In 2013, President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner secured passage of legislation that severely undermined judicial independence, although the Supreme Court subsequently struck down some of its key aspects. A vibrant but increasingly polarized debate exists in Argentina between the government and its critics. However, the Fernández administration has sanctioned individuals for publishing unofficial inflation statistics challenging official ones, and has failed to adopt rules regarding the distribution of public advertising funds. There is no national law regulating access to information.

Other ongoing human rights concerns include police abuse, poor prison conditions, torture, and failure to protect indigenous rights.

Argentina continues to make significant progress on LGBT rights and in prosecuting officials for abuses committed during the country's “Dirty War” (1976-1983), although trials have been subject to delays.

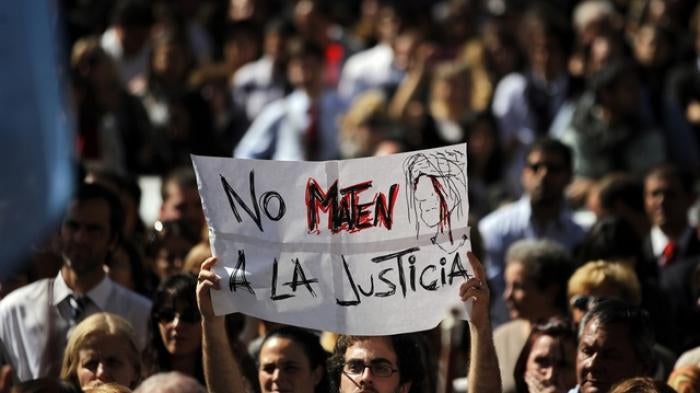

Judicial Independence

In April 2013, President Fernández put forward legislation to revise Argentina’s justice system, which Congress swiftly approved. It included a bill to limit individuals’ ability to request injunctions against government acts, and another that granted the ruling party an automatic majority in the Council of the Judiciary, which selects judges and decides whether to open proceedings for their removal, thereby granting the ruling party powers that undermined judicial independence. In June, the Supreme Court struck down critical aspects of the latter bill, including norms regarding the composition and selection of the Council of the Judiciary.

Fernández accused those who defended the role of the judiciary as a check on other branches of government of being a “check on the people.”

Freedom of Expression

In 2009, Congress approved a law to regulate the broadcast media, which includes provisions to increase plurality in media. The federal authority in charge of implementing the law has yet to ensure a diverse range of perspectives in state-run media programming. Argentina’s largest media conglomerate, the Clarin Group, had challenged the constitutionality of articles of the law requiring companies to sell off broadcast outlets that exceed the new limits of outlets that can be owned by a media company, and obtained an injunction that suspended their implementation during the trial. In October 2013, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the law, lifted the injunction, and ordered Clarin to comply with the law. The court also established clear parameters regarding how the law should be implemented to ensure the right of free expression is effectively protected.

Fernández accused the media in August 2013 of using “bullets of ink” to “overthrow elected governments.” The president’s general secretary called a journalist who aired several shows alleging government corruption of being a “media hit man.”

High fines and criminal prosecutions undermine the right to freely publish information of public interest. In 2011, the Ministry of Commerce imposed a fine of 500,000 pesos on 11 economists and consulting firms for publishing unofficial inflation statistics challenging the accuracy of official ones. While the Supreme Court overturned some of the fines in October 2013, others remained pending at time of writing. Three of the fined economists were also being criminally investigated for allegedly “defrauding commerce and industry.” In September, a judge charged the minister of commerce with “abuse of authority” for having imposed the fines.

The absence of transparent criteria for using government funds at the federal level and in some provinces to purchase media advertisements creates a risk of discrimination against media outlets that criticize government officials. In two rulings in 2007 and 2011, the Supreme Court found that while media companies have no right to receive public advertising, government officials may not apply discriminatory criteria when deciding where to place advertisements.

Argentina does not have a national law ensuring public access to information held by government bodies. An existing presidential decree on the matter only applies to the federal executive branch, and some provincial governments have adopted regulations for their jurisdictions.

Transnational Justice

At time of writing, no one had been convicted for the 1994 bombing of the Argentine Israelite Mutual Association (AMIA) in Buenos Aires that killed 85 people and injured over 300. Judicial corruption and political obstruction hindered criminal investigations and prosecutions from the investigation’s outset. Iran, which is suspected of ordering the attack, has refused Argentina’s requests for the extradition of former Iranian President Ali Akbar Hashemi-Rafsanjani and seven Iranian officials suspected of participating in the crime.

In January 2013, Argentina and Iran signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) that creates an international commission of jurists with powers to review evidence against Iranians accused by Argentine judicial authorities of being responsible for the bombing, and to interrogate some of the suspects. Legislators from Fernandez’s party ratified the agreement in February. In Iran, it was ratified by the Council of Ministers, but it is unclear from the agreement’s vague terms whether it can be implemented without Iranian parliamentary approval, or if the Iranians' statements will be admissible as evidence in Argentine criminal proceedings. In September 2013, President Fernández de Kirchner called on Iran to ratify the agreement during her speech before the United Nations General Assembly. A legal challenge to the agreement filed in April by Jewish community leaders before Argentine courts remained pending at time of writing.

Confronting Past Abuses

Several cases of human rights violations committed during Argentina’s military dictatorship (1976-1983) were reopened in 2003 after Congress annulled existing amnesty laws. The Supreme Court subsequently ruled that the amnesty laws were unconstitutional, and federal judges struck down pardons favoring former officials convicted of, or facing trial for, human rights violations.

By September 2013, out of 2,316 persons investigated by the courts for crimes against humanity, 416 had been convicted and 35 had been found not guilty, according to the Center of Legal and Social Studies (CELS).There are 11 ongoing oral trials involving multiple victims and suspects.

In December 2012, for example, a federal court convicted Jaime Smart, a minister of Buenos Aires province during the dictatorship, for the torture and subsequent death of one individual, and the illegal detention and abuse of 43 others. The first civilian government official convicted for these crimes, Smart was given life in prison. The tribunal also convicted 22 security officials for the same abuses, and requested the investigation of a prosecutor, members of the judiciary, and the Catholic Church for their alleged involvement.

Given the large number of victims, suspects, and cases, prosecutors and judges face challenges bringing those responsible to justice while respecting the due process rights of the accused. Other concerns include significant delays in trials; that three convicted military officers who escaped in July 2013 remain at large; and the unresolved fate of Jorge Julio López—a former torture victim who disappeared in September 2006, a day before he was due to attend the trial of one of his torturers.

In July 2013, President Fernández requested that Congress promote General César Milani, the head of the armed forces, to lieutenant general. After widespread criticism from human rights organizations and victims, who accused Milani of having participated in abuses during the dictatorship, the president asked Congress to postpone Milani’s promotion until the end of the year.

Police Abuse

In April 2013, at least 100 officers from the Metropolitan Police Force of the city of Buenos Aires used excessive force to disperse doctors, nurses, union leaders, and lawmakers who were protesting the city government’s plans to demolish a building at a hospital, according to the city Ombudsman Office. The police intervention resulted in injuries to dozens of civilians, including patients and journalists, according to media accounts. Seventeen police officers were also injured in the clash. At time of writing, the case was under investigation by a criminal judge.

Prison Conditions

Overcrowding, ill-treatment by prison guards, inadequate physical conditions, and inmate violence continue to be serious problems in prisons. According to the National Penitentiary Office (Procuración Penitenciaria de la Nación), an official body created by Congress, there were 86 deaths, including 41 violent ones, in federal prisons between January 2012 and mid-2013. The office also documented 429 cases of torture or ill-treatment in federal prisons in 2012, and 426 in the first seven months of 2013.

Indigenous Rights

Indigenous peoples in Argentina face obstacles in accessing justice, land, education, healthcare, and other basic services.

Existing laws require the government to perform a survey of land occupied by indigenous communities by November 2017, before which authorities cannot lawfully evict communities. In May 2013, the Supreme Court urged the government of Formosa province and the federal government to carry out the required survey for the Qom indigenous group. Before the survey was conducted, authorities opened criminal investigations against Félix Díaz, a Qom leader, for having “usurped” lands where community members live, and for participating in a 2010 protest in which a community member died and dozens more were injured due to excessive use of force by provincial security forces, according to CELS.

Women’s Rights

Argentina adopted a new law in March 2013 extending key protections to domestic workers, the majority of whom are women and girls, including limits to work hours, a weekly rest period, overtime pay, sick leave, and maternity protections.

Abortion is illegal in Argentina, with limited exceptions, and women and girls face numerous obstacles to reproductive health products and services, such as contraception, voluntary sterilization procedures, and abortion after rape (one of the few circumstances when abortion is permitted). These barriers mean that women and girls may face unwanted or unhealthy pregnancies.

In a landmark ruling in March 2012, the Supreme Court determined that prior judicial authorization was unnecessary for abortion after rape and urged provincial governments to ensure access to legal abortions. As of March 2013, only 5 out of Argentina’s 23 provinces had adopted protocols that met the court's requirements, according to the Association for Civil Rights (ADC).

Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

In 2010, Argentina became the first Latin American country to legalize same-sex marriage. The Civil Marriage Law allows same-sex couples to enter into civil marriages and provides for equal rights and the legal protections of marriage afforded to opposite-sex couples including, among others, adoption rights and pension benefits.

In 2012, the Gender Identity Law established the right of individuals over the age of 18 to choose their gender identity, undergo gender reassignment, and revise official documents without any prior judicial or medical approval. The surgical and hormonal reassignment procedures are covered as part of public and private health insurance.

Key International Actors

In April 2013, the UN rapporteur on the independence of lawyers and judges stated that the changes to the justice system proposed by the Fernández administration “seriously compromise[d] the principles of separation of powers and independence of the judiciary, which are fundamental elements of any democracy.” The Fernández government reacted by accusing the rapporteur of “lack of impartiality, restraint, and balance.”

As a returning member of the Human Rights Council, Argentina voted in favour of a number of key resolutions addressing the human rights violations in countries such as Sri Lanka, Iran, and Syria. Argentina could do more to speak out and hold governments accountable for enforced disappearances given their priority focus on this issue at the UN.