Uzbekistan's human rights record remains abysmal, with no substantive improvement in 2010. Authorities continue to crackdown on civil society activists, opposition members, and independent journalists, and to persecute religious believers who worship outside strict state controls. Freedom of expression remains severely limited. Government-initiated forced child labor during the cotton harvest continues.

The judiciary lacks independence, and the parliament is too weak to curtail the reach of executive power. In 2010 authorities continued to ignore calls for an independent investigation into the 2005 Andijan massacre, when authorities shot and killed hundreds of mostly unarmed protestors. Authorities also harassed families of Andijan refugees and in April imprisoned a woman who returned to Uzbekistan four-and-a-half years after fleeing.

While Uzbekistan received praise for cooperating with international actors after the June 2010 ethnic violence in Southern Kyrgyzstan caused nearly 100,000 ethnic Uzbek refugees to flee to Uzbekistan, genuine engagement on human rights remained absent.

Human Rights Defenders and Independent Journalists

Uzbek authorities regularly threaten, imprison, and torture human rights defenders and other peaceful civil society activists. In 2010 the government further restricted freedom of speech and increased use of spurious civil suits and criminal charges to silence perceived government critics.

The Uzbek government has at least 14 human rights defenders in prison, and has brought criminal charges against another, because of their legitimate human rights work. Other activists, such as dissident poet Yusuf Jumaev, remain jailed on politically-motivated charges.

In January 2010 Gaibullo Jalilov, a Karshi-based member of the Human Rights Society of Uzbekistan, was sentenced to nine years in prison on charges of anti-constitutional activity and disseminating religious extremist materials. In August new charges were brought against him, and he was sentenced to two years, one month, and five days in prison after a seriously flawed trial.

Members of the Human Rights Alliance were regularly persecuted and subjected to arbitrary detention and de facto house arrest for their activism in 2010. On February 23 two men brutally assaulted Alliance member Dmitrii Tikhonov, leaving him unconscious after choking and hitting him over the head with a metal object.

On September 16 Alliance member Anatolii Volkov was convicted on fraud charges after an investigation and trial marred by due process violations. He was ultimately amnestied. Another Alliance member, Tatyana Dovlatova, faces trumped-up charges of hooliganism.

On February 10 photographer and videographer Umida Ahmedova was convicted of defamation and insulting the Uzbek people for publishing a book of photographs in 2007 and producing a documentary film in 2008 that reflect everyday life and traditions in Uzbekistan, with a focus on gender inequality. Ahmedova was amnestied in the courtroom.

In October Vladimir Berezovskii, a veteran journalist and editor of the Vesti.uz website, was convicted of similar charges based on conclusions issued by the State Press and Information Agency stating that articles on the website were defamatory and "could incite inter-ethnic and inter-state hostility and create panic among the population."

On October 15 Voice of America correspondent Abdumalik Boboev was convicted of defamation, insult, and preparation or dissemination of materials that threaten public security. A substantial fine was imposed.

The Andijan Massacre

The government continues to refuse to investigate the 2005 massacre of hundreds of citizens in Andijan or to prosecute those responsible. Authorities continue to persecute anyone they suspect of having participated in or witnessed the atrocities. On April 30 Diloram Abdukodirova, an Andijan refugee who returned to Uzbekistan in January 2010, was sentenced to 10 years and two months in prison for illegal border crossing and anti-constitutional activity despite assurances to her family she would not be harmed if she returned. Abdukodirova appeared at one court hearing with facial bruising, indicating possible ill-treatment in custody.

The Uzbek government also continues to intimidate and harass families of Andijan survivors who have sought refuge abroad. Police subject them to constant surveillance, call them for questioning, and threaten them with criminal charges or home confiscation. School officials publicly humiliate refugees' children.

Criminal Justice, Torture, and Ill-Treatment

Torture remains rampant in Uzbekistan. Detainees' rights are violated at each stage of investigations and trials, despite habeas corpus amendments that went into effect in 2008. The Uzbek government has failed to meaningfully implement recommendations to combat torture that the United Nations special rapporteur made in 2003.

Suspects are not permitted access to lawyers, a critical safeguard against torture in pre-trial detention. Police use torture and other illegal means to coerce statements and confessions from detainees. Authorities routinely refuse to investigate defendants' allegations of abuse.

In June Yusuf Jumaev, serving a five-year prison sentence since 2008, was put in a cell with men who regularly beat him. During a harsh beating on June 12 he was kicked in the chest and head, causing his ear to bleed. Prison authorities ignored Jumaev's repeated requests to transfer cells.

On July 20, 37-year-old Shavkat Alimhodjaev, imprisoned for religious offenses, died in custody. The official cause of death was anemia, but Alimhodjaev had no known history of the disease. According to family, Alimhodjaev's face bore possible marks of ill-treatment, including a swollen eye. Authorities returned his body to his family's home at night. They insisted he be buried before sunrise and remained present until the burial. Authorities have not begun investigating the death.

Freedom of Religion

Although Uzbekistan's constitution ensures freedom of religion, Uzbek authorities continued their unrelenting, multi-year campaign of arbitrary detention, arrest, and torture of Muslims who practice their faith outside state controls or belong to unregistered religious organizations. Over 100 were arrested or convicted in 2010 on charges related to religious extremism.

Continuing a trend that began in 2008, followers of the late Turkish Muslim theologian Said Nursi were harassed and prosecuted for religious extremism, leading to prison sentences or fines. Dozens of Nursi followers were arrested or imprisoned in 2010 in Bukhara, Ferghana, and Tashkent: at least 29 were convicted between May and August alone.

Christians and members of other minority religions holding peaceful religious activities also faced short-term prison sentences and fines for administrative offenses such as violating the law on religious organizations and illegal religious teaching. According to Forum 18, at least five members of Christian minority groups are serving long prison sentences, including Tohar Haydarov, a Baptist who received a 10-year sentence in March 2010 for drug-related charges that his supporters say were fabricated in retaliation for his religious activity.

Authorities continue to extend sentences of religious prisoners for alleged violations of prison regulations or on new criminal charges. Such extensions occur without due process and can add years to a prisoner's sentence.

Child Labor

Forced child labor in cotton fields remains a serious concern. The government took no meaningful steps to implement the two International Labour Organization (ILO) conventions on child labor, which Uzbekistan ratified in March 2008.

The government continues to force hundreds of thousands of schoolchildren, some of them as young as ten, to help with the cotton harvest for two months a year. They live in filthy conditions, contract illnesses, miss school, and work daily from early morning until evening for little or no money. Hunger, exhaustion, and heat stroke are common.

Human Rights Watch is aware of several instances when local authorities harassed and threatened activists who tried to document forced child labor.

Key International Actors

The Uzbek government's cooperation with international institutions remains poor. It continues to deny access to all eight UN special procedures that have requested invitations, including those on torture and human rights defenders, and blocks the ILO from sending independent observers to monitor Uzbekistan's compliance with the prohibition of forced child labor in the cotton industry.

A March 2010 review by the UN Human Rights Committee resulted in a highly critical assessment and calls for the government to guarantee journalists and human rights defenders in Uzbekistan "the right to freedom of expression in the conduct of their activities," and to address lack of accountability for the Andijan massacre and persisting torture and ill-treatment of detainees.

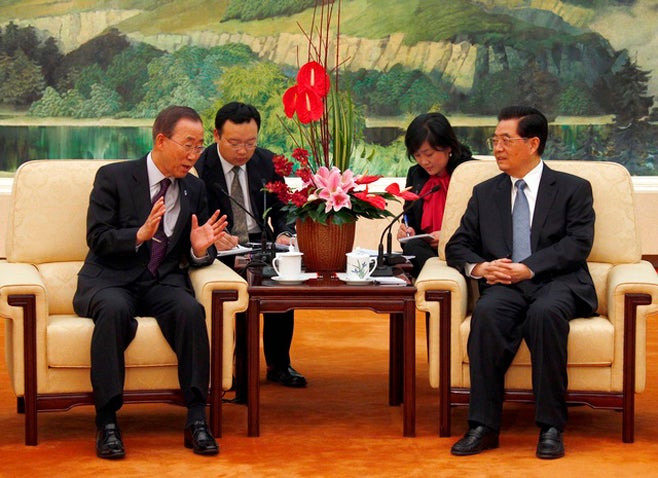

During a visit to Tashkent in April, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon urged the Uzbek government to "deliver" on its international human rights commitments.

The European Union's position on human rights in Uzbekistan remained disappointingly weak, with virtually no public expressions of concern about Uzbekistan's deteriorating record. The annual human rights dialogue between the EU and Uzbekistan, held in May, again yielded no known results and appeared to have no bearing on the broader relationship. In October the EU Foreign Affairs Council reviewed Uzbekistan's progress in meeting human rights criteria the EU has set for it, noting "lack of substantial progress" on areas the council had outlined the previous year when remaining sanctions imposed after the Andijan massacre were lifted. The council reiterated calls for the Uzbek government to take steps to improve its record, including releasing all jailed human rights defenders, allowing NGOs to operate freely, and cooperating with UN special rapporteurs. However, it again stopped short of articulating any policy consequences for continued non-compliance.

The United States maintains a congressionally-mandated visa ban against Uzbek officials linked to serious human rights abuses. However, its relationship with Uzbekistan is increasingly dominated by the US Department of Defense (DOD), which uses routes through Uzbekistan as part of the Northern Distribution Network to supply forces in Afghanistan. US military contracts with Uzbeks as part of this supply chain are potentially as lucrative for persons close to the Uzbek government as direct US aid would be. Despite the US State Department's re-designation in January 2009 of Uzbekistan as a "Country of Particular Concern" for systematic violations of religious freedom, the US government retained a waiver on the sanctions outlined in the designation. The DOD's prominence in the relationship with the Uzbek government raises concerns over mixed messages about human rights issues among different US agencies.