Summary

In Singapore, there is this culture of fear. Don’t speak up against the government or the government will “fix” you.

—Leslie Chew, cartoonist, Singapore, October 2015

In Singapore, even if it is true you aren’t supposed to say it.

—Alan Shadrake, author, London, November 2015

Singapore promotes itself as a bustling, modern city-state and a great place to do business. Beneath the slick surface of gleaming high-rises, however, it is a repressive place, where the government severely restricts what can be said, published, performed, read, or watched. Those who criticize the government or the judiciary, or publicly discuss race and religion, frequently find themselves facing criminal investigations and charges, or civil defamation suits and crippling damages. Peaceful public demonstrations and other assemblies are severely limited, and failure to comply with detailed restrictions on what can be said and who can participate in public gatherings frequently results in police investigations and the threat of criminal charges.

The suppression of speech and assembly is not a new phenomenon in Singapore. Leaders of the ruling Peoples’ Action Party (PAP), which has been in power for more than 50 years, have a history of bankrupting opposition politicians through civil defamation suits and jailing them for public protests. Suits against and restrictions on foreign media that report critically on the country have featured regularly since the 1970s and restrictions on public gatherings have been in place since at least 1973.

Although there has been some relaxation in the rules on public assemblies, they remain extraordinarily strict, and restrictions on participation by foreigners have only increased over time. The government has also enacted new regulations to control online media. The government now uses a combination of criminal laws, oppressive regulatory restrictions, access to funding, and civil lawsuits to control and limit critical speech and peaceful protests. And the courts have not provided a significant counterweight to executive and legislative branch overreach.

Criminal Penalties for Peaceful Speech

The laws most frequently used to prosecute peaceful expression in Singapore are contempt, sedition, and the Public Order Act, although the government has also resorted to laws against public nuisance, “wounding religious feelings,” and display of flags, among others, to silence dissent. Laws that impose criminal penalties for peaceful expression are of particular concern because of their broader chilling effect on free speech.

Singapore’s contempt laws include the archaic form of contempt known as “scandalizing the judiciary,” which is frequently used to penalize those who speak critically of the courts or allege they are somehow under government control. Author Alan Shadrake was sentenced to six weeks in prison in 2011 for “scandalizing the judiciary” in his book about the application of the death penalty in Singapore. Contempt proceedings for scandalizing the judiciary were brought against cartoonist Leslie Chew in 2013 for satirical cartoons about events in the fictional country of “Demon-cratic Singapore.” The proceedings were only terminated when he deleted the cartoons. In 2015, blogger Alex Au was fined S$8,000 for a blog post in which he speculated about the reasons for Supreme Court delays in scheduling argument of two challenges to Singapore’s law banning sodomy.[1]

In 2016, the Singapore government codified the law of contempt by passing the Administration of Justice (Protection) Act. Not only does that act entrench the offense of “scandalizing the judiciary,” it also broadly prohibits discussion of pending court proceedings by anyone other than the government itself. According to one lawyer, the restriction is so broad that “If anyone is charged, it is anybody’s guess as to what you can and cannot say, so it is best not to say anything.” The act also allows the government to obtain a court order to remove potentially contemptuous content without notifying either the author or the person who will be required to take it down.

Those who are outspoken on issues of race or religion have been targeted with Singapore’s broadly worded sedition law. In 2016, the editors of the popular online news portal The Real Singapore were prosecuted for sedition for posting articles that cast Chinese and Filipino ethnic groups in a bad light. While the authors pled guilty, acknowledging that the challenged articles had “a tendency to promote feelings of ill will and hostility,” none of the articles encouraged public disorder, much less incited violence or overt discrimination against any particular religion or ethnic group. Even so, editor Ai Takagi was sentenced to 10 months in prison and her husband and co-editor to eight months in prison, and the authorities ordered the website shut down. In 2008, two Chinese Christians were sentenced to eight weeks in prison for distributing pamphlets that were found to be offensive to Muslims, even though they had been distributing similar tracts promoting Christianity for almost 20 years.

When teenager Amos Yee posted a video online criticizing the late prime minister Lee Kuan Yew after his death in 2015, the authorities turned to a provision of the penal code and prosecuted him for “wounding religious feelings” based on a 30-second segment in the nearly nine-minute-long video in which he compared the former prime minister and Jesus Christ, criticizing both as “power-hungry and malicious” and stating that the followers of both had been misled. He was convicted and sentenced to three weeks in prison for wounding religious feelings and an additional week on a separate obscenity charge.

The authorities have also used investigations under Singapore’s Parliamentary Elections Act to target and harass outspoken activists and opposition supporters. In May 2016, the police questioned Teo Soh Lung, who had been detained under the abusive Internal Security Act (ISA) in the 1980s, and blogger and political activist Roy Ngerng for hours, searching their homes and seizing computers, phones, and other devices on the grounds that comments they had posted on their personal Facebook pages violated rules on advertising during the “cooling off period” before a by-election that month in Bukit Batok. The publisher of online news site The Independent Singapore, Kumaran Pillai, was similarly questioned, as was the news site’s editor Ravi Philemon, and Alfred Dodwell, a director of The Independent and one of the few lawyers in Singapore who is willing to represent activists in speech-related cases. All three were given “stern warnings” in lieu of prosecution. When asked about the impact of the warning, Pillai responded, “I think the warning is for people not to associate themselves with me and The Independent. If they do and go down that path this is what they will get themselves into. It is a warning for the rest.”

Restrictions on Peaceful Assembly

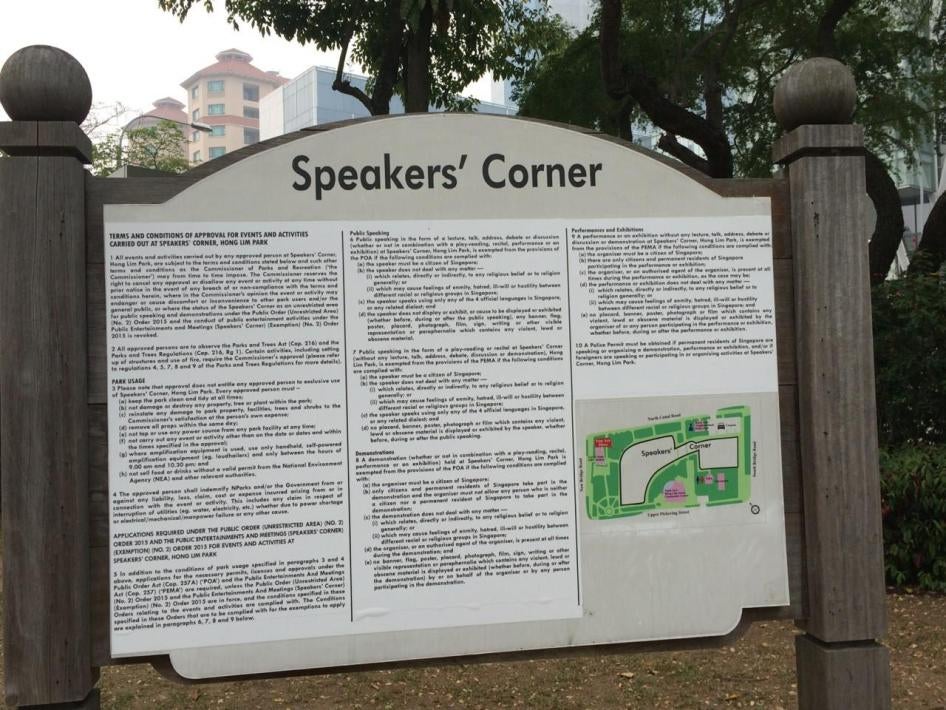

The right to peaceful assembly is extraordinarily restricted in Singapore. The only place a resident of Singapore can hold a public assembly without a permit from the government is at “Speakers’ Corner,” an area of tiny Hong Lim Park. Even then, a police permit is required if foreigners are involved in any way, if the topic in any way touches on religion, or if the topic is one that “may cause feelings of enmity, hatred, ill will or hostility between different racial or religious groups in Singapore.”

Indoor meetings require a permit unless no foreigners are involved, the topic to be covered is in no way related to race or religion, and the organizer is present at all times.

The definition of “public assembly” in the Public Order Act is extremely broad, and has been interpreted to encompass everything from handling out leaflets on the death penalty to an individual standing silently holding a placard. Even a candlelight vigil to support the family of a man about to be executed has been treated as a “public assembly” that requires a permit. Said one activist:

If five people are together, they are an assembly and they can question you. If you try walking two by two they say you are a protest. If you all wear the same color t-shirt in a shopping center to protest something, they can arrest you.

Permits for “cause-related” assemblies outside of Hong Lim Park are rarely, if ever, granted. Among the many applications denied by the authorities were applications to hold a march for workers’ rights on Labour Day in 2012 and a one-woman march in March 2011 to draw attention to the fact that single women are not allowed to purchase flats in public housing buildings until they are 35. In April 2017, the Public Order Act was specifically amended to authorize the commissioner of police to deny a permit for any “cause-related” assembly if non-citizens are to be involved in any way.

Even assemblies at Speakers’ Corner that do not require a permit face numerous restrictions. On October 31, 2016, the rules governing Speakers’ Corner were amended to prohibit any foreign company from sponsoring events in that space, and to expand the ban on participation by foreigners. Under the new rules, someone merely observing the protest is considered a “participant” and thus any foreign observer is at risk of criminal prosecution, as is the organizer of the assembly. The police informed the organizers of the 2017 annual gay pride event, Pink Dot — the first major event to be held after the rule change — that they would be required to place barricades around Speakers’ Corner and check the identification card of every attendee in order to comply with the law.

Participating in a protest at Speakers’ Corner can be intimidating for many. The area is covered by CCTV cameras and assemblies are frequently subject to intrusive police surveillance. As one activist noted, “At every protest, there will be plainclothes officers around. They will make their presence known, so people feel the fear that they are being watched.” According to another activist, the aggressive police presence and use of CCTV stigmatizes participation in protests: “It makes people look at these kinds of activities in a very negative light and discourages participation.”

Those who hold protests at Speakers’ Corner frequently find themselves the targets of police scrutiny. Jolovan Wham was investigated and given a “stern warning” by the police after two citizens of Hong Kong participated in a gathering he held in support of Occupy Hong Kong in October 2014, despite having repeatedly informed those attending the event that non-citizens were not permitted to participate. Most of the participants at a “Yellow Sit-in” held in support of the Malaysia Bersih rally in November 2016 were held and questioned by the police when the rally ended. The organizers of a protest in September 2014 over the handling of the country’s Central Provident Fund were charged with holding an unauthorized protest because they had checked the box marked “speeches” rather than the box marked “protest” on the online National Parks Board application form.

Violations of the restrictions on public assemblies are criminal offenses and the authorities routinely question and harass those who participate. As a result, many are afraid to do so. As one activist said, “There are people who say ‘I support you, but I don’t dare come to your protests.’”

The few who attempt to hold protests without a permit outside of Hong Lim Park are generally arrested and frequently prosecuted, including two men who were simply standing outside the complex that houses the prime minister’s office in April 2015 holding placards that stated “Injustice” and “You can’t silence the people.” In November 2017, activist Jolovan Wham was criminally charged for his involvement in three events held outside Hong Lim Park without a police permit.

Non-Criminal Penalties for Peaceful Speech

The most frequently used tool to penalize speech critical of the government in Singapore is civil defamation, which has been used extensively by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong and his predecessors to sue, and often bankrupt, their critics, and to intimidate foreign media reporting on Singapore. The repeated award of large, disproportionate damages against those who oppose government policies and practices has for many years had a severe chilling effect on critical speech and news reporting in Singapore. Foreign and Singaporean journalists, such as Terry Xu, editor-in-chief of The Online Citizen, concede that the country’s defamation laws have curtailed their reporting.

In 2014, for example, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong sued blogger Roy Ngerng for defamation over a blog post about the government’s handling of the Central Provident Fund (CPF), the country’s mandatory pension fund. In one blog post, Ngerng included two charts comparing the way the CPF was being invested in other funds with the way City Harvest, a church prosecuted for financial fraud, had invested its funds. Lee sued, claiming that the post implied he had misappropriated money from the fund. Although Ngerng contended that his criticism was focused on the lack of transparency in the government’s management of the money and not intended as a criticism of the prime minister, the court awarded Lee S$100,000 in general damages, S$50,000 in aggravated damages, plus S$29,000 in legal costs. Ngerng, who was fired from his job in the wake of the defamation suit, has agreed to a payment plan under which he is going to be paying off the damages for the next 17 years.

Regulatory Restrictions on Online Media

With the print and broadcast media effectively under government control, alternative voices have turned to the internet. In response, the government has increased its regulation of internet content providers.

Internet content providers are automatically given a license under the Broadcast Act and are required to comply with the Condition of Class License and the Internet Code of Practice. Under the license conditions, the internet service provider must remove any material that the Media Development Authority determines is against the public interest, public order, or national harmony, or offends against good taste or decency. Singapore’s Internet Code of Practice also requires an internet content provider to ensure that material posted online does not include any “prohibited content,” which is defined broadly to include material that is objectionable “on the grounds of public interest, public morality, public order, public security, national harmony, or is otherwise prohibited by applicable Singapore laws.”

Websites found to be engaged in discussion of political or religious issues relating to Singapore can be required to undertake additional registration procedures and are subjected to additional restrictions. Several socio-political websites, including The Independent Singapore, have been required to register under this provision. They are subject to detailed financial reporting requirements and precluded from accepting any foreign funding.

On June 1, 2013, Singapore tightened restrictions on the most popular news websites. Under the revised rules, the Media Development Authority can choose to exclude from the automatic licensing provision any website that is accessed from at least 50,000 different internet protocol addresses in Singapore in a month and that contains at least one Singapore news program or article per week. Websites receiving notification of such exclusion are required to individually register, to remove content that is in breach of content standards within 24 hours, and to post a performance bond of S$50,000. In July 2015, socio-political website Mothership.sg was notified that it met the criteria for individual licensing and was required to post a performance bond.

The government can also unilaterally declare that a website is a “political association” under the Political Donations Act and thus subject to stringent reporting requirements. Socio-political website The Online Citizen was gazetted as a political association in 2011. According to one individual involved, “The forms and reporting obligations are quite onerous… It is pretty difficult even for regular civil society activists to figure this stuff out.”

Access to Funding and Venues, and “OB” Markers

Another tool used by the government to control expression is to restrict access to funding and venues. Singapore is a small country and the government owns or controls many of the arts venues and studio spaces. The National Arts Council is a major source of funding for many playwrights, directors, filmmakers, and authors. Funding or use of a venue comes with its own set of rules and regulations, violation of which can lead to loss of funding or loss of use of the space.

Many of the rules are broad and ambiguous, such as forbidding “offensive” material. According to theatre director Sasitharan Thirulanan, “It is much more onerous and difficult to work with this ambiguous situation. I think it is deliberately kept ambiguous to make people be even more cautious. The more established you are, the more pressure you feel. The problem in Singapore is that so much of it is invisible and unclear.”

While the government has no obligation to fund the arts, the support that it does provide should not be allocated on discriminatory grounds nor violate the free expression rights of those provided support. In practice the government uses funding and the threat of withdrawal of funding to try to control content. In the best-known example, funding for Sonny Liew’s book The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye, which tells the history of Singapore in graphic novel form, was withdrawn the day before the scheduled book launch in May 2015. The National Arts Council stated that, “The retelling of Singapore’s history in the work potentially undermines the authority or legitimacy of the Government and its public institutions, and thus breaches our funding guidelines.” The author and publisher had to return more than S$6,400, the portion of the grant that had already been disbursed to them.

Even beyond the written regulations are the unwritten “OB markers” or “out of bounds markers” that demarcate the boundary between what is permitted. According to Thirunalan,

At least one MP [member of parliament] said that the OB markers are like wearing a pair of UV glasses — if you have them on you know where the lines are... For most of us, we don’t know where those lines are. Often those lines are enforced through whispers in the air, or telephone calls, or quiet conversations saying, “you shouldn’t be doing this.”

Fear and Self-Censorship

The existence of criminal penalties for any form of speech that crosses an often-unclear line has been described as a “sword of Damocles” hanging over everyone’s head. The government appears to resort to criminal investigation or defamation lawsuits at every deemed affront, and it wields the laws in a manner so harsh that it creates a real sense of fear and has a chilling effect on critical speech.

According to one student activist, the level of self-censorship and fear is so high that when he tried to organize an informal session to discuss politics and the issues during the 2015 election, students told him they would rather not because they might get into trouble. “That is the genius of the system,” he said. “It is really about a culture of fear, rather than throwing people in jail.”

The fear is heightened by the fact that many of the speech and assembly-related offenses have been made “arrestable” offenses within the meaning of the Code of Criminal Procedure. Alleged arrestable offenses permit the police to search homes, offices, or other locations without a warrant and seize anything they deem relevant to an alleged offense. As noted above, when activists Roy Ngerng and Teo Soh Lung were investigated for allegedly violating the rules on posting election advertising the day before a by-election, the police searched their homes and seized mobile phones, computers, thumb drives, and other items, even though neither denied posting the comments that were the subject of the investigations. Similarly, when Rachel Zeng was investigated for helping to organize a forum in November 2016 at which a foreigner spoke via Skype without obtaining the appropriate permit, the police searched her home and seized her laptop, even though they had already seized the borrowed computer that she had used for the event.

One activist noted that, when deciding whether a permit was needed for a particular film screening, “The question wasn’t whether we needed a permit for a film screening. The question was ‘Am I okay with the risk of having my house searched, my laptop examined, etc.,’ because it is an arrestable offense. There is definitely a chilling effect.”

Through careful selection of both those targeted and the laws used against them, the government effectively silences its critics and sends a message to others who might consider speaking out. As cartoonist Leslie Chew told Human Rights Watch in October 2015, “It is less that they want to sue someone than that they want to send a message to others not to say things—to perpetuate the culture of fear… They slaughter the chicken to scare the monkeys.”

The pervasive fear that the government will retaliate in some way was repeatedly cited as a reason for self-censorship. Whether accurate or not, there is a real sense that, if you challenge the government of Singapore, you will pay a price. Whether it is criminal prosecution, a government job, funding from the Arts Council for a theatre company or access to studio space, grants from the government for a project, or the imposition of additional regulatory burdens, there are many ways the government can penalize people for dissent.

Key Recommendations

To the Prime Minister and the Government of Singapore

- Develop a clear plan and timetable for the repeal or amendment of all laws inconsistent with international human rights standards, as recommended at the end of this report. Where legislation is to be amended, consult thoroughly with civil society groups in a transparent and public way.

- Drop all prosecutions and close all investigations that violate the rights to freedom of expression or peaceful assembly.

- Instruct all police departments that it is their duty to facilitate peaceful assemblies, not to hinder them. Persons and groups who are organizing assemblies or rallies should be permitted to hold their events within sight and sound of their intended audience, and the police should take appropriate steps to protect the safety of all participants.

- End the use of warrantless arrests and searches for offenses relating to peaceful expression and assembly.

Methodology

This report was researched and written between August 2015 and November 2017. It is based on an analysis of Singaporean laws used to restrict freedom of expression and peaceful assembly, and on interviews as described below. It also draws on court judgments and news reports concerning criminal and civil proceedings in relevant cases, and public statements by the government.

Human Rights Watch interviewed in Singapore 34 lawyers, opposition politicians, journalists, activists, members of nongovernmental organizations, and academics, some of them multiple times. Further in-person interviews were conducted in London. Telephone and Skype interviews and email correspondence continued until the time of publication. Interviews were conducted in English; no incentives were offered or provided to interviewees. A Singaporean lawyer provided guidance on Singapore laws and an outside review of the report.

Some of those interviewed requested that they not be quoted by name due to fear of possible repercussions. In such cases, the interviewees are identified by their role (i.e. activist or lawyer) and the month of the interview. Prior to publication of the report, Human Rights Watch sought to reconfirm with all those who had indicated a willingness to be quoted by name whether that was still acceptable. Several individuals indicated that, given the situation in Singapore, they had changed their minds and wished not to be quoted by name. For those with Chinese names, Human Rights Watch has followed the convention of placing the individual’s surname first.

In October 2017, Human Rights Watch sent a letter to four members of the Singapore government requesting their input. The letter, a copy of which is contained in Appendix 1, was sent by fax, email, and registered mail to Prime Minister Lee Hsein Loong, Minister for Home Affairs K. Shanmugam, Minister for Communications and Information Yaacob Ibrahim, and Minister for Foreign Affairs Vivian Balakrishnan. Human Rights Watch had not received a response at time of publication.

This report is not a comprehensive review of all laws that criminalize free speech in Singapore, but discusses the laws that have proven to be most prone to misuse and abuse.

Background

The city-state of Singapore has been ruled by the People’s Action Party (PAP) since gaining independence from Great Britain in 1959, with Lee Kuan Yew serving as prime minister for the first 31 years. His son Lee Hsien Loong has been prime minister since 2004.

No member of an opposition party served in Parliament from independence until 1981, when J.B. Jeyaretnam of the Workers’ Party was elected in a by-election. There have never been more than six members of the opposition among the 89 elected members of Parliament at any one time.[2] The PAP’s political dominance has been maintained, in part, through strict limitations on election campaigning, the use of criminal laws and civil suits against prominent opposition figures and political activists, and control over the mainstream media.

Detention Without Trial in Singapore’s First Decades

Singapore became a self-governing Crown Colony in 1959 under the leadership of Lee Kuan Yew and the PAP. Dissension within the party, however, led to a split and to the formation on July 29, 1961 of the Barisan Sosialis (“Socialist Front”) under the leadership of Lim Chin Siong. The left-leaning Barisan Sosialis opposed the government’s proposed merger with Malaya, Sarawak, and North Borneo and called for its supporters to cast blank ballots in a referendum to be held on the terms of the merger. After a hard-fought campaign, the referendum passed in a vote held on September 1, 1962.[3]

In the early hours of February 2, 1963, the Singapore security services arrested 107 opposition politicians, trade union leaders, and others, including Lim Chin Siong and 23 members of Barisan Sosialis. The government justified the arrests, code named “Operation Cold Store,” as necessary “to safeguard the defense of Singapore and of the territories of the proposed federation of Malaysia,” accusing those arrested of being communists.[4] Those apprehended were detained without trial under the Preservation of Public Security Ordinance (PPSSO), some for many years. Said Zahari, the former editor of Utusan Melayu who had been elected head of opposition Parti Rakyat Singapura a few days before his arrest, was detained without trial for 17 years.

When Singapore merged with Malaya on September 16, 1963, Malaya’s Internal Security Act (ISA), enacted in 1960 during a national state of emergency as a temporary measure to fight a communist rebellion, came into force in Singapore. Like the PPSO, the ISA permitted detention without charge or trial. Between 1963 and 1965, the Singapore legislature passed laws to replace various sections of the PPSO with provisions of the Malayan ISA. Finally, when Singapore announced its independence from Malaysia on August 9, 1965, the Malayan ISA was made applicable to Singapore.[5]

The government conducted a wave of arrests of people for alleged communist subversion through the 1970s and 1980s, with at least 690 people detained without trial under the ISA. Among those detained under the ISA were four executives of the leading Chinese language daily Nanyang Siang Pau, who were arrested and held without trial starting in May 1971 for “glamourizing the communist system and working up communal emotions over Chinese language and culture.”[6]

In May 1987, the government launched “Operation Spectrum,” a crackdown on political dissent, arresting 16 social activists and volunteers, many of them lay members of the Catholic church, accusing them of being part of a “Marxist conspiracy” to undermine the government. Another six activists were arrested in June 1987. After releasing 21 of the 22 by the end of 1987, subject to restrictions on their freedom of movement and association, the authorities rearrested eight in April 1988 after they signed a public statement denying the accusations against them and describing their mistreatment in detention. The government also arrested two lawyers who had defended the detainees, as well as another former detainee who had not signed the April statement but was accused of helping to draft and distribute it.[7]

On December 8, 1988, the Singapore Court of Appeal ordered four of the detainees released on technical grounds, in a decision that suggested that Singapore courts had some power to review the substantive grounds of ISA detention.[8] The authorities responded by immediately re-arresting all four detainees and amending both the Constitution and the ISA to limit judicial scrutiny to purely technical grounds.[9] At the same time, the government amended the ISA to abolish the right to appeal such cases to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London, removing the last possibility of independent judicial review.[10] Ultimately, lawyer Teo Soh Lung was detained for more than two years without trial, and social activist Vincent Cheng was detained for three years.

Thirty years later, Operation Spectrum continues to cast a long shadow over Singapore’s civil society. The ISA appears to currently be used primarily against those accused of being Muslim militants, but fear of the law remains widespread. While specific numbers of detainees are difficult to access, as of October 2016, at least 17 individuals were being held without trial under the ISA, some of whom have been detained for more than 15 years.[11]

Use of Defamation and Contempt Laws against Political Opponents

The Singapore government has long targeted opposition politicians with civil suits and criminal charges, often related to statements made during political campaign rallies.

The late J.B. Jeyaretnam became secretary-general of the opposition Workers’ Party in 1971. In 1976 he faced the first of a several defamation suits filed by members of the ruling party, most notably by then-Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew. The suit claimed that Lee had been defamed when Jeyaretnam stated during an election rally that a bank for which Lee’s brother was a director had been given a banking license when other companies applying for banking licenses had been unable to obtain them. Jeyaretnam was found liable and ordered to pay Lee damages of S$130,000, with total costs amounting to S$500,000 (equivalent to S$1,185,741 or $US872,895 in 2017).

When Jeyaretnam was re-elected to Parliament in 1984 he became the target of a series of criminal charges that he alleged were intended to remove him from Parliament and prevent him from taking part in future elections. In 1986, he was found guilty of misrepresenting his party accounts and fined S$5,000 — a sentence sufficient to disqualify him from serving in Parliament and prevent him from standing in parliamentary elections for a period of five years. He appealed to the Privy Council in London, then Singapore’s highest court of appeal.[12] The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council reversed the judgment in 1988, finding that Jeyaretnam had suffered “a grievous injustice.”[13] However, the president of Singapore refused to lift the convictions and Jeyaretnam was barred from running for office until 1991.

Despite the ban, he campaigned for Workers’ Party candidates during the 1988 election. Lee Kuan Yew again sued him for defamation, this time over statements made at an election rally during which he questioned the government’s handling of the suicide of the minster for national development. A court found Jeyaretnam liable and ordered him to pay Lee damages of S$260,000, together with interest and costs.[14]

In 1990, contempt of court proceedings were bought against Workers’ Party candidate Gopalan Nair for an election rally speech in which he allegedly cast aspersions on the system of promotion of judges. A court found him guilty and fined him S$8,000, and later ordered him to pay S$13,000 to the government in legal costs.[15]

In 1995, PAP officials sued Jeyaratnam for defamation over an article criticizing the organizers of a campaign to promote use of the Tamil language that had been published in the Workers’ Party newsletter when Jeyaretnam was its editor. He was again found liable and ordered to pay damages of S$235,000.[16]

In 1997, Tang Liang Hong, a Workers’ Party parliamentary candidate, filed police reports alleging that the PAP leadership had defamed him during the campaign by publicly labeling him an “anti-Christian, Chinese chauvinist.” The PAP leaders listed in the police reports alleged they had been defamed by Tang Liang Hong, sued, and were awarded damages of S$8.08 million, reduced on appeal to S$4.53 million. Tang Liang Hong was subsequently declared bankrupt.[17]

Jeyaretnam re-entered Parliament after the 1997 elections, when the Workers’ Party selected him as a Non-Constituency Member of Parliament. In the wake of the election, he faced multiple defamation suits by then-Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong, PAP ministers, and members of Parliament for saying at an election rally that Tang Liang Hong had just handed him two police reports he had made against the prime minister and “his people.”[18] He was ordered to pay damages of S$20,000 to Goh, who described the amount as "derisory" and appealed. On appeal, the court increased the damages to S$100,000 and ordered Jeyaretnam to pay the full costs of the appeal.[19]

In 2001, after he was unable to pay the final installment on the damages from the 1995 defamation case, Jeyaretnam was declared bankrupt. As undischarged bankrupts are barred from serving in Parliament, he lost his non-constituency seat.[20] Jeyaretnam was not discharged from bankruptcy until May 2007. He died in September 2008.[21]

The leader of the second major opposition party, Chee Soon Juan of the Singapore Democratic Party, has also been repeatedly sued for defamation by members of the ruling party. Then-Prime Minister Goh and Lee Kuan Yew sued Chee for defamation in 2005 for remarks questioning the propriety of a US$10 billion loan to the Suharto government of Indonesia. He was found liable and the court assessed damages of S$300,000 to Goh and S$200,000 to Lee.[22] In February 2006, he was declared bankrupt for failing to pay the damages, rendering him ineligible to serve in Parliament.[23]

When Chee challenged the fairness of the bankruptcy proceedings, he was held in contempt of court and sentenced to one day in jail and a fine of S$6000.[24] He refused to pay the fine and was sentenced to another seven days of imprisonment.[25] In 2008, Chee and his sister Chee Siok Chin were ordered to pay Lee Kuan Yew, who then held the title of Minister Mentor, and Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong US$416,000 in damages for a 2006 article in the SDP’s newsletter. The article had compared how the Singapore government was run to a scandal at a well-known charity.[26] When Chee said that justice had been “kicked” and “raped” during the defamation case against him, he was again held in contempt of court and sentenced to 12 days in jail.[27]

Restrictions on Public Assemblies

Singapore has long imposed strict controls over public gatherings, whether held indoors or outside. The Public Entertainments Act 1973 required groups or organizations to apply for a police permit to hold any gathering open to the public. The law had a serious impact on political speech since it required those wishing to speak publicly to apply for a license, which was often denied. Despite arguments that political speeches were not “entertainment,” the law was repeatedly used to bar speeches by opposition political figures. For example, in 1999 Chiam See Tong of the Singapore Progressive Party was denied a license to make a political speech at a dinner held by his party. He was only permitted to make a short thank-you speech.[28]

Chee Soon Juan was repeatedly charged with violating the act. In 1998, he was charged with giving a talk without a license and challenged the law on constitutional grounds. The court rejected his argument and he was found guilty and fined S$1400. He chose to spend seven days in jail rather than pay the fine.[29] On January 5, 1999, he spoke at Raffles Place without a permit. He was charged with violating the Public Entertainments Act, convicted and fined S$2,500. He refused to pay the fine and instead spent 12 days in jail.[30]

In September 2000, the government made a concession to public demands for more freedom of speech by establishing “Speakers’ Corner” as an ostensible “free speech” venue. However, the venue came with strict rules: any speaker must be a Singapore citizen, must register with the police before speaking, and must not speak “on any matter which relates directly or indirectly to any religious beliefs or religion,” or on any matter “that may cause feelings of enmity, hatred, ill will or hostility between different racial or religious groups in Singapore.[31]

A few months later, the Public Entertainments Act was amended to include the term “meetings” and became the Public Entertainments and Meetings Act (PEMA). Fines for holding public talks without a police permit were increased from S$5000 to S$10,000.[32] The police clarified in December 2000 that Speakers’ Corner could not be used for demonstrations or marches without a permit, noting that the freedom to speak at the venue without applying for a Public Entertainment license “does not give anyone the right to shout slogans or make wild gesticulations.”[33]

Prosecutions for violation of the act continued. In 2002, Chee Soon Juan applied for a permit to hold a May Day rally in front of the presidential palace but was denied on “law and order” grounds. He went ahead with the rally, was charged under the PEMA and convicted. Chee was fined S$4,000 for breaching PEMA and S$500 for trespassing, and jailed for five weeks after refusing to pay the fines.[34] SDP official Gandhi Ambalam was fined S$3000 for lack of a permit and “disorderly behaviour” and served one night in jail before paying his fine.[35]

In 2004, newly installed Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong announced that the rules on indoor gatherings would be relaxed.[36] This relaxation, however, was limited. Indoor talks could be held without a license only if they were in an enclosed space not within the hearing or view of any person who was not attending, organized by Singapore citizens, and did not involve discussion of religion or “any matter which may cause feelings of enmity, hatred, ill-will or hostility between different racial or religious groups in Singapore.” A meeting license was still required if the event involved foreign speakers.[37]

Chee Soon Juan continued his campaign to challenge the restrictions on free speech. On June 20, 2006, the authorities filed eight cases against him for speaking in public without a license in violation of PEMA between November 13, 2005 and April 22, 2006. In each instance, he spoke in a public area with street vendors for four to five minutes about upcoming elections and encouraged people to purchase copies of the The New Democrat, the party newspaper, as a way to support his party.[38] Two other SDP members were also charged. Chee was convicted in the first case and fined S$5000. He chose to serve five weeks in jail rather than pay the fine.[39] He was convicted of four additional charges, and sentenced to a fine of S$20,000 or, in the alternative, 20 weeks in prison.[40]

In 2006, a World Bank-International Monetary Fund Summit drew protests from those opposed to its policies.[41] Two years later the authorities charged Chee Soon Juan and six others with violating PEMA by handing out flyers and holding a public procession without a permit during the meetings.[42] In 2007, an ASEAN summit in Singapore led to small-scale demonstrations by Singapore activists.[43] In response, in January 2009, the government announced a review of public order laws and consideration of new laws to address civil disobedience as a means to manage and restrict demonstrations against such “mega-events.”[44]

In April 2009, Parliament passed the Public Order Act (POA), which served in part as a consolidation of PEMA and the Miscellaneous Offences Act.[45] The POA goes beyond its predecessors by requiring police permits for any gathering or meeting of one or more persons intending to demonstrate for or against a group or government; publicize a cause or campaign; or mark or commemorate any event.[46] Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong offered a national security rationale for the law, stating that the new POA was required because “stability for us is an existential issue — both economically and as a society.”[47] Speakers’ Corner was designated an “unrestricted” area, thus retaining its status as the one place where a permit was not required.[48] However, the restrictions on use of Speakers’ Corner were also retained.

Control Over the Media

The late Lee Kuan Yew once declared that freedom of the press must be “subordinate to the primacy of purpose of an elected government.”[49] Pursuant to that aim, the Newspaper and Printing Presses Act (NPPA) requires yearly renewal of licenses and empowers the authorities to limit the circulation of foreign newspapers alleged to “engage in the domestic politics of Singapore.”[50]

Singapore’s print media is dominated by Singapore Press Holdings (SPH). While not government owned, it is closely supervised by the government. Under the NPPA, newspapers must issue management shares to government nominees, opening the door to government intervention over editorial direction and senior editorial appointments.[51]

MediaCorp, which is owned by a government investment company, is the sole provider of free-to-air television channels and the main radio station operator. MediaCorp also publishes the only non-SPH Singapore daily newspaper.[52]

Civil defamation suits have also been repeatedly used to contain the media. In August 2006, Lee Kuan Yew and Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong sued the publisher of the Hong Kong-based Far Eastern Economic Review (FEER) and editor Hugo Restall for defamation based on an article titled “Singapore’s Martyr,” based on interviews with Chee Soon Juan. The article, published in the magazine’s July/August issue, compared the way the Singapore government was run with a scandal at a national charity and noted that Singaporean officials “have a remarkable record of success in winning libel suits against their critics.”[53] In the same month, FEER, along with a number of other foreign publications, was ordered to appoint a person "within Singapore authorized to accept service of any notice or legal process on behalf of the publication,” and to submit a security deposit of S$200,000 by September 11.[54] When the publication did not comply with the order, Singapore banned it and made it illegal even to possess a copy of FEER for sale or distribution in Singapore.[55]

In September 2008, the High Court ruled that FEER and its editor had defamed the Lees, rejecting arguments that the article was based on facts and fair comment, concerned matters of public interest, and was a neutral report.[56] Numerous other publications, including the Economist, the New York Times, Bloomberg, Asia Week, and Time magazine have faced defamation suits filed by Lee Kuan Yew or Lee Hsien Loong.[57]

The government has also used contempt laws against foreign media in Singapore. The Singapore authorities brought a claim against both Wall Street Journal Deputy Editor Melanie Kirkpatrick and Dow Jones, the owner of the paper, for contempt of court in 2008 for publishing a letter to the editor from Chee Soon Juan and two editorials that questioned the independence of the Singapore judiciary. Dow Jones was ordered to pay S$25,000 plus costs of S$30,000 and, in March 2009, Kirkpatrick was ordered to pay S$10,000 plus costs of S$10,000.[58]

I. International and Domestic Legal Standards

The rights to freedom of expression, association, and peaceful assembly are universally protected under international human rights conventions and customary law. These rights are not only important liberties in themselves, but they are crucial for helping to ensure that all other rights — civil, political, economic, social, and cultural — are accessible to all persons.[59]

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which has the endorsement of every member state of the United Nations, is considered broadly reflective of customary international law.[60] It sets out rights to “freedom of opinion and expression” (article 19) and “peaceful assembly and association” (article 20).[61] The Universal Declaration defines the right to freedom of expression to include “freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.”[62]

These rights are found in regional human rights treaties, including the European Convention on Human Rights, the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, and the American Convention on Human Rights, all of which draw upon the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The 2012 ASEAN Human Rights Declaration, adopted by all 10 ASEAN states including Singapore, commits each state to uphold all of the civil and political rights in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, including the rights to freedom of speech and assembly.[63]

These treaties, declarations, and the court judgments deriving from them demonstrate the global acceptance of the rights guaranteed by the Universal Declaration, and provide useful perspectives on the appropriate interpretation of those rights.

The rights to free expression, association, and assembly can be found in several widely ratified international human rights conventions, mostly notably the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).[64] While Singapore is not a state party to the ICCPR, commentary from the UN Human Rights Committee, UN special procedures, and other authoritative bodies make clear that these fundamental rights can only be limited in specific ways. The ICCPR, in article 19(3), permits governments to impose restrictions or limitations on freedom of expression only if such restrictions are provided by law and are necessary for respect of the rights or reputations of others, or for the protection of national security, public order, public health, or morals.[65]

Article 21 of the ICCPR similarly provides for the right of peaceful assembly, and states that no restrictions can be placed be placed on this right “other than those imposed in conformity with the law and which are necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security or public safety, public order (ordre public), the protection of public health or morals or the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.”[66]

The UN Human Rights Committee, the independent expert body that monitors state compliance with the ICCPR, in its General Comment No. 34 on the right to freedom of expression, states that restrictions on free expression should be interpreted narrowly and that the restrictions “may not put in jeopardy the right itself.”[67] The government may impose restrictions only if they are prescribed by legislation and meet the standard of being “necessary in a democratic society.” This implies that the limitation must respond to a pressing public need and be oriented along the basic democratic values of pluralism and tolerance. “Necessary” restrictions must also be proportionate, that is, balanced against the specific need for the restriction being put in place. The general comment also states that “restrictions must not be overbroad.”[68] Rather, to be provided by law, a restriction needs to be formulated with sufficient precision to enable an individual to regulate their conduct accordingly.[69]

Restrictions on freedom of expression to protect national security “are permissible only in serious cases of political or military threat to the entire nation.”[70] Since restrictions based on protection of national security have the potential to completely undermine freedom of expression, “particularly strict requirements must be placed on the necessity (proportionality) of a given statutory restriction.”[71]

With respect to criticism of government officials and other public figures, the Human Rights Committee has emphasized that “the value placed by the Covenant upon uninhibited expression is particularly high.” The “mere fact that forms of expression are considered to be insulting to a public figure is not sufficient to justify the imposition of penalties.” Thus, “all public figures, including those exercising the highest political authority such as heads of state and government, are legitimately subject to criticism and political opposition.”[72] The Human Rights Committee has further stressed that the scope of the right to freedom of expression “embraces even expression that may be regarded as deeply offensive.”[73]

International law permits governments to take action against advocacy of national, racial, or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to violence, discrimination, or hostility.[74] Such action should be limited as a matter of law, proportionality, and necessity like other restrictions on freedom of expression.[75]Human Rights Watch considers incitement to be an encouragement to cause imminent harm, which is not merely possible or potential harm but harm likely to be directly or immediately caused or intensified by the speech in question. “Violence” refers to a physical act and “discrimination” refers to the actual deprivation of a benefit to which similarly situated people are entitled.

When analyzed pursuant to these standards, a number of laws currently in effect in Singapore impose limitations on expression that go far beyond the restrictions that are permitted by international law.

Constitution of Singapore

Singapore’s Constitution appears to ensure respect for the rights to freedom of expression and assembly.[76] Article 14 states that every citizen “has the right to freedom of speech and expression.” However, the Constitution expressly permits Parliament to impose on that right,

such restrictions as it considers necessary or expedient in the interest of the security of Singapore or any part thereof, friendly relations with other countries, public order or morality and restrictions designed to protect the privileges of Parliament or to provide against contempt of court, defamation or incitement to any offence.

Article 14 also states that every citizen “has the right to assemble peacefully and without arms,” but subjects that right to such restrictions as Parliament “considers necessary or expedient in the interest of the security of Singapore or any part thereof or public order.” These restrictions allow a much broader basis for restrictions than under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights or the ICCPR and are thus contrary to the requirements of international law. In addition, the Constitution does not require that the restrictions be “necessary” to protect one of the interests listed, a key element of international legal protection for freedom of expression.

II. Criminalization of Peaceful Expression

The Singapore government has used a range of broadly worded laws to arrest, harass, and prosecute critical voices. Some of these laws are carried over from the British colonial era, while others have been enacted only recently. This section describes those laws, identifying provisions that do not meet international standards for the protection of freedom of expression and assembly, and examines how they have been used to criminalize the peaceful exercise of those rights.

Contempt

Until recently, contempt in Singapore was a matter of common law, not of legislation. In August 2016, Singapore “codified” and expanded the offense of contempt by enacting the controversial Administration of Justice (Protection) Act.[77] The new law provides penalties of up to S$100,000 and three years in prison for several forms of contempt of court, including the archaic offense of “scandalising the court,” a form of contempt that has been repeatedly used against those alleged to have criticized Singapore’s judiciary.[78] Moreover, contempt is made an “arrestable” offense – an offense that permits suspects to be subjected to warrantless searches and arrests.[79]

The purpose of criminal contempt laws is to prevent interference with the administration of justice. While there is no doubt that courts can restrict speech where that is necessary for the orderly functioning of the court system,[80] the Administration of Justice (Protection) Act is so broadly worded as to allow for easy abuse.

Scandalizing the Court

Under the Administration of Justice (Protection) Act, it is deemed contempt to publish anything that: (1) imputes improper motives to or impugns the integrity, propriety, or impartiality of any court; and (2) poses a risk that public confidence in the administration of justice would be undermined.[81] While the accompanying explanatory notes state that “fair criticism” is not contempt, what constitutes “fair criticism” is not defined and the determination of what is in essence a subjective test is left to the discretion of the court. Moreover, under the act it is not an acceptable defense to contend that one did not intend to scandalize the court.[82]

The statute is broader than the common law it purports to codify since, as interpreted by Singapore’s courts, to prove the common law offense of “scandalising the court” the government needed to prove that the publication carried a “real risk” of undermining public confidence in the administration of justice — a remote or fanciful risk would not suffice.[83] By contrast, under the Administration of Justice (Protection) Act, all that is required is that the publication “poses a risk” — however remote — of undermining confidence in the administration of justice.

The reliance on interpretation by individual judges also makes the scope of the violation extremely uncertain. What one judge may view as “impugning the integrity of the court” may be shrugged off by another judge. The law thus does not give clear guidance to those wishing to express opinions about the conduct of the court, contrary to the standard that laws restricting expression be formulated “with sufficient precision to enable an individual to regulate his or her conduct accordingly.”[84] Moreover, the lack of clarity as to what expression may be considered to scandalize or lower the authority of the court leaves wide scope for the restriction of speech simply on the basis that it is critical of the court and its rulings.[85] The vagueness of the offense, combined with the harshness of the potential penalty, increases the likelihood of self-censorship to avoid possible prosecution, curtailing open discussion of the administration of justice in Singapore.

The UN Human Rights Committee has stated that “all public figures, including those exercising the highest political authority such as heads of state and government, are legitimately subject to criticism and political opposition… States parties should not prohibit criticism of institutions, such as the army or the administration.”[86] Other international bodies interpreting freedom of expression, including the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, have also disfavored laws that penalize criticism of public authorities.[87] The Inter-American Court for Human Rights has specifically held that contempt is not compatible with the Inter-American Convention on Human Rights,

because it could be abused as a way to silence ideas and opinions, suppressing debate, which is critical for the effective operation of democratic institutions. Moreover, contempt legislation dissuades people from criticizing for fear of being subject to judicial actions that, in some cases, may bear monetary penalties.[88]

The United Kingdom and several other Commonwealth countries, including New Zealand, Canada, and Brunei Darussalam, have long since ceased to prosecute this type of contempt charge. As the Law Commission of the United Kingdom noted in recommending abolition of the offense of scandalizing the court,

[p]reventing criticism contributes to a public perception that judges are engaged in a cover-up and that there must be something to hide. Conversely, open criticism and investigation in those few cases where something may have gone wrong will confirm public confidence that wrongs can be remedied and that in the generality of cases the system operates correctly.[89]

Discussion of “Pending” Proceedings

The Administration of Justice (Protection) Act’s broad restrictions on discussion of ongoing court matters are also problematic. The law states that a person is guilty of contempt if he or she intentionally publishes any matter that:

prejudges an issue in a court proceeding that is pending and such prejudgment prejudices, interferes with, or poses a real risk of prejudice to or interference with, the course of any court proceeding that is pending; or otherwise prejudices, interferes with, or poses a real risk of prejudice to or interference with, the course of any court proceeding that is pending.[90]

Under the law, a case is deemed “pending” from the earliest of the time a notice or summons is issued or an arrest is made until the conclusion of the final possible appeal in the case.[91] One lawyer told Human Rights Watch that “the sub judice [pending case] rule is so broad, when someone is charged it is anybody’s guess what you can and can’t say, so it is best not to say anything. As a lawyer, I would have to advise clients not to say anything, as I can’t tell whether or not they would fall foul of the law.”[92]

While restrictions on speech that poses a substantial risk of prejudice to a fair trial are permissible under international law, they should be narrowly drawn to interfere with good faith reporting as little as possible. As the European Court of Human Rights recognized in the seminal case Sunday Times v. United Kingdom, this is of particular concern with respect to the media:

There is general recognition of the fact that the courts cannot operate in a vacuum. Whilst they are the forum for the settlement of disputes, this does not mean that there can be no prior discussion of disputes elsewhere, be it in specialised journals, in the general press or amongst the public at large. Furthermore, whilst the mass media must not overstep the bounds imposed in the interests of the proper administration of justice, it is incumbent on them to impart information and ideas concerning matters that come before the courts just as in other areas of public interest. Not only do the media have the task of imparting such information and ideas: the public also has a right to receive them.[93]

In particular, it should be presumed that a professional judge is generally capable of ignoring or resisting improper influence from commentary outside the courtroom.[94] Singapore abolished jury trials in 1969.

In contrast, while citizens are prohibited from discussing ongoing proceedings under the proposed new law, the government is permitted to comment whenever it feels it “is necessary in the public interest,” regardless of whether doing so could prejudice the ongoing proceedings and the presumption of innocence.[95] The examples provided by the law provide a troubling demonstration of the imbalance created by this provision:

A statement made by a person on behalf of the Government factually describing the circumstances of a riot, when criminal proceedings against a person charged with participation in that riot are pending, which the Government believes is necessary in order to inform the public of the riot, is not contempt of court.[96]

Since the “circumstances” of the riot are very likely to be one of the key issues in a prosecution for participating in a riot, allowing the government to make public statements about those circumstances, while the defendant, the defendant’s lawyer, and others present at the event are silenced until after the final appeal on pain of contempt creates a real risk that the government’s perspective will dominate and prejudice to the defendant will ensue.

Removal Provisions

Finally, the Administration of Justice (Protection) Act gives the attorney general the power to seek a court order requiring the removal of potentially “contemptuous” material without giving notice of his application to those most affected.[97] In fact, the law requires that the application be heard “without the presence” of the author or the person who will be ordered to take down the material.[98] The court “must” grant the order if the government makes a prima facie case that the material falls within the law’s broad definition of contempt.[99] While the author or person directed to take down material can appeal the order, an appeal does not stay the order itself.[100] Failure to comply with the order can result in a sentence of up to 12 months in prison and a fine of S$20,000.[101]

Given the breadth of the law’s definition of contempt, the scope of material potentially affected by this provision is extremely broad, allowing the government to seek removal of material simply because it is critical of the judiciary or of court decisions. Because the order is issued without informing the author of the content, the result will be a suppression of internationally protected speech, including comments on matters of public interest. The requirement that a court issue the order provides insufficient protection given that the law requires the court to do so whenever the attorney general makes a prima facie case that material falls within the broad definition of contempt.

Common Law Contempt Proceedings

Singapore’s common law of contempt has been used repeatedly against members of the political opposition and, more recently, against political cartoonists and bloggers.

Contempt Proceedings for Kangaroo T-shirts

Following the 2008 decision holding Chee Soon Juan liable for defaming Lee Kuan Yew and Lee Hsien Loong, discussed above, Isrizal Bin Mohamed Isa, Muhammad Shafi'ie Syahmi Bin Sariman, and Tan Liang Joo John attended the hearing on damages wearing t-shirts depicting kangaroos wearing judicial robes. All three were charged with and convicted of contempt for “scandalizing the judiciary.” Isa and Sariman were sentenced to seven days in jail, while Tan Liang Joo John received 15 days. Each man was also ordered to pay costs of S$5,000.[102]

Contempt Proceedings Against Author Alan Shadrake

Author Alan Shadrake was sentenced to six weeks in jail and a S$20,000 fine for “scandalizing the court” in his book Once a Jolly Hangman, about the application of Singapore's mandatory death penalty for drug trafficking offenses. The book, based on interviews with a long-time executioner in Singapore’s Changi prison, review of case files, and interviews with dozens of lawyers and death penalty opponents, alleges that the death penalty has been disproportionately applied to the young, the poor, and the less educated.

The book was printed in Malaysia and launched in Kuala Lumpur in April 2010.[103] On July 16, 2010, the day before a planned book launch in Singapore, Singapore’s Media Development Authority filed a police complaint against Shadrake for criminal defamation.[104] On the same day, the attorney general submitted an affidavit recommending that Shadrake be prosecuted for writing a book that contains passages that “scandalize the judiciary.”

Although the book launch went ahead as scheduled, in the early hours of the following morning the police came to the guest house where the 75-year-old Shadrake was staying and arrested him. As Shadrake describes it:

A while after I went to bed, there was a loud banging at the door. Then they stormed in like commandos — looking under the bed, turning the mattress upside down. I was bundled down a corridor to a side entrance, like in a movie. We went whizzing through town with a siren.[105]

The police interrogated Shadrake intensively for two days, during which he was denied access to counsel. Questioning continued for a week after he was released on bail late in the day on July 19. He was ultimately charged with criminal defamation and with “scandalizing the court” in 14 different passages in the book. Although the attorney general said he would mitigate the charges if Shadrake apologized, he refused to do so: “I wouldn’t apologize for something I believe in and something I knew to be true… In Singapore, even if it is true, you are not supposed to say it.”[106] The attorney general’s office stated that it viewed his refusal to apologize as an “aggravating fact.”[107]

At his hearing, Shadrake contended that the book constituted “fair criticism” on matters of compelling public interest. The high court rejected that defense and held 11 statements to be contemptuous, finding that “if the matter had been left unchecked, some members of the public might have believed Mr. Shadrake’s claims, and in doing so, would have lost confidence in the administration of justice in Singapore.”[108] Shadrake was sentenced to six weeks in prison, a fine of S$20,000 and court costs. The Court of Appeal affirmed the conviction with regard to nine of the statements and affirmed the sentence.[109]

Shadrake served five-and-a-half weeks in prison before being released early for good behavior.

Contempt Proceedings Against Cartoonist Leslie Chew

In May 2011, Chew Peng Ee (known as Leslie Chew), started drawing political cartoons about the fictitious country of “Demon-cratic Singapore,” which he posted on a Facebook page bearing the same name. On his Facebook page, it stated that “all characters, political parties, places and events portrayed in all my comics are purely fictional.”[110] On December 13, 2012, he received a complaint from the attorney general that one of his cartoons was disrespectful of the court. According to Chew, the cartoon depicted “the leader of my fictitious country” telling a judge to take early retirement.[111] The notice told him to take down the cartoon and apologize or he would be charged with contempt.[112] Chew refused.

On the morning of April 19, 2013, police officers came to Chew’s home and arrested him for sedition. The police confiscated his phone, computer, and hard disk, and he was held in police custody for three days before finally being released on bail the evening of April 21.[113] The sedition investigation centered on two cartoons posted on his Facebook page – the one that had been the subject of the letter of complaint, and a second one that implied that ethnic Malay population statistics in Singapore were being suppressed by the government.[114] Three months later, on July 29, 2013, the government announced that it was dropping the case.[115]

Four days before dropping the sedition case, the attorney general’s chambers commenced proceedings against Chew for contempt of court based on four cartoons posted between June 2011 and July 2012.[116] The cartoons that were the basis of the charges satirized court decisions for allegedly favoring foreigners, ruling for a celebrity and against a serviceman, imposing disparate sentences for the same offense, and joining a government vendetta against an opposition politician.[117] Charges were dropped in August 2013 only after Chew agreed to delete the four cartoons and publicly apologize. “Since they were early ones, I decided I will apologize for these four,” said Chew. “So they dropped the charges. I had to take down the ones I apologized for.”[118]

Contempt Proceedings Against Blogger Alex Au

In 2015, blogger and activist Au Wai Pang (known as Alex Au) faced contempt proceedings for “scandalising the court” in two articles he had posted on his blog in 2013. One article, posted on October 5, 2013, discussed an application for a judicial declaration that article 12 of the Singapore Constitution provides protection against discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. The application was filed by Lawrence Wee after his suit claiming that he had been harassed into resigning from his employment at Robinsons Department Store because he was gay was dismissed by the courts. Au stated, among other things, that:

I don’t have high hopes for this new suit, mostly because my confidence in the Singapore judiciary is as limp as a flag on a windless day… In fact I think Robinsons was wrong to make life so difficult for him that he had little choice but to resign (but the court found Robinsons right)… While I haven’t yet seen the details of the judgment in his suit against unfair dismissal (is it out in the public realm?) I can’t understand how the court arrived at the decision it did.[119]

While the government argued that Au’s statements constituted scandalizing contempt because they implied that Singapore’s courts were biased against homosexuals, the High Court disagreed with that analysis and held that the government had failed to prove that the statements posed a real risk of undermining confidence in the administration of justice.

The second article, posted on October 5, 2013, and titled “377 wheels come off Supreme Court’s best-laid plans,” commented on the scheduling of two constitutional challenges to Singapore’s sodomy law. Au noted that the High Court ruling in the first case had been delayed and speculated that the reason might be so that the new chief justice, who had been the attorney general at the time the first case was filed, could sit on the bench hearing the challenge. “Basically, I speculated on the inner workings of the court calendar and I was charged with scandalizing the judiciary,” he said.

When I heard about the charge it was not a happy place to be. My biggest concern was the cost angle. Cost is a major barrier to freedom of speech — you may lose a lot of money trying to defend yourself. There are very few pro bono lawyers, and even paid lawyers, willing to take these cases.[120]

Au contended that his post did not imply that the outcome of the case was predetermined in any way and that there was nothing improper with the chief justice wanting to sit on a case of constitutional importance.[121] The court disagreed, finding that the post suggested that the chief justice was partial and that the courts had acted improperly in arranging the schedule to enable him to sit on the case.[122] Au was convicted and fined S$8,000. His conviction was upheld on appeal.[123]

Contempt Proceedings Against Lawyer Eugene Thuraisingam

Lawyer Eugene Thuraisingam has represented a number of individuals on death row in Singapore. On May 19, 2017, after learning that his client Mohamed Ridzuan would be executed the following morning for trafficking 72.5 grams of heroin, he posted an emotional poem on his Facebook page. On May 26, the attorney general’s chambers filled an application to begin contempt proceedings against him, on the grounds that the following lines scandalized the judiciary:

With our million dollar men turned blind.

Pretending not to see.

Ministers, Judges and Lawyers.

Same as the accumulators of wealth.

Hiding in the dimness, like rats scavenging for scraps.

When does the new car come?

Our five stars dim tonight.

For a law that makes no sense.

A law that is cruel and unjust.[124]

On June 5, after receiving notice from the attorney-general that his post was considered contemptuous, Thuraisingam deleted the poem and posted an apology.[125] Despite doing so, the contempt proceedings went forward. Thuraisingam pled guilty to contempt and, on August 7, the court imposed a fine of S$6,000 and costs of S$6,000.[126]

Contempt Proceedings Against Li Shengwu

On July 15, 2017, following an acrimonious public dispute between his parents and Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong over the disposition of Lee Kuan Yew’s home, Lee Hsien Loong’s nephew Li Shengwu posted the following on his private Facebook page: “If you’ve been watching the latest political crisis in Singapore from a distance, but would like a summary, this is a good one. (Keep in mind, of course, that the Singapore government is very litigious and has a pliant court system. This constrains what the international media can usually report.)” The post contained a link to an April 2010 editorial published by the New York Times, entitled “Censored in Singapore.”[127]

The private post was subsequently shared widely without Li’s consent. On July 21, Li received a letter from the attorney general’s chambers demanding that he purge the contempt by deleting the post from his Facebook page and issuing a public apology.[128]

Li responded in a letter, which he also posted on Facebook, that the attorney general’s chambers had misunderstood his private post, adding he had amended the post to remove any misunderstanding, but would not take it down. Li said his criticism was directed not at the judiciary but at the Singapore government's "aggressive use" of legal rules like defamation laws to constrain reporting by international media.[129] In response the attorney general sought permission to commence contempt proceedings against Li, and the High Court granted permission on August 22.[130] The case was pending at time of writing.

Recommendations to the Singapore Government

- Repeal section 3(1)(a) of the Administration of Justice (Protection) Act to abolish the offense of “scandalizing the judiciary.”

- Amend section 3(1)(b) of the act to narrow the restriction on statements that “prejudge” a pending proceeding to those that create a substantial risk that the course of justice in the proceedings in question will be seriously impeded or prejudiced, and to make the rule equally applicable to the government and to private citizens.

- Repeal section 3(4) of the act to eliminate the government’s discretion to make even prejudicial statements about ongoing proceedings when the government determines it is “in the public interest” to do so.

- Amend section 13 of the act to give the author of allegedly contemptuous content notice and an opportunity to be heard before the court decides whether such content must be removed.

Sedition Act

Singapore’s Sedition Act, which has its origin in the 1948 sedition ordinance enacted by the British colonial authorities during a period of emergency rule, imposes criminal penalties on any person who:

(a) does or attempts to do, or makes any preparation to do, or conspires with any person to do, any act which has or which would, if done, have a seditious tendency;

(b) utters any seditious words;

(c) prints, publishes, sells, offers for sale, distributes or reproduces any seditious publication; or

(d) imports any seditious publication.[131]

The law further makes it criminal to possess any seditious publication “without lawful excuse.”[132]

The law never actually defines sedition. Instead, “seditious,” as used in the law, is said to qualify the act, speech, words, publication, or other things referred to as “having a seditious tendency.”[133] “Seditious tendency” is broadly defined in section 3(1) of the act to include speech having a tendency to “bring into hatred or contempt or to excite disaffection against” the government, or the administration of justice in Singapore, to “raise discontent or disaffection” among the inhabitants of Singapore, or to “promote feelings of ill-will and hostility between different races or classes of the population of Singapore.[134] Violation of the law carries of penalty of up to three years in prison and a fine up to S$5,000 for a first offense, and up to five years in prison for a subsequent offense.[135]

The Sedition Act goes well beyond the standard definition of sedition, which has generally been interpreted to require an intention to incite the public to violence against constituted authority or to create a public disturbance or disorder against such authority.[136] With the possible exception of subsection 3(1)(b), the law does not even require that the expression encourage unlawful activity or public disorder, much less that it pose a real risk of causing such impact.[137] Instead, it penalizes expression that simply “has a tendency” to cause ill-will, hatred, disaffection, or discontent, regardless of whether it actually has such an impact, and regardless of whether or not any of those who feel “disaffection” or “discontent” as a result are inspired to do anything other than sit at home and nurse their discontent.

Moreover, under Singapore’s Sedition Act, the intent of the speaker is irrelevant if the speech, publication, or act has a “seditious tendency.”[138] This effectively permits the imprisonment of citizens who had no intention of “exciting disaffection,” much less of undermining national security or public order, simply because someone else views their statement as having the “tendency” to do so.

The Sedition Act is further problematic in that it fails to formulate the restrictions it imposes on speech “with sufficient precision to enable the citizen to regulate his conduct.”[139] “Seditious tendency” is loosely defined with vague and subjective terms such as “ill-will,” “discontent,” and “disaffection.”[140] When a law is so vague that individuals do not know what expression may violate it, it creates an unacceptable chilling effect on free speech. Vague provisions not only give insufficient notice to citizens, but also leave the law subject to abuse by authorities.[141]

As a New Zealand law commission recommending abolition of the country’s sedition law concluded:

People may hold and express strong dissenting views. These may be both unpopular and unreasonable. But such expressions should not be branded as criminal simply because they involve dissent and political opposition to the government and authority.[142]