Summary

“This free speech that we enjoyed for a while is over, and we are now back to the pre-2005 era. Only, instead of the Syrian army, we have the Lebanese state.”

Hanin Ghaddar, Lebanese journalist.

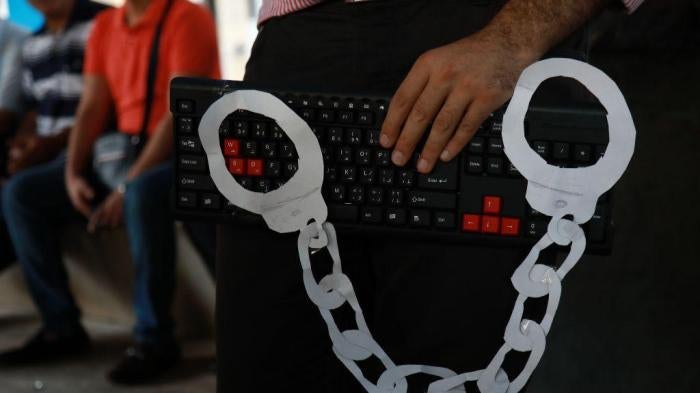

In recent years, Lebanon’s criminal defamation laws have been used against journalists, activists, and other citizens who have written about corruption by public officials, reported misconduct by security agencies, criticized the current political and economic situation, or exposed abuse against vulnerable populations.

Although Lebanon is perceived to be one of the Arab world’s freest countries, over the past few years, the country has witnessed an alarming increase in attacks on peaceful speech and expression. This has coincided with expressions of popular disillusionment with corruption, the mismanagement of public funds, and a worsening economic situation. Powerful political and religious national figures have instrumentalized the country’s criminal defamation and insult laws to silence nonviolent criticism, especially against those leveling accusations of misconduct or corruption.

Lebanon’s constitution guarantees freedom of expression “within the limits established by law,” and Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which Lebanon ratified in 1972, provides that “everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression.”

However, the Lebanese penal code criminalizes defamation against public officials and authorizes imprisonment for up to one year in such cases. It also authorizes imprisonment for up to two years for insulting the president, flag, or national emblem. The military code of justice prohibits insulting the flag or army, an offense punishable by up to three years in prison. Other laws outlaw speech deemed insulting to religion or speech that incites sectarianism.

Although these Ottoman and French laws have been on the books since the early 20th century, evidence reviewed by Human Rights Watch shows an exponential increase in their use, particularly targeting online speech. Established in 2006, between January 2015 and May 2019, the Anti-Cybercrime and Intellectual Property Rights Bureau (Cybercrimes Bureau) – the unit within the Internal Security Forces specialized in combatting cybercrime and enhancing online security – investigated 3,599 cases relating to defamation, libel, and slander. In 2015, the bureau investigated 341 such cases. The number increased to 755 the following year, and 800 the year after. In 2018, however, the bureau investigated 1,451 defamation cases – an increase of 81 percent from the previous year and 325 percent from 2015. The sharp increase in 2018 appears to be related to attempts to control critical speech ahead of the May parliamentary elections. In 2019, as of May 15, 252 defamation cases were referred to the Cybercrimes Bureau for investigation.

The criminal courts have issued prison sentences against at least three individuals in defamation cases between 2015 and 2019. One of those individuals received 9 prison sentences in absentia in 9 different criminal cases filed against him by the same politician. The Publications Court has issued at least one in absentia prison sentence between 2015 and 2019. During the same period, the military courts have issued three in absentia prison sentences, two of which were revoked on appeal after the military courts declared a lack of jurisdiction.

The cases investigated by Human Rights Watch show that the laws have been used to silence speech that is not only legitimate, but necessary for the functioning of a vibrant society governed by the rule of law.

For example, Michel Kanbour, a Lebanese journalist and founder of the online newspaper Lebanon Debate, told Human Rights Watch that public officials had sued him for defamation around 20 times since 2015, the majority resulting from his reporting on corruption and misconduct by public officials. In March 2018, the Publications Court sentenced Kanbour to six-months imprisonment and a fine of 10 million Lebanese pounds ($US6,667) in absentia for accusing the Director General of a state institution of corruption. “In 2019, it is a disgrace that our judges issue rulings for imprisoning journalists,” Kanbour said. “The only reason that can justify imprisoning a journalist is inciting violence. Supposedly insulting someone shouldn’t.”

In another infamous case, on January 10, 2018, the Military Tribunal sentenced Lebanese journalist and researcher Hanin Ghaddar in absentia to six-months imprisonment for criticizing the Lebanese army in comments she made during a conference in Washington, DC. Although the Military Tribunal dropped its verdict against Ghaddar and referred her case to the Publications Court on April 10, 2018, citing a lack of jurisdiction, Ghaddar stated that the message was clear: “This free speech that we enjoyed for a while is over, and we are now back to the pre-2005 era. Only, instead of the Syrian army, we have the Lebanese state.” The Military Prosecutor initiated cases against at least 17 other journalists between October 2016 and September 2019.

Security agencies interrogated several other individuals, including political commentator Hani Nsouli, journalist Ahmad Ayoubi, and activist Mohammad Awwad, for expressing their political opinions and analysis, which were deemed by some powerful local individuals to have been insulting to them or their reputations. In a case that provoked public outrage, security forces arrested 80-year-old Daoud Moukheiber a day after a video of him protesting the government’s decision to install high-voltage power lines through his town proliferated on social media. In the video, Moukheiber is seen using strong language against the president and two ministers – all members of the same party – to express his anger and disillusionment with the government’s encroachment on his basic rights.

In another incident, a prosecutor ordered Human Rights Watch and several other local publications to remove reporting on the alleged abuse of a migrant domestic worker in Lebanon pursuant to a defamation case filed by the worker’s employers.

In all the criminal defamation cases that Human Rights Watch investigated, the authorities behaved in ways that suggested bias in favor of the powerful individuals who had initiated the lawsuits, illustrating the potential for public officials, religious groups, and security agencies to misuse criminal defamation laws as a tool for retaliation and repression rather than as a mechanism for redress where genuine injury has occurred. The prosecution has applied the laws selectively, and security agencies have sometimes acted without a judicial order.

Human Rights Watch also recorded procedural irregularities at every stage of the investigation in the criminal defamation cases it documented. The prosecution and the security agencies often did not follow standard procedures, and in many instances expressly violated the law. Many individuals sued for defamation were arrested violently by armed guards in ways that are vastly disproportionate to their alleged crime. For example, around 10 armed police officers from the Internal Security Forces stormed the offices of the online publication Daraj and arrested its co-founder and editor-in-chief Hazem al-Amin in connection with an already dropped lawsuit against Daraj for alleging that the son-in-law of a leading politician was evading taxes. “The way they were driving in the street, with the sirens and the convoy, it’s as if they caught Abu-Bakr Al-Baghdadi [the Islamic State leader],” al-Amin told Human Rights Watch.

Interviewees said interrogators used tactics that were physically or psychologically violent. On some occasions, defendants said interrogators violated their right to privacy and looked through their phones and social media accounts without a judicial order.

Interrogating agencies often pressured individuals to sign pledges promising not to write defamatory content about the complainant in the future or to remove their offending content immediately, in violation of their free speech and due process rights. Individuals were forced to sign these pledges before ever appearing before a judge and presenting their defense and sometimes without any charges being brought.

Between January 2015 and May 2019, the Internal Security Forces’ Cybercrimes Bureau released 1,461 individuals after an investigation after obtaining a “proof of address,” including individuals who pledged not to insult or write defamatory content about the complainant in the future and remove the offending electronic content. The Internal Security Forces (ISF) told Human Rights Watch that six individuals refused to sign such a pledge.

Lebanese lawyers agree that these pledges have no legal bearing. Nizar Saghieh, the co-founder and executive director of the regional rights group The Legal Agenda, told Human Rights Watch:

This is particularly outrageous. Here the purpose isn’t to get someone to trial, which is public. But just when you want someone to take back something that they said, in private, in a police station. In these cases, the individual is convicting himself before he even appears before a court. And it is taking away his right to a defense. A lot of cases end at this stage, after the person apologizes or signs a pledge. This dimension is evidence of a high degree of repression. Here, you are silencing people rather than punishing them.

Nine individuals interviewed by Human Rights Watch were placed in pretrial detention in relation to defamation charges. Pretrial detention is only permissible in Lebanon for offenses that are punishable by more than one-year imprisonment. Even where pretrial detention is permissible, international human rights law says it should be the exception, not the rule. Lebanon’s Code of Criminal Procedure also states that it should be the exception and only used where necessary to preserve evidence, protect the defendant, or preserve security. There is no indication that the judiciary assessed the necessity of holding individuals in pretrial detention. Further, some interviewees told Human Rights Watch that they believed the complainants or the public prosecution were adding additional articles for which the punishment exceeded one-year imprisonment to justify pretrial detention in defamation cases. While those additional charges were subsequently dropped for lack of evidence, they did result in security agencies detaining them pretrial.

In reviewing speech-related prosecutions in the criminal courts, Publications Court, and military courts, Human Rights Watch documented concerns regarding the training, independence, and impartiality of the judiciary, and some judges’ failure to adequately consider the public interest in the cases before them.

The executive branch has extensive influence in the selection and appointment of judges, undermining the courts’ independence and impartiality. And although the Publications Court was established to look into “publishing crimes,” experts have criticized the appointments to the court for not considering expertise, competence, or merit. Experts also told Human Rights Watch that they are not aware of any systematic training that judges appointed to the Publications Court receive on international standards and best practices relating to freedom of expression.

Lawyers who have defended individuals in defamation cases, as well as free speech experts, say that because judges in the Publications Court are not well versed on international free speech standards, they apply the law literally, and are sometimes unable to effectively balance the public interest resulting from the criticism of public officials with the right of an individual to protect their dignity. Some lawyers have jokingly referred to the Publications Court as the “morality court.”

However, Lebanese lawyers have noted that some judges – particularly newly-appointed judges – are starting to issue positive rulings in speech cases and setting good precedents for future prosecutions, in some cases citing and applying international human rights law and standards.

Although few individuals have served prison time on defamation charges, those subject to criminal prosecution have told Human Rights Watch about the negative impact of simply facing criminal investigations and trials. Defendants in criminal defamation cases interviewed by Human Rights Watch endured a number of difficult consequences as a result of the charges against them. Some were forced into self-imposed exile for fear of arrest or harassment upon return to Lebanon, causing stress and hardship to themselves and their families. Others endured professional consequences as a result of the claims against them including reporting being unfairly dismissed from their job. Many do not hear from the prosecution for long periods of time, leaving them confused as to whether the cases against them were still active or not. The fines and other sanctions resulting from the criminal process have also had a significant financial impact on many defendants and the publications they work for.

The use of criminal defamation laws has had a chilling effect on free speech in Lebanon. Many of the individuals interviewed by Human Rights Watch reported self-censoring after their often-intimidating experiences resulting from defamation lawsuits. Others noted the increasing use of criminal defamation laws has created a hostile environment in Lebanon for free speech and deterred others from writing freely. When citizens face possible prison time or trials in military court for complaining about official performance, corruption, or security service misconduct, other citizens have told Human Rights Watch that they take notice and are less likely to draw attention to such problems themselves, undermining effective governance and a vibrant civil society.

International human rights law allows for restrictions on freedom of expression to protect the reputations of others, but such restrictions must be necessary and narrowly drawn. Together with an increasing number of governments and international authorities, Human Rights Watch believes that criminal penalties are always disproportionate punishments for reputational harm and should be abolished. As repeal of criminal defamation laws in an increasing number of countries shows, such laws are not necessary: civil defamation and criminal incitement laws are sufficient for the purpose of protecting people’s reputations and maintaining public order and can be written and implemented in ways that provide appropriate protections for freedom of expression.

Human Rights Watch calls on the Lebanese parliament to repeal the defamation provisions in the Penal Code and replace them with civil defamation provisions, and to amend the new proposed media law to remove all prison sentences for speech crimes.

Methodology

Research for this report was conducted between March 2019 and September 2019. Human Rights Watch conducted 42 interviews with victims of laws criminalizing free speech, including journalists and activists, as well as lawyers, government officials, and experts on free speech and members of local civil society organizations. Many interviewees shared arrest warrants, investigation reports, and court documents with us.

Most of our interviews were conducted in Beirut, as we relied on public reporting to identify victims of the criminal defamation laws, and then used snowball sampling to identify further individuals to speak with. Our sample is not reflective of the overall number of cases in Lebanon as a whole. However, local civil society groups working on freedom of expression believe that the majority of criminal defamation cases are taking place in Beirut. The interviews were conducted in Arabic and English.

Human Rights Watch informed all interviewees of the nature and purpose of our research, and our intentions to publish a report with the information gathered. We informed each potential interviewee that they were under no obligation to speak with us, that Human Rights Watch does not provide legal or other assistance, and that they could stop speaking with us or decline to answer any question with no adverse consequences. We obtained oral consent for each interview, and interviewees did not receive material compensation for speaking with Human Rights Watch.

As part of our research, we attempted to obtain statistics regarding the number of criminal defamation investigations and prosecutions from the Public Prosecutor, the Internal Security Forces’ Cybercrimes Bureau, the Ministry of Justice, the criminal courts, the Publications Court, and the Military Court. Only the Military Court and the Internal Security Forces provided us with substantive responses to our requests for information.

The Ministry of Justice responded to our request stating that since the courts do not have an electronic information system, they are unable to provide us with the statistics we requested without committing additional resources to the task. The ministry, however, said it would welcome an initiative by Human Rights Watch to commit the necessary human and financial capital to obtain the statistics. The Office of the Public Prosecutor also told Human Rights Watch that because their records are not digitized, they are not able to provide us with the information we requested.

Despite numerous attempts to follow up with the Publications Court and the criminal courts, we received no replies to our inquiries.

Human Rights Watch’s letters and the responses received are attached in this report’s appendix.

Human Rights Watch reviewed Lebanon’s relevant legislation, including the Penal Code, the Code of Criminal Procedure, and the Publications Law, and consulted with Lebanese lawyers on the ways in which the laws have been interpreted and applied.

We also met with parliamentarians who were in the process of proposing amendments to a draft media law being debated in parliament and shared our recommendations with them.

This report was researched and written in close consultation with local civil society organizations who have been documenting free speech violations for many years, including Maharat Foundation, Samir Kassir Foundation, The Legal Agenda, Social Media Exchange (SMEX), and ALEF.

Human Rights Watch does not take a position on whether the conduct in which the individuals profiled in this report engaged in constitutes defamation. Rather, we oppose Lebanon’s classification of such nonviolent conduct as potential criminal offenses.

I. Background: Restriction of Space for Free Speech in Lebanon

Lebanon’s constitution explicitly protects freedom of expression. Article 13 states “the freedom to express one’s opinion orally or in writing, the freedom of the press, the freedom of assembly, and the freedom of association shall be guaranteed within the limits established by law.”[1]

In the past in Lebanon journalists and citizens have usually been free to criticize politicians openly.[2] However, over the past few years, Lebanon has witnessed an alarming increase in attacks on peaceful speech and expression, which many analysts have linked to the 2015 garbage crisis, during which the government’s mismanagement of waste led to garbage piling up on the streets of Beirut.[3] A popular movement under the banner “You Stink” called for sustainable solutions to the garbage crisis and an accounting for political corruption in the country.[4] The movement mobilized widespread demonstrations against the government’s dysfunction and corruption in July and August 2015. Security forces used excessive force against protesters, and witnesses told Human Rights Watch that police fired water hoses without warning and kicked protesters, beat them with batons, and used rubber bullets, tear gas canisters, water cannons, and the butts of rifles.[5]

The garbage crisis demonstrated the prevalent discontent with the establishment political parties and inspired independent candidates, primarily from civil society, to run in Lebanon’s May 2016 municipal elections and subsequently in the May 2018 parliamentary elections.[6]

Countless protests have been organized by civil society, independent parties, and labor unions in cities and towns across Lebanon.[7] Demonstrators protested rampant corruption, the misuse of public funds, the worsening economic situation, and the austerity measures proposed by the government.

Lebanon’s power-sharing system and weak central institutions have given rise to clientelist patronage networks and the misuse of public office and public funds for personal gain.[8] In a 2018 study, the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies (LCPS) found that 98 percent of Lebanese citizens believe that corruption is a very large or somewhat large problem in Lebanon, with more than 75 percent of respondents stating that corruption has strongly or somewhat increased in the past two years.[9]

Despite widespread perceptions about the prevalence of corruption in Lebanon, there has been little accountability for public officials accused of financial misconduct or corruption.[10] Legislation passed by parliament to combat corruption and increase transparency, such as the Access to Information Law (February 2017) and a law protecting whistleblowers (September 2018), have no enforcement mechanisms and have yet to be implemented fully.[11]

Instead of committing to tackling corruption, members of the powerful and wealthy political elite have responded to threats to the status quo with repression and politically motivated prosecutions, particularly targeting individuals and journalists who are leveling accusations of corruption.[12] In a telling statement, on March 16, 2017, then-Deputy Speaker of Parliament called on the Lebanese state to “pursue those holding signs insulting the members of Parliament, prosecute them, and arrest them.”[13]

One of the key tools used by Lebanon’s powerful political elite to silence criticism has been the country’s criminal defamation laws, which authorize imprisonment of up to three years for criticism of the army, president, and public officials. Although the laws, which originated during the Ottoman and French colonial eras, have been on the books since the early 20th century, evidence reviewed by Human Rights Watch shows an exponential increase in their use, particularly targeting online speech.

The former Justice Minister, Salim Jreissati, who was in his position between 2016 and 2019, has repeatedly denied that freedom of expression was under attack or that senior members of his party, the Free Patriotic Movement, supported prosecutions under the defamation laws.[14] Both the president, who assumed power in October 2016, and the foreign minister, who has filed a large number of the defamation cases documented in this report, are members of the Free Patriotic Movement. Jreissati added that the president had personally asked him and the public prosecutor not to initiate cases against individuals who expressed an opinion against him.[15] Evidence presented in this report shows that, if true, this directive was not adhered to.

In a majority of the cases discussed in this report, the criminal defamation complaints were filed by powerful local individuals to silence individuals who had made allegations of corruption, fraud, or misconduct. In most of these cases, the investigations conducted into the defamation charges appeared to contain procedural irregularities or behavior that suggested bias.

II. The Legal Framework: Criminal Defamation Law in Lebanon

Criminal defamation laws prohibit individuals from injuring the reputation of another person in the form of a spoken statement or in writing. In some countries, including Lebanon, “insult” laws specifically criminalize expressions deemed to offend the honor of public officials and institutions, in some cases even if the allegations were proven to be true.[16] Defamation laws, which are intended to protect honor and reputations, are distinct from incitement laws, which are intended to serve the purpose of maintaining public order, and prohibit forms of expression that are intended and likely to provoke crimes, such as imminent violence.

Many states have adopted some form of defamation law to protect individuals from unwarranted attacks on their reputations. Some only have civil defamation laws, meaning that individuals who believe they have been defamed may have access to a judicial remedy, but as a private actor, on their own initiative. If an individual is found guilty of civil defamation, they may be required to pay compensation to the defamed party or to take other measures such as publicly retracting the defamatory statement. Other states, including Lebanon, have criminal defamation laws, meaning that individuals may file a claim alleging defamation with the police, and the police and prosecutors will then use public funds to investigate the case on behalf of the state. The courts can punish those found guilty of defamation with fines or even imprisonment.

Penal Code

Lebanon’s penal code defines what it considers to be a means of publication, and subsequent articles criminalize defamation and insults that appear in one of those means of publication, which include actions, speech, and writing in a public forum.

Insults

Article 383 criminalizes insulting or threatening a public employee while they are doing their job by up to six-months imprisonment.[17] If the employee against whom the insults were directed was a public official, the punishment is two months to one-year imprisonment. If the insults were directed at a judge, the punishment is six months to two-years imprisonment.

Article 384 sets a penalty of six months to two-years imprisonment for insulting the president, flag, or national emblem.[18] Insulting religious rituals is also punishable by six months to three-years imprisonment.[19]

Insulting a foreign state, its head, or its political representatives in Lebanon is punishable by six months to two-years imprisonment and a fine up to 400,000 Lebanese pounds (US$267).[20]

The truth is not an applicable defense with regards to insults.

Slander

Slander (tham) is every attribution that attaches an action to a person or institution that can offend their honor or dignity.[21]

Slander directed against the president incurs two months to two-years imprisonment; against the courts, organized committees, army, or public administrations, up to one-year imprisonment; against public officials acting in their official capacity, up to six-months imprisonment; and against public employees against whom the alleged slander is related to the exercise of their office, up to three-months imprisonment or a fine between 20,000 and 200,000 Lebanese pounds ($13 – 133).[22] The penal code also sets penalties for slander directed against private citizens up to three-months imprisonment and a fine up to 200,000 Lebanese pounds ($133).[23]

The truth is a defense in slander cases only if the slander was directed at a public official or employee.[24] The truth is not a defense in all other cases of slander, including when directed at the president and at private citizens.[25]

Libel

Libel (qadh) is every word of contempt, profanity, or insult that appears in a means of publication and is directed against an individual or institution. Because libel does not entail attaching an action to somebody, it is not subject to the truth defense.[26]

Libel is punishable by one month to one-year imprisonment if directed against the president; up to six months for libel against the courts, organized committees, army, public administration, public officials acting in their official capacity; and a fine of between 20,000 to 200,000 Lebanese pounds ($13 – 133) or arrest for libel of public employees against whom the alleged libel is related to the exercise of their office.[27] Insults, slander, and libel against judges not acting in their official capacity are punishable by up to six-months imprisonment.[28]

The penal code also sets penalties of between one week and three-months imprisonment or a fine of between 50,000 and 400,000 Lebanese pounds ($33 – 267) for libel of private citizens.[29]

Incitement Provisions

Article 317 of the penal code punishes any acts or words, spoken or written, “intended to or resulting in instigating confessional or racial bigotry, or that provoke conflict between the sects” by one year to three-years imprisonment and a fine ranging from 100,000 to 800,000 Lebanese pounds ($67 – 533). In these cases, an individual may also be deprived of some civil rights, including the right to assume employment in administrations related to one’s religious confession or to one’s labor union and the right to vote or be elected to all union and confessional organizations.[30]

The provision does not specify what “confessional or racial bigotry” entails, nor does it require that the speech be likely to, or even intended to, incite discrimination, hostility, or violence. A law that is so vague that individuals do not know what expression may violate it has a chilling impact on free speech because citizens may avoid discussing any subject that they fear might subject them to prosecution. Vague provisions not only do not give sufficient notice to citizens, but also leave the law subject to abuse by authorities who may use them to silence dissent.[31] If a criminal law is not clearly defined so that anyone can predict what acts would constitute a crime, it will be arbitrary under international human rights law.

Military Code of Justice

Individuals who insult the flag or the army, or insult “its dignity, reputation, and morale, or do anything that weakens order in the military or that undermines subordination to superiors or respect owed to them” can be punished by three months to three-years imprisonment under Article 157 of the Military Code of Justice and subject to trial in military courts.[32] The truth of the statements being made is not a defense in these cases.[33]

The vague and overbroad language of this article violates Lebanon’s obligations under international law, which prohibit restrictions on freedom of expression on national security grounds unless they are strictly construed, and necessary and proportionate to address a legitimate threat.

The Military Code of Justice also stipulates that the provisions of the Penal Code can be applied in the military courts if the alleged defamatory statement or content is directed at any member of the military institution.[34]

Publications Law

The printed press in Lebanon is governed by the Publications Law of 1962 (also referred to as the Press Law), which was amended by legislative decree no. 104/1977 and subsequently by law no. 330/1994.[35] The Publications Law clearly defined the practice of journalism and what is to be considered a “publication” and thus subject to the law’s provisions.[36]

The Publications Law established a special court at the appeals level – the Publications Court – with jurisdiction over all cases related to publication crimes, including defamation. The decisions of the Publications Court are only subject to one level of appeal, at the Publications Court of Cassation.[37] The Publications Court is bound by the Code of Criminal Procedure, and it applies the provisions of the Penal Code regarding crimes that are not referred to in the Publications Law.[38] The law, does, however, prohibit pretrial detention for all publishing crimes.[39]

Although the Publications Law provides that the press shall be free, it places restrictions on the freedom of the press and sets significant prison sentences and fines for violating these restrictions.[40] Article 12 of the law prohibits publishing anything that is “contrary to morality and public morals,” punishable by a fine of 100,000 to 300,000 Lebanese pounds ($66 – 200).[41] Article 23 prohibits defaming or insulting the dignity of the Lebanese president as well as the president of any foreign state,[42] punishable by imprisonment between two months to two years and a fine of 50 million to 100 million Lebanese pounds ($33,333 – 66,666).[43]

The law further prohibits the publication of anything that contains an insult to one of the recognized religions in the country and that would instigate confessional or racial bigotry, disrupt the public peace, or jeopardize the integrity, sovereignty, unity, or borders of the state or its external relations.[44] Committing one of the vaguely defined and overbroad offenses listed in the article could result in imprisonment from one to three years, and a fine from 50 million to 100 million Lebanese pounds ($33,333 – 66,666).[45]

The defamation provisions in the Publications Law also set the penalties for insults, libel, and slander, as defined in the Penal Code. Insulting, slandering, or committing libel against a public employee acting in his official capacity is punishable by one month to six-months imprisonment and a fine between 60,000 Lebanese pounds and 100,000 Lebanese pounds ($40 – 67). The penalties are greater if the defamation was directed against a public official (three months to one-year imprisonment and a fine up to 200,000 Lebanese pounds ($133)) and a judge (one to two-years imprisonment and a fine up to 200,000 Lebanese pounds ($133)).[46] Slander (tham) directed against other individuals or legal entities is punishable by three months to one-year imprisonment and a fine,[47] and libel (qadh) by one month to six-months imprisonment and a fine.[48] As discussed above, the truth is only a defense in cases of slander directed against public officials and employees.[49]

Electronic and Social Media

Lebanon does not currently have any law regulating publishing on the Internet, including on online blogs and social media.

The absence of a regulatory framework for online speech has led to confusion over whether online forums should be considered publications and therefore subject to the Publications Law, or whether they are excluded from the definition of a publication under the law and as such subject to the Penal Code and under the jurisdiction of the criminal courts.

Judges in the Publications Court have issued contradictory rulings in this regard. On October 10, 2016, the Publications Court of Cassation ruled on appeal that the Publications Court has no jurisdiction over content published on Facebook, overturning the lower court’s judgment that Facebook can be considered a publication and therefore subject to the jurisdiction of the Publications Court.[50] Despite this ruling, some judges in the Publications Court continued to accept defamation cases about social media posts.[51]

Although the Publications Law places some restrictions on the press, it also affords certain guarantees.[52] The Publications Law prohibits pretrial detention for all speech crimes that occur in a medium covered by the law, regardless of the sentence that they carry.[53] By contrast, the Penal Code allows for pretrial detention for crimes that result in imprisonment longer than one year.[54]

Further, the Publications Law stipulates that only an investigative judge can interrogate or question an individual accused of crimes that appear in the Publications Law, and they must refer the case to the Publications Court within five days.[55] Lawyers are allowed to be present during a questioning with the investigative judge.[56]

Security agencies are not allowed to conduct interrogations in cases covered under the Publications Law, thus mitigating the risk that individuals will be subjected to the intimidation, abuse, and privacy violations described in Chapter 7. Lawyers are not usually permitted to be present during questionings with the security agencies (See Chapter 7).

The inconsistency with which online speech is dealt with in the courts not only deprives individuals from vital protections guaranteed in the Publications Law, but also risks subjecting individuals to prosecutions before several courts for the same statement. For example, if someone writes alleged defamatory content in an article that is published on an online newspaper, they could potentially face trial in both the Publications Court and the criminal court.[57]

Electronic Transactions Law

The Electronic Transactions and Personal Data Law (e-Transactions Law), Law 81, was adopted on October 10, 2018 and went into effect in January 2019.[58] It was intended to regulate online commerce while protecting the data and privacy of businesses and Internet users. Experts have criticized the law for failing to comply with the latest data protection regulations and granting a number of ministries broad jurisdiction over the handling of personal data.[59]

The law amended Article 209 of the Penal Code, which defines what is considered a means of publication to explicitly recognize dissemination by “electronic means.” [60] However, some experts have criticized this provision, which makes no distinction between an individual’s private social media account and official social media pages that are intended to act as publications.[61] They claim that this blurs the boundaries between private and public interactions, and risks subjecting private online conversations to the provisions of the Penal Code.[62]

Article 126 of the e-Transactions Law grants the public prosecution the authority to “temporarily suspend certain electronic services, block websites or freeze accounts in such websites, for no more than thirty days.” This period may be renewed once through a “justified decision.” The Public Prosecution’s decisions are not subject to appeal.[63]

Experts told Human Rights Watch that this article is inconsistent with Article 125 of the same law, which only allows the courts to block websites in limited cases related to terrorism, child pornography, electronic fraud, and other serious national security grounds.[64] Since the judiciary has more authority than the public prosecution, they recommended that parliament amend Article 126 to bring it in line with Lebanese legal principles.[65]

New Media Law

The Lebanese parliament began discussing a proposal to amend the outdated Publications Law submitted by former parliamentarian, Ghassan Moukheiber, and Maharat Foundation, a Beirut-based NGO specializing in media and free speech issues, in 2010. The proposal was still being debated as of September 2019, but parliamentarians have promised to make efforts to pass the law by the end of 2019. Human Rights Watch reviewed a version of the law that was last amended in April 2019. In that draft, the law defined and regulated “electronic media,” and placed it under the jurisdiction of the Publications Court.[66]

Although the proposed law prohibits pretrial detention for all publishing crimes, including those on social media, the proposed law does not remove prison sentences for defamation and in some instances increases the prison penalties and multiplies the fines.[67] Under the April 2019 version of the proposal, slander and libel are punishable by up to three-months imprisonment or a fine between five times to fifteen times the minimum wage.[68] Truth is a defense only if the slander or libel was directed at a public employee and the statements were related to the exercise of their office, and only if the defendant can prove the veracity of the claims being made.[69]

The proposed law also imposes harsh penalties for insulting, slandering, or publishing any libelous material against the Lebanese president or the president of a foreign country (imprisonment from one to two years and a fine between 10 and 20 times the minimum wage) and ambassadors or heads of diplomatic delegations to Lebanon (half the penalties imposed for insulting the president).[70] The law also permits the Publications Court to “take the necessary measures” to stop the dissemination of the alleged defamatory or insulting content, without explaining what those measures are.[71] In these cases, the veracity of the statements is not a defense.

Further, the proposed law prohibits the publishing of any content that is deemed to constitute “insults to one of the recognized religions in Lebanon or that incites sectarian bigotry/tensions or endangers public order or puts the peace of the country, its sovereignty, its unity, its borders, or its external relations in danger.”[72] These crimes would be punishable by one to three-years imprisonment and a fine between 10 and 20 times the minimum wage. In case the crime is repeated, the penalty is doubled and the publication is suspended for “at least” six months.[73]

These articles in the proposed law constitute an unacceptable restriction on free speech, and if passed, would set Lebanon even further behind. Human Rights Watch has been advocating with members of Parliament to amend these articles so that they comply with international human rights law.

III. Use of Criminal Defamation Laws on the Rise

Although there is a consensus among civil society groups and journalists that the number of defamation cases has increased significantly in recent years, it has been difficult to obtain accurate statistics for the numbers of prosecutions initiated by the public prosecution and private individuals.[74]

The public prosecutor can initiate “public interest” cases regarding content that is deemed to be insulting to the president, inciting sectarian tensions, disturbing the public peace and endangering the sovereignty of the state, or disseminating false news about the military institution.[75] In these cases, the police and prosecutors will use public funds to investigate the case on behalf of the state.

Individuals, including public officials, members of the judiciary, and private citizens, can also file complaints to the public prosecution alleging defamation. The state is then obligated to use public funds to investigate the alleged crime.[76] However, individuals also have the right to bring a civil action for damages suffered as a result of the offense. They can join the prosecution as a civil party before the criminal courts.[77] If private individuals withdraw their lawsuit, the state’s case is also dropped. However, even if public officials withdraw their lawsuit, the state’s case remains ongoing.[78]

As discussed above, the prosecution can refer defamation cases to the Publications Court, for defamatory content that appears in the traditional press and some cases involving content on electronic and social media; to the criminal courts, for defamatory content that appears in electronic and social media; or to the Military Courts, for defamation via any medium against any member of the military institution.

Human Rights Watch requested statistics on the defamation cases initiated and referred to each of those courts. The Ministry of Justice failed to provide any relevant information on the cases referred to the criminal courts. In the response received, the President of the Higher Judicial Council stated that “Lebanese courts do not rely on automation in their work … thus, the courts do not currently have the capacity to prepare such statistics … without allocating new staff to this end.”[79]

The Publications Court did not respond to Human Rights Watch’s request for information, despite repeated attempts. However, Maharat Foundation, a Beirut-based NGO specializing in media and free speech issues, was able to obtain some figures from the court for 2018 and 2019. They found that in 2018, a total of 95 defamation and incitement cases were referred to the Publications Court. Of those, 73 were filed by the individuals who were defamed, and 22 were initiated by the public prosecutor in the name of the public interest.[80]

Between January and April 2019, 15 cases were referred to the Publications Court, of which 6 were public interest cases.[81] According to Maharat Foundation, the proportion of cases referred to the publications court in the same period decreased 45 percent between 2018 and 2019.[82] However, experts at Maharat Foundation attribute this decrease in large part to the increasing number of cases involving social media that are being referred to the criminal courts instead, as well as the exceptional uptick in prosecutions ahead of the May 2018 elections.[83]

There has been a noticeable increase in the number of cases initiated by the Military Prosecutor against individuals for defamation between 2016 and 2019. The Head of the Military Tribunal, Brigadier General Hussein Abdallah, provided Human Rights Watch with a list of 15 cases that the Military Prosecutor initiated between October 2016 and March 2019 relating to defamation and insult charges.[84] Human Rights Watch was able to identify three additional defamation cases filed by the Military Prosecutor between March and September 2019.[85]

According to Brigadier General Abdallah’s records, the military prosecutor initiated one speech-related case in 2016 and one 2017. In 2018, however, he initiated 10 such cases. In 2019, as of September, the military prosecutor had brought defamation cases against at least six individuals.[86]

The number provided by the Military Tribunal are not exhaustive. Brigadier General Abdallah told Human Rights Watch that there is no mechanism to filter through court records for cases specifically related to defamation, as the article most commonly invoked, Article 157, is not limited to defamation and encompasses any potential altercation between a civilian and a member of the military institution.[87] Therefore, Brigadier General Abdallah compiled this list on his own initiative relying on his memory of defamation cases.

The most telling indicator of the rise in the use of the criminal defamation laws is the number of cases that the public prosecution has referred to the Anti-Cybercrime and Intellectual Property Rights Bureau (Cybercrimes Bureau) for investigation, prior to being transferred to the courts. The Cybercrimes Bureau is a unit in the judicial police of the Internal Security Forces (ISF), which was established in 2006 to combat cybercrime and enhance online security in Lebanon.[88] Its mandate has included investigating defamation cases for speech published online. Lebanese lawyers and NGO specialists believe that the majority of defamation cases initiated against activists and journalists have been for critical speech published online.[89] The Cybercrimes Bureau does not initiate cases itself, but relies on the prosecution to refer cases to the bureau for investigation. The prosecution can initiate cases itself in the name of the public interest, or it can direct the Cybercrimes Bureau to take action based on a complaint filed by private individuals.[90]

Between January 2015 and May 2019, the Cybercrimes Bureau investigated 3,599 cases relating to defamation, libel, and slander. Of those, 185 were initiated based on complaints by public officials, 22 based on complaints by religious institutions, and 46 based on direct referrals from the public prosecutor in the name of the public interest.[91] The rest were initiated based on complaints by private citizens. [92]

The statistics reviewed by Human Rights Watch demonstrate the alarming increase in the number of defamation cases referred to the Cybercrimes Bureau for investigation. In 2015, the bureau investigated 341 such cases. The number increased to 755 the following year, and 800 the year after. In 2018, however, the bureau investigated 1,451 defamation cases – an increase of 81 percent from the previous year and 325 percent from 2015. The sharp increase in 2018 appears to be related to attempts to control critical speech ahead of the May parliamentary elections. In 2019, as of May 15, 252 defamation cases were referred to the Cybercrimes Bureau for investigation.[93]

Although experts believe that the Cybercrimes Bureau has handled the majority of the defamation cases, Human Rights Watch has documented investigations carried out by other security agencies pursuant to defamation charges, including the ISF’s Information Branch, the ISF’s Central Criminal Investigations Office, General Security’s Information Branch, State Security, and Military Intelligence.[94] Therefore, the statistics provided above are not exhaustive, and the number of individuals investigated and prosecuted for defamation is higher.

IV. Speech Criticizing the Authorities is Criminalized

In recent years Lebanon’s criminal defamation laws have been used against journalists, activists, and other citizens who have written about corruption by public officials, reported misconduct by security agencies, expressed their opinions and discontent with the current political and economic situation, and exposed abuse against vulnerable populations. Critical speech in these cases should be encouraged, not criminalized, as it is vital for a vibrant civil society and a functioning democracy.

Writing about Corruption and Misconduct by Public Officials

A large number of defamation cases investigated by Human Rights Watch resulted from speech related to writing or speaking about corruption and misconduct by public officials. Michel Kanbour, a Lebanese journalist and founder of the online newspaper Lebanon Debate, told Human Rights Watch he has been sued for defamation 30 times since 2012. He estimates that around 20 of those have been initiated since 2015.[95] Most of Kanbour’s defamation lawsuits have resulted from his reporting on corruption and misconduct by public officials.[96]

In one case, the Director General of a state institution filed a defamation lawsuit against Kanbour for writing an article accusing him of corruption on August 2, 2017.[97] In March 2018, the Publications Court sentenced Kanbour to six-months imprisonment and a fine of 10 million Lebanese liras (US$6,667) in absentia.[98] Kanbour claims that he was not informed of the lawsuit against him. He told Human Rights Watch that he found out about the case against him when some Lebanese media outlets contacted him for a comment on the day the sentence was issued.[99]

When Kanbour inquired with the court why he was not informed, the clerks told him that his wife had signed the court’s legal summons. Kanbour, however, said that the signature on the document was not his wife’s.[100] “The Publications law doesn’t respect international law because the trueness of the fact doesn’t matter … so any article that is courageous, you should expect a lawsuit,” Kanbour said. “In 2019, it is a disgrace that our judges issue rulings for imprisoning journalists. The only reason that can justify imprisoning a journalist is inciting violence. Supposedly insulting someone shouldn’t.” [101]

Other individuals have been called in for questioning and made to remove allegations of corruption, even before they had a chance to present their evidence. Ziad Zeidan, an activist from Beirut, was summoned for investigation at the Cybercrimes Bureau on Friday, February 1, 2019.[102] Two hours before he received a call from the bureau, Zeidan said he had posted a public live video on Facebook stating that in the evening, he will reveal evidence proving corrupt activities by the head of a municipality. The officer from the bureau told Zeidan that he needed to be at the bureau for an investigation within two hours, but declined to tell him the reason. Zeidan said that was impossible and called his lawyer, who was able to postpone the interrogation until Monday, February 4, 2019 on the condition that he would cancel the live video he had scheduled for that evening. The lawyer also found out from the Cybercrimes Bureau that the investigation was pursuant to a slander and libel lawsuit filed by the advisor of the municipal official.[103]

On Monday, Zeidan said he went to the Cybercrimes Bureau for an investigation that lasted from 9 a.m. until 9 p.m. During this period he was not allowed to have his lawyer with him. The Cybercrimes Bureau also called in two other individuals, Abdeulkarim Qumbrees and Chafiq Bader, for investigation, as they had “liked” his live video on Facebook, and according to Zeidan, an unknown individual had told the Bureau that they had assisted him in the research.[104] While Zeidan was being questioned, he said officers in the adjacent room looked through the contents of his phone and printed some conversations. At the end of the interrogation, according to Zeidan, the officers ordered him to remove the Facebook posts promoting and related to the video that was going to uncover the evidence pointing towards serious corruption in the municipality. They also instructed him and the two other men sign a pledge stating that they will not offend the official or his advisor in the future. Zeidan said that the officers did not threaten him, but after 12 hours of interrogation he felt that if he did not sign the pledge, he would not have been permitted to leave the bureau.[105]

Zeidan maintained that the intention behind the post was to draw attention to allegations of the squandering of public money. “This is our money,” he told Human Rights Watch. “The state should have watched it [the video] and taken action according to the allegations. Lebanon is dead, what can we say?”[106]

A businessman who is also the son-in-law of a prominent politician filed a criminal defamation lawsuit against journalist Hazem al-Amin following the publication of an article in Daraj, an independent pan-Arab news website, on June 20, 2018 raising questions about offshore companies and taxes, and raising questions as to the involvement of the politician in the scheme. Al-Amin is the co-founder and editor-in-chief of Daraj.[107]

A few days later, the businessman filed a defamation lawsuit against al-Amin. Although the businessman subsequently retracted the complaint, Internal Security Forces (ISF) officers raided Daraj’s office and detained al-Amin on December 10, 2018.[108] Al-Amin was released a few hours later, when the police officers confirmed that the lawsuit had indeed been retracted.[109] Under Lebanese law, when a private citizen retracts a defamation case, the state must also drop its case.[110]

Even questioning whether officials stand to personally gain from their official acts has led to lawsuits. Bechara al-Asmar, the former head of the General Confederation of Lebanese Workers, was sued in January 2019 by a then-minister for slander and libel resulting from statements he made during a talk show on Lebanese television. On the show al-Asmar asked a question that implied that the minister stood to personally profit from a decision made by his ministry.[111] Marcel Ghanem, the show’s host, asked whether al-Asmar was accusing the minister of corruption. Al-Asmar replied that he was just posing the question. A month later, on January 9, 2019, al-Asmar was called in for questioning by the Cybercrimes Bureau pursuant to a lawsuit filed against him by the minister. The minister told local media that al-Asmar was damaging his reputation.[112] Al-Asmar said he did not attend the questioning at the Cybercrimes bureau, and as of May 2019, his case was still ongoing in the Publications Court. Al-Asmar told Human Rights Watch:

I did not accuse him. I asked a question. I didn’t have information to base an accusation on. If I had committed an act of libel or slander, the judiciary is allowed to go after me. I, however, don’t practice slander or libel. I protect the rights of the Lebanese people, the rights of workers in Lebanon. I ask questions. I don’t target people’s dignity. When we protest in the streets against the government’s policies, are we targeting the prime minister? No, we’re criticizing the policies.[113]

Hani Nsouli, a Lebanese political commentator, criticized the unfairness in the judiciary’s pursuit of people who express themselves peacefully amid widespread impunity for corruption. “If someone commented on something, you treat him like a murderer. In a country like Lebanon, the people in power have bankrupted the country and destroyed the country and they didn’t go to prison. You then put someone in prison over a comment,” Nsouli said. “In any other country that respects itself those people [that bankrupted the country] would be in prison.”[114]

Reporting Misconduct by Security Agencies

One of the most infamous cases of criminal defamation in Lebanon is that of Hanin Ghaddar, a Lebanese journalist and researcher who was sentenced on January 10, 2018 by the Military Tribunal to six-months imprisonment, in absentia, for defaming the Lebanese Army under Article 157.[115] Ghaddar’s sentence arose from comments she made critical of the Lebanese army during a conference in Washington, DC in May 2015. During the question and answer section of her panel, Ghaddar alleged that the Lebanese army differentiates between Shia and Sunni terrorism, and that it has not sufficiently cracked down on the crimes of Shia militias, as the latter are protected by Hezbollah.[116] After outrage about Ghaddar’s verdict, on April 10, 2018, the Military Tribunal declared a lack of jurisdiction over this case and referred it to the Publications Court.[117]Ghaddar is not aware of the status of her case before the Publications Court.[118]

However, Ghaddar stated that the message was clear. “This free speech that we enjoyed for a while is over, and we are now back to the pre-2005 era. Only, instead of the Syrian army, we have the Lebanese state,” Ghaddar remarked. “Lebanon is good if you want to dance at night and not be involved in politics. Otherwise, it’s becoming hell.”[119]

In two other cases that sparked outrage among free speech activists in Lebanon, on March 7, 2019, the military judge in Mount Lebanon sentenced TV correspondent Adam Chamseddine and journalist Fidaa Itani in absentia to three months in prison for publishing comments offensive to State Security, one of Lebanon’s intelligence agencies, under Article 386 of the Penal Code.[120]

Chamseddine’s sentence arose from a public Facebook post he wrote on October 30 criticizing State Security for allegedly leaking details of an investigation of a detainee who had AIDS.[121] Fidaa Itani shared a social media post about the same case.

Both Chamseddine and Itani were sentenced in absentia. Chamseddine claimed that the court did not give him appropriate legal notice to appear for questioning or in court.[122] Chamseddine appealed the sentence, and Brigadier General Hussein Abdallah, head of the Military Court, referred his case back to the prosecution to transfer the case to the Publications Court.[123] Itani, however, is in self-imposed exile. He has not appealed the military court’s in absentia ruling.

The criminal court has also sentenced Itani to imprisonment and fined him in nine other cases filed against him by a minister on charges of insulting and defaming him. The accumulated prison time from these cases is 22-months imprisonment and 75 million Lebanese liras ($50,000).[124]

The first case against Itani arose from his Facebook post reacting to the Lebanese army’s operation in Arsal on June 30, 2017 against Syrian refugees, in which Itani alleged that a young girl was run over by a tank, hundreds were arrested, and some were arbitrarily killed.[125] Human Rights Watch documented violations during that raid which corroborate Itani’s allegations.[126] In the post, Itani used derogatory language implying that the state of the country was linked to the minister and the president.[127]

Itani was called in for interrogation to the Cybercrimes bureau, and he spent the night of July 10, 2017 in the bureau’s holding cell.[128] During his interrogation, officers from the bureau accused him of insulting the minister.[129] Itani told Human Rights Watch that the intention behind his post was to call out the Lebanese army for killing the people that it had a responsibility to protect. “These raids against refugees cannot go unnoticed. There needs to be accountability,” Itani said. “I don’t have a personal grievance against anyone … I only have moral, ethical, and political issues.”[130]

Itani was released on July 11, 2017, after which he said he received direct threats on social media. He left Lebanon to seek asylum in the United Kingdom on August 3, 2017.[131]

Itani’s case was referred to the Baabda Criminal Court, which sentenced him in absentia on June 27, 2018 to four-months imprisonment for publishing libelous statements against the president under Article 388 and two months for publishing libelous statements against the minister under Article 388, of which he would have to serve the longer sentence were he to return. The court also ordered that Itani pay 10 million Lebanese pounds ($6,667) as compensation to the minister.[132] “What was especially outrageous was that the judiciary took it upon themselves to add to my conviction “slandering the president,” even though that wasn’t in [the minister’s] lawsuit,” Itani told Human Rights Watch.[133]

All the eight subsequent criminal cases filed against Itani by the minister related to public Facebook posts Itani made using the same phrase to blame the minister for corruption and misconduct in the country.[134] In all of these cases, the criminal court sentenced Itani in absentia to two-months imprisonment for insulting the minister under Article 383 and fined under Articles 584 and 582 pertaining to slander and libel.[135] In all cases, the courts also awarded the minister compensation for the damages he sustained.[136]

General Security filed a defamation complaint against Makram Rabbah, a Lebanese academic, and Shadi Azzam, a Syrian activist, for comments that they made during a conference on June 15, 2019 organized by the research organization, UMAM Documentation and Research, about Syrian refugees in Lebanon.[137] Shadi Azzam told Human Rights Watch that the Central Criminal Investigations Office summoned him for questioning on August 22, 2019, where the officer accused him of insulting General Security and other prominent politicians in the country, including by disputing the figures released by General Security about Syrian refugee returns from Lebanon to Syria.[138] Azzam denied those allegations, insisting that the comments he had made were not meant to be insulting, but were based on information available in the public domain and on research conducted by credible research institutes.[139] After his interrogation, Azzam wrote on his Facebook page, “I am a human rights activist and I work for a peacebuilding organization whose main objectives are to strengthen the rule of law and human security … It is imperative that General Security and all stakeholders are working towards one cause, which is to preserve peace, prevent extremism, and fight terrorism, not to insult.”[140]

Expressing Political Opinions and Discontent

Criminal defamation charges have also been initiated against individuals who have expressed their political opinions or general discontent with the declining socioeconomic situation in the country, and in doing so, offended a public official or party member. A former aide of the prime minister, has filed criminal defamation charges against at least two individuals for their political opinions and analysis that he deemed to have insulted him or his reputation.

Hani Nsouli, a well-known political commentator, sent a voice note on WhatsApp in August 2018 to a private group of around 200 politically-active Beirut residents commenting on a photo of that individual that appeared in the news showing him in the company of individuals associated with an opposing political camp.[141] In the voice note, which Human Rights Watch reviewed, Nsouli expressed his surprise and displeasure and made comments about what he saw as the photo’s implications for the Sunni interests in Lebanon. Nsouli said that an official called him from the Central Criminal Investigations Office of the ISF on September 17, 2018 summoning him for investigation but declining to give him a reason. During Nsouli’s seven-hour interrogation on September 19, 2018, he said he was told that the individual had filed a lawsuit against him under Article 582 (slander), Article 317 (inciting sectarian tensions), and Articles 288 and 292 (disturbing Lebanon’s relations with a brotherly state).[142]

Nsouli rejected the charges. “This is a political opinion, not a personal insult. I’m talking politics,” he told Human Rights Watch. “And the charge that I’m inciting sectarian tensions is silly. On the contrary, I am criticizing those who are doing that.”[143]

At the end of his interrogation, Nsouli pledged that as long as that individual is not working in a public position, he will not take a political opinion towards him.[144] After signing the pledge Nsouli said he was under the impression that the case was closed, and so he was surprised when he received a summons to the criminal court in Beirut a month later for charges of slandering that person. The charges relating to inciting sectarian tensions and disturbing Lebanon’s relations with a brotherly state were dropped.

Nsouli was told by a close associate of the prime minister’s former aide that if he apologized publicly, the latter would withdraw the lawsuit. “I would prefer to go to prison rather than apologize,” Nsouli said. “Free speech is what distinguishes humans from animals.”[145]

The same former aide also sued Ahmad Ayoubi, a journalist and secretary general of the Civil Islamic Coalition, a moderate Islamic civil society group calling for better governance and the rule of law, for defamation. On November 12, 2017, Ayoubi wrote an article in an online publication about the political ramifications of a deal between that individual and a member of the opposing political camp. In the article, Ayoubi alleged that both parties stood to profit financially from such a deal.[146] In a separate public Facebook post in November, Ayoubi criticized the president and the foreign minister.[147]

A few days after the article’s publication, Ayoubi received a call from the Central Criminal Investigations Office summoning him for a defamation investigation but declining to tell him who had filed the charges. During his four-hour investigation on November 16, 2017, Ayoubi said he discovered that the former aide had filed charges under three articles: slander and libel, insulting a brotherly state, and insulting the president.[148] According to Ayoubi, the prosecutor dismissed the second and third charges.[149] The interrogator asked Ayoubi to pledge not to insult that individual, which he refused to do. “I will hold on to my political opinions, which are more important than personal insults,” Ayoubi said.[150]

Ayoubi said that when it became apparent that he was not going to sign the pledge, he was arrested and held in pretrial detention for 13 days in squalid conditions before being released on bail on November 28, 2017.[151] Responding to Ayoubi’s detention, General Ashraf Rifi, the former general director of the Internal Security Forces and former minister of justice tweeted: “the arrest of journalist Ahmad Ayoubi is an example of the practices of a security state that we will not accept to revive, and it is an attack on public freedoms and the media.”[152]

Ayoubi’s case was subsequently referred to the Publications Court. However, Ayoubi told Human Rights Watch on April 25, 2019 that the former aide’s lawyers have agreed to withdraw the case.[153]

In another such case, activist and journalist Mohammad Awwad was apprehended from his home on July 20, 2018 by an armed unit who Awwad said identified themselves as members of the General Security’s Information Branch after he published an article about “pack mentality” in Lebanon.[154] General Security is the agency responsible for the exit and entry of foreigners into the country, and are not usually involved in arrests or interrogations of citizens for speech-related crimes. In his article published on June 9, 2018 in Marsad News, Awwad explains his reasoning behind people’s willingness to die to for Hezbollah despite this sacrifice going against human nature.[155] During his interrogation, officers from General Security searched Awwad’s laptop and phone and inquired about his political views and opposition to Hezbollah and Amal.[156] An officer then asked him to sign a pledge not to insult sectarian leaders and incite sectarian tension, or else he would have to spend the weekend at General Security. “I told them that I will sign this paper because it has no legal bearing,” Awwad told Human Rights Watch.[157] Awwad was released around five hours after his arrest.[158]

Awwad thinks that he was apprehended in this aggressive way not due to the article he wrote, but due to his anti-Hezbollah political opinions and other writings.[159] Remarking about his experience, Awwad said “these things only happen in movies.”[160]

Public displays of anger and discontent have also resulted in arrest. Eighty-year-old Daoud Moukheiber was arrested a day after a video of him protesting the government’s decision to install high-voltage power lines through his town proliferated on social media.[161] The town’s residents had been protesting the government’s installation of the power lines for weeks, which they fear pose significant health risks, and the government, at times, has responded with force.[162]

During a protest on May 7, 2019, Moukheiber was captured on video expressing his discontent using strong language against the president and two ministers, who are all members of the same political party. Many felt that Moukheiber’s outburst captured the public’s anger and disillusionment with the government’s encroachment on their basic rights, so the video spread rapidly.[163] The next day, videos shared on public social media platforms show Moukheiber being handcuffed and arrested by security forces.[164] Samer Saade, a Lebanese political activist, tweeted: “Daoud Moukheiber to the prison of freedom, in the state of the muzzling of mouths. How strong you [government officials] are to fear the criticism of the free and the oppressed.”[165]

Exposing Abuse against Vulnerable Populations

Exposing abuse against vulnerable populations has also led to criminal defamation charges. In one case that garnered significant local and international attention, several newspapers, as well as Human Rights Watch, were instructed by a prosecutor to take down their reporting on the alleged abuse of a migrant domestic worker in Lebanon pursuant to a defamation case filed by the worker’s employers.

Human Rights Watch and Lebanese human rights organizations routinely document credible reports of abuses against migrant domestic workers in Lebanon, including nonpayment of wages, forced confinement, refusal to provide time off, and verbal and physical abuse.[166] In 2008, Human Rights Watch found that migrant domestic workers were dying at a rate of one per week, with suicide and attempted escapes the leading causes of death.[167] Human Rights Watch has also found that Lebanon’s judiciary fails to hold employers accountable for abuses and that security agencies often did not adequately investigate claims of violence or abuse.[168]

In a video posted to social media on March 26, 2018 by the organization This is Lebanon, Lensa Lelisa, an Ethiopian national, detailed specific allegations of consistent abuse at the hands of her employer which led her to jump from a balcony and injure herself in an effort to escape.[169] Lelisa returned to the home after a few days, and recanted, saying she fell off the balcony and made up the story because she wanted to leave Lebanon.[170] Human Rights Watch reported on the incident in April 6, 2018, urging Lebanon’s general prosecutor to ensure an adequate investigation into Lelisa’s allegations of abuse and protect her from any possible retaliation.[171]

On June 18, 2018, Human Rights Watch received a letter from the Acting Head of the Cybercrimes Bureau, Captain Information Engineer Ayman Taj al-Din, instructing that the press release on Lelisa’s case be removed as per the instructions of the Attorney General of the Appeals Court in Mount Lebanon, Justice Rami Abdullah. This order was pursuant to a defamation lawsuit filed by Lelisa’s employers against This is Lebanon.[172]

Four Lebanese lawyers advised Human Rights Watch that the instruction cannot be appealed because it is a prosecutor’s instruction and not a court order. The letter Human Rights Watch received from the Cybercrimes Bureau did not include the legal basis for the instruction or the text of the instruction itself. This was the first time a security agency or prosecutor has instructed Human Rights Watch in Lebanon to take down any content.

On June 27, 2018 Human Rights Watch wrote to the prosecutor who issued the instruction and to the Cybercrimes Bureau asking for a copy of the instruction and its legal basis. In its letter, Human Rights Watch asked the prosecutor to reconsider the instruction because it may violate Lebanon’s human rights obligations under international law, disproportionately restrict Human Rights Watch’s ability to freely and accurately report on human rights in Lebanon, and violate the right of the people of Lebanon to freely access information. In response, the prosecutor told Human Rights Watch’s legal counsel in Lebanon on July 2, 2018 that it did not need to remove the press release, since Human Rights Watch had already removed a now-dead link to the video posted by This is Lebanon.

Other publications in Lebanon have received similar takedown instructions from the prosecutor, including L’Orient le Jour[173] and The Legal Agenda.[174] Some publications have not complied with the instruction, while others, such as The Daily Star and the Lebanese Broadcasting Company (LBC), have taken down stories covering the allegations.

Journalist Anne-Marie el-Hage, who covered Lelisa’s allegations for L’Orient le Jour, said that the Cybercrimes Bureau called the newspaper on June 8, 2018 and asked the editor-in-chief to remove El Hage’s article as per an order from the prosecutor and summoned El Hage for investigation. El Hage’s lawyer advised her not to attend the investigation due to a “gentleman’s agreement” between the Order of Journalists and the Public Prosecutor’s office stating that journalists should not be interrogated by security agencies, but by investigative judges.[175] El Hage also told Human Rights Watch that there was an editorial decision at L’Orient le Jour not to take down the article in order to avoid setting a precedent by giving in to an injunction without a court order.[176] “I am not insulting anybody,” El Hage insisted. “I am working for human rights.”[177]

The English-language newspaper, The Daily Star, however, decided to remove its article reporting on Lelisa’s allegations of abuse after Timour Azhari, the reporter who wrote the story, was interrogated by officials at the Cybercrimes bureau for eight hours on June 7, 2018. Azhari told Human Rights Watch that the interrogator accused him of actively working to defame Lelisa’s employers and considered any evidence presented by This is Lebanon as unreliable, as the organization was “defaming the entire country.”[178]

During his interrogation, Azhari said an officer verbally threatened him, confiscated his phone, and read its contents. Azhari said the interrogator obtained the name and contact details of his anonymous source and instructed him to take down a Tweet linking to the article and another showing a video of a protest that took place outside the employer’s shop, referencing a judge’s order.[179] It is likely that the interrogator was referring to the prosecutor’s injunction, which was received by L’Orient le Jour since there was no court order. The interrogators asked Azhari to sign a pledge that he would not comment on Lelisa’s case anymore, to which he agreed.[180] Despite doing so, his case was still ongoing in the criminal courts as of July 2019.

Azhari said that as a Lebanon reporter for The Daily Star, it is his job to cover all stories, but especially ones that have a wider social impact, and he continues to report on allegations of abuse against migrant domestic workers:

When I saw the video of Lensa alleging abuse from her hospital bed, it really struck me. Often, migrant domestic workers die after jumping off buildings or are able to escape and so don’t publicize their ordeal. It is very rare to have that kind of thing recorded. The courage that it took to do that, I just had to report on it. This video showed that the abuse was happening to the most powerless people in Lebanon who are employed under a system that strips them of the rights that we all enjoy. I saw an opportunity to contribute to the conversation about the way that hundreds of thousands of people are treated in Lebanon.[181]

V. Violations and Bias in the Enforcement of Criminal Defamation Laws

As the preceding chapter demonstrated, defamation laws in Lebanon criminalize peaceful speech that is vital for the proper functioning of a democratic society. In addition, in the cases that Human Rights Watch investigated, the authorities behaved in ways that suggested bias and ulterior motives. The laws were applied selectively, investigating agencies failed to follow standard procedures and violated legal safeguards, and the judiciary failed to apply international human rights standards on freedom of expression. These examples illustrate the potential for misuse of criminal defamation law as a tool for retaliation and repression rather than as a mechanism for redress where genuine injury has occurred.

Selective Investigations and Arrests

Human Rights Watch’s research suggests that prosecutors are applying Lebanon’s criminal defamation laws selectively in ways that further the interests of powerful political and religious actors. Prosecutors and security agencies often do not follow a standard process in criminal defamation cases, further exacerbating the law’s selective application and giving public officials increased discretion in the way these cases are handled.

The selective nature of the prosecution was evident in the case of popular indie band, Mashrou’ Leila, that has gained worldwide acclaim for tackling pressing social issues in the Arab world and speaking out against oppression, corruption, and homophobia. The band was slated to perform at a music festival in Lebanon on August 9, 2019. On July 22, a lawyer affiliated with religious groups filed a complaint with the public prosecution accusing Mashrou’ Leila of insulting religious rituals and inciting sectarian tensions through their social media posts and song lyrics. This prompted powerful religious groups to call for the concert’s cancellation, and many Internet users threatened the band with violence if the concert went ahead.[182]