Not Welcome

Jordan’s Treatment of Palestinians Escaping Syria

Summary

Since the beginning of the crisis in Syria in 2011, Jordan has welcomed over 607,000 refugees seeking safe haven from the bloodshed and fighting there. Jordan, however, has not allowed all groups from Syria to seek refuge in the country. Authorities began denying entry to Palestinians living in Syria beginning in April 2012 and officially declared a non-admittance policy in January 2013.

In declaring the policy, Jordanian Prime Minister Abdullah Ensour argued that Palestinians from Syria should be allowed to return to their places of origin in Israel and Palestine, and that “Jordan is not a place to solve Israel’s problems.” He said, “Jordan has made a clear and explicit sovereign decision to not allow the crossing to Jordan by our Palestinian brothers who hold Syrian documents…. They should stay in Syria until the end of the crisis.” The head of Jordan’s Royal Hashemite Court told Human Rights Watch in May 2013 that the influx of Palestinians would alter Jordan’s demographic balance and potentially lead to instability.

In accordance with this policy, Jordanian security forces turn away Palestinians from Syria at Jordan’s borders, and seek to detain and deport back to Syria those who enter at unofficial border crossings using forged Syrian identity documents, or those who enter illegally via smuggling networks. Jordan does in principle allow in Palestinians from Syria who hold Jordanian citizenship but even for this category of Palestinians, Jordanian authorities have denied entry to those with expired Jordanian documents and in some cases have arbitrarily stripped them of their citizenship and forcibly returned them to Syria.

Deportations of Palestinians to Syria are a violation of Jordan’s international obligation of nonrefoulement, the international customary law prohibition on the return of refugees and asylum seekers to places where their lives or freedom would be threatened or the return of anyone to the risk of torture.

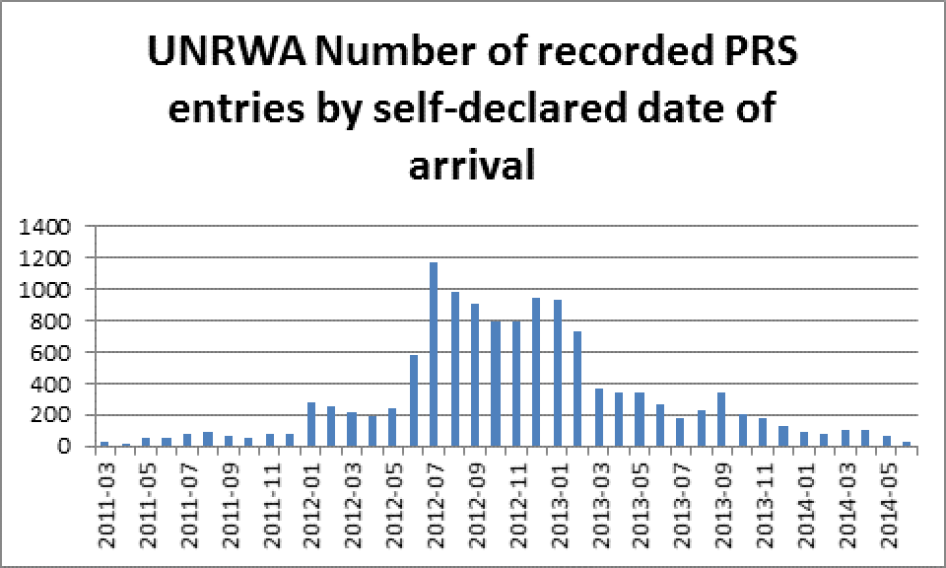

In spite of Jordan’s non-admittance policy, as of July 2014, over 14,000 Palestinians from Syria had sought support from the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) in Jordan since the beginning of the conflict. Of the 14,000, approximately 1,300 reported entering Jordan before authorities began pushbacks of Palestinians at the Syrian border. Most of these come from Palestinian refugee camps and villages in southern Syria or from the Yarmouk Palestinian refugee camp in the southern suburbs of Damascus, all areas that have witnessed intense fighting between Syrian rebels and government forces. Before the March 2011 uprising began, approximately 520,000 Palestinian refugees were registered with UNRWA in Syria.

As a result of the Jordanian government’s policy, many Palestinians from Syria do not have proper residency papers in Jordan and are therefore vulnerable to exploitation, arrest, and deportation. Undocumented Palestinians from Syria inside Jordan cannot call on the protection of the Jordanian government when facing exploitation or other abuses because of the risk of arrest and deportation. Unlike Syrians, Palestinians cannot legally live in the official refugee camps for Syrians and have no choice but to rent apartments in Jordanian towns and cities, but cannot legally work to earn money for rent.

According to the Syria Needs Analysis Project (SNAP), a non-governmental monitoring group that provides independent analysis of the humanitarian situation of those affected by the Syrian crisis, since 2013 Jordanian security services have detained and returned over 100 Palestinians to Syria. In its February 2013 Syria Crisis Response Annual Report, UNRWA noted that the agency has documented numerous cases of forcible return, including of women and children.

Human Rights Watch documented Jordan’s refoulement of seven Palestinians from Syria in 2013 and 2014, and the transfer of four others to Cyber City, a closed holding facility for Palestinian and Syrian refugees. At this writing there are approximately 180 Palestinians and 200 Syrians residing in the facility. Other than short periods of leave granted to some Cyber City residents every two to three weeks to visit their family members in Jordanian cities, Palestinians living in Cyber City can only leave the camp to return to Syria.

Jordan’s harsh treatment of Palestinians fleeing Syria also extends to Palestinian residents of Syria who are actually Jordanian citizens or descendants of Jordanian citizens of Palestinian origin. Many left Jordan to Syria during or after the 1970-71 Black September conflict between Palestinian guerrilla fighters and the Jordanian army. The Jordanian government has not explicitly stated that its non-entry policy for Palestinians is tied to the Black September history. Those who were involved in Black September would now be at least in their 60s, if not older, and their children and grandchildren should not be held accountable for acts that may have been committed by their parents or grandparents more than 40 years ago.

While Jordan has generally allowed Palestinians with valid Jordanian documents into the country, these individuals are at risk of being arbitrarily stripped of their Jordanian citizenship and deported if they seek to access government services in Jordan. Human Rights Watch documented the arrest and removal of citizenship from ten Palestinians who were Jordanian citizens. Jordanian citizens affected by withdrawal of citizenship have learned they had been stripped of their citizenship not from any official notice, but during routine procedures such as renewing a passport or an ID card, or registering a marriage or the birth of a child at Jordan’s Civil Status Department.

Some Palestinians deported to Syria, especially those stripped of their Jordanian citizenship, return to Syria without any form of valid identification, which renders them unable to cross government or opposition checkpoints, forcing them to remain indefinitely in small border villages without access to humanitarian assistance. Human Rights Watch spoke with two deported Palestinians with no identification currently living in a mosque in a Syrian border town.

In all cases of deportation documented by Human Rights Watch, Jordanian authorities separated Palestinian men from children, wives, parents, or other family members left behind in Jordan, depriving family members of a primary source of income in some cases.

Donor countries and local and international aid agencies have not acted to adequately address the humanitarian concerns facing Palestinians from Syria living in Jordan. Although at least 14,000 Palestinians have entered Jordan from Syria since the beginning of the conflict, few agencies provide any humanitarian assistance to these refugees. The 2014 Syria Regional Response Plan’s section on Jordan, which frames policy dialogue and operational coordination, excludes Palestinians, and the Inter-Agency Task Force (IATF), the local coordination mechanism for aid agencies working on the Syria refugee response in Jordan chaired by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), does not discuss issues relating to Palestinians from Syria.

The recent policy of non-admittance of Palestinians stands in marked contrast to Jordan’s treatment of Syrian nationals, upon whom Jordan has not placed any formal entry restrictions. Since the outbreak of fighting in Syria, over half a million Syrians have fled to Jordan, seeking refuge from violence and destruction in their homeland. The conflict has claimed at least 150,000 lives and left entire cities and villages in ruins.

Other countries in the region also deny safe haven to Palestinians fleeing the violence in Syria or restrict their entry. Other than Turkey, all of Syria’s neighbors have placed onerous restrictions on entry for Palestinians attempting to flee generalized violence and unlawful attacks by both government forces and non-state armed groups.

Although not a party to the 1951 Refugee Convention or its 1967 Protocol, Jordan is nevertheless bound by customary international law not to return refugees to a place where their lives or freedom would be threatened. The Executive Committee of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR ExCom), of which Jordan is a member, adopted Conclusion 25 in 1982, declaring that “the principle of nonrefoulement ... was progressively acquiring the character of a peremptory rule of international law.”

Jordanian authorities should rescind the non-admittance policy for Palestinians refugees from Syria and cease all deportations of Palestinian refugees back to Syria. The Jordanian authorities should admit Palestinians from Syria seeking refuge in Jordan at least on a temporary basis and allow them to remain and move freely in Jordan after passing security screening and finding a sponsor. Authorities should also halt arbitrary removal of citizenship from Jordanian citizens or descendants of Jordanian citizens who were living in Syria prior to 2011.

International donors and aid agencies should ensure that relevant agencies provide humanitarian and protection support to Palestinians from Syria on par with services offered to Syrian nationals in Jordan.

Jordan is not the only country neighboring Syria that has placed entry restrictions on Palestinians from Syria. All neighboring countries must respect the rights of Palestinian refugees to seek safety and asylum outside Syria as long as they face insecurity and persecution there. The burden of providing safety and asylum should not fall solely on the neighboring countries (Jordan and Lebanon being the preferred countries of flight for the Palestinians), but should be shared by countries in the region and beyond.

Countries outside the region should provide financial assistance to countries that take Palestinian refugees from Syria and consider accepting vulnerable Palestinian refugees for temporary humanitarian resettlement. Palestinian refugees should not have to forfeit their right of return by accepting an offer of temporary resettlement in a third country.

Recommendations

To the Government of Jordan

- Rescind its non-admittance policy for Palestinians from Syria seeking safe haven in Jordan.

- Cease detentions solely on the basis of their national origin of Palestinians from Syria seeking safe haven in Jordan.

- Cease deportations of Palestinians to Syria because of their national origin.

- Allow UNRWA in Jordan to provide its full assistance to Palestinians from Syria on the same basis as all Palestinian refugees.

- Allow international and local aid agencies to offer humanitarian assistance to Palestinian refugees from Syria on par with services offered to Syrian refugees.

- Allow inclusion of support for Palestinians from Syria in the inter-agency Syrian Regional Response Plan for Jordan.

- Halt the arbitrary withdrawal of citizenship from Jordanian citizens of Palestinian origin.

- Restore Jordanian citizenship to all persons who were arbitrarily deprived thereof. Each person deprived of their citizenship should be entitled to a fair hearing, with the right of appeal to the courts if their citizenship remains revoked.

To UNRWA

- Continue to monitor and report on Jordan’s refoulement of Palestinians from Syria.

- Continue to intervene with Jordanian authorities to open the border to Palestinian asylum seekers from Syria and to halt deportations, including by publically condemning such border closings and deportations.

- Continue to monitor conditions for Palestinians from Syria currently held in Cyber City and those detained in Jordanian detention facilities for entering the country irregularly, and advocate for their release.

To Refugee Aid Agencies Operating in Jordan

- Include support for Palestinians from Syria in the inter-agency Syria Regional Response Plan for Jordan.

- In coordination with UNRWA, ensure that Palestinians from Syria have access to humanitarian goods and services on the same basis as other Syrians who find themselves in Jordan.

- Advocate with the Government of Jordan to rescind the non-admittance policy for Palestinians from Syria and halt all deportations of Palestinians back to Syria.

To Countries Neighboring Syria

- Allow Palestinians from Syria to enter and seek asylum on the same basis as Syrian nationals.

- Do not deport Palestinians to Syria based solely on their national origin.

- Do not discriminate against refugees and asylum seekers on the basis of national origin.

To Israel

- Allow entry to Palestinian refugees from Syria who wish to return to areas controlled by Palestinian authorities, at least as a temporary measure notwithstanding the result of final status negotiations.

To Palestinian Authorities

- Intervene to press Jordanian officials to halt deportations and to open the border to Palestinian refugees from Syria on the same basis as Syrian nationals, including by publically condemning such border closings and deportations.

- Allow entry to Palestinian refugees from Syria who wish to return to areas controlled by Palestinian authorities, at least as a temporary measure notwithstanding the result of final status negotiations.

To Countries Providing Refugee Support to Jordan

- Seek assurances that Jordan will not reject any asylum seekers at its border with Syria or deport any refugees to Syria.

- Provide humanitarian support to help meet the needs of all refugees and asylum seekers from Syria.

To Countries Outside the Region

- Consider accepting Palestinian refugees from Syria for temporary humanitarian resettlement, without prejudice to their right of return

Methodology

This report is based on group interviews Human Rights Watch conducted with members of 12 Palestinian families, over 30 individuals, who fled Syria for Amman, Irbid, and Ramtha, all of whom have been affected by Jordan’s policy of non-admittance. Five of the twelve families described arrests and deportations of family members to Syria, and two others reported detentions of family members in Cyber City, a closed holding facility for refugees in northern Jordan. Three of the twelve families entered using Jordanian identity documents, including expired passports, family books or birth certificates. Three of the twelve families told Human Rights Watch that Jordanian officials withdrew Jordanian citizenship from family members who sought to renew Jordanian ID documents, rendering them stateless and without an identity document to confirm their identity once deported to Syria.

Human Rights Watch researchers explained the purpose of the interviews, gave assurances of anonymity, and explained to interviewees they would not receive any monetary or other incentives for speaking with Human Rights Watch. We also received interviewees’ consent to describe their experiences after informing them that they could terminate the interview at any point. All interviews were in Arabic. Individual names have been changed and other identifying details removed to protect their identity and security.

To gain a broader picture of the treatment of Palestinian refugees from Syria Human Rights Watch also interviewed staff of humanitarian organizations and surveyed their reports. Human Rights Watch found that the issues raised by Palestinians we interviewed appear to be representative of those confronting Palestinians from Syria more generally.

Human Rights Watch wrote to Jordanian Interior Minister Hussein al-Majali on May 5, 2014 requesting information on Jordan’s treatment of Palestinians from Syria, but did not receive a reply.

I. Background

Prior to the Syrian conflict, approximately 520,000 Palestinian refugees resided in Syria, some living in refugee camps and others in Syrian towns and cities, where they enjoyed many of the same rights as Syrian citizens, including access to government services. According to the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), the vast majority of Palestinian refugees fled to Syria in 1948 from northern Palestine, especially from the towns of Haifa, Jaffa, and Safed.[1] Over 100,000 others fled in 1967 from the Golan Heights after its occupation by Israel. Several thousand more Palestinians fled to Syria from Jordan following the Black September conflict there in 1970-71. A further wave of Palestinians fled to Syria from Lebanon in following Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982.[2] Some people in these later groups are not registered refugees with UNRWA in Syria, as UNRWA’s mandate is restricted to 1948 refugees and their descendants. However even those not registered with UNWRA were able to access some UNRWA services in Syria.[3]

Palestinians in Syria, like Syrians, have suffered greatly as a result of generalized violence and unlawful attacks by government forces and non-state armed groups. Like Syrians, they began seeking refuge in neighboring countries after the start of the conflict in 2011.

Palestinian refugee camps, including in Aleppo, Daraa, and the Yarmouk camp in south Damascus, have come under attack resulting in extensive civilian casualties and displacement. The Yarmouk camp, home to the largest Palestinian community in Syria before the start of the conflict, was besieged by government forces in December 2012, resulting in widespread malnutrition and in some cases death from starvation.[4] While some limited and intermittent aid has entered Yarmouk camp since then, the camp was still under siege at the time this report was published and residents who remained there were often unable to gain access to life-saving medical assistance and adequate food supplies. According to the UN’s 2014 Syrian Arab Republic Humanitarian Assistance Response Plan (SHARP), half of the 540,000 Palestinians currently residing in Syria have reportedly been displaced within Syria or outside its borders as a result of the conflict and almost the entire Palestinian population of Syria is in need of humanitarian assistance.[5] Palestinians in Syria have also been subject to arbitrary detention and torture by government forces and non-state armed groups.[6]

One Palestinian from the southern Damascus suburb of al-Hajr al-Aswad told Human Rights Watch in Amman that her elderly sister starved to death during the Syrian army’s siege of the Yarmouk Camp, and that two of her sons lived through the siege, one of whom later escaped to a different neighborhood in Damascus after losing 40 kilograms of his body weight. She said: “Al-Hajr al-Aswad is destroyed; everything we had is gone and there is fear everywhere in Syria.”[7]

Of the thousands Palestinians that flee to Jordan from Syria, many are UNRWA-registered refugees whose families originally fled to Syria in 1948. These Palestinians, prior to their flight from Syria, had received ID cards and travel documents issued by the General Administration for Palestine Arab Refugees (GAPAR), a Syrian government agency that administers services to registered Palestinian refugees in Syria.

Other Palestinians who have sought refuge in Jordan were originally displaced to Syria from Jordan in 1970-71 following the Black September fighting between Palestinian armed groups and the Jordanian army, or migrated to Syria after 1970 for other reasons. These Palestinians do not hold Syrian-government issued ID cards, but most had expired Jordanian passports or other Jordanian identity documents such as family books or birth certificates.[8] Some of these 1970-71 refugees also maintained an identity document issued by the Palestinian Liberation Organization mission in Damascus.[9]

II. Denial of Entry to Palestinians from Syria

Prior to April 2012, Jordanian authorities permitted at least 1,300 Palestinians fleeing from the conflict in Syria to enter the country, and applied to them the same procedures governing entry of Syrian nationals.[10] Authorities held all Syrians and Palestinians at temporary detention facilities, but allowed them to leave detention after they established their identity and passed a security screening, and once a Jordanian national had stepped forward to act as a guarantor or “bailer”.[11]

In April 2012, however, Jordan began denying entry to Palestinians, refusing to permit Palestinians to leave the temporary holding facilities for refugees through “bail-out” procedures, and forcibly deporting others.[12] In June 2012 Human Rights Watch interviewed 12 Palestinians, including women and children, whom the Jordanian authorities had detained in refugee holding facilities for months with no possibility of release. Like thousands of Syrians, they had entered Jordan without passing through an official border post, but unlike the Syrians, they had been singled out for special treatment. Three of the men said they or their brothers had been forcibly returned to Syria, while six men, three of them with families including small children, said they had been taken to the border and threatened with deportation although they were then allowed to stay in Jordan.[13]

In July 2012 a Ministry of Interior official refused to confirm the existence of a non-admittance policy for Palestinians in a private meeting with Human Rights Watch, but in January 2013 Prime Minister Ensour made the policy public in an interview with al-Hayat.[14] He said, “Jordan has made a clear and explicit sovereign decision not to allow the crossing to Jordan by our Palestinian brothers who hold Syrian documents.”[15]

Fayez Tarawneh, chief of Jordan’s royal court and prime minister between May and October 2012, told Human Rights Watch in a meeting in June 2013 that Jordan would not reverse its non-admittance policy for Palestinians from Syria. He said that if Jordan permitted their entry, hundreds of thousands of Palestinians would seek permanent refuge in Jordan, thereby permanently altering Jordan’s demographic balance by increasing the number of people in the country of Palestinian origin. This imbalance, he argued, would negatively affect the security of the country.[16]

Despite Ensour’s statement to al-Hayat, Jordan’s restrictions were not limited to Palestinians with Syrian documents but included Palestinians living in Syria with Jordanian identification papers. As explained above, these included descendants of Jordanian citizens of Palestinian origin, some of whom fled to Syria in 1970-71 following the Black September fighting between Palestinian armed groups and the Jordanian army.

Human Rights Watch documented four cases of Palestinian families whose members included Jordanian citizens. Three of the four families confirmed that a family member had participated in Black September on the side of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), though only one contained a family member still living who had actually been involved in the hostilities in 1970. Two families stated that they had successfully renewed Jordanian identity documents over the years at the Jordanian embassy in Damascus. Of the four families, two said that Jordanian authorities allowed them to enter Jordan in mid-2012 using expired Jordanian identity documents, including passports, or other forms of identification such as Jordanian-issued birth certificates and passports.[17] A third family holding expired Jordanian documents was turned away at the border in December 2012, but entered later with the help of a smuggler. The other family said Jordanian authorities permitted their entry using Jordanian passports in early 2013 in contrast to its pushbacks of other Palestinians.[18]

The total number of Palestinian asylum seekers rejected at the Syrian-Jordanian border since the fighting began in Syria is not known. No international agency has full access to unofficial border crossings where the Jordanian military first encounters asylum seekers.[19] Many of the Syrian and Palestinian refugees Human Rights Watch interviewed in Jordan in February 2013 said that they saw Palestinians, single Syrian men, and undocumented people being refused entry at the border or forcibly returned after initial screening at a police center near the northern city of Mafraq.[20]

Basma, a Palestinian from Yarmouk refugee camp, attempted to seek refuge in Jordan with her husband and three children in December 2012, several days after the Syrian army began intense shelling of Yarmouk camp. She said that Jordanian military officers there refused their entry even though they carried valid Jordanian birth certificates and a Jordanian family book:

When we crossed the border some Jordanian army officers tried to help us, but then others came and refused to let us enter. They said, “You are Palestinians, you aren’t allowed to enter.” Then they took us in a bus and dropped us on the Syrian side of the border at 2 a.m. The Free Syrian Army [an armed opposition group] took us and put us in a mosque in Daraa.[21]

Another Palestinian, Faris, also from Yarmouk camp, tried to enter with his wife and four children in October 2012, shortly before the launch of a military offensive in the camp. He said:

When we left we went to [the Syrian border village] Nassib, the Free Syrian Army saw us and said we cannot enter. We entered anyway and when we got to Jordan we showed them our Palestinian-Syrian ID cards and they put us aside … then an officer said he would take us back to Syria. The officer then told me very quietly “go back and change your identity card” and I said ok. We went back with the Free Syrian Army.[22]

In spite of Jordan’s ban on entry to Palestinians, over 14,000 have entered Jordan since the start of the conflict, seeking support from the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA).[23] Of these at least 12,700 reported entering after Jordan began denying entry to Palestinians in April 2012.

[24]

Despite the ban on their entry, Palestinians from Syria continued to try to enter Jordan to escape the fighting in Syria by going through unofficial border crossings and relying on smugglers. Palestinians interviewed by Human Rights Watch explained how they circumvented Jordan’s ban on Palestinian entry from Syria.

Omar, a Palestinian from Daraa city, told Human Rights Watch that his wife, a Syrian, entered Jordan in May 2012 at an unofficial border crossing. She claimed her four children were Syrian citizens even though she had no documentation, and Jordanian authorities allowed them to enter, register with UNHCR, and go to the Zaatari refugee camp.[25] Omar himself followed a year later in May 2013, and hired a Syrian smuggler to take him across the border for a fee of 250 Jordanian Dinars ($343), after which he reunited with his wife and children.[26] Omar worries that if discovered, Jordan’s security forces will return him to Daraa, where he says Syria’s Military Intelligence tortured him for 15 days in 2012 following the assassination of a military general near his home. He said: “I am worried that if the Jordanians catch me they will send me back to the regime, not the Free Syrian Army. I don’t want to get arrested again by the regime.”[27]

Samir, another Palestinian from Daraa city, said that he crossed the border with his Syrian wife and three children after his wife was injured by a sniper. To cross the border he used a Syrian passport belonging to another person. He registered with UNHCR, but was unable to continue posing as a Syrian after the Syrian man who owned the passport himself crossed the border and presented himself to UNHCR.[28] As such Samir has no document to justify his presence if stopped by authorities. He said: “A lot of the Syrians here in this area know me from Daraa, they know I’m Palestinian, I try to avoid them as much as I can ... because of my situation I can’t work, so I stay home all day with my wife and kids…”[29]

Abdullah, a 47-year old Palestinian from Damascus, said that he entered Jordan in May 2014 to reunite with family members. He first travelled to the Syrian border village of Tel Shehab seeking out a smuggler to take him across the border. After finding a smuggler for a fee of 750 Jordanian Dinars ($1,060), he explained what happened during his crossing:

The smuggler took me and five Syrians by car for about an hour to the border. After we arrived to an area with gardens, the smuggler let us out and told us to walk down a dirt path, saying that we would find a Jordanian car waiting for us on the other side of the border. We walked about 700 meters and then arrived to an area with two sets of dunes that marked the border. As we were crossing the Jordanian army started firing at us. We all laid down flat on the ground to avoid the gun fire. After some moments two trucks with army officers came to us, before we knew what was happening an army officer shot five of us in our legs. We weren’t trying to flee.[30]

The man required medical treatment for a bullet wound in his left lower leg. He said that despite his experience he would try to return again if deported back to Syria, arguing that if a Syrian regime soldier or official noticed his leg wound he would suspect him of being a Free Syrian Army soldier and execute him.[31]

III. Arrest and Deportation of Palestinians from Syria

Prior to April 2012, approximately 1,300 Palestinians entered Jordan, most of whom were Jordanian citizens, or non-citizens whom the authorities detained upon entry at temporary refugee holding facilities and allowed to leave once they found a Jordanian guarantor to bail them out. As far as Human Rights Watch knows, the Jordanian authorities have not subsequently deported any of those Palestinians.

After April 2012 Jordan began pushbacks of Palestinian refugees at the Syrian border and halted the possibility of bailouts for Palestinians from temporary refugee holding facilities. According to UNRWA, as of April 2014 Jordan was detaining approximately 180 Palestinians at Cyber City, most of them since 2012.[32]Other than short periods of leave granted every two to three weeks to visit their family members in Jordanian cities, Palestinians living in Cyber City can only leave the camp to return to Syria.

The thousands of non-Jordanian Palestinians who entered irregularly after April 2012, all without valid bailout certificates, are at risk of arrest and deportation to Syria if discovered by Jordanian authorities.

Palestinians interviewed by Human Rights Watch described various ways in which police and intelligence services discover and arrest Palestinians from Syria in Jordan, including through raids, inspections for those working illegally, and when Palestinians attempt to renew documents or seek government services.[33] Following arrest they said authorities held them in police stations or General Intelligence Directorate (GID) facilities for several days and then put them on buses to Cyber City or deported them to Syria at unofficial border crossings to areas controlled by Syrian opposition groups.[34] In no cases did authorities grant Palestinians the right to challenge their deportations, though UNRWA, which monitors and responds to protection issues regarding Palestinians, intervenes with authorities on behalf of Palestinians when consent is provided.[35] While held in detention, Palestinians were generally permitted a phone call to their family members to notify them of their impending deportation.

According to the non-governmental group SNAP, over 100 Palestinians have been forcibly returned by Jordanian authorities since 2013, “with a notable increase occurring in early 2014.”[36] In its February 2013 Syria Crisis Response Annual Report, UNRWA noted that the agency has documented numerous cases of forcible return, including of women and children.

In January 2013, Human Rights Watch documented eight credible reports of Palestinians from Syria being forcibly returned from Jordan.[37] In April 2014, Human Rights Watch documented another eight cases, seven men and one woman, of Palestinians deported by Jordan to Syria between July 2013 and February 2014.

Following deportation to Syria, Palestinians face difficulties moving into the country from border areas back to their homes. Human Rights Watch documented the cases of seven Palestinian families who said that their homes in Daraa or in southern Damascus had been damaged or destroyed as a result of shelling or fighting.[38] Human Rights Watch documented six cases of Palestinians whom Jordanian authorities deported after confiscating all of their identity documents. Without documents they were unable to cross checkpoints within Syria into government-controlled territory to approach Daraa’s UNRWA office to seek identity documents and humanitarian aid.[39] One family of five siblings whom Human Rights Watch spoke to by phone had been stuck in a Syrian border town under the control of opposition groups since late February 2014, unable to move further into Syria without identity documents.[40]

At least one man, Mahmoud Murjan, died after Jordanian authorities deported him and his wife and two young children from Cyber City to Syria in September 2012. According to an individual with knowledge of the case, Murjan was a Palestinian whom the guards at Cyber City also regarded as a troublemaker. There is controversy about the circumstances of his return to Syria. One interviewee said that he had spoken to Murjan on the phone as he was being returned, and that Murjan said that he did not want to return and that the authorities who took him to the border threatened to shoot him if he did not continue walking back into Syria.[41]

Murjan was killed in Syria 20 days later, on October 15, after armed men came into his house, shot him in the leg in the presence of his wife and children, and pulled him into a car. Later that day, his body, showing marks of torture, was dumped on the street in front of his father’s house.[42]

Basma, a Palestinian from Yarmouk, said that on the evening of July 8, 2013, five months after her family entered Jordan using a smuggler, a group of 20 Jordanian uniformed police and plainclothes intelligence officers stormed her Amman home. The police arrested her husband, and after holding him for 15 days at a General Intelligence Directorate (GID) detention facility in Amman, deported him. She said, “Several days after they arrested him he called me from jail to say they that are taking him to Syria. He told me they only asked him questions the first day he was arrested; they left him alone the rest of the time.”[43] After his deportation, her husband departed Syria again and claimed asylum in a third country while she and her family remain separated from him in Amman.

Basma said that like her husband she and her three children are also undocumented, and she does not know why authorities only arrested and deported her husband since all were present in the house when the police entered. She believes that his deportation may be related to his membership in the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). She said, “I think someone informed on him [i.e. his membership in the PLO], because the police also took his cousin, his nephew, and another person on the same night, all from different houses.”[44] She told Human Rights Watch she fears that she or her children may also be deported to Syria despite being spared during the raid on her home. She said, “We are not comfortable here, my daughter is going to college but it is very risky. It’s very dangerous for us to move around. They aren’t sparing boys or girls … We don’t want residency documents or passports or anything else. All we want is just to be here in peace.”[45]

Sana, an elderly Palestinian from al-Muzairib, a majority-Palestinian village several kilometers northwest of Daraa city in Syria, t0ld Human Rights Watch that Jordanian authorities deported her son-in-law Kamal and his brother, both also Palestinians from al-Muzairib, after catching Kamal working illegally, selling vegetables from a cart in Irbid. She said both brothers had entered Jordan with their Syrian wives using forged Syrian family books and registered with UNHCR under false names. Two days after learning that Mohammed had been arrested, Sana, who is a Jordanian citizen, went to the police station to find out what happened.[46] She said, “I went to the police station and they told me to come back the next day, they said they would find a solution for us. Kamal called me an hour later from Syria.”[47]

She later spoke to Kamal in Syria, who informed her that Jordanian police held him for two days inside an Irbid police station, and that officers there beat him, demanding that he reveal the identities of other Palestinians in the area. After confirming to officers the presence of his brother in Jordan, police drove Kamal to the market to identify him. Authorities deported them together, bringing them to an unofficial border crossing to an opposition-controlled area and ordering them across, she said, leaving their wives and three children behind in Irbid.[48]

In a few cases, instead of deporting Palestinians to Syria, Jordanian authorities instead sent them to the holding facility at Cyber City. Human Rights Watch spoke by phone with two Palestinians currently held in Cyber City. Authorities place one of these men along with his three siblings in Cyber City instead of deporting them to Syria after the intervention of Jordanian family members with the security services.[49] In the other case, a Palestinian man arrested and sent to Cyber City said he did not know why authorities chose not to deport him.[50]

In all cases of deportation documented by Human Rights Watch, Jordanian authorities separated Palestinian men from children, wives, parents, or other family members left behind in Jordan, depriving family members of a primary source of income in some cases.

Arrest and Deportation of Palestinians with Jordanian identification papers

Arrests and deportations were not limited to Palestinians registered in Syria but also extended to Palestinians from Syria who had Jordanian identification papers.[51]

Human Rights Watch spoke with members of four families who had Jordanian identity documents when they entered, including expired passports, Jordanian family books, and Jordanian birth certificates. Three of the four said that they or their parents had originally fled to Syria in 1970-71 during the Black September conflict, and that relatives fought on the side of Palestinian armed groups against the Jordanian army. In all cases it was unclear whether Jordanian authorities had removed their citizenship prior to their entering Jordan or if the decision was made later when they approached the Civil Status Department in Jordan. Officials did not give any Palestinians Human Rights Watch interviewed an official reason for the removal of their citizenship.

Rami, 24, a Palestinian from Daraa city, told Human Rights Watch that he and his family members arrived in Jordan in 2012 after fighting intensified in Daraa. They entered using Jordanian birth certificates and a copy of their father’s expired Jordanian passport. He said his father left Jordan in 1969 to study in Moscow, but did not return to Jordan after completing his studies, instead settling in Daraa city with his wife, who is a Palestinian from Lebanon. He did not believe his father had any involvement in the events of Black September:[52]

When we entered Jordan in 2012, [my sister], [my brother] and I went to the Civil Status Department to apply for new Jordanian ID cards … We wanted to get a national ID number. This was refused, and our birth certificates, along with our father’s passport, were confiscated. We were then taken to Cyber City, where we have been for one year and two months. All we have now is a photocopy of our father’s passport.[53]

Rami’s mother said they were not taken to Syria because of a last minute intervention by Jordanian members of the family who have connections inside the General Intelligence Directorate (GID).[54] “My children did nothing wrong,” she said. “They just wanted a passport.”[55]

Salim, a Palestinian man detained in Cyber City since early 2013, came to Jordan from the southern Damascus suburb of al-Hajr al-Aswad. He told Human Rights Watch that Jordanian officials likely removed his citizenship in 2009, when the Jordanian embassy in Damascus refused to renew his passport. He said that he fought with PLO forces in Jordan in 1970, and withdrew with his family to Syria following the battle, but had been able to renew his passport until 2009.[56]

Salim said that he entered with his wife and two adult daughters in July 2012 using a Jordanian family book and ID card. He said that seven months later, when he decided to try to renew his passport at the Civil Status Department, employees there first told him the department would grant him a passport, but then later told him he needed approval from the GID. When he met the GID, however, officers detained him and placed him in Cyber City.[57] Officials at Cyber City allow him to visit his family in Amman for three days every two weeks, but informed him that they would disallow these visits if he returns late.[58]

|

Jordan’s refoulement of Nidal to Syria Nidal, 35, told Human Rights Watch by phone that Jordanian GID officers deported him along with three of his brothers and one sister after they attempted to renew Jordanian passports at the Civil Status Office in Amman in late February 2014. At the time Human Rights Watch spoke to Nidal, he and his siblings had sought refuge at a mosque in the Syrian border town of Nassib, afraid to go further in Syria because they had no document to confirm their identity at a checkpoint. Human Rights Watch also interviewed Nidal’s wife, a Syrian, and his mother, a Jordanian citizen, in Amman. Nidal’s mother told Human Rights Watch she and four of her children came to Jordan in stages in 2012 and 2013 with their families from the Eastern Ghouta area of the Damascus suburbs. She said they all entered Jordan without a problem using expired Jordanian passports but that she had one son, Ahmad, who could not leave because he did not have Jordanian documents, and that he was killed in Syria by a bomb.[59] Nidal’s mother said that she and her late husband, who was a member of the PLO during the 1960s, had been born in Jordan but fled to Syria in 1970 after Black September. She and her family had been able to maintain their Jordanian passports, however, renewing them every five years at the Jordanian embassy in Damascus. She said that their passports had expired after the outbreak of violence in 2011: “Our passports expired during the war, the embassy kept postponing the renewal, and eventually we couldn’t make it from our house into central Damascus because the roads weren’t safe.”[60] Nidal said that he and his siblings went to the Civil Status and Passports Departmentin Amman in early 2014 to renew their passports, and that the employees there told them to go to the GID headquarters to sort out their passports. When they went in, officers there quickly detained them. He said, “Suddenly we were blindfolded and handcuffed. We stayed at the intelligence building from 3 p.m. to 8 p.m. and no one talked to us.”[61] Officers then interrogated each of them one by one, he said, asking questions about his employment, whether he belonged to any political party or armed group, and about his father, who died in Syria in 2010. Afterwards, he said, they took his fingerprints and stamped them on 12-15 pieces of paper, but officers didn’t allow him to read the writing on the papers.[62] The next day officers took him and his siblings back to Syria in a bus, dropping them at the border across from the Syrian town of Nassib.[63] Nidal’s mother said she made inquiries with the Civil Status Department, trying to understand why her children had been taken and deported: “I asked them, ‘Is it because my husband was in the PLO?’ Because he left the PLO, and by the end of his life he was a poor man selling produce from a truck, but they told me, ‘No, they were taken because they didn’t maintain their citizenship for three years, so they must not have wanted the citizenship.’”[64] After one month and a half living in Nassib, Nidal was hit with shrapnel in his left thigh as Syrian warplanes bombed Free Syrian Army (FSA) positions in the area. An FSA doctor, he said, managed to sneak him back into Jordan using a fake Syrian name to get medical treatment for his wound. He stayed there in the hospital for 16 days, he said, until doctors decided to transfer him to another facility in Zaatari camp in early April for further treatment. At the Jordanian refugee screening facility in Raba` Sahran, however, officers discovered his identity and immediately deported him again via Nassib, despite his injury. “When I got there,” he said, “I knew why I was forbidden to stay in Jordan. An officer there told me: ‘Remember the events of 1970.’ … And I told him my father was granted amnesty and entered Jordan several times since then, most recently in 1998, but he said, ‘You are not a Jordanian, you are a Palestinian.’”[65] Nidal was nine years old in 1970. Nidal said that his wound continues to re-open and that there is no medical care in Nassib. He said that he and his family are stuck in a mosque there because they do not have IDs to confirm their identity at government checkpoints. He said, “Now I can’t walk without a walking stick. I don’t have any kind of ID. I need my ID back so I can move further into Syria at least. I’m completely lost.”[66] |

IV. Lack of Protection While Residing in Jordan

All Palestinians who have escaped to Jordan from Syria are in a precarious situation. Either they are undocumented, or they have secured UNHCR asylum seeker certificates by posing as Syrians, or they are Jordanian citizens or descendants of Jordanian citizens who may be at risk of withdrawal of citizenship and deportation.

Undocumented Palestinians from Syria inside Jordan cannot call on the protection of the Jordanian government when facing exploitation or other abuses because of the risk of arrest and deportation. Like most Syrian refugees in Jordan, Palestinians cannot work legally and are dependent on humanitarian assistance.[67] Unlike Syrians, however, Palestinians cannot live in official refugee camps and are forced to rent apartments in Jordanian towns and cities.

The 2014 Syria Regional Response Plan’s section on Jordan, which frames policy dialogue and operational coordination between aid agencies working with refugees, excludes Palestinians.[68] As such, UNRWA is largely left alone in providing humanitarian assistance and offering access to education and health services to Palestinians, regardless of their status in the country.[69]

Two Palestinians told Human Rights Watch their undocumented status had prevented them from seeking protection or redress for abuses ranging from economic exploitation to street harassment.

Mahmoud, a Palestinian from Yarmouk Camp living in Irbid with his wife and four children, said that after entering Jordan on a fake Syrian ID, a relative, who is a Jordanian citizen, sponsored him and his family so that they would be able to reside outside of the Zaatari refugee camp.[70] After bailing him out, his relative asked Mahmoud, a professional painter, to do some jobs in the area, but refused to pay him for his work. “When I asked for payment, he told me that if I wanted any money I should find another person to be my sponsor,” Mahmoud told Human Rights Watch.[71]

Mahmoud said that he did not receive full payment for many other paint jobs he had performed for others in Irbid, often getting less than half of the agreed-upon fee. Due to his need to use a fake Syrian ID in Jordan, Mahmoud fears pursuing legal action against his clients.[72]

Another Palestinian, Omar, living in Ramtha, said his 17-year-0ld daughter faced harassment from men while walking to school but that they could not report it because he feared being discovered by the police:

We had a problem with a school in Ramtha, as my daughter [posing as a Syrian] and other Syrian girls were going into the school building and some local boys would come and harass them … one time the boys went inside the school itself and tried to grab the girls’ books so they could learn their names, and she and her friends had to run and hide from them in a perfume store. The owner yelled at the kids, but we couldn’t tell the police.[73]

All of the Palestinian families with whom Human Rights Watch met were living in rented apartments, with monthly rents ranging between 150-250 Jordanian Dinars ($212-$353). Every family said they received occasional monetary support from UNRWA, which differed depending on family size, but in order to pay rent they were forced to supplement this support by having family members work illegally.[74] At least four out of the twelve families interviewed by Human Rights Watch reported that they had fallen behind in their rent payments and did not know how they would be able to find the money to pay, especially families whose male members had been deported to Syria. “I am now behind two months on my rent,” said Sana, whose son-in-law was deported with his brother in early 2014. “My landlord lives across the street, so sometimes I leave from a different door so he won’t see me.”[75]

International humanitarian workers told Human Rights Watch that they feared an increase in discovery, arrest, and deportation of Palestinians, particularly Palestinians posing as Syrians, as a result of Jordan’s introduction of a biometric verification procedure for new refugees arriving from Syria, and re-verification of Syrians living in Zaatari camp and in urban communities.[76] The new procedure requires refugees to give iris scans to UNHCR and to governmental authorities in order to receive a Ministry of Interior service card, which refugees use to access food vouchers and other services.[77] Authorities would likely be able to discover their forged documents under the new procedures. Humanitarian workers also said they feared that those refugees who do not report for re-verification procedures would automatically come under suspicion as potential Palestinians posing as Syrians and be arrested and deported as a result.[78]

V. Jordan’s Removal of Citizenship from Citizens of Palestinian Origin

Jordanian law prescribes narrow circumstances for denaturalizing a citizen. Entering the “service of an enemy state,” or the “military,” or “civil service of a foreign state” are grounds for revoking citizenship. However, in the case of foreign military and civil service, Jordan must give the person concerned warning to leave the other state’s service and he or she must have refused to do so before losing Jordanian citizenship.[79] Furthermore, Jordanian law does not permit authorities to withdraw Jordanian citizenship from the children as a consequence of withdrawing it from their Palestinian-origin father.[80]

Jordanian citizens affected by removal of citizenship have not learned they had been stripped of their citizenship from any official notice, but rather during routine procedures such as renewing a passport or driver's license, or registering a marriage or the birth of a child at the Civil Status Department.[81]

Four Palestinian families from Syria told Human Rights Watch that they fled to Jordan because they believed their Jordanian-issued identity documents might allow them to legally reside in Jordan and enjoy, or in some cases reacquire, citizenship rights. Of these, members of three families, 10 individuals, attempted to renew Jordanian identity documents with the Civil Status Department, only to find out that their citizenship had been revoked, and authorities then detained them and deported them or placed them in Cyber City. Of these 10 individuals, only one man claimed that he fought with the PLO against Jordanian government forces during the Black September fighting of 1970-71.[82]

Some Jordanian citizens of Palestinian origin who fled to Syria following the Black September conflict were not eligible to register with UNRWA in Syria or with the General Administration for Palestine Arab Refugees (GAPAR), the official Syrian government agency that administers services to registered Palestinian refugees in Syria, including issuing Syrian travel documents and ID cards for Palestinians in Syria.[83] Rather, Palestinians in Syria with Jordanian identification documents, including expired passports, family books, and birth certificates, were able to obtain 10-year residency permits directly from the Syrian Interior Ministry, but unlike other Palestinians they had to apply for work permits and were restricted from working in the public sector.[84] Members of two Palestinian families said that in Syria they carried an identity document issued by the PLO mission in Damascus.[85]

Human Rights Watch interviewed members of four families from Syria who had family members refused renewal of ID cards and passports by the Jordanian Civil Status Department. It is unclear from those interviews precisely when Jordanian authorities stripped these Jordanian citizens of Palestinian origin living in Syria of their citizenship. While one family reported that they were able to renew documents at the Jordanian embassy in Damascus until at least 2011, and another family until 2009, two others reported that passport renewal requests had been denied at the embassy as early as 1981.[86]

In addition to the risk of deportation, denaturalized Jordanians of Palestinian origin from Syria find it difficult to exercise other basic rights in Jordan, including obtaining health care, finding work, owning property, traveling, and sending their children to public schools and universities.[87] With no other country to turn to, these Jordanians have become stateless Palestinians, in many cases for a second time after 1948.

Human Rights Watch wrote to Jordanian Interior Minister Hussein al-Majali on May 5, 2014, asking how many Palestinian-origin Jordanian citizens from Syria had been subjected to removal of citizenship, but did not receive a reply.

VI. Shrinking Space: Regional Push Backs of Palestinians from Syria

Jordan is not the only country in the region that denies safe haven to Palestinians fleeing the violence in Syria or restricts their entry. According to the March 2014 SNAP report:

In 2013, [Palestinians from Syria] faced increasingly targeted restrictions in seeking entry and asylum, as well as escalating hostility in host countries and communities, particularly in Egypt, Jordan, and Lebanon. This has caused many [Palestinians from Syria] to take greater risk in reaching Europe via land and sea routes with smugglers.[88]

Though Iraq has placed no formal restrictions on Palestinian entry per se, in practice Iraqi authorities have blocked entry to virtually all asylum seekers attempting to enter through central Iraq’s border crossings with Syria since October 2012.[89] According to SNAP, there are no official figures for the number of Palestinians who have entered Iraq from Syria, but that “[t]here are likely … Palestinians who had sought refuge in Syria between 2006 and 2008 who have now returned to Iraq due to the escalation of the Syrian conflict.”[90]

Since the beginning of the Syrian crisis, of the 70,000 Palestinians estimated to have fled Syria at least 53,000 sought refuge in Lebanon.[91] Though the Lebanese government did not announce any formal restrictions on Palestinians entering Lebanon from Syria until May 2014, it barred entry to some Palestinians beginning in August 2013.[92] Furthermore Lebanon has long subjected Palestinians to a separate and more restrictive visa policy than that applied to Syrians.[93] On May 8, however, the Lebanese Ministry of Interior announced that authorities would stop issuing visas to Palestinians at the border, with some specific exceptions, and that instead Palestinians from Syria would need to apply in advance for a visa to enter the country.[94] The announcement did not say whether authorities would apply conditions or restrictions to visa requests by Palestinians. Under the new policy the Ministry also announced that Palestinians from Syria in Lebanon would no longer be able to renew or extend visas that had previously been obtained automatically at the border

On May 4, the Lebanese government forcibly returned about three dozen Palestinians to Syria via the Masnaa border crossing. The decision to deport the men followed their arrest at Beirut airport on May 3 for allegedly attempting to leave the country using fraudulent visas. [95]

Of Syria’s neighbors, only Turkey allows Palestinians to freely enter and has reportedly agreed to issue residency permits that will allow them to live, work, and study legally in the country.[96] By April 2014 at least 1,600 Palestinians had entered Turkey and registered with UNHCR.[97]

Due to regional pushbacks and inability to legally reside in most surrounding countries, many Palestinians from Syria are taking risks to escape the violence, including by attempting to smuggle themselves to Europe by land or sea.

In Egypt, where an estimated 6,000 Palestinians from Syria have sought refuge, Palestinians and Syrians must acquire a pre-approved visa to enter the country.[98] By late 2013 the government had detained at least 400 Palestinians from Syria caught trying to migrate to Europe on smugglers’ boats. Palestinians interviewed by Human Rights Watch at police stations said that Egyptian authorities told them that their only alternative to indefinite detention in Egypt was to go to Lebanon or return to war-torn Syria.[99] Palestinians in Egypt are especially vulnerable because Egyptian policy prevents them from seeking protection from UNHCR, and Egypt is outside UNRWA’s fields of operation.[100]

The wife of one Palestinian man whom Jordanian authorities deported back to Syria in 2013 told Human Rights Watch he had later managed to smuggle himself to Europe via Turkey for a fee of 7,000 Euros ($9,525), but that he had injured his back while traveling a mountain route.[101]

Neighboring countries must respect the rights of Palestinian refugees to seek safety and asylum outside Syria as long as they face insecurity and persecution there. The burden of providing safety and asylum should not fall solely on neighboring countries (Jordan and Lebanon being the preferred countries of flight for the Palestinians), but should be shared by countries in the region and beyond. Israel too should not wait for a resolution of the broader Palestinian refugee issue but instead permit Palestinian refugees from Syria to return to areas now administered by Palestinian authorities.

Other countries outside the region should also participate in sharing the burden: they should provide financial assistance to countries that take Palestinian refugees from Syria and consider accepting vulnerable Palestinian refugees for temporary humanitarian resettlement without prejudice to their right of return.

The PLO and the Arab League have rejected in principle and actively discouraged in practice local integration or third-country resettlement of Palestinian refugees. Their view is that local integration or resettlement would negate the right to return of the resettled refugees.[102] While states might be reluctant to offer third-country resettlement because of the PLO and Arab League position against it, the dire situation of Palestinians fleeing Syria cannot be ignored. One avenue would be to model third-country Palestinian resettlement of Syrian Palestinians on the Kosovar Humanitarian Evacuation Program in which resettlement offers were provided on a temporary basis rather than as a durable solution.[103] Under such an arrangement, Palestinian refugees would not have to forfeit their right of return by accepting an offer of temporary resettlement.

VII. Legal Standards

Nonrefoulement in international refugee law is the principle that a state cannot return a refugee or asylum seeker to a country where there is a risk that his or her life or freedom would be threatened on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion. The principle is recognized as customary international law, and is also guaranteed through the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol. Refugee status is declaratory, that is it is derived from the recognition that a person meets the refugee definition, rather than a status that is conferred. As such, the fundamental principles of refugee protection apply equally to asylum seekers who have not yet been formally recognized as refugees.

Although not a party to the 1951 Refugee Convention or its 1967 Protocol, Jordan is nevertheless bound by customary international law not to return refugees to a place where their lives or freedom would be threatened. The Executive Committee of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR ExCom), of which Jordan is a member, adopted Conclusion 25 in 1982, declaring that “the principle of nonrefoulement ... was progressively acquiring the character of a peremptory rule of international law.”[104] A peremptory norm is one that is so fundamental that it is binding on all states, regardless of their practice or endorsement.

A state’s nonrefoulement obligation applies both on its territory and at its borders. In its October 2004 meeting, UNHCR ExCom issued Conclusion 99, which calls on states to ensure “full respect for the fundamental principle of nonrefoulement, including non-rejection at frontiers without access to fair and effective procedures for determining status and protection needs.”[105] Fair and effective procedures for determining status and protection needs are currently lacking at the border for arrivals from Syria in Jordan, and the massive numbers arriving make individualized refugee status determinations unfeasible for the time being.

UNHCR characterizes the Syrian situation as a “massive refugee exodus.”[106] UNHCR ExCom’s Conclusion 22 of 1981 on the Protection of Asylum Seekers in Situations of Large-scale Influx says:

In situations of large-scale influx, asylum seekers should be admitted to the State in which they first seek refuge and if that State is unable to admit them on a durable basis, it should always admit them at least on a temporary basis...They should be admitted without any discrimination as to race, religion, political opinion, nationality, country of origin or physical incapacity. In all cases the fundamental principle of nonrefoulement – including non-rejection at the frontier – must be scrupulously observed.[107]

The practical consequence of the application of the principle of nonrefoulement at the border requires Jordan to allow asylum seekers who are part of a mass influx fleeing widespread human rights abuses and generalized violence to enter the country, at least temporarily, to ensure that no one is returned to persecution.

In addition to its customary international law obligations, Jordan is a party to the Convention Against Torture,the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the Convention on the Rights of the Child, all of which contain nonrefoulement obligations, where there is a real risk that returning an individual would lead to a violation of a fundamental human rights such as freedom from torture.[108] Moreover, the government of Jordan has repeatedly agreed to uphold its obligation not to return asylum seekers. In the Memorandum of Understanding Jordan signed with UNHCR in April 1998, it agreed:

In order to safeguard the asylum institution in Jordan and to enable UNHCR to act within its mandate ... it was agreed ... that the principle of nonrefoulement should be respected that no refugee seeking asylum in Jordan will be returned to a country where his life or freedom could be threatened because of his race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.[109]

When Jordan presented its candidacy to the UN Human Rights Council on April 20, 2006, it formally provided the United Nations with its pledges and commitments to promote and protect human rights. It said:

Over the last decades, the country has given shelter and protection to many waves of refugees; Jordan, as a long-standing host country, reiterates its commitment to fulfilling its obligations in accordance with the principles of international refugee law including those which are peremptory as well as international human rights law.[110]

Jordan reiterated this commitment in March 2012 before the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, where the Jordanian delegate is reported as saying that “although his country was not a signatory to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, it had always recognized and upheld the peremptory norms of international refugee law, notably the principle of non-refoulement.”[111]

Jordan’s statements formally recognize that refugee protection is an obligation, and that it is committed to fulfilling this obligation. For refugees, the most fundamental of these norms is the principle of nonrefoulement.

Jordan claims that its discriminatory treatment of Palestinians from Syria is necessary to preserve national security, yet it is plain that they are fleeing the same wartime conditions as other residents of Syria. In situations of mass influx, screening for refugee status may be impracticable, but UNHCR Excom’s Conclusion Number 22 states that asylum seekers should be admitted and protected at least on a temporary basis, that their admission should be without discrimination with regard to their national origin, and that the principle of nonrefoulement should be scrupulously observed.[112]

There is no valid basis in international refugee law to turn back refugees simply on the basis of their ethnic or national origin. Individuals may be excluded from refugee status for having committed a war crime, a crime against peace, or a crime against humanity.[113] They may also be excluded from refugee status for having committed a serious non-political crime outside the country of their refuge.[114] However, exclusions on these bases must be established individually after a person has been recognized as otherwise qualifying for refugee status. A statement of criminal status cannot be imputed to any group as a whole on the basis of historical circumstances or past political affiliation. In any event, it is doubtful that such exclusions apply to many, if any, Palestinians seeking entry from Syria.

Recognized refugees may also be denied protection from refoulement, but in very narrow circumstances.[115] Where, after admission to the country of refuge, a refugee is convicted by a final judgment of a particularly serious crime and is deemed to constitute a danger to the community, refoulement on Refugee Convention grounds may be legally permissible.[116] However, UNHCR has advised that this exception would need to be narrowly construed, and confined to situations where refoulement is the last resort in the face of a serious danger to the country, and where the risks to the host community outweigh the risks of persecution on return.[117] So far, Human Rights Watch is unaware of any case where a Palestinian fleeing Syria was returned or excluded because of a final judgment of a court of a particularly serious crime. Even were an individual found to have been convicted of participation in Black September, for example, it would be unlikely that some forty years later they would still present a serious danger to the community and a threat to the Jordanian state. Human rights law, in particular the Convention Against Torture, bars any government from returning anyone without exception to a place where they would be at risk of torture.[118] So, persons judged as being excluded from the protection of the Refugee Convention may still be protected by nonrefoulement guarantees of human rights law pertaining to torture, which are nonderogable.

Acknowledgements

This report was researched and written by a Human Rights Watch researcher. Nadim Houry, deputy director in the Middle East and North Africa division, Lama Fakih, researcher in the Middle East and North Africa division, Bill Frelick, Refugee Rights program director, and Tom Porteous, deputy program director, edited it. Dinah PoKempner, general counsel, provided legal review. Associate Sandy Elkhoury provided production and proofreading assistance. Grace Choi, publications director; Kathy Mills, publications specialist; Anna Lopriore, creative manager; and Fitzroy Hepkins, administrative manager, prepared the report for publication.

Thanks go to all the Palestinians who shared their stories with us.

Appendix

May 5, 2014

His Excellency Lt. Gen. Hussein al-Majali

Minister of Interior

Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan

Dear Mr. Minister,

I write you this letter to express our concerns over Jordan’s treatment of Palestinians from Syria who flee to Jordan to escape fighting in Syria, including Jordan’s refoulement of a number of Palestinians from within Jordanian territory. Human Rights Watch is also concerned about ongoing reports of the refusal to admit Palestinians arriving at the Syria-Jordan border, which also constitutes refoulement. This treatment differs from Jordan’s treatment of Syrian citizens, who despite some temporary land border closures, are admitted at Jordan’s borders and given the right to remain in the kingdom as asylum seekers.

In contravention of its obligations under international law, Jordan banned entry of all Palestinians from Syria in October 2012, denying safe refuge to those trying to flee Syria and rendering the presence of those already in the kingdom illegal, thereby increasing their vulnerability to exploitation, arrest, and deportation.

Human Rights Watch has received information from several sources that Jordan is not only denying entry to Palestinians from Syria but that police and security services have stepped up efforts to locate, arrest, and deport Palestinians who entered Jordan from Syria, returning scores of individuals since January 2013. The information we received indicates that a number of Palestinians sent back to Syria have been women, elderly, and children, some of them unaccompanied. Some of those returned to Syria were reportedly Jordanian citizens who were residing in Syria whom Jordanian authorities arbitrarily denationalized prior to their deportation.

In spite of the ban on entry to Jordan, by March 2014 at least 12,000 Palestinians from Syria had registered for support from the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), the agency reported.

According to a recent UNRWA statement, Palestinians from Syria who seek UNRWA support in Jordan have “exhausted their support mechanisms and are in dire need of assistance.” These Palestinians also face great difficulty registering births, accessing government services, and are at constant risk of deportation apparently without ability to challenge deportation orders.

In early 2013, Human Rights Watch documented eight cases in which Palestinian asylum seekers who had managed to enter Jordan faced refoulement back to dangerous conditions in Syria. In one such case, Mahmoud Murjan and his wife and children were forcibly returned from Cyber City, a detention facility in Jordan where refugees are held, to Syria on September 25, 2012. Murjan was arrested at his home in Syria 20 days after he was forcibly returned, and his body was later dumped on the street in front of his father’s house, showing bullet wounds and signs of torture, according to informed sources who asked not to be named.

Although not a party to the 1951 Refugee Convention or its 1967 Protocol, Jordan is nevertheless bound by customary international law not to return refugees to a place where their lives or freedom would be threatened. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees’ Executive Committee (UNHCR ExCom) – of which Jordan is a member –adopted Conclusion 25 of 1982, declaring that “the principle of nonrefoulement . . . was progressively acquiring the character of a peremptory rule of international law.” The state’s nonrefoulement obligation applies both on its territory and at its borders. The UNHCR characterizes the Syrian situation as a “massive refugee exodus.” Palestinians from Syria, like Syrians there, have suffered greatly as a result of generalized violence and unlawful attacks by both government forces and non-state armed groups. Palestinian refugee camps, including in Aleppo, Daraa, and the Yarmouk camp in south Damascus, have come under attack resulting in civilian fatalities. The Yarmouk camp, home to the largest Palestinian community in the country before the start of the conflict, was besieged by government forces in December 2012, resulting in widespread malnutrition and in some cases death from starvation. While some relief has entered Yarmouk since then, residents who remain there continue to be denied access to life-saving medical assistance and adequate food supplies. Half of the 540,000 Palestinians residing in Syria have reportedly been displaced as a result of the conflict. Palestinians in Syria have also been subject to arbitrary detention and torture by government forces.

UNHCR’s ExCom Conclusion 22 of 1981 on the Protection of Asylum Seekers in Situations of Large-scale Influx – such as that from Syria at present – says:

In situations of large-scale influx, asylum seekers should be admitted to the State in which they first seek refuge and if that State is unable to admit them on a durable basis, it should always admit them at least on a temporary basis...They should be admitted without any discrimination as to race, religion, political opinion, nationality, country of origin or physical incapacity. In all cases the fundamental principle of nonrefoulement – including non-rejection at the frontier – must be scrupulously observed.

In addition to its customary international law obligations, Jordan is a party

to the Convention Against Torture, the International Covenant on

Civil and Political Rights, and the Convention on the Rights of the Child,

all of which contain nonrefoulement obligations, where there is a real risk

that returning an individual would lead to a violation of a fundamental human

rights such as torture, or cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment. Moreover,

the government of Jordan has repeatedly agreed to uphold its obligation not to

return asylum seekers.

Jordan’s public statements formally recognize that refugee protection is an obligation, and that it is committed to fulfilling this obligation, which includes abiding by peremptory norms (that is, customary law). For refugees, the most fundamental of these norms is the principle of nonrefoulement.

In order to better understand and reflect Jordan’s treatment of Palestinians from Syria, we request answers to the following questions:

- What rules, practices, or procedures govern the decision to return Palestinian asylum seekers to Syria? How do these differ from rules, practices, or procedures that govern the treatment of non-Palestinian asylum seekers in Jordan?

- Which Jordanian government agency is responsible for ordering deportation of Palestinian asylum seekers from Jordan to Syria? Which Jordanian government agency carries out deportation of Palestinian asylum seekers?

- How many Palestinians has Jordan forcibly returned to Syria since 2011? Of these, how many were women, children, and elderly people?

- Do Jordanian authorities allow Palestinian asylum seekers to challenge their deportations? If so, what are the procedures or rules that govern challenging a deportation order in Jordan?

- How many Palestinians from Syria has Jordan stripped of Jordanian citizenship? On what basis did Jordan authorities remove the nationality of Palestinians residing in Syria?

- Which Jordanian government agency is responsible for removing the nationality of Palestinian asylum seekers? Did this agency receive approval from the prime minister to remove nationality of Palestinian asylum seekers?

- Which Jordanian government agency is responsible for unaccompanied children? How many unaccompanied children has Jordan deported? What procedures does the Jordanian government follow in cases of unaccompanied children?

We request that the ministry reply to these inquiries on or before May 19, 2013 so that we may include the information you provide in a report we are preparing regarding this issue.

We would be happy to meet you in Amman to discuss this issue directly. If there is a convenient time to meet, or should you have any questions, your staff can contact directly Jillian Slutzker, Middle East associate, at slutzkj@hrw.org or +1-202-612-4363.

We look forward to your response.

Sincerely,

Nadim Houry

Deputy Director

Middle East and North Africa division

Human Rights Watch

cc:

H.E. Dr. Fayez Tarawneh

Chief of the Royal Hashemite Court

Dr. Alia Hatoug Bouran

Ambassador of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan to the United States of America

[1]United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), “Where We Work - Syria,” http://www.unrwa.org/where-we-work (accessed May 25, 2014)

[2] Syria Needs Analysis Project, “Palestinians from Syria,” March 2014, http://www.acaps.org/reports/downloader/palestinians_from_syria_march_2014/77/syria (accessed May 17, 2014)

[3] Ibid.

[4] United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), “Syria Crisis response Annual Report 2013,” http://www.unrwa.org/sites/default/files/syria_crisis_response_annual_report_2013_1.pdf (accessed May 25, 2014); Amnesty International, “Squeezing the Life out of Yarmouk: War Crimes Against Besieged Civilians,” AI Index MDE 24/008/2014, March 2014, http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/asset/MDE24/008/2014/en/c18cfe4d-1254-42f2-90df-e0fce7c762fc/mde240082014en.pdf (accessed May 5, 2014); Nidal Bitari, Yarmouk Refugee Camp and the Syrian Uprising: A View from Within, Journal of Palestine Studies, Autumn 2013, http://www.palestine-studies.org/files/Yarmouk%20Refugee%20Camp/BitariFinal.pdf (accessed May 28, 2014).

[5] “2014 Syrian Arab Republic Humanitarian Assistance Response Plan (SHARP),” December 15, 2013, http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/2014_Syria_SHARP.pdf (accessed May 1, 2014); Syria Needs Analysis Project, “Palestinians from Syria,” March 2014, March 2014, http://www.acaps.org/reports/downloader/palestinians_from_syria_march_2014/77/syria (accessed May 17, 2014)