Torture Camps in Yemen

Abuse of Migrants by Human Traffickers in a Climate of Impunity

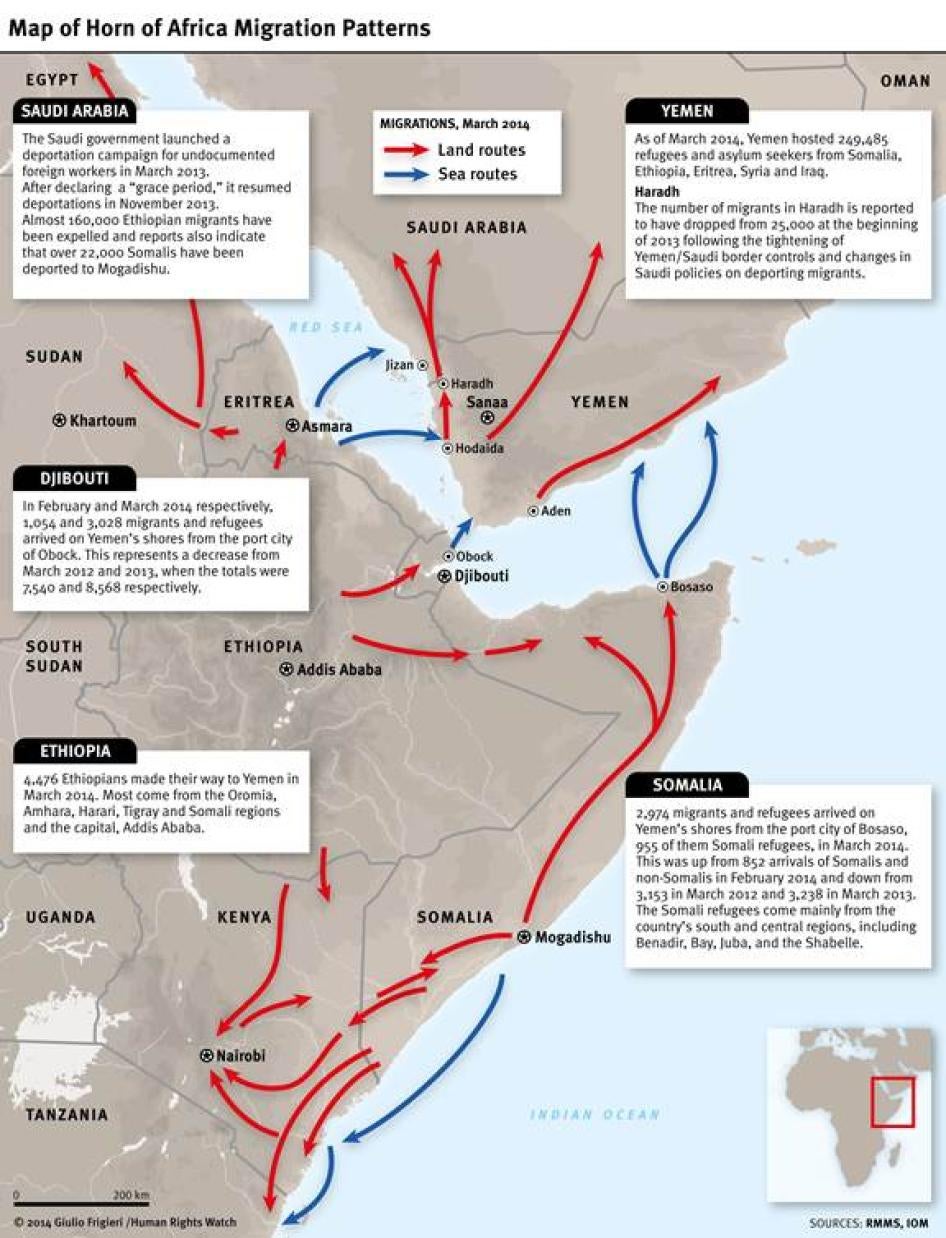

Map of the Horn of Africa Migration Patterns

Summary

For decades, migrants from Africa have passed through Yemen to seek work in Saudi Arabia. Since 2010, more than 337,000 migrants and refugees have landed on Yemen’s coastline from the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden. Their numbers rose significantly, and then dipped in July 2013, most likely due to a Saudi crackdown on undocumented migrant workers, only to rise again in March 2014. A multi-million-dollar trafficking and extortion racket has developed in Yemen based on the migrants’ passage. Its locus is the hot and dry northern Yemeni border town of Haradh, where one government official estimated that trafficking and smuggling make up about 80 percent of the economy.

Since 2006, Yemeni traffickers in and around Haradh have found a particularly horrific way to make money: by taking migrants captive and transporting them to isolated camps, where they inflict severe pain and suffering to extort money from the migrants’ relatives and friends in Ethiopia and Saudi Arabia.

In interviews with Human Rights Watch, migrants who survived or escaped these places referred to them as “torture camps.” Their accounts, along with those of traffickers, smugglers, government officials, and health and aid workers, paint a picture of an enduring network of illegal operations that, according to them, is bound together by Yemeni officials of various ranks and positions who at a minimum take bribes to turn a blind eye, or may play a more active and insidious role in the operations.

Except for a spate of Yemeni government raids that ended in 2013, the authorities have done little to stop the trafficking. Officials have more frequently warned traffickers of raids, freed them from jail when they are arrested, and in some cases, have actively helped the traffickers capture and detain migrants.

Between June 2012 and March 2014, Human Rights Watch interviewed 67 people for this report, including 18 male migrants from Ethiopia, of whom 4 migrated when boys, 10 traffickers and smugglers, as well as health professionals, government officials, activists, diplomats, and journalists.

Migrants told Human Rights Watch that armed men greeted them as they waded onto shore from rickety boats on the Yemeni coast. “They kept pointing their guns at us and yelling to get onto the backs of the trucks,” said Ali Kebede, a 21-year-old farmer from Ethiopia who landed on the Yemen coast in August 2013.

These armed men are from gangs of smugglers and traffickers whose networks extend to Djibouti, Somalia, Ethiopia, and Saudi Arabia. They sell African migrants from one gang to the next, through a syndicate, as the migrants pass from country to country. But in Yemen, the migrants cease to have any choice in the matter. The smugglers and traffickers on the Yemeni shore pay the boat crews for each migrant and then demand money from the Africans. They forcibly take those who cannot pay or who refuse to pay to their isolated camps to be tortured.

“Welcome to hell,” one trafficker told a migrant upon his arrival at a camp. An official shared with Human Rights Watch information on 12 such camps, and thought the total number in the area was 30; a long-time aid worker put the number of camps in and around Haradh at 200. Some camps consist simply of a walled yard where traffickers hold dozens or even hundreds of migrants, sometimes with only a tarp hanging over posts to shelter them from the blazing sun. Sometimes there is no shelter at all. The more elaborate camps have guard towers and concrete buildings.

Brutality is the trafficker’s tool. The migrants who Human Rights Watch interviewed described how their captors had tortured them to force them to phone relatives to ask for money. Beatings were commonplace. One man described watching another man’s eyes being gouged out with a water bottle. Another said that traffickers looped metal wires around his thumbs and hung him for up to 15 minutes, and tied a string around his penis from which they suspended a full water bottle. Others described watching or hearing traffickers rape women from their group.

Aid workers told Human Rights Watch they observed signs of abuse in migrants consistent with their accounts of traffickers ripping off their fingernails, burning the cartilage of their ears, branding their skin with irons, gouging out their eyes, and breaking their bones. Health professionals at a Haradh medical facility said they commonly saw migrants with injuries including lacerations from rape, damage from being hung by their thumbs, and burns from cigarettes, and hot, melted plastic. One medical worker told Human Rights Watch about treating more than 1,100 migrants in Haradh over the last four years and said that well over half of them reported torture.

The torture sometimes ends in death. An Ethiopian man told Human Rights Watch that he saw traffickers tie a man’s penis with a string and beat him with wooden sticks until the man died before his eyes. Another said that traffickers killed two men in his group by hacking at them with the blade of an axe. The chief doctor at the Haradh hospital said that the hospital receives the bodies of at least two migrants per week. Traffickers occasionally torture an African to near death and then drive to the wall of the Migrant Response Centre in Haradh, which is run by the International Organization for Migration, and dump the person there.

The use of torture against migrants is highly profitable. Migrants who spoke to Human Rights Watch said their family members and friends paid ransoms for their freedom ranging from US$200 to over US$1,000. A trafficker who negotiates ransoms said that he is often able to extract US$1,300 per migrant from their families.

Many of the migrants trapped in the camps come from poor families who lose their property or go deeply into debt to pay a ransom. Eighteen-year-old Sisay Mengesha, who had sold his ox to pay smugglers for his passage to Saudi Arabia, was held as a hostage in a camp until his mother sold the family’s small farm to secure his release. Others simply have no resources to pay off the traffickers. Araya Gebremedihin, 16, said that when he phoned his mother from the camp, she said, “I have only one cow and nobody will buy it. If they hurt you, they hurt you. I can’t do anything for you.” He was particularly fortunate to escape and survive.

When migrants go free, they face new perils, including navigating the extreme heat of northern Yemen on foot with insufficient water and food, and inadequate clothing and shoes. Hagos Gebremedihin, 28, from the Ethiopian village of Qoro in West Tigray, told Human Rights Watch that his captors realized that they would not get money for him and simply released him one night around 2:30 a.m. He ran all night, he said. “It was sandy and extremely hot,” he said. “My leg was wounded and my knees were shaking; my body was very tired. I felt like I was unconscious, like an animal moving by instinct.” He and other migrants are also often aware of the danger that another group of traffickers may pick them up and force them to another torture camp to repeat the ordeal.

The abuses associated with the camps are well-known to the Yemeni government. A government official in Haradh provided Human Rights Watch with a list of 14 individuals who run 12 torture camps in the vicinity. Some have been arrested, but only one was in custody at this writing. The camps are usually run by the Yemeni owners of the land, who typically come from local families known to officials.

Traffickers pay checkpoint officials similar rates for permission to drive through carrying Yemeni and African migrants to the Saudi border. But the level of government complicity in the trafficking operations goes beyond petty bribery: smugglers and migrants alike described some government officials themselves holding migrants in custody before turning them over to traffickers for money.

One migrant, Ali Kebede, told Human Rights Watch that he had escaped a torture camp with a friend in August 2013 and they walked for 10 days before Yemeni soldiers at a checkpoint near Haradh apprehended them. While the two were fed bread and tea, the soldiers made some calls and a car appeared with two men. The men discussed the hawala money transfer system with the soldiers, then handed the soldiers Saudi cash. The soldiers forced Kebede and his friend into the car, and the men drove them to their torture camp.

Involvement in trafficking appears to extend to elements within all the state security forces in Haradh: police, military and the intelligence services. Traffickers, smugglers, and Yemeni government officials named senior officials as being complicit and two officials admitted to Human Rights Watch that traffickers had bribed them in order to ensure they were not raided or arrested.

There appears to be total impunity for security forces involved in trafficking. Interior Ministry and other officials could not point to a single case of disciplinary or legal action against officials for collaborating with traffickers.

From March to May 2013, Yemeni security forces engaged in a series of raids of traffickers’ camps, but little information has been provided about the outcomes. The security forces discontinued the raids, according to the Defense Ministry, because they were unable to provide the migrants with food or shelter upon their release. Officials acknowledged that the camps that security forces had raided were now functioning again.

Border Guard commander Ali Yaslam, who coordinated the 2013 raids, said about 50 to 55 camps were raided and 7,000 migrants released, figures other officials consider inflated. While Yaslam said that all property owners and some of the traffickers present at the raided camps were sent to the Criminal Investigation Department, a local Haradh official said only 14 to 20 traffickers were charged. Human Rights Watch has yet to verify a single successful prosecution of a trafficker.

In 2013, a Border Guard commander in Haradh sent information to the local prosecutor on 36 traffickers and landowners arrested in torture camp raids. This information was shared confidentially with Human Rights Watch. “The prosecution did not do its job in holding the criminals accountable and they did not cooperate with the security and military bodies even though they knew of serious crimes committed against migrants by traffickers and camp-owners,” the frustrated commander said in a letter to his superiors. Even though traffickers killed a number of soldiers during the raids, he said, “all of that was ignored by the prosecution and instead they acquitted the criminals and became de facto protectors of the smuggling gangs.”

A judge at the trial court in Haradh, which handles minor felonies, said that he has seen only a single case related to abuse against migrants, and that the prosecutor in that one case botched the prosecution. Human Rights Watch found no indication that more serious charges have been brought in the nearby higher criminal court.

The Yemeni government’s failure to investigate and prosecute serious abuses committed against migrants by private individuals and entities or to investigate and prosecute involvement of government officials in this abuse violates Yemen’s obligations under international human rights law. International rights bodies have made clear that governments have positive obligations to protect individuals from acts, such as infringements on the rights to life and to bodily integrity, committed by private persons. A government’s failure to prevent, investigate, or punish such abuses may itself give rise to a violation of those rights.

Although Yemen is not a party to the United Nations Trafficking Protocol, the crimes described in this report nonetheless constitute trafficking. They include the transport, transfer, and harboring of migrants by using force or the threat of force for the purpose of slavery. The practice by traffickers in Yemen of effectively “selling” migrants to each other amounts to slavery under international law.

The Yemeni Constitution and international law prohibit torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment. While the intentional infliction of severe pain or suffering by someone not a public official is not technically “torture” under the Convention against Torture, the convention nonetheless places obligations on governments to adopt measures against such acts by non-state actors. The Committee against Torture has been clear that government officials can be complicit in torture and other ill-treatment carried out by non-state actors.

Saudi border officials have also been complicit in the abuse of migrants, by apprehending border crossers and turning them over to Haradh-based traffickers. They also frequently shoot at migrants. Migrants described seeing dead bodies strewn across the desert border region, and aid workers and officials said the local morgue housed dozens of bodies of migrants shot on the border.

To end the horrific abuses committed against migrants in Yemen, the Yemeni government should develop a comprehensive strategy, including raids, to stop the functioning of torture camps. Officials should work with humanitarian organizations to provide all migrants freed from captivity with adequate food, shelter, and health care.

The government should launch a concerted law enforcement effort to investigate and prosecute traffickers, as well as members of the security forces, regardless of rank, suspected of collusion with traffickers. Yemen’s attorney general should initially focus on trafficking in and around the town of Haradh. The police, military, and intelligence agencies should take appropriate disciplinary action against personnel implicated in trafficking and assist in the investigations.

Parliament should pass the draft anti-trafficking law, pending before parliament, and finalize a draft law on refugees and asylum seekers. Yemen should ratify the UN Trafficking Protocol.

International donors to Yemen, including the United States, the European Union and its

member states, and the Gulf Cooperation Council states, including Saudi Arabia, should call on the Yemeni government to take steps to end the collusion of security forces with traffickers, and ensure that the military and police shut down the torture camps once and for all.

Recommendations

To the Ministry of Interior

- Ensure that law enforcement agencies actively investigate and prosecute perpetrators of crimes against migrants and refugees. Discipline or prosecute as appropriate officials who fail to investigate such crimes or are themselves implicated in such abuses.

- Ensure the protection of survivors of sexual violence and provide them with medical and psychological support.

- Strengthen the search-and-rescue capacity of the Coast Guard, as well as awareness of migrants’ human rights.

- Uphold the rights of all migrants, particularly those held in Yemeni detention facilities.

- During the release or return of migrants to their home countries, set up functional mechanisms to identify asylum seekers and refugees and grant all individuals claiming asylum access to fair and efficient asylum procedures.

To the Ministry of Defense and Office of the Attorney General

- Investigate military and police collusion with traffickers and discipline or prosecute as appropriate those responsible, regardless of rank.

- Create safe and secure mechanisms, such as telephone and Internet hotlines, for the general public and government officials to report corruption and other illegal practices.

To the Ministries of Justice, Defense and Human Rights

- Coordinate to develop a comprehensive strategy, including raids, to stop the functioning of torture camps. Allot enough resources to provide migrants freed from captivity with adequate food, shelter, and health care access until they can be repatriated.

To the Criminal Investigation Department

- Monitor with judicial warrant, cash transfers from African countries to the town of Haradh through cash transfer companies with offices in Haradh in order to locate and identify traffickers extorting money from migrants.

To the Parliament

- Ratify the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children.

- Enact a national anti-trafficking law that is in line with international standards, including significant penalties for violators.

To the Governments of Saudi Arabia and Yemen

- Prosecute appropriately perpetrators of human trafficking, including members of the security forces complicit in abuses.

- Publicly raise awareness of the gravity of rights violations against migrants.

- Improve the capacity of the security forces and other law enforcement officials to differentiate between smuggling, which is voluntary, and trafficking, which is not, so they may better protect victims of trafficking.

To the Government of Saudi Arabia

- Order military and other law enforcement operations in border regions to rescue migrants who are the victims of trafficking when they encounter them and to arrest their captors when feasible.

- Order border guards to end any ”shoot on sight” policy against migrants at the border that may be in place; appropriately discipline or prosecute those responsible for issuing such orders.

- Stop detaining migrants in inhumane and degrading conditions in deportation centers.

- Immediately introduce procedures allowing refugees to seek asylum or other forms of protection.

To the Governments of Ethiopia and other Sending Countries to Yemen and Saudi Arabia

- Urge transit and receiving countries to enact and implement laws to protect migrants, regardless of whether their entry was legal.

- Launch targeted information campaigns, combining the efforts of governments, donor countries, intergovernmental organizations, and nongovernmental organizations to ensure that prospective migrants are informed both of the risks of migration and their rights to freedom of movement, and protection and assistance from officials in each country through which they pass.

- Closely monitor private employment agencies (PEAs) and hold them responsible for ensuring safe transit to their destination. Monitor and prosecute brokers who knowingly send migrants into the hands of traffickers.

To Donor Countries

- Support improvements in the way that nongovernmental organizations can better assist the humanitarian needs of migrants in Haradh.

- Call on Yemeni and Saudi Arabian authorities to investigate and prosecute traffickers responsible for the abuses against migrants and hold accountable members of state security forces who carry out or facilitate these abuses.

Methodology

This report is based on field research in Yemen conducted by Human Rights Watch researchers in and around the town of Haradh, between June 2012 and November 2013, and in the capital, Sanaa, between August 2013 and March 2014. We interviewed 67 people in total, including 18 male migrants, of whom 4 were children at the time of their interview or during their migration to Yemen. We also interviewed 10 smugglers and traffickers, a person working with both traffickers and state security services, 16 local officials, and 3 local doctors, as well as human rights activists, local and international journalists, and diplomats. A videographer and a film producer, whom Human Rights Watch hired to work on this project, conducted seven of the interviews with migrants and one with a trafficker, all in January 2014.

Interviews were conducted in Arabic, Afan Oromo, Amharic, French, and English, using interpreters where necessary. Human Rights Watch carried out follow-up interviews by telephone and email. Human Rights Watch informed interviewees of the purposes of our research. No payment or other inducement was offered.

Local contacts in Haradh helped identify smugglers and traffickers based in Haradh and facilitate interviews with them in secure locations in order to protect their identities. In one case, Human Rights Watch conducted a group interview with seven of them, and one-on-one interviews with three others.

Human Rights Watch interviewed the migrants at the International Organization for Migration camp in Haradh, and in a Haradh location where migrants live while awaiting an opportunity to return home or travel to Saudi Arabia. While we conducted most interviewees with migrants individually, we interviewed some in the presence of others, asking each about different incidents. On one occasion, we canvassed a group of about 75 Ethiopian migrants living in an open square in Haradh, and they responded to questions by raising their hands.

All of the migrants Human Rights Watch interviewed for this report were Ethiopians, and none had sought asylum in Yemen. All 18 of the migrants Human Rights Watch interviewed one-on-one said they had been tortured in a trafficker’s camp. The migrants interviewed had been in Yemen for different periods of time when interviewed, spanning from less than one month to 22 months.

Human Rights Watch has given pseudonyms to all smugglers, traffickers, others close to the smuggling and trafficking industry, and some workers at international nongovernmental organizations, to protect those who helped facilitate this research. All names of migrants interviewed have been replaced by pseudonyms to protect their identity.

In October 2013, Human Rights Watch met with representatives of the Yemeni Ministry of Interior to inform officials of our initial findings and request responses to specific questions. This report reflects comments they made during the meeting. Human Rights Watch sought but was unable to obtain meetings with officials from the Office of the Attorney General, including the Haradh prosecutor, and the Ministry of Defense.

In April 2014, Human Rights Watch wrote to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and provided a list of questions for the Ministries of Defense, Interior, and Justice. Despite several follow-up requests, however, Human Rights Watch had not received a reply from the Yemeni government by the time this report went to print. Any future responses to this report from the Yemeni government may be posted on the Yemen page of the Human Rights Watch website: www.hrw.org.

Human Rights Watch also reviewed a range of public materials, including reports from nongovernmental organizations and the United Nations, media reports, official statements, private ministerial correspondence shared by government sources, and court documents provided to Human Rights Watch by a judge. The annex, which lists 37 people alleged to have committed crimes related to trafficking, is derived from seven letters sent by a police official in Haradh to the local prosecution team, as well as an internal Ministry of Defense letter, all of which were unofficially provided to Human Rights Watch.

This report uses the term “torture” in its everyday sense of the infliction of severe physical or mental pain as a means of punishment or coercion, not as it is defined in international human rights law, except in chapter VI on Yemen’s legal obligations. Torture as defined in the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment refers to:

“…any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity.”[1]

In this report, those allegedly committing “torture” are private individuals, not public officials or those acting on behalf of public officials and the aim is typically for coercion or to obtain information, but not confessions.

This report frequently refers to the “trafficking,” as opposed to the “smuggling” of migrants. When smugglers in Yemen abuse, capture, and extort money from migrants, even those who have paid them to transport them to Saudi Arabia, the smugglers are considered traffickers as defined under international law.

I. Background

Migration to Yemen

In recent years, hundreds of thousands of migrants from the Horn of Africa have flooded into Yemen, some searching for local jobs as domestic servants or in construction or agriculture, but most hoping to travel on to neighboring Saudi Arabia for employment.[2] Yemen itself is the poorest country in the Middle East. In 2011, the United Nations reported that 55 percent of Yemen’s population of 24 million was living in poverty.[3] The country’s water supplies are rapidly diminishing and some 13 million people live without access to safe water or sanitation.[4] Almost 43 percent of children in Yemen are malnourished, and more than 6 million people have no access to health care. Conflict has displaced more than 300,000 people.[5]

Officials said they first saw waves of migrants from the Horn of Africa passing through to Saudi Arabia in the 1970s, as they fled war and insecurity at home.[6] New waves of migrants began passing through in the 1990s, after Ethiopia's present government came to power in 1991 and removed restrictions on emigration.[7] Armed conflict in Somalia has pushed over 966,000 refugees into nearby countries over several decades, including 244,000 who reside in Yemen and who are automatically granted refugee status, based simply on their nationality.[8] Africans from as far away as Nigeria and Niger also pass through Yemen via the Horn en route to the wealthier countries of the Arabian peninsula.

Especially since the 2011 uprising in Yemen, the government has had difficulty asserting control over much of the country, including land and sea borders, which may have encouraged traffickers and spurred migration.

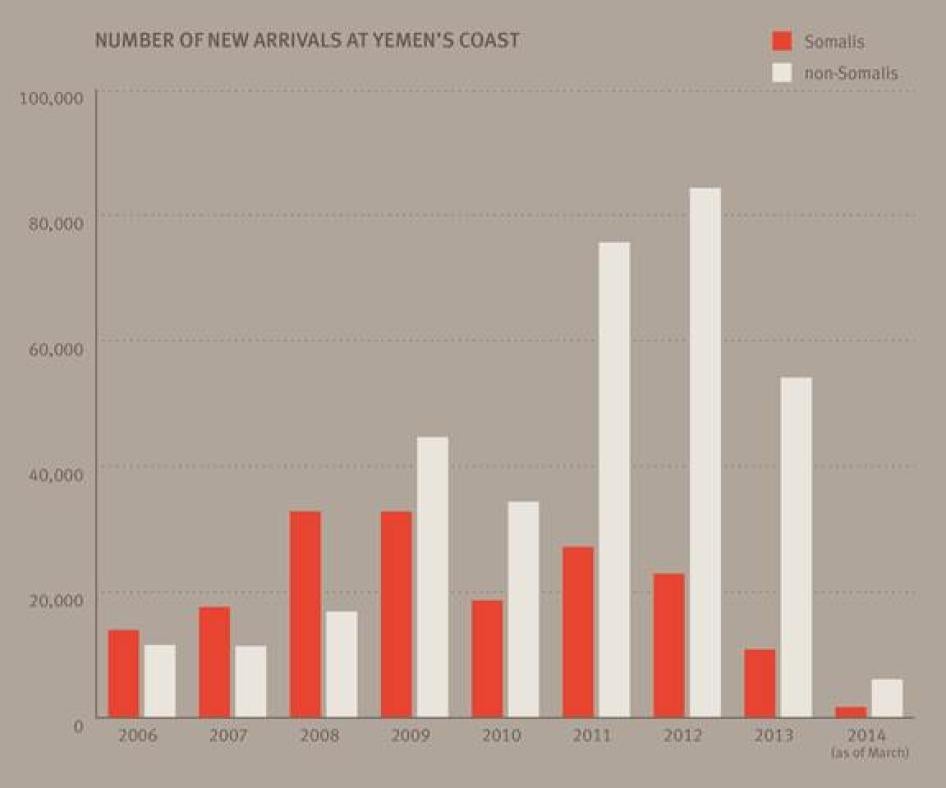

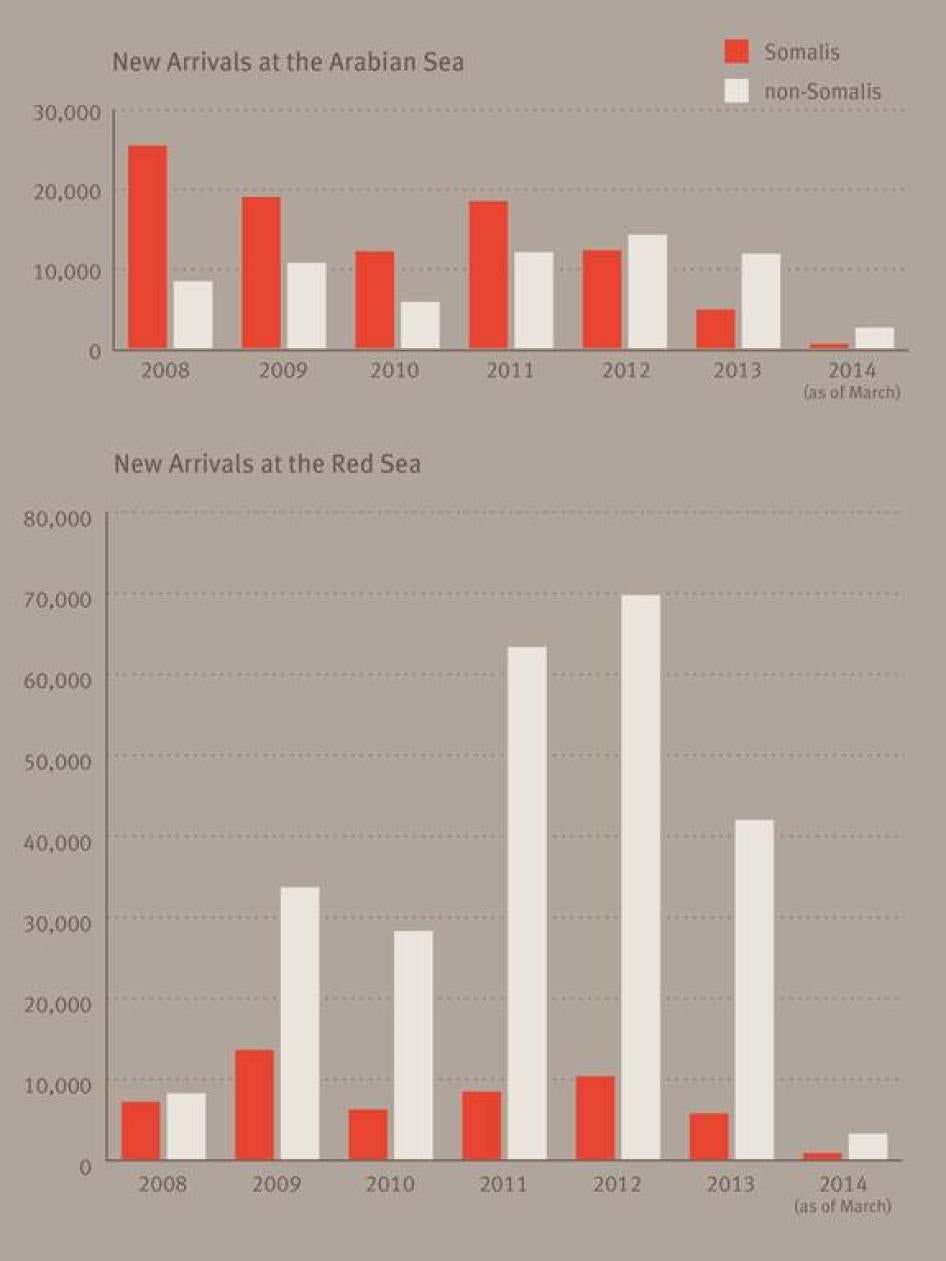

In 2010, 53,000 migrants and refugees arrived on Yemen's shores; this number doubled to 104,000 in 2011, and rose again to 108,000 in 2012, only to drop to 65,000 in 2013, according to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).[9]

Though organizations tracking the numbers cannot definitively explain the 2013 drop, which started in July, many aid workers said that the likely reason was Saudi Arabia’s 2013 campaign to deport undocumented migrants and tighten border security.[10] In 2014, numbers rose again, according to UNHCR. Between January and March 2014 8,148, migrants arrived on Yemen’s shores.[11]

During the first half of 2013, a full 83 percent of the 65,319 migrants and refugees UNHCR tallied in Yemen were Ethiopian; 17 percent were Somali, and there were small numbers of Eritreans, Djiboutians, and Sudanese—whereas only three years prior, the majority of new arrivals were Somali.[12] The routes into the country have changed too. Until 2009, most migrants were coming to Yemen from northeastern Somalia across the Gulf of Aden. Since 2009, the majority have been crossing from Djibouti across the Red Sea. [13]

An entire underground economy has grown up around trafficking Africans through the country and over borders and extorting money from them. Yemeni smugglers and traffickers make large amounts of money moving migrants through their country. One 2013 study which tracked the cost of the industry in each of the countries involved estimated that the migrant trafficking industry across the Red Sea from Djibouti to Yemen alone is worth between US$11 and $12.5 million.[14]

There are major gaps in knowledge about the migrants. For example there are no estimates of the number of migrants currently living in Yemen who are not refugees—a category that includes the people Human Rights Watch interviewed for this report.[15]

The UNHCR numbers are generated from the numbers of people the organization serves in its programs for refugees and asylum seekers, and on figures from its partners, the Danish Refugee Council and the Society for Humanitarian Solidarity, which conduct daily patrols of the Yemeni coastline.[16]

Humanitarian organizations reported registering and assisting 11,308 migrants during 2012 in Haradh, of whom around 9 percent, or 1,000, were children.[17] The Regional Mixed Migration Secretariat (RMMS), an independent agency that supports other agencies, institutions and forums in the Horn of Africa and Yemen to improve the management of protection and assistance response to people in mixed migration flows in the region, has documented the presence in Yemen of unaccompanied Somali and Ethiopian children as young as 9, primarily boys, who say that they traveled to Yemen because their parents or guardians at home relied on them to find work and send money back for the family to survive.[18] African children in Yemen are subjected to similar abuses as adults.

Little is also known about the small numbers of women from the Horn of Africa who attempt the journey to Saudi Arabia. Of 271 migrants the Danish Refugee Council interviewed before they were repatriated, only five, or 1.8 percent, were female. Yet many of the migrants told the researchers that when they crossed the Red Sea to Yemen they remembered traveling with girls—and no one could say what happened to them.[19] The Danish Refugee Council reported that accounts by some Yemeni and Ethiopian migrants suggested that the girls may have been trafficked as virtual domestic slaves to households in Saudi Arabia while others were trafficked for sexual exploitation.[20] Ethiopian women interviewed for the same report said that during their journey through Djibouti, Somalia, and Yemen, they had been raped.[21] Some Ethiopian women told an international aid worker who assists migrants on the Yemeni coast that they took contraceptive pills before boarding boats to Yemen, because they were aware of the likelihood of rape on the journey.[22]

Emigration from Ethiopia

A combination of poverty, repression, and proximity to relatively prosperous labor markets in Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states has fueled, and continues to fuel, migration from Ethiopia to Yemen.

Ethiopia is one of the poorest nations in sub-Saharan Africa. Average GDP is just US$470 annually, the sixth-lowest globally.[23] Despite recent macroeconomic gains, extreme poverty pervades the countryside. Jobs are hard to find and pay is low.[24]

Jemal Muhammad, 17, who is from the Amhara region of Ethiopia, told Human Rights Watch he came to Yemen alone “because I'm poor.” His father died and his mother is too old to work, he said. “I don’t have income, so that’s why I left.”[25]

Ethiopia is also one of Africa’s most repressive nations. The ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front came to power in 1991 and severely curtailed access to information and freedoms of expression and association. Officials have shut down most legitimate political avenues for peaceful protest and imprisoned opposition leaders, civil society activists, and independent journalists. Those who fail to support the government do not receive state benefits, including access to agricultural inputs, food aid, employment, and education opportunities.[26]The government particularly targets those with suspected connections to the outlawed Oromo Liberation Front and Ogaden National Liberation Front, which the government considers terrorist organizations.[27] This repressive environment has resulted in the emigration of thousands, and most of Ethiopia’s neighbors host significant numbers of Ethiopian refugees.

Most Ethiopians in Yemen do not register with their embassy. Even those who cite economic rather than political reasons for migrating tell aid organizations that they suspect the Ethiopian authorities are trying to monitor them. Ethiopia demands the forcible return of Ethiopians who claim refugee status from some, particularly neighboring, countries. In 2012, Djibouti, Somalia, and Sudan are all known to have returned Ethiopian citizens at the request of the Ethiopian government, but not Yemen.[28]

Recognizing the importance of remittances, Ethiopia has in the past facilitated and encouraged labor migration even as it regulates the industry to combat abuse and human trafficking.[29] The government invokes anti-trafficking legislation to prosecute recruitment agencies that work without official approval.[30] Officials at the Ethiopian Embassy in Sanaa estimated that in 2013, the Ethiopian government arrested 180 Ethiopian labor recruiters based in Ethiopia.[31]

On October 25, 2013, Ethiopia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs announced a temporary government ban on citizens traveling abroad for employment, “in an effort to curb the rising tide of abuse and exploitation.” The ministry, which also indefinitely suspended the licenses of foreign employment agencies, said it issued the ban because it had failed in other efforts “to prevent abuse and even killings of many Ethiopians” traveling abroad for work.[32]

The Smugglers’ Town of Haradh

According to organizations tracking the movements of migrants, the majority of Africans passing through Yemen to Saudi Arabia travel through Haradh, a town of 94,000 in Hajja governate, 7 kilometers (4 miles) south of the border with Saudi Arabia and 30 kilometers (19 miles) inland from the Red Sea coast. In Haradh, a place prone to extreme heat and flash flooding, a government official estimated that at least 80 percent of the local economy is based on smuggling.[33] Humanitarian organizations have estimated that at its peak in late 2012 early 2013. Haradh hosted an average of 25,000 migrants hoping to travel to Saudi Arabia or return home. The International Organization for Migration (IOM), an intergovernmental organization that works closely with governmental, intergovernmental and nongovernmental partners to manage migration and aid migrants, in 2012 registered 11,298 vulnerable Ethiopian migrants for repatriation at its camp in Haradh, and from January to September 2013, the organization registered 6,228 Ethiopian migrants for repatriation.[34]

In mid-2013, the number of migrants in Haradh dropped precipitously for the first time in five years, possibly because of Saudi mass deportations of undocumented migrants and tightened border security. An official from the Yemeni Human Rights Ministry in Haradh estimated that as of mid-2013, about 25,000 migrants were present.[35] Local officials described throngs of migrants at the doors of restaurants during mealtimes in June, waiting for restaurant staff to give them leftovers.[36] By September 2013, only about 500 to 600 migrants remained in town.[37]

During January and February 2014, with reduced numbers of migrants in Haradh, the IOM had closed its Migrant Response Centre (MRC) to new arrivals except for medical emergencies and vulnerable cases. Though it had considered closing down its provision assistance structures for third country nationals and shifting all resources to Yemeni returnees, the numbers of stranded African migrants in Haradh increased tenfold, from 800 in January 2014 to a total of 8,000 by March 2014.[38]

Regional Context

In February 2014, Human Rights Watch documented serious allegations of torture and abuse of Eritreans in eastern Sudan and Egypt’s Sinai peninsula between mid-2010 and early 2014. [39] Initially Eritreans travelled voluntarily, with smugglers, from eastern Sudan through Egypt towards Israel, Human Rights Watch found. But as of 2011 the smugglers increasingly turned on their clients and abused them to extort tens of thousands of dollars in exchange for the onward journey, thereby becoming traffickers. By 2012 large numbers of Eritreans were being kidnapped in eastern Sudan and taken against their will to Egypt, where they were tortured. In 2013 and early 2014 media and other sources reported that , smugglers transporting Eritrean, Somali and Sudanese nationals to and through Libya had abused their clients to extort additional money from them. [40]

Migrants en route to Saudi Arabia along Yemen’s Hodaida-Haradh road, May 2013. (C) 2013 Michael Kirby Smith

Ethiopian migrants piling into a pickup truck to work in qat fields near Rada`a, Yemen, June 2013. (C) 2013 Michael Kirby Smith

II. The Journey

Most of the migrants interviewed by Human Rights Watch were men in their early 20s, though we also interviewed boys as young as 12 and men as old as 43. All of them came from impoverished rural Ethiopia, the majority from Wollo, an agrarian northeastern province with a sizable population of the ethnic Oromo group. Four of those interviewed had been farmers, six were high school students from farming families, and one was a shepherd.

All those interviewed told Human Rights Watch that friends from their villages connected them with brokers who promised, for a fee, to arrange their passage to Saudi Arabia, either by procuring a visa or arranging a smuggling route, usually through a network of smugglers in each country along the way.[41] In some cases the fee paid was supposed to include all costs to get to Saudi Arabia, and in others just one leg of the trip. Muhammad Awol, 20, a student from Wollo, said a friend introduced him to a local broker whom he paid 1,700 Ethiopian Birr ($89) to take him to the town of Gore, in southwest Ethiopia, where he paid another broker 2,100 Birr ($111) to take him to Yemen.[42] The migrants told Human Rights Watch that different smugglers escorted them for successive stretches of the trip. Some paid brokers the exact same amount for the same leg of the journey, suggesting coordination between traffickers charging similar rates. Among those who provided Human Rights Watch a figure, the prices paid for the journey ranged from $315 to $433. Some said they exhausted family savings or sold their families’ work animals or farms to pay for the passage.

Traffickers and smugglers told Human Rights Watch that smuggling networks extend through Djibouti, Somalia, Ethiopia, and Saudi Arabia. They said that members of their smuggling and trafficking gangs maintain phone and text message contact throughout the migrants’ journey. Smugglers and traffickers sell people from one gang to the next, through a syndicate, as the migrants pass from country to country.

Journey over Land

Migrants described setting out for their journey in a group with a guide from landlocked Ethiopia to the port city of Obock, Djibouti. Some made the entire journey on foot, while others hid in container trucks.

Regardless of how they travel, migrants risk death. The terrain is arid and hot, and many traveling by foot have insufficient food and water, flimsy shoes, and little protection from the sun. People suffer severe dehydration, leading to kidney failure, said Ibrahim Zaidan, a representative of the Human Rights Ministry in Haradh, who regularly interviews migrants in the hospital soon after they arrive in Yemen.[43]. Traveling by vehicle from their homes to the border with Djibouti is also perilous. In February 2012 Ethiopian authorities seized a container truck filled with 75 Ethiopians near the Djiboutian border; 11 had suffocated to death.[44]

The migrants Human Rights Watch interviewed entered Djibouti openly, at border crossings and over open land, without interference from officials.[45] “At the border we passed lots of guards, but no one stopped us,” said Akmel Ibrahim, 30, a farmer from Silte, Ethiopia, who said a smuggler led him and a large group of others across the border on foot in September 2012.[46]

Voyage over Sea

Migrants said that upon reaching Obock, they had to wait until night to board a boat to ferry them to the Yemeni coast. Those who could identify the nationality of the boat crew said they were Yemeni. They reported as many as seven crewmembers on one boat. The boats each transported from 27 to 151 migrants, sometimes including as many as 10 children. One migrant described the vessel that in August 2013 took him as a small wooden fishing boat with a motor, crowded with 63 passengers.[47] Some boats transported only men, but on others more than half the passengers were women. One said he traveled in a convoy of three boats. After a six or seven-hour journey, the boats reached the Yemeni coastline at dawn.

The dangers of the sea crossing to Yemen have decreased since Human Rights Watch published its 2009 report on refoulement and abuse of refugees in Yemen.[48]

The Yemeni coast guard has pledged not to intercept boats as they land, and most boats now approach the shore so that passengers can disembark in shallow water, decreasing the likelihood of drowning.[49] Conditions on the boats themselves seem also to have improved dramatically in recent years, perhaps because the migrants’ lives now have monetary value to smugglers who buy and sell them along the route and traffickers who extort ransom from them in Yemen. According to Christopher Horwood, coordinator of the RMMS, “There is a direct correlation in the rise of kidnapping and torture camps and the murder of migrants at sea (and disembarking them in the water). This is what we emphatically call ‘commoditization of migrants’.”[50]

From January to October 2013, UNHCHR documented the deaths or disappearances of only five migrants attempting to cross either the Gulf of Aden or the Red Sea, a drop from 2012, when 43 migrants were reported dead or missing, and 2011, when 131 migrants were reported dead or missing.[51]

Only one migrant told Human Rights Watch that he witnessed abuse on the boat to Yemen. In May 2013, Sindew Yimam Idris, a 43-year-old farmer from Wollo, said he boarded a boat to cross the Red Sea with 130 migrants, including 10 unaccompanied children under age 14.[52] The children were traveling without their families to seek work in Saudi Arabia, and for no apparent reason the boat crew beat them with wires. “I cried on the boat,” Idris said. “I was crying because I watched.”

The boats’ crews illegally transport migrants without fear of arrest. One Haradh-based trafficker told Human Rights Watch that as far as he and his colleagues are concerned, there is no functioning coast guard. He said that he currently works with Yemeni boat crews that ferry hundreds of people over the Red Sea every 10 to 15 days. He said he has never seen a Yemeni coast guard ship.[53] The Djiboutian ambassador to Yemen told Human Rights Watch that his country’s coast guard agents usually just report unlicensed boats to their Yemeni counterparts, and that recently, in June 2013, when the Djiboutian coast guard tried to intercept a Yemeni ship, the crew opened fire.[54]

Only one migrant interviewed by Human Rights Watch encountered the coast guard of any country. Hagos Gebremedihin, 28, from West Tigray, Ethiopia, said that the Djibouti navy stopped his boat full of migrants in the Red Sea:

They took the captain off the boat, leaving us for approximately an hour and a half alone in rough seas. During that time we were very stressed. When the navy brought back the captain after an hour and a half, they beat him and demanded hawala [money transferred through an informal system]. The captain started calling everywhere [to get money]. The navy eventually took a large container from the boat…. [and] the boat started moving again.[55]

III. Torture Camps

By 2006, migrants were reporting to humanitarian workers that traffickers had detained, beaten, and robbed them.[56] Local gangs set up camps in the desert around Haradh as traffickers started holding migrants and demanding that their victims phone their families back home or friends already employed in Saudi Arabia to get additional funds to cover the rest of their trip to Saudi Arabia. Effectively, the traffickers were holding them hostage and demanding ransom. When migrants refused to comply, or failed to come up with the money, the traffickers tortured them.

In recent years, the scope and violence of the trafficking abuses against migrants have increased, along with traffickers’ revenue. The traffickers have evolved from local thugs to organizers of international networks, employing Ethiopian interpreters and intermediaries to phone migrants’ relatives to extract ransom while they torture migrants. Some international and local observers say that during the instability following the 2011 Yemeni uprising, traffickers were able to ratchet up their operations, their networks, and their violence. [57]

A June 2013 report by the Regional Mixed Migration Secretariat (RMMS) based on interviews conducted by the Danish Refugee Council found that “the majority” of around 130 respondents from the Horn of Africa who had arrived in Yemen between June 2011 and January 2013 reported being taken hostage. [58] In September 2013, the RMMS recorded 2,529 abductions, 30 incidents of sexual and gender-based violence, 198 shootings, and 273 other physical assaults (including 30 involving women) among migrants upon their arrival on Yemen’s shores. [59] Among 271 migrant African children the RMMS interviewed at the Sanaa deportation center for a 2013 report, 234 said armed men met them when they landed in Yemen, and traffickers took 222 of them to isolated camps in northern Yemen. [60]

One middle-aged Yemeni who acts as a paid informant both for local traffickers in Haradh and for the Political Security Organization, the Yemeni intelligence agency that reports directly to the president, sought to explain the use of torture as economically necessary to cover the costs of taking someone north to Haradh. Yemeni traffickers pick up the migrants from the shore and pay the boat crews about 500 SAR (US$133) per migrant, he said.[61] Including transportation costs, he estimated it costs about 700 SAR ($187) to get each migrant to his camp in Haradh.[62] He said that once there, “sometimes the trafficker finds out that the migrant has no money…. So there is no solution other than to torture the Ethiopian until he gets money.”

All the migrants Human Rights Watch interviewed for this report believed that by the time they boarded the boat to Yemen, they had already paid the full cost of their journey to Saudi Arabia.

The existence of the traffickers’ camps is common knowledge among aid and medical workers and government officials in Haradh, the nucleus of the trafficking industry in Yemen. Smugglers and traffickers spoke openly with Human Rights Watch about the camps and their locations.

Journey in Yemen to the Camps

As the boats full of migrants approach the Yemeni shore from the Red Sea in the pre-dawn hours, crew members hold migrants on board and only allow them to disembark when armed men drive up on trucks, migrants told Human Rights Watch. Sometimes they wait for several hours.[63] All of the migrants who spoke to Human Rights Watch said that they were met by traffickers – from four to a dozen armed men – as they waded ashore.

Two Haradh-based traffickers who make regular once-a-week cash payments to boat crews, and the government informant, said that traffickers paid amounts ranging from $133 and $533 per person.[64] Factors such as gender, nationality, and age did not affect the price, though they did not charge for children under five years old.[65]

Land-based traffickers, who sometimes wear police uniforms to help force compliance, tell the migrants that they will have to pay another fee if they want to get to Saudi Arabia. The traffickers put those who hand over the additional money onto trucks that go straight to the border, and those who do not onto different trucks. All those interviewed by Human Rights Watch had refused to pay the money, and believed that is why they ended up in the traffickers’ camps.

Ali Kebede, 21, the farmer from Wollo, said that he left home in September 2013 to seek work because he had to support his younger brother and sister. He told Human Rights Watch that on the open sea, he saw a Yemeni crew member making calls on his cell phone.[66] As the boat neared the shore, eight armed men stood waiting with two pickup trucks. “They kept pointing their guns at us and yelling to get onto the back of the trucks,” he said. “One man refused to get on the truck and they beat him with the butts of their guns. This made all of us afraid.”

Sindew Yimam Idris crossed the Red Sea in May 2013 on a boat with 130 other migrants, including 10 children.[67] When they waded onto shore in the middle of the night, 12 Yemeni men were waiting, Idris told Human Rights Watch. The man who appeared to be in charge was armed with a pistol, and eight others brandished rifles. The Yemenis forced the migrants to board nine open-air trucks, separating the children from the adults and forcing them onto a different truck. “I did not get to see them again,” he added, saying that he worries and wonders about them still.

The Camps

When migrants cannot pay or refuse to pay the traffickers’ price, the traffickers drive them to isolated camps, where they demand ransom and threaten and torture them until they call friends or family to procure the money. According to Haradh-based traffickers and smugglers who spoke with Human Rights Watch, the gangs that pick the migrants up at the shore sell them to other traffickers who run their own independent camps.[68] However the man Human Rights Watch interviewed who works as an informer for both the government and the traffickers said some traffickers who run camps pick up migrants directly from the shore.[69]

None of the migrants interviewed by Human Rights knew where exactly on the Yemeni shore their boats had landed, or the precise locations of the camps where traffickers had held them.

All of the migrants interviewed described having been detained in camps in deserted areas. They said that Yemenis ran the camps, sometimes with guards who were Ethiopian or Eritrean. The camps varied in structure; most of the migrants described being kept in a walled yard with a single guarded exit, under a tarp hung on posts to provide shelter from the sun. One migrant said traffickers held him in a small house, another said they detained him in a multi-story building. Kebede described conditions in the walled compound where traffickers held him in August 2013:

The camp was a square area that was totally open, with no shelter. There were concrete walls with four guard towers, one in each corner. There were no buildings in the camp. There were eight guards, who were on duty at different times, including some Ethiopians. The guards slept in the camp with over 50 of us, but they had created a small shaded area that only they were allowed to sleep under. The weather was very hot, and there were no bathrooms. We had water tanks in the camp for drinking water, but the guards only refilled the tanks every five days. The water would always be finished in a single day and we would have to go four days without water.… The seven women who arrived with us were taken to a separate area of the camp, behind a wall. I did not see them again, but I heard women screaming at night and noises that sounded like beatings. When we first arrived I saw one man lying on the ground bleeding from his back. I could not tell if he was alive or dead.[70]

Ibrahim Zaidan, the representative of the Human Rights Ministry in Haradh, who advocates on behalf of migrants, estimated that 90 percent of the camps are run by Yemeni landowners.[71]

A trafficker who frequently negotiates for ransom with migrants’ families, told Human Rights Watch that he does not know of a single camp that is not run by the person who owns the land on which the camp is situated, and all the camp owners with whom he deals come from local families.[72]

Zaidan and some smugglers and traffickers estimated that about 30 trafficking gangs operate in Haradh, with many more in surrounding areas.[73] (Other smugglers and traffickers said they were unable to estimate). Over the last two years there have also been about 30 separate functioning torture camps in and around Haradh, all well-known to the local authorities. Various officials identified Haradh as the epicenter of the migrants’ trafficking trade in Yemen, but no one could estimate the number of camps in other parts of the country.[74] A staff member from Medecins Sans Frontières estimated that there may be as many as 200 torture camps in and around Haradh.[75]

|

Al-Osaila (west of the town of Haradh) |

|

#+ |

Yahya Abdu Kudaish[76] |

|

#*+ |

Ali Saghir Abdu Kudaish |

|

#*+ |

Hadi Abdu Hassan Kudaish |

|

#+ |

Khabak (nickname) Muhammad Ibrahim |

|

* |

Ahmed Ibrahim Ali Juaidid |

|

Al-Sharifiyya (north of the town of Haradh, on the way to the border with Saudi Arabia) |

|

#+ |

Ali Haj Haradi |

|

#+ |

Ali Kuaidan |

|

#*+ |

Husain Ali Ahmed Azzam |

|

Al-Khodur (northeast of the town of Haradh, on the way to the border with Saudi Arabia) |

|

#+ |

Ali Aishan Alsunaidar[77] |

|

#*+ |

Muhammad Ibrahim Abdullah Odabi |

|

In Al-Dahel (west of the town of Haradh) |

|

#+ |

Khaled Dabos and Ali Hashim[78] |

|

In Al-Nijara (northern west of the town of Haradh) |

|

#+ |

Esam al-Jomai and Abdullah al-Jomai[79] |

Above are the names of 14 individuals who allegedly run 12 camps in and around Haradh. A Haradh-based government official provided the names to Human Rights Watch anonymously; two local traffickers and smugglers corroborated the names.

Those with an asterisk (*) next to their names were arrested and sent to the Haradh prosecutor’s office but were not subsequently prosecuted with regard to crimes committed against migrants. Only one remained in custody at the time of writing. Those with a plus sign (+) next to their names allegedly own the land on which the camps they run are located, according to the government official who provided the list, as well as a local trafficker [See Annex I for more details]. Those with a hash sign (#) next to their names were on a list identifying local smugglers sent by the Criminal Investigation Department in Sanaa to the administration of Hajja governorate, according to a government official who saw the list. The Criminal Investigation Department, within the Ministry of Interior, conducts most criminal investigations and arrests nationwide.

Torture and Abuse

All 18 of the migrants Human Rights Watch interviewed for this report said their captors tortured them to force them to make phone calls to relatives or friends to ask for money. They said that their captors beat them—using fists, feet, sticks, and cables. Four said their captors tied them up by their thumbs with rope. One said he was burned by melted plastic. Another said his captors tied his genitals with a string attached to a full water bottle.

Hagos Gebremedihin, 28, from a village in the Tigray region of Ethiopia, said that traffickers took him from the Yemeni shore to a fenced-off area next to a house:

We had no food, no water; we were still white from the salty sea water. They started beating us and demanding money and insulting us…. The women were raped, and the boys were kicked or raped by Yemenis. They demanded money. If there was someone who said he didn't have any money, they tied him up and hit him…. Sometimes they tied you up by your legs and they hit you. They make you suffer, pouring drops of melted plastic on your skin. We stayed in the smugglers’ house one-and-a-half months. It felt like five years.[80]

Araya Gebremedihin, 16, from a town in Ethiopia’s Tigray region told Human Rights Watch,

When we arrived [at the camp], the punisher said, “Welcome to hell.” We were afraid and asked, “What do you mean by that? We want to go to Saudi Arabia. What do you mean by that?” Then we went inside the house. Four Oromo [Ethiopian] people beat us and told us to line up. They started asking, “Do you have [telephone] numbers?” One guy said yes and one said no. To the one who replied no, they said, “You can't say no. If you say no, you're going to die… Then they came to me and said, “Give me a number.”

I said I don't have any friends in Saudi. He said, “Call Ethiopia.” I explained that my father and my mother, they are poor. He said, “Call!” I called to Ethiopia, to my mother, and I told her I was caught in Yemen. [I said], “If I work, I will return this money, but if I die I can't.” She answered, “I don't have money.” She said, “I have only one cow and nobody will buy it. If they hurt you, they hurt you. I can't do anything for you.” The guy asked what she said. He also spoke Tigrinya, so I told him what she said. [He got on the phone and said], “You don't need your boy, what do you mean? He's going to die.” He said like this. “Kill him,” she said. “When you kill him, inform me and I will sit and cry for him.” Then he started beating me.[81]

Bahiredin Ahmad, a 20-year-old high school student from a town in the Gurage Zone of the Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Region (SNNPR) in Ethiopia, who arrived in Yemen in February 2013 told Human Rights Watch:

They hung me up by [my] thumbs for four days, sometimes for as long as two hours, then they would give me breaks in between and let me down. ... While I was hanging, they would beat my chest and back with sticks very hard.[82]

After four days, Ahmad said, he finally agreed to call his family, and his relatives agreed to transfer the 2,500 Saudi Arabian Riyals ($667) that his captors demanded. “I just could not take the pain anymore,” he said.

Ahmad said he saw traffickers tie another man’s penis with string, and beat him with wooden sticks: “That man died before my eyes.”

Shikuri Muhammad, a 20-year-old from southern Ethiopia, said in December 2012 he spent time in a traffickers’ camp where he met another man from his home town who refused to pay ransom. Four guards started by beating the man with sticks, then one took an axe, and hacked at the man’s head with the blade. The man died. “The guards wanted to make an example out of him, and it worked,” Muhammad said. “After that, almost all of prisoners paid their ransoms.”[83]

Muhammad said that another man from the Tigray region had called his family, asking them to send the traffickers money. One day, the guards beat this man, too, with an axe, until he died in front of the other migrants. “I did not know why,” Muhammad said. Ethiopian guards later told him the traffickers had arranged for a local broker in Ethiopia to go to the man’s family home in Tigray to collect the money, Muhammad said. When the broker arrived, the police were waiting. They arrested and detained him for a few days, but he paid his way out, Muhammad said. When the broker called his colleagues in Yemen, they beat the man to death, Muhammad said.[84]

Ali Kebede told Human Rights Watch that in August 2013 traffickers tortured him about four hours a day for 13 days.[85] Guards hung him from his thumbs, beat his legs with sticks, punched him, and burned him by melting plastic on his left shin, he said. Human Rights Watch observed noticeable scars that looked like burn marks on his left shin during an interview a month later. Kebede said he saw guards use other methods on other migrants, including beating with cables and burning skin with lighters. Some migrants in the camp had lost eyes and had broken teeth. “From what I was hearing and feeling, I thought I would die in that place,” he said. Since his ordeal, he said, he has had recurring nightmares. “I happened to survive, but others didn’t,” he said. “I saw shameful things. No one deserves to see what I saw.”[86]

Jemal Said, 29, a shepherd from Wollo, left his wife and infant son in August 2013 in order to provide for them with a job in Saudi Arabia, but ended up trapped for seven days in a traffickers’ camp. “They would tie my hands behind my back and lay me down on the ground. Then they would beat me with sticks,” Said said, showing scars across his back. “I saw the guards kick the face of one man who was on the floor, breaking his teeth.” Still Said refused to call his family. “I told them I do not have a family.”[87]

Some of the men told Human Rights Watch that they had either witnessed the rape of women, or overheard it, or overheard talk of it. Akmel Ibrahim, 30, a farmer from Silte arrived in Yemen in late 2012 with about 60 others, including seven women. Traffickers transported them all to a huge open camp with high walls, already housing around 100 migrants. “I watched [the guards] punish the women,” he said, his voice cracking. “They raped the women in front of us, it was awful.”[88]

Sindew Yimam Idris, a 43-year-old farmer from Wollo, who arrived in Yemen in May 2013, said that traffickers beat him with sticks and wire cables every few days. A medical examination upon his arrival at the Migrant Response Centre (MRC) revealed three broken ribs. “I have had trouble sleeping since then,” he said, almost half a year later, showing scars on his chest and back and saying he still had severe pain. Idris said the smugglers at the camp kept the women in separate rooms in the house. “I overheard them speaking together quietly, talking about being raped,” he said.[89]

Aid workers, religious leaders, medical staff, and others in Haradh who have close contact with migrants said that they observed signs of similar abuse consistent with stories migrants told them. A humanitarian aid worker with years of experience helping migrants in Haradh told Human Rights Watch that migrants had said that traffickers had ripped off their fingernails, tied them to trees, burned the cartilage of their ears, branded their skin with hot irons, gouged their eyes, melted plastic bottles onto their skin, broken their bones, hung them by their thumbs, and tied a full, heavy water bottle to migrants’ penises. He said he interviewed a number of women who said the traffickers raped them and then burned their inner thighs with hot irons, leaving visible scars.[90]

A local Yemeni religious leader who works with migrants told Human Rights Watch he met one man who said his captors hung him suspended by his arms until his arms were virtually paralyzed, and he was unable even to lift food to his mouth.[91] An aid worker who was present during Yemeni military raids of trafficker camps in May and June 2013 said that he met a migrant who also said his captors hung him by his arms for long periods, leaving him unable to move his arms. He said that he also met between five and eight people whose captors had beaten their ears with shoes, causing them to lose their hearing.[92]

Two Yemeni doctors and a nurse at a Haradh medical facility said the most common injuries they saw among migrants were lacerations from rape, damage to the hands from hanging a person by the thumbs, and burns all over the body from cigarettes and molten plastic. They showed Human Rights Watch the medical files of a case from April 2013 that particularly horrified them. Passersby had found a 25-year-old Ethiopian man unconscious and close to death on the street next to the MRC. Staff from the IOM brought him to their medical facility, where he eventually told doctors that his captors had forced him to lie on the ground on his back with heavy weights on his chest and abdomen, for three or four days, until he lost consciousness. The skin on his back was black and rotten–the doctors said he had developed necrotizing fasciitis, a rare infection of the deeper layers of skin and subcutaneous tissues. They treated him for a month, and transferred him to Sanaa for a skin graft. “I can still smell the rotting skin on his back,” one doctor said.[93]

Aid and medical workers and migrants themselves characterized torture and other abuse as ubiquitous.

A local medical worker told Human Rights Watch about treating more than 1,100 migrants in Haradh over the last four years, including those released following the army raids. The aid worker estimated that well over half of these migrants claimed they had been tortured.[94] In September 2013 Human Rights Watch canvassed a group of about 75 migrants who were living in a public square in Haradh. Seventy-one of them said they had been tortured in Yemen.[95] One aid worker present in Haradh during the raids estimated that the vast majority of the migrants he encountered in the camps showed signs of torture.[96] Two doctors and a nurse at the Haradh medical facility estimated that 9 out of 10 female migrants they see have been raped, along with 1 in 10 of male patients.[97]

Traffickers and smugglers acknowledge the abuse. Nadim, a trafficker who says he also serves as a ransom negotiator between other Yemeni traffickers and migrants’ families in Ethiopia, said that about two years ago he saw a trafficker tie a migrant’s penis with a rubber band so that he could not urinate and then force him to eat large quantities of watermelon. Within the last year he saw another trafficker cut off a migrant’s finger in order to take a ring. He said over the last three years he has also witnessed traffickers cut off a migrant’s ears, burn a migrant’s skin with hot water, and place a migrant’s hands under the leg of a chair and then sit on the chair.[98]

When traffickers in Haradh torture a migrant to a point near death, they often drive the person to the wall near the MRC, or to a main road, and dump the body. Sometimes passersby or soldiers find the migrant on the road and bring them to the MRC.[99] Since 2010, traffickers have dumped at least 10 bodies of migrants who died in their custody outside the MRC, said the IOM operations manager.[100] Dr. Yahya Ibrahim Jarad, the head doctor at the Haradh hospital, told Human Rights Watch in September 2013 that the hospital received an average of at least two dead migrants per week. In some periods the average climbs to as many as three or four dead per week.[101]

Ransom

Among those who spoke to Human Rights Watch who paid their way out of the camps, the lowest ransom was about US$200 and the highest more than US$1,000. Several had to pay ransom twice, after being resold or caught by a second trafficking gang. Nadim, the ransom negotiator, told Human Rights Watch that he usually negotiates a ransom of about US$1,300 each time.[102] The families of migrants who spoke to Human Rights Watch transferred the money to their captors in Yemen using international cash transfer companies with branches in Haradh.Other migrants have reported paying ransom through the hawala system, in which brokers in various countries transfer money to one another through a phone call in a trust-based network. It is especially difficult to track funds transferred under the hawala system.[103]

Ali Kebede told Human Rights Watch that traffickers he encountered in August 2013 offered migrants who had access to hawala networks better treatment because they could more easily receive their money:

When we entered the camp, the Yemeni guards asked each of us, “Do you have hawala?” Those who said yes were put on one side, those who said no, including me, were tied up and beaten. The people who said they had hawala already had relatives inside Saudi Arabia. Sometimes the smugglers called their family members to let them hear the people’s voices. From what the guards were saying, it seemed like they had a contact in every town in Saudi Arabia to collect money.[104]

After 13 days in captivity, Kebede said, he escaped without making any payment. But soon Yemeni soldiers detained him at a checkpoint on the way to Haradh and sold him to another group of traffickers. These traffickers took him to a second camp, and immediately asked him for his family’s phone number:

I gave them my mother’s phone number because I couldn’t go through the torture again. The money took some time to arrive and they kept beating me even though the money was on the way. Later my mother told me that a man from Saudi Arabia had called her. He had instructed her how to give the money to someone who would come to her village to pick it up. She had no idea that he was a trafficker at that time. He told her, “I know your son and want to help him, he has been taken by smugglers and needs money to get out.” He pretended to be a friend.[105]

Nadim described his role as a ransom negotiator to Human Rights Watch:

My friends who are traffickers in Haradh sometimes are holding migrants who are refusing to get their family to pay the ransom to free them, or their family is refusing to pay. In those cases my friends sometimes call me and I call family members who are easy to reach, either because they are based in Saudi Arabia or even in Yemen, or maybe I know someone from their village back home. I convince the family that I am trying to help their relative and have their best interests at heart. After I convince them then I negotiate the price between them and the traffickers. This is how I get paid.[106]

Traffickers used mobile phones to call Africa and Saudi Arabia to arrange money transfers, purchasing the SIM cards from local stores.[107] The practice has become so widely known that an employee at a Haradh outlet of MTN, one of Yemen’s biggest mobile phone companies, said that when a customer returns to his store soon after a purchase to buy a second SIM card, he refuses, to avoid complicity in the abuse of migrants.[108]

The period hostages spent in captivity varied; those who spoke to Human Rights Watch were held from two days to one month before being released, with or without paying ransom.

IV. After the Camps

Once traffickers receive the ransom money, they may free their hostages, smuggle them into Saudi Arabia as originally promised, or resell them to other traffickers who restart the process of extortion and torture. One migrant told Human Rights Watch that traffickers resold him directly to another group of traffickers, while others said they were later recaptured, often with the involvement of officials at government checkpoints. Several migrants said that traffickers released them once it became clear that they would not receive a ransom.

An Ethiopian migrant named Hagos Gebremedihin said he ran all night after his captors released him around 2:30 a.m. one morning. “It was sandy and extremely hot. My leg was wounded and my knees were shaking; my body was very tired. I felt like I was unconscious, like an animal moving by instinct.[109]

Many migrants have sought refuge in the Migrant Response Centre (MRC) run by the IOM in Haradh. The camp is comprised of two open areas enclosed by brick walls. In the middle of one is a makeshift tent of a tarp on posts to provide shelter from the sun. This is where the migrants sleep, eat, and spend their days as they wait to be deported back to their home countries. In the corners of both compounds there are white metal shipping containers serving as offices, medical clinics, and bedrooms for the more vulnerable migrants. On the days that Human Rights Watch visited the camp, at least 30 men were lying under the tarp, or huddled in small groups out in the sun. The two women migrants in the camp were inside one of the sweltering containers, one nursing a three-month-old baby.

Others found themselves in limbo in a dusty open square in the town of Haradh, opposite a row of small hotels that traffickers and smugglers are known to use for business meetings.[110] In the square there are piles of old mattresses, remnants of cooking fires and, in one corner, a shipping container raised one meter off the ground, on stilts. During the day, when they could not find work, men napped under this container. They installed makeshift curtains around the rim to limit dust.

Fuad Hassan Shikuri, 25, told a researcher from Human Rights Watch in September 2013 that he had been living for eight months in the square in Haradh after escaping torture in a traffickers’ camp. During the day, he said, he tried to find food and work in town, in construction or other odd jobs. At night, Shikuri and others slept huddled together in this square, near the container. He said they protected themselves from recapture with their numbers and their ferocity:

Around six months ago a group of four armed traffickers came two times in a car. They rolled down the window the first time and screamed bad words at one of my friends, so we threw everything we could find at them. They drove away. Then they came a second time and we threw things again. We damaged the car the second time and it could barely drive away. After this the traffickers have not come back.[111]

He said that because traffickers had held and tortured him and his companions and extorted fees multiple times, the traffickers knew they were unlikely to get any more money out of them. He and his friends were registered at the MRC and waiting to go home, he said, but chose not to live at the center, which he described as crowded and smelly.

Recapture

Several migrants who spoke to Human Rights Watch were recaptured by a new group of traffickers shortly after they escaped a first group. After a week in captivity in May 2013, Sindew Yimam Idris, the farmer from Wollo, escaped from a traffickers’ camp with three other Africans during a police raid, he told Human Rights Watch. They walked for nine days, picking up two other men as they traveled. Outside a restaurant in the city of Hodaida, a waiter came and offered them breakfast. “While we were eating, some men came from behind, grabbed us, and forced us into trucks,” Idris said. “Some people on the streets saw all of this happen, but they didn’t help us.” This new group of traffickers took the men to another camp. “These guards did not beat us, but they tied our arms and legs together for the entire time, even when we were eating.” After a month and a half, the traffickers released Idris and his group, who walked for seven days, avoiding main roads and checkpoints, to reach the MRC.[112]

Jemal Said, 29, told Human Rights Watch that in August 2013 the traffickers holding him captive in a camp gave up after a week and traded him and two others to other traffickers who picked them up and took them to a second camp, four hours away. There armed guards beat him with sticks, again demanding that he call his family to ask for money.[113]

Those migrants stopped at Yemeni checkpoints operated by corrupt soldiers or policemen may be detained until they are sold to traffickers. (See “Migrants’ Stories of Corrupt Checkpoint Officials.”)

Return to Ethiopia

During registration at the MRC in Haradh, intake staff ask migrants if they want to return home or not. If they want to return home, the IOM contacts their embassy in order to procure paperwork proving their identity and nationality that then allows them to board a plane home. From January 2010 to November 2013, the IOM repatriated around 17,000 Ethiopian migrants from Yemen, 10,547 of whom had registered at the MRC in Haradh. An IOM official estimated that the organization only registers 10 percent of the migrants who pass through Yemen.[114]

The Ethiopian embassy in Sanaa provides assistance to Ethiopian migrants who agree to voluntary repatriation through the IOM. Many who left Ethiopia illegally do not have passports or other necessary documents to return, and would otherwise have to pay more money to smugglers to escort them home illegally.[115]

Funding for helping economic migrants to return home is not a donor priority, and it can fluctuate yearly, according to the Regional Mixed Migration Secretariat (RMMS).[116] The IOM assisted in repatriating more than 7,000 Ethiopian migrants in 2011; 2,800 Ethiopian migrants in 2012; and 8,000 Ethiopians between January and September 2013.[117]

A 2013 RMMS study found that the governments of Yemen and Ethiopia appeared to be cooperating and using military transport aircraft to enable the return of migrants in mass deportations without adequately screening Ethiopian migrants in order to see whether they could seek asylum and remain in Yemen.[118]

V. Role of the Yemeni Government

Payoffs and Complicity

Corruption is rampant in Yemen. Transparency International ranked the country 167 out of 175 countries in 2013, with the 175th being the most corrupt.[119] Human Rights Watch has documented attacks on Yemeni journalists who publish allegations of government corruption.[120]

Human Rights Watch’s interviews indicate that government officials in Haradh often accept payments to turn a blind eye to traffickers’ activities, or otherwise assist their operations. A long-time aid worker told Human Rights Watch that many traffickers are well-known locally and that when aid groups report crimes against abused migrants to the police, officers rarely investigate in any way. “Everyone here has participated in this industry,” the aid worker said. “They are all complicit.”[121]

Smugglers and traffickers told Human Rights Watch that when transporting migrants to the Saudi border they generally avoid Yemeni government checkpoints, unless they have a working relationship with the officials there.Where there is no other route, and they have no relationship with the officials on duty, they let the migrants out of their vehicle so they can walk through the checkpoint, and they pick them up on the other side.[122] Officials manning checkpoints who are not corrupt do not stop migrants on foot.[123]

Each smuggler or trafficker has his own preferred routes to traverse the checkpoints between Haradh and the border. Smugglers told Human Rights Watch the going rates at checkpoints around Haradh on their usual route. They pay a flat fee of 500 YER (US$2) per car at two of the three checkpoints when smuggling Yemenis. When trafficking Ethiopians or other Africans, they pay a flat fee of 100 Saudi Arabian Riyals (US$27) per car at all three checkpoints if they notify the checkpoint in advance, and 500 SAR (US$133) if they do not.[124] The flat fee gives them an incentive to pack as many people as possible into the car each time.