Summary

In July 2016, 15-year old “Rouhiya” fled her sexually abusive father and sought refuge at the house of a 23-year-old man who had promised to marry her.[1] Soon after, she said, the man locked her up, drugged her, and gang-raped her with three other men. Rouhiya remained captive for two weeks until the police found her and returned her to the home from which she had tried to escape. In her report to the police, Rouhiya disclosed that she knew one of the perpetrators. Police arrested her and sent her to the national women’s prison on charges of engaging in sexual relations outside marriage (zina). “I asked them, ‘Why? What did I do?’,” Rouhiya said. “They told me to keep quiet and not to ask questions.”

Few survivors of sexual assault dare to speak out in Mauritania. Those, like Rouhiya, who report it to the authorities must navigate a dysfunctional system that discourages victims from pressing charges, can lead to re-traumatization or punishment, and provides inadequate victim-support services.

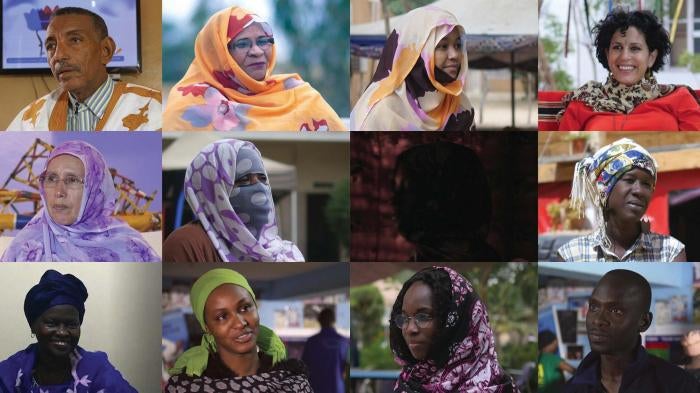

This report documents the institutional, legal, and social obstacles that survivors face in reporting incidents of sexual assault to the police, seeing perpetrators brought to justice, and obtaining medical and psycho-social support. Human Rights Watch interviewed 12 girls and 21 who described one or more incidents of sexual assault. Researchers also visited the national women’s prison and interviewed three women who were detained on charges of zina, two of whom said they were victims of sexual violence.

Social pressure and stigma, both in the home and community, can be major obstacles to overcome for survivors of sexual violence. Mariama reported being raped by a taxi driver when she was 20 and too worried to tell her parents about the assault: “When I was eight months pregnant, my mother realized it, and asked me how it happened. That’s when I told her about the rape,” said Mariama. “My father got very angry. He took me to the police station and told policemen that his daughter should be locked up because she had slept with a man, that he didn’t want her anymore in his house.”

Despite the 2017 adoption of a new law on reproductive health and of a General Code on Children’s Protection, Mauritanian law does not adequately define and criminalize sexual violence. The lack of a definition of rape and other forms of sexual assault in domestic law and the criminalization of consensual sexual relations heightens the risk for survivors that they themselves may be prosecuted: if women and girls cannot convince judicial authorities that a sexual act was nonconsensual, they can find themselves transformed from accuser into accused.

Mauritania also lacks state-funded programs and care facilities to ensure and support survivors’ safety, legal action, and recovery. The government has not created or funded shelters offering accommodation options to survivors who want, or are forced, to leave their home after an assault, or for women leaving prison who have nowhere to turn after being convicted of zina.

In addition to societal pressure to remain silent about sexual assault, survivors confront institutional barriers that include police and judicial investigative procedures that are not gender-responsive, do not ensure privacy or confidentiality, and can turn into a probe of the moral character of the complainant. Zahra, a woman in her twenties, reported being raped by a neighbor who lived in the same informal settlement as her family and who threatened to kill her. The social worker who supported her throughout the course of legal action recalled the demeanor of the state prosecutor who met with Zahra after the assault: “He asked her: ‘If you didn’t consent, why didn’t you tell your parents? Did you know him?’,” she said. “When Zahra opened up, he responded: ‘That’s not true. All the things you are saying are lies, you did this willingly.’”

Lack of forensic expertise and of standardized evidence collection protocols for both law enforcement and health professionals can weaken a survivor’s case in court. Most public hospitals and health centers offer limited emergency care and often refuse medical examinations of survivors without a police referral. Some health professionals seem reluctant to examine survivors, fearing retaliation by alleged perpetrators if their medical assessment leads to prosecution or conviction. Follow-up medical consultations are rare because many survivors cannot afford emergency or long-term medical care. Some families cannot even afford the cost of transportation to medical facilities. Abortion is criminalized and legal only when the woman’s life is at risk.

Survivors of sexual assault who wish to press charges also risk being prosecuted for zina, which not only punishes victims but also deters them from reporting sexual assault to the police in the first place. A person charged with zina can be placed in pre-trial detention and, if convicted and sentenced to flogging or death by stoning, face indefinite prison time because Mauritania has observed a moratorium on executions and corporal punishments provided by Islamic law since the 1980s. While under Mauritanian law, zina charges only apply to “adult Muslims,” some prosecutors also prosecute girls for zina, especially if they are pregnant, even when they report their pregnancy was due to rape. Girls can end up in pre-trial detention or serve jail time in the same facilities as women detainees, a violation of the principle of separation guaranteed under international law.

In addition to breaching the right to privacy, zina charges are applied in a way that discriminates on the basis of sex because pregnancy serves as “evidence” of the offense, even when women and girls may report it was the result of rape. Mauritanian lawyer Aichetou Salma El Moustapha, who represents women and girls supported by the Mauritanian Association for the Health of the Mother and the Child, told Human Rights Watch: “For rape cases where the complainant is a minor, when the girl becomes pregnant, she’s convicted for zina because according to the judge’s reasoning, if a girl becomes pregnant, her body is mature—she can conceive a child and is thus, legally speaking, an adult.”

Mauritania has in recent years moved towards improving the legal landscape for women, girls, and survivors of sexual violence. In March 2016, the government approved a draft law on gender-based violence—still pending before parliament—that would define and punish rape and sexual harassment, create specific sections in criminal courts of first degree to hear sexual violence cases, consolidate criminal and civil court proceedings to favor prompt compensation of survivors, and allow civil society organizations to bring cases on behalf of survivors.

However, while a step in the right direction, the current draft falls short of international standards in several ways: it includes a restrictive definition of rape; fails to criminalize other forms of sexual assault; includes an explicit provision that criminalizes consensual sexual relations outside marriage; and fails to repeal domestic law provisions criminalizing abortion.

International human rights law obligates Mauritania to protect individuals within its jurisdiction from all forms of violence, including by taking appropriate measures to prevent, punish, investigate, or redress harm to an individual’s rights whether the harm stems from acts by private individuals and entities, or state employees and institutions.

The government’s ongoing prosecution for zina and its failure to ensure access to justice, effective remedies, and care facilities for sexual violence survivors—predominantly women and girls—violate several human rights. These include their right to nondiscrimination—as sexual violence affects women disproportionately—as well as their right to bodily integrity and autonomy, their right to privacy, and their right to an effective remedy.

To better protect women and girls from sexual violence and to comply with its international human rights obligations, Mauritania should:

- Impose an immediate moratorium on prosecuting and detaining individuals for zina;

- Immediately release all individuals currently in detention on zina charges and move towards abolishing this criminal offense;

- Pass a law on gender-based violence that defines the offense of rape, criminalizes all other forms of sexual violence, imposes adequate and proportionate sentencing for alleged perpetrators, decriminalizes consensual sexual relations, creates specialized prosecutorial units and shelters throughout the country equipped to house women and children on a short, medium, and long-term basis, and allocates adequate funding to implement such reforms;

- Increase its capacity to provide survivors safe spaces beyond the few emergency accommodation options currently offered by civil society organizations;

- Craft gender-responsive investigative trainings and require law enforcement officials to take them periodically, and ensure that they, along with judges and health professionals, follow forensic protocols specific to sexual assault cases; and

- Ensure greater access to medical care for survivors, including psychological support.

Recommendations

To the National Assembly

- Review and adopt the draft law on gender-based violence, after amending its provisions to comply with Mauritania’s international human rights obligations, ensuring it adequately takes all feasible measures to prevent and deter gender-based violence, protect survivors, and prosecute perpetrators including by:

- Repealing provisions in the Penal Code criminalizing consensual sexual relations, other “moral crimes,” and abortion.

- Criminalizing all forms of sexual assault (both perpetrated and attempted) and gender-based violence, including female genital mutilation and early, child, and forced marriages.

- Providing clear definitions of notions such as sexual assault, attempted rape, rape (including marital rape and penetration with an object), gender-based violence, consent, and inhumane practices, in line with international standards (see below).

- Providing for mandatory, periodic, and institutionalized training and awareness-raising programs on gender-based violence and adequate institutional responses for law enforcement officials, judges, and health professionals.

- Providing for the creation of special prosecutorial units specialized in gender-based violence while ensuring witness protection and preventing stigmatization of sexual violence survivors.

- Providing funding for the implementation of measures within the law, particularly for the creation of shelters providing short-, medium-, and long-term accommodation options to sexual violence survivors, awareness-raising campaigns, new means of forensic testing including DNA evidence, and specialized police, prosecutorial units, and court sections to investigate and hear cases of sexual violence.

- Clarifying how the draft law will interact with other existing laws such as the General Code of Children’s Protection, the law on reproductive health and the Penal Code.

- Repeal article 306 of the Penal Code prohibiting, among other things, offenses to public decency and Islamic morals; these charges are sometimes used as a fallback provision to punish consensual sexual relations outside marriage.

- Repeal article 307 of the Penal Code, which criminalizes consensual sexual relations outside marriage (zina).

- Repeal article 293 of the Penal Code and article 22 of the 2017 law on reproductive health criminalizing abortion.

- Amend article 309 of the Penal Code to define rape either as a physical invasion of a sexual nature of any part of the body of the victim with an object or sexual organ without consent or under coercive circumstances and explicitly criminalize marital rape or by providing for a broad offense of sexual assault, defined as a violation of bodily integrity and autonomy, graded based on harm, and providing for aggravating circumstances including but not limited to the age of the survivor, the relationship of the perpetrator and the survivor, the use of threats or violence, the presence of multiple perpetrators and the gravity of long-term mental and physical consequences of the assault.

- Criminalize other non-penetrative forms of sexual assault.

To the Ministry of Social Affairs and Family

- Create or fund the creation of shelters where women and children who survived sexual violence can receive comprehensive support services, including legal assistance, psycho-social counseling and accommodation options, in both urban and rural areas, accessible to all.

- Increase financial support and oversight of existing centers providing direct support services to sexual violence survivors run by civil society organizations to improve their:

- Accommodation capacity, including overnight stay and services; and

- Ability to protect both survivors and support staff from threats of retaliation.

- Develop or fund the development of specific services, including safe housing, to support women and girls who are unwilling or unable to return home or to reside with their extended families as a result of being ostracized as victims of sexual assault, for perceptions of so-called moral transgressions, or risk of harm in the home. Women and girls in safe housing should have freedom to come and go and be provided with assistance to seek educational and employment opportunities.

- Support the development of transition centers and services adapted to the special needs of women and girls coming out of prison.

- Develop awareness-raising campaigns about the various forms of sexual violence. Such campaigns should target the general public, law enforcement, and judicial officials, health professionals, and religious leaders who may influence public opinion. Such campaigns should seek to erode the social stigma surrounding sexual assault and rape survivors, to challenge victim-blaming, and to promote available resources for survivors to seek protection and remedies.

- Adopt national standardized protocols of data collection of sexual violence incidents and complaints in coordination with the Ministries of Health, Justice, Interior and National Office of Statistics at a minimum disaggregated by sex, gender, age (of the survivor and, if known, of the perpetrator), language spoken by the survivor, and type of violence. Better data collection is a step toward developing tailored public policies on preventing and responding to sexual violence.

- Undertake studies into the prevalence of sexual violence against men and boys.

To the Ministry of Health and its National Program on Reproductive Health

- Adopt forensic guidelines on documenting and treating sexual violence in line with the World Health Organization’s (WHO) guidelines, including the standard form on such documentation, prohibiting the use of “virginity tests,” and emphasizing doctors and other health workers’ obligation to provide medical assistance and forensic testing if sought by the survivor, without requiring the survivor to obtain a police referral.

- Support the forensic training of health professionals who can provide both medical treatment and conduct forensic examinations and testing during a single consultation, including doctors, nurses and midwives, to increase survivors’ access to professional evidence collection and increase the reliability of such evidence in court.

- Prioritize the recruitment of female doctors and healthcare professionals to increase access of sexual violence survivors to female practitioners.

- Support the development of sexual violence units in public hospitals and health centers, and make their therapeutic care and forensic testing services available free of charge or affordable to all regardless of means, compliant with WHO guidelines on medico-legal responses to sexual violence, building upon the expertise of the special unit established at the public hospital “Mother and Child” (“Hôpital Mère et Enfant”) in Nouakchott.

To the Ministry of Interior

- Create or fund and require the participation in periodic trainings on gender-responsiveness and sexual violence and other forms of gender-based violence of law enforcement officials, particularly police officers, to avoid re-traumatization of survivors in police responses and address implicit biases in investigative procedures.

- Create or fund and require participation in specific trainings to handle cases of sexual violence against children. The trainings should be required of law enforcement officials, particularly those working in police stations that only take on cases involving children (brigades des mineurs).

- Promulgate written protocols for police that would require, in cases of gender-based violence:

- Carrying out risk assessments, recording the complaint, advising the complainant of her rights, filing an official report, arranging for transport for medical treatment, and providing other protection;

- Ensuring that women complainants have the option to speak and submit their complaint to female officers;

- Ensuring that a social worker be available to assist women who file a complaint with the police;

- Interviewing the parties and witnesses, including children, in separate rooms to ensure there is an opportunity to speak freely; and

- Monitoring and accountability for law enforcement officials who do not abide by such protocols.

- Increase efforts to recruit and promote female police officers and national guards by addressing and eliminating discrimination, direct and indirect in the recruitment process, and conducting significant and ongoing recruitment and professional development campaigns for them.

To the Ministry of Justice

- Create or fund and require participation by prosecutors and judges in periodic trainings on gender-responsiveness and sexual violence and other forms of gender-based violence to reduce re-traumatization of survivors and address implicit biases in prosecutorial practices and court proceedings.

- Create or fund and require participation of Mauritanian prosecutors and judges in specific trainings to handle cases of sexual violence against children.

- Impose an immediate moratorium on prosecuting and detaining individuals for zina and immediately release all individuals currently in detention on zina charges.

- Establish specialized prosecutorial units to investigate cases of sexual and gender-based violence, provide adequate funding and specialized training for prosecutors, in order to develop expertise in this area, increase the number of cases investigated, and improve the efficiency of the investigative process for complainants.

- Ensure that prosecutors and investigative judges urge police officers under their supervision to respond to, investigate, and diligently collect evidence in all cases of gender-based violence.

- Continue to fund and require participation of Mauritanian prosecutors and judges in regular training programs on the international and regional human rights instruments that Mauritania is obliged to enforce and implement domestically, particularly the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women, the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa, and the African Convention on the Rights and Welfare of the Child.

- Ensure that evidentiary documents in court cases such as medical reports which are in a language other than Arabic, which is the official language of the courts, are translated and notarized to minimize translation issues that may arise during the fact-finding phase of court proceedings.

- Ensure that all complainants are given the opportunity to seek compensation from the defendant in the course of a criminal legal action via the mechanism of “partie civile,” and by urging police officers, prosecutors, and judges to inform complainants about their right to seek compensation for the alleged damage endured and provide guidance regarding the procedural steps to follow.

To the Ministry of Islamic Affairs and Fundamental Teachings

- Urge the Ministry of Interior and Ministry of Justice to immediately release all individuals serving indefinite jail time as a result of a conviction for zina.

- Mobilize religious leaders and scholars (ulema) to support awareness-raising campaigns about sexual violence in Mauritania, particularly condemning sexual assault and rape and encouraging survivors to speak out and if desired, to seek judicial accountability.

- Support the adoption of a draft gender-based violence law compliant with international human rights law standards.

To the United Nations, the African Union, and International Donors

- Urge Mauritanian authorities to release individuals detained on zina charges.

- Support the Mauritanian government to conduct research on the scope of the issue of sexual violence and the treatment of survivors by the justice and social welfare systems that would provide the basis for new national action plans and policies.

- Call on the Mauritanian government to prioritize the adoption of a gender-based violence law compliant with Mauritania’s obligations under international law, the repeal of articles 293, 306, and 307 of the Penal Code, and reforms to laws that discriminate against women.

- Support women’s rights and the elimination of sexual violence in Mauritania, through political, technical, and economic support. Priorities under such a commitment should include:

- Stable, long-term assistance for civil society organizations providing direct support services to sexual violence survivors, to enable them to provide accommodation, free legal aid, and psycho-social counseling to sexual violence survivors;

- Support for the government to create “open” shelters throughout the country, providing safe short-, medium-, and long-term housing options and rehabilitation services for women and girls who survived sexual violence, and women and girls transitioning out of prison;

- Creation of a national emergency helpline for survivors of sexual violence to report incidents and seek help;

- Psycho-social services and counseling for women and girls in detention; and

- Large-scale national awareness-raising campaigns advising women and girls about their rights and explaining how any sexual violence survivors can get help.

Methodology

This report is based on interviews conducted by Human Rights Watch researchers during three trips to the capital Nouakchott, and a trip to the southern city of Rosso, on October 17-23, 2017, January 20-February 12, 2018, and April 20-28, 2018. The researchers interviewed women at the women’s prison in Nouakchott on January 20, 2018, with permission granted by the Directorate of Criminal Affairs and Prison (Direction des affaires pénales et de l’administration pénitentiaire) .

Human Rights Watch interviewed 12 girls and 21 women—eight women who recounted the story of a relative below 18, and 13 women who recounted a personal story—who reported enduring one or more incidents of sexual assault. Some of the women were under 18 at the time of the assault that they recounted. The research team conducted all interviews individually, in a safe and private space, with some exceptions. Some interviews of children were conducted in the presence of a parent or an adult relative.

While researchers found it difficult to find survivors of sexual violence willing to share their experience, 33 women and girls aged from 13 to 42, did so willingly. Women and girls who accepted to participate in the research were Haratine (black Moors, i.e. of Arab-Berber descent) or Afro-Mauritanian (Négro-mauritaniennes), from relatively poor backgrounds. The research team identified interviewees thanks to referrals by Mauritanian women’s rights groups operating centers providing direct support services to sexual violence survivors throughout the country.

During the visit of the women’s prison, Human Rights Watch interviewed individually three women who were charged with or convicted of zina and who, at the time of the interview, were either in pre-trial detention or serving a long-term prison sentence. Interviews took place in a private room, in the presence of an interpreter working with the research team, and away from prison guards.

Interviews were conducted in Hassaniya, classical Arabic, Pulaar, Wolof and French, usually with the aid of a woman interpreter. Many of the survivors interviewed courageously shared their experiences, saying they wanted the world to know their stories, but many requested that Human Rights Watch recount it in a manner that fully concealed their identity. For this reason, all names used to identify survivors throughout the report are pseudonyms. We have also omitted locations mentioned in their accounts.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed 23 activists, leaders of nongovernmental organizations (NGO), social workers, lawyers, a psychologist, and journalists affiliated with eight Mauritanian NGOs, including three that operate women’s centers providing direct services to sexual violence survivors, and four international NGOs. The research team also met with both Mauritanian institutional actors and representatives of multilateral organizations, including then Minister of Social Affairs and Family, Ms. Maimouna Mint Taghi, the president of Mauritania’s National Human Rights Commission, Irabiha Abdel Wedoud, and representatives of the United Nations Population Fund’s country office, the United Nations Children’s Fund’s country office, the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, the European Union Delegation office, and embassies and development agencies of France, Germany, Spain, and the United States.

The research team provided no remuneration or other inducement to any of the interviewees. In each case, Human Rights Watch explained to the interviewee the purpose of the interview, how it could be used and distributed, that their participation was voluntary, and discussed the degree of confidentiality and anonymity the interviewee would be most comfortable with and obtained consent to include their experiences. Human Rights Watch advised all interviewees that they could stop or decline to answer questions at any time in the interview and sought to minimize the risk of further traumatization of those interviewees who had experienced physical or sexual abuse.

While the research team limited its interviews to two major cities, the report makes more general observations about national trends based on the field experience of partner civil society organizations with offices in every region (wilaya), analysis of multilateral organizations operating throughout the country, and a review of available case law.

On July 12, 2018, we submitted a letter to various ministries of the Mauritanian government with questions based on our preliminary findings and did not receive any response. The letter is reprinted in the appendix to this report.

I. Background

Mauritania’s ethnic diversity reflects the country’s geographical location, bridging the Maghreb and sub-Saharan West Africa. The population consists of three main ethnic groups, though important cultural distinctions and social hierarchies nuance each. The vast majority across ethnic lines are Sunni Muslim.

The first two of these groups speak the local dialect of Arabic known as Hassaniya. The first group of Hassaniya-speakers are known as “Beidans,” descended from Arabs and Berbers who migrated from the north and east. Beidans dominate the country’s political and economic elite.[2] “Haratines” form the second and larger group of Hassaniya-speakers. They are composed mostly of darker-skinned former slaves and their descendants. The third population group is often referred to as “Afro-Mauritanians” or “Négro-mauritaniens” and is comprised of several ethnic groups whose native tongues are sub-Saharan African languages rather than Arabic.[3] The Halpulaar are by far the most numerous subgroup of Afro-Mauritanians, followed by the Soninké and smaller populations of Wolof and Bambara speakers.

Women’s Rights

In May 2001, Mauritania acceded to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, with a reservation regarding provisions it deems contrary to Islamic law (Sharia) and Mauritania’s Constitution.[4] The same year, Mauritania codified key principles of family law through the adoption of a Personal Status Code.[5] Since its adoption, the Code has been criticized for discriminating against women, especially with respect to equal rights with men to enter into marriage, rights during marriage, and at its dissolution, inheritance, and in the transmission of nationality to one’s offspring (along with the Nationality Code of 1961 which also sets discriminatory criteria in the transmission of nationality).[6]

Mauritania subsequently adopted legal reforms and national strategic plans intended to strengthen women’s rights and eliminate slavery and sexual exploitation.[7] In December 2005, Mauritania acceded to the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa (Maputo Protocol), without reservations.[8] In 2006, the country adopted an Order (ordonnance) reserving 20 percent of seats to women in municipal elections and requiring electoral lists to include a minimum number of women varying depending on the electoral district in legislative elections. [9]

In 2017, Mauritania undertook two steps to align its domestic law with international human rights standards. In October 2017, the National Assembly passed a new law on reproductive health recognizing it as a universal fundamental right, authorizing family planning in public and private hospitals and health centers and prohibiting all forms of sexual violence and abuse.[10] In December 2017, it adopted a new General Code on Children’s Protection, broadening children’s rights protections and strengthening the provisions of the 2005 landmark Order on the Penal Protection of the Child.[11] In early 2016, the executive branch also approved a new draft law on gender-based violence that, if amended to comply with international human rights standards, would significantly improve support services and means of legal recourse available to survivors. The draft law was approved by Mauritania’s Senate in 2016 (an institution that has been dissolved since) but later rejected by the National Assembly and was awaiting a second vote by the same chamber at the time of writing.

Despite legislative and institutional progress achieved over the last two decades, Mauritanian women remain economically, politically, and socially marginalized, with significantly lower literacy rates, professional mobility, and financial security than men.[12]

According to the Mauritanian National Office of Statistics, in 2015, 27 percent of Mauritanian women said that a husband has the right to be physically violent with his spouse(s) if she goes out without telling him, if she neglects children, if they argue, if she refuses to have sexual relations with her husband, or if she burns the meal.[13]

While recent statistics on the incidence of gender-based violence are not publicly available, Mauritanian NGOs and institutional actors report that it is widespread. According to a 2017 report from the National Human Rights Commission, several common factors hinder the elimination of violence against women in the country, including the “inadequacy of existing implementation measures […] such as awareness-raising campaigns, training programs for law enforcement officials and the lack of financial and human resources of mandated institutions; […] women’s poverty and low literacy rates, the lack of knowledge of their right[s], their fear to bring cases before courts, and their lack of access to information.”[14]

In 2015, 28 percent of women and girls aged 15 to 19 were married (versus 0.8 percent of males of the same age), with rates of early and child marriage twice as high in rural than in urban areas. In addition, 16 percent of girls and women aged 15 to 49 years-old were married before the age of 15.[15] While the Personal Status Code provides that men and women must be 18 or older to consent to marry,[16] the Code also allows the legal guardian of an “incapable” girl (broadly interpreted as orphan girls or girls without legal guardians) to marry her “if he identifies an obvious interest” to do so.[17] The Code also provides that “the silence of any young girl means consent to marry.”[18] Further, the General Code of Children’s Protection provides sentences from five to 10 years of prison and a fine for a guardian who marries a child “in the exclusive interest of the guardian,” without defining what that phrase means.[19]

In 2015, two thirds of women and girls aged 15 to 49 reported having gone through a form of female genital mutilation (FGM) or excision in the past, with significantly higher rates in rural than urban areas (79 percent compared to 55 percent). Of women with daughters, more than half reported that at least one of their daughters aged 14 or under had gone through a form of FGM or excision.

In 2017, Mauritania formally and unconditionally criminalized the practice of FGM in the newly adopted General Code of Children’s Protection and law on reproductive health.[20] For many years, this practice could only lead to criminal sanctions if it led to health complications.[21]

Over the last few years, the government has attempted to address the issue more proactively by adopting national strategies, establishing national and regional councils on gender-based violence and FGM with the aim to progressively eradicate this harmful practice. The Ministry of Social Affairs and Family and its partners prompted doctors to adopt a national declaration condemning the adverse effects of FGM, and Islamic scholars issued a “fatwa” (a religious edict that provides a non-binding legal interpretation of Sharia) declaring that the practice lacked a religious basis.[22]

Sexual abuse and violence in the context of domestic relations remains taboo and a blind spot in the studies and activities coordinated by institutional actors addressing gender-based violence, according to both the National Human Rights Commission and Mauritanian women’s rights groups.[23]

Overall, the lack of gender-sensitive indicators and tools for data collection of sexual violence creates opacity about the number of cases authorities ought to respond to and about the scale of the phenomenon, and thus hinders the design of adequate public policies.[24] A representative of the Spanish NGO Médicos del Mundo told Human Rights Watch that, “until recently, Mauritania’s Ministry of Health tallied sexual violence incidents under the category of accidents on public thoroughfares (accidents de la voie publique) or victims of intentional assault and battery (victimes de coups et blessures volontaires).”[25]

Similarly, a representative of the United Nations Population Fund’s Mauritania country office told Human Rights Watch that “only civil society organizations report data on this issue. And their data is alarming.”[26]

In 2017, the Mauritanian NGO Association of Women Heads of Family (Association des Femmes Chefs de Famille) reported intervening in 428 cases of rape, 128 child marriages, and 1,623 domestic conflicts, some including sexual violence. The same year, the Mauritanian Association for the Health of the Mother and the Child reported supporting 260 women, girls, and boys survivors of sexual assault nationally and 40 women and girls who endured domestic violence.[27]

II. Barriers to Redress

|

Rouhiya Rouhiya was 5-months pregnant from her father, for the second time, when she shared her story with Human Rights Watch. She was 17 but showed a strikingly composed demeanor. “My father treated me like his wife. I never told anyone, but I wanted to flee. […] When I spoke about it with my mother, she told me not to tell anyone. My father threatened to kill me. He does the same thing to my [toddler] sister. I tried to flee with a 23-year old young man who wanted to marry me. I met him in the street.” Rouhiya said that in July 2016, she joined the young man at his house, where he locked her up, drugged her and, along with three other men, repeatedly gang-raped her for two weeks. Rouhiya’s parents called the police, who broke into the man’s house and found her traumatized. Her father took her to a police station the next day to bring charges against the four men. “The next day, we went to the prosecutors’ office. […] He asked me questions about my experience, while the four men were with me in the same office. The prosecutor asked me why I had left with this friend. I explained that I was scared of my father—but I did not admit that he had been raping me.” While the four men were placed in pre-trial detention, the police also arrested Rouhiya and prosecuted her for having engaged in sexual relations outside marriage (zina). She spent a few weeks at a juvenile justice facility, before the police transferred her to the national women’s prison in Nouakchott. “I asked them why [are you arresting me]? What did I do? They told me to keep quiet and not to ask questions,” Rouhiya recalled. In the hours following her arrival at the prison, Rouhiya fainted in her cell. Within 24 hours, a women’s rights organization obtained her release on health grounds. Outside prison, women’s rights organizations assisted Rouhiya but none had the capacity to shelter her over the medium term. Rouhiya had no choice but to return to her abusive home. She returned to the center in 2017 run by the organization that had facilitated her release from prison, when she was six months pregnant from her father. “I gave birth,” she said. “But the child was stillborn.” |

Institutional and Social Obstacles to Redress

Stigma and Social Exclusion of Sexual Violence Survivors

“Culturally, people prefer not to raise [incidents of sexual assault]. It is a shame upon the family. […] Socially, it is frowned upon. The social reaction in the environment from which the survivor comes is difficult.”[28]

— Khadijetou Cheikh Ouedrago, Gender Specialist, UNFPA country office

Social pressure and stigma, both in the home and community, can be the first obstacles for survivors in Mauritania who wish to file a police report. Five women who said they had been raped, four of whom were under 18 at the time of the incident, told Human Rights Watch that they did not speak about the rape until their pregnancy became physically noticeable. Mariama, 20, who said a taxi driver raped her when she was 17, recalled:

When I was eight months pregnant, my mother realized it, and asked me how it happened. That’s when I told her about the rape. My father got very angry, he took me to the police station, and told the policemen that his daughter should be locked up because she had slept with a man, that he didn’t want her anymore in his house. I spent a night in police custody.[29]

Mauritania’s NHRC has found that the taboo surrounding sexual violence “doubles survivors’ victimization.” [30] According to a 2017 report on women’s rights in Mauritania, the NHRC observed that “survivors are rejected by society, their families do not support them and the judicial path to regain their rights is not easy.”[31]

The Mauritanian lawyers who Human Rights Watch interviewed all said that social stigma inhibits survivors’ willingness to seek help and to pursue legal action. Lawyer Jemal Abbad, who represents survivors of sexual assault supported by the Mauritanian women’s rights NGO Association of Women Heads of Family, explained: “Sexual crimes are taboo […] in Mauritanian society. There are parents who refuse to talk about it. They think it will harm the family’s honor.”[32]

Lawyer Ahmed Ould Bezeid El Mamy, from the same group, also noted that such pressure affects women from different ethnic groups and socio-economic backgrounds in different ways. According to Bezeid, sexual violence is particularly taboo among wealthy, prominent families, explaining that women who have been raped often travel to Senegal to give birth discreetly when they can afford it. He also observed that early marriages are a common way to “save the honor of the family.”[33]

Sexual assault, particularly for single women and girls, scars them socially in a way that limits their acceptance in their community and makes their marital prospects more difficult. Marie-Charlotte Bisson, head of the Swiss NGO Terre des Hommes-Lausanne’s Mauritania country office, has observed that “social exclusion and stigma associated with sexual assault often leads the survivors’ whole family to move to a different neighborhood.”[34]

Like in other countries, value is still placed on the myth that an intact hymen indicates virginity. Fatimata M’Baye, the first female lawyer in Mauritania who founded and heads the Mauritanian Human Rights Association, said: “It is essential to understand the social assessment of the hymen. Our patriarchal society requires women to be ‘intact’ when they marry. If a woman is not, she must have been with someone else.”[35]

|

Overview of the Criminal Procedure

To set a legal action in motion, a survivor has to report the incident to the police. Police officers must notify the state prosecutor of the complaint, undertake a preliminary investigation, and provide the state prosecutor with a police report and preliminary case file, including the survivor’s medical certificate.[36] In criminal cases, police officers operate under the supervision and follow the instructions either of a state prosecutor or an investigative judge. Police officers can arrest suspects and place individuals against whom they have “serious and consistent” evidence in police custody for 48 hours, a period that can be renewed once with the state prosecutor’s authorization.[37] The state prosecutor determines whether to open a criminal investigation and to refer the case to an investigative judge, who will oversee the fact-finding phase leading to trial, or decide to drop the case (ordonnance de non-lieu).[38] If the state prosecutor decides to drop the case, they must notify the complainant within eight days of the decision.[39] Before trial, the investigative judge can decide to grant defendants provisional liberty under judicial control or place them in pre-trial detention.[40] Investigation and sentencing procedures can be expedited if the defendant is deemed to have been caught in the act (flagrant délit).[41] If the investigative judge finds that there is enough evidence for a case to go to trial, they refer it to the criminal court that has jurisdiction to rule on the case.[42] |

Poor Police Responses and Prosecutorial Practices

When women and girls overcome societal pressure and come forward to report incidents of sexual assault to the authorities, they often face additional obstacles created by the way police handle complaints and by how state prosecutors lead investigations of sexual violence cases.

Reporting the assault to the police is the first step survivors must take if they are to seek institutional protection and judicial accountability. Twenty-three out of 25 interviewees who were children at the time of their assault said they reported the incident to the police. However, only 4 out of 8 women who were adults at the time of their assault reported it to the police. The Mauritanian Association for the Health of the Mother and Child, a women’s rights NGO operating centers providing direct services to sexual violence survivors throughout the country, said that women tend not to report sexual violence incidents to the police because of stigma and risk of prosecution for zina. As a policy, the NGO advises women not to report sexual assaults incidents to the police to avoid the risk for survivors that they themselves be prosecuted.

No standardized protocols exist at the regional or national levels for police officers to respond to sexual violence cases. After hearing and taking notes of the complainant’s account, a police officer can issue a referral for a forensic medical examination by a doctor at a public hospital or health center. In public health facilities, obstetrician-gynecologists usually perform medical examinations and forensic testing simultaneously and issue medical certificates directly sent to the police to add to the complainant’s case file.

In the capital, Nouakchott, three police stations exclusively take on cases involving children (brigades des mineurs),[43] as either accused or complainant. These police stations accommodate on-site social workers mostly employed by civil society organizations, but not all stations provide them a private office space.[44] The social workers also periodically visit police stations without a juvenile unit to identify new cases of sexual violence and can help survivors navigate interactions with their family and third parties, take legal action, and access medical and psychological support. Social workers Human Rights Watch spoke to were critical of the constraints of their role in police stations. Since most social workers do not have a formal accreditation and are allowed into police stations only informally, they can be required to leave the premises at any time.

Social workers usually attend children’s police hearings alongside a lawyer and can assist both children and adults in undertaking the various steps of medical and legal procedures. The director of a women’s rights center providing direct services to sexual violence survivors in Nouakchott told Human Rights Watch: “When the social worker receives a new case at the police station, she distinguishes between: (1) women whom we advise not to press charges because of the risk to be prosecuted for zina and (2) minors whom we advise to seek legal action.”[45]

In many of the interviews Human Rights Watch conducted, when survivors were above 18 or had a pre-existing relationship with the perpetrator, it appears police officers refused to investigate incidents of sexual violence. Khouloud who said she had become pregnant from rape by her former husband, told Human Rights Watch: “When I approached police officers, they told me that it was none of their business, that it was not part of their job, and that I should go speak to NGOs.”[46]

According to a UNFPA representative, “Much more needs to be done in order to create special procedures [for sexual assault cases] in police stations. Most police stations are full of men.”[47] All women and girls interviewed who said they reported to the police that they had been assaulted mentioned that they found themselves interacting mostly with male officers and that the police officers on duty never offered them the option to speak to a female officer.

They also went through in-take procedures that did not respect their privacy and confidentiality: officers usually asked questions in open spaces in the presence of several colleagues and family members. 15-year-old Fatimata, who reported being raped by a co-tenant of the apartment where her family lives, recounted: “At the police station, there were a lot of police officers in the room [where I was interviewed], my father, my uncle, my friend Aicha [who was assaulted by the same man], her father, and her uncle. A few women officers were present, but men were the only ones asking questions.”[48]

Survivors told Human Rights Watch that police officers asked them to narrate the incident. Officers then incorporate the survivor’s account into a police report that combines police officers’ observations, statements of the complainant, and police actions taken in relation to the incident reported.[49] Police officers send the report to the state prosecutor who can call the complainant and the alleged perpetrator for a hearing. Depending on the circumstances of the assault, the degree of physical violence involved, the survivor’s age and relationship with the alleged perpetrator, some police officers and state prosecutors seem to offer their own moral assessment of the incident reported. Human Rights Watch met Zahra, a woman in her twenties, and her 7-month-old daughter, Sakina. In 2016, Zahra said her neighbor—who lived in the same informal settlement as her and her relatives—raped her, threatening to kill her with a knife. “He used to woo me, he had told me he would marry me one day,” Zahra said.[50] One night he got home late from work, while Zahra and her sister-in-law were home alone. “He asked me to bring him water, but then he put his hand on my mouth, pulled out a knife, and closed the door. I wanted to scream but he threatened me with his knife and told me that if I screamed, he would cut my throat.” Zahra became pregnant from the rape and reported the assault to the police six months into her pregnancy. While the perpetrator was placed in pre-trial detention, she was also charged with zina and placed under judicial control. A social worker from the Association of Women Heads of Family who assisted Zahra throughout the course of the legal procedure told Human Rights Watch:

The hearing before the state prosecutor usually lasts an hour. The prosecutor asked Zahra: “If you did not consent, why didn’t you tell your parents? He kept provoking her with those kinds of questions. […] He asked her “Did you know him?” When Zahra opened up, he responded, “That’s not true. All the things you are saying are lies, you did this willingly.” He was asking leading questions but only took note of her answers.[51]

Limited Access to Therapeutic Care and Inadequacies of Forensic Testing

Police Referrals

Survivors, social workers, and NGO leaders interviewed reported that doctors practicing in public hospitals and health centers, who perform both medical examinations and forensic testing, will often only examine survivors in the immediate aftermath of an assault if there is a formal written police referral (réquisition) or if an emergency medical intervention is required.[52] 10-year old Faroudja was raped in an abandoned house by a relative a few weeks before speaking to Human Rights Watch. The same night, her mother took her to a public hospital in Nouakchott where a doctor informed her that he could not examine her unless she obtained a police referral.[53] Requiring such a referral prevents survivors who are not willing to report to the police from accessing immediate medical care and collection of forensic evidence in a timely fashion.

Forensic Examinations

There is only one practicing forensic doctor in Mauritania and forensic medicine is not regulated by law.[54] The lack of forensic expertise is exacerbated by the absence of specialized forensic doctors and established uniform protocols that doctors should follow when collecting forensic evidence. Conventional obstetrician-gynecologists end up performing non-standardized forensic examinations of sexual violence survivors. The state does not permit midwives to perform forensic examinations, despite calls for them to be allowed to do so by nongovernmental organizations because there are more female midwives than female doctors. According to the coordinator of the Spanish NGO Médicos del Mundo in Mauritania, in most public hospitals and health centers, the doctor who examines and performs forensic testing on sexual violence survivors is likely to be a man.[55]

Moreover, patients often have to wait hours to see a doctor after an assault due to the general shortage of doctors in Mauritania. In 2014, the Ministry of Health estimated that only 239 family practitioners (that is one per 14,729 residents) and 329 specialists (that is one per 9,301 residents) were available nationally to provide care to a population of some 3.5 million.[56] To attain high coverage of skilled birth attendance (80 percent), the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that an average of 2.3 skilled health workers (doctors, nurses, and midwives) per 1,000 population is necessary, far above Mauritania’s current level.[57] “The victim can wait a whole day. The chief doctor oversees surgeries, birth deliveries... If the victim comes back in the afternoon, she has often already taken a shower or has urinated,” thus weakening the forensic evidence, said Aminetou Mint Ely, president of the Association of Women Heads of Family, which runs centers providing support to sexual assault survivors throughout the country.[58]

Fear of retaliation also dissuades doctors from performing forensic examinations and issuing medical reports that may be used to prosecute alleged perpetrators. Doctor Amadou Kane, coordinator for Médicos del Mundo, told Human Rights Watch, “Health professionals do not want to interfere with [legal] action when they risk being called to testify. Being identified as the doctor who examined a victim engaged in litigation creates security risks. […] Certain health professionals are worried that they may cause the perpetrator’s incarceration” and fear reprisals by them or their relatives.

Survivors interviewed who had seen a doctor in the immediate aftermath of the assault were confused about the medical examination they went through. Both children and adults were alone when they met the doctor who simultaneously conducted a forensic examination and provided medical treatment. Some patients had only limited understanding of the tests performed. “I don’t know what kind of exams the doctor performed. The doctor did not explain to me what she was doing,” said 17-year-old Rouhiya, whose story is relayed above.[59]

Most first-response medical examinations involve the collection of vaginal swabs, semen analysis, and testing for sexually transmitted infections (STI).[60] While doctors often prescribe emergency birth-control pills if they find traces of vaginal penetration, they rarely prescribe post exposure prophylaxis treatment for HIV and other STIs.[61] DNA tests are not available in the country.[62] Meanwhile, “the state of the women’s hymen is the first thing families are worried about,” explained Amparo Fernández del Río, coordinator of the Spanish NGO Médicos del Mundo’s Mauritania country office. Human Rights Watch reviewed several medical certificates prepared by doctors who forensically examined victims of sexual assault. They were all handwritten and brief. Each answered three points: whether or not the doctor observed traces of physical violence on the patient, the type of STI tests performed, and the state of the survivor’s hymen.

The current practices are not in line with the World Health Organization’s guidelines on forensic reporting on sexual violence. These guidelines provide that, among other things, “treating a victim of sexual assault with respect and compassion throughout the examination will aid her recovery,” and require that “all parts of the examination should be explained in advance; during the examination, patients should be informed when and where touching will occur and should be given ample opportunity to ask questions. The patient’s wishes must be upheld at all times.” They also provide that ideally the same practitioner should provide the forensic examination and health services at the same visit, which is currently the case in Mauritania, and that authorities should ensure “that female nurses or physicians are available whenever possible. If necessary, efforts to recruit female examiners should be made a priority.”[63] The WHO has stressed similar considerations for children and adolescents who have been sexually abused, including where possible, they should be offered the choice of a male or female examiner and should be examined by someone trained.[64]

Moreover, the WHO has said that “there is no place for virginity testing; it has no scientific validity and is humiliating for the individual,” noting that “the hymen is a poor marker of penetrative sexual activity or virginity in post pubertal girls.”[65] It has called for a thorough physical examination of sexual assault survivors noting that not all sexual assault survivors will have genital injuries that are visible, including of the hymen, and that this does not disprove their claim.[66]

While judicial investigations, court proceedings and decisions are rendered in Arabic, medical records included in a complainant’s case are written in French, which can lead to inaccurate translation in the course of legal proceedings, according to lawyers Human Rights Watch consulted. Lawyer M’Baye told Human Rights Watch:

I once observed a prosecutor who speaks Arabic review a medical certificate drafted in French including the following mentions “touching, introduction of an object in the complainant’s vagina, blood on the inner lips.” His interpreter explained to him that the medical certificate said, “minor caressing.”[67]

Medical Treatment for Sexual Violence Survivors, Criminalization of Abortion, and Related Costs

Mauritania’s 2017 law on reproductive health declared that the right to reproductive health is a “universal fundamental right, guaranteed to all, at any stage of life.”[68] However, the law bans abortion, punishing those who provide and receive the procedure, except where the pregnancy poses a “threat to the mother’s life.”[69] The law prohibits abortion even in cases of sexual violence. The WHO has shown that restrictive laws, stigma, and poor availability of services can lead to women and girls with unwanted pregnancies to resort to unsafe abortion, sometimes forcibly.[70] In cases where sexual violence results in a pregnancy that a woman wishes to terminate, the WHO calls for women to be referred to legal abortion services.[71]

29-year-old Khouloud, who was raped by her former husband, told Human Rights Watch: “When he learned that he had gotten me pregnant, he brought two pills [for abortion]. He put one in my mouth, another one in my vagina. After that, I went to the bathroom and blood came out of my body, I was dizzy. When I tried to report the incident to police officers, they told me it was none of their business. They told me: ‘We can speak to him and tell him to provide for your kids but for your pregnancy, you should go speak to NGOs.’”[72]

Medical care in the aftermath of an assault, including emergency interventions and forensic examinations, carry a cost that none of the survivors Human Rights Watch spoke to could afford. Some families could not even afford the cost of transportation to medical facilities.[73] All medical costs of survivors interviewed were covered by social workers who said they sometimes had to pay survivors’ medical expenses out of their own pockets when they exceeded the stipend allocated by the NGO they work for.

In June 2017, the first and only sexual violence unit at a Mauritanian public hospital was inaugurated, at the Mother and Child Hospital in Nouakchott (Unité Spéciale de Prise en Charge). Within its first year of operations, the unit supported 184 survivors of sexual violence in Nouakchott.[74] It provides obstetrical and gynecological consultations, emergency surgical interventions, and STI screenings free of charge to survivors, regardless of whether or not the patient obtained a police referral, with an automatic follow-up appointment a month after the first consultation. Since May 2018, the unit has also been offering free psychological counseling to all new patients through the assistance of a psychologist on staff at the hospital, supported by the Ministry of Health. The hospital staff and doctors have received training on best practices to handle cases of sexual violence and have received protocols on how to record new sexual violence incidents and how to perform forensic medical examinations in a way that overall complies with WHO guidelines.[75] Depending on the complainant’s place of residence in Nouakchott, police referrals do not systematically direct survivors to this unit to complete a forensic examination.

Many of the survivors interviewed reported experiencing emotional reactions such as sobbing, shame, fear, and mutism weeks after the assault. According to the WHO, such emotions are direct psychological consequences of sexual assault, although they vary from person to person.[76] Beyond the initial psychological screening offered by some women’s rights groups, survivors interviewed received no psychological support following their assault. In 2016, the NGO Médicos del Mundo counted only four practicing psychiatrists and fifteen psychologists in Mauritania, most of them working for public hospitals in the Nouakchott area.[77]

Legal Obstacles and Criminalization of Survivors

Weak Domestic Legal Standards

The Penal Code criminalizes rape but does not define it. Under article 309, unmarried defendants convicted of rape risk a sentence of hadd (prescribed by God) and flogging, while married defendants must be sentenced to death.[78]

Rape is the only form of sexual violence explicitly prohibited under the Penal Code and the only basis for legal recourse by adult survivors of sexual assault.

New Law on Reproductive Health

Mauritania’s 2017 law on reproductive health prohibits “all forms of sexual violence and abuse, particularly affecting children and teenagers.” However, it does not define sexual violence or abuse or set out penalties, referring instead to articles 309 (prohibiting rape) and 310 (providing for aggravating circumstances for a rape offense) of the Penal Code. [79] Further, it reaffirms the ban on abortion, with no exception for pregnancies resulting from sexual assault (see above).[80]

Special Substantive and Procedural Protections of Children

Article 24 of the 2005 Order on the Penal Protection of the Child provides specific rights and protections to children under criminal law. The Order criminalizes rape perpetrated against a child, defined as a person under the age of 18 under Mauritanian law,[81] but again does not define rape, defaulting to provisions of the Penal Code (articles 309 and 310).[82] It punishes rape committed against a child with hadd sentences (prescribed offenses under Islamic Law) or five to 10 years’ imprisonment.[83] Articles 25 and 26 of the Order also criminalize sexual harassment of a child and “sexual assaults other than rape” against children and provides from two to four years’ imprisonment and a fine without defining the offense of sexual assault.[84] Article 26, section 2 also provides that any form of sexual touching performed on a child amounts to pedophilia and must be punished by a five-year prison sentence.

General Code of Children’s Protection

Mauritania’s 2017 General Code on Children’s Protection expanded the criminalization of sexual violence against children by criminalizing any sexual abuse perpetrated against a child. The new law defines sexual abuse of a child as “the child’s submission to sexual contacts by a person who has a relationship of authority, trust or dependence over the child.”[85] Under the Code, touching or inciting the child to touch oneself, him or herself, or a third party directly or indirectly with a body part or sexual object amounts to “sexual contact.”[86]

Further, the Code formalizes the duty of any person, including individuals under a professional duty of confidentiality, to report to local authorities “any threat to a child’s health, development, physical or moral integrity.”[87]

The Code also provides that in the absence of specific juvenile detention centers, children must be separated and isolated from adults in detention facilities.[88]

Moral Crimes and Criminalization of Consensual Sexual Conduct

Article 306 of the Penal Code prohibits offenses to public decency and Islamic morals. The 2018 amended version of article 306 also prohibits violations of God’s prohibitions. Article 307 criminalizes consensual sexual relations outside marriage. Both provisions, lawyers said, have been used to prosecute survivors of sexual violence and have dissuaded other survivors from reporting their assault.

Article 306(1) is a catch-all provision sanctioning “any person who would commit an offense to public decency or Islamic morals, or violate one of God’s prohibitions or help to violate them.”[89] An offender risks three months to two years of prison and a fine.

Article 307 criminalizes zina, commonly defined as consensual sexual relations between a man and a woman, outside marriage. Under Mauritania’s Penal Code, the crime of zina applies only to an “adult Muslim of either sex” [emphasis added]. While the term adult suggests that the offense only applies to individuals who are 18 and above, Human Rights Watch has documented cases where children were charged with zina. Article 307 specifies that zina can be established by the testimony of four witnesses, or by confession of the defendant. If the defendant is a woman, pregnancy suffices to establish zina.[90] If the defendant is single, they risk a sentence of a hundred lashes, to be carried out publicly, and one year in prison. But if the defendant is married, they may be sentenced to death by stoning (Rajoum).

Article 308 prohibits homosexual conduct between Muslim adults and punishes it with death for males.[91]

Mauritanian authorities do not presently carry out death sentences or corporal punishments provided by Islamic law (Sharia). A de facto moratorium on executions has been in effect since the 1980s.

Restrictive Interpretation and Application of Existing Laws

Four lawyers told Human Rights Watch that judges tend to apply a narrow definition of rape. For adult survivors, “they only look for evidence of physical brutality,” said lawyer Bezeid.

Consent is the factor that distinguishes the offense of rape and zina (sexual relations outside marriage).[92] However the notion of consent is not clearly defined under Mauritanian law. According to lawyer Bezeid, courts find it difficult to apply this distinction, which explains why “judges often fall back on article 306, a catch-all provision that punishes ‘offenses to public decency and Islamic morals,’ to avoid applying article 307 [zina] and article 309 [rape]. The issue is that the law is unclear, both in relation to children and adult victims. [Provisions] only mention the sanction, but don’t provide a definition.”[93] Applying article 306 allows judges to punish extramarital sexual behavior without having to address the question of whether or not the act was consensual—an element that often requires weighing the words of the complainant against those of the defendant.[94]

According to lawyer El Moustapha, when a girl reaches puberty, judges often take the position that she can consent to sex with an adult man.[95]

According to lawyer M’Baye, “virginity tests are automatic in forensic exams performed in rape cases, and rape is usually only recognized when a girl’s hymen broke as a result of the assault.” This is problematic given that the status of the hymen is not a definitive indicator of virginity or sexual assault (see above section on forensic examinations). In the few court cases dealing with sexual assault that Human Rights Watch reviewed, the written judgment did not explicitly refer to what evidence in the case record the judge relied upon to decide whether or not rape had occurred.

Most children interviewed who had taken legal action reported that when identified by the authorities, the perpetrator had been placed in pre-trial detention; some were convicted of rape and sentenced to jail time. Human Rights Watch was unable to access court records and case law to assess the average length of prison terms of convicted rapists.

The UN Office on Drugs and Crime has recommended ensuring that sentencing policies on violence against women should take into consideration, among other factors, holding offenders accountable for their acts and denouncing and deterring violence against women. It recommends that courts should hand down punishments that are commensurate with the severity of the offense and the impact on victims and their family and help to stop violent behavior. In addition, it also calls for states to provide victims with the “right to seek restitution from the offender or compensation from the State,” and that in assessing the victim’s actual damages and costs incurred as a result of the crime, states should consider “assessing physical and mental damage; lost opportunities, including employment, education and social benefits; material and moral damages; measures of rehabilitation, including medical and psychological case, as well as legal and social services.”[96]

According to lawyers Human Rights Watch interviewed, Mauritanian judges seldom seem to go beyond imprisonment. “Compensation is never ordered. There’s no prejudice. For them, [rape] is a crime but they’ve never considered that the damage can be quantified. I’ve never seen a rape case where a [defendant] was sentenced to pay damages to the person who was harmed, I’ve only seen sentences depriving the defendant of liberty,” Bezeid El Mamy said. [97]

While domestic law offers complainants the ability to claim compensation in the course of a criminal case for the damage they endured (partie civile),[98] none of the survivors we interviewed received monetary or material compensation either from the state or from a convicted perpetrator for the harm they suffered. Human Rights Watch was nonetheless able to review one court decision from 2012 involving a sexual assault perpetrated by a man against a girl where a children’s court convicted the defendant to a two-year prison sentence and granted monetary compensation to be paid by the perpetrator to the family for the psychological damage endured by their child and to cover the costs of care incurred in the aftermath of the assault.[99]

Evidentiary Issues Limiting a Complainant’s Case in Court

There’s an evidence issue. DNA tests are not available. If a victim of sexual violence accuses someone, she will not be able to prove it in a court. Any [defense] lawyer would advise their client to deny [the facts], which in turn can become evidence against the victim [herself].

— Aichetou Salma El Moustapha, lawyer for the Mauritanian Association for the Health of the Mother and the Child

Although DNA testing cannot solve all evidentiary and consent issues in sexual assault cases, survivors and social workers interviewed criticized its unavailability in Mauritania. In cases where forensic evidence is available, if the survivor knows or can easily identify the alleged perpetrator, DNA testing could provide scientific evidence to support the complainant’s statement.

In addition, the lack of protocol on collection of forensic evidence and its use in court use gives judges broad discretion to interpret or disregard medical records during criminal trials. [100]

Limitations of Legal Assistance and Resort to Alternative Dispute Resolution

|

Khouloud

29-year old Khouloud was born in Mauritania but grew up in Senegal, where she went to school until her last year of primary school. She and her two toddlers live at her sister’s home in Nouakchott. When she spoke to Human Rights Watch, Khouloud was pregnant with her third child after her former husband had raped her. Her fatigue was tangible. “I’m worried about my children, who are sick sometimes and who I cannot feed, and about my current pregnancy.” Seven months into her pregnancy, she came to the conclusion that reporting her former husband to the police would lead nowhere. Khouloud and he were married for several years and had two children before he suddenly left the family and filed for divorce. Khouloud and her children soon fell into poverty. Her relationship with her former husband deteriorated and he became abusive: When I called him to inform him that children were sick or to ask for child support, he told me that he wouldn’t give me anything. One day he came back and told me he wanted to marry me again and I said, “No, you did not take care of us.” When I refused, he raped me. When he learned that he had gotten me pregnant, he brought two pills [for abortion]. He put one in my mouth, another one in my vagina. […] When I tried to report the incident to police officers, they told me it was none of their business, that it was not part of their job and that I should go speak to NGOs. Khouloud decided to report the incident to a center providing direct support services to sexual violence survivors in Nouakchott, hopeful that they could help her purchase a paternity test: They told me that paternity tests are expensive and that they only provide them in Europe. They told me that [my former husband] denied the pregnancy and that it would be in my best interest not to speak about the incident to a judge. Otherwise, they would accuse me of zina and lock me up.[101] Social workers dissuaded Khouloud from taking legal action against her former husband. Instead, they attempted to mediate the dispute by securing an out-of-court settlement (conciliation) in which her former husband committed to pay her child support monthly. The center’s lawyer had the capacity to pursue legal action but did not do so in order to protect Khouloud. She believed there was no likelihood of legal action succeeding: “Our lawyer stopped us from pressing charges because Khouloud risked being detained for zina,” explained Amadou Sy, social worker for the center of the Mauritanian Association for the Health of the Mother and the Child who oversaw Khouloud’s settlement. |

In 2015, Mauritania adopted a law institutionalizing “judicial aid,” for indigent complainants and defendants in both civil and criminal matters. [102] In theory, eligible parties may receive financial assistance to cover all costs associated with one ongoing case before a court of first degree or on appeal, including lawyers’ fees and translation fees when required.[103]

None of the survivors Human Rights Watch interviewed could afford to hire a lawyer and none benefited from the newly adopted judicial aid program despite their apparent eligibility. A small number were able to secure legal representation through the assistance of a center providing direct services to sexual violence survivors. Women’s rights groups interviewed reported bearing most of the costs of legal action of the survivors they support.

Social stigma, the cost of legal action, the unlikelihood of court-ordered compensation, the risk of prosecution for zina, and financial precarity are all factors that push numerous families to favor out-of-court settlements (conciliation or arrangement) over seeking justice in criminal courts. Mint Ely told Human Rights Watch: “Poor people submit to the pressure [of settlement offers]. Given their financial insecurity they favor monetary compensation.”[104]

If the defendant is over 18, the state prosecutor has to oversee the settlement between the parties and a judge must certify the settlement agreement.[105] If the defendant is under 18, the settlement agreement must be in writing, a representative of child protection services must review it, and a judge must approve it.[106]

According to one social worker, “police officers suggest settlements to perpetrators in order to get a cut for themselves, through under-the-table arrangements. They take advantage of any instance when social workers are absent to push for settlements.”[107]

Prosecution of Women and Girls for Zina

Zina offenses are applied in a way that discriminates on the basis of sex because pregnancy serves as “evidence” of the offense. Men can deny the act of zina, whereas women are less able to do so if they are found to have miscarried or are pregnant. Moreover, hospital staff members can report women who have miscarried or are pregnant outside of marriage to the police.

The UN Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women—the committee responsible for monitoring and reporting on CEDAW (the CEDAW Committee)— and the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child—the committee of experts responsible for monitoring and reporting on the CRC (the CRC Committee)—have both expressed concerns about the lack of definition of rape in Mauritanian law, and the criminalization of consensual sexual relations.[108]

Here, the problem is the conflation of rape and zina, and the conflation of other forms of sexual assault and offenses to public decency.

—Zeinabou Taleb Moussa, President of the Mauritanian Association for the Health of the Mother and the Child

Community organizers, activists, social workers, and lawyers told Human Rights Watch that advocacy efforts conducted over the last two decades have reduced, but not eliminated the convictions for zina or offenses to public indecency of girls and women who claim to have been raped or assaulted sexually.

On February 6, 2018, Human Rights Watch met with then Minister of Social Affairs and Family, Maimouna Mint Taghi, who stated that “There was a time when any woman who reported a rape [incident] was incarcerated for zina along with the perpetrator. Today, no civil society organization can pretend that judges requalify rape as zina. All rape cases reported are prosecuted as such.”[109]

By contrast, Human Rights Watch interviewed both girls and women prosecuted, convicted and imprisoned for zina, a number of whom reported being raped. While zina charges apply to both men and women, recent cases we documented signal that the prospect of zina charges can deter women and girls survivors of sexual violence who seek judicial accountability from reporting. [110]

Human Rights Watch interviewed two girls who said they were raped and who were prosecuted for zina. 17-year old Rouhiya reported being gang-raped at the age of 15 and prosecuted for zina after reporting the assault to the police. She spent some time at a juvenile justice center before being transferred to the women’s prison in Nouakchott, despite the requirements that children remain in separate facilities than adult convicts when separate facilities exist to accommodate them.[111] Because of her critical health condition, Rouhiya was provisionally released from the women’s prison within 24 hours. At the time of writing, social workers supporting her were unsure what the next steps in her case would be.

In another case, 16-year old Zeina traveled to Mauritania from Mali at the age of 14 in the hands of sexual traffickers. She said she was repeatedly raped at the age of 15 by a man with whom she had sought refuge after escaping from the traffickers who brought her to Mauritania. Zeina became pregnant, was prosecuted for zina after giving birth and placed under judicial control. She was required to check in weekly at a police station when she spoke to Human Rights Watch.[112]