Sudan's human rights environment deteriorated in 2010 during the April elections and in the months leading up to the historic referendum on southern self-determination, scheduled for early January 2011. The referendum was called for as part of the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA), which ended Sudan's 22-year civil war.

The April multi-party national elections, also prescribed by the CPA, were marked by serious human rights violations and resulted in the consolidation of power for both the national ruling National Congress Party (NCP) and the Sudan People's Liberation Movement (SPLM), which controls Southern Sudan. Omar al-Bashir - subject of an arrest warrant from the International Criminal Court for crimes committed in Darfur - was re-elected president of the national government, and Salva Kiir as president of Southern Sudan and vice president of the national government.

In the second half of the year domestic and international attention shifted to the referendum, in which southerners will vote to either remain part of a united Sudan or secede. Should southerners secede, a parallel referendum in Abyei, the disputed oil-rich area straddling the north-south divide, will determine whether that area remains part of Sudan or joins Southern Sudan.

The parties made slow progress in resolving key issues around the referendum such as voter eligibility in the Abyei referendum, and post-referendum arrangements concerning citizenship rights, oil- and wealth-sharing, and debt allocations.

Darfur, in western Sudan, saw continued large-scale attacks by government forces on rebel forces and civilians, as well as an increase in armed clashes between ethnic groups, particularly in South and West Darfur. The United Nations and humanitarian agencies increasingly came under attack and were targeted for robberies, kidnappings, and killings by armed elements in Sudan's western region.

In January the parliament amended the Child Act, setting 18 years as the legal age of majority. The previous year Sudan executed Abdulrahman Zakaria Mohammed in El Fasher, North Darfur, for a crime he committed at the age of 17. It remains unclear whether the amendments to the child act will lead to a ban on the juvenile death penalty in accordance with international law.

Rights Abuses in National Elections

Human Rights Watch documented numerous rights violations across Sudan by both northern and southern authorities in connection with the April elections. International and domestic election observers reported widespread technical irregularities such as multiple voting, ballot-stuffing, and other acts of fraud.

In the months leading up to the elections in the north, the ruling NCP arrested opposition party observers and civil society groups, suppressed peaceful assemblies by opposition party members in the north, and restricted free association and speech. During the week of the election, there were fewer cases of such restrictions, but Human Rights Watch documented several cases of harassment, intimidation, and arrests of opposition members and election observers in the north.

In Darfur, continued insecurity presented an obstacle to holding free and fair elections. Large areas of Darfur were inaccessible to election officials and candidates; insecurity due to banditry and ongoing conflict restricted candidates' freedom of movement.

In Southern Sudan, throughout the elections process, security forces engaged in widespread intimidation, arbitrary arrest, detention, and mistreatment of opponents of the SPLM as well as of election observers and voters.

In the weeks following the elections the human rights situation across Sudan deteriorated, with renewed political repression in the north, incidents of election-related violence in the south, particularly where SPLM candidates ran against independent candidates, and ongoing conflict in Darfur. The lack of accountability for abuses during the elections did not bode well for a free and fair referendum process nine months later.

Political Repression in Northern Sudan

The national government failed to enact institutional and legal reforms, which are required by the CPA. The national legal framework continues to allow censorship of the press and restrictions on freedom of assembly and political expression. The new National Security Act, passed in January, retains broad powers of arrest and detention for up to four-and-a-half months, in violation of international treaties to which Sudan is a party. Legal immunities for security forces remain in place.

The post-election crackdown in Khartoum, Sudan's capital in the north, included the May 15 arrest and six week detention of the opposition figure Hassan al-Turabi and the arrest of four journalists from Rai al Shaab, the newspaper affiliated with al-Turabi's Popular Congress Party (PCP). One of the journalists was subjected to electric shocks while in the custody of national security agents. In July three of the journalists received prison sentences on charges of "attempting to destabilize the constitutional system."

In addition, authorities resumed pre-print censorship, a practice that al-Bashir publicly declared had ended in September 2009. Officials banned articles that reported on the arrests of al-Turabi and the journalists, and the escalating violence in Darfur. In the weeks that followed authorities continued to censor papers through site visits and telephone calls to editors-what Sudanese journalists call "remote control censorship"-and shut down several newspapers.

National security forces continued to harass human rights activists and target student members of the United Popular Front (UPF), a student group that the government alleges has links to the Darfuri rebel group led by Abdel Wahid al-Nur. Members of the group were subjected to arrest, detention, ill-treatment, and torture.

Insecurity and Human Rights Violations in Southern Sudan

Vote-rigging and intimidation during the elections in the south led to anger and frustration. Grievances over the election results led to armed clashes, particularly in areas where the SPLM faced strong opposition.

In northern Jonglei state, for example, forces loyal to a former deputy chief of staff of the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA) who unsuccessfully ran for state governor as an independent candidate, clashed with the SPLA on multiple occasions after the results were announced. The SPLA's efforts to capture the renegade commander resulted in numerous human rights abuses against the civilian population in northern Jonglei including sexual violence. In Upper Nile state, SPLA soldiers clashed with local militia whom they accused of links to the SPLM-DC, a breakaway political party led by former SPLM leader Lam Akol. The soldiers were responsible for killings and rapes of civilians during these operations.

Patterns of intercommunal violence stemming from cattle-rustling and other localized disputes across Southern Sudan continued to put civilians at risk of physical violence and killings. The Lord's Resistance Army also continued to pose a significant security threat in western parts of the region, with attacks, abductions, and killings reported on a monthly basis.

Neither the Government of Southern Sudan nor the UN Mission in Sudan has adequately been able to protect civilians from these sources of violence. Weaknesses in the justice sector and lack of accountability mechanisms fostered an environment of impunity for violence and human rights violations.

Civil and Political Rights and the Referendum

In the weeks preceding the referendum, Southern Sudanese communities living in Khartoum and other northern states reported heightened anxiety over the status of their citizenship rights following the referendum. NCP officials publicly threatened that southerners may not be able to stay in the north in the event of a secession vote. A higher-than usual number of southerners returned to Southern Sudan toward the end of 2010, with tens of thousands arriving in southern states during voter registration in November. Although SPLM and Government of Southern Sudan officials stated that they would protect the rights of northerners living in the South, some northern traders reported facing intimidation and moved to northern states. As of mid-November, however, the two ruling parties had not formally agreed to post-referendum citizenship arrangements. Both southerners in the north and northerners living in Southern Sudan said that they feared retaliation, even expulsion, if secession were approved.

Journalists and civil society activists across the country reported that they were not free to speak openly about any opposition to the prevailing sentiment regarding the outcome of the referendum. In October security forces arrested a group of southern students speaking out in support of secession at a pro-unity rally in Khartoum, underscoring growing tensions. Although the head of the national security service in early August lifted pre-print censorship in northern states, repressive policies toward the media have caused many Khartoum-based papers to self-censor on sensitive topics, including the referendum outcome.

Deterioration in Darfur

Fighting in Darfur intensified in 2010, with armed clashes between government and rebel forces, among rebel factions, and between armed ethnic Arab groups in South and West Darfur. In Jebel Mara, a stronghold of the Sudan Liberation Army (SLA) faction led by Abdel Wahid al-Nur, fighting among SLA groups over support for the Doha, Qatar peace talks and clashes between government forces and rebels continued throughout the year. Government attacks on Jebel Mara intensified again in September, destroying dozens of villages and causing mass displacements. In Jebel Mun, another rebel stronghold, and elsewhere, clashes between government forces and the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) intensified early in the year, following the January rapprochement between Chad and Sudan, in which both governments agreed to end support to rebel groups fighting in each other's territory and to jointly patrol their common border.

The UN-African Union Mission in Darfur (UNAMID) was unable to access most of the areas affected by violence, despite its mandate to protect civilians under imminent threat of physical violence. Both government and rebel authorities blocked the peacekeepers and humanitarian agencies at various times. An increase in banditry, abductions, and attacks on UN and humanitarian aid operations undermined the international response.

Meanwhile the peace process at Doha foundered. JEM and the SLA faction led by Abdel Wahid al-Nur and other groups boycotted the process, leaving only one rebel group, the Liberation and Justice Movement (LJM), to negotiate.

In September the Sudanese government released a new strategy on Darfur that focused on the return of displaced persons to their home villages. The plan did not provide clear safeguards for the rights of displaced persons, such as their voluntary return. The government repeated its intention to dismantle the camps, particularly the volatile South Darfur Kalma camp, where political violence between armed groups killed 10 people in August.

Between October 30 and November 3, Sudanese national security officials arrested and detained more than 10 Darfuri activists and journalists in Khartoum, and continue to hold them in unknown locations without access to family or lawyers. The arrests were widely viewed as a means to suppress information and advocacy on Darfur.

Key International Actors

International engagement on Sudan increased and intensified with the elections and referendum, particularly by key CPA stakeholder countries like the United States. The UN continues to deploy two major peacekeeping missions in the country: the UN Mission in Sudan (UNMIS) and UNAMID.

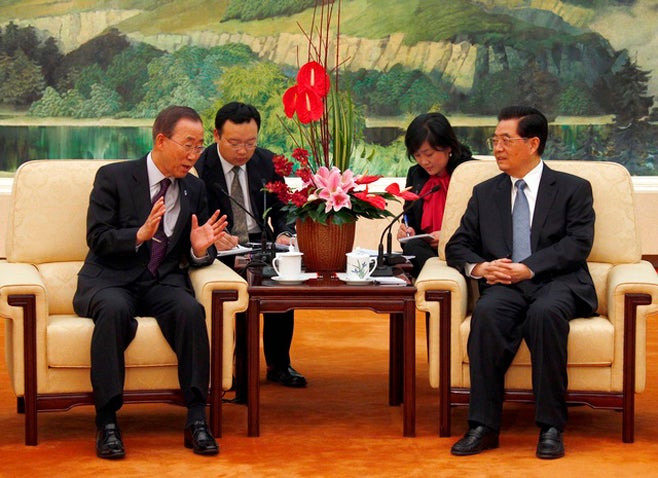

On September 24 the UN convened a high-level meeting on Sudan in which the Sudanese parties to the CPA and 40 heads of state re-affirmed their commitment to a timely, peaceful referendum in January 2011.

With the focus on the referendum, international attention shifted away from Darfur, despite the deteriorating situation there and lack of progress on a peace deal. The Sudanese government made little progress in implementing recommendations of the AU High Level Panel on Darfur; the AU and other influential leaders did not press the government to do so. In general, the key stakeholder countries engaged on Sudan continued to be divided in approach and willingness to use pressure to influence the Sudanese government.

In Geneva, in September, the UN Human Rights Council renewed the mandate of the Independent Expert on Sudan, maintaining a much-needed avenue for human rights reporting, over objections from Sudan and its allies. The two major peacekeeping missions in Sudan, UNMIS and UNAMID, did not publicly report on their human rights concerns except through regular reports to the UN secretary-general.

The ICC continued its investigation of crimes committed in Darfur and issued a second arrest warrant for President al-Bashir in July 2010, adding genocide to charges on war crimes and crimes against humanity. The same month, the AU reiterated a July 2009 call for its member states not to cooperate in the arrest of al-Bashir. In a setback for accountability Kenya and Chad - both states parties to the ICC - allowed al-Bashir to enter their territories in July and August, citing the AU decision.