Summary

After seven years as reluctant hosts to a million or more Syrian refugees, some Lebanese politicians have become increasingly vocal since 2017 in calling for the refugees to go home, and certain Lebanese municipalities have since 2016 engaged in forcibly evicting them from their homes and expelling them from their localities. At least 3,664 Syrian nationals have been evicted from at least 13 municipalities from the beginning of 2016 through the first quarter of 2018 and almost 42,000 Syrian refugees remained at risk of eviction in 2017, according to the UN refugee agency. The Lebanese army evicted another 7,524 in the vicinity of the Rayak air base in the Bekaa Valley in 2017 and 15,126 more Syrians near the air base have pending eviction orders, according to Lebanon’s Ministry of Social Affairs.

As Lebanon moves toward the first parliamentary elections in nearly a decade in May 2018, calls by some politicians and segments of the public for Syrians to return to Syria have increased, and certain politicians have been quick to blame displaced Syrians for a host of social and economic ills, many of which predate the Syrian refugee influx. The President of Lebanon, among others, has said that Lebanon can no longer cope with the social and financial costs of the refugee crisis. Lebanon’s refugee-hosting fatigue has been exacerbated by a lack of international support. The United Nations’ appeal for US$2.035 billion in international aid to meet the humanitarian assistance needs of Syrian refugees in Lebanon for 2017 was only 54 percent funded, as of December 2017. Lebanon also hosts approximately 175,000 Palestinian refugees.

Mass evictions of Syrian refugees from municipalities are occurring in an environment of discrimination and harassment. Syrian refugees said that hostility and pressure to leave Lebanon is rising. Some said the pressure was coming only from certain politicians, municipal police, and from groups with political or racist agendas and not from their Lebanese landlords, employers, and neighbors. Others said harassment by neighbors and on the street has also increased.

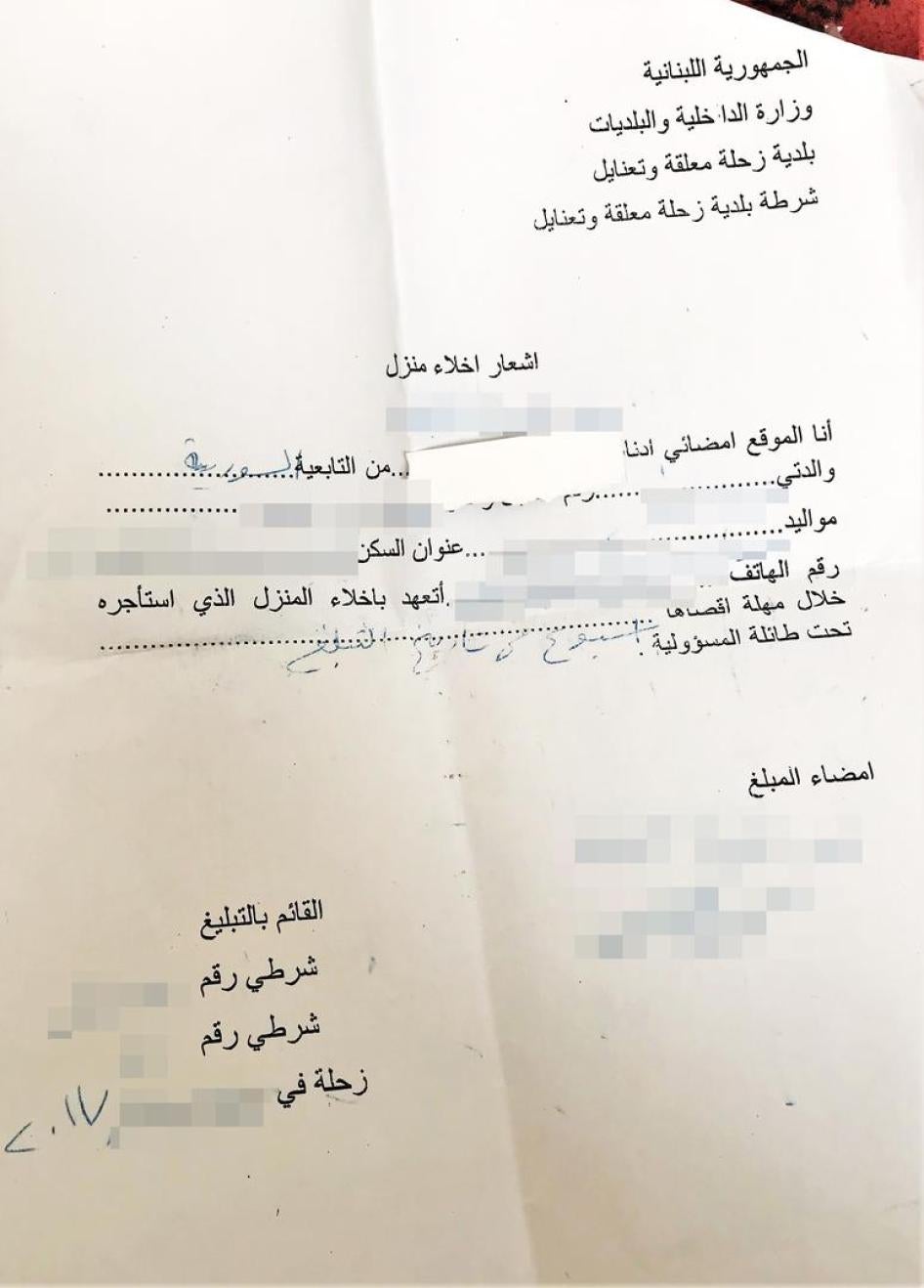

Mahmoud, a 56-year-old man who had been living in Zahle since 2012, said that a group of municipal police led by a policewoman kicked and banged on the door of his family home in August 2017 and demanded to see all their papers, including legal residency papers for Lebanon, rental contract papers, and UN papers. Mahmoud said the municipal policewoman told him that his papers were not correct and that the family would have to leave the house in four days. “She was very rude to us. She gave us a paper to sign that said we had to leave our house, but what she said verbally was to leave Zahle and go back to Syria. I replied to her that I wished I could go back, but that I couldn’t.”

There has been little uniformity in the way municipalities have carried out forced evictions. Officials from some municipalities, like Zahle in the Bekaa Valley, drafted eviction notices and posted them on people’s doors; officials from other municipalities, like Mizyara in north Lebanon, only made verbal demands for Syrians to leave. In contrast to Mizyara and Zahle, where municipal police were highly aggressive and Lebanese residents cheered them on, in Hadath, just outside of Beirut, Syrian refugees consistently told Human Rights Watch that the municipal police who came to evict them were generally polite, even apologetic, saying that they were only carrying out the orders of the mayor.

There was also no consistency in the reasons given for evictions, in the documents municipal police demanded to see, or in the amount of time Syrians were given to leave. While Lebanese municipal authorities make tepid claims that their evictions of Syrian refugees have been based on housing regulation infractions, such as not registering their leases with municipalities, of which there are widespread breaches by Lebanese citizens as well, the measures these municipalities have taken have been directed exclusively at Syrian nationals and not Lebanese citizens.

Evidence obtained by Human Rights Watch makes it clear that Syrians in these communities were targeted because of their nationality: Statements by local authorities, politicians and community leaders surrounding the evictions support this conclusion, as does the inconsistency among municipalities in attributing evictions to labor and residency regulation violations, which are not valid legal bases for evicting tenants from their homes.

Syrians may also be targeted for eviction because of their religious affiliation. To date, the municipalities the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has identified as being involved in forcibly evicting and expelling Syrian refugees have been predominantly Christian, except for Temnine al-Tahta in Baalbeck-Hermel. All the Syrian refugee evictees Human Rights Watch interviewed identified as Muslim, though humanitarian agencies have also documented the eviction of Syrian Christians. Most of those interviewed by Human Rights Watch attributed their eviction, in part, to their religious identity. For example, some evicted refugees told Human Rights Watch that municipal police followed hijab-wearing Syrian women to their homes to identify them and their families for eviction. Others said municipal police told families they might avoid eviction if the women stopped wearing the hijab. Others said that the municipalities allowed Christian refugees to stay. “They didn’t even knock on the door of a Christian family who lives two blocks away from me,” said Ihab, a 30-year-old refugee from Idlib who was evicted from his home in Hadath in early December 2017. “They are Syrians, but they were not expelled.” A municipal official in Bcharre, near Mizyara in north Lebanon, told Human Rights Watch, “This is a Christian town. There is no mosque here.”

Most refugees interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they had no previous problems with neighbors or landlords before the municipalities evicted them. Things changed in Mizyara when in September 2017 a Syrian national was accused of raping and murdering 26-year-old Raya Chidiac, a Lebanese woman, inside her home. In the days following the crime, various groupings of municipal police, Internal Security Forces (ISF), and armed men roamed the streets of Mizyara and began knocking on doors of Syrian refugees and telling them to leave the town.

In some cases, the authorities made cursory and perfunctory checks of residency and rental papers, but refugees interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that their expulsion was not about any housing code infraction or immigration violation. “They cursed us and said, ‘You must leave Mizyara, we don’t want you here,’” said Sameh, a Syrian refugee from Hama who had been living off and on in Lebanon for more than 13 years. “They immediately began beating us. They punched me in my face, my head, my back.” The beating lasted about a quarter of an hour. He said that they came back later that night and beat him again, and that one threatened him by pointing a gun at him and cocking it. Sameh and his family left the next morning.

In the days following the death of Chidiac, the nearby municipality of Bcharre issued a circular saying, “our homes are not for strangers” and went on to forbid Lebanese landlords from renting apartments to Syrian families and demanded that Syrians vacate the homes where they were residing. Municipal authorities have evicted and expelled Syrians in other municipalities and were continuing to evict Syrians in Zahle, Bcharre, and Hadath at the time of Human Rights Watch’s January 2018 investigation.

Those municipalities that expel Syrian refugees may end up hurting their communities economically. A number of the evicted refugees interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that their former apartments now stand empty, depriving their former landlords of an important source of income. After leaving their homes, many are no longer working in their former municipalities where many had worked for years. Some told us that they believed their departure would leave a gap in the labor market since they were cleaning streets, picking apples, and performing other low-paying, manual jobs that others were reluctant to do.

While there are lawful bases for evicting people from their homes, evictions that amount to unjustifiable nationality-based or religious discrimination, as is the case with the municipal evictions documented in this report, are never permissible. Even in cases where there may be legitimate, security-based or other reasons for ordering an eviction, as is possible in the case of evictions in the vicinity of the Rayak air base, proper procedures must be followed to make the evictions comply with accepted international standards. In none of the cases investigated by Human Rights Watch were such standards met. Under Lebanese law, labor or visa violations are not a legal basis for eviction from one’s home.

Even if the municipal evictions documented in this report did not amount to discrimination, they would fail to meet international procedural standards for lawful evictions. In particular, the authorities have provided affected people no opportunity for genuine consultation, adequate and reasonable notice, or any possibility of appeal. Authorities have provided no legal basis to authorize the eviction or expulsion of refugees from entire municipalities. Except for the Rayak air base evictions, authorities have provided evictees with no explanation regarding the alternative purpose for which the land or housing was to be used, and neither those evicted from Rayak air base, nor municipalities have had access to legal remedies to challenge the evictions. In no case did any of the Syrian evictees interviewed by Human Rights Watch say that any Lebanese government authority, civil or military, offer or provide alternative accommodations or compensate them for lost properties. In some cases, Syrians said municipal officials told them to return to Syria, and refugees interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they knew people who went back to Syria after being evicted.

“There was no court, no judge, no legal procedure,” said Hafez, a 57-year-old long-time resident of Hadath, who said that all his papers were in order at the time of his January 2018 eviction. “The [municipal] police did not accuse me of illegal residence because I am a legal resident. They just said, ‘You have to leave or we will put your stuff on the street.’ They came every week, then every day, then twice a day.”

Many of the Syrian refugees who were forcibly evicted said they had to leave property behind and many also had paid the month’s rent in the places from which they were being evicted while simultaneously having to pay rents and security deposits for new apartments. The evictions also disrupted their livelihoods so that many were experiencing loss of income at a critical time when they needed money to transport property, send children to school, or commute back to work places in the towns from which they had been evicted. Forced evictions have also disrupted education, sometimes causing children to miss months of schooling, and in other cases, causing them to stop going to school entirely.

The impact of forced eviction, particularly for those like Riad, 25, who had amicably lived many years among his neighbors, was also psychological. Since his eviction, Riad has been out of work and unable to provide for his children. Going back to Syria, he said, was not an option. “If I went back to Syria, I would be caught by the army.” Riad now lives in a neighboring town in a house with a leaky roof and no heat. “We couldn’t afford to transport our things from Hadath,” he said, “but the sentimental losses for me are more than the material ones. I had to leave my birds behind that I had for five years. When I went back for them later, they were all dead.”

This report calls on municipal authorities in Lebanon not to evict or expel Syrian nationals based on their nationality or religion or because they are refugees. Individuals and individual families should only be subjected to evictions for transparently stated, lawful and proportionate reasons with proper notice, a minimum necessary use of force, with opportunities for legal challenges, and the provision of alternative accommodations and compensation.

Relevant ministries of the Lebanese government, including the Ministry of Interior and Municipalities, should intervene to prevent municipal-level mistreatment of Syrian refugees and to ensure that they are not left homeless and destitute as a result of unlawful actions. Recognizing that Lebanon hosts the highest per capita number of refugees of any country in the world, the international community should increase support to Lebanon to enable it to meet its legal and humanitarian obligations towards the refugees. For their part, Lebanese leaders should curb rhetoric that encourages or condones forced evictions, expulsions, and other discriminatory and harassing treatment of Lebanon’s Syrian refugee neighbors.

Recommendations

To Lebanese Municipal Authorities

- Cease evicting and expelling Syrian nationals based on their nationality or religion or because they are refugees.

- Cease evicting or expelling Syrian nationals from a municipality because of their immigration status or violations of labor regulations.

- When evictions are for a legitimate purpose, they should be carried out according to principles of reasonableness and proportionality that include informing those affected of the legal reason for the eviction, seeking alternatives to eviction, considering and minimizing the impact of eviction on those affected, and when eviction is unavoidable, ensuring that it does not render the affected persons homeless.

- Give any person identified for eviction and their landlord an opportunity for genuine consultation with municipal authorities.

- Give adequate and reasonable notice of an impending eviction to all affected persons.

- Ensure that legal remedies are available to affected persons who would like to challenge their evictions and inform them of their right to challenge the eviction in a court of law.

- Ensure that municipal police and any other officials who order tenants to leave their homes, or who are present during an eviction are clearly identified.

- Ensure that evictions do not take place at night or under bad weather conditions.

- Assist people being evicted with alternative accommodations and compensation for losses.

To Lebanon’s Ministry of Interior and Municipalities

- Publicly declare that it is illegal for municipalities to evict or expel displaced Syrians on the basis of their legal residency under Lebanese immigration law, their refugee status, employment violations, or based on their nationality or religion.

- Provide legal assistance to enable landlords and tenants to prevent unlawful evictions and expulsions of displaced Syrians from municipalities and help forced evictees to seek redress for their wrongful eviction or expulsion.

- Direct Internal Security Forces officers not to facilitate illegal forced evictions or expulsions.

- Investigate reports that Internal Security Forces used unreasonable or unlawful physical violence during forced evictions and hold accountable any officers found to have done so.

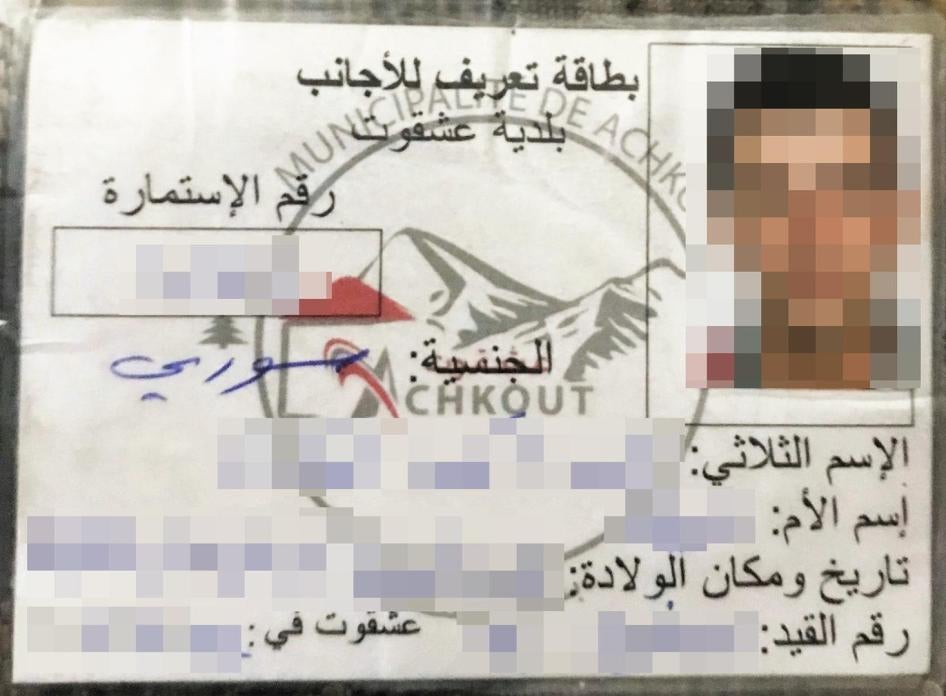

- Direct municipalities to stop arbitrarily issuing their own identification cards to Syrian nationals.

- Establish a national eviction monitoring program jointly with the Ministry of Social Affairs to identify households at risk of eviction, prevent illegal evictions, develop alternatives to eviction, and, when unavoidable, ensure that evictees find appropriate accommodation.

To Lebanon’s Ministry of Defense

- Direct Lebanese army personnel, including Military Intelligence, not to enforce or facilitate forced evictions or expulsions of Syrian nationals from municipalities.

- In case of future evictions necessitated by security requirements, ensure that affected persons are provided due process according to international standards, including being consulted and informed in writing of the reasons and timing of the eviction; are given the opportunity to legally challenge the eviction; and are provided alternative accommodations, assistance, and compensation for losses.

To Lebanon’s Ministry of Social Affairs

- Establish a national eviction monitoring program jointly with the Ministry of Interior and Municipalities to identify households at risk of eviction, to prevent illegal evictions, to develop alternatives to eviction, and, when unavoidable, to ensure that evictees find appropriate accommodation.

To Lebanon’s Ministry of Education

- Investigate the Bcharre municipality’s refusal to enroll Syrian children in its public schools at the beginning of the 2017-18 school year and hold accountable any officials who wrongfully barred Syrian children from school.

- Ensure that Syrian children who have been forcibly evicted or expelled from municipalities are provided with access to education in their new locations.

To Donor and Resettlement Countries

- Fully fund UN humanitarian appeals to help meet the needs of all Syrian refugees in Lebanon regardless of their legal residency status in the country.

- Help to relieve pressure on municipalities by increasing the number of available resettlement places for vulnerable refugees from Syria in Lebanon.

- Convey to municipalities and schools that accept international humanitarian funding arising from the Syrian refugee situation to improve their social infrastructure that it is unacceptable to expel, evict, or reject displaced Syrians after having accepted such funding.

To the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)

- Support strategic litigation in Lebanese courts to challenge the legality of forced evictions and expulsions by municipalities.

- Conduct public information campaigns to counter the growing political rhetoric that it is safe for Syrian refugees to go home. Publicize UNHCR’s findings that human rights conditions in Syria are not yet conducive to refugee returns. Assure the Lebanese public that most Syrian refugees in Lebanon will willingly return when it is safe for them to do so, and that UNHCR will facilitate returns in safety and dignity when the time is right for voluntary repatriation.

- Identify Syrian refugees who have been evicted from municipalities and provide prompt emergency humanitarian assistance, in particular to prevent homelessness and deepening destitution.

- Redouble efforts to impress upon donor and resettlement governments the protection imperative of providing adequate humanitarian assistance and resettlement places for Syrian refugees in Lebanon.

To International and Lebanese Nongovernmental Organizations

- Seek to undertake strategic litigation to challenge the legality of municipal evictions and expulsions.

- Counter the rhetoric that Syrians drain the Lebanese economy and represent a security and demographic threat. Cite evidence that Syrians, in fact, contribute in many ways to the Lebanese economy, including by working in jobs that few Lebanese citizens are willing to perform, by paying rent, and by spending on consumer goods. Argue that Syrian refugees collectively should not be punished for crimes committed by individuals.

Methodology

In January 2018, Human Rights Watch interviewed 57 Syrian refugees in Lebanon who have been directly or indirectly affected by Lebanese municipalities forcibly evicting Syrian refugees. Human Rights Watch conducted interviews in private settings—either completely alone or with close family members present—with assurances of confidentiality. Human Rights Watch told interview subjects that they would receive no payment, service, or other personal benefit for the interviews. All were told that they could decline to answer questions or could end the interview at any time. The interviews were conducted in English by two male researchers and a female Arabic interpreter. Additional interviews and conversations were held with Lebanese landlords and employers. We also interviewed municipal officials in Bcharre and Zahle. To protect confidentiality, pseudonyms are used for all Syrian interview subjects. Human Rights Watch also met with nine nongovernmental and UN humanitarian agencies in Lebanon. On February 21, 2018, Human Rights Watch wrote to the Lebanese Ministries of Interior and Municipalities, Social Affairs, Education and Higher Education, and the Displaced with questions relating to the findings in this report. On April 12, the Ministry of Social Affairs responded via letter. As of April 13, none of the other ministries had responded.

Terminology

The term forced evictions as used in the report, and in international law, denotes the removal of individuals and families from the homes or lands they occupy against their will without the provision of, and access to, appropriate forms of legal or other protection. None of the evictions documented in this report amount to lawful evictions as defined by the international treaties on human rights that Lebanon has ratified. We use the term expulsion to refer more broadly to coercive measures to compel people to leave a municipality or other local area against their will.

This report refers to Syrians living in Lebanon as refugees. Human Rights Watch recognizes that many Syrians came to Lebanon as migrant workers, that many have Lebanese sponsors and continue to register their residency status, in part, because Lebanon does not recognize Syrians as refugees. We call Syrians refugees because regardless of the reasons they may originally have come to Lebanon, a person is a refugee as soon as he or she has a well-founded fear of being persecuted if returned, regardless of whether they are formally given refugee status. In its latest update assessment, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) continues to characterize the flight of civilians from Syria as “a refugee movement, with the vast majority of Syrian asylum-seekers continuing to be in need of international refugee protection, fulfilling the requirements of the refugee definition contained in Article 1A(2) of the 1951 Convention.”[1]

I. Background

After seven years as reluctant hosts to a million or more Syrian refugees, some Lebanese politicians in 2017 became increasingly vocal in calling for the refugees to go home, and, although evictions of Syrian refugees from municipalities have been recorded from as early as July 2014 and continued in 2016, the number of municipalities forcibly evicting Syrian refugees from their homes and expelling them from their localities increased in 2017 and the first quarter of 2018.[2]

An estimated quarter of Lebanon’s total population is now comprised of refugees, the highest per capita population of refugees of any country in the world.[3] Lebanon has not recognized Syrians in Lebanon as refugees, and has not allowed UNHCR to open formal refugee camps in the country.[4] Meanwhile, it has imposed harsh residency regulations that make it difficult for Syrians to maintain legal status in the country and restricted their ability to work.[5] According to UNHCR, 74 percent of Syrians in Lebanon do not have legal status, and 76 percent live below the poverty line, making it difficult to work or access education and healthcare, contributing to child labor and early marriage, and leaving them more vulnerable to exploitation and abuse.[6]

Human Rights Watch has long documented abuses against Syrians in Lebanon, including reports of torture, deaths in military custody, physical attacks, returns to Syria, and the widespread use of discriminatory curfews.[7] More than 250,000 Syrian refugee children are out of school, largely due to parents’ inability to pay for transport, child labor, school directors imposing arbitrary enrollment requirements, and lack of language support.[8]

There are currently just under one million Syrian refugees registered with UNHCR, but Lebanon’s government instructed the agency to cease registration of refugees in May 2015.[9] The Lebanese authorities estimate that there is a total of around 1.5 million Syrians in a country that is beset with chronic unemployment, lack of affordable housing, and under-resourced public schools. In addition, the Lebanese economy has been suffering from declining levels of tourism, shortfalls in foreign investment, persistent pollution, and a weak public infrastructure.[10]

Lebanese politicians and the public have blamed refugees for these and other problems, against a political and religious backdrop of concerns that the refugee presence will upset the delicate demographic balances that have prevailed in Lebanon since the end of the civil war in 1990.[11] While refugees pose real challenges to Lebanese society, politicians have also used them as a scapegoat to deflect from an underperforming economy and a host of social problems that predate the arrival of Syrian refugees.[12]

Anti-refugee rhetoric, including calls for refugees to go home, amplified in 2017. “Any foreigner who is in our country, without us agreeing to it, is an occupier, no matter where they come from,” said Foreign Minister Gebran Bassil in October. “Syrian citizens—our brothers and sisters—only have one choice: to return to their country.”[13] Later that month, Lebanese President Michel Aoun, said that the country “can no longer cope” with the presence of Syrian refugees and he appealed to the international community for help to organize their return.[14] Less than two weeks after President Aoun called for the return of Syrian refugees, Hezbollah’s Secretary General, Hassan Nasrallah, said that the issue of Syrian refugees had become a pressing issue in Lebanon and that a “big part of Syria has become safe and quiet.”[15] Nasrallah recommended that Lebanon coordinate with the Assad government for the return of refugees.

Echoing these statements at the municipal level, there is also a rising chorus for Syrian refugees to leave. Antoine Abou Youness, vice president of the Zahle Municipal Council, declared to Human Rights Watch that Syrians in Lebanon are not refugees, but rather migrants, and it is safe for them to go back to Syria. “The situation [in Syria] is completely changed. We don’t want what happened with the Palestinians to happen with the Syrians.”[16]

Lebanon’s refugee-hosting fatigue has been exacerbated by a lack of international support. The US$2.035 billion humanitarian assistance needs of Syrian refugees in Lebanon for 2017 were only 54 percent funded, as of December 2017.[17] A joint report from UN humanitarian agencies warned that “insufficient funding is threatening food assistance, health care and access to safe water, as well as constraining the ability to support vulnerable localities in the prevention and management of tensions between host communities and refugees.”[18]

Those municipalities that expel Syrian refugees may end up hurting themselves economically. A number of the evicted refugees interviewed by Human Rights Watch said their former apartments now stand empty, depriving their former landlords of an important source of income. After leaving their homes, many are no longer working in their former municipalities where many had worked for years. Some told us that they believed their departure would leave a gap in the labor market since they were cleaning streets, picking apples, and performing other low-paying, manual jobs that others were reluctant to do.

As one Lebanese business owner and landlord told Human Rights Watch, “Since the Syrians have left, the Lebanese are not making money.”[19] What shopkeepers and landlords are discovering firsthand, economists are also noticing. One indicator of refugees as stimulants to the Lebanese economy is the influx of international humanitarian and development funding that comes with the refugee presence. For example, since 2013, refugees have spent $900 million at Lebanese shops using credit cards distributed by the World Food Program.[20]

II. Mass Forcible Evictions Targeting Syrian Refugees

According to the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), municipal evictions of Syrian refugees occurred in several towns in northern Bekaa in 2016,[21] but in 2017, the UN refugee agency recorded mass evictions of Syrian refugees from six municipalities in northern Lebanon, four in Bekaa, and three in Mount Lebanon, in addition to mass evictions in the vicinity of the Rayak air base in Bekaa.[22] At least 3,664 Syrian nationals have been evicted from at least 13 municipalities from the beginning of 2016 through the first quarter of 2018, with the qualification that this is their best estimate based on cases reported to them. This includes 849 evicted from Zahle, 822 from Mizyara, 750 from Tamnine al-Tahta, 488 from Bcharre, 262 from Deir el Ahmar, 150 from Rahbeh, 120 from Qaa, and 67 from Hadath.[23] In addition to the 3,664 mass municipal evictions, UNHCR recorded about 10,000 other Syrian evictions for various reasons, including failure to pay rent and other disputes with landlords, choices by landlords to use land for alternative purposes, and for reasons of “safety and security.”[24] UNHCR estimated that another 42,000 Syrian were at risk of eviction in 2017.[25] Lebanon’s Ministry of Social Affairs reported to Human Rights Watch that 7,524 Syrians were evicted from the vicinity of the Rayak air base in 2017 and that another 15,126 still have pending eviction orders.[26]

The mass, forced evictions and expulsions of Syrian refugees that occurred with increasing frequency in the last quarter of 2017 are not the result of a coherent national plan, but rather an ad hoc response that appears to be in municipalities that—except for Tamnine al-Tahta—are predominantly Christian. This chapter looks at evictions in four municipalities: Mizyara, Bcharre, Hadath, and Zahle, and from the vicinity of the Rayak air base.

Forced Eviction as Collective Punishment of Syrian Refugees in Mizyara

Scapegoating often begins with a crime, and in this regard, what happened in Lebanon in 2017 is no exception. On September 22, 2017, 26-year-old Raya Chidiac, a Lebanese woman, was allegedly raped and killed inside her home in Mizyara, a village located in northern Lebanon.[27] After a Syrian national was accused of the crime, a huge wave of anger swept the northern town, with residents of Mizyara calling on Lebanese authorities to expel all displaced Syrians living in Lebanon.[28]

From the accounts of Syrian refugees living in Mizyara at the time, many of whom said they had lived amicably with their Lebanese neighbors there for many years, the outpouring of hatred came as a shock. Iyad, a 23-year-old Syrian man who said he had been living without any problems in Mizyara since 2012, said that on the fourth day after the incident, after a Syrian was accused of the crime, he received a call from someone working in the Mizyara municipality. The caller warned him that there were people going house to house and beating up Syrians:

That night cars were driving around and people were cursing Syrians on a megaphone. They had shotguns, sticks, and were hanging out the windows. Nine of them came right outside my house. They came just to our house since there aren’t other Syrians living on our block. They weren’t local people from Mizyara. They stayed until about 4 a.m. and we stayed inside. We were too afraid to sleep, thinking they would burst inside.[29]

The situation was worse for his brothers, also Mizyara residents:

I had two brothers, one just 13, and cousins; they were all beaten. I went up to see my brothers and saw that someone came and beat them, destroyed their house, and told them to leave by 6 a.m. They told me the municipal police came in three cars.[30]

Another Syrian refugee, Brahim, 38, said municipal police and “a detective” came to his door at 7 a.m. three days after the incident, and told him, “You need to be gone.” The following night at 1 a.m. a group of seven or eight men whom he did not recognize banged on his door. They were brandishing sticks and told him he had to be out by 7 a.m. that morning “or you’re going to see something you won’t like.” Brahim said, “Within 24 hours there were no Syrians left in Mizyara.”[31]

While Brahim and Iyad spoke of collusion between municipal police and “thugs,” they attributed direct violence to strangers in civilian clothing. However, Marwan, 48, and Sameh, 37, both refugees who had lived and worked for many years in Mizyara, said it was municipal police, wearing green uniforms, and Internal Security Forces (ISF), wearing grey and blue camouflaged uniforms, who beat them. Marwan said that at 7 p.m. four days after the crime, his landlord, who was also a municipal employee, came to his home where he, his wife, two children, and two other family members were living, and told him they had to leave by 7 a.m. the next morning. One hour later, he said, municipal police, ISF, and “thugs” not from Mizyara, came into the area. He said the municipal police were armed with pistols and shotguns and that the ISF had Kalashnikovs:

Four of the ISF broke down my door. They asked for my papers. I told them if they wanted me to leave, I would leave tonight, but they started beating me. They hit me with the pistol butt and their hands, they kicked me, hit me with a kitchen pot. Three of them were hitting me on my legs and back for about 15 minutes. I couldn’t stand for a week.[32]

Marwan said the municipal police, ISF, and “thugs” came back twice during the night, the first time cursing them, calling them “dogs” and saying they had to be gone by morning, and hitting his sons, including one child. The second time they beat them more harshly, including kicking Marwan in the face. “The police [ISF] took one of my relatives on the balcony and threatened to throw him off from the second story. They kicked us again, and one of them shouted down from the balcony, ‘I think I broke his leg.’”[33]

Marwan said he left at 5 a.m. “I didn’t take any of my things. I left as I was.” He said he later sent someone to get his belongings, but that his landlord refused to release his possessions.

Sameh, in a separate, private interview, gave a similar account of what happened to him in the apartment that night. He said no one presented a paper or an order for his eviction, but a municipal official came to the door saying they had to be gone by the following morning. He then said that variously armed municipal police, ISF, and “thugs” came to his building. He said the ISF came to the door, checked his papers, and accused him of being in Lebanon with expired legal residency. “They [ISF] immediately began beating us. They punched me in the face, head, my back. They kicked me. It lasted about a quarter of an hour.” Sameh said they cursed him and his family and said, “You must leave Mizyara, we don’t want you here.” He said that they [ISF] came back later and beat him again, this time hitting him on the nose, and that one threatened him by pointing a gun at him and cocking it. “It makes you hope for death,” he said about the experience of being beaten. Sameh and his family left that morning in a rented car at a cost of US$200.[34]

Xenophobia-driven Forced Evictions in Bcharre

According to refugee accounts and our interview with a municipal official, the forced evictions of Syrian refugees from Bcharre are broadly regarded as a reaction to the rape and murder of Raya Chidiac in the nearby town of Mizyara. Tony Succor, the head of the Administrative Department of the municipality of Bcharre, told Human Rights Watch why municipal leaders decided to expel Syrians:

Following the Mizyara incident, the people here took to the streets to tell the Syrians to leave. We took this action to prevent a problem before it happens. We put in place a 7 p.m. curfew to protect each group from the other. There have been no fights or incidents yet, but if something like Mizyara happened here, there would be a war. This was a preventive decision. We tell people by letter that they have 15 days to leave, and then we give them another 15 days…. This is a popular decision. We are following the popular will.[35]

In the days following the Chidiac rape and murder, a circular “issued by the Municipality of Bcharre, its priests and mukhtars” declared “our homes are not for strangers” and went on to say, “No one may impose on us settlements or emergency housing for newcomers at the expense of our people.” The circular blamed “organized crime,” including “the most recent…horrifying Mizyara crime” on the presence of displaced Syrians and said that “our society and demographics have experienced collapse from this organized and planned displacement.” Finally, it called on the people of Bcharre “to raise up our community, fallen under the sway of easy money, as our homes are no longer our own” and unite on the following points:

- Syrians shall not gather in public squares.

- They may not go out at night after 6 p.m.

- No renting to Syrian families as of November 15, 2017, and demand that they vacate the homes they reside in, as they are not needed to do work in our town, especially after the improvement of the situation within Syria. Let the international community go and find solutions that we cannot accept at the expense of our people. All legal measures will be taken against those violators who have not registered their leases with the municipality.

- Competent security forces and municipal police will perform regular inspections of Syrians’ homes.[36]

Sham, a 34-year-old woman from Idlib, said that municipal police came to her door on November 11, 2017 and told her that she had 20 days to leave Bcharre. She said that they came back three times:

They showed me a paper that said that the municipality is standing in solidarity with the church because of Mizyara and that all Syrians must leave. The [municipal] police told me, “This is our land and we won’t allow anyone else to be killed like Raya.” During this time, I visited my Lebanese neighbors. For the first time, they said, “Syrians should go. Since Raya’s death, we don’t trust letting the Syrians into our houses.”[37]

The third and final time the municipal police came to her door, Sham said, they told her, “If we come again, the next time, we will do other things.” She said, “I understood this to mean they would beat me.”[38]

Although municipal official Tony Succor reiterated that there had been no criminal or security incidents in Bcharre, he said that the Syrians, who he denied were, in fact, refugees, represented a potential security threat:

Security organizations in Lebanon don’t have full information on the refugees. These are people we know nothing about. The local people are afraid of the mentality of the refugees. They think because this is not their town, not their land, they can throw garbage, commit crimes.[39]

According to Succor, 1,700 to 2,500 Syrians lived in Bcharre before November 15, but that by January 2018 their numbers had been reduced to 700 to 800.

Heavy-handed Forced Evictions in Zahle

In Zahle, refugees said that in August and September 2017, the municipal police went methodically block by block to demand that refugees leave and coerced them to sign eviction notices that were then posted on their doors. Refugees interviewed by Human Rights Watch consistently described the municipal police as rude and aggressive, particularly the female municipal police officers who supervised the visits. This contrasted with refugee accounts of the Hadath evictions, where most refugees told Human Rights Watch that the municipal police were polite, in some cases even apologetic, about informing them that they had to leave.

Mahmoud, a 56-year-old man who had been living in Zahle since 2012, said a group of municipal police led by a policewoman kicked and banged on the door of his family home in August 2017 and demanded to see all their papers, including legal residency papers for Lebanon, rental contract papers, and UN papers. Mahmoud said the municipal policewoman told him his papers were not correct:

She said we had to leave the house in four days. She was very rude to us. She gave us a paper to sign that said we had to leave our house, but what she said verbally was to leave Zahle and go back to Syria. I replied to her that I wished I could go back, but that I couldn’t. They posted the paper on our door.[40]

Rasha, 28, is the mother of a five-year-old girl who she says is war-traumatized. Rasha was eight months pregnant when nine municipal police burst into her house demanding her eviction one afternoon day in mid-September 2017 when her husband was not home, and no other Syrian men were in the building:

My daughter came screaming. My mother-in-law and I were sleeping without our hijabs. I told them to wait so we could put on our hijabs. They didn’t wait. They burst into the house. They demanded to see my UN papers. Some were holding electric sticks. My child was scared and is very sensitive to loud noises and started having a panic attack. The [municipal] police showed no sympathy but harassed us even more. They got more aggressive, yelling at me to get the UN paper. They questioned me about my husband and made me sign a paper saying I would leave in one week and they put the paper on the door.[41]

Rasha said that her landlady intervened with the municipal authorities telling them that Rasha could not move because of her pregnancy, so the family was given a three-month extension on the eviction order. The three-month extension expired two weeks before Human Rights Watch visited Rasha. She said the municipal police came to her house two weeks prior, telling her she had to leave Zahle.[42]

In a separate, private interview, Rasha’s 57-year-old mother-in-law, Hind, corroborated Rasha’s account of the encounter with the municipal police, but added her own perspective about the rude treatment, particularly by the female supervising police officer. Hind said the policewoman wouldn’t allow her to put on her hijab during the questioning, even though four male policemen were also present. “The first thing she said to my daughter-in-law was, ‘Oh, you are pregnant. That’s what you Syrians are good at.’ During this time my granddaughter was crouched in the corner crying. The police showed no consideration.”[43]

Two refugee men said they were handcuffed and threatened by municipal police for refusing to sign the eviction notices in Zahle. Mohammed, the husband of Rasha and son of Hind, said the municipal police came directly from his mother’s house to his place of work and demanded that he sign a paper saying he would agree to leave the municipality. He refused to sign it. The police handcuffed him and took him to the municipality. Although he said some of his Lebanese friends got into a heated exchange with the police, he stood to the side and did not resist them.

When he got to the municipality, Mohammed said the police made him stand with his face against a wall for more than two hours and then took him to the office of a municipal official, where two other municipal police officers pushed him back and forth between them, offering to beat him up:

I asked [the official] what I did wrong. He said that I refused to sign the paper that says I need to leave the municipality. He said, “Now we are playing with you, but if we see you here a week from now, it will be completely different.” I signed the paper that same day saying I would leave in one week.[44]

Human Rights Watch met with the vice president of the Zahle municipal council, Antoine Abou Youness, who said that Zahle is simply “applying the law regarding apartments.” He said the same regulations would apply to Lebanese citizen tenants, but “80 percent of the security problems come from Syrians, as well as problems with pollution, water, garbage.” When asked if Syrians are being targeted and if they are being expelled from Zahle or just from their apartments, he answered, “We are only asking them to leave their apartments because of some legal problems, but a small percentage we are asking to leave Zahle because of noise and other problems like that.”[45]

In fact, Human Rights Watch met Syrian refugees who had been evicted from their residences in Zahle, who tried to relocate within the municipality, but were then told they had to leave the area entirely. Marzouq, 24, who described Zahle as “my town,” where he had lived for six years, explained how eviction in Zahle really meant expulsion:

In April 2017, the municipal police told us to leave Zahle, but we didn’t want to lose our jobs or our children’s schools, so we tried our luck and moved to another house in Zahle, in the hope they wouldn’t find us. One week after moving, we heard a knock on the door. It was two municipal police officers. They were very rude to us. One said in a very harsh way, “Why didn’t you leave Zahle?” He gave me a paper to sign saying I would leave in seven days but I refused to sign. The police put me in handcuffs and took me to the municipality. At the end, I signed the paper that I would leave in seven days and they put that paper on our door.[46]

“Orders from the Mayor” in Hadath

Syrian refugees who were evicted from their homes consistently said they had no previous problems with neighbors or landlords there, and that the municipal police who came to evict them were generally polite at first, even apologetic, saying they were only carrying out the orders of the mayor, but they became increasingly threatening if residents were slow to leave. Fatima, a 24-year-old woman from Idlib, told us that shortly before New Year’s Eve 2017, three male uniformed municipal police came to her door at 10 a.m. when her husband was not at home:

The first thing they asked was “Why are you still here?” They had never notified us directly to leave but only through the doorman. They said I had until Saturday to leave, which was three or four days from when they came to my door.[47]

Fatima said the municipal police were polite and spoke to her in a normal voice. She said they never asked about her legal residency, did not inquire about her husband, did not produce any written eviction notice or demand that she sign any paper. “I asked them why we had to leave, and they only said the order was coming from the mayor. We moved on January 5.”[48]

Mustafa, 23, from Deir al-Zour, said the problems for Syrian refugees began in Hadath in 2015 when the municipality began pressuring single men to leave, which prompted him to get married. But a year ago, he said, the municipality began pressuring Syrian families to leave as well. Mustafa said that municipal police came to his house in late September and told him he had to leave Hadath in one week. He said it was completely verbal, and they did not provide anything in writing. He told them that he needed more time. One week later, in early October 2017, they returned early in the morning:

Two [municipal] policemen came in uniform. My wife and one-year-old daughter were scared. They said we had four hours to leave the house, and they threatened to hit me. I told them it was not possible to leave so soon. So, they made me sign a paper that said I would leave in one week, and they put the paper on our door. They said if I was not out in one week, I would have to pay US$6,000. I left before the week was out. On the day I left, six or seven municipal police watched us leaving. They didn’t assist or help in any way. They just took photos of us leaving.[49]

Fayez, 35, also from Deir al-Zour, had been working off and on in Lebanon since 2004, but brought his family in 2011 after the war started in Syria. He said he never had any problems with the authorities or his Lebanese neighbors, had entered the country legally, had a Lebanese sponsor, and his family was registered with UNHCR. He said the municipal police began asking for copies of his legal residency papers and started coming to his house every two months to tell him he had to leave Hadath. He said at no time were there any papers to sign, no court order, only verbal orders. But when the municipal police came to his home in early October, they became more threatening:

They told me I had three days to leave. Some of my Lebanese neighbors were there, pleading with them to let us stay, so they then said we had to leave in ten days. They threatened that if we were not out in ten days, the Army would come for us, so we left on October 12 or 13, before the Army would come to evict us.[50]

Human Rights Watch spoke with a Christian landlord and employer of Syrian refugees in Hadath who resisted the eviction of a refugee and experienced retaliatory measures at the hands of municipal authorities but did not want to publicize the account for fear of further retaliation.

The Christmas Evictions from Rayak Air Base

The eviction of 7,524 Syrian refugees from the area around the Rayak air base was not a municipal eviction, but rather was carried out by the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) on security grounds, so in that respect falls outside the scope of this report.[51] However, the lack of due process, the lack of consultation with those being evicted, and the lack of compensation or assistance from the Lebanese government for those being evicted by the government make these evictions, like those from municipalities, fall afoul of the standards for lawful evictions. According to the Ministry of Social Affairs another 15,126 from the vicinity of the air based “are susceptible to eviction at any moment.”[52]

Thousands of Syrian refugees have been living in hundreds of informal tented settlements near the Rayak air base. LAF soldiers in late March 2017 began verbally notifying refugees living in settlements that they had to leave, but refugees reported that the LAF did not provide them written notice and gave inconsistent deadlines.[53] The Ministry of Social Affairs informed Human Rights Watch that “about 12,665 of these [i.e., of the 22,650 ordered evicted] are estimated to have received warnings from Military Intelligence.”[54]

According to nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) that assisted refugees living in Rayak, the evictions took place in several phases. In late March, the LAF informed refugees that they had to move from where they had been living and UNHCR estimated that the order could affect up to 10,000 people.[55] Local organizations said that in June or July, the LAF returned to tell refugees, including many who had moved after the March announcement, that they had nine days to move farther away. After some negotiations, another group of refugees was evicted in September 2017, according to a local NGO official who was assisting the evicted refugees.[56]

Refugees and NGOs came under increasing pressure from Military Intelligence to move, but the authorities had not provided another location for the evictees, nor any assistance to facilitate the eviction.[57] “Military Intelligence was harassing us every day,” said the NGO official. The LAF began carrying out another round of evictions in late December, and winter conditions combined with lack of preparation for alternative shelters resulted in unnecessary misery. The NGO official recalled the hardships:

It was difficult to find another place to move the refugees to; we couldn’t find another camp until we got a license for the land to build it on. Until then, we found a farm 300 meters from the air base. The people stayed there for 17 days while we got the camp ready. They were living in a barn without heat. A lot of people got sick. The Army gave no help in moving people or their belongings, in providing food and water, or heating fuel, or in building a new camp, or in paying the rent to the landowners of the farm or the new camp.[58]

The refugees were not the only ones to incur losses; the private owner of the land to whom refugees had been paying rent lost his tenants, and the NGO, which had just built a school in the informal tented settlement that had to be abandoned, struggled to find new resources to help accommodate the evictees. Neither the Lebanese military nor the Lebanese government compensated any of the affected individuals or groups for their losses.

The Syrian refugee camp manager in Bar Elias, which had been built for about 350 evictees from Rayak just 13 days before the Human Rights Watch visit in January 2018, said the authorities had provided no help for the refugees to get situated in their new location. On the day of our visit he was preoccupied with receiving the first deliveries of heating oil to the camp, in which people (including the Human Rights Watch researcher) were shivering from the cold:

We have gotten nothing from the Lebanese government, not from any municipality or ministry, nothing from the Army. We have requested electricity, but there is no electricity now. We are still trying to build bathrooms.[59]

In an April 12, 2018 letter to Human Rights Watch, the Ministry of Social Affairs said it is “the body authorized to manage cases of eviction,” but that “it does not provide cash assistance; its role is to secure approval for alternative spaces and to secure plots of land on which to set up alternative camps.” With respect to the Rayak evictions, the Ministry said that “a camp was established in the town of Bar Elias after it was approved by the Ministry of Social Affairs, and 74 families were relocated from the surroundings of Rayak.” This appears to be the same camp that Human Rights Watch visited on January 30, 2018. The letter cited no other “alternative spaces” for which it had secured approval.[60]

The Ministry of Social Affairs said that it has developed a plan in cooperation with UNHCR with the following elements:

- Determining the area where the evictions are taking place (the municipal zone concerned).

- The reason for the evictions (municipality - security services - land owner). Each situation is dealt with depending on the reason for the eviction. If it is for security reasons, the Ministry of Social Affairs cannot interfere on the ground, and its role is thus confined to coordinating with the security services to effectuate a plan to relocate the displaced people. In case of other reasons for the eviction, they are dealt with differently as there is a decision on behalf of both the Ministry and His Excellency the Governor of Bekaa not to move any tent or establish any new refugee camp.

- Finding alternative plots of land on the part of the Ministry with technical help from the UNHCR team and securing all the necessary approvals to establish a new refugee camp: from the Governor, the Ministry of Interior, the concerned municipality, and security services.

- Preparing and equipping the refugee camp on the part of the Ministry and relocating the families.

- Preparing two backup plots of land, whereby the available land must have an area of 40,000 square meters in the case of the eviction of large numbers of people.

- Studying the social stability of the municipality that has expressed a willingness to receive the displaced people.

The plan, as outlined above, for establishing “alternative plots of land” for new refugee camps appears to apply to “the eviction of large numbers of people” from informal tented settlements, but not for refugees living in apartments and other housing in municipalities. In its response to Human Rights Watch, the Ministry of Social Affairs does not outline steps for relocating refugees living in such accommodations.[61]

Even in the case of the Rayak eviction, where Human Rights Watch met with refugees who had been relocated to the new location, the refugees contend that there was no procedure, no written notice, no opportunity to discuss or challenge their removal, and it took place in extremely harsh conditions. Razaan, a 42-year-old father of five living in the new camp, spoke to Human Rights Watch in an unheated tent in January with his children gathered around:

About one month ago, Military Intelligence came to our camp and told our camp manager that we had one week to leave. They said, “After one week, we don’t want to see any tents here.” The day we moved, it was raining and cold. Some of our group got very sick. A doctor from one of the NGOs used to visit us in the old camp to take care of sick kids, but since the eviction, no doctor has come. The farm where we stayed [after we were evicted] had no bathrooms and we burned wood to try to stay warm, but it was very cold, very hard those 20 days.[62]

III. Forced Evictions and Expulsions as Possible Nationality and Religious-based Discrimination

Lebanon is a party to the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination (ICERD).[63] The ICERD asserts that distinctions and restrictions between citizens and noncitizens by states is only permissible when such provisions “do not discriminate against any particular nationality.”[64] As interpreted by the IECRD’s treaty body, the United Nations Committee for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD), this means that any distinction based on citizenship “should not be interpreted to detract in any way from the rights and freedoms recognized and enunciated in particular in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).”[65]

Although the preamble to the Lebanese Constitution, as amended in 1990, includes a provision that bars “the settlement of non-Lebanese in Lebanon,”[66] the Arabic term tawteen, is interpreted to mean permanent settlement.[67] The preamble also commits Lebanon to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and states that “the State embodies these principles in all sectors and scopes without exception.”[68] The UDHR states that every human being is entitled to rights and freedoms of the UDHR “without distinction of any kind” based on national origin, religion, and other enumerated grounds.[69] Lebanon is also party to the ICESCR.[70] As its treaty body, the United Nations Committee on Economic Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), has noted, “The non-discrimination provisions of articles 2.2 and 3 of the Covenant impose an additional obligation upon Governments to ensure that, where evictions do occur, appropriate measures are taken to ensure that no form of discrimination is involved.”[71]

Possible Nationality-based Discrimination

While Lebanese municipal authorities make tepid claims that their evictions of Syrian refugees have been based on violations of housing regulations, such as not registering their leases with municipalities, and other regulatory infractions of which there are widespread breaches by Lebanese citizens as well, the measures these municipalities have taken have been directed exclusively at Syrian nationals and not Lebanese citizens.

Many of the Syrian refugees interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they had been living in buildings or neighborhoods with both Lebanese and Syrian residents, but that municipal authorities only targeted Syrians for eviction. Both the evictions themselves, targeting just Syrians, and the rhetoric attached to them, as well as the inconsistency among municipalities in attributing evictions to labor and residency regulation violations, make clear that Syrians in these communities were targeted based on their nationality.

Riad, 25, who was evicted from Hadath in early January 2018, said his apartment building had a mix of Lebanese and Syrian neighbors, and that everyone got along. He said that two months before the municipal police came to his door to demand that they leave, they had approached the building’s doorman, who is also Riad’s uncle. His uncle told Riad that the municipal police had asked him to provide the names and apartment numbers of all Syrians in the building and instructed him to inform all the Syrians that they had to leave. Riad said that two months later when they came back, “the [municipal] police went floor by floor and only knocked on Syrian doors.”[72]

Possible Religious-based Discrimination

Some Lebanese Christian leaders have called for Syrian refugees to go home. Within days of the death of Raya Chidiac, Christian Maronite Patriarch Beshara Boutros Rai said that “this situation has become unbearable,” and called for the return of Syrian refugees to their country. Suggesting that it was time for Lebanese to take matters into their own hands, he said, “We should not wait for the International Community to make the decisions, because they have their own accounts.”[73]

To date, all of the municipalities identified by UNHCR that have been involved in forcibly evicting Syrian refugees, except for Tamnine al-Tahta, have been predominantly Christian.[74] Most Syrian refugee evictees interviewed by Human Rights Watch attributed their eviction, in part, to their religious identity, but said that those same municipal officials who evicted them allowed Christian refugees from Syria and elsewhere to stay, although UNHCR notes that it has recorded evictions of Christian refugees in Qaa in 2016 and in Zahle in 2017.[75] Omar, a 29-year-old male from Deir al-Zour, who was evicted from Hadath and was living in an abandoned, half-constructed building in Mazraet Yachouh in the Matn district of Mount Lebanon at the time of our interview, said that the only explanation he was given for his eviction was his religion:

The [municipal] police knocked on the door. I asked, ‘Did we do anything wrong?’ The police said, ‘No, just leave.’ At first, they told me I had three days to leave. I couldn’t find a place, so they gave me three more days. They said they would lock my door. I asked my neighbors why, and they said, “Only Muslims must leave.” Syrian Ashari Christians didn’t leave. Iraqi Christians didn’t leave. Sudanese Christians didn’t leave. At the end, only Syrian Muslims were asked to leave. I had a cousin who has lived here for 15 years, and they kicked him out. After my cousin left, Ashari Christians moved into his house.[76]

“They didn’t even knock on the door of a Christian [Syrian] family that lives two blocks away from me,” said Ihab, a 30-year-old refugee from Idlib who was evicted from his home in Hadath in early December 2017. “They are Syrians, but they were not expelled.”[77]

Some interviewees told Human Rights Watch that municipal police or other municipal authorities specifically told them that wearing the hijab was one of the reasons they were being evicted. Fayez, a 35-year-old refugee from Deir al-Zour, who was evicted from Hadath in mid-October 2017 and now lives in Beirut, said that municipal officials first started asking for copies of residency papers during the summer and then escalated demands to leave in September and October:

During the summer I talked with someone in the municipality. He said that I should talk to my wife and tell her not to wear the hijab. I asked if we did something wrong. I am a Sunni Muslim. When this official told me my wife should not wear the hijab, I told him that I would rather go back to Syria than to ask her to take off the hijab.[78]

We asked a Christian Lebanese resident of Hadath, who is both a sponsor of a Syrian refugee and a landlord of one prior to his forced eviction, whether he thought religious discrimination played a role in the evictions from Hadath:

Before, there were not many Muslims here, but recently there have been a lot. They came and bought lands and apartments, and this caused the municipality to react. The mayor, George Haddad, said we should not sell our homes or lands to Shi`a Muslims and that he would refuse to approve any sales to them. He said that this was Christian land. If an Ashari Christian or a Lebanese citizen comes, they will rent the places that the Syrian left, but no one here will be allowed to rent a house until the mayor gives permission to rent to that person.[79]

The head of the Administrative Department for Bcharre municipality explained why his municipality decided to expel Syrian refugees:

We are afraid that the demography of Bcharre will change. The people here love their land and don’t want to change it. This is a Christian town. There is no mosque here. We do not want to bring in refugees. There are no Christian refugees among the Syrians. We just don’t like people from outside.[80]

Ziad, a 36-year-old Muslim refugee who was being threatened with eviction in Zahle, said that he worked with Syrian Christian refugees who were not affected by the evictions. “In the gas station where I work, I am the only Muslim,” he said. “The other four employees are all Christian [Syrians]. My boss was able to fix the evictions for the Christians with the municipality. They never got an eviction notice, but I did.”[81]

IV. Illegality of Evicting Refugees from Municipalities

Requirements for Lawful Evictions under Lebanese Law

If a tenant defaults on the payment of rent to a landlord or an area where a person is living must be evacuated for security reasons, the grounds for evictions may well accord with Lebanese legal standards, but under Lebanese law they must also comply with procedural standards.[82] The key procedural requirement—and the one that is absent in the cases reported in this study—is that a court must order the eviction. In none of the cases documented in this report was the failure to pay rent the reason for eviction, and in no case in this report was the eviction initiated by a landlord. Most of the relevant provisions in Lebanese law relate to procedures to be followed by private actors to evict tenants.

Lebanese courts have interpreted Article 429 of the Penal Code to mean that owners do not have the right to evict a tenant without a court order, based on the legal principle that forbids taking the law into one’s own hands.[83] In their August 2014 study on housing, land, and property issues in Lebanon, at a time when the overwhelming reason for evictions was refugees defaulting on rent payments, UN-Habitat and UNHCR summarized the failure of refugee evictions generally in Lebanon to meet basic due process requirements:

While failure to pay rent represents a legitimate justification for eviction, the study also found that evictions often occur outside of any legal framework, and in violation of Lebanese law and international standards. The study found no evidence that evictions were carried out through a court order, as required by Lebanese law, or that they followed due process and procedures. The study also noted that many evictions were characterized by repeated threats and harassment and, in some cases, backed by the implicit or explicit threat of force by armed militia, or even some elements of the police forces.[84]

None of the refugees interviewed by Human Rights Watch had tried to challenge their evictions in court, but also none had received a court order or been informed that they had any right to challenge the lawfulness of their evictions. Human Rights Watch is not aware of any landlords who have challenged the lawfulness of evictions in court. One landlord, who requested anonymity, said that he would have liked to have challenged the eviction of his Syrian tenants and had lost rent money because of their eviction, but that he feared that the mayor would take retaliatory measures against him if he made an issue of it.[85] Others interviewed by Human Rights Watch suggested that many landlords were unwilling to challenge the legality of the evictions because many of them did not register their rental agreements with municipalities and avoided paying taxes on their rental income.[86]

Do Municipalities Have the Legal Authority to Evict Syrians from Their Homes or Expel Them from Their Municipalities?

Apart from the question of whether certain Lebanese municipalities have evicted or expelled Syrian residents for illegitimate reasons or whether they have followed proper procedures is the question whether they have the legal authority to evict Syrian residents from their homes or to expel them from their municipalities and, if so, on what basis they are authorized to do so.

There is no explicit statutory provision or case law that confirms eviction or expulsion as a proper legal sanction within the power of municipalities to impose.[87] Municipal officials frequently cite article 74 of the Municipalities Law as a general legal basis for the evictions, curfews, and other measures they have taken against Syrian refugees. Paragraph 19 authorizes municipal executives to take measures to maintain “security, safety and public health, provided that it does not interfere with powers granted by laws and regulations to State security departments.”[88] The same article also authorizes municipal executives to apply the provisions of the law “to settle the violations against building regulations.”[89] While the 40 paragraphs of Article 74 list many housing-related prerogatives of the municipal executive, including authorizing him or her to issue housing permits or “to settle the violations against building regulations,” no provision specifically authorizes the executive to evict or expel people for any reason.[90]

Municipalities have provided multiple and sometimes contradictory reasons for evicting and expelling Syrians. The head of the Administrative Department of the municipality of Bcharre explained how his town uses multiple regulations to restrict residency of Syrian refugees, without a clear legal basis:

We have regulations. We re-register people every two to three months. We have a doctor go with the police to examine their health. There are not allowed to be more than five or six people living in one shelter. The refugees are not allowed outside after 7 p.m. They need to be sponsored by a local person. Refugees without local Lebanese sponsors living in Bcharre are not allowed to live here.[91]

In addition to citing violations of housing regulations, such as too many people living in an apartment or the failure to register a lease with the municipality, municipalities also cite labor law infractions, such as working in a prohibited industry or without a work permit, and lack of valid residency in Lebanon as the basis for forced evictions. The correct penalty for these violations, however, is not eviction; there is no basis in law in Lebanon to penalize employment violations through residential eviction, and municipalities do not have the legal competence to intervene regarding labor law infractions.[92]

Registration of leases with municipalities is the responsibility of both landlords and tenants, but, in fact, both parties widely flout the requirement to register leases. The UN-Habitat/UNHCR survey found that 75 percent of surveyed tenants had no written contract with their landlord, and that “the contract is almost never registered with the municipality.”[93] The penalty for this widespread and widely ignored violation is a fine or confiscation and auctioning of properties from inside an apartment for nonpayment of the fine, but not eviction.[94]

Despite the lack of any legal connection between refugees’ legal residency in Lebanon and rights to live in their homes and local communities, Human Rights Watch found that municipal police sometimes used Syrians’ lack of legal residency in Lebanon as a basis to forcibly evict Syrians from their homes and to expel them from the municipalities where they had been living. But we found no consistency; in other cases, refugees reported to us that municipal police evicted them without inquiring whether they had valid legal residency in Lebanon.

Legal residency is a matter of immigration law in Lebanon relating to the right to remain in Lebanon as a whole, but not a question of a person’s residency in their home or locality. For the past several years, Syrians in Lebanon have faced nearly insurmountable obstacles both for registering for legal residency and for renewing their legal residency, so that 74 percent of surveyed Syrians living in Lebanon no longer have valid legal residency.[95]

That municipal police sometimes cite lack of legal residency status as a basis for evicting Syrians could be rooted in their misunderstanding of the authority vested in them by Article 74, paragraph 38 of the Municipalities Law, which allows municipal police to act as judicial police.[96] While a person who lacks legal residency in Lebanon may be subjected to arrest and detention, eviction is not a penalty in law for being out of legal immigration status. Although municipal police have arrest authority, according to a Lebanese lawyer working for an international humanitarian organization in Lebanon, the law bars them from detaining people without proper legal residency in Lebanon and instructs them to escort such people to General Security offices.[97]

When municipal police cited violations of legal residency in Lebanon, they often threatened involvement of the General Security agency. In some cases, municipal police threatened General Security involvement for failure to leave even for Syrians who had maintained their legal residency. Rasha, who at the time of writing was being threatened with eviction from Zahle, said that municipal police had come to her home three times to demand that she leave Zahle. “We asked why,” Rasha recalled, “and they said, ‘Go ask the General Security office.’ But we have valid legal residency with General Security.”[98]

Privacy Rights

Forced evictions as carried out by certain Lebanese municipalities run afoul of privacy rights, not only as enshrined in international human rights law, but also in Lebanon’s Constitution, which states, “The dwelling is inviolable. No one is entitled to enter therein except under the conditions and manners prescribed by the law.”[99]

While there are proper procedures that would authorize municipal police to enter premises where there are reasonable and probable grounds to conduct searches, some of the actions that Syrian refugees described to Human Rights Watch constitute breaches of basic privacy rights, insofar as the interference with their privacy appeared unjustified or disproportionate and unnecessary. Nawal, a 19-year old newly married refugee from Damascus, said she was walking on the street in her hijab in September 2017 when the Zahle municipal police saw her and followed her to her home:

I had taken off my hijab when there was a knock on the door. It was the [municipal] police. I asked them to wait one second so I could put on my hijab, but they pushed their way into the house. During the whole encounter, I kept asking for just one moment to let me put on my hijab, but they wouldn’t let me put it on. They wouldn’t stop harassing me until I signed a paper that said I had one week to leave, and they put this paper on our door. They came on September 25 and we had until October 5 to leave, but we left right away.[100]

Nawal’s account is consistent with those we heard from other women who were also alone in their homes when the police served notice of their eviction.

International Standards on Evictions

The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the UN treaty body which interprets the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), maintains that the right to adequate housing in the ICESCR guarantees legal protection from forced eviction. In particular, it outlines due process procedures that are essential to ensure the legality of evictions, namely:

(a) an opportunity for genuine consultation with those affected; (b) adequate and reasonable notice for all affected persons prior to the scheduled date of eviction; (c) information on the proposed evictions, and, where applicable, on the alternative purpose for which the land or housing is to be used, to be made available in reasonable time to all those affected; (d) especially where groups of people are involved, government officials or their representatives to be present during an eviction; (e) all persons carrying out the eviction to be properly identified; (f) evictions not to take place in particularly bad weather or at night unless the affected persons consent otherwise; (g) provision of legal remedies; and (h) provision, where possible, of legal aid to persons who are in need of it to seek redress from the courts.[101]

Municipal evictions in Lebanon have failed nearly all of these procedural standards, in particular, (a) there was no opportunity for genuine consultation with those affected; (b) no adequate and reasonable notice for all affected persons; (c) little to no information was provided on the proposed evictions, and, except for the Rayak evictions, no alternative explanation regarding the purpose for which the land or housing is to be used; (d) in almost all cases known to Human Rights Watch, no government officials were present during evictions, (though this appeared to be because, in the cases we documented, the evictees complied with the orders to leave within a specific period and were not physically removed); (e) although municipal police were often known to the Syrians who were being evicted, in many cases they ordered Syrians to leave without identifying themselves or the authority giving the order; (f) the late December Rayak eviction happened under bad weather conditions and some municipalities ordered Syrians to leave in winter when conditions were particularly cold; (g) In no case, was there any provision of legal remedies; and (h) therefore, no legal aid to persons who were in need of it to seek redress from the courts.

Hafez, a 57-year-old long-time resident of Hadath who said that all his papers were in order, spoke about the lack of proper procedures during his January 2018 eviction:

The municipal police kept knocking at the door. There was nothing in writing, only verbal. They were in uniform. I knew some of them. Some are clients of mine at the shop where I work. I asked them why I had to leave, and they didn’t give any explanation, but just said, “Syrians are not allowed to be here.” There was no court, no judge, no legal procedure. They did not accuse me of illegal residence because I am a legal resident. They just said, ‘You have to leave or we will put your stuff on the street.’ They came every week, then every day, then twice a day. I asked them to give me until the end of the month when the rent is up, but they wouldn’t agree, so I paid double rents.[102]