Summary

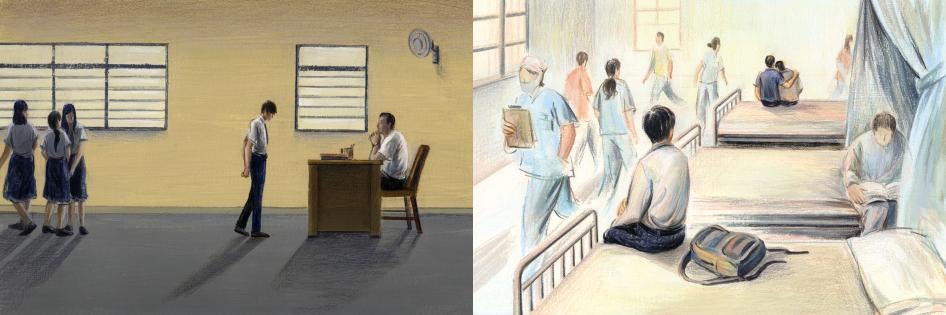

Sexual and gender minority children and young adults in Vietnam face stigma and discrimination at home and at school. While in recent years the Vietnamese government has made significant pledges to recognize the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people, tangible progress has lagged behind the promises, and these policy gaps are felt acutely by young people.

In 2016, while serving on the United Nations Human Rights Council, Vietnam voted in favor of a resolution on protection against violence and discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI). The delegation made a statement of their support before the vote, saying: “The reason for Vietnam’s yes vote lay in changes both in domestic as well as international policy with respect to LGBT rights.”

Perhaps the most impactful legal changes include updates in 2014 to the Marriage and Family law, and in 2015 to the Civil Code. In 2014, the National Assembly removed same-sex unions from a list of forbidden relationships; however, the update did not allow for legal recognition of same-sex relationships. In 2015, the National Assembly updated the Civil Code to remove the prohibition in law that prevented transgender people from changing their legal gender; however, it did not provide for a transparent and accessible procedure for changing one’s legal gender.

And while such statements and changes suggest a promising future for LGBT people in Vietnam, significant challenges persist. The government is both well-positioned and obligated to address these issues.

Inaccurate information about sexual orientation and gender identity is pervasive in Vietnam. Some of that is rooted in schools. Vietnam’s sex education policies and practices fall short of international standards and do not include mandatory discussion of sexual orientation and gender identity. The central curriculum for schools is also silent on LGBT issues. While some teachers and schools take it upon themselves to include such lessons, the lack of national-level inclusion leaves the majority of students in Vietnam without the basic facts about sexual orientation and gender identity.

That omission is proving to be harmful. As this report documents, youth are acutely aware of the pervasive belief that same-sex attraction is a diagnosable mental health condition. The failure of the Vietnamese government to counter this false information has let it continue unabated. This widespread belief had significant impact on the lives of young LGBT people Human Rights Watch interviewed, ranging from serving as the root of harassment and discrimination, to parents bringing their queer children to mental health professionals in search of a cure. Even youth who would eventually identify themselves as queer acknowledged that they grew up on stereotypes and misinformation about themselves and others. In some cases, these misunderstandings fueled antipathy and even violence against LGBT people.

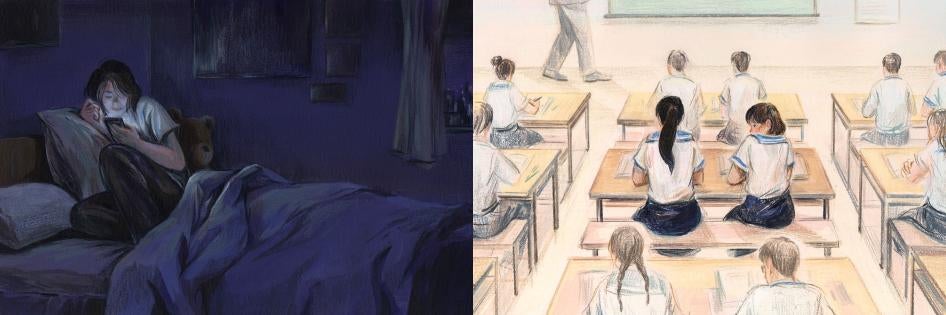

Facing a void in official sources of information, Vietnamese youth seek affirming and accurate information about sexual orientation and gender identity elsewhere. Some students recounted how they searched for information from informal sources—in particular, by searching and browsing the internet. But while the discovery of affirmative information in this way can be encouraging, it is not sufficient and not even available to many Vietnamese youth.

Verbal harassment of LGBT students is common in Vietnamese schools. Students in different types of schools—rural and urban, public and private—told us many students and teachers use derogatory words to refer to LGBT people, sometimes targeted at them and coupled with threats of violence. Other studies, including research by United Nations agencies and Vietnamese groups, have confirmed this finding.

While it appears to occur less commonly, some LGBT youth report physical violence as well. For example, one interviewee said: “[The bullying] was mostly verbal but there was one time when I was beat up by five or six guys in eighth grade—just because they didn’t like how I looked.” What is similar between the cases of verbal and physical abuse is the lack of consistent response from school staff, and the lack of confidence among students that there are mechanisms in place to address cases of violence and discrimination.

The majority of the LGBT youth Human Rights Watch interviewed who had experienced bullying at school said they did not feel comfortable reporting it to school staff. This was sometimes because of overt, prejudiced behavior by the staff; in other cases, students operated on the assumption that it was unsafe to turn to the adults around them for help.

And even in cases where students did not face verbal or physical abuse, many reported that their families, peers, and teachers implicitly and explicitly enforce heterosexual and cisgender social norms. This occurs in classrooms where teachers refer to anything other than a procreative heterosexual relationship as “unnatural” as well as when parents threaten their children with violence, expulsion, or medical treatment if they turn out to be gay or lesbian.

LGBT youth who face bullying and exclusion at school suffer a range of negative impacts. As documented in this report, they feel stressed due to the bullying and harassment they experience, and the stress affects their ability to study. Some students said the bullying they faced due to their sexual orientation or gender identity led them to skip or stay home from school.

In contrast, LGBT youth who reported receiving affirming, accurate information about sexual orientation and gender identity in school, or support from their peers or teachers, said the experience was edifying. It encouraged them to attend school more regularly and defend themselves in instances of misinformation or harassment. And students who felt more informed also reported that knowing the truth about sexual orientation and gender identity—namely, that neither was a “mental disorder”—strengthened their ability to prevent discrimination and violence against themselves.

LGBT youth are not alone in noticing and pushing back against their ill-treatment. Parents of some LGBT youth have begun to take up the mantle of diversity and inclusion activism as well, organizing outreach seminars across the country, and volunteering to counsel fellow parents who were raised in an education system that taught them homosexuality was an illness.

During an artistic event as part of Hanoi Pride 2019, a group of activists and artists presented an exhibition exploring queer history in Vietnam through various derogatory words that have been reclaimed by the community over the years. The organizers hoped that “society will have a better insight, so that when we use those words, we understand them.” The exhibition highlighted a simple and important mission: to break down some fundamental misunderstandings that underscore human rights violations against LGBT people—and youth in particular—in Vietnam today.

The Vietnamese government has several laws that prohibit discrimination and uphold the right to education for all children. The government’s stated alignment with a global shift toward respecting the rights of LGBT people signals some political will to make the necessary changes to genuinely include everyone, regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity, in education institutions and the rest of society. The first steps will include correcting the persistent widespread notion that homosexuality is an illness and needs a cure.

Recommendations

To the National Assembly

- Revise the 2006 Law on Gender Equality to include specific protections for gender identity and expression.

- Revise the Law on Marriage and Family to allow same-sex couples to be legally recognized.

- Ratify the UNESCO Convention Against Discrimination in Education.

To the Ministry of Education and Training

- Promote and implement guidelines for teaching comprehensive sexuality education in line with international standards.

- Sign UNESCO’s Call for Action on homophobic and transphobic violence to signal the ministry’s commitment to policy reform to protect LGBT students.

- Clarify that the 2018 directive on school counselors issued by the ministry is inclusive of LGBT students and mandate that implementation of the directive include training on sexual orientation and gender identity.

- Immediately provide mandatory short-term training for all teachers on gender and sexuality, including sexual health, and accurate information on sexual orientation and gender identity.

- Issue a directive instructing schools on specific measures to take to prevent and combat harassment and discrimination in school.

- Include modules on sexual orientation, gender identity, and human rights in the curriculum for pedagogical colleges and universities.

To the Ministry of Health

- Formally recognize, in line with World Health Organization Standards, that having same-sex sexual attraction is not a diagnosable mental health condition.

- Issue a directive that all curricular materials at all levels of medical education, including for mental health professionals, be adjusted to acknowledge that same-sex attraction is a natural variation of human behavior.

- Formally adopt the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases version 11, including with specific attention to the new sexual health chapter, which updates the diagnostic standards for transgender people.

To the Ministry of Foreign Affairs

- Counsel the government to invite the United Nations independent expert on protection against violence and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity to visit Vietnam and consult on the government’s LGBT rights progress and next steps.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch staff and a consultant conducted the research for this report between May 2018 and March 2019 in Vietnam.

Researchers conducted 59 interviews, including 12 with children under age 18 identified as sexual or gender minorities; 40 with sexual and gender minorities ages 18-23 about their experiences as children; and 7 with teachers, other school staff, and parents.

Under Vietnamese law people are considered adults at age 16. However, for the purposes of this report, Human Rights Watch considers anyone under the age of 18 a child, in line with the definition of “child” in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.[1] The Committee on the Rights of the Child, the UN authority that monitors states’ compliance with the convention, has called on Vietnam to amend its legislation in line with international standards.[2]

No compensation was paid to interviewees. Human Rights Watch reimbursed public transportation fares for interviewees who traveled to meet researchers in safe, discreet locations. Some interviews were conducted in Vietnamese with simultaneous English interpretation; others were conducted in English; others were conducted by a Vietnamese speaker and then the transcripts were translated into English. All interviews with people who experienced bullying in school were conducted privately, with participants interviewed one at a time.

Human Rights Watch researchers obtained oral informed consent from all interview participants, and provided written explanations in Vietnamese and English about the objectives of the research and how interviewees’ accounts would be used in this report and other related materials. Interviewees were informed that they could stop the interview at any time or decline to answer any questions they did not feel comfortable answering.

In this report, pseudonyms are used for all interviewees. Other identifying information such as the location where interviewees lived or attended school, or the name of the school, has been deliberately excluded to protect the privacy of those we interviewed. Interviewees attended a mix of public and private schools, and some switched between the two systems. While the majority of youth interviewees had grown up and attended school in the urban centers of Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City, Can Tho, Hai Phong, or Da Nang, 16 of the youth interviewed for this report attended at least part of secondary or high school in other, rural provinces. These included Bac Giang, Hai Duong, Dong Nai, Ha Giang, Vung Tau, Thanh Hoa, Lao Cai, Nam Dinh, Quang Ninh, Hung Yen, Quang Ngai, Kien Giang, and Thai Binh.

I. Young and Queer in Vietnam

I didn’t feel safe at my school. Before I came out, my classmates didn’t know because I’m good at hiding. And I knew I would get picked on a lot when I come out, but I decided to do it anyway because it was so uncomfortable not being myself and not living with my true gender.

—Khanh, 22-year-old trans man, January 2019

Children and young adults Human Rights Watch interviewed for this report told us about their childhood attempts to express themselves, stay safe, and access information when they began feeling different and learning about their sexual orientation and gender identity.

Nearly everyone interviewed said they began to question and explore either their own gender or their romantic attraction to people of the same gender when they were children; some said that they knew they were not cisgender or heterosexual when they were as young as 4 years old. For most, the primary struggle, they explained, was not coming to terms with being different as such, but rather searching for information about gender and sexuality against a steady tide of stereotypes, misinformation, and anti-LGBT rhetoric.

In the rare cases when teachers or other school staff were supportive of LGBT students, such supportive behaviors relied on the initiative of individual staff members rather than policies or protocols. In the majority of cases Human Rights Watch documented, school staff either appeared to avoid discussions of sexual orientation and gender identity, or propagated incorrect and stigmatizing information, such as by saying that homosexuality is a “mental illness.”

iSEE, a Vietnamese nongovernmental organization (NGO) that works on LGBT rights, found in a 2015 survey of more than 2,300 LGBT people that of those who attended school, two-thirds had witnessed anti-LGBT comments from their peers, and one-third had witnessed the same behavior from school staff.[3] A 2012 study by CCIHP, another Vietnamese NGO, found that over 40 percent of LGBT youth respondents—with an average age of 12 years—experienced violence and discrimination in school.[4]

LGBT Rights in Vietnam

Historically, sexual orientation and gender identity have received little official attention in Vietnamese laws and policies.[5] Civil society advocacy over the past decade has resulted in significant gains in terms of visibility and achievements in terms of LGBT rights.[6]

In recent years, the Vietnamese government has taken significant strides to recognize the rights of LGBT people. Perhaps the most impactful legal changes include updates in 2014 to the Marriage and Family law, and in 2015 to the Civil Code.

Prior to the late 1990s, Vietnam’s law had mentioned “husband and wife” but did not specifically rule out the existence of same-sex couples. Following two well-publicized same-sex wedding ceremonies in 1997 and 1998, Vietnam’s National Assembly amended the Marriage and Family Law in 2000 to specifically outlaw same-sex wedding ceremonies.[7]

Largely thanks to a civil society-led LGBT rights movement, public opinion has evolved gradually as well. In 2010, an 18-year-old wrote a public letter posted on the state-run Tuoi Tre website discussing his pain at being rejected by his parents when they found out he was gay. The newspaper responded to the outpouring of support by running a question-and-answer piece with the head of the Department of Psychology at Ho Chi Minh City University of Pedagogy, Dr. Huynh Van Son. “Think of homosexuality as a normal matter,” Dr. Son told readers.[8] In 2012, activists organized the first LGBT pride march.[9] Since then, pop culture has opened up as well, including in television programs such as “Listen To Rainbow Talk,” “Come Out,” and “LoveWins.”

In 2013, the Vietnamese government reversed course and removed same-sex unions from the list of forbidden relationships; however, the update did not go so far as to allow for legal recognition of same-sex relationships. [10] In 2015, the National Assembly updated the Civil Code to make it no longer illegal for transgender people to change their first name and legal gender; however, the revisions did not go so far as to implement a legal gender recognition procedure.[11]

In 2016, while serving on the UN Human Rights Council, Vietnam voted in favor of a resolution on protection against violence and discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI). The delegation made a statement of their support before the vote, saying: “The reason for Vietnam’s yes vote lay in changes both in domestic as well as international policy with respect to LGBT rights” and “Vietnam welcomes the initiative and efforts of members of international community to prevent and combat violence and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity.”[12] The resolution appointed the first ever UN Independent Expert on SOGI, Professor Vitit Muntarbhorn from Thailand.

Other government officials have made public statements in support of basic rights for LGBT people. This includes when Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung, in August 2015, said: “Same-sex marriage is not only a social issue in Vietnam, but is also of global concern, so it should be discussed properly and carefully.”[13] Minister of Justice Ha Hung Cuong and Minister of Health Nguyen Thi Kim Tien publicly supported the proposal to recognize relationships of same-sex couples.[14]

However, while there has been some tangible progress, the lack of protections and proactive programming for LGBT people in Vietnam, as documented in this report, is felt particularly acutely by youth. In a 2017 report analyzing the legal context for LGBT people in Vietnam, iSEE noted that government legal aid and counseling services are lacking, leaving LGBT people in Vietnam to seek unofficial advice from NGOs.[15] What is more, iSEE notes, only one-third of LGBT adults report they even know where to seek advice and redress when their rights have been violated.[16]

Social acceptance has also enjoyed a boost in recent years. In 2013-14, a social media campaign called “Toi Dong Y” (“I Do”) featured more than 53,000 individuals posting photos of themselves in support of same-sex marriage.[17] When, during an episode of Vietnam’s version of The Bachelor in 2018, two women left the show as a couple instead of with the leading man, audiences were largely unfazed.[18]

During Hanoi Pride 2019, a group of activists and artists presented “From Fag to Fab,” an exhibition exploring the evolution of Vietnam’s LGBT community through language. “Our community has come so far, we thrived through all the hatred and discrimination pointed at us,” organizers wrote in the anthology accompanying the exhibit.[19] The objective was to unpack the various terms that have been used as insults and also reclaimed by queer communities over the years. The organizers hoped that “society will have a better insight, so that when we use those words, we understand them.” It is a simple mission but an important one. As documented in this report, factual misunderstandings and negative stereotypes are helping to fuel pervasive human rights abuses against LGBT people in Vietnam today.

Misinformation About Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

I went online. I also made friends in the LGBT community and asked questions that were on my mind. I was excited to know new information and I gradually realized that it was not a disease.

—Sinh, a 23-year-old bisexual man, September 2018

The belief that same-sex attraction is a diagnosable, treatable, and curable mental health condition is pervasive in Vietnam. This false belief is rooted in the failure of the government and medical professional associations to effectively communicate the truth: that same-sex attraction is a natural variation of human experience.

Researchers have explained how Vietnam never officially adopted the position of the World Health Organization (WHO), which introduced a diagnosis for homosexuality in 1969, and therefore the government has never officially removed the diagnosis, as many around the world did when the WHO declassified it in 1990. However, while such a diagnosis appears to have never officially been on the books in Vietnam, the government’s treatment of homosexuality as deviant behavior, combined with public figures in medicine perpetuating the pathological construal, has resulted in the belief being widespread and potent. Anthropologist Natalie Newton, who studied queer culture and right movements in Vietnam, explained:

The general phenomenon of medicalization of homosexuality in Vietnam is not different from the West or other parts of the world. However, the ways in which the medical establishment, State, and NGO projects compete with one another in debates over homosexuality are particular to Vietnam’s contemporary historical context…[20]

Newton explains how a series of legal regimes beginning in the 1950s cast homosexuality as a “social evil,” and that popular Vietnamese media often use the concept “mitigate social norms by proxy.” According to Newton, “‘Social evils’ is a broad term that the State and local authorities have historically molded and shaped into tools for social disciplining across sectors, including homosexuality.” She writes:

Currently, debates around the medical and psychological diagnoses of homosexuality as an illness remain at the level of colloquial and media discussion. The Vietnamese medical or psychological establishments have not adopted the World Health Organization’s international declassification of homosexuality as a mental illness.[21]

Newton’s research documents how public figures ranging from poets to psychologists perpetuate the notion that homosexuality is a pathology. The fact that Vietnamese health professional associations and the ministry of health remain silent on this matter allows the discourse of disease to dominate. It leaves parents and teachers misinformed and ill-equipped, and youth with questions about sexual orientation and gender identity isolated and facing significant barriers to accessing accurate information.

When LGBT students face hostility in their homes and peer groups, access to affirming information and resources is vitally important. Few of the LGBT students we interviewed, however, felt that their schools provided adequate access to information and resources about sexual orientation, gender identity, and being LGBT.

In order to understand their own sexuality and to make responsible choices, LGBT students, as well as other students, need access to information about sexuality that is non-judgmental and takes into account the full range of human sexuality. This is particularly important in sexuality education courses. In recent years, many countries have moved toward providing comprehensive sexuality education.[22] According to the UNESCO International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education, comprehensive sexuality education is a “curriculum-based process of teaching and learning about the cognitive, emotional, physical and social aspects of sexuality. It aims to equip children and young people with knowledge, skills, attitudes and values that will empower them to: realize their health, well-being and dignity; develop respectful social and sexual relationships; consider how their choices affect their own well-being and that of others; and, understand and ensure the protection of their rights throughout their lives”.[23] As part of comprehensive sexuality education, all students, regardless of their sexual orientation or gender identity, should have access to relevant material about their development, relationships, and safer sex.

Vietnam’s Education Development Strategic Plan (2009 – 2020) calls for a revision of the curriculum to include components on “civic education, life skills, sexual health, gender, and HIV & AIDS education.”[24] However, inaccurate information about sexual orientation and gender identity is pervasive in Vietnam. In a 2014 report on LGBT rights in Vietnam, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) noted:

[E]ducation institutions are not safe for LGBT students due to the lack of anti-bullying and non-discrimination policies. Furthermore, sex and SOGI education is still limited in Viet Nam and are considered sensitive topics that teachers usually avoid.[25]

Four United Nations agencies —UNAIDS, UNESCO, UNFPA, and UNICEF— supported the Ministry of Education and Training in the development of technical guidance for incorporating comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) into pre-primary, primary and secondary education programs. The technical guidance was finished in November 2019. Sexual orientation and gender identity have been incorporated in the guidance, which the Ministry of Education and Training is charged with implementing. Human Rights Watch wrote to the ministry (see appendix 2) seeking information on plans for the new curriculum and confirmation that it would include LGBT content, but had not received a response at time of writing.

The evidence presented in this report aligns with UNDP’s 2014 report regarding the current state of CSE in Vietnam and underscores the urgency of the reforms underway. For youth who have questions about gender and sexuality—including questions about important sexual health issues—this can mean they are left searching the internet on their own rather than relying on vetted, scientifically reliable resources.

For example, Đức, a 22-year-old gay man in Hanoi, told Human Rights Watch how he first heard about homosexuality in school: “One time in biology class in 9th grade, we were studying gender and the teacher mentioned homosexuality, saying that it was unnatural and that we should be afraid of it—using derogatory words.”[26] A few weeks before that lesson, Đức said, he had seen a film that featured a gay character, prompting him to research homosexuality online. This process helped him begin to understand his own feelings and inoculated him against the teacher’s comments. “I had already done research on LGBT and knew it was a natural orientation, not a disease. So when my teacher said that, I just let it go—I thought it was just her lack of information, or her having the wrong information,” he said. [27]

Đức’s teachers suspected he was gay, he believes, due to his behavior and mannerisms. But even when another teacher tried to speak in Đức’s defense, her statements showed a lack of awareness and communicated a potentially harmful message: “When the head teacher responsible for my class was talking to us at the end of the week, she told the students not to ridicule me,” he said. The teacher explained to the group that they should leave Đức alone, “because based on what was taught in biology class they know that there are people like that [homosexuals] and they can change one day.”[28]

|

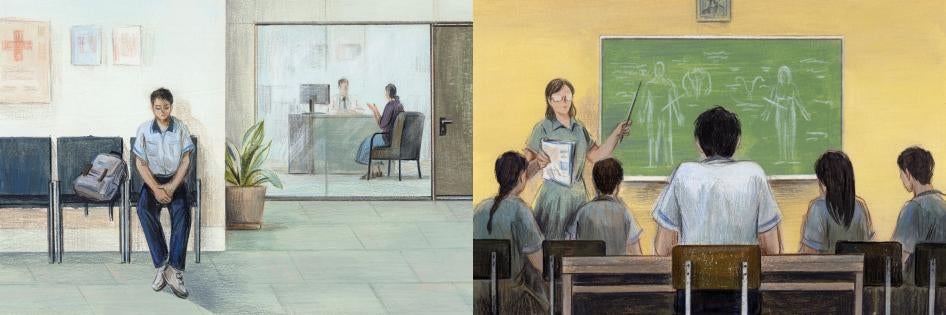

Resource Constraints and Teacher Training Deficits One obstacle to improving conditions for LGBT students in Vietnamese schools lies in the lack of teachers and counselors with the training necessary to provide appropriate support to LGBT students, in part a reflection of broader school resource constraints. In its 2012 review, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child noted with concern “low teacher capacity” in Vietnamese schools.[29] In a 2016 report on education, UNICEF and the Vietnamese Ministry of Labor, Invalids, and Social Welfare noted that while student/teacher ratios had dropped across most of the country, most teachers—in particular in rural areas—remained overwhelmed and undertrained for the various tasks they were charged with. The report said: Vietnam is also actively working to reduce student/teacher ratios to enable teachers to pay more individual attention to students, however, the application of new teaching methods is limited as the teacher training curriculum in colleges and universities has not focused on education renovation. Teachers lacking relevant knowledge and skills to deliver quality sessions are not able to positively impact student performance.[30] One particularly acute gap is that of school counselors. In recent years, surveys have shown a lack of confidence among students in school counseling services where they do exist.[31] Other studies have highlighted the shortage in trained school counselors—in particular when it comes to dealing with minority students and youth with mental health conditions.[32] A 2017 circular from the Ministry of Education and Training noted that school counselor/adviser positions are staffed by part-time teachers who are by and large overwhelmed; in a school week comprising 28 class periods, the individual is allotted three or four class periods to serve as counselor.[33] UNICEF and the labor ministry highlighted the government’s responsibility to enable and empower teachers: “[R]esources need to be assigned to assist the development of school based social workers and/or counsellors’ networks, and support for teachers in child protection and care to minimize violence against children in schools.”[34] |

Teachers Propagating Incorrect Information

I’ve never been taught about LGBT…. There are very few people who think that this is normal.

—Tuyen, a 20-year-old bisexual woman, January 2019

Đức’s experience, outlined in the previous chapter, is not unique. Of the 52 children and young adults Human Rights Watch interviewed, 40 reported that they heard negative remarks about LGBT people from their teachers. The most frequent comments centered around construing homosexuality as a “mental illness.” And, like in Đức’s case, even when school staff were attempting to be compassionate or supportive, they often did so on the basis of same-sex attraction being a treatable condition or an aberration rather than a natural variation.

For example, Tuyết, an 18-year-old bisexual woman, said: “My high school teachers said bad things about LGBT people. During a class to educate us about family and marriage, the teacher said, ‘Homosexuality is an illness and it’s very bad.’”[35] Quân, an 18-year-old gay man, told Human Rights Watch that his high school biology teacher told the class that “being LGBT is a disease” and “LGBT people need to go to the doctor and get female hormone injection.” Quân said the teacher told a personal story about it: “He would mention this issue over and over, because he had two kids at home, and near his house there was this boy who liked dressing in girl clothes.”[36] He said the teacher told the story in a way that suggested his children needed to be protected from such people.

Others told Human Rights Watch variations of the same story. Most often, it was the biology teacher telling students that homosexuality was unnatural or a disease. “One time in biology class in 9th grade, we were studying gender and the teacher mentioned homosexuality, saying that it was unnatural and that we should be afraid of it, using derogatory words,” said Giang, 22.[37] Sinh, 23, said, “My biology teacher said that love can only happen between men and women. Only men and women can create a good family because they can reproduce.”[38]

But such comments were not limited to the biology classroom. One student reported that his sociology teacher said, “There are homosexuals and they follow a trend of being gay.”[39] Phuong, a 17-year-old student, explained:

The chemistry teacher didn’t seem to like LGBT people. She said with my class that there was a student who was gay in another class, and she didn’t understand why they are being like that.[40]

As in Đức’s experience, tolerance from school staff was often coupled with factual misconceptions about the nature of same-sex attraction. Tui, 17, told Human Rights Watch: “[The teachers] say find a way to cure it, to get rid of it. But the silver lining is if you try hard enough and it still stays, it’s ok—but be ashamed.”[41]

While this report focuses on the experiences of students in Vietnamese schools and Human Rights Watch did not endeavor to document the perspectives of teachers, one teacher, Hoa, a 20-year veteran high school biology teacher, was interviewed on the topic. He confirmed for Human Rights Watch that LGBT issues are not included in the curriculum at his school. He explained:

LGBT issues are still considered sensitive. It can be integrated into other subject such as Biology or Civic Education. But it would require proper understanding of sexual orientation and gender identity, and most teachers don’t have that, so they tend to avoid the subject altogether.[42]

Hoa also said that when he talks with fellow teachers, “some of them still consider LGBT as a disease or an abnormal thing” which “leads to them not knowing how to treat LGBT students.”[43] Without training teachers about LGBT identities and issues, stereotypes and misinformation spread unchecked.

Same-sex attraction is shrouded in silence, as interviews with students confirmed. For example, Tham, a 17-year-old student who told Human Rights Watch none of his teachers ever mentioned sexual orientation or gender identity, recounted:

In grade nine, we had to give a presentation about love and relationships in Civic Education class. The teacher told us explicitly that we could only give presentations on love between men and women, not any other kind of love.[44]

Information Void in Official Sources

It took me more than one hour to explain to [the counselor at my school] about LGBT. If these [counselors] already knew about LGBT, it would be much better and they would be able to help many more people.

—Ngoc, 22-year-old transgender man, February 2019

Children have a right to access information, including information about gender and sexuality. UN treaty bodies have repeatedly discussed the importance of accurate and inclusive sex education and information as a means of ensuring the right to health because it contributes to reducing rates of maternal mortality, abortion, adolescent pregnancies, and sexually transmitted infections, including HIV.

Placing restrictions on health-related information, including information relating to sexual orientation and gender identity, can violate fundamental rights guaranteed by international law. These violations include the right to seek, receive, and impart information and ideas of all kinds, and the right to the highest attainable standard of health.

In its 2014 report, UNDP wrote:

Even when lessons on sex are included, they are usually put at the very end of textbooks and ignored by educators. Students are thus not taught about SOGI or to respect diversity. LGBT students at most schools are not provided with fundamental knowledge or support on SOGI issues either by their teachers or by school services such as school counselors and nurses, or through other resources.[45]

Students Human Rights Watch interviewed were acutely concerned about the lack of information about sexual orientation and gender identity in their textbooks. “Back in secondary and high school, I never heard about SOGI from the teachers,” said Hang, 22.

“There was no sexual education. In biology class we just learned what was in the book. The teachers never mentioned LGBT.”[46]

Minh, 23, explained:

In biology class there was no mention of LGBT in the textbook. So if the teacher decided to bring this up, they do it on their own. If they choose to teach about sex at all, that’s already revolutionary.[47]

In a 2014 public health study that surveyed over 1,600 Vietnamese high school students about their sources of sexual knowledge, researchers found that “although many participants believed that they were knowledgeable about sex, only a small number of them actually possessed accurate sexual knowledge.”[48] iSEE has documented cases in which teachers pressured students to remove scientific information about sexuality from classroom presentations because, as one teacher said, “this would encourage her students to be homosexuals.”[49]

Vietnam’s sex education policies and practices fall short of the approach recommended by the UN special rapporteur on education, the treaty bodies, and UNICEF, particularly when it comes to including information about sexual orientation and gender identity.

Understandings of Homosexuality as a Mental Health Condition

There’s a lot of pressure on kids to be straight. It’s constantly referenced that being attracted to someone of the same sex is something that can and should be changed and fixed.

—A school counselor in Hanoi, September 2019

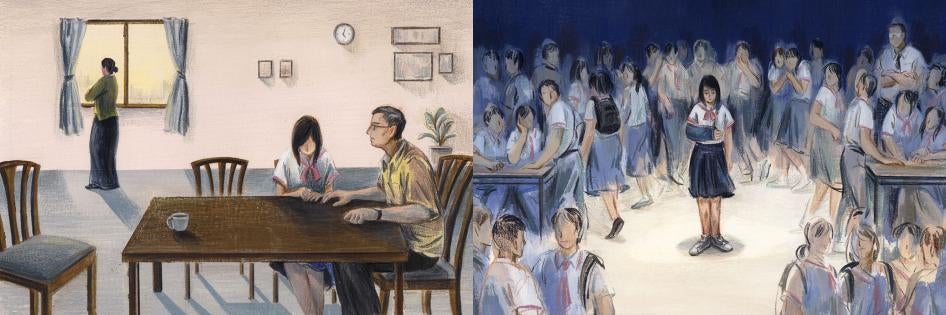

Just months before Human Rights Watch interviewed Lanh, an 18-year-old bisexual high school senior, school staff had confiscated her phone. “The teacher invited my parents to meet. She talked about my school work, and also mentioned that I liked girls too,” Lanh said. “She told my parents to take me to the doctor to get my gender checked.” Lanh was not in the room when her teacher said this to her parents, but, she told Human Rights Watch, “After that, my parents told me at home: ‘Your teacher told us you are an o moi.[50] Now you will have to go to the doctor.’”[51]

Other interviewees described the pervasiveness of the belief that same-sex attraction is a diagnosable mental health condition. This widespread belief had significant impact on the lives of young LGBT people Human Rights Watch interviewed, ranging from serving as the root of harassment and discrimination, to, as in the case of Lanh, parents bringing their queer children to mental health professionals in search of a cure. A school counselor who works for a network of private K-12 schools in Hanoi told Human Rights Watch: “Sometimes teachers come to me and say: ‘OK I have a gay student—what can I do? The parents aren’t happy—is there a way we can fix the kid?’”[52]

Anthropologist Natalie Newton explained in a 2015 article that, “Vietnamese popular press, sex education material, and…medical textbooks consider homosexuality a disease.” [53] According to Newton’s research:

Vietnamese newspaper advice columns have also featured the opinions of medical doctors and psychologists who have written about homosexuality as a disease of the body, a genetic disorder, hormonal imbalance, or mental illness.[54]

“Sometimes the news broadcasters talk about LGBT issues. My parents would watch and discuss about it very negatively,” said Tuyen. “They don’t really know what it is, but they are sure that this is a disease.”[55] Seventeen-year-old Nguyên said his father told him in the 7th grade that “only 2 percent of homosexuals are really mentally ill—the rest are just trying to be trendy.” His mother then warned him that if she ever found out he was gay, she would put him in a psychiatric hospital. “So I decided then that I could never tell anyone,” he said.[56]

Sinh explained how his mother was extremely upset when she found out when he was in high school that he was in a relationship with a boy. “She cried. She thought I had an illness, a disease,” he said. “She banned me from seeing boys and brought me to a psychologist [thinking] maybe I’d change. I told her I was bisexual and my mom asked why I wasn’t normal.”[57]

A staff member at an international organization that has run LGBT-inclusive teacher training sessions across Vietnam told Human Rights Watch: “We hear feedback from some teachers that they don’t know why they are being forced to learn about LGBT because it’s a sickness and should be dealt with by doctors.”[58]

The Search for Accurate and Affirming Information

With schools not providing any such information, Vietnamese youth seek affirming and accurate information about sexual orientation and gender identity elsewhere.

Some found affirmation and support from their peers. An, a 16-year-old bisexual girl, told Human Rights Watch about how her biology teacher regularly said homosexuality was “unnatural.” Her classmates reacted in disbelief, but only out of earshot of the teacher. “The whole class reacted [to the biology teacher’s explanation that LGBT was unnatural] but not directly to her, because it would be impolite to do so,” An said. “But when she left, everyone was like, she really doesn’t know anything about LGBT.”[59]

But while students like An at least believed they had the tacit support of their classmates, others who were bullied by fellow students because of their behavior or appearance said that experience led them to believe there was something fundamentally wrong with them.

Hung, 21, said he never heard anything about LGBT people from his teachers, but that he had been bullied since elementary school. “Classmates made gay jokes in an aggressive way—towards me specifically,” he said, explaining:

I was scared. I thought there was something wrong with me. I thought I had done something wrong even though I had no idea what it was. I didn’t ask anyone—I was so scared—about information on these issues or feelings. I had no idea what to do so I just put up with it.[60]

Some students recounted how they searched for information from informal sources—in particular, by searching and browsing the internet.

Against the tide of anti-LGBT statements, even single instances of affirmative information were a relief. “When I was 18, I searched for information online. I thought I was sick,” explained Thuong, 23. “I googled ‘why does a girl like another girl?’ I found a website that said boys can love boys and girls can love girls. It made me relieved.”[61]

Nguyet, a 19-year-old lesbian, said finding affirmative information on the internet when she was younger was extremely helpful. “I just found stories online about girls who like girls. It wasn’t positive, outright telling me that this was OK, but it helped because it showed me this wasn’t something only I could think of,” she said. But the stories, while affirmative, were not as informative as an inclusive curriculum would have been. “It didn’t contain much actual knowledge,” Nguyet said. “And so I had many misunderstandings about gender and sexuality for a long time.”[62]

Even youth who would eventually identify themselves as queer said they came of age amidst intense stereotypes and misinformation about themselves and others. For example, 16-year-old Chinh said he misunderstood his fellow queer students until he found better information and came out himself. “I had a lot of stereotypes in my head and I joined my classmates in ridiculing the gay guy,” he said.[63]

Verbal Harassment

[After I came out], some accepted it, some didn’t and thought LGBT is some disease, so they started to bully and isolate me. At first when I told my best friend, she was just surprised. But after she once told me “Why are you filthy gay kinds even alive?”

—Lieu, a 19-year-old bisexual woman, February 2019

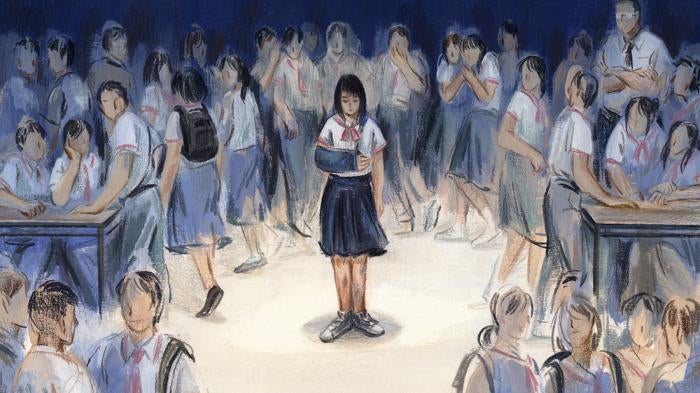

Verbal harassment colored the school lives of many of the LGBT students Human Rights Watch interviewed. In most cases, classmates singled out queer students whose expression violated gender norms—in particular, boys whose behavior was perceived as “too effeminate.”

For example, Phuc, a 20-year-old gay man, said his high school classmates bullied him. “My classmates would always joke around about bede,” he said. “They would call me those names directly. I was really introverted and had a feminine side. And my male friends would say I don’t play sports, I don’t act like a boy, so I’m a fag.”[64] Nguyên, 17, described how the bullying he experienced was specifically linked to his effeminate behavior. “I was bullied in grades 2-5 because my name was ‘weird.’ Then in grade six the bullying shifted because people thought I was effeminate and because I played with girls a lot.”[65]

Phuc described how bullies would point out his gender non-conforming behavior, tell him to change it, and then use anti-gay slurs. He said:

They never say that I’m gay but they think I’m too much like a girl—that my hobbies and behavior is too girly. They tell me I should be a girl, and call me ‘faggot’ and would say ‘hey, girl’ when I walked by.[66]

Chinh, a 16-year-old bisexual boy, said he had never experienced any harassment himself even though he has disclosed his sexual orientation to several classmates. However, he recounted: “One of my classmates is gay and he was recently called a slur meaning prostitute because his voice is a little bit feminine.”[67] Khanh, a 22-year-old trans man, told Human Rights Watch: “I did see a lot of people in other classes get picked on all the time. They are usually boys that are a bit like girls, so it’s very easy for people to ridicule them.”[68]

For others, the experience of verbal harassment was a routine part of their lives. “At that time I thought as long as there was no physical violence, it wasn’t worth reporting to the teacher,” said Quy, a 23-year-old bisexual man. “Looking back, it was actually really bad. I just didn’t know that at the time—because it was part of my daily life.”[69]

Physical Abuse

[The bullying] was mostly verbal but there was one time when I was beat up by five or six guys in eighth grade—just because they didn’t like how I looked.

— Đức, 22-year-old a gay man, September 2018

Lieu, a 19-year-old bisexual woman, told Human Rights Watch about her experience in high school in Ho Chi Minh City. In 10th grade, Lieu told her closest friend that she was bisexual, the term she identified with at the time. Her friend reacted poorly at first, then apologized. “Then she told the whole school about me,” Lieu said.

That disclosure of Lieu’s sexual orientation put her in significant danger. “In class, other people stopped hanging out with me,” she said. Her classroom was on the second floor, but when she walked in the courtyard below, classmates would throw water on her from above. “They hid my backpacks or sandals,” she said. “I played basketball, and there were times when guys deliberately threw the ball at my body or my head.” Others cut her books into pieces, and in one case her school uniform as well. Then, in 11th grade, classmates pushed Lieu from the second-floor terrace and she fell, breaking her arm and bruising badly. “When my parents saw the bruises and even when my arms broke, I said to them that was because of me playing basketball,” Lieu said.[70] Lieu’s father did not believe her, however, and visited the school under the guise of watching her play basketball, where he witnessed some bullying.

While physical violence appears to be rarer than verbal harassment, other interviewees reported to Human Rights Watch that they witnessed physical violence against classmates who were known or rumored to be queer. [71]

Unlike in Lieu’s case, where her parents were concerned about the violence she was experiencing at school, other interviewees reported their families were the perpetrators of violence themselves.

Seventeen-year-old Nguyên told Human Rights Watch he was eager to figure out what his sexual attractions to other men meant, so he frequently sought pornography on the internet. “I was really interested in it, but I didn’t know how to delete my browser. So my parents found it,” he said. “My father beat me until I was bruised. He hit me with a metal broom until it broke. I forgot about it until I saw myself in the mirror a few days later and noticed the bruises.”[72] Later, when he tried to tell his parents that he was gay, Nguyên’s mother shouted at him. “She threw things at me—a stereo speaker to my head, a spherical stone decoration too,” he said, adding that outbursts of shouting and violence occurred for several months. “I started having nightmares about my mother screaming at me—that she only had my father and my brother in her life.”[73]

Pressure to Conform to Social Norms

Our friends and teachers say aggressive things about LGBT characters on TV, that’s why I don’t feel safe [in school]. They say things like [the LGBT characters] are not human, they’re strange, they’re abnormal. They mean that being gay is disgusting.

—Phuc, 20-year-old gay man, February 2019

As discussed earlier in this report, Vietnam has made considerable strides in recognizing the rights of LGBT people in recent years. Nonetheless, for many LGBT people, dominant social norms continue to circumscribe free expression of their sexual orientation and gender identity and undergird acts of violence and discrimination. In an article on family politics and LGBT identities in Vietnam, anthropologists Paul Horton and Helle Rydstrom explain the apparent paradox:

Dominant socio-cultural norms regarding sexualities have allowed for the normative and legal exclusion of same-sex sexualities in contemporary Vietnam, while at the same time opening up spaces for resistance, through subversive practices, parades and demonstrations, political lobbying, and changes to the Marriage and Family Law.[74]

Horton and Rydstrom argue that there is intense pressure to conform to “heteronormative expectations about maintaining the family.” They also emphasize that pressures to conform to patrilineal family structures are complex and not borne solely by the queer individual. They document a case in which a 25-year-old lesbian named Bui explained how her mother had suspected she was a lesbian based on her fashion choices and, before she ever disclosed her sexual orientation, her mother threatened to commit suicide if she ever came out publicly as gay. They wrote, “she told Bui she could cope with Bui’s sexual preference but not with how other people would talk about her.”[75] The scholars explained:

[P]arents may react negatively to their son or daughter coming out, not only because of their own views on sexuality and the importance of marriage, but also because of wider sociocultural norms and the negative implications it could have for the collective face of the family.[76]

In other articles based on ethnographic fieldwork, Horton documents how widespread perceptions of gender non-conformity influence students’ experiences of bullying, in particular how gay men reflect on the ways in which they concealed their non-conforming behaviors during their youth so as to avoid scrutiny and harassment.[77]

Lan Anh Thi Do, a professor at Vietnam National University, documented in a 2017 paper a case in which parents described how they identified and scrutinized “gay” behaviors in boys. She quoted a mother who said: “For teenage boys who are too weak and gentle, we will blame him as ‘bede’ [gay/girly/less masculine boys]… teenage boys should be strong so that they will not be attacked/persuaded by gay men…”[78]

In a study of more than 2,600 sexual minority women and transgender men conducted by researchers at iSEE, ICS (a Vietnamese LGBT group), Johns Hopkins University, and Harvard University, the researchers concluded: “Overall, negative family treatment predicted poorer mental well-being and increased suicidality and smoking and drinking.” The paper recommended interventions both to improve family acceptance and help trans men and lesbian and bisexual women cope with family disapproval.[79]

Having a safe school environment is particularly important for LGBT youth who face rejection or harassment at home. Some students described to Human Rights Watch the strategies they used to stay safe at school. Those stories illustrate resilience and creativity, but they also demonstrate where schools need to take action. It is the school’s obligation to make the facility and its activities safe. Or, as iSEE put it in their 2016 report:

Since not [all] LGBT students are fortunate enough to be able to hold dialogues with faculties, educational authorities should be in charge and provide clear guidelines to ensure that a very basic requirement [is] that how students are clothed would not become a discrimination against LGBT people.[80]

Perspectives of LGBT Students

When Ngoc, now 22, was in high school, he had begun transitioning and his appearance did not conform to the social norms of the female sex he had been assigned at birth. One day in 11th grade, his biology teacher called him up to her desk:

She wrote ‘boy’ and ‘girl’ with chalk on her table and asked me to choose one. She also asked why I cut my hair short. I realized she might not have the knowledge about sexual orientation and gender identity, but she saw that there’s a problem rising from the fact that I am LGBT.[81]

Ngoc told Human Rights Watch he appreciated the teacher’s discreet approach, as opposed to calling him out in front of his classmates. “She realized this was a sensitive topic, and that she wanted to help me somehow,” he said. The intense social pressures he was already experiencing at school and at home due to his appearance, however, made him remain fearful. “At the moment she asked [me to pick boy or girl], I was worried about how to answer, because I was afraid that if I told the ‘wrong’ answer, she would tell my parents,” he said.[82]

A 17-year-old bisexual girl explained: “I think old, traditional gender roles need to change—like how a girl should always have a husband—and also double standards placed on men. But when I express my opinion, people tell me I am cocky.”[83]

Some interviewees explained how school officials explicitly enforced gender norms. For example, in Nguyên’s case, his secondary teacher observed that he only played with girls, then reported this behavior to his parents and instituted punishment at school as well. He said:

In secondary school, I only played with girls because I didn’t like how boys would only talk about girls and gaming. Girls were much more fun. My home room teacher noticed this and told my parents about it. My parents were upset, so the teacher assigned me to be the cleaner of the classroom for three months straight. I never got the small classroom jobs again, like wiping the chalk board. I always had to be the cleaner. Class ended at 5 p.m. and I had to stay there alone until 8 p.m. cleaning the classroom.[84]

Cuc, an 18-year-old lesbian college student, explained that while some of her high school teachers had been supportive when she came out, even those who were superficially positive exhorted her to not be queer. “One of my favorite teachers who also likes me because I’m good at her subject (chemistry), talked to me one time [about my sexual orientation],” she said. “She told me ‘hey, you’re cute but is it true that you’re like that, that you like girls?’ She said it like it was somehow ridiculous [that I liked girls]...She was trying to redirect me, saying ‘real [straight] women are better,’” Cuc explained, adding that the teacher emphasized that her parents were likely to be unhappy she was not straight.[85]

Many of the LGBT students we spoke with felt palpable pressures to conform to social norms. For some, this meant never revealing their sexual orientation or gender identity to peers. Discretion purchased a modicum of safety. Twenty-one-year-old Diep said, “If a group of friends were chatting and someone mentioned LGBT people, others would stop that person and say, ‘Don’t talk about that, it’s disgusting.’ That’s why people never came out.”[86]

Hang, a 22-year-old bisexual woman, described how she protected herself, recalling her time in secondary and high school: “If I just act normally there would be no trouble. If I presented myself too much, I would be warned by other people in my school, but since I mostly kept to myself, it didn’t happen.”[87] A school counselor explained: “I’ve had teachers tell me, ‘Well, discrimination happens for a reason—kids who are strange are going to get treated strangely.’”[88]

Impact of Bullying and Exclusion

I don’t feel safe at school, because the view and mindset of other people on LGBT. I didn’t get hurt physically, but I did suffer mentally. You have to be hurt when people tell you have a disease that frequently.

—Nhung, 17-year-old bisexual girl, January 2019

LGBT youth who face bullying and exclusion at school suffer a range of negative impacts. Interviewees told Human Rights Watch they felt stressed due to the bullying and harassment they experienced, and that the stress impacted their ability to study. Some students said the bullying they faced due to their sexual orientation or gender identity led them to skip or stay home from school. “This bullying affected me very much, especially my mental health,” said Trung, an 18-year-old trans man. “I didn’t want to go to school and was so afraid of stepping inside the school gate.”[89]

Studies around the world consistently show that LGBT youth are at an elevated risk of adverse mental health outcomes, including depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and suicidality.[90] For example, government data in the United States from 2016, which has only recently recorded the specific experiences of LGBT youth nationwide, found that 8 percent of students who identified as lesbian, gay, or bisexual nationally experienced higher rates of depression and suicidality than their heterosexual peers.[91] Data showed that an alarming 42.8 percent of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth respondents had seriously considered suicide in the previous year, and 29.4 percent had attempted suicide, compared with 14.8 percent of heterosexual youth who had seriously considered suicide in the previous year and 6.4 percent of heterosexual youth who had attempted suicide.[92] An academic study in the United States showed a disproportionate 40 percent of youth experiencing homelessness identify as LGBT, due in large part to families rejecting their sexual orientation or gender identity.[93]

These analyses from elsewhere correspond with research findings in Vietnam. For example, a 2015 report by Save The Children and the Institute of Social and Medical Studies on homeless LGBT youth in Vietnam found that “discrimination, neglect, and abuse from their families were the main determinants to leave home and wished to find a more accepting community to be part of.”[94]

Some students told Human Rights Watch they skipped school to avoid bullying. For example, Due said: “One time a guy in my class—who already didn’t like me—told me, ‘If you come to school you’ll get beat up,’ so the next day I didn’t go to school.”[95] Trung, 18, spoke generally about his fear: “I didn’t feel safe going to school, because of all the bullying and pushing.”[96]

For others, like 17-year-old Hien, persistent bullying at school triggered a pattern of missing out on education. He said:

In secondary school I would skip class because I felt unsafe if I went to class. I knew that If I went, I would have to hear the homophobic ridicule, and it was better to just stay home. My grades suffered. The school week was six days and I stayed home at least three, and even when I went, I would skip certain classes because it was just too much. My parents noticed I was skipping school. They know I’m gay and thought I just didn’t fit in so I stayed home because of that. They didn’t know about the bullying.[97]

For most of the students Human Rights Watch interviewed, a desire to meet their parents’ expectations that they attend school eclipsed their fear of attendance. Phuc, a 20-year-old gay man, explained: “People made fun of me a lot. I felt tired of it and didn’t want them to do it anymore. But I always went to school in the end because I didn’t want to disappoint my parents.”[98]

Lack of School Response to Cases of Abuse

Schools need to change– that is urgent. The reason my generation is against LGBT or confused by LGBT is because we were never taught anything different. It won’t just help LGBT people– it will help all of us to be a better society.

—Mother of a gay son in Ho Chi Minh City

Almost all of the LGBT youth Human Rights Watch interviewed who had experienced bullying at school said they did not feel comfortable reporting it to school staff. This was sometimes because of overt, prejudiced behavior by the staff; in other cases, students operated on the assumption that it was unsafe to turn to the adults around them for help.

This is particularly telling because, in addition to formal curricula, schools typically provide a variety of resources to students: support from teachers, counselors, and other school personnel is a valuable asset, and should be available to guide LGBT youth as well as their non-LGBT peers. According to UNESCO, “support from teachers can have a particularly positive impact on LGBT and intersex students, improving their self-esteem and contributing to less absenteeism, greater feelings of safety and belonging and better academic achievement.”[99]

“I had never thought about talking to the teachers about it,” said Tuyen, 20. “I knew how the students reacted, and I was afraid that it would be worse with the teachers. I felt like they would not help me.”[100] Đức told us his 8th grade classmates beat him up, leaving visible scratches, but he did not report it. He explained:

It happened at school but I don’t think the teachers knew. I didn’t tell them afterwards either because I was afraid that people would take it more seriously and pay more attention to me because of it. I also didn’t think reporting would change anything.[101]

Khanh, a 22-year-old trans man, described his experience being bullied in high school and how that had informed what he felt he could expect from adult staff in the school:

In high school, people suspected me because I walked like a boy. Other kids ridiculed me before the whole class and our teachers. My classmate called me ‘bede,’ ‘les.’ It happened right in the middle of the class, in front of everyone. The majority of the class was just silent and ignored it. When I got ridiculed like that, at first I felt angry and started talking back because they just kept on talking. After a while I just got sad and decided to stay silent. I didn’t pay any attention to the teachers because I thought they were just like the other people, if they knew they would just turn the other way and be silent.[102]

Or as Ngoc, a trans man who experienced bullying at school, explained:

I didn’t tell this to anyone because I couldn’t tell them the reason why I was being bullied. Honestly at my school, when two people fought, both of them got punished. So I didn’t tell anyone because I don’t want to get myself punished.[103]

Some students operated on the assumption that teachers knew the bullying was taking place but were unwilling to intervene. “Teachers probably knew it was happening but didn’t seem to do anything about,” said Giang, reflecting a common sentiment from many of the students Human Rights Watch interviewed. [104] Others had direct experience of school officials neglecting to respond. In the case of 19-year-old Lieu, whose classmates broke her arms among other violent physical attacks, even her father’s direct intervention with school staff was met with only lukewarm action. She explained:

My father told the teacher, but the teacher didn’t do anything about it. He wanted me to switch schools, but I didn’t agree because I just wanted to finish school and didn’t want any changes. When my dad told my head teacher, she went to the class and asked everybody not to do it again. She never asked who did that to me. A week after my dad told the teacher about me getting bullied, he talked to my teacher again, and realized that making such a fuss is not a good way to go. I said to him that notifying the teacher would not do anything to solve the bullying. So he just tried to provide mental support for me to keep going to finish school.[105]

Impact of a Supportive and Inclusive School Environment

I felt very safe in my high school. I also felt very lucky. While I was in school, I always thought that this was just a normal thing. But after I graduated and talking to other people, I realized my school was a very safe place.

—Tran, 22-year-old lesbian, January 2019

LGBT youth who reported receiving affirming, accurate information about sexual orientation and gender identity in school, or support from their peers or teachers, said the experience was edifying. It encouraged them to attend school more regularly and defend themselves in instances of misinformation or harassment.

Chau, a 16-year-old bisexual girl, told Human Rights Watch that her 9th grade sex education lessons featured discussions on LGBT topics. “The teacher said two guys or two girls can have children together, you can have children regardless of what kind of relationship you are in, so you don’t need to be too worried about who you love,” she said.[106] Men, a 17-year-old bisexual girl, told Human Rights Watch: “In secondary school, my biology teacher talked to us about the fact that nowadays, gay couple marry and have kids is very normal.”[107]

Others were able to explore LGBT issues in their independent work. Tran, for example, said LGBT issues were frequently mentioned in classes when relevant and he was able to write a paper for his literature class about a same-sex couple. “Our Youth Union also had a short film contest focusing on LGBT rights, and the students were very interested and sent in a lot of submissions,” he said.[108]

Being able to recognize their experiences and learn about sexual orientation and gender identity helped LGBT youth feel safe at school. As Ngoc explained:

I found that when I had more knowledge, I was able to protect myself better. I was able to demand my teachers call me the correct pronoun…and the teachers would usually listen. I think empowering LGBT people for them to be able to protect themselves and change others is very important. [109]

A school counselor in Hanoi emphasized to Human Rights Watch that the LGBT youth who make it into her office can thrive with the right support. “I can give them books and talk to them about the facts about gender and sexuality, which helps against all of the negative and false information and then they tend to do well,” she said. “But most kids, even the ones who survive the self-doubt and self-hatred that keeps them from seeking counseling—they still struggle to access information. Even if they have a queer person in their life—and that’s very circumstantial if they do—it doesn’t mean they’re getting all the right information.”[110]

II. Parent Organizing

“The only way not to lose them is to use love.”

—Father in Ho Chi Minh City

Hang became an activist because she was afraid of losing her son, Phong. Now in his 20s, when Phong was in high school his classmates bullied him about his “unmanly” behavior, causing him to become depressed. When Hang tried to talk to school officials about this issue, they responded by telling her that if her son stopped behaving improperly, the bullying would stop too.

Today, she is among a handful of volunteers with PFLAG-Vietnam, an organization whose name is an acronym meaning “Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays.”[111]

The first chapter of what is now PFLAG met in New York City in 1973 (the group was not named PFLAG until the 1980s) after an elementary school teacher’s gay son had been beaten and she wanted to advocate on his behalf. She organized other parents of queer children to support them and prevent violence against them. PFLAG affiliates—as well as organizations with a similar constituency and mission—have been incorporated in dozens of countries worldwide, including China, Myanmar, and Vietnam.[112]

In Vietnam, PFLAG remains an informal, unregistered effort, but volunteer parents have already begun to see results through their engagement with other parents of LGBT youth.

In Hang’s work as a volunteer over the past five years, she has encountered parents of LGBT children with a range of views and beliefs. “Even a parent with a Ph.D. in psychology asked whether his [gay] son was really a man or if he was husband or wife in his relationship,” she said. “They also often want to blame themselves—they think they might have done something wrong raising the kid.”

The paradigm can be daunting, Hang said: “They really ask us for methods to change the kid—whereas what we have to show them is how to change themselves.” PFLAG offers both private meetings with experienced volunteers and workshops where parents can meet in groups. Hang explained:

The workshops we run for parents have a sense of community among the participants—that they’re not going through this alone. It accelerates the process a lot compared to individual conversations.

PFLAG volunteers across Vietnam typically start by discussing basic terminology with new parents: terms such as sexual orientation and gender identity, for example. “This is seen as a very private matter,” Hang emphasized, adding that even the fact that an initial meeting is taking place should be seen as a sign of progress. “If parents agree to meet with me, they have in some way already started to accept their child.”

Tradition also features prominently in most discussions. “It’s a very basic notion in Vietnam that the main goal of the family is to reproduce,” said Hang. “The issue of having a child is not just for the immediate couple, it’s seen as a duty for the parents too. This creates enormous pressure for the family and they exert all of that pressure on the couple,” she said. A 2014 paper by the Institute of Development Studies noted:

Gay men who are also the eldest and/or only son thus face particular gendered duties and burdens. A failure to comply does not only affect them but also their entire family, who may be socially ostracized. Women are also under pressure from duties and responsibilities as mothers and caregivers.[113]

“When parents are new to this, they think their children will be unhappy without the traditional family model,” said Hang. PFLAG tries to engage this desire of parents to see their children be happy. “We try to convince them by highlighting how their love and support for their child can counteract all of the discrimination and horribleness that their kid will face in society,” Hang said.

PFLAG also tries to conduct presentations in schools, to demonstrate to teachers and youth that the adult generation accepts and understands LGBT people. However, they report, they are typically turned away.

“Most of the time we get rejected from the schools,” Hang said. “We hold teachers in very high moral standing in Vietnam. Teachers tell us they’re mostly concerned that parents will accuse teachers of teaching bad values and making the kids gay—so they don’t allow PFLAG in.”

And it is that specific nexus that needs to change urgently, Hang believes.

“Schools need to change—that is urgent,” she said. “The reason my generation is against LGBT or confused by LGBT is because we were never taught anything different.”

Thang, a PFLAG volunteer and father of a gay man, told Human Rights Watch he spent weeks crying quietly after his son came out to him in high school. “I knew I had to keep a strong face because he had an important exam and I wanted him to focus on that, but I was crying a lot,” he said.[114] He was deeply upset by his son’s homosexuality, and wanted to figure out a way to change him.

But for Thang, the choice was clear: “In that moment I had a choice. I never expected that my son could become a victim of my own hatred. And I knew if I continued thinking like that, I would lose my boy,” he said. “He’s a good person. The only way not to lose him was to use love.”

He first encountered parent-volunteers before PFLAG had formed its network, and the experience convinced him to become an activist himself.

“I’ll never forget meeting other parents for the first time,” he said. “It felt incredible not to feel alone any more. I can see the same in the other parents—that we all want companions on this journey.”

Thang’s journey was a paradigmatic shift—from being overtly homophobic to embracing his gay child to actively encouraging other parents to do the same.

“When my son first came out, I was afraid of the discrimination he would have to face. At that time, everything that was slightly different was called bede by everyone,” he said. “And I was the one using that word as a slur, too. I was very homophobic and I knew how vicious it could be.”

In Thang’s opinion, schools are becoming more open, but have a long way to go. He has done presentations for PFLAG in recent years in a handful of provinces where teachers have attended on their own volition, for example.

“Schools need to get better at this issue. We need more support for LGBT community groups so they can thrive,” he said.

III. Human Rights Legal Standards

In its 2014 Universal Periodic Review (UPR) at the UN Human Rights Council, the government of Vietnam accepted its one recommendation related to sexual orientation and gender identity: “Enact a law to fight against discrimination which guarantees the equality of all citizens, regardless of their sexual orientation and gender identity.”[115]

In its 2019 UPR, Vietnam rejected recommendations to include sexual orientation and gender identity in the Labor Code and to legalize same-sex marriage. However, the government accepted recommendations to:

- Develop legislation against discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation and gender identity.[116]

- Take further steps to ensure the protection of all vulnerable groups in society including lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex persons.[117]

- Enact legislation to ensure access to gender affirmation treatment and legal gender recognition.[118]

In September 2019, the Prime Minister’s office issued an order specifying how various government agencies should implement Vietnam’s UPR recommendations.[119] The order included:

- Instructions to the Ministry of Justice to undertake: “Promulgating and implementing national action plans and programs to eliminate stigma and discrimination against women (to increase women’s participation in all fields and eliminate violence gender) and vulnerable groups…[including] LGBTI people.”

- Assigning to the Ministry of Health the responsibility to “examine legal gender recognition procedures without medical requirements” and to “allocate sufficient human and financial resources to implement effective plans, national action programs to eliminate prejudice, discrimination toward vulnerable groups…[including] LGBTI people.”

- Assigning to the Ministry of Labor, Invalids, and Social Affairs the responsibility to “review and recommend improvements to legal standards to ensure equality between men and women, non-discrimination on the basis of gender (including LGBTI).”[120]

The Right to Education

The right to education is guaranteed under various Vietnamese laws. Directives on how to ensure that right is realized by, for example, reducing school violence, are detailed in decrees from the Ministry of Education and Training. Vietnam’s 2016 Children’s Law states:

- Article 16. Right to education, study and develop gifts:

- 1. Children have the right to education and learning to develop comprehensively and reach their full potential.

- 2. Children are equal in terms of learning and education.[121]

In its preliminary report to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child for its upcoming review, the government of Vietnam emphasized:

The 2016 Law on Children incorporates and broadens the principles of the [Convention on the Rights of the Child], including the principles of “non-discrimination against children” and the prohibition of “stigma and discrimination against children on the ground of personal characteristics, family circumstances, sex, ethnicity, nationality, belief and religion.”[122]

Vietnam’s Law on Education stipulates in article 10 that “Learning is the right and obligation of every citizen” and that “Every citizen, regardless of ethnic origins, religions, belief, gender, family background, social status or economic conditions, has equal rights of access to learning opportunities.”[123] In a 2017 decree, the Vietnamese government issued a decree on measures to prevent school violence. It included mandating that schools have “no gender stereotypes [or] discrimination” in classrooms and specified measures to support students who are at risk of violence, including:

- Prompt detection of both perpetrators of violence and those they may be targeting.

- Assessments of the risk of school violence so that preventative measures can be taken.

- Counseling with students who are at risk of violence to reduce that risk.[124]

In 2019, the Ministry of Education and Training issued a detailed directive regarding preventing school violence. However, it did not mention the specific vulnerabilities of various groups of students, including LGBT students.[125]

The right to education is protected in international law, notably in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, and the Convention on the Rights of the Child, ratified by Vietnam in 1982 and 1990, respectively.[126] The Convention on the Rights of the Child specifies that education should be directed toward, among other objectives, “[t]he development of the child’s personality, talents and mental and physical abilities to their fullest potential,” “[t]he development of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms,” and “[t]he preparation of the child for responsible life in a free society, in the spirit of understanding, peace, tolerance, equality of sexes, and friendship among all peoples, ethnic, national and religious groups and persons of indigenous origin.”[127] In its 2012 review of Vietnam, the Committee on the Rights of the Child urged “the State party to ensure that all children in the State party effectively enjoy equal rights under the Convention without discrimination on any ground.”[128] As discussed below, United Nations treaty bodies have stated that non-discrimination references to sex are understood to include sexual orientation.[129]

LGBT students are denied the right to education when bullying, exclusion, and discriminatory policies prevent them from participating in the classroom or attending school. LGBT students’ right to education is also curtailed when teachers and curricula do not include information that is relevant to their development or are outwardly discriminatory toward LGBT people.