Kuwait's human rights record drew increased international scrutiny in 2010, as proposed reforms for stateless persons, women's rights, and domestic workers remains stalled. Freedom of expression deteriorated as the government continued criminal prosecutions for libel and slander, and charged at least one individual with state security crimes for expressing nonviolent political opinions.

Discrimination against women continues in nationality, residency, and family laws, and in their economic rights, though women gained the right to vote and run for office in 2005.

Kuwait continues to exclude the stateless Bidun people from full citizenship, despite their longstanding roots in Kuwaiti territory. The Bidun also face discrimination accessing education, health care, and employment, as well as violations of their right to marry and establish a family because they are not allowed to register births, marriages, or deaths.

Kuwait significantly advanced workers' rights in 2010 through a new private sector labor law. Minister of Labor Mohammad al-‘Afasi announced in September 2010 the government would abolish the sponsorship system in February 2011 and supervise migrant labor recruitment through a government authority. However the new law continued to exclude domestic workers, who make up approximately one-third of the private sector workforce and face recurring abuses. Labor ministry officials informed Human Rights Watch that plans for sponsorship reform also exclude domestic workers.

In May 2010, at the United Nations Human Rights Council in Geneva, Kuwait promised to sign the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and to establish an independent human rights institution based on the Paris Principles. At this writing the government has not made definite progress towards either measure.

Women's and Girls' Rights

Kuwait's nationality law denies Kuwaiti women married to non-Kuwaiti men the right to pass their nationality on to their children and spouses, a right enjoyed by Kuwaiti men married to foreign spouses. The law also discriminates against women in residency rights, allowing the spouses of Kuwaiti men but not of Kuwaiti women to be in Kuwait without employment and to qualify for citizenship after 10 years of marriage.

In 2005 Kuwaiti women won the right to vote and to run in elections, and in May 2009 voters elected four women to parliament. In April 2010 an administrative court rejected a female Kuwaiti law graduate's application to become a public prosecutor based on her gender. The advertisement for the position was open to male candidates only. The presiding judge found that article two of Kuwait's constitution, which cites Islam as the state religion and Islamic Sharia as "a main source of legislation," prevented women from holding prosecutorial positions. Kuwaiti women are also denied the right to become judges.

No government data exists on the prevalence of violence against women in Kuwait, although local media regularly report incidents of violence.

Bidun

Kuwait hosts up to 120,000 stateless persons, known as the Bidun. The state classifies these long-term residents as "illegal residents," maintaining that most do not hold legitimate claims to Kuwaiti nationality and hide "true" nationalities from Iraq, Saudi Arabia, or Iran.

Due to their statelessness, the Bidun cannot freely leave and return to Kuwait; the government issues them temporary passports at its discretion, mostly valid for only one journey. Furthermore the Bidun face restrictions in their access to public and private sector employment, as well as to healthcare. Bidun children may not enroll in free government schools. The Bidun also cannot register births, marriages, or deaths, obstructing their rights to family life.

Lawmakers in December 2009 failed to reach the quorum required to discuss a 2007 draft law that would grant the Bidun civil rights and permanent residency, but not nationality. In January 2010 the assembly tasked the Supreme Council for Higher Planning with reporting on the Bidun situation. Bidun from Kuwait continued to seek and receive asylum abroad in countries including the United Kingdom and New Zealand, based upon their treatment by Kuwaiti government authorities.

Freedom of Expression and Media

Freedom of expression markedly deteriorated in 2010. The government continued criminally prosecuting individuals based on nonviolent political speech, denied academics permission to enter the country for conferences and speeches, and cracked down on public gatherings. In April state security forces summarily deported over 30 Egyptian legal residents of Kuwait after some of them gathered to support Egyptian reform advocate Mohammed El Baradei.

In May prominent writer and lawyer Mohammad al-Jassim was detained for over 40 days and charged with "instigating to overthrow the regime, ...slight to the personage of the emir [the ruler of Kuwait],... [and] instigating to dismantle the foundations of Kuwaiti society" over his blog posts criticizing the prime minister. A judge released al-Jassim in June and adjourned the case until October.

Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

Kuwait continues to criminalize consensual homosexual conduct, in contravention of international best practices. Article 193 of Kuwait's penal code punishes consensual sexual intercourse between men over the age of 21, with up to seven years imprisonment (10 years, if under 21 years old). Article 198 of the penal code criminalized "imitating the appearance of a member of the opposite sex," imposing arbitrary restrictions upon individuals' rights to privacy and free expression. The police continued to arrest and detain transgendered women on the basis of the law, many of whom have previously reported abuse while in detention.

Migrant Worker Rights

More than two million foreign nationals reside in Kuwait, constituting an estimated 80 percent of the country's workforce. Many experience exploitative labor conditions, including private employers who illegally confiscate their passports or do not pay their wages. Migrant workers often pay exorbitant recruitment fees to labor agents in their home countries and must then work off their debt in Kuwait.

For the first time since 1954 the government passed a new private sector labor law in February, which provides workers with more protections on wages, working hours, and safety. However, it does not establish monitoring mechanisms and continues to exclude the country's 660,000 domestic workers who come chiefly from Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and the Philippines and work and live inside employers' homes in Kuwait. No law provides them with a weekly rest day, limits their working hours, or sets a minimum wage. Many domestic workers complain of confinement in the house; long work hours without rest; months or years of unpaid wages; and verbal, physical, and sexual abuse.

A major barrier to redressing labor abuses is the kafala (sponsorship) system, which ties a migrant worker's legal residence in Kuwait to his or her employer, who serves as a "sponsor." Migrant workers who have worked for their sponsor less than three years can only transfer with their sponsor's consent (migrant domestic workers always require consent). If a worker leaves their sponsoring employer, including when fleeing abuse, the employer can register the worker as "absconding", a criminal offense that most often leads to detention and deportation. In September the government announced plans to abolish the sponsorship system in February 2011, but provided no details about the system that would replace it, or whether it would include migrant domestic workers.

Key International Actors

The United States, in the 2010 State Department Trafficking in Persons report, classified Kuwait as Tier 3-among the most problematic countries-for the fourth year in a row. However, the US chose not to impose sanctions for Kuwait's failure to combat human trafficking. President Barack Obama determined that sanctions would affect US$2.4 billion in projected foreign military sales to Kuwait and would restrict a US$4 million grant to the Middle East Partnership Initiative, considered a key tool for promoting democracy and respect for human rights in the country.

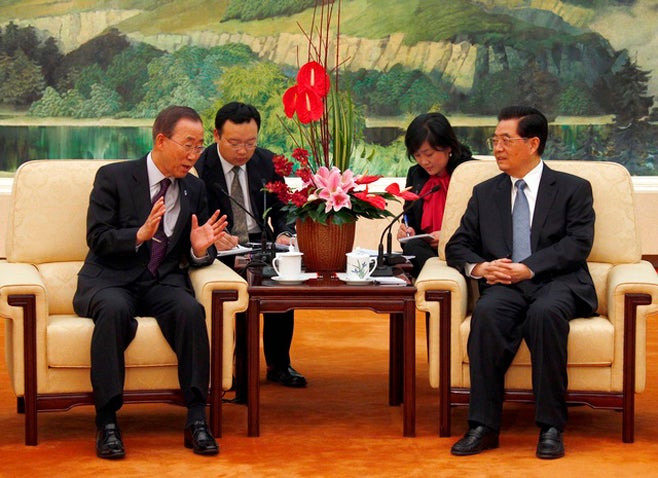

In April 2010 UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Navanethem Pillay visited Kuwait and spotlighted the sponsorship system and statelessness as pressing human rights concerns.