Summary

Many times, I refused to leave the house to try to escape; it was just too difficult for me to run with crutches. It would take several people to help me get into the car, which would make them an easy target for an airstrike. I wanted to avoid exposing other people to that risk.

— Thara J., who lost a leg in an airstrike in 2015 when she was 13

The conflict in Syria has been one of the deadliest in the world, killing at least 350,000 people over the past decade and forcibly displacing over 13 million. Widespread atrocities, extensive violations of international human rights and humanitarian law, and high humanitarian needs have characterized the conflict. Civilian infrastructure has been damaged or destroyed on a massive scale, the health system has been ravaged, and an estimated 12 million—about 54 percent of Syria’s population—are food insecure, with the Covid-19 pandemic further exacerbating humanitarian needs. The United Nations (UN) Human Rights Council has expressed concern that people with disabilities, along with women, children and older persons, are among the most at risk of abuse and violence in Syria.

Based on interviews with 54 people between October 2020 and June 2022, this report examines the specific impact of the conflict on children with disabilities. It examines the risks faced by children with disabilities during attacks, mental health impacts of the conflict, the impact of poverty and a lack of access to humanitarian assistance, health care, assistive devices, and education on children with disabilities’ lives and rights. It also discusses stigma and discrimination and how these impact their human rights.

Interviewees included 6 children between the ages of 12 and 17, 2 young adults with disabilities, and 20 parents and 2 adult relatives of children with disabilities. Human Rights Watch focused on people living in northwest and northeast Syria, because of the particularly high humanitarian needs, lack of infrastructure, and greater accessibility of interviewees compared with other parts of Syria. Human Rights Watch also interviewed 18 representatives of international and local humanitarian organizations and 2 medical professionals working in Syria.

Armed conflicts, including the one in Syria, present specific risks and harms to children with disabilities and their rights. All parties to the Syrian conflict have a responsibility to protect children, including those with disabilities, and ensure humanitarian access.

Children themselves, young people, and their families described how children with physical disabilities faced barriers to fleeing attacks without assistance. A key challenge for escaping hostilities is the absence of assistive devices—such as wheelchairs, prostheses, or hearing aids—that are largely unavailable. Children with a hearing disability or developmental or intellectual disabilities may not hear, know, or understand what is happening during an attack. Children with different types of disabilities are at risk of abandonment if their families feel unable to meet their needs or to bring them to safety.

The situation has worsened as Syria’s 11-year-conflict has increased poverty and structural barriers faced by children with disabilities and degraded the support systems that existed prior to the conflict.

According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), in 2020, households in Syria with more than one member with a disability were nine percent less likely to be able to meet their basic needs than other households. By 2022, all Syrians’ ability to meet their basic needs decreased as compared with 2020. People with disabilities and children were among those disproportionately impacted by worsening poverty.

Families of children with disabilities interviewed for this report were often unable to afford basic necessities, such as food and shelter, let alone the necessities a child with a disability might require, such as therapies and assistive devices. These therapies and assistive devices were largely unavailable where the interviewed families lived.

Parents of children with disabilities in Syria struggled to access health care for their children, information about their children’s disabilities, and early intervention services for children with developmental conditions and disabilities.

Covid-19 has exacerbated these difficulties, particularly when accessing necessary medical care, given Syria’s already over-stretched healthcare system with insufficient functional facilities and low number of qualified personnel per capita.

In addition, mental health and psychosocial support services were either lacking, generally not inclusive of, or inaccessible to, children with disabilities. This has compounded the Syrian conflict’s devastating impact on the mental health of children with disabilities who, unlike other children, worry that their situation may put family members at risk or that they will be abandoned during attacks and have a chronic lack of access to inclusive education and support services, including mental health services.

Children with disabilities in Syria also face increased barriers to accessing public schools and educational services provided by humanitarian organizations. Inaccessible roads, inaccessible school facilities, and a lack of assistive devices pose challenges for children with physical disabilities. A lack of trained teachers, inclusive curricula, and stigma impede the right to education of children with sensory, intellectual, and psychosocial disabilities.

This report documents discrimination, exclusion, verbal abuse, and threats against children with disabilities. It also includes one case of a young girl who was allegedly chained by a relative.

Approximately 28 percent of Syria’s current population has a disability, according to a UN survey, nearly double the global average. A 2021 countrywide UN Humanitarian Needs Assessment in Syria found 19 percent of children between the ages of 2 and 17 have a disability, and another assessment published in March 2022 found 21 percent of children between ages of 2 and 4 in northeast Syria have a disability. Another needs assessment published in 2022 notes a “chronic lack of data on persons with disabilities at the internally displaced persons (IDP) site level,” suggesting the actual numbers and percentages of children with disabilities may be higher than reported.

Conflicts generally increase the prevalence of disability as a result of injury, mental health trauma, and a lack of access to basic needs and essential services. In 2022, OCHA reported that one in four children under five in some parts of Syria are chronically malnourished and at risk of experiencing physical and cognitive impairments, repeated infection, developmental delays, disabilities, and even death. While there is no recent data on how many people have acquired a disability as result of the war, in 2015, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) reported more than 1.5 million adults and children in Syria have acquired a disability due to the war.

The humanitarian response in Syria has been one of the largest in recent history with billions of US dollars contributed: $6.7 billion was pledged in 2022, including by the United States, European Union (EU), and EU member states. However, according to the UN, this is not enough to meet rising humanitarian needs. The response has also been complicated by the Syrian government’s actions—namely, the co-optation of humanitarian assistance to fund atrocities, advance its own interests, punish those perceived as opponents, and benefit those loyal to it—as well as the closure of the border crossings with Turkey used to bring humanitarian assistance into Syria. As of 2022, 14.6 million people, including 3.3 million people with disabilities over 12, in Syria required humanitarian assistance: an increase of 1.2 million from 2021.

Despite being one of the largest in recent history, humanitarian operations in Syria have not sufficiently captured the rights and needs of children with different types of disabilities. According to the UN Humanitarian Needs Overview 2021 report, people with disabilities in Syria “face systematic challenges in accessing humanitarian services on an equal basis with others.” However, that report makes very limited reference to the situation of children with disabilities.

Human Rights Watch research found that international and local humanitarian organizations operating in Syria that provide services to children with disabilities either do so in so-called special settings or separated from other children; sometimes, only disability-focused organizations provide such services. While targeted services are important, they should be provided alongside inclusive and universal programs, especially in educational settings.

The massive impact of the war on children with disabilities in Syria has highlighted the need for the UN and governments to commit serious attention and resources to mitigate the impact of the conflict on children with disabilities. However, UN monitoring and reporting continues to pay less attention to children with disabilities, compared with other children. For example, the UN secretary-general’s 2021 report on children and the Syrian armed conflict includes data on children who have been injured or “maimed,” which can cause long-term disability, but does not frame concerns or responses in the context of the rights of children with disabilities. General protections, while applicable to children with disabilities, are not adequate responses to the specific barriers, risks, and harms faced by children with disabilities.

Without detailed and careful UN monitoring and reporting on the experiences of children with disabilities, the full impact of the conflict on them and their rights will remain unclear. Consequently, the protection response, including the humanitarian response, may miss or underserve a substantial group of children.

The rights of children and adults with disabilities in Syria’s conflict are protected by international humanitarian law and international human rights law. Customary international humanitarian law applies to all parties to a conflict, both state and non-state actors and protects civilians in times of wars, like Syria’s internal armed conflict. International human rights law applies at all times. The Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) explicitly remind states of their obligations to ensure the safety and protection of children, including those with disabilities, during armed conflicts.

The CRPD requires the UN and governments to move beyond simply identifying people with disabilities, including children, in a list of “vulnerable” groups and instead to apply a disability rights approach to the norms of civilian protection. This includes being cognizant of the experiences and rights of children with disabilities during attacks and evacuations; in accessing basic necessities, education, and humanitarian services; and during peace processes factor these experiences into targeted protocols, rules, and approaches to civilian protection.

The UN Security Council should request that humanitarian assessment reports and plans and reports by the secretary-general and other UN agencies on Syria specifically cover the situation of children with disabilities. The secretary-general should systematically address the impact of the armed conflict in Syria on children with disabilities in his reports and briefings.

UN country teams in Syria should do more to document the conflict’s impact on children with disabilities. The UN special representative on children and armed conflict should work with country teams to ensure information about the disproportionate impact of the conflict on children with disabilities is collected, analyzed, and reflected in relevant reports.

Donors and humanitarian organizations operating in Syria should provide targeted, rights-respecting, tailored, and disability-led responses to the rights and needs of children with disabilities, including their rights to food, adequate housing, rehabilitation services, health care, mental health and psychosocial support services, and education.

All parties to the conflict in Syria should immediately end all direct, indiscriminate, and disproportionate attacks on civilians and civilian objects and ensure respect for international humanitarian law and international human rights law. They should also allow prompt and unhindered humanitarian access to UN agencies and humanitarian organizations to deliver impartial assistance to civilians in need across Syria. Finally, they should ensure children with disabilities have access to education, health care, assistive devices, and other services, and are protected from discrimination and abuse.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch interviewed 6 children between the ages of 12 and 17 (2 girls and 4 boys), 2 18-year-olds with a disability (1 woman and 1 man), 20 parents (12 fathers and 8 mothers), and 2 adult relatives (1 man and 1 woman). The listed age is their age at the time of the interview. The majority of children described in this report were born shortly before the conflict began in 2011 or during the war. As such, their lives have been overwhelmingly shaped by the armed conflict and the violent attacks, displacement, and degradation of essential and other services that have characterized it.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed 18 representatives of UN agencies, international humanitarian organizations, and local humanitarian organizations and 2 medical professionals working in Syria.

All interviews occurred between October 2020 and June 2022. The researcher conducted interviews remotely by telephone or, for a small number, by video call. This approach created numerous challenges as it restricted Human Rights Watch’s ability to contact children with disabilities and their families, especially those without electricity or internet access. Due to the inherent limitations of using a telephone, it was particularly difficult to directly reach and communicate with children with certain types of disabilities, such as hearing and intellectual disabilities.

Interviewees included children or relatives of children who have various learning, physical, developmental, intellectual, sensory, expressive, or receptive language disabilities or autism.

All interviews with relatives and children were conducted in English with Arabic interpretation. Most of the interviews with humanitarian workers were in English; some used Arabic interpretation. The researcher informed all interviewees about the purpose and voluntary nature of the interviews, the ways in which Human Rights Watch would use the information, and that they would not receive any compensation for their participation. The researcher obtained consent from all interviewees and gave the children and their families the opportunity to decline to answer specific questions or end the interview at any time.

Human Rights Watch took precautions to avoid re-traumatizing the children and adult relatives interviewed for this report. This was especially important in light of the trauma experienced by many Syrians and the lack of accessible psychosocial support services across Syria. All interviews with children occurred in the presence of a parent.

To protect the privacy of the children and their families, Human Rights Watch has withheld some names. Parents and adult caregivers’ names are used only if the interviewee specifically requested that their name be included and Human Rights Watch deemed no risk would follow the publication of their name. Real names of adults are written as a first name and an initial. Pseudonyms are indicated by a first name and are noted in the footnotes. All children’s names are pseudonyms, except in a few cases where their adult relatives gave consent, they had been identified in previous Human Rights Watch reporting, or they appear in multimedia materials connected to this report.

Human Rights Watch has also omitted the names of several staff members of international and Syrian NGOs at their request to preserve their anonymity and ability to work without constraints in Syria.

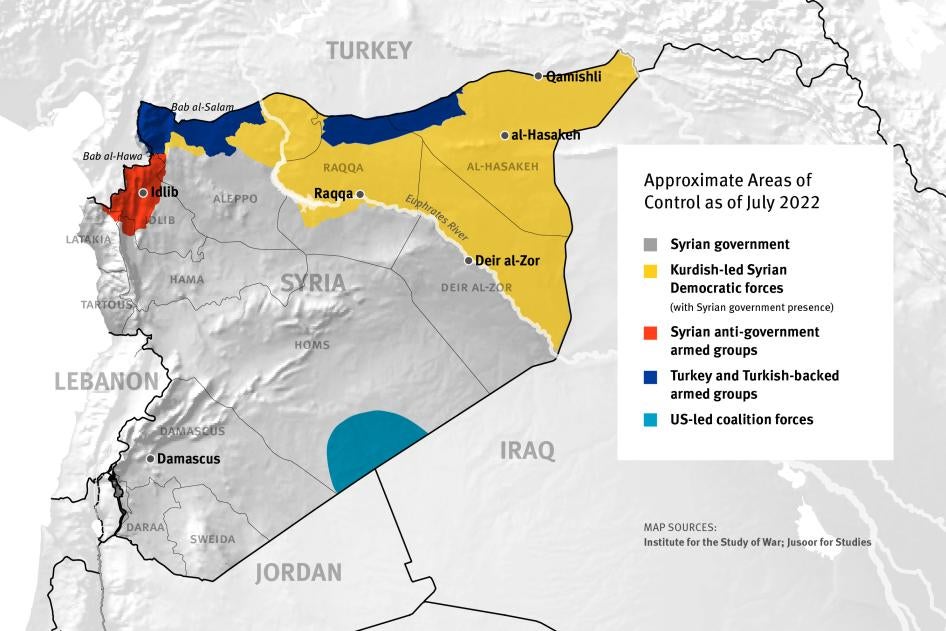

Nearly all interviewees lived in northwest and northeast Syria, which are, respectively, under the control of anti-government groups and the Kurdish-led Autonomous Administration. Some families lived in areas in the northeast under the control of Turkey and affiliated armed groups, and two families lived in areas in the northeast under the control of the Syrian government. Human Rights Watch selected these areas because of their particularly high humanitarian needs, lack of infrastructure, and greater accessibility of interviewees compared with other parts of Syria. Human Rights Watch also interviewed one parent in Damascus. Four of the humanitarian workers were based inside Syria; the others were based in neighboring countries.

This report aims to publish information on human rights concerns affecting children with disabilities and their families in Syria. It does not seek to identify the parties to the conflict responsible for the attacks mentioned in it, but instead seeks to stress their responsibility to protect children with disabilities and their rights and to ensure humanitarian access.

Background

Most of the territory in Syria is under the control of the government.[1] Under international human rights law, Syrian authorities bear the primary responsibility of respecting, protecting, and fulfilling the rights of children with disabilities in Syrian territory. This includes ensuring the protection of children with disabilities caught up in the conflict and providing them with access to services to address their basic rights and needs, such as health care, assistive devices, education, and other necessary services and support.[2]

However, the Syrian government has obstructed the work of humanitarian agencies and organizations providing impartial assistance. Instead, it should facilitate their efforts, which should be inclusive of and able to reach people with disabilities in need.

Northern Syria is under the control of anti-government groups, the Kurdish-led Autonomous Administration, or Turkey and Turkish-backed armed groups. Those who exercise effective control in Syria’s northwest and northeast have obligations to respect and protect rights, including of children with disabilities, by providing services or facilitating the work of humanitarian agencies.

Under international humanitarian law, the Syrian government and all other parties to the conflict should take all feasible precautions to minimize harm to civilians and civilian objects and should not carry out attacks that would fail to discriminate between combatants and civilians or cause disproportionate civilian harm.

Since the start of the armed conflict, Human Rights Watch has documented human rights violations and abuses, war crimes, and crimes against humanity, ranging from torture and mistreatment to indiscriminate attacks and the use of chemical weapons. These violations of international humanitarian law and human rights law have significantly affected all Syrians, including children with disabilities.

This report aims to publish information on human rights concerns affecting children with disabilities and their families in Syria. It does not seek to identify the parties to the conflict responsible for the attacks mentioned in it; instead, it seeks to stress their responsibility to protect children with disabilities and their rights and to ensure humanitarian access.

Children with Disabilities at Greater Risk During Attack

Situations of armed conflict and crises often force people to flee when violence erupts.[3] People with disabilities are at high risk when their communities are attacked. In March 2021, the Secretariat of the Conference of States Parties to the CRPD highlighted the disproportionate risks faced by people with disabilities during all armed conflicts, including their ability to flee attacks.[4] They may be less able to flee, especially in the absence of advance warning or access to assistive devices. They may be left behind: their families sometimes face a split-second decision, either to flee with those who can escape easily or to remain behind to provide support.

These global findings are extremely applicable to Syria, given its population of people with disabilities. Approximately 28 percent of Syria’s current population are estimated to have a disability, a figure that is nearly double the global average.[5] Children have disabilities at similar levels as well. A 2021 nationwide needs assessment found 19 percent of Syrian children aged 2 to 17 have a disability, and another assessment published in March 2022 found that 21 percent of children aged 2 to 4 in Northeast Syria have a disability.[6] The latter report cites a “chronic lack of data on persons with disabilities at the IDP site level,” which, since more than six million Syrians are internally displaced, suggests that the actual number of children with disabilities may be higher than reported.[7]

While there is no recent data on how many people have acquired a disability as result of the war, in 2015, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) reported more than 1.5 million people in Syria have acquired a disability due to the war.[8]

The 2021 Syria UN Humanitarian Needs Overview found people with disabilities, as well as older people, are at increased risk of being separated from their families and caregivers, and they are also in need of assistive devices to support their independence.[9] Human Rights Watch’s findings further confirm these risks and needs.

Eighteen parents of children with disabilities, two children, and two 18-year-olds in Syria told Human Rights Watch about the serious barriers to safely flee attacks experienced by children and adults with disabilities. Children with physical disabilities struggled to flee and seek shelter, often needing to rely on family members or others to carry or support them during their escape. In three cases, parents and relatives described being forced to leave their children with disabilities in order to flee safely with other family members.

Thara J., 18, was originally from a town in Idlib governorate in the northeast. She lost her left leg in a January 2015 barrel bomb attack when she was 13.[10] (Barrel bombs, used primarily by the Syrian government, are improvised, unguided bombs launched from a helicopter or aircraft.) Since 2016, Thara J., who still lives in Idlib governorate, has experienced dozens of airstrikes and shelling attacks, adding that there was never an advance warning, which would have allowed her more time to flee. She has difficulty running with crutches and worries about exposing her family to risks when they stay behind to assist her during an attack:

I feel that I am a heavy burden on my family; they have to help me escape, which puts them at risk. But when I decide to stay at home, my family will stay home with me. The scariest thing when I hear an airstrike is knowing that I might lose someone I love.[11]

Musa is a 13-year-old with a physical disability who uses a manual wheelchair. Musa, his mother, and three of his siblings fled Murat al-Numan and are internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Afrin region, Aleppo governorate, in northern Syria. His father died at the beginning of the war. “We never thought of leaving our area until we got directly hit by the airstrikes,” his mother said. “One time I had to flee with my other children, leaving [Musa] behind with his grandfather and his uncle who helped him flee.”[12] According to Musa himself, “We had to flee many times, and I had to crawl from one room to another to flee.”[13]

Children with a hearing, developmental, or intellectual disability may not hear, know about, or understand what is happening during an attack. Ahmed, a father of six children, including an 11-year-old girl who is deaf, and his wife fear for their daughter’s safety because she cannot hear airstrikes or shelling where they live in Harem district, Idlib governorate. “My wife and I keep our eye on her all the time, and if we hear an attack, we have to physically go and grab her to bring her with us to the shelter,” he said.[14]

Fatima J., the mother of an 11-year-old boy with an intellectual disability, recounted a nighttime attack in Afrin:

The balcony on our house was hit, and he didn’t understand what was happening. We had to take him by the hand and get him out to secure his safety. He didn’t know what was happening.[15]

Several other parents and family members of children with disabilities in Syria shared similar experiences.[16]

Interviews specifically revealed how the absence of assistive devices—such as wheelchairs, prostheses, or hearing aids—made it challenging for children with disabilities to escape hostilities. This has also broadly affected their lives and enjoyment of their rights, discussed in more detail in Section V.

Osman is a father of five children, including Reem, 13, who has cerebral palsy. The family is currently internally displaced in al-Shaddadi town in northeast Syria. Osman recounted several incidents of fleeing attacks, including airstrikes and missile strikes, and the struggles he encountered because Reem does not have a functioning wheelchair.[17]

Osman recalled one instance:

A house next to us was hit. Everyone started running away, and I didn’t know what to do.… I was thinking of my child Reem and my other children. How will I be able to flee having to carry Reem? She was about 11 at that time, and she is a tall and well-fed child. And I have four more children. I went outside the house. I was in shock, not knowing what to do and seeing everyone else running away.

At first, I started carrying both Reem and her 2-year-old brother while my wife took care of our other children. But I couldn’t continue like that. I asked my brother for help, he found a wheelbarrow, and we put her and her brother in it. That’s how we were able to flee. I pushed the wheelbarrow for 9 kilometers. It was very difficult.[18]

Merwa, the mother of two girls, 7 and 9, with hearing disabilities, in Afrin, has been unable to repair one of her daughter’s hearing aids, which broke after she fell off a bicycle. She fears they will not be aware of attacks without functioning hearing aid:

This is why I am looking for support. Even if I am screaming, and they are not close enough for me to just grab them [during an attack], they won’t be able to hear me. I am scared for them.[19]

In the panic of an attack, some families leave children with disabilities behind. Eighteen parents told Human Rights Watch they encountered difficulties escaping an attack while supporting their children with disabilities. Two single parents of children with developmental and physical disabilities described fleeing without being able to assist those children, forcing them to leave those children behind. Both parents were reunited with their respective child during the attack or at a later time.

The uncle of Omar, a 10-year-old with intellectual disabilities, who lived next door to Omar, described an instance when his parents mistakenly left the boy behind while fleeing an attack:

He has no fear, and he doesn’t understand [the danger]. He doesn’t react like other children. Once, early in the morning, at about 8 a.m., we had just had breakfast when a jet flew over our houses. When this happens, we usually run to a small cave, about 10 meters from the house. We all ran to the cave, and then we realized Omar was not with us. His parents ran back to the house to fetch him, and just a few seconds later, their house was struck by a missile, completely destroying it. They had saved him at the very last minute.[20]

Similarly, Ahmed A., an 18-year-old with a physical disability from Deir al-Zor governorate in southeast Syria, recounted a time he was abandoned during an airstrike:

It was really hard for me to protect myself like everyone else was. One time, I was out with my friends when airstrikes started. Everyone was just thinking of themselves and started running, and I was left alone. I could only walk very slowly to find a place to hide.[21]

One parent of three, including an 11-year-old boy with speaking and intellectual disabilities, has himself had a physical disability since his leg was amputated in 2006.[22] Together with his wife and children, he fled west Aleppo and was living in a tent in a camp site in northern Aleppo for nine months at the time of the interview. He expressed his challenges in getting to safety:

It’s really hard for people like me who have disabilities to flee any airstrikes or explosions. When I had to leave my town and flee to safety, I depended on other people to hold me and run with me, because I couldn’t flee alone.[23]

In April 2019, Nujeen Mustafa, a disability rights activist from Syria, shared the difficulties she faced as a child with a disability fleeing attacks in Aleppo city to the UN Security Council.[24] Nujeen described living in Aleppo during attacks and how often her mother would carry her to the bathroom to hide since it would have been hard to carry Nujeen down five flights of stairs to get to shelter. “Every day, I feared that I could be the reason that my family was one or two seconds too late,” Nujeen said.[25] Similar to the children included in this report, Nujeen did not have a wheelchair. She said, “many people with disabilities cannot depend on their families to help them reach safety. Often, because their family members have been killed or have already left.”[26]

International Legal Obligations in Armed Conflict

The CRPD obliges states parties to take “all necessary measures to ensure the protection and safety of persons with disabilities in situations of risk,” including armed conflict, in accordance with their obligations under international humanitarian law and international human rights law.[27] The CRC has similar provisions for children in armed conflicts, calling on states parties to “undertake to respect and ensure respect for rules of international humanitarian law applicable to them in armed conflict relevant to the child.”[28]

International humanitarian law, which applies to all parties to the conflict, includes a fundamental obligation to distinguish between civilians and combatants at all times.[29] In order to protect civilians, international humanitarian law also requires parties to the conflict to give effective advance warning prior to an attack that may affect the civilian population.[30] Advance warnings should be accessible to and inclusive of people with disabilities, such as by making them accessible using different forms of communication.[31] The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights said: “the failure to comply with this obligation [to provide an advance warning] in an accessible and inclusive manner amounts to discrimination on the basis of disability.”[32] To be effective, a warning should, where possible, allow sufficient time to maximize the opportunity for civilians with disabilities to act on the warning.[33]

Poverty and Lack of Access to Services

Poverty and its detrimental impact on rights, affects many families in Syria, but those with disabilities are particularly affected. On average, children with disabilities and their families are more likely than others to experience poverty and social exclusion.[34]

Armed conflict and forced displacement further exacerbate this.[35]

Poverty has impacted the lives and human rights of all children with disabilities included in this report. Due to the conflict, children with disabilities and their families lost homes, assets, income, livelihoods, and assistive devices, and lived in at-risk areas and inadequate conditions, including tents. Families interviewed struggled to provide necessities for their children, including food, health care, adequate housing, assistive devices, medication, therapies, diapers, and transportation fees to access schooling and some service centers.

Households in Syria with more than one member with a disability are nine percent less likely than other households to be able to meet their basic needs.[36] 60 percent of households with a person with a disability are food insecure compared with 51 percent of households not reporting members with a disability.[37] The UN defines food insecurity as lacking regular access to enough safe and nutritious food for normal growth and development and an active and healthy life.[38]

Linked to the above, adults with disabilities in Syria, particularly those who are internally displaced, are nearly 20 percent less likely than those without disabilities to be involved in income-generating activities that could help alleviate poverty.[39] However, physical barriers to infrastructure and services have impacted the ability of people with disabilities to engage in community activities and to have opportunities to generate income.[40]

According to one parent with a physical disability, “There are no opportunities to provide food for the table. It’s really difficult for everyone, but especially for people with disabilities.”[41]

Food insecurity is rampant in Syria. It is estimated that a lack of access to proper nutrition has meant that millions of children are experiencing insufficient growth and are at risk of “impaired” physical and cognitive development.[42]

More than 550,000 Syrians under the age of 5 were chronically malnourished in 2021.[43] In 2022, Syrians were forced to reduce their food intake, and one in four Syrian children were “stunted” and may experience complications regarding their “physical and cognitive development, repeated infections, development delays, disabilities and death.”[44] The lack of proper nutrition, coupled with the lack of medical care and rehabilitation, may lead to a disability.[45] Existing research shows that children with disabilities are, in general, at high risk of malnutrition.[46]

Unfortunately, there is a gap in research on how lack of access to nutrition has impacted children with disabilities in armed conflicts. Regarding the Syrian context, OCHA committed to “develop an indicator for inclusion of children with disability and plans to improve data collection specifically strengthening the nutrition-disability link,” to better understand the specifics of this particular situation.[47]

Only two of the parents interviewed by Human Rights Watch had a secure source of income. Adults with disabilities interviewed for this report and parents and caregivers of children with disabilities reported difficulties in finding employment opportunities. Six of the mothers interviewed were single parents, including some who could not work because they needed to provide nearly constant care to their children with disabilities. This reflects findings that female-headed households in Syria are less likely than households overall to be able to meet basic needs, and their ability to do so steeply deteriorated in 2020.[48]

All but three families interviewed for this report were internally displaced at the time of the interview, including seven families who lived in tents in makeshift camps with no camp management. Three families who were displaced at the time of interview returned to their homes in 2020 and 2021, and two other families moved from makeshift camps to rented housing by June 2022.

Humanitarian actors in northwest and northeast Syria cannot guarantee the delivery of humanitarian protection and assistance in “self-settled, informal sites that lack camp management.”[49] This is particularly concerning as continued hostilities and repeated displacement have led to “approximately 6.6 million internally displaced persons and approximately 106,000 returnees currently living in economic hardship with widespread humanitarian needs.”[50]

This context negatively affects children with disabilities and their families, who may require additional resources to meet their children’s needs.

The financial situation of Dib H., a father of seven children, including a 13-year-old boy with developmental disabilities, has been dire since they fled their hometown of Maaret al-Nu’man, Idlib governorate. At the time of the interview, they were living in a tent in a makeshift camp near the border with Turkey. He said:

Even before coming to this area, there was no help or support, but I was able to work and provide for my family. We didn’t look for anyone else to help. Now it’s been a year since we’ve been in this area, all the money we had saved is gone, and I cannot provide for my family.[51]

Dib H. explained that he cannot afford the medication prescribed for his son with a disability. “There are days when I cannot even afford bread or water, let alone medication,” he said.[52]

Ahmed, a father of 6 children and whose 11-year-old daughter has a hearing disability, was living in a tent in an IDP camp in Harem district, Idlib governorate, when Human Rights Watch interviewed him in early 2021. He described his pre-war economic situation:

Before 2011, I had a secure job with the government and, in addition, had my own agriculture supply shop because I have a bachelor’s degree in agriculture engineering. I had enough income for my family, and we were living in peace with no fear. When the war started, everything changed, and I lost my job and my house. My daughter has a disability, and I cannot even afford to buy her hearing aids.[53]

In June 2022, when Human Rights Watch interviewed Ahmed again, his family had moved to Azaz town, Aleppo, where Ahmed had secured a job and rented a house. His monthly salary is USD $250 and their rent is USD $100 per month.[54]

Ahmed A., the 18-year-old with a physical disability living in Deir al-Zor, explained that he and his family were unable to purchase the adult diapers he requires because of his disability, which affects his bladder and bowel control. Instead, he has had to use children’s diapers, which do not meet his needs, because they were cheaper. “It’s emotionally hard to be in this situation because we cannot afford the right diapers,” Ahmed A. said. “I cannot go out with my friends; I just sit at home.”[55]

Ahmed A.’s mother, Hana I., added, “It’s very expensive and very difficult to afford diapers, sometimes we even have to stop buying food so we can buy them.”[56]

Yezda lives in Kobani and has three sons, two of whom have disabilities. Rekan, 11, is of short stature. According to Yezda, this is due to a health condition that resulted in the misalignment of his bones, which has impacted his growth. Yezda’s other son, Mustafa, 14, lost his left foot and experienced a severe injury to his right leg after stepping on a landmine in October 2020.[57]

At the time of Mustafa’s injury, Yezda was the sole breadwinner, earning only USD $17 per month teaching Kurdish, so she could not afford proper health care for her family. She expressed her worries:

I am suffering a lot because of my youngest child [Rekan]. I do not know what is exactly happening. I have no money to take him to any doctor to explain and help.[58]

Yezda stopped teaching to take care of Mustafa, forfeiting the family’s only income. Although their house partially burned down during the conflict, they have continued to live there due to their lack of other options.[59]

Syrian girls, including girls with disabilities, can be at risk of child marriage due to poverty, as families often see marrying off their daughters as a way to alleviate financial pressures. The UN Syria Commission of Inquiry noted that the fragile economic situation, among other factors, contributed to child marriage.[60] It reported that a 12-year-old girl with physical disabilities was married off in Douma, Damascus governorate, for these reasons.[61]

Amina became a single mother after her husband died in prison. She has a son and six daughters, including Aya, a 12-year-old who acquired a physical disability after she was injured during an airstrike on Taftanaz, Idlib governorate.[62] Amina had married off four of her daughters at the ages of 14 and 15 because she was unable to find a job and provide for them.[63]

Aya, who was in second grade at the time of her interview, enjoys school and dreams of becoming a doctor, but she recognizes she needs help and support to achieve her goal.[64] “I wish they would help the kids in Syria, and I wish the war would end,” she said. “I wish for the people who are reading this report, and all the kids in the whole world, to live in peace and in safety.”[65]

Human Rights Watch also documented one case of a child, Ismail, who was sold as an infant, although it is unclear if poverty factored into the relative’s decision. Human Rights Watch interviewed Aisha, Ismail’s cousin, who at the time of the interview was taking care of Ismail, 4, and Farah, 6.[66] Aisha believes Ismail began to stutter as result of his trauma.

Ismail’s parents were killed in the war when he was about 2 or 3 months old, and his uncle sold him to another family. Aisha’s family spent three-and-a-half years looking for Ismail before they found him. According to Aisha, “Ismail is a very scared child. He is scared by everything: voices, people, anything you can imagine. If someone is just passing by him, he will startle and get scared.”[67]

Right to an Adequate Standard of Living

The Syrian government has an obligation under international human rights law to respect, protect, and fulfill the right to an “adequate standard of living,” which includes the rights to housing, food, and health.[68]

The principle of non-discrimination is a foundation of international human rights law and includes a prohibition against discrimination on the basis of disability.

The CRPD underscores that people with disabilities have a right to an adequate standard of living for themselves and their families, “including food, clothing and housing, and to the continuous improvement of living conditions.”[69]

The CRPD obliges states to take steps to safeguard and promote the realization of equal access to water services and to appropriate and affordable services, devices, and other forms of assistance that are needed because of a disability as well as access to social protection and poverty reduction programs. These programs are especially important for women and girls.[70]

Syria has a duty to progressively realize these rights over time. Even recognizing that limited resources and capacity may mean that these rights are realized over time, it still violates Syria’s core obligations to fulfill people’s needs in a discriminatory manner or to impose unnecessary barriers on the delivery of aid or the pursuit of development projects.

Lack of Access to Health Care and Support Services

The majority of children included in this report were born when or shortly before the conflict began in 2011; consequently, their lives have been overwhelmingly shaped by the armed conflict and the violent attacks, displacement, and degradation of essential and other services that have characterized it. They have lacked access to basic services essential to the enjoyment of their human rights, including health care and social services.

Parents of children with disabilities interviewed for this report described obstacles to accessing health care, including the lack of healthcare facilities near them and the high cost of accessing what little care is available; early intervention services; rehabilitation; and other services, including those that might have helped their children and prevented them from developing further disabilities.[71]

All the parents who spoke to Human Rights Watch had not received information about their children’s disabilities or how they can support them. They were also unable to secure health care and services to address their children’s physical and emotional development needs.

Eleven years of conflict in Syria has decimated the healthcare and social services infrastructure: more than one-third of essential infrastructure has been destroyed or damaged, including half the healthcare facilities.[72] Syrians with disabilities have faced particular obstacles in accessing the healthcare services they need, and the Covid-19 pandemic has exacerbated these disparities.[73] According to the 2022 Humanitarian Needs Assessment, households who have had a member with a disability were most likely to report living more than one hour away from a health facility, having to pay for health care, a lack of available or accessible services, and fear of becoming infected by Covid-19 at the health facility.[74]

According to a humanitarian protection officer in Syria, there is a lack of medical professionals who can treat spinal cord injuries and bone conditions. Consequently, some children and adults were unable to get surgeries and early interventions that would have helped prevent further disabilities.[75]

Yousef is the father of eight, including 8-year-old Taha who experiences seizures and faints often. The family fled Hama and have been living for four years in a tent in Samidun camp, Idlib province. He said the “main problem” is they have not had access to health care or services where they could ask for information on Taha’s disability and guidance on how to support him.[76]

The father of a 5-year-old with autism, who lived in Qunaya at the time of the interview, on the Syria-Turkey border, similarly expressed his wishes to learn about his son’s disability and how to support him:

He is still young, and there is probably something we can do. What if it continues like this? It feels like I am just sitting there, unable to do anything. I am looking at my child, and I do not know how to support him. What can I do? Will he grow up with no access to education or support? I have so much fear about what will happen.[77]

According to Merwa, the mother of two daughters with hearing disabilities, the biggest challenge of living in a war-affected country and having children with disabilities was the lack of access to education, health care, and support. In 2017, she managed to take her daughters to Turkey to get cochlear implants, which are small electronic devices that improve the transfer of audio information from the ear to the brain.

Merwa said:

Doctors [in Turkey] told me we have to come back after two to three months, but since the operation, I haven’t been allowed to go back to Turkey to see the doctors again. I’ve asked around here to be able to get some support, went to Damascus twice to see doctors. Now it’s been a while, but I still haven’t managed [to get a follow up doctor’s visit since the surgery].[78]

Access to health care and early identification and intervention programs are necessary to improve the health and development of all children, especially children with developmental conditions and disabilities.[79] When children with developmental conditions and disabilities cannot access health care, rehabilitation, and early intervention programs, their conditions may become more complex or they may acquire further disabilities. Early and timely identification of children with developmental conditions and disabilities and consequent intervention can help the children’s development and provide their families with the necessary skills and knowledge to ensure their development and to pursue access to appropriate services throughout their childhood and adolescence.[80]

Lack of Support for Children’s Mental Health

Research on conflicts around the world indicates all children living in conflict zones are at high risk of depression, anxiety, and other mental health conditions.[81] A lack of access to support, mental health and psychosocial support services, and education exacerbates the impact of conflict on the mental health of all children, including children with disabilities.[82] These global findings are reflected in Human Rights Watch interviews with parents in Syria, who described the devastating impact of the conflict on their children’s mental health.

Available data indicates nearly half of all Syrian children display symptoms of post-traumatic stress (PTSD) and about 7.5 million Syrian children and adolescents are currently in need of mental health support.[83]

The 2022 UN Humanitarian Needs Overview emphasized the mental health impact of the conflict on children in Syria, noting that many children do not know “anything else but years of crisis.”[84] Signs of psychological distress were found to be highest when the head of household is a person with a disability and second highest for female-headed households.[85]

All families interviewed described evidence of psychological harm in their children, particularly in those with a disability.

Dib H., the father of the 13-year-old boy with a developmental disability, said:

Most of my kids have a lot of difficulties psychologically, especially when it comes to any loud sound. You can see the fear in their eyes. They have no hopes for the future.[86]

Regarding his son with disabilities, Dib H. said: “This situation made him more withdrawn. He sits alone, doesn’t want to interact with any other kids.”[87]

Thara J., 18, who lost her leg in a barrel bomb attack, fears future harms and airstrikes:

With every airstrike, I feel I might lose my life or another limb. I am still seeing my people being killed, injured, and disabled because of this conflict. Psychologically I don’t feel well, but we will support each other and keep hoping that this conflict will end one day.[88]

Zaher A. lives with his wife and three children, including a 10-year-old boy who has an intellectual disability, in a tent in a camp on the outskirts of Idlib. He said the multiple military offensives in the region particularly affected his son with a disability:

He was always shy, but the war made it worse. He witnessed a lot, especially bombs and explosions. He changed a lot. He is always afraid, including when it’s something he shouldn’t be afraid of. Sometimes it will be the sound of thunder or the sound of the fire. He is afraid of everything.[89]

The sudden attacks and fleeing also profoundly affected Shahd (her real name), 11, who has a hearing disability, compared with her five siblings. Her father, Ahmed, described her reactions:

Whenever there was airstrike, the children became terrified, and we started yelling and trying to run to the shelters, and when she saw us in that situation, she started to cry. Now whenever there is something unexpected, even if someone rushes into the house, she starts to cry.[90]

Several parents believed the lack of access to meaningful intervention, support, and education further exacerbated the developmental and psychological impact on their children with disabilities. The father of the 4-year-old boy with autism, who lived in a makeshift camp on the Syria-Turkey border, said there were no support or educational services available for his son with autism:

He does not know how to communicate with us, we do not know how to communicate with him, and there is nowhere to look for support. Recently, we see a lot of aggressiveness, even when I try to speak and engage with him. Whatever he finds on the ground around him, he throws that at me. We are very worried; we do not know what to do. I was hoping that by coming to this area, we will have access to education for him, but there is nothing.[91]

When Human Rights Watch interviewed the father again in June 2022, the family had moved to a rural area of Harem district and continued to struggle to find appropriate and quality services and education for their child with autism.

Nour lives in Afrin with her son who is 11 and has an intellectual disability. When her son was 6 months old, Nour regularly took him to a public special school for children with disabilities in Aleppo that provided free early childhood intervention services.

“Teachers there were not only teaching him, but also teaching and helping me, giving me hope, explaining what was going on,” she said.[92] However, due to fighting in the area and inaccessible roads, Nour stopped taking her son to that school when he was two-and-a-half. Nour said she has not been able to find another school that would accept him and that not going to school has impacted his mental health. “From my perspective, it changed him a lot,” she said. “His situation became worse. He became very angry; he started hating staying at home.”

All but one person said they and their children have not had access to mental health and psychosocial support services. The one parent whose child had access to psychosocial support told us the program closed in 2019.[93]

Two organizations providing psychosocial support services to children in Syria confirmed their programs were not accessible to all children with intellectual or psychosocial disabilities. For example, a staff member from one organization explained they were not prepared to provide services to children with high support needs because “a child with a ‘severe’ intellectual disability needs intensive care and very qualified and specialized facilitators to maintain the principle of ‘do no harm’” that their organization cannot offer right now.[94]

A representative of another NGO, Violet Syria, said many of their educational activities and child-friendly spaces exclude children with disabilities due to a lack of trained staff inside Syria: “Our staff often complain that they do not know how to [support children with disabilities], that they need special approaches and special modules, and we do not have enough capacity for this.”[95]

Right to Physical and Mental Health

The Syrian government has an obligation under international human rights law to respect, protect, and fulfill the right to health, including for children with disabilities.[96] Under the CRC and CRPD, children with disabilities have the right to health and nutrition. Children with disabilities are also entitled to appropriate assistance, including support for their parents or other caregivers.[97] According to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, a body of eighteen independent experts that monitors the implementation of the CRC, states parties should pay particular attention to ensure the “most vulnerable groups of young children and to those who are at risk of discrimination,” which includes children with disabilities, have access to services.[98]

The UN Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health called on states to increase their investment in early childhood health and development and to ensure health care and early intervention services follow a human rights-based approach, including provisions of the CRPD.[99]

As part of their right to health, all children, including children with disabilities, have the right to enjoy the highest attainable standard of mental health and, as needed, access to psychosocial services.[100] Counseling and other mental health services in Syria, which are mostly offered by humanitarian organizations, should be human rights respecting, equitably distributed, inclusive of, and accessible to all children with disabilities.

Lack of Access to Assistive Devices

Children with physical and sensory disabilities in Syria cannot easily access adequate and affordable prosthetics, wheelchairs, hearing aids, or other assistive devices.

Thara J., 18, said that in the five years since she lost her leg, she has not been able to receive a prosthetic leg that would help her get around more easily.[101] Two 16-year-old boys who each lost a limb after stepping on mines, one in October 2020 in Kobani and the other in 2016 in northeast Syria, also did not have access to prosthetics.[102]

A surgeon who treated the 16-year-old who lost a leg in Kobani, told Human Rights Watch he could not provide prosthetics to children who lost a limb or outgrew their old prosthetic due to a lack of access to necessary materials.[103]

The other boy now lives with his family in Rukban camp, northeast Syria. The camp is located between Jordan and Syria, where horrific humanitarian conditions persist as a result of the refusal of both the Jordanian and Syrian authorities to allow access for aid.[104] Consequently, he cannot access a prosthetic leg despite the enormous impact it would have on his life:

A prosthetic leg would help a lot. It will help me with everything. It will help me to come and go without having to ask other people for help. It will help me emotionally. Today, I cannot go, I cannot do anything alone. I need to have my father there to help me, even to walk.[105]

In February and March 2021, two child protection managers working in humanitarian relief in northwest Syria told Human Rights Watch that their organizations have not typically provided prosthetics to children.[106]

“It is not sustainable for children because as they grow, they will need a new one and we do not have resources,” one of them said.[107] Thanks to increased funding, the other’s organization did start providing prostheses to children in 2020, but only for lower limbs. She said, “There is no funding for upper artificial limbs, even though children need these as well.”[108]

If a child has an assistive device, it should meet their needs to prevent further complications. Due to a lack of such access, the children included in this report who had access to assistive devices rarely had ones that were tailored or appropriate for their needs.

Alaa, 4, has a developmental disability and was living with her family in an IDP camp north of Aleppo governorate when Human Rights Watch spoke to her mother. Alaa cannot walk without support and was provided with a wheelchair. A photo of the wheelchair shows Alaa sitting in an adult wheelchair that is not appropriate for her age and disability, according to World Health Organization guidelines.[109]

According to an inclusion specialist at Humanity & Inclusion, an international NGO, inappropriate assistive devices may lead to irreversible health implications and put children with disabilities at risk of developing further disabilities. The inclusion specialist explained that Alaa is unable to independently use her adult wheelchair and may develop spinal and joint complications in the future due to sitting in a wheelchair that is not fitted for her needs or age.[110] “Such non-tailored services can harm children with disabilities,” she stressed.

One protection officer explained that adult manual wheelchairs are less expensive than wheelchairs that are adapted to children or a specific individual’s needs, such as electric wheelchairs. Electric wheelchairs would be better suited to the terrain in Syria, where roads are damaged and difficult to navigate with a manual wheelchair. The protection officer also said that donors, in an effort to increase the numbers of devices offered, may not prioritize adapted and electric wheelchairs. “Donors prefer to say they donated 300 wheelchairs versus 10,” she said.[111] She added that “the numbers of children who need assistive devices is larger than what we can respond to” and the lack of access to assistive devices can impact a child’s access to school.[112]

Assistive Devices Facilitate Enjoyment of Rights

Assistive devices positively contribute to a child’s independence and development, promoting social inclusion and facilitating access to other rights, including to education and to health.[113] Under the CRPD, states parties should take effective measures to ensure personal mobility, including by facilitating access to assistive technology and by promoting the availability, knowledge, and use of assistive devices and technologies.[114]

Offering a suitable prosthetic or an assistive device as soon as a child needs it can greatly improve their health, development, independence, and access to education and other services as well as other r rights. Given those benefits, access should be provided regardless of whether it is considered sustainable. A child who gets a prosthetic that they can use—even for only a year—is more likely to have better health and possibly more able to do things to get access to a replacement, such as travel, than one who never gets one at all.

Lack of Access to Education

An estimated 2.5 million children are out of school in Syria.[115] The lowest school attendance rates are in governorates that have seen high levels of destruction of educational facilities and schools being used as IDP shelters or for other non-education purposes.[116]

Since the conflict began in 2011, more than 7,000 schools in Syria have been damaged and destroyed.[117] There is an estimated 1 functioning classroom for every 53 school-age children.[118] Existing schools are characterized by unsafe infrastructure, including absent walls, roofs, staircases, windows, and heating and are severely overcrowded.[119] From the beginning of 2020 to May 2021, there were 37 attacks on educational facilities in northwest Syria despite the ceasefire.[120]

Lack of Access to Formal Education

Children with disabilities in Syria have very limited access to formal education.

IDP households with a head of the household with a disability or a child with a disability reported “slightly lower attendances compared to the overall IDP population and are also less likely to prioritize educational needs.”[121] Children with disabilities are also less likely to be enrolled in schools than other children: 50 percent of children with reported health conditions, injury, or disability reported attending school, compared with 84 percent of other children.[122]

The primary reasons for this exclusion of children with disabilities from education in Syria are: economic constraints, limited educational facilities that can provide an inclusive education, insufficient investment in learning facilities, an inclusive curricula, and social stigma, as well as a lack of accessibility to and within schools, assistive devices, and trained teachers.[123] There is limited availability of early childhood education centers as well.[124]

Among the children with disabilities included in this research, only one was enrolled in formal education (in a school). However, this child was bullied and the school did not provide him with an appropriate accommodation. In all but three families, the other children (without disabilities) attended school. According to parents and representatives of humanitarian organizations, public schools often reject children on the basis of their disabilities, citing a lack of resources or skills to educate them.

Merwa, who has two daughters with hearing disabilities, said schools in Afrin refused to accept her daughters. “The school where I tried to register my children was a public school,” she said. “The teachers there told me they cannot teach my daughters because they do not have a specialist.”[125]

Mona, mother of a 5-year-old with developmental disabilities, tried many times to enroll her daughter in a school, but the school said her daughter “has many problems and that they cannot accept her.”[126]

The mother of a 10-year-old boy with Down Syndrome, who lives in Idlib governorate, discussed his enrollment challenges:

When he reached school age, I tried to register him, but we faced a lot of problems. Other children hit him, beat him, bullied him, many times. The reaction of the teacher was no better. Many times [the teacher] said she is not ready to have a child with a disability in her class, that it’s something that will disturb the class and something she cannot handle.[127]

At the time of the interview, her son was not enrolled in school.

Four parents interviewed for this report did not try to enroll their child with a disability in public school because they believed that the child would not be included due to their disability or that the school would not support a child with a disability if they were bullied or injured.

Mohammed R. has three children, including an 11-year-old boy with a developmental disability. They live in a tent in a makeshift camp north of Aleppo. He never tried to send his son to school “because he needs someone to be with him all the time” and he believed the school would not provide a support person to accommodate his son.[128]

Yousef and his wife, who have an 8-year-old son who has seizures and faints often, fear their son will not receive appropriate support if he had a seizure at school. “Sometimes, some of his brothers or sisters take him with them, but he is unable to go to school or to stay there alone,” Yousef said.[129]

Some children experienced a lack of support from teachers that prevented them from going to school. The family of Omar, a 10-year-old boy with intellectual disabilities, sent him to school in Idlib governorate twice. However, according to his uncle, “the teacher couldn’t respond to his needs, so it was hard for us to keep him in the school.”[130]

Ghaith (his real name), 13, was the only child with a disability included in this report who was in school. He has a visual disability and lives with his family in a rural area in Idlib governorate. He attends school, where his favorite subject is Arabic, especially poetry, but it is hard for him when teachers want to put him in a class with younger children:

The teacher pushes me to a lower grade because of my writing. I do not see well [enough] to be able to write. I don’t want them to keep pushing me to a lower grade; I want to stay in my class. They should have patience and give me more time to write instead.[131]

His mother has had to go back to the school to fight the teacher’s decision to put him in a lower grade.[132] She also said Ghaith is bullied by other children at school, which is one of the hardest things for her to witness.[133]

“The hardest thing is witnessing the bullying from other children. He also stopped going to the mosque because of the children. They [the children] point out that he is wearing glasses and say words that a child cannot bear. Same happens at school as well.”[134]

Poverty played an important role for families interviewed for this report. Families living in rural areas said they could not send their children with disabilities to school because of the transportation costs.[135] Two humanitarian workers confirmed transportation is one of the main barriers to accessing education and support services, if available.

Abdel, 10, who has a developmental disability, did not receive proper support from a local school in Afrin, where teachers insisted he attend class with much younger children. His parents considered a private special school, but this was not a viable option due to economic constraints and distance.[136]

Fear of possible new attacks and violence was a concern for the parents of Thara J., who lost a leg at 13. She stopped going to school afterward since her family worried she would not be able to flee. “I was in seventh grade when I dropped out of school,” she said. “I wish one day I can enroll in school again.”[137]

Limited Access to Informal Education

With very limited access to formal education or formal early education programs for children with disabilities in Syria, most children whose situations Human Rights Watch documented relied on educational services provided by humanitarian organizations. Parents interviewed praised these programs for providing not only opportunities for their children to learn and socialize, but also for the information and support to parents themselves.

However, the lack of long-term funding has often led organizations to close or reduce their programming.[138] The Covid-19 pandemic has led to some programs to move online at the beginning of the pandemic, with many in-person activities resuming in early 2021.[139] In other cases, the inability to travel to available educational programs due to poor accessibility in homes or the cost of transportation impeded the participation of children with disabilities.[140]

Dib H., whose 13-year-old son has developmental disabilities, said his son had access to services, including education and physical therapies provided by Sened, an NGO committed to providing support to people with disabilities, in the Syria-Turkey border camp where their family lives. The services meant a lot to his child and to him as a parent. “Before going to these educational trainings, [my son] didn’t speak,” Dib H. said. “Then he learned. When he would return home, he would be excited to explain what happened during that day.”[141] However, a few months into the program, the program ended due to financial reasons, and Dib H. had nowhere else to turn for educational opportunities for his son.

Ahmed, whose 11-year-old daughter has a hearing disability, said they were able to access six, helpful, informal classes provided by the Union of Medical Care and Relief Organizations (UOSSM), a coalition of humanitarian, non-governmental, and medical organizations. “They also taught us [the parents] how to support our children,” he said.[142]

However, like Sened’s program, UOSSM’s classes were canceled after six sessions due to lack of funding. Ahmed’s daughter Shahd was not attending any classes when we spoke in October 2021. Ahmed explained how the lack of ongoing support harmed her mental health:

It’s very hard on her: she is growing up, and she wants to be able to explain herself and say what she feels or need. We do not understand what she needs most of the time. Not even other children her age understand her. She then gets angry and frustrated because we do not know what she needs or wants.[143]

When Human Rights Watch interviewed Ahmed again in June 2022, after his family had moved to Azaz, Aleppo, Shahd was going to the school her brother was attending once a week “just to pass time.”[144] He explained she is not learning anything due to a lack of access to trained teachers, so he fears she will grow up without an education.

Zaher A., who has a 10-year-old son with an intellectual disability, said his son accessed informal classes provided by UOSSM for two months in 2020 and that “classes were helping him a lot. We saw improvement, and I am devastated they stopped” as a result of financial restrictions the organization was facing, according to Zaher A.[145]

Goufran M., whose 5-year-old has autism, benefited from the educational specialist at Sened, who taught her how to support her son. She also spoke about the positive changes she noticed when he briefly attended informal classes offered by Sened in early 2020.[146]

I started seeing progress. It gave us hope.… What he got from these classes was more than learning letters and numbers: It had a social impact on him, being surrounded by other children.… I’ve seen a lot of change in his well-being since he had to stop going to these classes.[147]

Goufran M. felt that access to this support was lifechanging for her and her family, since they previously had no one to consult except some medical doctors, who often dismissed her son and his potential. According to her, “One doctor said, ‘[my child’s autism] is a broken plate, something that cannot be fixed.’ Whenever a doctor tells me my child is a hopeless case, I just stop going there.”[148]

Limited Frequency and Accessibility of Classes

While children with disabilities and parents of children with disabilities who had access to any informal classes spoke highly about these classes, they all wished the classes were offered more frequently. Musa, the 13-year-old boy with a physical disability, goes to the classes offered by Sened and expressed his joy from the opportunity: “I am very, very, very happy going there. I only wish I could go there every day.”[149]

In November 2020, Mohammed R. told Human Rights Watch that his 11-year-old son with a developmental disability had been attending Sened’s classes for two months. “I am very grateful,” he said. “I think my child is doing better, but I know he needs more than one class per week. He needs to be there more frequently.”[150]

Transportation fees prevented Mohammed R.’s son and other children with disabilities from attending more often. An education specialist from Sened confirmed transportation was a key obstacle for children with disabilities to attend classes at the center.[151]

Some families described long travel times to reach informal educational programs. Fatima J., who lives in Afrin with her 11-year-old son with an intellectual disability, described her journey to a service center:

It is very hard to do it. I usually take a bus, which is expensive. I must leave the house at 7 a.m. to arrive there at 9 or 10 a.m. There are many checkpoints, and it always takes a long time. But I am still doing it for the future of my child. All I am hoping and doing for him is so that he can be independent.[152]

Musa, the 13-year-old who uses a wheelchair, lives with his family on the fourth floor of an unfinished house without walls. Living on the fourth floor makes it difficult for him to leave the home. His mother said:

I put him in a chair and ask some men to take him downstairs. He is around 70 kilograms. His body is strong, so carrying him downstairs is not easy. He doesn’t go down often. About two months ago, Sened came and requested we take him down to register him. We bring him down twice a week so he can go to Sened to attend classes.[153]

Parents also recounted how some humanitarian organizations operating in areas where they lived excluded their children with disabilities. Two humanitarian organizations providing informal education services to children in Syria confirmed they turned away children with hearing, visual, or intellectual disabilities. “We are referring these children to other NGOs because they need special education,” said one humanitarian worker.[154]

Right to Education

The Syrian government has an obligation under international human rights law to respect, protect, and fulfill the right to education of all children, including children with disabilities. The CRC guarantees the right of the child to education, progressively and on the basis of equal opportunity.[155] The CRPD guarantees people with disabilities access to inclusive primary and secondary education in the communities where they live.[156] States parties should provide reasonable accommodation to address individuals’ educational requirements.[157]

Children with disabilities have the right to not be segregated from others and to an inclusive education on an equal basis with others. The CRPD guarantees the right of students with disabilities to receive an education in mainstream, inclusive schools. Organizations providing education and other services should strive to ensure staff and training to guarantee inclusion.

The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) states that:

As an antidiscrimination measure, the “no-rejection clause” has immediate effect and is reinforced by reasonable accommodation … forbidding the denial of admission into mainstream schools and guaranteeing continuity in education. Impairment-based assessment to assign schools should be discontinued and support needs for effective participation in mainstream schools assessed.[158]

The high number of children with disabilities who are out of school in Syria presents an urgent crisis. Many schools have been destroyed or damaged and what teachers are left have limited support and resources and little to no access to training to educate children with disabilities. It might take years for children with disabilities to have equal access to education. Importantly, the longer children remain out of school, the less likely they are to finish their education and the more likely they are at serious risk of experiencing poverty and exclusion in adulthood.[159]

Stigma and Discrimination

Children with disabilities can face isolation and discrimination in situations of armed conflict around the world.[160] Human Rights Watch research in Syria found stigma and discrimination against children with disabilities, including physical and verbal abuse and threats, and one case of shackling.

The UN Human Rights Council has expressed concern that people with disabilities along with women, children and older persons, are among the most at risk of abuse and violence in Syria.[161] In March 2022, OCHA reported that female-headed households and households headed by a person living with a disability in Syria are more likely to report safety and security concerns related to threats of exploitation and abuses (including sexual in nature) than male-headed households.[162]

Children with disabilities in Syria are “often at heightened risk of forms of violence, abuse, neglect or exploitation,” with many “struggling against marginalization, stigma and discrimination,” according to OCHA.[163] The report added that “attitudinal, physical and humanitarian service-related barriers intersect and compound one another to reduce health and learning outcomes, protection and development of children and adults with disabilities, often resulting in life-long negative consequences.”[164]

Eleven of the parents interviewed for this report said their child with a disability faced bullying and harassment in the community on the basis of their disability, and five parents said other children had physically attacked their child with a disability.

Fatima J. described a few experiences where she and her 11-year-old son faced discrimination and bullying linked to his intellectual disability:

It’s not just kids who bully him; the adults do too. They act like they are scared of him. Their reaction to meeting him is always bad. Even here in the area where we live now, there was a woman who was pregnant who passed by us with her friend. Her friend said, ‘Don’t look at the child while you are pregnant, so you don’t have a child like him.’ This made me cry, it really hurt me. This is harder than anything else he is going through. A lot of people are like that here.[165]

She continued:

I hope for everyone in the world to understand that children with disabilities are like other children. They have their rights that include being treated like other children and not being looked down on. They have the right to and need for education.[166]