Summary

Jahaj, 17, has worked in a factory where animal hides are tanned in Hazaribagh, a combined residential and industrial neighborhood of Dhaka, since he was 12. He works a 10-hour day (with an hour off for lunch) and earns 3,000 taka (US$37) a month. Around 50 other people work in the tannery, including a seven and an eight-year-old, who are employed nailing hides out to dry.

Jahaj told Human Rights Watch that he mostly processes raw hides into the first stage of leather, known as “wet blue,” which exposes him to hazardous chemicals. The tannery pits are four-meter square tanks that hold hides and many of the diluted chemicals used to cure them. Jahaj particularly dislikes working there.

We get inside, take the hides with our hands and throw them outside the pit. We wear gloves and boots but water splashes on our skin and clothes. We don’t wear an apron. The water in the pits has acid, which burns when it touches my skin.

He suffers from rashes and itches; his father and two brothers, also tannery workers, have similar skin diseases. Asked why he performed such hazardous tasks, he said: “When I’m hungry, acid doesn’t matter—I have to eat.”

Jahaj has had various accidents at work: he once stepped on a nail used to pin leather out to dry, has hurt his back lifting heavy hides, and was once trapped inside a large rotating wooden drum used to hold the skins.

I started shouting, ‘Who has turned on the drum?’ After a couple of minutes they turned it off but I was already injured with lots of cuts and bruises on my head, my back, my arms. There are long wooden planks inside the drum that make the skins soft and they hit my body repeatedly.

A major Dhaka hospital diagnosed Jahaj with asthma. “The fumes from the chemicals where I work are really strong,” he said. When Jahaj cannot work because he is ill or injured, he is not paid—also a violation of Bangladesh’s labor laws. Nor, he said, has he seen a government labor inspector during his five years at the tannery.

Human Rights Watch estimates there are some 150 tanneries in Hazaribagh, ranging in size from small operations with just a dozen or so workers to larger ones that employ a few hundred workers. Together, the tanneries employ around 8,000 to 12,000 people (swelling to around 15,00o during the peak processing season for two or three months following the annual festival of Eid-al-Adha).

Hazaribagh is home to between 90 and 95 percent of all tanneries in Bangladesh and, as a result, holds an important place in Bangladesh’s increasingly lucrative leather industry. From June 2011 to July 2012, Bangladesh’s tanneries exported close to $663 million in leather and leather goods—such as shoes, handbags, suitcases, and belts—to some 70 countries worldwide, including China, South Korea, Japan, Italy, Germany, Spain, and the United States. Over the past decade, leather exports have grown by an average of $41 million each year.

This report is based on research conducted in Bangladesh between January and May 2012, and interviews with 134 people, including past and current tannery workers, slum residents, healthcare professionals, workers with nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), trade union and government officials, leather technologists, and chemical suppliers.

This report supports previous reports, studies, surveys, and even government findings dating to the 1990s that have documented a range of human rights abuses and problematic conditions in and around Hazaribagh tanneries. These include unregulated industrial pollution of air, water and soil, illness among local residents, perilous working conditions, and labor of girls and boys (often in hazardous conditions and for menial pay).

This report also finds that public knowledge and records concerning these problems have not led to changes on the ground. The reason is that Hazaribagh tanneries operate in an enforcement-free zone in which they are subject to little or no government oversight with regard to environmental regulations or labor laws, as government officials readily admit. Quazi Sarwar Imtiaz Hashmi, a Department of Environment official put it simply: “There is no monitoring and no enforcement in Hazaribagh.”

As a result of this inaction—which is due to a de facto policy not to implement environmental laws in Hazaribagh, and a labor inspectorate that lacks manpower and prioritizes good relations with management—workers and local residents (many of whom are poor and live in slums) continue to reside and labor in a noxious, foul-smelling environment that damages their health.

Health Problems

Past and present tannery workers described and displayed a range of health conditions including prematurely aged, discolored, itchy, peeling, acid-burned, and rash-covered skin; fingers corroded to stumps; aches, dizziness, and nausea; and disfigured or amputated limbs. Although Human Rights Watch is not aware of any epidemiological studies on cancer among tannery workers in Bangladesh, some anecdotal evidence suggests that cancer rates are indeed elevated among workers dealing with chemicals.

Many common health problems that tannery workers face—such as skin and respiratory diseases—result from repeated exposure to a hazardous cocktail of chemicals when measuring and mixing them, adding them to hides in drums, or manipulating hides saturated in them. Some chemicals can be injurious to health in the short term, such as sulfuric acid and sodium sulfide that can burn tissue, eye membrane, skin, and the respiratory tract. Others, such as formaldehyde, azocolorants, and pentachlorophenol, are confirmed or potential human carcinogens, the health effects of which may only manifest years after exposure.

Workers expressed extreme concern to Human Rights Watch regarding the possible long-term effects of such exposure. Many complained that their tannery did not supply protective equipment such as gloves, masks, boots, and aprons, or if it did, failed to supply sufficient quantities. Other workers told Human Rights Watch they suffered serious accidents working old and poorly maintained tannery machines for which they had scant training. Shongi, in his mid-40s, described an accident with a large hot plate used to press hides, which had occurred nine days before his interview with Human Rights Watch.

I put the hide into the machine but it was a little crumpled and I put my hand inside to fix it. Without pushing the pedal, the plate fell on my hand. It was a malfunction of the machine…. I screamed. The flesh started to come off my hand.

No tannery worker interviewed had a written employment contract. Some tannery managers deny workers legal entitlements such as paid sick leave or compensation when workers become ill or injured.

In Hazaribagh’s tanneries, raw hides often undergo the first stage of tanning in large wooden drums and pits on the ground floor. Larger, multi-story tanneries will then take hides known as “wet blue” upstairs for drying and further processing with heavy machinery; smaller tanneries might transfer the “wet blue” hides to another tannery that will then complete the procedure. Many tanneries are hot and cramped, with loud noise from machines and poor ventilation of chemical fumes.

Human Rights Watch did not seek to interview all tannery owners in Hazaribagh due to time concerns. Government officials, tannery association representatives, trade union officials, and staff of NGOs all said that no Hazaribagh tannery has an effluent treatment plant to treat its waste.

As a result, huge amounts of chemicals flow off the tannery floor, into open gutters in Hazaribagh streets, and then into a stream leading to the Buriganga, one of Dhaka’s main rivers. The government estimates that tanneries release 21,600 cubic meters of untreated effluent each day in Hazaribagh, endangering the health of local residents. Pollutant levels in the wastewater surpass Bangladesh’s permitted limits for tannery effluent, in some cases by many thousands of times the permitted concentrations.

People living in the densely-packed streets and alleys surrounding the tanneries, from which dark effluent spouts and swirls in open gutters, reported an array of health problems—many of them undiagnosed due to the cost of medical attention. These included fevers, diarrhea, respiratory problems, and skin, stomach, and eye conditions. While other factors may play some part in these illnesses, the extent of documented tannery pollution, the results of interviews with residents, and the findings of studies showing a higher prevalence of these illnesses in Hazaribagh compared to neighborhoods with similar socio-economic characteristics, strongly suggest a causal relationship between tannery pollution and poor community health.

Residents also said they were worried that they did not know the extent of environmental contamination since government authorities do not monitor the pollution. Ashor, married with four children, said:

I am worried about the supply water…. The corrugated tin [used in house construction] corrodes in six months. This also worries me. I want to know more but I’ve never been given any information about the water, air, and soil.

Failure to Implement Laws

Department of Environment officials explained there is a de facto policy not to implement environmental laws in Hazaribagh because the government is preparing a site in Savar, some 20 kilometers to Hazaribagh’s west, in which to relocate the tanneries. Officials confirmed that, on the basis of this understanding, they do not regularly monitor water, air, or soil in Hazaribagh, nor do they levy fines or other sanctions against its tannery owners for untreated effluent discharges.

The government’s plan to prepare a relocation site in Savar has suffered chronic delays. Its most recent deadline (at this writing) is for tanneries to move there by the end of 2013. But given the long history of bureaucratic delays, some people familiar with the leather industry believe that relocation is unlikely before 2015, while others suggested it might only happen in 2017. When Human Rights Watch visited Savar in May 2012, no tannery had begun building new facilities at the site.

The country’s two main tannery associations agreed with the government in 2003 that some 150 member-tanneries in Hazaribagh would relocate, and the Bangladeshi government agreed to compensate these tanneries for some of the costs of relocation. However, officials in both tannery associations told Human Rights Watch they were negotiating compensation from the government considerably in excess of the amount previously agreed.

In June 2012, the chairman of the Bangladesh Finished Leather, Leather Goods and Footwear Exporters Association told Human Rights Watch that while the group was “hopeful” that the government will meet its demands, failure to do so would mean “it won’t be possible to shift and this [situation] will be the government’s liability.”

Lack of Oversight

While the Department of Environment operates on an understanding not to implement environmental laws in Hazaribagh, officials in the Ministry of Labour’s Inspection Department admitted that “the Hazaribagh tanneries are barely touched [by us].” They explained that with just 18 inspectors to monitor an estimated 100,000 factories in Dhaka, the department lacks resources to ensure that Hazaribagh tannery employers comply with the law.

Human Rights Watch was told that factory inspectors do visit some tanneries, but that no tannery has been prosecuted in labor courts. Another official explained that inspectors prioritize good relations with managers and give them advance notice before an inspection.

According to a Bangladeshi High Court ruling in 2001, the government should have ensured that the Hazaribagh tanneries installed adequate means to treat their waste over a decade ago. The government ignored that ruling. The High Court then ruled in 2009 that the government should ensure that the Hazaribagh tanneries relocate outside of Dhaka or close them down. The government and the tannery associations sought (and were granted) a number of extensions to that order, and then ignored the order when those extensions lapsed.

The lawyer who represented the tannery associations in one petition to the High Court in February 2010 for an extension was Sheikh Fazle Noor Taposh, who is a member of the government and the lawmaker representing Hazaribagh. He is also Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s nephew.

Obligations

International human rights law compels Bangladesh’s government to protect its citizens from abuses, including those connected with business activity. Many of Hazaribagh’s tanneries’ have serious health implications for their workers, including children like Jahaj, and local residents.

The International Covenant on Economic Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) requires that states realize the right to the highest attainable standard of health for everyone in their territory. The Committee on Economic Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), tasked with interpreting the ICESCR, has affirmed states’ obligations to protect the health of its workers.

The CESR has also explained that governments violate the right to the highest attainable standard of health if they fail to regulate the activities of corporations to prevent them from violating the right to health of others. This includes “the failure to enact or enforce laws to prevent the pollution of water, air and soil by extractive and manufacturing industries.” The right to health encompasses the right to healthy natural environments. This right involves the obligation to “prevent threats to health from unsafe and toxic water conditions.”

The government has also failed to implement relevant national laws that could protect its citizens from abuses. As a result, it is not fulfilling its duties to protect the right to health of its citizens as recognized under domestic and international law. Compounding this situation, the government’s failure to respect High Court rulings has deprived residents suffering health problems due to Hazaribagh’s tanneries of an effective judicial remedy.

There is a widespread assumption in government circles that building a planned central effluent treatment plant (CETP) in Savar will resolve the environmental and health issues related to the Hazaribagh tanneries. Human Rights Watch recognizes that a CETP will allow tanneries in Savar to treat their waste. However, there are already well-documented alternative processes and technologies proven to significantly reduce tannery pollution— and which do not require a CETP. Without enforcement of environmental laws by the Bangladeshi government, there is no incentive for the Hazaribagh tanneries to reduce their pollution load by adopting such measures.

A CETP will do nothing to resolve most of the problems identified in this report, such as poor occupational health and safety conditions, hazardous child labor, and the existing industrial pollution of Hazaribagh. Even if the CEPT is built, there is a risk that tanneries might simply refuse to use it in the absence of proper monitoring and enforcement. Simply put, the issues identified in this report cannot be solved by a technical fix.

Regardless of the status of CETP construction, the Bangladeshi government should closely monitor and regulate the Hazaribagh tanneries and rigorously enforce the country’s labor and environmental laws. This will be an important step towards resolving many problems identified in this report, such as poor occupational health and safety conditions, denial of paid sick leave and compensation when injured, and hazardous child labor.

Since each of Hazaribagh’s 150 or so tanneries may have contracts with numerous buyers that vary by facility and over time, the report does not focus on working conditions in specific tanneries, nor on particular international companies that may purchase leather from Hazaribagh tanneries. Human Rights Watch believes that sustained enforcement of Bangladeshi law throughout the Hazaribagh tanneries offers the best hope for remedying the systemic human rights violations identified in this report.

Foreign companies that source leather produced in Hazaribagh have a crucial role to play in ensuring that Hazaribagh residents are no longer exposed to hazardous chemicals and other forms of pollution, and that tannery workers enjoy safe and healthy workplaces. They should immediately take steps to ensure that they are not implicated in unregulated pollution, violations of occupational health and safety laws, or hazardous child labor through their supplier relationships (including through “job work” tanneries sub-contracted to perform part or all of leather processing).

Critics of regulation contend that Bangladesh is a poor country, which can ill-afford to enforce laws that could possibly shut down the tannery industry. However, ensuring compliance of all Hazaribagh tanneries with international standards and Bangladeshi law is an opportunity to establish the industry as a modern sector capable of producing high-value and high-quality leather in an environmentally sound and rights-respecting manner that strengthens, rather than undermines, this growing sector of the nation’s economy.

Recommendations

To the Government of Bangladesh

- Order all Hazaribagh tanneries to immediately begin relocating outside Dhaka city.

- In accordance with Bangladesh’s Environmental Conservation Act (1995) and Environment Conservation Rules (1997), ensure that all tanneries (including relocated ones) have an environmental clearance certificate for industrial units categorized as “red” (i.e. heavily polluting) from the Department of Environment, or close them down.

- Immediately fill all vacancies for inspectors and assistant inspectors in the Ministry of Labour’s Inspection Department. Within two years, significantly increase the number of staff positions and resources (including for salaries) available to the department to enable it to conduct more regular in-field assessments, including unannounced inspections.

- Revise the Labour Act to strengthen

penalties for the following offences:

- Causing death, grievous bodily harm, or any “injury or danger to workers”,

- Employing a child or adolescent in hazardous labor,

- The “catch-all” offence of violating the terms of the act.

- Ratify the International Labour Organization’s Convention 138 On The Minimum Age For Admission To Employment And Work.

To the Ministry of Environment and Forests

- Regardless of the status of the relocation plan, implement the provisions of Bangladesh’s Environmental Conservation Act (1995) and Environment Conservation Rules (1997) that allow for monitoring of all tanneries in Hazaribagh for pollution levels that surpass national standards. Prioritize tanneries that discharge a comparatively large amount of effluent, or discharge effluent with high concentrations of comparatively hazardous chemicals.

- Regardless of the status of the relocation plan, implement the provisions of Bangladesh’s Environmental Conservation Act (1995) and Environment Conservation Rules (1997) that allow for fines on all tanneries in Hazaribagh found to have pollution levels that surpass national standards.

- In accordance with Bangladesh’s Environmental Conservation Act (1995) and Environment Conservation Rules (1997), ensure all tanneries in Bangladesh have an environmental clearance certificate for industrial units categorized as “red” (i.e. heavily polluting). Close tanneries operating without an environmental clearance certificate, if necessary seeking the cooperation of law enforcement agencies and/or utility service providers.

- Design a comprehensive environmental strategy for the Savar relocation site to prevent replicating the environmental damage and hazards to health present in Hazaribagh.

- Devise a comprehensive environmental clean-up strategy for Hazaribagh, prioritizing surface ponds, large dumps of tannery waste, and the main drainage canals. Remove topsoil polluted beyond the risk-based threshold values and replace it with clean soil.

- Actively monitor for Hazaribagh groundwater contamination on an ongoing basis.

- Ensure that residents of Hazaribagh are informed about the extent of environmental contamination in Hazaribagh and possible health consequences of contamination.

- Increase children’s knowledge of environmental health issues by introducing environmental health programs in schools in Hazaribagh.

To the Ministry of Labour and Employment

- Take immediate and sustained action to

enforce compliance by all tanneries in Hazaribagh (and, following relocation,

in Savar) with the Labour Act (2006), including the provisions on:

- Worker health and safety,

- All paid leave including sick leave,

- Compensation for injuries (including occupational diseases),

- Effective disposal of waste and effluent.

- Revise the practice whereby labor inspectors set up advance appointments with factory management. Train and instruct labor inspectors to undertake unannounced inspections.

- Immediately implement an effective removal program for child laborers in tanneries that provides: access to education, including non-formal education and skills development training; alternative income generation opportunities where appropriate; and socio-economic empowerment programs for their families. Prioritize those children performing hazardous labor, including work with chemicals, tannery machinery, and blades for cutting leather. Ensure that the program includes children not reached by previous programs, such as those working full-time, those working with employers who did not want to cooperate with the projects, and those living in tanneries.

- Rigorously enforce existing laws prohibiting hazardous child labor in tanneries, including through proactive monitoring and unannounced on-site inspections, and by imposing effective penalties against employers who violate the law.

- Provide labor inspectors with all the necessary support, including child labor expertise, to enable them to effectively monitor the implementation of labor law standards regarding children in Hazaribagh tanneries.

- Require employers to have, and produce on demand, proof of age of all children working on their premises.

To the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare

- Devise a comprehensive public health strategy to tackle the health problems of residents in Hazaribagh (and, following relocation, to prevent such health problems for residents in Savar).

- Ensure the cancer registry maintained by National Institute of Cancer Research and Hospital collects and makes available data disaggregated by profession and current address at the level of thana/upazila (i.e. sub-district).

To Foreign Companies Sourcing Leather or Leather Goods from Hazaribagh

- Ensure that all leather and/or leather goods

originate from tanneries in compliance with international standards and

Bangladeshi environmental and labor law, through the following mechanisms:

- A social and environmental review of source tanneries (including tanneries that process all or part of the leather from supplier tanneries on a “job work” basis) performed by a credible third party,

- Site visits of source tanneries (including tanneries that process all or part of the leather from supplier tanneries on a “job work” basis).

- Cease all commercial relationships with tanneries that do not operate in compliance with international standards and Bangladeshi environmental and labor law.

To Bangladesh’s Bilateral and Multilateral Donors

- Support a comprehensive environmental clean-up strategy for Hazaribagh, prioritizing surface ponds, large dumps of tannery waste, and the main drainage canals, and the removal and replacement of polluted topsoil.

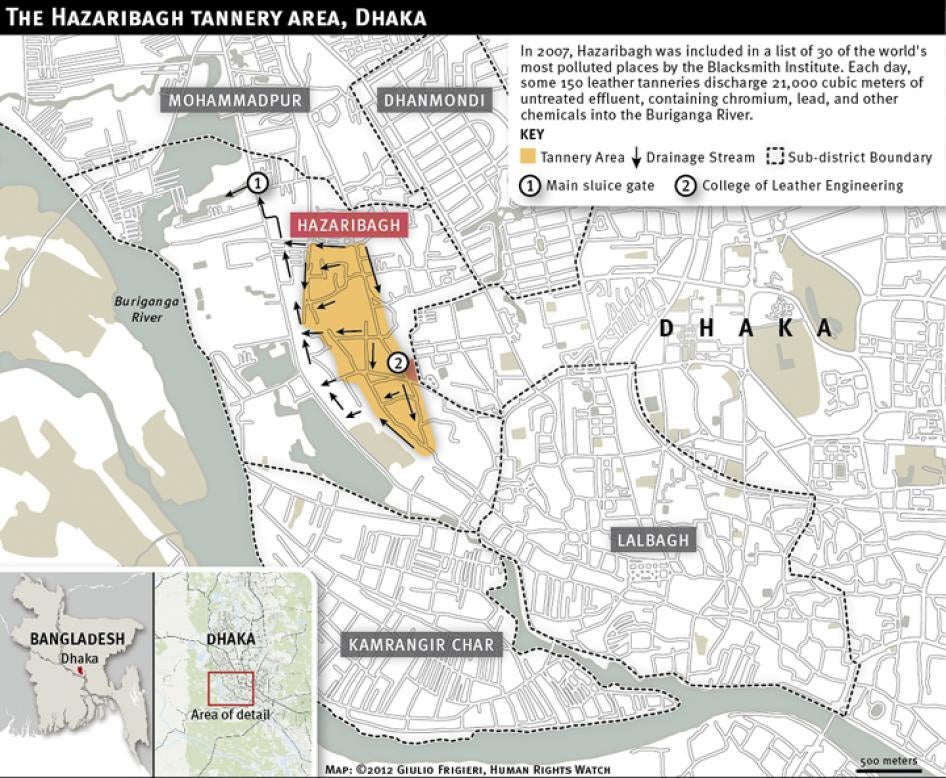

Map of Hazaribagh

Methodology

This report is based on information collected during eight weeks of field research conducted in Bangladesh between January and May 2012. In the course of this research, Human Rights Watch visited eight tanneries.

A senior researcher with Human Rights Watch interviewed 134 people for this report, including 53 people who currently work, or previously had worked, in Hazaribagh tanneries. Of these, 49 were workers currently employed in tanneries and four were former tannery workers. Human Rights Watch also spoke to six people who were currently working in Hazaribagh factories processing tannery waste products (although not involved in directly processing leather). While their evidence was similar to those working in tanneries, it has not been included in this report, which is focused on Hazaribagh’s leather tanneries.

Of the 53 worker interviewees, 9 were adult women and 10 were children (i.e. under the age of 18)—5 of whom were boys and 5 of whom were girls.

Human Rights Watch also spoke to 20 residents of slums in Hazaribagh (5 residents from each of 4 different locations). Of the 20 residents interviewed in the course of this research, 13 were women.

All residents and workers interviewed provided verbal informed consent to participate and were assured that they could end the interview at any time or decline to answer any questions. Interviewees who are residents or workers have been given pseudonyms and in some cases other identifying information has been withheld to protect confidentiality.

Human Rights Watch also spoke to an additional 42 people familiar with the tannery industry in Bangladesh, including healthcare professionals, staff of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), staff of international organizations, trade union officials, academic researchers, journalists, representatives of tannery associations, leather technologists, and chemical suppliers.

Secondary sources—including academic research, project reports, and media coverage—were reviewed and included to corroborate information from residents or tannery workers. This report includes a number of secondary sources from the 1990s: these were deliberately chosen to show the length of time for which these issues have been publicly discussed. More recent research supports the findings of this earlier research and is also included in this report. Bangladeshi laws and policies were also reviewed.

Human Rights Watch spoke to 13 government officials (4 from the Department of Environment, 4 from the Ministry of Labour and Employment, 2 from the Ministry of Industries, 2 from the government’s National Institute for Cancer Research and Hospital, and the member of parliament for Hazaribagh).

Human Rights Watch did not seek to interview all tannery owners in Hazaribagh due to time concerns. In June 2012, Human Rights Watch requested meetings with the managing directors of two Hazaribagh tanneries. Senior staff at both tanneries replied that a meeting was not possible because the relevant directors were busy and/or travelling.

In July 2012, Human Rights Watch wrote to the minister of environment and forests, the minister of industries, and the minister of labour and employment to request information on the tanneries in Hazaribagh and to solicit response to the issues documented in this report. This correspondence is attached at Annex 1. No reply had been received as this report went to publication.

I. Background

Hazaribagh’s Tanneries

The neighborhood of Hazaribagh lies to the west of Dhaka’s city center, absorbed into the city as Dhaka has expanded. It is surrounded by residential neighborhoods, except to the west where it is bordered by an embankment built in the late 1980s to protect the area from flooding. Beyond the western embankment is a flood plain of the Buriganga, one of Dhaka’s main rivers that lies just one kilometer away.

Like much of Dhaka, Hazaribagh is dense with medium-rise apartment buildings, as well as shops, schools, and mosques. Small businesses like fruit sellers, hairdressers, and tea stalls line the streets. On either side of the western embankment—but mostly on the floodplain—are slums of single-room houses made from concrete, wood, and tin sheets.

Tanneries, some on main streets and others tucked down side alleys, are packed into 50 acres of Hazaribagh. They are often brick-walled factories, with small windows of grills or broken glass. Running beside the factories are open gutters full of opaque blue-grey water, bubbling and swirling. Drains spouting from tannery walls add brown, red or black effluent to the mix. Scraps of discarded leather—thin ribbons or sharp triangles—are everywhere in the streets. There is a strong smell in the air, like rotten eggs.

In between the tanneries are shop fronts stocked with white sacks and plastic blue drums filled with tanning chemicals. Pushcarts with drums lashed to them are constantly on the move through the narrow streets and lanes, as are men pushing bamboo carts piled high with folded leather. Other workers ferry between tanneries balancing a bamboo pole over one shoulder, two square metal tins full of tannery wastewater bouncing on each end: they are recycling wastewater from one tannery for use in another.

Many tanneries in Hazaribagh are multi-story buildings. Raw hides are often processed into “wet blue” leather in large wooden drums and pits on the ground floor, before they are taken upstairs for drying and further processing with heavy machinery.[1] Conditions in these factories are often hot and cramped, with loud noise from machines and poor ventilation of chemical fumes.

How Tanneries Operate

There is considerable variety in how tanneries in Hazaribagh operate. Some tanneries will perform all stages of leather processing, converting raw hides to “wet blue” leather, then to “crust leather,” and finally finished leather. All these stages might be performed under the same roof, or the tannery might have a number of different factory units specialized in each stage scattered throughout Hazaribagh.

In other cases, a single hide will pass through two or three different tanneries before the tanning process is complete. Some tanneries only process raw hides to the “wet blue” stage, or to the “crust leather” stage, before selling on these hides to other tanneries which then complete the process.

Other tanneries rent their factory to leather businessmen who process a batch of hides using that tannery’s premises and heavy machinery, but supplying their own workers, hides and chemicals. The leather businessmen pay the tannery a pre-determined fee based on the number of hides and the stages of processing performed. This way of working, known as “job work,” is common in Hazaribagh. A “job work” tannery might have a dozen or so leather businessmen whose workers all process batches of hides under the same roof at any one time. Those leather businessmen will describe themselves as an independent tannery, even though they rent out the production facilities from another tannery (that may or may not have its own production).

Regular tanneries might process some hides in “job work” tanneries, for instance during peak production periods, or in order to fulfill a large order.

Because of such variety in how tanneries operate, the number of tanneries in Hazaribagh is sometimes given as low as 50 or as high as 350, depending in large part on what is counted as a tannery. Human Rights Watch estimates there are about 150 tanneries in Hazaribagh, considering a tannery as an independent factory unit.[2] A relatively large tannery will employ a few hundred workers, while a medium-sized tannery will employ around a hundred workers, and small tanneries might have just a dozen or so workers.

There are some 8,000 to 12,000 tannery workers, rising to about 15,000 for two or three months following the festival of Eid-al-Adha, the peak season for raw hide processing.[3]

The Hazaribagh tanneries make up between 90 and 95 percent of all tanneries in Bangladesh.[4] There are a handful of tanneries in Bangladesh outside Hazaribagh, located in other areas of Dhaka, as well as Jessore and Chittagong. This report does not address those tanneries.

Around 80 percent of Bangladesh’s total leather production is for export.[5]

Leather (as crust or finished leather), leather footwear, and leather goods (such as suitcases, handbags, and belts) are major export earners for Bangladesh. According to official trade statistics, from June 2011 to July 2012 Bangladesh exported around $663 million worth of leather and leather goods (including leather footwear). This leather was exported to some 70 countries throughout in the world, but principally China, South Korea, Japan, Italy, Germany, Spain, and the United States.[6] In the ten years since 2001-2002, the value of leather exports has grown by an average of $41 million per year.[7]

Bangladesh’s exporters of leather and leather goods enjoy economic incentives from the government, including cash subsidies as a percentage of the value of exports. For example, in 2010-2011, the government reportedly disbursed $22 million to exporters of leather goods.[8] In mid-2012, the government raised the rate of cash subsidy for the export of leather goods to 15 percent (up from 12.50 percent for 2011-2012).[9]

Water, Soil, and Air Pollution

The effluent that pours off tannery floors and into Hazaribagh’s open gutters contains animal flesh, dissolved hair, and fats. It is thick with lime, hydrogen sulfide, chromium sulfate, sulfuric acid, formic acid, bleach, dyes, oils, and numerous heavy metals used in the processing of hides.[10] This effluent flows from the open gutters into a stream that runs through some of Hazaribagh’s slums, and into Dhaka’s main river, the Buriganga.

The tanneries generate a lot of solid and liquid waste.[11] Each day, the tanneries in Hazaribagh create an estimated 75 metric tons of solid waste (mostly salts, bones, as well as leather shavings and trimmings), an amount which may rise to 200 metric tons of solid waste per day in peak production periods.[12] In terms of liquid waste, the government and the two main tannery associations stated in 2003:

About 21,600 cubic meters of environmentally hazardous liquid waste is emitted every day from the tanneries located in Hazaribagh which include hazardous chemicals such as chromium, sulphur, ammonium, salt and other chemicals.….[13] The lives of the people of Hazaribagh are greatly endangered through the damage of the environmental balance in this way, and it is taking a very frightening turn.[14]

Concentrations of chemicals and other contaminants in tannery effluent depend on the location of the wastewater sample, as well as the type of tanning process employed in the tannery, and whether monsoon rains have diluted the wastewater.

Regardless of such variables, previous studies by academic researchers, international projects, and even government investigations have found that the pollution content in Hazaribagh’s wastewater surpasses the limits for tannery effluent established in Bangladesh’s environmental regulations, in some cases by many thousands of times the permitted concentrations.[15]

One detailed study published in 1999 analyzed wastewater samples taken directly from 47 tanneries. The results showed extremely elevated levels of chromium, chloride, lead, sulfates, sulfides, nitrates, and zinc in the effluent. For example, wastewater from one particular tannery had a biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) reading of 3,600 mg/L (against Bangladesh’s quality standard for tannery effluent of 100 mg/L) and a chemical oxygen demand (COD) reading of 9,300 mg/L (against a standard of 200 mg/L). High BOD and COD readings mean there is less oxygen in the water, which causes aquatic life to suffocate and die.[16] This tannery’s wastewater contained concentrations vastly in excess of permitted standards: chromium (4,043 mg/L, against a standard of 2 mg/L), chloride (45,000 mg/L, against a standard of 600 mg/L), lead (1.944 mg/L, against a standard of 0.1 mg/L), and sulfide (145 mg/L, against a standard of 1 mg/L).[17]

Other studies have sampled the water in gutters and streams around Hazaribagh. They also found that the wastewater is thick with chemicals common to the tanning process, far in excess of permitted levels.[18]

One of the rare government studies to measure water quality in Hazaribagh was a 2008 Department of Environment survey on industrial pollution. BOD and COD concentrations found in the Hazaribagh samples were notably higher than those from seven other industrial zones near Dhaka, and revealed that Hazaribagh wastewater vastly exceeds Bangladesh’s permitted standards for tannery effluent.

Tannery effluent also threatens the groundwater under Hazaribagh, although there is no research showing negative effects on human health from this potential route of exposure. However, the issue is particularly significant given that an estimated 95 percent of Dhaka city’s water supply (used for bathing, cooking, and cleaning by an estimated 14 to 15 million people) is derived from various groundwater supplies.[19]

Table: The Department of Environment’s Chemical Analysis of Wastewater[20]

|

Parameter |

Unit |

Bangladeshi Standard for Tannery Industry Effluent [21] |

Hazaribagh Sample 1 |

Hazaribagh Sample 2 |

|

pH [22] |

|

6-9 |

5.017 |

4.987 |

|

Biochemical Oxygen Demand [23] |

mg/L |

100 |

846.7 |

730.0 |

|

Total Suspended Solids [24] |

mg/L |

150 |

17,467 |

15,068 |

|

Total Dissolved Solids [25] |

mg/L |

2,100 |

4,490 |

2,867 |

|

Chromium |

mg/L |

2 |

3,324 |

2,558 |

Most studies of Hazaribagh’s groundwater have focused on the presence of elevated levels of chromium.[26] One widely-cited 2001 study showed an average chromium concentration in Hazaribagh groundwater of 0.036 mg/L, about 10 times higher than the average chromium concentration of water samples from other areas in Dhaka. Samples from two deep tube wells in Hazaribagh surpassed the limit for chromium in drinking water permitted by Bangladeshi environmental regulations (i.e. 0.05 mg/L). The study concluded:

In the absence of any natural source for chromium and the presence of a large number of tanneries in the Hazaribagh area, it appears that chromium from tannery wastewater is contaminating the groundwater in and around Hazaribagh area.[27]

Although the vast majority of chromium detected in the 2001 study on Hazaribagh groundwater was in trivalent form, trace amounts of chromium were detected in hexavalent form.[28] Hexavalent chromium is much more toxic than trivalent chromium: inhaled hexavalent chromium increases risk of lung cancer, while touching certain forms of hexavalent chromium can cause dermatitis and skin ulcers.[29] There is recent data from China associating higher levels of hexavalent chromium in well water with significantly higher rates of death from stomach cancer in humans.[30]

A study in 2006 reported lower concentrations of chromium in Hazaribagh groundwater than the 2001 study.[31] However, it did find that groundwater samples from Hazaribagh were higher in sodium, magnesium, ammonium, chlorine, sulfate, and calcium as well as chromium, copper, lead, aluminum, and sulfur than adjacent areas. It warned that “there is the possibility of contamination of the deeper groundwater in the future if protection of the soil and groundwater environment from untreated tannery wastes is not considered.”[32]

Foul-smelling and noxious gases pollute the air in Hazaribagh. Gas analysis of air samples taken in 2007 found levels of nitric oxide above the permitted Bangladeshi limit for ambient air quality. The study also found alarmingly high levels of benzene gas and hydrogen sulfide, a colorless, poisonous, and flammable gas commonly described as smelling like rotten eggs.[33] A 2000 study of air quality at a Hazaribagh tannery found the air surpassed the standard for suspended particulate matter (such as dust and fumes).[34]

Studies have also shown that tannery waste contaminates Hazaribagh’s topsoil. A 1999 study found contamination by various metals, including lead and cadmium. It concluded:

As a whole, the tannery area soils had the highest concentration of… cadmium, manganese, nickel, lead and zinc which might be due to discharging liquid wastes, flocculated sludge and other solids with excessive heavy metals coming from different tanning processes. The highest level of lead … may constitute direct health hazards too.[35]

Along with many other contaminants, the topsoil in Hazaribagh is heavily polluted with chromium, with some studies measuring the concentration in a range from 15,000 to 33,500 mg/kg dm.[36] Although the vast majority of chromium in the soil in Hazaribagh is trivalent, a small amount of the total chromium in the topsoil is in hexavalent form.[37]

Long-Term ProblemsIn addition to unregulated industrial pollution, studies from as early as the 1990s identified other issues covered by this report. They include: Illnesses among ResidentsA 1997 study compared the self-reported health problems in 112 households in Hazaribagh with those from 100 households in a nearby Dhaka neighborhood (with similar socio-economic characteristics but located further from the tanneries). Respondents in Hazaribagh reported 31 percent more cases of skin diseases, 21 percent more cases of jaundice, 17 percent more cases of kidney-related disease, 15 percent more cases of diarrhea, and 10 percent more cases of fever than the residents in the other neighborhood. [38] A Worker Health and Safety CrisisA study on the health of tannery workers undertaken in 1999 found high morbidity among tannery workers. The report found that 58 percent of the tannery workers suffer from gastrointestinal disease (versus 24 percent for the country as a whole), 31 percent from skin diseases (versus 9 percent), 12 percent from hypertension (versus 0.9 percent), and 19 percent from jaundice (versus 0.07 percent). Thirty-seven percent of workers reported experiencing workplace accidents . [39] Hazardous Child LaborA UNICEF-commissioned survey of child labor published in 1997 documented the hazardous work performed by children in the Hazaribagh tanneries. The report found that “Under-aged children are not supposed to work with dangerous machinery, yet… fairly young individuals do.” The report recommended that tanneries reduce or eliminate child labor . [40] |

A study in 2008 funded by the European Union found the top three meters of soil in Hazaribagh severely contaminated. It noted:

Through percolation of the wastewater, the soil of Hazaribagh has been contaminated with chromium (up to 37000 mg/kg dm), mineral oil, phenols and extractable organohalogen compounds (up to 1200 mg/kg dm). Sulfur concentrations are high as well.[41]

The study found that exposure to chromium via skin contact with the soil and water (while bathing) represented unacceptably high risks to the health of adults and children living in Hazaribagh. It recommended the immediate elimination of direct waste discharges, the removal of surface ponds, large dumps of tannery waste, and the main drainage canals, as well as remedial action to remove and cover the contaminated soil.[42] As of this writing, no such remediation had taken place.

II. Findings

Hazaribagh: Beyond Reach of the Law

We are not doing anything for Hazaribagh. The tannery owners are very rich and politically powerful.

—Mahmood Hasan Khan, director of air quality management, Department of Environment, Dhaka, June 7, 2012[43]

Government officials responsible for ensuring employers protect worker health and safety, as well as environmental monitoring and enforcement, admitted to Human Rights Watch that they do not uphold Bangladesh’s laws with respect to the tanneries in Hazaribagh.[44]

Since 2001, the government has ignored repeated rulings from the High Court Division of the Bangladeshi Supreme Court ordering the government to ensure that the Hazaribagh tanneries install means to treat their effluent and relocate out of Dhaka. The government sought extensions of the High Court order to relocate, and then ignored the order when the extension has passed. The government’s failure to follow the High Court’s orders has left the residents of Hazaribagh without any legal remedy for the skin diseases, fever, diarrhea, stomach problems, and respiratory illnesses caused by tannery pollution.

The government’s plan to prepare an alternative site for the Hazaribagh tanneries in Savar, some 20 km west of Hazaribagh, has suffered from bureaucratic delays for almost two decades. At the same time, the tannery associations have delayed actual relocation while trying to extract additional compensation from the government.

Timeline of Ignored DeadlinesAugust 7, 1986: Government orders 903 polluting factories (including 176 tanneries) to adopt measures to control their pollution within three years. July 15, 2001: High Court of Bangladesh orders polluting factories (including the Hazaribagh tanneries) to adopt adequate measures to control pollution within one year. January 27, 2002: Then-Prime Minister Khaleda Zia announces that the Hazaribagh tanneries will relocate outside Dhaka. The Dhaka Tannery Estate Project (to develop a suitable relocation area in Savar) is scheduled to be completed by December 2005. This deadline is extended until December 2006, then June 2010, then June 2012. September 25, 2008: Government meeting headed by the joint secretary, Ministry of Industries resolves that all tanneries shall shift from Hazaribagh by February 2010. June 23, 2009: High Court of Bangladesh orders that the tanneries relocate from Hazaribagh by February 28, 2010, “failing which [they] shall be shut down.” February 28, 2010: The government and tannery associations ask the High Court to extend the relocation deadline by two years; the High Court extends the deadline for relocation by an additional six months to August 28, 2010. October 30, 2010: The government and tannery associations again ask the High Court to extend the relocation deadline by two years; the High Court extends the deadline by a second period of six months, to April 30, 2011. April 30, 2011: The High Court’s deadline for relocation expires. June 1, 2011: The minister of the environment tells parliament that the Hazaribagh tanneries will be relocated by the end of 2012. December 2011: The Ministry of Industries seeks to extend the Dhaka Tannery Estate Project for three years beyond the June 2012 deadline. March 2012: The minister of industries tells a press conference that he expects the relocation of tanneries will be completed “within 15 to 18 months.” |

An Enforcement-Free Zone

According to Bangladeshi law, two government offices are responsible for addressing the situation in Hazaribagh: the Ministry of Labour’s Inspection Department (with respect to occupational health and safety protections for workers, paid sick leave and injury compensation, prohibitions on hazardous child labor, and adequate treatment of industrial effluent) and the Department of Environment (with respect to environmental monitoring and enforcement).

Government officials from both departments admitted to Human Rights Watch that, in practice, they are not upholding Bangladesh’s laws with respect to Hazaribagh’s tanneries.

Department of Environment officials told Human Rights Watch that the department does not regularly monitor effluent from the tanneries flowing through the neighborhood, seeping into the ground, pooling in stagnant ponds, or making its way into Dhaka’s main river. The same officials explained that the department does not monitor air or soil quality in Hazaribagh or take legal action against tanneries in Hazaribagh for violating environmental laws.[45] One department official put it in stark terms: “There is no monitoring and no enforcement in Hazaribagh.”[46]

Officials explained that there is a de facto policy not to monitor or enforce environmental laws because the Ministry of Industries is preparing a site in Savar for relocation of the tanneries. (The relocation project is discussed in more detail below.) In the words of one official who requested anonymity, “Since the plan to shift [to Savar], the Department of Environment has been inactive [in Hazaribagh].”[47]

The Department of Environment considers the Hazaribagh area to be the responsibility of the Ministry of Industries.[48] In effect, the Department of Environment has suspended its legal powers to monitor and enforce environmental laws in Hazaribagh.[49]

Representatives of the two tannery associations confirmed the Department of Environment’s de facto policy of non-enforcement. The chairman of one of the two main tannery associations explained that, “the Department of Environment and the Government may be a little soft towards us, because it is not possible for us to stop working as we are.” The chairman of the other main tannery association told Human Rights Watch that, “[There is no monitoring or enforcement because] the Department of Environment in our government is kind enough to give us time to relocate to Savar.”[50]

The other government office is the Inspection Department under the Ministry of Labour, which is responsible for monitoring employers’ adherence to the Labour Act.[51]

While labor inspectors claim to inspect a small number of Hazaribagh tanneries each month, the deputy chief inspector responsible for Dhaka admitted to Human Rights Watch that “the Hazaribagh tanneries are barely touched [by us].”[52]

Asked why, officials from the Ministry of Labour’s Inspection Department told Human Rights Watch that the Inspection Department is incapable of fulfilling its statutory obligations because of resource restraints.[53] A factory inspector who works in Hazaribagh explained, “We are not able to make factories comply with some sections of the law because of manpower shortages.”[54]

The deputy chief inspector for Dhaka noted that he had 18 inspectors and assistant inspectors to cover an estimated 100,000 factories in Dhaka—a limitation that means the Inspection Department mainly focuses on monitoring conditions in garment factories:

We are very busy because of garment factories. Our GDP depends on the ready-made garment [sector], so the focus is there. We can’t focus on just one sector like tanneries.[55]

But resource constraints are not the only factor limiting oversight. Officials explained they considered it a priority to maintain good relations with factory managers, which means it is normal practice to give factories advance notice of a visit. A deputy chief inspector explained:

We always try to maintain good relations with management. Usually we give advance notice [of an inspection]. Sometimes we send a letter, sometimes we phone if the number is available.[56]

A factory inspector who works in Hazaribagh explained that he visits about five tanneries each month and that, to his knowledge, no tannery in Hazaribagh has an effluent treatment plant.He told Human Rights Watch that, while the Inspection Department has sent some letters to some tanneries in Hazaribagh regarding their violations of the Labour Act, it has not prosecuted any tanneries for offences under the act.[57] Another government official, who requested anonymity, confirmed to Human Rights Watch there were no cases against Hazaribagh tanneries for any violations of the Labour Act.[58]

The High Court Ignored

The government has repeatedly ignored High Court rulings relating to the Hazaribagh tanneries.

In 2001, the High Court ordered some factories that the Department of Environment had categorized as heavily polluting to install means to treat their effluent within one year. The High Court was referring to a list of 903 factories—including 176 tanneries—that the department had identified in 1986 as heavy polluters.

The High Court based its decision on the Bangladeshi constitution, which orders the government to improve public health and guarantees all citizens the right to life.[59] In essence, the High Court ordered the Department of Environment to enforce existing environmental laws.[60] The government subsequently ignored the decision, as it had the laws the court cited.

In 2009, the Hazaribagh tannery issue was back in the High Court, which found that despite directions being given eight years prior:

[D]uring this period the pollution continued unabated, rather, increased manifolds, especially from the tanneries at Hazaribagh, threatening the civic life of the inhabitants of the city of Dhaka...[61]

In 2009, the High Court again found that the Department of Environment had failed to implement environmental laws and described the conduct of department officials as “highly deplorable.” It repeated its order that heavily polluting factories must treat their effluent. It specifically ordered the Hazaribagh tanneries move out of Hazaribagh by February 28, 2010, “failing which those shall be shut down.”

The 2009 judgment ordered the Department of Environment to “ensure that these directions are complied with to the letter and spirit without any exception.” It also ordered the minister of industries, metropolitan police commissioner (Dhaka) and the inspector general of police (Bangladesh) to cooperate with the Department of Environment to ensure enforcement of the court’s orders.[62]

When the February 28, 2010 deadline approached, the government and tannery associations asked the High Court to extend the relocation deadline by two years (the beginning of 2012). The lawyer who represented the tannery associations in their February 2010 petition to the High Court for a period of time was Sheikh Fazle Noor Taposh—the member of parliament for Hazaribagh who is also Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s nephew.[63]

The court responded by extending the deadline for relocation by an additional six months, to August 28, 2010. That deadline came and went. In October 2010, the government again asked the High Court to extend the relocation deadline by two years, and the High Court again extended the deadline by six months, to April 30, 2011. The High Court’s second extension of the deadline expired without the government moving to enforce the orders.

In an interview with Human Rights Watch, Sheikh Fazle Noor Taposh denied that acting as the lawyer for the tannery associations in February 2010 was a conflict of interest:

There was no conflict of interest. The government wants the relocation; the [tannery] industry understands it has to relocate. I acted as a catalyst, to bridge the gap between all parties, to coordinate between [the tannery] industry and the people I represent as a member of parliament.

Presented with the view that the tanneries in Hazaribagh were not relocating to Savar because they were politically well-connected, he replied: “I don’t know what these people [who level that criticism] mean. Everybody’s politically connected in Bangladesh.”[64]

Relocation Delays

Bangladeshi governments have contemplated relocating the Hazaribagh tanneries for almost two decades.[65] One Ministry of Labour official said he had been hearing about such a move since he began working at the ministry in 1993.[66]

In January 2003, then-Prime Minister Khaleda Zia announced a plan to set up a leather industry estate in Savar, to be completed by the end of 2005.[67] That deadline—as with the numerous deadlines that followed—passed without consequence (see text box: Timeline of Ignored Deadlines).

The official government position (as of this writing) is that the tanneries will relocate by the end of 2013, after a central effluent treatment plant is built in Savar. The Savar CETP, intended to significantly reduce the volume and pollution load of a maximum 21,600 cubic meters of tannery effluent a day, underwent an environmental impact assessment in 2005.[68] After numerous tenders for constructing the CETP, and wrangling between tendering companies in the High Court, a Chinese company was finally awarded the tender in March 2012.[69] Ominously, in interviews with Human Rights Watch, government officials were at odds as to when the Savar CETP will be completed: some said June 2013, others said the end of 2013.[70] In March 2012, Bangladeshi media quoted the minister of industries as stating the relocation of the tanneries will be completed by the end of 2013.[71]

Many of the previous delays of the relocation plan are due to the glacial pace of government bureaucracy in Bangladesh—as mentioned in an article that appeared in one Bangladeshi newspaper 12 years ago.

The planned relocation of some 300 tanneries from Hazaribagh area to somewhere outside the capital [city] still remains a far cry, although the entire process of shifting would require only one year’s time. The delay, concerned sources said, is because of unwillingness on the part of some tannery owners, as well as the slow pace of movement of files by the [government] bureaucracy.[72]

Compounding these bureaucratic delays, the tannery associations continue their quest for the most favorable economic terms possible from the government. One Ministry of Industries official described tanneries as “reluctant” to relocate, while a Department of Environment official explained: “We have suggested they move, but there is bargaining.”[73]

In an interview with Human Rights Watch, Sheikh Fazle Noor Taposh, the member of parliament for Hazaribagh, explained that the government had agreed to compensate the tanneries for some relocation costs, and described the government negotiations with the tanneries over compensation for relocation as “settled.” He told Human Rights Watch that “the government’s committee assessed [total] compensation at 2.5 billion taka ($31 million). The tanneries accepted it.”[74]

But officials with the two tannery associations say that is not the case, telling Human Rights Watch that they have recently requested considerably more compensation than 2.5 billion taka ($31 million). In June 2012, the chairman of the Bangladesh Finished Leather, Leather Goods and Footwear Exporters Association said the association is currently demanding three things from the government: more land than the current site in Savar, government assistance for tanneries in Hazaribagh whose land is mortgaged, and more compensation than previously agreed. On the issue of compensation, he explained:

In 2006 we had asked for 10.9 billion taka ($134 million) [in compensation] for the machines, factory, labor and other things related to building new tanneries. At that time, there was a government committee that agreed to 2.5 billion taka ($31 million) of this demand. Now that prices have gone up, the demand is 35 billion taka ($428 million). In proportion with the original offer [2.5 billion taka, or $31 million], if you calculate the percentage increase, the government should give us 8 billion taka ($98 million).

He added:

We’re hopeful that the government will meet our demands. If they don’t, it won’t be possible to shift and this [situation] will be the government’s liability.[75]

The chairman of the other main association of tanneries (the Bangladesh Tanners Association) told Human Rights Watch that the members of his association were ready to move to Savar because of the environmental problems that the tanneries cause. But he explained that the association had requested low-interest loans from the government, as well as 10 billion taka ($122 million) in compensation to cover the costs of relocation. He told Human Rights Watch that he thought relocation would require a further three years while the central effluent treatment plant is built.[76]

Some of those interviewed by Human Rights Watch in the course of this research believe that relocation will not take place until at least 2015.[77] Others associated with the leather tanneries in Hazaribagh, who requested anonymity because they feared retribution for speaking publicly, suggested that relocation would not take place until about 2017.[78]

Human Rights Watch visited the relocation site in Savar in May 2012: it was a large grass-covered area with roads, drains, and electrical wires. Some tanneries reserved plots in the relocation site by means of small concrete signs announcing their names. No tannery had yet commenced constructing new premises.

An Occupational Health and Safety Crisis

Because the Ministry of Labour’s Inspection Department does not routinely monitor the Hazaribagh tanneries, there are no reliable statistics on the number of workplace deaths and serious injuries among tannery workers. However, Bangladeshi newspapers often report deaths of Hazaribagh tannery workers. For example:

- In March 2005, a worker died after a boiler explosion.[79]

- In March 2010, three tannery workers died after inhaling toxic fumes.[80]

- In December 2011, a tannery worker died after collapsing under a load.[81]

- In April 2012, a tannery worker died from electrocution.[82]

While Human Rights Watch did not systematically review news accounts or investigate the circumstances of these particular accidents, such reports indicate how dangerous tannery work can be. Interviews with Hazaribagh tannery workers suggested the same. Balish, a man in his mid-20s, described a horrific workplace accident involving corrosive acid.[83]

In November [2011] in one tannery a man had an accident with acid. The acid fell on his arm and all the flesh came off. You could see the bones. Something happened to his tendons and now he can’t straighten his arm. He’ll never use that arm again.[84]

Many common and obvious health problems of tannery workers—such as skin diseases and respiratory illnesses—are the result of repeated exposure to hazardous chemicals when measuring and mixing chemicals, adding chemicals to hides in drums, or manipulating hides saturated in chemicals.

Chemicals used in tanning can be injurious to human health if proper safety precautions are not taken; some are known to be confirmed or potential human carcinogens, the effects of which can only be observed years after exposure.[85] Despite this, many workers complained that their tannery did not supply protective equipment such as gloves, masks, boots, and aprons, or supplied it in insufficient quantities. Other workers told Human Rights Watch they suffered serious accidents working with tannery machines that are old and poorly maintained, or for which they had little or no training.

None of the tannery workers interviewed during this research had a written employment contract. In their place are a variety of employment arrangements, some of which deny workers legal entitlements such as paid sick leave or compensation when workers become ill or injured because of their work.

Worker Exposure to Chemicals

The doctor said, “If you continue working here, this will never heal.”

—Kolom, a tannery worker in his early 20s describing the rash on his arm, Dhaka, May 4, 2012[86]

Tanneries in Hazaribagh use a vast assortment of chemicals. Leather technologists told Human Rights Watch that each of the three stages of leather processing commonly involves around 20 chemicals.[87] One academic study noted:

[In Hazaribagh] about 2000-3000 metric tons of sodium sulfide and nearly 3000 metric tons of basic chromium sulfate, in addition to other chemicals, are used each year for leather processing and tanning. These other chemicals include non-ionic wetting agents, bactericides, soda ash, calcium oxide, ammonium sulfate, ammonium chloride, enzymes, sodium bisulfate, sodium chlorite, sodium hypochlorite, sodium chloride, sulfuric acid, formic acid, sodium formate, sodium bicarbonate, vegetable tannins, syntans, resins, polyurethane, dyes, fat emulsions, pigments, binders, waxes, lacquers and formaldehyde. Various types of process and finishing solvents and auxiliaries are used as well.[88]

Some workers come in direct contact with chemicals when they touch them without protective gloves, aprons or boots, or inhale them in poorly ventilated spaces without protective masks.

In many cases, such contact is injurious to human health. For example, sodium sulfide, sulfuric acid, and formic acid can corrode or burn tissue and membrane of the eyes, the skin, and the respiratory tract. Inhalation of sulfuric and formic acid vapors can cause lung edema (fluid accumulation in the lungs).[89] Short-term exposure to sodium carbonate irritates the eyes, skin, and respiratory tract, while repeated exposure can result in dermatitis and perforation of the nasal septum.[90] Sodium metabisulfite is severely irritating to gastrointestinal tract and inhalation may cause reactions similar to asthma.[91]

Chemicals that tannery workers must use in the tanning process, particularly at the “wet blue” stage, give off gases such as hydrogen sulfide, sulfur dioxide, and ammonia. Short-term exposure by breathing in hydrogen sulfide may result in unconsciousness, lung edema, and affect the central nervous system. Exposure of high concentrations may result in death.[92] Ammonia gas can corrode tissue and membrane of the eyes, the skin and the respiratory tract. Inhalation of high concentrations may cause lung edema.[93] Repeated or prolonged inhalation of sulfur dioxide may trigger asthma attacks in asthmatics.[94]

Basic chromium sulfate is the mostly commonly used chemical in Hazaribagh.[95] It is irritating to the respiratory tract and should only be handled with protective gloves, safety goggles, and breathing protection.[96] Some studies have found that chronic occupational exposure to trivalent chromium (which can form part of basic chromium sulfate) can lead to a detectable increase in lymphocyte DNA damage, which may increase the risk of cancer.[97] Other reports have noted the risks to tannery worker health when, under certain conditions, trivalent chromium may convert to hexavalent chromium (a known human carcinogen) during the tanning process.[98]

Leather technicians told Human Rights Watch that Hazaribagh tanneries use several chemicals that are confirmed or potential carcinogens.[99] Formaldehyde (used as a re-tanning agent and a preservative) is carcinogenic to humans.[100] Azocolorants (for leather dyeing) can produce aromatic amines considered carcinogenic or potentially carcinogenic.[101] Pentachlorophenol (a preservative) may be carcinogenic in humans and may impact the central nervous system, kidneys, liver, lungs, immune system, and thyroid.[102]

The World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer considers leather dust, which is generated when leather impregnated with chemicals undergoes mechanical operations such as buffing, as carcinogenic to humans.[103]

Europe, Chemicals, and LeatherMany chemicals for sale in Hazaribagh are produced in Europe, including Switzerland, Germany, and Italy. The main European countries importing leather from Hazaribagh are Italy, Germany, and Spain. The centerpiece of the European Union’s regulatory system on chemicals is the REACH regulation (2006), which aims to mitigate the impact of dangerous chemicals on human health and the environment .[104] It has been lauded as an important development in European chemicals legislation and is expected to influence industries around the world .[105] Yet its impact on the leather supply chain in Bangladesh remains negligible. Many chemicals often used in leather processing are subject to restrictions and/or strict reporting requirements within Europe. These include, among others, azocolorants, hexavalent chromium compounds, and formaldehyde.[106]For all hazardous chemicals, European chemical manufacturers must provide users with a Safety Data Sheet (SDS) outlining protective measures for workers who use the dangerous substance, as well as environmentally safe waste disposal guidelines.[107]According to a leading industry organization, tanneries within Europe have a legal obligation to implement the safety procedures outlined in SDS.[108] When exporting chemicals outside Europe, European chemical companies must still provide a “REACH-compliant” SDS, but the regulation does not identify any mechanism for ensuring non-EU users implement SDS instructions.[109]Tanneries outside Europe do not have direct obligations under REACH regulations. European importers of leather and leather goods are responsible for checking that the imported leather is in line with REACH regulations. As the European Chemical Agency points out, the extent of this obligation is to ensure the imported goods do not contain certain restricted substances over certain concentrations. European importers may test the leather from Hazaribagh for these substances. [110] The REACH regulation does not require chemical exporters, or leather importers, to seek information on how hazardous chemicals are used in the tanning process—such as whether the tanneries treat wastewater before release, or whether tanneries ensure that workers follow the recommended safety precautions. |

Illnesses and Other Health Problems

Many tannery workers told Human Rights Watch that their work caused them to experience headaches, body aches, dizziness, and nausea.[111] Skin diseases such as fungal infections, contact dermatitis (a skin reaction to irritants or allergens), scabies, and urticaria (a skin rash known as hives) are widely prevalent among tannery workers, according to studies.[112]

Kapor, in his mid-40s, has worked in a large tannery for 10 years. When he spoke with Human Rights Watch, one leg and foot were swollen, and the shin was heavily scarred, with three lacerations that were swollen, pink in color, and apparently infected. He scratched his leg constantly during the interview, in which he told Human Rights Watch that he had suffered from this skin disease for the previous eight months.

Mostly we touch the chemicals when we take the “wet blue” leather out of the drums. I wear gloves and boots but that doesn’t really make a difference. I don’t wear a mask…. There are 15 or 16 of us who work with the drums [in my tannery] and all of us have some sort of skin problems.[113]

Kaath, in his early 20s, works in one of the large “job work” tanneries. He showed Human Rights Watch his arms, which were scarred and covered by small raised spots. Both his palms displayed black and pink discoloration, and skin on the palms was peeling off.

This [skin disease] started two to three months ago, it happened because of “bhushan” [a common name for a bactericide and fungicide chemical]. I take the white powder in a bowl and pour it into the drum machine. I wear gloves but sometimes it gets inside. When it touches my skin it burns, the skin comes off and later it itches.[114]

Baksho, in his late 20s, works in a large tannery. He showed Human Rights Watch his hands, which appeared prematurely aged with heavy wrinkles and thickened skin. He complained that he suffers illnesses such as fever, coughs, and headaches because of his work, which involves measuring out chemicals. He also complained of intense itchiness all over his body.

There are certain kinds of chemicals that cause a lot of damage to us. One of these chemicals is chrome, which is blue in color. I use gloves but the fumes are really bad. Although we wear masks, it doesn’t really protect us from the chemical powders. I have itches on my body all the time. I get a strong itch mostly at night, on my arms. There are 10 or 15 people in my tannery that have the same problems I do.

He added that a doctor he had seen advised him to leave the tannery if he wanted to get better. “But I don’t have any education so I can’t get another job,” Baksho said.[115]

No Cancer SurveillanceSome chemicals used in the Hazaribagh tanneries are human carcinogens. Studies from around the world have investigated the prevalence of particular cancers among tannery workers. One paper in 2007 provided an overview of studies documenting high rates of cancers among tannery workers, including lung cancer, testicular cancer, soft tissue sarcoma, pancreatic cancer, and bladder cancer. [116] The World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer considers leather dust, which is generated by mechanical tanning operations such as buffing leather impregnated with chemicals, as carcinogenic to humans. [117] Human Rights Watch is not aware of any epidemiological studies on cancer among tannery workers in Bangladesh. There is some anecdotal evidence for high rates of cancers among workers working with chemicals. For example, a former leather technologist who had worked in tanneries for 30 years told Human Rights Watch: Perhaps 10 of my friends who are leather technologists have died of cancer, mostly lung cancers, liver cancer, and esophagus cancers. We [leather technologists] deal with many cancerous and poisonous chemicals. [118] The National Institute of Cancer Research and Hospital has maintained a cancer registry of patients since 2005. However, when Human Rights Watch asked the director of the National Institute of Cancer Research and Hospital for data on the prevalence of cancer in Hazaribagh and by profession (such as tannery worker) among hospital patients, he said the institute “does not keep this sort of data.” [119] This lack of cancer surveillance is accompanied by a lack of information on the health effects of exposure to tannery chemicals. Purono, in his early 20s, who works daily with chemicals, said: “We’re told nothing about the properties of the chemicals, like which are particularly dangerous.” [120] Workers told Human Rights Watch that they were worried about the potential for occupational cancer. Baksho, who is in his late 20s and works daily with chemicals, told Human Rights Watch: “We don’t know what’s happening inside us, we may have cancer.”[121] Agrahayan, a tannery worker in his mid-20s who works daily with chemicals, said, “I’m worried about my health because I think the people who live in this area will live less than others. I’m sure a lot of people around here have got cancer.” [122] |

Astha is about 20 years old. She worked processing “wet blue” hides in two smaller tanneries for six months, although she resigned from her work in these tanneries four months before Human Rights Watch talked with her because she fell sick. She explained that the tannery pits are filled with the raw hides and lime, acids, and other chemicals that have soaked the hides in the drums.

We had to get inside the pit [to remove the hides]. As soon as the water touched our legs, it would start itching. We had boots but water would get into them. We all tried to finish that work quickly as possible. But it took more than an hour in the pits because there were many hides in the pits, sometimes more than one thousand.[123]

During six months in the tanneries Astha lost weight, she suffered from a swollen hand and developed some form of kidney problem.[124] She explained that “the doctor said I was working with chemicals too much. When my hand became swollen, my husband told me to stop working.” She said she was “lucky” to have stopped working in the tanneries, but added “others work there because they have no choice.”[125]

No Protective Equipment

While some workers told Human Rights Watch that the tannery in which they worked supplied protective equipment such as gloves, masks, boots, and aprons, many others complained that their tannery did not provide protective equipment, or provided it in insufficient quantities. According to studies, the failure of tannery management to provide protective equipment to tannery workers in Hazaribagh is common.[126]

Shada is a worker in her 40s who has been employed by a large tannery for the last five years. She told Human Rights Watch that her work involves rubbing finishing chemicals onto the leather and that the tannery requests that she does this with bare hands.

We’ve asked for gloves but they didn’t give them to us. They say we have to use our hands. I have heart problems because of the rubbing of the hides I have to do. It’s on the left side of my chest, I feel sharp pains here. I’ve never had this problem before in my life, only the last three or four years.[127]

Balish, in his mid-20s, works as a chemical technician for several tanneries. He showed Human Rights Watch a scar on his forearm from where he said that “bangla acid” (a common name in Hazaribagh for sulfuric acid) had fallen and burned his skin two years ago. He described how the tanneries he works with do not provide adequate protective equipment; like other workers Human Rights Watch talked to, he considered that “there’s nothing I can do, I have to work.” Balish said:

Long [arm] gloves cost 70 taka ($0.85). We need four or five gloves a month because they are not very durable. The owners will say they’ve given us gloves but it will be one pair each month. That’s why the work is so dangerous. When we ask for gloves, they say “You don’t need to use gloves for this work” but we know we do.[128]

Poribar is a man in his early 30s who worked in his most recent tannery for eight years. Three months prior to his interview with Human Rights Watch he had quit his job as a foreman in the tannery due to concern for his health. He described how he had four stomach operations over the last decade, explaining, “The doctors said I had breathed in gases and this caused problems in my stomach.”[129] He also complained that the owners of the tannery did not provide him or other workers with masks or gloves.

When the hides are raw there are many acids, lime, and sodium on them. When I touched them with my hands, my hands are affected. If there’s a small cut, it will become much worse. The owner didn’t give us any gloves. The same with masks—we were never given them. If we’d been given them we would use them.[130]

Meru is a man in his early 20s. He showed Human Rights Watch hands that appeared to be those of a very old man. The skin was thick and heavily creased and there was an unnatural white color in the skin creases. Two fingernails of one hand were yellow and corroded away to rough stumps. Meru told Human Rights Watch that his work in the tanneries involves soaking the hides with lime, sodium, and other chemicals and then putting them through machines.

I do have gloves to put the hide into the machine but they are sometimes ripped, the boots too. The company won’t replace them, so whatever condition they’re in I’ll use them. That’s why my hands are like this. A lot of workers have hands like this. I’ve asked for new gloves: they say they’ll give them but they take a lot of time before we get them, maybe 15 days after we ask for them.[131]