Summary

“I skip a meal so my children can eat and to ensure that the bills are paid.”

-Janet, 35, March 2020

“Janet R.,” 35, a single mother who works at a college student advice center in London, suddenly found herself on the verge of financial ruin. On January 31, 2020, the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP), the United Kingdom’s ministry for social security, transferred her to a new benefits system known as Universal Credit. In early March, she received her first monthly payment. When she saw that it would only be £388 (US$502), she said she had a panic attack. This was £1000 short of what she needed to cover her rent, pay her bills, and support her two children in one of the most expensive cities in the world.

Janet was sure that the DWP had made a mistake. After she got notice of her first payment on March 2, she immediately rang the Universal Credit helpline and pleaded with an agent to review the payment. But he told her that the system was working exactly the way it was supposed to. That same day, she filed an appeal, but ended up overdrawing on her bank account and borrowing money from friends to cope. “I am living on whatever I can find in my cupboard at the moment,” said Janet.

As Janet struggled to make ends meet, the coronavirus was beginning to spread rapidly across the country. On March 23, the government imposed a nationwide lockdown to curb the outbreak, triggering widespread job losses despite various government measures to support small businesses and subsidize the wages of furloughed employees. The UK’s economy contracted by 20.4 percent between April and June 2020, according to official figures, the biggest slump among comparable economies in Europe. Between March 16, when the government first began to advise against non-essential activities, and June 23, around 3.4 million people applied for Universal Credit. This is roughly six times the number of claims the government processed during the same period in 2019.

The DWP has touted the automated design of the program as a key reason why it has managed to cope with this unprecedented surge in new claims. But longstanding flaws in the way that Universal Credit has been digitized and automated are also responsible for the severe difficulties that people like Janet face.

A flawed computer model that the Department uses to analyze people’s earnings had mistakenly concluded that Janet had earned twice her regular wage in February. This error caused another part of the automated benefits system – the algorithm that applies means-testing rules – to misfire, shrinking the size of Janet’s first payment on the assumption that she needed far less support than she was entitled to.

Although Janet’s payments appear to have stabilized since April, she is concerned the problem will recur: “I’m always on eggshells. I don’t know what’s around the corner, There’s no room for budgeting under Universal Credit.”

Janet’s experience is far from unique. The difficulties many people face in claiming Universal Credit, an automated benefits program that has been rolled out gradually since 2013, have been well-documented by civil society groups, frontline social security advisers, media, parliamentarians and official watchdog bodies.

To simplify access to benefits and reduce administrative costs, Universal Credit aggregates six social security benefits into a single benefit, calculated and paid monthly. This social security overhaul was also driven by a belief that the new system would incentivize (re)entry to work and reduce welfare dependency.

This report documents how the government’s drive to promote efficiency and personal responsibility through Universal Credit has led to flawed design choices that are depriving people of essential social security support in the UK. As they borrow money to cope and turn to food banks to provide for their families, these restrictions on their right to social security are also undermining their rights to food and other essential elements of the right to an adequate standard of living.

Human Rights Watch has found that requiring people to apply for Universal Credit online has made it difficult for people who do not regularly use computers or the internet to access their welfare benefits. Extensive questionnaires about people’s personal and financial circumstances, along with cumbersome identity verification requirements, make the process even more challenging.

A decade of austerity-motivated cuts to local authority budgets has depleted access to computers in libraries and community centers, fueling demand for digital support. The government has provided some charities with funding to guide people through the application, but the demand still outstrips available resources.

Challenges with the digital benefit endure past the application process. People on Universal Credit told Human Rights Watch that they struggle to manage benefit-related tasks online, such as providing evidence that satisfies job-seeking tasks that are a condition of maintaining their benefit. In some cases, the failure to record sufficient evidence that they have fulfilled these tasks has led to crippling sanctions, a punitive measure imposed by the DWP to reduce monthly payments.

Universal Credit is also a major effort to automate the social safety net. However, flawed means-testing rules, administered through an error-prone automated system, are creating payment delays and irrational fluctuations in the benefit for many people in low-paying or unstable jobs. These problems are causing financial hardship and food insecurity, as well as negatively affecting people’s mental health.

The Department has built a means-testing algorithm to work out how much people are entitled to each month, based on a variety of data inputs about their financial and personal circumstances. But one of these inputs – how much people earn – is sometimes wrongly calculated, causing the algorithm to produce extreme fluctuations in people’s benefits.

The DWP uses payroll information uploaded by employers to the Real-Time Information System (RTI), the government’s tax management system, to calculate how much people earn each month. But the computer program that the Department created to perform this calculation fails to factor in how frequently people are paid, leading it to overestimate their earnings in some months and underestimate them in others.

This design flaw has caused irrational fluctuations and reductions in how much benefit people like Janet receive from month to month. People affected by this flaw told Human Rights Watch that they were forced to rely on food banks, fell behind on rent, and took on debt as a result. Some of those interviewed also said the constant pressure that comes with managing their benefit is taking a toll on their mental health, and that they are experiencing heightened anxiety and depression.

While the Court of Appeal ordered the DWP to fix this design flaw in June 2020, it limited its ruling to cases where people draw a regular monthly salary. The DWP has accepted the ruling, but is still figuring out how to implement it at the time of writing. It has not said whether it will compensate people affected for benefit losses and financial difficulties they suffered because of this flaw.

The duration of the means testing process also makes people wait about five weeks before receiving their first payment. Human Rights Watch found that this is a delay many can ill-afford, especially if they have just suffered income or job loss. This delay was particularly acute during the Covid-19 lockdown, when job losses were sudden and severe. DWP officials have repeatedly cited the automated nature of the assessment process as a key reason why they cannot reduce or eliminate the five-week wait.

The report is based on 35 in-person and telephone interviews with people on Universal Credit and experts conducted between March and July 2020 in the UK. The report builds on previous Human Rights Watch research showing that austerity-motivated cuts to social security spending were contributing to record levels of food poverty and insecurity in the country.

To help people cope with the economic crisis triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic, the government has enacted a £20 weekly increase to the Universal Credit standard allowance, and temporarily relaxed the rules for applying for and maintaining the benefit. As a result, the program has been a “great support anchor for many people that have applied for social security benefits as a result of Covid-19,” said Darren Leighton, project manager of Hartlepool Action Lab, an anti-poverty charity in the North East.

But emergency relief measures, some of which have already expired, are an inadequate substitute for long overdue reforms to Universal Credit, which are needed to protect the rights of “people fighting to stay afloat before [the Covid-19 crisis] and who remain trapped in poverty,” Leighton said.

Reforms that Human Rights Watch and others have urged include additional digital support for people who are still struggling with claiming and managing Universal Credit online, more options for claiming the benefit offline, and increasing access to public computers. The government should also urgently review how means testing is currently automated, ensuring that the redesign protects people’s rights across a wide range of personal and financial circumstances. In the meantime, it should implement stopgap measures such as one-off grants to offset the five-week wait.

While some of these reforms will require increased government spending, they will help create a benefits system that is truly responsive to people’s needs and complies with the government’s international human rights obligations.

The government’s response to the economic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic shows that it recognizes the State’s obligation to intervene and protect people’s rights to social security, food, and other elements of an adequate standard of living from severe and unforeseen economic shocks. That same moral imperative and commitment to find solutions needs to be applied to people who are being failed by Universal Credit.

Glossary and Acronyms

|

Advances |

An advance Universal Credit payment that people can apply for if they are in financial hardship while they wait for their first payment. Advances must be repaid through deductions from future benefits. |

|

Algorithm |

A sequence of instructions that tells a computer how to perform certain tasks |

|

Carers’ Allowance |

A cash benefit to help people look after someone who needs to be cared for |

|

CESCR |

United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the treaty body that monitors implementation of ICESCR |

|

Child Tax Credit |

A legacy benefit that provided an income boost for people with eligible children |

|

Claimant Commitment |

A record of the responsibilities that people are required to accept as a condition of receiving Universal Credit. People who fail to satisfy the Claimant Commitment may lose their benefit. |

|

Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme |

A government program between March and October 2020 to help employers cover a portion of the salaries of furloughed employees |

|

DWP |

Department for Work and Pensions, United Kingdom government ministry for social security |

|

Economic Affairs Committee |

A select committee of the House of Lords (the upper house of the UK Parliament) that examines economic affairs |

|

ESA |

Income-related Employment and Support Allowance. A legacy benefit for people with a disability or health condition that affects their ability to work. |

|

Food bank |

A generic term to describe non-state agencies that provide limited food and other basic supplies (which are received as charitable donations) to people in acute need for free. Some food banks limit food parcels they provide to people, while others do not. |

|

GOV.UK Verify |

A revamped online process the UK government rolled out in 2016 to enable people to verify their identity – a prerequisite for accessing government services such as Universal Credit and filing taxes. The service is operated by third-party identity providers. |

|

Government Gateway |

An online process the UK government rolled out in 2001 to enable people to verify their identity and register for government services |

|

HMRC |

Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs, the United Kingdom government’s tax authority |

|

Housing Benefit |

A legacy benefit that provided rent assistance for people who are unemployed or on low income |

|

ICESCR |

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, to which the UK is party |

|

Income Support |

A legacy benefit for people with no income or living on low income |

|

Jobcentre Plus |

A UK government employment and social security agency that is found in most cities. It is primarily designed to assist people who are unemployed and claiming benefits, and part of the DWP. |

|

JSA |

Income-based Jobseeker’s Allowance. A legacy benefit for people looking for work. |

|

Mandatory Reconsideration |

A person’s request to the government asking them to review a benefit-related decision. This is the first step of the process for appealing benefit-related decisions. |

|

Monthly assessment period |

A rolling one-month period that begins the date people submit their claim for Universal Credit. The calculation of a person’s monthly Universal Credit award factors in all income received during this period, along with any changes in their personal and financial circumstances. |

|

NAO |

National Audit Office, an independent statutory body that audits public spending and government departments for the UK Parliament |

|

National Minimum Wage |

The minimum hourly rate that most workers in the UK should get, depending on their age and whether they are an apprentice |

|

OBR |

Office for Budget Responsibility, a non-departmental public body that audits government spending |

|

RTI |

Real-Time Information system, a tax reporting and management system created by HMRC and used by the DWP to calculate people’s Universal Credit |

|

Standard allowance |

The base amount of benefit that people are entitled to under Universal Credit |

|

Taper rate |

A means-testing rule of Universal Credit, which reduces benefit payments by 63 pence for each pound earned from paid work |

|

UDHR |

Universal Declaration of Human Rights |

|

Universal Credit |

The UK government’s automated benefits program, which combines and gradually replaces six existing legacy benefits (Income Support, JSA, ESA, Housing Benefit, Child Tax Credit and Working Tax Credit) into a single benefit calculated and paid monthly. The benefit is administered online. |

|

Work allowance |

A portion of earnings that people on Universal Credit who meet eligibility requirements (e.g. if they have childcare responsibilities) are permitted to keep before the taper rate is applied |

|

Work and Pensions Committee |

A select committee of the House of Commons (the lower house of the UK Parliament) that examines the DWP’s policies and spending decisions |

|

Work coach |

Jobcentre Plus staff that provide advice and support to people who are unemployed and claiming benefits. Also referred to as “Job Coach” |

|

Working Tax Credit |

A legacy benefit that provided an income boost for people who are living on low incomes |

|

Zero hours contracts |

Employment contracts where the employer is not required to guarantee their employees fixed hours |

Key Recommendations

To the United Kingdom Government

- Ratify the Council of Europe’s Revised European Social Charter (ETS No. 163, 1996).

To the Department for Work and Pensions

- Urgently conduct a review of the monthly assessment period, carefully evaluating proposals to fix its flaws, such as moving to a weekly or fortnightly assessment period, or using averaged earnings over multiple periods to smooth out fluctuations in the monthly award;

- Evaluate reform proposals in consultation with a wide variety of stakeholders, including anti-poverty charities, charities that provide direct services to local communities, people with lived experience with poverty, public interest technologists, and independent social security experts;

- Until the five-week wait has been shortened or eliminated, allocate resources to convert advances on people’s first Universal Credit payments into one-off, non-recoverable grants;

- Suspend the recovery of advances for people who have begun to repay them, or at least for any person where there is evidence of imminent likelihood of severe food insecurity, homelessness or destitution;

- Suspend the recovery of all other government debts for the duration of the economic crisis caused by the Covid-19 pandemic;

- Expand telephone, in-person, and paper options to apply for Universal Credit, including through increased funding and support to the “Help-to-Claim” service, Local Authorities and charities providing direct services to local communities; and

- Increase the availability of public access to internet-enabled computers, including through the allocation of financial resources to support IT access in public libraries and community centers.

To Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs

- Work with the Department for Work and Pensions to make appropriate modifications to the Real-Time Information System that will enable the Department to implement necessary changes to the monthly assessment period.

To the UK Parliament including the Work and Pensions Select Committee and the Economic Affairs Committee

- Continue to monitor where funding and other initiatives to support people applying for and managing Universal Credit online are falling short, and develop recommendations to shore up support;

- Continue to monitor the impact of monthly fluctuations in payments and reductions in benefit amounts, particularly for people with uneven earnings and volatile working hours; and

- Examine the case for enforceable rights to social security and to an adequate standard of living.

Methodology

Based on research conducted in the UK between September 2019 and July 2020, this report documents how the automation of Universal Credit makes it difficult for people to apply for and manage the benefit, leading to financial hardship and food insecurity, and negatively affecting their mental health.

Between March 1 and July 6, 2020, Human Rights Watch interviewed 35 people, including people claiming Universal Credit, volunteers at the Newcastle West End Foodbank, staff and volunteers at Citizens Advice Newcastle, volunteers with the Independent Workers' Union of Great Britain in London and Cambridge, and anti-poverty charities and think tanks in the North East and London. Human Rights Watch interviewed 14 people claiming Universal Credit: 9 in person, and 5 over the phone. Twelve of them are in North East England, and two of them are in London. Due to lockdown restrictions imposed to contain the Covid-19 pandemic, Human Rights Watch has conducted all interviews since March 12, 2020 over the phone.

All interviewees freely consented to the interviews, and Human Rights Watch explained to them the purpose of the interview and did not offer any remuneration. Human Rights Watch also explained to them that they could stop the interview at any time and decline answering any question. All interviews were conducted in English and covered a range of topics related to Universal Credit and its impact on interviewees’ rights to food and an adequate standard of living, budgeting and personal finances, and mental health. The average length of each interview was approximately one hour.

The names of most people claiming Universal Credit interviewed for this report have been replaced with pseudonyms to protect their privacy. These pseudonyms are indicated clearly as such with quotation marks on the first use.

The report focuses on North East England, and the capital city, London, for a number of reasons. The North East has the third-highest rate of people on relative low income after housing costs, indicating that the population experiences higher-than-average levels of poverty and inequality. Newcastle upon Tyne (more commonly known simply as Newcastle), the most populous city in the region, was also the first major urban center outside of London to fully roll out Universal Credit, in 2017. London is home to people living in one of the most expensive cities in the world. London also has the highest percentage of people on relative low income after housing costs in England, indicating higher-than-average levels of poverty and inequality.

In researching the report, Human Rights Watch also analyzed case studies provided by social security benefits advisers and volunteers in London and the North East (Newcastle, Gateshead, Stockton-on-Tees and Hartlepool), in addition to reviewing data published by the DWP and other government bodies, court filings, reports and surveys by technology experts, anti-poverty campaigners, and social security and employment think tanks, academic articles, and credible media reports. Human Rights Watch also interviewed staff and volunteers from a wide range of charitable organizations working in the areas of benefits advice, legal advice, social security policy, mental health, and poverty. Human Rights Watch also used benefits calculators provided by Ferret Information Systems, a company that offers benefits advice systems and consultancy, to simulate how fluctuations and reductions in Universal Credit might affect a family of four.

On March 13, 2020, Human Rights Watch submitted a Freedom of Information request to the DWP requesting more information about how it automates the benefits calculation process, but has yet to receive a response. On July 1, 2020, Human Rights Watch sent a letter to the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions summarizing our findings and requesting responses to specific questions about the human rights impact of Universal Credit’s automated design. Human Rights Watch sent a follow-up email to the DWP on July 24, 2020. The Department has not responded at the time of writing.

I. Universal Credit: A Troubled Overhaul of Social Security Support

In 2013, the UK government began rolling out Universal Credit, a social security program that provides cash assistance to unemployed people or people on low income.[1] People claiming the benefit must generally be of working age (above 18 and below the State Pension age, which is periodically reassessed), have £16,000 (US $20,682) or less in savings, and live in the UK.[2]

Universal Credit consolidates six “legacy” social security benefits into a single benefit paid monthly.[3] In the government’s 2010 white paper outlining its proposal for welfare reform, this change was billed as a “simpler, streamlined system”[4] that would improve efficiency and save costs, primarily through automating processes and maximizing “self-service.”[5] Then-Secretary of State for Work and Pensions, Iain Duncan Smith, also declared that this simplified system would “ensure that work always pays and is seen to pay.”[6]

|

The Six Legacy Social Security Benefits that Universal Credit replaces Income Support: for people with no income or living on low income Income-based Jobseeker’s Allowance: for people looking for work Income-related Employment and Support Allowance: for people with a disability or health condition that affects their ability to work Housing Benefit: assistance with rent for people who are unemployed or on low income Child Tax Credit: an income boost for people with eligible children Working Tax Credit: an income boost for people who are living on low incomes |

The government opted for a monthly payment scheme to meet the purported needs of the ‘model’ claimant – someone who is paid a steady (though low) monthly wage, with regular monthly outgoings for rent, household bills, and other living expenses.[7] While this is a significant break from the fortnightly frequency that legacy benefits are paid, the government vowed that it would manage the transition in a way that would “minimise disruption” to people claiming benefits and the organizations that support them.[8]

The government originally expected to complete roll out of the program nationwide by April 2017, but this has now been pushed back to September 2024.[9] These delays prompted the National Audit Office (NAO), which monitors public spending for Parliament, to raise concern in 2018 that the government “cannot be certain that Universal Credit will ever be cheaper to administer than the benefits it replaces” – doubts it reiterated in its 2020 review.[10] The Office for Budget Responsibility, the government’s own public spending watchdog, also indicated in 2018 that savings generated by Universal Credit are likely to be significantly smaller than anticipated.[11]

As of May 2020, a total of about 4.2 million households, or 54 percent of all households claiming benefits in the UK, are on Universal Credit.[12] In North East England, 212,823 households, or 55 percent of all benefits households in the area, are on the benefit. In London, 674,160 households, or 56 percent of all benefits households, are on the benefit.[13]

The Rules of Universal Credit

People claiming Universal Credit receive a minimum standard allowance that is calculated by their age and relationship status (i.e. whether they are single or living with a partner). From April 2020 onwards, to help people cope with the economic fallout from Covid-19, the government has increased the standard allowance by £20 per week.[14] This increase, however, is scheduled to expire in April 2021.[15]

In April, the Treasury also confirmed that it would end the widely criticized freeze on benefit levels imposed since 2016, and raise Universal Credit and other working-age benefit payments by 1.7 percent.[16] This adjustment to help keep pace with inflation is long overdue, but it does not sufficiently address the steady, cumulative loss of value of social security support in real terms in recent years. Earlier Human Rights Watch research found that the failure of benefit levels to keep pace with inflation contributed to an alarming rise in food poverty in the country.[17]

As a result of the Covid-19 assistance and the inflation adjustment, single people aged 25 or over have seen their standard monthly allowance increase from £317.82 to £409.89 beginning April 2020.[18] The standard allowance of a couple where one or both of them are 25 or over increased from £498.89 to £594.04.[19] In addition to their standard allowance, people may also be eligible for assistance with other costs, such as housing, childcare, caring for other dependents, or a health condition or disability that limits their ability to work.[20]

In a bid to incentivize work, the DWP introduced several new means-testing rules that vary the amount of Universal Credit a person receives based on their income and personal circumstances. It eliminated restrictions on how many hours people can work while on the benefit. It also introduced a taper rate that reduces benefit payments by 63 pence for each pound earned from paid work.[21] People with childcare responsibilities or a qualifying disability or health condition are permitted to keep a portion of their earnings (known as their “work allowance”) before the taper rate is triggered.[22]

The Automation of Universal Credit

The DWP has indicated in court filings that it relies on a computer algorithm to perform this complex set of calculations.[23] This algorithm is part of a sprawling IT system that has so far cost £1.3 billion to build, and will take another £1 billion to complete.[24]

In its most basic form, an algorithm is a sequence of instructions that tells a computer how to perform a task.[25] The algorithm programmed to calculate Universal Credit “take[s] the many and varied inputs about the claimant’s family and financial circumstances and work[s] out the award each month.”[26]

One key input is how much an individual claiming the benefit earns from work. The DWP has also automated how it obtains this information with the help of Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC), the government’s tax authority.[27]

In 2013, HMRC established the Real Time Information (RTI) system, a £307m system that aims to simplify how employers report earnings data and pay taxes.[28] Using payroll software, employers provide RTI with regular updates about the size of their workforce, who their employees are, how much they are paid, and when they are paid.[29]

This constant stream of data enables the government to monitor, in real time, whether taxes have been paid correctly and on time across the country. It also generates a moving image of how much an individual or household claiming benefits earns each month – information that enables Universal Credit’s algorithm to calculate their award.[30]

To help perform these calculations, the DWP assigns people who apply for Universal Credit a “monthly assessment period” – a rolling one-month period that begins the date they submit their claim.[31] In other words, if a person applied for the benefit on March 30, their first assessment period would run from March 30 to April 29, their second assessment period from April 30 to May 30, and so on. This assessment period is generally fixed and cannot be changed unless a new claim is started.

If the RTI system is a camera, the assessment period functions like a timer that tells it when to take a photo. The resulting snapshot is the earnings data that Universal Credit’s algorithm uses to calculate an individual’s benefit payment for that month.

The problem is that this earnings snapshot is incomplete. The data that the DWP obtains only shows how much an individual is paid and when they were paid, but not the period of work their salary covers. As a result, the DWP might detect that an individual received a £1000 paycheck on March 30 and another £1000 on April 29, but not that each £1000 salary is a monthly wage. In this example, the omission leads Universal Credit’s algorithm to compute the individual’s benefit in May based on the incorrect assumption that their combined earnings for March and April (i.e. £2000) are their monthly wage.

This inaccuracy is the source of unpredictable benefit reductions and fluctuations described in Section IV of this report. It also undermines the government’s assertion that its calculation method tailors benefit payments more precisely to a person’s financial circumstances.[32]

At the end of the monthly assessment period, which typically runs for about four and a half weeks, it takes a few more days for the payment to be processed and deposited into people’s bank accounts.[33] As a result, people wait five weeks from the date they apply for their first payment, a long waiting period ”baked into” the system.[34] Section III of this report documents the financial hardship caused by the five-week wait, which has also been widely criticized by domestic anti-poverty and social security rights organizations.[35]

|

Automation, Algorithms and Universal Credit When the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) says that Universal Credit is automated, it means that it has made a policy decision to calculate people’s monthly benefit with the help of an algorithm. An algorithm is a sequence of instructions that dictates how a computer will perform certain tasks. The algorithm the DWP has built to calculate people’s monthly award appears to be rule-based. In other words, the DWP has programmed the algorithm with a well-defined sequence of rules that tells it exactly how to analyze people’s finances in order to work out their award each month.[36] One of these rules is the taper rate, which reduces the amount of benefit a person receives by 63 pence for each pound that person earns from paid work. To perform this calculation, the algorithm is provided with data about people’s earnings from the Real Time Information system. Human Rights Watch has not come across any evidence suggesting that Universal Credit’s means-testing algorithm involves machine learning, which has attracted intense government and media attention in recent years.[37] Machine learning algorithms can be given instructions to draw inferences from large sets of data without being told exactly how to do so.[38] Many of the algorithms used in image recognition systems are typical examples of machine learning. These algorithms may be provided with images labeled as ‘cats’ and ‘dogs,’ and instructions to learn patterns from these images to produce a desired outcome (only identify cats, or only identify dogs). The patterns these algorithms discover can be used to sort a different set of images into cat and dog images.[39] It is possible that the government is using machine learning to automate other social security functions, such as its fraud and error detection programs.[40] In its 2017-2018 annual report to Parliament, the DWP claimed that it was using “cutting-edge artificial intelligence to crack down on organised criminal gangs committing large-scale benefit fraud,” but has not explained what this involves.[41] Although the hype around machine learning has focused scrutiny on its applications and risks, the misuse of any algorithm can pose serious threats to human rights. Regardless of how the government chooses to automate public services, it should ensure that the design and implementation of the algorithm complies with international human rights law. In the social security context, the government’s obligations include providing meaningful information to people about how the algorithm is affecting their social security entitlements, providing access to effective remedies when people’s benefits are affected by automation-related errors, and ensuring that the algorithm does not deprive people of their benefits on discriminatory grounds.[42] |

The Government’s Case for Benefits Automation

The government has credited automation for improvements in its ability to pay people in full and on time. According to a February 2020 report by the National Audit Office (NAO), about 90 percent of people were receiving their first payment on time, up from 80 percent in March 2018.[43] After Covid-19 lockdown restrictions were imposed in March 2020, the DWP reported even better on-time ratings: 93 percent of people who applied for the benefit during the week of March 16 would receive their payments in full and on time.[44]

Despite these positive statistics, however, the National Audit Office stressed that “a large number of people still do not receive their full payment on time.”[45] In particular, it said that people with complex claims, such as self-employed workers, or people from non-UK countries with limited English proficiency, are likely to struggle with submitting evidence for their claims, resulting in delays.[46] Some of these struggles are detailed in Section II of this report.

Furthermore, the focus on complete and on-time payments fails to capture the hardship that people endure because of deliberate policy choices embedded in the design of Universal Credit. People who suffer financial difficulties because they are forced to wait five weeks for their first payment are, by the government’s measure, paid on time. People who are paid in full may nevertheless experience irrational fluctuations and reductions in their benefit from month to month because of the DWP’s flawed payment calculation model.

The government also says that automation is helping it cope with an unprecedented surge in the number of people claiming Universal Credit, which was prompted by the lockdown imposed in March 2020 to curb the spread of Covid-19. Between March 16 and June 23, 2020, around 3.4 million people applied for the benefit.[47] A survey conducted by the Resolution Foundation, a think-tank focused on living standards in the UK, found that 74 percent of people who applied for Universal Credit since the lockdown were “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with the DWP’s handling of their claim.[48]

However, more human intervention appears to be key to these high satisfaction rates, not less. The DWP has redeployed 10,000 members of its staff to work on processing claims.[49] On April 9, 2020, the Department also set up the “Don’t Call Us, We’ll Call You” helpline, where staff “proactively call claimants if they need to check any of the information provided as part of the claim.”[50] This service not only reduced wait times on the phone, but also alleviated the burden on people to produce detailed documentation showing that they meet identity and income requirements. The Resolution Foundation found “significant demand for communication with a human agent – even among those happy to claim online.”[51]

This increase in meaningful human intervention was accompanied by temporary measures that made it easier for people to manage their claim. Instead of in-person identity verification interviews, the DWP implemented a “simple biographical questionnaire” that could be answered over the phone.[52] From March to July 2020, the Department also announced it would not impose sanctions on people for failing to meet job seeking requirements.[53]

Efficiently processing Universal Credit claims with the help of automation is also no substitute for providing an adequate amount of benefit that enables people to meet their needs that are essential for an adequate standard of living. In fact, problems with automation could worsen the effects of inadequate support.

At the program’s inception, the government assured the public that “no-one will experience a reduction in the benefit they receive as a result of the introduction of Universal Credit.”[54] But independent social security experts have found that some of the more economically disadvantaged people receive less on Universal Credit than on the legacy benefits system.

In a 2020 study of Universal Credit’s impact on families’ incomes, the Institute for Fiscal Studies, a UK economic research institute, used household survey data between 2009 and 2017 to compare how much UK households at various income levels would receive on legacy benefits vis-à-vis Universal Credit during that period. The Institute estimates that those with incomes in the lowest tenth of the population are likely to lose an average 1.1 percent of their benefits (equivalent to £100 per annum) when they go on Universal Credit, more than any other income group.[55] The Institute also found that Universal Credit rules favor certain groups of people over others – for example, employee households are more likely to gain income support, while self-employed households stand to lose considerably.[56]

As the Covid-19 pandemic wears on, the specter of more job losses has sparked growing concern that the rate at which Universal Credit and legacy benefits replace lost income may not be enough to sustain an adequate standard of living. According to the Resolution Foundation, “half of employees in the UK would end up with a disposable income out of work that was at most 50 per cent of their disposable income in work.”[57] While emergency relief measures are providing people with additional support, these are only temporary. The Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme, which has helped employers cover a portion of the salaries of furloughed employees since March 2020, is scheduled to end on October 31.[58] The government has also not said whether it will maintain the £20 boost to the Universal Credit standard allowance beyond April 2021.[59]

|

How Much Universal Credit Could a Low-Income Family Receive? There is no typical Universal Credit household or award because the financial needs and personal circumstances of families vary widely. However, Human Rights Watch analyzed case data that Ferret Information Systems, a company that offers benefits advice systems and consultancy, submitted to Parliament. Their data include estimates of how much support Universal Credit potentially provides to a low-income couple with two children. In reaching these estimates, Ferret assumed that one partner works 35 hours a week and the other works 10 hours a week, both on National Minimum Wage, drawing a net monthly household income of £1472.[60] Assuming that they also pay £650 in monthly rent, Ferret projects that they will be entitled to approximately £908 in Universal Credit.[61] Even before accounting for problems with how Universal Credit is automated, Human Rights Watch estimates that, with the income top-up of Universal Credit, this family would have an annual equivalized household disposable income of £20400. This is about 70 percent of the country’s median (£29600 in the financial year ending 2019), or 15 percent above the poverty line (£17760).[62] The Social Metrics Commission, an independent organization dedicated to developing an alternative poverty measurement in the UK, classifies people with an income within 20 percent above the poverty line as “just above the poverty line.” The Commission has found that “the experiences of those just above the poverty line are likely to be very similar to those just below it.”[63] |

II. Claiming and Managing Universal Credit

The government has designed Universal Credit to be a “predominantly digital” experience, requiring most people to apply for and manage their benefit online. According to the DWP, about 98 percent of Universal Credit claims are handled online, and only about 25,000 claims are maintained over the phone.[64]

Since Universal Credit’s inception, charities, frontline advisers, members of Parliament, and government oversight bodies have raised concern that the program’s demand of continuous online engagement is out of step with the needs of economically and socially disadvantaged people. [65] During his 2018 visit to the UK, the UN Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights found that the government’s ‘digital by default’ approach is “really much closer” to ‘digital only,’ since “very little digital assistance is available and official policy is to keep “face-to-face” help to a minimum.”[66]

The government has since increased funding to services that help people submit and manage their claim online. However, the demand for digital support still outstrips available resources, and charities, particularly smaller ones, are feeling the strain.

Problems Claiming Universal Credit

To set up an online account on the Universal Credit website, people must create a username and password, set up security questions, and verify the account with a code sent to their e-mail address.[67] They must also link their account to a mobile phone number.[68]

Penny Walters, 53, an anti-poverty activist in Newcastle, applied for Universal Credit in 2018. She recalled that the online process was a steep learning curve – she had worked in factories and kitchens all her life and was not familiar with computers. “We didn’t have computers at school,” said Walters, “I have to have help filling in anything digitally.”[69]

Many people that lack digital literacy also cannot afford a computer device or an internet connection. The Economic Affairs Committee of the House of Lords, citing official statistics on digital access in the UK, observed that “people on lowest incomes are significantly less likely than average to have a smartphone or access to the internet.”[70]

Laura Lewis Alvarado, who volunteers with the Independent Workers’ Union of Great Britain (IWGB) to help low-income migrant workers apply for benefits, said:

“To create a Universal Credit account you need to have a computer or smartphone. We assume everyone has these devices, but it’s not the case. The people I have helped have to ask their housemates whether they can use their computers to create an account. Some of them also don’t understand how these devices work. With some people, especially older people, this can be quite daunting.”[71]

Once people create their account, they are provided with a list of web forms to complete, covering questions about their work and income history, financial assets, housing situation, health, and bank account information. Like the rest of the application, these forms are only available in English and Welsh. Alvarado, who was briefly on Universal Credit in 2018, said, “I found it quite hard when I did it [applied for the benefit]. It’s even harder to navigate the bureaucratic process in a foreign language.”[72]

Even people who are native English speakers can struggle to fill in these forms. Walters found the process “anxiety-inducing”:

“They want to know dates, times [of when you worked] and wages. These are not easy for me to recall … When you work for a big company, [this information] goes straight through and Universal Credit knows how much you earn.[73] But if it is an informal arrangement, normally you have to provide documentation of your wages to the Jobcentre [the DWP agency that monitors compliance with benefit rules]. When you work for a charity, you don’t always get these things. I don’t get pay slips very often.”

The next step is for people to verify their identity. The government sought to automate this process when it rolled out the GOV.UK Verify service in 2016, which outsources identity checks to third party providers.[74] Users of this service are required to upload evidence of their identity, such as a mobile phone bill, bank account details, or a picture of themselves.[75] The providers check this information against data they have collected (such as people’s credit histories) and passport and driver license data held by the government.[76]

The Verify service has proven unreliable for the majority of people applying for benefits. In March 2019, the NAO found that only 38 percent of people who apply for Universal Credit have been able to successfully verify their identity using the service.[77] Walters says that the demands of establishing the required online presence can be daunting. “Because everything is online, that’s harder … If I don’t pay the rent … [or] I don’t have my name on the council tax or the utility bills, I am a ‘no’ person. So where do I get [proof of] ID from?”

As the number of people applying for Universal Credit soared in March 2020, many complained that the Verify service was slow and unusable even though they had the appropriate identity documents.[78] To mitigate Verify’s failures, the government announced on April 16 that it would also allow people to confirm their identity using Government Gateway, an older verification service.[79]

People who are unable to verify their identity online are required to book an in-person interview at their local Jobcentre.[80] This alternative, however, can also prove challenging when the DWP’s computer systems struggle to register complex claims.

“Rick B.”, 58, an artist, recalled that he and his partner, “Esther B.,” had to submit proof of their identity on “four separate occasions” because of changes to their claim. Rick said:

“Each time they [the DWP] amended our claim, they had to go through the ID process again. When the claim changed from ESA [Employment Support Allowance] to Universal Credit, we needed to produce ID for that change. When I moved to a joint claim [with my partner], we had to submit ID again. They told us ESA works on a different computer system from Universal Credit, and that the computer was asking for our ID again.”[81]

Since Covid-19 lockdown restrictions began in March 2020, the DWP has replaced in-person interviews with identity verification checks over the phone. Child Poverty Action Group (CPAG), a charity dedicated to ending child poverty in the UK, has found that these checks involve only a “simple biographical questionnaire.”[82] It is unclear, however, whether the DWP will require people who have passed telephone checks to provide more proof of their identity later.

CPAG has urged the government to establish “less stringent or more flexible documentary requirements” to make it easier for people to verify their identity.[83] Citizens Advice, a network of charities that provides benefits advice in the UK, has also called on the government to step up support for people who struggle with obtaining identification because they “fac[e] instability in their lives, such as refugees or people seeking asylum, prison leavers, people affected by domestic violence or rough sleepers.”[84]

The Covid-19 lockdown has forced people who need help with their claim to rely on volunteer advisers and charity organizations over the phone. The lack of in-person support made it more difficult for some people to understand the advice they received. Ellen Gordon, also a benefits volunteer with IWGB, told Human Rights Watch that one of her clients struggled to follow her suggestions for retrieving her Universal Credit login credentials, forcing her to abandon her application. “She was quite anxious and confused,” Gordon said. “She really wanted to communicate but it was just difficult to understand if you are not used to using things like that.”[85]

Problems Managing Universal Credit

People who successfully apply for Universal Credit may struggle later with managing subsequent payments and other online administration. People on the benefit are expected to navigate updates to their claim and communications with their “Job Coach” (the DWP official assigned to individuals to oversee their claim) on their online account.[86] They are also required to submit evidence of their “Claimant Commitment” – job-seeking tasks assigned by the Job Coach – through an online journal.[87] The failure to provide evidence to the satisfaction of the Job Coach can lead to punitive reductions in social security payments (also known as sanctions).[88]

Father of four “George S.”, 53, told Human Rights Watch that he has been sanctioned for failing to keep up with these reporting requirements:

“I’ve been around the shops, industries to look for work and they [the DWP] say that’s not good enough. They said I have to go online. But I can’t go online if I can’t read or write … I have [submitted] my CVs in all places … it takes four to five hours to go to different places to get another job. But they say that’s not good enough and that I have to put it on the computer. I have been sanctioned three times because I can’t put it on the computer. When I go to the Jobcentre, you’ve got to wait two hours for the person [to help you with the computer] and two hours to go on the computer – that’s four hours.”[89]

He said that his Universal Credit payments were halved during the months he was sanctioned. George has 6-year old twins and two other children aged 11 and 14. “The sanctions affected the children … I can’t buy clothes for them or food. That’s why I come to the foodbank.”[90]

Some of the people Human Rights Watch interviewed also said these reporting requirements were onerous and intrusive. “They want a very graphic description of what you are doing to find work,” said “Mary G.”, 56, a resident of Stockton-on-Tees, “It’s a bit like Big Brother watching you to make sure you are doing all the work to find a job.”[91]

“It’s like having somebody watch your every single move,” said Walters. “You feel guilty if you go out for a coffee with somebody, because you think, oh no, I should be doing my job search.”[92]

On March 25, 2020, the government announced that it would not sanction people for failing to meet their Claimant Commitment during the Covid-19 pandemic, but the news did not reach some people receiving Universal Credit.[93] This announcement came straight after other key changes to benefit rules, such as an increase in the Universal Credit standard allowance, additional help with rent payments and for self-employed people, and the temporary suspension of all Jobcentre appointments.[94] These updates were announced online, in the mainstream media, and through people’s online journals. According to Tracey Herrington, project manager at Thrive Teeside, a social justice charity based in Stockton-on-Tees, these updates did not reach the people most affected by the new information, particularly those without internet access at home:

“People have not got access to the internet and have no money to put into their phone [to buy data], and libraries that provide free wifi are shut. They are not able to access their journal, so they don’t know that the government has stopped sanctions [for not meeting their Claimant Commitment]. The fear remains because they can’t get face-to-face contact. “I don’t know if what I’m doing is right,” they have told me. There is a lot of uncertainty from the claimants’ perspective.”[95]

On June 29, 2020, the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions announced in Parliament that the Department will “reinstate the need for a claimant commitment” and that sanctions would be re-imposed in July.[96] Again, it appears that this announcement did not reach some people, including those likely to be affected by the change in policy. On July 2, “Matthew T.,” 64, who lives in London and had recently applied for Universal Credit, told Human Rights Watch he was not aware that the DWP had reinstated the Claimant Commitment. He is unsure how he would look for work. “We are still coming out of lockdown. In a large population where the biggest concern is [the unemployment] of younger people, I won’t get a job at 64,” said Matthew.[97]

Outsourcing Digital Support

The government relies heavily on local government services and charities to support people who experience difficulties submitting their claim online. From 2017 and 2019, the DWP provided grants to Local Authorities to establish “Universal Support,” a service for people who need help with Universal Credit.[98] In 2019, the government provided Citizens Advice and Citizens Advice Scotland with £39 million to launch the “Help to Claim” service.[99]

This service connects people to advisers that help them assess whether they are eligible for Universal Credit, fill in their application, and prepare for their first appointment at their local Jobcentre.[100] This support does not continue past people’s first payment, but they can seek additional help at their local Citizens Advice depending on availability.

Although the “Help to Claim” service is providing critical support, the need remains overwhelming. “If you ever walk past [the local] Citizens Advice, every chair is taken,” said Herrington. “It then falls on the voluntary sector to pick up the pieces. We are providing resources we are not paid for. It’s a massive strain on small and vulnerable organizations.”[101]

The closure of public libraries and Jobcentres has also limited the number of free internet-enabled computers available to people who cannot afford internet access at home or on their phone. Budget cuts have forced 776 public libraries to close between 2010 and 2019,[102] while the DWP has closed 66 Jobcentres between 2017 and 2019.[103] The Huffington Post estimates that these cuts have led to the loss of at least 4,113 free internet-enabled computers.[104]

III. Waiting for Universal Credit

During his 2018 visit to the UK, the UN Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights also observed that Universal Credit is a “major automation project.”[105] While automation may have simplified the means testing process for the government, Human Rights Watch has found that it creates costly and agonizing delays for many people. People must wait for five weeks from the date of their application to receive their first payment due to the way the benefit is calculated.[106] In contrast, people on legacy benefits generally receive their first payment within two weeks.

Human Rights Watch has found that this delay creates financial hardship for people since they still have to meet their basic needs during the period they have to wait for assistance. This has forced many of them to resort to food banks, fall behind on their rent and bills, and take out loans that trigger vicious cycles of debt.

“Zach L.”, 31, a sales assistant in Newcastle with three children, told Human Rights Watch that the five-week wait has rendered his family financially unstable, adding: “Because I have to wait five weeks for the claim to be processed, [it] made us in debt and now [we] try to catch up over time … I’ve worked all my life and I am resorting to using the food bank today because of benefits that I am receiving. It’s not really a benefit is it, if I’m having to use this service?”[107]

The five-week wait worsened delays that Rick experienced while applying for benefits. In November 2019, he broke his foot and had to stop working. Around the same time, Esther, his partner, fell sick and also stopped working. When Rick tried to apply for Universal Credit in November, DWP staff wrongly advised him to apply for Employment Support Allowance, a legacy benefit. His claim was rejected, and he was subsequently placed on Universal Credit. However, he was not allowed to backdate his claim and waited until January 2020 for his first benefit payment. Rick said:

“We didn’t have income and had to borrow money off family and friends and credit cards. We had to go on a mortgage break … we are three months or so behind our mortgage payments. This constant fight for money to survive has made me depressed. I worked all my life … all I wanted was a few quid [pounds] to get by while I am on the mend. We have no savings to dip into … people have given us food. We get deliveries from food banks.”[108]

Borrowing from the government or third parties is a typical way of coping with the five-week wait. When people submit their claim online, they also have the option to apply for an advance on their first payment.[109]

If they accept the advance, however, they must repay it within 12 months, starting with their first payment.[110] Although many people that have applied for the benefit as a result of Covid-19 have declined advances for fear of falling into debt, a significant number of them still use this service.[111] From March 1 to June 23, 2020, the DWP’s data show that 32 percent of people applying for the benefit (slightly over 1 million people) received an advance.[112]

The government has resisted calls to suspend the recovery of advances to help people cope with the economic impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic.[113] At the time of writing, people are required to forgo 30 percent of their standard allowance every month until they repay their advance.[114] Although the government paused efforts to recover other government debts from benefit payments in April, this relief was short-lived, and it has resumed debt recovery at the time of writing.[115]

Nevertheless, the government has announced several measures to mitigate the impact of the five-week wait. Beginning July 22, 2020, people that move from employment, disability and housing benefits under the legacy system to Universal Credit are entitled to receive their old benefits for two weeks while they wait for their first payment.[116] But this “run-on” payment does not include support for childcare costs. People who are applying for benefits for the first time, or after a period where they have not claimed benefits, are also not eligible.

Other measures the government announced are a reduction of the rate of recovery for all government debts from 30 to 25 percent, and an extension of the repayment period for advances from 12 to 24 months.[117] However these changes will only go into effect in October 2021, even as people continue to suffer from the economic fallout caused by the pandemic.[118]

Even with these changes, debt-based reductions in Universal Credit payments can be substantial for people struggling to meet basic needs. Since the amount of money they receive is designed to precisely meet their needs, reducing that amount by 25 to 30 percent for debt repayment hampers people’s ability to support themselves. Darren Leighton from the anti-poverty community network Hartlepool Action Lab told Human Rights Watch:

“A lot of people living with poverty or an addiction can often find the idea of quick money very appealing. But they are in no position to repay the advance when it comes due and this will sometimes compound their issues. When you add up the recovery of court fines (which are an additional payment on top of sanctions and advance repayments), you have some people who are effectively living on £30 a week. Even those with the highest resilience to poverty aren’t able to live on that.”[119]

Debt advice groups have also raised concern that people are more likely to struggle to repay debt if they take advances.[120] Some people who had taken advances told Human Rights Watch that they had received debt enforcement notices from bailiffs informing them that they would visit their home to collect payment on debts owed to the government.[121] In April 2019, “Kate A.,” 18, received a debt enforcement notice that she believes was for the remainder of her first advance. “It really stressed me out,” said Kate, “I spent 4 ½ hours on the phone with debt management, pleading for them to sort it out.”[122]

In October 2019, Zach, 31, said he started having panic attacks after receiving a debt enforcement notice: “At the minute I’m out sick with depression. I’m suffering panic attacks and anxiety all because of this. I haven’t been myself for quite a long time now.”[123]

Advances issued to people while their claims are still being evaluated may also saddle them with significant debt relative to their benefits. Since Covid-19 lockdown restrictions were imposed in March 2020, “the government is processing new Universal Credit claims pretty quickly and giving out advances of up to £700 or £800,” said Tracey Herrington of Thrive. “But some of these claimants are unlikely to be eligible for Universal Credit based on their combined household income.”[124]

According to Thrive, at least three families they are helping have been unsuccessful with their application for the benefit and must now return the advances.[125] “People who have just kept their heads above water have now fallen below that,” said Herrington.[126]

More than 50 charities have joined The Trussell Trust, a network of food banks in the UK, to call on the government to end the five-week wait.[127] There are a few ways to achieve this. Human Rights Watch has proposed that the government make Universal Credit payments within the first few days of application, based on an estimate of people’s personal and financial circumstances. Under this scheme, the government should not recover or penalize any overpayment of the first payment.[128]

Alternatively, the government should convert advances into one-off, non-recoverable grants that include a cash component as well as vouchers redeemable at food retail outlets.[129] For people who are already repaying advances, several groups have called for the government to suspend repayments, at least for the duration of the Covid-19 pandemic.[130]

The DWP has responded that these adjustments would undermine its ability to automate Universal Credit. During the House of Commons Work and Pensions Committee hearing on April 23, 2020, Neil Couling, Senior Responsible Owner for Universal Credit, said that deferring the recovery of advances would force the DWP to “strip out the automation and put human beings on to doing … deferrals.”[131] This would force the DWP to “deautomat[e] the system and giv[e] humans a lot more new tasks to do” at the expense of “keeping the automation in the system and allowing the new claims to all get paid.”[132]

In effect, the government is arguing that automation should be continued, even if it is causing some people real economic hardship. But a social security system that prioritizes speed at the expense of the rights of the people harmed by automation is not fit for purpose.

The Work and Pensions Committee agreed, saying it was “astonished to hear that the Universal Credit system has been built in a way that makes it all but impossible for repayments of Advances to be suspended in a crisis situation,” urging the government to “review the Advances system … to make it more flexible.”[133]

Independent technical experts have also disputed the DWP’s claim that suspending the recovery of advances will curtail the benefits of automation. The technology and social justice charity medConfidential submitted evidence to Parliament showing that even in its current form, the Department has technical options at its disposal, such as setting a “flag” on people’s accounts, to suspend repayments.[134]

In any event, much about how the government automates Universal Credit calculations is unknown. On March 13, 2020, Human Rights Watch submitted a Freedom of Information request seeking information from the DWP on, among other things, “how the calculation of UC payments based on data stored on the [RTI system] is automated.”[135] On May 11, 2020, Human Rights Watch sent a follow-up e-mail to the DWP. On the same day, the DWP replied that it would respond to the request “as soon as practically possible,” but is “not able to provide a specific timescale.”[136] As of September 16, 2020, no reply had been received.

IV. Fluctuations in Universal Credit

Phil Booth, a technologist at medConfidential, has studied the technical design of Universal Credit. Booth told Human Rights Watch that the government’s emphasis on mimicking the world of work has created an automated system that serves the “ideal claimant” – one that is digitally literate and savvy enough to navigate a “hyper means-tested benefit.”[137] Booth said:

“The system houses this very narrow assumption of who it is trying to support … it’s a very cozy, comfortable picture of people who haven’t had to live on benefits. But the ideal claimant is not going to be the norm. When you build a system that idealizes the norm, you are creating problems because you are not dealing with the realities of people’s lives.”[138]

These decisions have created a rigidly automated system that is causing many people to suffer extreme fluctuations in their benefit, and some even to receive less money than they are entitled to. People interviewed by Human Rights Watch provided first-hand accounts of how a system designed around an “ideal” claimant could negatively impact the very different people who claim Universal Credit.

Impact on People with Monthly Wages

When a person applies for Universal Credit, they are automatically assigned a fixed monthly assessment period, a rolling one-month period that begins the date of their claim. Janet, 35, a single mother in London, was transferred from legacy benefits to Universal Credit on January 31, 2020. Her first monthly assessment period ran from January 31 to February 28.[139]

This assessment period defines the scope of earnings data that the DWP retrieves from the Real-Time Information system, the country’s tax management system, to calculate how much benefit someone is entitled to. As Janet’s employer pays her a regular wage on the last working day of each month, she received her January wages on January 31, and her February wages on February 28. As a result, the earnings data the Department retrieved from RTI to calculate her first payment included both sets of wages.

The earnings data that DWP obtains reveal how much people are paid and when they were paid, but not the period of work these amounts are meant to cover. This critical omission distorted the DWP’s calculation of Janet’s earnings. Since Janet received both her January and February wages within her first assessment period, the Department assumed that the income she earned that month was twice its usual amount.

Since Universal Credit payments are means tested, this design flaw caused Janet’s first payment to plunge to £388 – more than £1000 short of what she needed to pay the rent, her other bills, and support her two children, one of whom has a disability. When Janet saw her first payment, she said she had a panic attack.

She tried calling the Universal Credit helpline, but the agent on the line told her that her payment had been correctly calculated and offered her food bank vouchers. She submitted an appeal – known as a “Mandatory Reconsideration” – but ended up overdrawing on her bank account and borrowing money from friends to cope. “I am living on whatever I can find in my cupboard at the moment,” Janet told Human Rights Watch when we spoke to her in March. “I skip a meal so my children can eat and to ensure that the bills are paid.”[140]

The next Universal Credit payment she received, on April 6, was £2020. She was surprised and was not aware if this was the result of her appeal. “It’s such a random amount,” said Janet during a follow-up interview.[141]

It is likely that Janet’s second payment was so high because RTI did not record any wages paid during her second assessment period.[142] As a result, the DWP’s calculation of her second payment assumed that she had not earned any income that month.

Her third payment, on May 6, was £1406 – closer to what she believes is her true entitlement. While she is grateful that her payments seem to have stabilized, she is concerned the problem will recur. “I’m always on eggshells. I don’t know what’s around the corner, said Janet. “There’s no room for budgeting under Universal Credit.”[143]

These extreme fluctuations in Janet’s benefits are not a one-off error. The flawed inference that wages deposited into people’s bank accounts during any given assessment period is their true earnings for that month is embedded into the computer model uses to calculate Universal Credit payments nationwide.

If the DWP does not fix this flaw, it is all but certain that this fluctuation in Janet’s benefits – and others like her – will recur. The Court of Appeal projects that there are “many tens of thousands” of people like Janet who could see their payments fall dramatically one month and rise again several times a year.[144]

Court of Appeal Ruling

In 2018, Child Poverty Action Group and the law firm Leigh Day filed for judicial review against the DWP on behalf of four single mothers that shared Janet’s experience – extreme fluctuations in Universal Credit payments when DWP’s payment calculation algorithm detects two sets of monthly wages in one assessment period, and none the next.

This flawed computer model also caused them to receive less in benefits over time. Since the four mothers have childcare responsibilities, they are permitted to keep a portion of their earnings – known as a “work allowance” – before means-testing rules are applied.[145] The government implemented work allowances to “make clear to people that they will be better off in work.”[146]

The four mothers lost the allowance during those months that the DWP’s computer model detected no wages.[147] One of them, Danielle Johnson, testified that the loss of the work allowance several times in 2018 reduced her benefit entitlement by about £500 that year.[148] For her and her six-year old daughter, “that is a huge amount of money,” Johnson told the court. “I need that £500 to meet our minimum outgoings and to ensure that all of my daughter’s basic needs are met.”[149]

In January 2019, the High Court ruled in favor of the four mothers, but the government appealed.[150] During the Court of Appeal hearing, the government admitted that the problems the mothers experienced were “arbitrary,” “unfortunate,” and “challenging,” but insisted that the “bright lines” required to ensure the efficient automation of Universal Credit overrode these concerns.[151]

On June 22, 2020, the Court of Appeal rejected this reasoning, and ordered the DWP to fix the flawed computer model that created these problems.[152] The Court was not convinced that this design flaw was an “inevitable consequence” of automating the benefits system, or that fixing it would require manual intervention that would be too costly and burdensome for the government.[153] Instead, the Court said DWP had acted irrationally in refusing to “put in place a solution to this very specific problem,”[154] which was causing thousands of people “considerable hardship.”[155]

Though the court upheld people’s social security rights, they will not benefit until the DWP has figured out the best way to implement the Court’s ruling. On June 25 2020, the Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Welfare Delivery, Will Quince, told Parliament that the Department will not appeal the decision, and that it is “now assessing the remedial options.”[156] He however refused to provide a timeline for making design changes, claiming that the Court has not called for “immediate action.”[157]

In the meantime, the people affected by this design flaw will have to submit a Mandatory Reconsideration to get their payments corrected.[158] Reflecting on her experience, Janet said, “If I did not push back … who knows where I would be? It’s quite a shock to the system.”[159]

Impact on People with Non-Monthly Wages

Although the Court of Appeal does not address the plight of people with non-monthly wages, the High Court has ordered the government to also fix the flaw for people who are paid on a four-weekly basis.[160]

The High Court’s ruling shows that the design flaw affects a wide range of workers on different wage schedules. The DWP has also acknowledged that the flaw could affect people who receive weekly or fortnightly salaries.[161]

For example, people who are paid weekly could experience benefit fluctuations four times a year.[162] During these months, RTI earnings data for these people will register five sets of wages. As a result, the DWP’s computer model will incorrectly calculate their monthly earnings – and reduce the Universal Credit they are entitled to – based on wages that they received for five weeks’ worth of work.

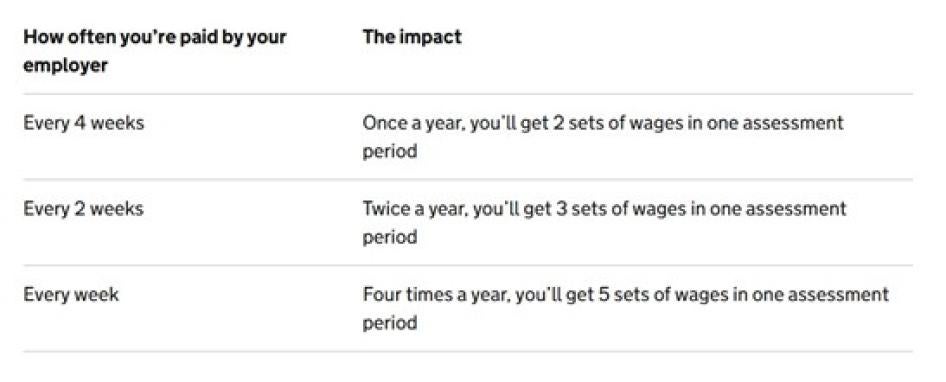

According to a 2018 study by the Resolution Foundation, over 40 percent of people on Universal Credit that it surveyed are paid weekly, fortnightly, or every four weeks.[163] The government’s own calculations show how often these fluctuations will affect people with non-monthly wages.[164]

Benefit fluctuations stemming from this rigidly automated system leads to various problems for people, including difficulties with personal or family budgeting and debt-related issues. In May 2019, “John S.”, 57, started working at a garden center in Newcastle after a period of illness. He is paid every four weeks. Shortly after he started work, he realized that the DWP had made significant reductions to some of his Universal Credit payments, because the system showed that he had received two sets of wages for those months. He rang the Universal Credit helpline to explain that the two sets of wages were for work done over an eight-week period, but to no avail. “You’re banging your head on a brick wall with Universal Credit,” he told Human Rights Watch.[165]

He said the lower-than-expected payment that month has forced him into rent arrears since October 2019. He is also behind on his Council tax and utility bills. “I like work … it gives me some pride,” said John, “But I just don’t understand how they work [the payments] out. Doesn’t make sense, does it? I am worse off going to work.”[166]

|

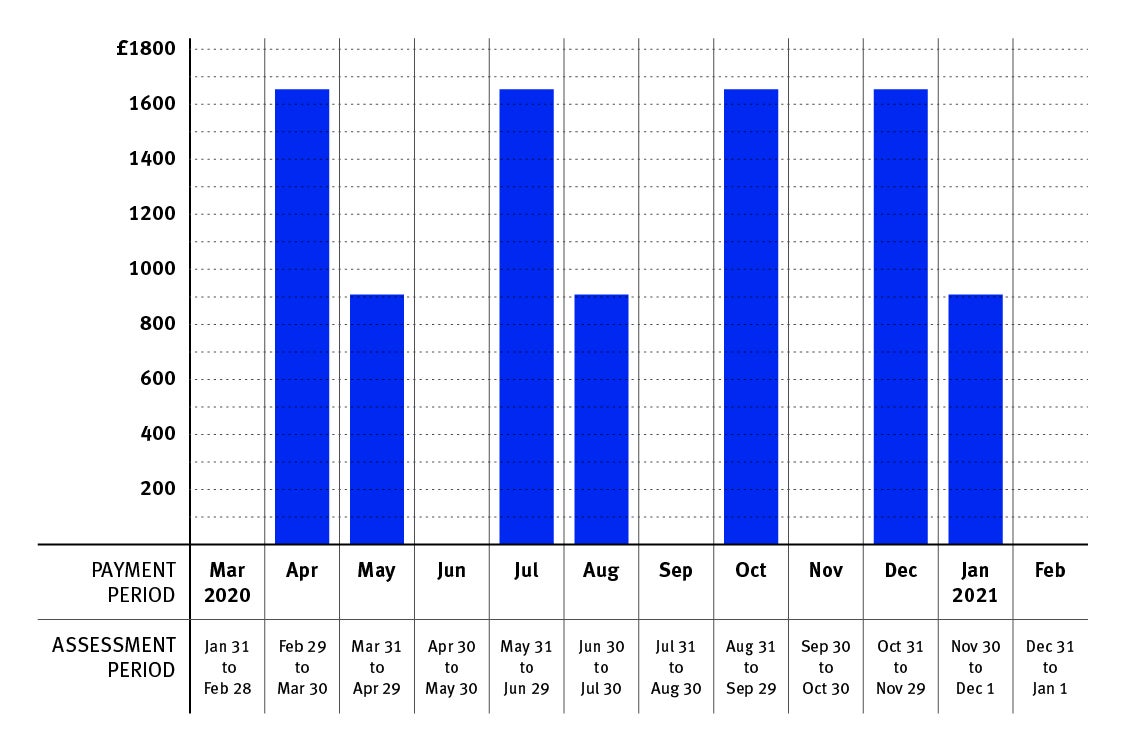

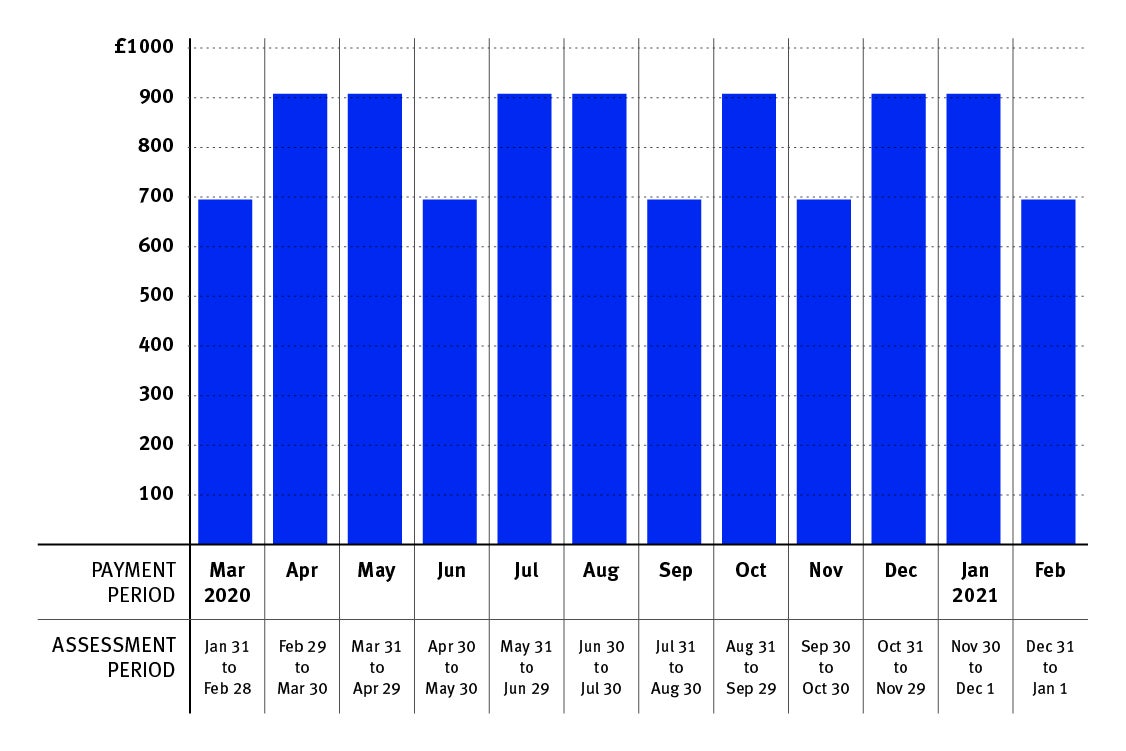

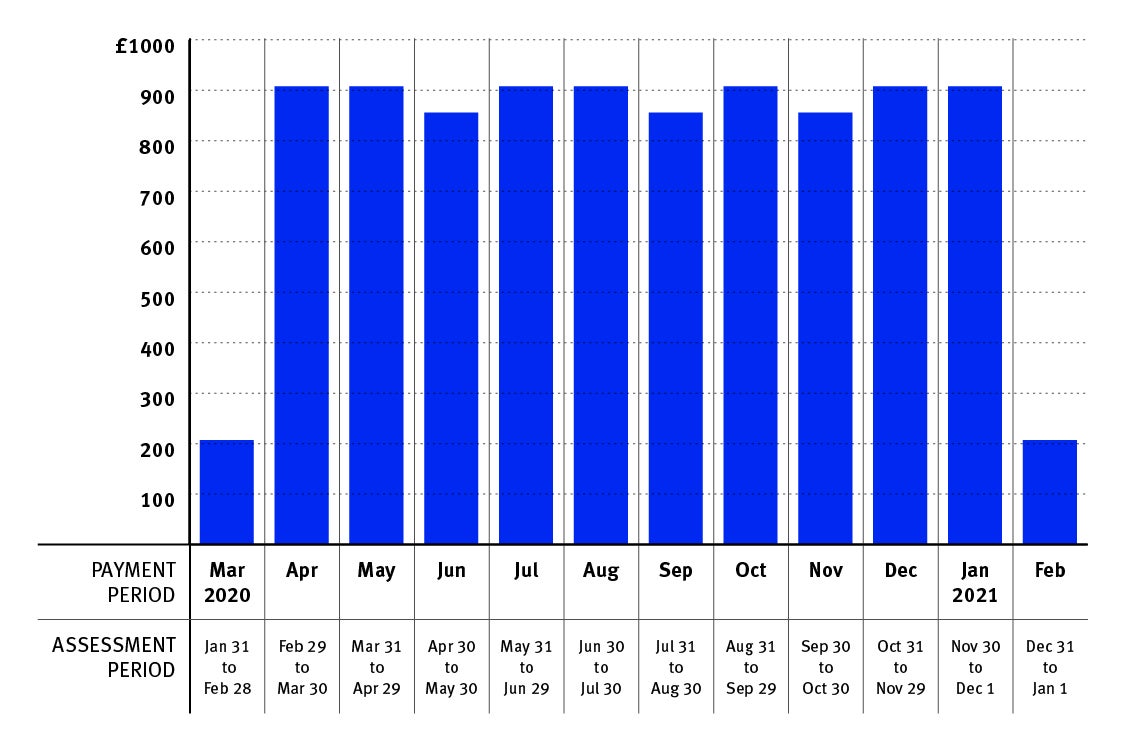

How Could Problems with the Automation of Universal Credit Affect Low-Income Households? To simulate how the flawed design of the monthly assessment period might affect a family of four, Human Rights Watch used a forecasting tool that Ferret Information Systems developed to illustrate how people’s awards might fluctuate when they are on different salary frequencies.[167] This simulation draws on case data provided by Ferret where both partners work 35 hours and 10 hours a week respectively on National Minimum Wage, drawing a net monthly household income of £1472.[168] Assuming that they also pay £650 in monthly rent, Ferret projects that they will be entitled to approximately £908 in Universal Credit. In all three scenarios below, Human Rights Watch assumes that the partners have submitted a joint claim for Universal Credit on January 31, 2020. Their employers also paid them their salaries on January 31. There are no changes in the family’s income or circumstances from month to month. This simulation is for illustrative purposes only, and should not be taken to constitute benefits advice.

If both partners are paid monthly on the last banking day of each month, this is how their Universal Credit might fluctuate:

If both partners are paid weekly, this is how their Universal Credit might fluctuate:

If the partner working thirty-five hours is paid every four weeks, and the partner working ten hours is paid weekly, this is how their Universal Credit might fluctuate:  |

Impact on People who Have Just Lost Their Jobs

Since Universal Credit payments are calculated based on people’s financial circumstances in the month prior to when they are paid, people stand to lose critical support at a time when they need it most – just after they lose their jobs. If people apply for the benefit before they receive their last paycheck, the system will calculate their first payment as if they were still receiving their regular wages.

“If you lose your job, your intuition is to apply for Universal Credit as quickly as possible, said Stephen Mitchinson, 26, a benefits adviser with Citizens Advice Bureau Newcastle. “But once you apply, it triggers the monthly assessment period. If your last wages are paid within the assessment period, that is counted against the amount you receive.”[169] People may also be deemed ineligible for the benefit if their last wages are above the maximum income threshold.

An unexpected reduction in her first Universal Credit payment startled “Mary G.,” 56, a resident of Stockton-on-Tees. She was no longer working by the time she filed her claim in September 2019, and expected to receive the standard allowance in full. However, her first payment was reduced to reflect her last paycheck, which she received during her assessment period. “I felt like I’ve been shortchanged a week’s money through no fault of my own, said Mary. “I was angry – it hadn’t been explained properly that this could happen.”[170]

Impact on Workers with Volatile Income