Findings and Recommendations

A. Positive Complementarity in Preliminary Examinations

The International Criminal Court (ICC) is a court of last resort.

Under the principle of “complementarity,” the ICC can only take up cases where national authorities—which have the primary responsibility under international law to ensure accountability for atrocity crimes—do not.

In the long-term, bolstering national proceedings is crucial in the fight against impunity for the most serious crimes, and is fundamental to hopes for the ICC’s broad impact. Where states have an interest in avoiding the ICC’s intervention, they can do so by conducting genuine national proceedings. As a result, the Office of the Prosecutor (OTP) can have significant leverage with national authorities in countries where it is considering whether to open an investigation in what are known as “preliminary examinations.”

The OTP has recognized this opportunity. In policy and in practice, the OTP is committed, where feasible, to encouraging national proceedings into crimes falling within the ICC’s jurisdiction in preliminary examinations. This makes the OTP potentially an important actor in what has come to be known as “positive complementarity”—the range of efforts by international partners, international organizations, and civil society groups to assist national authorities to carry out effective prosecutions of international crimes. These efforts include legislative assistance, capacity building, and advocacy and political dialogue to counter obstruction.

While early references to positive complementarity were primarily to the role of the court (see Appendix 1), the term has since evolved, particularly leading up to and after the 2010 ICC review conference in Kampala, Uganda. Momentum has been difficult to sustain since Kampala, but the term has garnered increased recognition and has come to encompass initiatives by a range of actors to encourage national prosecutions of international crimes.

These efforts are needed because domestic prosecutions of international crimes typically face several obstacles. Political will of national authorities to support independent investigations is essential, but is often absent or quixotic given that these prosecutions likely touch on powerful domestic and even international interests that oppose accountability. Prosecutions of mass atrocity crimes also require specialized expertise and support, including witness protection. Countries are often ill-equipped to meet these challenges.

While the OTP’s commitment to positive complementarity in preliminary examinations as part of this broader landscape holds significant potential to meet victims’ rights to justice for human rights crimes and to amplify the impact of the ICC on national justice efforts, it faces significant and steep challenges in seeking to translate its policy commitment into successful practice.

This report explores the extent to which it is realistic for the OTP to be able to deliver on this commitment, and asks whether domestic challenges are too great for the ICC’s commitment to positive complementarity to surmount.

As discussed below, some positive complementarity effects may be triggered simply through the OTP’s engagement with national authorities during the course of conducting its preliminary examinations. To go further, however, the OTP, like other complementarity actors, needs to have strategies to bridge the two pillars of “unwillingness” and “inability.” These include:

- Focusing public debate through media and within civil society on the need for accountability;

- Serving as a source of sustained pressure on domestic authorities to show results in domestic proceedings;

- Highlighting to international partners the importance of including accountability in political dialogue with domestic authorities;

- Equipping human rights activists with information derived from the OTP’s analysis, strengthening advocacy around justice; and

- Identifying weaknesses in domestic proceedings, to prompt increased efforts by government authorities and assistance, where relevant, by international partners.[1]

Many of these are strategies shared with other complementarity actors, but among these actors, the OTP is unique. As indicated above, its leverage with national authorities stems from the fact that, unlike international donors or civil society actors, it has the authority to open an investigation if national authorities fail to act. Under the court’s legal framework, however, the OTP’s jurisdiction can be blocked even by the appearance of national activity, regardless of whether this ultimately matures into effective domestic proceedings.

This unique leverage, therefore, comes with a unique catch: the OTP needs to strike a balance between opening space to national authorities, while it proceeds and is being seen to proceed with a commitment to act if national authorities do not. Where delay in ICC action does not result in genuine national justice, but provides space to national authorities to obstruct ICC action, it undermines the OTP’s influence with national authorities and the OTP risks legitimizing impunity in the view of key partners on complementarity.

B. Evolution in OTP Practice

OTP practice has changed significantly since a 2011 Human Rights Watch report, Course Correction. The report highlighted inconsistent approaches between situations, the rapid announcement of several new preliminary examinations, and a lack of substantive public reporting regarding progress in these examinations to back up initial publicity.[2]

Since that time, the OTP has made several important shifts in its approach to positive complementarity and preliminary examinations. These shifts are discussed in Appendix I. They include a more qualified posture on positive complementarity, seeking to engage national authorities only where relevant domestic proceedings are already underway or where national authorities have explicitly stated their commitment to undertaking such proceedings.

They also include its current practice of delaying specific positive complementarity initiatives until after the OTP is certain that potential cases fall within the ICC’s jurisdiction, bolstering its ability to engage governments in a more concrete manner. The OTP has also been more cautious in the publicity it seeks for its preliminary examinations, while also putting more substantive information about each examination into the public domain through its annual reports. Lastly, it has boosted, albeit in a still-too-limited manner, the number of staff members assigned to carry out preliminary examinations.

C. Key Findings on Colombia, Georgia, Guinea, and the United Kingdom

This report seeks to build on our 2011 report and evaluate the OTP’s impact on national justice through case studies on national proceedings in four countries that are, or were, the subject of OTP preliminary examinations—Colombia, Georgia, Guinea, and the UK.[3] The report spans OTP practice both before and after its consolidation in 2013 of a formal policy on preliminary examinations. It seeks to identify areas where further shifts in practice, particularly in the manner of engagement with national authorities, key strategic allies among international partners and civil society, and media could strengthen OTP impact going forward.

Our research is based on interviews with a range of stakeholders in each country case study including government officials in ministries of foreign affairs, justice, and defense; national investigating and prosecuting authorities; judges; civil society activists; journalists; and representatives of diplomatic missions and United Nations agencies. The four case studies were selected based on Human Rights Watch’s assessment that in each situation, certain prospects for national justice existed or had existed, such that it was reasonable to expect the OTP to have some impact; geographical diversity; existing Human Rights Watch expertise and research in the country; and the feasibility of carrying out research given available resources and staffing.

These four countries fall on a spectrum of OTP engagement with national authorities on domestic justice. Our research suggests that the OTP’s engagement has been most significant in Guinea, followed by Colombia, and far more limited in Georgia. In the UK, the OTP had not deployed a proactive approach to complementarity during the time period covered by our research.[4]

Results to date in national proceedings underscore a key point made above: expectations about the OTP’s influence need to remain realistic. In all four countries, authorities have initiated investigations. Prosecutions, however, have been more limited.

Investigations in Guinea into the September 28, 2009 stadium massacre had yet to lead to trials at time of writing, although in December 2017, following the completion of the investigation, the investigating judges referred the case for trial. Georgian authorities have abandoned their investigations into crimes committed during the 2008 armed conflict with Russia in the South Ossetia region, leading to the opening of an ICC investigation in January 2016. In the UK, where the preliminary examination concerns allegations of abuses committed by the country’s armed forces in Iraq, the creation of a special investigative body to look into allegations, the Iraq Historic Allegations Team (IHAT), now replaced by the Service Police Legacy Investigations (SPLI), has not resulted in any prosecutions. In Colombia, there has been a highly significant number of convictions of individuals accused of “false positive” killings, that is, cases of unlawful killings that military personnel officially reported as lawful killings in combat, but very scarce progress in prosecuting high-ranking officials.[5]

The case studies suggest that it is important not to overstate the prospects for success. Given the many persistent and stubborn obstacles to trying the most serious crimes before national courts, many preliminary examinations will result in the need to open ICC investigations. Objective factors—such as the peace process in Colombia or the cross-border nature of the Georgia-Russia conflict—place significant constraints on what the OTP’s preliminary examinations can achieve when it comes to national justice. Indeed, the OTP has, over time, calibrated its approach to positive complementarity, pursuing this as a strategy only where certain underlying conditions are met.

And yet, in each situation, our research has identified positive steps that are at least partly attributable to the OTP’s engagement.

There has been substantial progress in Guinea, in particular, where the OTP’s engagement has been more intense than in other situations and where over time the OTP as an external point of pressure seems to have contributed to progress by national officials and the engagement of other key international actors on justice.

In Colombia, sources interviewed for this report suggested that the OTP has been one of a number of important actors in keeping the need for accountability in these cases on the agenda. The OTP also worked effectively to counter at least one legislative proposal that might have undermined these prosecutions and was a factor in the development of relevant prosecutorial strategies. The latter was important to addressing a key obstacle to prosecutions. Its engagement has also been a factor in expediting progress in cases against low and mid-level defendants, but has yet to prove effective to address the main obstacle to prosecution of high-level officials: a lack of unequivocal political will to support these prosecutions. Some factors have been beyond the OTP’s control, most significantly, the Havana peace process. However, a more assertive approach toward the government by the OTP, including in the media, and more effective alliances with international partners, might have strengthened its influence.

In Georgia, the OTP’s approach was less interventionist. It engaged extensively with national authorities as part of its assessment of domestic proceedings and to avoid manipulation of the ICC’s mandate, rather than to encourage these proceedings per se. While existence of the preliminary examination and the OTP’s regular engagement with authorities in Georgia appears to have spurred a certain amount of investigative activity, ultimately, this was insufficient to support effective national proceedings, which led to the ICC’s decision to open an investigation. A number of factors limited the OTP’s influence on national accountability efforts, in part because of very limited political will by the government to see national accountability. But strengthened engagement between the OTP and other relevant actors, including media, civil society groups, and international partners may have expedited the OTP’s assessment of its own jurisdiction, leading to an earlier decision to seek to open investigations.

In the UK, the OTP reopened its preliminary examination during a dynamic and charged period concerning the broader allegations of abuse by British forces in Iraq. During the period of our research, the OTP had yet to take a proactive approach to complementarity. Not surprisingly then, and against the broader background of developments around accountability, our research indicates that the ICC’s involvement so far has not per se instigated or influenced national proceedings in significant ways. Instead, to the extent there has been progress in criminal investigations, it is largely attributable to domestic litigation that predated the ICC examination. At the same time, by subjecting existing domestic efforts to another level of scrutiny, the ICC prosecutor’s examination may have discouraged British authorities from discontinuing relevant inquiries into potential abuses by British armed forces in Iraq despite public pressure for them to do so.

Contextual Factors

The case studies make clear that context will influence the likelihood of successful positive complementarity activities by the OTP. Our research suggests four contextual factors are particularly important.

First, and most significantly, the extent of opposition to accountability by powerful interests in the country will constrain the OTP’s influence. The lack of full political support for accountability—regardless of stated intention by governments—was a constant across these case studies. In the UK, there seems to be general sentiment to see accountability for politicians for their decision to go to war in Iraq and the ensuing aftermath—an issue not within the ICC’s jurisdiction—but not necessarily military officials and rank-and-file soldiers.

But the exact landscape that conditions political will for prosecutions differs.[6] In all four countries, some or all the alleged perpetrators are or were government agents at certain points during the commission of alleged abuses or during the preliminary examination; where governments have changed, new governments have not necessarily considered prosecutions of former government officials to be in their political interest.

The influence of the armed forces in each of these countries has also been significant. In Colombia, the peace process has been a significant factor shaping government responses in ways that have both contributed to justice and detracted from it, while the relationship between Georgia and Russia in the aftermath of the 2008 conflict and the regional security context has affected decisions regarding prosecution across two successive governments there.

Second, where the underlying crime basis is more limited, as in Guinea where allegations relate to a horrific, but time-bound incident, the OTP has been able to identify specific benchmarks with prosecuting authorities, which, in turn, has helped to push forward incremental progress. In Colombia, the OTP has indicated that it is more challenging to use this approach given the broad temporal, geographical, and subject matter scope of the underlying crimes.

Third, where public demand and interest in accountability is high, it opens the possibility for the OTP to amplify the advocacy of key domestic actors, including representatives of civil society, or vice versa, as well as to benefit from the media as a pressure point on governments. In Guinea, victims’ associations have participated as civil parties in the domestic investigations, and exchanges between the OTP and these associations assisted the OTP in assessing progress in national investigations. In Colombia, too, domestic civil society organizations have relied on the OTP’s reporting on the underlying crimes and the status of national proceedings in their own advocacy, and OTP statements garner widespread media coverage. In the UK, hostility to allegations against service members and the lawyers who brought these allegations has created a difficult terrain for accountability.

Fourth, OTP efforts are likely to have more traction where other international partners are also promoting accountability. In Guinea and Colombia, the OTP has been one of several international actors on justice, while in Georgia, we found little evidence that other potential partners, including diplomatic missions, regional organizations, and UN agencies made it a priority to engage domestic authorities on the importance of accountability for relevant cases.

It is unlikely that the OTP, on its own, can fundamentally alter political dynamics. And while it may have more success in influencing other actors beyond the government—among civil society and in the international community—to join its efforts to press governments to make justice a priority, even this effect is uncertain (see discussion of strategic alliances below). This suggests that the OTP’s current approach—to defer to national proceedings where there is at least a stated government intention to proceed, but to carefully calibrate whether and how actively to encourage such proceedings depending on its assessment of the likeliness of genuine proceedings—appropriately recognizes certain inherent limits.

As a result, the OTP’s approach has and is likely to continue to differ from one situation to the next. In one situation, the OTP may prolong its deference to national authorities because it considers genuine proceedings may yet materialize, while in another situation, it may not afford national authorities an equivalent space.

To get this balance right, the OTP’s complementarity strategies need to be rooted in a deep appreciation of context. The OTP should be able to understand the domestic and, where relevant, regional political landscape, and build contacts within government, prosecuting authorities, civil society, and the national and international media. In Guinea, our research suggests that the frequency of visits by the OTP to the country helps to explain how, over a number of years during which investigations were at times stalled, they nonetheless managed the situation in a manner that contributed to incremental progress. Building this deep understanding will take resources—staff resources within the OTP, as well as resources for mission travel.

There is also a credibility risk inherent in inconsistent treatment between situations.[7] Transparency, discussed further below, can help to mitigate these risks.

D. Conclusions and Recommendations

While expectations about the OTP’s influence should be realistic, the four case studies in this report also have lessons for strengthening the OTP’s complementarity specific approaches to increase impact in the future.

1. OTP Should Make More of Its Unique Leverage to Catalyze Political Will

Across the cases studies, the key obstacle to further progress in national prosecutions was an absence of political will by officials to support cases. Where the OTP did engage to address capacity challenges—the development of prosecutorial strategies in Colombia and encouraging assistance from the Team of Experts for Rule of Law/Sexual Violence in Conflict in the UN Office of the Special Representative on Sexual Violence in Conflict in Guinea—it was successful.

This suggests that the OTP can be well-positioned to broker assistance, but that catalyzing political will is likely to be a more significant part of its strategies to encourage national proceedings.

When it comes to catalyzing political will, the OTP’s leverage with national authorities appeared to depend on the level of concern these authorities had regarding the prospect of an ICC investigation. The OTP appears to have had its greatest influence in Guinea, where interviewees indicated that the president was concerned that the country be seen as capable of conducting investigations, both as part of its transition from an autocratic to a democratic government and against the backdrop of strong criticism regarding the ICC from some African leaders, particularly in eastern Africa.

In comparison, in Colombia, Georgia, and the UK, interviewees indicated only a limited concern on the part of national authorities regarding the prospect of an ICC investigation. In Colombia, we found little evidence that prosecuting authorities (as compared to the military) believed the ICC would ever open an investigation. In the UK, interviewees described a palpable confidence on the part of British authorities vis-à-vis the unlikelihood of a formal ICC probe. And in Georgia, successive governments simply stopped being concerned about ICC involvement once it became clear that it could not simply be manipulated (either to prosecute alleged Russian abuses or, once the opposition came to power, former Georgian officials).

This suggests that the most productive posture of the OTP vis-à-vis national authorities when it comes to encouraging national proceedings is as a “sword of Damocles,” that is, as a threat and source of strong pressure.[8] Where authorities simply do not care about ICC intervention, it will be difficult for the OTP to change this perspective. But where a lack of concern stems from the belief that ICC investigations are little more than a remote possibility, this suggests that the OTP should do what it can to counter those perceptions.

Current OTP practice places it in a good position to do so. In the past, threats of ICC action may have seemed like empty gestures; now, however, as, discussed in Appendix I, the OTP’s increased public reporting on preliminary examinations and its decision to defer active strategies to encourage national proceedings until it is certain of its own jurisdiction should reinforce the credibility of potential ICC action. The OTP’s identification of potential cases to national authorities and the public through its reports also serves to make clear the OTP’s intent to proceed if authorities do not.[9]

To strengthen pressure, however, the OTP will need at times to take a more confrontational approach with authorities. This is especially important given the potential manipulation by national authorities of the court’s statutory framework.

When it comes to article 15 proprio motu investigations, the OTP needs to satisfy the court’s judges that there are no national proceedings that would render potential cases inadmissible.[10] Efforts by the OTP to stimulate national proceedings can produce domestic activity that will make it more difficult for the OTP to meet this burden. Where that activity leads to genuine national proceedings this is positive. But there is an equal risk of domestic authorities producing a certain amount of activity—opening of case files and limited investigative steps—to stave off ICC intervention, but without following through with prosecutions. The judges’ remit to look at the admissibility of potential cases means that there is a wide scope of national investigative activity that could be deemed to render ICC action impermissible.[11]

In this scenario, the preliminary examination period may be manipulated by national authorities, leaving it in limbo: too much domestic activity to be certain ICC judges will find OTP action permissible, but too little domestic activity to close out the preliminary examination in deference to genuine national proceedings. The result could be delayed ICC action where it is ultimately needed, increasing the challenges to investigating long after crimes are committed, and deferring the access of victims to justice. The Georgia case study exemplifies this risk.

The OTP needs to carefully determine when deferring to national authorities and deploying positive complementarity strategies is the right choice, and when this will only delay ICC action without any reasonable prospect of national justice. Getting that call right and avoiding instrumentalization is perhaps the OTP’s paramount challenge.

OTP Steps to Strengthen Its Hand

The OTP can take certain steps to strengthen its hand with national authorities.

First, it should sharpen up its private and public engagement. In Colombia, former and current government officials indicated that the OTP’s manner of engagement failed to convince them of any serious prospect that an investigation would be opened, even without further progress in national proceedings.

Second, the OTP needs to be able to verify information provided to it by government authorities. The OTP, among other steps it takes to verify information directly with authorities, can benefit from alternative sources of information. The OTP can assist civil society efforts to obtain this information by pressing governments on the importance of transparency.

Third, the OTP should also consider publicly identifying benchmarks for national authorities in more situations.[12] Of these four case studies, it has only publicly referenced particular steps that are needed in an investigation in Guinea. While the scope of crimes and relevant national proceedings in other situations may limit its ability to replicate the approach in Guinea, the use of benchmarks stimulated national authorities to take specific steps. It would also allow the OTP to identify where such steps are not being taken, and where, perhaps, the time for deference to national proceedings has ended.

Finally, making these benchmarks public can serve to underscore the seriousness with which the OTP is approaching positive complementarity. More generally, transparency regarding the OTP’s analysis of domestic proceedings is key. Where the OTP is, and is seen to be, engaging national authorities in a strong manner to encourage national proceedings, other actors, particularly in civil society and among a country’s international donors, as relevant, can complement its efforts to hold the government to account to taking additional steps.

As indicated below, catalyzing these strategic alliances may not always be possible. But in the absence of this transparency, lengthy periods of preliminary examination can appear to local civil society and other key stakeholders as little more than a stalling tactic by the OTP, undermining the willingness of these actors to act as strategic partners.

2. Expedite Analysis to Get to Complementarity Activities Earlier

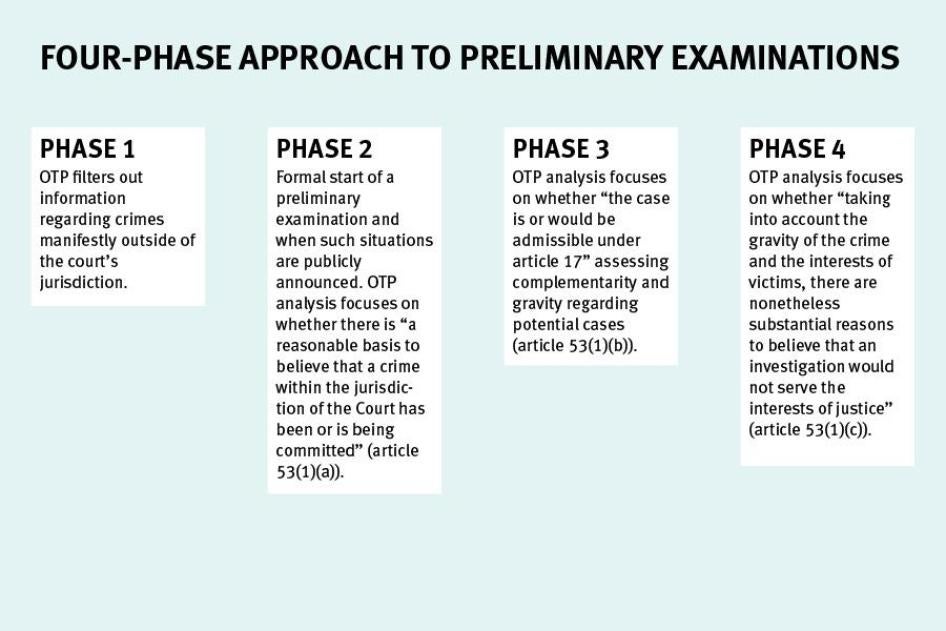

An important change in OTP practice has been to defer in general active encouragement of national proceedings until Phase 3 of its analysis, that is, until after it has determined that there are potential cases which, absent genuine national proceedings, could be the subject of ICC investigations and prosecutions. Of the case studies in this report, only the UK reflects this new approach, although aspects of the approach—in particular, engaging national authorities around proceedings relevant to the specific, potential cases it has identified—have also been used in the three other case studies.

This is a positive shift, and one that appears to have been driven by clarity in the court’s case law that admissibility at the situation phase will be determined with regard to potential cases. It strengthens the credibility of OTP pressure on national authorities given that it can be confident that it could act, should national authorities fail to do so. It avoids the OTP making public statements that go beyond the state of its analysis, which could undermine the credibility of its analysis and lessen its leverage. And it permits the OTP to engage with national authorities around the specific cases it has identified, which, in the experience of the OTP, as noted in Appendix I, has strengthened the level of engagement it can have with authorities.[13]

Our research suggests that opportunity costs to delaying positive complementarity efforts to Phase 3 may be more limited than expected. This is because the opening of a preliminary examination and the activities that are otherwise necessary to conduct that examination—as distinct from specific strategies to encourage national proceedings—may have their own effect.

In Guinea, the opening of the preliminary examination led within weeks to the initiation of a domestic investigation. In Colombia, Georgia, and the UK, while relevant investigations had already been initiated prior to the opening of the preliminary examination (or, in the case of the UK, the reopening of the preliminary examination; there was no discernable effect of the first preliminary examination on domestic proceedings) observers suggested that the fact that the OTP was monitoring domestic proceedings and requesting information regarding these proceedings contributed to sustaining some pressure on national authorities to act, including, in some countries, by keeping the need for accountability on the radar of the government, civil society, and international partners.

At the same time, however, deferring an active approach to positive complementarity for too long does have costs.

Costs of Deferring Active Approach to Positive Complementarity

The ICC’s legal texts do not prescribe any timeline for taking decisions regarding preliminary examinations. The absence of timelines can provide a helpful flexibility to the OTP, when it comes to carrying out its analysis, as well as implementing its policy commitment to encourage domestic proceedings; the time necessary to catalyze national proceedings is likely to vary greatly depending on context.[14] However, the Colombia case study (and, to a certain extent, the Georgia case study) suggest that with the passage of time, and inaction by the OTP, national authorities may grow increasingly less concerned about the prospect of an ICC intervention.

Keeping situations under analysis for several years has also undermined the OTP’s credibility in some affected communities; this was apparent in our case studies of Colombia, Guinea, and Georgia. The OTP’s ability to influence national authorities can be amplified through alliances with civil society groups, which can be undermined where NGOs lose confidence in the OTP’s process.

Given what are otherwise clear benefits to delaying positive complementarity activities until Phase 3, we recommend that the OTP seek to advance through Phase 2 as quickly as possible. This will limit delay in engaging national authorities, while preserving the benefits of the OTP being able to engage with these authorities around specific cases with a clear view toward ICC action if national proceedings do not materialize.

To do so, the OTP should consider its approach to staffing. It may be important to frontload resources on a given preliminary examination in order to analyze and verify communications, while then shifting staff to assess admissibility, and where appropriate, encourage complementarity in Phase 3.

3. Critical Importance of Strategic Alliances

In each of the case studies, we sought to understand the OTP’s engagement with other actors who could play a role regarding positive complementarity. These include representatives of a country’s international donors and UN agencies, who through political dialogue or capacity building could support justice efforts, and civil society activists engaged in advocacy or capacity building with governments regarding justice.

Unsurprisingly, the OTP had more influence where its efforts were amplified by others, or where it contributed to amplifying the efforts of others. Guinea, again, stands out. The OTP, the UN Office of the Special Representative on Sexual Violence, and victims’ associations have served as strategic allies, mutually reinforcing each other’s efforts when it comes to justice for the September 2009 stadium massacre. In Georgia, by contrast, the OTP had few such partnerships.

The OTP cannot be expected to single-handedly transform the national accountability landscape. Particularly where there are powerful political interests arranged against justice, the OTP needs to have the backing of other influential partners to catalyze political will.

Our research, however, is inconclusive when it comes to the question of whether the OTP can stimulate others to act. In Guinea, the engagement of some actors happened independently from any OTP efforts, while in other instances, OTP efforts to press for progress on the investigation had limited effect. In particular, donors remained far more focused on security issues despite outreach by the OTP. In Colombia, the OTP has been one of a number of actors on justice, but the engagement of these other actors does not appear to have been catalyzed by the OTP. In Georgia, the OTP did make some limited efforts to interest international partners, but these partners seemed more concerned by regional security in the aftermath of the conflict, and uninterested in prioritizing justice.

This seems equally true for international partners as it does for civil society groups. Local groups in all four case studies, albeit to varying degrees, have viewed the OTP’s approach critically. For the most part, NGOs tended to see the OTP’s engagement as delaying justice, which they feel can best be achieved through ICC prosecutions; that is, by giving the authorities space to act, and deferring ICC action, the OTP is prolonging the timeline for justice.

This can dim the willingness of local groups to see the OTP as an ally in advocacy with national authorities. In Guinea, even with some positive progress in investigations, some civil society groups have been quite critical of the OTP, although other groups are more supportive of its work; this has also been the case in Colombia, where there has been a persistent fear that the OTP will simply close the examination and walk away.[15]

The OTP should increase its outreach and support to potential partners with a view toward encouraging them to reinforce the OTP’s own efforts. The need to respect confidentiality places real limits on what information the OTP can share. But within these limits, civil society activists indicated that more information about the OTP’s analyses is desirable, and could help contribute to increased advocacy by civil society groups on national justice.

In Georgia, civil society groups had limited access to the details of investigations. There, the OTP could have helped bridge the gap between civil society and the government by pressing government officials to provide more information about investigations, and in doing so, help NGOs become a more strategic partner in evaluating progress—or lack thereof—in investigations. In the UK, the OTP has had limited engagement with civil society, beyond the senders of the article 15 communications that led to the opening of the examination.

In view of the limits to what such outreach to partners may accomplish, and bearing in mind the OTP’s limited resources, international donors should also initiate activities to support positive complementarity as warranted in situations under analysis. This would provide the OTP with an immediate complement of potential partners, and does not already appear to be routinely the case.

In Georgia, for example, the European Union created a budget line to support cooperation with the ICC only after the opening of the investigation. We recognize that budgets are often determined far in advance, and it may be difficult to immediately react to the opening of a preliminary examination. But the use of discretionary funds can help to fill gaps until such time as the preliminary examination can be accounted for in budgeting. A general policy by international donors to support credible complementarity initiatives where international crimes have been committed, regardless of whether a preliminary examination has been opened, would also help to ensure the availability of strategic allies where the OTP does act.

It is critical, however, that the OTP maintain strong relationships across a range of stakeholders during preliminary examinations, regardless of the potential benefit to national justice efforts. This is needed to check information provided by government sources when it comes to advancing the OTP’s analysis. It is also necessary for the court’s transparency as an element of the sound administration of justice, when it comes to victims, civil society representatives, the general public, and ICC states parties. Where it becomes necessary for the ICC to open its own investigation, as was ultimately the case in Georgia, these relationships, particularly with civil society, are vital to support the work of the court.

4. Increased Transparency Key

Throughout these conclusions, we have highlighted where increased transparency of the OTP’s analysis and activities during preliminary examinations—particularly through effective use of relevant media—can further positive complementarity.

This includes:

· publicity aimed at stimulating interest in accountability among the general public, civil society, and international donors to build and sustain conditions favorable to justice and strategic alliances to reinforce OTP efforts;

· publicity as a source of pressure on national authorities, including by publicly benchmarking investigative and prosecutorial steps to more credibly assert the OTP’s leverage; and

· publicity that equips strategic allies with information regarding the status of domestic proceedings, which can strengthen their advocacy with the government and lead to the OTP receiving information that verifies or disputes this account.

The latter can be key to the OTP’s ability to adapt its strategies, that is, either seeking to increase pressure or determining that national proceedings are unlikely such that it should seek to open its own investigation, thereby avoiding obstruction by national authorities.

In addition, the OTP’s efforts on positive complementarity will need to be adapted to context, leading to the perception of inconsistent treatment across different situations, which can undermine the OTP’s credibility, its leverage with national authorities, and alliances with strategic partners. As highlighted above, transparency in the OTP’s preliminary examinations can help to explain its decision making in a manner that mitigates these risks.

Finally, transparency has an independent value apart from its effect on national justice, in that it is a component of the sound administration of justice, and accountability to the court’s key stakeholders, including victims, civil society groups, national authorities in situations under preliminary examination, and ICC states parties, more broadly.

Despite increased reporting since 2011, including annual reports on preliminary examinations and situation-specific reports as preliminary examinations have moved between phases, the OTP’s overall approach to publicity remains cautious. Although Guinea stands out as a clear exception—with the OTP making effective use of local media during its visits and responding to some media requests from The Hague—in the three other case studies, the OTP has limited its engagement with the local media. In Georgia, the OTP also limited contact with international media, which may have provided greater opportunities than the local media.

The OTP should put in place clear communications strategies for each situation under analysis.[16] Two elements will be particularly important to effective strategies.

First, publicity by the OTP should aim to make its analysis as accessible and as straightforward as possible. Constructive ambiguity in the OTP’s statements has weakened their effect, and added little to transparency. When it comes to the OTP’s annual preliminary examination reports, we found that there was a more limited positive effect of these reports than we had predicted; that is, few actors pointed to the utility of these reports when it came to strengthening their own advocacy. But these reports nonetheless play an important, different role: they provide a check on the OTP’s assessment by forcing regular transparency.

The OTP should continue its efforts to enhance reporting, including by developing communications strategies around the release of the annual report in each situation under preliminary examination to ensure findings reach authorities, civil society groups, and media in these countries. While our informal observation indicates that these reports have received increased media attention in recent years, there is still scope for going further.

The OTP should also consider formalizing the procedure with which it engages with the senders of the communications. This could include providing them with a sense of responses received from relevant government bodies, and identifying to them information that the OTP needs for the next phase of its analysis.

Second, certain situations will present highly complex media landscapes. On these landscapes, the OTP will need to have a deep knowledge, as well as deep contacts within media in order to facilitate a productive use of publicity. In the UK and in Colombia, media coverage of the ICC has not necessarily been productive, when it comes to national justice; this is particularly true in the UK, where coverage of allegations of abuse has been part of a politically charged landscape. In our experience, however, there would be scope for the OTP to more effectively engage with media in both countries.

In addition, governments should consider making available public versions of reports provided to the OTP. If governments are willing to do so, it would remove concerns about confidentiality from decisions on transparency.

* * *

Implementing these recommendations would in our view strengthen the OTP’s impact on national justice. But doing so will also depend on the availability of greater resources; the OTP’s resources on preliminary examinations are too limited (see Appendix I).

At the same time, our case studies suggest that it is important not to overstate the prospects for success. It is likely to be the case that most preliminary examinations that proceed beyond OTP determinations that there are potential cases over which the court could exercise jurisdiction will result in the need to open ICC investigations, given the many persistent and stubborn obstacles to national justice, particularly when it comes to holding to account high-level perpetrators. This poses a real challenge to the ICC, which faces a significant capacity crisis; demand for ICC action continues to outpace the resources it has available.

Methodology

This report builds on Human Rights Watch’s 2011 report, Course Correction: Recommendations to the Prosecutor for a More Effective Approach to “Situations under Analysis.”[17]

It is based on research conducted between June and November 2012 and September 2015 and December 2017, primarily interviews with key stakeholders who had knowledge of the OTP’s preliminary examination activities in each of the four country case studies: Colombia, Georgia, Guinea, and the United Kingdom. These stakeholders included government officials in ministries of foreign affairs, justice, and defense; national investigating and prosecuting authorities; judges; members of civil society groups; journalists; and representatives of diplomatic missions and UN agencies. These interviews and other research steps specific to each case study are described below.

Human Rights Watch also conducted 12 interviews in person and by telephone with staff members of the OTP. Human Rights Watch provided the OTP with a draft report for comments and corrections, which are reflected in the published report.

Human Rights Watch also consulted ICC case law, policy statements, news releases, and reports on preliminary examination activities issued by the OTP. We relied on our ongoing monitoring of the ICC’s institutional development and practice across its situations under analysis.

We conducted a limited literature review of existing publications on the Office of the Prosecutor’s positive complementarity activities during preliminary examination. Press reviews of media coverage of the OTP’s preliminary examination activities were conducted for the Colombia, Guinea, and UK chapters, using Factiva and the Google search engine, as well as a search of the websites of specific Guinean media outlets. In Georgia, a number of knowledgeable sources considered media coverage of the OTP’s activities to be very limited, so we did not conduct a press review. Whenever possible, secondary sources, such as reports by nongovernmental organizations and news articles, were used to corroborate information provided during interviews.

The four case studies were selected from current situations under preliminary examination before the ICC on the basis of a number of criteria. (The Georgia situation moved from preliminary examination to investigation shortly after this project began.) Criteria included Human Rights Watch’s assessment that in each situation, certain prospects for national justice existed or had existed, such that it was reasonable to expect the OTP to have some impact; geographical diversity; existing Human Rights Watch expertise and research in the country, either on relevant human rights violations or on the status of national proceedings; and the feasibility of carrying out research given resources and staffing.

We have used generic descriptions of interviewees throughout the report instead of actual names. Some interviewees wished to retain their anonymity given the sensitivity of the issues they discussed while others might have been at increased risk had their names been used. In some instances, the location where the interview was conducted is withheld to protect the identity of the source.

All participants were informed of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and the ways in which the information would be used. Interviews generally lasted between one and two hours. Interviewees did not receive any compensation for participating in interviews, but some interviewees in Guinea were reimbursed for transportation costs to and from the interview.

Colombia

The Colombia chapter is based primarily on information gathered during research trips to Bogotá and Medellín by Human Rights Watch in June, August, and September 2016. In Bogotá, Human Rights Watch staff interviewed 36 people, including former or current government officials in the ministries of justice and defense and the Attorney General’s Office; former or current judges within the Constitutional Court and Supreme Court; and Colombian civil society representatives. Additional interviews were conducted in person or by phone between June and December 2016, including with staff of the OTP in The Hague. Most of the interviews were conducted in Spanish. Human Rights Watch also had access to two confidential memos expressing the views of the Attorney General’s Office regarding cooperation with the OTP and the consistency of Colombian legislation with the Rome Statute.

Georgia

The Georgia chapter of the report is based primarily on information gathered during a research trip to Tbilisi conducted by Human Rights Watch in December 2015. In Tbilisi, Human Rights Watch staff interviewed 18 people, including former and current government officials in the ministries of justice and defense; civil society representatives; diplomats; journalists; and donor officials. Additional interviews were conducted in person, by telephone, or over email between December 2015 and September 2016, including with staff of the OTP. Interviews were conducted in English.

Guinea

This chapter is based on research conducted between June 2012 and June 2016. Research trips were conducted in Conakry, Guinea in June 2012 and March 2016. The first research trip was originally conducted for the December 2012 Human Rights Watch report, Waiting for Justice: Accountability before Guinea’s Courts for the September 8, 2009 Stadium Massacre, Rapes, and Other Abuses.

Human Rights Watch researchers conducted interviews with approximately 25 individuals during the 2012 research trip and 35 during the 2016 research trip. Both individual and group interviews were conducted. Interviewees during both research trips included officials and staff in the Justice Ministry; justice practitioners, including judges, prosecutors, private lawyers, and legal support staff; representatives of international partners, including government and intergovernmental donor and United Nations officials; Guinean and international NGO members; local journalists; and victims of abuses.

Between July and November 2012 and November 2015 and June 2016, Human Rights Watch staff conducted additional interviews in French and English with UN officials, Western and African diplomats, ICC officials, and Guinean government officials in New York and The Hague, and by telephone. Most of the interviews were conducted in French, and a small number in English.

United Kingdom

This chapter is based primarily on information gathered during Human Rights Watch research in London, Berlin and The Hague between November 2015 and July 2017. Human Rights Watch staff spoke to 23 individuals either in-person or by telephone, including journalists, barristers, solicitors, international criminal law experts, former and current government officials, parliamentarians, civil society representatives, and staff at the OTP. Interviews were conducted in English.

Human Rights Watch also reviewed a range of publicly available documents, including ICC reports and policy papers, European Court of Human Rights judgments, domestic judicial decisions, public and judicial inquiry reports, relevant NGO reports, government statements and reports, and British press articles.

I. Colombia

A. Overview

Colombia has endured over 50 years of armed conflict between government forces and non-state armed groups. During the conflict, military personnel and other state agents, paramilitary groups, and guerrillas—notably the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the National Liberation Army (ELN)—have committed thousands of grave international crimes.[18]

Colombia ratified the Rome Statute on August 5, 2002, and the Office of the Prosecutor (OTP) of the International Criminal Court (ICC) opened its preliminary examination in Colombia—its longest running preliminary examination at time of writing— in June 2004, although its work was not made public until 2006.[19]

This chapter assesses whether the OTP has catalyzed domestic prosecutions in Colombia regarding the systematic extrajudicial executions of civilians committed by army brigades between 2002 and 2008 in cases known as “false positive” killings.

“False positive” killings are only one of the OTP’s five areas of focus.[20] However, given the breadth of alleged crimes committed in Colombia that could fall within the ICC’s jurisdiction, the scope of relevant domestic proceedings, the long-lasting nature of the OTP’s preliminary examination in Colombia, and the fact that justice for these killings has been a specific focus of Human Rights Watch’s work since 2011, we have chosen to limit our analysis to the issue of “false positive” killings.

The chapter does not include an assessment of the OTP’s engagement around the Agreement on the Victims of the Conflict, reached by the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) guerrillas in December 2015 as part of their peace talks.[21] The agreement has bearing on “false positive” cases, given that many such cases likely will be transferred to the “Special Jurisdiction for Peace” established by the agreement. The tribunal, however, was not operational at time of writing this report. Human Rights Watch has expressed concerns that problems in the agreement and in proposed implementing legislation could undermine meaningful prosecution of “false positive” killings before the tribunal.[22]

Our research indicates that the OTP’s engagement on “false positive” killings has had mixed results. Authorities have carried out investigations and prosecutions of hundreds of low-level soldiers in “false positive” cases, and sources interviewed for this report suggested the OTP has been one of several important actors in keeping the need for accountability in these cases on the agenda. The OTP worked effectively to counter at least one legislative proposal that might have undermined these prosecutions and its engagement positively affected the development of relevant prosecutorial strategies.

But its engagement has had a limited influence in the face of the main obstacle to prosecution of high-level officials: lack of unequivocal political will to support these prosecutions. This is perhaps unsurprising. The prosecution of senior level officials by a state in the absence of regime change presents one of the most significant tests of the complementarity principle.

In addition, as discussed below, the Havana peace process between the Colombian government and FARC guerrillas significantly limited the OTP’s influence with regard to advancing national prosecutions of “false positive” killings. Windows of opportunity for a more confrontational approach by the OTP closed as the peace process advanced, lest the OTP be perceived as a spoiler of the peace.

Below, we first describe progress in domestic prosecutions of “false positive” killings and analyze the main obstacles to further progress. We then summarize the OTP’s engagement regarding “false positives” since 2008 and assess whether and to what extent the OTP has catalyzed justice in “false positive” killings, regarding three specific areas: legislation, prosecutorial policies, and individual prosecutions. Finally, we assess whether the OTP has strengthened its leverage with the Colombian government by building strategic alliances with key partners, including local civil society and international partners, and through effective engagement with media.

B. National Prosecutions of “False Positive” Killings

Between 2002 and 2008, army brigades across Colombia routinely executed civilians. Under pressure from superiors to show “positive” results and boost body counts in their war against guerrillas, military units abducted primarily young men or lured them to remote locations under false pretenses—such as promises of work—killed them, placed weapons on their bodies, and then reported them as enemy combatants killed in action.[23]

Committed on a large scale for more than half a decade, these “false positive” killings constitute one of the worst episodes of mass atrocity in the Western Hemisphere in recent decades. They were war crimes and might amount to crimes against humanity under the Rome Statute.[24]

According to Human Rights Watch’s research, significant evidence indicates that numerous senior army officers, including officers who subsequently rose to the top of the military command, bear responsibility for “false positive” killings. Our research suggests that some of them may at least be criminally liable as a matter of command responsibility in that they knew, or should have known, “false positive” killings were taking place and yet failed to prevent or punish the conduct.[25]

1. Status of National Prosecutions

In September 2008, a scandal broke out over the disappearance of at least 16 young men and teenage boys from Soacha, a low-income Bogotá suburb. Their bodies were found in the distant northeastern province of Norte de Santander. The military—initially backed by then-President Alvaro Uribe—claimed they were combat deaths, but it soon came to light that they were victims of “false positive" killings.[26] The Soacha scandal helped force the government to take serious measures to stop the crimes and to publicly admit allegations of “false positive” killings that human rights monitors had raised for several years.[27]

The Attorney General’s Office had carried out some investigations on “false positive” killings before the Soacha scandal, despite the government’s reluctance to admit crimes were taking place in a widespread manner.[28] Investigations began in 2007, and resulted in first convictions around 2009.[29] Since then, Colombian authorities have made significant progress in prosecuting members of the army responsible for “false positive” killings.[30]

As of March 2018, the Colombian Attorney General’s Office was investigating 2,198 cases of extrajudicial executions committed between 2002 and 2008 and had convicted over 1,600 state agents in 268 cases.[31]

While in recent years there have been some meaningful steps forward in prosecuting top commanders, progress has been slow. Out of all of these cases, at least 11 army colonels have been convicted and one retired army general has been charged.

Until June 2015—almost seven years after the Soacha scandal—no prosecutorial steps had been taken against active or retired generals implicated in “false positive” killings. In that month, four active or retired generals were summoned for questioning (interrogatorio) and a “spontaneous declaration” before a prosecutor (version libre)—both steps being the very first in criminal investigations under the two relevant codes of criminal procedure.[32]

The generals included former army top commander Mario Montoya Uribe. As of March 2018, 11 had been called into questioning.[33] At time of writing, other prosecutorial steps had been taken regarding three of the 11: the investigation against one retired general was closed due to lack of evidence, one retired general has been charged and indicted, and one investigation against an active general was closed due to lack of evidence, although he remains under investigation for another case.[34] In March 2016, prosecutors announced that they would summon Montoya Uribe for a hearing where he would be charged, but such hearing had not taken place at time of writing.[35]

2. Obstacles to Accountability at Senior Levels for “False Positive” Killings

Human Rights Watch has previously identified several obstacles to accountability for “false positive” killings. These include (a) use of an incident-based approach instead of prosecutorial strategies aimed at uncovering patterns that could lead to establishing accountability at more senior levels; (b) limited resources allocated to these cases; (c) lack of military cooperation with civilian investigations, with many “false positive” killings pending before military instead of civilian courts; and (d) reprisals against witnesses.[36]

This section focuses on what appear to be the two key obstacles for accountability at senior levels for “false positive” killings: inconstant political will to move forward with these prosecutions, and use of an incident-based approach—as opposed to strategies aimed at uncovering patterns that might be indicative of the responsibility of more senior officials.

Political Will: Mixed Signals

Authorities in the Colombian government have sent mixed signals regarding the political will necessary to support prosecuting those most responsible for “false positive” killings.

During the Uribe administration (2002-2010), the government repeatedly denied that “false positives” were a systemic problem and accused the human rights defenders who were reporting these killings of colluding with guerrillas to discredit the military.[37] The government took the position that those responsible for allegedly isolated events would be held accountable,[38] although in fact criticized prosecutions.[39] In 2008, the government dismissed 27 army officials, including three generals, following the Soacha scandal.[40]

In 2010, Juan Manuel Santos, President Uribe’s defense minister between 2006 and 2009, won the national elections. His administration has committed publicly to hold to account those responsible for “false positives.”[41] At the same time, it has promoted several pieces of legislation that would open the door to impunity for these crimes, including the Legal Framework for Peace and numerous bills that would transfer extrajudicial killings, including “false positive” killings, to military jurisdiction. These legislative developments and the OTP’s influence with regard to them are discussed further in Part D.

A key reason behind these mixed signals on accountability during the Santos’ administration is the peace process with the FARC guerrillas, which formally began in October 2012, and the government’s attempts to obtain military support for the process.[42]

For example, a former official from the Attorney General’s Office told Human Rights Watch that authorities thought that progress in prosecuting top army commanders would undermine the army’s support for the peace process when a final accord was reached.[43] Similarly, a former Defense Ministry official noted that some legislative proposals the ministry submitted, including one on military jurisdiction, were meant to convey that military personnel would not be subject to harsher prosecutions than the guerrillas negotiating peace.[44]

However, the peace process at times apparently created the opposite incentive by actually helping prosecutions move forward. Some interviewees noted that at times the Attorney General’s Office may have advanced “false positive” cases to send a message to the international community—such as the US government and the Inter-American human rights system—that peace negotiations would not reinforce impunity for army members and, perhaps more critically, to avoid an ICC intervention that could risk the peace talks.[45]

In fact, an ICC investigation would mean that Colombian authorities would lose control of their prosecutions of army officers and, thus, key leverage to gain the army’s support for the peace deal. This also suggests that, independently of any specific strategies pressed by the OTP on positive complementarity, Colombia’s membership in the ICC has been a positive point of pressure, avoiding worse outcomes on justice.

Incident-Based Prosecutions

Another key obstacle to holding more senior officials accountable has been the fact that prosecutions in Colombia have long been incident-based, while failing to investigate broader patterns of abuses—which is necessary to determine responsibility beyond military personnel directly involved in carrying out “false positive” killings.

Between 2012 and 2015, then-Attorney General Eduardo Montealegre adopted prosecutorial policies that helped address this shortcoming, including by designing a prioritization scheme and creating a unit to carry out a context-based analysis of crimes, the Unit of Analysis and Context (UNAC, later called Direction of Analysis and Context, DINAC).[46] However, implementation of these strategies to prosecute “false positives” has been limited or slow, as discussed in Section D.

C. OTP Approach to Positive Complementarity and Cooperation Challenges

Domestic proceedings on a range of crimes that could amount to war crimes or crimes against humanity—even though they have often been prosecuted as ordinary crimes and did not include “false positive” killings—pre-dated the beginning of OTP involvement in Colombia in 2004.

Therefore, the OTP’s strategy was to encourage Colombian authorities to address crimes it believed were relevant to the ICC’s jurisdiction, while monitoring implementation of the 2005 Justice and Peace Law, which allowed demobilized members of paramilitary death squads to receive reduced sentences of up to eight years in exchange for confessions.[47]

The OTP’s work on “false positives” started in 2008, shortly after the Soacha scandal.[48] However, until 2012, the OTP’s engagement with Colombian authorities regarding the issue had been limited. Although the OTP closely monitored the developing Soacha scandal in 2008, and continued to analyze information obtained through open sources, including with regard to national proceedings, it had limited and informal engagement with national authorities.

The OTP first referred to “false positives” in its public statements only in 2010 (its practice of issuing what are now annual reports on its preliminary examinations began in 2011).[49] In addition, resources within the OTP—already severely limited when it came to preliminary examinations—were diverted to other situations under analysis after 2008. There was no analyst officially in charge of the Colombia work between November 2010 and August 2011.

Human Rights Watch was unable to identify interviewees who could speak with first-hand knowledge about the engagement between the OTP and Colombian authorities in the earliest phases of the prosecution’s preliminary examination. As a result, this chapter primarily concerns the period from 2012. This means that we have been unable to comprehensively assess the possible effect of OTP monitoring and limited engagement with national authorities on national prosecutions for “false positive” cases between 2008-2012. This period may have had important opportunities for influence, given our conclusion (see below) that the start of the peace process in 2012 was a significant limitation.

In 2012, the OTP gave renewed attention to the international crimes committed in Colombia and the national efforts to bring those responsible to justice.[50] An OTP official told Human Rights Watch that prosecutor Moreno Ocampo considered making a final determination regarding the preliminary examination near the end of his mandate, in 2012.[51]

At the time, and since 2008, the OTP was working on an “interim report” on the situation. The report, published in November 2012, was, according to one interlocutor, originally aimed at easing complaints from local civil society groups that the OTP was not doing enough in Colombia.[52] It resulted in an important new form of engagement.

The report is seen by the OTP as an important tool in its strategy to encourage national proceedings. That strategy is rooted in the OTP’s assessment that while Colombia has the national capacity to prosecute those most responsible for international crimes, including “false positive” killings, conflicting political interests and an inadequate prosecutorial strategy have at times undermined efforts to carry out these prosecutions.[53] (These are, broadly speaking, the same key obstacles identified by Human Rights Watch’s research, as indicated above.) The interim report accordingly identifies priority areas as an effort to overcome a lack of adequate prosecutorial strategy domestically; one of these is “false positive” cases.[54]

Since the interim report and as of the end of 2017, the OTP has carried out six trips to Colombia: three in 2013 (in April, June, and November), two in 2015 (in June and May), and a high-level mission, led by the prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda, in 2017. During these trips, OTP officials met with officials from the three branches of government, and representatives of national civil society groups, international NGOs, and international organizations.[55] In addition, OTP officials, on occasion, held meetings with Colombian diplomats in The Hague and with other officials visiting the OTP.[56]

One relevant challenge for the OTP in implementing this approach, however, has been the somewhat limited cooperation from Colombian authorities.

During the administration of President Alvaro Uribe (2002-2010), the Colombian government targeted local NGOs, accusing them of politically motivated lies, and took a challenging stance with international human rights bodies.[57]

During the administration of President Juan Manuel Santos (since 2010), the Colombian government adopted the view that it should engage with international bodies, including the OTP.[58] As part of this approach, the government has shared a significant amount of information with the OTP, including statistics, hundreds of rulings, spreadsheets on ongoing prosecutions, and a mapping of “false positive” cases.[59]

Despite this, since 2014, Colombian authorities have at times failed to provide material information about the suspects, scope of the investigations, nature of charges, or the investigative steps taken against current or retired generals implicated in “false positive” killings.[60] An official within the Attorney General’s Office told Human Rights Watch that during a 2015 OTP trip the office instructed officials that while they could explain cases, they could not hand over any documents.[61]

Colombian officials have argued that material information about ongoing investigations is confidential under Colombian law and that strictly speaking, ICC states parties do not have a duty to share any information with the OTP during a preliminary examination.[62] One government official said that the government “may voluntarily” share such information “provided domestic law is respected.”[63]

However, the reluctance to share information appears to stem from a belief among some officials that the OTP would use that information as evidence during an ICC proceeding against members of the Colombian military.[64] In addition, the limited cooperation may be due to the peace negotiations with FARC guerrillas. According to an OTP official, “[t]he relationship [with the government] became harder with the peace process…. Our missions created less enthusiasm [in the government], that was clear.”[65]

The OTP publicly noted the government’s lack of cooperation in its November 2015 report. OTP officials told Human Rights Watch that they decided to do so to remind the Colombian government that the ICC case law requires that progress be supported with evidence with a “sufficient degree of specificity and probative value.”[66]

The OTP noted that there was no immediate change in cooperation in response. By August 2016, however, it had ultimately received the requested information from the authorities.[67]

During her September 2017 mission, Bensouda said in a press conference that the Attorney General’s Office had not provided information she had requested regarding “false positives” investigations.[68]

D. Impact of OTP Engagement

Although beyond the scope of this report, as discussed briefly above, it is clear that Colombia’s status as an ICC member country has profoundly shaped the government’s approach to the current peace negotiations, where it has sought to position its proposals as sufficient to avoid ICC intervention. This, in part, repeats the previous government’s approach to the implementation of the Justice and Peace Law for demobilizing paramilitaries.[69]

When it comes to “false positive” killings, the OTP has had an impact on certain Colombian legislation and prosecutorial policies, but, in the period of research covered by this report—that is, mainly after the publication of the OTP’s 2012 interim report and through September 2016— it has had less success in fostering individual prosecutions of senior army officials. There has been significant progress in cases against lower and mid-level perpetrators—including the at least 11 colonels cited above—since 2012, and our interlocutors thought the OTP was one of several factors advancing these cases. There is little indication, however, that this progress will translate into cases against higher-level defendants; while proceedings have been initiated against 19 generals, the cases have been marked by undue delay. (The OTP’s impact on legislation, prosecution policies, and prosecutions is evaluated below.)

1. Legal Framework for Peace and Constitutional Court Ruling

In 2012, lawmakers passed the Legal Framework for Peace, a constitutional amendment that sought to lay the groundwork for the peace negotiations with FARC guerrillas. The amendment included a range of benefits for those responsible for human rights abuses committed in the context of the armed conflict, including members of the armed forces. While its applicability was overtaken by the justice agreement that the government and FARC reached in December 2015, the amendment would have benefited members of the armed forces responsible for “false positive” killings, since Colombian courts have considered that many of these killings are connected to the armed conflict.[70]

The amendment empowered Congress to limit prosecutorial efforts to those deemed “most responsible” for international crimes committed in a systematic manner, in an attempt to emulate the OTP’s prosecutorial strategy. [71] In fact, the OTP’s prosecutorial strategy is cited in the official explanation of the bill.[72]

According to the vice minister of justice at the time, this provision was not meant to limit the prosecutions to those strictly required by the ICC, but was rather a “policy transfer” premised on the argument that limiting the prosecutions to those “most responsible” would make prosecutions most effective.[73]

While some prioritization is to be expected in situations of mass atrocities committed by thousands of perpetrators, a selective policy limited to those “most responsible”—meaning that all others will not be prosecuted for their crimes—fails to meet the state’s responsibility to hold those responsible for abuses accountable.[74]

In addition, the Legal Framework for Peace amendment allowed authorities to fully suspend prison sentences even for those deemed “most responsible.”[75] This provision seemed designed to facilitate justice negotiations with the FARC and severely undermined the chances of meaningful justice for grave abuses.

In July and August 2013, the OTP sent letters to Colombian authorities clarifying its views on these two issues. The first, sent on July 26, argued that suspended sentences for those most responsible for the worst crimes were incompatible with the Rome Statute.[76] The second, sent on August 7, clarified that the OTP’s prosecutorial policy focuses on those most responsible in its own cases before the ICC , while also supporting national investigations for lower-ranking perpetrators to ensure that offenders are brought to justice by some other means.[77] The letters were leaked in August 2013, published in Semana magazine, and widely reported. [78]

Although the OTP’s letters were controversial and led to some civil society representatives criticizing the OTP, several interviewees, including a Constitutional Court judge, agreed the letters had a significant influence over the August 2013 Constitutional Court ruling. [79] The ruling declared that the Legal Framework for Peace was constitutional, but prohibited the full suspension of penalties for those “most responsible” for crimes against humanity, genocide, and war crimes committed in a systematic manner.[80]

2. Bills Expanding Military Jurisdiction

From 2012 to 2015, the Defense Ministry presented numerous bills that would transfer “false positive” cases from civilian to the military jurisdiction, where—given the military jurisdiction’s lack of independence—it was not expected they would be prosecuted.[81]

Such proposals ran contrary to the view of the UN Human Rights Committee that civilian justice authorities should investigate and prosecute alleged human rights violations.[82] One of these bills was passed in December 2012, but was struck down by the Constitutional Court in October 2013 on procedural grounds. Attempts to pass new legislation opening the door to the transfer of extrajudicial killings to military jurisdiction were frustrated largely due to pressure by domestic and international NGOs, which had also been important voices in opposing such bills from the outset.

The OTP included these bills as part of their focus on Colombia in its 2012 interim report, noting that it “[would] seek further information and clarification … on the legislative efforts pertaining to the jurisdiction of military courts.”[83]

In their 2013 visits, OTP officials discussed the bills with government officials.[84] According to a former Defense Ministry official, during one meeting, OTP officials “threatened” that transferring “false positives” to military jurisdiction could affect the OTP’s assessment of admissibility.[85] Civil society representatives asked the OTP to explicitly condemn the bills.[86]

The threat that the passing of these bills would help foster an ICC investigation played a significant role in the public debate in Colombia.[87] In fact, many statements by civil society groups highlighted that the bills would open the door for an ICC investigation.[88] Human Rights Watch also referred to the ICC in its advocacy against the bills.[89]

Indeed, according to Human Rights Watch interviews, including one with a defense official, members of the Colombian army responsible for “false positive” killings seemed to fear an ICC investigation, giving leverage to government officials in discussions with members of the military about progress in prosecutions or legislative reforms.[90] For example, a former Defense Ministry official said that he often “used the ICC as a backup in negotiations with members of the military” about legislative proposals to prosecute them.[91]

In its 2013 report on preliminary activities, the OTP took note of the concerns by civil society representatives, international NGOs, and human rights bodies. However, it reported that the bills were not inconsistent with the Rome Statute since the “analysis of national proceedings is case specific, and there is no assumed preference for national proceedings to be conducted in civilian as opposed to military jurisdictions per se.” It went on to indicate that it would “evaluate whether specific national proceedings have been or are being carried out genuinely.[92]