Exploitation in the Name of Education

Uneven Progress in Ending Forced Child Begging in Senegal

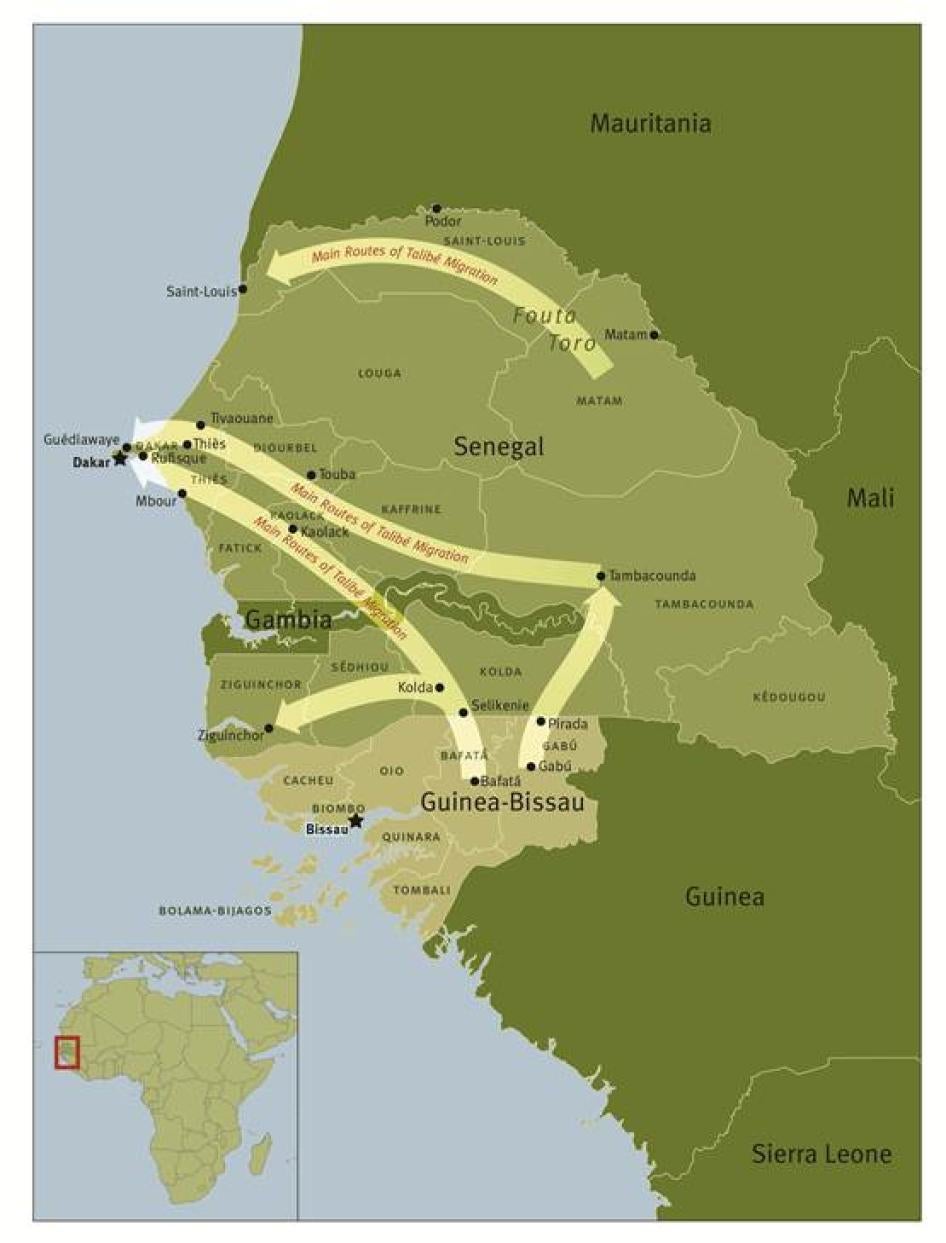

Map of Senegal and Guinea-Bissau

The main routes of migration in Senegal and Guinea-Bissau for boys in Quranic boarding schools marked by forced child begging. The routes shown are based on Human Rights Watch’s research for its 2010 report as well as studies by other organizations working on the issue. © 2010 John Emerson / Human Rights Watch

Summary

These children are in a system that benefits everyone but them…. The child works by begging for goods and for money, which will be given to his parents or taken by the Quranic teacher. And the child, 5 or 10 years later, hasn’t even finished learning the Quran.... If the country does not … care for these children and tackle the Quranic education problem once and for all, in 10 years we will have a huge problem on our hands, because we will have to deal with these children.

—Senegalese civil society activist, Dakar, January 2014

Late on March 3, 2013, a fire erupted in the Dakar neighborhood of Medina. Flames quickly engulfed a Quranic boarding school, housed in a makeshift shack; eight young boys at the school were burned to death. The teacher—and de facto guardian—was absent, having returned to his home because, in the words of one neighbor, “where the children sleep [was] unsanitary and uninhabitable.” A host of high-level government officials visited the site in the days after the fire and vowed, “Never again.”

President Macky Sall, who came to power in April 2012, promised to end forced child begging and the inhuman living conditions in certain Quranic schools, pledging: “Strong measures will be taken to end the exploitation of children, under the pretext that they are Quranic students. This tragedy demands that we intervene and identify every site like this one that exists. They will be closed and the children provided for.”

While there has been some progress, Sall’s promise remains largely unrealized one year later. After the Medina fire, authorities intervened to close only one school that threatened children’s safety, although activists say that hundreds more are easily identifiable. As a result of the lax enforcement of laws on the books, tens of thousands of boys across Senegal continue to be subjected to the practice of forced begging.

This report, which follows Human Rights Watch’s April 2010 report that documented the system of exploitation and abuse in many of Senegal’s Quranic boarding schools, examines the uneven government efforts in the year since the Medina tragedy to follow through on President Sall’s pledge. Interviews with boys experiencing such abuse and with Senegalese civil society activists working on the issue, coupled with site visits to some 25 Quranic schools in October 2013 and January 2014, revealed the serious consequences of insufficient government action.

In the town of Saint Louis, Human Rights Watch visited two Quranic schools, inhabited by boys as young as seven years old, that sit within 10 meters of a garbage dump littered with animal carcasses, old car parts, and burned refuse. In the Dakar suburb of Guédiawaye, at least 150 young boys, some no older than six, sleep in an abandoned concrete structure with no electricity or water—except for pools of rainwater—hundreds of mosquitoes, and no toilet except for the dirt floor on which they stand to bathe. Similar schools exist in other urban areas throughout the country. Many are woefully overcrowded, with 20 or more boys sharing the floor of a small room at night—or choosing instead to brave the elements outside. Diseases, from skin infections to malaria, are common, and those in charge of the schools are often negligent in obtaining treatment.

Thousands of boys at certain Quranic schools spend the majority of their day begging on the streets of Senegal’s cities. Their teacher demands that they bring back a set quota of money, uncooked rice, and sugar. The money fills his pockets. The rice and sugar are used for his family—almost never for the boys at the school, who beg for their own meals—or are bagged and sold, to make even greater profits off of the boys’ labor. When they fail to bring back the daily quota, the punishment is swift and fierce, with the teacher often meting out brutal beatings. Unsurprisingly, hundreds of boys run away each year.

The actions needed to end the exploitation and abuse of children in certain Quranic schools have long been identified by Senegalese civil society: first, introduce regulations and government oversight for Quranic schools in order to ensure standards that protect the children’s rights; and second, apply the 2005 law that criminalizes trafficking and profiting from forced begging.

Over the past year, the government has made some progress toward creating a legal framework that would regulate Quranic schools. A draft law and several draft implementing decrees that would recognize and establish oversight for Quranic schools is expected to be presented to the National Assembly in the coming months. If passed, the law and decrees would establish important norms and standards about school conditions and teacher qualifications; require that the schools submit to education and health inspections; and end the practice of begging in any school recognized by the government. An inspector in the education ministry said that, once the law is passed, authorities will close schools that exist mainly for the teacher’s benefit through exploiting children. The groundwork to swiftly and effectively apply the proposed law, including by shutting down schools where children suffer exploitation and abuse, is also being laid by the justice ministry’s anti-trafficking unit, which has done a census of almost all of the Quranic schools in the region of Dakar and plans to extend the project throughout the country.

But the real impact of the proposed law remains uncertain. There is a risk that it will merely add a new text to the many strong laws and plans that already exist in Senegal. In February 2013, the government created a detailed action plan to eradicate child begging by 2015, and in December 2013, it validated a national child protection strategy. These important achievements both referenced the need to apply the 2005 law against forced begging and trafficking. Designed in large part to tackle the exploitation and abuse in certain Quranic schools, the 2005 law has rarely been enforced, even in egregious cases, due primarily to lack of political will.

For the last decade, Senegal’s inability to end the widespread exploitation of children through forced begging has never been because of a lack of strong laws. Absent the courage and commitment to follow through and enforce the draft law that will regulate Quranic schools, the law currently under review will end up like the 2005 law against forced begging: good on paper, but irrelevant in ending abuse. Moreover, the draft regulatory law should not be seen as a substitute for the law against forced begging. The two laws can and should work together, empowering authorities to recognize and support the thousands of Quranic teachers who educate and provide for the children in their care; close schools with unsanitary conditions that endanger children’s health and safety; and arrest and prosecute those who profit from forcing young boys to beg and inflict often extreme abuse to enforce their system of exploitation.

In the year since the Medina fire, Human Rights Watch is aware of only one prosecution specifically for forced child begging—despite the widespread evidence of crimes, with thousands of boys begging in the open, often near police officers and police stations; and scores of boys in contact with state social workers after having run away from Quranic schools where they suffered extreme exploitation and abuse. As with previous governments, President Sall seems to have backtracked after an outcry from certain groups of Quranic teachers that no school should be closed and no teacher prosecuted. Yet increasingly in Senegal, civil society, imams, and many Quranic teachers are ready allies in ending abuses. A leading religious authority in Senegal’s holy city of Touba told Human Rights Watch that to call those who force kids to beg “Quranic teachers” or their places “Quranic schools” was an “insult” to the real ones.

Thousands of boys continue to toil in conditions akin to modern servitude. To protect them from further abuse, the government should not only support the country’s thousands of good Quranic teachers, but also close down schools that threaten children’s health and safety and hold accountable those who exploit and abuse children who they have been entrusted to educate and protect.

People gather at the site where at least eight boys at a Quranic boarding school died in a fire on March 3, 2013 in Dakar. © 2013 AFP/Getty Images

Recommendations

To the National Assembly

- Pass, as a matter of priority, the draft law and all draft implementing decrees related to the regulation of Quranic schools.

- Revise Article 245 of the Penal Code so that the act of begging is no longer criminalized, particularly when done by children.

To the Government of President Sall

On the Application of the Law against Forced Begging

- State publicly unambiguous support for the enforcement of

Law No. 2005-06, which criminalizes trafficking and profiting from forcing

another person to beg.

- Issue a decree or order stating that the act of forcing children to beg, including by Quranic teachers, is not covered by the exception in Penal Code Article 245.

- Issue, from the president and key ministers, instructions addressed to relevant authorities in the interior, justice, family, and education ministries stating that the law’s implementation is a priority in line with the government’s recently adopted child protection strategy.

- Enforce immediately the law against forced begging against

those who demand that boys return specific quotas of money from long hours

of begging each day and often inflict severe physical abuse to enforce

these payments.

- Instruct the police to proactively investigate the conditions of children found begging on the streets and to report cases of child exploitation and abuse to the proper judicial authorities for prosecution.

- Prioritize, through efforts already underway in the anti-trafficking unit, trainings for police, gendarmes, prosecutors, and judges on the law against forced begging, the types of cases to look for, and how to conduct proper investigations that can hold up in a court of law.

- Ensure that prosecutors and investigative judges operate in full independence of the Executive and are able to pursue cases of child exploitation and abuse without interference or consequences.

- Communicate effectively with religious leaders and the

general population about the enforcement of the law, making clear that

authorities will only target those who engage in exploitation and abuse of

boys in their charge.

- Publish communiqués that outline the facts behind convictions for forced begging, to better explain to the public and religious authorities the necessity of such action.

- Consider issuing an amendment to the law against forced begging to provide for a greater range of penalties, modifying the current punishment of mandatory two- to five year prison sentences to include prison sentences under two years as well as non-custodial sentences, so that punishments can be better apportioned to the severity of exploitation.

- Publish every six months, based on the recently concluded agreement between the justice and interior ministries, statistics associated with anti-trafficking efforts, including arrests, charges, and convictions. Collate and publish statistics specifically on arrests, charges, and convictions related to forced begging.

- Organize a meeting with religious authorities—including the Caliphs, leading imams, and Quranic teachers—with a view to issue a joint statement supporting the application of the law against those who exploit boys through forced begging.

On the Regulation of Quranic Schools

- Take immediate steps to remove children from schools that violate their rights to health, education, and freedom from exploitation and physical or emotional abuse. Work with civil society to temporarily place such children in shelters already identified by the family ministry, while undertaking family tracing to return the children to their parents.

- Publicize swiftly and widely the law regulating Quranic schools, once passed by the National Assembly. Translate the relevant laws and implementing decrees in local languages and disseminate them through key outlets, including community radios around the country.

- Establish a hotline for people to report Quranic schools that appear to have unsanitary or dangerous conditions or whose students are often seen begging, facilitating inspections by relevant state officials.

- Ensure that there are adequate inspectors responsible for overseeing that Quranic schools meet minimum conditions that protect children’s rights to health, education, and freedom from exploitation and abuse. Ensure that the inspectors regularly conduct unannounced site visits and close sites that do not meet standards that protect the best interests of the child.

- Collect and systematically make public statistics on the number of site visits conducted by inspectors; the number of schools identified as not meeting basic standards; and the actions taken when such schools are identified.

- Provide additional financial and logistical support to the anti-trafficking unit, so that it can continue its exhaustive mapping of Quranic schools countrywide.

To International Donors

- Consider providing increased budgetary support for the justice ministry’s anti-trafficking unit, in particular in regards to its efforts to enforce the law against forced begging and to conduct an exhaustive mapping of Quranic schools across the country.

- Consider providing budgetary, technical, and logistical support to relevant authorities in the education ministry responsible for inspecting and overseeing appropriate conditions in schools, including Quranic schools.

For more detailed recommendations, see Human Rights Watch’s April 2010 report, “Off the Backs of the Children.”

Methodology

This report is based primarily on research missions to Senegal in October 2013 and January 2014, each lasting around two weeks. The research was conducted in the capital Dakar and its suburbs; the cities of Saint Louis, Diourbel, and Touba; as well as several villages between Diourbel and Touba. Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 60 people in total, including Senegalese civil society activists; Quranic teachers; current and former students from both model Quranic schools and schools where exploitation and abuse is rife; religious authorities from Senegal’s brotherhoods; Senegalese academics on Islam and the history of Quranic education; representatives of the United Nations, diplomatic missions, and humanitarian organizations; and government officials in the justice, education, and family ministries. The report examines the mixed record of President Sall’s government in addressing forced begging and unsafe living conditions in certain Quranic boarding schools—particularly in the year after a fire at one such school killed eight boys.

Interviews were conducted individually, with the presence in some cases of Senegalese civil society activists who knew and introduced the person to Human Rights Watch. Interviews with children, Quranic teachers, and some religious authorities were conducted with the use of an interpreter between French and either Wolof or Pulaar. Human Rights Watch did not offer interviewees any incentive, and people were able to end the interview at any time. Throughout the report, names and identifying information of some interviewees have been withheld to protect their privacy. Some people spoke on the condition of anonymity, out of fear of repercussions for voicing criticisms.

The work builds on 11 weeks of field research that Human Rights Watch conducted in 2009 and 2010, which formed the basis of the April 2010 report “Off the Backs of the Children”: Forced Begging and Other Abuses against Talibés in Senegal. That report provides a much more detailed account of the history of Quranic education in Senegal, the rise of exploitation and abuse in certain schools, and the experiences of young boys in such schools. The 2010 report was based on interviews with 175 children who were current or former students in Quranic schools; 33 Quranic teachers and imams; 20 families in Senegalese and Bissau-Guinean villages who had sent their children to Quranic schools; national and local government officials in Senegal and Guinea-Bissau; academics and religious historians; and representatives from diplomatic missions as well as national and international organizations working on the issue of forced child begging.

This report is organized according to the two overarching issues that Senegalese civil society and many government officials identify as the keys to ending the widespread exploitation and abuse of young boys at certain Quranic schools. Section I examines government measures to end the longstanding lack of regulation of Quranic schools, which has allowed certain teachers to open schools in unsanitary, unsafe conditions. Section II examines the scant enforcement of the country’s law against trafficking and forced begging, which has allowed certain men to manipulate traditional education into a business built on the labor of young boys forced to beg for long hours.

Throughout the report, Human Rights Watch will at times put in quotes words like “Quranic school” or “teacher,” to signify that the proper meaning of those terms hardly applies when boys spend most of their time begging to meet the “teacher’s” daily demand for a specific amount of money. Many Senegalese civil society activists and religious authorities routinely refer to the abusive and exploitative places as “so-called Quranic schools” or “self-proclaimed Quranic schools”—to distinguish them from the thousands of daaras, or Quranic schools, where children do not beg, are well cared for by the marabout, or Quranic teacher, and receive a strong religious and moral education. However, because the places present themselves as “Quranic schools”—and the children do spend some time learning the Quran, even if significantly less than they spend on the street begging—it remains the most appropriate terminology.

I. Regulation of Quranic Schools

The draft law to regulate the daaras[1] is a good thing, but in the past, the government has been quick to say it was going to do something, but then [not follow through]…. Applying the law could pose a problem, just as with the law [against forced begging].

—Senegalese civil society activist[2]

In the 2010 report, Human Rights Watch documented how the lack of regulation of Quranic schools—including schools where young boys live, far from their families—had allowed for the proliferation of schools where teachers twisted religious education into economic exploitation. A leading Senegalese civil society activist on the talibé,[3] or Quranic student, issue explained in January that this remains a core problem:

When an educational gap exists and no monitoring mechanisms are put into place … there will always be people who take advantage of the situation…. [S]ince there is no monitoring, simply anybody can open a daara, anywhere and anyhow, provided that that person looks the part. I could go into a neighborhood where nobody knows me today, dressed exactly as I am, and become a Quranic teacher, even if I know I don’t know the Quran, simply because there are no measures for monitoring and reporting [bad daaras]. So what happens? There are some Quranic teachers who are good, who were trained in the best schools, who are truly Quranic scholars…. There are others who take advantage of the system in order to exploit children through begging. This is why there is such chaos today…. Some students are at Quranic schools for 10 years and know nothing of the Quran. The Quranic teacher is getting rich. Some get so rich that they leave the country to live abroad. Others make the children work so they can build big houses. The problem is the lack of monitoring, inadequate regulation.[4]

In general, boys in Quranic boarding schools in urban Senegal come from the poorest, rural regions of the country as well as from neighboring countries, particularly Guinea-Bissau.[5] Many parents who send children to such schools appear motivated by a desire for the child to memorize the Quran and obtain a moral education. For some parents, however, the decision is rooted in neglect; by confiding a child to a Quranic teacher, it becomes the teacher’s responsibility, and no longer their own, to feed, house, and care for the child.[6] Many of the abusive Quranic teachers themselves hail from poor, rural villages and have used the lack of regulation to set up “schools” where they enrich themselves through the children’s labor, as described by the activist above. Some of these “teachers” bring back money or bags of rice to families who have sent them a child, creating a web of exploitation based around the child’s begging.[7]

In the year since the Medina fire, President Macky Sall’s government has made notable progress toward introducing basic standards for Quranic schools and Quranic teachers. A draft law and four draft implementing decrees all designed to regulate and oversee Quranic schools are currently in the pipeline for the National Assembly. Passing the law and decrees would constitute an important step forward.

At the same time, as discussed in more detail in Section II below, Senegal already has strong laws and policies that could be used to end the practice of forced child begging, but these laws are almost never enforced. While the new law will provide a different and, in some respects, potentially more effective tool to improve the situation of all children attending Quranic schools, it will only succeed if there is the political determination and financial support to enforce the law.

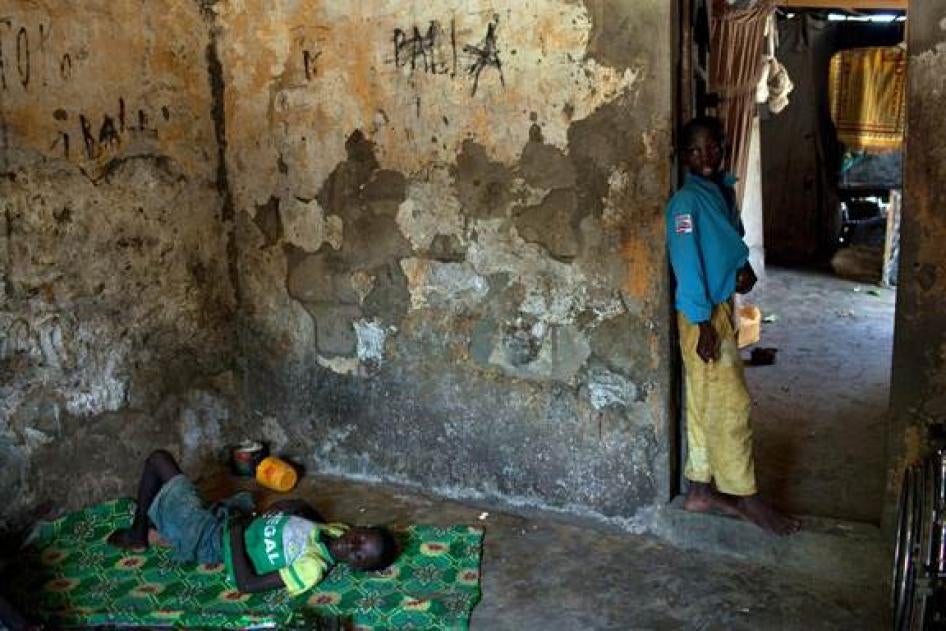

Two boys, one of whom is ill, at a Quranic boarding school in Saint Louis, Senegal, October 4, 2012. © 2012 Holly Pickett/Redux

Unsafe Living Conditions in Quranic Schools Marked by Abuse

Human Rights Watch’s 2010 report described in detail how certain Quranic teachers open schools in dilapidated shacks or abandoned houses that are completely unfit for living, particularly for young children. Diseases—from skin infections to malaria—are rampant due to the unsanitary and overcrowded conditions, and the boys are often left to seek treatment on their own. The follow-up research in October 2013 and January 2014 showed that this remains a widespread problem, even in the aftermath of the fire in the Medina daara.

In the Golf Sud neighborhood of a Dakar suburb, Human Rights Watch visited a Quranic boarding school in January 2014 where over 150 talibés from Guinea-Bissau reside, crammed 20 to 30 to a room at night in an unfinished and abandoned concrete structure. Boys there said that they are forced to beg for 500 francs CFA (US$1) a day. The Quranic teacher lives comfortably with his family in a home about a kilometer away, leaving the school—and boys as young as six years old—in the care of older students in their teens and early 20s. There is no electricity or water, and the boys use the same dirt floor as both a toilet and a place to bathe. They sleep on the concrete floor or on thin mats in rooms that, even on a cloudless afternoon, are pitch black. Except for winter, many boys sleep outside in the open air to avoid stifling heat. Without windows or doors, the place routinely floods during the rainy season. Dozens of mosquitoes drone in every room.[8]

Human Rights Watch has visited dozens of similar shacks, abandoned houses, and unfinished buildings that serve as Quranic boarding schools. In Saint Louis, a town some 250 kilometers north of Dakar, Human Rights Watch visited two Quranic schools that were located within 10 meters of a large trash dump, filled with batteries, old car parts, and animal carcasses. Some talibés in Saint Louis describe digging through the trash to find scrap metal or plastic bottles they can sell to meet their begging quota. During a night round with a talibé activist in Saint Louis in January 2014, Human Rights Watch stumbled across a small Quranic school—no bigger than 5 meters by 3 meters—in which some 25 boys were crammed. The older boys had drawn lines in the sand floor that the younger boys could not cross—this allowed the older boys to lie fully down, but obliged the younger ones to stack on top of each other in a pyramid of arms and legs.

Boys sleep in the crowded room that serves as their classroom and living quarters at a Quranic school in the Medina Gounass suburb of Dakar, Senegal, September 24, 2013. © Rebecca Blackwell/Associated Press

A talibé activist in Saint Louis, who provides medical care for boys from Quranic schools and tries to improve the schools’ conditions, described the often poor living situation:

[Some of the] traditional daaras are a laughingstock. They are in ruins and totally out of line with how a daara should be.... If the Quranic teacher lived with them, it would be a different story. But [he] has a house nearby and forces the children to live in an abandoned building or builds a tiny hovel where he makes 30 kids live. When you see 50 children living in two rooms, you can no longer call that a daara. It’s simply exploitation. And it’s from this that we say that certain people who are Quranic teachers are exploiting children. They force them to beg.... It’s the children who dress themselves. It’s the children who feed themselves. It’s the children who keep themselves clean…. Many children who come here for treatment have bad skin problems…. They have roundworms and lice. We treat scabies….

We have been to some daaras to ask the Quranic teacher to remove all the clothes and burn them, because there are lice and fleas in the daara and each time we treat the children and they heal, the illness returns. Why? Because the daara is abominable. We have to go in there with our machine to disinfect the entire daara…. We also often offer mats to the Quranic teacher so that [the children] at least have something to sleep on. But some [teachers] don’t use the mats [in the daara]. They take them to their village or their own home. I have visited Quranic teachers who we have given mats to. I have sat down on a mat that we had given to [the Quranic teacher] for the children, but instead it was at his house. So, you see, we have the sense that these Quranic teachers do nothing to make sure the children are healthy and clean, nor do they provide a healthy living environment. The only thing that [the teacher] cares about is whether or not the child brings him [what he demands each day]….[9]

If the draft law regulating daaras is to mean anything, it must spell the end of thousands of boys living in structures that endanger their health and safety. Such schools are a stark reminder of the tragic fire in Medina in which eight young boys died. According to witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch, the Quranic teacher was not present when the fire erupted around 10 p.m. on March 3, in the small shack where some 50 boys occupied two rooms.[10] As a neighbor of the daara told Human Rights Watch:

[The Quranic teacher] would sometimes come in the evening to collect the money that [the boys] had begged for, but then he would go home because he lived elsewhere…. Most Quranic teachers [at bad daaras] don’t live at the same place as the children … because where the children sleep is unsanitary and uninhabitable…. Things like [the fire], you hope to never see them again. But unfortunately, there are other daaras in Dakar similar to this one…. The daaras in slums, hovels, and shacks should be closed. There should only be modern, habitable daaras…. Otherwise this will happen again.[11]

A civil society leader working on the talibé issue described the abusive conditions in a Quranic school he recently visited and called on the government to fulfill its promises:

There’s a place not far from here … near the swamps in HLM. There is a daara with over 250 children that live in a dilapidated building. The children go into the swamp and drink the water, along with lizards and other animals. They bathe in the swamp. And nobody says anything. Why? Because the government is often timid, because it’s easy to hit a nerve when talking about religion, and sometimes people are afraid of that.

People are scared. But we can’t remain silent here in Senegal. When the government backed away from measures that were [promised after the Medina fire], rumor had it that the Quranic teachers said, ‘We’re going to take our prayer beads, do what we want to do, and the President will go away.’ Yes. But I think—and I know I’m nobody and my job is not at stake—I think that beyond all these religious beliefs, we have to look at the crux of the matter. What will tomorrow look like? We have to build the Senegal of tomorrow together…. Today we should concentrate our most important efforts on the future of these children…. That’s what I’m asking the government to do … make good on its commitments and take action.[12]

As described in Human Rights Watch’s 2010 report and further documented here, the living conditions in certain Quranic schools violate the government’s obligations under the Convention on the Rights of the Child and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child with respect to the boys’ rights to life, health, physical and mental development, education, and recreation and leisure.[13]

A talibé in Saint Louis, Senegal, suffers from a skin disease. © 2013 Issa Kouyaté/Maison de la Gare

Government Efforts to Introduce Regulations, Minimum Standards

For more than a decade, governments in Senegal have promised to modernize Quranic schools so that they meet minimum standards that protect children’s rights and provide quality education. During the last year, President Sall’s government has moved closer to realizing that promise than ever before. A draft law that would establish legal status, oversight, and regulation of the country’s Quranic schools is at an advanced stage.

Human Rights Watch saw a version of the draft law and implementing decrees, dated October 23, 2013. The draft implementing decrees included articles related to the opening of a Quranic school, the qualifications of Quranic teachers, the hours and quality of education, and a requirement to submit to inspections by the education and health ministries. Of particular importance, one of the implementing decrees requires that Quranic schools “give up the practice of begging.”[14] Quranic schools that meet these minimum standards would be formally recognized by the education ministry, with the potential for subsidies and other incentives for the school and teacher.

An official in the education ministry’s daara inspectorate told Human Rights Watch that all of the relevant ministries and divisions had reviewed and commented on the draft law. He said the government would soon present the draft law to the National Assembly, where he hoped it would be passed promptly.[15] The official said that, once the law is passed, “there will be daaras that we will close, those that we call ‘daaras’ but in reality aren’t there for true religious education. They’re there for the [Quranic teacher’s] own gain.”[16]

The groundwork to swiftly and effectively apply the draft law, shutting down “schools” where children are exploited or live in dangerous conditions, is also being laid by the justice ministry’s anti-trafficking unit.[17] The unit is currently overseeing an exhaustive mapping of daaras in the region of Dakar, identifying and obtaining information on more than 1,000 daaras there.[18] It envisions expanding its work nationwide, mapping daaras throughout the country to identify those where children’s rights appear to be respected, those where abuses are taking place but could be remedied quickly with support, and those where conditions are so deplorable that the “schools” need to be swiftly closed.[19] A high-level official in the justice ministry explained:

It’s very easy. Once the law has been voted, we know where the [abusive] daaras are [in Dakar, as a result of the mapping], and we will apply the law. The interior ministry, justice ministry, and anti-trafficking unit don’t exist for nothing. Instead of adults taking care of children, in these schools—or fake schools—you have little children feeding—enriching—the adults. In a country based on laws, this can’t be allowed.[20]

Finally, the government, with significant funding support from the Islamic Development Bank, is in the process of building 64 “model daaras,” whose curriculum will include mastering the Quran as well as the core subjects in public schools, such as reading, arithmetic, and French.[21] The model daaras will be built in seven administrative regions around the country; half of the schools will be state-run and half will be privately run, with the government responsible for inspecting conditions and overseeing the curriculum in all of them.[22] An official in the education ministry said that each school should be able to house at least 320 children across eight grade levels.[23] The government will need to ensure that the schools service not only the wealthy, mostly urban Senegalese, but also the poor, rural populations which produce many of the boys currently toiling in Quranic boarding schools where exploitation and abuse is constant. The areas of Senegal from which a disproportionate number of these boys originate should be targeted particularly in the construction of model daaras. A Senegalese civil society activist also stressed the importance of supporting village daaras, so that children can stay with their parents and combine attending a village primary school with learning the Quran.[24]

A boy who had fallen ill rests inside one of the small rooms at a Quranic boarding school in Saint Louis, Senegal, October 4, 2012. © 2012 Holly Pickett/Redux

Factors that Threaten Progress in Realizing Minimum Standards

As noted in the quote from a civil society activist at the outset of this section, if the National Assembly passes the law and implementing decrees to provide oversight and regulation of Quranic schools, it will be a big step forward. At the same time, the law will only succeed in protecting children from abuse and exploitation if it is actually applied and leads to the closure of schools that violate children’s rights to health, food, physical and mental development, and freedom from exploitation. Officials from the education ministry will have to consistently monitor whether schools meet the standards outlined under the law and, when they do not, work together with officials in the family, interior, and justice ministries to close such schools, place children in a temporary, protective environment, and ultimately return them to their families. Realizing minimum standards that protect children’s rights will require political support from the president and relevant ministers as well as the financial means to enforce the law—two areas in which previous governments have consistently fallen short when dealing with issues related to Quranic schools.

Need for Political Will and Courage

Building model daaras and supporting Quranic teachers who run exemplary schools is commendable, but the real test of the government’s commitment to protect children from exploitation and abuse will come in whether it follows through and closes “schools” where the violation of children’s rights is not immediately remediable. In many ways, the legal framework for such action already exists, through the 2005 law against forced begging (see Section II for a more detailed discussion). Yet authorities have applied this law in only the rarest of circumstances, effectively allowing for the continued proliferation of schools where boys are exploited and live in deplorable conditions.

Several government officials told Human Rights Watch that Quranic teachers and Senegalese society more generally will be more accepting of the new law as a means for widespread intervention, because it will involve closing schools with inhuman living conditions—within a broader framework of supporting good Quranic schools—rather than prosecuting men seen by some as religious figures.[25] There are reasons to be skeptical.

In the aftermath of the fire in Medina in March 2013, the Dakar suburb of Guédiawaye showed both how things should ideally work and how progress remains blocked. Neighbors and civil society activists identified four Quranic schools that presented dangerous conditions that “might have led to the next Medina.”[26] Working with local government officials, one school was closed; the children spent a week at local shelters, before being returned to their villages, primarily in central Senegal. One activist involved in the process said that there was “real synergy, everyone was working together—civil society, the population, the local child protection committee, and [local government officials]. Civil society got rid of all obstacles, making sure that shelters and other sites were ready to house the kids. But then we ran into problems.”[27]

After returning the boys from the first daara, the same actors readied to close the second identified daara. But central government officials reportedly stopped them. One person involved in the process said that the local child protection committee ran out of financing, with neither the central government nor key international donors willing to provide the funds required to go ahead with the other three daaras.[28] Another person reported that the problem was primarily about the lack of government will, indicating that local government officials had said that government officials at the highest levels in Dakar “had not yet decided to go ahead with closing [abusive] daaras. They said we could not continue, because there wasn’t the political support [for such action].”[29] The three other daaras that had been identified continue to operate in Guédiawaye in the same exploitative conditions, with long hours of forced begging and living situations that threaten the health and safety of the boys who live there.[30]

Need for Financial Commitment to Enforce Regulations

In addition to political will, effectively regulating Quranic schools will require resources to perform routine inspections; sanction and, when necessary, close schools in violation of the law; move boys into an environment that protects their basic rights; and, in many cases, trace the boys’ family and reunify them. At present, the relevant government bodies are understaffed and underfunded to an extent that would severely undermine implementation.[31]

The education ministry’s daara inspectorate has eight full-time staff, including two inspectors.[32] To cover the tens of thousands of daaras across Senegal—there are more than 1,000 each in Dakar and Touba alone—the inspectorate relies on local “inspectors of Arabic teaching,” who, in addition to Quranic schools, are responsible for inspecting Arabic classes in public schools as well as private French-Arabic schools.[33] At present, there is not even an inspector of Arabic teaching for each administrative department in the country.[34] Even if there were, the idea that the current staffing levels could safeguard standards at all of these schools is fanciful, as described by an official in the daara inspectorate: “If we’re going to inspect or even oversee inspections across Senegal, we need more personnel, we need more equipment. Many inspectors don’t have cars.”[35] He said that, as of now, they planned for each field inspector to perform at least one monitoring mission per month, with the head inspectors from Dakar doing one each three months.[36] Although an improvement over the current situation, this level of monitoring would barely scratch the surface in identifying schools that pose a significant threat to children’s well-being.

Greater support for implementing the draft law will be crucial, while recognizing Senegal’s budget constraints—a problem that runs through children’s rights policy more generally. In December 2013, the Senegalese government took the positive step of passing a national child protection strategy, which the government has said will form the basis for future actions. The strategy specifically identifies the problem of child begging and calls on the government to enforce laws and policies that will protect children from such abuse. The strategy should also help improve coordination between the various ministries that work on children’s rights issues, including the ministries of justice, family, education, health, and interior. A representative from one diplomatic mission said that the national strategy was “very well thought through, but there wasn’t the money” to fully implement it.[37]

The government should seek out efficient, low-cost ways to facilitate implementation of the draft law and decrees that will regulate Quranic schools. For example, the government should consider establishing a hotline within the education ministry’s daara inspectorate and division of Arabic teaching, allowing civil society representatives and the general population to call and identify schools from which children beg or in which they face substandard conditions that threaten their health and safety.

Allies in Waiting: Religious Leaders and Many Quranic TeachersSenegalese civil society activists as well as some mid-level government officials said that both the previous government of President Abdoulaye Wade and the current government of President Macky Sall backed down, to varying degrees, from their promises to eradicate forced child begging after certain Quranic teachers accused the government of attacking Islam and Quranic education.[38] Yet in reneging on their commitments, both governments failed to realize that, rather than foes, the country’s preeminent religious leaders as well as many Quranic teachers are ready allies. A justice ministry official said, “The paradox is that most of the population is against this, even most of the religious leaders are against this—they want the application of the law [against forced begging]. The government often backs down when there is an outcry from certain groups of Quranic teachers, but they are in the minority.”[39] In the aftermath of the Medina fire, the Association of Imams in Senegal came out in strong support of government efforts to end child begging, saying, according to local media reports, that the practice of forcing talibés to beg for money taught them “lying and stealing, which are behaviors barred by the Muslim religion.”[40] Human Rights Watch interviewed more than a dozen Quranic teachers in Touba, Diourbel, Saint Louis, and Dakar who expressed similar support for government action to stop exploitation through begging. A respected religious authority in Diourbel, who also heads a Quranic teachers’ association, said that stories of boys in Quranic schools being forced to bring back a daily quota of money “really anger me.” He continued: To hear so often that these so-called Quranic teachers exploit children like this, it’s not at all okay. It’s these bad Quranic teachers that lead to the problem of street children, that lead to children having to steal [to get the demanded money]. The authorities should get on the ground, identify those who are doing this, and take measures to settle the problem for good. [41] Another Quranic teacher, from a village between Diourbel and Touba, said: All too often, there are self-proclaimed Quranic teachers who go to cities in search for money. A true daara is about education, the Quran, not money…. We’re in the era of ‘rights,’ this practice of begging is not acceptable…. The government should step in to regulate Quranic schools and teachers. That will allow it to get rid of [the abusive ones].[42] Many Quranic teachers go above and beyond in supporting children in their care. Human Rights Watch visited several Quranic schools in Diourbel where the teachers systematically enrolled Quranic boarding students in the local, public schools—so that children went through public school coursework at the same time they memorized the Quran at the daara. Without any financial support from parents, the teachers house and feed the boys and oversee clean daaras. One such teacher said of his decision to enroll boys in public school: “It’s absolutely necessary so that the boys can thrive in the world. Even before the government started talking about modernizing, we modernized on our own.”[43] In addition to Quranic teachers, the government could make allies with the highest religious authorities in Senegal. In 2010 and again in January 2014, Human Rights Watch met with key authorities from the Tidjane and Mouride religious families, the two largest and most powerful brotherhoods in Senegal. They unanimously expressed opposition to the scourge of boys from Quranic schools begging on the streets. Sokhna Mame Issa Mbacké, a descendant of the brother of the Mouride founder, Cheikh Amadou Bamba, and supporter of 13 modern daaras where boys and girls also learn French, Arabic, science, and computer literacy, told Human Rights Watch: “Comparing those who exploit children through begging to real Quranic teachers is an insult to the real teachers.”[44] Sokhna Maï Mbacké, the daughter of the third Mouride caliph, Serigne Abdoul Ahad Mbacké, similarly expressed outrage over those “who say that they are bringing kids to Touba to learn [the Quran], but then force them to work, to beg. Then when the so-called Quranic teacher goes back to his village during the harvest, he brings back money, bags of rice, and sugar from the boys’ work. This has to be denounced.”[45] Several religious leaders in Touba told Human Rights Watch that some abusive Quranic teachers had fled Dakar for Touba after authorities prosecuted several Quranic teachers in Dakar in September 2010. As a result, the religious leaders said, the problem of child begging had increased in the holy city, with abusive “teachers” there demanding that boys bring back 400 to 750 francs CFA ($0.80 to $1.50) a day. Idrissa Cissé N’Diaye, a prominent official on Touba’s Rural Council (le Conseil rural de Touba-Mosquée), the highest political and moral authority for the semi-autonomous holy city, told Human Rights Watch that he had overseen a mapping of the daaras in Touba. Of the 1,274 daaras that had been identified, he said that “less than 700 of them exist according to the appropriate norms and criteria.”[46] He continued: There are people who come and set themselves up in a shack or an unfinished building, claiming that they are trained in Quranic studies but really aren’t. [Many of them] don’t have but 25 to 50 kids. These aren’t ‘daaras.’ … These are men who don’t have any source of revenue, so they use—exploit—children to make a living…. These ‘schools’ do not deserve to be kept in place…. We tell those in charge to disappear, and we’ll work to put the kids in real daaras. A child’s place is in school, not on the street. [47] The president of the Rural Council’s commission on education and religious affairs, Serigne Moustapha Diattara, said that the council was crafting its own plan to end the problem of forced begging in Touba. He said there would be a committee to regulate all daaras in Touba, including by testing a Quranic teacher’s knowledge before allowing him to open a school, establishing a set curriculum, and ensuring that the schools meet basic standards that protect children’s rights. He said the proposal was awaiting validation by the Caliph before being implemented. He also stressed: “From the beginning to the end of the Quran, there is nothing [authorizing] the begging or mistreatment of children…. The Quran is about sanctity and piety, this practice of forced begging is not of the Quran. Those who are doing this, they should learn the Quran. They’re taking kids and exploiting them.”[48] Several local activists and mid-level government officials suggested that President Sall should bring together the heads of the religious families in Senegal, as well as key imams and leaders from progressive Quranic teachers’ associations, to issue a joint statement of support for closing schools where children live in unsafe conditions and for applying the law against those who exploit young boys through forced begging (see Section II, below). At a minimum, the government should stop backtracking every time certain groups of Quranic teachers—often those who profit greatly from the status quo—cause an uproar. Many other religious authorities support government efforts to end forced child begging. |

II. Application of the Law against Forced Begging

As we’re working to establish modern daaras, we also need to crack down on those who exploit boys at self-proclaimed Quranic schools. Those who force children to bring back money each day, they aren’t teaching, they’re exploiting—they’re modern-day slave drivers.

—Alioune Tine, President of Senegal’s Human Rights Commission[49]

As described in detail in Human Rights Watch’s 2010 report, thousands of young boys are forced to spend long hours on the streets of Senegal’s cities each day begging for money, uncooked rice, and sugar to bring back to the person who oversees their Quranic boarding school. In the worst “schools,” the boys are systematically beaten if they fail to return with a set amount of money, which almost exclusively goes to the benefit of the “teacher” and his family. Some “teachers” inflict punishments against young boys that could qualify as torture, including by brutally beating them, burning them with caustic substances like the sap from raw cashew nuts, and forcing them to remain in stress positions.[50]

In 2005, the National Assembly passed an anti-trafficking law that made it a serious crime for anyone to “organize the begging of another in order to make a profit.”[51] The law was squarely aimed at attacking the problem of forced begging in certain Quranic schools, but there has been scant application over the subsequent decade, except for a brief period in September 2010 under the Wade government. Under pressure from international partners, nine Quranic teachers were convicted during a period of several weeks, leading to an exodus of child beggars from the streets of Dakar.[52] However, during a Council of Ministers meeting in October 2010, Wade said that he disagreed with the actions.[53] The prosecutions stopped, and thousands of children quickly returned to the streets and resumed begging to meet their daily quota.

In the aftermath of the Medina fire, President Sall’s government promised the swift and resolute application of the law against forced begging.[54] Civil society activists told Human Rights Watch that, once again, the streets largely emptied. But as the commitment to apply the law appeared to waver, some Quranic teachers sent children back out to beg. One year later, with few exceptions—including a notable case in January 2014—the law remains unenforced, due largely, in the words of both civil society and many government officials, to a lack of political courage. There are promising signs that this may be changing, however, due in particular to strong leadership from high-level officials in the justice ministry, including the head of the anti-trafficking unit.

A young boy from a Quranic school begs for change from a driver stopped at a gas station, in the Medina Gounass suburb of Dakar, Senegal, September 24, 2013. © 2013 Rebecca Blackwell/Associated Press

Exploitation and Abuse through Forced Begging

Each day in the poor suburbs of Dakar, boys can be seen hopping aboard public transport to head downtown, where they beg all day for money, uncooked rice, and sugar—as well as their own meals. Each evening, many head back out to hand over their day’s earnings to the Quranic “teacher.”[55] Some boys stay behind and sleep on the streets, afraid of the beating that will come if they fail to obtain the daily demanded sum. Others choose the beating from a whip or an electrical cord over sleeping on the streets. Each day, this is repeated in major cities across the country.

At “schools” overseen by exploitative Quranic teachers, the focus is not on education, religious or otherwise, but on the accumulation of money for the “teacher.” A Senegalese civil society activist explained:

These are Senegalese children who are victims of their parents and of dubious so-called Quranic teachers who are exploiting them for their own gain…. If a Quranic teacher doesn’t have any qualifications … what does he do? He stays in a situation in which he expects others to financially support him. That’s the problem. Who supports him financially? The child. Who does what? The child works. It’s the opposite of how it should be.[56]

In a recent mapping of daaras in the region of Dakar, investigators from civil society found that boys in Quranic schools where teachers force them to beg spend an average of at least six hours a day on the streets looking for money and food.[57] As detailed in Human Rights Watch’s 2010 report, young boys in Dakar often have to bring their Quranic “teacher” between 300 and 1,000 francs CFA ($0.60 to $2) a day. In other major cities, the demanded sum is often lower, somewhere between 150 and 500 francs CFA ($0.35 to $1). With dozens of boys working for them seven days a week, exploitative Quranic teachers amass earnings well beyond what a mid-level government official—much less the average resident of Senegal—makes.[58]

At dawn, a baker breaks off pieces of a baguette for talibés, in the Medina Gounass suburb of Dakar, Senegal, September 24, 2013. Boys at some Quranic schools have to beg not only for their daily money quota, but also for food for themselves. © 2013 Rebecca Blackwell/Associated Press

In addition to money, many “teachers” demand that boys bring back quotas of uncooked rice and sugar cubes.[59] In schools run for the teacher’s profit, this food does not go to the boys, but rather serves as an additional source of income for the teacher.[60] A civil society activist in Saint Louis described watching boys in several schools stack their sugar cubes in boxes and pour uncooked rice into sacks in the teachers’ home, which the teachers then sell for profit at small shops they run.[61] Human Rights Watch has seen several such shops and, during the course of its 2010 research, interviewed scores of current and former talibés who said that the uncooked rice and sugar was never used for their benefit—but instead always packed up for the teacher’s family to use or, most often, to sell.[62]

Many boys describe their overriding feeling as one of fear—fear of the punishment they will face if they fail to collect the demanded money quota. While some “teachers” give one or two warnings, any additional failure to hand over the quota results in often extreme physical abuse—to ensure the boy never again fails to beg long enough. An 8-year-old boy interviewed in January 2014, who reported having to bring his Quranic teacher 200 francs CFA ($0.40), 500 grams of uncooked rice (worth 150 francs CFA, or $0.35), and 10 sugar cubes each day, said: “I work and sweat until I have the quota…. Sometimes I go back out [to the streets] after 5 p.m. to look for my quota…. If I have it, [the Quranic teacher] won’t beat me. But if I don’t have it, he will beat me.”[63]

A 10-year old boy interviewed in January 2014 explained similarly:

We wake up at 7 a.m., and we go and beg. We’re out there until about 9 a.m. We come back, give 25 francs CFA ($0.05) and [500 grams of uncooked] rice [to the Quranic teacher]…. We stay [at the school] and study the Quran until 10 a.m. After that, we go back to the market [to beg] … until 3 p.m., then study until 5 p.m. Then we go back to the market [to beg] for a bit…. When we’re finished we each have to give 200 francs CFA ($0.40)…. If you don’t have your quota, you tell him, ‘I don’t have my quota, tomorrow I will bring it.’ Then the next day you have bring 400 francs CFA ($.80)…. [If you can’t get the 400 francs CFA the next day], then he will beat you. He beats us with a horse whip…. [When he hits you,] you just think about your home…. When they beat us [at the Quranic school], it’s painful. But when you’re at your home, no one hits you.[64]

An activist in Saint Louis who works closely with current and runaway talibés described some of the typical and more extreme cases he has recently observed:

The [abusive] Quranic teachers have techniques for hurting [the children]. It’s torture for a child who is 7, 8, or, at the most, 12 years old. They hurt them because they didn’t bring their daily quota or they didn’t learn their Quranic lesson…. [The boys] are beaten on their back with chains, tires—the detached inside edge of tires. Or they’re beaten with wet ropes. They often use what are called ‘12 centimeter ropes,’ thick ropes that are used to tie up cattle. They soak the rope in water until it’s fully wet and then use it in beatings. They say [wet ropes] don’t hurt you on the surface but rather below the surface…. Many children … the first thing we have to do is look at their body. When you look at these children’s backs, it’s unbelievable….

There is [also] something called ‘djingue.’ When I think of it, slavery comes to mind. Why? Because the word ‘djingue’ means to tie someone up until they can’t move anymore. There are daaras that have special punishment rooms. In the punishment room, you’ll often find an object called a ‘djingue.’ A child who runs away often is tied up…. There is a particular type of pole. A chain is fed through the pole, entering one end and exiting the other. They take the chain and wrap it around the child’s wrists, locking it with a padlock…. The child can’t move anymore because all four [limbs are attached]. Both wrists and both ankles are attached together and the child has to sit on them…. After only an hour you are suffering, and [in some daaras I know] they have to stay that way for a whole day…. They do it so that it hurts and so that the boy won’t run away anymore. If he is caught another time, he knows what will happen to him.[65]

As a result of the fear of serious physical abuse, many boys who are unable to collect the daily quota spend the night on the streets rather than return to the school. In January 2014, Human Rights Watch encountered a 6-year-old boy sleeping across the street from the Saint Louis bus station. In the cold of winter, the boy was curled up into a ball, with his oversize t-shirt draped over him in a way that made it difficult to determine at first that it was a person. When asked why he was there at 2 a.m., he said that he was short 100 francs CFA ($0.20) and did not want to be beaten.[66] According to local activists in Dakar and Saint Louis, at least scores of boys from Quranic schools overseen by abusive teachers make a similar decision each day.[67]

Tired of suffering physical abuse and sleeping on the streets, many boys decide to run away permanently. If caught and returned, runaways are often subjected to particularly brutal forms of physical abuse, as described by the activist above and a 9-year-old former talibé:

I went in [a room] and they locked me in. Later, the man called for another boy to open the door. After that, the Serigne [a Wolof term for Quranic teacher] chained up my legs…. They chained my arms and legs together … and locked [the door]. [It lasted] for one day… I asked the Serigne to forgive me but he wouldn’t… The Serigne told me that I would not see my father again, that I would die here, be buried here, have a funeral here.[68]

After several weeks of abuse for his attempts to run away, the boy fled again. This time he succeeded and was brought back to his family. Other runaways become semi-permanent street children. A 16-year-old talibé described to Human Rights Watch in January 2014 how several boys from his Quranic school ran away after several days of failing to bring back the daily quota of 500 francs CFA ($1). Living on the streets, the former talibés had taken up stealing to get by.[69] Several civil society activists said that many of the semi-permanent street children in Senegal’s cities are a legacy of the abuses in some Quranic schools.[70]

Some boys who flee exploitation and abuse make their way to shelters for runaways, like Samusocial and Empire des Enfants. The lead social worker at Empire des Enfants, Cheikh Sall, described why many boys run away and what impact the abuse often has:

For most of the kids that we take care of here, they fled because of the abuse they experienced at their Quranic school. Often, the Quranic teacher sends them on the street to beg…. If they’re unable to bring back the money, they’re beaten by the Quranic teacher or [his assistant, often one of the oldest boys]…. When they arrive here, they’re often worn out, worn out because they were traumatized by the Quranic teacher or, if it’s not the Quranic teacher, by people who live on the street.[71]

The failure to apply the law against forced begging allows for the exploitation and abuse to flourish without consequences. A Senegalese civil society activist in a Dakar suburb, who works closely on the talibé issue, described his frustration with the lack of prosecutions:

We’re tired of workshops and discussions. This is a disgrace for the country. It’s a bunch of kids who work for lazy, old men. The abusive ones, the fake Quranic teachers, they complain that they don’t have help, but when they do, they [often] just use it for themselves. We gave a bunch of material to some daaras around here, and when we went back a couple weeks later, the Quranic teachers had taken it all back to their own houses. There are plenty of cases in which the Quranic teachers live in a nice place—an apartment, a house—right next to their daara, where the kids live in intolerable conditions. It’s nothing more than a commercial activity. If you did in France one-tenth of what happens here to the talibés, not only would you go to prison, but they’d close down the establishment. Heck, even the mayor would probably be in trouble for complicity in allowing the place to exist. Why do people think it’s normal that, in order to learn the Quran, children—innocent children—have to be put in this position of servitude?[72]

As described in detail in the 2010 report, the system of forced begging in certain Quranic schools qualifies as a worst form of child labor and, in many cases, as child trafficking and child slavery.[73] It also violates the Senegalese government’s responsibility to ensure children’s rights to health, physical and mental development, protection from economic exploitation, and protection from “all forms of physical or mental violence, injury or abuse, neglect or negligent treatment.”[74] The African Children’s Charter also requires states to take “all appropriate measures to prevent” the trafficking of children and “the use of children in all forms of begging,” as well as “all appropriate measures to eliminate harmful social and cultural practices” that affect children’s well-being and development.[75]

Government Efforts to Enforce the Law against Forced Begging

Other than a prosecution for forced child begging in January 2014, there have been remarkably few such prosecutions since President Sall came to power, including in the year following the fire in the Medina daara. However, there are some signs of potential progress, particularly in the work being led by the justice ministry’s anti-trafficking unit, discussed in Section I in relation to the ongoing mapping of Quranic schools.

The US State Department’s 2013 Trafficking in Persons report, which covers the year 2012, said that while there were some prosecutions in cases of extreme physical abuse, there were no known prosecutions that year under the 2005 law against forced begging:

The Government of Senegal demonstrated negligible anti-trafficking law enforcement efforts during the reporting period…. The government did not maintain or publish statistics relating to human trafficking investigations and did not report any prosecutions or convictions for trafficking during the reporting period. The government prosecuted an unknown number of marabouts[76] for severely beating talibes who they exploited through forced begging; however, these marabouts were only prosecuted for child abuse crimes and were allowed to continue to engage in forced begging.[77]

According to civil society activists and representatives of diplomatic missions who closely monitor the issue, the same dearth of prosecutions for forced child begging held true for the year 2013. Officials in the justice ministry, including in the anti-trafficking unit, said that, up to recently, they have not systematically kept statistics on the number of people who had been arrested, charged, or convicted under the 2005 law—and therefore could not provide Human Rights Watch with specifics.[78]

Several government officials highlighted the prosecution of an imam in January 2014 as demonstrating their will to apply the law against forced begging. According to local media, a talibé with a daily demanded quota of 400 francs CFA ($0.80) told a woman in his Dakar neighborhood that he did not want to go back to his Quranic school because he would be beaten for failing to bring back the full amount. After seeing marks of physical abuse on the boy’s back, the woman reported the case to the police, who arrested the father and son who ran the Quranic school.[79] The father, an imam, was prosecuted and convicted for exploitation through forced begging and for being an accomplice to bodily harm against a child. The prosecution asked for two years of prison; on January 8, the judge sentenced the man to one month, which he had already served.[80] The imam’s son, who allegedly carried out the beatings, is reportedly still to be judged in a juvenile court.[81]

The case could represent a turning point in protecting children from abuse. Unlike with the prosecutions in 2010, during the period of the Wade government, this prosecution does not appear to have occurred as a result of external pressure from international partners. In many ways, the arrest and prosecution seem to be a model for how such cases can and should proceed. A person reported potential child exploitation and abuse to the police, who promptly investigated and arrested the responsible parties. Despite pressure from some religious leaders in the neighborhood, according to civil society activists who closely followed the case, the prosecutor filed charges and pursued them rigorously.

But the case also demonstrates the continued reluctance of some judicial authorities to see the exploitation and abuse of talibés as a serious crime. Although the 2005 law says that the penalty for exploitation through begging is two to five years imprisonment and specifies that the “execution of the sentence will not be stayed when the crime is committed against a minor,”[82] the judge sentenced the imam to one month in prison.

Moreover, the case is so notable—and referenced by nearly every government official interviewed by Human Rights Watch—precisely because it is an outlier. At least hundreds of young boys beg on the streets of many major cities each day, and no one—from the population, the police, or government social services—asks them why they are begging or what consequences they might face if they fail to give their “teacher” the daily money quota. Many boys beg in plain view of police officers or police stations. Dozens of boys who have recently run away from Quranic schools fill the state-run Ginddi Center (Centre Ginddi) and the handful of privately-run shelters in Dakar, Saint Louis, and other major cities. Most of these young boys have stories of being exploited through forced begging, and many of them were subject to extreme physical abuse. Yet, despite the ease of identifying and building judicial cases against men who are exploiting young boys through forced begging, it almost never happens.

The failure to prosecute individuals who violate the law against forced begging contravenes the government’s own strategic plan, adopted in February 2013, to eradicate child begging by 2015. The plan’s first action point calls on the government to “reinforce the protection of children through the application of the provisions in the 2005 law on exploitation through begging.”[83]

There are several positive developments, however. First, the justice ministry’s anti-trafficking unit is currently working on a media campaign against child begging. The proposed announcements, which officials said would start being aired shortly, will speak about the problems of forced child begging and the physical abuse that many boys suffer when they cannot bring back the daily demanded quota. One official in the justice ministry told Human Rights Watch that after rolling out the campaign on TV and radio, the ministry plans to ramp up prosecutions for forced child begging and trafficking.[84] El Hadji Malick Sow, a judge and the president of the anti-trafficking unit, explained his frustration with the lack of application of the law up to present as well as his determination to change that:

The issue I am championing, one of my main priorities here at the [anti-trafficking] unit, is the application of the 2005 law…. We need the ministries of justice, interior, and defense to work together so that the law is applied rigorously. We are pleading for this, we are working towards this.... The president and then-prime minister said after the incident [at the Medina daara] that the law would be applied rigorously, but it hasn’t been, unfortunately. We have some indications as to why the law hasn’t been applied, but it doesn’t justify it. A law was voted, it should be applied…. There is not a complete absence of application. It is starting to be applied, but timidly. We’re working so that it develops further, becomes more common, so that the police have the means to go on the ground and work with children who are victims, identify the so-called teachers who send them on the street…. With time and more determination, we will hopefully make progress in applying the law.[85]

Second, in mid-January the anti-trafficking unit and the interior ministry’s department of criminal affairs formalized a project to systematically collect data related to anti-trafficking efforts—responding to the fact, as one justice ministry official said, that there was “no system in place to measure the number of investigations, prosecutions, and convictions.”[86] Justice ministry officials said that collecting such information would allow for more effective interventions, improve cooperation between officials in the justice and interior ministries, and better inform the public.[87] Given the dearth of prosecutions to date, these statistics will also provide an important benchmark of progress going forward.

Factors that Threaten Progress in Enforcing the Law

Civil society activists and government officials identified four main problems that have impeded arrests and prosecutions of those who profit from forcing children to beg: a lack of high-level political will from the Executive; a lack of courage from low-level government officials, including police and state social workers; a lack of training for police and judicial authorities; and poor communication that has allowed opponents to dominate debate.

Lack of High-Level Political Will

In the aftermath of the Medina fire, President Sall and then-Prime Minister Abdoul Mbaye made strong statements about the need to apply the law against forced begging. The Prime Minister’s office oversaw a working group, which, in close collaboration with civil society leaders, called for the immediate application of the law against those who were exploiting children in their care.[88] Several civil society activists and United Nations officials told Human Rights Watch that a group of Quranic teachers forced a meeting with President Sall and demanded that authorities not proceed with criminal prosecutions (see Text Box after Section I about allies among religious authorities).[89] The government backed off its call to apply the law, focusing instead on moving ahead with the regulation of Quranic schools and support for modern daaras.

Civil society representatives and many mid-level government officials say that political will from the highest levels of the government, notably the president and the interior and justice ministers, is the key variable needed to eradicate exploitation in certain Quranic “schools.” A UN official told Human Rights Watch:

Really the only thing that remains is the political will [to apply the law]. The necessary laws, government bodies, and support mechanisms are in place. After the fire, there was a lot of financing put into shelters and modern daaras that could house children removed from abusive daaras. We thought there would be a big need, but then the government backed off.[90]

A high-level official in the justice ministry agreed:

What is needed is a lot more political courage. For the last 10 years, NGOs have spent a lot of money [on the talibé issue], the government has spent a lot of money. There has been so much awareness-raising, awareness-raising, awareness-raising. The only thing left is the application of the law.[91]

There is a belief among many authorities—reinforced every time a president or prime minister backtracks from strong commitments to prioritize the law’s enforcement—that high-level government officials want to avoid criminal prosecutions even of Quranic “teachers” implicated in the exploitation and abuse of children. This hesitance, combined with a lack of sufficient financial and logistical support, then filters down to state authorities responsible for the law’s implementation. The police fail to do investigations, even when faced with boys begging on the streets; state social workers from the justice and family ministries fail to inform prosecutors of cases even when boys from Quranic schools, including runaways, have stories and markings depicting severe physical abuse; and inspectors from the education ministry fail to report to authorities schools where boys live in abysmal conditions. Although few cases actually reach prosecutors or investigative judges, they may also come under pressure to avoid pursuing too many prosecutions or too harsh of sentences.

President Sall and key ministers could demonstrate their resolve to end exploitation and abuse in certain Quranic schools by issuing instructions to relevant authorities that they should pursue aggressively the law’s enforcement. Another justice ministry official compared the pervasive failure to apply the law against forced begging with the government’s resolve—and success—in removing the glut of street peddlers from downtown Dakar:

It’s not at all difficult. The government could easily say, like it did with the street peddlers, that prefects and governors should prioritize ending this, that the [police and judiciary] should prioritize ending this. The magistrates are ready, they say they’re waiting to be brought cases…. But there is not the political will [at the moment].[92]

Lack of Courage from Lower-level Authorities

Progress in applying the law against forced begging is also sometimes obstructed by police officers and government social workers who refuse to inform the proper authorities even when presented with extreme cases of exploitation and abuse.

A civil society activist told Human Rights Watch a particularly egregious story from mid-2013. A young boy came to him with marks on his back “like nothing I had ever seen.”[93] After speaking with the boy, he learned that the Quranic teacher had used the caustic sap from raw cashew nuts to repeatedly burn the boy on his back for having tried to run away from the daara. The case was brought to the local authorities, including the AEMO (Action éducative en milieu ouvert), a part of the justice ministry that works on child protection, but the Quranic teacher was ultimately not charged.[94]

The activist said that the problem was recurrent:

I do my job, I report cases to the AEMO, but they always resolve them ‘amicably’ with the Quranic teacher, no matter how bad the abuse. Cases of physical abuse and even torture, cases in which a talibé has had skin infections that worsen for months without the Quranic teacher taking action [to get care], cases in which a talibé dies from malaria after a Quranic teacher hides him away instead of seeking out free treatment—I have reported many of them, but they never go anywhere.[95]

Untrained Judges, Police, and Prosecutors

Several officials in the justice ministry said progress was blocked by a general lack of understanding from police and judicial authorities about the law against forced begging.[96] In particular, one official said that some prosecutors and judges remain confused about the interplay between the 2005 law and Article 245 of Senegal’s Penal Code. That article forbids begging, but states that “soliciting alms on days, in locations, and under conditions associated with religious traditions does not constitute begging.”[97]

A high-level official in the justice ministry said that there was a need “to better explain” to police, prosecutors, and judges “that the 2005 law can and should be applied, that it is not blocked in any way by the previous law.”[98] Whereas Penal Code Article 245 focuses primarily on criminalizing the act of begging itself, the 2005 law takes a far better approach in criminalizing those who profit off of forcing another person to beg.