Summary

The psychiatrist told my mom: ‘Homosexuality is just like all the other mental diseases, like depression, anxiety, or bipolar. It can be cured…. Trust me, leave him here, he is in good hands.’

— Wen Qi (pseudonym), March 16, 2017

Homosexuality is neither a crime nor officially regarded as an illness in China. For decades, the legal status of consensual same-sex activity between men was ambiguous, but that was cleared up in the revised criminal code of 1997. In 2001, the Chinese Society of Psychiatry removed homosexuality from its list of mental disorders. This is consistent with the consensus of global medical associations that homosexuality is not a medical condition.

However, public hospitals and private clinics in China continue to offer so-called “conversion therapy,” which aims to change an individual’s sexual orientation from homosexual or bisexual to heterosexual, based on the false assumption that homosexuality is a disorder that needs to be remedied. Despite a legal framework that requires that the diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders comply with diagnostic standards and standards on the categorizations of mental disorders, Chinese authorities have not taken the necessary steps to stop public hospitals or private clinics from offering conversion therapy. The steps should include: issuing clear guidelines to all public and private hospitals and clinics indicating that conversion therapy contravenes existing law; closely monitoring medical facilities to determine whether conversion therapy is taking place; and, where it is, holding such facilities accountable, including by suspending the licenses of errant facilities or practitioners.

This report documents multiple abusive aspects of conversion therapy, including coercion and threats, physical abduction, arbitrary confinement, forced medication and injection, and use of electroshocks. It is based on interviews with 17 individuals who underwent conversion therapy under intense family and social pressure, as well as parents and rights activists.

All interviewees were emphatic about one thing: they would not have undergone conversion therapy were it not for family and social pressure. Some said their parents took them forcibly to hospitals for such therapy: Chinese society continues to strongly favor children who can pass on their family name. For individuals who are gay or lesbian, this creates intense family pressure to enter heterosexual marriages and have children. Despite all efforts, no one experienced any change to their sexual orientation.

Human Rights Watch found that, in most cases, conversion therapy took place in public hospitals, which are government-run and monitored. In a few cases, conversion therapy was conducted in privately owned psychiatric or psychological clinics, licensed and supervised by the National Health and Family Planning Commission.

Governments are obligated to safeguard the fundamental human rights of individuals within their territory or jurisdiction. The abuses that occur in conversion therapy — including involuntary confinement; verbal harassment and intimidation; lack of informed consent in writing or orally; forced use of medicine; and forced psychiatric intervention — violate domestic and international standards, and the human rights of LGBT people. These include the right to non-discrimination, the right to freedom from arbitrary deprivation of liberty, the right to privacy, the right to health, the right to freedom from non-consensual medical treatment, and, in the case of some minors, the rights of the child. Use of electroshocks have arguably amounted to acts of torture, or inhuman or degrading treatment.

China does not have a law protecting individuals from discrimination due to sexual orientation or gender identity. While the Chinese Psychological Society has issued professional guideline that prohibit discrimination due to sexual orientation during psychology counseling practice, professional associations have not prevented medical practitioners from conducting conversion therapy. Other than two known successful lawsuits, in which a gay man sued for forced conversion therapy and another for false advertising, those who conduct conversion therapy have not been scrutinized or held accountable by professional associations or the law. There are inadequate options for members of the public to file complaints or seek remedies for medical or psychiatric practices that violate Chinese domestic law and international law.

Governments are obligated to safeguard the fundamental human rights of individuals within their territory or jurisdiction, including the right to liberty, the right to non-discrimination, the right to freedom from torture, the right to privacy, the right to health, and the rights of the child. Allowing the discriminatory practice of conversion therapy in public hospitals and state-licensed clinics is inconsistent with the Chinese government's obligations under its national law, and international law.

Chinese authorities should immediately take steps to ensure that its declassification of homosexuality as a mental disorder is supported by meaningful protections. They should prohibit the forced admission of individuals without mental disease or disorder into psychiatric facilities, and establish disciplinary and accountability mechanisms to address abusive and unethical medical and psychiatric practices. Public and private health facilities should not be permitted to provide treatments that are ineffective, unethical, and harmful, including conversion therapy. As homosexuality is not an illness, there is no need for a cure.

Key Recommendations

To the National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China

- Issue regulations or guidelines that clearly prohibit public hospitals and private clinics from conducting conversion therapy.

- Strengthen the monitoring and regulation of state-run hospitals as well as private psychiatric clinics and practitioners, including by establishing an effective complaint system and conducting stop visits, to ensure that they are not conducting conversion therapy.

- Hold accountable facilities that continue to conduct conversion therapy, including by issuing warnings and ultimately revoking licenses of repeat offenders.

To the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China

- Update textbooks and ensure that the professional literature taught in universities conforms to the declassification of homosexuality as a mental disorder.

To the Chinese Psychological Association and Chinese Society of Psychiatry

- Strengthen regulation over professionals in the field of psychiatric and psychological service, in particular by placing necessary and proper scrutiny standards on licensing the practice of psychiatric and psychological treatment.

To the World Psychiatry Association (WPA)

- Ensure the Chinese member of the WPA, the Chinese Society of Psychiatry, complies with the standards and guidelines concerning the ineffectiveness of conversion therapy.

Methodology

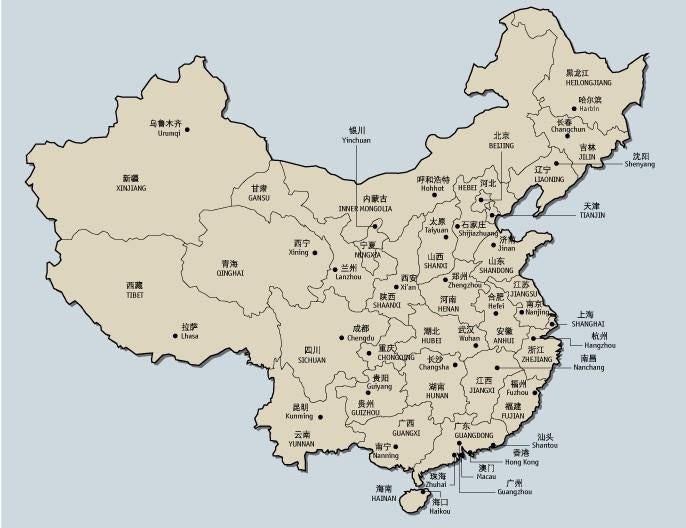

This report is based on interviews conducted between September 2016 and April 2017. Human Rights Watch interviewed 17 people who had undergone conversion therapy between 2009 and 2017 (see Chart I: Details of the 17 Interviewees and Geographic Information).

The interviewees included 14 gay men, two lesbians and two transgender women. The interviewees’ ages (at the time of undergoing conversion therapy) ranged from 15 to 35.

Among 17 interviewees, three went through conversion therapy at private psychiatric clinics, 13 underwent conversion therapy in state-run hospitals, and one received so-called "treatment" at both a public hospital and a private clinic.

The cases spanned 12 different provinces, although one interviewee withheld the details of his location, due to security concerns. The data on location distribution shows a variety of locations. All interviews, except one telephone interview, were conducted in person. All interviews were conducted in Mandarin by a researcher fluent in Mandarin.

We interviewed parents of two individuals who went through conversion therapy involuntarily, the friend of a gay man who had been subjected to conversion therapy, as well as four Chinese activists who have worked extensively with Chinese groups advocating for the equal rights of LGBT people and who have interviewed other individuals who have undergone conversion therapy in China.

The Chinese government is hostile to research by international human rights organizations and strictly limits the activities of domestic civil society organizations on human rights issues and other subjects. The names and identifying details of those with whom we spoke have been withheld to protect them from government reprisal. We have used pseudonyms for all interviewees, including those who had gone through conversion therapy, as well as their family members, and activists.

All of those interviewed were informed of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and the ways in which the information would be used. All interviewees provided oral consent to be interviewed. All were informed that they could decline to answer questions or could end the interview at any time. No financial or other incentives were provided to individuals in exchange for their interviews.

Human Rights Watch has sent letters to the Chinese National Health and Family Planning Commission and to the Chinese Society of Psychiatry with questions related to the findings of this report. (See Appendix II). Human Rights Watch had not received any response at the time of publication.

Human Rights Watch has also examined media reports, as well as statements and comments made by officials, and other relevant material such as advertisements for conversion therapy on the internet and in newspapers. We also referred to the websites of some psychiatric service providers, reports by other rights groups, and reports available in public media, among others.

I. Background

Conversion Therapy

Conversion therapy refers t0 purportedly psychiatric or psychological "treatment," or spiritual counseling, aimed at changing an individuals' sexual orientation, from homosexuality or bisexuality to heterosexuality. Conversion therapy can also aim to change gender identity, but this report focuses on sexual orientation change efforts, consistent with the experience of interviewees. All cases documented in the report were attempts to change an individual’s sexual orientation. Two interviewees who identify as transgender women, Liu Xiaoyun and Li Qi, identified as gay at the time of conversion therapy. This means homosexuality was the presumed “disorder” being “treated”. Despite all efforts, no one experienced any change to their sexual orientation.

According to the interviews Human Rights Watch conducted, conversion therapy in China involves multiple techniques, including psychiatric consultation, hypnotherapy, medication, aversion therapy, and electroshock treatment.

There is now a global consensus among professional medical bodies that conversion therapy with the intent to "cure" homosexuality is ineffective, unethical, and potentially harmful.

The World Psychiatric Association (WPA), an association of national psychiatric societies across 118 different countries, issued a statement in March 2016 that, “it has been decades since modern medicine abandoned pathologizing same-sex orientation and behavior.” It also stated that “[p]sychiatrists have a social responsibility to advocate for a reduction in social inequalities for all individuals, including inequalities related to gender identity and sexual orientation.” The association concluded:

WPA believes strongly in evidence-based treatment. There is no sound scientific evidence that innate sexual orientation can be changed. Furthermore, so-called treatments of homosexuality can create a setting in which prejudice and discrimination flourish, and they can be potentially harmful. The provision of any intervention purporting to “treat” something that is not a disorder is wholly unethical.[1]

Multiple national professional associations globally have affirmed this position (see Appendix I).

A 2015 joint statement issued by 12 United Nations agencies, including the World Health Organization (WHO), called on states to protect LGBT people from violence, torture, and ill-treatment, including by ending “unethical and harmful so-called ‘therapies’ to change sexual orientation.”[2]

States have taken different approaches to ending conversion therapy. In the United States, nine states and the District of Columbia have laws that limit conversion therapy. There have been legislative initiatives to ban conversion therapy in Australia, Brazil, Chile, Israel, Switzerland, Taiwan and the United Kingdom, among other countries. At time of writing, Malta was the only country in the world to impose a nationwide ban on conversion therapy.

Homosexuality and the Rights of LGBT People in China

Homosexuality has been depicted in Chinese arts and documented in Chinese literature since ancient times. One of the earliest notions of homosexuality in Chinese history is the first-century Chinese Emperor Ai of the Han Dynasty (27 to 1 BC), who, upon waking from an afternoon nap, cut off his sleeve so as not to wake his male lover, Dong Xiang, who was sleeping across it. For 2000 years, same-sex love has been referred to in China as “the passion of the cut sleeve.”

Historically, social attitudes and public policy toward homosexuality have shifted in different dynasties.

Since 1907, when “ji jian” (anal sex between men) was removed from the penal code, laws governing consensual same sex intimacy between men in China have been vague and inconsistent, subject to court interpretation. The Criminal Code of 1979 contained no express prohibition against male same-sex activity, but a 1984 National Supreme People’s Court case expressly included “ji jian” under the rubric of “other hooligan activities.” For this reason, the legal status of consensual male same-sex conduct in China existed in a zone of ambiguity under the rubric of “hooliganism,” until revision of the Criminal Code in 1997. The revised criminal code did away with “hooliganism” and stipulated that “all crimes must be expressly prescribed by the law.” Taken together, these provisions effectively meant that consensual anal sex between men was no longer criminalized.[3] Sex between women has never been criminalized.

In 2001, the Chinese Society of Psychiatry modified the Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders (CCMD) (中国精神疾病分类方案与诊断标准) and removed homosexuality from its list of mental disorders.[4]

While these important developments could have cleared the way for gay and lesbian people to live openly and assert equal rights, there has been little progress in a number of areas, including LGBT-inclusive non-discrimination legislation, adequate information and education on HIV/AIDS and other health-related issues, protection from employment discrimination under China’s labor law, or protection of the individual autonomy and privacy of transgender people.

However, in recent years, diverse groups seeking to advance the rights of LGBT people have grown and become important sources of information, services, and advocacy in China. These groups have made tremendous efforts to support equal rights for LGBT people in China, and to raise awareness about the difficulties they face.

These efforts have borne fruit: for example, the annual Shanghai Pride, a cultural festival, has taken place since 2009, and since 2008 the Beijing LGBT center has provided support services for LGBT people, advocated for equal rights, and organized creative public events, such as celebratory flash mobs on Valentine’s Day. PFLAG China, founded in Guangzhou in 2008, supports LGBT individuals and their families, friends, and supporters by hosting regional and national conferences in different cities. In 2007 the first Lala Camp took place in Zhuhai to encourage a network of lesbian, bisexual, and transgender organizations in China.[5]

However, the movement still faces considerable social and legal challenges. While violent and extreme hostility against LGBT persons is not common in China, the government has significantly limited activism on behalf of LGBT rights — part of deepening official hostility towards independent civil society.

This has limited the ability of LGBT groups to operate freely. LGBT organizations face similar difficulties to other NGOs when it comes to legal registration, and most opt to register as private companies, which is costly and fully taxable. Although some forms of public gatherings are permitted (including Shanghai Pride), government-imposed restrictions on LGBT groups are particularly clear with respect to freedoms of expression and assembly, as the following examples attest:

- In July 2017, a LGBT rights conference in Chengdu, Sichuan Province, was canceled after local state security bureau contacted and questioned organizers;

- In June 2017, under the direction of the Chinese government, the China Netcasting Service Association issued new guidelines that require all videos featuring same-sex relationship content to be removed from the internet, a vital forum for networking and communication for LGBT people;

- In May 2017, the Chinese government shut down the lesbian dating app “Rela” and a LGBT rights conference in Xi’an was forced to cancel after organizers and activists were arrested and detained;

- In 2016, the Chinese government ordered that China’s first online gay-themed TV series be removed from the internet;

- In 2015, official pressure forced activists in Beijing to cancel a pride festival;

- In March 2015, five feminists, outspoken in their support for the rights of LGBT people, were arrested and placed in a detention facility in western Beijing for organizing a public awareness campaign against sexual-harassment on public transportation;

- In May 2014, nine activists were detained in Beijing and told to cancel a planned seminar on legal registration of LGBT organizations.[6]

Activists have turned to the courts to combat discrimination, with modest success.

In July 2017, a transgender man won a labor discrimination case, considered the first such case of its kind in China.[7] In April 2016, Qiu Bai (a self-adopted pseudonym), a media major at Sun Yet-sen University in Guangzhou, brought a lawsuit against the Ministry of Education because school textbooks still include “homosexuality” in a list of mental disorders. Qiu challenged the ministry to revise the text books, and although her case was initially rejected by the court on grounds she had no “legal stakeholder” relationship with the Ministry of Education on this issue, she refiled in June 2016, arguing that “as a current university student, the plaintiff has a direct interest in the textbook materials”, and the case was accepted by the First Intermediate People’s Court of Beijing.[8] In April 2016, a Chinese court dismissed a case brought by two gay men seeking permission to be legally married.

Professor Li Yinhe, a well-known sociologist and longtime activist, who in 2000, 2005, 2008, and 2015 tried to introduce bills to the National People’s Congress of China that would amend the existing marriage law to include same-sex couples. Despite such efforts, no such bills have made it to the agenda of the legislature.

These cases, and the media attention they received, have raised the public profile of LGBT activism in China.

Pressure Leading to Conversion Therapy

There is a saying in Chinese "不孝有三,无后为大" — “Among the three major ways to be disrespectful to your parents and ancestors, the most severe one is not having offspring.”

This saying sums up social ideas about traditional family values in China, and the strong emphasis, on getting married, having children, perpetuating the family name, and supporting aging parents. Family units consisting of same-sex individuals are considered inimical to the goal of passing on the bloodline through biological offspring.[9]

China’s coercive “One Child Policy,” introduced in 1979, has exacerbated this situation. The policy increased social pressure for couples to have a biological, and ideally male, child to pass along the family name.

Because same-sex marriage is not legal, and there is no status given to civil partners, same-sex couples cannot enjoy the social benefits that heterosexual married couples enjoy, including adoption. In 2015, China amended its “One Child Policy,” but retained some family planning restrictions. The new law that became effective since January 1, 2016, is a “Two-Child Policy,” which limits every family to two children.[10]

In this societal and cultural context, some believe that being gay can and should be "cured.” While some clinics and hospitals offer conversion therapy in a discreet or secretive way, other practitioners publicly advertise their services.

Some attention has been paid to sexual orientation conversion therapy in Chinese academic research, contained in several published articles.[11] Articles published during the 1990s to 2010, refer to conversion therapy methods including medication, counseling, and electroshock, although detailed information on these methods is not provided.

In a 2014 survey of 800 participants conducted by the Beijing LGBT Center, over half the respondents had heard of conversion therapy, and almost 10 percent had considered receiving it. Over 75 percent of respondents had heard about conversion therapy via the internet, where many psychological clinics advertise.[12]

Doctors and psychiatrists justify conversion therapy for different reasons. Some explained to individuals whom Human Rights Watch interviewed that homosexuality could be due to social or family influence, and could therefore be changed. Others perceive homosexuality as immoral and unhealthy and used humiliating and degrading words against gay or lesbian individuals.

In 2014, the Beijing Haidian District Court sided with a young gay man who had undergone conversion therapy in a private clinic. The court ruled “since homosexuality is not a mental illness, the [defendant’s] promise that it could perform cures was false advertising.” Based on this ruling against the clinic for "false advertising" and "ineffective treatment," the court ordered the clinic to pay compensation for the treatment cost the man incurred and awarded him damages for physical and psychological suffering.[13]

In June 2016, another gay man from Zhumadian, Henan Province, brought a lawsuit against a public hospital for admitting him against his will and forcing him to undergo conversion therapy. In its narrow ruling issued in July 2017, the court found that the man’s rights had been violated when he was forcibly admitted.

However, neither case is likely to have a widespread deterrent effect or change the existing situation significantly, for three primary reasons: first, both rulings are narrow and neither addressed the issue of practicing conversion therapy itself; second, China’s courts’ rulings are considered as persuasive for future cases, instead of legally binding; and third, the damages awarded by the court are likely too low to deter other practitioners.

II. Abuses in Conversion Therapy

“My mom started… screaming about unfortunate things happening to our family, how she could ever survive it… My dad kneeled down in front of me, crying, begging me to go [to the conversion therapy]. My dad said he did not know how to continue living in this world and facing other family members if people found out I was gay. He was begging me to go so that he could live… I mean, at that point, what else could I do? I didn't really have any other options…”

— Xu Zhen (pseudonym), March 9, 2017.

“As [the doctors] turned [the machine] up, I started to feel pain instead of just numb. It felt like being pinched or having needles stabbing on my skin… Then after a few minutes, my body started trembling… It was not until later did I realize that was an electroshock machine.”

— Liu Xiaoyun (pseudonym), March 17, 2017.

Conversion therapy is intrinsically abusive and discriminatory and it violates China’s Mental Health Law, as discussed in section IV below. In addition, interviewees described specific forms of abuse in conversion therapy. The various forms of “treatment” they received did not reflect a consistent or uniform approach or practice. Nor were they based on sound medical or scientific knowledge.

In extreme cases, interviewees were physically forced into conversion therapy and held against their will. All interviewees said they were placed in conversion therapy programs under duress. They described intense coercion and even threats from family members and others. Human Rights Watch asked all interviewees whether they would choose to undergo conversion therapy or any other similar practice to try and change their sexual orientation. All 17 interviewees explicitly and affirmatively said they would not have undergone conversion therapy or any other attempt to change their sexual orientation but for parental, social, and cultural pressure.

Coercion and Lack of Informed Consent

All interviewees said they went to conversion therapy against their will, typically within days of coming out to their parents.

In three cases, individuals said their parents or other family members physically and forcibly took them to facilities. In other cases, individuals said they did not feel able to withstand the intense family pressure. In all cases, interviewees said that when they arrived at the hospitals or clinics, staff accepted them into “treatment” without their free and informed consent, and sometimes when they explicitly said they did not want treatment, or expressed strong reservations about receiving it. They said that when their families pressed them to undergo treatment against their will, practitioners invariably sided with their family.

Zhu Tianwen (who underwent conversion therapy in 2009, at age 15), who lived in a small town in northeast China, described what happened the night he was physically forced to go to a hospital in Heilongjiang:

My parents wanted to take me to some kind of treatment. I was just afraid they were sending me to some kind of electroshock therapy. My dad said there wouldn’t be anything like that involved, and that they just wanted me to be “cured” and be fine... I didn't want to go even after what my dad told me. So my aunts helped drag me out of my parents’ place into a minivan parked outside. They drove a couple hours and we finally arrived in Chongqing. The hospital in the city of Chongqing is the closest one to my home that offered conversion therapy… I was told to wait with my mom at the hospital when we arrived. My dad was taking care of the registration, after which the nurse said I could go put my stuff in my room and then go see the doctor.

Similarly, Zhang Ping, from Suzhou, a city in east China, told Human Rights Watch that his parents forcibly took him to a psychiatric hospital against his will:

The following day, my aunt and three other male friends of hers arrived at my parents’ house. Together with my parents, they asked me to pack my clothes and other stuff. I didn't want to go so I refused to pack… My mom and her friends took me to a car, in which they drove me to the city’s psychiatric hospital… I knew they were going to do that after I came out to my parents the day before. I knew it would happen.[14]

Li Zhi, who was taken to Psychiatric Division of the Nanping City Hospital (in Fujian Province, located in southeast coast of China), described how his parents took him to a hospital and made sure he did not try to escape:

They put me in the car and drove me to the hospital. When my mom was taking care of the registration and check-in, my dad was sitting right next to me. They decided one of them should stay with me to make sure I stay there until it was my turn to check in and see the doctor… When my mom walked out of the doctor’s office, she told me the doctor has agreed to enroll me into the ‘treatment’ program. I didn’t even get to see or talk to the doctor myself before they decided to accept me as a ‘patient.’[15]

Some described intense parental pressure that led them to feel they had no choice but to yield and submit to conversion therapy in hospitals or clinics. For example, Xu Zhen, who lives in Chengdu, a major city in southwest China, told HRW how she ended up receiving conversion therapy:

My mom started… screaming about unfortunate things happening to our family, how she could ever survive it… My dad kneeled down in front of me, crying, begging me to go [to the conversion therapy]. My dad said he did not know how to continue living in this world and facing other family members if people found out I was lesbian. He was begging me to go so that he could live… I mean, at that point, what else could I do? I didn't really have any other options…[16]

Li Qi, from Hubei Province, told Human Rights Watch:

My mom threatened to kill herself if I don’t at least go try those ‘treatment.’ My mom thought it would help change me. She thought I was just encountering some trouble and I could overcome it if I had professional help… My mom took me to the hospital, where doctor said she had confidence in ‘curing’ me and told my mom not to be too worried… Later, during a talk with the doctor, I told her I didn’t think this therapy would ‘cure’ me. I knew it wouldn’t work, and I really hated every minute of the ‘treatment.’[17]

Tian Xiangli, from Shijiazhuang, a city in north China, described a similar story:

My parents said I learned from someone ‘bad’ and became gay. They were very shocked when I came out to them. They insisted we kept it as a secret inside the family and that I should go to see a doctor for treatment. They both looked very serious that night, when we were sitting in the living room in their house. My mom was crying. My dad was not, but he looked very frustrated, and even mad at me… I was 22 and I was at college. They asked me not to go back to campus. Instead, they accompanied me to the hospital for some evaluation, after which I was registered to the psychiatric department.[18]

Zhang Zhikun, who was living in Shenzhen, Guangdong Province, told Human Rights Watch:

After I told my parents that I am gay, they pressured me a lot and tried to persuade me to receive treatment. My parents kept pushing me to the point that I had to break up with my boyfriend. My parents also tried multiple times to set me up with girls and wanted me to get married… I saw that type of advertising [of conversion therapy] before. There wasn't really much I could do to change my parents' mind. I knew it was not going to work if I kept resisting their pressure. I thought I would give it a try… in some way, just to let my parents know I cannot be changed in that sense.[19]

The line between forced physical abduction and family coercion can feel like a thin one for individuals who are either forced or feel compelled to undergo conversion therapy. In all cases that Human Rights Watch documented, individuals were subject to conversion therapy “treatment” without free and informed consent. The combination of intense family pressure, which in some cases includes physical force, and practitioners who impose treatment without ensuring informed, voluntary consent means that individuals have little option but to receive “treatment” that they do not want and that can be psychologically damaging.

Interviewees told Human Rights Watch that doctors or psychiatrists usually started “treatment” with an introductory, informational session in which they asked “diagnostic” questions. Interviewees described voicing to doctors their unwillingness or even anger about being forced to undergo the “treatment”. In some cases, interviewees said they expressed their deep skepticism that the “treatment” would change their sexual orientation. But despite these protests and questions, none of the hospitals or doctors refused to admit the “patient.”Hospitals appeared to have admitted these individuals as “patients” based solely on their parents' requests and did not obtain affirmative consent from individuals.

Arbitrary Deprivation of Liberty

Of the 17 cases that Human Rights Watch documented, five people were confined against their will at psychiatric hospitals or in the mental illness division of a hospital. These interviewees described limited access to privacy, space, and communications.

Zhang Ping, from Jiangsu Province, told Human Rights Watch:

The night they took me to the psychiatric hospital, my parents asked me to go to bed early and rest well. The nurse walked me to a room on the same level of the building. Afraid of patients attempting to escape the hospital, the staff at the hospital usually locked the rooms from the outside… When I said I had to use the restroom, the nurse who was working that shift would come in to my room and escort me to the restroom, and the nurse would be guarding at the door to the restroom.[20]

Luo Qing, from Shanxi Province, had tried to keep his cellphone to retain contact with friends.

At the beginning, I managed to hide my cellphone and take it with me into the hospital. I hid it under the mattress. I was texting my friends or messaging them on QQ [a popular instant messaging application], telling them what happened to me and what was going on here in the evenings, when I was in my room and no one was watching me… Later, the staff at the hospital found out about my cellphone while inspecting patients' rooms, and they confiscated it. I was out of touch with my friends for the rest of my time [about three weeks] in there.[21]

Tian Xiangli, who was confined in a psychiatric hospital for conversion therapy, described feeling uncomfortable in the room he shared with two others, and frightened by the unpredictable behavior of a patient. He told Human Rights Watch:

“One was a very young boy, and he had some kind of compulsive disorder and he was washing his hands constantly all the time… The other guy had illusions. He would start screaming or running around all of a sudden… I was just so scared that he might become violent and hurt me, especially when I was asleep during the night.”[22]

Three interviewees told Human Rights Watch that they attempted to escape from the facility. One of them, Zhang Ping, from Jiangsu Province, succeeded:

There was one evening, for whatever reason, my door was not locked. I walked very quietly to the yard, I looked around and I didn’t see anyone guarding the yard. I then walked very carefully toward the wall of the yard. It was so quiet and I could hear my own breaths. My heart was beating so fast when I was walking toward the wall of the yard… I climbed over the wall. And then I started running like crazy, I was really trying to run as fast as I can… I could hear wild dogs barking while I was running. It was really dark, and it was freezing.[23]

The other two interviewees' attempts to escape failed. For example, Luo Qing, who was confined in a hospital in Shanxi Province, said:

I remembered that was one day, at lunch time, I was standing in the line waiting to get food, like everyone else. I noticed that the door connecting outside from the dining hall was somehow not guarded by anyone that day. But there were other two guards standing not too far from the door. I assumed they were security guards, not sure… I decided to try it. I left the lunch plate there, and started running toward the door. I was getting really close to the unguarded door, but before I could get to the door, the two security guys caught up and got me. The next thing I know is that I was on the floor.[24]

The ordeal was not over for those who succeeded or attempted to escape; two described being taken to the hospital for "treatment" more than once. For example, Zhu Tianwen, was twice taken to the same facility, against his will.

I was taken home for a week after the first month’s treatment. After resting for a few days at home, they took me back the same hospital… The same people, the same minivan. I remembered that minivan from the first time.[25]

Zhang Ping, who escaped from the psychiatric hospital, told Human Rights Watch:

Almost two weeks after I escaped from that hospital, I ran out of money and I had nowhere to go. I was hiding at a friend's place but her mother was no longer okay with me staying there. So I had to leave… I had to go back to my parents’ house. That’s when they sent me back to the same hospital.[26]

Eventually, all these individuals were released, either because the family could no longer afford the expenses, or because the doctors at the psychiatric hospitals gave up for complete lack of “intended effect” of conversion therapy, as one interviewee detailed:

The doctor ended up calling my parents telling them that this [conversion therapy] is probably not going to work. The doctor also said my situation [being gay] was probably not a big deal and they should take me home.[27]

China's 2013 Mental Health Law prohibits forced enrollment of an individual unless there is clear evidence that this individual is likely to pose a danger to himself or others. The detention in hospitals described by interviewees above was arbitrary.

Verbal Harassment and Intimidation

Almost all of the individuals interviewed by Human Rights Watch reported being subjected to verbal harassment and insulting language by doctors and psychiatrists, including terms such as “sick,” “pervert,” “diseased,” “abnormal,” “dirty,” and “slutty.”

Tian Xiangli, from Hebei Province in north China, told Human Rights Watch:

I sat down, and the doctor gave me a form and asked me to fill it out… The doctor started saying to me: ‘You are sick. You know that yourself, right? I am not lying to you. If you feel like having sex with another man you are sick. But don't worry about it too much now, I can help you with that. This is why your parents brought you here.[28]

Another interviewee, Zhang Zhikun, described a similar discussion with a doctor:

This is pretty much what that doctor told me: ‘This [homosexuality] is promiscuous and licentious. If you don’t change that about yourself, you will get sick and you will die from AIDS. You will never have a happy family ... Have you ever considered your parents’ happiness?[29]

Long Bingzhi, who had undergone “therapy” in a public hospital in Beijing, said:

The doctor asked me about my situation, like what I told my parents and why my parents brought me there. I told him everything about my coming out, about my boyfriend, things like that… Then he started talking, telling me being gay is wrong and gross: ‘You homosexual people are just perverts. It’s disgusting and abnormal. How could you do that to your parents? Aren’t you ashamed of yourself?’[30]

Even those who were treated with less hostility were told by doctors or psychiatrists that being gay was “a problem." According to Li Zhenhui:

The doctor asked me a set of questions, trying to evaluate my mental status. She had a list of questions and a form on her desk, which she was filling in as I was answering those questions… When she finished that list of questions, she said to me: ‘It’s ok. I think we know what the problem is with you now. You are just having some issues with your psychological status in terms of your sexual attractions. Things like this happen. We can cure you if you follow the instructions. We have patients like you before. And we have done it before.’[31]

Similarly, Wen Qi said:

The doctor at the hospital we visited is a very famous one in the city where I am from. He appeared on all kinds of advertisement for mental illness treatment. We saw him quite often on TV or on newspaper. The psychiatrist told my mom: ‘Homosexuality is just like all the other mental diseases, like depression, anxiety, or bipolar. It can be cured. I have confidence in your son’s case. Trust me, leave him here, he is in good hands.’[32]

Gong Lei, told Human Rights Watch that although he disagreed with the doctor, he felt there was little he could do:

When the doctor told me being a gay is a disease, I was very angry. I so much wanted to disagree with the doctor… my mom was sitting right next to me. And she [my mom] was very mad and upset with me already. I couldn’t really say anything back to argue. I know that I am not sick, I am fine. I just couldn’t say it. They get mad at you.[33]

Seven interviewees told Human Rights Watch that they remained comfortable with their sexual orientation, despite the humiliating characterizations of their sexuality. Zhang Zhikun said:

The doctor was talking non-stop. The so-called psychological evaluation conversation lasted for hours and I was losing my patience. At some point, I stopped listening to him. I just [felt that] what the doctor was saying to me was nonsense. I knew there was nothing wrong about being gay.[34]

Zhang Ping, who was taken to psychiatric hospital twice for conversion therapy by his parents and relatives, said:

When I was staying in the hospital, I was asked to have conversations with the doctor every week, probably two or three times a week. The doctor would tell me why being gay is wrong and how she could change that for me, all that crap. I always said ‘yes’ to everything she said. I knew it was not going to work if I argued with her. So I just let her talk. I don’t care what she said and I knew there was nothing wrong with me (being gay). I just wanted to get out of there.[35]

Derogatory terms used by health professionals are not only insulting, they also reflect an unwillingness to acknowledge that homosexuality is not a crime or a mental illness.

|

Interviews with Parents Human Rights Watch interviewed the mother of one interviewee, Li Qi. Li Qi identifies as female now, which is not known to her mother. Her mother still refers to her by male pronouns. At the time of her conversion therapy, she identified as a gay man and was treated as such.” She reflected on forcing Li Qi, then 19 years old, to attend “conversion therapy” sessions in 2014, and how she later changed her mind: I accidentally found out that my son was chatting in a gay WeChat group. My entire world collapsed. I was crying all day long, I was not brave enough to confront with him on it. I hid it well for a few days, but I was crying in my room every night… Then I decided to tell him that I found out he was gay and tell how difficult it was for me. I was separate from his dad back then, but we decided to meet to discuss how to deal with the situation… Eventually, his dad and I together decided that we should take him to the hospital where they provided conversion therapy… We took him there together for the first time, to register him into the hospital for the ‘treatment.’ After that, I took him [Li Qi] there myself every time. He was very unhappy about it, but he was at least obedient about it … I took him to the hospital for electroshock session for once. Just once. Then I told myself I would never do that again… I later started reading more books and articles about electroshock treatment. I realized how much harm it could cause to the kids by using electroshock. I shouldn’t have done it… I wouldn’t have done it if I knew back then. I knew nothing about homosexuality back then.[36] Human Rights Watch also interviewed a father, who took his gay son (age 19) to a hospital for electroshock treatment. The father, Li Waichen, said: He was very resistant about the idea of going to the therapy. I had no other choices. I can’t let other people in the family know that my son is gay. So I took him there with his mom, and we decided to leave him there for the treatment… I asked the doctor to save my son, I was begging him to cure him… They asked me if I would consent to the use of electroshock. I was worried that the electric current could cause some harm to my son, I mean I wasn’t sure, I knew nothing about this type of treatment, I knew nothing about homosexuality back then… But I did agree to the use of medicine. My idea was that the medicine would probably be easier on him… I agreed to the use of medicine and signed the document to authorize the doctors and nurses to do their job.[37] |

Forced Use of Medicine

Forced psychiatric intervention, including forced drugging, can constitute torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment, and has been condemned by related United Nations human rights special procedures.[38]

Nonetheless, 11 interviewees told Human Rights Watch that they were required, or in some cases, forced, to take pills, and subjected to injections or other forms of medicine as part of their "therapy" or "treatment." They said that they did not know what medications they were given as the doctors prescribed them without explaining their purpose or potential risks. Medical personnel ensured that individuals took the medications even when they resisted, or expressed a preference not to do so. In some cases, where the individuals were not confined in hospitals, parents of these individuals administered the medications.

Li Zhi, from Nanping City, still has no idea what pills he took, or what they were supposed to do:

They were white pills in a bottle. I didn't know what they were. I mean, I still don’t know what they are. The doctor and the nurse refused to tell me what the pills were. They just told me they were supposed to be good for me and help with the progress of the 'treatment'… After I took them, I usually feel hyper-energized for a while, like a few hours. Then after a few hours, I started to feel very exhausted and depressed.[39]

Even those confined at home had parents enforce the taking of unknown medications, as Xu Zhen described:

They gave me a bottle of white pills, in a blue bottle. Like a standard blue bottle for medicine. There were no labels or any instructions on the bottle. The doctor instructed my parents to make sure I took four of them every day… When I was locked at home in my room in the following weeks, my mom would bring those pills and water to me, usually, after dinner. I had to take them in front of her. Otherwise my mom won’t let it go.[40]

Some interviewees were told that they were being given medication to treat specific conditions, although they had not been given a diagnosis nor the opportunity to discuss it. Wen Qi said doctors treated him for anxiety, even though he did not consider himself to be anxious:

The nurse would give me a couple pills every day. The doctor said those pills were for depression and bipolar symptoms. The doctor also said some of them would have sedative effects, which would help with my anxiety and calm me down… I was confused and angry. Because I just don’t think they know what they are doing. I don’t have anxiety issues. Why would they give me pills for anxiety or bipolar disorder?[41]

Some interviewees told Human Rights Watch that they went to some lengths to avoid taking the medicine, such as pretending to swallow it, before spitting it out and discarding it. Zhang Zhikun, who was forcibly confined in the psychiatric division of a hospital, said:

Every morning, the nurse brought a couple of capsules and water to me. I was required to take the medicine in front of her. Then the nurse would ask me to open my mouth and checked if I had actually swallowed the capsules. I usually hid the capsules and pills under my tongue… When the nurse was gone, I went to the toilet to spit them out and flush them away … sometimes the nurse stayed for too long and the capsule started to melt in my mouth. It felt gross, because I really didn’t want those medicines in my body.[42]

Other interviewees told Human Rights Watch that their parents or the nurses at the facilities were strict when examining "patients" to determine whether they had taken their medicine. For example, Chen Shuolei, who was also forcibly confined in a hospital for conversion therapy and was forced to take medicine daily, said:

The nurses at the hospital had an awful attitude with the patients there. I was asked to take a red and yellow capsule and two white pills every morning. I tried to pretend I swallowed them. I was hoping get them out later. But the nurses always asked me to open my mouth and lift my tongue, and then she would use a stick to check around to make sure I actually swallowed them… A stick like they use for examination at the dentists… I wouldn't be able to hide the pills or capsules anywhere in my mouth.[43]

Zhang Zhikun, from Guangdong Province, had already endured electroshock treatment and been forced to take oral medicine when he was subject to injections as part of his “treatment”. A nurse injected nausea-inducing medication while he was watching gay pornography, so that he would associate sexual arousal with nausea:

I told them I couldn’t put with electroshock anymore… [so] the hospital recommended medicine by injection... The doctor said it would be more ‘gentle’ than electroshock, and maybe less side effects… They asked me to watch and concentrate on the gay porn playing on the screen. And a nurse injected some liquid into me with a syringe… The liquid has no color and it was usually injected in my arm… Soon my body started to feel like it’s burning. My stomach was very uncomfortable, I felt very disgusted and constantly wanted to vomit in the whole process, but I didn’t really vomit. I was having a headache too… Every few minutes, the doctor and the nurse asked me to calm down and keep focusing on what is being shown on the screen.[44]

Cheng Zhiwen, from Henan Province in north China, explained how he was restrained and forced to take medicine:

I was tied up to a bed with ropes because I refused to take any medicine they gave me. So they tied me up and forcibly fed those pills to me.[45]

Prescribing medicines requires a license, strict regulation, and monitoring under Chinese law. In the cases that Human Rights Watch documented, doctors and psychiatrists did not give any explanation or rationale for the medicines they prescribed. This is indicative of the current lack of governmental or professional regulations related to psychiatry in China.

Electroshock

Five people told Human Rights Watch about undergoing electroshock “therapy.” In all these cases, the interviewees were receiving outpatient “treatment.” They described being given some sort of stimulus — typically images, videos, or verbal descriptions of homosexual acts — while simultaneously being subjected to pain or discomfort produced by electroshocks. This conditioning is intended to cause the patients to associate their homosexuality with unpleasant or painful sensations so as to quell the targeted behavior: sexual attraction toward people of the same sex.

Five individuals, including Zhang Zhikun, endured electroshock "treatment" as part of their conversion therapy. Only one of the four was informed in advance that he would be subject to such treatment. He explained:

I was very scared, because I have never heard of it before… you tend to trust the doctors. At least they would not do something harmful to you, right? … I was asked to sit down on a chair, with my hands both tied on the chair arms with leather strips. Then the nurse and the doctor attached pads to both of my wrists and my stomach and my temples. These pads are connected to a machine through cables… The nurse also set up a screen in front of me, where they later started playing gay porn on the screen. The doctor asked me to watch the what was playing on screen and asked me to focus on what was content of the video… A few minutes later, they switched on the electric current. My wrists and arms felt numb, my head too. But the most painful part was my stomach. I don’t know why, probably they used stronger electric current on the part attached to my stomach… They repeated the electroshock for about six or seven times during the entire session… I had to go through about four electroshock sessions every month… I had nine sessions in total, I think.[46]

The other four interviewees said they were unaware that they would be subjected to electroshock, and described their fear and frustration to Human Rights Watch. For example, Liu Xiaoyun, said:

One part of that machine looked like a helmet, it was connected to the main part with cable. The interior of the helmet is covered with many dots, they look like metal dots… when they put the helmet on my head and turned on the machine, my head started to feel weird. It was like your skin on your head was being bitten by many bugs at the same time. As they turned it up, I started to feel pain instead of just numbness. It felt like being pinched or having needles stabbing on my skin. Then after a few minutes, my body started trembling… It was not until later did I realize that was an electroshock machine.[47]

Gong Lei, who underwent conversion therapy in Fujian Province, told Human Rights Watch:

I didn’t know they would actually use electroshock… I was asked to relax and the doctor said he was performing some kind of hypnotizing procedures to help me get into the status ready for treatment… The doctor asked me to think about sex with my boyfriend. And I felt pain on both of my wrists. I got freaked out and had no idea what happen… The doctor said it was electroshock. And it will take more sessions to make it work.[48]

Li Zhen, who was sent to a private psychiatric clinic in Chongqing, a major city in southwest China, said:

The doctor asked me to lie down and relax. He started to play very gentle and slow music, at a very low volume. He asked me to think about my intimate moments with my boyfriend. He asked me to relax and start imagining having sex with my boyfriend… then all of a sudden, I felt a very short but strong pain on my left forearm, as if my arm was stabbed by something very sharp. I jumped off the couch I was lying on and started yelling at the doctor and asked him what the hell that was. He told me it was electroshock treatment… I don’t feel the pain anymore. But I remembered I was so scared and did not know what could have happened to me. I don’t want it to continue doing that. I asked him to stop the session. The psychiatrist said that would be it for that session, but I would need to be ready for more sessions of electroshock for this to work.[49]

Xu Zhen, from Sichuan Province, also described his surprise at the use of electroshock treatment:

I was asked to lie down on a bed. They covered my eyes and asked me to relax and think about my experience having sex with my same-sex partner. My legs were tied onto the bed, with some metal pads underneath. They tied my hands on to the bed too…. When they switched on the power, I can feel the electric current coming in from my legs, only my legs… I thought it was going to be a very brief shock, but it turned out they left it on for a while. It felt like a long time… I have no idea exactly for how long, but I started shaking on the bed, I felt the metal pads were getting burning hot. I asked them to turn it off. I don’t think they could hear me.[50]

Two interviewees who endured electroshock treatment reported not being able to continue their daily work and life normally. Zhang Zhikun said:

After three or four sessions of the electroshock treatment, I started to feel sick regularly and I started having a difficult time concentrating at work. Two months later, I lost my job because of that. I just couldn’t concentrate to get anything done.[51]

Liu Xiaoyun, from Xiamen, a city in southeast China, described a similar outcome:

I felt exhausted for a couple of days every time I finished a full session of electroshock treatment… I can’t focus on school work. I kept falling asleep in classes. I just felt tired all the time.[52]

Human Rights Watch also interviewed a friend of a person who went through electroshock. Pu Tian, from Fujian Province, told us that his friend, Sensen, was taken to conversion therapy by his parents. Pu Tian shared what he knew about his friend’s story:

He was a very dear friend of mine. We are both gay. I know he is, he knows I am too. At some point, he started to look really tired and he would fall asleep at school. I asked him what happened. He told me his parents started taking him to conversion therapy sessions… He told me he had to go to an electroshock session once a week, and he is required to take some pills. I asked him what he was told to take. I said he was not supposed to take those pills when he didn’t know what they were. He told me he didn’t know. He only knew that he felt very tired after taking those pills… A few months later, I stopped seeing him in school. I called him, texted him, and messaged him on QQ, but no response. I was told that he dropped out of school and was sent to a psychiatric hospital… I still couldn’t get in touch with him. I haven’t seen him since.[53]

During the interview, Pu Tian also told Human Rights Watch that she suspected Sensen attempted suicide after Sensen came out to his family and was taken to receive so-called treatment:

A few weeks after Sensen’s ‘therapy’ started, one day he came to school and I saw cuts on both of his wrists… The cuts are short and very narrow, but there are many of them. I am pretty sure he [Sensen] was trying to hurt himself.[54]

III. Lack of Regulations and Accountability

“We are not aware of these incidents. None of the cities has reported to the bureau. There is no way for us to know or do anything if the cities have not reported anything. And it is impossible for the bureau to investigate and examine every hospital across the entire country.”

— Bureau of Discipline, Inspection, and Supervision Agent, June 2017

Licensing and qualification

Under Chinese law, all hospitals or other facilities that provide psychiatric and psychological services need to obtain authorization from the National Health and Family Planning. The Department of Personnel, under the National Health and Family Planning Commission,[55] is in charge of setting medical professional qualification standards and administering the licensing of medical and psychiatric practice.[56]

All medical practitioners need to obtain necessary educational qualifications and succeed in the National Medical Licensing Examination and National Medical Qualification Examination before they are eligible to apply for a license to practice in China.[57] The National Health and Family Planning Commission is also mandated to keep a record of all licensed hospitals[58] and licensed doctors in the country.[59]

Part of the problem with professional regulation of mental health services in China is that it has been remarkably easy to obtain certification as a mental health counsellor. In September 2017, the Chinese government stopped certifying mental health counsellors because the process was neither rigorous nor up to professional standards. This is a small but important step towards professionalizing the mental health industry.[60]

It has been reported that the termination will not retroactively apply to the Mental Health Counselor Certificates obtained prior to September 15, 2017. The Certificates obtained previously will remain valid. At the time of writing it remained unclear how the Chinese government intends to address the certification process of mental health counselors in future.

A lack of regulation and professionalization of mental health counseling practice in China is only part of the problem — as the cases documented in this report demonstrate, conversion therapy is practiced in both public health facilities and government-certified private clinics.

Regulations and guidelines

In 2001, the Chinese Society of Psychiatry (CSP), a member of the World Psychiatry Association (WPA), conformed to WPA’s standards by officially removing “homosexuality” from the Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders.[61]

However, a review by Human Rights Watch of publicly available regulations and guidelines on medical care issues by the National People’s Congress and the National Health and Family Planning Commission suggest that none include provisions regarding conversion therapy.

Likewise, Human Rights Watch has not been able to find any statement or guidelines from the CSP other than its 2001 decision that reflects the changed position on homosexuality, or any steps taken in response to the 2014 (Beijing) and 2016 (Henan Province) court cases litigating against the practice of conversion therapy. The Chinese Psychological Society (different from CSP) published professional ethics guideline that prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation, but there are no cases in which a mental health professional was disciplined for conducting conversion therapy.[62]

Against the backdrop in which there are no laws or regulations to protect individuals from discrimination due to sexual orientation, in which there are no proscribed professional guidelines on relevant psychiatric practice, in which families are willing to pay large sums to “cure” an individual from homosexuality, an abusive practice has persisted.

The individuals interviewed by Human Rights Watch did not receive conversion therapy in clandestine facilities, or from unlicensed providers. 14 out of 17 individuals interviewed underwent their conversion therapy “treatment” in public hospitals, and the other three in private clinics that offer psychiatric services. Each interviewee said they were “treated” by staff of healthcare facilities who presumably were all appropriately licensed by a relevant governmental agency.

Li Zhen, who underwent conversion therapy in a private clinic in Chongqing, said:

He [the psychiatrist] told me he was authorized to provide psychiatric and psychological service. He then showed me his certificate to practice, which was on the wall in this office.[63]

Li Zhenhui, from a city on the east coast of China, described what she saw during his visit at the clinic that provided conversion therapy:

There are some posters on the wall. One of them shows the price of a list of different packages of treatment. Rights next to it were his diploma from medical school and his certificate to practice.

Inadequate Accountability Mechanisms

Article 26 of the PRC Mental Health Law requires that the diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders respect individuals’ basic rights and human dignity.[64] The law also requires that the diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders comply with diagnostic standards and standards on the categorizations of mental disorders.[65]

Under the National Health and Family Planning Commission, the Bureau of Discipline, Inspection, and Supervision is tasked with monitoring the implementation of health-related laws and regulations.[66]

Among all the regulations and guidelines issued by the Bureau of Discipline, Inspection, and Supervision, there is only one relevant to mental health, the "Notice on the Implementation of Mental Health Law," which was published in 2015.[67] The notice requires all levels of government to conduct investigations into illegal activities occurring in hospitals and clinics that constitute violation of the 2013 Mental Health Law. It further requires all levels of government to self-report any illegal practice in the field of mental health. On the official web page of the Notice, there are two forms for self-reporting available for download (see Appendix III).

Among the resources and documents made available to the public, Human Rights Watch was not able to identify any evidence of complaints or petitions submitted by government officials in any regions where conversion therapy was practiced. Based on the interviews that Human Rights Watch conducted, none of the interviewees had chosen to file a complaint under this mechanism. Twelve of the interviewees told Human Rights Watch that they chose not to file any official complaint because they were too afraid that their sexual orientation would be made public. And five of them told Human Rights Watch that they were not aware of the existence of the bureau or the reporting mechanism.

In June 2017, Human Rights Watch contacted the hotline provided on the website of the Bureau of Discipline Inspection and Supervision to ask for further details about the implementation of the notice. Human Rights Watch asked questions on the reported cases of physical abduction, forced use of medicine, electroshock treatment, and other abuses. Human Rights Watch inquired about knowledge of these cases and the practice of conversion therapy in public hospitals. Human Rights Watch also asked if the bureau had taken any measures particular to the practice of conversion therapy. The agent responded:

We are not aware of these incidents. None of the cities has reported to the bureau. There is no way for us to know or do anything if the cities have not reported anything. And it is impossible for the bureau to investigate and examine every hospital across the entire country.

Human Rights Watch also sent letters to the National Health and Family Planning Commission to inquire about their policy or position concerning the currently existing practice of conversion therapy (see Appendix II), but had received no response or explanation at time of writing.

The Chinese Psychological Society (CSP) has a code of ethics for its members, but it only has about 1,000 registered members, representing a small minority of mental health practitioners in China.[68] However, it appears that no professional has been disciplined or investigated for practicing conversion therapy based on documents and information made available to the public.

The Chinese Society of Psychiatry (CSP) does not appear to have any sort of monitoring or disciplinary organs across the profession.[69] Human Rights Watch was not able to identify any methods to report or file a complaint about illegal or unethical conduct of psychiatric professionals. Human Rights Watch also sent a letter of inquiry with questions to the Chinese Society of Psychiatry (See Appendix II) but had not received a response at time of writing.

Court Verdicts Lacking Deterrent Effects

Only two cases have been taken to court regarding the practice of conversion therapy. The first was filed in the Beijing Haidian District Court, which rendered a decision in December 2014. The second was filed in Zhumadian, Henan Province, in June 2016, and the court rendered a decision in July 2017.

The 2014 lawsuit was brought against the Xinyupiaoxiang Clinic by a gay man who received conversion therapy and argued that attempting to treat homosexuality violated his rights. The court ruled in his favor, reiterated that homosexuality is not a mental illness or disorder, and awarded the plaintiff compensation because the clinic committed “false advertising” after charging him for the service. It also awarded him damages for physical and psychological suffering. The court also ordered the clinic to issue official apologies to the plaintiff and to suspend any form of conversion therapy. This decision was the first legal opinion related to conversion therapy issued by Chinese courts.

The 2014 decision has done little to deter the practice of conversion therapy. Xinyupiaoxiang Clinic reopened within a few months with the same name, at the same location, and run by the same psychiatrist, Jiang Kaicheng.[70] As of July 2017, the clinic’s official website shows that it is still open.[71] While conversion therapy is not explicitly listed as one of its psychiatric services or treatments, a clinic staff member explained in a June 2017 call with Human Rights Watch:

Conversion therapy is still available. It is not on the list now, but yes, you can still get it. But you need to come to my office to talk about it, okay? Please come in to the clinic for more information, if you are interested.

A second case was brought against a city mental hospital in Zhumadian, Henan Province in 2016, by Yu, a gay man whowas forcibly admitted to the city’s mental hospital by his wife and relatives in 2015. There he was diagnosed with “sexual preference disorder” and forced to take medications and receive injections. In 2016, he filed a lawsuit against the hospital, and in July 2017, the court rendered a decision favoring the plaintiff, Yu. The decision ordered the hospital to issue a public apology to Yu in local newspapers and pay him compensation. In its narrow ruling, the court held that the forced admission of Yu into a mental institute constituted infringement on the plaintiff’s right to individual freedom. Clearly, as the court found, the mental hospital’s diagnosis and the “treatment” it forced upon Yu were inconsistent with related laws and regulations. However, the court did not directly address the practice of conversion therapy itself or its underlying erroneous premise that homosexuality is a mental disorder.

IV. Legal Framework

Decriminalization of Homosexuality, 1997

Any ambiguity about the legal status of consensual male same-sex activity was removed under the 1997 revision of the Criminal Law of the People Republic of China. Prior to that, the offence of “hooliganism” had been interpreted by the National Supreme People’s Court to include anal sex. Since 1997 consensual, non-commercial same sex activity between men has been legal in China. Sex between women has never been criminalized. The age of consent in China is 14 years, regardless of gender or sexual orientation.[72] Under Chinese domestic law, citizens have the freedom to engage in same-sex behavior without unreasonable intervention.

Mental Health Law of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), 2013

In 2001, the Chinese Society of Psychiatry revised its Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders (CCMD) and took homosexuality off the list of mental illnesses or mental disorders.[73]

In May 2013, China’s first mental health law came into effect. Article 26 of the PRC Mental Health Law requires that the diagnosis and treatment of mental disorder respect individuals’ basic rights and human dignity.[74] The law also requires that the diagnosis and treatment of mental disorder comply with diagnostic standards and standards on the categorizations of mental disorder.[75]

Conversion therapy, whether offered by state-run hospitals or private practitioners, is inconsistent with the national standards set out by the Chinese Society of Psychiatry, because homosexuality, under both national and international standards, is not a mental disorder and homosexual individuals should not be treated as if they were mentally ill.

Article 27 of the PRC Mental Health Law also prohibits the diagnosis of a mental disorder or any medical procedure performed against an individual’s will.[76] The admission of “patients” and the subsequent “diagnosis” of homosexuality in forced conversion therapy cases, particularly in those instances where individuals were physically forced into treatment, clearly violate the Mental Health Law.

Article 30 of the PRC Mental Health Law asserts the principle of voluntariness and prohibits confinement of patients for mental disorder unless the individual has harmed himself/herself or others, or has well-founded tendency to harm himself/herself or others.[77] Confining gay and lesbian individuals in state-run psychiatric hospitals against their will is not only inconsistent with the declassification of homosexuality as a mental disorder, but also violates article 30 of the Mental Health Law and the principle of voluntariness.

Article 41 of the PRC Mental Health Law addresses the use of medicine in the context of mental illness and disorder and prohibits the use of medicine for purposes beyond the legitimate scope of psychiatric diagnosis and treatment.[78] In the cases documented by Human Rights Watch, the use of medicine is commonly reported. The use of medicine is not justified under the related medical practice standards because homosexuality is not considered to be a mental disorder or illness. In this context, the use of medicine, regardless of its actual medical effect, is a violation of the law.

Article 78 of the PRC Mental Health Law requires accountability and reasonable compensation for conduct that violates the relevant provision of the law, including admitting or treating non-mentally ill individuals as mentally ill patients, illegally confining individuals against their will, and discriminating against or humiliating patients.[79]

Concerning the practice of conversion therapy documented in this report, other than two specific court cases mentioned in this report, there has been no accountability. The Chinese government or relevant agencies have not yet addressed any such cases. Nor has any remedy, legal or otherwise, been offered to people subject to conversion therapy. The majority of cases documented by Human Rights Watch occurred in state-owned public hospitals. This reflects a serious lack of regulation, oversight or implementation of the law.

Right to Freedom from Non-Consensual Medical Treatment Under International Law

The PRC signed the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) in 1997 and ratified it in 2001.[80] Under Article 12 of the ICESCR, states parties are legally obligated to offer medical service that is consistent with the highest attainable standard.[81] The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has interpreted art. 12 to include the right to control one’s own body and to be “free from interference, such as the right to be free from torture, non-consensual medical treatment and experimentation.”[82]

The Committee, in its General Comment No. 14, further states that the right to the highest attainable standard of health requires that states parties guarantee the acceptability and quality of the health care: “All health facilities, goods and services must be respectful of medical ethics and culturally appropriate” and “health facilities, goods and services must also be scientifically and medically appropriate and of good quality.”[83]

In all of cases documented in this report, individuals were subject to conversion therapy without informed consent. In some cases, individuals were physically forced to go to institutions where they were admitted for treatment. In others, they were given no choice but to undertake the treatment. Some were held in involuntary confinement in the process of providing “treatment.” These amount to coercive measures.

Moreover, there was no exceptional basis to justify any of the coercive measures because homosexuality is not a mental illness. As indicated in the global consensus among psychological and psychiatric professionals, conversion therapy purported to change individuals’ sexual orientation is ineffectual, unethical, and potentially harmful.[84] The practice of conversion therapy is inconsistent with the right to the highest attainable standard of health.

Right to Freedom from Torture or Ill-Treatment

The People’s Republic of China signed the Convention Against Torture, and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment in 1986 and ratified it in 1988.[85] Under the convention, all state parties are obligated to take all necessary measures to prevent torture and cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment in any territories under its jurisdiction.[86]

In 2016, the UN Committee Against Torture specifically stated with reference to the practice of conversion therapy in China that the committee was concerned that “private and publicly run clinics offer the so-called ‘gay conversion therapy’ to change the sexual orientation of lesbian and gay persons, and that such practices include the administration of electroshocks and, sometimes, involuntary confinement in psychiatric and other facilities, which could result in physical and psychological harm.”[87] Citing articles 10, 12, 14 and 16 of the convention, the committee noted its regret that China failed to clarify whether such practices were prohibited by law, or if they had been investigated and ended, and whether the victims had received redress.”[88]

|

Exchanges during the 56th Review Session of the CAT (2015) During the 56th Review Session of the Convention Against Torture in 2015, the following exchanges occurred, which includes public statements by Chinese public officials at the UN that are inconsistent with its practice: “Ms. Felice Gaer (Vice-Chairperson of the Committee): My final question deals with question 38b, which asks for more information on the practice of clinics offering gay conversion therapy. We have been told that these clinics exist in facilities across the country, run by the government as well as private ones, that there are 14 in Beijing alone, that they administer electroshocks to LGBT patients, and in some cases these people are detained at psychiatric facilities. A Beijing district court did provide compensation to one person who was subjected to such therapy. Can you describe to me whether the practices I have described are… [inaudible because of microphone problem ...]. Have there been any actions by the government to investigate these practices, put an end to them… [inaudible because of microphone problem] since the 2014 court ruling? Yang Jian from the Ministry of Justice: As to the issue of LGBTI, mentioned by Madam Gaer and Madam Mallah. China does not view LGBTI as a mental disease or require compulsory treatment for LGBTI people. They will not be confined in mental hospitals either. Indeed, LGBTI people face some real challenges in terms of social acceptance, employment, education, health, and family life. This deserves our attention, but this does not fall within the scope of the Convention.”[89] |

Furthermore, the Human Rights Council echoed this position in 2016 by condemning the medical practice of so-called “conversion therapy” as a form of torture or ill-treatment on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity.[90]

The use of electroshocks reported by the interviewees in some cases may amount to acts of torture, or inhuman or degrading treatment.

Right to Freedom from Arbitrary Deprivation of Liberty