Drive People to Risk Everything to Reach the US

Drive People to Risk Everything to Reach the US

Four tortillas, five cans of beans, jalapeños, and sausage, and a gallon of water—that is what smugglers provided Rafael for his week-long journey across the desert from Mexico to Texas in 2021. After eight days of thirst, hunger, and heat, he made it, only to be caught by United States immigration agents and sent back.

He had little choice but to try again. Repeated droughts in Guatemala, followed by heavy rains from tropical cyclones, had decimated his crops, depriving his family of their main food source and leaving them hungry for days and weeks on end. So Rafael, who like other migrants described here is identified by a pseudonym for his protection, had taken on thousands of dollars in debt, at 8 percent monthly interest, to hire smugglers for his trip north. This was impossible to repay from Guatemala, where he earned at most 35 quetzals (about US$4.60) per day.

Drought and tropical cyclones have compounded widespread food insecurity and poverty in Guatemala in recent years. In March and April 2022, Human Rights Watch traveled to 10 rural, mostly Indigenous communities affected by either recent droughts or the back-to-back November 2020 tropical cyclones Eta and Iota, or both. We found that the government had done little to protect populations from these devastating events, which have led many to take on crushing debt, and risk their lives, to reach the United States.

Human-induced global warming has made certain extreme weather events more frequent and/or intense, though it can be difficult to determine to what extent specific events are linked to human-induced climate change. There is no reason to doubt, however, that global warming is likely to make droughts and cyclones even worse in Central America in the coming decades.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) projects increases in the frequency and severity of droughts as well as tropical cyclone intensity in Central America under the mid-to-high carbon dioxide emission conditions that the world faces in the near future. It also projects global intensification of tropical cyclone rainfall.

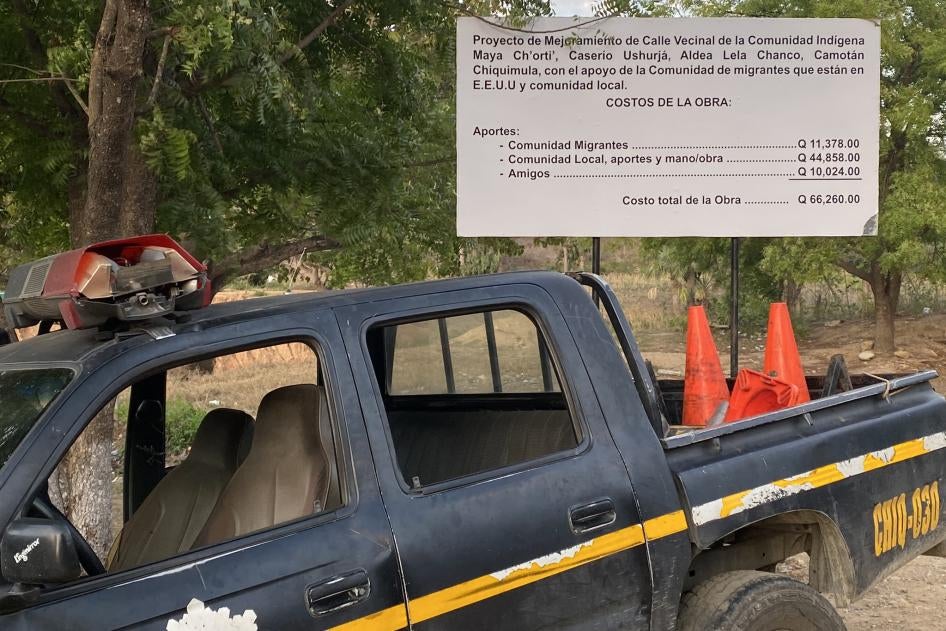

Rafael’s family relies on scarce rain for the beans and corn they plant, for their own consumption, on rented, rocky, unfertile land in the Dry Corridor of Guatemala. This precarious livelihood is common for members of the Ch’orti’ Mayan Indigenous group, who since colonization have lost significant swaths of their land through processes plagued by abuse. With droughts and then storms ruining their crops, Rafael, his wife, and young children would often eat just once a day—one or two tortillas, with some beans. His children would cry from hunger.

So, carrying a heavy backpack, the growing loan debt, and the knowledge of his hungry family at home, 24-year-old Rafael made his second attempt to cross the desert into the United States. This time he made it in five days. But one of the seven migrants in his group was not so lucky: he passed out and, too heavy to carry, was left in the desert.

Hundreds of thousands of Guatemalans have attempted to migrate to the United States over the past several years, for reasons such as poverty, unemployment, violence, droughts and tropical cyclones. The vast majority do so like Rafael—in the shadows and unsafely—because they lack options to migrate legally, and heavy border enforcement pushes them into hazardous desert terrain.

Without new measures by Guatemala to protect populations from these conditions, and changes to US immigration policy, countless more long-marginalized Guatemalans will remain mired in poverty and hunger at home, or risk it all on journeys to the United States.

Tropical Cyclone Destruction

Like Rafael, Luis migrated to the United States in 2021 to help his family, but it was a tropical cyclone that put him in desperate need. He had been working in Guatemala City on November 5, 2020, when his brother called to inform him that in their village, Quejá, the hillside had crashed down on their family’s home. They tried to outrun the falling earth, but not everyone made it. Among the dead were his 9-year-old brother, nephews ages 2 years and 9 months, and several cousins. His parents found two surviving sisters partly buried—one with just her head above ground. She has been unable to walk since.

Heavy rains associated with tropical cyclone Eta triggered the massive landslide, which killed 58 townspeople in the predominantly Poqomchi’ Mayan community of Quejá in Alta Verapaz state, where more than 300 families lived. Just 10 days later, as Quejá survivors took refuge in nearby schools and other makeshift shelters, a second tropical cyclone, Iota, carved another path of destruction through Central America.

Remains of structures destroyed by a November 2020 landslide in Quejá, Alta Verapaz state, Guatemala, with a stripped mountain, from which the land fell, in the background, April 2022.

© 2022 Max Schoening for Human Rights WatchTwenty-five miles southwest of Quejá, the combined rains of Eta and Iota filled the valley in which the Q’eqchi’ Mayan village of Sesab sits, forming a lagoon dozens of meters deep that completely submerged much of the community’s lands and buildings. When the water drained after three months, residents returned to a damaged school, destroyed health post, ruined crops, and about a dozen homes needing repair or complete rebuilding. The flood had caused lasting damage to their farmlands’ productivity.

In the same state, residents of the Q’eqchi’ Mayan village of El Esfuerzo Chicojuc told Human Rights Watch that their crop production also had dramatically declined since Eta and Iota, when a river flood dumped two feet of sand on their farmland. Members of both communities said they had to cut down on their meals for months.

Quejá, Sesab, and El Esfuerzo Chicojuc are dramatic examples of more widespread destruction that Eta and Iota wrought in Guatemala. Between November 3 and 17, 2020, extreme rains caused landslides, mudslides, and river floods throughout the country, with massive damage to housing, agriculture, and infrastructure. Eta and Iota were just the latest of repeated tropical cyclones that have affected Guatemala over the past three decades, killing thousands, affecting millions, and inflicting billions of dollars in damage.

“We were left with nothing,” said Luis. “We didn’t even have clothes left, because everything was under the earth.” After spending several months in shelters, Luis’s family and others from Quejá started to relocate to a nearby area now called “New Quejá,” where many, including his family, had some land.

Luis’s family built a home there without government support, as did José, who in addition to losing his house and land in the landslide, lost his uncles and aunt, nephews, and cousins. Their new houses were smaller, overcrowded, and more vulnerable to wind and rain—wooden and sheet-metal downgrades from their concrete block houses in Quejá.

(Left): José’s son, Alvaro, sitting in the room where he and eight other family members sleep, in the home family built with its own resources in New Quejá, Alta Verapaz, following the landslide. (Right): José’s family member cooks lunch in kitchen that the family built, with its own resources, in New Quejá, Alta Verapaz, following the landslide, April 2022.

© 2022 Max Schoening for Human Rights WatchDesperate to pay for new homes and the other costs of rebuilding their families’ lives, Luis and José decided to migrate to the United States in early 2021, 2 of the roughly 30 Quejá residents who a community leader said in mid-2022 had attempted the journey since the landslide. Luis and José each took out more than 100,000 quetzals (US$13,000) in loans to pay smugglers, and both had treacherous trips. Scores of other survivors without the means to migrate or even to relocate to New Quejá have returned to Quejá, where the uncleared rubble, entombing their relatives’ remains, portends further disaster.

The United States is out of reach for many Sesab residents. They said that since Eta and Iota, many village men have gone to Guatemala City, working in private security or construction to support their families as they faced crop losses and rebuilt. Isabela, a 45-year-old mother in Sesab, said that even with her husband sending her nearly half of his weekly private security wages of 450 quetzals (US$60), she and her children typically ate just twice a day—one and a half to three tortillas per meal for each.

Meanwhile, in El Esfuerzo Chicojuc, residents said children were not eating enough and were getting sick. One man there, Hermelindo, said he had not received any government assistance since the flooding, and that with his family’s land and home damaged from the sand, they started living full time in the nearby town center, where the most he could make was 35 to 40 quetzals ($US 4.60-5.20) per day a few days a week, as a day laborer. Facing those bleak prospects, his 19-year-old son went to Mexico for seasonal farm work. Of the 18 families living in the community before the storms, just two remained as of May 2022.

(Left): Hermelindo, his wife Claudia, and two of their children in their home in El Esfuerzo, Chicojuc, Alta Verapaz, Guatemala, which was damaged by the flooding, including by a thick layer of sand on the home’s floor, March 2022. (Right): Hermelindo and his wife Claudia in El Esfuerzo, Chicojuc, Alta Verapaz, Guatemala, standing next to their crops, whose growth has been severely impeded by the sand that flooding dumped there, March 2022.

© 2022 Max Schoening for Human Rights WatchDroughts and Hunger

A more frequent and chronic problem than cyclones is the sparse and erratic rain in the Dry Corridor, a region spanning Central America, where recent droughts have undermined access to food for millions of residents. Human Rights Watch visited six communities in three of Guatemala’s Dry Corridor states—Chiquimula, Zacapa, and Baja Verapaz—to investigate the links between drought, food insecurity, and migration.

Like many Dry Corridor communities, the six we visited are largely made up of subsistence farmers, whose corn and bean crops supply a substantial portion of their families’ food. For the rest, they work low wage and sporadically available seasonal jobs, commonly as day laborers on coffee or sugar plantations, where they said they earn about 35 to 75 quetzals (US$4.60-10.00) daily, sometimes less.

The family agriculture is rain-fed—irrigation is rare. The rainy season, from about May to October, is the only opportunity to produce its one or two annual harvests. The success of these harvests—and thus a big chunk of the family’s food supply—depends on whether the rainy season brings enough sustained rain.

In recent years, rainy seasons in Central America’s Dry Corridor have been light and erratic, leading to major crop losses for subsistence farmers. Studies indicate that during drought years, Guatemalan farmers lose an average of 55 percent of their corn and bean crops, and in some years much more. In 2018, for example, the humanitarian organization Oxfam surveyed Guatemala’s Dry Corridor communities that had experienced prolonged gaps in rain during the growing season that year. Oxfam found that farmers had lost an average of three-quarters of their crops and estimated that hundreds of thousands of people in the region needed food assistance because they were experiencing moderate to extreme “food insecurity,” a technical term for lack of regular access to food.

Drought-exacerbated food insecurity often translated to fewer meals per day, and fewer tortillas per meal, for residents in the six communities we visited. Emilio, 27, from a Ch’orti’ Mayan community in the state of Chiquimula, said that as rain had grown sparser over the past decade, his family’s corn and bean production was cut by more than half. His family went from eating as many tortillas as they wanted, three times per day, to his mother rationing one and a half to two tortillas per person, twice a day, sometimes with a small portion of beans or leafy green soup. He remembers her telling him and his siblings at night, after skipping dinner, “Let’s go to bed, because asleep we won’t be hungry.”

Oscar’s three young children also often went to sleep hungry in their predominantly Achi’ Mayan community in Baja Verapaz. Oscar said scarce rains had limited the annual harvest from his family’s small plot of rented land to no more than 100 pounds of corn—and no beans—a tiny amount for a household of 10. One tortilla, with salt, once or twice per day, was often all Oscar and his wife said they could give their young children to eat, even though—like Rafael’s children, and Emilio’s younger siblings—they cried for more.

Forty-seven percent of Guatemalan children under age 5 suffer from chronic malnutrition, which can have lifelong consequences for physical and cognitive abilities, as well as health.

Neither Emilio nor Oscar could earn enough as laborers to make up for the lost crops. They reported making about 35 quetzals (US$4.60) per 100 pounds of beans picked—often unachievable in a day—during the harvest season on coffee plantations, which have been hit hard over the past decade by a fungus called coffee leaf rust. Oscar, 28, said that sometimes, when coffee harvests were small, he could pick only 35 pounds a day, earning less than $2. Emilio tried working 24-hour shifts, every other day, at a gas station, but only made 1,000 quetzals (US$130) a month, about 36 cents per hour. All these wages were far below the legal minimum.

Making matters worse, Dry Corridor farmers also face periods of too much rain. In 2020, Eta and Iota’s rains wiped out crops for thousands of families in the region.

Things came to a breaking point in 2021: after planting corn crops in April, Emilio watched them wither away under abnormally dry May skies. He and his mother decided it was time for him to try to make it to the United States. Oscar made the same decision in early 2021.

To pay smugglers the first portion of their fees, to make it across the US-Mexico border, but not even to the final US destination, Emilio and Oscar took out several thousands of dollars of loans each, with 7 and 10 percent monthly interest, from local moneylenders, handing over as collateral the family’s and a family friend’s land, respectively.

Beyond potentially losing land and taking on insurmountable debt, they were risking their lives: Emilio knew that a cousin of his had barely survived the desert crossing into the United States. And after four days of walking under the hot desert sun, Oscar would find himself alone, without food or water, lying on his back, and unable to continue.

The Role of Climate Change

Guatemalans bear little responsibility for climate change: the country has produced 0.03 percent of global cumulative carbon dioxide emissions since 1750, and is responsible for 0.05 percent of current emissions, as compared to the United States’ share of 24.3 and 13.5 percent, respectively. While scientists are continuing to collect evidence on the association between past extreme weather events in Central America and human-induced climate change, we already know that the impact of such events on Guatemalans and others living in poverty is devastating. As climate change impacts continue to threaten Guatemalans living in poverty in coming years and decades, urgent action by policymakers to adapt and respond to related migration is needed.

Global Increase in Extreme Weather Events

Scientists are actively studying the extent to which human-caused climate change has been associated with various types of extreme weather events globally, including droughts and tropical cyclones. There is mounting evidence of the increasing likelihood and strength of such events in all regions of the world as a consequence of higher water and air temperatures, weaker ocean currents, and expanding aridity due to climate change.

In particular, the IPCC Working Group I (WGI), the world’s leading authority on evaluating the physical science of climate changes and their causes, reported in August 2021 with medium-to-high confidence that, across the globe, “human-induced climate change increases heavy precipitation associated with tropical cyclones.” It also noted that “[i]t is likely that the global proportion of Category 3–5 tropical cyclone instances and the frequency of rapid intensification events have increased globally over the past 40 years,” and that in the future “average peak [tropical cyclone] wind speeds and the proportion of Category 4–5 [tropical cyclones] will very likely increase globally with warming.”

WGI has pointed out that it can be difficult to assess drought trends and their causes, also noting that there are many different types of droughts. However, it concluded that “[p]ast increases in agricultural and ecological droughts are found on all continents” and that there is evidence that human influence has contributed to these increases in some regions.

Past Extreme Weather Events in Central America

While WGI has described these broad trends globally, it is often more challenging to determine to what extent extreme weather events in a specific country or region of the world are linked to human-induced climate change. In Guatemala and Central America this task is especially difficult for many reasons, including limited observational data, stemming in part from sparse weather station networks; lack of published climate-change research focusing on the region; complex factors behind droughts and tropical cyclones and, more generally, the climate of Central America—a relatively narrow slice of land sandwiched by the Pacific’s and Atlantic’s converging influences.

Scientists continue to evaluate new evidence on the links between various climate events and human-induced climate change. The latest report by the IPCC’s WGI found links between climate change and past droughts in Central America, but in part due to limited data at the time, it was unable to draw conclusions of medium to high confidence about the links. Specifically, in 2021 it reported “low confidence” that human activities such as greenhouse gas emissions have affected drought trends in the region, citing “limited evidence”—meaning “a lack of available data in the region and/or lack of relevant studies.” (The scientists explained in the report that “low confidence” findings do “not necessarily mean that confidence in its opposite is high”; nor “does [it] imply distrust in the finding; instead it means that the statement is the best conclusion based on currently available knowledge.”)

Since then, scientists whose previous work the IPCC has cited published a study finding that human-induced climate change made a 2015-19 period of drought in Central America four times more likely to occur. During that period, the five-year average rain for the May-September months of the rainy season was Central America’s lowest in the last 100 years. The study also reported that a longer, 40-year drying trend in Central America, dating back to 1979, was consistent with natural variability, rather than human-induced climate change.

Men peer out over the remains of a portion of the road that had connected the town of Timushan to La Unión, Zacapa state, Guatemala. The road was destroyed during Eta and Iota in November 2020, and has not yet been rebuilt, March 2022.

Similarly, a May 2021 study that analyzes the probability of droughts globally in the 1956-2005 period, which was not published in time to be considered in the WGI report, found that “greenhouse gases have significantly influenced drought occurrences” in Central America as well as several other regions.

In February 2022, the IPCC’s Working Group II (WGII), which focuses on the impacts of climate change, released a report assessing how climate change has affected societies and nature, globally and regionally. For Central America, it reported with high confidence that climate change has “highly impacted” annual crop systems. It noted that crop losses “largely result” from erratic rainfall and seasonal droughts. The WGII did not make any findings on whether these reported changes are linked to human influences such as greenhouse gas emissions—those assessments fall within the expertise of the WGI.

The WGI has not been able to reach confident conclusions about the connection of past tropical cyclones in Central America to human-caused climate change. No published studies have focused on the specific question of whether global warming influenced tropical cyclones Eta and Iota’s impact in Guatemala in 2020.

Nonetheless, other scientific studies provide a basis to infer that human-induced global warming may have contributed to the heavy rainfall that accompanied Eta and Iota in Guatemala. The key physical principle explaining why warming intensifies tropical cyclone rainfall is that warmer air holds more water vapor. That means there is more water available to fall as rain. An April 2022 study concluded that human-induced climate change increased the extreme rainfall for tropical storms and hurricanes during the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season (of which Eta and Iota were a part.)

Likelihood of Future Extreme Weather Events in Central America

As the government of Guatemala, other governments in the region, and US policymakers consider policies on adaptation to climate change and migration, their focus should be on the likelihood of future extreme weather events and other climate change affecting people in Central America.

In the future, without significant action to curb emissions, Central America is one of the global regions where global warming is expected to increase drought severity and frequency, and amplify tropical cyclones’ intensity while decreasing their frequency. This is the IPCC WGI’s scientific projection with medium confidence under mid-to-high carbon dioxide emissions scenarios. The WGII projects worsening crop losses and increased risks of food insecurity in the region. Finally, the WGI projects that globally, tropical cyclone rainfall will continue to increase with further global warming—a concerning finding given Guatemala’s vulnerability to flooding and landslides, as demonstrated by Eta and Iota.

Together, the different lines of evidence paint a picture of increased frequency and/or intensity of extreme weather events in Central America in the future, thus necessitating bold policy action to facilitate and allow for human adaptation, including migration.

The Guatemalan Government’s Protection Failures

While Guatemala bears a minuscule portion of the blame for the climate crisis, its government is far from blameless for the plight of Guatemalans affected by droughts and tropical cyclones. The harm these events inflict is not simply a product of weather and climate. It is a consequence of how the weather and climate interact with populations’ historically produced vulnerabilities and the extent to which government policies reduce them. In Guatemala, the vulnerabilities are linked both to colonial exploitation and US support for a military regime that committed genocide and crimes against humanity against Indigenous populations. A big reason drought- and tropical cyclone-affected families have suffered is that the Guatemalan government has fallen short in fulfilling its obligations, under international human rights law, to ensure an adequate standard of living (and thus reduce the vulnerabilities) and to protect against foreseeable environmental harm.

(Left): Mayra stands outside her home, which had been damaged by Eta- and Iota-induced flooding, in Sesab, Alta Verapaz state, April 2022. She said the community has received no government help in rebuilding after the floods. (Right): Mayra points to a white-roofed school in the valley below, which was fully submerged in water for three months due to flooding from Eta and Iota, April 2022. She said the flooding reached more than halfway up the walls of her home, to her right. Since the floods, her husband has spent a significant portion of his time working in Guatemala City to send money back to support the family and repair the flooding damage to the home.

© 2022 Max Schoening for Human Rights WatchErratic and reduced rains would not be so devastating if residents were not eking out a subsistence, rain-fed farmer’s livelihood on small plots of unfertile land. Cyclone damage would not be so catastrophic if residents weren’t battling poverty and discrimination, with dismal employment options, and limited access to education, food, health care, and safe drinking water, among other basic rights.

The Guatemalan government recognizes that the country’s socioeconomic conditions are “in large part” why it is especially vulnerable to climate change. Despite being an upper-middle income country, as measured by Gross Domestic Product per capita, Guatemala has the fourth highest rate of chronic child malnutrition in the world, more than half of the country is estimated to live in poverty, and it ranks in the bottom third of the UN’s Human Development Index (HDI) based on life expectancy, education, and standard of living metrics.

A farmer stands outside of his home in a village in Chiquimula state, Guatemala, March 28, 2022. He said that droughts have caused crop losses, reducing access to food and income in his community, and leading people to migrate. The government “has abandoned us,” he said, referring to the lack of food assistance programs, or water systems, in his community.

Guatemala’s low human development rating is, as one government report puts it, “rooted in the concentration of wealth in small sectors and the majority of the population being excluded from the exercise of their rights.” Unequal land distribution, for example, is a “principal factor” behind food insecurity, according to the government’s first national climate change plan. Wealth and income inequality, in turn, trace ethnic lines: in 2021, the government reported that 80 percent of Guatemala’s large Indigenous population suffers from multidimensional poverty, as compared with 50 percent of non-Indigenous people.

Low tax collection contributes to the lack of adequate public services and poverty, according to the World Bank, which has reported that Guatemala’s small government revenues “limit capacity for public investment,” and restrict basic services, “largely explaining [Guatemala’s] lack of developmental progress and large social gaps, trailing behind the rest of Latin America and the Caribbean.” Corruption eats away these limited government funds, and has been facilitated by Attorney General Maria Consuelo Porras, who has arbitrarily fired and pressed bogus criminal charges against anti-corruption prosecutors, and was barred from entering the United States in 2022 “due to her involvement in significant corruption.”

Meanwhile, between March and May 2022, 3.9 million Guatemalans—22 percent of the population— suffered “crisis”-to-“emergency” levels of acute food insecurity, amid rising food and fuel prices.

The history of Ch’orti’ Mayan Indigenous communities—home to Rafael and Emilio—illustrates the deeply rooted nature of vulnerability to extreme weather events in Guatemala. The Ch’orti’ live in an eastern region of the Dry Corridor with mountains and valleys. The valleys have fertile land; by comparison, the mountainside soil is rocky, shallow, and infertile. The Ch’orti’ once lived in both the valleys and mountains. But studies show that beginning with colonization, non-Indigenous people gradually acquired large swaths of Ch’orti’ land, in a process rife with injustices such as forced labor, official abuses of power, and repression of efforts to reclaim land, largely leaving the Ch’orti’ with unproductive mountainside land. The region’s limited irrigation infrastructure concentrates in the valleys, increasing agricultural productivity there, while farming on Ch’orti’-inhabited mountainsides remains rainfed, and more vulnerable to fluctuations in rain.

Drought Protection Failures

What could the Guatemalan government do to protect populations from the foreseeable harm of drought, as its international human rights obligations require? Or, in climate-change terminology, what “adaptation” measures can it take to reduce the harm of the current climate and its expected changes, in a warming world? Increasing investment in public services and toward a universal social protection system would reduce vulnerabilities.

The authorities could address the land concentration that they recognize to be a “principal factor” behind food insecurity, by providing farmers access to more, better land, and returning or providing compensation for lands taken from Indigenous communities in violation of their rights. The United States sponsored a coup against the last Guatemalan president to champion major land reform, in 1954, and land was also at the heart of Guatemala’s 36-year civil war, ending in 1996; during the war, the government committed acts of genocide against Mayan Indigenous communities, a UN-mandated truth commission later concluded.

Improving water management and dramatically expanding irrigation systems, thereby reducing farmers’ dependence on erratic rain, would also be a high impact measure to protect populations from drought, as the government has long recognized. Its national irrigation policy for 2013-2023 identifies access to irrigation as an “essential element of the strategies to combat food insecurity and rural poverty.” The policy underscores that irrigation allows farmers to multiply their production and income, and that no other agricultural technology or policy offers benefits of the same magnitude.

Those interviewed—government officials, climate change and agricultural experts, aid workers, community leaders, and farmers—agreed that irrigation systems would provide essential protection. They would allow small-scale Dry Corridor farmers to grow crops and vegetable gardens throughout the year, instead of just during the rainy season, and to fill the rainy season’s pauses in precipitation, including the decrease in the middle of the season known as the “mid-summer drought,” or canícula.

The stark contrast between the barren brown fields of rain-fed farmers, and the green, productive plots of farmers with access to irrigation, was evident when Human Rights Watch traveled to the Dry Corridor before the start of the rainy season. Unfortunately, the brown fields far outnumbered the green, as irrigation was virtually nonexistent in the Dry Corridor communities we visited, where residents generally cannot afford the irrigation infrastructure.

(Left): Field of crops planted outside of the rainy season in a Dry Corridor town in Baja Verapaz state, Guatemala, thanks to an irrigation system the farmer had the resources to set up – an exception for the community, which generally lacks irrigation. April 2022. (Right): Land without irrigation from the same Dry Corridor area in Baja Verapaz state, Guatemala, April 2022.

© 2022 Max Schoening for Human Rights WatchThe Guatemalan government has made minimal progress expanding irrigation coverage. In 2013, the Ministry of Agriculture, Ranching, and Food reported that of Guatemala’s 2.6 million hectares of potentially irrigable land, only 337,471 hectares were irrigated. The ministry aimed to increase irrigation by 60,000 hectares by 2017. But its annual reports indicate that it fell far short of this goal. Subsequent gains were also modest. As summarized in a 2020 UN report, Guatemala has “very little irrigation infrastructure, and it is principally in the hands of big export companies (sugarcane, palm, banana).”

Guatemala’s climate change plan, updated in April 2022, identifies increasing irrigation as an adaptation measure. Yet, the stated goal is to expand coverage to at least 4,500 hectares by 2025, just 0.2 percent of the national potential identified in 2013. The then-agriculture minister, who acknowledged that irrigation projects have been “marginal,” said that a more ambitious plan was coming.

The ministry later announced that part of this plan, which is not yet public, is a 148 million quetzal (US$19.1 million) investment to build and improve 10 irrigation projects over the next decade, focusing in the Dry Corridor. Updated figures say that Guatemala actually has 3.9 million hectares of potentially irrigable land, of which 447,000 are currently irrigated. To protect those hardest hit by droughts, the plan will need to ensure that irrigation reaches, and remains affordable for, even the most vulnerable subsistence farmers.

The lack of progress in expanding irrigation is not for a lack of water. Guatemala is a water-rich country—water availability per capita is above the world average. Even the annual rain in the Dry Corridor is not particularly low compared with other arid regions of the world where agriculture is successful, officials and experts said.

The heart of the problem is the uneven distribution of rain, both geographically and across the year, with the government reporting increasingly intense rains falling on fewer days. Guatemala needs climate resilient, sustainable infrastructure to capture and store heavy rain—as recently as 2018, the country could only store 1.5 percent of seasonal water production—to tap into water sources, and transport that water to crops via irrigation.

Still, water is far from unlimited, and Guatemala’s annual rainfall is expected to decrease with climate change. So expanding sustainable, equitable irrigation will have to go hand in hand with efforts to protect the valuable resource. This should include increasing forest cover: according to the government, deforestation is a major threat to the Dry Corridor’s hydrological cycle, with only 22 percent of the region’s cover remaining as of 2010. Half of Guatemala’s forests disappeared in the last 65 years.

All told, the consensus of officials and experts interviewed was that Guatemala does not suffer from a lack of water, but from a lack of government policies and infrastructure to capture, store, and distribute it.

Tropical Cyclone Protection Failures

By the time Human Rights Watch visited Quejá, Sesab, and El Esfuerzo Chicojuc, a year and a half had passed since Eta and Iota, but the Guatemalan government had done little to help communities recover or to protect them from the risk of further flooding and landslides.

Following the catastrophe in Quejá, Guatemala’s disaster agency, the National Coordinator for Disaster Reduction (CONRED), declared the village uninhabitable because of the high risk of more landslides. The agency also determined, in a February 2021 report, that much of New Quejá was also “highly susceptible to landslides.” More than 280 families had relocated there on their own accord, and the agency recommended that residents of New Quejá be “on alert” until they could possibly relocate to a safer area.

But the only relocation option the government presented to Quejá survivors posed a major potential setback to their standard of living. Officials offered fewer than three-quarters of the families plots of land for homes on the outskirts of the municipality’s town center, in an area called El Mirador, about a 40-minute drive from Quejá and New Quejá. The plots are smaller than the ones the residents had.

More important, El Mirador has no land to farm for food, as the community had done for more than a century in Quejá. The round-trip cost to farm their land in Quejá and New Quejá would be 20 quetzals (about US$2.60). This would most likely be prohibitively expensive for many residents, forcing them to rely more heavily on wage labor to feed their families in an area with limited work opportunities.

Homes in New Quejá, Alta Verapaz, March 2022. © 2022 Max Schoening for Human Rights Watch.

The community rejected that offer around February 2021. Meanwhile, because CONRED determined that New Quejá was a high-risk area, the government did not help build any new housing for the survivors who had relocated there. They struggled, with their own scant resources, to build poorer quality houses than they had in Quejá. Some attempted to migrate to the United States.

Others did not have the resources to relocate. Roughly 30 families returned to Quejá, even though the government declared it uninhabitable because of the landslide risk.

Rolando is one of the Quejá survivors who had no option but to stay. The landslide buried his three children, wife, mother, father, brothers, and sisters. When we interviewed him in April 2022, he had no remaining land, and scraped by as a day laborer, making 35 quetzals (US$4.60) per day on the days he could find work. “I lost my whole family and the government turned its back on me,” he said. He said he would like to migrate but did not have the resources.

A year and a half after the landslide, the government reoffered the El Mirador plots and housing to Queja survivors. High-level national government officials, the governor, and mayor met with community leaders on May 26, 2022, saying they were making an “emergency” proposal to prevent another disaster, given that the rainy season was starting.

They would do a recount of the families in need of housing, to ensure that those left out from the prior offer would benefit. But if residents did not accept the offer by the time they next met, a week later, the option would be off the table, the officials said. They also said they would help the community buy farming land years into the future, but did not identify where. At the next meeting, on June 1, the community agreed to move to El Mirador, where they cannot farm.

Despite what the authorities had said was an emergency, as of February 2023, the government had not followed through in providing land or homes for surviving families to relocate to El Mirador. Community members said the government had “abandoned” and “forgotten” them. The number of families who have returned to Quejá—officially declared uninhabitable—has risen to around 60.

Quejá survivors are far from the only Guatemalans waiting for government support to rebuild homes. CONRED identified 13,292 homes damaged by Eta and Iota, 2,937 of which had “severe” damage. The government plans to replace or rebuild the severely damaged homes, but as of May 2022, had only built 101, and aimed to finish another 290 by the end of the year.

A major obstacle to rebuilding is that, as in Quejá, most of the homes cannot be rebuilt on the same land because of the risk of flooding and landslides. The government does not have an institution or policy dedicated to helping disaster-affected or at-risk residents get land needed to relocate.

CONRED, the disaster agency, did not visit Sesab after Eta and Iota to assess the damage or the risk of future flooding. Community members said that when the lagoon drained, they returned and used their own resources to repair or rebuild 11 flooded homes, fix the local school, and reconstruct the village’s destroyed health post.

The authorities’ longtime failure to connect Sesab to a road on which vehicles can travel—it is about a mile walk to the nearest such road—impeded residents from receiving food assistance officials were distributing following the flood. When the community returned, many children suffered from diarrhea and vomiting, which community members attributed to contaminated water. They said they have never had access to electricity or piped water—instead relying on rain and water springs for drinking and household use, with some springs a three-hour walk away.

In El Esfuerzo Chicojuc, residents were not aware of any government actions to reduce the ongoing risk of flooding posed by the bordering river. Officials visited the area after Eta and Iota to survey the damage, but the community had not heard from them since, a local leader said. The community said they asked the municipality to help remove sand inhibiting their crop production, to no avail. Their lands flooded again in February 2022, and as of the end of May 2022, the year’s first crop plantings were not growing.

Migration as a Coping Strategy

With the Guatemalan government’s protection measures lagging, many drought- and tropical cyclone-affected Guatemalans have had little practical choice but to try to cope through migration, both internally and internationally. We interviewed 15 people who said that the impact of recent droughts or tropical cyclones, or both, substantially influenced their decision to try to migrate to the United States.

The IPCC, UN agencies, and the US government have also identified drought-linked food insecurity as a factor contributing to migration from Guatemala to the United States. The IPCC said in its report published in 2022 that international migration from Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador is “partly a consequence of prolonged droughts, which have increased the stress on food availability in these highly impoverished regions.” The International Organization for Migration (IOM) also documented tropical cyclones as a potential migration trigger.

As the IPCC has noted, more research is required to determine the degree to which droughts and tropical cyclones have caused Guatemalans to migrate, and the extent to which those climate and weather events, in turn, have been caused by global warming. What is clear, and receiving growing recognition, including by the IPCC, IOM, policy experts, and advocates, is that movement away from climate harm is a potentially crucial adaptation strategy to reduce exposure to the impact of climate change. As stated in the October 2021 White House report, “migration is an important form of adaptation to the impacts of climate change.”

Yet the common migration path from Guatemala to the United States is dangerous. Safe human mobility requires legal pathways, which are inaccessible to the vast majority of people migrating to the United States due to extreme weather events, regardless of whether caused by climate change. Current US law has no legal pathways designed to receive people displaced by these events. The October 2021 White House report recommended creating a new pathway to legal status for migrants fleeing serious threats to their lives because of climate change, but the US government has not adopted any.

While not tailored to climate or weather events, refugee resettlement and asylum could provide US legal status to Guatemalans in limited circumstances affected by extreme weather events if other factors would establish grounds for eligibility. Refugee resettlement grants legal entry from outside of the United States for refugees of “special humanitarian concern.” Asylum is a potential option for people inside the United States or who are able to obtain an appointment at a US port of entry.

Fleeing climate impacts is not a basis, by itself, for asylum or refugee resettlement, both of which require meeting US law’s narrow definition of a refugee, which is based on the well-founded-fear-of-persecution standard in the UN Refugee Convention. Some people affected by the climate may satisfy the criteria because they also face persecution by the government or other actors the government is unable or unwilling to control. Weather and climate events could potentially be a factor relevant to a finding for relief in other cases, such as when the country of origin discriminates in who gets assistance or protection.

But these will most likely be a small slice of cases given current application of US asylum and refugee law. US asylum officers and other decision makers would need to understand the intersection between climate impacts and other legal grounds for asylum or refugee resettlement and be willing to look at the totality of circumstances involved in claims for international protection.

Making matters worse, US President Joe Biden’s 2023 “asylum ban” rule will make asylum in the US nearly inaccessible, in violation of international human rights and refugee law. The asylum ban, which is in effect pending a federal court of appeals decision expected by the end of 2023, comprises an expedited deportation program that is likely to subject people to unfair procedures without access to counsel and a “third country transit ban” (earlier versions of which have been found unlawful by two federal courts) that would require Guatemalans to seek asylum in Mexico before seeking asylum in the US.

The policy requires asylum seekers to lodge their claims through the cellphone application “CBP One” and punishes those who cross the border irregularly by barring their legal readmission for five years. Appointments are extremely limited and usually book up within minutes, meaning that many asylum seekers wait for months, trying each day to secure a spot. The result is electronic “metering” – forcing many asylum seekers to wait in dangerous conditions in Mexican border regions for an indeterminate amount of time.

Unlike many other countries, the United States has not broadened its asylum system to provide “complementary” protection from deportation for people who are fleeing a real risk of serious harm, but do not meet the refugee definition because their fear of return is for reasons other than being persecuted on account of one or more of the specific grounds of race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or particular social group membership. Filling this gap in law could protect many extreme weather-affected migrants and bring the United States closer in line with its international human rights obligations to protect their rights to life and physical integrity.

One option the Biden administration has is to designate Guatemala for Temporary Protected Status (TPS). TPS is a temporary suspension of deportation that the executive has the authority to unilaterally apply for all nationals of a country, based on the finding that environmental disaster or other extraordinary and temporary conditions prevent their safe return. In contrast to complementary protection, it applies on a country-by-country rather than a person-by-person basis, and covers only people already in the United States at the time of designation, not new arrivals.

In 2022, groups of 33 US Senators and 84 US Congresspeople, sent letters to the Biden administration asking it to designate Guatemala for TPS, largely based on the ongoing effects of Eta and Iota, and droughts, and the Guatemalan government reportedly requested the designation as recently as June 2021. But the Biden administration has not acted.

In June, the United States signed a declaration with Canada, and 18 Latin American countries, committing themselves to “create the conditions for safe, orderly, humane, and regular migration,” including by expanding legal pathways and protection for migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees. The declaration did not include a commitment to create a legal pathway for migrants fleeing the impacts of climate change, as the October 2021 White House report had recommended.

Mexico also joined the declaration, but its immigration policies continue to compound the danger of migrating from Guatemala to the United States. The country has signed and incorporated into its law code the 1984 Cartagena Declaration, which provides that a person can qualify as a refugee for having, among other reasons, fled “circumstances which have seriously disturbed public order.” This could be interpreted to allow people fleeing extreme weather events to obtain refugee status in Mexico. Yet, the country’s policies have made it increasingly hard for people to obtain international protection in Mexico or to reach the US border.

Responding in large part to pressure from the US government, Mexican agents operate immigration checkpoints throughout the country, board buses, pull over cars, stop people in airports, raid hotels, and patrol parks, plazas, and railway lines, detaining hundreds of thousands of migrants every year. Mexico deports tens of thousands of Guatemalans every year. There is no evidence that these measures have reduced the number of people attempting to migrate. Instead, they have driven migrants to choose more dangerous routes, increased the profitability of smuggling, and created new opportunities for extortion.

Dangerous Migration

Emilio migrated to the United States in July 2021. He cried when recalling saying goodbye to his family, who risked their land as collateral to fund his journey. With his crops failing and his family rationing food, he was, as some of his country people say, not seeking the American dream, but fleeing the Guatemalan nightmare.

Smugglers put him on a bus in southern Mexico packed with about 90 other migrants. A few days into the journey, Mexican authorities stopped the bus, detained him for two weeks, then deported him to Guatemala. Emilio had paid smugglers 40,000 quetzals (about US$5,200) up front for three tries, and if he did not make it, his family would lose their land. He immediately tried again. This time when Mexican authorities stopped the bus, they demanded bribes from the migrants, and let them pass.

In northern Mexico, near the border, smugglers housed Emilio and dozens of other migrants in an abandoned house with no bathroom. After about a month, a guide took him and a group of others through the scorching desert and into the United States. Before sleeping in the desert, they rubbed themselves with garlic to repel snakes. After eight days, everyone made it.

Emilio’s journey was hardly the most difficult we documented. Beginning in southern Mexico, several Guatemalan migrants said smugglers transported them in overcrowded freight trucks, with limited access to water. Some fainted in the heat. On the verge of dying was how one man described feeling—as he struggled to breathe, locked in a stifling hot trailer, with no water and more than 300 other men, women, and children—when Mexican authorities broke open the back door of the truck, which had stopped along a highway. In December 2021, a truck carrying more than 150 migrants overturned in Chiapas, Mexico, killing 56 people, the majority of them Guatemalan.

A Guatemalan man who attempted to migrate to the United States in 2021 said that in Mexico, he saw smugglers hit other migrants with fists and pieces of wood. Another said smugglers separated about 20 men, women, and children from his group and threatened to kill them unless the migrants made them a large payment. Earlier in 2021, a group of 16 Guatemalan migrants trying to reach the United States were massacred in northern Mexico, with alleged police involvement.

For migrants who make it through Mexico, the life-threatening desert crossing into the United States often comes next. Oscar experienced the dangers firsthand. On his fourth day of crossing the desert, he and the group of migrants he was with were informed that they were one hour from their US pickup point. They dropped their supply packs, believing they no longer needed them, and wanting to lighten their loads. But they kept walking for hours, and nothing.

Oscar was exhausted, hungry, and thirsty, without water or food. Night approached. Unable to keep pace with the others, he lay down, and as much as he tried, could not get back up. He remembers having seen a road nearby and telling the group to leave him. They did. After he regained some strength, the next morning he walked to the road and turned himself in to US border agents.

Deported back to Guatemala, Oscar was afraid to try again. That fear increased when, a few months later, around May 2021, a young man from his town lost his life trying to cross the desert into the US. He had passed out and died in the more than 100-degree heat, according to a witness we interviewed who was traveling in the same group. The young man left behind a 22-year-old widow and two young children in Guatemala, saddled with thousands of dollars in debt, and plunged deeper into poverty and food insecurity.

As frightened as Oscar and his wife were, food at home was scarce and the 10 percent monthly interest was accruing on the 20,000 quetzal (roughly US$2,600) loan he had taken out for his trip. The lender was pressuring him to repay. So he took out a second loan, with the same terms, for another try. This time he made it and completed the 85,000 quetzal (about US$11,000) payment to smugglers for the full, successful trip. He is one of more than 50 people from his village who have migrated to the United States amid droughts and crop losses over the past several years, community leaders said.

José and Luis, of Quejá, got separated from their guides when attempting to cross the desert in 2021. José trekked for nine days alone, scavenging for water, before making it to Tucson, Arizona. By the time Luis was separated, one migrant had already said he could not continue and was left behind in the desert. Once separated, Luis and six other migrants walked in circles for four days, without a phone signal, fruitlessly searching for water. He feared he would not survive. Exhausted and down to about half a liter of water each, they stumbled upon a road and turned themselves in. Expelled to northern Mexico, Luis rested for five days, and then afraid but determined, tried again, this time successfully.

Dangerous desert crossings are a direct—and expected—result of decades-long US immigration policy to heavily enforce the US-Mexico border. The US government’s “prevention by deterrence” policy, adopted in 1994, predicted that it would deter migration and push it to more remote and “hostile terrain,” including the “searing heat of the southern border,” where migrants “can find themselves in mortal danger.”

A 1997 US Government Accountability Office (GAO) report to Congress predicted that the strategy would lead to an increase in migrant deaths from desert and mountain crossings. Subsequent reports to Congress presented evidence that “prevention through deterrence” was in fact leading to migrant deaths. Aware of the mounting death toll, the US government has continued to increase border enforcement.

In fiscal year 2022, according to Customs and Border Protection (CBP), at least 850 people died attempting to cross the US-Mexico border, up from 546 deaths the prior fiscal year. Separately, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) counted 487 dead or disappeared migrants in calendar year 2022 and has counted 154 since the start of 2023. CBP and IOM do not coordinate their data collection; therefore there is overlap between these datasets as well as serious undercounts in both datasets because an untold number of human remains are never found. Global warming will likely increase dehydration and deaths, according to a recent study.

Heavy border enforcement, and the lack of pathways to legal status, also increase migrants’ need to pay smugglers to help them avoid detection. So, if they do make it to the United States, they initially must send much of their hard-earned money to lenders and smugglers, rather than their struggling families.

Oscar’s wife said she felt physically ill from fear of not being able to repay their debt. To get to the United States in 2021, Oscar, Rafael, and Emilio ultimately took on loans between 85,000 and 130,000 quetzals (roughly US$11,000-US$17,000), at 7 to 10 percent monthly interest. As of mid-2022, Emilio had gotten his debt down, while Rafael’s and Oscar’s had grown.

Earning minimum wages in restaurants and a store in the United States, the three men were sending between $650 and $1,300 to the lenders each month, and 5 to 25 percent of that to their families in Guatemala. The little remaining money they spent on a spartan living, always knowing they are under threat of possible deportation from the United States, with the hope that, as they pay off their debts, their sacrifice will improve their families’ future.

Governments Should Act

Droughts and tropical cyclones have deepened deprivations across Guatemala, pushing many people to a breaking point. In the absence of urgent government action, human-induced climate change threatens to make the problem much worse.

All governments should rapidly reduce greenhouse gas emission to prevent the worst outcomes of climate change.

Guatemala should adopt effective, rights-respecting adaptation policies to protect the population from the foreseeable harms of droughts and tropical cyclones, with special attention to individuals and groups already marginalized by government action or inaction, such as Indigenous people, people living in poverty, and women and children.

The United States and other donor countries should assist these efforts. To live up to its commitments under the Los Angeles Declaration, the regional pact to create the conditions for safe, orderly, humane, and regular migration, the United States should expand safe and legal pathways and access to protection for Guatemalans and others migrating and fleeing extreme weather events. A good place for the United States to start is by establishing a complementary protection standard for those facing a real risk of serious harm if sent back.

The failure to act will lead to many more Guatemalans, like Rafael, being caught between hunger and desperate poverty at home, and the prospect of journeys to the United States that threaten insurmountable debt, or even death.