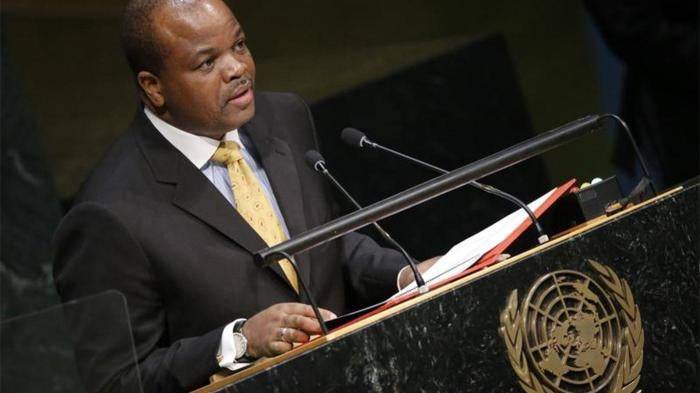

Swaziland, ruled by absolute monarch King Mswati III since 1986, continued to repress political dissent and disregard human rights and rule of law principles in 2016. Political parties remained banned, as they have been since 1973; the independence of the judiciary is severely compromised, and repressive laws continued to be used to target critics of the government and the king despite the 2005 Swaziland Constitution guaranteeing basic rights.

In September, the High Court of Swaziland ruled that sections of the Suppression of Terrorism Act and the Sedition and Subversive Act were unconstitutional and violated freedom of expression and association. The government has appealed the judgement to the Supreme Court, which was pending at time of writing.

Proposed amendments to the Public Order Act and the Suppression of Terrorism Act are under consideration in Parliament but rights activists say that these amendments are insufficient to curb the security services, which have been given sweeping powers by the two laws to halt pro-democracy meetings and protests and to curb any criticism of the government.

Freedom of Association and Assembly

Restrictions on freedom of association and assembly continued in 2016. The government took no action to revoke the King’s Proclamation of 1973, which prohibits political parties in the country. Police used the Urban Act, which requires protesters to give two weeks’ notice before a public protest, to stop protests and harass protesters. In February, police arrested Mcolisi Ngcamphalala and Mbongwa Dlamini, two leaders of the Swaziland National Association of Teachers (SNAT), when they participated in a protest action. Two days later, the police raided their homes.

In February, the police blocked a Trade Union Congress of Swaziland (TUCOSWA) march to parliament to present a petition. In April, the police twice invaded and searched the offices of the leaders harassed leaders of the Swaziland Union of Financial Institutions and Allied Workers (SUFIAWU) without the necessary search warrant. In the same month, the commissioner of police threatened trade unionists with death for unspecified reasons. In June the police assaulted Gladys Dlamini, a trade union activist.

Human Rights Defenders

Political activists faced trial under security legislation and charges of treason under common law. The Suppression of Terrorism Act of 2008 placed severe restrictions on civil society organizations, religious groups, and media. Under the legislation, a “terrorist act” includes a wide range of legitimate conduct such as criticism of the government. The legislation was used by state officials to target perceived opponents through abusive surveillance, and unlawful searches of homes and offices.

Two leaders of a banned political party, the People's United Democratic Movement (PUDEMO), Mario Masuku and Maxwell Dlamini, remained on bail in 2016 pending finalization of their trial on charges under the Suppression of Terrorism Act for allegedly criticizing the government by singing a pro-democracy song and shouting “Viva PUDEMO” during a May Day rally in 2014. The Swaziland High Court granted them bail in July 2015 after more than a year in custody. The trial continued at time of writing. If convicted, they could serve up to 15 years in prison. Both men attended the May Day rally of TUCOSWA in 2016, but their bail conditions prohibited them from addressing the workers.

Freedom of Expression and the Media

The Sedition and Subversive Activities Act continued to restrict freedom of expression through criminalizing alleged seditious publications and use of alleged seditious words, such as those which “may excite disaffection” against the king. Published criticism of the ruling party is also banned. Many journalists practice self-censorship, especially with regards to reports involving the king, to avoid harassment by authorities.

On September 16, the High Court of Swaziland ruled that sections of the Suppression of Terrorism Act and the Sedition and Subversive Act were unconstitutional and violated freedom of expression and association. The invalid provisions relate to the definition of the offences of sedition, subversion, and terrorism. Classification of organizations as terrorist, which the government had used to ban political parties like the People’s United Democratic Movement (PUDEMO), was also ruled to be unconstitutional.

Eight trade union leaders and human rights defenders, including Masuku and Dlamini, had challenged the constitutionality of the Suppression of Terrorism Act before the High Court in September 2015. An appeal by the government against the decision was pending before the Supreme Court.

Rule of Law

Although the constitution provides for three separate organs of government—the executive, legislature, and judiciary—under Swaziland’s law and custom, all powers are vested in the king. Swaziland’s prime minister is supposed to exercise executive authority, but in reality, King Mswati holds supreme executive power and controls the judiciary. The king appoints 20 members of the 30-member senate, 10 members of the house of assembly, and approves all legislation passed by parliament.

The constitution provides for equality before the law, but also places the king above the law. In 2011, the then Swaziland Chief Justice Michael Ramodibedi issued a directive which protected the king from any civil law suits, after Swazi villagers claimed police had seized their cattle to add to the king’s herd.

Women’s Rights

Swaziland’s dual legal system where both Roman Dutch common law and Swazi customary law operate side by side, has resulted in conflicts leading to numerous violations of women’s rights, despite constitutionally guaranteed equality. In practice, women, especially those living in rural areas under traditional leaders and governed by highly patriarchal Swazi law and custom, are often subjected to discrimination and harmful practices.

The government has yet to enact the Sexual Offences and Domestic Violence Bill developed in 2009 to protect women’s rights. Neither has the government amended the Girls’ and Women Protection Act, concerned with sexual abuse of girls under 16, but excludes marital rape. Violence against women is endemic. Survivors of gender-based violence have few avenues for help as both formal and customary justice processes discriminate against them.

Civil society activists have criticized the widely held view among traditional authorities that human rights and equal rights for women are foreign values that should be subordinated to Swazi culture and tradition.

Key International Actors

In August, Swaziland took over the leadership of the Southern African Development Community (SADC), the 15-nation regional economic institution, for a year. Swaziland’s poor and deteriorating human rights record could weaken further the regional body’s ability to press for human rights improvements across southern Africa.

Neighboring South Africa and regional bodies, the SADC and the African Union, have done little to press Swaziland to improve respect for human rights.

The United Nations Human Rights Council assessed Swaziland’s human rights record under the Universal Periodic Review. In May 2016, Swaziland accepted 121 of 181 recommendations made by council member states to improve the human rights environment in the country. Authorities committed to improve protections of freedom of expression and association, and to take action to end child marriage. Swaziland rejected recommendations to end the death penalty and on the protection of migrant workers.

The International Labour Organization (ILO) provided technical assistance to reform repressive laws within the framework of the UN Universal Periodic Review, but achieved little progress towards desired reforms to guarantee freedom of association. The ILO, the Southern African Trade Union Co-ordination Council (SATUCC), and the International Trade Union Confederation visited Swaziland in February to push for reforms.

In 2016, the European Union said it continued to monitor progress towards the implementation of recommendations of the May 2015 European Parliament resolution that called on the government of Swaziland to immediately and unconditionally release Thulani Maseko and Bheki Makhubu, and all political prisoners, including Mario Masuku, President of the People’s United Democratic Movement, and Maxwell Dlamini, Secretary-General of the Swaziland Youth Congress.

The resolution further urged Swaziland authorities to take steps to respect and promote freedom of expression, guarantee democracy and plurality, and establish a legislative framework allowing the registration, operation and full participation of political parties.