In February, President Yoweri Museveni, in power for more than 30 years, was declared the winner of the presidential elections. Local observers said the elections were not free and fair, and international electoral observers argued the process failed to meet international standards.

Violations of freedom of association, expression, assembly, and the use of excessive force by security officials continued during campaigns and into the post-election period. Opposition presidential candidate Dr. Kizza Besigye from the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC) was held in preventative detention at his home for over a month while trying to challenge election results.

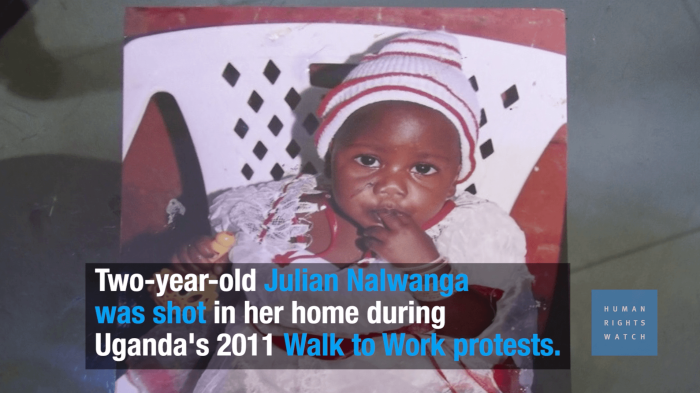

The police used unlawful means including live ammunition to prevent peaceful opposition gatherings and protests, at times resulting in loss of life.

After nine years, the Constitutional Court finally ruled in November on a challenge to a limitation on the mandate of the Equal Opportunities Commission, which barred it from investigating any matter involving behavior “considered to be immoral and socially harmful, or unacceptable by the majority of the cultural and social communities in Uganda.” The judges determined the limitation was unconstitutional and violated the right to a fair hearing. Perversely, this provision had meant that the very mechanism designed to protect people from discrimination could blatantly discriminate against women, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) people, sex workers, and anyone else who might not have been perceived to reflect the views of the majority.

Freedom of Assembly

The police used unnecessary and disproportionate force in 2016 to disperse peaceful assemblies and demonstrations, sometimes resulting in the death of protesters and bystanders.

Police selectively enforce laws, including the 2013 Public Order Management Act, and unjustifiably arrest, detain, and interfere with the movement of opposition politicians. While blocking and dispersing FDC supporters in Kampala, police fired live bullets, killing one person, and injuring many others. Police also shot and killed 13-year-old Kule Muzamiru in Kasese town while dispersing crowds gathered to hear election results. No one had been arrested at time of writing.

Police prevented Besigye from accessing campaign venues in Kampala, in the run up to the February elections on allegations that he was going to “disrupt business.” Police arrested and briefly detained him several times during campaigns before returning him to his home without charge.

Between February and May, police raided and sealed off the FDC headquarters, arrested party officials, and beat supporters on several occasions. The day after the general elections, police closed the party offices and arrested Besigye, as well as other party officials. Police confiscated results declaration forms and computers. FDC party offices remained under police guard as other opposition officials and supporters were arrested countrywide. Some were held incommunicado for weeks and released without charge.

Besigye declared a “defiance campaign” against the government after the election and held a ceremony swearing himself in as president. Police then prevented Besigye from leaving his home for 44 days, under a “preventive arrest” law. Access to Besigye’s home was restricted, and visitors had to seek permission from police leadership.

Eventually in May, Besigye was charged with treason and sent to prison. In July, after the High Court granted bail, police brutally beat Besigye’s supporters and other bystanders with sticks and batons. Opposition activists brought a private prosecution for torture against police leadership, but the case eventually failed.

In June, a newly elected member of parliament for FDC, Michael Kabaziguruka, and 34 others, including soldiers, were charged with treason. The charges were pending at time of writing.

Freedom of Expression and Media

Government officials and police arrested and beat over a dozen journalists, in some cases during live broadcasts. On election day, the Uganda Communication Commission, the telecommunications regulator, directed all telecom companies to block social media networks for “security reasons.” The ban lasted five days.

In January, a local television station was temporarily banned from covering Museveni’s campaign rallies after editors did not use aerial video provided to them by his campaign team. Soldiers from the Special Forces Command stopped the station’s reporters from covering some campaign meetings.

In February, police in Abim, northern Uganda, arrested and detained a BBC correspondent and three others for filming a dilapidated government-run health center. All were released without charge.

Opposition candidates were at times blocked from accessing radios, either for talk shows or after paying for airtime. In January, police blocked opposition presidential candidate Amama Mbabazi from going on the station, Voice of Karamoja. The management told him that the District Security Committee had resolved not to allow him on air.

In April, a court of appeal judge issued a temporary injunction stopping the FDC from carrying out any “defiance campaign” activities pending the hearing of the government’s motion challenging the campaign’s constitutionality. To implement the injunction, the government banned media from reporting on all FDC activities. The ban eventually ended with the expiry of the court interim order.

Extrajudicial Killings and Absence of Accountability

Security forces continue to use excessive force while policing demonstrations and conducting other law enforcement operations. Between February and April, inter-communal fighting prompted in part by local elections in Rwenzori region, western Uganda, led to the deaths of at least 30 people. Human Rights Watch investigations into subsequent law enforcement operations concluded that the police and army killed at least 13 people during alleged arrest attempts. Multiple witnesses said victims were unarmed when killed. There had been no investigations at time of writing.

Freedom of Association

In February, Museveni signed the Non-Governmental Organisations bill into law. Despite undergoing significant improvement during parliamentary debates, the law still includes troubling and vague “special obligations” of NGOs, including a requirement that groups should “not engage in any act which is prejudicial to the interests of Uganda or the dignity of the people of Uganda.” Another provision criminalizes activities by organizations that have not been issued with a permit by the government regulator, fundamentally undermining free association rights. A separate provision provides that violations of the act can lead to jail sentences of up to three years.

Police have not responded to demands for investigations into more than two dozen break-ins at the offices of NGOs, all known for work on sensitive subjects—including human rights, corruption, land rights, and freedom of expression—and for criticizing government policies. In two instances, guards were killed, but no one has been arrested. NGO leadership and relevant government bodies held nationwide consultations to draft implementing regulations for the NGO law, which remained under discussion at time of writing.

Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

Same-sex conduct remains criminalized under Uganda’s colonial-era law, which prohibits “carnal knowledge” among people of the same sex. The new NGO law raises concerns about the criminalization of legitimate advocacy on the rights of LGBTI people.

In August, police unlawfully raided a peaceful pageant that was part of Gay Pride celebrations in Kampala. Police locked the venue’s gates, arrested activists, and beat and humiliated hundreds of people, violating rights to association and assembly.

Police continue to carry out forced anal examinations on men and transgender women accused of consensual same-sex conduct. These examinations lack evidentiary value and are a form of cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment that may amount to torture.

Lord’s Resistance Army

The rebel Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) remains active in central Africa but with allegations of killings and abductions on a significantly lesser scale than in previous years.

Former LRA commander Dominic Ongwen is in the custody of the International Criminal Court’s (ICC). Ongwen is charged with 70 counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity as part of attacks on internally displaced persons’ camps, including murder, enslavement, sexual and gender-based crimes, and the conscription of child soldiers. Ongwen’s trial was scheduled for December 2016. Warrants for four other LRA commanders have been outstanding since 2005; three are believed to be dead. Joseph Kony is the only LRA ICC suspect at large.

Former LRA fighter Thomas Kwoyelo, charged before Uganda’s International Crimes Division (ICD) with wilful killing, taking hostages, and extensive destruction of property, has been imprisoned since March 2009. His trial has been postponed, first to hear challenges to the constitutionality of his prosecution, and then due to delays in operationalizing ICD regulations, problems in disclosure to the defense, lack of funding, and a backlog of electoral petitions. The trial was scheduled to begin by the end of 2016.

Key International Actors

Electoral observers from the European Union (EU) and the Commonwealth expressed concerns over intimidation and harassment of voters and candidates and a lack of independence and transparency during elections.

The United States publicly raised serious concerns over intimidation and abuse during the elections, but no changes to assistance occurred. The US provides over US$440 million annually to support Uganda’s health sector, particularly provision of anti-retrovirals. The US supports the Ugandan army with at least US$70 million for logistics and training for the African Union Mission in Somalia and counter-LRA operations in the Central African Republic, among other efforts. Additional support goes to the Ugandan police’s counterterrorism efforts.

The World Bank committed US$105 million to projects in Uganda in 2016, a dramatic decrease from US$664 million in 2015. In December 2015, the World Bank cancelled funding for a US$265 million road-building project and suspended two others after allegations emerged that construction workers sexually abused children. On August 22, 2016, the World Bank suspended all new lending to Uganda.