Summary

On April 9, 2018, Bangladesh listed its new Digital Security Bill in parliament, which was then sent to a parliamentary standing committee for review. The proposed law is in part intended to replace section 57 of the Information and Communication Technology Act (ICT Act) 2006, which has been widely criticized for restricting freedom of expression and has resulted in scores of arrests since 2013. However, the current draft of the Bill replicates, and even enhances, existing strictures of the ICT Act. This report documents abuses under section 57 of the ICT Act to warn that any new law should protect rights, not be used to crack down on critics.

For instance, exactly a year ago, Monirul Islam, a rubber plantation worker in Srimongol, southern Bangladesh, experienced an unwelcomed surprise. He was arrested on April 13, 2017, accused of defaming the country’s prime minister and harming the image of Bangladesh. His crime: he had “liked” and then “shared" a Facebook post, something social media users around the world do every day. The post, allegedly from a colleague, criticized the ongoing visit by Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina Wazed to India, saying that she was meeting her Indian counterpart, “for the sake of power and to win the coming election.” The post included some cartoons of the prime minister.

He was accused of offences under section 57 of the ICT Act claiming that he, and the publisher of the post, were “opposition supporters” and that the post was an “injustice,” “condemnable,” and a “betrayal to the country.” Denied bail by both the magistrate and district courts, Islam, who denies the offence, was detained for three months before the High Court released him in July 2017. Meanwhile, the author of the original post, reportedly went into hiding fearing his own arrest.

***

Section 57 of ICT Act authorizes the prosecution of any person who publishes, in electronic form, material that is fake and obscene; defamatory; “tends to deprave and corrupt” its audience; causes, or may cause, “deterioration in law and order;” prejudices the image of the state or a person; or “causes or may cause hurt to religious belief.” These broad and sweeping terms invite misuse of the law.

When Bangladesh first enacted the ICT Act in November 2006 to regulate digital communications, legal protections within the law limited the number of arrests and prosecutions. In 2013, the government amended the law, eliminating the need for arrest warrants and official permission to prosecute, restricting bail, and increasing prison terms if convicted. A new Cyber Tribunal dedicated to dealing with offences under the ICT Act was also established. As a result, the number of complaints to the police, arrests, and prosecutions has soared.

Between 2013 and April 2018, the police submitted 1271 charge sheets, most of them under section 57 of the ICT Act. Many of these cases involved multiple accused.

Often, it seems, the intent is to intimidate, with relatively few convictions—according to anecdotal comments from court officials—resulting from prosecutions. In September 2017, Md Nazrul Islam Shamim, special public prosecutor of the Cyber Tribunal, told The Dhaka Tribune that 65 to 70 percent of cases filed under section 57 cannot be proved in court. “Some cases are totally fabricated and are filed to harass people,” he said. In the first three months of 2018, of the nine cases where trials were concluded, eight were acquitted.

However, the impact of being arrested for a criminal offense can be severe on the individual, their family, and on free speech, as those who might otherwise speak out choose to self-censor rather than risk arrest and months of imprisonment. “A sinister section such as section 57 must be repealed soon,” the Bangladesh daily, New Age, said in an August 2017 editorial, “or, else it must be resisted and repulsed by not only the journalist community but also society at large.”

Following public outrage, Bangladesh authorities pledged to repeal the ICT Act, and on January 29, 2018, the cabinet approved a new Digital Security Act. However, the proposed draft is in some instances even broader than the law it seeks to replace and violates the country’s international obligation to protect freedom of speech.

This report—based on investigation of police and court documents and interviews with dozens of accused—details violations of free speech rights under section 57 of the ICT Act and concludes with recommendations to the Bangladesh government aimed at ensuring that any new law does not open the door to further violations.

Information and Communication Act

Between 2006, when the law was first enacted, and 2013, when it was amended, police data shows that while there were 426 complaints, only a few resulted in arrests or prosecution. However, after the law was amended in October 2013 the situation changed dramatically.

Hundreds, including several journalists, have been accused under section 57 for criticizing the government, political leaders, and others. In the first three and half months of 2018 alone, police submitted 282 charge sheets with Cyber Tribunal officials. Most involve criticism of the government, defamation, or offending religious sentiments, while the rest are allegations against men publishing intimate photographs of women without their consent. After recent student protests, on April 8, 2018, a police officer filed a complaint referring to 43 “provocative” Facebook posts which “many have liked and commented on” that has, as a result, “created a situation which could potentially harm society and create chaos.” Yet, apart from a few lewd characterizations, these posts contained legitimate commentary about an ongoing political protest.

The Cyber Tribunal provides no official data on the number of convictions and acquittals, but anecdotal evidence suggests few people have been convicted to date. The impact, however, of an arrest for a criminal offense may be significant. As Frank La Rue, former UN special rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, has stated:

Individuals face the constant threat of being arrested, held in pretrial detention, subjected to expensive criminal trials, fines, and imprisonment, as well as the social stigma associated with having a criminal record.

In addition, such treatment may chill free speech. “The government has reassured the public of their commitment to freedom of speech,” the Dhaka Tribune said in a September 2017 editorial. “Then why does section 57 continue to be a tool of harassment?”

Punishing Government Critics

Section 57 is often used in Bangladesh to prosecute those who criticize individual politicians, particularly the prime minister and her relatives. Under the 2013 amendments, a person may be arrested simply on the basis of a complaint to the police, regardless of whether the person filing it has themselves been prejudiced, defamed, or otherwise “injured” by the offending material.

Members and supporters of the ruling Awami League party have exploited this rule to file numerous complaints alleging that online speech has defamed or prejudiced the prime minister, other government officials, or the ruling party.

For example, on August 27, 2016, Rashedul Islam Raju, general secretary of the Awami League’s student wing based at Rajshahi University, complained to police about three Facebook posts by Dilip Roy, a student involved with a left-wing opposition party. Raju said the posts, including one that stated, “I can't label a dog Awami League, because it would be ashamed to be labeled as such,” constituted a threat to the prime minister, insulted her father (the country’s first president), and defamed the Awami League. Roy was arrested the next day, and remained in custody for three months before the High Court granted bail.

In other cases, police have acted directly against government critics without waiting for a complaint. For instance, on September 5, 2016, Shahadat Hossen Khondaker, a Bangladesh railways employee, was arrested for allegedly posting “anti-government statements” on Facebook. These posts criticized the trial of Mir Quasem Ali, convicted of crimes committed during the country’s independence war. Shahadat remained in detention for 11 months before he finally obtained bail in August 2017.

One of the most well-known uses of section 57 to target government critics involves Odhikar, a Dhaka-based human rights organization. On August 10, 2013, Odhikar’s secretary, Adilur Rahman Khan, was arrested on “suspicion of causing disruption to society” and “carrying out a conspiracy against the state.” His arrest came three months after the group published a report documenting alleged killings of protesters by law enforcement during a rally by the conservative Islamist organization, Hefazet-e-Islami. On September 3, police filed a case against Rahman and Nasiruddin Elan, Odhikar’s director, under section 57 of the ICT Act, alleging the report was “fiction.” Both men were eventually released on bail, but the case remained pending at time of writing.

Journalists have also faced arrest for writing online about alleged government or corporate corruption or inappropriate conduct. On September 1, 2016, Siddique Rahman, editor of the Daily Shikkha, a news website dedicated to education reporting, was arrested in Dhaka after publishing articles about alleged corruption in a government education department. The arrest followed a complaint by the department’s former director general, who said the allegations were false and defamatory to her and “the nation,” would “provoke anyone to commit crimes,” and thus wreak “havoc in the law and order of the country.”

Protecting Religious Sentiment

Section 57 also criminalizes those whose online words or pictures “cause, or may cause hurt to religious belief.” At a time when religious fundamentalism has become hotly debated on social media, these vague provisions create a significant risk of arrest for anyone writing about Islam with any critical perspective.

For example, one of the earliest prosecutions for hurting religious belief involved the arrest of four young men in Dhaka on April 1, 2013 for making “derogatory comment[s] about the Prophet Mohammad” on Facebook and in various blogs. The High Court granted bail a month later and during hearings in February 2014 issued an order asking the government to explain why proceedings against the four men should not be quashed—one of the few cases in which the High Court has stopped a section 57 prosecution.

On September 26, 2015, Mohan Kumar Mondal and his colleague Shawkat Hossain were arrested in Satkhira after an Awami League activist filed a case alleging that a Facebook post by Mondal had hurt religious beliefs of Muslims. The post criticized Saudi Arabia's security arrangements during the Haj that led to a deathly stampede killing hundreds. The men were detained for two months before the Cyber Tribunal granted bail on November 29, 2015.

Blogger Limon Fakir was arrested in April 2017 after a case was lodged against him and another well-known blogger, Asaduzzman Noor, for comments “defamatory of the prophet Mohammed”. Noor was subsequently arrested from Dhaka airport. They both remain in detention, refused bail by the High Court at a hearing in April 2018.

Digital Security Act

In 2015, several leading members of civil society filed a High Court petition against section 57, saying it violated freedom of expression and that prosecutions on vague grounds had created a “sense of terror” and self-censorship among writers, bloggers, journalists, and citizens. They argued section 57 violated article 39 of the constitution which provides, with exceptions, the right to free expression. The case remained pending at time of writing.

However, in August 2017, media outrage following the arrest of a reporter in Khulna for sharing an article on Facebook—about a goat that died almost immediately after being given by a minister to a villager as a relief measure—resulted in some action to restrict use of the law and enabled greater scrutiny of complaints. Acknowledging that section 57 is misused, the government proposed to replace the law with a new Digital Security Act that they argue places some checks and balances on arrests over speech.

However, some provisions of the proposed new law are even more draconian than those in section 57. These include forbidding discussion of facts around the independence movement and setting prison terms for vague offenses like publishing “aggressive or frightening” information. The law would also impose sentences of up to 10 years in prison for posting information which “ruins communal harmony or creates instability or disorder or disturbs or is about to disturb the law and order situation”—overbroad language that opens the door to further abuses.

Bangladesh’s journalists are also concerned about section 32 of the proposed act, which will treat the use of secret recordings to expose corruption and other crimes as espionage, arguing it will restrict investigative journalism and muzzle media freedom. Even as the law minister, Anisul Huq, said, “no journalist will be harassed by Section 32 of the Digital Security Act, as this law is not being formulated [to target] journalists,” the commerce minister, Tofail Ahmed, told journalists, “Various media reports often turn out to be humiliating for the MPs. Their images are tarnished. They are representatives of the people after all. So, this act has been formulated to prevent these [media reports].”

Also concerning is a life sentences provision in the proposed law for “negative propaganda and campaign against liberation war of Bangladesh or spirit of the liberation war or Father of the Nation.” The United Nations Human Rights Committee, the independent expert body that monitors compliance with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), to which Bangladesh is a party, has said that laws that penalize opinions about historical facts are incompatible with a country’s obligations to respect freedom of opinion and expression.

It is also essential that restrictions on public debate or discourse, even when the goal is a laudable one such as protecting racial harmony, are not implemented to the detriment of human rights, such as freedom of expression and freedom of assembly. A prohibition on speech that hurts someone’s religious feelings, reinforced by criminal penalties, cannot be justified as a necessary and proportionate restriction on speech.

Under international law, governments are required to protect and respect freedom of speech. Speech can only be restricted when this is clearly set out in domestic law, for legitimate reasons (as set out in international treaties), and only when the measures to restrict the speech are proportionate. Criminalization of speech offenses should only be imposed for the worst cases, such as direct incitement to violence, and not for speech such as criticism of the authorities or defamation.

The internet and social media give individuals unprecedented ability to communicate and access information across borders. Governments, including that of Bangladesh, have welcomed and sought to actively harness the internet to further social and economic development. Instead of fearing such communication will amplify dissatisfaction, Bangladesh should take steps to protect freedom of expression, and welcome peaceful dissent and criticism.

Key Recommendations

- Bangladesh authorities should publicly uphold the right to free speech, including criticism and dissent.

- While the government should immediately act on its pledge to repeal section 57 of the ICT Act, it should ensure that the proposed Digital Security Act that will replace the ICT Act conforms to international standards for the protection of freedom of expression.

- Bangladesh should consult with various UN mechanisms, including the UN special rapporteur on the promotion of the right to freedom of opinion and expression to ensure the Digital Security Act conforms to international standards.

Methodology

This report is based on field research and interviews conducted in Bangladesh from March 2017 to January 2018.

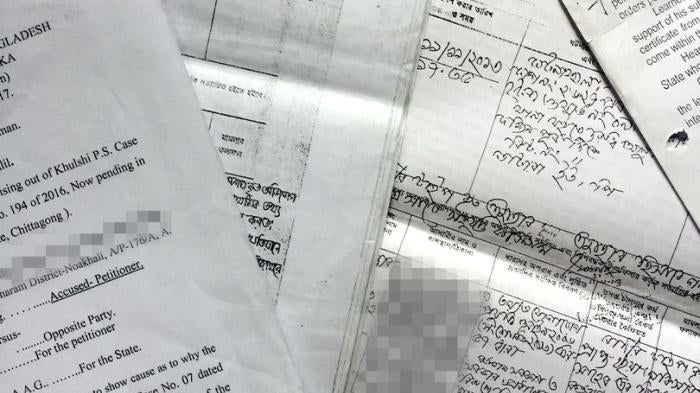

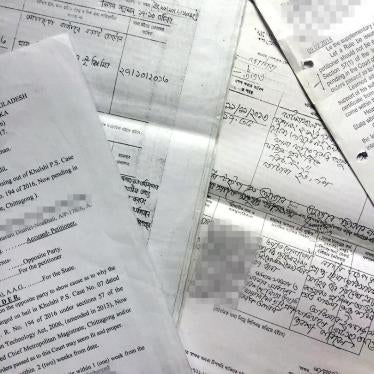

It is based on information obtained by Human Rights Watch relating to over 115 cases involving more than 200 individuals filed at police stations involving allegations under section 57 of the ICT Act. Human Rights Watch worked with Odhikar, a Dhaka based human rights organization, to identify and collate much of the information.

Human Rights Watch also examined 40 written police complaints and First Information Reports, and more than 20 bail applications. In addition, Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 15 people accused of violating the ICT Act, including authors of social media posts and journalists. We also interviewed a dozen civil society activists, lawyers, and some government officials.

The interviews were conducted in person, by phone, or email. Translators were used in interviews conducted in Bengali. We also examined social media content that led to prosecutions. We paid no remuneration or other inducement to victims and witnesses that spoke with us.

A significant number of complaints under section 57 of the ICT Act have been filed against men who allegedly posted or distributed intimate images of women with whom they have fallen out or otherwise wished to humiliate, without the women’s consent. These latter cases are not dealt with in this report.

I. Background

Bangladesh authorities have long sought to limit freedom of expression, particularly in relation to media. However, the current ruling Awami League government is particularly harsh on critics, using a range of laws to prosecute dissent.

History of Crackdown on Free Speech

From 2001-2006, when the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP)—in an alliance with the Jamaat-e-Islami—was in office, the government repeatedly took legal action against its critics and those affiliated with the opposition Awami League.

The privately owned ETV, which received its license from the previous Awami League government, was closed following a court order.[1] Sedition cases were filed against civil society members, and criminal defamation cases were initiated against journalists.[2] In its 2004 annual human rights report, the US State Department said of Bangladesh, “Individuals cannot criticize the Government publicly without fear of reprisal.”[3]

In 2006, after violent protests over a disputed voter list around impending elections, the military stepped in and proclaimed a state of emergency.[4] During the two years in which the military-backed caretaker government was in power, the Emergency Powers Rules allowed legal action against media critics, and authorized forced broadcast or publication of stories supporting the government.[5] The military’s intelligence wing, the Directorate General of Forces Intelligence (DGFI), threatened and intimidated journalists.[6]

Continuing Speech Restrictions

When the Awami League came to power following an overwhelming victory in elections at the end of 2008, the DGFI remained a powerful influence in reducing critical commentary in the media. In 2010, a current affairs program was cancelled based on claims that it was “anti-government and anti-state.”[7] Several broadcast journalists said the intelligence agency influences the content and what guests are allowed on talk shows. Newspaper editors and journalists also reported threats from intelligence agencies for criticizing the government or the military.

The state’s regulatory body closed two TV stations in 2009, including the pro-opposition Channel One. In 2013, the government-controlled regulatory body stripped two more pro-opposition stations, Diganta TV and Islamic TV, of their licenses for criticizing a security force crackdown on a protest by the Islamist group Hefazet-e-Islami.[8] The main pro-opposition newspaper, Amar Desh, was closed for a month in 2010[9] and was permanently shut down in December 2013, after its editor was arrested under the ICT Act.[10]

The Awami League won a second term in January 2014, after controversial elections that the main political opposition parties boycotted due to the government’s failure to hold the elections under a neutral caretaker government.[11] More than half the seats in the election were uncontested.[12] In its second term, the Awami League has become more authoritarian and even less tolerant of criticism.

On the one-year anniversary of the 2014 elections, opposition parties organized a series of violent national strikes and blockades. By the end of February 2015, up to 120 people, mostly members of the public, had been killed, most allegedly due to violence by opposition picketers.[13] Towards the end of March 2015, under intense public and international pressure, opposition parties stopped the strikes. However, scores of opposition activists then faced arbitrary arrests, secret detention, and enforced disappearances amid a crackdown on the opposition.[14]

In 2015, DGFI instructed major advertisers to stop advertising in Prothom Alo and Daily Star, the country’s largest Bengali and English language newspapers.[15] In January 2015, the owner of ETV was arrested after the station broadcast a speech by BNP politician Tarique Rahman.[16]

The government continued to put forward an image of respect for media freedom. In a hearing before the UN Human Rights Committee in March 2017, the law minister called Bangladesh “one of the most liberal countries of the world in terms of freedom of press and media,” citing publication of “1106 daily newspapers, 1169 weeklies, 127 fortnightlies and 280 monthlies” and “more than 28 TV channels, 25 of them...private.”[17] While there are indeed a large number of registered newspapers, many are not active or circulated. Of the main newspapers with wide readership, few are independent of the government or they face informal state restrictions. While there are 28 private television stations, in the last nine years, almost all new stations that received licenses were owned by pro-Awami League businessmen.[18]

In 2016, the Bangladesh Law Commission drafted legislation to outlaw “inaccurate” representation of war history and “malicious” statements in the media that “undermine any events” related to the war. It proposed that efforts to “trivialize” information related to the killing of civilians during the war would also be forbidden.[19] The current draft of the Digital Security Act would also impose numerous restrictions on using the internet, including a maximum 14 year sentence for “using a digital device” to spread “negative propaganda and campaign” regarding the independence war of 1971, the “spirit” of the war, or the first president.[20]

International Legal Standards

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (“ICCPR”) states everyone shall have the right to hold opinions without interference; the right to freedom of expression including freedom to seek, receive, and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing, or in print, in the form of art or through any other media of their choice. Bangladesh became a party to the ICCPR in September 2000.

The ICCPR, in article 19(3), permits governments to impose restrictions or limitations on freedom of expression only if such restrictions are provided by law and are necessary: (a) for respect of the rights or reputations of others; or (b) for the protection of national security, public order, public health, or morals.[21]

The UN Human Rights Committee, the independent expert body that monitors state compliance with the ICCPR, in its General Comment no. 34 on the right to freedom of expression, states that restrictions on free expression should be interpreted narrowly and that the restrictions “may not put in jeopardy the right itself.”[22] The government may impose restrictions only if they are prescribed by legislation and meet the standard of being “necessary in a democratic society.”

This implies that the limitation must respond to a pressing public need and be oriented along the basic democratic values of pluralism and tolerance. “Necessary” restrictions must also be proportionate, that is, balanced against the specific need for the restriction being put in place. General Comment no. 34 also provides that “restrictions must not be overbroad.”[23] Rather, to be provided by law, a restriction must be formulated with sufficient precision to enable an individual to regulate their conduct accordingly.[24]

Restrictions on freedom of expression to protect national security are permissible only in serious cases of threat to the nation and not for example the commercial sector, and should not be used to prosecute human rights activists or journalists for disseminating information in the public interest.[25] Since restrictions based on protection of national security have the potential to completely undermine freedom of expression, “particularly strict requirements must be placed on the necessity (proportionality) of a given statutory restriction.”[26]

With respect to criticism of government officials and other public figures, the Human Rights Committee has emphasized that “the value placed by the Covenant upon uninhibited expression is particularly high.” The “mere fact that forms of expression are considered to be insulting to a public figure is not sufficient to justify the imposition of penalties.” Thus, “all public figures, including those exercising the highest political authority such as heads of state and government, are legitimately subject to criticism and political opposition.”[27] The Human Rights Committee has further stressed that the scope of the right to freedom of expression “embraces even expression that may be regarded as deeply offensive.”[28]

The Bangladeshi Constitution guarantees the fundamental right “of every citizen to freedom of speech and expression.” The enjoyment of this right is made expressly subject to “reasonable restrictions imposed by law” which are “in the interests of the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign states, public order, decency or morality, or in relation to contempt of court, defamation or incitement to an offence.”[29]

These restrictions are inconsistent with section 19 of the ICCPR, which requires that the restrictions be “necessary” to protect the interests listed therein, a key element of international legal protection for freedom of expression.

II. Challenges to ICT Act and Proposed Digital Security Act

The stated objective of the ICT Act, which the BNP-Jamaat-e-Islami government first enacted in October 2006, appeared to be a largely innocuous effort at “legal recognition and security of information and communication technology.”[30]

In fact, most of the statute deals with digital signatures and electronic records. The current section 57 offence did exist, but it was “non-cognizable,” meaning that the police could only arrest a person after obtaining an arrest warrant from a court. Few of the 426 complaints filed with the police between 2006 and 2013 resulted in arrests.[31] Even among those arrested, few cases went to trial because a court could only accept a case for trial if it received a written report from police and approval from the controller.

In August 2013, the government[32] made significant changes to the ICT Act that increased the risk of abusive prosecutions under section 57:

- The offence became “cognizable,” i.e., police could arrest without a judicial warrant;

- Courts no longer needed “controller” approval to proceed to trial;[33]

- Offences under section 57 were made “non-bailable” i.e., bail cannot be sought as a matter of right but only at the court’s discretion; and

- The maximum potential penalty rose from 10 to 14 years in prison, with a minimum penalty set at 7 years’ imprisonment.

In addition, while offences under the ICT Act were earlier prosecuted in session courts, in February 2013 the government established a Cyber Tribunal to prosecute such cases.[34] Since the 2013 amendments, arrests and prosecutions under section 57 have increased dramatically and have been widely criticized. For instance, pointing out that some 85 percent of the cases filed under section 57 are eventually dismissed for lack of proof or worse because the allegations are found to be “completely baseless,” Dhaka Tribune said in a September 2017 editorial:

Laws exist to uphold justice, and such rampant abuse of the law does a disservice to our justice system. The government has reassured the public of their commitment to freedom of speech—then why does section 57 continue to be a tool of harassment?[35]

Section 57

Section 57 authorizes the prosecution of anyone who publishes, in electronic form, material that is (1) fake and obscene; (2) defamatory; (3) “tends to deprave and corrupt” those who are likely to read, see, or hear it; (4) causes or creates the possibility of “deterioration in law and order;” (5) prejudices the image of the state; (6) prejudices the image of a person; or (7) “causes or may cause hurt to religious belief.”

The provision duplicates long existing penal code offences, while eliminating some of the defenses or other protections provided by the penal code, and is inconsistent with international legal standards for the protection of freedom of speech.

Defamation

Section 57 allows prosecution of any online content that is found to be “defamatory” or “prejudicial to the image of a person.” Defamation is already made criminal under the Bangladesh penal code, 1860, which says:

Whoever by words either spoken or intended to be read, or by signs or by visible representations, makes or published any imputation concerning any person intending to harm, or knowing or having reason to believe that such imputation will harm, the reputation or such person, is said, except in the cases hereinafter excepted, to defame that person. [36]

Section 57 does not clarify whether safeguards in the penal code apply to claims of defamation under the section.[37] One safeguard that clearly does not apply is the requirement, put in place in 2011, that the court should first issue a summons to the accused person in any defamation case under the penal code.[38] At the time, the law minister said, "It will help put an end to harassment of journalists, editors, writers, and publishers."[39] Section 57 also increases the penalty that can be imposed for defamation, when committed electronically, from 2 years in the penal code to between 7 and 14 years in prison under the ICT Act.

It is increasingly recognized globally that defamation should be considered a civil matter, not a crime punishable with imprisonment. The UN special rapporteur on the protection and promotion of the right to freedom of opinion and expression has recommended that criminal defamation laws be abolished,[40] as have the special mandates of the UN, Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, and Organization of American States, which have together stated:

Criminal defamation is not a justifiable restriction on freedom of expression; all criminal defamation laws should be abolished and replaced, where necessary, with appropriate civil defamation laws.[41]

The UN Human Rights Committee has made a similar recommendation in interpreting international law on freedom of expression. The category of being “prejudicial to the image of a person” sweeps even wider than that of defamation, as it can be used to criminalize any criticism, however justified or minor, including criticism of public officials. The mere fact that forms of expression are considered insulting to a public figure, however, is not sufficient to justify the imposition of criminal penalties.[42] The vagueness of the offense, combined with the harshness of the potential penalty, increases the likelihood of self-censorship to avoid possible prosecution. The law also fails to restrict speech with sufficient precision to enable an individual to regulate their conduct accordingly, as the ICCPR requires.[43]

Prejudicing the Image of the State

Section 57 also criminalizes speech that “prejudices the image of the state.” This sweeping provision potentially applies to any criticism made of the government or any state body and is far too broad to comply with international legal standards.

The UN Human Rights Committee has stated that “all public figures, including those exercising the highest political authority such as heads of state and government, are legitimately subject to criticism and political opposition.… States parties should not prohibit criticism of institutions, such as the army or the administration.”[44]

Hurt to Religious Beliefs

Section 57 of the ICT Act allows prosecution for material, including social media posts, that “causes, or may cause, hurt to religious belief.”[45] Section 57 is broader than the penal code offenses against “insulting” or “wounding” religious feelings, both of which, unlike in the ICT Act, require a deliberate intent to do so, and carries a much heavier sentence.[46]

Section 57 effectively criminalizes speech that may offend others or be viewed as insulting to their religion. Laws that prohibit “outraging religious feelings” were specifically cited by the former UN special rapporteur on the right to freedom of expression, Frank La Rue, as an example of overly broad laws that can be abused to censor discussion on matters of legitimate public interest.[47]

Freedom of expression is applicable not only to information or ideas “that are favourably received or regarded as inoffensive or as a matter of indifference, but also to those that offend, shock or disturb the State or any sector of the population.”[48] Prohibiting speech that hurts someone’s religious feelings, reinforced by criminal penalties, is not necessary to protect a legitimate interest or proportionate to the supposed interest being protected.[49]

Deterioration of Law and Order

Section 57 prohibits online speech that “causes, or creates the possibility of deterioration in law and order.” While protecting public order is a legitimate basis for restricting speech under international law, the restriction must be narrowly drawn to restrict speech as little as possible, and be sufficiently precise as to allow people to understand and comply with the restriction, and to restrict the discretion of authorities tasked with enforcing it.[50]

The restriction on speech that “creates the possibility of deterioration in law and order” does not meet those standards. It is overly broad, and the vagueness of the language gives almost unfettered discretion to the government to use the law to punish speech it does not like. Almost any criticism of the government may lead to dissatisfaction and the possibility of public protests. The government should not be able to punish criticism on the grounds of protecting public order.[51]

Punitive Sentencing

Section 57 also permits the imposition of much heavier sentences than those that can be imposed for the penal code offenses that it duplicates. While violating section 57 can result in a sentence of between 7 to 14 years in prison, the maximum sentence for distributing “obscenity” in section 292 of the penal code is only three months’ imprisonment; two years’ imprisonment or a fine for “insulting religious sentiments” (section 295A); one year’s imprisonment or a fine for deliberately intending to “wound the religious feelings of any person” (section 298); and two years’ imprisonment for “defamation” (section 500). The severity of the criminal sanctions may cause speakers to remain silent rather than speak critically of the government or government officials.

According to court officials, as of June 2017, the Cyber Tribunal has convicted and sentenced 10 people to at least 7 years imprisonment.[52] Among them is Tonmoy Malick, 25, an electronics shop owner in the southern district of Khulna who was convicted in September 2014 of an offence under section 57 of the ICT for distributing a song that parodied Sheikh Hasina and her father, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, who led Bangladesh to independence in 1971.[53] The lyrics included:

The country belongs to my father, and whatever needs to be done in these circumstances, I will do it on my own, and I will not allow anyone to do anything…. Sheikh Hasina and her father have sold out the country…. they think the country belongs to them.[54]

Even within Bangladesh’s harsh sentencing regime, the sentence in the ICT Act is extraordinarily punitive.[55] However, few trials end in convictions. In the first three months of 2018, court officials said that eight out of the nine completed cases had resulted in unconditional release of the accused due to lack of evidence.[56]

Writs Challenging Section 57

The ICT Act has been challenged as a violation of rights under the country’s constitution. The High Court issued notices in two of those legal challenges asking the government to explain why section 57 should not be struck down.

The first of these two cases, filed before the harsher 2013 amendments, involved a petition by three lawyers challenging the authority of the Bangladesh Telecommunications Regulatory Commission (BRTC) under section 46 of the ICT Act to intercept information transmitted via any computer. In May 2010, BTRC had used its power to block Facebook access after one man, Mahbub Alam Rodin, was arrested for uploading cartoons of some leading politicians, including the prime minister and the leader of the opposition.[57]

On July 10, 2010, the High Court passed an order asking various government bodies to explain why both section 46 and 57 should “not be declared ultra vires of the constitution,” describing them as “vague and uncertain.”[58] Since the 2010 court order, there has been no further court hearing.

Following the 2013 amendment to the ICT Act, 11 academics, writers, and political activists[59] directly challenged the constitutionality of section 57 of the ICT Act in the High Court.[60] The High Court, in response on September 1, 2015, ruled seeking a response from the government on why the law did not violate constitutional protections.[61] There has been no further court hearing since this order was given, particularly after the government said it intended to repeal the law in response to repeated criticism from civil society.

Revised Procedures and the Digital Security Act

In January 2016, Law Minister Anisul Haq, acknowledging problems with the law, said that the government intended to replace it with a new Digital Security Act."[62] He repeated this intent in May 2017, also asserting the government did not intend to curb free speech.[63]

However, a few months after the law minister’s statement, the authorities were forced to make some administrative changes to the application of the law following a series of arrests that led to public outrage. These included the arrest in June 2017 of Golam Mostafa, the editor of a newspaper in Habiganj, for publishing an article suggesting that a particular Awami League member of parliament might not get a nomination at the next election[64] and in July 2017, the arrest of Abdul Latif Moral, a reporter at a local newspaper in Khulna, for sharing an article published in an online newspaper about the death of a goat given by a member of parliament as part of local relief efforts.[65]

On August 2, 2017, a few days after the arrest of Moral, the police issued instructions, requiring all officers to “maintain strong circumspection before filing cases,” and asked them to consult the legal wing of the police headquarters before registering any case under section 57.[66] Furthermore, within a week, the Awami League instructed its members, and those of its allied parties, to obtain prior permission from their central leaders before filing complaints under section 57.[67] While this did reduce the number of arrests, it did not address the fundamental problems leading to abuse.

On January 29, 2018, the cabinet approved a draft law, intended to replace the much-criticized Information and Communication Technology Act (ICT).[68] Sajeeb Wazed, the Bangladesh prime minister’s son and advisor, argued that the provisions in the new law remove the “most controversial elements” of the previous law.[69] While the offence of prejudicing the image of a person or state has been removed and proposed sentences are in general less punitive, the draft is in a number of ways even broader than the law it seeks to replace and violates the country’s international obligation to protect freedom of speech.[70]

Section 14 of the draft authorizes sentences of up to 14 years in prison for spreading “propaganda and campaign against liberation war of Bangladesh or spirit of the liberation war or Father of the Nation.”[71]

Section 25(a) would permit sentences of up to three years in prison for publishing information that is “aggressive or frightening,” broad terms undefined in the proposed statute. The use of such vague terms violates the requirement that laws restricting speech be formulated with sufficient precision to make clear what speech would violate the law. The vagueness of the offense, combined with the harshness of the potential penalty, increases the likelihood of self-censorship.

Section 31, which would impose sentences of up to 10 years in prison for posting information that “ruins communal harmony or creates instability or disorder or disturbs or is about to disturb the law and order situation,” is similarly flawed. Without clear definition of what speech would be considered to “ruin communal harmony” or “create instability,” the law leaves wide scope for the government to use it to prosecute speech it dislikes. Section 31 also covers speech that “creates animosity, hatred or antipathy among the various classes and communities.” While the goal of preventing inter-communal strife is important, it should be done in ways that restrict speech as little as possible. UN human rights experts have stated:

It is absolutely necessary in a free society that restrictions on public debate or discourse and the protection of racial harmony are not implemented at the detriment of human rights, such as freedom of expression and freedom of assembly.[72]

The law’s overly broad definition of “hate speech” opens the door for arbitrary and abusive application of the law and chills the discussion of issues relating to race and religion.

Section 29, like section 57 of the ICT Act, criminalizes online defamation. While, unlike the ICT Act, it limits defamation charges to those that meet requirements of the criminal defamation provisions of the penal code, it is still contrary to growing international recognition that defamation should be seen as a civil matter, not a crime punishable with prison.

Section 28 imposes up to five years in prison for speech that “injures religious feelings.” While this provision, unlike section 57 of the ICT, requires intent, that addition is insufficient to bring it into compliance with international norms.

The proposed law has been widely criticized.[73] Journalists in Bangladesh are particularly concerned about section 32 of the proposed act, which stipulates, “If a person enters any government, semi-government or autonomous institutions illegally, and secretly records any information or document with electronic instruments, it will be considered as an act of espionage and he/she will face 14 years of imprisonment or a fine of BDT 2 million (US$ 24,000) or both.”[74] They fear that legitimate investigative journalism to expose failures by public officials will be deemed espionage.

Law Minister Anisul Huq has said the law will not be misused, “I can assure that no journalist will be harassed by Section 32 of the Digital Security Act, as this law is not being formulated targeting journalists.”[75] Commerce Minister Tofail Ahmed, however, told journalists, “Various media reports often turn out to be humiliating for the MPs. Their images are tarnished. They are representatives of the people after all. So, this act has been formulated to prevent these [media reports].”[76]

While the government’s stated intent to repeal section 57 is commendable, it should ensure that the new legislation comports with international standards for the protection of freedom of speech, and with requirements of Bangladesh’s constitution.

III. Targeting Criticism of Government

An analysis of cases filed under section 57 of the ICT Act demonstrates the potential for abuse of the provision and the need to ensure that any new legislation not replicate its more problematic provisions.

Section 57 cases start when a person files a complaint.[77] According to information from police headquarters, as of June 2017, a total of 927 complaints have been filed under section 57 since the ICT Act was adopted in 2006.[78] Most of the complaints that Human Rights Watch investigated were filed by government supporters or activists. While in most cases the complaints were filed against just one person, some complaints contained allegations against multiple people.[79]

Under the procedures in place since the 2013 amendments, the police can use a complaint as the basis for arrest. If, after investigation, the police consider there is sufficient evidence to support the initial complaint, they submit a charge sheet[80] to the Cyber Tribunal based in Dhaka. Records of the Cyber Tribunal show the police submitted a total of 1,271 charge sheets between the creation of the court in 2013 and April 15, 2018.[81] Following the submission of the charge sheet, the Tribunal “frames charges” against the accused, which is the formal beginning of the trial.

The number of charge sheets or cases submitted to the court has increased significantly each year, from three in 2013 to 568 in 2017. [82] While the vast majority—around 90 percent according to court officials—involve section 57 of the ICT, some of the cases involve offences under other provisions of the ICT Act.[83]

Under the 2013 amendment of the ICT Act, police are not obliged to obtain a court warrant before making an arrest. Thus, any complaint filed at a police station can, and almost always does, lead to an immediate arrest.[84] Once an arrest has been made under section 57, the lower courts often deny bail, particularly since it was made a non-bailable offense in the 2013 amendments.[85] While the High Court generally grants bail to the accused on appeal, the process can take months. As a result, the accused is almost always detained for at least a month, often longer, before being granted bail.[86]

In some cases, the accused have gone into hiding to avoid arrest. A small number of people, with access to lawyers in Dhaka, applied for interim bail at the High Court before they could be arrested.[87] In such cases, as a condition of providing short term bail, the High Court required the accused to surrender, if ordered, to a lower court.[88]

Number of cases filed at the Cyber Tribunal:

|

Year |

Number |

|

2013 |

3 |

|

2014 |

33 |

|

2015 |

152 |

|

2016 |

233 |

|

2017 |

568 |

|

2018* |

282 |

|

Total |

1,271 |

* until April 15, 2018

The court does not maintain data on convictions and acquittals. The Cyber Tribunal prosecutor told Human Rights Watch that there have been 10 convictions under section 57, but was unable to provide further details.[89] Md Nazrul Islam Shamim, special public prosecutor of the Cyber Tribunal, told the Dhaka Tribune that most cases filed under section 57 cannot be proved. “Some cases are totally fabricated and are filed to harass people. Most of these cases are settled out of court,” he said. [90]

Although the government has accepted that the ICT Act has led to abuses and proposed replacing it with the Digital Security Act, the law continues to be in force. In April 2018, after students at Dhaka university started a protest aimed at reducing quotas in government jobs and demanding a merit-based system instead, the police launched a crackdown. On April 8, 2018, a police officer filed a complaint, referring to 43 “provocative” Facebook posts that “many have liked and commented on” which “created a situation [that] could potentially harm society and create chaos,” and proposed action under section 57.[91]

Targeting Known Government Critics

Section 57 first came to public attention via the April 2013 arrest of Mahmadur Rahman, editor of Amar Desh—the most prominent pro-opposition newspaper—and the August 2013 arrest of Adilur Rahman, secretary of the human rights organization Odhikar.[92] Both of these cases were initiated before the amendment of the ICT Act.

Mahmudur Rahman

Between December 9 and 13, 2012, Amar Desh published transcripts of private

Skype conversations of Nizamul Huq, the chairman of the International Crimes Tribunal—responsible for holding trials against those accused of international crimes during the country’s war for independence. The transcripts raised significant questions about the independence of the court.[93] Huq resigned after Amar Desh and the Economist published the leaked transcripts. [94]

On December 14, 2012, a prosecutor filed a complaint at the magistrate’s court against Mahmudur Rahman, the paper’s acting editor, and its managing director, Hasmat Ali, stating that the publication had “been publishing negative news on the International Criminal Tribunal, and has been questioning the tribunal in different ways.”[95] The complaint then referred to the titles of five articles,[96] which it asserted had “created negative idea[s] on [the] International Criminal Tribunal in the mind of the general mass and the international media” and “defamed” the tribunal judges and prosecutors, wounding their “self-respect.”[97] It also alleged that Rahman and Ali had committed sedition.

On April 11, 2013, police arrested Rahman at his office, and seized computers and the printing press. Numerous other cases involving alleged involvement in political violence were filed against Rahman during his subsequent detention.

In November 2015, two-and-a-half years into his detention, the chief metropolitan magistrate rejected Rahman’s bail application, as did the Cyber Tribunal a couple of months later. The High Court finally granted him bail on January 25, 2016.[98] A government appeal to the appellate division against the bail ruling failed. However, Rahman was not released from jail until November 2016 when he finally received bail for all the other cases that had been filed against him.[99] The cases are still ongoing at time of writing.

Adilur Rahman Khan and Nasiruddin Elan

On May 5, 2013, a conservative Islamic organization, Hefazet-e-Islami, held a huge rally in the center of Dhaka to protest against “atheist bloggers” who criticized fundamentalist Islam, as well as in support of its 13-point charter of demands, which included restriction on women’s rights and the introduction of a blasphemy law.[100] There were allegations by Hefazat and independent media that security forces used excessive force in these clashes, killing dozens.[101]

The Dhaka-based human rights organization Odhikar published a report on June 10, 2013, finding that 61 Hefazet supporters had been killed during the security operation. In July 2013, the Information Ministry wrote to Odhikar asking for details of those that had died, but Odhikar said that it would only provide this information to an independent inquiry commission.

On August 10, 2013, Adilur Rahman, Odhikar’s secretary, was arrested on suspicion of causing disruption to society and carrying out a conspiracy against the state by allegedly publishing a report containing false information.[102] The following day, he was produced in the magistrate court and the court gave the police permission to search Odhikar’s office. Police then seized laptops and computers from his office. On September 3, police lodged a case against Rahman under section 57 of the ICT Act,[103] claiming they found a list of 61 people killed on the organization’s computers that was “a product of fiction.”[104] Odhikar says police used an “unverified” and not yet final list.[105]

The High Court granted Rahman bail on October 8, 2013. Meanwhile, on September 11, the Cyber Tribunal had issued a warrant for the arrest of Odhikar’s director, Nasiruddin Elan, and on November 6, Elan was remanded in jail. The High Court granted him bail on November 24, 2013.

On January 8, 2014, the Cyber Tribunal framed charges against Rahman, rejecting an application that the accused should be discharged from the case. On January 21, a High Court bench passed an order temporarily staying proceedings after an application to quash the case.[106] However, following a full hearing of the defense application, on January 9, 2017, the court ruled the criminal case should continue due to “prima facie evidence” of a criminal offence.[107] At time of writing, the High Court ruling was being appealed at the Appellate Division.

Targeting Political Criticism in Social Media

Subsequent to the two cases discussed above, and the change in the law, section 57 began to be used more regularly against social media commentary, satire, and other forms of criticism against the prime minister, her deceased father (the country’s independence leader), ministers, judicial officials, and the government more broadly.[108]

Most cases involve Facebook posts. None of the initial complaints in these cases have been filed by the prime minister or others mentioned in the posts. Instead, the arrests under section 57 in the cases documented by Human Rights Watch have been based most often on complaints made by police or activists of the governing Awami League.[109]

Some complaints allege that the social media posts were “defamatory” to the prime minister or other political leaders. Others arbitrarily allege that the comments create “the possibility of the deterioration of law and order.”[110] Some complaints even blatantly accuse the person of supporting opposition parties. In some cases, multiple complaints have been filed in different police stations, requiring the accused to seek bail in multiple courts. In many cases, the accused deny involvement in the publication of the Facebook posts that form the basis of the complaint.

Criticizing the Prime Minister or Family Members

Dozens of people have been arrested since 2013 for criticizing the prime minister or her relatives. In most cases that Human Rights Watch and other human rights organizations have documented, the complaints were filed by members of the public who are supporters of the ruling Awami League.

Monirul Islam

On April 13, 2017, Monirul Islam, 32, a rubber plantation worker in Srimangal, was arrested following a complaint made by a pro-government trade union leader, Mohammad Araj Ali. The complaint said that Monirul had “liked” and “shared” a Facebook post containing objectionable photographs and comments about the Indian and Bangladesh prime ministers.[111] The original post by Kabir Hossain was alleged to have said that the prime minister was meeting her Indian counterpart “for the sake of power and to win the coming election.” Hossain went into hiding to evade arrest.

Authorities filed charges against both men, saying the Facebook comment defamed the prime minister, harmed the image of Bangladesh, and represented a “betrayal to the country.”[112] The trade union leader who filed the police complaint said the accused men were opposition supporters, noting, “as a citizen of this country and as a government employee, after seeing the post in Facebook.… I was extremely hurt and agitated.”[113] The case remains under investigation, and no charge sheet had been submitted at time of writing.[114]

Mohammad Sabuj Ahmed

On September 10, 2016, Mohammad Sabuj Ahmed, 35, a leader of the Jamaat-e-Islami in the district of Magura, was arrested for allegedly publishing “false, obscene, and defamatory information” on Facebook relating to Sheikh Hasina’s father, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.[115] His arrest was based on a complaint from Awami League party member Mohammad Al Imran[116] and related to a Facebook post that said, “Today, the people who make the whole country ‘Vatican of Mujib,’ I have one message to them—if Hasina falls, the godlike image of Bangabandhu will fall as well.”[117] His case was before the Cyber Tribunal at time of writing.

Dilip Roy

Dilip Roy, a leftist student leader at Rajshahi University, wrote three short satirical Facebook posts in August 2016 about Sheikh Hasina, the Awami League, and the government’s energy policy. One post said, " I can't label a dog Awami League, because it would be ashamed to be labeled as such." Another said the prime minister would be cheated by her own party members.[118] A third said that the prime minister risked popular protests by going ahead with a controversial energy plant in Phulbari.[119]

His arrest on August 28, 2016, followed a complaint by Rashedul Islam Raju, then-acting chairman of the Bangladesh student Awami league at Rajshahi University. Raju alleged the posts were, “a threat to the Prime Minister, an insult to the father of the nation and a provocative information against Bangladesh Awami League, which is defamatory to the organization.”[120] Roy was detained until November 14, when the High Court granted bail.[121] The police submitted their initial report to the Cyber Tribunal on November 9, 2017 and there are ongoing hearings on whether to frame charges.

Rifat Abdullah Khan

Rifat Abdullah Khan, 17, son of Jamaat-e-Islami party leader Rafiqul Islam Khan, was arrested on February 21, 2015, following a complaint lodged at Ramna Model Police Station by a police inspector claiming that Khan, along with 51 other people,[122] had circulated false, obscene, and defamatory cartoons of the prime minister, her father, ministers, judges, and high-ranking members of the law enforcing authorities.[123]

One post included photoshopped pictures of the prime minister, her son, and senior officials of the “highly abusive” Rapid Action Battalion (RAB) with the caption, “Wearing underwear over your pants does not make you superman.”[124] The complaint said that these images were an attempt to create sympathy for the opposition Jamaat-e-Islami, help the political opposition movement, seek cancellation of the “ongoing trial of war criminals,” and try to “create chaos in society.”[125]

On December 10, 2015, after nine months in detention, the High Court granted Rifat bail.

At time of writing, the police had completed their investigation and the case was before the Cyber Tribunal. The High Court subsequently stayed proceedings.[126]

Imran Hossain Arif

On September 3, 2014, Imran Hossain Arif, 30, was arrested in Kushtia following a complaint from Anik Hossain, an Awami League youth leader. Hossain complained about Arif’s Facebook comment which said, “If Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was the father of the nation, then Sheikh Hasina is my sister and Sajib Wajed Joy is my nephew.”[127] When one reporter asked the officer in charge of Kumarkhali police station why the post was derogatory when most of her party men addressed the prime minister as “sister,” he replied, “He has been prosecuted as it is derogatory to us, if not to you.”[128] Police submitted a charge sheet and the case was pending before the Cyber Tribunal at time of writing.

Major Samuzzoha

On August 19, 2014, Major Samuzzoha, a retired army officer working at Grameen Phone, a telecom company, was arrested in Dhaka for making a comment a year earlier on the attire of the prime minister in a photograph in which she wore a sari and scarf. The FIR said that he had written, “Is this called the ‘Pakhi’ dress,” referring to a style of clothing made famous by an Indian television serial.[129]

The officer from Demra police station who initiated the case said that this comment was derogatory, would mar the country's image, and was a threat to law and order since others had remarked and shared the Facebook post.[130] The FIR stated that during interrogation, the accused admitted to having published this post. Major Samuzzoha denies this. “It is a total lie,” he said. “They showed me a few photoshopped printed pages of Facebook and told me those are posted from my Facebook. They didn’t find it in my Facebook, as I opened my [page] to them. And I didn’t admit any wrongdoing during my 10-day remand, despite many threats and psychological torture.”[131] He was detained for nearly six months before obtaining bail. Police filed charges and the case was pending before the Cyber Tribunal at time of writing.[132]

Hadisur Rahman

Following a “tip-off” that a group of people were publishing distorted pictures of Sheikh Hasina, police said they arrested Hadisur Rahman on January 28, 2014. [133] Police said they had recovered photoshopped images of the prime minister from Rahman’s mobile phone, including one where she “looked like a blood-thirsty Eagle,” and another of her in the form of a Hindu goddess. The complaint lodged by the police said that the second picture “hurts religious sentiment and is provocative to a certain religious group.”[134] Also accused were Nurul Amin and seven other unnamed individuals, whom the police claimed had made derogatory comments about the prime minister. Rahman spent a year in jail before the High Court granted him bail. The trial is continuing.[135]

Mohammad Nurun Nobi Sujon

On November 11, 2013, a RAB-1 officer arrested Md Nurun Nobi Sujon, 32, at his home in Dhaka. The complaint lodged by the RAB officer at Uttara police station said after some “serious interrogation”, Sujon revealed that he was an active member of the student wing of the Jamaat-e-Islami, was involved in politics, and had revealed the names of two other men, Mohammad Abul Yusuf and Mohammad Jassim, who were “involved in disseminating false and derogatory information and photos of the present head of government.” [136] The complaint said that the three men “tried to create an unstable situation by provoking the common people. Under these circumstances section 57 is being used.”[137]

Yusuf and Jassim went into hiding to evade arrest. The police have submitted a charge sheet and the case was pending before the Cyber Tribunal at time of writing.[138]

Mohammad Benazir

Late on November 9, 2013, Benazir, 28, was arrested in Dhaka for allegedly posting derogatory pictures and comments about the prime minister and some government ministers.[139] One picture of the prime minister was captioned, “I am a hawker of democracy. Do you want to buy democracy?” and in another, “I respect the constitution but I will do what I want.” He also posted satirical remarks about the home minister and the Indian prime minister.[140] A charge sheet has been submitted to the Cyber Tribunal and a trial was proceeding at time of writing.[141]

AKM Wahiduzzaman

In September 2013, AKM Wahiduzzaman, a geography professor, was accused by A B Siddiqui, chairperson of the Awami Jononetri Porishod,[142] of defaming Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, her family, and her colleagues in four Facebook posts.[143] The complaint referred to a number of different posts: one questioned the capabilities of the prime minister and her children;[144] two others criticized the organization of the upcoming 2014 election and described the ruling party members of parliament as “neo-nazis;”[145] and the last suggested that some of the prime minister’s relatives collaborated with Pakistan’s military during Bangladesh’s independence war.[146]

Siddiqui argued in his original complaint that Wahiduzzaman had committed “criminal intimidation” and used “obscene language” to defame the prime Minister, her children, and other family members, causing her “image and honor” to be “ruined in the country and abroad…the kind of language that he has been using against the Prime minister is close to sedition.”[147] After Wahiduzzaman surrendered to the magistrate court on November 6, he was jailed for over a month before the High Court granted him bail.[148] Police submitted a charge sheet with the Cyber Tribunal, where the case was ongoing at time of writing. Wahiduzzaman has since left the country. [149]

Wahiduzzaman denied making the posts and says they came from a fake account using his name.[150] In a written message to Human Rights Watch, he said the consequences have been severe. “On November 7 of 2013, I was suspended from my job as the assistant professor of National University. Members of my family were threatened by pro-government activists and regularly harassed by the police. My university-going daughter is faced with abusive behaviour of pro-government student activists.” He added, “This case is a perfect example of how the [criminal justice system] functions without professional efficiency…while innocent citizens are victimized [and] how a group of pro-ruling party opportunists are offered privileges to abuse the justice process.”[151]

Criticizing Government, Corruption Allegations

Facebook posts that claim general corruption by the government and, in particular, Sheikh Hasina’s family, have also led to arrests.

Ehsan Habib and Three Others

This case involves posts written many years before the complaint was filed, with multiple cases initiated in different police stations over the same allegation, requiring the accused to make multiple bail applications.

On February 4, 2017, Nurul Baki Khan, an Awami League supporter, lodged a complaint with local police against Ehsan Habib, an assistant registrar at the Jatiyo Kobi Kazi Nazrul Islam University in Mymensingh, as well as the university’s registrar Aminul Islam. This followed student protests that started five days earlier on January 31, 2017, claiming that Habib had referred to them as “cows” on Facebook. On February 5, a university investigation committee suspended Habib.

In his police complaint, Khan said that Habib’s alleged Facebook post about “cows” had “created condemnation and hatred among the people.” He also drew attention to two posts that were published five years earlier on Habib’s Facebook page and claimed, without any evidence, that the two older posts were written jointly by Habib and another registrar, Aminul Islam, and were “indecent, defamatory, false and provocative statements undermining the honorable Prime Minister and Awami League leaders.”[152]

One of these posts, published on August 16, 2012, criticized the Awami League leaders for going into hiding at key moments of Bangladesh’s history.[153] The second, published on September 10, 2012, was a comment that a new hospital wing was yet to accommodate patients because the prime minister had not yet inaugurated it.[154]

The day after Habib was suspended, another Awami League supporter, Fozle Rabbi, lodged a complaint at Trishal Police Station in Mymensingh against Ehsan Habib and Aminul Islam as well as two other assistant registrars—Afruza Sultana and another man also named Aminul Islam. [155] He claimed that all four were Jamaat-e-Islami supporters who were “strategically engaged with many misdeeds, including damaging the image of the current democratic government by creating instability within the government.”[156] On February 13, 2017, three of the registrars obtained anticipatory bail.[157]

Arman Sikdar

Arman Sikdar was arrested on February 4, 2017, after a local student leader of the Awami League complained that Sidkar’s Facebook post denigrated the prime minister and the Awami League student wing with his comment “Now the crooks are giving advice.”[158] Sikdar denied the allegation and said his account was hacked. The case was pending at time of writing.

Ruhul Amin

Ruhul Amin was arrested on September 22, 2016, after a complaint that he had “defamed” the prime minister and her family in “an indecent, defamatory, [and] provocative” Facebook post.[159] Amin accused the family of corruption saying, “The truth is a thief is born in a thief’s house. The whole world now know[s] that the family of Sheikh Hasina is a family of thieves. I am inviting Sheikh Hasina to tender her resignation.”[160] The FIR was lodged six months after the posts were published, and said that Amin was a member of the student wing of the Jamaat-e-Islami. The High Court granted him bail on January 24, 2017.[161]

Tanvir Ahmed, Tawhidul Hasan, and Mohammad Omar Faruq

Sometimes the complaints provided to the police do not provide details of what was allegedly written on the social networking sites, but only claim that the comments are anti-state and seeking “to create chaos in the country.”[162] However these are sufficient for the police to arrest the accused.

On December 3, 2015, Tanvir Ahmed, 38, Tawhidul Hasan, 21, and Omar Faruq, 22, were arrested for such statements on Facebook. According to a complaint filed at Adabor Police station in Dhaka, Mohammad Amirul Islam, a senior warrant officer belonging to RAB-2, heard that some men had gathered near Ali Ahmed Jame Mosque and were “engaged in a meeting to carry on anti-government activities.”[163]

The RAB officer said that when he arrived at the place, he found about five to six people having a discussion who then ran away, but that he and his colleagues managed to catch three of them. “When we asked them that why they had gathered there, they couldn’t give us any answer. Later, they confessed that were involved in making anti-state posts and comments in Facebook with fake IDs, and that they had gathered there to carry on such activities.”[164]

Criticizing the International Crimes Tribunal

Two of the people mentioned above, arrested for comments about the prime minister, were also accused of criticizing the International Crimes Tribunal.[165] Hadisur Rahman was arrested on January 28, 2014, in part for criticizing the death sentence imposed on Jamaat leader Quader Mollah, who was executed the previous month. The complaint made by a police officer stated, “on many occasions he termed the Prime Minister as a ‘judicial killer’ and in some posts also expressed that he would like to be like Abdul Quader Mollah, whom he termed a martyr, used poetry to express his anti-liberation war view, and reminded the prime minister about what happened in 1975.”[166]

Rifat Abdullah Khan, arrested on February 21, 2015, was also accused of seeking “to cancel the ongoing trial of war criminals.” The complaint specifically mentioned that he had made “derogatory remarks about the skype conversations referring to the Chief Justice and the International Crimes Tribunal Judge Nizamul Huq Nasim.”[167]

Shahadat Khondaker

On September 5, 2016, Shahadat Khondaker, an employee of the Bangladesh railways, was arrested for allegedly posting “anti-government statements” on Facebook. Police said that he had “intentionally and electronically published defamatory, indecent, false, inappropriate, and provocative statements against the Honorable Prime Minister and Supreme Court Judges to the public, creating a possibility of law-enforcement decline and damaging the image of the state and person.”[168]

Khondoker had criticized the proceedings of the International Crimes Tribunal, arguing that the “prosecution could not prove where and whom Mir Quasem Ali murdered,” and questioning the integrity of the evidence, as well as the political neutrality, of judges.[169] In another message, he referred to the Jamaat-e-Islami politicians convicted of crimes by the Tribunal as “roses,” writing, “Millions of roses await blossoming, if a few more flowers fall to make a complete flower necklace, then I will not stand in the way.”[170] Khondaker eventually obtained bail in August 2017.[171]

Mohammad Osman Gony and Abul Hasan Rasu

On April 14, 2015, Mohammad Osman Gony, 20, and Abul Hasan Rasu, 27, both student leaders and supporters of the Jamaat-e-Islami party, were arrested from Comilla Cadet College for posting “insulting cartoons and posts” about the prime minister and other officials on Facebook.[172] The FIR claimed that the two men were “creating political unrest to sabotage the trial of the war criminals.”[173] The case was pending at time of writing.

Criticizing the Judiciary

Criticism of the judiciary has also led to arrests under the ICT Act.

Sheikh Noman

On April 21, 2017, Sheikh Noman was arrested in Sreemangal town in Moulvi Bazaar after the police received a complaint that he had criticized the chief justice in a Facebook post for “attending different political programs.” The complaint was made by lawyer Enayet Kabir Mintu, an assistant to the public prosecutor, who said that Noman was a BNP supporter and had, in publishing his criticism, “tarnished the image of the independent judiciary of the country.”[174] Mintu argued the chief justice had become a “hated target of a vested quarter” because of his involvement in the International Crimes Tribunal.[175]

Noman, however, said that he supported the student wing of the governing Awami League, and that someone else had published the Facebook post using a phone that he had lost at an acrimonious Awami League political meeting on March 22, 2017. He said the complaint to police was made by the assistant to the public prosecutor due to an argument he had had with public prosecutor Asadur Rahman, who had “threatened to teach me a lesson.”[176]

Norman was remanded into police custody. “I was not allowed to assign myself any lawyer initially,” he said. “During the remand hearing, the judicial magistrate also did not ask me any question about what I have done.” He remained in detention for nearly three months before obtaining bail in July 2017. “I was branded an opposition activist. Now, I am really worried about my future,” he said.[177] The investigation was still under process at time of writing.[178]

Nazmul Hossain, Othoi Aditto, Tariq Rahman, and Nusrat Jahan

On July 3, 2017, a lawyer filed a complaint at Kotwali police station in Dinajpur against Nazmul Hossain, a senior reporter at Jamuna Television. The lawyer objected to Hossain’s Facebook post criticizing preferential treatment given to judges, saying it “ridiculed the department of justice.”[179] Three others, Othoi Aditto, Tariq Rahman, and Nusrat Jahan Ishika, were accused of sharing the post but received anticipatory bail before they could be arrested.

The Facebook post, titled “The red staircase of Justice and Delwar’s crutch,” described how a disabled man in Kamlapur railway station used his crutch to help a couple get into a crowded train, while a High Court judge was provided the comfort of protocol. According to the FIR, Hossain concluded:

Some days ago, a justice of the High Court was saying that judges do not get enough benefits. They don’t have any computer, no AC, their roads are blocked with water. This kind of attitude hurts us. Why should a justice intimidate the authority to get this type of protocol? All these problems can be solved if they can follow the attitude of the disabled man. Then they don’t have to force people to show respect to them.[180]

The complaint to the police alleged that the journalist compared the “respected Judges of the Bangladesh High Court” with a beggar, thereby “disrespecting and defaming” the judge. The complainant said the post had “tried to lead the general people toward darkness, and make them lose faith on the system. He has all hurt the sentiment of all the people of Bangladesh.”[181] Nazmul had not been arrested at time of writing.[182]

Lewd or Morphed Images of Political Leaders

In addition to prosecutions for posts critical of the government or government officials, people have also been prosecuted for publishing tasteless images, including photo-shopped pictures of the prime minister with sexual innuendo.

Mohammad Alauddin Alo

Mohammad Alauddin Alo, 30, was arrested on January 17, 2016, for creating and disseminating obscene pictures of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina and former Foreign Minister Dipu Moni.[183]

He was arrested based on the complaint of a man called Nazimuddin, who stated that on the morning of January 16, he was at the Feni Noakhali highway bus-stand when he heard the accused talking about the prime minister in a derogatory manner, calling her “bad names.”[184] The men boasted that they had posted satirical pictures of her on the internet. When others at the bus-stand objected the men ran away, but Nazimuddin and others managed to catch Alauddin Alo, and said they “found three or four A4 sized printed papers in his hand which had a lot of pictures. Eight of them contained distorted pictures of the prime minister and the foreign minister Dipu Moni.” The complaint stated that in two pictures, the heads of the prime minister and Dipu Moni were replaced on the bodies of two nude men.”[185] Nazimuddin said that Alauddin Alo admitted that, with the assistance of the other accused, he had posted two pictures on Facebook.

Hasanul Haque Mithu

On October 5, 2016, Hasanul Haque Mithu, who runs a motor-parts shop, was arrested in Natore for posting “obscene” material on Facebook involving the prime minister and state minister Alhaj Zunayed Ahmed Palok, after a complaint by Mohammad Sohel Takuder.[186]

Mithu was denied bail by the magistrate. On November 8, 2016, he applied for bail at the sessions court, claiming the allegation against him was false and that the “case was filed to harass him politically.”[187] The sessions court judge rejected the bail application stating, “All the proof stands against him.”[188] Mithu claims that he had no knowledge of the post and that someone had uploaded the post with a “view to damaging my reputation.”[189]

IV. Crackdown on Media

While journalists are among those prosecuted under the ICT Act for their personal Facebook posts that criticize political leaders, a considerable number of cases have also been filed against journalists and editors in Bangladesh under the ICT Act concerning their professional writings. These fall into two categories: cases alleging journalists published allegedly false news about state authorities, and cases alleging journalists defamed someone in their reports.[190]

Alleged False News

Sarwar Alam