In 2019, Tunisia witnessed its second legislative and presidential elections since adopting a new constitution in 2014. During the campaign, candidates focused on debating reforms to the economy and government social programs and devoted less attention to individual liberties and addressing past human rights violations.

First-time candidates shook up the electoral races, and legislative and judicial measures that seemed designed to undermine the most prominent among them cast a shadow over the integrity of the process.

The death in office in July of President Beji Caid-Essebsi highlighted the dangers of the continuous absence of the constitutional court, since that constitutionally-mandated institution could have addressed conflicts that arose in interpretations of the constitution over situations when a president is unable to fulfill his functions. The constitutional court’s absence also undermined rights protections, because it was not there to rule on the constitutionality of repressive laws.

A state of emergency remained in effect throughout the year, renewed by President Essebsi and then by interim President Mohamed Ennaceur.

Implementation of the Constitution

Parliament failed again in electing its allotted quota of Constitutional Court members, impeding the election and nomination of the rest of the members by the Supreme Magistrate Council and the president of the republic, respectively.

The absence of the court translated into the continuing application of repressive legislation, such as laws criminalizing speech, without the chance of appealing their constitutionality. Parliament amended the electoral law a few months prior to elections in a way that seemed designed to exclude specific presidential and legislative candidates through measures applied retroactively. A constitutional court, if it existed, would likely have subjected the electoral law amendments to constitutional scrutiny. In any event, the law did not take effect because the president of the republic did not sign it.

Parliament has also failed to elect members of several other constitutional authorities, such as the Human Rights Commission and the Commission on Corruption and Good Governance.

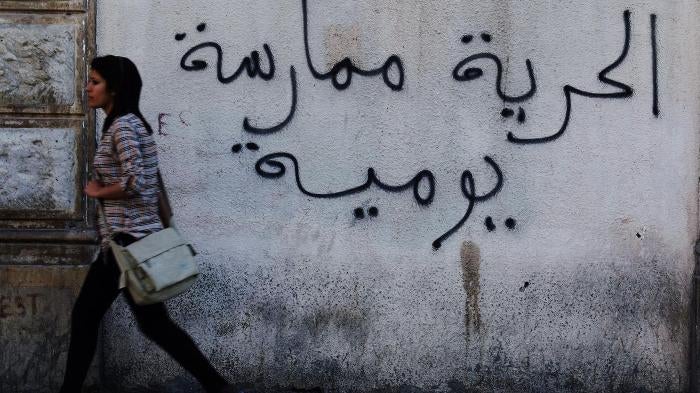

Freedom of Expression, Association and Assembly and Conscience

Tunisian authorities continued to prosecute peaceful expression on the basis of repressive articles in the penal code and other codes, despite adopting, in November 2011, Decree Law 115 on freedom of the press that liberalizes the legal framework applicable to written media. The ongoing prosecutions affected whistleblowers and would-be whistleblowers.

On May 28, police arrested Yacine Hamdouni at his home in Tunis. They brought him to the Anti-Crime Police Brigade in Gorjani and interrogated him about two Facebook posts from May 2019. In those posts, he accused a senior security official of corruptly using an official car for private purposes. On June 6, a Tunis First Instance court convicted Hamdouni of defamation, dissemination of “false information,” accusing officials of wrongdoing without providing proof, and “harming others via public telecommunication networks,” and sentenced him to one year in prison, reduced to six months on appeal.

Authorities also undermined freedom of conscience by using a vague provision of the penal code on “publicly offending morality” to convict café owner Imed Zaghouani on May 29, 2019, for keeping his café in Kairouan open during Ramadan fasting hours. Zaghouani spent 10 days in jail before a court sentenced him to a suspended term of one month in prison and a fine of 300 dinars (US$100).

The National Registry of Organizations law, adopted in 2018, requires new and existing associations to comply with new registration procedures, as part of Tunisia’s response to the International Financial Action Task Force (FATF) 2017 report, which called Tunisia deficient in combating money laundering and terrorism financing. Some Tunisian associations expressed concern that this new requirement represents a step backward from the liberal 2011 law on associations, which enabled associations to register through a simple declarative act.

Transitional Justice

Tunisia adopted legislation in 2013 to address crimes of the past, which included the creation of a Truth and Dignity Commission. The commission was mandated to investigate all serious human rights violations from 1955 to 2013 and is designed to provide accountability for torture, forced disappearances, and other abuses of the past. During the years it operated, from 2013 to 2018, the commission received more than 62,000 complaints and held confidential hearings for more than 50,000 of these.

On March 26, the commission published its five-volume report analyzing and exposing the senior officials and state institutions responsible for systematic human rights abuses over five decades. The commission outlined the role of former presidents Habib Bourguiba and Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali and others in torture, arbitrary detention, and numerous other abuses. The commission documented abuses not only against political opponents but against their families, including sexual assaults of the wives and daughters of opposition members. The commission named President Caid Essebsi, who died later in 2019, as complicit in torture when serving as the interior minister for Bourguiba, from 1965 and 1969.

The law also tasked the commission with referring cases of torture, forced disappearance, and other serious abuses to 13 specialized chambers created within ordinary courts to try those responsible for grave human rights violations committed since 1955. By the end of the commission’s mandate, it had transferred to the specialized courts173 cases of human rights violations, including cases of torture, enforced disappearances, and arbitrary detentions.

The specialized courts opened 38 trials around the country, involving 541 victims and 687 accused. In at least 13 trials, the defendants did not attend; in 16 others, only their lawyers appeared. The first case before a specialized court involved the forced disappearance of Kamel Matmati, an Islamist activist whom the police arrested in 1991. It opened in Gabes on March 29, 2018, and was continuing at time of writing.

Counterterrorism and Detention

The state of emergency declared by President Essebsi in 2015 and repeatedly renewed after a number of attacks by armed extremists remained in effect at time of writing. Essebi first declared the state of emergency after a suicide attack in 2015 on a bus, claimed by the extremist group Islamic State (ISIS), killed 12 presidential guards. The emergency decree empowers authorities to ban strikes or demonstrations deemed to threaten “public order.” Under the decree, authorities have placed hundreds of Tunisians under house arrest.

The government eased conditions of house arrests in 2018. But many who remained under house arrest were also banned from travel under a procedure called “S17,” which the state can impose on any person who is presumably suspected of intending to join an armed group abroad. The procedure allows restrictions on movement both abroad and inside Tunisia. A person placed under the S17 procedure risks lengthy questioning whenever they are stopped at a routine police check.

Interior Minister Hicham Fourati declared on February 7 that he could not provide the exact number of citizens placed under the S17 procedure. He also stated that more than 800 citizens contested the procedure in court, 51 of them winning their challenges.

Violence in police stations or prisons is still present; Tunisian nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) reported tens of cases of alleged torture in 2018. A case of suspicious death took place in Bouhajla, a small town in the region of Kairouan. Police detained peddler Abderrazek Selmi, 58, on June 8, following a dispute with officers. Doctors at a Kairouan hospital pronounced Selmi dead later that day and informed the general prosecutor that Selmi’s death was suspicious, citing injuries to his face and body. Authorities had not released an autopsy report at time of writing, and no charge had been filed in connection with his death.

About 200 children and 100 women Tunisians who are ISIS suspects or family members of ISIS suspects remained trapped without charge in squalid conditions in Libya and Syria. Authorities rebuffed demands by Tunisian family members to bring them home.

Women’s Rights

In 2018, the presidentially appointed Commission on Individual Freedoms and Equality recommended, among other things, equality between men and women in inheritance.

In November 2018, the presidency of the republic submitted a bill to parliament that would provide equality in inheritance. The bill did not advance in 2019.

Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

Despite accepting a recommendation during its Universal Periodic Review at the UN Human Rights Council in May 2017 to end the discredited police practice of administering anal testing to “prove” homosexuality, the government has not yet taken steps to carry out this pledge. Authorities have continued to prosecute and imprison presumed gay men under article 230 of the penal code, which provides up to three years in prison for “sodomy.”

The government has also continued to harass Shams, an NGO supporting sexual and gender minorities. On February 20, the government appealed a 2016 court decision affirming Shams’s status as a legally registered NGO. The government argued that Shams’ objective, as stated in its bylaws, to defend sexual minorities, contravenes “Tunisian society’s Islamic values, which reject homosexuality and prohibit such alien behavior.” It further argued that Tunisian law, which criminalizes homosexual acts in article 230 of the penal code, prohibits the establishment and activities of an association that purports to defend such practices. On May 20, the government lost the appeal.

In July, Tunisia voted at the UN Human Rights Council in favor of renewing the mandate of the independent expert on protection against violence and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity.

Key International Actors

The United Nations special rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief presented the report of his 2018 visit to Tunisia to the Human Rights Council on March 1. The report included recommendations related calling to ensure the Baha’i community’s ability to “to secure legal personality to enable them to manifest their faith,” and decriminalizing consensual same-sex relations.

The United Nations special rapporteur on freedom of assembly and association presented the report of his 2018 visit to Tunisia to the Human Rights Council on June 25. The report recommended reforms to the state of emergency bill, to ensure that it respects freedoms guaranteed by the constitution, and to revise the law on the National Registry of Organizations to exempt associations from its registration requirements.