Summary

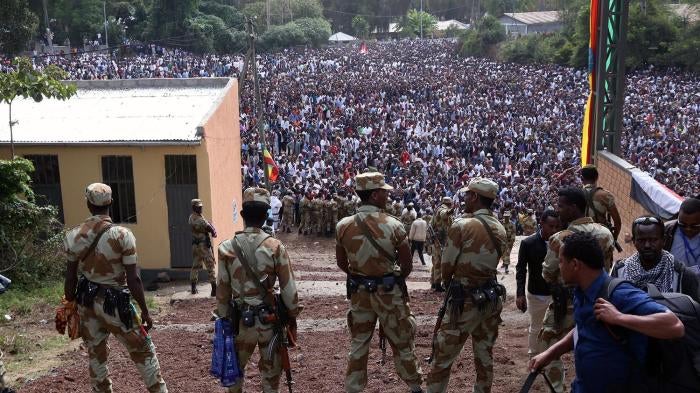

On October 2, 2016 scores of people, possibly hundreds, died at the annual Irreecha cultural festival of Ethiopia’s ethnic Oromo people, following a stampede triggered by security forces’ use of teargas and discharge of firearms in response to an increasingly restive crowd. Some died after falling into a deep open trench, others drowned in the nearby lake while fleeing security forces, and witnesses told Human Rights Watch that others were shot by security forces. Many were trampled after armed security forces blocked main roads exiting the site, leaving those fleeing with few options.

Irreecha is the most important cultural festival of Ethiopia’s 35 million ethnic Oromos who gather to celebrate the end of the rainy season and welcome the harvest season. Massive crowds, estimated in the millions, gather each year at Bishoftu, 40 kilometers southeast of Addis Ababa every year. Until 2016, there had never been any major incidents or security problems despite annual massive crowds.

The government eventually said the official death toll was 55 people but opposition groups estimate nearly 700 died. Neither figure has been substantiated or explained. An investigation by the government affiliated Ethiopian Human Rights Commission was not transparent or credible and there is no evidence of accountability.

One year on, government has failed to meaningfully investigate the security forces’ response, and there is no independent and credible determination of the death toll. Based on analysis of dozens of videos and photos and over 50 interviews with attendees and other witnesses, this report documents the abuses which occurred on October 2, 2016 at Bishoftu. It is not intended to be a comprehensive investigation; rather, the findings underscore the need, not only for credible investigations into what occurred in 2016, but also for the government to ensure security forces refrain from the unnecessary use of force and act professionally at this year’s event, currently scheduled for October 1, 2017.

The 2016 Irreecha festival was held following a year of protests against government policies and security force aggression that left over 1000 people dead across Ethiopia and tens of thousands detained by security forces.

Faced with longstanding tensions that had been greatly exacerbated by a year of brutal repression, the government attempted to play a more dominant role than in previous years with increased security presence and attempts to control who took the stage during the 2016 Irreecha. According to attendees, this prompted anger within the crowd and led some people to get on stage to lead anti-government chants. The security forces initially sought to control the crowds, using teargas. Later, witnesses described security forces firing into the crowd using live ammunition.

In several videos recorded at the scene, numerous gunshots could clearly be heard as crowds flee. Witnesses reported seeing people killed with bullet wounds.

Ethiopia’s then communication minister and other senior officials stated that security forces were unarmed and there was no live ammunition at Irreecha, despite photos clearly showing heavily armed security forces at the event and several witness accounts of gunfire and bullet wounds.

International guidelines, such as the United Nations Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials, stipulate that the police should use force only as a last resort, and refrain from the use of firearms except in the face of extreme danger to themselves or others that cannot be prevented by other means. While the crowd at Irreecha was chanting anti-government slogans, and expressing anger against the government, it does not appear that there was violence from the crowd or an imminent threat to security forces.

There were numerous protests around Bishoftu in the hours and days after the event. Witnesses told Human Rights Watch that security forces shot live ammunition during some of these protests as well. In the days that followed, many individuals who attended Irreecha were arrested in their home communities.

In the week that followed, angry youth attacked government buildings and private businesses, leading to an abusive and far-reaching state of emergency, lifted in August 2017. During the state of emergency, security forces arbitrarily detained over 21,000 people in “rehabilitation camps,” artists, politicians, and journalists were tried on politically motivated charges; there were increased limitations on internet access; and many communities reported heavier than usual military presence.

Despite government promises of “deep reform” to address protester grievances, there has been little movement on fundamental issues raised by protesters, including the lack of political space and brutality of the security forces, during the year-long protests heightening tensions further ahead of this year’s Irreecha.

The government expressed regret over the loss of life at the 2016 Irreecha, but also exonerated security forces, blaming the chaos and deaths, as it often does, on “anti-peace forces.” Many Oromo interviewees told Human Rights Watch that they believe the heavy-handed security forces’ response at Irreecha was an intentional and planned massacre, a narrative whose resonance only serves to increase tensions still further ahead of this year’s festival, which could be a flashpoint for further unrest.

The government has strongly resisted calls for international investigations, including into Irreecha. The consistent lack of credibility of government investigations into ongoing abuses and the scale of the crimes being committed are a compelling argument for the need for an independent, international investigation into abuses during the protests, the state of emergency and the events on October 2. Ethiopia’s international allies should call on the government to agree to such an inquiry.

Importantly, the government should take urgent steps to ensure Irreecha 2017 unfolds with far greater restraint and competence on the part of the security forces, and that effective steps are taken to minimize and de-escalate any risk of violence. The government should consider whether a smaller or lower-profile security presence would be the best way to accomplish those goals. Security forces should expect and tolerate free expression which may be critical of the policies of the ruling party and not use force or threat of force to silence critical speech.

Recommendations

To the Government of Ethiopia

Regarding the 2016 Irreecha Festival

- Support a credible, independent and transparent investigation into the use of force by security forces and discipline or prosecute those found responsible for the excessive use of lethal force and other crowd control tactics that led to fatalities.

- Ensure authorities who have received inquiries from families of people who have disappeared or are missing reply promptly, providing all known information on the whereabouts and fate of these people and on steps being taken to acquire such information if not readily available.

- Promptly release from custody and drop any charges against all persons arbitrarily detained for attending 2016 Irreecha, or otherwise peacefully exercising their fundamental rights, such as freedom of expression, association, and assembly.

Regarding the 2017 Irreecha Festival

- Ensure law enforcement and security organs issue clear orders to their forces that the use of force, including firing of tear gas and discharging firearms in the air, should be strictly minimized, and that use of excessive force will be punished. Permit the 2017 Irreecha festival to proceed without undue government obstruction.

- Ensure that any security plans for the festival are carefully tailored to minimize and de-escalate the risk of violent confrontation.

To Ethiopia’s International Partners

- In the absence of decisive steps to establish a credible domestic investigation into abuses in Ethiopia since November 2015, including the 2016 Irreecha festival and the subsequent state of emergency, all concerned governments should press for an independent international investigation into abuses and press for accountability for the excessive use of force in protests and during the 2016 Irreecha.

- Publicly call and privately press for the release of anyone arbitrarily detained during the time of the protests, Irreecha, and the state of emergency, including those prosecuted under the criminal code or anti-terrorism law.

- Improve and increase monitoring of trials of detainees to ensure trials meet international fair trial standards.

- Publicly and privately raise concerns with Ethiopian government officials at all levels regarding their response to the 2016 Irreecha festival, urge the government to ensure that appropriate levels of force are used in 2017 Irreecha and urge the government to ensure that security presence does not exacerbate an already tense situation.

- Attend the 2017 Irreecha festival and monitor festival preparations in the days before the festival.

- Urge Ethiopian officials to invite relevant United Nations and African Union human rights mechanisms, including the UN Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association; and the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention to visit Ethiopia.

To All Entities Tasked with Managing the Irreecha Festival, including the Gadaa Council and All Government Bodies Tasked with Security

- Ensure there are multiple points of egress from the festival site. Security forces should not block these exits.

- Any and all trenches should either be filled, fenced, or otherwise managed in a way that minimizes risks.

Methodology

This report is based on research conducted between October 2016 and August 2017 in Ethiopia and three other countries. Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed 51 people, including 26 individuals from 10 different zones in Oromia who attended Irreecha in 2016, another 15 who were arrested in their communities due to their alleged involvement in Irreecha and 10 other individuals with knowledge of the event including members of the security forces, government officials, health workers, journalists and academics. All were interviewed individually in person, by telephone, or via other methods of communication.

No one interviewed for this report was offered any form of compensation. All interviewees were informed of the purpose of the interview and its voluntary nature, including their right to stop the interview at any point, and gave informed consent to be interviewed.

Human Rights Watch also consulted court documents, photos, videos and various secondary material, including academic articles, reports from nongovernmental organizations, and information collected by other credible experts to corroborate details or patterns of abuse described in the report. Human Rights Watch took various steps to verify the credibility of interviewees’ statements. All the information published in this report is based on at least two and usually more than two independent sources, including both interviews and secondary material, including videos. The initial moments of the stampede and the events leading up to the stampede were captured in dozens of videos from individuals on stage and in the crowd.

In the past, Ethiopian authorities have harassed and detained individuals for providing information or meeting with international human rights investigators, journalists, and others. Even after individuals flee Ethiopia, family members who remain may be at risk of reprisals. To protect victims and their family members against such reprisals identifying details, including locations of interviews are withheld where such information could suggest someone’s identity.

Abbreviations

EPRDF: Ethiopian Peoples’ Revolutionary Democratic Front

OFC: Oromo Federalist Congress

OLF: Oromo Liberation Front

OMN: Oromia Media Network

OPDO: Oromo People’s Democratic Organization

SNNPR: Southern Nations Nationalities’ and Peoples’ Region

TPLF: Tigrayan Peoples’ Liberation Front

UNESCO: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

I. Background

The Protests of 2015 and 2016

Oromia is home to many of Ethiopia’s estimated 35 million ethnic Oromo, the country’s largest ethnic group. Government repression across the region has escalated steadily over the years. Ethnic Oromo who express dissent are often arrested and tortured or otherwise illtreated in detention.[1] Abuses against individuals of Oromo ethnicity occur within a broader pattern of repression of dissenting or opposition voices in Ethiopia.

Oromo concerns about the government’s proposed expansion of the municipal boundary of the capital, Addis Ababa, triggered protesters in November 2015. Protesters feared that the Addis Ababa Integrated Development Master Plan would displace Oromo farmers living around Addis Ababa, as has increasingly occurred over the past decade. The protests soon spread to hundreds of locations in Oromia where people complained of displacement, numerous historical grievances and brutality by security forces during the protests.[2] In July 2016, protests spread to the Amhara region.

During the 2015-2016 protests, security forces killed over 1,000 protesters and arrested tens of thousands of students, teachers, opposition politicians, health workers, and those who sheltered or assisted fleeing protesters.[3] While many detainees were released before Irreecha in October, an unknown number remained in detention without charge or access to legal counsel or family. Most of the leadership of the legally registered opposition party, the Oromo Federalist Congress, have been charged under the anti-terrorism law, including Deputy-Chairman Bekele Gerba, and remain behind bars today.[4]

The government’s framing of the protests as being orchestrated or exacerbated by “anti-peace elements” was frequent prior to Irreecha in 2016. While in the latter stages of the protests there were clearly armed elements among the protesters, the protests were overall predominantly peaceful -- the government overemphasized the protester armed element and continuously denied the disproportionate armed response from security forces.[5] Protesters have repeatedly told Human Rights Watch that the Ethiopian government’s continued characterization of protesters as “anti-peace elements” and security forces routinely engaging in brutality exacerbated anger among people in Oromia.[6]

Ethiopia’s Human Rights Commission – a government-funded entity – has produced two reports into the 2015-2016 protests. In Human Rights Watch’s analysis, neither is impartial nor demonstrates the independence that is needed for investigations to be credible. Both reports concluded that federal security force response was proportionate to threats posed by protesters.[7]

Irreecha

The Irreecha festival is held annually on the last Sunday in September or the first Sunday in October near the shores of Lake Hora in Bishoftu [also called Debre Zeit], Ethiopia, 40 kilometers southeast of Addis Ababa. Massive crowds gather there each year and in other locations around the world where there are ethnic Oromo communities.[8] The event serves to unify Oromo people, regardless of geographic origin, politics, or religion.[9] Irreecha is presided over by the Gadaa Council, a traditional council of Oromo elders, independent of the government, who play a key role in managing the festival.[10]

Previous governments, including the Derg government, which ruled Ethiopia from 1974 to 1991, restricted the Irreecha festival.[11] Since 1991, under the current Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) government, Irreecha has been permitted and held without any major security problems until 2016.[12] On December 1, 2016, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) included the Gadaa system, the traditional Oromo political system, on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.[13] Ethiopia’s government played a major role in pushing for this designation.[14] Irreecha is one feature of this traditional system according to the UNESCO nomination documents.[15] The leader of the Gadaa Council is known as the Abaa Gadaa, a position currently held by Beyene Sembetu. The Abaa Gadaa traditionally opens the festival with a blessing. Attendees then go to nearby Lake Hora (Hora Arsadi) to give thanks and pray to Waqaa [God] for the end of the rainy season and the beginning of the harvest season.[16]

The recent history of Irreecha reflects the increasingly fraught and complex relationship between the government and Oromo communities. While Irreecha is ostensibly apolitical, many regular Irreecha attendees told Human Rights Watch that recent years have not only seen increasing crowds but also increased government involvement and increased expressions of resistance to government policies. A number of regular attendees report more security and surveillance, particularly over the last several years, as the relationship between the EPRDF government and the Oromo population has deteriorated.[17]

In the leadup to 2016 Irreecha, some Oromo stakeholders voiced concern about the increased politicization of the festival, particularly after a year of protests. The United Oromo Gadaa Council [“Gadaa Council”]asked Irreecha participants in August 2016 to avoid “bringing to the celebrations the flags of any and all political organizations.”[18]

The Irreecha festival site is outdoors on the shore of Lake Hora and is approximately 130 meters by 90 meters, small given the size of the crowds. With Lake Hora on one side of the site there are limited egress options should there be the need to evacuate a large amount of people in a short time. This makes it even more critical that appropriate crowd control measures are employed by security forces during Irreecha.

See below for overview and close-up maps of Bishoftu town and the Irreecha festival site:

II. The Events of 2016 Irreecha festival

Increased Tensions Ahead of Irreecha

Some Oromo expressed nervousness about attending the 2016 Irreecha given the tensions in Oromia and fear over the presence of the same security forces that had reacted with brutality to protests over the previous year. Some individuals told Human Rights Watch that they were told by local security officials or party cadres not to attend Irreecha and were pressured to convince others not to attend. One 14-year-old Grade 6 student from East Wollega zone described his experience:

The local police and some local government officials came to my school and took me and several classmates into the principal’s office. They told us not to go to Irreecha, and to tell other students not to go. They suspected we would protest the government there. We were the older students so they always thought we organized the local protests.[19]

The Gadaa Council had reportedly expressed concerns to the government during their annual discussions with authorities about the role the government wanted to play at Irreecha. Individuals who were present at the meetings between the Council and the government told Human Rights Watch that the Council had reportedly also expressed concern about security preparations for the festival including warning the government about the danger of a very deep natural trench that was located near the stage and recommended fencing it or filling it in.[20]

Attendees described a much larger than usual security presence, including many more security checkpoints, both on the routes to Bishoftu and inside the city. While there had been security checkpoints at past Irreechas, attendees reported much more stringent security provisions. A 21-year-old man from Shashemene described the atmosphere at the 2016 festival:

When we arrived, what we used to know and what we saw now was so different. Military vehicles and machines were everywhere. As I approached a checkpoint near the stage some plain clothes security personnel, some in Oromo cultural clothes, were arresting a few people. I don’t know why. The whole feeling [of Irreecha] was different. It felt like a political event, not a cultural and religious event.[21]

One long-time attendee further explained:

Local police and regional police usually take responsibility for most of the policing. They speak our language, they know how important this [Irreecha] is, and they know the trench, they know the area. This year there were many federal security forces, speaking a language I do not know. They were heavily armed, whereas the Oromo police are not usually armed. They made it look like a military operation.[22]

All witnesses described seeing the presence of military helicopters – for the first time at Irreecha -- flying low overhead in the lead up to the ceremony beginning, dropping pamphlets to welcome people to Irreecha.[23] One witness said:

We could feel the wind and some leaves from trees would fall. [The helicopter] was very low. This was done to intimidate. It dropped some papers into the crowd. It was the first time I had seen a helicopter up close and was scared but believed in such a large population they would not attack us. We all crossed our arms in defiance against the helicopter.[24]

Attendees also said that people sang and chanted while crossing their hands above their heads, a popular symbol of the Oromo protest movement. One elder and long-time participant described to Human Rights Watch the presence of far more young people “who seemed more interested in making anti-government gestures and songs than participating in Irreecha itself.”[25]

Irreecha Morning of October 2, 2016

As the ceremony began, on the morning of October 2, 2016, tensions within the massive crowd built when government officials from the Oromo Peoples’ Democratic Organization (OPDO) appeared on stage with Nagasa Nagawo, a former Abaa Gadaa who is perceived to be closely aligned with the government.[26] According to interviewees, normally the current elected Abaa Gadaa would appear and give a traditional blessing to begin Irreecha. Nagasa took to the stage and spoke briefly. The crowd grew more angry and restless. Some participants jumped on stage. As the master of ceremony (MC) pleaded for calm, a man, Gemada Wariyo, got on stage, grabbed the microphone from the MC and led the crowd in anti-government chants.[27]

Unarmed security officials between the stage and the crowd, believed by attendees to be Oromia regional police,[28] tried unsuccessfully to prevent members of the crowd from getting on stage. In the meantime, armed security forces were standing behind and next to the stage. The ceremony was disrupted while some of the dignitaries left the stage,[29] while some people who got on stage crossed their arms above their heads in a sign of protest.

What appears to have been tear gas was fired from an unknown source near the stage triggering panic in the crowd. A number of witnesses told Human Rights Watch they believed they heard a gunshot.[30] Several more tear gas canisters were fired over the next 15 seconds, including one within 10 meters of the trench.[31] Ten interviewees said they saw tear gas canisters being dropped from helicopters, although it is not likely this was the initial tear gas that that was fired.[32]

As one man who was close to the front of the crowd described:

People got on stage after previously being pushed back by the police. So even more felt emboldened and moved towards the stage. That was when things got out of control. We heard what sounded like a gunshot and teargas fired. After the teargas we heard many gunshots but don’t know from where as we were blinded by teargas, dust and the chaos.[33]

The Stampede

While there is no evidence that security forces on stage fired into the crowd, attendees report hearing “many gunshots” during the stampede. This is backed up by several videos of 2016’s Irreecha in which numerous gunshots and firing of teargas can be heard.[34] In multiple videos, over the next minute a series of single rifle shots including at least one burst of three shots can be heard.[35] Human Rights Watch was not able to ascertain whether these gunshots were live ammunition or rubber bullets.[36] In some videos, security forces are pointing weapons into the air but for some of the audible gunshots, no video footage is available. As Human Rights Watch has documented in many of the protests preceding Irreecha 2016, hundreds of people have been killed by security forces’ use of live ammunition,[37] so when the pattern seemed to be repeating itself at Irreecha, panic very quickly set in.

Based on available evidence, people ran in various directions immediately after the tear gas was fired. In video footage, attendees appear blinded by dust and teargas and unaware of which direction to run for safety. Some people said that they couldn’t determine the origin of the gunshots although most told Human Rights Watch they believed they were coming from the armed security forces that were stationed next to the stage.[38]

As people ran, some fell into a very deep trench nearby and were suffocated when other people fell on top of them. [39] Others were trampled in the ensuing chaos. According to interviewees, some also drowned in nearby Lake Hora.[40] Armed security forces, previously either offsite or behind the stage moved forward closer to the festival site and onto the stage. People who had fled toward the exit road at the back of the festival site found armed security forces there and quickly fled back into the festival site. Numerous witnesses report the security forces that were blocking exits pointing weapons at the fleeing crowd.[41]

Human Rights Watch interviewed eight people, none of whom knew each other, who were caught in the stampede and described seeing people with gunshot wounds. One student from East Wollega zone said:

I saw three young men who had been hit with bullets. Everyone was saying ‘they’ve been shot, who are they?’ I had crawled to the edge of the site and lay there. I was close to those three bodies. I saw a government vehicle come and quickly load those bodies and take them away. There were many other bodies lying down not moving. It was all very confusing. I didn’t know who had shot them or from which direction just that they had been shot and were not moving. The exits were closed. They were open before the stampede and then as the stampede happened they [security forces] were standing at the exits. I saw them pointing guns at the crowd but don’t know if they were shooting. It was confusing and I heard many shots.[42]

Another businessman described:

I was running with the crowd and was nearing the road and the person in front of me fell over. I tripped over him. I got up but he didn’t. I looked at him and he had been shot and blood was pouring out of his neck. I was very scared. There were soldiers running around and shooting on the road and I saw other people with small guns [pistols] but I don’t know who specifically shot him.[43]

Another student described:

I saw several plain clothes men shooting and killing people at close range. For example, I saw one plain clothed man shoot and kill [name withheld] who was a lecturer at Tepi University. He was very famous and I knew him. I saw him fall down but I could not assist him because I was also running for my life. A number of people I know were killed that day by the bullets. I saw their bodies, they were all hit by bullets. I know them because we are from the same village.[44]

Four of those individuals said family members next to them were shot and killed.[45] It was not clear who had shot them. Each showed videos and photos from the funerals that were held in the days following the festival. A body had been returned to the family in just one of those four incidents.[46]

Four individuals described some people in the crowd who they believed were security officials dressed in Oromo cultural clothes, who pulled out pistols.[47]

Four witnesses described various military vehicles coming to the festival site and quickly loading bodies in the vehicles, both those who had been injured or those who had been killed from being trampled or shot.[48] Videos show a military vehicle arriving several minutes after the stampede.[49]

Once most of the people had been cleared from the festival site, festival goers along with some security forces who had been near the stage helped people who were trying to climb out of the trench.

One young boy who fled the stampede and ran into the lake described the scene at

the shore:

I, like everyone, was looking for somewhere to run. I could see many people had fallen into the ditch [trench]. It scared me. When I got to the lake there were many people in the lake - some had clearly drowned. I could swim but I know many people cannot. I waded alongside the edge of the shore and stayed there until it was safe to go into town.[50]

The Death Toll and Aftermath of Irreecha

Many people went to Bishoftu hospital or nearby health facilities to find out the whereabouts of their loved ones who had either been killed or had disappeared. It is not clear where those who had drowned or been shot were taken although several people whose relatives had not returned from Irreecha told Human Rights Watch that sympathetic local security officials had told them that those who had been shot had been taken to the federal police hospital near Mexico Square in Addis Ababa.[51]

There were sporadic protests in Bishoftu that day and evening with many reports of security forces, both Oromia police and military, firing munitions into the air and live ammunition into crowds.[52] One person told Human Rights Watch: “At the circle I saw someone shot in front of me. We managed to take him [name withheld] to his family. The next day the funeral was held in their village [name withheld] which was just outside of Bishoftu.”[53]

Another person described coming into town after being separated from his friends during the event:

I think it was about one hour after the stampede. Gunshots had slowed down by this time. I went back into town on the main road. The Agazi [military] were in town and I heard gunshots everywhere. Some were clearly shooting in the air but many people were shot too. They [security forces] seemed to be trying to clear the streets but were doing it through bullets. In the middle of town, there was another protest. Oromia police were also armed and shot some people there.[54]

Another woman described the growing frustration over the lack of information about missing relatives and the continuing protest the next day:

The next day I went back to hospital and there were many people in front of the hospital crying and screaming “where have you taken the bodies of our children?” I and many of those people protested that day at the circle in Bishoftu. The soldiers were shooting into the crowd. I saw four people [names withheld] killed during that protest. Those bodies were taken to the hospital but don’t know what happened to them from there.[55]

Some family members whose relatives had been killed by gunshots either during the stampede or during protests in Bishoftu had bodies returned to their home communities within several days, but four family members told Human Rights Watch that while different people had seen them shot and killed, their bodies have not been returned to their families. Months later, at the time they spoke to Human Rights Watch, their whereabouts were still unknown.[56]

While there were some reports of arrests in and around Bishoftu the day of Irreecha, based on available evidence, the scale of arrests appears relatively minor.[57]

Many people described general chaos, many security checkpoints, and abuses by security forces on their way home. One person from Shashemene describes:

We were taking a bus back home. The road was blocked near Ziway. Military made all those who had attended Irreecha get out and we lay on the ground and they hit us with sticks and walked over our backs. Only those wearing cultural clothes were pulled out. This was at 8pm between Negelle and Ziway.[58]

The government stated initially that 52 people had died during Irreecha, eventually rising to 55 several days later.[59] The opposition political party Oromo Federalist Congress said 678 died.[60] It is not clear how either group determined these figures.

The government limits independent media and restricts nongovernmental organizations, both domestic and international, so that currently no one has had the access, expertise or impartiality necessary to determine a precise, credible death toll. Based on estimates from health care workers, reports of funerals and missing persons, and incidents that were documented, it is clear that the death toll is much higher than government estimates, but without independent investigators being given open access, and witnesses and health workers being free to speak without the fear of reprisal, the exact number will not be known. The government has shown little willingness to meaningfully investigate the conduct of the security forces.

The government put forward staff at Bishoftu hospital to lend credibility to its claims that the death toll was 55 and that the cause of death was the stampede and nothing else.[61] But three health workers who worked in health facilities where the dead and injured were brought told Human Rights Watch that they had been instructed by Ethiopian security forces or government cadres not to speak to journalists or anyone about the numbers of people killed or how people had been killed.[62]

Information health workers shared indicated a much higher number of people that died. During the year-long protests, Human Rights Watch documented harassment and arrests of medical staff for speaking out about killings and beatings by security forces, or in some cases for treating injured protesters.[63] The government’s effort to immediately try to convince the public that the stampede was the cause of death was in part to counter the narrative that had already taken root in many Oromo communities that large numbers of attendees were shot and that it was a deliberate massacre by the government.

Reprisals for Attending Irreecha

15 individuals from 10 of the 17 zones in Oromia told Human Rights Watch that when they returned from Irreecha in 2016 they had been told by various local contacts that lists had been prepared by local intelligence and security officials of those who had been to Irreecha and that they were to be arrested in the coming days.[64] Ten of those festival goers were then arrested. One in Bale was taken to a local police station and questioned for three days. He was asked about why he went to Irreecha, who he went with, and was accused of “starting violence.” [65] Two other people were taken to Tolay military camp. They told Human Rights Watch that soldiers beat them both badly.[66] One said he was strung up by his wrists, beaten and accused of causing the unrest at Irreecha.[67]

He recalled:

They were accusing me of shooting at security forces, of throwing stones on stage - things that didn’t happen. It was clear they wanted me to admit I started problems. I went there to my first Irreecha to celebrate being Oromo. They were targeting those who went to Irreecha but I had never even been to a protest before.[68]

One person described being arrested in Arsi Zone on October 4, 2016 and taken to the local police station where someone from the local administration questioned him. “He was accusing me of starting anti-government chants. The only time I had seen him previously was at Irreecha. He was on the small bus we had taken from our village.” [69]

All of those who told Human Rights Watch that they had been detained said they had never been to court. They all described being beaten by security forces in detention.[70] It is difficult to know the scale of these arrests across Oromia in part because of mass arrests that were being carried out in connection with the destruction of government buildings/private properties. However Human Rights Watch has received numerous reports of arrests of Irreecha festival participants from 16 out of 17 zones in Oromia.

An Oromo elder who had attended each of the five previous Irreecha festivals described his arrest:

When I returned to the kebele I was registered by them [kebele administrators] because I went to Irreecha. They said it was to help identify those missing. The next morning, I was arrested. We were sitting in a group mourning the death of our family members. The security man [plain clothes] came with several local police to us and said “Why are you sitting in a crowd mourning for your family? No one died, you should not mourn.” Then they said, “Why did you start the violence at Irreecha?” We were all arrested and taken to the police station. I was beaten there by the agazi [military].[71]

A 14-year-old boy from Negelle Borana told Human Rights Watch that his parents had gone to Irreecha in 2016 and they had never returned. As he looked for them in hospitals he found that three of his classmates who had been protesting had been arrested. Five other classmates had disappeared. He later fled Ethiopia with two friends to avoid arrest.[72]

A number of individuals reported reprisals against family members of those who attended Irreecha. One young man from Wollega zone said: “I did not go back to my village but got a call from family that they were arresting all those who went to Irreecha. Then they came to my house. Since I wasn’t there they arrested my 78-year-old father. He was arrested until I was produced.” [73] He did not know his father’s current whereabouts.

In other communities, individuals had been pre-warned by local police or local party officials not to attend Irreecha. A 24-year-old Grade 11 student told Human Rights Watch: “We were told there would be serious consequences should we go or should others from our class go. I went, and when I returned from Irreecha local security forces arrested me. They beat me seriously for two weeks accusing me of ignoring their orders and starting Irreecha violence. I was forced to do strenuous exercise and was released after two weeks.”[74]

Several other individuals who were at Irreecha described being arrested after they had told their friends or communities about what had happened at Irreecha. Each of those was interrogated and asked questions including “why are you spreading lies about the government?”, “why are you exaggerating what happened?”[75]

In the days following Irreecha, protests swept throughout Oromia and other parts of Ethiopia. In sharp contrast to previous protests, protesters targeted government buildings and private investors that were perceived to be close to the government. Buildings were looted and destroyed, there were numerous jailbreaks, and police stations were overrun.[76]

One man who said he was part of a mob that destroyed local government buildings near Ziway two days after Irreecha encapsulated the shift in attitude:

It was always important to us that we [protesters] do not engage in violence. We knew that the only way we would gain support from the world is if we spoke about issues in a peaceful manner. But every time we would go out we face bullets, we face arrests and beatings. After a while, we started to debate the limits of our non-violent action. When you are bereft of options and the government and the world ignores your concerns, it is inevitable there would be violence. The fire was already there, it was smoldering, killing us at Irreecha poured fuel on the fire. The violence started sooner than any of us thought.[77]

The State of Emergency

On October 9, 2016 the government announced a country wide six-month state of emergency.[78] It was renewed again for another four months in April 2017. It was lifted on August 4, 2017.[79]

Measures under the state of emergency were overly broad. The implementing directive prescribed draconian restrictions on freedom of expression, association, and assembly that went far beyond what is permissible under international law and signaled an increasingly militarized response to the situation.[80]

The directive included far-reaching restrictions on sharing information on social media, watching diaspora television stations, and closing businesses as a gesture of protest, as well as curtailing opposition parties’ ability to communicate with the media. It specifically banned writing or sharing material via any platform that “could create misunderstanding between people or unrest.”[81]

It banned all protests without government permission and permitted arrest without court order in “a place assigned by the command post until the end of the state of emergency.” It also permits “rehabilitation” – a euphemism for short-term detention that often involves physical exercise. During the state of emergency, over 21,000 people were arrested according to government figures, many of them in these “rehabilitation camps.” As of August 4, 2017 around 8,000 remained in detention.[82] Major opposition figures like Dr Merera Gudina were arrested and charged under the criminal code.[83]

The state of emergency could have provided an opportunity for the government to embark on the “deep reform” it promised in response to the year-long protests. The reforms it ended up implementing included tackling corruption, cabinet reshuffles, and a dialogue with what was left of opposition political parties. The government also pledged youth job creation and good governance. Crucially, these are not the fundamental issues that protesters raised during the hundreds of rallies between November 2015 and October 2016. The government largely redefined protester grievances in its own terms, ignoring more fundamental demands to open up political space, allow dissent, and tolerate the free expression of perspectives that are critical in such a large and ethnically diverse country.

III. Government Response

In the wake of Irreecha, the government expressed condolences and declared three days of mourning, labeling the incident as an unfortunate accident.[84]

At the same time, government officials repeatedly and publicly blamed “anti-peace elements” for the deaths. For example, Prime Minister Hailemariam, in an address on national television blamed the deaths on the “violent forces who have a hidden political agenda who tried to disrupt the celebration and turn the situation into chaos.” He also thanked security forces for their “great efforts to maintain peace and order.”[85] Eshetu Dessie, the then vice president of Oromia regional state said “The innocent participants of the Irreecha died due to the violence caused by the anti-peace forces during the celebration.”[86]

The government vehemently insisted that the only people who were killed at Irreecha died in the stampede, and insisted that security forces did not use live ammunition.[87] Then federal government communications minister Getachew Reda said “of the people's bodies who were collected, they do not have any bullet wounds whatsoever. They were killed in the stampede. The security forces were mostly unarmed. There was no force involved on the part of the security forces."[88] This was reiterated in a strong statement from then foreign minister Dr Tedros Adhanom who said that “it is quite clear from the videos that there was no shooting and the police were unarmed.”[89]

Despite promises to investigate[90] no transparent or credible investigation has been undertaken. In April, the government-affiliated Ethiopian Human Rights Commission presented orally to parliament the results of its investigations into protests between June and September 2016.[91] It included reference to October’s Irreecha concluding that “security forces did not use force against the crowd except firing tear gas and this measure was proportionate.”[92] No official written version is publicly available and the Commission has not commented on the methodology they employed to make such conclusions – conclusions that largely replicate the government’s narrative.

IV. International Law and Appropriate Use of Force

The United Nations’ Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials offer guidance as to how law enforcement agencies should limit and control the use of force so as to ensure respect for human rights. The Principles make clear that law enforcement officers should:

- “as far as possible, employ non-violent means before resorting to the use of force and firearms” and use force or firearms “only if other means remain ineffective or without any promise of achieving the intended result;”

- Where the use of force is unavoidable, “exercise restraint in such use and act in proportion to the seriousness of the offense and the legitimate objective to be achieved” and “minimize damage and injury, and respect and preserve human life;”

- Ensure that the development and deployment of non-lethal weapons are “carefully evaluated in order to minimize the risk of endangering uninvolved persons,” and that the use of such weapons is “carefully controlled;”

- Equip law enforcement officers with defensive equipment, “in order to decrease the need to use weapons of any kind.” [93]

Police should exercise particular restraint when using teargas or other non-lethal weaponry in situations when its use could cause death or serious injury.

The Principles also stipulate that law enforcement shall not use force to disperse lawful and peaceful assemblies; that the use of force should be “avoided or, where that is not practicable, restricted to the minimum extent necessary” in dispersing unlawful but non-violent assemblies; and that in dispersing violent, unlawful assemblies, law enforcement shall only use firearms “when less dangerous means are not practicable and only to the minimum extent necessary.” More generally, “Law enforcement officials shall not use firearms against persons except in self-defence or defence of others against the imminent threat of death or serious injury, to prevent the perpetration of a particularly serious crime involving grave threat to life…and only when less extreme means are insufficient to achieve these objectives.”[94]

While tensions in the crowd were high and many people were clearly protesting against the government, available evidence indicates that the crowds did not appear to pose a direct threat to security forces.

Firing tear gas and discharging firearms exacerbated an already tense situation, causing widespread panic and triggering the stampede. Any discharge of live ammunition at members of the crowd was clearly disproportionate, and the use of tear gas and non-lethal munitions appears to have been as well. Blocking main roads out of the site through the presence of armed security forces caused people to turn back into the crowds caused further casualties. At best this was a disastrous mishandling of a complex crowd control situation. At worst, it was a deliberate use of disproportionate force that led to scores—or more likely hundreds—of needless deaths.

If force was used to disperse the crowd rather than in response to a perceived threat posed by them, it may also have constituted a violation of the rights to free expression and assembly.

V. 2017 Irreecha

Irreecha is about peace, unity, and our culture. It is not about politics. And the government changed all that last year. We do not want problems this year. This government just needs to allow us to celebrate Irreecha and not try to take it over again. They don’t need to be there and nor do the soldiers. There were never problems before. Just let us practice our traditional culture.

−75-year-old elder from Ambo, Oromia, Ethiopia, August 2017

The lack of space in Ethiopia for open critical debate, including the decimation of the Oromo Federalist Congress and long-standing limitations on independent media and civil society, meant there are few independent voices in-country that are deemed credible to protesters to challenge the narrative that has taken root among many Oromo that the deaths at Irreecha resulted from an intentional and planned act by the government. Restrictions under the state of emergency further decreased space for any critical discussion about the events of Irreecha 2016. Devoid of fora for open dialogue about sensitive issues, including security force handling of Irreecha, the narrative of deliberate massacre remains a strong one within Oromo communities.

While there has been little mention from senior government officials about 2016 Irreecha since the state of emergency was called on October 9, 2016, there continues to be considerable anger within many Oromo communities about the events that day. This is critical to understand when assessing the potential for the 2017 Irreecha to be problematic and underscores the deep mistrust that exists between the Oromo people and the government, and the lack of avenues available to seek redress.

It is likely that tensions and frustrations will be very high at the 2017 Irreecha, and that there will be more protests and anti-government songs and chants. Ethiopia’s government should develop an approach that aims to de-escalate tensions and prevent any unnecessary and disproportionate use of force by security forces. Security forces should tolerate expressions of dissent, and government, in particular the federal government, should consider whether it would be wise to limit the security forces’ involvement in the event.

Acknowledgements

This report was written by Felix Horne, Africa researcher in the Africa division of Human Rights Watch, based on research carried out by Felix Horne and Abdullahi Abdi, research assistant in the Africa division of Human Rights Watch. It was edited by Maria Burnett, associate Africa director. Chris Albin-Lackey, senior legal advisor, and Babatunde Olugboji, deputy program director, provided legal and program review respectively.

Abdullahi Abdi, research assistant in the Africa division, provided production assistance and support. Josh Lyons, in the emergencies division assisted with satellite imagery analysis. The report was prepared for publication by Olivia Hunter, publications coordinator; Jose Martinez, senior coordinator; and Fitzroy Hepkins, administrative manager.

Human Rights Watch would like to thank the fixers and translators in Ethiopia and elsewhere who cannot be named for security reasons but whose contribution made this report possible.