Summary

Since March 26, 2015, Saudi Arabia has led a coalition of nine Arab countries in a military campaign against Houthi forces in Yemen. These operations have had the military support of the United States, the United Kingdom, and other countries. The fighting has resulted in more than 3,200 civilian deaths, over 60 percent of them from coalition airstrikes, according to the United Nations. Another 5,700 civilians have been wounded in the conflict. Airstrikes have damaged or destroyed numerous civilian objects including homes, markets, hospitals, and schools, as well as commercial enterprises, the subject of this report.

This report documents coalition airstrikes between March 2015 and February 2016 on 13 civilian economic structures including factories, commercial warehouses, a farm, and two power stations. These strikes killed 130 civilians and injured 171 more. The facilities hit by airstrikes produced, stored, or distributed goods for the civilian population including food, medicine, and electricity—items that even before the war were in short supply in Yemen, which is among the poorest countries in the Middle East. Collectively, the facilities employed over 2,500 people; following the attacks, many of the factories ended their production and hundreds of workers lost their livelihoods.

Each of these attacks appeared to be in violation of international humanitarian law, or the laws of war. The laws of war prohibit deliberate attacks on civilian objects, attacks that do not discriminate between military targets and civilian objects, and attacks that disproportionately harm civilian objects compared to the expected military gain of the attack. Civilian objects include factories, warehouses and other commercial enterprises so long as they are not being used for military purposes or become a military objective. Those attacks on civilian objects that were committed willfully – deliberately or recklessly -- are war crimes.

Taken together, the attacks on factories and other civilian economic structures raise serious concerns that the Saudi-led coalition has deliberately sought to inflict widespread damage to Yemen’s production capacity.

Human Rights Watch identified munitions used at six of the sites visited: the United States produced or supplied four types of munitions identified, and the United Kingdom produced or supplied two types, including a Paveway IV guided bomb produced in May 2015, after the start of the coalition’s aerial campaign.

This report is based on Human Rights Watch field research in the Yemeni capital, Sanaa, and the governorate of Hodaida in March 2016. Human Rights Watch interviewed 37 witnesses at the sites, searched for possible military targets in the vicinity, and examined remnants of munitions found. The report also includes details of previously documented airstrikes on civilian economic structures.

According to the Sanaa Chamber of Commerce and Industry, coalition airstrikes damaged or destroyed at least 196 business establishments between March 26, 2015, and February 17, 2016. The Chamber of Commerce provided Human Rights Watch with a list of 59 specific factories, warehouses, and other civilian economic structures hit by coalition airstrikes, along with the dates they were struck, and their locations. Other than the sites discussed in this report, Human Rights Watch was not able to corroborate this information or determine which of these sites were being used for military purposes and thus were legitimate military targets. The Chamber did not report on Houthi or allied forces’ alleged use of economic sites for military purposes.

Even before the Saudi-led air campaign, Yemen was a country in which many people survived on the slimmest of margins. Since the campaign started Yemeni civilians have suffered both as a direct result of the armed conflict, and from the coalition blockade and obstacles to the delivery of humanitarian assistance. According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), one year after the armed conflict escalated across Yemen, an estimated 21.2 million people -- some 82 percent of the total population – required some form of humanitarian assistance.

The added impact of attacks against civilian economic structures on the population is not clear. However, since the Saudi-led aerial campaign began, food, medicines, and other consumer staples have grown scarcer and dramatically increased in price. Families regularly told Human Rights Watch that the increased price of food, transport, and medicine made it difficult or impossible for them to afford basic needs. Workers whose workplaces came under attack lost their incomes, and told Human Rights Watch they struggled to make ends after their workplaces laid off employees or shut down, and as commodity prices climbed.

Parties to the Yemen conflict declared a cessation of hostilities on April 10 and began peace talks in Kuwait later that month. Though the level of violence in the country diminished after the ceasefire formally went into effect on April 11, both airstrikes and fighting on the ground have continued. Negotiations to end the conflict continue; arriving in Kuwait on June 26, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon warned that “the economy is in precarious condition,” pointing to “an alarming scarcity of basic food items.”

Any peace agreement should address accountability for violations of the laws of war by all parties to the conflict. This includes the members of the coalition, consisting of five members of the Gulf Cooperation Council—Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates—as well as Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, and Sudan. Houthi forces and their allies are also parties to the conflict, notably military forces loyal to former president Ali Abdullah Saleh, who was compelled to leave office in February 2012. Other forces involved in the conflict include pro-coalition militias in southern Yemen and Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP).

The United States has been a party to the conflict since the first months of the fighting. In June 2015, a US military spokesperson stated that the United States was helping the coalition with“intelligence support and intelligence sharing, targeting assistance, advisory support, and logistical support, to include aerial refueling with up to two tanker sorties a day.” In May 2016, the US acknowledged that it had deployed troops in Yemen in a combat role against AQAP.

The United Kingdom is “providing technical support, precision-guided weapons and exchanging information with the Saudi Arabian armed forces,” according to the UK Ministry of Defence.

Saudi Arabia has successfully lobbied the UN Human Rights Council to prevent it from creating an independent, international investigative mechanism. Human Rights Watch is not aware of any credible investigations by Saudi Arabia or other coalition members into these or other allegedly unlawful strikes, nor of any compensation provided to victims. In May 2016 the US Ambassador to the UN, Samantha Power, informed Human Rights Watch that the Saudis launched an investigation into an attack on the Mastaba produce market in northern Yemen that killed at least 97 civilians. However, the Saudi government has not announced any findings to date.

On May 27, the Saudi government issued a statement asserting that coalition forces “have fully complied with international humanitarian law and international human rights law in their military operations.” The statement noted that legal advisors sat on planning and targeting teams, and that forces deployed “front line observers to ensure there are no civilians in the vicinity of targets.” It further noted that “where claims about targeting of civilians, civilian facilities or NGO [nongovernmental organization] operations are made, investigations are conducted by a separate and distinct investigation team established at Coalition Air Force [headquarters].”

Human Rights Watch has encountered no evidence that would support these Saudi claims and the Saudi government has provided no public information that would verify them.

Neither the United States nor the United Kingdom are known to have conducted investigations into any alleged unlawful strikes. Public statements suggest that both the United States and the United Kingdom have largely deferred to the Saudis, saying that the Saudis are investigating. The UK government has said that in some cases it provided information to assist Saudi investigations, although it has been unwilling to say how this process of information-sharing works and what has resulted from it.

Saudi Arabia and other parties to the conflict in Yemen, including the United States, should ensure compliance with the laws of war, including prohibitions on attacks against civilian objects. States should meet their obligations to investigate alleged war crimes, prosecute those responsible, and provide prompt and adequate compensation to the civilians harmed or their families. The failure of any party thus far to credibly investigate alleged violations demonstrates the need for an independent international investigation.

Foreign governments have continued to sell weapons to Saudi Arabia after the start of the aerial campaign, despite growing evidence that the coalition has used these weapons in unlawful airstrikes. All countries selling arms to Saudi Arabia including the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and Canada, should suspend weapons sales until it not only curtails its unlawful airstrikes in Yemen but also credibly investigates alleged violations.

Saudi Arabia has committed gross and systematic violations of human rights during its time as a Council member, and has failed to conduct credible, impartial and transparent investigations into possible war crimes. It has used its position on the Council to shield itself from accountability for its violations in Yemen. The UN General Assembly should suspend the membership rights of Saudi Arabia in the UN Human Rights Council.

Recommendations

To Saudi Arabia and other coalition members

- Abide by the laws of war, including the prohibitions on attacks that target civilians and civilian objects, that do not discriminate between civilians and military objectives, and that cause civilian loss disproportionate to the expected military benefit.

- Take all feasible precautions to minimize harm to civilian objects, including making advance effective warnings of attacks when possible.

- Consistent with the prohibition on indiscriminate attacks, end the use of heavy explosive weapons with wide area effect in populated areas.

- Conduct transparent and impartial investigations into credible allegations of laws-of-war violations, including the incidents detailed in this report.

- Institute a policy of conducting investigations into airstrikes in which there were high numbers of civilian casualties even where no evidence suggests violations of the laws of war.

- Make public information on the intended military targets of airstrikes that resulted in civilian casualties and make public all military actors involved in such strikes.

- Make public the findings of investigations and include recommendations for disciplinary measures or criminal prosecutions where violations are found.

- Provide prompt and appropriate compensation to civilians and their families for deaths, injuries, and property damage resulting from wrongful strikes. Consider providing “condolence” payments to civilians suffering harm from airstrikes without regard to wrongdoing.

To President Hadi’s Government

- Urge that the coalition provides detailed information about intended military targets of airstrikes in which civilians died or civilian property was destroyed. Make that information publicly available and press for compensation where there is a finding of wrongdoing.

To Houthi and allied forces

- Abide by the laws of war, including by taking all feasible steps to minimize the risks to populations under their control.

- Avoid placing military objectives in densely populated areas and take steps to remove civilians from areas under attack.

To the United States

- Conduct investigations into any airstrikes for which there is credible evidence that the laws of war may have been violated and that the United States may have been a direct participant, including by refueling participating aircraft, providing targeting information and intelligence, or other direct support.

- Publicly clarify the US role in the armed conflict, including what steps the US has taken to minimize civilian casualties in air operations and to investigate alleged violations of the laws of war.

To the United States, United Kingdom, and other coalition supporters

- All coalition supporters should urge Saudi Arabia and other coalition members to implement the recommendations listed above.

- Urge Saudi Arabia and other coalition members to agree to an independent, international investigation into alleged violations by all parties to the conflict in Yemen.

- Countries whose participation in the fighting makes them a party to the conflict, should abide by the laws of war, including by conducting investigations into any airstrikes for which there is credible evidence of laws-of-war violations and the country was a direct participant.

To the United States, United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, Canada, and other countries selling weapons to Saudi Arabia

- Suspend all weapon sales to Saudi Arabia until it curtails its unlawful airstrikes in Yemen, credibly investigates alleged violations, and holds those responsible to account.

- Urge Saudi Arabia and other coalition members to implement the above recommendations.

- In the absence of immediate coalition action to conduct meaningful investigations, support the establishment by the UN Human Rights Council (see below) of an independent international investigation into alleged unlawful strikes.

To UN Security Council member states

- Request a public briefing from the UN high commissioner for human rights on the current human rights situation in Yemen.

- Remind all parties to the conflict in Yemen that anyone responsible for “planning, directing, or committing acts that violate applicable international human rights law or international humanitarian law, or acts that constitute human rights abuses,” as well as those responsible for obstructing the delivery of humanitarian assistance to Yemen, are potentially subject to travel bans and asset freezes under Resolution 2140.

- Encourage the UN Panel of Experts established under Resolution 2140 to gather evidence on individuals responsible for violations of applicable international human rights and humanitarian law or obstructing humanitarian aid, including chains of command and control within the Saudi-led coalition and to share the information with the 2140 Sanctions Committee.

To Member States of the UN General Assembly

- Immediately suspend the membership rights of Saudi Arabia in the UN Human Rights Council for its commission of “gross and systematic” violations of international law in Yemen.

To the UN Human Rights Council

- Hold a special session to discuss the human rights situation in Yemen if the Saudi Arabia-led coalition does not address alleged violations and the failure to investigate abuses, or if the humanitarian situation in Yemen fails to improve.

- Supplement the national investigative mechanism by creating an independent, international investigative mechanism to investigate alleged violations of the laws of war by all parties to the conflict.

Methodology

This report is based on Human Rights Watch field research in the Yemeni capital, Sanaa, and the governorate of Hodaida, in March 2016. Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed 37 people who had witnessed airstrikes on civilian economic structures or its immediate aftermath, carried out by the Saudi Arabia-led coalition. In addition, the report includes details of incidents of airstrikes on economic structures previously investigated by Human Rights Watch and included in earlier publications.

The report describes 17 coalition airstrikes on 13 economic structures in which coalition forces destroyed or extensively damaged civilian objects in apparent violation of international humanitarian law, or the laws of war. Researchers visited two sites of airstrikes which have been excluded from this report – one because it was in close proximity to a military target, the other because the owner of the facility that was struck, a factory, did not wish it to be named.

Interviews took place at the sites of the airstrikes, or in a few cases, by telephone. Human Rights Watch researchers conducted most of the interviews in Arabic, but several were in English. All participants gave oral consent to be interviewed; participants were informed of the purpose of the interview and the way in which their information would be documented and reported, and that they could stop the interview at any time or decline to answer specific questions posed. No one received any remuneration for giving an interview.

Human Rights Watch selected airstrike sites for investigation by considering sites the coalition had attacked most recently, the extent of the damage reportedly caused, and a security assessment of whether the location could be safely reached and visited. Human Rights Watch did not share the locations with the Houthi authorities, nor did any Houthi representative accompany researchers on their investigations.

On May 16, Human Rights Watch wrote to the Saudi government to share its findings and to seek information on intended targets of 10 of the airstrikes that we had investigated. At the time of writing, Human Rights Watch had not received a response. Future responses to this report from the Saudi government or other coalition members will be posted on the Yemen page of the Human Rights Watch website: www.hrw.org.

I. Background

Economic and humanitarian impacts of armed conflict

With the beginning of the bombing campaign, the Saudi-led coalition imposed an aerial and naval blockade, which limited commercial shipments and humanitarian aid to Yemen. About 90 percent of Yemen’s basic food intake before the war came from imports.[1] By June 2016, more than one year after the armed conflict escalated across Yemen, the UN Office of for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs estimated that 21.2 million people -- some 82 percent of the total population – required some form of humanitarian assistance. This figure included 14.4 million people unable to meet their food needs (of whom 7.6 million are severely food insecure), 19.4 million who lack clean water and sanitation (of whom 9.8 million lost access to water due to conflict), and 14.1 million without adequate health care.[2] In particular, the blockade and accompanying inspection of all shipments to Yemen depleted the stocks of fuel, food, and drugs available in the local markets.[3] As of May 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that the medicine coming into Yemen only met 30 percent of needs.[4] In June, UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon warned of an “alarming scarcity of basic food items,” and that Yemen’s “economy [was] in a precarious condition.”[5]

On February 12, 2016, the UN secretary-general instituted the UN Verification and Inspection Mechanism, a process intended to expedite commercial imports of essential goods including food, medicine, and fuel.[6] In March 2016 Stephen O’Brian, Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs, at the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), reported to the UN Security Council that “in recent months there has been a significant increase in delivery of fuel and other life-saving imports through Yemeni ports,” and called on all parties to “ensure the protection of civilian infrastructure.”[7]

Though the naval blockade contributed most dramatically to Yemen’s economic crisis, attacks on factories, warehouses, power plants, and other economic sites also contributed to scarcity of goods. The Sanaa Chamber of Commerce and Industry reported that coalition airstrikes damaged or destroyed at least 196 business establishments between March 26, 2015, when aerial attacks commenced, and February 17, 2016.[8] The Chamber of Commerce provided Human Rights Watch with a list of 59 specific factories, warehouses, and other economic structures hit by coalition airstrikes between the beginning of the war and February 1, 2016, along with the dates they were struck and their locations.[9] It is not possible to determine conclusively from the list alone whether specific structures hit were civilian or military, were being used for military purposes at the time, or were otherwise military objectives subject to attack. The Chamber of Commerce has not reported on alleged violations of the laws of war by Houthi-affiliated forces.

Attacks on economic sites particularly impacted civilians, as food, medicines, and other consumer staples grew scarcer and dramatically increased in price. Most of the facilities attacked stopped production, and others reduced their capacity significantly. Other attacks destroyed stores of food or medicine. Families regularly told Human Rights Watch that the increased price of food, transport, medicine, and fuel made it difficult or impossible for them to afford basic necessities. After attacks on economic sites, companies suspended workers’ wages indefinitely or terminated their employment, cutting off their source of income and leaving them unable to afford inflated wartime prices.

Background to the conflict

In September 2014, Ansar Allah, commonly known as the Houthis, a Zaidi Shia group from northern Yemen, seized control of Yemen’s capital, Sanaa.[10] They were backed by units of Yemen’s army that remained loyal to former president Ali Abdullah Saleh, who had stepped down in 2011.[11] In January 2015, Yemeni President Abdu Rabu Mansour Hadi and his cabinet departed Sanaa and subsequently relocated to Saudi Arabia.[12]

In March, Houthi forces and their allies advanced southward, threatening to take the port city of Aden and other areas. On March 26, 2015, a Saudi Arabia-led coalition of Arab states began aerial attacks against Houthi forces in Sanaa and other locations. During the past year’s fighting, coalition forces, Houthi forces, and other armed groups aligned with either the coalition or the Houthis, have all been implicated in serious violations of the laws of war.

The United Nations and nongovernmental organizations have investigated and reported on numerous unlawful coalition airstrikes that killed and injured civilians, and destroyed or damaged civilian buildings and other structures where there was no evident military objective. According to the UN, 60 percent of the more than 3,200 civilian deaths since the coalition began its military campaign have been from coalition airstrikes.[13] Human Rights Watch has documented 43 airstrikes, some of which may amount to war crimes, that have killed more than 670 civilians, as well as 16 attacks involving internationally banned cluster munitions. In a report made public on January 26, 2016, the UN Panel of Experts on Yemen established under UN Security Council Resolution 2140 (2013) “documented 119 coalition sorties relating to violations” of the laws of war.[14]

Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International also documented the coalition’s use of seven types of cluster munitions in Yemen in 2015 and 2016.[15] This includes the use of CBU-105 Sensor Fuzed Weapons against a cement factory in the Amran governorate in February 2016.[16] Cluster munitions are indiscriminate and pose long-term dangers to civilians. They are prohibited by a 2008 treaty adopted by 119 countries, though not Saudi Arabia or Yemen.[17]

Parties to the Conflict

The Saudi Arabia-led coalition comprises five members of the Gulf Cooperation Council—Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates—as well as Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, and Sudan.[18]

According to the Saudi foreign minister, Adel al-Jubeir, as well as a statement issued by the coalition on May 27, 2016, the coalition launched its military operations at the request of President Hadi, whom the coalition forces continue to recognize as Yemen’s head of state.[19] At least one member of Hadi’s cabinet who is in exile in Riyadh is a member of the committee that selects strike sites, according to several diplomats who spoke with him about his position.[20]

The United States, though not a member of the coalition, is also a party to the conflict. In June 2015, a US Defense Department spokesman stated that the United States was helping the coalition with“intelligence support and intelligence sharing, targeting assistance, advisory support, and logistical support, to include aerial refueling with up to two tanker sorties a day.”[21] In November 2015, Lt. Gen. Charles Brown, commander of the US Air Force Central Command, stated that the military had a small detachment of personnel located in the Saudi Arabian center planning airstrikes to help coordinate activities.[22] US participation in specific military operations, such as bombing raids, means that the United States has been a party to the conflict since early on in the fighting and that US forces may be jointly responsible for laws-of-war violations by coalition forces.

In April 2016 a spokesman for the US Central Command, Col. Patrick Ryder,saidthat “the decisions on the conduct of operations to include the selections and final vettings of targets” were made by the Saudis.[23] He expressed confidence that the information and support the United States provided was “the best option for military success consistent with international norms andmitigating civilian casualties.” In May 2016 the United States acknowledged having ground troops in Yemen engaged in combat operations led by the Yemeni military and United Arab Emirates in and around the port city of Mukalla. Under international law, as a party to the conflict the United States is obligated to carry out or assist in investigations where there are credible allegations that its forces may have participated in war crimes and hold those responsible to account.[24]

The United States also approved the sales of more than $20 billion worth of military equipment to Saudi Arabia in 2015 alone. In July 2015, the US Defense Department approved a number of weapons sales to Saudi Arabia, including a US$5.4 billion deal for 600 Patriot Missiles and a $500 million deal for more than a million rounds of ammunition, hand grenades, and other items, for the Saudi army.[25] According to the US Congressional review, between May and September, the United States sold $7.8 billion worth of weapons to the Saudis.[26] In October, the US government approved the sale to Saudi Arabia of up to four Lockheed Littoral Combat Ships for $11.25 billion.[27] And in November, the United States signed an arms deal with Saudi Arabia worth $1.29 billion for more than 10,000 advanced air-to-surface munitions including laser-guided bombs, “bunker buster” bombs, and MK84 general purpose bombs.[28] The coalition used both laser-guided bombs and MK84 bombs in attacks described in this report.

In late May 2016, the United States suspended cluster munition transfers to Saudi Arabia.[29]

The United Kingdom has supported the coalition. According to the UK Ministry of Defence, in response to a House of Lords question on July 14, 2015, the United Kingdom is “providing technical support, precision-guided weapons and exchanging information with the Saudi Arabian armed forces through pre-existing arrangements.”[30] The weapons include 500-pound Paveway IV bombs, used by coalition Tornado and Typhoon aircraft.[31] The ministry confirmed on June 6, 2016 that Saudi Arabia has used Tornado and Typhoon aircraft purchased from the United Kingdom in combat operations in Yemen.[32] Since the war began, senior British military officers have provided targeting training for Saudi forces.[33] According to the London-based Campaign Against Arms Trade, the UK government has also approved £2.8 billion in military sales to Saudi Arabia since they entered the conflict in Yemen.[34] Weapons approved include 500-pound Paveway IV bombs. The coalition used it in an attack described in this report.

France is also providingjets, military transport aircraft, aerial refueling tanker aircraft, helicopters, amphibious assault ships, military patrol boats, light armored vehicles, and logistical support to some member states of the coalition.[35]

Investigations and Accountability for Indiscriminate Airstrikes

In apparent response to increasing reports of alleged laws-of-war violations by coalition forces and an upcoming UN Human Rights Council session, Yemen’s President Hadi on September 7, 2015 established a national commission to investigate violations of human rights and the laws of war.[36] During the ensuing UN Human Rights Council session in Geneva, Saudi Arabia and other Arab countries effectively blocked an effort led by the Netherlands to create an international investigative mechanism. The national commission has yet to take any tangible steps to conduct investigations, nor has it revealed any working methods or plans, several people close to the commission told Human Rights Watch.

On January 31, 2016, the coalition announced the creation of a committee to promote the coalition’s compliance with the laws of war.[37] However, the military spokesman for the coalition specified that the objective of the committee was not to carry out investigations into alleged violations. A statement from the Saudi embassy in Washington, DC, specified that the committee would assess the coalition's rules of engagement involving civilians and would offer "conclusions and recommendations to better respect international and humanitarian law."[38]

On July 9, 2015, the European Parliament adopted a resolution condemning Saudi Arabia-led coalition airstrikes in Yemen, including the use of cluster bombs.[39] In light of the coalition’s conduct of hostilities, on February 25, 2016, the European parliament passed a resolution calling on the European Union’s high representative for foreign affairs and security policy, Federica Mogherini, “to launch an initiative aimed at imposing an EU arms embargo against Saudi Arabia.” On March 15, the Dutch parliamentvotedto impose the embargo and ban all arms exports to Saudi Arabia.[40]

On April 13 two US senators introducedlegislation to temporarily block US air-to-surface munition sales to Saudi Arabia until the State Department certifies that the Saudi military is taking all available steps to protect civilians.[41] On April 20 the Swiss government blocked military exports worth US$19.5 million to several Middle Eastern countries that it suspected could eventually be used in Yemen.[42]

Although the level of the conflict has de-escalated following the ceasefire announced on April 10, both ground fighting and airstrikes continue in parts of Yemen.[43] UN-backed peace talks began in Kuwait on April 21.[44] Participants at the peace talks include representatives from President Hadi’s Yemeni government, the Houthis, and the pro-Houthi party of former president Ali Abdullah Saleh.

On May 27 the Saudi government issued a statement asserting that coalition forces “have fully complied with international humanitarian law and international human rights law in their military operations.” The statement noted that legal advisors sat on planning and targeting teams and that forces deployed “front line observers to ensure there are no civilians in the vicinity of targets.” The statement noted that “wherever possible, coalition forces issue advance warnings before attacking military targets to ensure civilians are not in their vicinity.”

On the issue of investigating alleged violations, the coalition stated that “where claims about targeting of civilians, civilian facilities or NGO operations are made, investigations are conducted by a separate and distinct investigation team established at Coalition Air Force [headquarters].” Once investigations are complete, the results are declared and compensation for victims is pledged, the coalition noted. (The full statement is published as an appendix to this report.) To date Human Rights Watch has not seen published results of any coalition investigations nor any evidence of compensation for victims.

On June 2, 2016 the Office of the UN Secretary-General published its annual report identifying armed forces and groups responsible for grave violations against children. For the first time, the Secretary-General’s report included the Saudi coalition in its “list of shame,” noting that coalition forces were responsible for most of the nearly 2,000 children were killed or maimed during the war. However on June 6, following protests by the Saudi government, the UN Secretary-General’s office announced it was removing from its “list of shame” the Saudi-led coalition, “pending the conclusions of [a] joint review” of the cases included in the report’s text.[45]

II. Applicable International Humanitarian Law

International humanitarian law, also known as the laws of war, applies to the armed conflict between the Saudi Arabia-led coalition and the Houthis. It also applies to the various non-state armed groups allied to the coalition or to the Houthis, as well as to other states that are parties to the conflict, including the United States. Because the conflict involves states against non-state armed groups, it is considered a non-international armed conflict. Applicable law involves article 3 common to the four Geneva Conventions of 1949, the Second Additional Protocol to the Geneva Conventions (Protocol II), and customary laws of war.[46]

This report examines attacks on civilian objects, specifically economic structures, by coalition airstrikes. A fundamental principle of the laws of war is the distinction between civilians and combatants, and between civilian objects and military objectives. Attacks may only be directed at combatants and military objectives. [47]

The laws of war prohibit deliberate, indiscriminate, or disproportionate attacks against civilians and civilian objects. Civilians have immunity from attack, except for such time that they are directly participating in the hostilities. Directly participating in hostilities would include, for instance, a civilian carrying ammunition to a fighter during a battle. However, civilians working in an ammunition factory would not be considered directly participating in hostilities, even though the factory itself would be subject to attack.[48]

Civilian objects include homes, markets, factories, farms, warehouses, and businesses, unless they are a military objective. A military objective is anything that provides enemy forces a definite military advantage in the circumstances prevailing at the time.[49] Combatants, weapons and ammunition are military objectives. Even though a residential home is presumed to be a civilian object, its use by enemy fighters for deployment or to store weaponry, will render it a military objective and subject to attack. Factories that produce weapons or materiel for enemy forces are military objectives and subject to attack, even if the workers employed are civilians.

Attacks are indiscriminate when they are not directed at a specific military objective or when they employ a method or means of warfare (such as cluster munitions) that cannot be directed at a military objective or whose effects cannot be limited.[50]

A disproportionate attack is one in which the expected incidental loss of civilian life and damage to civilian objects exceeds the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated.[51]

In the conduct of military operations, parties to a conflict must take constant care to spare the civilian population and civilian objects from the effects of hostilities.[52] Parties are required to take precautionary measures with a view to minimizing harm to civilians and civilian objects.[53]

Before conducting an attack, a party must do everything feasible to verify that the persons or objects to be attacked are military objectives and not civilians or civilian objects.[54] According to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) the requirement to take all “feasible” precautions means, among other things, that those conducting an attack are required to take the steps needed to identify the target as a legitimate military objective “in good time to spare the population as far as possible.”[55]

Attacking forces also must take all feasible precautions in the choice of means and methods of warfare to minimize loss of civilian life and property.[56] The laws of war do not prohibit fighting in urban areas, although the presence of civilians places greater obligations on warring parties to take steps to minimize harm to civilians. All forces must avoid locating military objectives within or near densely populated areas and endeavor to remove civilians from the vicinity of military objectives.[57]

Human Rights Watch opposes the use of explosive weapons with wide area effect in populated areas due to the inevitable civilian harm caused.

With respect to individual responsibility, serious violations of the laws of war committed with criminal intent are war crimes. Criminal intent has been defined as violations committed deliberately or recklessly.[58] Individuals may also be held criminally liable for attempting to commit a war crime, as well as assisting in, facilitating, aiding, or abetting a war crime.

Responsibility may also fall on persons planning or instigating the commission of a war crime.[59] Commanders and civilian leaders may be prosecuted for war crimes as a matter of command responsibility when they knew or should have known about the commission of war crimes and took insufficient measures to prevent them or punish those responsible.[60]

Under the laws of war, governments have a duty to investigate war crimes allegedly committed by members of their armed forces and other persons within their jurisdiction. Those found to be responsible should be prosecuted before courts that meet international fair trial standards or transferred to another jurisdiction to be fairly prosecuted.[61]

The laws of war also provide for a state to make full reparations, including directly to individuals, for the loss caused by violations of the laws of war.[62]

III. Cases of Unlawful Airstrikes on Civilian Economic Structures

Since the beginning of the military operations of the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen, Human Rights Watch has documented apparently unlawful airstrikes on 13 economic structures used for civilian purposes. These include six factories, three compounds that produced and stored commercial goods, an electrical station storage facility, a power plant, and the Sanaa Chamber of Commerce headquarters. These attacks killed 130 workers, security guards, or nearby residents of the facilities and injured 171 more. Altogether these 13 facilities employed over 2,500 people, many of whom lost their incomes or jobs due to the attacks. A few of the factories reopened following attacks, despite fears for workers’ safety, as managers say they need the revenue to continue paying salaries.

At least 10 of the attacks appeared to be unlawful, with no military target in the immediate vicinity, and may constitute war crimes. Four of them killed large numbers of civilians.

The strikes took place between March 31, 2015 and February 15, 2016. The coalition attacked some of the facilities more than once. Seven of the thirteen sites were struck in January or February 2016. Human Rights Watch identified weapons used at six of the sites, based on remnants of munitions found at the sites or, in one case, photographs provided by employees. The United States produced or supplied four types of munitions identified as having been used in the strikes. The United Kingdom produced or supplied two types, including a Paveway IV guided bomb produced in May 2015, after the start of the coalition’s aerial campaign.

Electricity Company Administration for Hodaida

Hodaida city, Hodaida governorate

Date of strike: October 10, 2015

Casualties: none

Munitions Identified: None

At about 10:30 p.m. on October 10, 2015 coalition aircraft bombed two storage hangars belonging to the Electricity Company Administration for Hodaida, the local government electric utility company, located in the north of Hodaida. Three bombs hit one hangar, which stored spare parts used to repair the electricity network in the city, and one hit an empty hangar in the compound, employees told Human Rights Watch. The airstrikes did not injure any workers. They caused extensive damage to the spare parts stored in the first hangar and destroyed part of its roof.

Khalil Muhammad Ali, 35, who works as an administrative employee for the facility, was outside the main gate of the hangar when the strikes hit. He said:

I didn’t hear any planes, just a bang. We waited for an hour before we went inside because we were scared. The second strike hit two minutes after the first on an empty hanger right next to the first one, then the third hit two minutes later on the first hanger, but left no crater because it hit the metal roof beam. We didn’t find any remnants. A fourth hit two minutes later in the same place on the roof.[63]

Human Rights Watch examined the site on March 29, 2016. Researchers found one crater in the concrete floor about three meters wide. A large broken metal roof beam hung down to the floor where employees said the third bomb hit. Researchers could not access the second locked, but reportedly empty, storage hanger where they said the second bomb hit, as employees said it belonged to a different government authority. Employees told Human Rights Watch that no military supplies were stored in the hangar targeted, and that no military targets or Houthi installations were located nearby. One employee told Human Rights Watch that a house where about 10 Houthi fighters slept at night was located on the residential street behind the Electricity Administration compound, about 100 meters from the site.

Under the laws of war electricity distribution facilities, like airports, are considered “dual-use objects” – civilian objects that also benefit an armed force. As such they can be military objectives, subject to attack. However, any attack on a dual-use object must be proportionate –the anticipated military gain of the attack must exceed expected loss of civilian life and property. Attacks on power plants that serve the civilian population are likely to cause disproportionate harm.

The house where Houthi fighters slept 100 meters away was a legitimate military target. The coalition should investigate the hangar bombing to determine if they unlawfully targeted the facility and whether forces took all feasible precautions to minimize civilian loss of life and property.

Coca-Cola Factory, Sanaa

Sanaa city, Sanaa governorate

Date of strike: December 12, 2015

Casualties: 5 injured

Munitions identified: US–supplied 1,000-lb MK-83 Paveway-series laser guided bomb

On December 12, 2015, starting at 8:25 p.m., coalition aircraft dropped three bombs on a Coca-Cola factory located off the Airport Road in northern Sanaa. The bombs hit the factory over several minutes, wounding five employees. They destroyed raw materials used to produce soft drinks, a generator, and both the glass and plastic bottling lines.

Issam Mohammad Abdu, the plant manager, told Human Rights Watch that about 20 workers from the sales and maintenance departments left the factory that evening to catch buses by the gate, departing only 10 minutes before the first bomb hit. “At the time of the strikes, there were at least 10 people in the back at the loading docks, working in logistics and loading,” he said. “When the first strike hit, they all went running out of the compound.”[64]

Ahmed Tahir Mabkhout, 43, a salesman for the company, was standing next to the factory’s generator when the airstrike hit.[65] He told Human Rights Watch:

I didn’t hear the first bomb, because the generator was very loud. But I saw the fire. When the second hit, I was by the [factory] exit, and when the third hit, I was already in the street. The second and third bombs landed inside the factory hanger.

Mabkhout was wounded by the first bomb:

I got metal fragments in both of my lower legs. I spent two months in the hospital, and have had to have three operations so far. I still need one more. One of the wounds to my right leg is still open, where they had to do a skin graft from my upper thigh.

Abdu, the plant manager, told Human Rights Watch that the factory employed 600 workers before the war, but had to lay off 270 of them after the bombing. He added that they planned to terminate the employment of 100 additional workers, since the factory remained closed and they had no revenue.

Human Rights Watch visited the factory on March 31, 2016. Factory employees showed Human Rights Watch munition remnants including bomb fragments. The fragments indicate that coalition aircraft attacked the factory using at least one 1,000-lb MK-83 Paveway-series laser guided bomb. Researchers observed two craters at the site, each about three meters wide and two meters deep. Employees explained that the third bomb hit a large pile of finished beverage products and left no crater. Broken bricks, fallen metal roof beams, and other building debris covered the site. Researchers found broken bottles and large amounts of spilled sugar in the area where workers said they previously stored raw materials.

All of the witnesses interviewed said that they did not know why the coalition had bombed the factory, and that it contained no military supplies, only materials for manufacturing soft drinks. The al-Dailami Air Force Base is located about 700 meters from the factory. According to factory employees, coalition forces have repeatedly struck the base since the coalition began their aerial bombardment in Yemen, including during the nine months before the factory was struck. Abdu, the plant manager, said, “[the coalition] have bombed it [the air force base] almost daily since the beginning of the war. So why would they suddenly make this mistake [hitting the factory], nine months into the war? And one bomb maybe, but three?”

The attack on the Coca-Cola factory was unlawful so long it was not being used for military purposes, such as to produce or store goods intended for military use. Human Rights Watch found no evidence that the factory produced anything other than beverages. The coalition should investigate the airstrike and, if found unlawful, compensate factory owners for their losses and workers for injuries they suffered.

Sanaa Chamber of Commerce

Sanaa city, Sanaa Governorate

Date of strike: January 5, 2016

Casualties: 1 injured

Munitions identified: Mk-82 500-lb bomb with a UK-manufactured Paveway laser guidance kit

On January 5, 2016, at about 1 a.m., a coalition aircraft dropped a bomb on the Chamber of Commerce office, located in the Hassaba neighborhood of Sanaa city. Two guards were in the building at the time of the attack, one of whom was injured. The strike destroyed the eastern wing of the three-story building.

Ali Muhammad Diab, 55, one of the security guards present, told Human Rights Watch that about 15 minutes before the office was hit, he heard a bomb hitting a residential neighborhood behind the building.[66] He later learned that it fell in the middle of a street, but failed to explode. At about 1 a.m., a second strike hit the roof of the Chamber of Commerce building, and he fled the compound. He said that since the strike, he has had hearing problems in his right ear.

Before the airstrike, the office employed 52 workers. Khalid Ali al-‘Olafi, acting head of the Chamber of Commerce, told Human Rights Watch that three large meeting rooms, the Chamber of Commerce’s records archive, and the legal and communications departments were completely destroyed in the strike.[67] After the bombing, the Chamber of Commerce stopped using the building, which remained filled with debris at the time of Human Rights Watch’s visit.

Human Rights Watch examined the site on March 24, 2016. Researchers found no evidence of military activity at the site. Employees of the Chamber of Commerce and the security guard told Human Rights Watch there was no Houthi military presence in the immediate area. The Ministry of Interior, also located in Hassaba, is located about 900 meters from the Chamber of Commerce.

A neighborhood resident told Human Rights Watch that the strike targeted a meeting of Houthi commanders that took place that evening at the Chamber of Commerce building. He said that one commander died in the attack. Human Rights Watch could not confirm his account with additional sources.

A Chamber of Commerce employee subsequently sent Human Rights Watch photographs of remnants he and other employees said were found at the site. Human Rights Watch identified the remnants photographed as parts of a Mk-82 500-lb bomb with a British-manufactured Paveway laser guidance kit.[68]

The attack on the Chamber of Commerce building was unlawful unless the compound was being used for military purposes. If the building was being used by Houthi military commanders at the time of the attack, it would have been a legitimate military target and the attack would have been lawful. Civil authorities would not be legitimate military targets unless they were directly involved in planning or participating in military operations. The coalition should provide information demonstrating that the attack was carried out against a lawful military objective.

Hodaida Warehouses

Hodaida-Sanaa Road, Hodaida governorate

Date of strike: January 6, 2016

Casualties: none

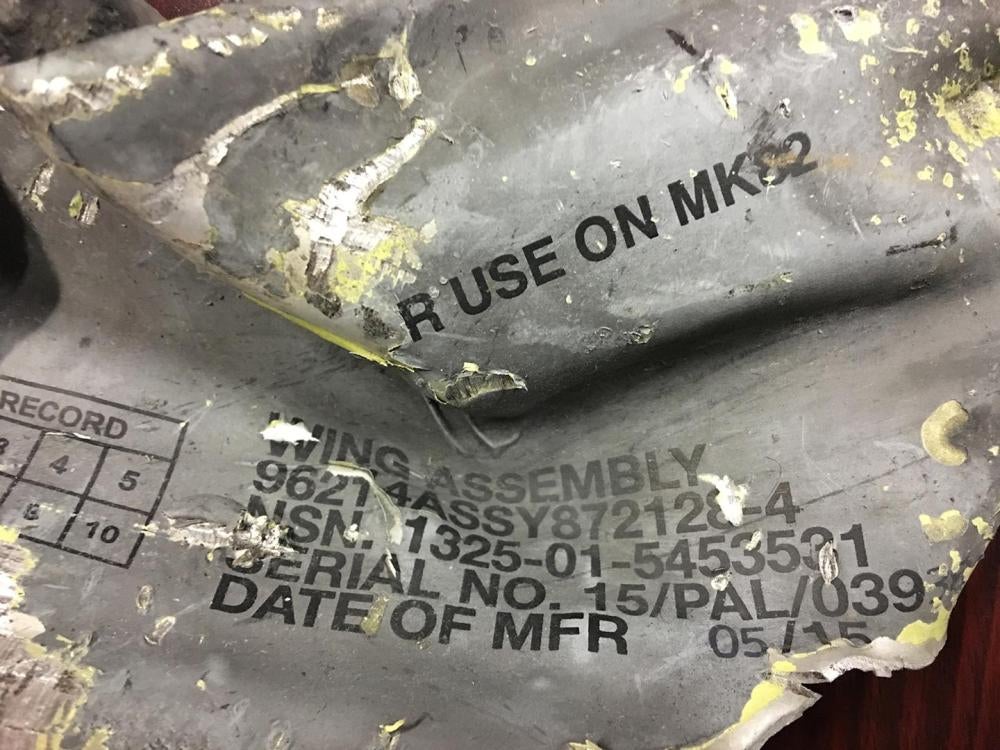

Munitions identified: UK-manufactured Paveway IV guided bomb, produced in May 2015

Starting at about 1:30 a.m. on January 6, 2016, two bombs hit two hangars within a compound of five storage hangars and production workshops located in an industrial area on the main road leading east out of the city of Hodaida, towards Sanaa. The airstrikes did not injure anyone. They damaged a hangar storing food products and a hangar housing a factory that produced metal building components.

The first strike hit a hangar containing food products including rice, sugar, canned tuna, and canned tomato paste. Human Rights Watch found rice and remnants of cans strewn across the warehouse floor. The second strike hit a warehouse containing car parts.

Muhammed Aswad, 60, a guard at the facility, said, “I heard a bang with the first strike, and then [I heard] planes flying before the second one. One of the cars in the yard burst into flames.”[69] Aswad told Human Rights Watch that four other men were in the yard at the time of the attack. They paid rent to use the yard to sell black-market diesel to passing cars and vans, he said. The men fled after the first strike.

Sultan Ahmad, a sales manager for the al-Moqbili company, which stored car parts at the facility, said an employee called him after the first strike and told him that the warehouse was burning. “I called Civil Defense and then went to the location,” he said. “I was outside when the second strike hit—I saw fragments everywhere.”[70] He said the two strikes hit about 15 minutes apart. Ahmad estimated that the strike resulted in damages of about 13.7 million Yemeni rials worth of goods (approximately US$54,700).

Human Rights Watch visited the site on March 29, 2016 and examined damage caused by the strikes. Employees showed researchers remnants of munitions they located at the site a week after the attack, which they stored in their offices. The remnants indicated that coalition forces used a Paveway IV guided bomb to strike the warehouses.The markings on the wing assembly indicate that Raytheon in the UK manufactured the bomb in May 2015, after the start of the war.

The attack on the warehouses appeared to be unlawful. Human Rights Watch found no evidence the facility was being used for military purposes, including to store weapons or materiel. One of three remaining hangars at the site stored school furniture, while the other two housed workshops producing zinc sheeting and metal fencing grates. An army camp was located on the Hodaida-Sanaa road, about 500 meters from the facility. No evidence suggested that the camp made use of any of the goods stored at the facility.

The coalition should investigate the airstrike and appropriately compensate the owners of the facility and materials stored there for their losses.

Bio Pharma Factory

Sanhan, Sanaa governorate

Date of strike: January 16, 2016

Casualties: None

Munitions identified: US-produced Paveway-series laser guidance kit

At about 2:15 p.m. on January 16, 2016, an airstrike hit the Bio Pharma Factory, located in Sanhan, a village about 16 kilometers southeast of Sanaa city. Former Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh, a key supporter of the Houthis in the current conflict, owns a house in Sanhan, his family’s ancestral village.

The four-story factory produced medical capsules, syrup, tablets, and injections. It employed more than 100 workers before the war. During the conflict, after supplies became scarce and prices increased, the factory reduced its workforce to 60 workers.[71] No workers were injured in the attack. The strike destroyed part of the roof of a factory building, several offices, a laboratory, and three vehicles.

On the afternoon of January 16, Yehia Hussein al-Aush, a 33-year-old guard at the factory, was in the small guardhouse at the entrance to the factory compound.[72] He said it was about an hour after the factory workers had finished their shift. He heard the roar of a plane overhead, and after about 10 minutes, the sound of the bomb whistling through the air. “[The bomb] hit the administrative building, where the laboratory and storehouse are,” al-Aush told Human Rights Watch. “I was disoriented and ran from my room.”

Al-Aush believed that the area had been under aerial surveillance. “The planes have always been watching us,” he said. “You could hear the sound of airplanes that survey the area, but other factories in the area have not been hit.”

Human Rights Watch examined the site on March 26, 2016. Muhammad Shewater, 63, the maintenance manager at the factory, told Human Rights Watch that the offices, laboratory, and the office of the factory director were destroyed in the strike.[73] At least three vehicles parked in the factory compound were also damaged or destroyed. At the time Human Rights Watch visited, the factory continued to operate in buildings not affected by the airstrike. Workers had stopped using the building damaged in the bombing.

Human Rights Watch also examined remnants found at the site and identified parts from the guidance kit for Paveway-series laser guided bomb. Markings on the fragments refer to ITT Enidine Inc., a New York company for hydraulic dampeners, indicating that a US-based company produced the guidance kit.

The Bio Pharma company owns nine factories in Yemen, one of which was the factory struck in Sanhan. According to Shewater, the company’s products represent about 5 percent of the drug market in the country.

Two workers told Human Rights Watch that there were no military targets in the immediate vicinity. “There’s no evidence to suggest that we are fighters or soldiers,” al-Aush said. “This is a civilian manufacturing area.” He and another worker mentioned that the “Sabra and Shatila” military camp is located about 10 kilometers to the south, while Jarban, a military storage location, is located about three kilometers away.

The attack on the Bio Pharma factory was unlawful unless the factory was being used for military purposes, including to produce goods for military use. Human Rights Watch found no evidence of military goods at the site nor that the factory was bring used for military purposes. Researchers observed the remnants of medicine bottles, pill packets, and laboratory equipment at the site. The coalition should investigate the airstrike and if they unlawfully attacked the facility, compensate the factory owner for damage.

Al-Aqil Industrial Compound

Sanaa city, Sanaa governorate

Date of strikes: September 16, 2015; January 19, 2016

Casualties: 2 dead, 29 injured

Munitions identified: MK-84 GP (general purpose) bomb, supplying country unknown

Coalition forces struck the al-Aqil Industrial Compound, which houses seven factories producing different products including plastic bags, food, clothing, and batteries, on two separate occasions since the beginning of their military operations in Yemen. In the first attack, at about 11 p.m. on September 16, 2015, an airstrike hit the plastic bag factory. The attack killed Muhammad al-Qadri, 26, a driver, and wounded three other workers.

Alajmateen Mujahid Ali Ghabish, 23, a security guard at the compound, said that the factories in the compound shut for three months following the September strike.

On January 19, at about 10:30 a.m., coalition forces struck a second factory in the compound that produced snack foods as well as a third that produced batteries. The attacks killed one worker and wounded 26 others.

Ghabish, the security guard, said that during the January 2016 strike:

I was in the administration [building]. We were doing our work, and we heard a very loud explosion. We went out to check what happened and we saw that [an airstrike hit] one of the factories. We found the workers running away. We tried to check if there were any [injured] workers left, and we heard the aircraft, so we retreated a little bit. Then we heard it again, I heard the aircraft and the sound of the [second] bomb because I was close.[After it hit,] I didn’t notice what happened. I saw the dust and stones, then they took me to the hospital directly.[74]

Muhammad Rajih, 26, an employee at the snack factory in the compound, said that he was also injured during the January strikes:

I was in the hangar at the time of the first strike; I felt the blow. Then 10 minutes later there was a second one. Thank God everyone had left by then.That first explosion wounded me in my face and leg. [The blast] threw us everywhere. I am still getting treatment [for these injures].[75]

Human Rights Watch examined the site on March 21, 2016. The first bomb left a wide, deep crater outside of the plastic bag factory, slightly damaging the building, and leaving plastic strewn across the yard. The second and third bombs blew through the roofs of the structures, and the second also left a deep crater. The third bomb was cushioned by products so did not dent the floor of the factory. Human Rights Watch found the remnants of the third bomb at the site and identified it as a MK-84 GP (general purpose) bomb.

Human Rights Watch established that al-Aqil industrial compound is located about 100 meters from the Maintenance Corps Camp, a military site for the maintenance of military vehicles and weapons. The walls of the two sites are adjacent. However, factory workers said they did not know whether it remained in use or not. Ghabish told Human Rights Watch that coalition aircraft had struck the camp at least 13 times since the beginning of the war.

The military maintenance site was a legitimate military target. However, the coalition should investigate the two attacks that struck the factory compound to determine if it was unlawfully targeted and whether all feasible precautions had been taken to minimize civilian loss of life and property. If they find the attack unlawful or carried out with insufficient precautions, the coalition should compensate workers and their families for injuries or deaths caused by the attack, as well as the factory owners for damage.

Al-Shihab Industrial Compound

Sanaa city, Sanaa governorate

Date of strikes: January 29 and January 30, 2016

Casualties: 1 dead, 3 injured

Munitions identified: none

At about 9 p.m. on January 29, 2016 an airstrike hit al-Shihab Industrial Complex, located in the northern part of Sanaa city. The bombs struck outside a storage hangar for tea and rice. A second strike hit just outside the factory compound. No one was injured in this attack. On January 30 beginning at about 2 p.m., four additional strikes hit the factory, wounding two guards and another employee and killing a third guard. These strikes hit the storage hangar for Nido fortified milk powder, the tea and rice storage hangar (for the second time), an office building that housed company records, and a hangar where the factory produced deodorant. In total, five strikes hit the factory over two days.

Abdullah Hamood Qaid al-Ali, 29, a guard at factory, told Human Rights Watch that he was at the factory for both sets of strikes. He said that on the evening of January 29, “I was at the gate when the first airstrike hit here. The fire truck came to put out the fire. The second airstrike hit after that, but it struck outside [the factory] and nothing happened.”[76]

He said that the next afternoon, “I was at the gate, stopping the people who wanted to come to loot things from the factory. I heard the sound of the bomb before the aircraft….We heard the aircraft sounds only after.” He added that the hangars hit contained a variety of food and other dry products and repeated that the factory stored no weapons. The nearest Houthi checkpoint was 1.5 kilometers away, he said.

Human Rights Watch examined the site on March 21, 2016 and found no evidence the factory had been used for military purposes. The airstrikes had completely destroyed the hangers by collapsing the structures and ripping off the zinc roofing of the attack on the Nido milk powder hangar left a deep crater in the floor. All heavy steel machinery was destroyed, as well as all of the finished products that were being stored. The remains of at least eight damaged or destroyed vehicles remained in the yard.

According to one of the security guards at the factory, the factory had employed about 150 workers, including 50 to 60 women. The Shihab company, which owns the compound, imports a variety of products to Yemen including Nido fortified milk powder, Quaker Oats, and Nestle products. According to Akil Omar Shihab, the chief executive officer of the Shihab company, the company provides 70 percent of the baby food supply in Yemen. The factory also produces consumer goods including facial tissue, tea, and deodorant.

Shihab said that the attacks particularly surprised him in light of a Houthi-led boycott campaign against products manufactured and imported by his company. He shared with Human Rights Watch an Arabic-language Facebook site advocating for a boycott against American and Israeli goods, which included Houthi logos and links to Houthi-affiliated media sources, as well as the commercial logos of Nestle and other companies.[77] The Shihab company imports Nestle products. The page had not been active for several months before the war began.

The attack on the compound was unlawful unless the factory was being used for military purposes, including to produce or store goods intended for military use. Human Rights Watch found no evidence of such goods when researchers visited.

Middle East Workshop for Sewing and Embroidery

Sanaa city, Sanaa governorate

Date of strike: February 14, 2016

Casualties: 1 dead, 3 injured

Munitions identified: none

At 1:06 a.m. on February 14, 2016 coalition aircraft dropped a bomb on the Middle East Workshop for Sewing and Embroidery, a small factory located in northeast Sanaa that produced and embroidered dresses. On one side of the factory were offices and on the other a storage facility storing electrical cables and plastic battery covers. One worker, a 16-year-old boy, was killed in the attack and three others wounded. Damage from the airstrike and a resulting fire left both the factory and the storage facility unusable.

The factory employed 24 workers, many of them internal migrants from the Rayma governorate, to the southwest of Sanaa. At the time of the strike, 17 workers remained in the building, as many of those from Rayma slept and ate in the building while in Sanaa. Abdullah Nasser al-Haddad, a 31-year-old engineer, said he was fixing the factory’s generator at the time of the strike. “People had to flee out the back door because the main door was completely blocked,” he said. “After 15 to 30 minutes, the place caught on fire. There was diesel stored here.”[78]

Raouf Mohammed al-Sayideh, 25, an embroidery worker at the factory who lives nearby, said:

We were home, opposite the factory... at 1:06 a.m. I heard the bang and came to the factory to look for the other [injured] workers. I tried to get them out and take the wounded to the hospital. One worker was stuck under the rubble. The manager had to call his phone so that we knew where he was to rescue him. The last person we rescued from inside [the wreckage] was the boy…. his legs got stuck between these two large blocks… his body was charred. That was after 30 minutes from the time of the airstrike. The fire [at the site] didn’t stop even though the fire truck was there; it took until 9 a.m. to put it out. I have worked here for eight years, there were no weapons or any fighters in here.[79]

Khalil Abdulla Talib al-Wasabi, a 16-year-old boy who worked embroidering garments at the factory, died from his injuries. The blast injured three other workers: Majid Youssef Ali al-Saideh, 28, whose ribs were broken and chest injured; Ahmad Abdul Aziz al-Khoulani, 20, whose head was injured; and Ali Hassen al-Wasabi, 40, whose jaw was injured.

Human Rights Watch examined the site on March 24, 2016. Though workers had cleared some of the larger debris from the site, the ground remained charred, and some parts were scattered with fabric pieces and other dressmaking materials. Human Rights Watch interviewed three witnesses to the strike or its immediate aftermath, as well as the owner of the plot of land, who lives in the area.

Abdullah Nasser al-Haddad, an engineer who was working on the factory’s generator for several days including the day of the strike, said that on February 11, three days before the airstrike, “I saw a light coming from the sky above the factory, either from a plane or a drone. I was scared and told the workers. They said, ‘Don’t worry, they won’t hit us.’”[80]

At the time of the airstrike, Haddad said, five Houthi fighters manned a checkpoint about 130 meters away from the factory. The checkpoint guards the former house of Raji Hunaiysh, a Ministry of Interior official and cousin of the factory’s land owner. Haddad said that long before the war Hunaiysh had left the home and rented it to the US Embassy, which is about 500 meters away from the factory. He added that coalition airstrikes had repeatedly struck a vocational institute about 170 meters away where about 30 Houthi fighters had lived since the conflict began. After the strike on the sewing factory, these fighters arrived on the scene to assist the wounded and take people the hospital.

The attack on the sewing workshop was unlawful unless it was being used for military purposes. Human Rights Watch found no evidence that the workshop was a military objective.

Amran Cement Factory

Amran governorate

Date of strikes: July 12, 2015; February 2, 2016; February 15, 2016

Casualties: 15 dead, 64 injured

Munitions identified: US-supplied CBU-105 Sensor Fuzed Weapons with BLU-108 canisters; US-supplied Mk-82 (500-lb general purpose bomb) with JDAM satellite guidance

Coalition aircraft struck the Amran Cement Factory in three separate attacks on July 12, 2015, February 3, 2016, and February 15, 2016.

On July 12, at about 12:45 p.m., at least five bombs hit different parts of the cement factory including the heating tower, the mixing area, and the water tank. The factory management had closed the factory after the coalition naval blockade made it difficult for them to source fuel and raw materials. Just a few days before the attack, they reopened the factory, and on July 11, workers started up the factory’s main production line. Coalition forces attacked the factory the next day, wounding 12 workers, including 7 with more serious injuries. After the attack, the factory gave most of the factory’s 1,500 workers leave, retaining only 350 workers to fulfill security, administrative, IT, and maintenance tasks.

On February 3, at about 5 p.m., another airstrike hit the main entrance of the factory, killing 15 civilians, including seven workers and two children, and wounding 49. Ramzi al-Faqih, 34, a general manager at the factory, told Human Rights Watch he was at the factory that afternoon completing some paperwork. At about 5 p.m., he was on the first floor consulting with three colleagues from the IT department. He said:

Suddenly dust filled the room and bricks and glass flew through the air…. I didn’t move for about three minutes. Then I looked down at the laptop I was holding, there was a large metal fragment that had pierced a hole right through the middle of it. My colleagues and I were able to make it into the lobby where we hid under the stairs for a few minutes, then we starting looking for a way out but it was dark all around us. There was rubble everywhere and the building had collapsed around us. [81]

Al-Faqih and his colleagues finally made it out but he and 48 other workers were wounded in the process. Outside the factory he saw four cars and at least two shops, a pharmacy, a café and a call center near the gate of the factory on fire.

Muhammad Ali Naif, 44, a local resident whose house is at the gate of the factory, said he was in his car at the time of the attack. He heard a bang and saw clouds of smoke. Believing that his family was in danger, he immediately drove in the direction of his home.

As he arrived, he saw a neighbor assisting six of his family members out of his damaged home. He rushed past them to look for his remaining son, Abdullah, 18, and his nephews Nawaf, 13, and Abdulrahim, 23, inside. He eventually found his son who was badly wounded, as well as Abdulrahim, who was dead, next to the neighboring call center. He said:

Later, when we put out the fire we found the body of Nawaf under one of the burned cars. My son Abdullah died in the hospital later that day, and my father, Ali, died from his injuries two days later. Our medical bills are over 2.5 million YER [US$11,600] and because we cannot afford to pay, the hospital has forced us to pawn off my car and the car of two of my relatives.[82]

On February 15 at about 4 a.m., another strike hit the area, landing on the factory’s cement crusher at the mouth of the factory’s quarry, at the foot of al-Raha Mountain. Muhammad Saleh Raiman, 40, one of the factory’s guards, had been guarding the area where the strike took place. He said he suffered only minor injuries because he moved away when he heard the sound of aircraft overhead. Two fellow guards, Nabil Ali Muhammad al-Raimani, 28, and Hatem Yahia Hatem, 40, were more seriously wounded.[83]

At about 5 p.m. the same day, coalition aircraft dropped cluster munitions on al-Raha mountain, including into the factory’s quarry and next to the cement crusher. The next morning, cement factory workers Kamal Hussein Qaid, 50, and Bandar Ahmed Daoud, 33, headed up to inspect damage at the cement factory’s quarry, about one kilometer from the main factory building and connected to al-Jumaima Mountain. On the way to the quarry they found and collected remnants of munitions that were lying in the middle of the road.[84]

When Human Rights Watch researchers visited the factory on March 25, 2016 they photographed these remnants, which were marked as the bomb casing of a CBU-105 Sensor Fuzed Weapon with a manufacture date of July 2012 and two expended BLU-108 canisters. Neither canister had its “skeet,” or submunition, attached. However, the cement factory workers told Human Rights Watch researchers that they also saw three more BLU-108 canisters with their “skeet” or submunitions still attached lying on the quarry tracks along with a parachute. The workers subsequently provided Human Rights Watch with photos that they took of the remnants lying in place where they landed, that showed the unexploded submunitions.

Researchers also found remnants of at least one Mk-82 (500-lb general purpose bomb) with JDAM satellite guidanceat the factory. Workers collected these remnants from previous strikes, a factory manager said.

Several staff members at the factory said that there are two to three small guards’ huts belonging to the factory on the road leading from the main factory building up to the quarry, about one kilometer from the factory. At some point after the beginning of the war, two or three Houthi fighters began occupying these huts, they said.

A military base is located on al-Jumaima mountain, at least two kilometers from the quarry. The facility previously housed the 310th Armored Brigade, which was led by Brig. Gen.

Hamid Al-Qushaibi, who was killed in fighting against the Houthis in 2014. Local residents told Human Rights Watch that since then, pro-Houthi forces have been stationed at the base, but did not have any details on numbers of forces or any types of weapons being housed there.

The attacks on the government-owned Amran cement factory’s main facility were unlawful unless the factory was being used to produce or store goods intended for military use. The Houthi fighters stationed at the quarry were lawful military targets –but attacking them had to be proportionate to expected civilian loss. The use of cluster munitions on the mountain, in close proximity to al-Darb village, constitutes an unlawful attack.

In May 2016, the factory’s management decided to reopen the facility so that they could pay the workers’ salaries. “We take this decision (despite [the] risk) after long suffering of factory manpower and their families, this is the only way to cover their incomes,” a factory manager wrote to Human Rights Watch. On May 4, the day they reopened, coalition aircraft flew overhead frightening the workers, who fled. The plant remained closed at the time of publication.

The coalition should investigate airstrikes on the Amran cement factory, cement crusher, and quarry and demonstrate that the factory was being for military purposes. If it was not the coalition should compensate families of civilians killed or injured in the attack.

IV. Previously Documented Attacks on Civilian Economic Structures

Yemany Dairy and Beverage factory

Hodaida-Sanaa Road, Hodaida governorate

Date of strike: March 31, 2015

Casualties: 31 dead, 11 injured

Munitions identified: none

Starting at about 11:10 p.m. on March 31, 2015, one or more coalition warplanes carried out four separate strikes that hit the Yemany Dairy and Beverage factory, located about 7 miles from Hodaida city.[85] The strikes killed at least 31 factory employees and wounded at least 11 more.

A factory worker told Human Rights Watch that after his shift ended at 11 p.m., he waited with colleagues at the factory gate for the employee bus. At 11:10 p.m., he heard the sound of aircraft, which he had seen bombing elsewhere in Hodaida earlier that evening. A few seconds later, he saw one of the factory warehouses explode. “We rushed to the doors of the nearest building full of staff, and held open the doors as people ran out,” he said.

A few minutes later he saw a second explosion in a part of the factory that housed packaging equipment, causing water boilers to explode. The ground shook beneath him, he said. He later discovered that the explosion also caused leaks in gas pipes used in the cooling process. The worker said he witnessed ambulance workers take several people who may have inhaled the gas fumes to a hospital.

He said that a few minutes later he saw a third explosion in another part of the factory, setting the building on fire. Three workers in the building died while trying to turn off the machines. There was a fourth explosion several minutes later in the same part of the factory.

Residents in the area told Human Rights Watch that the factory stood about 100 meters from a military air base controlled by Houthi forces. Military units loyal to former president Ali Abdullah Saleh were at another nearby military camp. Coalition warplanes attacked both the military air base and the neighboring military camp 11 days after the attack on the dairy factory, on April 11.

Coalition spokesperson Brig. Gen. Ahmed al-Assiri told Reuters the factory was struck by mortar fire and Katyusha rockets that he said came from the Houthis and their allies. "They were the ones who targeted the dairy factory," he said.[86] However, witness accounts indicate that aircraft dropped bombs on the factory. The Houthis and allied forces have not used aircraft in combat.

The attack on the dairy factory was unlawful so long it was not being used for military purposes, such as to produce or store goods intended for military use.

Those interviewed said that the factory produced only dairy products for the general public’s consumption.

Mokha Steam Power Plant

Mokha city, Taiz governorate

Date of strike: July 24, 2015

Casualties: 65 dead, 42 injured

Munitions identified: none

Starting between 9:30 and 10 p.m. on July 24, 2015, coalition airplanes repeatedly struck two residential compounds of the Mokha Steam Power Plant, which housed plant workers and their family members.[87]

Human Rights Watch visited the area of the attack a day-and-a-half after the attack. Workers and residents at the compounds told Human Rights Watch that one or more aircraft dropped nine bombs in separate sorties in intervals of a few minutes. All of the bombs appeared intended for the compounds and not another objective. Craters and building damage showed that six bombs had struck the plant’s main residential compound, which housed at least 200 families, according to the plant’s managers. One bomb had struck a separate compound for short-term workers about a kilometer north of the main compound, destroying the water tank for the compounds, and two bombs had struck the beach and a road intersection nearby.