Summary

Armed groups in central Mali killed hundreds of civilians in 2019, amounting to the deadliest year for civilians since Mali’s political and military crisis erupted in 2012. Central Mail, notably Mopti region, is the epicenter of the violence, where armed Islamists and ethnic self-defense groups massacred people in their villages, gunned them down as they fled, and pulled men from public transportation vehicles to be executed based on their ethnicity. Many people unable to escape armed attacks were burned alive in their homes while others were blown up by explosive devices.

Violence in central Mali has been escalating steadily since 2015, when armed Islamist groups largely allied to the militant Islamist group Al Qaeda began moving from northern into central Mali. Since then, they have continued to attack army, police and gendarme posts, commit atrocities against civilians, and enflame pre-existing communal tensions.

Islamist armed groups have concentrated their recruitment efforts on the pastoralist Peuhl by exploiting their grievances with the state and other ethnic groups. Recruitment from the Peuhl community inflamed tensions within the agrarian Bambara, Dogon, and Tellem communities, who – in the face of inadequate security from the Malian state – formed self-defense groups to protect their communities. The Peuhl also formed similar self-defense groups in response to these tensions.

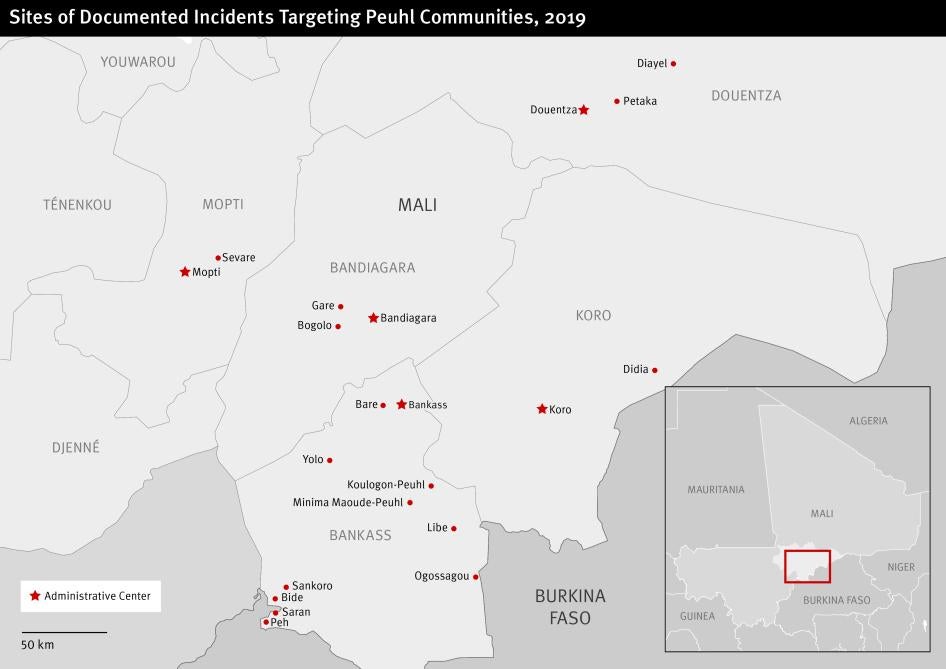

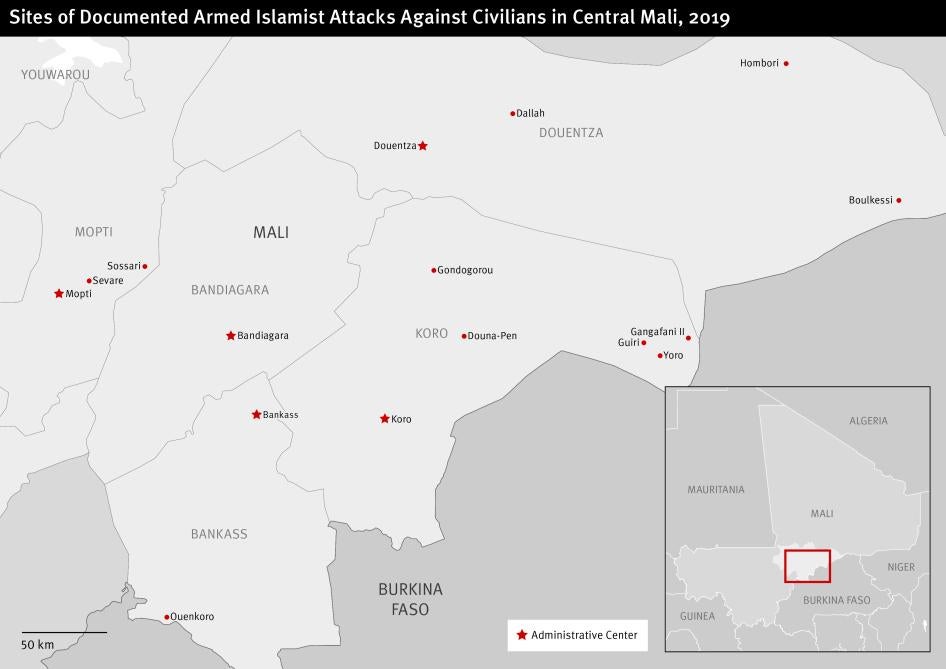

This report documents dozens of attacks allegedly by ethnic militias and armed Islamist groups in central Mali from January through November 2019, during which at least 456 civilians were killed, and hundreds wounded. The attacks documented took place in more than 50 hamlets, villages and towns in Mopti region, the majority in areas along Mali’s border with Burkina Faso. Civilians were largely the targets of the attacks, including several that appeared well-planned and organized.

Human Rights Watch believes the total number of civilians killed in communal and armed Islamist attacks in central Mali in 2019 is much higher than those documented in this report given the relentless “tit-for-tat” retaliation in often-isolated areas. During these attacks, in which there were often no witnesses, people were gunned down or hacked to death as they tended cattle, worked in their fields, or took goods to or from market.

Nearly all the attacks on villages by Dogon or Peuhl self-defense groups and armed Islamists were accompanied by the burning and destruction of houses and granaries, and looting of livestock, food stocks and valuables. The 2019 violence in central Mali forced tens of thousands of villagers to flee their homes and led to widespread hunger.

Human Rights Watch documented the abuses during four research trips to Mali’s capital, Bamako, and the central Malian towns of Sévaré and Mopti, and in phone interviews throughout 2019 and in January 2020. Human Rights Watch interviewed 147 victims and witnesses to abuses, as well as leaders from different ethnic communities, security and justice officials, diplomats, aid workers, and security analysts.

The findings build on Human Rights Watch research in Mali since 2012, including the 2018 report, “We Used to Be Brothers”: Self-Defense Group Abuses in Central Mali, which extensively examined the root causes of communal violence, the role of the state in protecting civilians, and the failure to ensure justice for the atrocities.

Dogon self-defense groups, notably Dan Na Ambassagou, whose attacks targeted the Peuhl community, were implicated in 2019’s first atrocity – the January 1 killing of 39 Peuhl civilians in Koulogon – as well as Mali’s worst atrocity in recent history – the March 23 killing of over 150 Peuhl civilians in Ogossagou. Dogon militia were also implicated in over 10 other attacks on villages, as well as three incidents in which several Peuhl men were removed from public transportation vehicles and killed.

Communal attacks allegedly perpetrated by Peuhl self-defense groups included the June 9 massacre of 35 Dogon civilians, over half of them children, in Sobane-Da; the July 31 killing of at least seven traders in and around Sangha village; the November killing of nine men near Madougou, and several other incidents.

We also documented the killing of 116 civilians by armed Islamist groups in central Mali, the majority of whom were of Dogon and Tellem ethnicity. They included the killing of at least 38 Dogon and Tellem civilians in Yoro and Gangafani II villages, and the execution of at least 14 civilians, mostly Dogon, who were taken off public transport vehicles around the towns of Sévaré and Bandiagara.

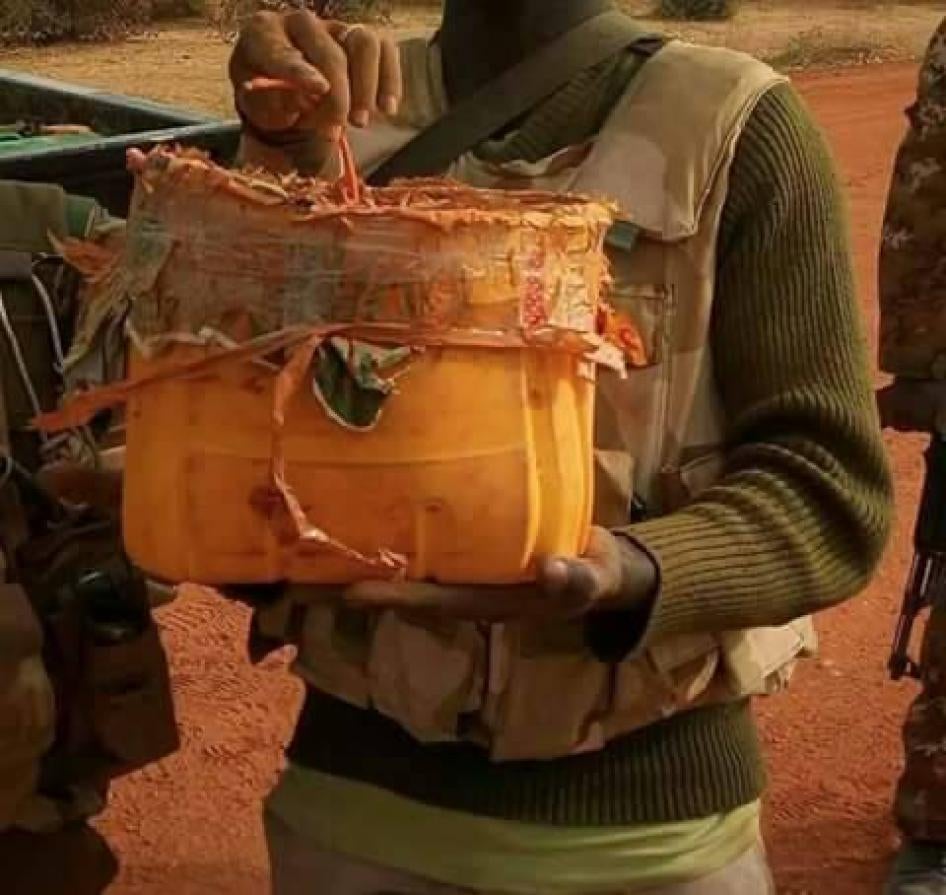

Over 50 civilians were killed by improvised explosive devices (IED) allegedly planted by armed Islamists as vehicles struck them or – in one case – when a civilian’s corpse had been booby-trapped. Several community leaders were abducted and are presumed to have been executed by the armed Islamist groups.

The worst atrocities spurred strong commitments from the Malian government to bring those responsible for abuses to justice. While the Ministry of Justice has made progress on investigations into a few massacres and Malian courts tried and convicted some 45 people for several smaller incidents of communal violence in 2019, magistrates had yet to question powerful militia leaders implicated in the worst atrocities.

Government officials blamed slow progress on accountability on the challenging security situation and inadequate resources, while community leaders said the government appeared to favor short-term reconciliation efforts over deterrence by way of prosecutions. Many of those interviewed expressed grave concern that the lack of accountability was emboldening armed groups to commit further abuses amid a general climate of impunity.

Human Rights Watch urged the Malian government to hasten the disarmament of abusive armed groups and the investigations and prosecutions of those from all sides responsible for the serious abuses documented in this and previous reports. Ethnic militias and armed Islamist groups should cease all attacks on villages, extrajudicial killings, kidnappings, and other serious abuses against civilians.

Mali’s international partners should press the government to ensure that those responsible for communal violence are appropriately held to account and to provide more support to the Malian judiciary in central Mali and the Bamako-based Specialized Unit for Terrorism and Organized Crime, whose mandate in 2019 was expanded to include war crimes, genocide, and crimes against humanity.

Methodology

This report documents abuses committed against civilians by various self-defense groups and armed Islamist groups between January and November 2019 in Mopti region, central Mali. During four research trips along with telephone interviews in 2019 and January 2020, Human Rights Watch conducted 147 interviews, 119 of which were with victims of abuses and witnesses. The other 28 interviews were with leaders from the ethnic Peuhl, Dogon, and Tellem communities; local government, security and justice officials; foreign diplomats; local and international aid workers; members of victims’ groups; and security analysts.

The research trips took place in March, April, July and August in Bamako, the capital, and in Mopti and Sévaré, in Mopti region. The victims and witnesses interviewed are residents of 53 hamlets, villages and towns in Mopti region, notably within the cercles, or administrative areas, of Bandiagara, Bankass, Douentza, Mopti, and Koro.

Interviewees were identified with the assistance of community leaders and civil society organizations, and were conducted in French, Dogon, and Fulfulde, which is spoken by members of the Peuhl ethnic group. Interviews in Fulfulde and Dogon were conducted with the assistance of interpreters.

Many of the interviewees who had been displaced by the insecurity were living within informal internally displaced persons camps in Bamako, Sévaré, and other locations in Mopti region. They travelled to Bamako, Mopti or Sévaré for the interviews.

Death tolls referred to in this report were derived from witness accounts narrated to Human Rights Watch. When multiple witnesses of the same attack provided differing death tolls, Human Rights Watch has used the account with the lowest death toll. Alleged deaths reported by sources for which there was no firsthand witness are not included in death tolls recorded in this report.

We have withheld the identity and other identifying details of interviewees, to protect them from possible retaliation. Human Rights Watch informed all interviewees of the nature and purpose of the research, and our intention to publish a report with the information gathered. We obtained oral consent for each interview and gave interviewees the opportunity to decline to answer questions. Human Rights Watch did not compensate interviewees; only travel expenses were reimbursed.

Background: The Conflict in Central Mali

In 2012, separatist ethnic Tuareg and Al-Qaeda-linked armed groups rapidly took over Mali’s northern regions.[1] The 2013 French-led military intervention[2] and June 2015 peace agreement[3] between the government and several armed groups sought to eliminate Islamist armed groups, disarm Tuareg and other fighters, and reestablish state control over the north. Implementation of the agreement has been slow.[4]

Meanwhile, since 2015 Islamist armed groups spread from the north into central Mali[5] and from 2016 into Burkina Faso. These groups, linked to both Al Qaeda and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS),[6] have increasingly attacked both military targets and civilians. They have executed community leaders and government officials for their alleged collaboration with the security forces, indiscriminately placed improvised explosive devices on roads, and harshly imposed their strict interpretation of Islam.

Central Mali is largely inhabited by the Peuhl, also known as Fulani; the Bambara, Mali’s largest ethnic group; the Bozo; and the Dogon and Tellem, found around Mali’s border with Burkina Faso.[7] Administratively, Mali is divided into regions, communes, and circles, or cercles.

Armed Islamist groups have largely concentrated their recruitment efforts on the pastoralist Peuhl by exploiting Peuhl community frustrations over banditry, abusive security forces, public sector corruption, competition for land and water, and, increasingly, abusive self-defense groups.[8]

The increasing presence of and abuses by the armed Islamists inflamed tensions between the Peuhl and the sedentary Bambara, Dogon, and Tellem communities, which have been disproportionately targeted by the armed Islamists, and led to the formation of ethnic self-defense groups organized to protect their villages. Leaders from all communities said the Malian security forces were often slow to respond and at times failed to protect them from attacks by opposing armed groups.[9]

Incidents of communal violence, underscored by the growing presence of the Islamists in central Mali, have been rising since 2015, including hundreds of individual “tit-for-tat” killings of farmers, and herders from all ethnic groups, as well as dozens of large-scale massacres, which have disproportionately impacted the Peuhl.[10]

The episodes have followed a similar pattern in which the killing of a Bambara or Dogon civilian credibly blamed on Islamist armed groups is followed by a wave of heavy-handed retaliatory attacks on entire Peuhl hamlets and villagers. In 2019, armed Peuhl groups and armed Islamists themselves engaged in several massacres targeting Dogon and Tellem civilians.

Other factors have exacerbated the rising toll of communal violence and contributed to the lethality of attacks. These include competition over grazing and farming land, effects of climate change, population growth, and the proliferation of assault rifles and other military weapons.[11]

The fighting in central Mali amounts to a non-international armed conflict under the laws of war. Applicable law includes Common Article 3 to the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and other treaty and customary laws of war, which apply to non-state armed groups as well as national armed forces. The laws of war require the humane treatment of all persons in custody, and they prohibit attacks on civilians and civilian property, summary executions, torture and other ill-treatment, sexual violence, and looting. The government has an obligation to impartially investigate and appropriately prosecute those implicated in war crimes.

In June 2019, the United Nations independent expert on the situation of human rights in Mali, Alioune Tine, said the continuing deadly communal attacks on civilians in Mali “could be characterized as crimes against humanity.”[12] Following the March attack on Ogossagou, the UN special adviser on the prevention of genocide, Adama Dieng, deplored the “growing ethnicization of the conflict in central Mali” and said attacks against civilians impacting all communities in the context of the fight against terrorism had reached an “unprecedented level.”[13]

The mandate of the more than 13,000-member UN peacekeeping force,[14] the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA), in Mali since 2013, was in 2019 strengthened by the inclusion of the deteriorating security situation in Mali’s center as a second strategic priority. The force was also tasked to increase efforts to protect civilians and support efforts to bring perpetrators to justice.[15]

The growing insecurity in the Sahel region prompted the 2017 creation of a regional multinational counterterrorism force comprised of troops from Mali, Mauritania, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Chad. The force, known as the G5 Sahel Joint Force (Force conjointe du G5 Sahel), coordinates their operations with the 4,500 French troops and 13,000 UN peacekeeping troops already in Mali.[16]

Communal Violence in Central Mali in 2019

Human Rights Watch documented dozens of incidents of communal violence in central Mali in 2019 in which a total of 340 civilians were killed, scores wounded, dozens of villages looted and destroyed, and, according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the displacement of over 50,000 villagers.[17] Among the dead were dozens of children.

The abuses documented occurred between January and November 2019, and took place in the administrative cercles of Bandiagara, Bankass, Douentza, Koro, and Mopti. With few exceptions, the victims of attacks documented by Human Rights Watch were ethnic Peuhl, who comprised the largest number of victims, 284 dead, followed by Dogon, of whom 56 were killed.

Human Rights Watch estimates the number of civilians killed in communal attacks in central Mali in 2019 to be much higher than the 340 killings documented in this report, given the steady stream of reprisals in which one or several Dogon or Peuhl civilians were gunned down or hacked to death as they tended cattle, worked in their fields, or took goods to or from market. Community leaders, aid agencies, and civil society groups from the Peuhl, Dogon and Tellem communities sent Human Rights Watch lists of a total over 100 such apparent retaliatory killings, all of which merit further investigation.[18]

“Each day we receive word of new incidents in central Mali,” said a Malian human rights investigator. “Two days ago, there were seven reports of killings, yesterday it was four. We start to investigate, verify the facts, and we’re notified of a new killing. It’s relentless.”[19]

The Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED), a nongovernmental organization that collects and analyzes data on conflicts, recorded 591 civilian deaths in some 150 attacks by armed groups between January and mid-October 2019, in Mopti region.[20] They noted that attacks “attributed to Dozo/Dogon militias resulted in 310 civilians killed, making the Dozos the deadliest group in terms of civilian casualties.” According to ACLED, armed Islamist groups were responsible for 141 of the civilian deaths, while Peuhl self-defense groups were responsible for 90. The remaining 51 dead were attributed to unidentified armed groups.[21]

The incidents documented by Human Rights Watch included large-scale massacres, smaller attacks and individual killings. Witnesses to the attacks said most civilians harmed were deliberately fired upon, macheted to death, or burned inside structures. Many others were shot in indiscriminate gunfire as militiamen fired randomly and recklessly into villages or died after being caught inside a structure that had been set on fire.

The attacks by all forces were almost always accompanied by widespread pillage, the destruction or burning of villages, and large-scale livestock theft. The widespread insecurity undermined the ability of herders, farmers and traders to work, resulting in hunger and tens of thousands of displaced.[22] The insecurity also led to the closure of at least 525 schools in Mopti region, affecting over 157,000 children.[23]

Abuses Against Peuhl Civilians and Communities

Human Rights Watch documented 16 attacks by alleged armed Dogon groups against Peuhl civilians or communities in which a total of 284 civilians were killed. The incidents described in this section occurred in Koulogon-Peuhl, Minima Maoude-Peuhl, Libe, Yolo, Bogolo, Ogossagou, Didia, Bare, Saran, Diayel, Bankass, Peh, and near Douentza.

The attacks on villages followed a similar pattern: dozens of Dogon-speaking men travelling on motorcycles and armed with a combination of traditional hunting rifles, machetes, automatic weapons, and at times machine guns and rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs), surrounded and then stormed into a village in the early morning hours (typically 5 a.m. to 6 a.m.). Homes were often set ablaze, and civilians were killed as they tried to flee or as the armed men burst into their homes. In some incidents, the attackers spared women and children, while in others, they appeared to be directly targeted. Witnesses from three attacks described seeing victims mutilated before or after being killed, with hands, heads and or internal body parts removed and, in some cases, taken away.

The witnesses described the attacks as well-organized, and in the case of the two most lethal attacks – Koulogon and Ogossagou – planned and premediated. Several witnesses described how different groups of attackers “came in waves” with each being apparently responsible for different tasks: advancing, bringing water, evacuating the wounded, rounding up and looting livestock, setting houses on fire, and going house-to-house in search of victims or loot.

In other attacks, armed assailants took Peuhl men off of public transportation vehicles and killed or abducted them. Some of the attacks took place in villages that had a small or recent presence of armed Islamists. The attacks were usually preceded by apparent organized efforts to undermine the economic livelihood of the Peuhl community, and all of the attacks on villages were accompanied by the burning and destruction of homes, buildings, and granaries, as well as comprehensive looting of livestock, food stocks, money and valuables, which forced thousands of villagers to flee.

Human Rights Watch was informed of the killings of over 25 Peuhl civilians in numerous incidents for which firsthand witnesses were unable to be located. Human Rights Watch also received photographs and video footage of four separate incidents in which a total of five Peuhl men were beheaded, surrounded by self-defense group members. Most of the victims were reportedly herders, killed while grazing their animals.

Alleged Perpetrators

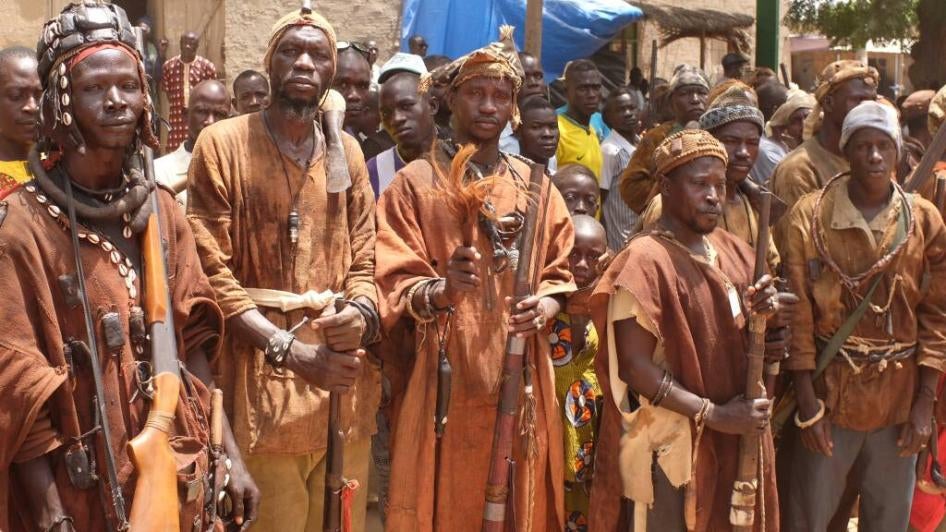

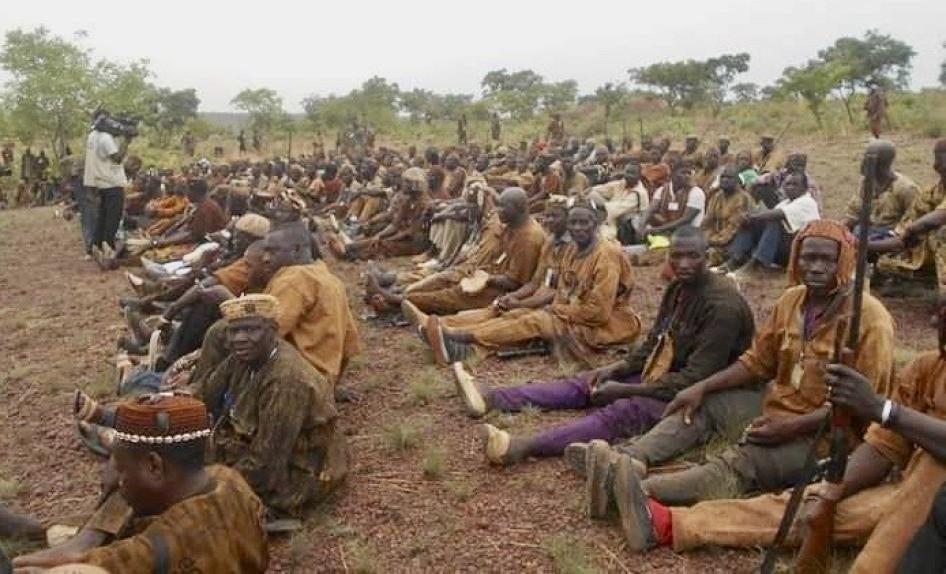

Peuhl victims and witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch identified the perpetrators as “Dozos,” “hunters,” “Dogon militiamen,” or members of “Dan Na Ambassagou.” Many witnesses recognized individual attackers who they said were Dogon men residing in the surrounding villages, including many whom they knew to be members of a Dogon village defense force.

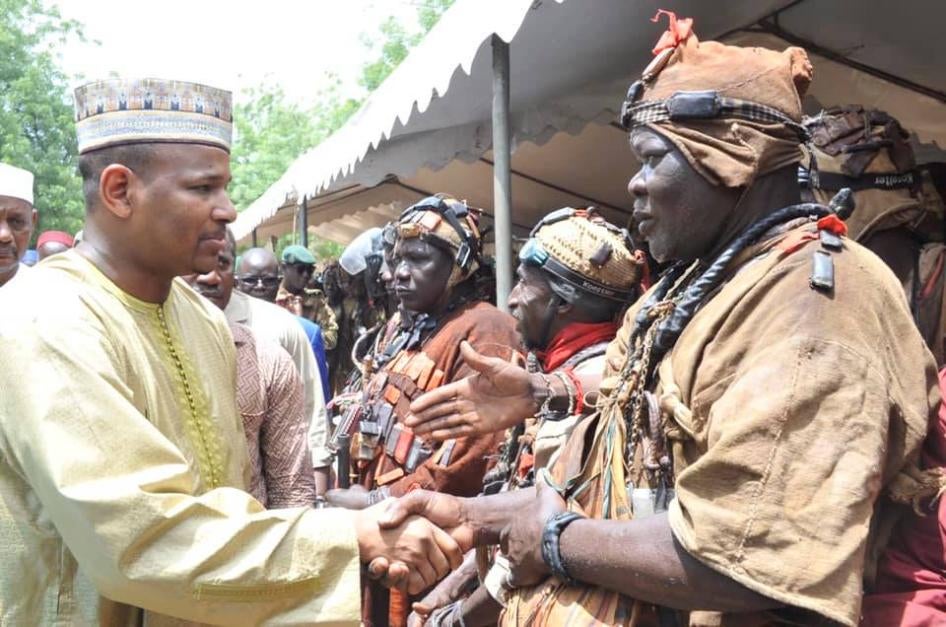

Witnesses typically described their attackers as dressed in attire used by the Dozo, or traditional hunters: reddish-brown clothing, adorned with amulets such as strings of bullet casings, shells or mirrors, and wearing caps often adorned with small animal horns. They said the Dozos were at times mixed with other armed men they believed to also be Dozos, but who were dressed in civilian attire or a combination of civilian and camouflage clothing.

Dan Na Ambassagou (“hunters who trust in God,” in Dogon[25]) is an umbrella group of Dogon village-based self-defense groups, or traditional hunting societies. It was launched in 2016, and is operational in Koro, Bandiagara, Bankass and, to a lesser extent, Mopti cercles.[26] Dan Na Ambassagou has hundreds of members, is organized into a quasi-military-like hierarchy, and is headed by Youssouf Toloba.[27] Toloba, from Mopti region, is a former member of the Ganda Koy and Ganda Izo militias founded to counter Tuareg rebellions in the early 1990s and 2000s.[28] Toloba said in December 2018 that Dan Na Ambassagou’s force had grown to more than 5,000 men operating out of at least 30 training camps and had incorporated a political arm with offices in Koro, Bandiagara, Bankass, Douentza, and Bamako.[29]

The attacks against Peuhl civilians documented by Human Rights Watch in 2019 are listed below in chronological order.

January 2019 Attack on Koulogon-Peuhl

Human Rights Watch spoke with seven witnesses to the January 1 attack by Dogon militiamen on Koulogon-Peul village, Bankass cercle, that killed 39 civilians. All but one of the witnesses recognized Dogon men from nearby villages among the attackers. An estimated 80 percent of the village was burned.[30]

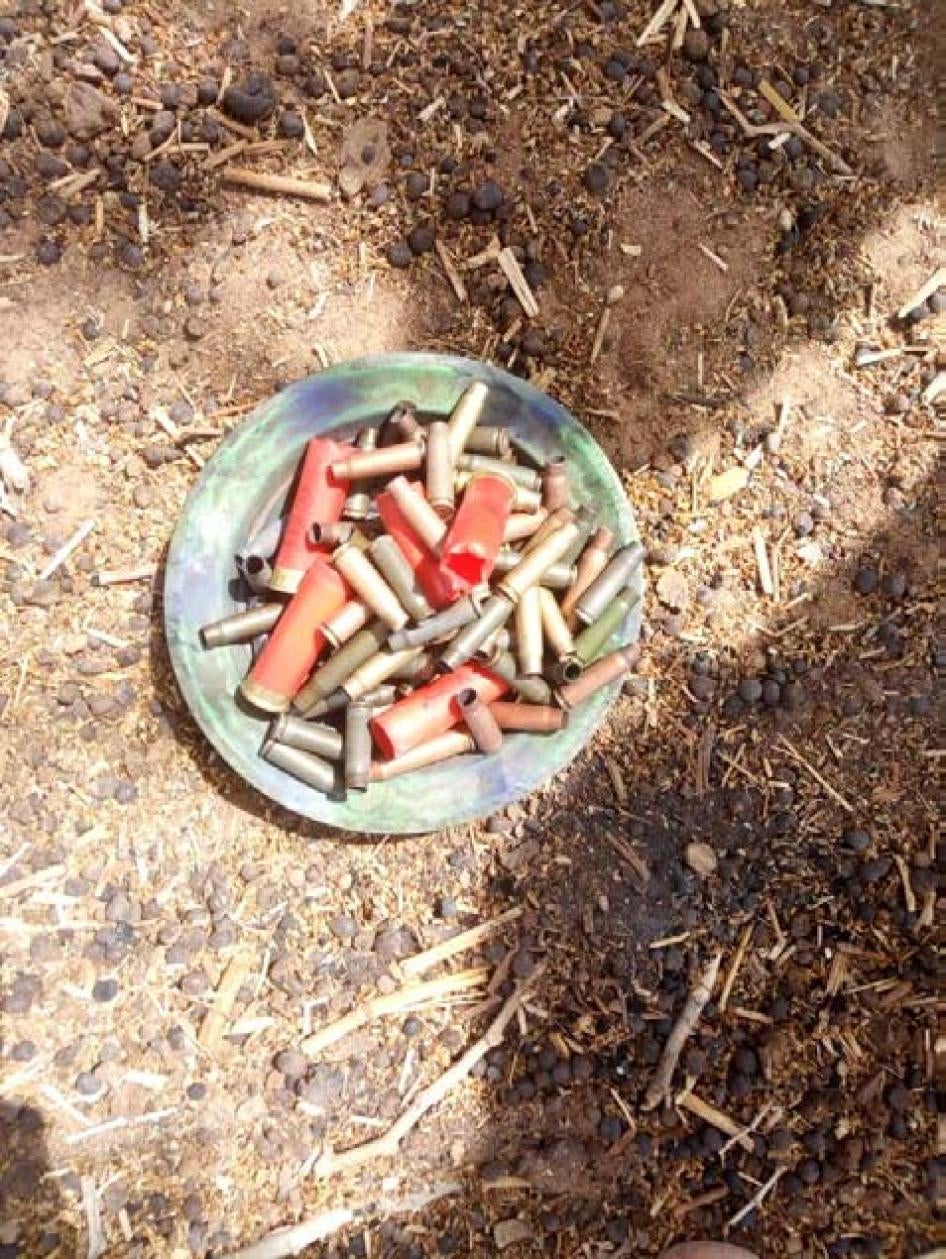

A 30-year-old herder said he saw the attackers “dressed as Dozos, in civilian attire, some in camouflage… armed with hunting rifles, AK-47s [assault rifles], PKMs [machineguns] and machetes. Later we found scores of cartridges littering the village.”[31] A 29-year-old woman said the attacked appeared premediated and organized:

On December 31 [2018], we saw motorcycles and a mini-bus going to the Dogon side of our village, but we thought it was for the New Year’s celebration. Around 5 a.m. we heard gunfire and knew it was something else: they had used the celebration as a cover to sneak in arms and fighters. The Dozos entered; the firing set our houses on fire. Several Dozos burst into our house, saying, “All the women, out! We don’t need you, but as for the men, they’re dead.” I fled with a child on my back, and one in each hand…But they shot my father, my uncle, and my parents in law.[32]

A herder said:

It started around the 5 a.m. prayer. At first, we thought the gunfire was for the holiday. We hid in a nearby house…From there I saw them infiltrating from different sides. I saw them kill four men – two in front of the mosque and two more, Moussa Diallo and Hama Diallo – as they dashed for safety. After falling – I’m not sure if they were still alive – the Dozos slashed them with machetes. I was terrified, thinking they’d find me. I was with someone who phoned the FAMA [Mali armed forces] for help saying, “Please, the Dogon are all around us!” But they only came after the attack was over. I recognized several of the attackers. All are Dogon: Dan Na Ambassagou had recently established a base a few kilometers away.[33]

A farmer, 20, who helped bury the dead said, “The bodies were inside houses, near the mosque, in the street, seven, burned, in one house; three were women and four children. They burned the village, the granaries; they stole eight motorcycles and 28 cows.”[34]

A herder, 30, said:

My father, grandfather, and one of my children were among those who perished, burned, in the chief’s house. From one moment to the next your father is dead, your child is dead, the friends you grew up with are dead… and then you have to bury them when only the day before you were together…You weep thinking they are no longer by your side.[35]

A report by the human rights section of MINUSMA characterized the attack as “planned, organized and coordinated,” noting that in addition to the 39 killed and 9 wounded, 173 houses and 59 granaries were burned.[36]

February 2019 attacks: Minima Maoude-Peuhl and Libe

On February 16, Dogon militia attacked Minima Maoude-Peuhl, Bankass cercle, killing six villagers including a 7-year-old girl and several elderly men. The child, her father, and another man were found charred inside their homes, while two elderly men appeared to have been killed some 200 meters away, while trying to escape.

One of four witnesses from Minima Maoude-Peuhl said, “I found two bodies about 200 meters from the village, along the path…Amadou, 85-years-old, was the eldest man of our village – it seemed he was shot in the head; and Allaye, around 67… They were too old to run.”[37] Another witness said:

They came around 5 a.m. – they were Dozos, in brown clothing and caps adorned with horns and mirrors; the cartridges were raining down…I saw different groups doing bad things – some setting fire to our houses and granaries, others killing and others taking the animals away. They left us nothing. Tension had been mounting. A month before, many Dogon men from the neighboring village had joined Dan Na Ambassagou… we used to see them with AK-47s.[38]

The following day, February 17, armed men speaking Dogon attacked Libe, also in Bankass cercle, some seven kilometers away. They killed 12 villagers, including seven found burned in their houses and five who were shot. Three witnesses described the attack and one provided a list of the 12 people killed, including three men in their seventies. “The attack erupted at 5 a.m. Not everyone could escape. Several people burned in their houses… we found only ashes… Respected Imam Abdoulaye Sidibe and his nephew perished, as did three women.” [39]

Another witness said:

I was asleep when the gunshots exploded…This was the attack we’d been fearing. I woke my family and we ran towards a forest, crouching to avoid the hail of bullets. From behind trees, I saw our village going up in smoke. Returning home later, we saw the destruction… they looted everything. My entire herd of 50 goats was gone. The attackers were from two neighboring Dogon villages. They arrived on three-wheeled motorcycles, and some others walked, all armed with [AK-47s] and shotguns.[40]

March 2019 attacks: Didia and Yolo

In early March, Dogon militia reportedly attacked Didia village in Koro cercle, killing seven people. A 23-year-old shepherd who hid during the attack said: “Dozens of motorcycles sped by around 6 a.m. There was gunfire, then our village went up in flames. I helped bury three children, two elders, burned in their houses, and two young men.”[41]

In mid-March, two shepherds were allegedly killed by armed Dogon as they grazed their animals near Yolo village, Bankass cercle. “We the Peuhl had already been attacked once, in January, but when things calmed down, we returned, mostly to crush our millet because we were hungry. But we were attacked again,” said a witness. “We heard gunfire, I saw them from the hill – I couldn’t see faces but recognized the Dozo hats with antlers. Two of our men were killed point-blank – we later saw their bodies – both already had wives and children.”[42] Another witness from the same area said he saw the attackers abduct a woman and her adult son around the same time. They had not learned their whereabouts and status.[43]

March 2019 attack: Ogossagou

The March 23 massacre marked the worst atrocity in Mali’s recent history. At about 5 a.m., over 100 armed Dogon-speaking men attacked the Peuhl neighborhood of Ogossagou village, in Bankass cercle. Human Rights Watch interviewed 26 survivors and witnesses of the attack. Village elders said at least 152 civilians, including over 40 children, were killed, over 60 were wounded, and that over 90 percent of the village was burned.

At least 12 armed Peuhl men awaiting entrance into a government-sponsored disarmament program, who tried to defend the village, were also killed.[44] The witnesses said that the attackers advanced on several fronts into the town, firing indiscriminately, executing and mutilating people in their homes and as they fled, and setting fire to houses including that of a respected religious leader who was sheltering several hundred villagers.

The preliminary report from MINUSMA’s human rights section described the attack as “planned, organized and coordinated,”[45] an observation witnesses told Human Rights Watch they shared. “They came in waves, attacking from different sides,” said one. “First heavy weapons fire from the west – we mobilized – then almost simultaneously, an explosion – a rocket launcher – from the east. We were only 40 men and couldn’t maintain both fronts,” said a Peuhl self-defense group member.[46] The attackers were also heavily armed: “They had AK-47s, PK machineguns, hunting rifles, grenades, containers of gasoline… people found RPG fragments,” a villager said.[47]

The witnesses said the majority of the attackers spoke in Dogon and were dressed in Dozo attire, while a small number wore civilian clothing or military camouflage uniform. “From where I was, I saw one large unit of Dozos and a second smaller unit of men in camouflage, sandy color, with bullet proof vests and military boots,” said a villager.[48]

A villager described witnessing the attack from his hiding place:

The attack started at about 5 a.m. with an explosion from the west, then bursts of gunfire from all sides. There was nothing but the sound of war. The Peuhl from the disarmament camp were overpowered and fled, which allowed the Dogon to flood in. I saw them advancing on foot, firing madly, and throwing fire and grenades into houses. I saw a family fleeing… the man was struggling to run with his elderly mother… Just as I was about to dash to help him move her to safety, the Dozo opened fire… I saw them fall – the man, his mother, younger brother, and his children. After taking over a few neighborhoods, hundreds of us ran towards the marabout’s compound, thinking we’d be safe.[49]

A 32-year-old mother described how her 5-year-old son was ripped from her arms and killed by advancing militiamen:

The gunfire got louder as they approached. I drew my children close… bullets came into the house… we crouched down. I wasn’t going to move, but they threw a burning object through the window that set the house alight. I grabbed my children and ran, but the armed men ripped them from my arms – they shot my little boy and only spared my second child, a year old, when they realized she wasn’t a boy. When the gunfire stopped, I remained close to my son's body, crying, until the army arrived.[50]

One man saw many houses set on fire: “They opened the windows from the outside, poured in gasoline and then fired their guns or lit a match,” he said.[51] A 50-year-old woman wounded in the attack said, “From my hiding place I saw them shoot six men, point-blank. My sons, Djibrill, 17, and Amdou, 12, also died.”[52]

A 55-year-old woman, whose husband, son, daughter-in-law and their small children were killed in the marabout’s compound, described why they’d sought shelter there:

Our houses were going up in flames, so we fled to the home of the grand marabout, Bara Sékou Issa. He was so well-respected; we never thought they’d harm such a man. We weren’t there long before the Dozo entered. They broke down the wall, then smashed the door, killing people by gunfire and by machete, then set [the house] on fire. I only survived after being protected by some Dogon women friends. I recognized 10 of the attackers, all from the Dogon part of Ogossagou.[53]

An elderly man who witnessed the assault on the marabout’s compound, recognizing around 10 of the attackers, said:

As the Dozos advanced, scores of panicked people were running into his compound, which was composed of four brick houses. From the window of my house I saw the attackers descending from a few directions. After surrounding the compound, they shot at the vehicles and solar panels, then broke through one of the doors, pouring gasoline; then they threw several grenades into the compound, followed by so many gunshots. Windows were popping, there was the sound of fire and explosions and screaming.[54]

The Malian prosecutor later reported that 333 bullets and 1627 cartridge cases were found at the scene.[55]

Victims of Ogossagou Attack

Among the dead were the village chief, Amadou Belko Barry, who was also mutilated and thrown in the village well with three other civilians; respected Muslim religious teacher or marabout Bara Sékou Issa; dozens of women and children; and many displaced villagers who had sought refuge after their own villages had been attacked by Dogon militia. “We’d fled to Ogossagou for safety, but the war found us again; 11 from my village died that day including an 80-year-old woman and a young mother with a child on her back,” said an internally displaced man who had fled his village in Koro cercle in 2018.[56]

A man who participated in the mass burials said, “Returning to the village after the guns quieted, bodies were everywhere. As people found their loved ones they cried, ‘Oh god, not my child!’ and ‘My grandfather, my mother!’ There were scores of bodies in the marabout’s house, most of them charred.”[57]

A close member of the marabout’s family said:

I lost 47 members of my family…my father, my first-born son, three brothers, two sisters, uncles, grandchildren, aunts…also killed were our faithful – the many talibés (Quranic students) studying there. In one room, I counted 60 people dead… most burned; in the next room were 14 dead, and two men who had hidden in the bathroom. They’d allowed some women to leave, but others were not spared. They burned the library, precious books, all in ashes. As they went in, I’d heard them saying in Dogon, “Kill them! We have to put an end to the Peuhl [il faut finir avec les Peuhl].”[58]

Six witnesses said deceased civilians had been mutilated – including village chief Amadou Belco Barry, around 70, and another man and a son of the marabout – though they were unsure whether the mutilation had happened before or after their deaths. “Near the mosque, I saw the 13-year-old son of the marabout with both hands cut off,” said one witness.”[59] “When participating in the burials, I noticed at least three people whose hands had been cut off,” said another.[60] Several witnesses described the mutilated bodies of the village chief and another man in front of the village mosque. One said:

I tried to help the chief flee, but he was weak…he couldn’t go on. I ran to save myself and left him hiding near the mosque…the armed men were advancing. But they found him. Later, I saw his body – he’d been shot in the chest and his two hands and other parts had been cut off. Another man, Adama Barry, had been decapitated, and at least one hand was cut off.[61]

Several witnesses said the village chief and Barry were later dumped in the village well, together with a boy of about 5 years and a 20-year-old woman, who survived the ordeal. A villager said:

I saw the Dozos break into my neighbor’s house…We heard shots and learned they’d killed several people there. They dragged a 20-year-old woman from inside the house, asking her in Dogon where the marabout was. She insisted she didn’t know, at which point a Dozo pulled out a knife, slashed her on the shoulder, then dragged her on the ground and threw her inside the village well.[62]

Several witnesses said village elders had called the security forces for help, but said they arrived hours later after the attackers had fled. “From 6 a.m., I personally called the FAMA and saw someone else calling the gendarmes in Bankass, only 14 kilometers away. They kept saying they were on their way,” a village elder said. “During the attack, the FAMA called me several times for updates. The last time, around 10 a.m., I said, ‘Don’t bother coming; the evil is already done,’” another elder said.[63]

Ogossagou Context and Attackers

Numerous witnesses from Ogossagou said that tensions between the Peuhl and Dogon neighborhoods of the village had risen in the weeks preceding the massacre as a result of several attacks – some of them lethal – allegedly perpetrated by Peuhl militiamen on nearby Dogon villages, as well as the recent establishment of government-supported disarmament camps of Peuhl men, including one in Ogossagou.[64]

Most of the witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch believed the perpetrators of the massacre were members of Dan Na Ambassagou, noting that the group was known to have several bases throughout Bankass cercle and were, as two witnesses said, “actively recruiting.”[65]

One witness emphasized that “Dan Na Ambassagou is the only organized Dogon group that operates in this area.”[66] Nearly all the witnesses recognized some the attackers, most of whom, they said, lived in Ogossagou’s Dogon neighborhood. A woman whose 7-year-old daughter was killed in the attack named the five armed Dogon men who entered her house, one of whom was the son of a Dogon village chief.[67] The witnesses provided Human Rights Watch with a total of 27 names of attackers they recognized during the attack as well as the names of villages where they were allegedly from.[68]

Three witnesses described a large concentration of Dan Na Ambassagou hunters in Bankass town two days before the Ogossagou attack, speculating that the attack might have been planned during this meeting. “It was a huge concentration of Dan Na Ambassagou,” said a 40-year-old trader. “They started coming in the morning, from all directions – on motorcycles and by foot, dressed in typical Dozo attire. At around 9 a.m., I saw [Dogon leader Youssouf] Toloba himself get down from his car and greet Dogon elders one by one as he walked into the gathering, which lasted until 4 p.m.”[69]

In an interview with a local journalist on March 24, the day after the massacre, Mamoudou Goudienkilé, a spokesperson for Dan Na Ambassagou, denied responsibility for the attack. He reportedly stated: “We have nothing to do with this massacre, which we condemn with the utmost rigor.” He added that in recent months, “many Dogons have been killed and nobody talks about it. Our villages are also attacked, burned and people killed.”[70]

An official with Dan Na Ambassagou told Human Rights Watch: “We conducted our investigation and neither Ogossagou or Koulogon were perpetrated by our forces. We didn’t order it, we didn’t perpetrate it, no way. There are lots of bandits all over, and they often dress up as hunters. Perhaps this was a settling of scores by some Dogon men, but our movement was not involved in either of these incidents.”[71]

On March 24, the government replaced two top military commanders and announced the dissolution of Dan Na Ambassagou.[72] However, its leader, Toloba, said he would not disarm until the government demonstrated their ability to secure Dogon villages and property.[73]

On April 8, Dan Na Ambassagou released a communiqué that withdrew a 2018 commitment to disarm and again denied responsibility for the Ogossagou attack.[74] The militia currently remains operational and has been implicated in further atrocities.

June and July 2019 attacks: Bare, Bogolo, Saran and Diayel

Six women from Bare village, Bankass cercle, described an early morning attack on or about June 13, that killed four villagers including three children ages 15 to 17. Another four men were missing. One witness said, “We were living in peace with our Dogon neighbors, even after Ogossagou, until that day. We all saw them – some had weapons of war, I saw their hats, with horns, and their Dozo attire, surrounding us on over 30 motorcycles.” Another witness said, “I didn’t see the bodies…it is the men who buried them… But I saw the mothers of the dead – Bocarie, Amadou, and Baba, 15, and Allaye, 16 – who now bear the pain. They burned the entire village; and stole our animals. The message was clear: we were to leave.”[75]

Human Rights Watch interviewed three victims who had been wounded in a June 20 attack allegedly by Dogon militia in Bogolo, a largely Peuhl village in Bandiagara cercle, which killed 12. “I recognized them. I know what villages they are from. They burned, pillaged all they could find, including 60 of my animals,” a village elder said.[76] Human Rights Watch observed scars on the neck, arm and buttocks of one victim, a 59-year-old shepherd, who had buried and provided a list of the dead. He said:

They entered in large numbers from the south, firing on everything that moved, using shotguns and AK-47s. I ran for my goats and came face to face with a Dozo who shot me with a hunting rifle. I tried to defend myself with a wooden bar so he didn’t steal my animals – but two more shot at me from afar, striking me on the neck and buttocks. The doctors extracted many pellets from my body. The assault lasted for hours and then we buried 12 people including four children. The villagers were desperate, crying out from their wounds or as they found the dead. Two young shepherds were missing but we finally found them…It seemed they were the first to be killed, as the Dozos crept towards the village.[77]

As the gunfire started, the Dozo emerged from the forest. My mom grabbed one of my 2-year old twins and I grabbed the other, a girl, and my 4-year old son. As we ran, my twin and I were hit with pellets (from the traditional gun)…I fell, and told my son, “Run! Run!” and he did, but he was confused so he stopped, and returned to me, crying. The attackers caught up with him and shot him at close range with a hunting rifle, killing him. Then they struck my wounded daughter with a machete, killing her. She would have survived the pellets – she wasn’t so badly wounded. Then they set upon me, slashing me with the machete several times. I knew them. They were from a nearby village.[79]

On June 30, at least 18 civilians were killed when Saran and two nearby hamlets, Sankoro and Bidi, all in Bankass cercle, were attacked. The mayor of nearby Ouenkoro, Harouna Sankare, was quoted in local and international media saying 23 civilians had been killed.[80] A respected elder from the area who had investigated the attacks described the contributing factors:

We, the Peuhls from Saran, used to live in harmony with our Dogon. We used the same land, shared the same well, prayed in the same mosque. But in recent months, Dan Na Ambassagou started recruiting in our area; they appointed local representatives in all the villages. At times we saw them firing their weapons in the air as a show of power. On the day of the attack, which killed 18 people, a group of Dogon had tried to steal cows from some Peuhl herders, who fought back, and this became the pretext for the attack. The Dogon called for reinforcements – we recognized Dogon from several villages – and about 30 Dogon surrounded the village, shooting everywhere and burning it. I was told there were Dogon from across the border in Burkina who participated. Eventually a FAMA helicopter and a truck of soldiers arrived, but they didn’t stop the attack, which was still in progress. Later, they made at least one arrest.[81]

A witness who had helped bury the dead said:

Saran was attacked around 1 p.m. from the east side by a large number of Dozos armed with shotguns and AK-47s, firing in bursts as they advanced. Five people – including an 80-year-old woman – were buried the same day. The next day we discovered the bodies of seven Burkinabè shepherds who had been taking their animals for the seasonal movement – a few [were found near] where the Dozos had launched their attack. During the attack, the Dozos broke into our houses to steal women’s jewelry, money and anything of value. Saran is only 14 kilometers from a FAMA base, but they didn’t save us.[82]

On July 2, the Diayel village chief, Amirou Diallo, his son, his grandson and a brother were among six killed during a 6 a.m. attack on the village in Douentza cercle. A villager who helped bury them said: “They started the attack with the chief’s house…I recognized some of them. They were the Dozo including those from our area…They approached the village by creeping along the adjacent hill before opening fire on the chief’s house. They stole all their animals – about 100 cows, donkeys and goats.”[83]

November 2019 Attack: Peh

On November 13, armed Dogon men attacked Peh village, Bankass cercle, situated three kilometers from the Burkina Faso border, killing at least 16 villagers. Three witnesses, including one who was wounded, told Human Rights they had each recognized several attackers who, they said, came from surrounding Dogon villages in Mali and Burkina Faso. They all credited the Malian army with helping to repel the attack. A Mali government communique denounced the attack, which it blamed on men dressed in “traditional hunter attire.”[84]

A villager who participated in the burial of 16 people and provided a list of the dead said, “We found the bodies of our people near the mosque, in their fields, in their homes and in the bush. Eleven were elderly who couldn’t run. Boucary Moussa, 84, was killed and thrown into a village well; Fatoumata Diagayeté, 80, was burned in her home; our marabout, Dramane Sidibé, 49, was killed near the mosque.”[85]

A 67-year-old farmer said:

The first group came from the direction of Burkina – some in Dozo attire and a few in athletic gear…I thought for a moment they’d come to play football. As the firing started I ran to my cows, tended by my children, fearing the cows would be stolen. As we fled, they fired directly at us, and from where we hid, I saw more attackers approaching from the Malian side.[86]

A man wounded in the attack said:

I saw at least 40 Dozo flooding in from several directions…they quickly overwhelmed the few village defenders and started killing and looting. They killed many as they fled with their animals – later we found their bodies in the bush – and others like my mother, burned in her house. The FAMA came at 6 p.m., and dispersed the attackers, who I think were Dan Na Ambassagou. They’re all over and are the engine behind this trouble: they’ve been harassing us for months… They stole everything, including our animals – the only thing I’m left with is the boubou [tradition Muslim robe] I was wearing.[87]

Executions, Abductions of Men from Public Transport Vehicles

Human Rights Watch documented three incidents in which a total of 10 Peuhl men were removed from public transportation buses by Dogon militiamen manning informal checkpoints and reportedly executed or disappeared. Security analysts said the checkpoints had been set up in apparent response to recent killings of Dogon either by armed Islamists or in communal attacks.[88]

Two people described the abduction and disappearance of three men taken off a public transportation vehicle in mid-March between Bankass and Sévaré. They said they had credible information suggesting the men had been killed the same day. A friend of one of the men said:

Boucar Bah, 62, Harouna Barry, 51, and a third Peuhl man were taken off a 207 Peugeot taxi from Bankass to Sévaré. I know this because a man who’d travelled with them came to my house an hour later, to tell me what happened. He explained how 20 kilometers from Bankass, near Gare village, they were made to stop at a checkpoint manned by Dogon militia. After ordering everyone out, the Dogon kept the three Peuhl men. He explained that the driver was so terrified that he returned to Bankass. Since that day, they’ve not returned home. We asked the FAMA to search for the men, but when they got there, the checkpoint was gone. We heard, through Dogon friends, that the three Peuhl men had been taken to a nearby village and executed.[89]

In early October, Dogon militiamen set up an informal checkpoint along the major highway heading north to Gao, near the villages of Petaka and Drimbe. Witnesses said it was set up in response to an alleged killing some days prior of a Dogon militiaman by a Peuhl herder. Witnesses said that on October 2 and 3, the militiamen forced at least seven Peuhl men out of buses at gunpoint and either executed or disappeared them.

“I was on my way back from Hombori on October 2 when Dozo swarmed it and forced three Peuhl men out,” a witness said. “A few days later, I saw their bodies along the road not far from where they were taken. People were too terrified to bury the bodies, which were there even today, almost 10 days after they were killed.”[90]

A market woman described the abduction of four Peuhl men from a bus on October 3:

On our way back from market, around 5 o’clock, a large group of Dozos, armed with hunting rifles and [AK-47s], threatened to spray the bus with bullets if the driver didn’t halt. They opened the back door and ordered only the Peuhl out. We were five, me and four men. They yanked the boubou of the Peuhl seated next to me, forcing him out, then pulled out a man on my other side. I cried, terrified I was next, but they left me. They ordered the driver to start his bus and leave, but he resisted saying, “Where did you take my passengers?” They told him, “If you want to die too, keep asking questions.” Since that day, there is no word from these men… We fear the worst.[91]

Abuses Against Dogon Civilians and Communities

Human Rights Watch documented eight attacks by armed Peuhl men or Peuhl civil defense groups in which a total 56 Dogon or Tellem civilians were killed. The attacks included a massacre, attacks on traders in or returning from local markets, and attacks on farmers in or returning from their fields. Some of the attacks appeared to be retaliation for killings of Peuhl civilians by Dogon groups. Dogon community leaders provided Human Rights Watch with details of over 50 other killings they attributed to armed Peuhl men.

Over a dozen Dogon civilians from different villages described how armed Peuhl men had provoked widespread suffering by blockading people in their villages, giving “ultimatums” to leave their villages under threat of what the witnesses perceived to be death, or by attacking and burning their villages and fields. They said these actions had resulted in profound economic hardship, hunger, and displacement.

Alleged Perpetrators

The victims and witnesses varyingly described the attackers as “armed Peuhl,” or “Peuhl self-defense groups.” Many Peuhl villages throughout central Mali have organized self-defense groups in response to lethal attacks by Dogon militia. Some Peuhl leaders said they were compelled to organize into self-defense groups to protect themselves from what they describe as the collective punishment of their community by Dogon militia for attacks carried out by armed Islamists.

These groups consistently deny being affiliated with any Islamist armed group, contending that their members are comprised entirely of local Peuhl residents.[92] Dogon villagers contest this assertion, saying they have on numerous occasions identified Peuhl men from local village defense forces working alongside Islamist armed groups.[93]

Dogon witnesses from a few of the attacks said they believed individual armed Islamists had reinforced some village Peuhl self-defense groups, an assertion Human Rights Watch was unable to verify. However, three Peuhl elders said that some armed Islamists they knew said they had “asked for permission” to leave their unit or abandoned the armed Islamists so as to return to protect their native villages.[94]

The link between Peuhl self-defense groups and armed Islamists has been fed by several statements made by the Jama'at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (Group for Support of Islam and Muslims, or JNIM), Al-Qaeda’s wing in West Africa and the Sahel. Following its March 17 attack on Dioura military base in central Mali, which killed 23 Malian soldiers, a JNIM statement said the attack was “in response to heinous crimes committed by the forces of the Bamako government, and the militias supported by it, on the right of our people of the Fula.”[95]

Another JNIM statement released shortly after the Ogossagou massacre promised that "the Fulani and the oppressed will be avenged throughout the region."[96] An audio recording from JNIM leader Kouffa that circulated in late September, and that appeared to position JNIM as defenders of the Peuhl community, served to “further fuel ethnic misunderstanding and violence,” according to a Peuhl community leader.[97]

Several attacks attributed by different sources to “armed Peuhl” and “Peuhl self-defense groups” are described below in chronological order. Many other atrocities against Dogon civilians credibly implicating armed Islamist groups are discussed in a subsequent section of this report.

December 2018, and March and May 2019 Attacks: Derou-Na, Kérékéré and Ama-Koro

On December 27, 2018, nine men, including two Imams, were killed near Derou-Na village, Koro cercle, on their way back from nearby Ogossanhi village where they had attended a ceremony honoring a deceased community member. “They weren’t fighters, they weren’t armed. They’d gone to express condolences to the family of a man who’d recently passed away when they were ambushed near a forest around 14 hr.” said a local man.[98] “I went with the army to recuperate the bodies…We found them two meters off the road; seven in one place, slumped over in their motorized tricycles and the others a few meters away, their bodies riddled with bullets,” said a witness.[99]

A witness from Kérékéré village, Bankass cercle, described a March 2019 attack by armed Peuhl men that killed three elderly residents:

First, they gunned down a few farmers in their fields and then in mid-March, dozens of them on motorcycles, firing in the air with AK-47s, returned. They burned a few houses, then, when we refused to leave, returned the next morning, burning the village east to west. Three elderly were killed…They couldn’t flee fast enough. Three days later, a few of us returned to rescue sacks of grain and other belongings, but they fired at us, killing another man.[100]

In mid-May, a young Dogon man was wounded when armed men – whom he believed came from a neighboring Peuhl village – fired on him as he was working his fields near the village of Ama in Koro cercle. “We were preparing our fields for planting when the Peuhl opened fire from several meters,” he said. “They didn’t steal anything… We weren’t doing anything to them. I don’t know when I’ll walk again. We thought 2019 would be better, but it’s not.”[101]

June 2019 attack: Sobane-Da

On June 9, armed Peuhl men attacked the Dogon village of Sobane-Da, Bandiagara cercle, killing 35 civilians, including over 20 children. Human Rights Watch interviewed three witnesses to the attack, two of whom said they identified several of the attackers who hailed from neighboring villages.

Sobane-Da is a Christian village; however, neither the church nor houses with crosses affixed to them were destroyed, suggesting religion was not the basis for the attack. “Our village of 431 residents is 100 percent Dogon and 100 percent Christian, but the church was not burned,” a community leader said.[102] “They came at 5 p.m., on many motorcycles that quickly surrounded us, and without talking, set fire to houses and started to kill. The majority of those killed were children. They rounded up and stole all our livestock… Everyone has now fled.”[103]

A 32-year-old man who witnessed the atrocities from his hiding place said:

I was having tea when the motorcycles came…I saw 12 attackers – riding two-by-two on six motorcycles, dressed in boubous cut short, with turbans and automatic rifles – but there were many more. We ran to hide in a house. An hour later, they set alight the Toguna [Dogon cultural meeting house], which forced Moise Dara [age 18] and Timothe Dara [age 22] to run out, but they were cut down by gunfire.

Then the assailants went to another house, in which were hiding many women and children. I heard them asking for the men to come out…The brother of the village chief came out, saying ‘Yes, I am here.’ They killed him 200 meters away. It was like he sacrificed himself to save the women and children. The attack lasted for hours… I heard people screaming, I smelled fire, and heard gunshots and “Allahu Akbar” several times.

When we heard the motorcycles leaving, I rushed to my house. My family said they had fired into the house, which set it on fire. We lost three of my family including two children, ages 10 and 12. They stole 900 animals from us and pillaged the entire village.[104]

The 35 adults and children killed were buried the next day in five common graves. A village elder, who had participated in the recovery of bodies and burials, said:

In one house was a family of nine…The family doyen was seated in front, a bullet in his head. The attackers had fired through the window, which set a sack of grain and then the whole house on fire, burning the other family members. Their charred bodies were entwined together, clutching each other, like it was their last moment together. Two grandmothers, five children, women with their babies still on their backs. It seemed like most of the dead had been burned. We found several yellow plastic containers they’d used for gasoline.

In one house was a woman, eight-months pregnant. Her husband was next to her as were other family members, and from her wounds, the baby could be seen. None of us could bear to go in there… or touch them. We had to leave that family to the fire department.[105]

The witnesses, Dogon community leaders, and security sources were divided on the level of involvement by armed Islamists in this attack. Two of the witnesses characterized the attackers as “terrorists,” and a Malian security source from the area said, “There is not a self-defense militia sufficiently structured to be able to organize such a major attack… No, at least some Islamists who are numerous in this area were implicated.”[106] In contrast, a Peuhl community elder noted, “This wasn’t the jihadists: it was perpetrated by a coalition of local Peuhl self-defense groups hailing from several neighboring villages.”[107]

An investigation by the human rights section of MINUSMA concluded that the attack was carried out by “30-40 armed men, described as young Peuhl men from surrounding villages.”[108] Investigators were unable to determine if the attackers were affiliated to a particular group.[109]

July 2019 attack: Sangha

On July 31, at least eight Dogon civilians including two women were killed, and several more abducted, when two groups of armed Peuhl men attacked traders gathered for and returning from the Sangha market, in Bandiagara cercle. Human Rights Watch spoke with three witnesses to the attack who also said hundreds of livestock were stolen by the attackers, whom they identified as both armed Peuhl “assailants” and “jihadists.”[110] One witness said:

We were in the market – many had come for a food aid distribution – when dozens of assailants raced in on brand new motorcycles. One group headed for where several shepherds were standing with their animals, surrounding and ordering that they follow them. An 18-year-old named Nouhoum Kodio resisted, and the jihadists shot him on the spot. While this was going on, another group went towards the road, where I heard they started firing on people randomly as they returned to their villages.[111]

A second witness, whose brother was killed, described the scene on the road:

My brother left Sangha market on his motorcycle in a small convoy. Given the insecurity this is how we travel these days. On their way back – some kilometers away – they were ambushed by armed assailants. As soon as I heard, I rushed to the scene, but he was dead…I retrieved his body… he’d been shot in his chest and face. I saw six other bodies over the road in the same general area… slumped over or near their motorcycles – some were drivers, other passengers. They weren’t armed… They were all traders from hamlets around Sangha.[112]

November 2019 attack: Near Madougou

On November 4, nine Dogon traders were killed during an ambush on a convoy of traders returning from the Madougou market, in Koro cercle. Two witnesses alleged that armed Peuhl men were responsible for the attack. The dead were from the Dogon villages of Indem, Kobadji, Tingué and Tomdin. A witness, whose 18-year-old son was killed, said:

The ambush occurred around 4 p.m. as our convoy of eight motorcycles and five donkey carts passed through a forested area near Tingué, about 10 kilometers from Madougou. I was on my motorcycle and my 18-year-old son was driving our cart with the macaroni, rice, and other items we’d purchased at market. Four men in our convoy had hunting rifles, but they didn’t have time to fire a single shot. I saw dozens of attackers on motorcycles in boubous and armed with military weapons. Some had helmets, others wore turbans. As the firing started, I saw several motorcycles falling down as the traders were hit by gunfire. Somehow, I maneuvered my way through the hail of bullets…but my son didn’t make it. My heart grieves but there’s nothing I can do…I can only pray for his soul. During the attack they also stole or burned several motorcycles and donkey carts including my own. [113]

Blockades, Ultimatums and Burning of Dogon Villages

A representative of a Dogon cultural organization said, “In all four cercles, armed Peuhl men – many think they’re Jihadists – have burned granaries, killed farmers, and stopped villagers from planting and harvesting. There is widespread hunger, malnutrition, and children with distended stomachs. Many villagers only eat once a day, while tens of thousands have fled.”[114]

One community leader, from Koro cercle, said:

Armed Peuhl men are surrounding Dogon villages, forbidding us to go to markets, forbidding us to get food aid, stealing our cattle and killing whomever they meet in the bush. It's as if our villagers are being strangled, condemned to die from hunger. This is the second year many villagers have been unable to cultivate.[115]

An elder from Koro cercle said, “From April 2019, the ultimatums started – in Ganga, Peno, Bisiwe, Keun, Tiniri and Segue hamlets. We were just starting to prepare our fields for planting, when the armed Peuhl men came saying, ‘Leave in 72 hours or else.’”[116] A farmer who fled his village in Bankass cercle said, “over 30 motorcycles with armed Peuhl men surrounded us, staying long enough to say we had two days to leave the village or ‘you will see.’ We took what we could carry and fled on foot and by pirogue [canoe].”[117]

A 52-year-old farmer from Bankass cercle who fled his village in March 2019 after receiving an ultimatum, said:

My 24-year-old son was killed in December 2018 on his way back from buying a cow… A friend who survived said they’d been shot by armed Peuhl men as they passed through a forest. But even with that pain, we remained in the village until March 2019 when a large group [of armed Peuhl men] rode in from the east and surrounded us while we were drinking tea. They asked for the village chief. The Peuhl leader said, “We’ve come to tell you, your family members, and the entire village to leave…you have until tomorrow” – they were aggressive, and heavily armed with strings of bullets. Everyone from the village, and several neighboring villages, fled that day.[118]

An elder from Baye commune, in Bankass cercle, showed Human Rights Watch a list of 17 hamlets whose harvest had been burned in late 2018 and who were too fearful to plant in 2019. “They’re sowing hunger and misery to drive out the Dogon population,” he said. [119] A Dogon farmer who’d fled his village after a few of his friends had been shot and killed in their fields said, “I’d worked very hard on my land, but what is more important, your life or your harvest?”[120]

Alleged Retaliatory Killings

Nine Dogon sources interviewed separately by Human Rights Watch, including local chiefs, civil society leaders and religious authorities, provided lists of incidents and victims of a total of 52 killings during 2019 that they attributed to Peuhl self-defense groups. All of the alleged incidents occurred in Bandiagara, Bankass, Douentza and Koro cercles.[121]

The Dogon leaders said the killings happened in isolated areas and that the men were all found dead after leaving the village to attend a local market, work their fields or graze their animals. The sources said they were unaware of first-hand witnesses to the killings. They believed the men had been killed by armed Peuhl groups largely because the killings had happened within the context of worsening communal relations and a cycle of retaliation involving the Dogon and Peuhl communities in their respective areas. Human Rights Watch is not in a position to confirm the incidents, which all merit further investigation.

An elder from Koro said, “I know of 15 cases in my cercle in 2019, including a shepherd named Yussouf, who was killed by the Fulani in Kassa commune in mid-August, and another on September 1, killed near Ogoyerou. They left but never returned, and later we found their bodies, riddled with bullets.”[122]

A man from Douentza cercle said, “My father had gone out to forage for wood in mid-August near Tedjie village – he made his living selling firewood – but he never returned. Tension had been rising – there’d been killings back and forth in recent months. He was a simple man and didn’t have anything to do with an armed group. Hours after he should have returned, we went out searching and found him, shot in the forest just a few kilometers from our village. My heart still aches.”[123]

Violence by Armed Islamist Groups in Mopti Region

Armed Islamist groups active in central Mali have massacred civilians in their villages, abducted and executed local leaders, dragged off and shot civilians from public transportation vehicles because of their ethnicity, and indiscriminately planted improvised explosive devices.

Human Rights Watch documented the alleged killing by armed Islamist groups of 116 civilians in central Mali in 2019. The vast majority of victims were ethnic Dogon or Tellem – a small ethnic group residing in and around the town of Yoro in Koro cercle. Most of the attacks appeared to target individuals or communities for their perceived support of or allegiance to the government or Dogon militias. The incidents documented took place in Bandiagara, Bankass, Douentza, Koro et Mopti cercles.

Villagers also said that armed Islamist groups had destroyed local business, looted large quantities of livestock, and forbade farmers from planting their fields. These abuses disproportionately occurred in towns and villages near Mali’s border with Burkina Faso.

Alleged Perpetrators

A patchwork of Islamist armed groups with shifting and overlapping allegiances are active in central Mali. These groups are heavily composed of Peuhl men from Mali, and to a lesser extent Burkina Faso and Niger, though numerous witnesses described the presence of armed Islamists from the Dogon, Songhoi, Tuareg and Bella ethnic groups. Community members in central Mali refer to these groups as “jihadists,” “assailants,” “terrorists,” “the men of the bush,” “the men in turbans,” or “the bizarre men.”

The groups include the Katibat Macina (or Macina Liberation Front) and Katibat Serma, both led by Hamadoun Koufa Diallo, a Peuhl preacher from Mopti Region who has been associated with Al-Qaeda-linked groups. In November 2019, the US Department of State named Koufa a Specially Designated Global Terrorist.[124] Other groups include: Ansaroul Islam, a Burkinabè Islamist armed group, founded in late 2016 by the late Ibrahim Malam Dicko and now led by his brother, Jafar Dicko[125]; and to a lesser extent the Islamic State of the Greater Sahara (ISGS), which emerged in 2016 and is present in some areas bordering Burkina Faso.[126]

In 2017, the Katibat Macina and four Al-Qaeda-linked groups in Mali merged under the name Jama'at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM),which means “Group for the Support of Islam and Muslims.” It is led by Iyad Ag Ghaly, a long-time Tuareg jihadist and leader of the armed Islamist group Ansar Dine.[127] Ansaroul Islam is informally linked to and supported by JNIM.[128]

These groups have claimed responsibility for attacks on military targets but rarely for attacks on civilians. However, witnesses and community leaders believed they were responsible for several reasons: armed Islamists had frequented and held meetings in and around their villages; the armed Islamists identified themselves as such before the attacks; some witnesses identified perpetrators they knew had joined Islamist groups; several witnesses had received letters or phone calls from men identifying themselves as members of armed Islamist groups threatening to perpetrate attacks; and witnesses had observed the distinctive way they dressed and the presence, in some attacks, of armed men apparently from other regions or countries.

June 2019 Massacres in Yoro and Gangafani II

On June 17, dozens of heavily armed Islamists executed at least 38 civilians from the neighboring villages of Yoro and Gangafani II, in Koro cercle near Mali’s border with Burkina Faso. A Human Rights Watch researcher spoke with 15 witnesses to the near-simultaneous attacks and was shown photographs that witnesses had taken of victims and their destroyed property. All the victims were from the Dogon and Tellem ethnic groups.

The witnesses said both attacks occurred around 4 p.m., and that many of those killed were intercepted while returning from their fields while others were killed in their homes or while trying to flee. There was no presence of state security forces in either town at the time of the attack.

Several witnesses identified some of the perpetrators as residing in local hamlets and villages. The attack occurred only days after Islamists had delivered a threatening letter, described by people who read it as an ultimatum. “A dozen Jihadists rode in on six motorcycles and gave a letter to an elder, asking that it be delivered to the local chief,” a witness said. “Later, the chief called people together and read it… Basically it said, ‘Are you with us or are you with the government of Mali?’”[129]

The witnesses said armed Islamists had frequented their area for several years without harming the civilian population. “Since 2017, they used to pray every so often in the village,” a farmer from Yoro said. “We used to see them passing by; each of us would raise our hands in greeting, and that was it.”[130]

Witnesses identified three factors that provoked the attacks: plans by the Malian army to establish a military camp in the area; efforts by some local residents to form a self-defense group; and two recent cross-border operations in Yoro and Gangafani II by the Burkina Faso army, during which dozens of Peuhl suspects had been detained and, the witnesses said, executed by the Burkinabè forces. “It was after all those Peuhl were killed by the Burkinabè, and government representatives had come to inspect a site for a new army camp, that our problems started,” a Gangafani II resident said.[131]

Witnesses from Gangafani II described seeing the bodies of up to 19 villagers executed during the attack. A farmer described the perpetrators: “From my field I saw a convoy of 22 motorcycles, two jihadists on each, all with turbans, some dressed in camouflage, others in black, some in boubous, with gray or brown turbans, and armed with belts of bullets on their chests. They had AK-47s, machine guns, and some had guns with tripods.”[132]

From where he hid, a villager described the shooting of 12 villagers near Gangafani II:

The bad men stopped people returning from their fields or from grazing their animals; some of us were on foot, others in donkey carts. I was terrified… they had big guns with strings of bullets. One donkey cart was full of people… they forced the men out and told about eight children to stand to one side – as if to make them watch. When they’d gathered 12 people including a 17-year-old, they told them to sit down and then started firing. They spoke in Pulaar [a Fula language] and said “Allahu Akbar” as they killed them.[133]

A man whose close family member died of injuries from the attack said:

It rained heavily that night, and in the morning, we all went to our fields to prepare the land for planting. As my [family relation withheld] headed back from our field, two kilometers from Gangafani II, he said, “I’ll see you at home soon.” I left a bit later. On the way I heard one, two, three gunshots and knew something bad was happening. I hid in a neighboring village for a few hours, and later found 12 people dead, their bodies 800 meters from the village. All were men except one 16-year-old shot in the back, like he was trying to run. My family member was wounded – he died at 3 a.m. Before he died, he said, “You must flee…There is no way of fighting them [the armed Islamists]… They are too well armed.”[134]

A village elder who participated in the burials said, “They killed 19 people that day – I buried all of them. I saw nine bodies one kilometer from the village, three others nearby, three more to the west and a few elsewhere. All were male and several were children, including a boy and his father.”[135]

Human Rights Watch spoke with seven witnesses to the killings in Yoro. A farmer described the attack:

From 2017, we didn’t have a problem with these people. When we saw them, they’d say, “I didn’t see you, you didn’t see me… don’t tell the army where we are.” But the plan to build a FAMA camp and the Burkinabè killing of the Peuhl changed things. The attack started at 4:20 p.m., after [the late afternoon] prayer…First shots came from near the school, then all around us. I’d been chatting with two friends and as the shots started, they took off running for home, but the jihadists were advancing, firing, and they shot them from 10 meters away. I saw them firing and firing like mad…Bullets whizzed by, entering my house and hitting my motorcycle.[136]

A man wounded in the attack said he knew 16 people who were killed: “four from my family, six in my uncle’s neighborhood, and another six elsewhere. One 42-year-old man grabbed his 4-year-old and hid in his house, but the child cried out, alerting the jihadists, who kicked in the door, dragged him out and shot him in the head, in front of his children. Two of my nephews and my cousin were killed near the market.”[137]

Another villager said, “I was fixing the roof of my house when the attack started, and then friends ran by saying they’d just seen the bizarre men [jihadists] coming towards us. I rushed down and hid, and minutes later saw them pass by, dressed in turbans and with sophisticated arms used in wars including machine guns with bandoliers.”[138]

A market woman described the attempted execution of a man the jihadists had forced off his motorcycle: “They kept accusing him of belonging to a self-defense group, which didn’t exist in our village! The youth kept saying, ‘No, I don’t know anything about this, I’m just a trader,’ but they ordered him to lie face down and shot him three times. They left him for dead.”[139]

The jihadists returned to both villages the next day as villagers were preparing to flee. Witnesses said that armed Islamists looted and burned the villages, stole hundreds of livestock and killed at least four people they found in or near the villages. A Gangafani II resident said, “Those who’d come from surrounding villages to help bury our dead and offer condolences had just left when the jihadists returned. They fired in air and looted stocks of grain, everything in the shops, and hundreds of our animals, everything except a few chickens.”[140]

A farmer described the second attack on Yoro: “The jihadists pillaged the shops and stole every camel, cows, goat and sheep - only the dogs were not taken. My family lost 400 animals. The village tried to save some by sending a small group of shepherds to recuperate any animals we could, but three of our family members were caught and killed by the jihadists.”[141]

Executions, Abductions of Men from Public Transport Vehicles

On September 8, 2019, six armed Islamists stopped three vehicles on an isolated section of the main road between Koro and Bandiagara towns. After forcing over a dozen passengers out, they executed seven men, apparently on the basis of their ethnicity. A woman, two children and a Peuhl man were spared. One of several men who survived the incident by fleeing the scene under gunfire said:

Arriving at a wooded patch on the road, four armed men jumped out and fired in the air, forcing the driver to stop. They ordered us about 25 meters off the road where we found that two more jihadists had stopped another car from a local bakery with two passengers, who were both face down with their eyes and hands bound. They screamed at us to lie face down next to them. Minutes later a third vehicle was brought. The jihadists spoke Pulaar and had camouflage dress with vests, rangers [military boots], and AK-47s. Two were near the vehicles and the other four carried out the operation.

They yelled at us to give up our phones and started asking where we were from. One passenger was a Peuhl…I heard them saying, “You will not die today.” [I later learned] he was abducted but let go a day or so later. One man, seated next to me in the car, said he’d come from Burkina Faso, but they checked his ID and found he was lying. He was actually a Dogon who worked with an NGO [nongovernmental organization]. Immediately, they shot him in the head… One of them said, "You’re all going to die here." They killed a second one, one of those from the bakery, shot in the head like the first one. Since they hadn’t tied those of us in the second group, a few of us bolted into the bush, bullets whizzing by as we did. Later we saw the photos of those who died…all shot in the head. The victims were four Dogons, two Songhoi and one Mossi. They didn’t ask for money, and later burned the cars and all our baggage, so this wasn’t a robbery.[142]