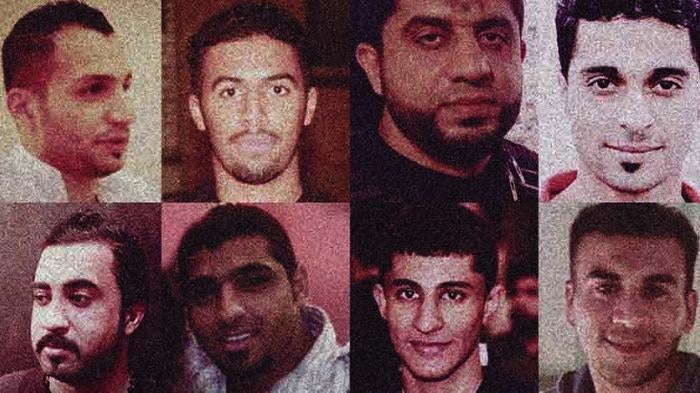

This report documents that, in case after case, courts convicted defendants of the crime of homicide and sentenced them to death based solely or primarily on confessions that the defendants (or co-defendants) alleged were coerced through torture and ill-treatment. In these cases, courts repeatedly failed to observe the requirements of international and Bahraini law that courts ensure any allegations of torture or ill-treatment are impartially investigated and that, only if a genuine investigation deems the torture allegations unfounded, may a confession be received into evidence. These cases were plagued by other violations of key rights as well, including the right to counsel and the right to confront government witnesses. For these reasons, it is clear that the state failed to respect the presumption of innocence in the six homicide cases addressed in detail below, which resulted in eight people being sentenced to death. In the cases this report examines in detail the charged crimes were serious, typically involving the death of a police officer in a violent protest. These eight persons are among 26 currently on death row in Bahrain and they have exhausted all avenues of appeal. They can be executed once the king ratifies their sentences.

The seriousness of the charges in these cases was not matched by the seriousness of the prosecutions and court rulings that resulted in the death sentences. Each case involved credible allegations of confessions extracted through torture and ill-treatment, often supported even by cursory medical examinations that government doctors conducted. In some cases, prosecutors appeared to be complicit in these abuses. In all cases, the prosecution and the courts failed to genuinely investigate, or to credit the results of those investigations that were carried out, into the alleged torture and ill-treatment.

In one prosecution examined below, police arrested Maher Abbas al-Khabbaz in connection with the February 2013 killing of a police officer. Al-Khabbaz alleged that officers suspended him in the air with a metal bar and beat him in an attempt to force him to confess. A forensic doctor with the Public Prosecution Office concluded that al-Khabbaz had injuries consistent with his allegations. Police also arrested al-Khabbaz’s brother, Fadhel, in connection with the same case. Fadhel said that officers kicked him, suspended him in the air, and beat him with a hard object until he signed a “confession” he was not allowed to see. A medical report indicated that Fadhel also had injuries consistent with his allegations of abuse.

The trial court sentenced Maher al-Khabbaz to death in February 2014, based on purported confessions that implicated him by Fadhel and several other defendants, who also alleged coercion. The court took no steps to investigate whether the confessions were voluntary, writing that there was no evidence that any abuse “was [done] with the intention of forcing a confession.” Thus, the court focused on the subjective intent of the officers alleged to have tortured the defendants, rather than on the critical questions of whether the defendants were tortured and the confessions resulted from the torture.

An appellate court summarily affirmed Maher al-Khabbaz’s conviction, but in December 2015, the Court of Cassation reversed the judgment due to concerns about the confessions and directed the appellate court to examine the allegations of mistreatment. The appellate court ignored that directive and concluded a second time that the convictions were proper, on the same grounds it had cited in its first decision. In January 2018, the Court of Cassation inexplicably affirmed the second appellate decision even though it did nothing to address the flaws the Court of Cassation had earlier identified. As a result, al-Khabbaz today is on death row.

In a different case, police arrested Zuhair Ebrahim Jasim Abdullah in November 2017 for his purported involvement in the killing of a police officer. Abdullah alleged that security officers removed his clothing and attempted to rape him, used electric shocks on his chest and genitals, deprived him of sleep for several weeks, and threatened to rape his wife. Prior to his trial, Abdullah filed complaints with the Ministry of Interior’s Office of the Ombudsman and the Special Investigation Unit (SIU), governmental bodies responsible for investigating alleged abuses. According to Abdullah, in his complaint, he claimed that he had confessed falsely to stop the torture the officers were inflicting on him.

During Abdullah’s trial, he argued his confession had been coerced and that the case should be stayed until the SIU-Ombudsman investigations were complete. The court denied this request and dismissed the torture allegations, stating in its verdict that it was “assured of the validity and seriousness of [the] investigations.” The court sentenced Abdullah to death in November 2018, based almost entirely on his confession.

An appellate court rejected Abdullah’s appeal, including arguments about coercion, finding that the “verdict ensured a justified and proper response” to those arguments. The appellate court concluded further it had been proper not to adjourn the case because Abdullah’s complaints were “still under investigation” – the very reason why the case should have been stayed. The Court of Cassation affirmed the verdict in June 2020.

In February 2014, government officers arrested Mohamed Ramadhan and Husain Moosa in connection with the death of a police officer several days earlier. Ramadhan and Moosa claimed that security personnel subjected them to repeated torture and ill-treatment during their detention to force them to confess falsely to orchestrating the officer’s killing. Physicians from the Ministry of Interior and Public Prosecution Office concluded Moosa had various injuries in the days after his arrest – injuries that were consistent with Moosa’s claims of physical abuse.

The only evidence inculpating Ramadhan and Moosa was their confessions and those of four co-defendants who also claimed they had been coerced into confessing. The trial court’s verdict did not respond to Ramadhan’s arguments about coercion or even mention that the four co-defendants had claimed coercion. The court rejected Moosa’s arguments for reasons that were contradicted by medical records, internally inconsistent in describing Moosa’s complaints about torture, and contradicted by later statements from the Bahraini government. The court convicted Ramadhan and Moosa and sentenced them to death.

The appellate court and the Court of Cassation affirmed the sentences. Subsequently, however, the Court of Cassation granted a Public Prosecution Office request to re-open the case, based on a previously undisclosed SIU investigation that raised serious questions as to whether Ramadhan and Moosa had been ill-treated. In a second proceeding, the appellate court again rejected the coercion arguments, relying entirely on the first appellate determination, which had been issued before the SIU investigation results that precipitated the second proceeding were disclosed. In July 2020, the Court of Cassation upheld the death sentences of Ramadhan and Moosa.

In each of these cases and others detailed in the report, courts relied on confessions as the only or primary evidence to sentence people to death, while failing to address meaningfully, if at all, claims that the defendants had been subjected to torture and their confessions coerced. In every case, courts rejected those arguments, summarily concluding that no abuse had occurred or based on analyses that were replete with inconsistencies or contradicted by undisputed evidence.

The Bahraini courts at all levels failed to fulfill their obligations to investigate reports of torture or other abuses and to prohibit the use of coerced confessions as evidence.

It is difficult to avoid concluding that in these cases, all of which have seen defendants placed on death row, Bahraini authorities violated the prohibition against torture and ill-treatment. It also is difficult to avoid concluding that Bahraini courts violated their obligations under international and Bahraini law to investigate such abuses and respect fundamental fair trial rights. As a result, there is no legitimate basis to conclude that the state had respected the presumption of innocence in these cases.

The systematic nature of these serious violations is underscored by other commonalities found among the cases. First, much of the torture and ill-treatment described in this report was alleged to have occurred in two locations – the Criminal Investigation Directorate of the Ministry of Interior, which is housed in a compound in the Adliya district of Manama, and the Royal Academy of Policing, located adjacent to Bahrain’s Jau Prison. There also are substantial similarities in the forms of torture and ill-treatment described by the eight defendants. All claimed that officers beat them using fists. Seven stated that officers specifically targeted their genitals with punches, kicks or electric shocks. Four described sleep deprivation and threats made to harm their family members, including threats of rape. And several said officers had suspended them in the air.

In addition, these cases were rife with violations of the due process and fair trial rights enumerated in article 14 of the ICCPR and Bahraini law. In all six cases, it appears the defendants did not have any access to counsel during interrogations or appropriate access to counsel during trial. In two cases, defendants were not given materials the prosecution used at trial; in one instance, the information consisted of an inculpatory report that relied on secret sources whom the defense could not cross-examine. In another case, the court did not allow for the presentation of defense witnesses.

The individuals whose cases this report discusses are currently imprisoned and awaiting execution at Jau Prison, Building 1, the prison’s isolation ward.

As noted, since 2018, Bahraini courts have also imposed the death sentence on at least five individuals for non-violent drug offenses such as transporting, selling, or possessing hashish. Such offenses, even if involving large quantities of narcotics, in no way qualify as among “the most serious crimes.” Three of the 26 individuals on death row in Jau Prison have been convicted on drug-related charges.

The human rights violations that underlie the death sentences in this report, including the prohibition against torture and denial of fair trial rights, are so serious as to amount to violations of the right to life and reflect not a justice system, but a pattern of injustice.

The government of Bahrain should officially reinstate the de facto moratorium on judicial executions that ended in 2017 and take steps to formally outlaw the death penalty in all circumstances. As a first step, King Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa should commute the death sentences of all persons, starting with those convicted solely or primarily based on confessions that they argued in court had been coerced. The convictions of those persons should be quashed and the persons freed or, if evidence other than confessions exists, retried in judicial proceedings that meet international due process and fair trial standards. The king should also commute the death sentences of persons convicted of offenses such as drug crimes that do not meet the threshold of “most serious crimes” and those persons should be re-sentenced. The government moreover should repeal article 30 of Law No. 15 of 2007, which allows capital punishment for drug-related crimes.

King Hamad should appoint an independent commission to investigate and report publicly on violations of the prohibition of torture by security and judicial officials, including the Public Prosecution Office’s use of evidence obtained through torture or ill-treatment in criminal cases. The Bahraini authorities should prosecute and/or impose disciplinary measures on any security official or prosecutor found responsible for committing or condoning acts of torture and ill-treatment.

The government furthermore should quash all convictions of persons whose trials involved serious violations of due process and fair trial rights protected in international and Bahraini law, such as the right to legal counsel during all phases of the criminal process (including interrogations), the right to access prosecution materials, and the right to cross-examine witnesses. Those persons should be freed or re-tried if the government has evidence of crimes that does not rely on allegedly coerced confessions, and any retrials should be conducted in judicial proceedings that meet all relevant legal standards.

The government should extend a standing invitation to all UN thematic special procedures, including the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, and accept the pending visit request of the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment. In addition, the government should ratify the Optional Protocol to the UN Committee Against Torture, allowing international experts to conduct regular visits to places of detention and providing for the creation of an independent inspectorate.

Recommendations

To King Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa

- Commute the death sentences for all individuals, starting with those convicted on the basis of confessions alleged to have resulted from torture or ill-treatment and those who have been sentenced to death for other than the most serious crimes, such as drug offenses.

- Issue a decree reiterating the prohibition in Bahrain’s constitution and laws of all forms of torture and ill-treatment, and expressing the intent to hold accountable security and other government officials credibly accused of carrying out or condoning such acts.

- Reimpose a moratorium on death sentences and executions, with a view to abolishing the use of the death penalty in Bahrain.

- Establish an independent commission to investigate and report publicly on violations of the prohibition of torture by security and judicial officials, including the Public Prosecution Office’s use of evidence obtained through torture or ill-treatment in the criminal cases examined in this report and otherwise.

To the Bahrain Authorities

- Quash the sentences of all persons whose convictions involved the use of allegedly coerced confessions and/or serious due process and fair trial violations. Free them or re-try them before a court that adheres to international fair trial standards and respects the presumption of innocence.

- Repeal article 30 of Law No. 15 of 2007, which provides that a death sentence may be imposed against individuals convicted of drug offences.

- Ensure independent and impartial investigations into all allegations that government officials or agents committed, ordered, failed to prevent or prosecute, or otherwise abetted acts of torture or ill-treatment.

- Investigate and prosecute officials and agents found responsible for committing, ordering, failing to prevent or prosecute, or otherwise abetting crimes of torture and ill-treatment, regardless of position or rank, including prosecutors and security officials.

- Adopt disciplinary and other measures to deter torture or ill-treatment of suspects in custody by holding accountable officials and agents credibly accused of committing, ordering, failing to prevent or prosecute, or otherwise abetting such acts.

- Amend the Code of Criminal Procedure to require a prompt medical examination by an independent physician (not the Public Prosecution Office’s medical examiner) of any criminal suspect or defendant who claims to have been subjected to torture or ill-treatment by government agents.

- Ratify the Optional Protocol to the UN Committee Against Torture, allowing international experts to conduct regular visits to places of detention and providing for the creation of an independent inspectorate.

- Extend a standing invitation to visit Bahrain to the Special Procedures of the UN Human Rights Council, including the Special Rapporteurs on torture and other cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment, and on the independence of judges and lawyers.

To the Public Prosecution Office

- Terminate ongoing prosecutions and do not undertake future prosecutions based solely or primarily on confessions alleged to have been obtained through torture or ill-treatment unless such allegations have been determined unfounded through independent and impartial investigations.

- Do not seek the death penalty.

- Investigate prosecutors and other law enforcement officials who, in the criminal cases examined in this report and otherwise, colluded in obtaining evidence through torture and ill-treatment or failed to report allegations that evidence had been obtained through torture or ill-treatment, and refer to criminal prosecution those found responsible.

- Conduct an inquiry into torture-tainted confessions used as evidence in court.

To the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights

- Suspend negotiations for any program of technical-capacity building until Bahrain complies with the recommendations in this report, and accepts the pending visit request from the UN special rapporteur on torture.

To the Member and Observer States of the United Nations Human Rights Council

- Support a resolution on the human rights situation in Bahrain that includes a call for the release of individuals sentenced to death based on confessions allegedly obtained through torture or ill-treatment, and the commutation of death sentences imposed in connection with drug offenses.

- Call for Bahrain, during its upcoming Universal Periodic Review in November 2022, to swiftly facilitate access for Special Procedures of the Human Rights Council, including the Special Rapporteurs on torture and other cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment, and on the independence of judges and lawyers.

- Bring attention to the human rights situation in Bahrain and raise concerns during Council meetings and debates, including during Interactive Dialogues with relevant Special Procedures mandate-holders and through individual or joint statements under items 2 and 4.

To the Special Rapporteurs on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment or Punishment, and on the Independence of Judges and Lawyers.

- Issue a reminder of pending visit requests or request an invitation from the government of Bahrain to conduct missions to the country.

To the Government of the United States

- Urge the government of Bahrain through both public and diplomatic channels to implement the recommendations in this report.

- Restrict arms sales and security cooperation until Bahrain enacts and complies with the recommendations in this report, including a standing invitation to, and visit by, the UN special rapporteur on torture.

- Urge the government of Bahrain through both public and diplomatic channels, including during high-level meetings and at the UN Human Rights Council, to halt all executions and seriously investigate torture allegations and violations of the right to a fair trial.

To the European Union and its Member States

- Urge the government of Bahrain through both public and diplomatic channels, including during high-level meetings and at the UN Human Rights Council, to halt all executions and seriously investigate torture allegations and violations of the right to a fair trial.

- Ensure strict implementation of applicable EU human rights guidelines, including those on the death penalty and those on torture and other cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment.

- Suspend the bilateral human rights dialogue until Bahrain takes measurable steps to implement the recommendations in this report.

- Consider targeted measures against Bahraini officials responsible for the abuses documented in this report and as recommended by the European Parliament in its March 2021 resolution.

To the Government of the United Kingdom

- Urge the government of Bahrain through both public and diplomatic channels to implement the recommendations in this report.

- Suspend funding, support, technical assistance and training for security services and the judiciary until Bahrain enacts and complies with the recommendations in this report, including a standing invitation to, and visit by, the UN special rapporteur on torture.

- Urge the government of Bahrain through both public and diplomatic channels, including during high-level meetings and at the UN Human Rights Council, to halt all executions and seriously investigate torture allegations and violations of the right to a fair trial.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch has reported on human rights developments in Bahrain since 1996. The Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy (BIRD), established in 2013, investigates human rights abuses in Bahrain and advocates for the protection of human rights, effective accountability, and democratic reform in Bahrain.

Human Rights Watch and BIRD both have had very limited access to Bahrain. The last time Human Rights Watch was officially able to conduct research in Bahrain was in early 2013. The Bahraini government since then has rejected or ignored requests for visas to visit the country for purposes of monitoring trials, investigating human rights violations, or meeting with government officials.

As such, Human Rights Watch and BIRD have been unable to observe trial proceedings or meet with the defendants, defense lawyers, prosecution officials or witnesses in connection with the cases featured in this report. However, the organizations were able to communicate with some of these individuals remotely, including all but one of the defendants. In addition, the organizations secured court documents from each case, including verdicts, and other materials created by Bahraini government personnel, such as forensic medical reports regarding complaints of torture and ill-treatment by certain defendants, which Human Rights Watch and BIRD translated from the original Arabic. For each case detailed below, the organizations based their analysis primarily on materials generated by the Bahraini government, rather than simply on the advocacy of defense lawyers, defendants, or others.

On February 7, 2022, Human Rights Watch wrote to Bahrain’s Minister of Justice, Minister of Interior, and Attorney General, requesting their responses to the allegations of mistreatment and torture detailed in this report as well as certain court verdicts. As of time of publication there has been no response to these requests.

All documents reviewed in connection with the preparation of this report are on file with Human Rights Watch and BIRD.

Legal Framework

International human rights law, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), to which Bahrain is party, imposes sharp limitations on the use of the death penalty. The United Nations Human Rights Committee, which monitors state compliance with the ICCPR, has noted that “[i]n cases of trials leading to the imposition of the death penalty scrupulous respect of the guarantees of fair trial is particularly important.”[1]

One of the fundamental guarantees of a fair criminal trial, protected under both international and Bahraini law, is the presumption of innocence.[2] This means that a defendant must be treated as innocent unless and until convicted of a recognizable crime in accordance with fair trial standards. And the state must prove a defendant’s guilt of the charges beyond a reasonable doubt to secure a conviction.[3] As one trial court ruled in a case discussed in this report, “[t]he court must find the defendant innocent if there is any doubt in the correctness of the accusations made against him, or in the case of insufficient evidence.”[4]

Another fundamental guarantee protected by both international and Bahraini law is the right to adequate time and facilities to prepare a defense. This includes, but is not limited to, the right to the assistance of legal counsel at all stages of the proceedings, including during interrogations.[5] Bahraini law specifically provides that the accused and the accused’s lawyer shall be entitled to attend all investigative procedures, and that prosecutors “shall give [the accused and counsel] notice of the date” on which any such procedures are to occur.[6] Prosecutors are not permitted to question the accused without inviting counsel to be present, except in instances of “flagrante delicto and urgency because of concern for the loss of evidence.”[7] Bahraini law further provides that, in all cases, the accused “shall not be separated” from his or her lawyer “in the course of questioning.”[8]

The fundamental right to prepare a defense also includes having access to all materials the prosecution plans to present in court against the accused.[9] Bahraini law provides that, in the course of an investigation, the accused shall be entitled to request, at his or her expense, “copies of the documents of whatever kind unless the investigation takes place without [the accused’s] attendance pursuant to a decision issued in this respect.”[10] The accused’s attorney is entitled to examine such materials at least one day prior to a prosecutor’s interrogation of a client.[11]

The right to prepare a defense also includes the right to call and cross-examine witnesses. Under the principle of “equality of arms,” both parties must have a similar opportunity to make their case.[12] This requires allowing the defendant to cross-examine prosecution witnesses, and to call defense witnesses under the same conditions as the state calls witnesses.[13]

International and Bahraini law also protect a defendant’s right not to be compelled to testify against oneself, or to confess guilt.[14] Relatedly, an accused must not be subjected to torture or cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment of any kind.[15] Statements, including confessions, and other evidence obtained through torture or coercion are inadmissible in court.[16] Article 253 of Bahrain’s Code of Criminal Procedure provides that “[e]very statement that has been proved to have been given by an accused or a witness under coercion or a threat thereof shall be ignored and shall not be relied upon.”[17] The Convention Against Torture requires that all credible allegations that a defendant has been tortured or ill-treated should be promptly and impartially investigated.[18] In 2012, the Bahraini government established the Office of the Ombudsman within the Ministry of the Interior (Ombudsman) and the Special Investigation Unit (SIU) within the Public Prosecution Office to investigate allegations of torture.[19]

The cases detailed in this report illustrate how Bahrain has manifestly failed to uphold the fundamental rights of defendants who have been sentenced to death – including the right not to be subjected to torture or ill-treatment as well as numerous due process and fair trial rights.

The Case of Maher Abbas al-Khabbaz

Arrest and Allegations of Ill-Treatment and Torture of Maher Abbas al-Khabbaz

Maher Abbas al-Khabbaz, 27-years old at the time of his arrest, participated in pro-democracy protests beginning in February 2011.[20] On February 19, 2013, al-Khabbaz said, Bahraini security forces dressed in civilian clothes arrested him without a warrant at the Golden Tulip Hotel in Manama, where he worked, at around 11 p.m.[21] “They held me down and took me to a vehicle,” he said.[22] “They asked me for my name and I answered them. They then blindfolded me and took me to the Hamad Town police station.”[23]

Al-Khabbaz said that security forces took him, “not inside the station itself,” but to an annex outside the main Hamad Town police station, where they questioned him about whether he was a member of al-Wefaq or the February 14th organization.[24] Al-Khabbaz said that an officer “accused me of killing a police officer” with a flare gun five days earlier, on February 14, during a protest in the northern Sahla area.[25] Al-Khabbaz said he had “denied this accusation,” after which “the number of people questioning me increased.”[26]

Al-Khabbaz said, “[officers] tied and hanged me using a metal bar between my legs. They then started beating me. They took off my shoes and socks and put them in my mouth. They started hitting with me a plastic club for long hours everywhere on my body. I remained in this state for a few days until blood stopped reaching my legs.”[27]

An officer told al-Khabbaz he “would tell the next shift to continue the hanging” until al-Khabbaz confessed.[28] “After a few days of torture I was tired,” al-Khabbaz said.[29] “They did not allow me food or water. After that I told [officers] I would confess.”[30] Al-Khabbaz said he provided officers with false information “to buy myself some time and take a rest from torture.”[31] “When they found out that I had lied to them they then resumed torturing me for a couple of days. Then my situation worsened,” he said.[32]

Officers subsequently took al-Khabbaz to the Public Prosecution Office, where, he said, “the prosecutor asked me why I was unwell. I told him it was because of the torture to which I was subjected. He told me that if I did not confess, I will go back to being tortured. Then he ordered that I be removed from the room.”[33] According to a letter from the government to the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), this occurred on February 21, 2013, two days after al-Khabbaz’s arrest.[34] Officers then took al-Khabbaz to al-Qalaa hospital for one night and then to the Bahrain Defense Force hospital where he spent four nights and received medical treatment.[35]

Security officers took al-Khabbaz back to the Public Prosecution Office at approximately 1 a.m. on February 25. Al-Khabbaz said he never provided a confession to the Public Prosecution Office.[36]

Later on February 25, 2013, a forensic medical examiner from the Public Prosecution Office examined al-Khabbaz. The medical examiner’s report described “two scratches of ill-defined shape, measuring 1x1 cm each, laterally on [al-Khabbaz’s] lower forearm and the left elbow,” and stated that the scratches were “injuries resulting from friction between the skin and a solid object with a rough surface.”[37] The medical examiner speculated that the friction injuries might have occurred “at the time of the incident,” referring to al-Khabbaz’s arrest.[38] The medical examiner’s forensic report was later reviewed by a member of the Independent Forensic Expert Group (IFEG), who found it was a “brief, superficial assessment” and “very far from an acceptable standard.”[39]

After the medical examination, al-Khabbaz said, officers took him to the Khamis police station, where “a number of officers beat me.”[40] They then took him back to Hamad Town police station. Two days later, he said, officers took him to the Dry Dock Detention Center and placed him in solitary confinement for two days.[41] “They sexually harassed me,” he said.[42] “One of my torturers said ‘I will make you confess’ and ordered another to fetch a stick and soap and tried to take off my trousers.”[43] Al-Khabbaz said he physically resisted and the guards stopped.[44] He said he remained in pre-trial detention in the Dry Dock Detention Center for several months, where he experienced pain from the injuries that resulted from the abuses inflicted on him.[45]

A family member said al-Khabbaz never had a face-to-face meeting with his lawyer or access to a lawyer during interrogations or at any point during his time in custody.[46]

Arrest and Allegations of Ill-Treatment and Torture of Fadhel al-Khabbaz

Maher al-Khabbaz’s brother, Fadhel al-Khabbaz, said that at approximately 2 a.m. on February 20, 2013, security forces arrested him and took him to the Hamad Town police station. “They took my hands and tied them behind my back,” he said.[47] “One officer took off his mask and said, ‘I want you to see my face so you remember me.’ He then started using abusive language.”[48] Fadhel said the officer called him a “son of a bitch” and “son of a whore” and told him, “You will confess whether voluntarily or by force.”[49]

According to Fadhel, officers blindfolded him before placing a metal bar under his knees and binding his hands around his shins. The officers put each end of the bar on a chair or table, suspending him upside down. “[They were touching me] from behind and kicking my testicles from the front with their feet. They were verbally abusing me. They said to me if I don’t confess they will bring my wife and rape her.”[50] Fadhel claims that the officers beat his feet with what seemed to be a plastic hose and hit him with a hard object on the back of his thigh. Fadhel said that he told an officer he had undergone surgery on his left leg – “When they knew this he beat me three times on the back of my thigh.”[51] After this, Fadhel said, he told the officer, “Look, whatever you want me to sign I will say it. Bring me a blank piece of paper, I will sign.”[52] Later, when he was alone in the room, he said, he was able to pull his blindfold down slightly and saw a crowbar, which he believes is what the interrogator used to strike his leg.[53]

Subsequently, Fadhel said, officers suspended him again several times and eventually he had no feeling in his hands or feet. At one point, he said, an officer put what seemed to be a pair of scissors around his fingers and began to apply pressure as another person urged that his fingers be cut. “As a human I couldn’t take this, I had to confess.”[54] Fadhel said an officer claimed Maher had confessed that Fadhel had given him the flare gun. “Maher was in a cabin [sic] next to me. We could hear each other’s screams when [we were] beaten,” Fadhel said.[55] The next day, he said, officers put a piece of paper in front of him to sign.

Fadhel, who was blindfolded and could not read the document, said he signed nonetheless.[56]

On or about February 25, 2013, a medical examiner from the Public Prosecution Office examined Fadhel al-Khabbaz. According to the doctor’s report, “there was a vertical strip abrasion of about 10 cm in length and about two cm in width, covered with a brown crust, many parts of which fell off, located at the back of the left thigh.”[57] This was consistent with Fadhel’s account of being struck there with a hard object, possibly a crowbar. The forensic report noted that Fadhel al-Khabbaz had informed the doctor that he “was tortured on the same day” as his arrest.[58]

Prosecution and Conviction

The government charged Maher al-Khabbaz and seven others with the intentional killing of the police officer, using a nautical flare gun. Fadhel al-Khabbaz was charged with providing the flare gun to Maher al-Khabbaz.[59]

The trial court, consisting of a three-judge panel presided over by Judge Ali Khalifa al-Thahrani, heard the case against Maher al-Khabbaz, Fadhel al-Khabbaz and seven other defendants in connection with the death of Officer Muhammad Asef Khan. The only evidence directly implicating Maher in any aspect of the attack during which the officer was killed came from confessions by Fadhel al-Khabbaz and three other defendants; the court’s description of the confessions leaves it unclear whether any of the defendants had confessed to witnessing Maher kill the officer.[60]

The defense argued that the confessions given by certain defendants were coerced. The trial court ignored these allegations and the Public Prosecution Office’s medical records, which documented physical injuries to Maher al-Khabbaz and Fadhel al-Khabbaz, and took no steps to ensure the confessions were properly obtained. Rather, the court summarily concluded that it did “not see sufficient proof that what [happened] to the second, ninth and first defendants was [done] with the intention of forcing a confession.”[61] Based on this reasoning, which appears to accept that the defendants had or might have been subjected to abuse, the court concluded that the defendants’ “attempt to have the confession[s] declared null and void” was “unfounded.”[62]

On February 19, 2014, the trial court convicted Maher al-Khabbaz and sentenced him to death. The court convicted Fadhel al-Khabbaz and sentenced him to a five-year jail term.[63] Six other defendants were sentenced to life imprisonment and one received a six-year term.[64]

On appeal, the defendants argued that there was insufficient evidence against them, that their confessions were made under duress, that their interrogations took place without an attorney present, and that their complaints of torture had to be examined before the appeal was decided. The appellate court rejected these arguments and upheld the sentences on August 31, 2014, concluding that the verdict was supported by the confessions and other documents (none of which directly implicated Maher al-Khabbaz in the attack on the police officer). “The comments of the defense . . . are merely quibbles taking away from the true picture of the incident ...,” the court wrote, without considering the specific merits of the defense’s arguments.[65]

Despite the absence of any impartial or comprehensive investigation into the coercion allegations of Maher al-Khabbaz, Fadhel al-Khabbaz, or their co-defendants, the court of appeal concluded:

The High Court based its judgment on the confessions made during the investigation of the Public Prosecutor, and on their admissions of guilt in the crime, the basis of the plea, and on the absence of any form of coercion in the making of those confessions. Therefore the plea of the defense in this matter is baseless.[66]

The court of appeal also summarily stated that “[t]he High Court adhered to the law,” “the evidence is reliable,” and the evidence was sufficient to find against the appellants.[67]

Subsequently, on December 7, 2015, the Court of Cassation reversed the trial court judgment.[68] The Court of Cassation credited the defendants’ claims that their confessions were obtained through coercion, noting that such claims were “supported by the evidence that details their multiple injuries.”[69] The Court of Cassation reasoned that the defense’s allegations of coerced confessions “must be discussed and responded to adequately by the Court as they constitute substantial evidence.”[70] More specifically, the Court of Cassation stated:

The Court must ensure thorough investigation into the defense’s allegations, and should investigate the source of the coercion and its direct link to the confessions. If the Court fails to do so, and states there is insufficient evidence of coercion and impact of coercive measures adopted by investigation authorities to obtain confessions, and does not consider the direct link between the injuries . . . and the confessions accepted as evidence, then the Court’s ruling is inadequate and shall be overturned.[71]

The Court of Cassation further found insufficient the trial court’s conclusory finding that the evidence against the defendants was corroborated by their confessions, witness testimonies, and reports of the medical examiner. According to the Court of Cassation, it was “not sufficient to merely refer to [the evidence accepted by the trial court];” rather, the trial court needed to describe the evidence “in sufficient detail to illustrate, according to the understanding of the Court, how it confirms the incident and the extent to which it is in agreement with the rest of the evidence established in the judgment.”[72] Consequently, the Court of Cassation held that “the ruling at the first instance shall be quashed” and “referred to the Court [of Appeal] for reconsideration.”[73]

The court of appeal ignored the directives of the Court of Cassation and summarily credited, again, the trial court’s finding that the defendants’ confessions were valid, thereby affirming the original convictions and sentences. In its judgment, dated May 10, 2017, the appellate court stated:

It is the right of the Court to take into consideration a confession made at any step of the investigation by a defendant against himself or against other defendants, whenever the court has confidence in that confession. The Court of the First Instance was satisfied with the validity of the appellants’ confessions obtained from the Public Prosecution investigations, as it is consistent with the rest of the evidence. Regarding the statement of the invalidity of the confessions of appellants 3, 4, 5 and 6 used in Court as evidence on account of their having been obtained by moral and physical coercion, it is in the Court’s discretion to determine the value of these confessions. It has been proved by the forensic medical report that there were no visible injuries, and therefore, the investigation was conducted without any physical damage to the defendant. Thus, the Court is satisfied that the confessions were obtained under free will without any form of physical or moral coercion.[74]

This reasoning directly contradicted the opinion of the Court of Cassation. It also ignored the medical reports from the Public Prosecution Office which, despite being limited in scope and prepared by a not-impartial office, did disclose injuries and the claims of coercion made by Fadhel al-Khabbaz (appellant number 9), whose purported confession the trial court relied on heavily in finding Maher al-Khabbaz guilty of murder.

On January 29, 2018, the Court of Cassation affirmed this second appellate decision, even though it had previously overturned the convictions based on deficiencies in the first appellate decision that the court of appeal did nothing to address in its second decision.[75]

Violations of International Law

The prosecution of Maher al-Khabbaz involved numerous violations of international law – and analogous provisions of Bahraini law – first in connection with the abuses described by him and his brother, Fadhel al-Khabbaz. As described, there is credible evidence, including reports from the state’s Forensic Medical Examiner, that officers abusively inflicted injuries upon Maher and Fadhel al-Khabbaz to secure their confessions. Despite that, and the fact that Fadhel al-Khabbaz’s confession and the confessions of other defendants who alleged torture were indispensable to the court’s verdict against Maher al-Khabbaz, the court did not conduct any manner of investigation. It did not order independent medical examinations, seek to question those involved in the alleged abuses, or even question Maher or Fadhel al-Khabbaz about the abusive treatment.

To the contrary, the trial court dismissed the allegations and other evidence of torture summarily, saying it did “not see sufficient proof that what [happened] to . . . [Fadhel al-Khabbaz and Maher al-Khabbaz] was [done] with the intention of forcing a confession.”.[76] As such, the court discussed only the putative state of mind of those accused of abuses, rather than the critical questions of whether abuses actually occurred and, if so, whether they resulted in the disputed confessions. In these ways, the trial and appellate courts relied blindly on allegedly coerced confessions, which makes it clear that prosecutors failed to legitimately overcome the presumption of innocence in these cases.[77]

Furthermore, Bahrain violated the due process and fair trial rights of Maher al-Khabbaz, including his right to a lawyer during his interrogations.

Ultimately, the decisions of the Court of Cassation and the court of appeal underscore the fundamental injustice in Maher al-Khabbaz’s conviction and death sentence. The Court of Cassation initially overturned al-Khabbaz’s conviction, finding it was fatally flawed. On remand, the court of appeal effectively ignored the Court of Cassation’s directives as to how to remedy those flaws, stating that al-Khabbaz’s conviction was proper on the very bases that the Court of Cassation had rejected. Inexplicably, the Court of Cassation then found the appellate court’s second judgment proper even though it was plagued by the very failings that had led the Court of Cassation to reverse the first appellate judgment. There is no principled explanation for such a result, which puts in stark relief the fact that Maher al-Khabbaz’s conviction and death sentence were unlawful.

The Case of Sayed Ahmed al-Abar and Husain Ali Mehdi

Both Husain Mehdi and his friend Sayed Ahmed al-Abar, aged 19 and 20 at the time of their respective arrests, were sentenced to death after being convicted of killing a Pakistani police officer on April 16, 2016, during a protest in the village of Karbabad.[78] The deceased officer, Muhammad Nafeed, was one of three officers allegedly in a police car patrolling the Karbabad area during the protest. The Public Prosecution Office alleged that al-Abar threw a bucket of gasoline and Mehdi threw a Molotov cocktail at the police car.[79] According to a forensic report, the fire resulting from the explosion caused the death of Nafeed.[80]

Arrest and Allegations of Ill-Treatment and Torture of Sayed Ahmed al-Abar

On April 24, 2016, according to al-Abar, police officers arrested him and took him to the Royal Academy of Policing,[81] where, he said, “I didn’t sleep for nearly 30 hours…The officers would force me to stand and face the wall. I wasn’t even allowed to lean on it.”[82] For approximately one week, he said, he was “standing for around 18 hours” per day and that interrogations lasted “from 10 in the morning to 2 at night.”[83] Periodically, officers assaulted him, al-Abar said. “They hit me around my genitals and my ears. They hit me around my ears a lot.”[84] During these interrogation sessions, officers ordered him to confess that he had intended to kill a police officer. During this initial period, officers took him to Building 15 of Jau Prison every night.[85]

On April 28, 2016, prosecutors interviewed al-Abar.[86] According to al-Abar, “The officer said that I was being taken to the Public Prosecution and told me what I should say about my ears, that the problem with my ears wasn’t caused by torture, it was an issue from before, and that if I didn’t say this they would hit me some more until I could no longer hear.”[87] Al-Abar told prosecutors he had experienced issues with his ears for a year or two, but that he had not sought treatment due to being “lazy.”[88]

Al-Abar said, “They didn’t provide me with a lawyer, nothing.”[89] According to al-Abar, he never had counsel during his interrogations.

On May 3, 2016, a medical examiner from the Public Prosecution Office examined al-Abar.[90] According to al-Abar, We were left for three or four days so that any marks could disappear. Then we would be taken to a forensic doctor to be examined and to see if we had any marks on us.”[91] Al-Abar claims that, even though most signs of abuse had abated, evidence of injuries was plainly visible at the time of the examination, and there was a “bit of blood on my lips and ears.”[92] The medical report “recommend[ed] that [al-Abar] consult an ear specialist to investigate the reason for his complaint of hearing loss in the left ear.”[93] Additionally, the report noted “[a]brasions marks around the wrists resulting from the handcuffs.”[94]

Arrest and Allegations of Ill-Treatment and Torture of Husain Ali Mehdi

Police arrested Husain Ali Mehdi alongside al-Abar on April 24, 2016 and, Mehdi said, they detained him at the Royal Academy of Policing.[95] Mehdi claims that he was interrogated “I stayed for almost 19 days” from morning until evening; like al-Abar, he said, police took him to Building 15 of Jau Prison on most nights, which is adjacent to the academy.[96] During those interrogations, he said, he was nearly always blindfolded and his hands were cuffed behind his back.[97] Mehdi said that he “was beaten and deprived of sleep all day, especially the first three days, [and that] they were not allowing me to sleep at all.”[98] He was given little food or water, he said. “They were not treating me like a human being.”[99] Mehdi claims police officers took him to al-Qalaa hospital during the first few days, where he was given fluids intravenously, which he claims was “just so you don’t collapse and so you have energy to confess, then they bring you back at dawn for another interrogation until the evening.”[100]

According to Mehdi, officers at the Royal Academy of Policing threatened that they would harm his mother, who, they said, was “alone in [her] house.”[101] Officers took Mehdi to his home and, in his words, “When they got me to the house, they told me to tell my mother that they would kill me if she did not give them [my] phone. My mother tried to rush towards me, they took me away and put me back in the bus. Because of that situation, she surrendered and gave them the phone.”[102]

When Mehdi was taken to the Public Prosecution Office, he said, “All the way we were blindfolded, we were beaten and kicked in the back and head.”[103] Prosecutors interrogated Mehdi and told him to say he had “intended to kill the police officer.”[104] Mehdi said that he

felt “forced to confess” as the police “used every pressure card; torture, beatings, stripping.”[105]

At no time during his questioning did Mehdi have a lawyer present, although Mehdi’s father informed him in a phone call that the family had hired Mariam Ashour as his attorney. According to Mehdi, when the prosecutor asked if he had a lawyer, “he was shocked that I said yes, my lawyer is Mariam Ashour, and he said, ‘We don’t have time for your lawyer.’ I told him I’ll not say anything before my lawyer comes.’ At this point the tone changed and he started saying, ‘It is not up to you, you will talk.’”[106]

Prosecution and Conviction

Mehdi, al-Abar, and 11 other defendants were charged with crimes relating to the death of officer Nafeed.[107] According to Mehdi, the defense was not given access to a cellphone video recording of the April 16, 2016 incident that police had secured, but only to a video recording of a staged reenactment that involved al-Abar and Mehdi. He also said his counsel was prevented generally from accessing relevant documents and that Presiding Judge Ali Khalifa al-Thahrani denied requests by defense counsel to talk with Mehdi outside court, which prevented them from discussing trial strategy.[108]

During the trial, Mehdi and al-Abar argued that their confessions had been coerced through torture and denied that they had intended to kill anyone.[109] Mehdi’s attorney noted that a separate case had been filed to investigate Mehdi’s claims of torture – and according to correspondence from the government of Bahrain, a complaint related to al-Abar was filed as well.[110] In addition, according to defense counsel submissions to the court, other defendants who supposedly identified al-Abar and Mehdi as perpetrators also claimed their statements had been coerced.[111]

The Fourth High Criminal Court substantively ignored these claims, stating simply that:

As the lawsuit documents did not mention the impact of this alleged coercion except for a verbal pronouncement by the defense, the court is assured of the validity of the confession and the detailed acknowledgment made by the aforementioned defendants and considers that it was issued by them voluntarily and out of free will, without coercion or pressure. Hence, the court rejects this argument as being misplaced.[112]

Based on the confessions and no other cited evidence that inculpated Mehdi or al-Abar, the trial court convicted both, sentenced them to death, and revoked their citizenship on June 6, 2017.[113]

On appeal, al-Abar and Mehdi argued again that their confessions were coerced, that their arrests were made without warrants, and that the Public Prosecution Office had failed to prove intent to murder. They further argued that the cause of death of officer Nafeed was not specified in the forensic report and that therefore the autopsy should be repeated.[114]

On February 27, 2018, the court of appeal rejected these arguments, finding the confessions had not been coerced, and upheld the death sentences for both al-Abar and Mehdi.[115]

The Court of Cassation summarily affirmed the lower courts’ rulings that the confessions had not been coerced, while also noting that the confessions were the critical evidence against both al-Abar and Mehdi. The Court of Cassation found that the trial court had “verified that the confessions claimed to be false are right and valid.”[116] The Court of Cassation further found that Mehdi and al-Abar had waived their right to counsel because they did not name a specific attorney, even though, as noted above, Mehdi claims credibly that he requested an attorney by name. On these grounds, the Court of Cassation upheld both death sentences on May 21, 2018.[117]

Violations of International Law

The prosecution of Husain Ali Mehdi and Sayed Ahmed al-Abar involved numerous violations of international law (as also reflected in Bahraini law), first in connection with the abuses they described. With respect to al-Abar, there is evidence that officers inflicted abuses upon him to secure a confession, including a report from the forensic medical examiner that corroborates his allegations of an injury to his ears. Mehdi and the other defendants whose statements allegedly inculpated Mehdi and al-Abar all claimed that their confessions, which were the critical evidence against al-Abar and Mehdi, had been coerced. However, the courts failed to investigate the defendants’ allegations of torture by not ordering independent medical examinations, seeking to question prosecutors and security officers involved in the interrogation process, or questioning Mehdi or Al-Abar regarding the alleged abuse. Rather, the court uncritically relied on allegedly coerced confessions to sentence two men to death.

Beyond the failure to investigate allegations of abuse, the courts’ reliance on the confessions as the evidence establishing al-Abar’s and Mehdi’s guilt indicates a failure by the state to respect the presumption of innocence.

Bahrain also appears to have violated both al-Abar’s and Mehdi’s due process and fair trial rights, including the right to counsel during interrogations, even when Mehdi requested his counsel by name. Additionally, the Public Prosecution Office did not provide to the defense a video of the incident the defense had requested, instead providing only a video of a reenactment.

The Case of Husain Ebrahim Ali Husain Marzooq

Arrest and Allegations of Ill-Treatment and Torture

Husain Ebrahim Ali Husain Marzooq, 25 at the time, was arrested on July 10, 2016, in connection with a highway bombing that had killed a woman on June 30, 2016, near al-Eker village.[118]

During the afternoon of July 10, Marzooq said, he woke up to police officers shouting, “Who are you? Give us your name.”[119] When Marzooq told them his name, he said, “I was in the bathroom, four of them took there, surrounding me and beating me, punching me in the face, abdomen and testicles. All four of them were kicking my head they put my head down on the ground and they blindfolded me and carried me to a car.”[120]

The officers took Marzooq to a medical examination and then to a location where, he says he was photographed. He was then transported to another location “some distance away,” which Marzooq called “the academy,” referring to the Royal Academy of Policing.[121]

When Marzooq arrived at “the academy,” he said, police officers beat him and threatened him.[122] “Now the interrogator will come and you will see what he will do to you,” Marzooq said an officer told him.[123] The interrogator, when he came, cursed him with phrases “too bad to repeat” and threatened to bring his parents for interrogation.[124]

For five or six days, Marzooq said, officers interrogated him. During this time, he did not know “whether it was night or day” because he was blindfolded.[125] Marzooq said officers asked him what he did on the day of the incident and “began to extract confessions by force.”[126] Marzooq said he was “standing throughout this period” and, when he collapsed, “someone will come and kick me, or they would pour water on me to make me stand up again.”[127]

For 11 days, from July 10 to July 21, Marzooq said, he was chained by his ankles and wrists with a heavy-duty chain and a “big padlock used for doors,” so that he could not fully extend his limbs.[128]

Subsequently, Marzooq said, officers brought him to the Public Prosecution Office. There, he said, he confessed after an officer who had beaten him threatened that he would be tortured again if he did not confess. Following the confession, Marzooq was taken to the Dry Dock Detention Centre.[129]

On October 13, 2016, Marzooq, through legal counsel, submitted a complaint to the Special Investigation Unit (SIU) regarding the alleged abuse.[130] According to the Bahraini government, the SIU found the complaint unsubstantiated, saying the officers allegedly involved denied committing abuses and a medical examination did not reveal injuries consistent with the allegations of abuse.[131] The government did not explain why the absence of injuries consistent with abuses alleged to have occurred months before the examination would be dispositive or whether there was evidence of injuries that the SIU believed were not related to the alleged abuses.[132]

Prosecution and Conviction

Marzooq was tried on 11 charges, including “acts of aggression” against Bahrain on behalf of Iran, murder and attempted murder of police officers with an explosive device, and terrorism. At trial, Marzooq argued that his confession was coerced through torture, that the criminal investigation depended on undisclosed secret sources, and that the investigation was not “reliable.” The Fourth High Criminal Court, presided over by Judge Ali Khalifa al-Thahrani, summarily rejected each argument and found that the charges were proven based on the confessions of Marzooq and a co-defendant, Hassan al-Haiki, as well as an investigative report that relied upon undisclosed sources. On June 19, 2017, the trial court convicted Marzooq of all charges, sentencing him to death and rescinding his Bahraini citizenship.[133]

Al-Haiki, Marzooq’s co-defendant, had died within weeks of being taken into custody. According to his attorney and family, his death was due to torture.[134]

In its opinion, the court wrote that Marzooq’s arguments regarding torture were “refutable by the fact that the competent court, if it is reassured about the veracity of the confession, has the right to use the confession of a defendant against himself and others, even if the confession was not supported by other evidence and the defendant recanted.”[135] The court further explained that it was “reassured about the veracity of the confession” because the confession was made in the presence of defense counsel and, at the time of the confession, Marzooq did not claim he was subjected to torture.[136] In addition, the court stated that it was “reassured of the veracity of [Marzooq’s] confession during the prosecution investigations since it was centered on the elements of the charge and events attributed to him.”[137] In sum, the court was “reassured” that Marzooq’s confession was genuine, not because it investigated that issue, but, at least in part, because the confession provided critical inculpatory evidence. The court further rejected an argument the defense made that the trial should be adjourned until there was a ruling on Marzooq’s SIU complaint, noting that the investigation was ongoing.[138]

Finally, the court rejected Marzooq’s arguments regarding the use at trial of the investigative report, which was based on “secret sources” and purported to tie Marzooq to an Iranian terrorist group and implicate him in the bombing. In a circular argument, the court found that “the investigations are reliable, since they contain adequate and specific information that enable identification of the defendants and distinguish them from other people, and showed that they have committed the offense[.]”[139] Because of this ruling, Marzooq and his counsel were never able to confront the “secret sources” to test the veracity of their claims, as is required under international and Bahraini law.[140] In fact, when counsel questioned First Lieutenant Mohamed Khalifa Daaej Salis, the author of this investigative report, regarding its sources, Salis responded that these were “secret sources that I cannot disclose, and they are more than one secret source.”[141] Also, Salis himself could not answer simple questions relating to his report, including in connection with events, places, and timelines regarding Marzooq’s supposed interactions with the Iranian group and involvement in the bombing, underscoring that he had no firsthand knowledge of the information in the report.[142]

On November 22, 2017, the court of appeal upheld Marzooq’s conviction and sentence.[143] The two main issues on appeal were the use of Marzooq’s confession and the reliance by the court on undisclosed sources. In its brief decision, the appellate court summarily stated that “the appellant’s confession is genuine and free of any material or psychological coercion.”[144] The appellate court refused to address “the other objective defense pleas…given they merely constitute an objective debate.”[145]

On February 26, 2018, the Court of Cassation affirmed Marzooq’s conviction.[146]

Violations of International Law

Bahrain’s prosecution of Husain Ebrahim Ali Husain Marzooq raises significant concerns pursuant to international law and comparable provisions of Bahraini law. First, although Marzooq alleged that his confession was the result of torture, the court did not conduct any meaningful review of that complaint or even wait for the results of the SIU investigation. Rather, the court found the confession was not coerced, in part determining that the confession established “the elements of the charge and events attributed to” Marzooq. On that basis, the court determined that it could rely on the confession as critical evidence of Marzooq’s guilt.

The fact that a confession is used as key evidence of an individual’s guilt says nothing about whether the confession was coerced. Absent from the court’s reasoning was any reference to the legal standards relevant to assessing the use of confession alleged to have been coerced. Nor did the court take any required steps to investigate the allegations of torture.

Beyond those failures, the fact that the SIU investigation was pending was precisely the reason that defense counsel requested an adjournment. It also is why, if the court had really wished to determine whether abuse had occurred, it would have adjourned the trial.

Second, the court’s reliance on the investigative report that was derived from secret sources violated Marzooq’s right to have meaningful access to documents upon which the prosecution relies and his right to confront witnesses against him. That report provided the most vital evidence at trial, other than the purported confessions of Marzooq and al-Haiki. Given that the sources were never disclosed, Marzooq was unable to meaningfully investigate or cross-examine the sources, or effectively dispute the information they supposedly provided. This point is underscored by the fact that the author of the report was unable to answer basic questions about it.

Similarly, Marzooq could not confront the deceased al-Haiki whose confession the trial court relied on as strong evidence against Marzooq. Effectively, the government was permitted to use evidence from a powerful corroborating witness without ever having that witness examined, which is difficult to reconcile with fair-trial principles. Given that al-Haiki’s family and lawyer attributed his death in custody to abuse, it seems likely that al-Haiki would have disavowed his confession.

Ultimately, the only evidence establishing key elements of the crimes of which Marzooq was convicted were the confessions and the secretly sourced investigative report. Because the court’s reliance on the confessions and hidden sources violated international and Bahraini law, the state clearly did not overcome the presumption of innocence in Marzooq’s case.

The Case of Salman Isa Ali Salman

Arrest and Allegations of Ill-Treatment and Torture

On December 27, 2014, police officers arrested Salman Isa Ali Salman, 30 at the time, in connection with the death of a police officer the previous July. A member of Salman’s family said the family observed officers beating Salman during the arrest, which occurred in public. After his trial, which ended in April 2015, Salman told his family that this initial beating resulted in a broken nose and injury to his left ear, which he said caused some permanent hearing loss. The family member said that when the family saw police place Salman into a police car, he appeared to have lost consciousness. The police transported Salman to the Criminal Investigation Directorate (CID) in its Adliya headquarters.[147]

According to the family, Salman told them after his trial that officers had beaten him at the CID and applied electric shocks to his genitals. He told them that officers had subjected him to extreme temperatures, placing him in a very cold room for up to several hours at a time and that, for the first two days at the CID, he was not allowed to sleep. Subsequently, officers repeatedly awakened him after only an hour or two of sleep. Salman said that officers had hung him upside down by his legs and demanded that he confess to murder and attempted murder of police officers. At first, Salman said, he refused but ultimately he “confessed” as directed due to the abuse he recounted.[148]

Other than a brief call on the day after his arrest to inform them of his whereabouts, Salman had no contact with his family throughout his pre-trial detention.[149]

Salman’s family said that Salman did not have access to a lawyer during his interrogations. During the trial, Salman was only allowed to see his lawyer during court sessions; he was not allowed to meet with his lawyer outside of court until after his trial, when they met at Jau prison.[150]

Prosecution and Conviction

Along with 11 other defendants, Salman was tried in connection with a police officer’s death that resulted from a bombing in the village of al-Eker on July 4, 2014.[151] At trial, Salman argued that there was no definitive evidence against him except the confessions of two other defendants, which he argued were made under coercion. One of those defendants, Abdul Hadi Ali Hasan Salman Sarhan, similarly argued that his confession was coerced.[152] The court’s verdict against Salman relied heavily on Sarhan’s confession. The court, presided over by Judge Ali Khalifa al-Thahrani, summarily dismissed Sarhan’s allegations of coercion:

The court responds that it is satisfied with the confession of the eighth defendant [Sarhan] in the investigations of the Public Prosecution, as the trial court has complete discretion to assess the validity of the confession and its value in proof against the defendant and against other defendants throughout any phase of the investigations, even if the defendant changed his confessions in later stages. The court has the right to examine the validity of the accused’s claims that his confession was the result of physical and moral coercion. Once the court sees that the confession is valid and was made with free will and [is] reassured [of] its validity and that it is matching with reality and truth, then it has the right to consider this confession with no further review.[153]

The court further stated that because Sarhan “had appeared before a member of the Public Prosecution and made detailed confessions as to his perpetration in cooperation with the rest of the defendants in committing the crime and did not indicate that he was subjected to physical or moral coercion,” and because “his confession conforms with the truth and reality of this case,” the court was “consciously reassured that the confession of the defendant was issued with free will, voluntarily, free from any taint of coercion, and was truthful and consistent with reality.”[154]

The court used Sarhan’s confession – implicating Salman – without ordering an independent medical investigation into Sarhan’s allegations of abuse or any other manner of investigation. Neither did the court investigate Salman’s allegations of abuse. The court did not address Salman’s argument that the confession of the other defendant used against him had been coerced.[155]

Salman’s family said that the court denied Salman the opportunity to present defense witnesses.[156]

On April 29, 2015, the trial court convicted Salman of the murder charges against him and sentenced him to death. The court also revoked the citizenship of Salman and other convicted defendants.[157]

The court of appeal upheld this judgment.[158] On November 7, 2016, the Court of Cassation quashed Salman’s conviction and remanded his case back to the court of appeal, finding that the intent to kill had not been established.[159] On March 7, 2018, the appellate court again upheld the death sentence, concluding that confessions by Salman and his co-defendants established the requisite intent.[160]

On May 7, 2018, for the second time, the Court of Cassation quashed the verdict against Salman, stating that it would review the case on May 21, 2018.[161] Inexplicably, and without any public proceedings, just a week later, on June 4, 2018, the Court of Cassation ordered that Salman’s conviction and death sentence be reinstated.[162]

Violations of International Law

The prosecution of Salman Isa Ali Salman was fundamentally flawed in several respects. First, the authorities appear to have violated Salman’s fundamental right to counsel by conducting the investigation and interrogation process in the absence of his lawyer. During his trial, furthermore, Salman reportedly did not have the opportunity to communicate with his counsel other than in the courtroom. Also during the trial, according to his family, the court denied Salman the opportunity to present defense witnesses.

Second, court records show that the trial court summarily dismissed arguments made by Salman and Sarhan regarding the coercion of confessions. The court made no attempt to conduct an impartial investigation, for example, by ordering a medical investigation or questioning the defendants or government personnel about the allegations.[163] The court simply did not comply with its obligations to examine allegations of torture and to bar evidence resulting from abuse.

Underscoring these failings, the Court of Cassation twice found that intent, a critical element of the crime, had not been established during the trial. After concluding for the second time that Salman’s conviction was unsustainable, the Court of Cassation inexplicably reversed its decision and affirmed the death sentence it had twice rejected.[164]

Given this bizarre procedural history, as well as the reliance of the trial, appeallate, and cassation courts on allegedly coerced confessions that were not investigated, the state clearly failed to respect Salman’s presumption of innocence.

The Case of Zuhair Ebrahim Jasim Abdullah

Arrest and Allegations of Ill-Treatment and Torture

Zuhair Ebrahim Jasim Abdullah, a father of five, was 37 years-old when he was arrested on suspicion of being affiliated with a terrorist group and killing a police officer.[165] According to Abdullah, his arrest took place at his apartment in Sitra during the early morning hours of November 2, 2017.[166] Abdullah told his family that the authorities did not produce an arrest warrant and confiscated some of his personal belongings.[167] Officers took him to the Criminal Investigations Directorate (CID) in Adliya and held him there until about midnight. Abdullah said that they then transferred him to Building 15 of Jau Prison for six days. “Then I was transferred back to CID Adliya, where the serious torture began,” he said.[168]

“They attempted to remove all my clothes,” he said, adding that “the [attempted] rape and the torture started from that day.”[169] “I was prevented from sleeping during ongoing interrogations,” he said.[170] That same day, he said, they subjected him to electric shocks on his chest and genitals. According to Abdullah, on November 9 or 10, 2017, officers transported him from the CID to his home in Sitra, where they kept him in a police car while they entered the house, demanding to find his phone.[171] While Abdullah was still outside, officers gave him a phone to speak with his wife, who was inside. Abdullah said his wife told him that officers had threatened her; he said he could hear how frightened she was. At this point, he said, he mentally collapsed. He said that officers told him, “The police are all here, your wife is alone at home. If you don’t tell us where the phone is, we will rape her.”[172]

Abdullah said “[officers] threatened to kill my children and my family and I still didn’t confess. I told them I can’t confess to something I haven’t done.”[173] Officers then took him to the Royal Academy of Policing, he said, where an officer told him there were “many torturers” in the facility.[174] There, he said, officers interrogated him daily while he was blindfolded and handcuffed.[175] Abdullah said he spent his nights during this period in Building 15 of Jau Prison, where officers did not allow him to sleep more than several hours at a time. At one point, he said, he was taken to the Bahrain Defense Force hospital for treatment for his injuries but not allowed to stay overnight despite a doctor’s recommendation.[176]

According to Abdullah, this abuse left him mentally exhausted and prepared to confess to the charges against him.[177]

Documents generated by the Public Prosecution Office establish that Hamad Shaheen al-Buainain, a supervisor within the anti-terrorism unit, interrogated Abdullah on the evening of November 14, 2017, at the Royal Academy of Policing instead of the Public Prosecution Office, where suspects are usually questioned.[178] Abdullah did not have a lawyer present, according to the Public Prosecution Office records. These records also establish that the prosecutor noted visible injuries on Abdullah, including marks on his wrists. When he asked Abdullah about these injuries, Abdullah claimed it was due to handcuffs. According to the transcript of Abdullah’s interrogation, Abdullah confessed to multiple crimes.[179]

Abdullah said he was taken between Building 15 of Jau Prison and the Academy for several weeks until he was taken to the Dry Dock Detention Centre.[180]

Prosecution and Conviction

Abdullah first was allowed to meet his lawyer in the courtroom when his case was referred to court, four months after he had been detained. According to Abdullah, his lawyer was not allowed to visit him for seven or eight months thereafter.[181]

Abdullah filed a complaint alleging torture with the Office of the Ombudsman and the SIU in April 2018.[182] Abdullah said that Ombudsman and SIU staff interviewed him in connection with the complaint.[183]

In a trial that culminated on November 28, 2018, the government prosecuted Abdullah for affiliation with a terrorist group and the murder of a police officer. During the trial, Abdullah’s lawyer argued, among other things, that Abdullah’s confession was invalid due to physical and psychological coercion and that the case should be suspended pending results of the SIU-Ombudsman investigations.[184] According to the Bahraini government, the SIU concluded that Abdullah’s complaint was unsubstantiated, saying that one officer allegedly involved denied committing abuses and a medical examination did not reveal injuries consistent with the allegations of abuse.[185]