Summary

Climate change is here with us. We cannot stop it. The only way is to see how to work around it.

-- Peter Ekai Lokoel, Deputy Governor Turkana, September 2014

Over the past century, the average annual temperature on earth has increased, the oceans have warmed, snow and ice caps have diminished, and sea levels have risen. Although evidence of climate change, and its causes, has been debated for more than two decades, there is now scientific consensus that climate change is occurring and is due to human activity.

Climate change is being felt in countries throughout the world, from low-lying countries such as Bangladesh and the Maldives, to temperate countries in the northern hemisphere, to countries in Africa’s arid and semi-arid Sahel. Climate scientists have attributed both the increasing frequency of specific extreme weather events (such as drought, flooding, and heat shocks) and the slow but steady change in long-term features of the environment (such as receding glaciers and melting permafrost) to rising temperatures caused predominantly by anthropogenic (i.e. human) sources. They predict that these, and other, observed climate changes will become more severe in coming years.

These changes in the climate are imposing an increasing burden on governments, especially in countries with limited resources, in their efforts to protect vulnerable populations and realize human rights. Changing precipitation patterns such as drought, and shorter but more intense rainfall, can have negative direct and indirect impacts on health and contribute to desertification and flooding, food insecurity, migration and increased conflict. Indigenous populations, poor and socially marginalized individuals, women, and people with disabilities, are often most affected.

The United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) has identified climate change as posing particular risks to the rights to life, food, water, and health. In the past decade, the UN Human Rights Council and other human rights bodies have as well, adopting several resolutions highlighting the consequences of climate change on the full realization of human rights. UN human rights experts have also repeatedly stressed that the response to climate change must respect, protect, promote and fulfil human rights.

One reason for the attention to the relationship between climate change and human rights is the recognition that climate change is having an uneven impact across the world. Countries with tropical or subtropical climates (such as those in Africa) are projected to experience the effects of climate change most intensely, and low-income countries are least able to prevent and prepare for the impact of climate change.

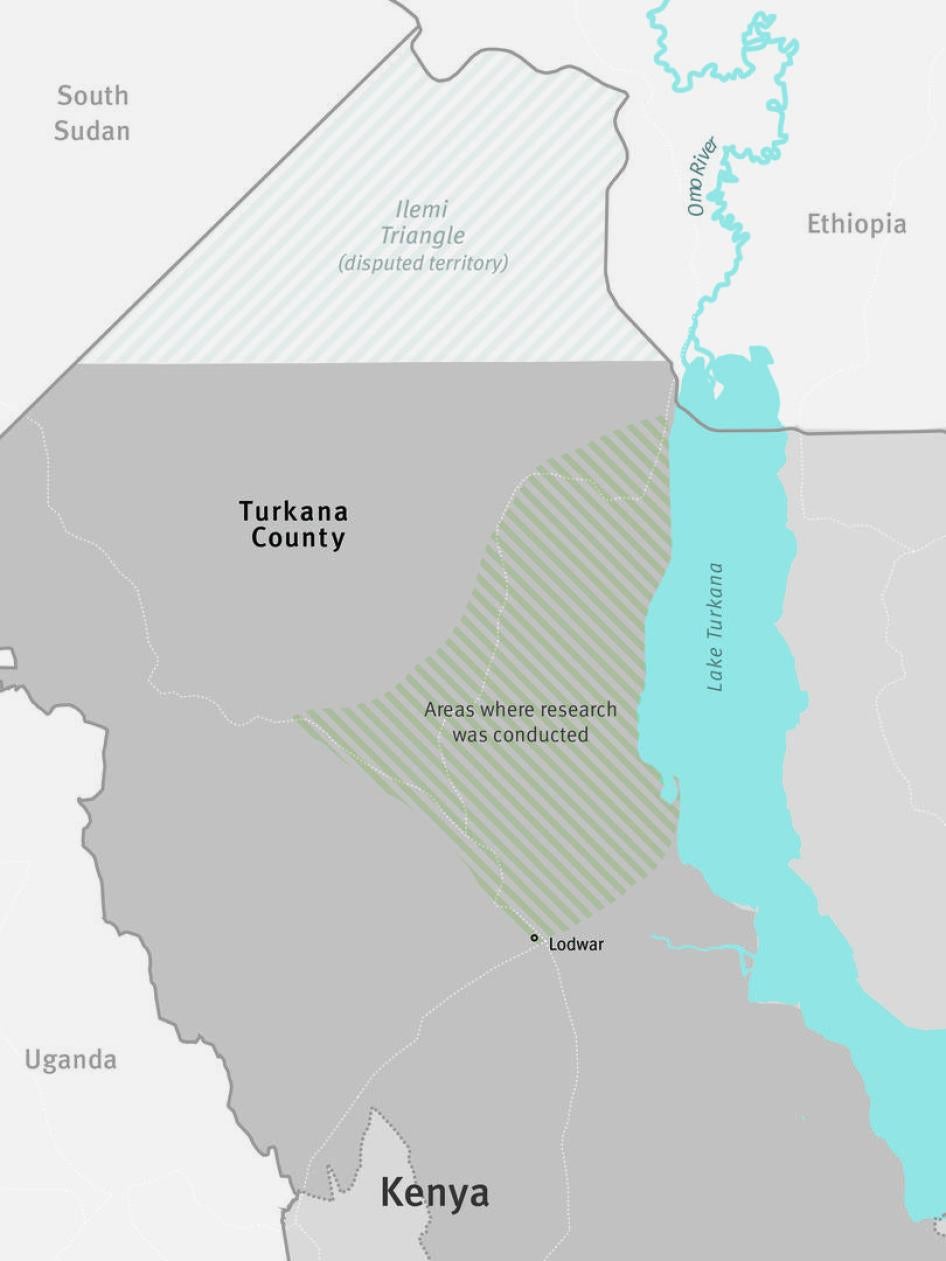

This report is based on research in Turkana County in northwestern Kenya. Turkana County borders South Sudan, Ethiopia and Uganda and is globally renowned as the cradle of mankind: in Turkana County and the Omo Valley in southern Ethiopia, archeologists have found the oldest ancestors to modern humans, dating back more than one million years ago. However, today, Turkana County is home to a rapidly growing population that is among the poorest in Kenya.

According to government records, the Turkana population has grown dramatically in the last two decades, increasing in the past few years from an estimated 855,393 people in 2009 to 1,256,152 people in 2015. The population is predominately indigenous Turkana people, and pastoral, relying on livestock herding. Some Turkana fish in the waters of Lake Turkana, while others reside in the county’s towns. Their traditional reliance on natural resources for food and livelihood, the historic marginalization of the region, and the lack of infrastructure make them especially vulnerable to any changes in the environment. Turkana County has had a long history of chronic malnutrition and some of the poorest health indicators in Kenya.

Over the past several decades, Kenyan government data show a clear trend in increasing average temperatures in the country as a whole and in Turkana County. While global mean temperatures are estimated to have increased by 0.8°C (1.5°F) in the past century, in Turkana County minimum and maximum air temperatures have increased by between 2 and 3°C (3.5 and 5.5°F) between 1967 and 2012. Rainfall patterns have also changed: the long rainy season has become shorter and dryer and the short rainy season has become longer and wetter, while overall annual rainfall remains at low levels.

Human Rights Watch conducted research in Turkana County between April 2014 and February 2015, interviewing 40 people, including pastoralists, fishers, health clinic staff, students, teachers, local civil society activists, and police officers. In addition, Human Rights Watch reviewed international, Kenyan and Turkana County laws, policies and development plans, including the Turkana County Development Plan and the Kenya National Climate Change Action Plan and met with Turkana County and Kenyan national government officials.

The report finds that climate change, in combination with existing political, environmental and economic development challenges in Turkana, has had an impact on the Turkana people’s ability to access food, water, health and security. Turkana County has long experienced periods of cyclical drought. However, increasing temperatures and shifting precipitation patterns, combined with population growth and threats to Lake Turkana from hydroelectric and irrigation projects in Ethiopia, present significant, long-term challenges for the Turkana County and Kenyan national governments.

Increased temperatures and unpredictable rainy seasons have placed increased pressure on water resources, resulting in less dry season grazing land, diminished livestock herds, and increased competition over grazing lands. Pastoralists told Human Rights Watch that prolonged and more frequent droughts have exacerbated already difficult access to potable water, making every day a struggle for survival. Women and girls often walk extremely long distances to dig for water in dry riverbeds. Many children become sick because their families are unable to provide them with sufficient food and clean water. In northern Turkana County, increased competition over grazing lands and water has heightened the likelihood of conflict and insecurity.

Industrial and agricultural development across Turkana’s northern border with Ethiopia also poses threats that could affect the realization of rights of the Turkana people. Over the past several years, Ethiopia has embarked on a massive plan for dams, water-intensive irrigated cotton and sugar plantations, and irrigation canals and other infrastructure in Ethiopia’s Omo River Basin, which provides 90 percent of the water in Lake Turkana. These developments are predicted to dramatically reduce the water supply of Lake Turkana: the planned irrigation projects alone could reduce by up to 50 percent the Omo River’s total flow. Some scientists predict that Lake Turkana, the largest desert lake in the world, could recede into two small pools.

Reduced water levels in Lake Turkana will have a devastating impact on the environment and people of Turkana County. Dramatic reductions in freshwater input from the Omo River into Lake Turkana will increase levels of salinity in the lake and raise water temperatures, decimating fish breeding areas and mature fish populations. Higher air temperatures will increase rates of evaporation, further increasing salinity while reducing biological productivity.

Kenya’s national and county governments have acknowledged the impact that climate change has had and will have on people’s lives. At the Climate Summit in New York in September 2014, Kenya’s President Uhuru Kenyatta urged countries to take decisive action on climate change, branding it a “serious global challenge that continues to affect Africa’s socio-economic development.” Kenya has also made several efforts towards developing a national policy addressing the effects of climate change, including the Kenya National Climate Change Response Strategy (2010) and the Kenya National Climate Change Action Plan (2013). Earlier this year, a climate change bill, introducing a Climate Change Council to ensure better coordination of the different climate change programs within the government, was passed in the National Assembly and is, at the time of writing, awaiting the adoption by the Senate and signature of the President.

However, Human Rights Watch research finds that much more needs to be done. The Turkana County and the Kenyan national government have been struggling to address the human rights consequences of climate change and other environmental developments for the most marginalized populations. At the national level, the adoption of the climate change bill, and the development and implementation of several climate change-related policies, have been delayed several times. Existing health and development policies largely fail to address the disproportionate impact that these changes are likely to have on Kenya’s most marginalized populations, including indigenous peoples, and the national government has not yet published a rights-based National Adaptation Plan (NAP) in accordance with Kenya’s commitments under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Kyoto Protocol. Kenya’s obligations under international human rights law further mandate that the government use available resources to progressively realize rights to food, security, water, and health in a non-discriminatory manner.

At the county level, the 2013 devolution agreement which led to the decentralization of many government functions has created many new responsibilities for the county government which gives it an expanded role in addressing the human rights effects of climate change and other environmental threats. Yet, the county government has done little to integrate climate change into development plans or develop adaptation strategies for vulnerable populations.

The government of Kenya is not alone in facing climate change and other environmental threats. Kenya should recognize that these changes will likely impede its ability to realize the human rights of many people. As a regional leader, Kenya should assess this impact, identify which individuals and communities are most vulnerable, and take steps to reduce this vulnerability and ensure that human rights standards are integrated into adaptation plans. Throughout this process, the government should ensure meaningful participation and access to relevant information for affected groups and refrain from investments and implementing actions that could undermine people’s rights.

Key Recommendations

To the Government of Kenya

- Ensure that the National Adaptation Plan under development is in accordance with Kenya’s obligations under the UNFCCC and international human rights law that includes plans on how to protect rights to food, security, water, and health. Ensure that this plan identifies how climate change will affect enjoyment of specific rights and includes implementation strategies to reduce the burden of those effects, particularly on indigenous people and marginalized groups, including women, children and persons with disabilities, who may disproportionately feel these impacts.

- Promote non-discrimination in all national policies, action plans, implementation strategies and other measures on climate change. Recommend to the government of Ethiopia to promptly undertake independent peer-reviewed impact assessments of the cumulative impacts of the Gibe III dam and irrigated commercial agriculture on the downstream communities of Lake Turkana and take steps to mitigate any serious harms identified.

To the Turkana County Government

- Consult with communities particularly affected by major environmental impact and climate change about alternative livelihood provisions prior to the implementation of climate change adaptation plans. Ensure full and meaningful participation of marginalized groups, including indigenous people, women and persons with disabilities.

- Integrate a climate change adaptation strategy in the Turkana County Integrated Development Plan that will allow the government to meet its obligation to progressively realize the rights to food, security, water, and health in a non-discriminatory manner and ensure its implementation.

To the Government of Ethiopia

- Promptly undertake independent and peer-reviewed assessments by qualified experts that evaluate the cumulative environmental and social impacts of development in the lower Omo valley including the Gibe III dam, the planned Gibe IV and Gibe V dams, and irrigated commercial agriculture on downstream communities in Turkana. The results should be publically available so downstream communities in Turkana County and the Turkana government can understand the impacts. Mitigation of serious harms identified should be carried out so as to respect the rights under international law of indigenous peoples and other affected communities.

To Donors to Kenya, including the World Bank and African Development Bank

- Undertake due diligence for proposed development and climate change projects to ensure that they are not contributing to or exacerbating human rights violations, either directly or by association. Only approve projects after assessing human rights risks, including of facilities associated with funding, such as power sources. Assess the cumulative impacts of all relevant developments; identify measures to avoid or mitigate risks of adverse impacts; and implement mechanisms that enable continual analysis of human rights impacts, including through third parties.

To all States Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

- Design and implement measures to facilitate adequate adaption to climate change, making sure that the measures taken do not violate the human rights of local communities.

- Recognize that human rights obligations apply in the context of climate change and include an explicit reference to the Parties’ obligations to respect, protect, and fulfill human rights in all climate actions into future climate change agreements.

- Establish safeguards and accountability processes to ensure that climate policies are designed, implemented and monitored in a manner that protects the rights of affected people and communities.

Methodology

This report is based on field research conducted by Human Rights Watch researchers in Kenya’s Turkana County from April to October 2014, followed by research and additional meetings with Kenyan national government officials between November 2014 and February 2015.

Turkana County was chosen as the location for this research for a number of reasons. Its traditional reliance on natural resources for food and livelihood, the historic marginalization of the region and lack of infrastructure, its considerable population growth, and the threat to Lake Turkana of Ethiopian development projects make the region especially vulnerable to drought that may be intensified by climate change. Turkana is home to Lake Turkana, the largest desert lake in the world, and is also globally renowned as the cradle of mankind. Pastoralist areas in East African countries tend to have the highest incidence of poverty and the least access to basic services compared with non-pastoralist areas. For hundreds of years, nomadic herders have lived in semi-arid lowlands like Turkana County, adapting to the unpredictable environment by moving livestock according to the shifting availability of water and pasture. Like many other pastoralists in East Africa, the Turkana people have long struggled to access sufficient food and water. Historic marginalization and their livelihood in a fragile ecosystem make them especially vulnerable to the effects of any changes in the environment and climate. Their situation illustrates how climate change could aggravate existing obstacles to the realization of basic human rights and challenge the ability of governments to protect and fulfill those rights.

In the course of this research, Human Rights Watch conducted 40 interviews with pastoralists and fishers along the western shore of Lake Turkana. Human Rights Watch also interviewed health clinic staff, school students, teachers, local civil society, county government officials and police officers in Turkana County, many of them in Lodwar, the county’s capital. In addition, Human Rights Watch met with representatives of the Kenyan national government and Kenyan civil society during the climate change conferences in Lima, Peru (December 2014), Geneva, Switzerland (February 2015), and Bonn, Germany (June 2015), following up via email on issues raised at the meetings. On March 3, 2015 Human Rights Watch wrote to the national government and requested information on national climate change policy. No response was received at time of writing.

Interviews were conducted in Turkana and English using interpreters when necessary. None of the interviewees were offered any form of compensation and all interviewees were informed of the purpose of the interview and its voluntary nature, including their right to stop the interview at any point. All individuals interviewed gave informed consent to be interviewed. Although most individuals were interviewed individually, some interviews with pastoralists were conducted in group settings, in line with community norms. A broad range of interviewees was sought, including men and women of different ages and livelihoods. However, 30 of the 40 interviewees were men.

In addition to interviews, Human Rights Watch consulted various secondary materials, including academic articles and reports from nongovernmental organizations, which provide further insight into human rights issues in Turkana. This material includes previous Human Rights Watch research as well as information collected by other credible experts and independent researchers. In addition to the current work in Turkana County, Human Rights Watch has been monitoring development in the lower Omo valley for the past several years, for example issuing a report in 2011 and satellite analysis in 2014 on the forced displacement of indigenous pastoral communities to make way for state-run sugar plantations.

An external technical expert reviewed an earlier draft of this report. However, this report is not a comprehensive assessment of the environmental and climate change threats to local communities in Turkana County. Such an assessment would require more in-depth qualitative and quantitative investigation, including in southern and western Turkana County, as well as mathematical modeling of multiple climate change scenarios.

Map of Turkana County

I. Introduction

Although evidence of climate change, and its causes, has been debated for more than two decades, there is now scientific consensus that climate change is occurring and is due to human activity.[1] Over the past century, the earth’s average temperature has risen by 0.8° Celsius (1.4° Fahrenheit), the oceans have warmed, the amounts of snow and ice have diminished, and sea levels have risen.[2] According to scientific studies, low-lying countries such as Bangladesh and the Maldives, arid and semi-arid areas from Senegal to Kenya, and many parts of the Arctic are already experiencing significant effects from climate change, such as flooding, heat shocks and melting permafrost.[3]

Human rights bodies, scientific experts, governments, and civil society have recognized that worldwide, climate change is having, and will continue to have, a devastating impact on the ability of people to enjoy their basic human rights and the capacity of governments to fulfill their obligations to realize those rights.[4] For vulnerable populations, these events can lead to the loss of their lives, homes and livelihoods. The earth’s surface temperature is projected to rise further, heat waves are likely to occur more often and last longer, extreme precipitation events will become more intense and frequent, the ocean will continue to warm and acidify, and the global mean sea level will continue to rise.[5] These changes, and the costs associated with them, threaten the ability of governments, particularly in low and middle-income countries, to progressively realize the full range of human rights.[6]

While there is scientific consensus about global trends related to climate change, modeling and forecasting future changes in climate, particularly in specific regions and sub-regions of the world, is by its very nature complex and subject to some degree of uncertainty. These uncertainties result from a wide range of factors, including limited climate data and the challenge of evaluating the dynamics of complex interacting systems.[7] However, scientists agree that the impacts of climate change are, and will be, unevenly distributed among different parts of the world and within a society.[8]

Countries in the global South, which are least responsible for climate change, are predicted to experience its most severe effects.[9] According to the IPCC, climate change is expected to lead to disproportionate increases in ill-health in developing countries with low income.[10] In addition, the IPCC has recognized that climate change will affect disadvantaged people more severely.[11] The United Nations Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights has predicted that indigenous populations, marginalized groups, women, and people with disabilities—populations that are already vulnerable to human rights abuses—will face the biggest challenges adapting to a changing climate.[12] UN Women found that in developing countries, where agricultural work accounts for about two-thirds of the female labor force, decreases in agricultural output due to climate change will most affect women.[13]

Recognizing these risks, the UN Human Rights Council and other human rights bodies have adopted resolutions and issued statements highlighting the implications of climate change for the full enjoyment of human rights.[14] In December 2014, 76 UN human rights experts called on the “States Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) to ensure full coherence between their solemn human rights obligations and their efforts to address climate change, one of the greatest human rights challenges of our time”.[15]

II. Climate Change in Africa

Scientists believe Africa will be one of the continents most vulnerable to climate change, with average temperatures expected to increase throughout this century, and with drier subtropical regions warming more than the moister tropics.[16] In its latest report, issued in November 2014, the IPCC states that the continued global emission of greenhouse gases will increase the likelihood of severe, pervasive, and irreversible impacts for people and ecosystems in Africa, including but not limited to its effects on water, food, and health.[17]

The 2014 IPCC report also emphasized that climate change will cause economic growth to slow.[18] These predictions—of water and food insecurity, negative health effects, and economic stagnation—will compound the challenges facing areas of Africa with already weak health and development infrastructure, potentially resulting in increased displacement and conflict.[19]

According to the IPCC and other scientific studies, the African continent is already experiencing the effects of climate change in many regions.[20] For example, a recent study characterized parts of Sudan and Ethiopia; the central African countries surrounding Lake Victoria; and the continent’s southeast, including Mozambique, Zimbabwe and parts of South Africa, as “global hotspots” of climate change, with a high likelihood of drought or flooding and declining crop yields or ecosystem damages on top of high population and poverty rates.[21] Similarly, the United States Institute for Peace has predicted that climate change will result in more drought, more severe changes in weather, and shorter but more intense rainfall in Nigeria, and that these changes may contribute to desertification and increased scarcity of arable land and conflict.[22] The South African government has also stated that even under conservative scenarios the country is likely to experience increased drought, accompanied by more frequent flooding, a significant decrease in water availability, and a rise in sea level.[23]

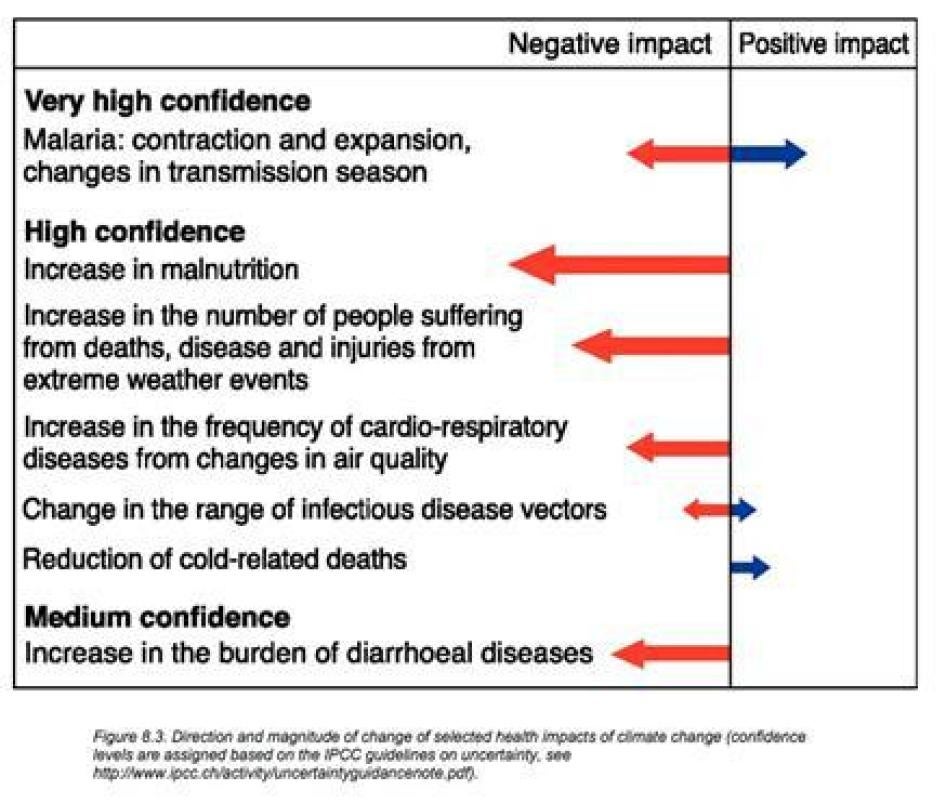

In addition to direct effects from heat stress attributed to climate change, scientific studies show that recurring drought and food insecurity can have indirect effects on health. According to the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report, climate change has already altered the distribution of some disease vectors, such as mosquitoes and ticks that have an active role in transmitting a pathogen from one host to another, and which carry a range of diseases such as malaria, dengue fever, spotted fever rickettsioses, and Rift Valley fever.[24]

Severe weather events and flooding may also affect health directly by injury or death, and indirectly by contaminating water supplies or destroying water delivery and wastewater systems. Research by UNICEF suggests that climate change will have a significant impact on the health of children through increases in vector and waterborne diseases, and as a result of rising food prices and conflicts over resources.[25] Other factors that also relate to climate change, such as changes in land use and population density, may mitigate or exacerbate health impacts.

As recognized by the IPCC, changes in climate and the resulting changes in disease patterns, poverty eradication, conflict and food security, have significant implications for access to water, food and health in Africa.[26] For example, gains in social and economic rights, such as the rights to education, housing and health, gender equality and other rights requiring allocation of resources and access to justice, may be more difficult to realize as climate change reduces the availability of resources to the government and adaptation to climate change diverts otherwise available resources.[27]

African regional institutions have long highlighted the vulnerability of African states to the effects of climate change. Starting in 2007, the African Union has passed a number of resolutions expressing concern about the impact of climate change and the ability of countries to respond to its consequences.[28] In 2009, the African Ministerial Conference on the Environment (AMCEN) adopted the Nairobi Declaration on the African Process for Combating Climate Change. Ministers from more than 30 African countries agreed that “while Africa has contributed the least to the increasing concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, it is the most vulnerable continent to the impacts of climate change and has the least capacity to adapt.”[29] African Parliamentarians echoed this call the same year, and called for “concrete action to reduce disaster risks and adapt to climate change as a matter of urgency.”[30] The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rightsalso passed a resolution in 2009 urging the inclusion of human rights safeguards into climate change laws and treaties and committing the Working Group on Extractive Industries, Environment and Human Rights Violations in Africa to carry out a study on the impact of climate change on human rights in Africa.[31] In this resolution, the Commission expressed concern that the “lack of human rights safeguards in various draft texts of the [climate change] conventions under negotiation could put at risk the life, physical integrity and livelihood of the most vulnerable members of society notably isolated indigenous and local communities, women, and other vulnerable social groups.”[32] The United Nations Economic Commission for Africa and the United Nations Development Program have also expressed concern about the effects of climate change on particularly vulnerable groups and individuals in Africa, including women.[33]

|

African Regional Instruments and Decisions on Environment, Climate Change, and Human Rights African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (1981), art. 24[34] “All peoples shall have the right to a general satisfactory environment favorable to their development.” Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa (2003), art. 18[35]

African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights

African Union

3. Decision on Africa’s Preparation for the United Nations Conference on Climate Change (2012)[40]

African Ministerial Conference on the Environment: Nairobi Declaration on the African Process for Combating Climate Change (2009)[41]

|

III. Water, Food, Health, and Security in Turkana County

Background

Turkana County, located in the northwest corner of Kenya, and bordered by Uganda to the west and South Sudan and Ethiopia to the north and northeast, is Kenya’s largest county. It has a semi-arid to arid climate and is among the poorest counties in the country.[42]

|

Political Structure of Kenya The 2010 constitution addressed public concerns about the concentration of power in the presidency by introducing a devolved system of government. County governments were established after the March 2013 general elections. Under the new structure, 47 county governments around Kenya have semi-autonomous status from the central government in order to address the inequitable distribution of resources that stemmed from centralization in the past.[43] The devolution of basic functions to the county level has coincided with increased interest in the Turkana region from the national government due in part to promising results from oil exploration. Some functions critical for the lives of the Turkana, including provision of health and education services, have been devolved to the county level. Considerable ambiguity exists between national and county levels of government over other functions of importance to the Turkana, including security and natural resource management. |

The region encompassing Turkana County, the Lower Omo River valley, and the eastern shores of Lake Turkana, is globally renowned as the cradle of mankind: Archeologists working in the region have found here the oldest ancestors to modern humans.[44] However, the region’s more recent history is one of colonial rule and neglect. Despite resistance, the British colonized the area in the 1920s and forced the Turkana to settle in the area now known as Turkana County. After the Second World War, the colonial administration segregated the Turkana people by categorizing Turkana Province, as it was known under colonial rule, as a closed district, and enforced a strict disarmament of the Turkana people. The Turkana strongly resisted the colonial administration and the region suffered continued marginalization and underdevelopment, while experiencing repeated raids from Ethiopia’s Daasanach tribe, an agro-pastoral ethnic group. After independence, there was increased development in Turkana, but antagonistic relations and cattle raiding between the Turkana and their neighbors continued. Insecurity, combined with two severe droughts in the early 1980s, further inhibited development efforts in the region.

In 2013 the Kenyan national government devolved some government functions to county governments. This change provided opportunities for the Turkana to have more control over local policymaking and the allocation of resources, but the county continues to be underdeveloped and politically marginalized, ranking as one of the poorest counties in Kenya.[45] There is little health, education, transportation or economic infrastructure.[46] More than 85 percent of the population lives below the poverty line, and only 15 percent of the population has received a primary school education.[47] A majority of the Turkana population uses unimproved water sources for drinking, and less than 10 percent of the population has access to improved sanitation services.[48] Maternal mortality in Turkana is three times the national average.[49] Insecurity is also a major problem in Turkana and is made worse by the proliferation of small arms from neighboring countries, with persistent cattle raiding to and from neighboring regions.[50] The causes of these conflicts are long-standing, with competition over scarce grazing land and water resources a key component of the tension.[51]

Along with Marsabit and Samburu Counties, Turkana County is home to Lake Turkana, the largest desert lake in the world. While the lake is critical for livelihoods, water in the lake is largely unfit for human consumption due to high salinity levels.[52] Accessing potable water is difficult for many people in Turkana, because the region experiences a long dry season and frequent periods of drought. People in Turkana rely mostly on water from seasonal rivers for drinking and domestic uses, often accessing it by digging in dry riverbeds, but also collecting water from springs, boreholes, and the near-perennial Turkwel River.[53]

According to the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, Turkana County’s population has grown rapidly in the last two decades.[54] According to the Turkana County government, the current population growth rate is 6.4 percent per annum, with an estimated 1,256,152 people in 2015.[55] Fifty-nine percent of households have more than seven members, and almost half of the total population of the county is under 14 years old.[56]

Populations within Turkana County concentrate around the main transport route, which enters Turkana County from Kitale and West Pokot and connects the principal market towns of Lokichar, Lodwar, Kakuma and Lokichogio, and along the Turkwel River (coming from West Pokot, and crossing the main transport route at Lodwar, heading east into Lake Turkana).[57] However, the majority of the population is pastoral, relying on migratory livestock herding. Some Turkana also engage in crop cultivation along the region’s watercourses, while others fish in the waters of Lake Turkana or reside in the county’s towns.

The Turkana identify themselves as indigenous peoples.[58] The United Nations’ Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues describes indigenous peoples to include those who self-identify as indigenous peoples; peoples with a historical continuity with pre-colonial and/or pre-settler societies; those with a strong link to the territories and surrounding natural resources; groups with distinct social, economic, or political systems; a distinct language, culture, and beliefs; and those who maintain and reproduce their ancestral environments and systems as distinctive peoples and communities.[59]

The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights has similarly set out criteria for determining indigenous peoples, and made its first ruling in 2010 on indigenous peoples’ rights in a case concerning the Endorois, a pastoralist people from Lake Bogoria in Kenya’s Rift Valley.[60] The Commission noted the 2007 report on Kenya by the then UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights and fundamental freedoms of indigenous people which found that in Kenya indigenous populations and communities included pastoralist communities such as the Endorois, Borana, Gabra, Maasai, Pokot, Samburu, Turkana, and Somali, and hunter-gatherer communities whose livelihoods remain connected to the forest, such as the Awer (Boni), Ogiek, Sengwer, or Yaaku.”[61]

In March 2015, the Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples noted that indigenous peoples have contributed little to climate change, but they suffer the worst impacts globally.[62] Various other UN human rights bodies have also acknowledged the specific burden that climate change places on indigenous peoples.[63]

Evidence of Climate Change and Development Impacts in Turkana County

The government of Kenya’s Meteorological Department has documented increased average temperatures across the country since the early 1960s, with a rise of mean maximum temperatures disproportionately affecting the northern parts of the country.[64] The department has also reported changing precipitation patterns with an increase in rainfall events between September and February (extending the period known as the ‘short rains’ into the formerly dry months of January and February) and a decrease in precipitation during the traditional rainfall season (March-May). As a result, certain areas may experience extreme high intensity rainfall, while the overall annual rainfall remains neutral or even decreases slightly.[65]

Regional scientific studies have found increases in mean surface temperatures, and changes in precipitation extremes during the past 30 to 60 years.[66] Rising Indian Ocean surface temperatures, resulting from climate change, are believed to have contributed to the increased occurrence of droughts in the region.[67] According to some studies, this ocean warming has led to a general decline of eastern African rainfall from March to June—the season referred to as the ‘long rains’ in Kenya.[68]

In Turkana specifically, climate data from a meteorological station in Turkana’s capital Lodwar documents increased (minimum and maximum) temperatures of 2-3°C (3.6 to 5.4°F) between 1967 and 2012.[69] Rainfall patterns in Turkana also appear to have changed, with the short rainy season becoming longer and wetter and the long rainy season becoming shorter and dryer.[70] Overall annual rainfall in Turkana remains at low levels, with repeated intense droughts across Northern Kenya.[71] These patterns appear consistent with scientific evidence suggesting a correlation between increasing overall temperatures on the one hand, and droughts and more extreme rainfall on the other.[72]

Despite these findings, it remains difficult for scientists to predict future long-term effects of climate change in the East Africa region, in part because there is insufficient historical data of climate patterns.[73] As a result, projections vary in their conclusions about East Africa’s likely future precipitation and temperature patterns.[74] Nevertheless, the most recent reports suggest that East Africa will continue to experience increased drought, with reduced precipitation during the long-rain season.[75]

The Kenyan government has acknowledged these changes, identifying, for example, in its National Climate Change Action Plan 2013-2017, “prolonged droughts; frost in some of the productive agricultural areas; hailstorms; extreme flooding; receding lake levels; drying of rivers and other wetlands” and associating these changes to “large economic losses and adverse impacts on food security.” The Plan further notes:

Many of these extreme climate events have led to displacement of communities and migration of pastoralists into and out of the country resulting in conflicts over natural resources. Slow-onset events associated with climate change also lead to competition over scarce resources resulting in human-wildlife conflicts. Other climate change impacts include widespread disease epidemics, sea-level rise, and depletion of glaciers on Mount Kenya.[76]

Industrial and agricultural development across Turkana’s northern border with Ethiopia also threatens the welfare of the Turkana. Over the past several years, Ethiopia has embarked on a massive plan for dams, water-intensive irrigated cotton and sugar plantations, and irrigation canals and other infrastructure in the Omo River Basin, which provides 90 percent of the water in Lake Turkana.[77] Hydrologists predict that these developments, including the Gibe III dam, Africa’s tallest, which began filling its reservoir in 2015, could have a devastating impact on Lake Turkana, dropping water levels and potentially causing the lake to recede into two small pools.[78]

If these predictions are accurate, areas of Lake Turkana with high levels of biological productivity that are critical for fish spawning and rearing will dry up, with devastating impacts on the fishery. In addition, dramatic reductions in freshwater inputs from the Omo River into Lake Turkana, and increased evaporation rates from higher average air temperatures, will increase levels of salinity in the lake, also harming fish stocks.

Changes to Lake Turkana will impact the environment far beyond its shores. The lake has a significant cooling effect on the region, regulating temperatures and precipitation, and preventing desertification.[79] Ethiopia’s development projects, in conjunction with climate change, could also have an impact on some large non-renewable energy projects that utilize current climatic conditions, such as a €620 million wind farm planned for an area 9 kilometers southeast of Lake Turkana.[80]

Despite these catastrophic projections, the Kenyan government’s public criticism of the damming of the Omo River stopped in 2012 when it signed a deal with Ethiopia to import electricity produced, in part, by Gibe III. The Turkana County government has also been largely silent, and the county’s 2013-2018 Integrated Development Plan does not mention threats to Lake Turkana from the dam or irrigation schemes.[81] A joint process initiated in 2013 between the governments of Kenya and Ethiopia, facilitated by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP), to develop a Turkana-Omo basin management plan has not addressed the potential impact on the lake either, and is currently stalled. In 2014, as a result of a lawsuit filed by the NGO Friends of Lake Turkana, the Kenyan High Court ruled that the government is required to make public all relevant information in relation to the importation, purchase, and transmission of electricity from Ethiopia. As of September 15, 2015, it has yet to comply with this decision.[82] The World Bank, African Development Bank, and French government are partially financing the electricity infrastructure that will export the power to Kenya.[83]

Two other major development opportunities that are underway in Turkana County may affect the region’s water supplies. In 2012, the government of Kenya announced the discovery of major oil reserves in Turkana, and in 2013 the government announced the identification of a water aquifer estimated to contain enough water to supply Kenya’s water needs for the next 70 years.[84] While the economic feasibility of tapping the oil reserves is uncertain, and studies to determine whether the aquifer is suitable for human consumption are ongoing, these announcements have raised expectations for economic development and the ability to address chronic water and food shortages. Questions about the long-term sustainability of the aquifer, including how quickly the aquifer would replenish itself after water has been extracted, have also been raised.[85]

Impact of Climate Change on the Enjoyment of Human Rights

The famine has displaced people. The herd boys who were looking after the livestock have lost everything, now they have nothing to do. We have no choice but to put our hands up and ask for help. Where will we go now? It is death that awaits us.

-- Pastoralist O.L., September 2014

The pastoralists and fishers in Turkana County interviewed by Human Rights Watch painted a picture of a population struggling to survive in an inhospitable climate, ill-equipped to adapt to increasing changes in climate and livelihoods and receiving little support from government or civil society. They stated that changes in climate are already having a significant impact on their welfare in multiple ways. In combination with rapid population growth and industrial development, climate change is exacerbating the already significant challenges the Turkana face in securing sufficient water, food, health and security.

Right to Water

In Turkana, access to water for consumption, basic household needs, and livestock is critical for the lives and livelihoods of the Turkana people. However, growing water demand brought on by population growth, unpredictable rainy seasons and longer and more regular droughts have put increased pressure on water resources in recent years. In addition, the predicted drop in the water level of Lake Turkana could have a major impact on water availability for years to come.

One elder living near Lake Turkana described his reliance on the lake in times of drought. He said:

In the past, I came to the lake because my animals had all died. I came telling myself I can get something to feed my stomach here. What will happen when I arrive and the lake has been closed [disappeared]? How will I survive when my animals have died and the lake has disappeared? How will I survive when the drought sweeps me away and sends me to my grave?[86]

Traditionally, in times of drought, many pastoralist communities dig in dry riverbeds for water. However, communities now report longer and more severe droughts. As a result, they must dig deeper, but still may not find water. One woman said:

When God grants us rainfall, that’s when we access water at the banks of the river or by digging shallow wells. Now, during the dry season, we have to walk to the lake, which takes more than half a day. It is far.[87]

Human Rights Watch visited a girls’ school where the girls must walk several kilometers every day to reach a dry riverbed where they dig for water and then transport 25-liter jerry cans back to the school.

In one pastoral community a woman who was nine months pregnant, told Human Rights Watch of the 18 kilometer round-trip she had to walk, sometimes twice daily, in order to get water during the dry season from a riverbed where she could dig for water. The small stream adjacent to the village supplied water only during the short rainy season. She said:

During this dry season I go often [to the river] not just once a day, but morning and then later in the evening, and tomorrow again the same thing. The whole village depends on this river alone, both people and livestock. Some time back, when the rain was enough, the water [from rains] could last for even four months [in the adjacent stream]. But now things have changed, as the wells dry very fast.[88]

Kenya is bound under international law to progressively realize the right to water and sanitation of its citizens, using available resources in a non-discriminatory manner.[89] As the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has articulated, the right to water encompasses a right to sufficient, safe, acceptable, physically accessible and affordable water for personal and domestic uses.[90]

The United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights adopted General Comment No. 15 on the right to water in 2003. Derived from a number of other rights guaranteed by international human rights law and complemented by more recent international human rights treaties explicitly recognizing the importance of water and sanitation, the general comment states that:

The water supply for each person must be sufficient and continuous for personal and domestic uses. These uses include drinking, personal sanitation, washing of clothes, food preparation and household hygiene. […] Some individuals and groups may also require additional water due to health, climate, and work conditions.[91]

Because climate change can increase the frequency and severity of extreme weather events, such as drought or flooding, it can have a negative impact on the availability, accessibility, and quality of water. When economic resources are limited, government obligation to progressively realize the human right to water requires States to plan adaptation measures.[92] According to the Special Rapporteur on the human right to water, “[p]lanning for resilience to climate change is essential for the protection of water resources, and requires careful consideration of how water can safely be reused in domestic, agricultural and industrial contexts.”[93]

International human rights law also imposes obligations on states that are of immediate effect. The obligation to address the right to water in a way that is participatory, accountable and non-discriminatory is an immediately binding duty.[94] Article 2(2) of the ICESCR obliges each State party “to guarantee that the rights enunciated in the present Covenant will be exercised without discrimination of any kind.” According to the Committee “[e]liminating discrimination in practice requires paying sufficient attention to groups of individuals which suffer historical or persistent prejudice instead of merely comparing the formal treatment of individuals in similar situations.”[95]

Lack of access to potable water has a broad impact on all segments of society, but it disproportionately affects some populations. Accordingly, the Committee, in General Comment 15, notes that states have a particular obligation to ensure access to water for vulnerable groups, stating that “[w]ater and water facilities and services must be accessible to all, including the most vulnerable or marginalized sections of the population, in law and fact, without discrimination on any of the prohibited grounds.”[96] This requires the adoption of comprehensive and integrated strategies and plans including “assessing the impacts of actions that may impinge upon water availability and natural-ecosystems watersheds, such as climate changes.”[97]

In 2010, Kenya, along with 120 other counties, voted in the UN General Assembly to recognize a freestanding right to water, derived from the legal framework laid out in General Comment 15. In addition, the 2010 Kenyan constitution provides that all citizens have a right to “clean and safe water in adequate quantities.”[98] According to the constitution, this right is to be realized progressively and in a non-discriminatory manner.[99] In particular, the constitution calls for “affirmative action programmes and policies designed to ensure that minorities and marginalised groups […] have reasonable access to water, health services and infrastructure.”[100]

Water access also appears in numerous Kenyan policies and laws, such as the Water Act and the Environment Management Coordination Act.[101] In its 2009-2012 Strategic Plan, the National Ministry of Water and Irrigation references the challenges to water access posed by climate change, such as “species losses and seasonal changes/shifts negatively affecting rain-fed agriculture [c]limate-related disasters such as droughts, floods, landslides, wind storms and hailstorms […] heightening food insecurity and causing economic losses”, and proposed measures such as the increased drilling of boreholes to minimize the impact of drought.[102]

Despite the Ministry’s recognition of the extra stress on water resources due to climate change, and Turkana County deputy governor Peter Ekai Lokoel’s statements (below) of efforts to install new borehole wells, communities in Turkana told Human Rights Watch that they were not aware of new water infrastructure being developed.

Right to Food and Livelihood

Livestock herding and fishing, the Turkana’s two main livelihoods, are extremely susceptible to changes in environment – shifts in water availability, temperature or other environmental variables can have a devastating impact on livelihoods.[103] While people in Turkana County have long experienced cyclical drought and famine, a number of people told Human Rights Watch that more intense and frequent droughts and a rainy season that was shorter than in recent years has reduced grazing lands, and limited water sources, necessary for dry season livestock herding. They pointed out that this has a variety of consequences for herders and can have self-reinforcing negative effects.

The acute physical strain on livestock created by the lack of water and adequate grazing land makes livestock weaker and more prone to disease, and less suitable for production of milk, one of the staples of the Turkana diet. Prolonged dry seasons lead to reductions in livestock numbers and less resilient livestock, to lower rates of milk production, and to reduced birthing rates. Diminishing access to grazing land and water also push the Turkana into increased conflict over remaining resources, which can lead to loss of livestock from raids by other ethnic groups.[104]

One pastoralist said:

When we raise livestock and the drought kills all of them we have no other way. That’s why we are poor. That’s the hunger we are suffering. When it rains there are no more animals left to graze.[105]

One of the key coping mechanisms for pastoralists during times of drought is foraging, mostly for the fruit of the Eeng’ol or doum palm (hyphaene compressa), a small dense fruit that children often rely on for their primary source of nutrition. In several interviews mothers told us about losing their children to starvation. One woman told us, “One of my children became sick during the previous drought, and died due to starvation and sickness.”[106]

Parents expressed hopelessness while describing the challenges in accessing enough food to feed themselves and their children. They said that the death of their livestock put an extra burden on households that traditionally rely in part on meat and milk for sustenance. Community members routinely cited hunger and malnutrition as among the most severe challenges they face.

A male elder from one of the areas hardest hit by the drought said:

There is no time left due to hunger in Turkana: for children, women and everybody. Now, if you decide to help, you may find no one. There isn’t much time left for us.[107]

While food insecurity has plagued Turkana for generations, Human Rights Watch interviews with people in Turkana indicated that the changing climate is exacerbating this already tenuous situation. The reported patterns of unpredictable rainfall and increased drought will continue to reduce the grazing lands and limited water sources necessary for dry season livestock herding. This will further compound existing food insecurity for a growing population that is largely reliant on adequate grazing lands and water for its livestock.

The other critical livelihood in Turkana is fishing. Reductions in Lake Turkana’s water levels from the Omo basin developments will likely decimate Lake Turkana’s fishery.[108] The government of Ethiopia’s environmental studies did not include any consideration of the cumulative impacts of the developments on downstream ecosystems, and disregarded Lake Turkana altogether. Water level drops of between 13 and 22 meters (because of decreased freshwater inputs from the Omo River) are predicted to reduce the lake volume by 42 to 59 percent, and lake shorelines will recede. The reduction of natural floods by the construction of dams will diminish the signal for fish breeding.[109] Salinity levels will increase due to the decline of the Omo River’s freshwater flows into Lake Turkana. Given Lake Turkana’s role in the regulation of air temperatures in the region, climate change and a reduction in water levels could also lead to higher localized temperatures and increased rates of evaporation, further increasing salinity.

Fishing is also critical for many pastoral communities. Pastoralists migrate to Lake Turkana to fish or engage in other economic transactions with fishers when livestock have been lost from prolonged periods of drought or from raids. Income from fishing is a critical alternative source of income to pastoralists to mitigate the impact of these losses. Threats to Lake Turkana affect the ability of pastoralists to use the lake as a buffer against the increased periods of drought that decimate their livestock herds. The lake also forms a physical barrier between the Turkana and ethnic groups inhabiting the other shores. Its loss will likely make the area less secure.

An elder near the north part of Lake Turkana we spoke to said:

The lake is like our farm. We wake up in the morning and go fishing to support our children and family.[110]

Another pastoralist, living near Lake Turkana said:

The famine has displaced people. The herd boys who were looking after the livestock have lost everything, now they have nothing to do. We have no choice but to put our hands up and ask for help. Where will we go now? It is death that awaits us.[111]

The Constitution of Kenya provides that “Every person has the right to be free from hunger, and to have adequate food of acceptable quality.”[112] The right to adequate food is also enshrined in a number of international instruments, including the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which Kenya ratified in 1972.[113] Pursuant to article 11(1) of the Covenant, States parties pledge to use available resources to progressively realize "the right of everyone to an adequate standard of living for himself and his family, including adequate food, clothing and housing, and to the continuous improvement of living conditions." As with all socioeconomic rights, the right to adequate food will have to be pursued in a non-discriminatory manner. Moreover, states have a core obligation to take the necessary action to mitigate and alleviate hunger as provided for in article 11(2), even in times of natural or other disasters.[114] In its General Comment No. 12 on the right to adequate food the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights’ states:

Even where a State faces severe resource constraints, whether caused by a process of economic adjustment, economic recession, climatic conditions or other factors, measures should be undertaken to ensure that the right to adequate food is especially fulfilled for vulnerable population groups and individuals.[115]

Food insecurity in Turkana is not a new issue, and the government has long had an obligation to deploy available resources to progressively realize the right to adequate food. However, based on existing climate modeling, climate change is likely to add additional stressors on food security such as increased temperatures and shifted rainfall patterns that may be less favorable for livestock herding and agriculture. Although some pastoralists and fishers interviewed by Human Rights Watch were aware that there may be changes to the lake due to developments in the Omo River valley, no one we spoke with was aware of any government plan or action about alternative means of livelihood.[116] The Kenya government should take into account the impact of climate change in devising appropriate solutions to food insecurity. In addition, in areas where the population’s access to adequate food is already at risk, including due to drought or climate change, the government should avoid aggravating food insecurity.

Right to Health

The World Health Organization (WHO) has estimated that climate change will cause 250,000 additional deaths globally each year between 2030 and 2050.[117] Climate change will affect the right to health through increased malnutrition, increased disease and injury due to extreme weather events, and an increased burden of diarrheal, cardiorespiratory and infectious diseases.[118] In its most recent report, the IPCC concluded with “very high confidence” that through the middle of the current century climate change will affect human health “mainly by exacerbating health problems that already exist”, and with “high confidence”, that climate change would lead to increases in ill-health especially in developing countries with low income.[119]

Scientific studies have found that the impact of climate change on health and life expectancy in Africa include direct effects from heat stress and indirect effects from the shifting epidemiology of diseases, such as West Nile fever, dengue, malaria, and yellow fever. Diseases that are waterborne, or relate to poor sanitation stemming from lack of water, are also likely to be influenced by climate change, increasing risks of cholera and typhoid outbreaks and greater rates of diarrhea and trachoma.[120]

One study in Kenya found a relationship between trends in climate since 1975 (rising temperatures and declining rainfall) and childhood stunting, which is an indicator for childhood malnutrition.[121] There are also indications that climate change will lead to increased malaria in many parts of the world, including in East Africa.[122] With temperatures warming, malaria is predicted to move, along with its mosquito vector, into higher altitude regions that have historically been malaria-free.[123] Other diseases, like trachoma, which affects 16 million Kenyans and is the leading cause of infectious blindness worldwide, may also be affected by changes in the climate and impacts on the availability of water and hygiene.[124]

Turkana has had a long history of chronic malnutrition and some of the poorest health indicators in Kenya, with minimal health investment and infrastructure, staff, and services for its largely mobile pastoralist population, all of which is exacerbated by a growing population.[125] Climate change is now creating added challenges for the health of the Turkana people.

Parents told Human Rights Watch about a wide range of illness that they and their children suffered, including stomach aches and diarrhea, malaria, malnutrition and trachoma. They said that these illnesses were worse with the most recent droughts, and that when community members are sick they often have to walk long distances to reach a medical clinic.

A village chief that we interviewed said:

There are two issues that are burning within me. These are malaria and the drought.[126]

Another pastoralist, living near Lake Turkana, said:

There is malaria in this area. There is no hospital here that can take in emergencies. Even when the kids fall sick, there is no help unless taken to Kolokol [nearest health facility, 40 km away]. Sometimes the patient dies on the way.[127]

At a health clinic we visited, the assistant health worker told us about chronic malnutrition in the surrounding communities and the difficulties of having one under-resourced health clinic serve a geographically dispersed population.

The worker, explaining the situation of local children, said:

These children with poor health, the small ones, are a lot in this village. Weak children with big bellies, protruding ribs and big heads. You will find a child is small but has a big head, a big stomach and the body has wrinkles like those of an adult, and yet he is a child. You will find a small child, but he looks like an old person. Yes, they are there. There are a lot of them. This problem might continue because of lack of food. They do not have food, and so it will continue because the problem is still there. Even children who are newly born will find the problem here.[128]

A teacher in a local school told Human Rights Watch:

Truthfully, health cases increase daily. For instance, we had drought so the children were hungry and this hurt them. When it rained, there was the problem of mosquitoes because mosquitoes spread malaria. There is the problem of the river. The water that came recently, when the children drink from it, their chest problems increase. Problems increase every season.[129]

Dr. Jane Ajele, the Turkana County Minister of Health, acknowledged the problems identified by the parents and the impact of the current drought and climate change. In an interview with Human Rights Watch, she highlighted trachoma, a bacterial eye disease that is transmitted from person to person or through clothing or flies, as of particular concern, with rising incidence resulting from decreased availability of water for hand and face washing.[130]

The Constitution of Kenya guarantees every Kenyan the right to the highest attainable standard of health.[131] The Kenyan Public Health Act also sets out to protect the public’s health, clarifying duties of health authorities and laying out regulations around sanitation, health facilities and infectious diseases.[132] Kenya’s international and regional obligations also require it to use available resources to progressively achieve the right to health for its citizens. Article 16 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights requires Kenya to take the necessary measures to achieve the right to health of its citizens. Article 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), which Kenya ratified in 1972, “recognizes the right of everyone to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health”, a right which like all in the ICESCR, states undertake to achieve full realization of progressively by taking steps individually and co-operatively to the maximum of available resources.[133] While the Covenant provides for progressive realization and acknowledges the limited availability of resources, it also imposes various obligations that are of immediate effect.[134] The General Comment Number 12 on the Right to Adequate Food states:

States parties have a core obligation to ensure the satisfaction of, at the very least, minimum essential levels of each of the rights enunciated in the Covenant…including…the right of access to health facilities, goods and services on a non-discriminatory basis, especially for vulnerable or marginalized groups.[135]

Ongoing and projected changes in climate will very likely make full realization of the Turkana people’s right to the highest attainable standard of health more difficult. As part of its obligations under the right to health, the Kenyan government needs to take action to address the acceleration of malnutrition and disease that is in part a result of climate change.

Right to Security

In Turkana, access to dry season grazing land and water drives conflict between pastoralist communities, including between the Turkana and the Pokot, and near the Ethiopian border, between the Turkana and the Daasanach.[136] While there are numerous variables that drive conflict between pastoralist communities in this area, a proliferation of small arms, the lack of effective state security, developments in neighboring countries, including in Ethiopia’s lower Omo River valley, and shrinking access to grazing lands and water have made traditional patterns of livestock raiding more frequent and deadly.[137]

In interviews in late 2014, pastoralists in northern Turkana described recent increases in conflict over grazing lands between Ethiopia’s Daasanach tribe, an agro-pastoral ethnic group, and the Turkana.[138] In Ethiopia’s Omo Valley, the land and water available to the Daasanach for grazing and farming is decreasing due to the displacement of Daasanach from their sorghum producing lands along the Omo River and from the conversion of their traditional dry season grazing lands into irrigated cotton and sugar plantations.[139] Consequently they are moving further into lands in northern Turkana County in search of dry season grazing land, land that they believe historically belongs to the Dassanach. While conflict between Turkana and Daasanach is long standing, local communities on the Western shores of Lake Turkana, including in Nachukule, told us they fear the raids will be more frequent.

Human Rights Watch visited one Turkana community in both early and late 2014. On our second visit, we found that the community had moved 20 kilometers south after having been displaced from their dry season grazing lands due to cattle raids by the Dassanach. One of the displaced pastoralists told Human Rights Watch:

This village was initially in Todonyang, but we were displaced and ran here to Nachukule. We couldn’t withstand [the attack] and defend ourselves. This situation is really ending the lives of the Turkana who live here.[140]

According to those Human Rights Watch interviewed, armed Daasanach herders took the majority of the cattle and dry season grazing lands with little resistance, and the Turkana community turned to fishing in Lake Turkana for their livelihoods. Kenyan security posts along the border, understaffed and under resourced, had little ability to stop the more heavily armed Dassanach. One pastoralist said:

I used to stay in Todonyang, but the Daasanach forced me to migrate to where I am now [Nachukule]. They killed us by the lake, killed our animals.[141]

Another elder pastoralist said:

I think our situation is worse now than before, because our fathers used to cultivate some farms, but now the Daasanach have blocked access to these fertile places.[142]

The state has a responsibility to take all reasonable steps to ensure the security of its citizens. However, the Kenya government has taken few proactive steps to protect Turkana residents from Daasanach raids. The February 2015 deployment of marine police on the lake is a step in the right direction although it is not clear how effective their operations have been. Such a security operation needs to be properly resourced and given a clear mandate.[143] The Kenyan government should also voice concerns with the government of Ethiopia over the adverse effects that developments in the Omo Valley are having, and will likely continue to have, on increasing levels of insecurity for Kenyan citizens.

V. Government Response

The Kenyan national, and the Turkana local, governments have acknowledged the impact climate change has had and will have on people’s access to water, food, health, livelihood and security. At the Climate Summit in New York in September 2014, Kenya’s president Uhuru Kenyetta urged countries to take decisive action on climate change. He said that climate change was a “serious global challenge that continues to affect Africa’s socio-economic development.”[144]

In interviews with Human Rights Watch, Turkana County officials, including the deputy governor, Peter Ekai Lokoel, the Minister of Water, Irrigation and Agriculture, Beatrice A. Moe, and the Minister of Health Services and Sanitation, Dr. Jane Ajele, acknowledged the impact of climate change on the county and its effects on the ability to realize the rights of pastoralists.

The deputy governor highlighted concern over the future of Lake Turkana and how the shrinking of the lake will affect both pastoralists and fishers. He told Human Rights Watch:

There are problems both because of climate and man that are affecting the lake. Once the lake dramatically reduces, people will have to find another way. We are looking at developing alternative or complementing livelihoods, so that we can diversify the livelihoods of people who live along the lake. The county government has to be proactive in thinking about how do we give life support to people who are fully dependent on the lake.[145]

Beatrice A. Moe, the County Executive for the Ministry of Water Service, Irrigation and Agriculture, cited the history of underinvestment in the region and the difficulty of coordinating a response between the county government, the national government and humanitarian and religious actors:

Turkana people have never gotten attention from various governments. If you look at our planning as a county, we are starting from the most basic. Look at water: it is managed by organizations or churches. The position of the government has never been very visible. Our challenge now is the many needs against the resources we have as a county government.[146]

The devolution of the government introduced by Kenya’s constitution in 2010 provides an opportunity to mainstream and integrate rights-based climate change adaptation planning at a national and local level. As a part of a constitutionally mandated process of decentralization, the Turkana County government assumed authority in 2013 with responsibility for the development and welfare of the Turkana County population. County governments are responsible for county legislation outlined in the Constitution. Functions relevant to the county’s climate change adaptation policies include agriculture, county health services, and the implementation of specific national government policies on natural resources and environmental conservation, including soil and water conservation.[147] The responsibility for natural resources and environment is, however, a shared function with the national government, which is responsible for the “protection of the environment and natural resources with a view to establishing a durable and sustainable system of development.”[148]

The Turkana County government has set ambitious plans to expand the number of health facilities and personnel, increase access to education, and address widespread food and water insecurity.[149] In interviews with Human Rights Watch, Turkana County officials pointed to a series of new initiatives they say will improve conditions within the county.

The Deputy Governor said:

In this first year we have dug 60 boreholes. We are trying to reduce the walking distance of people looking for water. Initially, people can walk 40 or 50 kilometers. As of now, we still haven’t reduced that, it is still considerably too far. But we are saying, that the time we [the current Turkana County government] are here, we should reduce that further to make sure that nobody in Turkana has to walk a distance to get water. That’s our mandate, to make sure they don’t have to do that, to make sure they have clean water, closer to their homes.[150]

Dr. Ajele, the Turkana County Minister of Health, said that eradicating malnutrition was the “flagship” of the new administration, and that the county government was committed to improving the health infrastructure. She said that the government had doubled the number of health facilities in each ward, from 30 to 60 facilities in the entire county. At the same time, she said that the county was struggling to staff the new facilities.[151] Despite an increase from 255 to 610 health staff, Dr. Ajele estimated that the county needed an additional 1,950 health personnel.

When asked specifically about plans to address climate change and its impact on the Turkana people, the government officials Human Rights Watch spoke with acknowledged the importance of the issue, but cited few concrete programs or actions taken by the Turkana government to prepare for its impact. Addressing climate-related insecurity, the deputy governor said:

Climate change is definitely leading to increased insecurity in Turkana…. As livestock moves, the grazing belt is shrinking and you meet with other groups fighting for the same, and that will spark conflict, definitely. We have asked our county executive to do mapping of all the grazing fields to help us to plan so during the dry season we can contain our pastoralists inside our borders so they don’t have to go outside [of Turkana territory]. We are trying to give services within the migratory cycles, trying to make sure our pastoralists are comfortable even during the dry season.[152]

The Deputy Governor expressed the desire to develop adaptation plans:

We are trying to reach out to other stakeholders, people with capacity and experience on how they can help the county government build the capacity to help the communities adapt to climate change.[153]

However, he expressed a less hopeful view:

Climate change is here with us. We cannot stop it, the only way is to see how to work around it. We don’t have many resources, we only have so much we receive, so when we do our county development plan, we also try to factor in emergencies that come with drought or security. But unfortunately what we put there is not enough. We don’t want to just tend to drought or emergencies; we also want to do development.

The Turkana County Integrated Development Plan 2013-2018 aims to “ensure the County’s preparedness and capacity to respond” to the effects of climate change including “high infant mortality […], increased resource based conflicts, [and] increased morbidity.”[154] However, the Development Plan indicates that no assessment has been done on the differential impact of climate change on marginalized populations, no climate change adaptation projects are underway, and no county adaption plan has been published at time of writing.[155] County government officials also told Human Rights Watch that there is no central coordination addressing climate change in the county, which could help ensure policy coherence.

The Kenyan national government has made several efforts towards developing a national policy addressing the effects of climate change, including a National Climate Change Response Strategy (2010) and a National Climate Change Action Plan 2013-2017. However, several initiatives begun by the Kenyan government have either not been completed or implemented, including a National Adaptation Plan, a draft Climate Change bill, and a National Climate Change Framework Policy.

The 2010 National Climate Change Response Strategy (NCCRS) was the first Kenyan national policy document to fully acknowledge climate change. It defined its objective as “enhanc[ing] understanding of the global climate change regime”, and “assess[ing] the evidence and impacts of climate change in Kenya.”[156] The NCCRS acknowledged the disproportionate impact of climate change across communities, groups and sectors and recommended the creation of vulnerability assessments and impact monitoring, accompanied by a policy, legal and institutional framework to combat climate change.[157]

While the Strategy did mention the “urgent needs of vulnerable socioeconomic groups”,it did not propose any concrete steps to identify and address those vulnerabilities.[158] The NCCRS proposed a wide range of indicators of the impact of climate change, including changes in the atmosphere, marine and terrestrial biodiversity and human health. However, it did not suggest specific measures of the impact of climate change on marginalized groups and individuals.

Three years after the NCCRS was released, the Kenyan government issued a National Climate Change Action Plan 2013-2017 (NCCAP).[159] According to the government, the NCCAP was developed through a consultative process involving the public sector, the private sector, academia and civil society.[160] It identifies certain sectors of Kenya’s economy that are particularly vulnerable to climate change impacts, including pastoralist livestock, water and health, and acknowledges that every Kenyan has the right to a clean and healthy environment.[161] The NCCAP also names several groups and individuals that are particularly vulnerable to climate change (including urban poor, women, children, and pastoralists).[162] It also acknowledges that states parties to the UNFCCC are required to prepare and implement a National Adaptation Plan (NAP), and said that such a plan would be finalized during 2013.[163] However, the Kenyan government told Human Rights Watch that the National Adaptation Plan has not yet been finalized.