Summary

Joshua F. left his home in Cameroon with his younger sister in 2016, when he was 13, after their parents died in an accident. His father’s family took the house and his father’s workshop, turning the two children out. They left Douala and travelled to Yaoundé, where they lived on the streets for a time until a man offered Joshua a carpentry job in northern Cameroon. In fact, the man took them to Chad and forced them to work long hours without pay in his home.

Joshua and his sister were then abducted and taken to Libya. There, he told Human Rights Watch, they were held by smugglers. “I was the victim of slavery,” he said, describing long days of forced labour in fields and on construction sites. The men who held him and his sister beat them and demanded that they contact their family to arrange a ransom payment. After he repeatedly told the men they had nobody they could call, one of the men killed his sister in front of him.

After he had been in Libya for about a year, once he had worked long enough that the men considered his ransom paid, they took him to the beach to join a large group boarding a Zodiac, a large inflatable boat. The men forced as many as possible onto the boat, at one point firing guns at the water near the group. After several days at sea, a ship rescued the group and took them to Italy.

Joshua had sustained injuries from the forced labour and beatings he endured in Libya, and when he arrived in Italy, he asked reception center staff to see a doctor. But he never received medical care while he was in Italy. He was also not able to attend school.

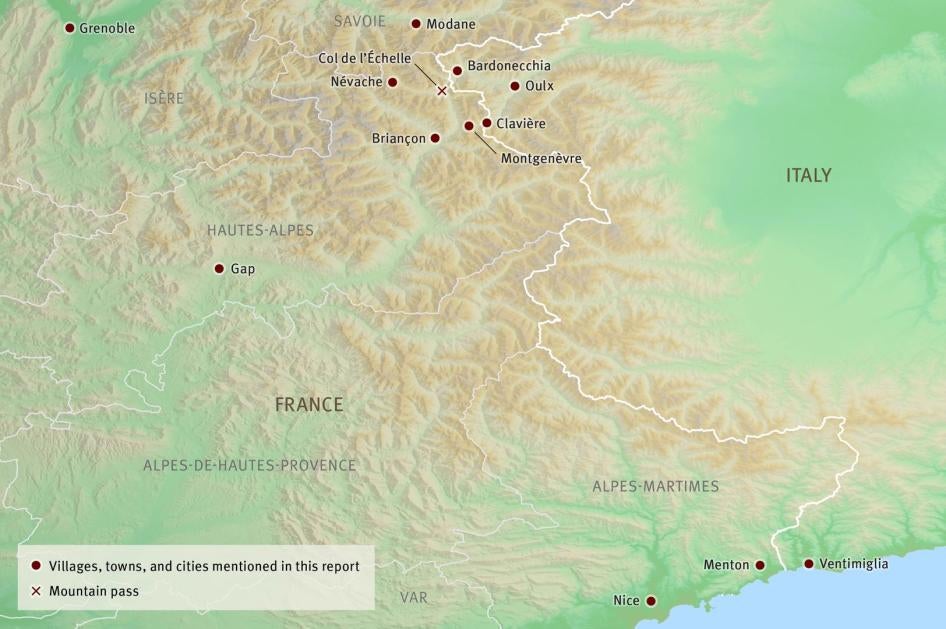

After six months, he decided to leave Italy. He travelled to Claviere, a village in the Alps on the French-Italian border, and tried to enter France on five successive nights. On his first four attempts, border police sent him back to Italy after he told them his age and tried to explain his situation, even though by law they should have accepted his declared age and, under the procedures the border police director described to Human Rights Watch, should have referred him to child protection authorities.

On his fifth attempt, police let him continue into France. They did not contact child welfare services; instead, he and another boy walked all night to reach the town of Briançon. Volunteers at a shelter there gave him first aid and arranged for his transport to the departmental capital, Gap, where unaccompanied children undergo age assessments to determine whether they will be taken into care.

In Gap, he received a negative age assessment for reasons he still does not understand. “There were things written there I did not say,” he told us. With the aid of lawyers, he asked the juvenile judge to review the negative age assessment and was expecting a ruling in mid-September 2019.

Like Joshua, many children decide to leave Italy and travel to France because they have not received access to education or adequate health care in Italy. The perception of hostility on the part of the Italian government and the general public is also a significant factor in unaccompanied children’s decisions to leave Italy.

Unaccompanied migrant children who travel from Italy to France’s Hautes-Alpes Department may, in violation of French law and child rights protection norms, be summarily returned to Italy by French authorities. To avoid apprehension and summary return by border police, many children cross the border at night, hiking high into the mountains far off established trails.

Even in the height of the summer, in July and August, it is cold in the mountains, and it is easy to get lost in the dark. Children described walking seven to ten hours to reach Briançon, less than 15 km via the most direct route by road. Many were exhausted by the time they reached Briançon, and some had suffered injuries from falls on rocky slopes or while crossing frigid mountain streams. In the winter months, the crossing can be perilous: many of the children interviewed by Human Rights Watch in January and February were recovering from frostbite, and some required hospitalization.

Once they enter France, many are refused formal recognition as children after flawed age assessments. In cases reviewed by Human Rights Watch, many children received negative age assessments because, in the judgement of the examiner, they failed to provide clear accounts of their journeys—in reality, meaning that they made minor mistakes with dates, confused the names of places they travelled through, or did not want to discuss particularly difficult experiences with an adult they had just met. Work in home countries or while in transit to Europe may be taken as an indication that the child is older than claimed, even though many children work at very young ages around the world. Life goals that examiners deem unrealistic, such as overly optimistic assessments of career prospects, may also be factors in negative age assessments.

French regulations require these evaluations to be multidisciplinary in nature, meaning that they should consider children’s educational background, psychological factors, and other aspects of their lives, and call for them to be conducted in a manner “characterized by neutrality and compassion.” In fact, some children described questioning by examiners they said were indifferent or hostile. Children did not always understand the interpreters assigned to them, and some said that their interpreters criticized their responses. Many children felt they had not been heard during their interviews, a conclusion reinforced when they saw the reports prepared by the examiner. Echoing Joshua’s remarks, many other children told us the reports contained significant inaccuracies and included statements they had not made.

Many of the children who arrive on their own in France, whether in the Hautes-Alpes or elsewhere, have suffered serious abuses in their home countries, endured torture, forced labour, and other ill-treatment in Libya, and undergone terrifying sea crossings on overcrowded boats on their way to Europe. Many show symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, doctors who work with migrant children in the Hautes-Alpes told Human Rights Watch. But the age examination process does not appear to take into account these circumstances and the well-documented effects of PTSD on memory, concentration, and the expression of emotion.

An immediate consequence of a negative age assessment is eviction from the emergency shelter for unaccompanied children, even for individuals who seek review before a judge. Some find shelter with families who volunteer space in their homes. Others are housed in shelters for adults.

Some children ultimately succeed in having negative age assessments overturned on review, but delays in formal recognition as a child may affect their eligibility for regular immigration status upon adulthood.

Police have also harassed aid workers, volunteers, and activists who take part in search-and-rescue operations in the mountains. For example, members of these search-and-rescue teams told Human Rights Watch police regularly subject them to document checks—procedures that are lawful in France but open to abuse. In some cases, volunteers and activists describe receiving traffic infractions or being subjected to intrusive searches or protracted questioning in circumstances that suggest that the purpose of these acts by police was to target them for their lawful humanitarian activities rather than to ensure road safety or establish identity. Humanitarian assistance is protected under French law, and the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) has called for EU guidance to clarify that humanitarian assistance to migrants should not be a crime. Nevertheless, French authorities have brought criminal charges against aid workers, often under provisions that criminalize the facilitation of irregular entry.

The practices identified in this report violate unaccompanied children’s human rights, as well as the human rights of aid workers, volunteers, and activists who assist migrant children and adults.

Case of police pushbacks of unaccompanied children to Italy reviewed by Human Rights Watch appear to be a matter of individual police officer’s whim and do not comply with French law or international human rights norms on treatment of unaccompanied children and deny them the protection and care in France they are entitled to as children.

Age assessment procedures in the Hautes-Alpes are arbitrary and fail to respect children’s right to a fair process, drawing adverse inferences from factors such as travelling alone or working while in transit, minor errors with dates, and reluctance to discuss traumatic events in detail. In addition, because formal recognition as a child is an essential first step to enter the child protection system and receive other rights and services, including access to housing, health, and education and regularization of legal status, the age assessment procedures employed in the Hautes-Alpes lead to denial of children’s right to protection and assistance.

France shares the same obligations as all other EU member states to afford unaccompanied children who arrive at its borders special safeguards that protect their human rights as set out in international and EU law. This report evaluates French authorities’ actions in relation to those obligations, while recognizing that France is not alone in the European Union in failing to meet them consistently. The fact that unaccompanied children arriving in France may have had their rights violated by authorities in another EU country does not mitigate France’s duty to ensure that its policies and practices with respect to unaccompanied migrant children comply with international and regional norms and EU law.

Police harassment of aid workers, volunteers, and activists interferes with their ability to provide potentially life-saving assistance to children and adults in need. Prosecutions for providing humanitarian assistance potentially violate a range of rights, including that of freedom of association.

To address the shortcomings identified in this report, French police and immigration authorities should end summary returns of unaccompanied migrant children to Italy and instead ensure they are immediately transferred to the child welfare system for appropriate protection and care.

French authorities should reform age assessment procedures in line with international standards to ensure that children are not arbitrarily denied formal recognition and the protection to which they are entitled.

Authorities should also prevent and ensure accountability for police harassment of humanitarian workers.

Recommendations

To the Ministry of the Interior and the Ministry of Justice

- Investigate accounts of police pushbacks of unaccompanied children at the French-Italian border and reported intimidation of volunteers and activists.

- Repeal the decree allowing prefectures to process the personal data of those who receive negative age assessments for the purpose of expulsion from French territory, potentially before they have had the opportunity to seek review.

- Ensure that aid and assistance to migrants are not criminalized, in line with the July 2018 decision of the Constitutional Council (Conseil constitutionnel).

- Together with the Ministry of Social Affairs, ensure that departments have sufficient resources to carry out their child protection functions.

To the Ministry of Social Affairs (Ministère des solidarités et de la santé)

- Prepare guidance on how to conduct multidisciplinary age assessments that afford the benefit of the doubt in cases where there is a reasonable possibility that the person assessed may be a child and disseminate that guidance to departmental child protection authorities.

- Together with the Ministry of the Interior and the Ministry of Justice, ensure that departments have sufficient resources to carry out their child protection functions.

To the Hautes-Alpes Prefecture and the French Border Police (Police aux frontières)

- Direct border police to accept an individual’s declared age if there is a reasonable possibility that the person is a child. In such cases, border police should transfer those individuals to the care of child protection authorities. In no case should an individual be returned to Italy if there is a reasonable possibility that the person is a child.

- Ensure that all individuals refused entry into France, including those who are apprehended after irregular entry, are notified of their rights in a language they understand, as required by article L.213-2 of the Code on Reception and Residency of Foreigners and Asylum Law (Code de l’entrée et du séjour des étrangers et du droit d’asile).

- Verification of birth certificates and other identity documents obtained abroad should, consistent with article 47 of the Civil Code, be presumed valid in the absence of substantiated reason to believe they are not.

- Instruct police officers to refrain from conducting abusive identity checks targeting humanitarian activists and volunteers, and to ensure that all stops are grounded in a reasonable suspicion of wrongdoing.

- Investigate and, if appropriate, sanction conduct by the border police that does not comply with the Code on Reception and Residency of Foreigners and Asylum Law and with policing standards.

To the Hautes-Alpes Directorate of Prevention Policy and Social Action (Direction des Politiques de Prévention et de l’Action Sociale)

- Ensure that all those who are awaiting an evaluation receive emergency shelter for the minimum period of five days or until the evaluation is completed, as required by article R.221-11 of the Code on Social Action and Families (Code de l’action sociale et des familles). The period of emergency shelter should be extended to cover any period of appeal of an adverse age determination.

- Issue and implement clear guidance to staff that age assessments should follow the November 17, 2016, order of the Ministry of Justice. All interviews should be conducted with particular expertise and care, in a manner “characterized by neutrality and compassion.” Birth certificates and other civil documents obtained abroad should be presumed valid in the absence of substantiated reason to believe they are not.

- Provide for screening for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) by trained psychiatrists prior to age assessment evaluations. Those found to have symptoms that could indicate PTSD should receive counseling prior to assessment. In addition, specific protocols should be developed with input from experts in PTSD to determine when, how, and by whom children with PTSD should be assessed.

- Ensure the availability of interpreters who speak the languages and their variants most commonly spoken by unaccompanied children who undergo age assessments in the Hautes-Alpes.

To the juvenile court (Tribunal des Enfants)

- Juvenile court judges should apply the presumption of validity of birth registration and other identity documents issued abroad, in line with article 47 of the Civil Code.

- Juvenile court judges should exercise their responsibility to ensure effective review of departmental age assessments.

To the public prosecutor (procureur)

- Appoint a legal representative (administrateur ad hoc) without delay whenever a person claiming to be an unaccompanied child seeks to submit an asylum claim to the French Office for the Protection of Refugees and Stateless Persons (Office français de protection des réfugies et apatrides, OFPRA).

To the Government and the Parliament

- Abolish the arbitrary legal status of the 10 km border zone; admit unaccompanied children arriving at the border to French territory to allow their protection needs, vulnerabilities, views, and best interests to be properly assessed and to inform any decision about their future.

- Amend article 622-1 of the Code on Reception and Residency of Foreigners and Asylum Law to clarify that humanitarian assistance, including the provision of food, water, clothing, medical care, and transport is not a criminal offence, in line with the Constitutional Council’s July 2018 ruling that fraternity (fraternité) is a constitutionally protected principle.

- Amend the Code on Social Action and Families and other legislation, as appropriate, to reflect the following, in line with international standards:

- Any age assessment should be a matter of last resort, to be used only where there are serious doubts about an individual’s declared age and where other approaches, including efforts to gather documentary evidence, have failed to establish an individual’s age.

- Authorities should offer clear reasons in writing as to why an individual’s age is doubted before beginning an age assessment.

- The environment, questions asked, and assessment of responses should take into account the reality that children cannot be expected to provide the same level of precision as might be expected of an adult, and also reflect the fact that the trauma many children have experienced can affect memory and demeanor.

- Authorities should not draw adverse inferences from work undertaken by children, the fact that some children have spent time on the streets, decisions by children to travel to Europe on their own. Such experiences are unfortunately common around the world and should not be taken as calling into question a child’s declared age.

- Age assessment should afford the benefit of the doubt such that if there is a possibility that an individual is a child, he or she is treated as such.

- Amend the Code on Social Action and Families and other legislation, as appropriate, to ensure that the finding of one department (an administrative division of France) that an individual is under the age of 18 cannot be challenged by another department.

- Amend articles L.313-11 and L.313-15 of the Code on Reception and Residency of Foreigners and Asylum Law and article 21-12 of the Civil Code to ensure that children are not penalized by delays in the age assessment process. For the purpose of eligibility for residence permits and nationality upon reaching adulthood, children should be regarded as having been taken into care by the child welfare system (Service de l’aide sociale à l’enfance, ASE) as of the day they sought to be recognized as children at the Hautes-Alpes Directorate of Prevention Policy and Social Action or at similar evaluation centers, regardless of how long the age assessment process takes.

To the Italian Ministry of the Interior’s Department for Civil Liberties and Immigration (Dipartimento per la Libertà civili e l’Immigrazione)

- Ensure that all Italian reception centers, including those for unaccompanied migrant children, provide children with access to education, health care, and psychosocial support and identify durable solutions on an individual basis for each unaccompanied child to help establish normality and long-term stability, in line with the European Commission’s 2017 communication on the protection of children in migration and the European Asylum Support Office’s 2018 guidance on reception conditions for unaccompanied children.

To the European Commission

- Assess whether France and Italy are in breach of the Asylum Procedures Directive, the Reception Directive, and the Dublin III Regulation. In particular, the European Commission should examine whether France’s age assessment methods adequately afford the benefit of the doubt where results are inconclusive and should evaluate reception conditions and safeguards for children in Italy. The Commission should do the same evaluation where concerns arise at other EU internal borders.

- Propose revision of the Facilitation Directive to require sanctions for the smuggling of persons only “when committed intentionally and in order to obtain, directly or indirectly, a financial or other material benefit,” as provided in the UN Smuggling Protocol. The revised Facilitation Directive should explicitly provide that EU Member States should not impose sanctions for the facilitation of irregular entry or transit in cases where the aim is to provide humanitarian assistance.

- Until the Facilitation Directive is revised, develop guidance to ensure its implementation complies with international standards, in particular to clarify that the provision of humanitarian assistance without financial or other material benefit should not be a criminal offense.

Methodology

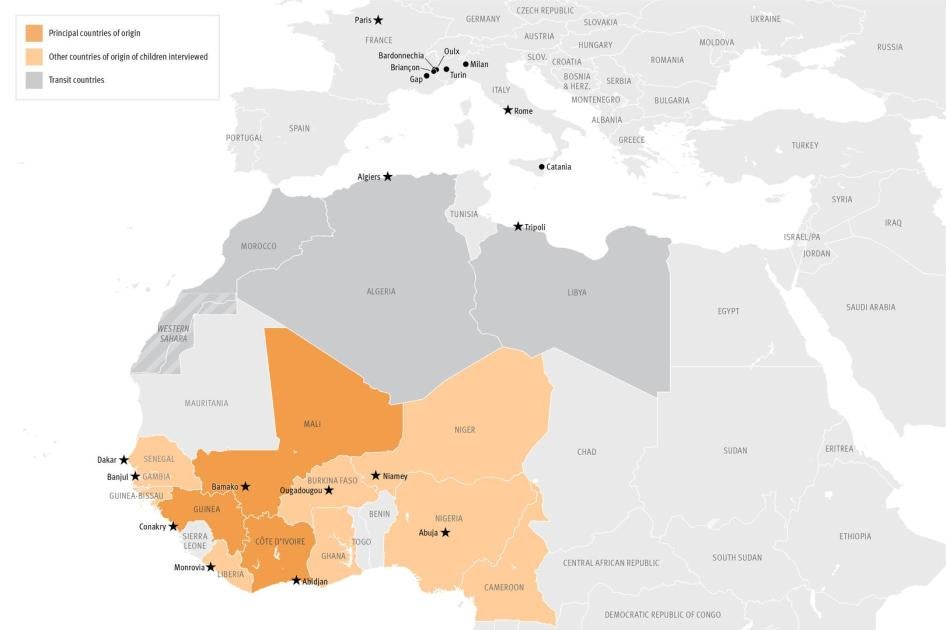

This report is based on research in the French Department of Hautes-Alpes between January and July 2019. Three Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed fifty-nine boys, one girl, and one adult man who had recently turned 18. Sixty identified themselves as children under the age of 18, and one was an 18-year-old who arrived in France at the age of 16. Twenty-one were from the Republic of Guinea (often referred to as Guinea-Conakry to distinguish it from Guinea-Bissau and Equatorial Guinea), ten from Côte d’Ivoire, nine from Mali, six from Gambia, four from Nigeria, three from Senegal, two from Burkina Faso, and one each from Benin, Cameroon, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, and Niger. Fifty-eight travelled through Libya and Italy before arriving in France. Two travelled through Morocco and Spain, and one flew directly to France.

Two of those we interviewed were formally recognized as children following an age assessment by the Departmental Council; 33 had received negative age assessments from the Departmental Council by the time of our interview. Seven of those who received negative age assessments eventually received formal recognition as children after a juvenile court judge (juge des enfants) reviewed their cases, and one was recognized as a child by a family court judge (juge des tutelles). The 18-year-old man had received a French residence permit (carte de séjour) 11 months after he was formally recognized as a child by the juvenile court judge and the week before Human Rights Watch interviewed him.

Human Rights Watch researchers conducted interviews in French, English, Italian, or in one case in Portuguese, depending on the preference of the person being interviewed. The researchers explained to all interviewees the nature and purpose of our research, including our intent to publish a report with the information gathered. They informed each potential interviewee that they were under no obligation to speak with us, that Human Rights Watch does not provide humanitarian services or legal assistance, and that they could stop the interview at any time or decline to answer specific questions with no adverse consequences. The researchers obtained oral consent for each interview. Interviewees did not receive material compensation for speaking with Human Rights Watch.

In addition, Human Rights Watch reviewed 36 evaluations conducted by the Directorate of Prevention Policy and Social Action (Direction des Politiques de Prévention et de l’Action Sociale) of the Department of Hautes-Alpes, 13 juvenile court judgments, and 2 guardianship orders from the family court.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed lawyers, health care providers, staff of humanitarian agencies, volunteers who assist migrant children, and volunteers and activists who conduct search-and-rescue missions in the mountains near the French-Italian border.

Human Rights Watch met with and shared the findings of this research with the Hautes-Alpes prefecture and the border police director for the Hautes-Alpes and Alpes de Haute-Provence. We made three requests for a meeting with the Hautes-Alpes Directorate of Prevention Policy and Social Action and two additional requests for responses to our preliminary findings.[1] In response to our first request for a meeting asking to hear from the department how it identifies children, provides them with accommodation, and ensures their education, the department replied:

We take care of our responsibilities to shelter, evaluate with reference to the legal instruments, follow the cases of recognized minors, with regard to the schooling, apprenticeships, or internships with businesses . . .

In our opinion, there is nothing to be “heard” [from us], the migratory flow has declined in the Hautes-Alpes and our activities have not stopped.[2]

The department eventually offered general responses to several of the points we raised but refused to answer our specific questions.[3]

Human Rights Watch also provided Italian authorities with a summary of children’s accounts of reception conditions in Italy and requested their response to these accounts.[4] In reply, Italian authorities described the reception system for unaccompanied children and offered some responses to the questions we posed, as discussed more fully in the next chapter.[5] .

All names of children used in this report are pseudonyms. Human Rights Watch has also withheld the names and other identifying information of humanitarian workers who requested that we not publish this information.

In line with international standards, the term “child” refers to a person under the age of 18.[6] As the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child and other international authorities do, we use the term “unaccompanied children” in this report to refer to children “who have been separated from both parents and other relatives and are not being cared for by an adult who, by law or custom, is responsible for doing so.”[7] “Separated children” are those who are “separated from both parents, or from their previous legal or customary primary care-giver, but not necessarily from other relatives,”[8] meaning that they may be accompanied by other adult relatives.

I. Unaccompanied Children Arriving in the Hautes-Alpes

As with Joshua F., whose case is described at the beginning of this report, many unaccompanied children told Human Rights Watch they came to the Hautes-Alpes after leaving their home countries on their own, with siblings or friends of their own age, or in the company of adults to escape harm at the hands of abusive families, targeted violence from criminal groups, and armed groups.

Nearly all described dangers they faced on their journey, notably the 58 who told us they transited through Libya, where arbitrary detention by authorities, militias, smugglers, and traffickers, torture and other ill-treatment, and forced labor of migrant adults and children are commonly reported. Some said they saw friends or family killed in their home countries, and one boy told us smugglers killed his sister when they were in Libya. Others watched people drown in the Mediterranean when their boats tossed or capsized on heavy seas. The risks on the journey, particularly in Libya and on the Mediterranean crossing, are severe enough that the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the International Organization for Migration (IOM) describe the Central Mediterranean route as “singularly dangerous,” one of the world’s riskiest migration routes.[9]

Most of the children interviewed for this report spent six months to a year or more in Italy before deciding to make their way to France. Many cited the lack of access to education and health care as the primary reasons for their decisions to leave Italy. Some children said that discriminatory attitudes expressed by government officials and members of the general public factored into their decisions to leave Italy and travel to France. In addition, children from French-speaking countries frequently said that language and a sense of historic ties between their home countries and France were additional motivations to leave Italy for France.

Most children told Human Rights Watch they attempted to cross the border between Italy and France by traversing the mountains near Claviere, on the Italian side, and Montgenèvre, in France. They crossed through the mountains to avoid apprehension and summary return to Italy, and they chose this route because they heard that it was less dangerous than other mountain routes.

It is true that the route between Claviere and Montgenèvre is comparatively safer than other routes through the Alps, but unpredictable weather, the distance involved, and the need to navigate unfamiliar, steep mountain terrain at night create significant risks. Temperatures can plummet at night, and paths can be covered in snow until early June. Youths told us that to avoid apprehension, they went as high as possible, hiding whenever they saw lights in the distance or heard snowmobiles. Siaka A., a 16-year-old Ivoirian boy, told us that he and the others he was travelling with jumped into snowbanks whenever they saw or heard people.[10] Louis M., a 16-year-old boy from Mali, said, “There was a lot of snow. It was up to my knees. We had to stop every so often because of the snow.”[11] As a result, many children arrive in Briançon suffering from frostbite, other injuries, and the effects of exhaustion.

In 2018, one-third of the migrants staying in the shelter in Briançon identified themselves as children, shelter volunteers told us.[12] Most are West African; the most common countries of origin are Guinea, Côte d’Ivoire, and Mali.[13]

Reasons for Leaving Their Homes

The children we interviewed described leaving their homes and travelling on their own for a variety of reasons. Many of the children Human Rights Watch spoke with said they had fled abusive family situations, particularly at the hands of stepparents or extended family members after the death of a parent. Others said they had been subjected to labor exploitation. Some said they were targeted by armed groups or by members of the community because of their or their families’ religion, perceived political views, or for other reasons. And some described circumstances that suggested they were trafficked.

Many of the experiences children described are potential grounds for asylum or other protection from return under international law.[14] French law affords unaccompanied children immediate protection and the possibility of regular immigration status upon adulthood for those who are formally recognized as children and placed under the care of the child welfare system, without requiring them to go through the separate asylum process. For this reason, most unaccompanied children in France do not seek asylum, although they are not precluded from doing so.[15]

Abusive Families

Children frequently mentioned family abuse and neglect as the principal reason why they left their home countries.

In particular, children who moved to a relative’s house after the death of a parent said that they faced physical abuse from their new caregivers, typically extended family members. For example, Kebba S., a 16-year-old boy with a Gambian father and Senegalese mother said, “When my father died, I left with my mom for Senegal, to stay with my uncle. My uncle wasn’t gentle with me. Another uncle, who loves me a lot and who is in Gabon, helped me leave.”[16] Other boys, including Malick I., described physical abuse from extended family in similar circumstances.[17]

In addition to physical abuse, some children described situations of labour exploitation in their new homes, as with Louis M., a 16-year-old from Mali, who told us that his uncle forced him to work in the fields after his father and mother died. The work was very difficult, he said, adding, “I was in a very, very bad state.”[18] Ramatoulaye M., a 16-year-old from Côte d’Ivoire, said that his relatives sent him to work on the streets of Abidjan after his parents separated and remarried.[19]

Others, such as 16-year-old Yatma K., from Guinea, said that their new caregivers did not allow them to attend school.[20]

Several children told us they were simply unwelcome after the remarriage or death of a parent. Samuel A., a 16-year-old from Nigeria, said, “My stepmother did not want me around. My father told me it was time for me to take care of myself.”[21] Boubacar Y., a 15-year-old from Guinea, gave a similar account.[22] And a 16-year-old Guinean boy, Ismael K., told us that after his father died, his father’s second wife did not want him in the house.[23]

Other children described violence at the hands of one parent after a divorce or separation.[24]

Some children said that their religion or a parent’s religion was a source of tension in their family. Malik R., a 16-year-old from Senegal, explained that his mother is Christian and his father Muslim. “When I was 12, I chose my mother’s religion. My father hasn’t accepted that.”[25] Fabrice M., a 17-year-old Guinean boy, told us that he was raised Catholic, his mother’s religion; after his father died, his father’s family pressured him to convert to Islam, beating him and at one point burning him with an iron rod when he refused.[26] Sixteen-year-old Joshua F., from Cameroon, whose father was Muslim and mother Christian, said that after his parents died in an accident, “My father’s side, they did not like me. . . . They sold my father’s house and carpentry shop where I worked. I was on the street with my little sister.”[27]

In Joshua’s case, although he attributed his relatives’ actions to disagreement over religion, they may have been motivated simply by the desire to take his father’s property. Other children mentioned that their relatives wanted property that a deceased parent had owned. For example, Ousmane A., a 17-year-old, left Guinea with his brother after his half-brothers assaulted him and broke his kneecap during an inheritance dispute.[28] Adama M., a 17-year-old from Côte d’Ivoire, said that after his father died, his uncles turned him and his mother out of their house in Abidjan.[29]

Others left because they had no family to care for them, such as Abdullah S., a Liberian 16-year-old.[30] Another 16-year-old, Louis M., from Mali, said, “My father and mother are dead; there is no life for me there.”[31] Assane B., a 15-year-old, said that he had been living on the streets in Guinea.[32]

These accounts of family abuse and neglect as significant motivations for migration are consistent with other research on unaccompanied children who travel to western Europe. For instance, a June 2017 report by UNICEF and REACH found that of 720 unaccompanied and separated children (97 percent of whom were boys) interviewed in Italy in 2016 and 2017, nearly one-third—and almost half of Gambian children—left because of violence or problems at home or with their families.[33]

Armed Conflict and Violence

Some children told Human Rights Watch they were targeted by armed groups or gangs.

For instance, Aliou M., 16, said he left Niger because of attacks by Boko Haram, an extremist armed group whose name in Hausa means “Western education is forbidden.” “Boko Haram placed a bomb at the mosque where my father and mother were praying, and they died. Boko Haram came twice to the house. They beat me at the mosque,” he said, showing us a scar.[34]

Siaka A., a 16-year-old from Côte d’Ivoire, told us that he was singled out by a local gang. “My big brother was in a gang . . . . There was a misunderstanding, so he left. On a Monday night, [the gang] came to get my brother at home, but he wasn’t there. They wanted to hurt us. They cut off my fingertip with a machete,” he said, showing us that one of his fingers was missing the tip.[35]

In some instances, children told Human Rights Watch they or their families were targeted because of their religion, ethnicity, political opinion, or similar grounds. For example,

Ismaila D., a 16-year-old-boy from Guinea, told us that he left because he believes members of his ethnic group are targets of state-sponsored violence. [36]

Musa G., 18 at the time of our interview, told us he fled Guinea-Bissau in 2012 with an uncle after his father, a member of the armed forces, was killed during an attempted coup.[37]

Fode A., a 16-year-old boy from Guinea, told us that he left after his family died of Ebola. Because he was the only survivor, the community blamed him for the tragedy:

My father died when I was a baby, it was my mother who did everything. But at the end of 2013, Ebola touched my whole family. Mom and her brothers died while they were trying to do everything [to take care of us]. I had to leave school because my friends said I had Ebola. They told me they were going to kill me. They said I was the one who brought Ebola [to the community].[38]

Trafficking

In some cases, children told us they had not set out from their homes with the idea of coming to Europe. Some said they were taken outside their home countries against their will. Others said they said that they were misled about where they would be going or what work they would be doing. In such cases, they described circumstances that appear to amount to trafficking.[39]

For instance, Joshua F., a 16-year-old boy from Cameroon, told us that he left Douala with his younger sister and travelled to Yaoundé but never intended to leave his home country. He explained:

A boss offered me a carpentry job in northern Cameroon. I left with my 12-year-old sister. But he kidnapped us and took us to Chad. He turned us over to someone else to work with that person. We did the housework; he didn’t pay us. My sister worked a lot.

I wasn’t the one who decided to leave Cameroon. The gentleman told me there was a job in northern Cameroon. I would not have agreed to go to Chad.[40]

After some months in Chad, a group of armed men abducted him and his sister and took them to Libya.[41]

Others had not intended to cross from Libya to Europe. For instance, Kebba S., a 16-year-old boy from Gambia, escaped from a detention center in Tripoli with about nine other men and boys and were hiding in a field when they were approached by a man who offered to arrange their transport to Tunisia if they paid him. A total of about 50 people boarded an inflatable rubber boat. “There was a compass [for us to use] to head toward Tunisia. Then it started to rain. The compass didn’t work anymore,” he said. After two or three days at sea, a large vessel rescued their boat and took them to Catania, in Italy.[42]

Ill-Treatment in Libya

Nearly all of the 58 children we interviewed who said they had transited through Libya interviewed by Human Rights Watch described being held for ransom and detained in degrading and abusive conditions, forced to work, and subjected to beatings and other abuses while they were in Libya.

Although children usually referred to the places where they were held as “prisons,” most said they were not detained by government agents; the rest did not know who detained them. In one such account, Anthony L., a 15-year-old from Ghana, told us:

In Libya, I was sleeping in a camp in the desert, in Sabha [about 780 km south of Tripoli]. It was like a prison. There was no government, no officials. I was held by bandits. I stayed there for one week. It was very bad.

There were a lot of people, 700 people. They keep you in a room with no food. They beat you. They beat me to get money. They beat me for four days.

In the room, there was no space, you could not lay down. It was very hot. You could only stand, and you could not sleep.[43]

In another such account, Moses P., a 16-year-old boy from Gambia, said of the three months he was detained in western Libya, “It was very difficult, there were beatings and cuts with blades. In prison, I suffered so much. Beatings every day.” He showed us scars on his body that he said were from his time in detention.[44] Gabriel F., a 17-year-old Nigerian boy, said that in the place he was held in Tripoli, his captors “were taking girls to sleep with them.”[45]

Overcrowding, unsanitary conditions, and inadequate and often bad food were the norm in the places where children were held, we heard. “There were 10 to 15 people in each room, it was hot, so hot. There was only a small window,” Sékou M., a 16-year-old from Mali, told us.[46] Louis M., another 16-year-old boy from Mali, gave a similar account of the place he was held for a month in Libya: “In the prison, there was no window, there were many people. I did not eat much, only rolls.”[47] Oussenyou A., a 16-year-old boy from Guinea who said he spent a year in Sabratha, about 80 km east of Tripoli on the Mediterranean coast, told us, “We didn’t eat every day in Libya. Even the water wasn’t good. It was very difficult.”[48]

Children described being forced to work in fields or on construction sites if they were unable to arrange ransom payments from relatives. Joshua F., a 16-year-old from Cameroon, told us that after he and his younger sister were abducted in Chad, they were taken to Libya—he did not remember precisely where—and held by armed men. He said:

I was a victim of slavery. I was working in the fields [and] in construction sites. I managed to escape [from the first place he was held] but was caught and put in another prison. The [men] mistreated us and told us to call our parents to ask for money. But I do not have parents, so one day, a [man] killed my little sister in front of me. In the other prison, I worked in olive fields to pay the prison. The prison took the money.[49]

In a similar account, Siaka A., a 16-year-old from Côte d’Ivoire, told us that because he had nobody to call to arrange payment, “I was sold to someone to work. They did not give me money. I worked for two months cutting the grass for the sheep.”[50]

Many children said they endured physical abuse while they worked. Aliou M., a 16-year-old from Niger who told us he worked without pay in Libya for 10 months, said he regularly endured beatings from the man he worked for. “He hit me a lot, with a motorcycle cable, with sticks,” he told us.[51]

One boy told us he was repeatedly sexually assaulted for more than a year by a man who took the boy to his home.[52]

As with Joshua, the 16-year-old Cameroonian boy who saw his sister killed in front of him, other children told us that siblings or other relatives died from accidents or ill-health while they were in Libya. “I was separated from my big brother in Libya and later learned that he had died,” said Ousmane A., a 17-year-old from Guinea. He did not know the circumstances of his brother’s death.[53]

In other cases, children were separated from family members when they were detained in Libya and still did not know at the time of our interview what had happened to their relatives. Ajuma L., a 16-year-old from Gambia, said that he had not seen his brother since their detention in Libya in 2018.[54]

While it appears that the children interviewed in this research experienced abuses in smuggler captivity, children detained in official government detention centers in the western part of the country face similar conditions and treatment. Human Rights Watch and others have documented abuses against children in these official centers, including detention alongside unrelated adults, forced labor, beatings by guards, lack of access to healthcare, lack of adequate nourishment, and lack of access to education.[55]

Despite the well-documented abuse of migrants in Libya, the European Union maintains migration cooperation with the Government of National Accord, one of the two authorities contesting territorial and political control in Libya. The EU—and France—provides support to the Libyan Coast Guard to enable it to intercept migrants and asylum seekers at sea after which they take them back to Libya to arbitrary detention, where they face inhuman and degrading conditions and the risk of torture, sexual violence, extortion, and forced labor.[56]

A 2017 study of 19 unaccompanied children aged 16 and 17 who arrived in Italy found that all had suffered physical and psychological abuse at least once before and during their journeys, particularly in Libya; half of those who took part in the study had been sexually abused.[57] Similarly, an assessment by UNICEF’s Libya Country Office in 2016 found that migrant children and adults experienced high levels of sexual violence, extortion, and abduction while in Libya.[58]

The Perilous Sea Crossing

We were on a Zodiac that normally took 70 people, but we were 185 people, we were packaged like sardines. Thank God there were no deaths. It was a big MSF boat, the Aquarius, that saved us.

—17-year-old Ousmane A., from Guinea

The boat was [inflatable,] like a balloon. I started crying. I was feeling very weak. Lots of people were on board. There was a pregnant woman and six or seven babies. The boat started leaking. I was so afraid.

—Gabriel F., a 17-year-old boy from Nigeria

Children described being taken to boats, usually inflatable vessels known as Zodiacs, and forced to board despite their fears that the vessels were already overcrowded. Ismaila D., a 16-year-old boy from Guinea, said that when his group was at the beach, armed men hit them until they boarded.[59] Sixteen-year-old Tahirou B., from Mali, gave a similar description, saying, “A man refused to get on the boat, so someone hit him with a baton.” He added, “It was the first time that I saw the sea, and I didn’t want to get in. But we were being hit, so I climbed in.”[60] Joshua F., a 16-year-old from Cameroon, told us, “There were many Arabs shooting in the water, forcing us into the water and making us get onto the boat. I lost a lot of friends” in the confusion that resulted.[61]

We heard numerous accounts of smugglers disabling or removing engines and leaving full boats to drift. “When the boat was in the sea, the Arabs took the engine. I thought they wanted to kill us. . . . We spent a lot of time on the water. There were people with bullet wounds and knife wounds. There were pregnant women on board,” 16-year-old Ismaila said.[62]

In some cases, children told us the boat ran out of fuel or the engine simply stopped working. Fifteen-year-old Issa B. from Mali made the crossing in 2018, in a boat that held more than 100 people. “We ran out of gas, we couldn’t move,” he said.[63]

And in other cases, children said that smugglers simply departed after handing telephones to migrants or pointing them toward Europe. “The Arabs accompanied us to a certain point and then they boarded jet skis and left,” Joshua F., a 16-year-old from Cameroon, said.[64]

Sidiki A., a 16-year-old boy from Guinea, described his boat’s rescue after five hours on the sea:

People were vomiting because of the waves. The women were crying. I was scared because I did not know where I was going and I do not know how to swim.

Around 8:00 a.m., we saw a helicopter in the sky. A few minutes later, a small boat with two people came very fast. They told us not to move around. Around 10:00 a.m., they came back and gave us life jackets. Then they left. At 11:00 a.m., the big boat arrived and rescued us.[65]

Sékou M., a 16-year-old boy from Mali, told us his brother died when their boat capsized in the Mediterranean.[66] Issa B., the 15-year-old, also from Mali, told us that another boy he was travelling with drowned when they crossed the Mediterranean. “We were in the same boat, but he died. . . . Many people fell out, all died” when the boat went through heavy waves, he told us.[67]

In some cases, children rescued at sea remained on rescue vessels for days or weeks before the vessels were allowed to dock in Italy. Ousseynou K., a 16-year-old from Guinea, said that after he and others were rescued from their boat, they waited on a vessel he described as “a large international boat” before Italian authorities would allow them to disembark.[68]

Neglect and Abuse in Italy

I tried to go to school [in Italy], but the people at the center turned me down. I tried to ask for training in computers; they refused. There was nothing to stay for and nothing to do. We had two choices: eat and sleep, and nothing more. Nothing else.

People insult you on the street: vaffanculo (“fuck off”), negro di merda (“black piece of shit”). . . It’s unbearable for us.

—Amadin N., 17, who spent 12 months at a reception center for unaccompanied children in Naples[69]

All of the children we interviewed who had spent time in Italy before coming to France said that they left Italy in large part because of the combination of lack of access to education and health services, inadequate living conditions in the reception centers where they were housed (which they referred to by the Italian word campo, “camp”), and discriminatory attitudes. These were not the only factors that children cited when explaining why they chose to travel to France—in particular, children from French-speaking countries frequently mentioned the shared language and what they saw as a shared history between their countries of origin and France—but it was striking that many of the children we spoke with said they had spent at least six months in Italy before deciding to leave, suggesting that they had not arrived in Europe with the definite idea of France as their destination.

Lack of access to schooling was children’s most frequent complaint about their life in Italy. Nearly all said that they were only able to attend Italian lessons. Children who attended said the lessons were irregular and so short that they could not speak Italian even after a year or more in Italy.

“If I could have had school, that would have made me happy. In the campo, school was two times a week for one hour. It’s not sufficient. I stayed at the campo for six months. I left the campo because I have to finish school and learn a trade,” Sékou M, a 16-year-old boy from Mali, said of his reception center in Foggia, near Bari.[70] In a similar account, Fode A., also 16, from Guinea, said, “We wanted to go to school. But we didn’t go for six months. And even when we went to school [for language lessons], it wasn’t the right way [to learn]—only two times a week.”[71]

Children were particularly conscious that they were not attending classes with Italian students, which many took as an indication that they were not getting the same education that Italian children would receive. “The school was just to know how to write the language. It was inside the campo and there were only black students,” Ajuma L., a 16-year-old Gambian boy, said.[72]

Many children also said they had not received needed medical care in Italy. As one example, Mbaye T., a 15-year-old from Senegal, said he told the staff at his campo in the province of Cuneo, south of Turin, that he had sickle cell anemia but did not receive treatment.[73] We heard from other children who said they did not receive medical care while in Italy. For instance:

- “In Italy, I asked several times to see a doctor, but I only saw him once and the doctor did not give me any medication,” Louis M., a 16-year-old from Mali, told us, saying that he spent six months in a reception center near Milan.[74]

- “In the campo, my head hurt and my foot was injured. I never saw a doctor or received medication,” said 15-year-old Issa B., also from Mali, who said he was placed in a reception center in Enna, a town in Sicily near Catania, where he stayed for about six months.[75]

- “My stomach hurt, I cried, but I was never taken to the hospital. I asked for a doctor. I cried, but I was not looked at. I never saw a doctor” during the six months he was in a reception center in Catania, Joshua F., a 16-year-old from Cameroon, said.[76]

Racist insults and other discriminatory interactions were another factor in some children’s decision to leave Italy, they told Human Rights Watch.[77]

Some children also described overcrowding and unsanitary conditions in their reception centers.[78] Some said their reception centers housed a mix of adults and children.[79]

These accounts are consistent with reports of nongovernmental organizations and Italy’s children’s ombudsman. Italy’s reception system for unaccompanied children is at capacity, with just over 3,700 places available in January 2019 for more than 10,000 unaccompanied children in the country.[80] As a result, unaccompanied children are also held in temporary facilities[81] and at times in reception centers together with adults.[82] Conditions vary widely in facilities across the country, but access to education and health are concerns in many centers.[83] In Sicily, in particular, unaccompanied children are often placed in centers located far from urban areas, with little access to schools and health services, the nongovernmental organization InterSOS reported in April 2019.[84]

The European Asylum Support Office’s 2018 guidance on reception conditions for unaccompanied children calls for unaccompanied children to have access to education, health care, and psychosocial support while they are in the care of EU member states.[85] In addition, the European Commission has called for member states to “establish procedures and processes to help identify durable solutions on an individual basis . . . in order to avoid that children are left for prolonged periods of time in limbo as regards their legal status.”[86]

In 2017, Italy enacted a new law for the protection of unaccompanied migrant children[87] that has been hailed by some human rights groups and UNICEF.[88] Nonetheless, the Association for Legal Studies on Immigration (Associazione per gli Studi Giuridici sull’Immigrazione) has identified significant protection gaps remaining under the new law,[89] and Oxfam has noted significant problems with the law’s implementation, including access to education and information about seeking asylum in Italy or requesting reunification with family members in other EU member states.[90]

Before the law was passed, human rights groups reported that unaccompanied children were not receiving enough food and clothing in some reception centers[91] and that some were placed in centers for adults.[92]

In addition, several children cited Italy’s new immigration law, often known as the “Salvini Decree,” which ended humanitarian protection permits for adult asylum seekers, limited access to shelters for asylum seekers, increased permissible detention periods pending deportation, and made it easier for Italian authorities to revoke refugee status.[93] The new law does not directly affect the situation of unaccompanied children, who are eligible for shelter in dedicated reception centers and, after reaching the age of 18, continue to receive shelter until their asylum claims are heard, [94] but the children who mentioned it took it as a sign that they were not wanted in Italy.

Replying to our request for responses to these accounts, the Italian Ministry of the Interior stated that all unaccompanied children are placed in dedicated shelters, where they have access to education, and that all unaccompanied children are entitled to health care in Italy, including before they receive permits to remain in Italy. The ministry also stated that it issued written standards for reception centers in 2016 and is in the process of revising the standards to reflect the 2018 immigration law. Finally, the ministry told us that it has conducted numerous visits to receptions centers, noting that shortcomings discovered on these visits may give rise to disciplinary measures and in serious cases the closure of the center and legal proceedings.[95]

“Children tell us, ‘In Italy, we have no hope,’” said a volunteer with Tous Migrants in Oulx, the last major town in Italy before the border with France.[96]

II. Police Pushbacks

Crossing the border is a matter of luck with the police. It depends on their mood.

—Amadin N., 17, Benin, interviewed in Gap in January 2019

French border police sometimes return unaccompanied children to Italy summarily, without affording them the legal safeguards to which they are entitled under French law.

Human Rights Watch heard nine accounts from children who said they were summarily returned to Italy by French border police, including children who attempted to cross between Bardonnechia and Modane, in the Savoie department, and between Ventimiglia and Menton, in the Alpes-Maritimes department, as well as those who were apprehended in the Hautes-Alpes department. Two of these children told Human Rights Watch that police did not ask their ages before summarily returning them, and seven said the border police returned them to Italy even after they said they were under age 18. All nine crossed the border on subsequent attempts.

We also heard of six cases in which border police accepted children’s stated age. There was no discernible pattern: some of those accepted by police had birth certificates but others did not; some were among the youngest children we interviewed, while others were 17; and even though all looked very young, many of the children who said they were summarily returned also looked very young. Rather, it appeared to be a matter of individual officers’ whim.

When we raised these cases with the Hautes-Alpes prefecture, Jérôme Boni, border police director for the Hautes-Alpes and Alpes de Haute-Provence, told us, “Everybody who claims to be a minor is treated as such. That’s at border posts, if they’re intercepted on a road, on a trail, in the mountains.”[97] But entry refusal documents viewed by Human Rights Watch do not substantiate his description of border police procedures: in October 2018, for instance, two migrants who told border police they were under age 18 received entry refusal documents stating that they had “refused to make a coherent declaration of identity” (“refuse de déclarer une identité cohérente”) and noting that border police judged that they appeared to be adults (“apparence Majeur”).[98] The nongovernmental organization Anafé has also observed refusal documents “bearing the indication ‘adult appearance.’”[99]

French law allows for an expedited process, “refusal of entry” (refus d’entrée), for children and adults who are stopped within 10 km of a land border and found to be in France irregularly. French border police refused entry to 315 persons in 2016, 1,899 in 2017, and 3,787 in 2018, the prefecture told Human Rights Watch. In the first five months of 2019, police refused entry to 781 persons—about the same number as in the first five months of the previous year, when 718 were refused entry.[100] The border police director told us that all refusals of entry were of adults, adding that in 2018, police stopped an additional 635 persons who identified themselves as children, and in the first five months of 2019, 147 who said they were under age 18. None of these individuals claiming to be a child was refused entry, he told us.[101]

In cases of refusal of entry, police must notify the person in writing, in a language the person understands, of the reasons for refusal of entry and the rights to seek asylum and to appeal the refusal. Children should be appointed a guardian and should be treated as “vulnerable” and given “particular attention.”[102] The notice of refusal of entry includes information about the person’s identity, including their date of birth. French police give a copy of the notice to Italian authorities, the border police director told us, adding that Italian authorities in Piedmont do not accept returns of children.[103]

EU regulations do not require Italy to accept such returns of unaccompanied children and in fact prohibit the return of unaccompanied children who seek asylum in France or who have family members in France.[104] Under French law, unaccompanied children who are not subject to refusal of entry should be referred to French child protection authorities. Human Rights Watch’s interviews indicate that French border police and other French law enforcement authorities do not regularly follow the procedures described to us by the border police director.

For instance, 17-year-old Amadin N., from Benin, told us that he was turned back by French border police on his first attempt to enter France. “I showed my papers that said that I was a minor, but the police didn’t want to hear it,” he told Human Rights Watch. The border agents did not offer him a copy of the refus d’entrée (refusal of entry) form, he said.[105]

Ibrahim F., a 17-year-old Gambian boy, one of the two children we spoke with who was summarily returned without being asked his age, told Human Rights Watch that he heard from others in his group that the border police asked two other boys their age and allowed them to continue into France. He did not realize at the time what police were asking the other boys because he did not understand French. Police held him and the rest of the group for two hours before returning them to Italy.[106]

The other boy who told us police did not ask his age before returning him to Italy, 16-year-old Ismaila D., from Guinea, said that when he tried to enter France by road in a group, the police returned all of them without asking ages: “We walked along the road, a lot of us. The French police had a roadblock, so we were returned to Italy. They didn’t ask my age.”[107]

Issa B., a 15-year-old boy from Mali, told us that French border police returned another boy and him after they tried to travel to France by bus:

We took the bus to cross the border at Bardonecchia. The police caught us at the border at Bardonecchia. They took us to an office. That lasted from 8:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m. The French police called the Italian police. They didn’t come very quickly. The French police asked if I was a minor. I said yes. They told me that if I didn’t have any documents or a passport, I couldn’t enter. They wrote something on a paper, but they didn’t give it to me, they gave it to the Italian police.[108]

In one case, a boy said the French border police entered the wrong year of birth on the refusal of entry document, so it listed him as an adult. Kebba S., a 16-year-old from Gambia, told us that on his first attempt to cross into France:

Yesterday, once I reached [the Italian town of] Oulx, I took the train to Modane [in France]. When I got off the train, the police caught me. They asked what country I was from and my age. Then they filled out a document that I couldn’t enter the country. I gave them my date of birth, 2002, but I saw that when the police officer filled out the document, he put another date of birth, 2000. I refused to sign the document. The police then took me and put me on the train to go back to Italy.[109]

Six children told us they were allowed to continue their journey into France after police stopped them. In most of these cases, border police arranged transport for the children. For instance, when Mbaye T., a 15-year-old boy from Senegal, crossed from Italy into France, he said, “I left for Claviere, and I went through the police post [outside Montgenèvre.] Seeing me, the police officer said he was going to call somebody to take me to Briançon.”[110] Sayo A., a 16-year-old Senegalese boy, told us that border agents arranged for him to be taken to a hospital when he told them that he was having trouble walking:

I arrived alone at the border, at Claviere. It was night, I started to walk on my own through the snow. I walked in the mountains from 1:00 a.m. to 7:00 a.m. At 7:00, I saw the French police station on the border. I went up to the police, my feet hurt too much. They asked my age, I said I was 16. I said that my feet hurt a lot. They called me an ambulance, which took me to the hospital in Briançon.[111]

Similarly, Malick I., a 15-year-old from Gambia, told Human Rights Watch that after he showed the border police a photo of his birth certificate on his phone, they called the health center in Briançon to pick him up.[112] Another boy, Ramatoulaye M., a 16-year-old from Côte d’Ivoire, said that after border police apprehended him in the mountains near Montgenèvre, they called a volunteer to drive him to the shelter.[113]

In other cases, the border police simply allowed children to walk on, as with 17-year-old Habib F., from Senegal, and Fakkeba S., also 17, from Gambia.[114]

In the cases in which police did not summarily return children to Italy, three were 15, and all looked very young. Three, including a 17-year-old, had copies of their birth certificates.[115] One boy’s successful entry seems to have been the result of persistence:

The French police sent me back four times even though I said I was a minor. The fifth time, when we arrived at the French border post, an officer saw us, the same one as the other times. He said the minors could enter but not the adult with us. “The minors have priority,” he said, so the adult was sent back.[116]

When 13 nongovernmental organizations documented police practices on the border between Claviere and Montgenèvre in an October 2018 observation mission, they found substantially the same abuses.[117] “We collected testimonies about modified birth dates, identity papers thrown to the ground or torn by police,” said Agnès Vibert Guigue, a lawyer who took part in the observation.[118] French and Italian nongovernmental organizations have reported similar conduct by French border police operating in and around Menton, the French town in the Alpes-Maritimes department across the border from Ventimiglia, Italy.[119]

Volunteers and activists who take part in mountain searches in the Hautes-Alpes gave similar accounts. “There are refusals [to accept] minor age by the PAF [the French border police], rejection of papers, sometimes destruction of identity documents (including birth certificates). The last instance was yesterday,” one volunteer told Human Rights Watch in late January. “There are also instances of sick minors left on public roads,” he added.[120]

To avoid apprehension by border police and possible summary return, children told us they walked high into the mountains, increasing their risk of frostbite and exhaustion. “We heard that if the police caught us, they would send us back to Italy,” Issa B., a 15-year-old Malian boy said, explaining why the group he travelled with walked high through the mountains.[121] “We walked a long way in the mountains to avoid the police,” said Eva L., a 17-year-old girl from Guinea.[122]

Protection Against Summary Returns

France reintroduced border controls at its land borders with other EU member states in December 2015, after attacks in Paris, and has regularly renewed immigration controls since then.[123] While the reintroduction of these land border controls is in effect, French authorities can conduct immigration checks within 20 km of a land border with another EU member state as well as at international train stations, marine ports, and airports.[124] When border police or other authorities conduct these checks, they verify identity, including name, surname, and date and place of birth. French law provides that individuals who declare that they are under the age of 18 receive the benefit of the doubt, meaning that they are treated as children in the absence of substantiated reasons to believe they are adults.[125]

Those who are found to be in France irregularly may be subject to an expedited procedure, “refusal of entry” (refus d’entrée), if they are stopped by police within 10 km of the border with another EU member state while the reintroduction of land border controls is in effect.[126] In such cases, authorities should issue a written refusal to a person found to be in France irregularly,[127] using a language the individual understands, and should inform the person of the right to seek asylum and the right to appeal the refusal of entry, among other rights.[128] Children may be refused entry, but they should be appointed a guardian.[129] The law also provides that “[p]articular attention is given to vulnerable people, especially minors, unaccompanied or not by an adult.”[130]

A child who is stopped outside of the 10 km border zone is not subject to the “refusal of entry” procedure and is not subject to expulsion or removal.[131] Authorities should treat unaccompanied children stopped outside the 10 km border zone as children in need of protection and should refer them to child protection authorities.[132]

The children interviewed by Human Rights Watch all appeared to have been stopped by police within 10 km of the border with Italy. But in the cases of children who described summary returns to Italy, police did not appear to have afforded the limited procedural protections required by law—police did not always give children written notice of the reasons for refusal, did not appear to take the steps necessary for the appointment of guardians, did not routinely ask children their ages, and in one case recorded a date of birth that was different from what a child claimed. These accounts are at odds with the procedures described to us by the border police director for the Hautes-Alpes and Alpes de Haute-Provence.[133]

Under the EU Asylum Procedures Directive and the EU Dublin III Regulation, unaccompanied children who have applied for asylum in France should not be returned to Italy.[134] Returning unaccompanied children without notifying them of their right to apply for asylum and affording them the opportunity to do so also violates the Asylum Procedures Directive.[135] In addition, unaccompanied children with family members in France have the right to family reunification under the Dublin III Regulation, meaning that those children should also not be returned to Italy.[136]

The accounts we heard from children as well as from volunteers and activists are consistent with the findings of the National Consultative Human Rights Commission (Commission nationale consultative des droits de l’homme, CNCDH), the Inspector General of Places of Deprivation of Liberty (Contrôleur général des lieux de privation de liberté), and the French Defender of Rights (Défenseur des droits). In 2018, the CNCDH found that many unaccompanied children were returned without the procedural protections required by French law, including the appointment of a legal guardian, and also noted reports of police altering birth dates on refusal documents.[137] With respect to these practices in the Alpes-Maritimes department, the Inspector General of Places of Deprivation of Liberty found in 2017 that French police summarily returned unaccompanied children to Italy.[138] Also with regard to practices in the Alpes-Maritimes, the Defender of Rights found that the return of unaccompanied children to Italy without these procedural protections was “contrary to the Convention on the Rights of the Child and does not respect the procedural guarantees set forth in European law and French law.”[139]

III. Arbitrary Age Assessment Procedures

You gather up your courage with both hands to tell your story, and you are told you are lying. It cannot be right.

— Amadin N., 17, Benin, interviewed in Gap in January 2019

In cases reviewed by Human Rights Watch, unaccompanied migrant children arriving in the Hautes-Alpes were frequently denied formal recognition as children in age assessment procedures that placed undue weight on minor inconsistencies with dates, reasons such as working while in home countries, or officials’ ad hoc assessments of their physical and psychological “maturity”—all factors that either have little or no bearing on their declared age or cannot determine age with precision.

Many of the children interviewed for this report said that they did not understand the interpreters assigned to their age assessment interviews. Many also said they could not answer questions effectively because they did not know the purpose of the questions, felt the official did not want them in France, or were exhausted from their journey and in some cases injured. The few children who had birth certificates or other identity documents told us that their documents were nearly always referred to border police for authentication, despite the presumption in French law that foreign documents are valid in the absence of substantial reason to doubt their legitimacy.

Children receive emergency shelter and access to other social services after an evaluation determines that they are under age 18,[140] meaning that formal recognition as a child is a crucial first step for unaccompanied children to receive protection and care in France. Entry into the child protection system can also lead to access to regular immigration status upon adulthood.[141]

Because many children do not arrive with birth certificates or other identity documents, assessment procedures should enable authorities to establish age through comprehensive interviews by psychologists, social workers, and other professionals.[142] French regulations provide that age assessments should be conducted in a manner “characterized by neutrality and compassion.”[143] Following international standards, age assessments should give the benefit of the doubt when there is a reasonable possibility that the declared age is correct.[144]

In the Hautes-Alpes, the Departmental Council’s Directorate of Prevention Policy and Social Action (Direction des Politiques de Prévention et de l’Action Sociale) conducts these age assessments.[145] Elsewhere in France, some departments delegate this function to nongovernmental organizations.[146]

The Hautes-Alpes prefecture told Human Rights Watch that it had taken 2,503 unaccompanied children into care in 2018 following age assessments.[147] Separately, the Departmental Council’s Directorate of Prevention Policy and Social Action told Human Rights Watch that it undertook “close to” 2,846 age assessments in total in 2017 and 2018, an average of 1,423 each year.[148] The number given by the prefecture of children formally recognized and taken into care is also substantially higher from that reported by the Ministry of Justice, which states that the Hautes-Alpes department recognized 381 unaccompanied children in 2018, of which 351 were then transferred to other departments under the allocation system known as répartition nationale. An additional four unaccompanied children were transferred to the Hautes-Alpes from other departments, according to the Ministry.[149]

Human Rights Watch interviewed 35 children who had undergone age assessments in the Department of Hautes-Alpes. Two were formally recognized as children in these age assessments; the others received negative evaluations. Seven of those who received negative evaluations were eventually recognized formally as children after a juvenile court judge (juge des enfants) reviewed their cases. We reviewed an additional 36 evaluation reports prepared by the Departmental Council to explain the outcome of age assessments, as well as 13 juvenile court judgments that reviewed negative age assessments made by the Departmental Council.

The age assessment evaluation should take the form of a “multidisciplinary” interview that includes questions about the youth’s family background, reasons for leaving the country of origin, and plans for the future.[150] Age assessments conducted in the Hautes-Alpes department cover these topics but, in the cases reviewed by Human Rights Watch, it is not apparent that they fulfil the regulatory requirement that they be multidisciplinary in nature. Children told us they were interviewed by a single official with the assistance of an interpreter. Nothing in the evaluation reports suggests what, if any, diagnostic criteria were employed to assess responses, whether the decisions are the outcome of evaluation by a multidisciplinary team or a single individual, and, if by a single individual, how the Departmental Council ensures that the assessment meets the requirement that it be multidisciplinary in character.

The Departmental Council declined our requests for a meeting to discuss these findings and, in response to our request for comment, wrote:

Although it is particularly concerned with and involved in the reception and shelter of unaccompanied minors on its territory, the departmental institution will not provide detailed answers to the many questions asked in your correspondence. Their reading reveals a clearly biased and unjustly critical approach and interpretation of the procedures put in place by the Department. They seem to argue that the Hautes-Alpes Departmental Council disregards the most fundamental principles in respect of the rights of the young people who are welcomed and evaluated. These allegations, made against an institution whose essential mission is solidarity, are unworthy.[151]

Those who are not found to be under the age of 18 as a result of this interview should receive a “reasoned decision” from departmental authorities.[152] In fact, they ordinarily receive a form letter stating simply that they have not been recognized as a child.[153] The complete evaluation report is not available to them unless they or their lawyer requests it.[154]

They may seek review of adverse age assessments, a procedure before the juvenile court judge that frequently takes months.[155] Alternatively, in a procedure that some lawyers have employed successfully in the Hautes-Alpes, a family court judge (juge des tutelles) can determine that a person is a child in need of protection, a finding that includes a determination of the person’s age.[156]

Although this report focuses on the Hautes-Alpes department, Human Rights Watch has found similarly capricious decision-making in Paris[157] and has heard accounts of arbitrary age assessment practices elsewhere in France.

Poor Interpretation

We heard frequent complaints about the quality of interpretation for all languages, including English. Children said that interpretation by telephone, the usual practice in the Hautes-Alpes, was particularly difficult to understand. Among the accounts we heard:

- “The translator couldn’t come so he was translating through the phone. I couldn’t hear him well. He didn’t understand my English and I often didn’t understand what he was saying,” Gabriel F., a 17-year-old from Nigeria, told us.[158]

- “At that time, I didn’t understand anything of French, even if you asked me my name. The translator on the phone tried to speak my language. She said she understood, but she didn’t get anything. She spoke Senegalese Peul and I speak Guinean Peul,” said Sidiki A., a 16-year-old Guinean boy. When he received the decision informing him of the negative age assessment, he saw that it inaccurately reported what he said in the interview. “In the evaluation report, there were a lot of differences. It wasn’t what I said. I didn’t say that,” he told us.[159]

- Ismaila D., another 16-year-old from Guinea, said, “There was a Peul translator on the phone but it was Senegalese Peul so I didn’t understand very well.”[160]

A lawyer who has represented unaccompanied children after they received negative age assessments told us that in her experience: