Summary

South Sudan’s National Security Service (NSS) was established in 2011, after the country gained independence. The 2011 Transitional Constitution of the Republic of South Sudan, mandates the NSS to collect information, conduct analysis, and advise relevant authorities. But since its establishment, the NSS has gone much further than merely collecting information. Within months of its establishment, its agents were arresting and imprisoning journalists, government critics and others, and conducting physical and telephonic surveillance. Today, it has become one of the government’s most important tools of repression.

Based on interviews with 48 former detainees and 37 others including policy analysts, activists, former military, security, and intelligence personnel and family members of people detained by the NSS between 2014 and 2020, this report documents serious human rights violations by the NSS in South Sudan, including torture and other ill-treatment of detainees, arbitrary arrests, unlawful detentions, unlawful killings, enforced disappearances, forced returns and violations of privacy rights. The report describes obstacles to accountability for these abuses, including denial of due process for detainees, the lack of any meaningful judicial or legislative oversight of the agency and legal immunities for NSS agents.

With the outbreak of civil war in December 2013 and a resurgence of fighting in July 2016, the NSS engaged in extensive crackdowns targeting people who are deemed to be anti-government. They also used ethnicity to profile targets with the assumption that people from certain ethnicity belong to armed or political opposition groups. It has targeted government critics, suspected opponents and rebels, aid workers, human rights defenders, businessmen, journalists and students, and routinely used violence and intimidation, including threats, beatings, and surveillance against them.

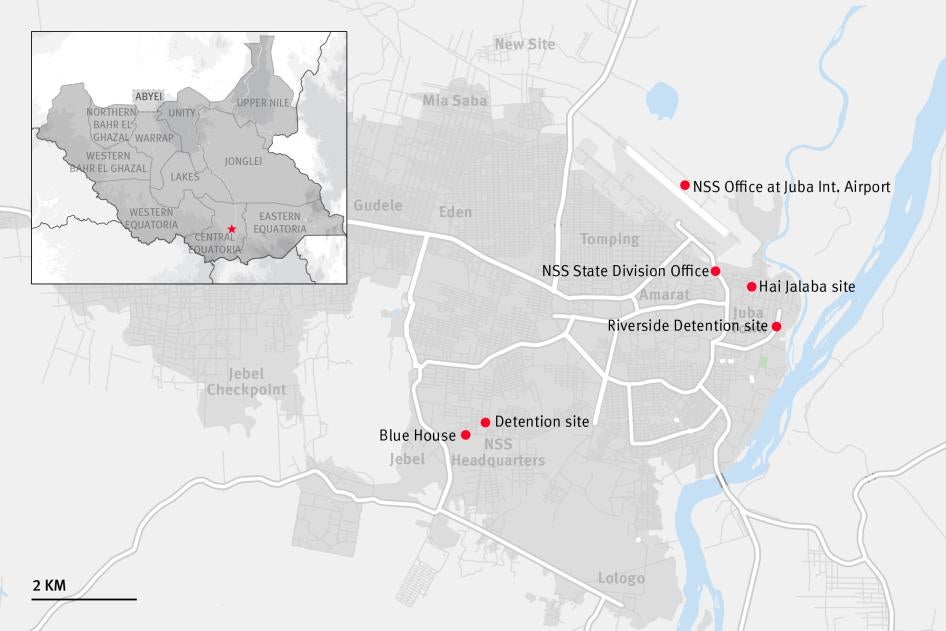

The NSS has three main facilities in Juba that are considered de facto, “official” Blue House, Riverside, and Hai Jalaba – but also uses “unauthorized” places such as residential homes as detention sites. None of these places of detention are legally recognized.

Detainees interviewed for this report, experienced, or witnessed beatings, being pierced with needles, having melted hot plastic dripped on them, being hung upside down from a rope, shocked with electricity, and raped. The NSS held detainees in prolonged, arbitrary, and incommunicado detention, often in congested cells with inadequate access to food, water, and medical care. Other authorities cooperate freely with the NSS, even as they commit these abuses. For example, detainees have been transferred to NSS custody from military and police facilities, and vice versa-without relevant paperwork being completed, or due process being followed.

The NSS has also detained people with disabilities, children, and pregnant and lactating women. Many were released without ever being interrogated, charged, or presented in court.

The NSS has extended its reach into neighboring countries. Its agents have harassed, intimidated, and abducted people in Kenya and Uganda whom they deemed to oppose the government, sometimes with the tacit support of authorities from these countries. This has created a climate of fear and suspicion among the diaspora in neighboring countries, in effect stifling criticism of South Sudan’s government even outside the country.

It has acquired and deployed intrusive surveillance tools, demanding that telecommunications companies’ hand over user data. Its agents have also carried out the functions of the South Sudan National Police Service, taking over law and order duties, including arresting and detaining criminals and maintaining law and order in major towns affected by fighting.

This expansion of NSS’s role and mandate has not been accidental. The service is supervised by the president and under his watch the NSS has evolved into an agency that operates outside the law and is used to maintain the government’s grip on power.

Human Rights Watch research indicates that efforts to hold NSS officials to account have been too few and opaque. Although South Sudanese law provides victims a right to a remedy, there is in practice little recourse for victims of such abuses.

Human Rights Watch calls on the government of South Sudan to end NSS’s de facto powers of detention and close all places of detention used by the NSS. They should immediately release all detainees in NSS custody or bring them before a court of law to be charged with a cognizable offense and either released on bail or remanded to the custody of South Sudan’s National Police Service in accordance with the law. They should ensure that all persons in NSS detention who are brought before a court enjoy their full due process rights, including the rights to a lawyer of their choice, to challenge the detention and charges, and are guaranteed a fair trial.

The Revitalized Transitional National Legislature of South Sudan, once established, should amend the 2014 National Security Service Act and exclude its powers of detention from its mandate and limit it to intelligence gathering, analysis and provision of advice to relevant authorities, consistent with the country’s constitution. South Sudanese authorities should also ensure that former NSS detainees and victims of NSS abuses receive justice and redress, including provision of physical and mental health services.

The NSS’s well-documented record of serious crimes warrants a much stronger response from the international community. South Sudan’s partners, including the African Union, neighboring countries, the United States, Norway, and the United Kingdom should privately and publicly call on the South Sudanese authorities to end NSS abuses, reform it, and conduct credible and independent investigations into all allegations of abuse.

Glossary

Blue House: Headquarters of the National Security Service in Juba and office of the Minister for National Security, which includes the main NSS detention site

CPA: Comprehensive Peace Agreement, which ended Sudan’s long civil war in 2005

CTSAMM: Ceasefire and Transitional Security Arrangements Monitoring Mechanism

EACJ: East African Court of Justice

FDs: Former Detainees, a group of South Sudanese political figures accused of plotting a coup in the lead up to fighting in December 2013

GSB: General Security Bureau, a branch of the NSS that deals with countering external/foreign threats

IGAD: Intergovernmental Authority on Development

ISB: Internal Security Bureau, a section in the NSS that deals with countering internal/domestic threats.

MI: Military Intelligence

NISS: National Intelligence and Security Service (Sudan) renamed as General Intelligence Services (GIS) in July 2019

NSS: National Security Service (South Sudan)

SPLM/A: Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army

SPLM/A-IO: Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army-in-Opposition

SSHRC: South Sudan Human Rights Commission, a national institution with the constitutional mandate to promote and protect of the human rights

SSPDF: South Sudan People’s Defence Forces, the renamed army of South Sudan

TCSS: Transitional Constitution of the Republic of South Sudan of 2011

Recommendations

Immediate Recommendations

To the President of the Republic of South Sudan

- Immediately close all National Security Service detention centers, prohibit NSS from operating detention centers, and ensure NSS releases all detainees in its custody or immediately brings them before an independent court to be charged with a cognizable crime. Instruct the NSS director generals to publish a list of all those in its detention on the date of its order, including the date and location or locations of their detention and the grounds for their detention. If ordered by the court, people on pretrial detention should only be held in official places of detention run by the National Prisons Service.

- Issue public orders warning the NSS immediately to stop carrying out detentions, for which it has no legal basis, and to immediately stop torture, and other forms of cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment and punishment of detainees.

- Ensure a prompt, transparent, and impartial investigation into all allegations of NSS abuse including all allegations of torture and ill-treatment and ensure that all personnel implicated in abuses, regardless of rank, are appropriately disciplined or prosecuted.

- Ensure findings of investigations into NSS abuses are made public and that victims of torture and other abuses have access to redress. Ensure these victims are provided with compensation and receive appropriate psychosocial support and access to health care.

To the Director Generals of the National Security Service and the Minister for National Security

- Immediately cease carrying out new arrests or detentions.

- Close all NSS places of detention and either release detainees or liaise with the police and other criminal justice actors to immediately bring them before an independent court to be charged with a cognizable crime and transferred to the custody of the National Prisons service. All detainees brought before a judge should be afforded all due process rights.

- Immediately cease the use of all forms of surveillance technologies until a legal and policy framework is put in place to regulate such practices and guarantee that such technologies can only be used in compliance with international human rights law, including the requirements of legality, necessity and proportionality.

Pending closure of NSS detention facilities:

- Ensure that all detainees enjoy full due process rights, including access to legal counsel as required under the constitution. Ensure they have access to legal counsel at any time pending their release or appearance before a judge.

- Collaborate with the Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Interior and the Director of the Prisons Service to publish up-to-date lists of all places that have been and are used for detention by the NSS in a form that is readily accessible to lawyers and members of the public. Establish and maintain a central register of all detainees held in these facilities to ensure the whereabouts of all detainees can be traced.

- Facilitate inspections by independent human rights monitors and appropriate humanitarian agencies to all authorized or unauthorized NSS places of detention, ensuring that they can have access to all detainees.

- Ensure all detainees in NSS custody have regular access to family, lawyers and other visitors.

- Ensure detainees have adequate access to medical care including that detainees are examined by an independent qualified doctors and mental health professionals and monitor the quality of medical care being provided.

- Screen all detainees for all types of disabilities. Provide reasonable accommodations and respond appropriately to the needs of detainees with disabilities, including physical, mental, sensory or intellectual. Ensure detainees with disabilities have adequate access to facilities and support needed for self-care, personal hygiene and mental health.

To the National Constitutional Amendment Committee

- Amend the National Security Service Act and ensure institutional and legislative reform of the NSS to limit its role to intelligence gathering and evidence analysis in accordance with the Transitional Constitution of South Sudan; remove its powers of search, detention and seizure.

- Amend the National Security Service Act limiting the NSS’s powers to collect, use, analyze or retain communications and personal data to situations that are justified as strictly necessary and proportionate to fulfill a legitimate national security aim. Ensure appropriate safeguards to prevent abuse of these powers, including exercising them outside of the situations provided for in law.

To the Reconstituted Transitional National Legislative Assembly

- Clearly gazette places of detention and ensure all unauthorized places of detention are closed, prohibit NSS from running detention centers and ensure NSS release all detainees to police and that they are brought before a judge to be charged with a cognizable offence.

- Using the legislature’s powers of oversight provided in the Constitution and the National Security Service Act, investigate all allegations of unlawful detention, torture, or ill-treatment by the NSS including those described in this report. The investigation should request access to any place of detention still used by NSS at the time of the investigation, interview detainees and former detainees in a confidential setting, report publicly on its findings including the government’s responses and recommend ways to end the abuses.

- Ensure amendments to the National Security Service Act drafted by the National Constitutional Amendment Committee provide institutional and legislative reform of the NSS to limit its role to intelligence gathering and evidence analysis in accordance with the Transitional Constitution of South Sudan; remove its powers of search, detention and seizure.

- Amend the National Security Service Act limiting the NSS’s powers to collect, use, analyze or retain communications and personal data to situations that are justified as strictly necessary and proportionate to fulfill a legitimate national security aim. Ensure appropriate safeguards to prevent abuse of these powers, including exercising them outside of the situations provided for in law.

- Enact laws requiring an independent competent judicial authority to issue a written order before the NSS or other government agencies are allowed conduct data collection or any other surveillance activity on a specific target or targets; the relevant judicial authority should only approve requests for surveillance activities which, at a minimum, have a clear legal basis and for which the government has established they are necessary and proportionate to fulfill a legitimate aim.

- Call on the president and the minister for justice to sign the Memorandum of Understanding with the AU and pass relevant legislation on the Hybrid court for South Sudan, the Commission for Truth, Healing and Reconciliation and the Compensation and Reparations Authority.

To South Sudan’s National Commission for Human Rights

- Publicly advocate for the closure of NSS detention facilities and release of all detainees or for them to be brought before a judge and charged with full due process rights.

- Pending closure of NSS facilities, request unfettered access to NSS facilities and undertake regular monitoring visits to ensure that detainees are handed over to the police, charged or released.

- Investigate allegations of enforced disappearances, unlawful and arbitrary detention, and torture in NSS facilities; report publicly on the findings and abuses; publicly condemn abuses and recommend actions for redress.

- Urge the government and parliament to ratify the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance.

- Urge reforms that would limit the role of the NSS to intelligence gathering and evidence analysis in accordance with the Transitional Constitution of the Republic of South Sudan.

- Advocate for appropriate limitations to the NSS powers of surveillance including safeguards to limit the nature, scope, and duration of surveillance as outlined above.

To South Sudan’s Regional and International Partners

- Call on South Sudanese authorities to immediately implement the recommendations in this report, including shutting down NSS places of detention; directing security personnel to stop unlawful detentions; stop ill-treatment and torture of detainees; and investigate all allegations of abuse of detainees and hold those responsible to account.

- Ensure South Sudanese authorities launch effective independent and transparent investigations into the role of the Minister of Interior, the director generals of the NSS in facilitating abuses by the service.

Medium Term Recommendations

To President of the Republic of South Sudan

- Offer a standing invitation to visit South Sudan to relevant United Nations mechanisms including the special rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, the special rapporteur on the right to privacy, the special rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, and the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detentions; and to the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights’ special mechanisms including, the special rapporteur on prisons, conditions of detention and policing in Africa, the Committee on the Prevention of Torture in Africa and the Working Group on Death Penalty, Extra-judicial, Summary or Arbitrary Killings and Enforced Disappearances in Africa.

- Promptly establish the accountability mechanisms envisioned under the terms of the 2015 and 2018 peace agreements-the hybrid court, the Commission for Truth, Reconciliation and Healing, Compensation and Reparations Authority- to facilitate redress for conflict related abuses that may amount to war crimes and crime against humanity including the arbitrary detentions, torture, unlawful killings, and enforced disappearances committed by security forces including the NSS.

To the Minister for National Security, Director Generals of the National Security Service, the Minister for Justice and Minister for Interior and the Director of the Prisons Service

- Ensure findings of all allegations of abuse of detainees are made public in a timely manner and hold those responsible to account in transparent civilian processes.

- Ensure that NSS personnel and members of NSS oversight mechanisms receive appropriate training that adhere to international human rights standards.

To South Sudan’s Regional and International Partners

- Call on South Sudanese authorities to implement, immediately, the recommendations in this report, most urgently shutting down NSS places of detention; directing security personnel to stop unlawful detentions; stop ill-treatment and torture of detainees; and investigate all allegations of abuse of detainees and hold those responsible to account.

- Develop or support programs to respond appropriately to the support needs of former detainees including mental health services.

- Impose an immediate moratorium on the export, sale, transfer, use or servicing of surveillance technologies to South Sudan until a human rights-compliant safeguards regime is in place.

- Press authorities to ensure establishment of the Hybrid Court for South Sudan, the Commission for Truth Reconciliation and Healing and the Compensation and Reparations Authority envisioned in the peace agreements; Ensure adequate political, technical, and financial support to the transitional justice mechanisms provided for by the 2018 peace agreement.

- Under the principle of universal jurisdiction and in accordance with national laws, investigate and prosecute South Sudanese officials accused of abuses including torture, sexual violence and other ill treatment, enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings.

To the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights, UN Work Group on Arbitrary Detention, and the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment

- Request an invitation from South Sudan to carry out a fact finding visit to investigate torture and arbitrary detentions of people in NSS custody.

- Prepare a subsequent report and refer the issue of the NSS violations to the Human Rights Council and to the AU Peace and Security Council (AU PSC) in accordance with Article 19 of the Protocol relating to the establishment of the AU PSC.

- Call on South Sudan to conduct credible, effective and impartial investigations into NSS abuses including those documented in this report, make findings public and ensure all officials responsible for abuses regardless of rank are held accountable.

- Urge South Sudan to ratify the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance.

- Urge South Sudanese authorities to sign the memorandum of understanding with the AU, and to pass relevant legislation on the Hybrid Court for South Sudan, on the Commission for Truth Reconciliation and Healing and the Compensation and Reparations Authority.

Methodology

This report is based on research conducted between 2018-2020 in South Sudan, Uganda, and Kenya. Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed 48 former detainees, including 4 women, held by National Security Service (NSS) between 2014-2020 at the Blue House, Riverside and Hai Jalaba sites in Juba. Researchers also interviewed 37 others, including South Sudanese human rights activists in the country and in exile, journalists, political analysts, opposition party members, civil servants and former military, security and intelligence personnel, family members of victims of NSS abuses, representatives of domestic and international non-governmental organizations, diplomats and United Nations officials. Except for two NSS officers, all former detainees interviewed for this report were civilians.

This report also draws on research published by Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, South Sudan’s Human Rights Commission, the UN Mission in South Sudan, the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights’ (OHCHR) Commission on Human Rights in South Sudan, the UN Panel of Experts on South Sudan and other international and domestic NGOs.

Interviews were conducted in person in Juba, South Sudan; Nairobi, Kenya; Kampala, Uganda; in locations deemed private and secure by researchers and interviewees as well as over the phone and on secure messaging applications. Interviews were conducted in English, Arabic, Bari, Thuuk Naath (Nuer), Thuuk Muonyjang (Dinka) and other local languages with the aid of interpreters as needed. Interviewees were sometimes visibly distressed and emotional as they recounted their experiences. Researchers took care to avoid re-traumatizing them, including by explaining the extent and line of questioning involved before the interview commenced and their right to stop the interview at any point, avoided speaking to detainees immediately after their release and to those who may have been interviewed multiple times by other organizations, researchers or journalists.

Individuals interviewed for this report described being targeted for arrest based on perceived political or ethnic affiliation. They spoke of being targeted for their criticism of the government or specific officials, for their journalistic or human rights work or trumped up accusations for the exercise of civil and political rights. Others were accused of being rebels or supporting rebel groups, of corruption and fraud and murder and other criminal offences that fall under the jurisdiction of the national police service. In some cases, their arrest and detention were preceded by physical and telephonic surveillance undertaken by the NSS. Such surveillance continued even after detainees were released and, in some cases, prompted them to flee the country fearing re-arrest and other abuses.

Former detainees also spoke of being detained together with NSS, army and police officers accused of various crimes including murder, desertion, fraud and other disciplinary and administrative issues relevant to their units. Most of these officers were also detained for prolonged periods of time without charge or trial, in violation of their due process rights.

Many of the witnesses and victims of NSS abuses who spoke with Human Rights Watch expressed fear about the risk of reprisals and retaliation by the state, including against their relatives. For that reason, names and other identifying information of many of the victims and witnesses have been withheld to ensure their safety and that of their families. Details in some testimonies have been withheld to protect the identity of interviewees.

Researchers explained to each interviewee the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, the way in which the information would be used and the fact that no compensation would be provided.

In December 2018, March, August and December 2019 and January 2020, Human Rights Watch requested, verbally and in writing, meetings with two of the top officials of the NSS, the Director General of the Internal Security Bureau and the Director of Legal Administration. These requests all went un-answered.

On July 1, Human Rights Watch sent the summary of findings of this report to Minister for Interior, Obuto Mamur Mete, the Director General of the Internal Security Service, Akol Koor Kuc, the Director General of the External Security Bureau, Thomas Duoth Guet and the Director of Legal Administration, Jalpan Obac, requesting response from the government. At time of writing, the government has not responded. Copies of the letters are included in the appendices section.

On August 31, Human Rights Watch shared similar summary of findings and request for comments with Kenyan authorities - specifically the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Interior, the Inspector General of the National Police Service - and with Ugandan authorities specifically the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Department of Refugee Affairs, Office of the Prime Minister and the Ministry of Internal Affairs. At time of writing, only the National Police Service of Kenya had responded, a copy of which is included in the appendices section.

This report identifies two broad sets of recommendations: one immediate, the other medium term. The former represents pressing measures South Sudanese authorities and other stakeholders should take to remedy the accountability deficit and weaknesses in legislative and judicial oversight of the NSS, while the later outlines, equally important steps and reforms that the government and its international partners should act upon in the next six months to one year.

I. Background

Sudan’s National Intelligence and Security Services in the South

Prior to South Sudan’s independence in 2011, Sudan’s National Intelligence and Security Services operated both in the north and south. The security service under Jafaar Nimeiri’s government (1969-1985) was particularly brutal. [1] Under former Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir, the National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS) was no different; officers focused on repressing political dissent— including sympathizers of southern rebel groups such as the Anyanya II and Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A)—and were known for unlawful arrests, torture and enforced disappearance of government opponents in secret detention sites all over the country.[2]

The rebel group SPLA on the other hand, ran a separate government in areas outside the control of the national government and had its own intelligence unit.[3] The SPLM/A was also accused of abuses against civilians in these areas including ethnic killings, kidnappings, summary executions and forced recruitment and its intelligence unit, accused of throttling independent and liberal political opinion.[4]

In 1995, the SPLM/A renamed the intelligence unit the “General Intelligence Service” and divided it into two branches: a “military intelligence unit” and a “public service organ.” The latter dealt with civilian issues.[5] After the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) was signed in 2005, ending the long Sudanese civil war and paving the way for the independence of South Sudan in 2011, the NISS continued to operate in both the north and the south of the country with deputies heading each branch and reporting to one director general in Khartoum. The southern division began to operate more autonomously during this “CPA period” and was informally spying on its northern counterpart in the lead up to independence.[6]

In 2007, the southern government created the “special branch,” a secret intelligence unit exclusively comprising southerners and separate from the NISS, in order to counter potential spies from the north within NISS and in informal civilian spy networks.[7] In 2011, the southern division of the NISS, “special branch” and the “public service organ” were all dissolved. Their members were absorbed into the newly minted National Security Service (NSS) and the army’s military intelligence (MI). [8]

The National Security Service in South Sudan

South Sudan gained independence on July 9, 2011. Its first transitional constitution envisioned a National Security Service (NSS) with a mandate to gather intelligence and advise relevant government institutions.[9] The constitution provides that the NSS be comprised of two operational organs: the General Intelligence Bureau, GSB, also known as external security, and the Internal Security Bureau (ISB).[10] The NSS, which is under the Ministry of National Security, reports directly to the president and is funded through the office of the president.[11] The budget and operations of the office of the president are not publicly audited, ostensibly for national security reasons, therefore limiting transparency and parliamentary oversight in respect of the agency’s operations.[12] Civilian oversight is provided through parliament which conducts an annual evaluation of the performance of the NSS.[13] However this mechanism is weak in practical terms, as the parliament is dominated by the ruling SPLM party.[14] Both the ISB and GSB director generals, appointed by President Kiir in 2011, served under him in the SPLA.[15]

Ineffective oversight combined with broad powers means the NSS is subject to little if any accountability and the structure has created an intelligence service that is subject to extreme political interference.

The ISB, led by Lt. Gen. Akol Koor Kuc, deals with internal threats to national security. Lt. Gen. Akol oversees operations including intelligence gathering, combat, cyber-operations, and detention facilities - both documented and secret sites - across the country.[16]

The GSB role is to counter external threats and insurgencies. Most of its members are posted in foreign countries including in South Sudanese embassies and consulates and thought to work clandestinely much like other intelligence agencies around the world.[17] The Director General of the GSB, since 2011, is Lt. Gen. Thomas Duoth Guet.[18]

The Transitional Constitution required the new government to develop a national security strategy. A committee was appointed by the then Minister of Interior and following extensive consultations, produced a draft policy in October 2013. [19] The draft envisioned a professionalized NSS whose role was intelligence-gathering and analysis as stipulated by the constitution. [20] Support for the draft was split between those who wanted a progressive agency with limited powers and those who advocated for an agency modelled on the NISS.[21] The draft was never adopted. Instead, when civil war broke out in December 2013, the National Security Service Act of 2014, which gave the NSS extensive policing, was adopted.

The 2014 National Security Service Act (NSS Act)

Broad and unqualified powers

The 2011 Transitional Constitution provides in section 159 that the NSS should focus on “information gathering, analysis and advice to the relevant authorities.” The constitution therefore envisions the NSS’s role to be confined to classic intelligence activities and does not vest the NSS with police powers. The 2014 National Security Service Act (NSS Act) modelled after the National Security Act (2010) of Sudan, gives the agency extensive powers of arrest, detention, surveillance, search, and seizure, falling outside the constitutional mandate.[22]

The power to use force, though not explicitly listed in the Act, is implied in the granting of other police powers, and also falls outside the NSS’s constitutional mandate. The Act is also vague on key aspects which give the agency further scope for interpretation at their whim. [23]

It also provides no clarity about the circumstances under which these powers can be exercised.[24] Section 7 of the Act grants NSS powers in relation to a broad and vague definition of crimes and offences against the state.[25] Such broad offences, as demonstrated in later sections of this report, have been used to violate freedom of expression, assembly and association, for instance, by unduly restricting or preventing peaceful exercise of political opposition, or public criticism of state policy and actions. The descriptive definition of crimes against the state in particular runs afoul of the principle of legality which requires crimes to be sufficiently precise so that individuals know what conduct is unlawful and the possible consequences of such conduct.

Lack of Judicial and Custodial Safeguards

The NSS has extensively used its powers of arrest and detention, which is the source of most human rights violations described in this report. Though the Act provides that individuals should be brought before a magistrate or judge “as soon as is reasonably practicable within 24 hours”, even if investigations are incomplete, it fails to specify that the individual must physically appear in court and be allowed to challenge the legality of their detention and doesn’t bar extraordinary circumstances that make it impossible to do so.[26] It also does not indicate that the purpose of this hearing would be for the court to decide on the lawfulness and necessity of continued detention, and to either remand the accused person in an ordinary prison or order his or her release.

The Act does not explicitly state that the 2008 Code of Criminal Procedure will apply to all court proceedings against those in the custody of NSS, or what role the NSS plays in investigations and prosecutions stage vis-à-vis the public attorneys at the Ministry of Justice. The NSS can apply for a warrant from the high court when there are “reasonable grounds to believe that a warrant is required to enable the service to perform any of its functions.”[27] Human Rights Watch did not document in this report any case when the NSS used a warrant to arrest an individual or apply for detention.

Although section 13 gives the NSS powers to detain, it fails to specify permissible places of detention for the NSS. Section 67 makes it an offence for an NSS officer who “refuses to deliver to the official authority any member or person arrested or detained or in custody under his or her command” or “unlawfully releases any member or person under his or her guard” but does not spell out who the official authority to whom NSS can hand over detainees to is. However, the Act provides that the Minister of National Security may issue regulations governing the treatment of detainees.[28] Human Rights Watch is unaware of the existence of such regulations and the NSS did not respond to Human Rights Watch’s request for comment on this matter.[29]

Human Rights Watch is also unaware of a law or policy that regulates how the NSS and the police — which under the 2009 Police Service Act is tasked with arrest, investigation, and detention of suspects — can interact on areas of common ground or how the NSS fits into the criminal justice system. [30] Lawyers told Human Rights Watch that the expectation is that even when the NSS makes arrests, civilian suspects should be handed over to the police service for investigation and judicial oversight sought for any pretrial detention.[31]

Weak oversight and accountability mechanisms

The legal department of the NSS is set up by the Act to check excess of power, “ensure that cases being handled by the service are expedited and promptly referred to court” and advise the agency on matters of constitutionalism, human rights and general legal matters. [32] Given the prolonged and arbitrary detentions and other abuses experienced by detainees between 2014-2020, as documented in this report, it is apparent that the legal department is not effectively discharging these functions.

NSS officers enjoy legal immunities. Section 49 of the Act ensures that that no criminal or civil proceedings can be initiated against any member of the service by giving the Minister, in case of the officers above the rank of 2nd Lt., or the Director General in case of other ranks discretionary powers to decide whether to allow investigations or prosecutions, suspend officers or take other disciplinary actions.[33] The provision has placed an undue burden on civilian victims of NSS abuses to provide sufficient evidence for the lifting of such immunities. This has erected an unsurmountable barrier preventing victims of NSS abuses from getting relief in court or ensuring offending officers are held accountable for their actions.

While sections 56-76 of the NSS Act provide that NSS officers may be prosecuted and sanctioned, including with imprisonment, for a number of offences such as abuse of power, indiscipline and improper conduct, and criminal use of force among others, Human Rights Watch is not aware of any NSS officer imprisoned for abusing their powers.

Section 20 of the NSS Act provides for an internal accountability mechanism through the establishment of a complaints board. The complaints board can accept complaints about the procedural actions of the NSS from both the public and NSS agents but lacks independence. The head of the legal department of the NSS is a member of the complaints board, which creates a clear, incompatible conflict of interest between being an employee of the NSS responsible for providing legal advice about the service and holding the NSS to account.

Section 77 provides for two service tribunals where members of the NSS can be charged for summary and non-summary offences including crimes against the state.[34] When civilians are accused of crimes against the state, the ministry of justice is supposed to provide guidance on how and where the case is heard.[35] The establishment of separate mechanisms by the NSS to hear criminal cases against its officers, where the high court would have jurisdiction, creates a parallel legal system where the NSS can cherry pick what option works best for them. This also places accused civilians outside the protection of the law. As discussed in later sections of this report, these processes are opaque (there is very little public information about them) and ultimately allow the NSS to circumvent the civilian justice system and any form of accountability.

The NSS Since South Sudan’s Civil War

In December 2013, violence broke out in Juba following a political deadlock between President Salva Kiir, a Dinka, and his deputy, Riek Machar, a Nuer, and other members of the ruling SPLM. When this political dispute turned violent on December 15, the army and security forces split along ethnic lines and within hours, the mainly Dinka government troops carried out large-scale targeted killings, detentions, and torture of mainly Nuer civilians around Juba, the capital.[36] In the following months, fighting spread to Bor, Bentiu, Malakal, and across the Greater Upper Nile region, with civilians targeted by all sides based on their ethnicity and perceived political allegiance. In late 2015, after the parties signed a peace deal in August, the conflict spread to the Equatoria region as new political and rebel groups formed with varied grievances, while government forces carried out deadly counterinsurgency campaigns in regions south and west of the capital.[37]

As the war escalated, so did the crackdown on dissenting voices and those deemed to support rebel movements either due to their ethnicity or political statements. [38] The government, through the NSS and army, acquired key military and surveillance equipment in 2014 from Israel including wiretapping devices and aerial drones and cameras, further enabling this abusive targeting in country. The NSS also expanded its reach into neighboring countries like Kenya and Uganda, targeting government critics and perceived opponents in neighboring countries.

The NSS also became better resourced, financially and militarily, as President Kiir grew distrustful of the army.[39] The NSS, contrary to its mandate, effectively evolved into a law enforcement agency arresting suspects for criminal offences and maintaining law and order in major towns like Yei and Wau impacted by fighting. In addition, NSS agents have been deployed in combat and counter-insurgency operations alongside the army, South Sudan People’s Defense Forces (SSPDF, formerly the Sudan People’s Liberation Army, SPLA). [40]

II. Abuses in NSS Detention Facilities

Since the outbreak of South Sudan’s conflict in 2013, the NSS has harassed, arbitrarily arrested and detained scores of people based on their real or perceived political affiliations and views. These include civil society activists, journalists, human rights defenders, and members of political opposition groups. NSS agents also targeted foreigners and aid workers on accusations of fraud, immigration offences or petty offences. Others, including civilians and members of security forces, were detained at the behest of senior government or security officials with personal grudges.

Although nominally governed by the National Security Service Act, the NSS effectively operates outside of the law and conducts its business without proper legal authority. This means, for example, that NSS agents hold detainees in sites - both known and secret - which are not designated as detention facilities under the law. They do not conduct arrests based on warrants or court orders, but on their own initiative, and routinely hold detainees for long periods – even years –without charge and without access to lawyers or visitors. Detainees are rarely brought before a court to be charged. Detention periods lasted from hours to as long as four years, in violation of South Sudanese and international law, and specifically South Sudan’s obligations under multiple human rights treaties.

This section documents the range of abuses and harsh conditions faced by individuals in NSS custody and the lasting impact these abuses have on detainees’ lives.

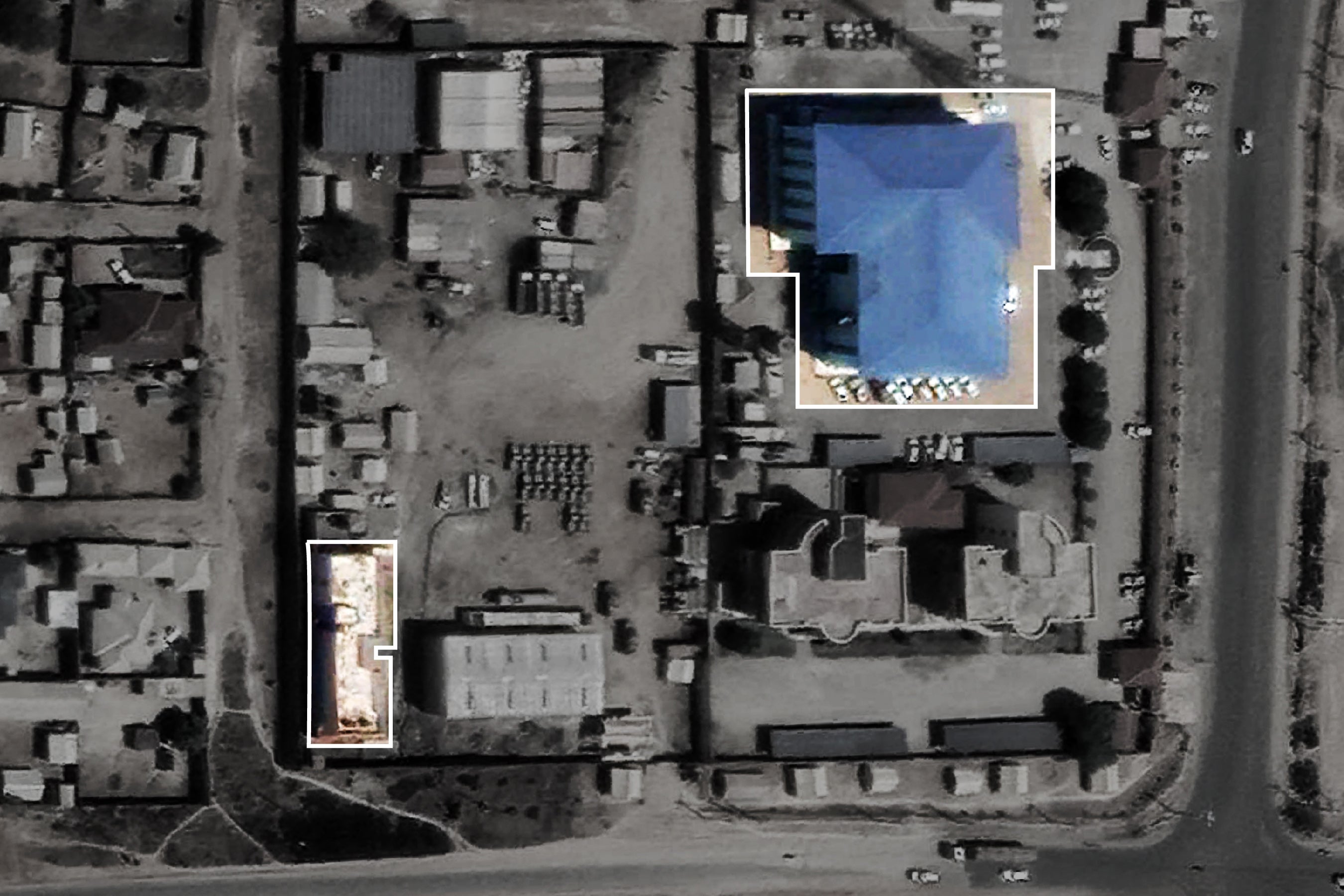

NSS Detention Sites in JubaAlthough the NSS Act gives the agency powers of detention, it does not specify locations where NSS detainees can be held. The ISB holds people at the NSS headquarters, commonly known as the Blue House, and at Riverside, a site near the Nile river in downtown Juba, also known as NSS operations division. It also detained individuals at a security forces’ training facility at Luri, not far from Juba and the State security offices, Central Equatoria state near the Hai Jalaba site. They also have at least one detention site in each of the 10 states.[41] None of these sites is authorized in law as a detention facility. In addition, NSS runs an unknown number of detention sites in unmarked, unofficial “safe houses”. The ISB’s reputation is worse than its counterpart, the GSB. The GSB holds people at an office in the Hai Jalaba neighborhood. As public information about these sites is limited and South Sudanese did not respond to Human Rights Watch inquiries, Human Rights Watch has assembled information about the three main sites from interviews with former detainees held at the sites and former intelligence and security officials. Hai Jalaba SiteHai Jalaba site, near the Egyptian clinic in Atlabara close to Juba town, is under the authority of the GSB. Former detainees held there between 2015-2019 told Human Rights Watch that the site is an office compound with cells in offices but also in shipping containers and residential houses in another section. The site is mostly used to detain foreigners, on allegations such as spying, forgery, fraud and embezzlement or other offences deemed to violate South Sudan’s national security.[42] The facility is also adjacent to the state security offices of Central Equatoria state which are run by the ISB. RiversideThe Riverside site is located within the NSS operations division compound, behind police and immigration offices in downtown Juba. Former detainees with whom Human Rights Watch spoke described the site as “one big cell with four other cells or sections inside it with capacity to hold 20-35 people at a time.”[43] They said it has a reception area or a verandah used to detain NSS officers held for disciplinary offences and where new detainees were sometimes interrogated and tortured;[44] a large cell used to hold multiple detainees, packed close together; five solitary confinement cells; and a dark room where interrogations and torture would take place but they said was also sometimes used to store weapons.[45] The Blue HouseThe Blue House is the headquarters of the NSS, is an imposing building on the Juba-Yei road in Juba’s Jebel neighborhood. Its main detention site is a two-story building located behind the main office building, opened in November 2015. Prior to the completion of this facility, detainees were held in offices and the basement of the Blue House building itself or at the Riverside facility. Detainees interviewed for this report who were held at the Blue House between 2014 and 2020, told Human Rights Watch that the upper and lower sections of the site consist of 10 cells measuring 4x4 meters with capacity to hold at least 10 detainees at a time and six cells for solitary confinement commonly called “zanzana” (meaning cell for one person in Arabic) measuring 1x1 meter. The upper section of the site was used to hold high level detainees such as political activists and opposition members, referred to as “VIPs.” The site was designed to hold male detainees. However, sources told Human Rights Watch that a cell at the lower section of the site next to the warden’s office is used to house female detainees (see below on conditions for female detainees). If there are no female detainees, male detainees use the cell.

|

Torture and other Ill-Treatment of Detainees

They used to beat me with bamboo and a pipe made from a car wheel rubber that they called ‘uncle black’. They used a rope to tie my legs and hands and would use needles to [pierce] my skin, telling me to confess. I had nothing to confess.

–Former NSS detainee, in his 20s, October 13, 2019.[46]

Human Rights Watch, the South Sudan National Commission on Human Rights, the UN and other organizations have repeatedly documented how NSS uses torture and ill-treatment during arrests and in its facilities in the capital, Juba and in other states systematically.[47] NSS officials inflict serious abuse, or allow serious abuse to be inflicted, on suspects and detainees, rising to at least the level of cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment.[48] The physical and psychological pain inflicted by these abuses is immeasurable and has left lasting scars.[49]

Most of the former detainees Human Rights Watch interviewed said officers slapped, beat and threatened or intimidated them when they arrested them.

A 24-year-old student at the University of Juba told Human Rights Watch how in September, 2018, a group of police, NSS and Military Intelligence (MI) arrested him and two others on their way home, inspected their belongings, then took them to a residential house in Mia Saba neighborhood in Juba, where they beat the young men while interrogating them and detained them for a night before transferring them to Blue House: “One of them slapped and kicked me and said “you will not go home until you say the truth.”[50]

Once in detention and during interrogations, torture and other ill-treatment was widespread in all NSS detention facilities. Nineteen out of the 48 former detainees interviewed for this report have been subjected to torture or other physical ill-treatment while in NSS custody. Thirteen detainees described being beaten with various tools including sticks, whips, pipes, and wires. Two reportedly were subjected to electric shocks, and two others were burned with melted plastic on their skin. Detainees also reported rape and other forms of sexual violence.

Torture and ill-treatment of detainees was prevalent in all three NSS facilities in Juba.

Riverside

Detainees held at Riverside told Human Rights Watch that NSS officers beat and subjected them to physical pain frequently either within the first hours and days of the detention; in some cases it lasted the entire detention period.[51] Methods of physical torture and ill-treatment varied and include beatings with sticks, whips, and cable wires, dripping melted plastic skin, cutting with knives and glass, being electrocuted, piercing testicles and skin with needles and other sharp objects.[52]

A detainee held at Riverside for four months between May 2017 and September 2017 recalled that officers were sadistic:

“They would remove all your clothes and you remain only with underwear. [Four men] would hold your hands and legs down. They caned you until you start bleeding…For at least three days you could not sit on your buttocks. The beating was normal. It could happen anytime they wanted.”[53]

A former NSS officer told Human Rights Watch that detainees at Riverside were tortured during their first days or weeks of arrival in the site to “break them” and force them to confess to crimes, false or otherwise. He said, “[They]were sometimes hung upside down from a rope on a tree or a pole and would be tortured in a small room in the facility.”[54]

Detainees were also verbally threatened. A 19-year-old activist and student detained for 23 days at the Riverside site in 2018 told Human Rights Watch that he was threatened with a pistol, caned, kicked, and slapped during the first three days of interrogations. “They would step on my head with their boots and say if I looked at them or smiled, they would kill me. They said if I did not confess to my crime, I would be thrown into the river in a sack,” he recalled.[55]

In some cases, detainees were tortured in locations outside of Riverside such as the Giyada military barracks, residential houses, Luri training site and other secret places of detention.[56]

Blue House

Detainees held at the NSS detention site at Blue House told Human Rights Watch that torture was more frequent in the lower section of the site compared to the upper section where political detainees or VIPs were held. A detainee held in the lower section, released in August 2018, said that NSS officers beat him for close to a year of his three-year detention. He sustained injuries to his backbone and had his foot broken. He described the beatings:

They took me to the courtyard at night and tied me up, then put me inside a sack…and beat me with sticks and rods. Every day they would torture and beat me…they would bring me out and lash me 50 times. I have scars on my chest and back from the beating. My body is all scarred up even on my belly...Even my right foot is broken.[57]

Hai Jalaba Site

Detainees held at Hai Jalaba site said they were beaten, stripped naked, and verbally threatened by NSS officers.[58]

A 39-year-old former detainee held there for three weeks in 2019 said officers beat detainees regularly:

“They would us make us lie down in a row and give you lashes with a rubber pipe as prescribed by a senior officer. Sometimes it would be 50 or 30 lashes. They would bring young officers who had energy to beat you. They beat me every two days. Until I got sick.”[59]

He also said detainees were subjected to forced labor every morning including washing the cars of senior officers, cleaning toilets, and clearing the compound of rubbish, grass and bushes.[60]

Evidence of Sexual Violence

As described below, rape and other forms of sexual violence, including forced nudity against male detainees were reported in all the NSS detention sites. While there is less documented evidence of rape and sexual violence against female detainees, both male and female former detainees described conditions and contexts which indicate such violations of female detainees regularly occur.

A male detainee held in the lower section of Blue House site for two weeks and four days in 2018 said he was gang-raped over a two-day period by NSS officers:

We were in separate isolation rooms. My room was small and had no window or sun or power. It was very hot. I was allowed out in the morning and evening for shower. I was beaten by the soldiers and national security. After a week, I was raped by three male officers who said if I accepted, they would help get me out. They did it one after the other also. It was painful but I had no choice. They kept me another week and then released me.[61]

Three detainees held at Riverside also reported rape and other forms of sexual violence.[62] A 26-year-old activist arrested in December 2016 and detained for four months at the Riverside site said NSS officers subjected him and seven other detainees to torture and gang rape on multiple occasions. He described how NSS officers on orders from a Lt. Col. raped him and other detainees on various occasions:

My hands were tied. I was raped by four people and another time they were six. There were many officers involved. One of the [officers in charge] said, ‘you take these boys and go entertain yourselves.’ On another day he said, ‘go and take these boys and go wash them,’ and I thought I was going to take a bath because I had not for many days. I was taken out to a tent and they raped me.[63]

Another activist in his 20s also said he was raped by two NSS officers at Riverside: “They raped me [in the toilet] one after the other. Then they told me to wash myself and get back to the cell,” he recalled.[64]

The South Sudan National Human Rights Commission documented the unlawful detention and torture of 29 men from greater Aweil in Northern Bar el Ghazal state by the NSS at the Luri military training facility in Luri, on the Yei-Juba road, between June 29 and July 7, 2018.[65] The Commission found that prisoners were kept in rooms of 5m by 3m and were “routinely stripped of their clothing and placed naked in an isolation cell. In other instances, they were forced to cultivate the farms of senior officers when naked while guards observed them.”[66]It also found that detainees showed wounds consistent with beatings from canes, sticks, whips and skin burns caused by drips from hot melted plastic.[67] As a result, some developed serious mental health illnesses and some became “profoundly psychotic.” [68]

NSS officers at the Luri training center, also detained, beat and sexually harassed international ceasefire monitors working with Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD). On December 18, 2018, armed men who identified themselves as NSS, blocked ceasefire monitors from accessing the facility to conduct an inspection based on allegations that there had been a breach of South Sudan’s peace agreement.[69] NSS officers detained the monitors for four hours, blindfolded and handcuffed them and subjected them to forced nudity. They forced two monitors, a colonel with the Sudanese Armed Forces and a major with the Kenyan Armed Forces, to undress down to their underpants. One female colonel with the Ethiopian Army was forced to completely undress.[70]

IGAD heads of state called upon the government “to immediately investigate the violation, bring the perpetrators and their pertinent superiors to justice, and apologize to the victims and the countries they represent for the criminal act committed and notify the Council on measures taken as a matter of urgency.”[71]

In May 2019, a senior NSS officer attached to Ceasefire and Transitional Security Arrangements Monitoring Mechanism (CTSAMM) said that the monitoring body was exaggerating the incident and to date there has been no accountability for the abuses.[72]

Female Detainees

Female detainees are at risk of sexual violence by both officers and male detainees. Former male detainees at Blue House held near the female cell told Human Rights Watch they overheard conversations which indicated that male officers forced female detainees to have sex, offering to free them from detention if they submitted.[73] One former detainee, a male in his 40s held in Blue House for over three years, recalled:

They will bring women and detain them in one room and at night they will just pick them [out]. Most of them are foreigners from Kenya, Ethiopia and Uganda. These are the ones we see coming from time to time and they do not stay for long. Provided you fulfill the obligation they will release you.[74]

Human Rights Watch interviewed four women held at Blue House and Riverside between 2015-2019. Although none of them described accounts of sexual violence, they said conditions of detention exposed them to the risk of sexual violence by officers and detainees.[75] A former female detainee held at Blue House for 2 months in 2018 recalled. “I could not sleep through the night. Sometimes I could hear the male inmates saying, ‘I need a woman, and there is one there, let us get her.’”[76]

Solitary Confinement

The detention at the Blue House site has six solitary confinement rooms in its upper section and another six in its lower section. The rooms known as “zanzana” are described by detainees to measure around 1m x 1m or 2m x 2m. The Riverside facility had five solitary confinement cells measuring 1x1m. Prolonged solitary confinement may amount to torture.[77]

High-profile detainees, such as politicians or those accused of having committed a serious crime were often held in solitary confinement.[78]

Human Rights Watch spoke to four detainees who between 2017-2019 were held in solitary confinement.[79] James Gatdet Dak, the spokesperson of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army-In Opposition (SPLM/A-IO) led by Dr. Riek Machar, described his solitary confinement in Blue House from November 2016 until February 2018:

They did not allow me to talk to other prisoners [and I had] no access to radio, newspapers, or anything. I was locked up 24 hours a day and [officers] came only once to let me shower and use the toilet. At 3 p.m. they brought me a meal and that’s when they would let me use toilet, but not more than five minutes.

Marko Lokidor, the former SPLM/A-IO governor for Eastern Equatoria who was abducted by national security operatives from Kakuma Refugee camp in Kenya on December 29, 2017, was held in solitary confinement in the upper section of the Blue House site for 90 days. “The experience that I actually encountered is psychological torture. When you don’t have access to your family or relatives and friends or other detainees, it is unbearable torture,” he recalled.[80]

Arbitrary Arrests and Detentions

“Don’t you know that we can kill you now if we want? Don’t you know that nobody knows you are here? You don’t even have a file here.”[81]

–30-year-old former NSS detainee, December 2018.

Almost all former detainees interviewed for this report said that they were not told why they were arrested and detained, and they were not charged or brought before a judge at any time.[82] In many of the cases, NSS officers simply accused detainees of opposing the government or supporting the rebels. Some individuals were also accused of theft, fraud, murder, detained as proxies for relatives or to settle personal scores.

Except for a group of high-profile detainees charged with crimes against the state, most of the detainees Human Rights Watch interviewed were not charged with a crime or presented before a court.

These detentions violate fundamental international law due process rights, also incorporated into South Sudanese law, that require anyone arrested be informed immediately of the reasons for their arrest, that they be brought promptly before a judicial authority to be charged or released, and that their detention have a legal basis such as reasonable suspicion that they have committed an offence.[83]

A former NSS detainee in his 40s said he was arrested in Wau on November 8, 2015 and detained in the upper section of the Blue House used to hold political detainees and other high-profile figures. He was released after a year and nine months, with 19 other detainees who had also been detained in the same site: “I was never interrogated. From my arrest to my release, they did not tell me any evidence of a crime. What crime was I paying for?”[84]

Human Rights Watch also found that officers from the legal department of the NSS, mandated to advise the service on issues of constitutionalism, rule of law and human rights, also participated in violations of due process rights. A 26-year-old former detainee who was a security guard, told researchers he was summoned by phone to the Blue House in October 2016 and detained there for 18 months without charge.[85] He said that during the first 10 days of his detention, he was interrogated once by investigators from the NSS legal department: “They said, ‘You are a criminal!’ and they kept accusing me of supporting rebels... I asked where the evidence is, who is the complainant, what did I do? They said if I don’t confess, I will stay there forever. They did not call me again until my release.”[86]

Lack of Proper Documentation of Detainees

Detainees told Human Rights Watch that they were held or transferred to and from various facilities in and around Juba, including Riverside, Blue House, Hai Jalaba, Luri and the NSS office at Juba International airport, Jubek/Central Equatoria state security offices, police stations and unofficial detention facilities, as well as the South Sudan People’s Defence Force (SSPDF) military barracks at Bilpam, Giada, and Gorom in Juba. Detainees were also transferred from Wau, Kapoeta, Yambio, Aweil, Torit and Yei by road or air, demonstrating that these NSS abuses are widespread around the country. According to those interviewed, these transfers were often arbitrary with verbal instructions rather than files or documents indicating why they had been arrested or were being transferred.

A detainee arrested in Kapoeta, recalled how after 18 days in detention at the NSS office there, NSS officers transported him blindfolded and handcuffed to Juba. When they arrived at the Blue House, he learned that there was no paperwork about his arrest or transfer but NSS officials at the Blue House still took him into custody. “Even the officer in charged asked [his colleagues] ‘who is this person and why is he here?’”[87]

Former detainees, lawyers and family members consistently complain that it is almost impossible to trace detainees in NSS custody. This lack of records is not only a violation of due process itself, but it directly makes detainees more vulnerable to serious violations such as torture and enforced disappearances. A detainee in his mid-30s told Human Rights Watch he was threatened with death by NSS during interrogation in 2017: “Don’t you know that we can kill you now if we want? Don’t you know that nobody knows you are here? You don’t even have a file here.”[88]

Lack of Access to Legal Counsel

International norms and South Sudanese law require that defendants have the right to consult promptly with a lawyer.[89] However, in most of the cases documented by Human Rights Watch, NSS did not allow detainees access to lawyers at any stage.[90]

A detainee held at Blue House from late 2016 to April 2018 told Human Rights Watch he explicitly asked for a lawyer but was denied access to one; “They interrogated me for two days. I said I would not speak without a lawyer. They said, “You go think about it” and sent me back to my cell. The next time they called me was after 5 months.”[91]

The NSS also intimidated and harassed lawyers. One lawyer who was acting on behalf of the family of a detainee held at Blue House was denied access to his client on two occasions and subjected to verbal abuse and told by a senior NSS officer, “If you are not careful, even you will need a lawyer soon.”[92]

Denial of Visitors, Family

In the cases documented by Human Rights Watch, detainees held at the Riverside site seemed to have been granted the least family visits. Of the 14 cases documented between October 2015 and November 2019 at Riverside, only two individuals were allowed family visits. Detainees held at Blue House said that the NSS very rarely allowed families to visit. For those held for prolonged periods, they said guards and security officers sometimes allowed a family to drop off food, water, medicine, and other provisions for a detainee, but would not allow meetings with detainees.[93]

Human Rights Watch found that family members of NSS detainees are often not informed of the arrest and detention of their relatives, must work persistently through their own networks to obtain this information, and are then often not allowed visits to their loved ones.

One woman whose husband was detained by NSS on November 8, 2018 told Human Rights Watch how NSS officials denied her access to her husband when he was detained at the Blue House: “I would go every day. On the sixth day they allowed me to see him in the office reception at Blue House. I tried again after and failed to access him.”[94] In February 2019, her husband was moved to Juba central prison where she had regular access to him. In January 2020, the high court ordered his release.[95]

Moreover, NSS does not allow regular visits by national or international rights monitoring bodies. Of those interviewed, only one detainee, James Gatdet, said he had been granted visits from the ICRC in November 2017, possibly due to the international nature of his case and his high political profile. [96]

Deaths in Custody

Former detainees told Human Rights Watch that at least 12 detainees died due to poor health and poor detention conditions at the Blue House between July 2017 and November 2019.[97] One detainee who witnessed his cellmate die after complaining about stomach ulcers in early 2018 recalled: “It was the first time in my life to see someone die. It was painful.”[98]

Former detainees said officers executed detainees. Human Rights Watch documented one example of this. Officers extrajudicially executed a detainee named “Malesh” around June 2018 in the upper level of Blue House, according to a witness detained at the same time, who explained:

“The security officers wanted to bring him out at night at around 1 or 2 a.m.; usually they go to torture people around this time. He was fighting them and resisting leaving his cell. They shot him and he died.”[99]

On October 7, 2018, a group of prisoners at Blue House disarmed their NSS guards in protest against their detentions, torture, “nightly pick-ups of detainees” and extrajudicial killings in custody.[100]

It is unclear what happened to the bodies of those who died or were unlawfully killed while in custody. Detainees said that if the person apparently died from ill health, NSS officers could take the body to the Juba teaching hospital or Giyada military hospital mortuary, notify relatives of the deceased and in rare cases arranged for the transfer of the deceased to locations outside the capital city or provide money to the family for transport and funeral.[101] In one case, the NSS apparently flew the deceased body to his home area in Tombura, Western Equatoria in mid-July 2017 and gave the family some flour, beans and little money.[102] It is not clear if autopsies were ever performed to establish and formally record the causes of death. One former NSS officer said that if torture or extrajudicial killing was involved, family members were not notified of the death or burial of their loved one.[103] Multiple sources told Human Rights Watch that they heard that bodies of deceased detainees were sometimes thrown in the Nile river, burnt or buried in unmarked graves.[104] Human Rights Watch could not independently verify this.

Release from NSS detention

NSS have released detainees as suddenly and as arbitrarily as they had arrested them and overwhelmingly without being charged with any crime. On at least four separate occasions between 2015 and 2019, President Kiir ordered the release of political prisoners and detainees whom he deemed “prisoners of war,” who were arrested and detained by the NSS in connection to the insurgency and rebellion against the state, in accordance with the terms of the 2015 and 2018 peace deals.[105] Some of those released and documented by Human Rights Watch included human rights defenders and journalists, petty criminals and others who do not fit any possible criteria of “prisoners of war.”[106]

Accounts of why or how detainees regained their liberty reveal a variety of circumstances that underscore how arbitrary the NSS detention practices are. For example, some detainees were released following intervention by influential government officials or senior political and military figures or had a relative act as a guarantor.[107]

Some said they had to pay to be released. Human Rights Watch documented four cases in which detainees or their families paid NSS officers to secure their release with the highest amount being 1.5 million SSP (US$ 5000 at the time), sums which most detainees could not pay.[108]

In other cases, detainees were offered pre-conditions for their release. William Endley, a South African national and former adviser to the South Sudanese opposition leader, Riek Machar, was offered money twice and told he would be released if he denounced Riek Machar and joined his rival at the time, Taban Deng Gai.[109] He refused. A political activist who had been detained in Blue House for his criticism of various government officials said the NSS offered to release him if he agreed to join the service. He refused but was released due to poor health in September 2019.[110]

In some cases, NSS detainees after a lengthy period of unlawful detention were taken before a judge and charged. Once trial commenced or ended, they were transferred to the regular civilian justice system and taken to an official detention center, such as a police station or Juba central prison. In the cases of Peter Biar, Kerbino Wol and James Gatdet, they were transferred from NSS detention to regular prisons only after they were sentenced by a court.[111]

Almost all detainees interviewed for this report said they were either warned or made to sign statements that they would not speak about their experience in detention to anyone especially human rights organizations. Some former detainees said they were subjected to physical surveillance post their release. Some left the country due to fear of re-arrest.

Those who wished to leave the country upon their release had to obtain clearance from the NSS or Ministry of Justice prior to their travel or arrange for new travel documents as NSS had blacklisted or confiscated their passports.[112]

Harsh Detention Conditions

Conditions in all NSS run facilities were poor and unsanitary. Detainees interviewed for this report said they were held in cramped, congested, and unsanitary conditions, conditions which violate international law. Although in some cases authorities provided mattresses, most detainees slept on the bare floor, or on blankets and sheets provided by their families or that they personally procured from outside through friendly NSS officers. Some detainees even though they were being held without charge were forced to wear jumpsuits given to them by the NSS. For example, detainees in the upper section of the Blue House site known as the political or “VIP” section were given orange jumpsuits, while detainees in the lower section wore blue jumpsuits. Some wore clothes they had been arrested in for the duration of their detention or a change of clothes brought by relatives or friends.

Most detainees were held in congested cells and others in solitary confinement without fresh air or daylight and were not allowed exercise or other recreational activities.[113] At the Blue House there was a space on the top floor where VIP detainees could hold prayers, whereas detainees on the lower floor used a hall.

Inadequate Food, Water and Medical Care

Detainees from all NSS sites described inadequate and substandard food. Typically, it was a monotonous diet of posho [mashed cassava or maize flour] and beans once a day, with rice served as a substitute occasionally. Almost all detainees interviewed said the water was insufficient, salty or dirty.

Detainees also described unsanitary conditions. A 23-year-old activist detained first at Riverside and then transferred to the Blue House site in January 2017 described overcrowding and unsanitary conditions in both facilities:

At Riverside, we were 19 people in one small cell and there was no space even to stretch. The water for drinking was not clean. We were sleeping next to a toilet. Urine and fecal matter were flowing where we used to sleep; it was not sanitary at all.[114]

Detainees had limited access to medical care and attention and spoke of contracting malaria, hepatitis, stomach ulcers, typhoid, and skin infections among other illnesses. Detainees said a doctor would visit detainees from time to time and when there were serious illnesses, patients would be taken to nearby clinics, Juba Teaching hospital or Giyada military hospital for treatment.

Human Rights Watch was told of two detainees living with HIV/AIDs who were held in the Blue House site in congested cells with other detainees between 2017 and October 2019. One witness said they did not have access to their retroviral medication regularly, and this compromised their health and increased risk of co-infections.[115]

Detention of People with Disabilities

NSS does not shy away from arbitrarily detaining and mistreating people with both physical and mental disabilities. As Human Rights Watch has documented previously, authorities in South Sudan have subjected persons with disabilities to conditions that are significantly worse than for other detainees.[116] One former detainee told Human Rights Watch that NSS detained a man in his early 20s with a psychosocial disability for four months at the Riverside site in 2018:

“He was always talking to himself. He said that two people who wanted to chop off his head were chasing him, and he could hear a voice saying, ‘if you are a man, enter this compound.’ He ran into the house of an army officer in Hai Thoura neighborhood. So that officer arrested him and brought him to Riverside.”[117]

Another former detainee in his mid-30s recalled that officers at Blue House denied medical attention to a detainee with one arm from Torit who fell in the bathroom and broke his leg in May 2019. He said “he would crawl on the floor and push himself with his buttocks. He would be supported by friends and limp. It was not easy for him.”[118]

Due to the harsh conditions of detention some detainees developed psychosocial and physical disabilities while in detention and were vulnerable to abuse. Former detainees told researchers that they knew two detainees held at Blue House between 2018 and 2019 whose mental health seriously deteriorated during their detention and would be beaten by officers.[119] One of them, “Garang”, held in the lower section of the Blue House between mid-2018 to April 2019, would experience mental health crisis and fight his cellmates and draw on the wall with his own excrement.[120]

A man in his 30s from the Acholi ethnic group, detained in 2017 on accusations of being a rebel, experienced mental health issues after he said he was sexually abused by officers.[121]

“He would bang the door of his cell until morning. Officers would often kick and punch him as punishment sometimes in front of other detainees. At one point he managed to break the door off its hinge and his hands were bleeding. Officers beat him. The next evening, he continued the same.”[122]

He was freed in August 2018 never having been charged.

Conditions for Female Detainees

Former detainees, including two women, held at the Blue House said there was no separate section for women and no female officers were on duty in the facility.[123] Instead, officers cleared a cell next to the guards or detention director’s office in the lower section of the site for female detainees.[124] If there were no female detainees, men would be detained there. Women unlawfully detained by NSS include security officers, businesswomen, women accused of petty crimes and those with family connections to rebel fighters or opposition figures. [125] The UN Commission on Human Rights in South Sudan has also documented unlawful detentions of women by the NSS.[126]

In October 2019, at least two women were held in the lower section of the site, one of whom was a lactating mother together with her 8-month-old baby.[127]

There was often no water in the cell, and the women were not allowed to leave the room except at fixed times, to use the toilet. Female detainees as other detainees, did not have access to adequate health care — which should include specialized care for women — including feminine hygiene products.[128]

In one case from 2018, NSS agents held a pregnant woman for several months, without access to a doctor, releasing her shortly before she gave birth. One former inmate recalled, “She was getting sick; she was alone and there was no doctor. All of us, we felt sorry for her. “[129]

In the Hai Jalaba site, an office was converted into a cell to house a female detainee in June 2019.[130] Officers provided her a mattress, but no bedsheet or mosquito net and they would bring her bottled water and food once a day. Armed male guards escorted her to and from the bathroom twice a day.[131]

Detention of Children

The NSS has also detained children suspected of being involved with rebel groups or who otherwise are perceived to be a security threat. They were commingled with adult detainees in cells that were often overcrowded and had little access to food, clean water, or medical care.[132] Some were beaten as punishment. As with adults, they were not afforded basic due process protections, in violation of both South Sudanese and international law.[133] Detaining children with unrelated adults puts them at additional risk of physical and sexual violence and is prohibited by international law.[134]

In 2019, the NSS held a 13-year-old boy from the Toposa tribe at the lower section of the Blue House for six weeks on accusations of being a rebel fighter. Former detainees said that the NSS moved him out of the Blue House after six weeks to an unknown location.[135]

In August 2017, a detainee held in the Hai Jalaba site for two days said he witnessed a boy being caned by officers. The boy was detained on accusations of spying on the NSS: