Unwelcome Responsibilities

Spain's Failure to Protect the Rights of Unaccompanied Migrant Children in the Canary Islands

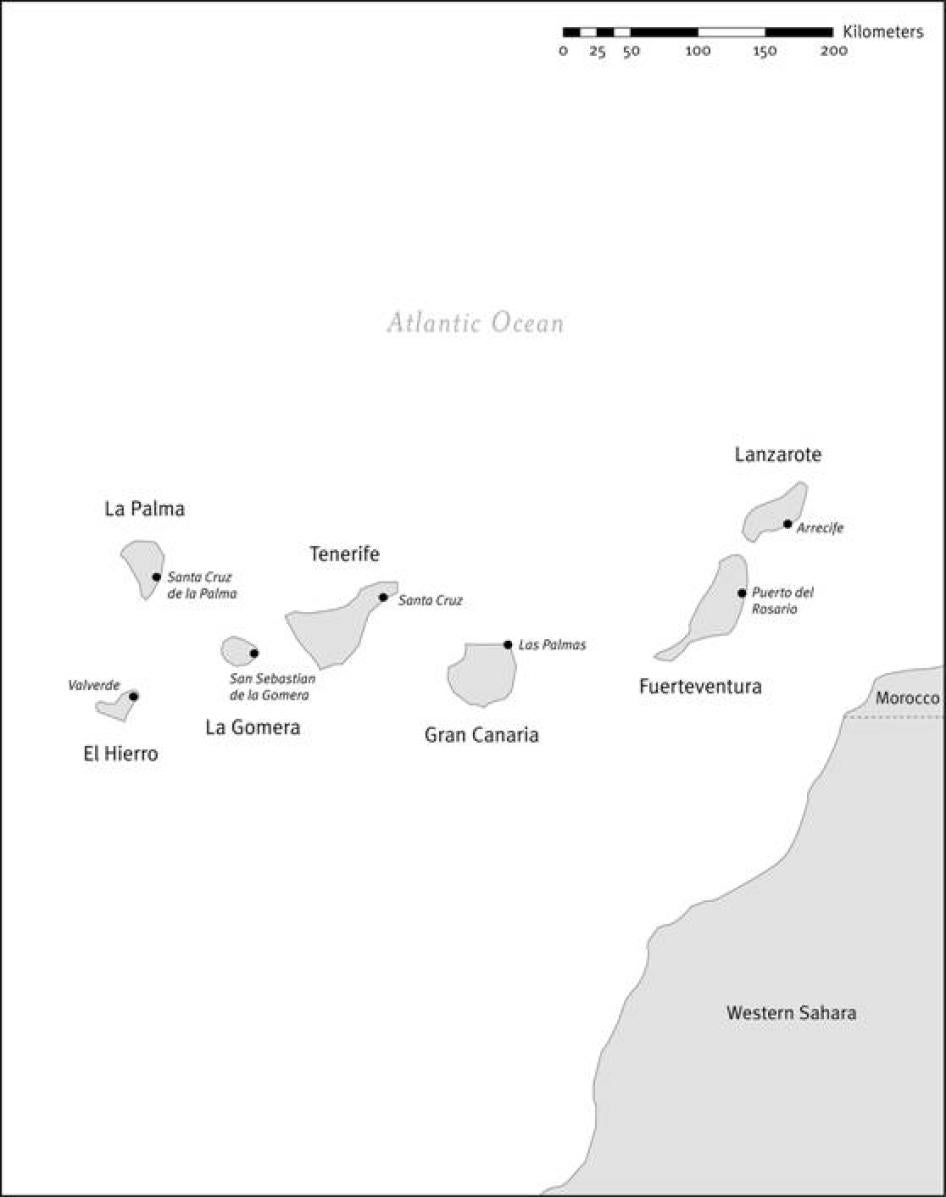

Map of the Canary Islands

2007 John Emerson

Location of the Canary Islands

2007 John Emerson

I. Summary

I am not happy here; if I could I would leave this center. We don't receive any good food. When we tell them that we are hungry they tell us that we were starving in Senegal and should be happy to be given food at all.

Lakh S., age 17, La Esperanza emergency center, Tenerife

We are not happy here; we know that we won't be taken to the peninsula [mainland Spain]. The majority wants to return to Morocco. We're tired. The [staff] hit us and we are tired. Before your visit the center smelled very bad. We don't live well and we don't eat well.

-Malik R., age 14, Arinaga emergency center, Gran Canaria

The Canary Islands must not turn into Africa's daycare center.

-Jos Lus Arregui Sez, director general, Canary Islands Child Protection Directorate

In response to the unprecedented arrival of some 900 unaccompanied children by boat from Africa in 2006, Canary Islands authorities opened four emergency centers to provide care for several hundred children. Conceived as a temporary solution to deal with an exceptional situation that overloaded existing capacity, these emergency facilities have in effect become permanent-neither regional nor national authorities have any plans to close them. On the contrary, Canary Islands authorities plan an expansion of emergency center capacity, while national authorities maintain that the situation in the Canary Islands is not within their responsibility.

The 400-500 migrant boys who currently stay in emergency centers find themselves in makeshift and large-scale facilities. The centers are regularly overcrowded due to the inability of authorities to keep pace with the continuous flow of arriving children by transferring them to more appropriate care arrangements. Placing children in emergency centers rather than the traditional care institutions where conditions and services are typically much better has direct and concrete adverse impact on children. In comparison with existing care facilities in the Islands, children in these newly created centers are isolated from residential neighborhoods and cut off from municipal services, and are severely limited in their freedom of movement. The children receive substantially fewer hours of education, often limited to one or two subjects. They may be housed with much older children, and are at risk of being subject to violence and ill-treatment by other boys as well as by staff in charge of their well-being. Lacking other recourse to protect themselves, some children abscond from their residential centers.

Conditions are particularly bad in two emergency centers:Arinaga, on the island of Gran Canaria, and La Esperanza, on Tenerife.Human Rights Watch documented allegations of high levels of violence and ill-treatment at Arinaga center, especially against younger children, perpetrated by peers as well as staff working at the center. At La Esperanza center abuses allegedly inflicted upon children between August and December 2006, by their systematic nature and severity, would amount to inhuman and degrading treatment. Authorities in charge, including the Child Protection Directorate, the Police, and the Office of the Public Prosecutor, consistently failed to effectively oversee and investigate conditions in these centers.

Children in the emergency centers have nowhere to turn for help.No confidential complaints mechanism in the centers is available, and children have no access to lawyers. Children who manage to approach law enforcement personnel may find that they are returned to their centers without any tangible action on their complaints.

Upon arrival in the Canary Islands, unaccompanied migrant children may be held in police and civil guard stations for prolonged periods, without seeing a judge and without access to a lawyer who could challenge their detention. Some children told Human Rights Watch that they remained in police stations for several days, and one child was held for two weeks, for no other apparent reason than the registration of basic information. All unaccompanied children arriving in the Canary Islands are screened for a variety of illnesses, but tests are performed without their informed consent and children receive no information about test results unless they specifically ask for it.

Unaccompanied children arriving in the Canary Islands receive no information about their right to seek asylum, whether on arrival or within residential centers. Authorities systematically consider them economic migrants. Children in emergency centers, in particular, are often not interviewed upon their admission. As a result, potential grounds for subsidiary protection or refugee status remain undetected. Human Rights Watch spoke to several children who should have received information and assistance in accessing asylum procedures.

Children typically remain without identification papers even though Spanish law requires that children be provided with documentation and many unaccompanied migrant children are further entitled to temporary residence permits. Authorities prioritize migration control measures over the granting of children's entitlements and use discretionary and possibly discriminatory criteria in meeting these entitlements. Identification papers and residence permits are either not issued at all or they expire on a child's 18th birthday. As a result, upon turning 18, children are pushed into an irregular status as authorities fail to identify a durable solution in which full respect for their rights is guaranteed.

Children have no direct contact with the guardianship institution that decides on their care arrangement and is mandated to ensure their best interest in all decision making. Staff members in residential centers who are in direct and daily contact with these children in turn have very limited influence over care arrangements. Several staff members expressed profound concern about prevailing practices that violate children's rights and undermine their own efforts to care for and facilitate children's development and integration.

After repeated pressure from the Canaries government, the central government entered into an agreement to transfer a total of 500 children from the Canaries to other regions, with costs of the transfers to be borne by national authorities. The implementation of this agreement, which is now complete, has been slow, politicized, and insufficiently coordinated. It has had only limited impact on easing the situation in the Canary Islands as the number of children transferred was almost equaled by the number of new arrivals. Moreover, no Moroccan children have been chosen for transfers to the mainland under this agreement, even though they account for nearly one-third of all unaccompanied children who come to the Canaries.

Simultaneously, the government of Spain has renewed plans to repatriate unaccompanied children in an accelerated manner. It recently signed bilateral readmission agreements for unaccompanied children with both Morocco and Senegal. Three autonomous communities and one ministry currently are implementing or negotiating the construction of reception facilities for repatriated children in both countries, some of which are funded by the European Commission. As Human Rights Watch and other organizations previously documented, Spain has conducted illegal and ad hoc repatriations of unaccompanied children to dangerous situations in Morocco, in disregard of children's best interests and procedural safeguards. The readmission agreement with Morocco does not sufficiently spell out provisions that would ensure that all repatriation decisions are carried out on a case-by-case basis, in full respect of procedural safeguards, the best interest of the child, and the principle of non-refoulement.

Irrespective of whether these children qualify for asylum or other forms of protection they are entitled to special care and assistance provided by the state. Even if these children have no right to remain in the country, while they are on Spanish territory the government of Spain is obliged to guarantee their full entitlements as spelled out in the Convention on the Rights of the Child. The government must identify a durable solution in addressing the fate of these children as soon as possible after their arrival. It must provide them with access to international protection procedures, and it may proceed with family reunification only after a thorough assessment of whether such a move is in the child's best interest and without risk to his or her well-being. If the return of a child is not possible on either legal or factual grounds, the government of Spain should provide these children with real opportunities for local integration and with a secure legal status.

Key Recommendations[1]

To the government of Spain and the Canary Islands government

Immediately devise and implement a plan to close emergency centers as care facilities for unaccompanied migrant children and transfer children to alternative care arrangements-either in the Canary Islands or mainland Spain- that are conducive to children's well-being and development, and where fulfillment of their rights under national and international law can be guaranteed. Ensure that any transfer of children is carried out in a transparent and non-discriminatory manner, in consultation with the child, and in full respect of his or her best interest.

Ensure that any interim care provided by the state before children's placement in a long-term care arrangement is limited to the shortest time required and provides for these children's security and care in a setting that encourages their general development. Any interim care arrangement must comply with existing laws and regulations.

Conduct independent and effective investigations into reports of abuses and ill-treatment of children at La Esperanza and Arinaga centers and hold all perpetrators fully accountable. Include private interviews with children as an element of the investigation and ensure confidentiality of the information shared. Provide victims with access to an effective remedy, including access to medical treatment and financial compensation.

Immediately investigate children's reports of prolonged deprivation of liberty at both national police and civil guard commissariats following their arrival. Ensure that any detention upon arrival of an unaccompanied child is compliant with international law and strictly limited in time for required purposes.

Immediately provide children with full information on their rights in a language they understand, with particular emphasis on children's right to documentation, legal residence, work permits, education, and health.

Immediately provide all unaccompanied migrant children with access to a confidential complaint mechanism within and outside their residential centers and with direct contact to their legal guardian.

Immediately set up a system providing children with full information and explanations on their right to seek asylum and other forms of international protection in a language they understand. Refrain from repatriating any children who arrived in the Canary Islands until their grounds for protection are competently assessed and until a system is in place that guarantees children access to asylum procedures.

Immediately address any obstacles that may limit children's full enjoyment of their rights as a result of their transfer to other autonomous communities, within the existing coordination mechanisms, especially the Childhood Observatory. In particular, ensure that all children transferred to other autonomous communities are continuously represented by a guardian who guarantees their best interest in all decision making, that these children's care arrangements are periodically inspected and reviewed by competent bodies, and that they have full access to health services, education, and documentation. Immediately address and rectify discriminatory practices against Moroccan children in choosing children for a transfer.

To the Office of the Prosecutor General

Immediately provide the offices of the public prosecutor in the Canary Islands with guidance and sufficient resources to responsibly carry out their mandate, including the oversight of guardianship, conditions in residential centers, and competent action on any complaint received.

Immediately verify conformity of the legislative basis establishing emergency centers and conditions therein with applicable Canary Islands and national legislation.

Carry out regular and effective oversight, including regular inspections of residential centers, of all children under guardianship. Always include private interviews with children as part of an inspection. Ensure that appropriate measures are taken to protect the confidentiality of these encounters. Follow up should be conducted to ensure that children are not subjected to reprisals following an interview.

Review the legality of repatriation decisions already issued to children in the Canary Islands, taking into consideration whether the child has been heard, whether the child was granted access to independent legal assistance, whether the decision respects the child's best interest, and whether conditions for a safe repatriation are in place.

II. Methodology and Scope

This report addresses the treatment of unaccompanied migrant children in the Canary Islands after their arrival. It does not address in detail the push factors behind children's departure from their countries of origin. Human Rights Watch did not assess or conclude whether these children have a valid claim for asylum or international protection. Instead, we look at the procedures in place to guarantee that children who do have such claims can access protection, among other aspects of entitlement, to remain in Spain.

Human Rights Watch researchers visited 11 residential

centers on five islands in January 2007 and interviewed a total of 75 boys

between the ages of 10 and

In the Canary Islands we met with officials from the Child Protection Directorate, central government representatives, the Office of the Public Prosecutor, local authorities (cabildo), as well as the Canary Islands ombudsperson. In Madrid we met with officials from the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs, the Office of the Prosecutor General, the Ministry of Interior, as well as the Office of the National Ombudsperson.

All children's names have been replaced by pseudonyms. In some instances their age and the exact date and location of the interview have also been withheld to avoid the possibility of identifying the child. Some names of staff members working in residential centers have also been withheld to protect them from possible repercussion for the information shared.

1. Methodological Challenges

All children we interviewed were in care institutions where they remained following our encounter with them. They related to us information in a confidential manner that included details about violence, ill-treatment, and abuses they were subjected to or witnessed. By doing so, they put themselves in a vulnerable position because they remained in the custody of and dependent on persons they alleged to be complicit in these abuses.

This circumstance greatly influenced our methodology in conducting this research and it demanded utmost caution in using the information given by children. In particular, it prevented us from immediately raising allegations made by children with authorities in charge, as this could have put children at serious risk of reprisal that we were unable to prevent or even monitor. We thus brought details of children's allegations to the attention of authorities only after carefully assessing the risks entailed for these children, and in a manner in which risk of reprisal for the children was minimized. This included where necessary keeping confidential information that could lead to the identification of alleged victims or could lead alleged perpetrators to seek reprisal.

2. International Standards

Human Rights Watch assesses the treatment of unaccompanied migrant children in Spain according to international law and standards, in particular international human rights treaties to which Spain is a party including the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (Convention against Torture),[2] and relevant regional treaties such as the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR)[3]and the European Social Charter. As a member of the European Union, Spain is also bound by relevant European Union directives and other legislation.

3. Terminology

In line with international instruments, the term "child" refers to a person under the age of 18. An "unaccompanied child" is a person under the age of 18 who has been separated from his or her parents and other relatives and is not being cared for by an adult who, by law or custom, is responsible for doing so.[4]

This report uses the term "migrant children" to refer generally to children who have traveled to Spain from Morocco, West Africa, or elsewhere, regardless of their refugee or other legal status.[5]Our use of the term is not intended to suggest that children have no valid asylum claim.

Children were often unable to distinguish between the Spanish National Police (Cuerpo Nacional de Polica) or local Police and the Civil Guard (Guardia Civil). Children's use of the term "police" may refer to personnel from any of these law enforcement bodies unless we note that we were able to confirm the involvement of a particular law enforcement agency.

The term "residential center" refers to all residential care centers-the traditional care structures as well as the newly created emergency centers.

The term "educator" (educadores) refers to staff working in residential centers.

III. Context

1. The Phenomenon of Unaccompanied Migrant Children in Spain and the Canary Islands

The phenomenon of unaccompanied children migrating to Spain manifested itself at the end of the 1990s and significantly increased after the turn of the millennium.[6] Children have primarily arrived from Africa, especially from Morocco.[7]

In the Canary Islands, the arrival of unaccompanied children took place in two stages. The first stage includes children who have migrated to the Canary Islands since the late 1990s, predominantly from the south of Morocco, and mainly arriving to the eastern islands of Fuerteventura and Lanzarote. The second stage includes the very recent development of sub-Saharan African children arriving in the Canary Islands by boat from West Africa, mainly Senegal.

Motivations, migration routes, push factors, and profiles of Moroccan migrant children have been comparatively well researched and documented by both Spain- and Morocco-based research organizations.[8] In contrast, there is much less understanding of the push factors and profiles of Senegalese and other sub-Saharan African children migrating to Spain. The 2006 United Nations (UN) Human Development Index ranks Senegal 156th out of 177 countries, putting the country near the bottom in terms of human development and marking it as one of the most difficult countries to live in worldwide. Senegal has an adult illiteracy rate of roughly 61 percent. Over 85 percent of the population lives on less than US$2 per day, and one in five children under the age of five is underweight. In 2004, 43 percent of the population was under the age of 15.[9]

Children interviewed by Human Rights Watch typically cited their families' economic situation and the lack of opportunities as decisive factors behind their decision to migrate. With some notable exceptions, many children had attended school for only a few years before they started working. While some children had clear plans to either study or work in Spain, others pursued a childhood dream or followed the paths of their friends, brothers, or other relatives. Still others had fled war-torn countries in West Africa.

With one exception, children interviewed told Human Rights Watch that they themselves took the decision to migrate and generally sought their parents' prior consent. Although research by Human Rights Watch in West Africa indicates that families incur substantial debts to pay for the boat trip, children interviewed for this report unanimously told Human Rights Watch that the money for the trip had been earned by family members or sent by relatives from abroad. Although a majority of children and families paid substantial amounts of money for the sea passage, Human Rights Watch found no indication that the boys we interviewed had been trafficked as that term is used in international law.[10]

Human Rights Watch's findings rebut the stereotype that it is primarily street children who migrate from Morocco to Spain. Moroccan children unanimously reported that they lived with their families in their home country, although a large number talked about difficulties within their families resulting from economic pressure, divorce, or the death of a parent.

In interviews with Human Rights Watch, Canary Islands authorities, including child protection representatives, consistently also stereotyped children into negative and positive categories once they were in their care. Moroccan children were categorized as "difficult," "disruptive," "not committed to work or study," "unwilling to accept female staff," "from broken families," "living in the streets," "conflict-prone," and only "interested in making their living somehow." They were implicitly considered responsible for a variety of problems within residential centers.

In contrast, sub-Saharan African children were described as "good," "committed to their studies," "willing to integrate," "not disruptive," and "interested in working and getting on." These stereotypes were echoed by staff who worked in residential centers and were directly tasked with these children's care.

One center staff member with long-standing experience of working with Moroccan children clarified:

The stereotype of Moroccan children that is being portrayed is not justified. A small minority might have been living in the streets indeed, but the vast majority of them come from intact family structures. The problems in the centers exist because of the conditions and environment in these centers. If you put 20 Spanish children into such conditions, you would have exactly the same problems.[11]

2. Types of Residential Centers

The Canary Islands autonomous community has set up separate structures to take unaccompanied migrant children into care.[12] Foreign children are placed only in institutions, rather than with foster families. Authorities claim that families are either "unwilling to take [unaccompanied migrant] children" or that "[these] children are not used to living in family structures."[13]

Residential structures for unaccompanied migrant children that existed prior to the emergency response to the recent influx, and continue to operate, consist of long-term, small-scale, shared housing facilities for up to 12 children, known as CAMEs (centros de acogida para menores extranjeros). CAMEs are typically located within or close to residential areas. They are complemented by facilities for immediate reception, so-called CAIs (centros de acogida inmediata) where children can be placed at short notice and for a maximum of 30 days. The maximum number of children in CAIs is limited to 20.[14]The Canary Islands offers a total of 250 places in CAMEs and CAIs and has defined its capacity ceiling for foreign children in care in all residential centers to be at 250-300 places. The head of the Child Protection Directorate told us that the capacity ceiling was part of an agreement with the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs. However, a ministry representative denied that such an agreement existed and affirmed the capacity ceiling was a "unilateral declaration" on the part of the Canary Islands.[15]

The Child Protection Directorate (Direccin General de Proteccin del Menor y de la Familia) assumes guardianship (tutela) of unaccompanied children and has overall supervisory responsibility for all residential centers. The cabildos (island governments) are responsible for the management of CAMEs and CAIs, but typically contract nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) or associations to run them.[16]

Responding to what it described as an exceptional situation of unaccompanied children arriving on its shores in numbers beyond the capacity of existing care facilities, the Canary Islands Child Protection Directorate opened a total of four special emergency centers (Dispositivo de emergencia de atencin de los menores extranjeros no acompaados en Canarias DEAMENAC) from March 2006. Three of the four emergency centers are large-scale facilities that accommodate more than 75 children each.[17] These centers are converted makeshift facilities located in isolated areas distant from residential neighborhoods and municipal services. Designed as a temporary solution to cope with the number of arrivals, they have de facto become permanent. No strategy at either the regional or national level exists to date to replace them. On the contrary, Canary Islands authorities are considering establishing a new emergency center on Lanzarote.[18]

Resistance by the local population to the presence of centers for migrant children is reportedly an obstacle in the opening of new CAMEs. Although the Child Protection Directorate reported that there are "very few incidents of xenophobia or racism," this is contrary to the experience on both Fuerteventura and Lanzarote islands.[19] As one emergency worker explained, "If there are no places available in CAMEs, children are forced to stay here [in the CAI] for unlimited time. It's very difficult to open a new center. The population doesn't want residential centers for children, neither for nationals nor for foreign children-much less for foreign children."[20]

The establishment of emergency centers is reportedly regulated through an order issued by the social affairs department in 2006, but Canary Islands authorities were not able to tell us whether the order sets forth minimum standards for such centers. Despite repeated requests, none of the Canary Islands officials interviewed by Human Rights Watch was able to provide us with a copy of the order.[21]

Emergency centers are directly managed by the Child Protection Directorate, but it has contracted the NGO Asociacin Solidaria Mundo Nuevo (Mundo Nuevo) to run them. Mundo Nuevo faced considerable challenges in taking on this contract. Although the organization had previous experience in running centers for children in care, it had no previous experience of working with foreign children whose situation brings a range of legal issues to be dealt with. It had to almost double its staff in a very short time and currently has 200 staff on its payroll working with foreign children.[22]

The separation of foreign children from their Spanish counterparts in long-term residential care is a significant obstacle to their successful integration and increases their segregation and vulnerability.[23] Studies have consistently established the negative impact of institutionalization of children at risk and the existence of high rates of violence in large-scale residential care. As a consequence, countries with a predominant use of large-scale institutions have deliberately moved away from this kind of care.[24]

3. Statistics and Figures

National figures

The latest available national figures on unaccompanied migrant children in Spain date from 2004.[25] According to these figures from the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs (Ministerio de Trabajo y Asuntos Sociales), 9,117 unaccompanied foreign children were taken into care that year, most of them in Andalucia, Valencia, Madrid, and Catalunya. Out of these children, only about 2,000 remained in care by the end of 2004.[26]

Contradicting these figures, the national ombudsperson reports much lower numbers of unaccompanied migrant children in the care of Spanish authorities in 2004.He reports that only 1,873 migrant children were taken into care countrywide in 2004, relying on data from the Ministry of Interior's Commissariat on Foreigners and Documentation (Comisara General de Extranjera y Documentacin).[27]

The discrepancy is the result of the lack of uniform recording of data on unaccompanied migrant children.Although a law enacted in 2005 requires the creation within the Police Directorate of a national registry on unaccompanied migrant children, this has not yet happened.[28] Representatives from the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs told Human Rights Watch in February 2007 that they were "working with the Police to activate a system to register children based on their fingerprints."[29]

Canary Islands figures

A report by the Canary Islands Parliament documents that until 2005, more than 90 percent of unaccompanied migrant children originated from Morocco, particularly from the country's south. From January 2006 onwards, the number of sub-Saharan African children, mainly arriving from Mali and Senegal, increased significantly.[30]

Source: Parliament of the Canary Islands Official Bulletin , No. 125, March 28, 2007, p. 26. http://www.parcan.es/pub/bop/6L/2007/125/bo125.pdf(accessed April 30, 2007).

The same report also gives the average number of

unaccompanied children in the protection system for the past seven years.One hundred children were in the Canary Islands protection system in 2000. That figure

gradually increased and reached its first peak with 256 children in 2003. It

leveled to around 200 children for 2004 and 2005. For 2006, the number of

unaccompanied children in the protection system reportedly rose from a low of

just under

Children are distributed among the Canary Islands according to an island's size and population. The majority of residential centers are found on the two biggest islands, Gran Canaria and Tenerife.

Table 1:Distribution of Children per Island and Type of Center (as of February 5, 2007)[32]

Name of Island |

Number of places per Island (CAMEs and CAIs) |

Percentage of total places |

Actual number of children |

Difference |

Gran Canaria |

82 |

32.8 |

80 |

-2 |

Tenerife |

75 |

29.8 |

99 |

25 [sic.] |

Lanzarote |

27 |

10.9 |

42 |

15 |

Fuerteventura |

24 |

9.6 |

25 |

1 |

La Palma |

22 |

8.9 |

18 |

-4 |

Gomera |

16 |

6.3 |

16 |

0 |

Hierro |

4 |

1.7 |

6 |

2 |

Total number in CAMEs and CAIs |

250 |

100 |

286 |

|

DEAMENAC- Agimes or 'Arinaga' |

139 |

|||

DEAMENAC-Arucas |

24 |

|||

DEAMENAC-Tegueste |

74 |

|||

DEAMENAC-La Esperanza |

166 |

|||

Total number in DEAMENACs |

403 |

|||

Total number of unaccompanied children in residential centers |

689 |

|||

Unaccompanied children in juvenile detention facilities |

50 |

|||

Total number of foreign unaccompanied children under public guardianship |

739 |

|||

Children transferred to other autonomous communities under guardianship of the Canary Islands (up to February 5) |

32 |

|||

Children to be transferred this week (February 5) to other autonomous communities under guardianship of the Canary Islands |

8 |

|||

Total number of arrivals in 2006 |

931 |

|||

Total number of arrivals in 2007 (up to February 5, 2007) |

39 |

|||

Children transferred to other Autonomous Communities in 2006 |

231 |

|||

Children transferred to other Autonomous Communities in 2007 (up to February 5, 2007) |

20 |

Source: Parliament of the Canary Islands Official Bulletin, No. 125, March 28, 2007, p. 25.

These numbers may not include children who have escaped from residential centers but legally remain under the guardianship of Spanish protection authorities.In January 2007 the Child Protection Directorate told Human Rights Watch that there were about 100 such children.[33]

Graph 2:Countries of Origin

Nationality |

TOTAL |

Morocco |

290 |

Mauritania |

12 |

Senegal |

453 |

Mali |

115 |

Rest of sub-Saharan Africa |

61 |

TOTAL |

931 |

Source:Parliament of the Canaries Official Bulletin, No. 125, March 28, 2007, p. 24.

4. Authority and Responsibility at the Spanish National and Canary Islands levels

In contrast to adult migrants, unaccompanied migrant children are entitled to special state protection and assistance, and they enjoy the guarantees set forth in the Convention on the Rights of the Child.[34] This is irrespective of whether children are found to qualify for asylum or other forms of international protection flowing from a risk to their security and well-being in their country of origin (access to asylum for unaccompanied migrant children is discussed in Section V.3, below).

Spain is a highly decentralized state organized territorially into 17 autonomous communities (comunidades autnomas) and the two autonomous cities (ciudades autnomas) of Ceuta and Melilla. Autonomous communities are subdivided into a total of 50 provinces. The Canary Islands were granted the status of an autonomous community in 1982.[35]The Canary Islands are divided into two provinces, Las Palmas, which includes Gran Canaria and islands to the east, and Santa Cruz de Tenerife, which includes Tenerife and islands to the west. Each island has its own local government (cabildo).

The Canary Islands autonomous community is in charge of social affairs and services, while the competence over migration policy, repatriation procedures, status of noncitizens, and applications for asylum remains with the central government.[36] The autonomous community is responsible for child protection and care of all children on its territory and has adopted relevant legislation that is subordinate to national law.[37] The central government is represented in the Canary Islands through a delegate (delegado del Gobierno) and through a subdelegate (subdelegado del Gobierno) in each of the two provincial capitals, Las Palmas and Santa Cruz de Tenerife.[38]

At the national level, the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs coordinates policies and practice on unaccompanied migrant children within the central administration and with the various autonomous communities and cities through three mechanisms:[39]

1)The State Secretariat for Social Services, Family Affairs, and Disability (Secretara de Estado de Servicios Sociales, Familias y Discapacidad) gathers every three months with the directors of all autonomous community child protection services. A working group on unaccompanied migrant children was recently created, consisting of the seven autonomous communities with the highest numbers of such children. This working group, in which the Canary Islands are represented, met for the first time at the end of January 2007.

2)These meetings at the director level are complemented by technical commissions that coordinate and harmonize child protection policies across the country.

3)The Childhood Observatory (Observatorio de Infancia) includes representatives from all autonomous communities and all relevant ministries as well as NGOs. The observatory established a working group on unaccompanied migrant children.[40]

The Office of the Prosecutor General(Ministerio Fiscal), through its provincial offices and its prosecutors for children (fiscales de menores) supervises administrative procedures affecting unaccompanied migrant children, the exercise of public guardianship, and conditions in residential centers. The Prosecutor's Office is further mandated to oversee the independence of the courts. The Prosecutor General (Fiscal General del Estado) issues mandatory instructions for all prosecutors.[41]

Ombudspersons (defensor del pueblo) work at the national level as well as in each autonomous community. They oversee the state administration and report to the parliaments at the national or autonomous community level. They may receive and investigate individual complaints. The national ombudsperson is also entitled to challenge the constitutionality of an official act.[42]

Child Protection Directorate and cabildo representativesconsistently used vocabulary characteristic of a emergency when referring to the situation of unaccompanied children arriving on CanaryIsland shores in large numbers, speaking of an "avalanche" of children and the "flooding" of its protection system.[43]The Canary Islands authorities called for support by the central government and for a demonstration of solidarity by other regions of Spain, with considerable success (see Section VIII.4, below). Several government officials in the Canaries furthermore asserted that the situation is in fact a matter for the European Union to deal with and not exclusively the responsibility of Spain or the Canary Islands.

IV. Arrival

Children arriving in the Canary Islands reported that the Spanish Red Cross provided them with initial assistance that included clothing, food, water, and medical assistance, as needed. Some children were hospitalized after their arrival and treated for several days. All children interviewed by Human Rights Watch arrived by boat. Some children told us that their boats arrived unnoticed, but others reported that they were intercepted and escorted to the coast by the Spanish Red Cross or Coast Guard. One child reported that they were far from the Spanish coast when their boat was about to sink. According to the child, they were rescued by the "Red Cross" and taken to Gran Canaria after one-and-a-half days of further travel.[44]

Guardianship (tutela) is assumed by the Child Protection Directorate through an administrative finding that a child is in need of protection, known as a declaracin de desamparo .[45] An unaccompanied child is automatically considered in need of protection.[46] Although the law provides that a child can be immediately referred to protection services even if there are doubts about his or her age, guardianship in practice is not assumed before the age is determined through an assessment.[47] As a consequence, children spent up to two weeks at police or civil guard stations with no guardian present either during this period, the initial interview, or during the age examination.

1. Detention upon Arrival

Children told Human Rights Watch that they were brought to police or civil guard stations after receiving initial assistance from the Red Cross.They were held or detained at police stations for periods ranging from a few hours to up to two weeks. They were generally separated from adults. None of the children had access to a lawyer during this period in custody.[48]Several children reported that they did not receive enough to eat while they were at the police and civil guard stations.[49]

The following accounts were typical of those we heard from children:

"We arrived in Tenerife and were met by the Red Cross. Then we came to the Police. I was four days at the police station. I was with adults for two days, then two days with children. We had only bread and sometimes nothing to eat. Sometimes we were not given food. For two days we were not given lunch. It happened only twice. I was unable to complain because nobody ever stopped by. One guard guarded us but I was not able to speak Spanish to him. We were in a big room and I was only able to leave that room after two days. With the children I was in a cell locked up. I could only leave to go to the toilet," said 17-year-old Jean-Marie N.[50]

"We were met by the Police. I spent five days at the police station. They made an age assessment during that time. I was separated [from adults] with two other children in one cell. I received no information and have not seen an interpreter," Abdulahi F., age 17, told us.[51]

"We were met by the Red Cross. One person spoke French to me. We were brought to the Police and spent eight days at the Police. I was with other children and first in a big room. I spent two days in hospital initially. They had made a camp for children outside the police station. I spent the first day at the Police; they called an ambulance because I had high fever. I was brought to the hospital and then back to the Police," Aliou N., age 17, reported.[52]

"I spent one day in the Red Cross tent, the next day I was brought to the police station. I spent five days there. I was with two other persons in one room at the Police. We were all of the same age. I was asked the names of my parents, who had brought me to Spain, and whether I had any money with me," 17-year-old Ali S. said.[53]

"I was met by the Red Cross then I was at the Police. We arrived in El Hierro. I was at the Police with two other boys. I did not see a judge and I did not have an interview. I spent two weeks at the police station. I had only bread to eat with water. I was hungry. I was able to leave and I was in a big room," said 17-year-old Yunus S.[54]

The purpose of their initial detention appears to be the registration of basic data such as their name, nationality, age, identity of parents, place of origin, and how their travel to the Islands had been arranged. The interview to record this information on average lasted for about 10 minutes and in a large number of cases was conducted without an interpreter. While in detention children are brought to a hospital for an age assessment (see below). A small minority of children said they were brought before a judge, but only jointly with adults.

Contradicting these accounts, police officials told Human Rights Watch that children in need of protection are "never detained" and "receive treatment in full compliance with Spanish legislation."[55]

The Convention on the Rights of the Child stipulates that "the arrest, detention or imprisonment of a child shall be in conformity of the law and shall be used only as a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time." Furthermore, a detained child shall have the right to prompt access to legal representation and the right to challenge the legality of his or her deprivation of liberty.[56]

2. Age Determination

Depending on where a boat arrives, the initial authority that receives migrants is either the Civil Guard or the National Police. The National Police services the main ports on the Islands and the Civil Guard covers the rest of the coastline.[57]Initial identification of children is conducted by these authorities as well as by the Spanish Red Cross at ports of entry. Those who are presumed to be children and not accompanied are subsequently separated from adults by authorities.

Acknowledging that it is very difficult to correctly identify those who should be presumed to be children in practice, the Spanish Red Cross points out that the responsibility to decide which persons are to undergo an age determination lies with the government.[58] Authorities have the obligation to immediately inform the Prosecutor's Office about the presence of an undocumented person who might be a child. The prosecutor in turn orders an age assessment, and if the test determines that the person is under the age of 18, and he or she is unaccompanied, the prosecutor refers the child to the protection services.[59]

In January 2007 the Prosecutor's Office of the Madrid community claimed that procedures in the Canary Islands for identifying children were flawed, noting that some children had been treated as adults by Canary Islands Police and judiciary.[60] These children had not been reported to the Prosecutor's Office, but were instead treated as adults and received detention and expulsion orders by a judge, in the presence of a lawyer.[61]According to the NGOs SOS Racismo and the Spanish Commission for Refugee Assistance (Comisin Espaola de Ayuda al Refugiado, CEAR), which referred the cases to the national ombudsperson, such treatment affected persons who physically appeared to be children but who claimed to be older than 18, but also persons who stated that they were underage including one eight-year-old and one ten-year-old who were never given an age assessment by authorities.[62]

The age determination method in practice is an X-ray of the wrist bone, a method for the diagnosis of growth pathologies developed in the 1930s based on tests of Western European children.[63] Medical professional bodies have criticized both the method's inaccuracies and the practice of exposing individuals to X-rays for non-medical purposes.[64] The British educational and standards body for pediatric medicine, the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, observes that "age determination is an inexact science and that the margin of error can sometimes be as much as five years either side,"[65] and further advises practitioners that it is "inappropriate for X-rays to be used merely to assist in age determination for immigration purposes."[66]

Although the transfer of the child to a hospital for the age assessment is legally considered a period of detention, the child remains without a guardian or legal representative during that time.[67] Human Rights Watch spoke to children who had been recorded as a significantly higher age than they themselves claimed after the test and whose assessment result should have been challenged by a legal representative or the child's guardian.[68] Thirteen-year old Rashid P. recalls how his friend of the same age was treated as an adult and repatriated following the age assessment:

There were 12 of us at the civil guard station the first night. Then just four of us were there the second night: the others were my brother, another boy who ended up going to Tegueste, and another boy who they repatriated to Morocco. This last boy was my age, but the machine said he was older, I think because he is fat. I know how old he is because he studied with me, and we arrived together on the same patera [boat]. There in school, they have a document that says your age and your date of birth.[69]

A number of children told Human Rights Watch they were in fact older than the tests determined, by as many as four years.

Legal challenge to an age determination is in practice very difficult.[70] By law, medical staff are responsible for conducting the age assessment, which will provide an age range, and the lowest of possible age ranges is to be assigned to the person.[71] The Spanish ombudsperson notes that in a majority of cases, no formal age declaration is issued by the prosecutor, instead the medical report itself is taken as the basis for the person's age. He is of the view that an age declaration should always be issued by the prosecutor. Only such a formal administrative procedure would permit an age determination to be legally challenged before the courts, which is not the case if an age determination is based solely on the medical report.[72]

The Committee on the Rights of the Child calls for age assessments to take into account not only the child's physical appearance but also his or her psychological maturity. If uncertainty remains, the assessment "should accord the individual the benefit of doubt such that if there is a possibility that the individual is a child, she or he should be treated as such." The Committee further recommends that in cases where children are involved in administrative or judicial proceedings, "they should, in addition to the appointment of a guardian, be provided with legal representation."[73]

The European Council Directive on Minimum Standards on Procedures for Granting and Withdrawing Refugee Status requires that, in cases where medical examinations are used to determine age for the purpose of an asylum determination, unaccompanied children shall be both informed about the method and about the consequences of undergoing such a medical examination. They may refuse to undergo the examination. Further, the Directive requires states to seek the consent of a child and/or of his or her guardian prior to carrying out such an assessment.[74]While the Directive governs the establishment of minimum standards in relation to refugee status, the minimum standards it sets out should be more generally applied, as age determination is part of a process to establish a child's identity and not necessarily only as part of the asylum procedures. Otherwise, applying different standards of age determination to different categories of children could result in creating arbitrary distinctions between children seeking asylum and those seeking other forms of international protection.

3. Assumption of Guardianship

As noted above, an unaccompanied child is automatically considered in need of protection, and guardianship (tutela) is assumed by the Child Protection Directorate through a declaracin de desamparo. Center staff report that the declaracin de desamparo is often delayed by several months.[75] The Canary Islands ombudsperson noted in 2004 that 56 percent of unaccompanied migrant children's files included no indication of their administrative status-that is, their files did not show whether a declaration had been made.[76]

The Committee on the Rights of the Child spells out that in the case of a child outside his or her country of origin, the principle of a child's best interest "must be respected during all stages of the displacement cycle," and "a best interests determination must be documented in preparation of any decision fundamentally impacting on the unaccompanied or separated child's life." It furthermore lays out that a key safeguard to ensure the best interest of the child includes "the appointment of a competent guardian as expeditiously as possible."[77]

In similar terms, UNHCR recommends, "A guardian or adviser should be appointed as soon as the unaccompanied child is identified. The guardian or adviser should have the necessary expertise in the field of child caring, so as to ensure that the interests of the child are safeguarded and that his/her needs are appropriately met."[78]

European Union law requires that "Member States shall as soon as possible take measures to ensure the necessary representation of unaccompanied minors by legal guardianship or, where necessary, representation by an organization which is responsible for the care and well-being of minors, or by any other appropriate representation."[79] As indicated above in the context of age determinations, although the European Council Directive on Minimum Standards for the Reception of Asylum Seekers limits this requirement in scope to asylum-seeking children, in practice it should be applied to all unaccompanied children as soon as they are identified, in order to avoid arbitrary distinction at a moment when it is not necessarily determined whether an unaccompanied child falls under the asylum procedure.

4. Placements in Care

Child protection services do not follow a transparent or obvious set of criteria in placing a child into a particular type of residential center.Some newly arrived children are transferred directly to a CAME, whereas other children remain in emergency centers for indefinite periods.

We were told by Gloria Gutirrez Gonzlez from the Child Protection Directorate that younger children-those under the age of 14-are sent to Tegueste emergency center.[80]Yet, despite this criterion in place, we met 12-year-old children in Arinaga emergency center and 13-year-olds in La Esperanza emergency center.

Transfers within the Canaries

In the absence of clear criteria for placement, children interpret transfers to certain centers as punishment for their behavior and told us that they risk transfer to La Esperanza center 0n Tenerife if they didn't behave well. Seventeen-year-old Ahmed A. described the prevailing view among children in Arinaga:

Yesterday, for example, there was a big meeting among all educators in which they decided who was going to Tenerife: 24 children will be transferred. They are being told they are going to houses, not the center in the mountains [La Esperanza]; however, they know that the Moroccans are in that center in the mountains. After the meeting yesterday, six to eight kids escaped and slept outside the center out of fear to be taken to Tenerife. They returned in the morning and were locked up in the room upstairs for the day; they won't get their pocket money and won't be allowed to go to Las Palmas. The Moroccans were told if they wanted to go to the peninsula [mainland Spain] they would have to prove that they had family there, otherwise they would be transferred to a bad center. Those children who are the most conflictive are chosen for the transfers. Each time they select 25 children to be transferred, among them those who are difficult.[81]

We spoke to some boys who told us that they had run away out of fear of being transferred to La Esperanza."Three weeks ago I escaped with other children; we stayed outside the center for four nights and were sleeping on cardboards; we escaped because we were told we'd be transferred to Tenerife," Mohamad G. told us in Arinaga.[82]

Children may be transferred multiple times and seemingly at random.In one case, a 13-year-old child stayed in five different facilities in little more than one year and was finally placed in an emergency center.[83] Another child who arrived at the age of 13 had been in seven different facilities by the age of 17, spending less than a year in all but one.[84] Children unanimously told us that they were not asked their opinion of an upcoming transfer, and even if they explicitly objected to a transfer they were either simply given notice several days ahead or none at all. Abdurahman A., age 16, Shai L., 17, and Ibrahim K., 17, described the way their transfers took place and how it affected them:

Twelve children were chosen without any information about anything. We were just put into cars and then transferred to La Esperanza.[85]

Life there [where we were originally] was good and it was calm because there weren't too many children. Nobody molested one another. We studied in the center and outside the center. I went to a Spanish school. I was not consulted about the transfer. I was told that I shouldn't be in that center because it was a center for Spanish children only. They just informed me about the transfer.[86]

I was transferred to Los Alanzos center. I was already accustomed to the center [where I stayed before], to the schedule there, and the transfer was disruptive. There was a different schedule and I lost my friends. There were new neighbors. I wasn't asked about the transfer but I was only informed one week earlier.[87]

Children also commonly expressed the belief that where they ended up depended on their national origin. Moroccan children felt they were discriminated against by Spanish authorities. Thirteen-year-old Zubir F. and Abdul Q., age 17, provided typical accounts:

All [sub-Saharan African] children are going to the peninsula [mainland Spain] but not the Moroccans; I heard there's a center in the mountains in Tenerife. The Moroccans are being taken there. When children hear that they will be transferred to Tenerife they escape. All Moroccans from Tenerife have escaped and come back to Las Palmas to complain about that center. The educators threaten to take us to Tenerife; usually they come at four or five in the morning to take the children for the transfer. They ask the child to gather his belongings and then take him to Tenerife. Children who return from Tenerife called their family to send them money so that they can pay for the boat back to Las Palmas.[88]

With the [sub-Saharan Africans], they're always transferring 15 or I don't know how many. Us, never. What fault do we have? We ask how long it will be for us. At first the director said one month, two months. But we're still here [La Esperanza] four months later.[89]

Authorities furthermore fail to take into consideration important aspects of a child's well-being when making transfer decisions. One boy repeatedly requested that he be housed jointly with his brother but has been transferred to another center instead.[90] Although Human Rights Watch raised this matter with the Child Protection Directorate in mid-January 2007, the two brothers had still not been reunited as of early June.[91] Zubir F. told us that he was unable to attend public school after his transfer.[92] Yussef A. reported that the transfer of two children left a younger child unprotected and subsequently subject to violence by his peers: "I used to protect the smaller children with two other boys but the two other boys have been transferred; now we can't protect them anymore."[93]

By taking frequent, random, and possibly punitive transfer decisions, and not upholding his or her right to be heard, it is hard to see how the best interest of the child is being met or indeed given appropriate weight in the process.

The Committee on the Rights of the Child spells out that when choosing alternative care for children deprived of their family environment, "the particular vulnerabilities of such a child, not only having lost connection with his or her family environment, but further finding him or herself outside of his or her country of origin, as well as the child's age and gender, should be taken into account." Furthermore, the committee clarifies that to ensure continuity of care and the best interest of the child, changes in residence should be "limited to instances where such change is in the best interest of the child," that "siblings should be kept together," and that "children must be kept informed of the care arrangements being made for them, and their opinions must be taken into consideration."[94]

The Council of Europe's Committee of Ministers, in its guidelines on children at risk and in care, elaborates that a child's placement "should be subject to periodic review with regard to the child's best interests that should be the primary consideration," and that the "decision taken about the placement of a child and the placement itself should not be subject to discrimination."[95]

V. Legal Status

1. Residency Rights

All foreign children are legal residents while under guardianship of the state. A child is entitled to a temporary residence permit (valid for one year, renewable) nine months after he or she has been referred to protection services and in case family reunification has not been possible[96] (although Spanish law does not rule out a child's repatriation and family reunification after a temporary residence permit has been granted and if the criteria for such a decision are met[97]). Notwithstanding the entitlement, it was rare for the children we interviewed who were eligible for a temporary residence permit to actually have one. (For discussion of official resistance to the granting of temporary residence permits, see Section VIII.4, below.)

Children under guardianship are eligible for Spanish citizenship after two years of guardianship followed by one year of legal residence without interruption.[98] Although a number of children interviewed by Human Rights Watch spent more than three years under public guardianship, none of them was in possession of Spanish citizenship. The government's sub-delegate in Las Palmas confirmed with no further explanation that citizenship has never been granted to an unaccompanied child migrant.[99]

The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (which monitors states' compliance with the Convention on the Rights of the Child) has held that "the ultimate aim in addressing the fate of unaccompanied or separated children is to identify a durable solution that addresses all their protection needs, takes into account the child's view and, wherever possible, leads to overcoming the situation of a child being unaccompanied or separated." Furthermore a durable solution must be sought "for all children who remain in the territory of the host State, whether on the basis of asylum, complementary forms of protection or due to other legal or factual obstacles to removal."[100]

Validity of the temporary residency permit

Staff on different islands and in different centers reported that the temporary residence permit given to a child expires upon a child's 18th birthday. In practice, this turns the young adult into an irregular migrant the day he or she has to leave the protection system. At the same time, there are not sufficient transition programs to support these young adults following release from the protection system.[101] As a result, young adults, upon leaving the child protection system are exposed to increased vulnerability and risk of exploitation and may furthermore be pushed towards illicit and illegal activity.[102] As one center staff member described the situation: "If you have a child who turns 18 you have the sad choice of either kicking the boy out into a life in the streets-or you call the Police to report an irregular migrant."[103]

Although an expired residence permit can be renewed within three months-including one that has expired when a child turned 18-an adult seeking to do so has to give proof of sufficient financial means or has to present a work offer.[104] These requirements are difficult to meet for young persons who were not enrolled in quality education programs during the time they were in state care. Thus, children who had stayed in emergency centers face an additional hurdle in meeting the requirements (deficiencies in education in emergency centers are discussed in Section VII.1, below).

One staff member working in a residential center described prevailing practice:

If permits are issued at all then the expiration date is the child's 18th birthday; he has three months to renew the permit but needs to give proof of sufficient financial means, present a work contract or a guarantor. That is almost impossible. The children are only seen as costs and not as an investment. A change of perspective is needed within institutions in charge.[105]

The Council of Europe's Committee of Ministers specifies in its guiding principles on children at risk and in care that children leaving care should be entitled to "appropriate after-care support in accordance with the aim to ensure the integration of the child in the family and society."[106]

Documentation needed to establish residency rights

As no other formal step is required to establish guardianship, the declaracin de desamparo (Section IV.3, above) is the only official document that records the date when the child is referred to protection services.[107] It thus establishes the date on the basis of which the child's entitlement to a residence permit is calculated.

In order to receive a temporary residence permit a valid identification document is required, which in most cases children do not possess.If they are unable to obtain an identification document through their diplomatic representation they can request a cdula de inscripcin (interim identification document) from the Police.[108]

Spanish law requires that a request for documentation should be made as soon as it is established that a person is undocumented. Human Rights Watch, however, found diverging practices among centers in applying for children's cdulas.[109]

While proceedings to document children in some centers are initiated as early as one or two months after the child's admission, no requests for cdulas are made at Arinaga center. Instead, all children interviewed told us that they were required to produce a national identity document instead, a practice that neither reflects legal requirements nor the best interest of the child.[110] Although Moroccan children may reportedly obtain a passport from their consulate within a few days, this is not the case for children from Senegal whose diplomatic representation takes up to 12 months. As a result, Senegalese children at Arinaga center were desperate to find ways to obtain a national identification document. Seventeen-year-old Modou M. described their efforts:

I have no passport. We save money for our passports but it is very difficult to get them in Senegal. There is a long delay. I was told if I bring my passport they would take care of my residence permit. One of the boys saved 200 and sent it to a friend in Senegal to organize his passport. But his friend just spent the money and he didn't get any passport.[111]

Delays in granting documentation and permits

More generally, the procedure to obtain either an identification document or a residence permit takes several months and is subject to delays, even though there are formal deadlines-three months from the date of application-by which time a cdula and a temporary residence permit should be issued.[112] Several staff members dealing with children's paperwork told us that the process of obtaining documentation and permits was non-transparent and that they did not know the causes for the delays. As noted above, there can apparently be delays also in the issuing of the declaracin de desamparo, which may have knock-on consequences in terms of delaying the child's entitlement to a residence permit.[113]Similarly, one staff member explained to us that he was unable to request a cdula earlier than nine months after the child's admission because authorities do not process the requests before then (in other words, they are apparently applying the same minimum period for entitlement as for a temporary residence permit).[114]

The consequence is extended waiting periods amounting to 15 months or longer. So, if a child is referred to protection services one year or so before his or her 18th birthday, although entitled to a temporary residence permit by the time he or she turns 18, it is unlikely that he or she will leave the child protection system in possession of valid papers. Ibrahim K., age 17, told us, "Yesterday, two children left Playa Honda center after turning 18 without having received their papers. Both spent one-and-a-half years in Spain."[115]

The Child Protection Directorate essentially blamed the government's sub-delegate for the delays, whereas the central government representative asserted that they issue the requested document within one month of receiving an application.[116]

Human Rights Watch observed that none of the children in emergency centers were in possession of a cdula or a residence permit and they were not aware that any of their peers had documents. At least one child interviewed qualified for a residence permit and two more children had spent eight months in the center at the time of our interview. We further received information that at least 23 children who were transferred to the Spanish mainland remained undocumented and without a cdula after they had spent seven months in emergency centers in the Canaries.

Children consistently said that they did not receive sufficient information about their entitlements to documentation, residence permit, and citizenship. They deeply mistrusted staff in charge and they had a sense of wasting their time in the child protection system. Tapha D., age 15, said, "I first believed I would get citizenship by the time I turn 18; now I was told that I will get a residence permit, which is only renewable. I believe less and less in what I will get."[117] Yussef A., age 17, told us, "We are not told the truth; especially not about papers. They [center staff] leave us without any information and without anything."[118]

Lack of accountability

Child protection authorities are mandated to guarantee documentation for children in a timely manner.[119] In practice, though, responsibility for pursuing the children's entitlements to documentation falls on staff working in centers, a responsibility for which they are poorly equipped. The Child Protection Directorate does not oversee the issuance of documentation in compliance with national legislation. One center staff member described the consequences: "In case a child is forgotten, nothing happens. He will simply remain without papers."[120]

As of February 2007, the Child Protection Directorate did not conduct any training on documentation, residence permits, and citizenship for staff working in emergency centers.[121] Although some staff members had significant experience in working with migrant children they lacked expertise on children's entitlements to documentation, permits, citizenship, asylum, or subsidiary protection. As a result, unsupervised practices are in place that violate children's legal entitlements and fail to take into consideration their best interest.

One staff member who works in residential centers summarized the situation as follows:

The biggest problem is the papers. If the cabildo pressed the Child Protection Directorate a bit, the process could be faster. Right now, the law is not being followed. In other autonomous communities lawyers take on these cases and approach the Child Protection Directorate and tell them they are not complying with the law.[122]

The Committee on the Rights of the Child recommends that "unaccompanied and separated children should be provided with their own personal identity documentation as soon as possible" and that officials working with unaccompanied children and dealing with their cases should be trained. Training specifically tailored to the needs and rights of the groups concerned is "equally important for legal representatives, guardians, interpreters and others dealing with separated and unaccompanied children."[123]

By not granting documentation and residence permits in accordance with the law and by pushing a child migrant into an irregular status upon turning 18, authorities refrain from identifying a durable solution for unaccompanied children and they undermine integration efforts designed for and undertaken by the child prior to turning 18. Furthermore, such practice opens the possibility to discriminate against certain groups of children, based on the stereotyping of children into "desirable" and "non-desirable" categories.

Gloria Gutirrez Gonzlez from the Child Protection Directorate plainly told us: "I warned all of the children. If they don't have a project by the age of 18, there will be a plane back to Rabat."[124]

Discretionary denial of residence permits

Information received by Human Rights Watch strongly indicates that the state administration uses reports about children's behavior and their history of conflict with the law to deny children temporary residence permits, which is in violation of Spanish legislation.

Spanish legislation provides that a child's participation in educational and integration programs can be taken into consideration when deciding whether to grant a residence permit, but only if the person failed to obtain a permit before the age of 18.[125] However, as several staff members described, the prevailing practice is to take reports about children's behavior generally into account when granting or denying them documentation and permits:

If a child behaves well, we request a cdula. We then wait for another five to six months to request a residence permit. We have to submit a report [about the child] to the cabildo. If the report is positive, the child might get the permit after three to six months-sometimes it takes longer.[126]

Reports on children compiled in residential centers are not intended for decision making about their immigration status; instead, they are a tool to assess the level and type of care a child requires. Spanish law prohibits personal data from being used for a purpose that is incompatible with the objectives for which it has been gathered, including for decision making that has legal implications or a serious impact, and it provides for compensation for persons negatively affected.[127]

Staff members in residential centers who compile such records include information that is not destined for an immigration decision and may be unfairly prejudicial. For example, files may contain data about negative or disruptive behavior that results from a child's displacement, including trauma from family separation or experiences while migrating, or difficulties in adjusting to abrupt cultural change and a new environment. Staff compiling these records may not readily recognize the causes of such behavior and such causes may furthermore not be adequately treated. One staff member told us that the counseling service available to their center is insufficient because the psychologist offers no individual intervention but only works with groups of children.[128]

Moreover, children may be denied residence permits for attempting to escape from abuse in residential centers where they lack effective mechanisms to protect themselves. An escape from a residential center is considered a very serious violation of center rules according to Canary Islands legislation and may therefore be a factor taken into consideration for the granting of residence permits.[129] We spoke to a number of children whose primary reason to escape from a center was to protect themselves from abuse or from a transfer they considered punitive or discriminatory. If authorities take such behavior into consideration to grant or refuse children their entitlements to documentation and residence permits, they essentially punish these children twice.

Yunus S. and Assane F. both age 17, provided accounts illustrating that children's behavior, including escapes, would be used as a basis to deny them residence permits:

Five boys escaped to go to Santa Cruz at the end of December. The police brought them back. The director was angry and withheld their pocket money. The boys were told that they won't get their papers. Both the director and the educators said so. When I asked about my papers I was told that I won't get anything before I turn 18.[130]

Every day staff prepare a report. They say it will be presented to the president of Spain [sic.]-if we don't behave well, we won't get our papers.[131]

Human Rights Watch also received information that the state administration uses reports about children's history of conflict with the law to deny residence permits. By law, the official records of juvenile offenders are not accessible for such purposes. In contrast to adult migrants, who are required to provide a copy of their criminal records when applying for a residence permit, the records of juvenile offenders (that is, below age 18) are protected by a special registry that can only be accessed by juvenile judges and the Prosecutor's Office in restricted circumstances.[132] By protecting the records of juvenile offenders, Spain adheres to international standards stipulating that "records of juvenile offenders shall be kept strictly confidential and closed to third parties" and that the principal objective of juvenile justice should be to (re)socialise and (re)integrate juvenile offenders.[133]

Although the official records are protected by law, the state administration gains access to the same information compiled in reports of residential centers. These reports, assembled by center staff, would include information on whether a child has come into conflict with the law, and center staff is requested to submit them when applying for a child's residence permit. One center staff member explained to us:

In practice, [a child's] behavior is reported to authorities. If [a child] commits a crime [he] doesn't get a residence permit. But in Spain such records should be cancelled. It is an illegal practice. When a child turns 18 all files [about a child] are sent to the cabildo. When an adult applies [for a residence permit] his record as a child is taken into account.[134]

The government's sub-delegate in Las Palmas, who takes decisions on requests for residence permits, told Human Rights Watch that criminal behavior of children is indeed taken into account in the granting or refusal of a residence permit, including if the person applies for a permit after turning 18.[135]

The Convention on the Rights of the Child provides that children shall not be subject to arbitrary or unlawful interference with their privacy, family, home or correspondence.[136] The Committee on the Rights of the Child further specifies that "care must be taken that information sought and legitimately shared for one purpose is not inappropriately used for that of another."[137]

2. Work Permit

Children from age 16 who are in possession of valid residence and work permits are entitled to work.[138] The granting of work permits to foreigners is generally subject to considerations of the labor market for Spanish citizens. Foreign children under guardianship and in possession of a residence permit are exempted from such considerations if the guardian considers that the professional activity contributes to the child's social integration. The need for a work permit can be waived altogether for children under guardianship, upon request by the guardian.[139] Thus, Spanish legislation grants a range of exceptions for migrant children to access the regular labor market. Authorities in charge, however, fail to apply the law in the child's best interest and disregard that children in several instances could greatly benefit from the application of these provisions.

Despite children's desire to enter the regular labor market, none of the children Human Rights Watch had spoken to was in possession of a work permit or was participating in a legal, gainful activity. On the contrary, two children interviewed were not able to participate in the practical segment of their vocational training due to the lack of permits (see below, Section VII.1), and one 17-year-old, Shai L., reported that he worked for three months in a vegetable plantation but without the necessary work permit.[140]

The length of procedure to obtain a work permit may put children's prospect of securing a job at risk. Seventeen-year-old Ibrahim K. told us that delay in securing permits was a risk to a job offer as a waiter: