Maps

Summary

My children have been poisoned and there is nothing I can do to help them.

—Sun, Henan province, May 2010

Hundreds of thousands of children in China are suffering permanent mental and physical disabilities as a result of lead poisoning. Many of them live in poor, polluted villages next to, and surrounded by, lead smelters and battery factories. Often, their parents work in these factories, bringing more lead into their homes on their clothes, boots, and hands.

China today has the world’s largest population and second largest economy. The country’s gross domestic product has increased ten-fold in the last 15 years. That rise in gross domestic product (GDP) growth has helped lift 200 million people out of absolute poverty since 1978. But this rapid economic development has also exacted a steep environmental price; widespread industrial pollution that has contaminated water, soil, and air and put the health of millions of people—likely even hundreds of millions—at risk. Currently, 20 of the world’s 30 most polluted cities are in China.

Pollution from lead is highly toxic and can interrupt the body’s neurological, biological, and cognitive functions. Children are particularly susceptible, and high levels of lead exposure can cause reduced IQ and attention span, reading and learning disabilities, behavioral problems, hearing loss, and disruption in the development of visual and motor functioning. High levels of lead can cause anemia, brain, liver, kidney, nerve, and stomach damage, as well as comas, convulsions, and even death. Worldwide, lead poisoning kills 230,000 people each year.

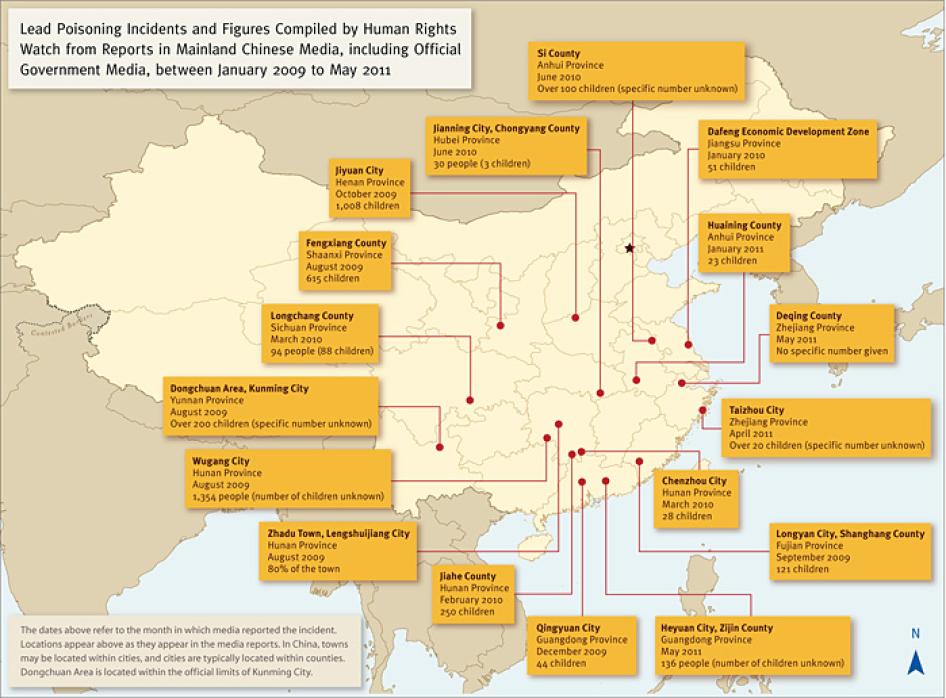

Today, lead poisoning is among the most common pediatric health problems in China.While the lack of comprehensive data makes it difficult to determine the extent of the epidemic, a number of sources—including academic and media reports—indicate it is a public health emergency affecting whole communities.

The Chinese government’s ill regard for human rights means it has been able to pursue a model of economic development that is not accountable to its citizens, including poor people who are often particularly susceptible to the most damaging health effects of environmental hazards. But industrial pollution, and the lack of accountability that accompanies it, extends far beyond health issues: it impacts the full realization of human rights in China, including people’s right to life, health, an adequate standard of living, as well as to information, participation, and access to justice.

Underpinning China’s lead poisoning epidemic is a tension between the government’s goals for economic growth and its efforts to curb environmental degradation. The Chinese government has developed numerous laws, regulations, and action plans designed to cut emissions, encourage more environmentally-friendly industries and decrease pollution. Yet these policies are in competition with the Chinese government’s goals for economic development; the first guiding principle of the country’s Twelfth Five-year Plan for Environmental Protection (2011-2015) is “optimizing economic development.”

At the local level, such policy contradictions may encourage factories to cut corners on emissions standards. Corruption and conflict of interest can also undermine environmental protection efforts. Local officials, who often have a legal or financial role in local factories, may be resistant to implementing environmentally friendly technology. Existing environmental laws often lack effective enforcement mechanisms.

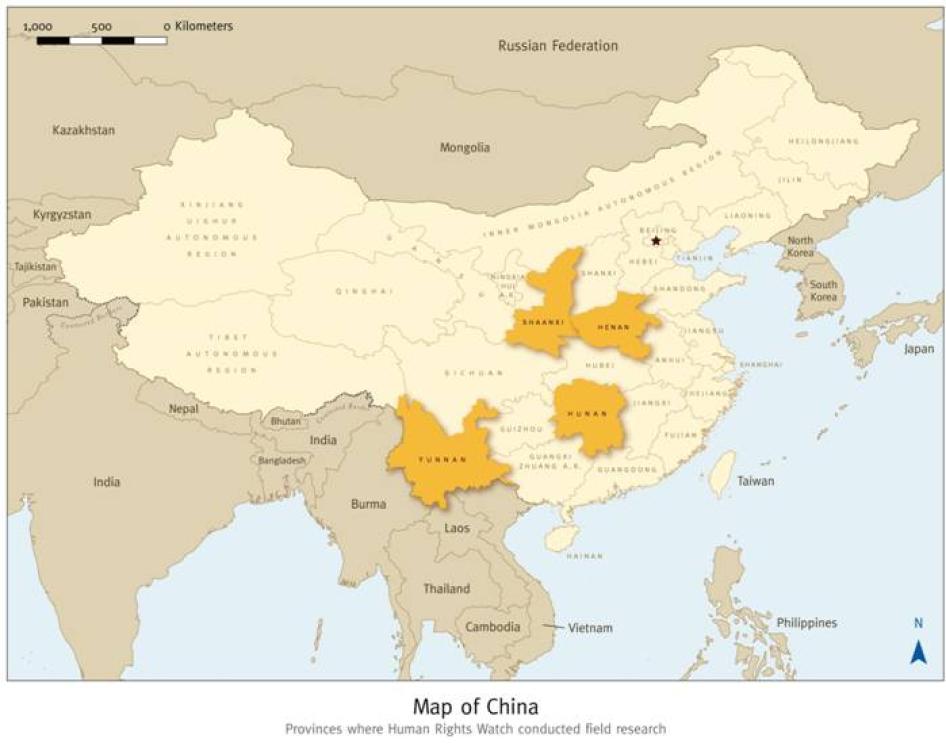

This report—based on interviews in Henan, Hunan, Shaanxi, and Yunnan provinces, and research in Beijing and Shanghai between late 2009 and early 2010 — finds that local governments have imposed arbitrary limits on access to blood lead testing; refused appropriate treatment to children and adults with critically high lead levels; withheld and failed to explain test results showing unaccountable improvements in lead levels; and denied the scope and severity of lead poisoning.

Parents said that government officials told them that only children living within one kilometer of a factory smokestack were at risk and that milk was adequate treatment for lead poisoning. Parents reported that local police threatened individuals seeking treatment and information, and those trying to protest against polluting factories have been arrested. Journalists told us they have been intimidated and threatened when trying to report on lead poisoning.

Meanwhile local Environmental Protection Bureaus (EPBs), staffed and supervised by local government officials, have done little to fulfill their obligation to monitor emissions, disseminate information to the public about polluting factories, and enforce environmental regulations that stipulate a factory or polluting entity must be improved or removed when it endangers public health.

Among the many government abuses that Human Rights Watch documented that directly compromised the health of children and adults at risk for lead poisoning are:

Testing Practices

Although local governments have provided some free testing for children under the age of 14, in the areas we visited with acute lead poisoning, seemingly arbitrary restrictions on testing restricted the ability of individuals to access free testing. In some cases, children were denied testing, even when parents were willing to pay for it.

Many parents in Henan and Shaanxi, suspicious about false results showing normal blood lead levels (BLLs), brought their children to towns outside the contaminated area for testing. In every case, these results were much higher than those provided by the local hospital or the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CCDC). In Yunnan, many parents said they were denied access to their children’s results and simply told the results were normal.

Access to Information

In Hunan, Henan, Shaanxi, and Yunnan provinces, parents said they only learned that local factories were polluting at toxic levels when their children fell ill. In each province, they said they received no information about the health risks associated with the pollution, including any risk or medical consequences of lead poisoning.

Journalists who reported on lead poisoning told Human Rights Watch that police had followed them or forced them to leave the area when they tried to interview people. A foreign journalist who had been to a polluted site in Hunan said police had questioned his driver, as well as people he had interviewed. A journalist reporting on lead poisoning in Shaanxi was also forced to leave.

Access to Medical Treatment

Parents of children with dangerously high blood lead levels in all four provinces were unable to access effective treatment. They reported that health workers and government officials told them to feed their children specific foods, including apples, garlic, milk, and eggs. In rare cases children were given medicine but inconsistently and without medical supervision. In nearly every case, children were returned to their homes to face ongoing exposure to lead with dangerous and potentially deadly consequences.

Intimidation by Police and Government Officials

In all four provinces, villagers told Human Rights Watch they were scared to ask government officials for more help or information. In Shaanxi province, villagers said police had detained people protesting outside a lead-processing factory. In Hunan, seven people were arrested while trying to seek help for their children.

Remediation and Long-Term Solutions

Most families said they were not financially able to move to an unpolluted area. Villagers in Shaanxi said the government had announced plans to move residents from several villages to other areas but did not know when or if this will happen, where they are supposed to go, and/or how they would earn a living in a new area.

In villages where lead exposure is highest, a generation of cognitively and physically disabled children will need significant and ongoing support. Most parents Human Rights Watch spoke with were generally unaware of these long-term consequences of lead exposure. However, some said their children were already struggling: failing physically or underperforming in school. Yet neither the schools nor the local government had offered special services or opportunities for children with lead poisoning. These needs will become even more acute as the years pass and lead poisoning continues to be neglected.

Occupational Health

In addition to researching the effects of lead on the communities surrounding polluting factories, Human Rights Watch interviewed family members of a female worker in a lead processing plant in Yunnan who died of acute lead poisoning. Human Rights Watch also interviewed individuals concerned about the absence of adequate worker protections. According to workers in Yunnan, Henan, and Shaanxi, blood lead tests and safety measures are not routine practice.

***

The Chinese people have already suffered grave consequences as a result of inappropriate and inadequate responses to public health crises. During the 1990s and early 2000s, local officials in Henan and other provinces ran programs for impoverished farmers to sell their blood plasma and platelets. The program was unsanitary and unsafe, but selling blood plasma was profitable for officials, and they continued to deny evidence of an emerging HIV epidemic. Tens of thousands were infected, nearly a majority of adults in some villages, and the public health consequences continue. Similarly, in 2003, SARS was first denied and then downplayed by government health officials who censored media and lied to international health agencies, resulting in ongoing transmission and unnecessary suffering and deaths.

The Chinese government’s response to AIDS and SARS was characterized by corruption, cover-up, and harassment of media and health activists, resulting in a delayed and ineffective public health response. The response to lead poisoning has so far followed this same road, but it is not too late for the Chinese government to take a different approach.

The Chinese government has repeatedly and voluntarily pledged in public statements, in domestic law, and in international treaties to protect the fundamental human rights of its citizens, including their right to the highest attainable standard of health. It must ensure that laws that safeguard human health against environmental hazards are implemented locally and followed consistently. When health is compromised, the government needs to act swiftly to provide health information and evidence-based medical treatment. Further, the government must hold accountable those responsible for protecting the community’s health and wellbeing when they choose actions that instead endanger or neglect health.

Recommendations

To the Government of the People’s Republic of China

- Ensure that government officials who are suspected of failing to uphold environmental regulations or preventing people from accessing medical care are investigated and held accountable.

- Invite the special rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health and the United Nations independent expert on the issue of human rights obligations related to access to safe drinking water and sanitation to lead an independent inquiry into the impact of industrial lead poisoning in China.

To the Local Governments across China Facing Widespread Lead Poisoning

- Conduct surveillance to determine the extent of lead poisoning affecting communities.

- Where surveillance indicates lead poisoning, take immediate actions to identify and eliminate sources of lead pollution and to treat those affected. Ensure that local residents are informed of the results of surveillance efforts and the measures being taken in response.

- If contamination is severe enough to require the community’s relocation:

- Begin a relocation process that includes community participation. Attention should be paid to the UN Basic Principles and Guidelines on Development-based Evictions and Displacement. Relocation should, as far as possible, provide equivalent land, facilities, and opportunity to earn an income that permits an adequate standard of living as that provided by the land from which communities are forced to relocate.

- Provide affected communities with regular and accurate information regarding relocation, including a timetable, and any economic, health, or educational services that will be provided.

- When blood lead testing shows elevated levels of lead, provide referrals to social services to ensure that children and adults who have, or may develop, physical and cognitive disabilities as a result of lead poisoning receive disability-related services, including educational, employment, and financial assistance, as guaranteed under Chinese law.

- Allow communities to exercise their rights to assembly and expression in seeking remedies in relation to environmental contamination. Stop all arbitrary arrests of individuals who are exercising these fundamental rights.

- Stop the harassment and obstruction of journalists seeking to report on environmental pollution and its impact on communities and arbitrary detention and arrests of parents and community members seeking information and remedies to environmental contamination.

To the Environmental Protection Bureau of the Chinese Government

- Test all factories for pollution levels that surpass national guidelines, prioritizing factories that are located close to residential areas; that have not had environmental impact assessments; and which have been the focus of inquiries about contamination without proper investigation.

- Shut down factories found to have pollution levels that surpass national standards or put in place lead mitigation systems to reduce exposure to toxic chemicals, both for the workers inside and local communities. Ensure affected communities receive information on the environment and health consequences of contamination.

- Revise laws by closing loopholes to ensure that factories which endanger people’s health cannot continue to operate by paying a fine without further measures.

- Ensure that local Environmental Protection Bureaus have the staff, resources, and accountability mechanisms to implement and enforce the Environmental Protection Law and other legislation protecting health and the environment.

- Ensure that government officials do not have ownership or financial interests in industrial facilities under their direct supervision and strengthen monitoring of government officials to identify conflicts of interest.

- Devise a comprehensive environmental clean-up strategy for all lead contaminated areas in China.

- Provide citizens with environmental information in an accessible format that they are entitled to by law.

To the Ministry of Health at the National and Provincial Levels

- Use scientifically sound methods to designate the accurate area of risk for lead exposure and ensure all people within that area are offered free blood lead testing.

- Ensure that no one, regardless of residency or proximity to lead poisoning areas, is denied access to blood lead tests.

- Put in place quality control measures and oversight to ensure that each individual who is tested receives accurate test results.

- Provide evidence-based medical treatment and case management for lead poisoning to all in need, consistently across provinces.

- Work with the local government to ensure that all children receiving treatment are removed from the area of contamination.

- Ensure that all affected communities have access to information on lead poisoning.

- Devise a comprehensive public health strategy to tackle chronic lead exposure and its long-term consequences in China.

- To the Ministry of Education at the National and Provincial Levels

- Ensure that all children who have developmental disabilities as a result of lead poisoning are able to access appropriate educational opportunities.

To the World Health Organization

- Provide technical expertise to the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention to ensure accuracy of blood lead level testing.

- Work with the Ministry of Health to develop a comprehensive treatment plan for children and adults with elevated blood lead levels.

To Foreign Companies Sourcing Materials from China

- Ensure that materials originate from a factory with an environmental impact assessment and that is legally allowed to be operating through the following mechanisms:

- Execution of a social and environmental review by a credible third party of source industrial facility operations.

- Conduct site visits of source industrial facilities to ensure compliance with safeguards aimed to mitigate social and environmental risks.

- Ensure that allegations of hazardous conditions which local populations are exposed to are investigated and resolved.

To Governments and International Organizations Funding or Concerned about Health, Environment and Human Rights Issues in China, including the United States (US) Government and European Union

- Voice concern to the Chinese government about the severity and persistence of industrial pollution in China.

- Strongly condemn the arrests and detention of citizens exercising their legal rights by protesting industrial pollution and lead poisoning in China.

Methodology

Between the second half of 2009 and the first half of 2010, Human Rights Watch conducted research in villages in four different provinces: Henan, Hunan, Shaanxi, and Yunnan, as well as in Beijing and Shanghai.

China does not allow independent, impartial organizations to freely conduct research or monitor human rights abuses; as a result, conducting interviews and gathering credible information presents great challenges.

This report is based on interviews we conducted with 52 parents and grandparents whose children or grandchildren have lead poisoning.[1] Some of the parents and grandparents work in lead processing factories and smelters. We also interviewed the family of a female factory worker who had died of lead poisoning in the previous six weeks and six children who have lead poisoning. In addition we interviewed five journalists who had reported on lead poisoning issues in China and both Chinese and international nongovernmental organization (NGO) workers with familiarity on pollution and lead poisoning in China.

Interviews were conducted in Chinese and English and no incentives were offered or provided to persons interviewed. All participants provided oral informed consent to participate and were assured anonymity. As a result, pseudonyms have been assigned to each individual interviewed and, where relevant, to their child or grandchild. Individuals were assured that they could end the interview at any time or decline to answer any questions, without any negative consequences. In addition to oral statements, some interviewees also gave Human Rights Watch copies of test results and health records. All participants were informed of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and the ways data would be collected and used.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed government officials in two provinces who were responsible for restricting access to villages where high levels of lead poisoning has occurred. For security reasons, names of villages and specific information on their locations are withheld. Because of security concerns, Human Rights Watch did not request interviews with central government officials.

Past and current environmental legislation, regulation, and policy documents in English and Chinese were reviewed, as well as scholarly articles from Western and Chinese journals of environmental health, the United Nations (UN), and US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) health guidelines and Chinese Ministry of Health guidelines. In addition, researchers also reviewed local news reports of lead poisoning, environmental pollution, and environmental protests.

Human Rights Watch research in four provinces found similar trends in each government’s response to the local lead poisoning epidemic, and media and Chinese government reports support our findings. However, several limitations to our research should be considered. First, our research is based on interviews in only 4 of China's 33 provinces. While the problem of pollution and lead poisoning is widespread, local responses may be different in provinces we did not visit. Second, because of security concerns, we were limited in our ability to interview government officials, including government health workers, and were not therefore able to reflect their perspectives on barriers to treatment and the limited scope of testing. While the Chinese GDP has grown rapidly in recent years, healthcare spending has lagged, and rural healthcare facilities are generally under resourced. The extent to which these facilities have failed to effectively respond to the lead crisis because of lack of financial resources or because of other causes is unknown.

In this report, the word “child” refers to anyone under the age of 18. The Convention on the Rights of the Child states, “For the purposes of the present Convention, a child means every human being below the age of eighteen years unless under the law applicable to the child, majority is attained earlier.”[2] China’s Law on the Protection of Minors also defines children as citizens under the age of 18.[3]

I. Background

The Scope and Impact of Pollution in China

Since the late 1970s, China has achieved tremendous economic growth. With the second largest economy in the world, China is widely recognized as an economic superpower.[4] In the past 15 years, the gross domestic product has increased ten-fold.[5] China contributed one-third of global economic growth in 2004 and held 14 percent of the world economy on purchasing parity basis in 2005, second to the United States.[6] The rapid economic growth has lifted millions out of poverty: according to the World Bank, the average income was US$293 in 1985 and $2,025 in 2006.[7]

However, this unprecedented growth has come at a high environmental cost. Rapid development has triggered widespread industrial pollution.[8]China has earned the notorious distinction of having 20 of the world’s 30 most polluted cities.[9] Water, air, and soil pollution in China are dangerously widespread and are garnering international attention as a public health crisis both domestically and abroad.[10]

Contaminated drinking water kills 95,600 people per year in China.[11] Approximately one-third of low-income households depend on surface water as the primary drinking source. Yet even after treatment, only half of China’s 200 major rivers and less than a quarter of its major lakes and reservoirs are considered suitable for human consumption.[12] Widespread pollution exacerbates water scarcity by compelling communities and factories to rely on contaminated water sources.[13] As a result, water scarcity quickly becomes a public health problem. For instance, water scarcity in northern China forced farmers to irrigate approximately 40,000 kilometers with waste water; consequently, crops and soil were contaminated with heavy metal pollutants such as lead and mercury.[14] Water scarcity additionally contributes to the spread of diseases associated with microbial and industrial pollutants. Over 300 million people in China rely on hazardous water sources.[15]

Industrial run off and disasters profoundly impact the safety of the water supply since the release of toxic chemicals can devastate an entire city; for example, Harbin, China’s tenth largest city, was left with no water for its four million residents after a chemical plant explosion in 2005. The city’s water system was shut down for four days as the accident led to the release of 100,000 kg of benzene, aniline, and other heavy metals into the water system.[16]

In addition to severe water pollution, China has the world’s highest levels of air pollution[17] and is the largest emitter of greenhouse gases in the world.[18] The World Health Organization (WHO) reported that an estimated 656,000 Chinese citizens die of diseases triggered by indoor and outdoor air pollution per year,[19] and the level of airborne particulate matter, which includes ozone, nitrogen dioxide, and dust, in Chinese cities consistently violates WHO air quality guidelines.[20] In 2004, the State Environmental Protection Agency (SEPA) conducted a routine monitoring of air quality in 360 cities, and results showed that 70 percent of urban areas failed to meet national ambient air quality standards.[21]

Adverse health effects from air pollution include acute lower respiratory infections, lung cancer, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Compounded by the high prevalence of smoking in China,[22] COPD alone is responsible for one to three million deaths in China every year.[23] Outdoor air pollution is caused by a variety of sources, including motor vehicle emissions, chemical combustion from industrial use, burning of agricultural waste and solid fuels, and use of coal as a primary energy source. Because coal provides 70 percent of China’s electricity, China has become one of the world’s largest emitters of sulphur dioxide, which in turn has increased occurrences of acid rain.[24] The use of coal in China accounts for 25 percent of mercury and 12 percent of carbon dioxide emissions globally.[25]

Heavy metal pollution is also widespread within China. Heavy metals are discharged as waste from various industries such as mining, chemical refineries, textile printing and dyeing, leather tanning, pesticides, animal feed manufacturing, electroplates, battery producers, and smelters, which are electrolytic plants that separate chemical concentrates into a pure form. Heavy metals commonly discharged through air or water pollution include arsenic, mercury, zinc, copper, nickel, chromium, manganese, cadmium, and lead. These elements are all found naturally in the environment. Trace amounts of arsenic, mercury, zinc, copper, manganese, chromium, and nickel in the human body are tolerable; however, overexposure results in adverse health effects.

Although these substances are naturally found within the environment, they may become extremely toxic to the ecosystem in high concentrations. Copper amounts above 0.0002 mg/L become toxic for fish in water and adversely affect other aquatic organisms. Copper toxicity also prevents the development of plants, negatively impacting the process of nutrient absorption and root growth. Chromium inhibits the water self-purification process and kills beneficial microorganisms in water. In animals, chromium may induce birth defects, weaken immune systems, and cause tumors. The accumulation of heavy metals in the soil has also been known to adversely affect plant growth. If heavy metals are prevalent in soil, then plants may absorb the chemicals and become contaminated as well, causing food safety issues.

The dangers of widespread pollution have been acknowledged at the highest levels of the Chinese government. Premier Wen Jiaobao summarized the grim challenges facing China: as of 2006, one-third of China was affected by acid rain, 90 percent of natural grasslands have deteriorated, and 1.74 million square kilometers had become desertified.[26] Despite a rising GDP, Cheng Siwei, former vice chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress, conceded in 2010 that the country has “paid heavy costs for all the environmental pollution, wasted resources and ecological deterioration.”[27]

In an effort to address environmental degradation, the Chinese government has committed to what it calls “sustainably developed GDP”[28] and has implemented plans to slow the growth of greenhouse gases.[29] In expanding its environmental agenda, the government has rigorously developed and encouraged the use of green technologies.[30] Yet despite the pledge to adopt greener policies and technologies, China still faces an enormous task in protecting health and cleaning up pollution sites while employing sustainable practices and technologies.

The Chinese government has also fined or shut down companies that operate illegally. According to government statistics, a total of 2,183 heavy metal companies were punished for illegal operations in 2009,[31] and an additional 231 companies were shut down. In November 2010, the Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP) issued a list of enterprises which violated national safety standards through unsafe heavy metal storage and disposal procedures, and the list typifies the kinds of violations which commonly occur among heavy-metal-related enterprises. Among these companies, illegal operations generally involved improper management and storage of hazardous waste, such as lead-containing slag, failure to implement preventative measures for the seepage of arsenic-containing residue into the environment, and failure to adhere to environmental impact assessments, such as the improper disposal of lead-containing sludge through rainwater channels.[32] In rare instances, owners of hazardous factories may face criminal charges.[33] However, liability for contaminated industrial sites is frequently disputed, with neither current nor former owners consistently held responsible. Even when hazardous facilities are shut down in response to environmental concerns, they may be re-opened with no changes in operation procedures.[34]

In addition to large industrial facilities, small-scale heavy metal enterprises can pose a serious threat to the eco-system and public health.[35] The township and village enterprise (TVE) sector, comprised of small-scale, private factories, emits 60 percent of China’s air and water pollution and employs more than 130 million rural workers.[36] The TVE sector encompasses over 20 million small-scale factories scattered throughout the Chinese countryside, making these enterprises difficult to monitor and regulate.[37] The TVE sector is less likely to use environmental mitigation technologies since they often lack access to significant capital. Although national regulations have successfully closed some of the worst environmental offenders, the TVE sector remains a major threat to the environment and public health.[38]

A study by the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Agriculture surveyed the TVE sector in 30 sample counties in 15 provinces.[39] Industries surveyed included textiles, chemical production, metal processing, construction material production, plastics manufacturing, coal mining, and electronic equipment production. It found that there was at least one occupational hazard to worker safety in 83 percent of the workplaces surveyed. Within the chemical industry, the study noted that 1,473 out of 1,553 enterprises had occupational risks, and in the electronic communication equipment manufacturing industry 414 out of 548 enterprises were also found to have occupational hazards.[40] The study concluded that approximately one-third of all employees were exposed to those hazards.[41]

In response to increasing cases of heavy metal pollution, the Ministry of Environmental Protection[42] in August 2009 approved a draft of the Implementation Plan for the Comprehensive Handling of Heavy Metal Pollution, which set out to strengthen the regulatory system for heavy metal pollutants, bolster industrial structure reform, and establish an inspection and supervision system for the prevention of pollution.[43] The MEP also announced a three-month nationwide campaign that would investigate enterprises which handle significant amounts of heavy metals.[44] Locally, some municipal governments have been reported to offer free lead blood tests for children under 14 in response to the outcry over heavy metal pollution cases.[45]

Lead Poisoning in China

Elevated lead levels damage the brain, kidneys, and blood cells, which may result in anemia, deficits in IQ, high blood pressure, coma, or death.[46] However, the range of manifestations of lead poisoning may also mean that it can go unrecognized or confused with other disorders.[47] While the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines lead poisoning as any blood lead concentrations over 10 micrograms per deciliter, the World Health Organization considers lead in the blood unsafe at any level.[48] Researchers have suggested that there is no blood lead level in which there are not cognitive effects, and each microgram per deciliter of blood lead concentration can be associated with a reduction in IQ of 0.25 points.[49]

Childhood lead poisoning is among the most common pediatric health problems in China.[50]Pregnant women and children are particularly vulnerable to lead poisoning. In pregnant women, lead poisoning can cause premature birth, low birth weight, or damage the fetus.[51] Children are especially at risk for lead poisoning because they tend to absorb up to 50 percent of lead they are exposed to, compared to 10-15 percent for adults.[52] Lead affects the development of a child’s nervous and digestive system, and virtually every organ in children is susceptible to damage from lead poisoning.[53] The propensity of infants and young children to explore the world through their mouths or play in what may be lead contaminated areas, increases their likelihood of ingesting or inhaling lead in dust and dirt.[54]

In China, lead exposure may occur through a variety of sources such as lead-polluted air, paint, water, food, lead-painted toys, and stationery.[55] Determining the overall extent of lead poisoning in China is difficult due to a lack of comprehensive data, but an increasing number of sources including academic and media reports suggest that lead poisoning is becoming a public health emergency, especially in heavy industrial areas. In a study published in 2004 of the blood lead levels of children in rural communities in Zhejiang province, the average blood lead level was 9.5 μg/dL; children whose parents worked in potentially lead contaminated sites had BLLs greater than 10 μg/dL.[56] A review of reports regarding lead poisoning in the Chinese medical literature between 1990 and 2005 found that the 2002 Occupational Diseases Prevention and Control Act had limited impact on either lead exposure or lead poisoning in China.[57]

Even in non-industrial areas located away from heavy metal facilities, people were still found to have elevated blood lead levels. In 2004 in Chengdu, located in Sichuan province, 938 children under seven-years-old were tested for elevated blood lead levels; the average BLL was 6.4 μg/dL.[58] The studies concluded that using formula rather than breast milk and living on the ground floor, in one story houses, or near the street were all considered major risk factors in exacerbating lead exposure.[59]

In an attempt to provide an overall picture of the distribution of blood lead levels among children in China, researchers from the Peking University Health Science Center reviewed articles regarding children’s BLLs from 1994 to 2004. The study looked specifically at children living in sites far from industrial sources of lead pollution and found a BLL average of 9.3 μg/dL; 34 percent of subjects possessed BLLs greater than 10 μg/dL.[60] Children in Shaanxi were found to have the highest average BLL and highest prevalence of BLLs over 10 μg/dL (70.6 percent). After Shaanxi, provinces with the highest averages included Henan and Sichuan, following by Gansu, Hainan, Lioaning, Jilin, and Yunnan. Despite these cases of elevated blood levels in non-industrial and urban areas, China has not yet established a routine national blood lead surveillance system.

Social Unrest Due to Environmental Hazards at Home and in the Workplace

Chinese residents are increasingly participating in public protests, which the government refers to as “mass incidents”.[61] Protests over pollution and occupational health and labor disputes are increasingly accounting for many of the more than 100,000 mass protests occurring each year in China.

As reported by Chinese media, the MEP acknowledged that in Shaanxi province alone in 2009, there were 32 public disturbances (起群体性事件).[62] In addition, an average of 10 air and water contamination accidents nationally was reported per month in 2010.[63] Environmental protests are largely in rural areas, and many are either quickly suppressed or censored. Any news of these incidents often emerges days or weeks later.[64]

For instance in 2005, thousands of people rioted in the village of Huaxi in Zhejiang province after police officers attempted to stop elderly villagers from protesting the poor air quality and contaminated farmland due to a nearby factory’s pollution.[65] Although the government temporarily suspended the factory’s operation after several weeks of protesting, villagers reported that the government eventually sent over 3,000 police officers in response to disperse the elderly women who continued to protest and the village erupted in violence. According to a local resident, the village had already sent representatives to file complaints at the government petition offices in Zhejiang province and Beijing over the course of two years, with “no results.”[66]

Although environment-related protests largely occur in rural areas, growing social unrest caused by environmental concerns has also risen among city dwellers and the middle class.[67] In 2009 more than one thousand people protested the construction of a rubbish incinerator in a district in Guangzhou province.[68] In 2008 hundreds in Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan province, protested against the construction of an ethylene and oil refinery in a neighboring city. Over 400 residents took part in the peaceful demonstration against the joint project between the Sichuan provincial government and PetroChina, a publicly traded subsidiary of the country’s main oil producer.[69] In interviews, critics of the joint venture stated that the government had failed to perform proper environmental assessments and hold public hearings on the project.[70]

In China the number of labor disputes due to occupational health hazards has also risen dramatically with a 16-fold increase from 1994 to 2006. Between 2004 and 2005, the number of labor-related protests rose from 87,000 to 127,000.[71] In an effort to address occupational health hazards, the central government has launched investigations into workplace health and safety. During a nationwide campaign in 2002, authorities probed more than 48,000 enterprises and found that almost one quarter had violated laws on labor safety and occupational disease control.[72] The Chinese government subsequently shut down or suspended production in more than 12,000 enterprises that failed to protect employees from toxic working conditions.[73]

Access to Information and Environmental Protection

In an effort to ease public fears about industrial pollution, China has instituted legislation that calls for increased transparency of environmental pollution issues. In 2008 China passed the Environmental Information Measures, a law which requires environmental protection departments to disclose information such as environmental statistics, environmental investigative information, the allocation of total emission quotas of major pollutants and their implementation, the issuance of pollutant emission permits and importantly, lists of heavily polluting enterprises, enterprises that have caused serious environmental pollution accidents, and enterprises that refuse to enforce environmental administrative penalty decisions.[74] Article 5 of the law explicitly states that citizens have the right to request environmental information from government departments as well.[75] However, a recent survey performed by the US-based National Resource Defense Council and the Institute of Public & Environmental Affairs, a Chinese research institute, found that average compliance levels remained low despite the recent passage of the Environmental Information Measures.[76] Of the 113 municipal environmental protection departments that were tested, only five were recognized for meeting information disclosure requirements.

In addition to the Environmental Information Measures, the Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on Open Government Information legally obligate local governments to disclose information that is “vital” to public interest. Articles 9-12 state that governments must disclose any information that “involves the vital interests of citizens, legal persons or other organizations” or is related to “important and major matters in urban and rural construction and management.”[77] Article 5 further states, “Citizens, legal persons and other organizations may request environmental protection departments to obtain government environmental information.”[78]

Despite these laws, the public continues to be blocked from accessing public information. For example, during the Heilongjiang Provincial government’s 2009 environmental emergency management work meeting, media outlets were invited to observe proceedings. However, as two journalists from Xinhua, the Chinese state media outlet, attempted to photograph internal documents listing polluting enterprises, a local official stopped them, saying that the information was “confidential.” He added that the current public information was “enough,” despite the fact that China’s transparency laws require environmental departments to disclose the information. Xinhua later ran an article asking, “How can it be that information meant to be disclosed and publicly supervised is kept confidential from the media and the public? Especially information regarding enterprises’ illegal discharge of pollutants – how can this ‘confidentiality’ protect the people’s right to know and right to supervise?”[79]

II. Findings

I’m very worried about my son’s health, I’m very worried about my son’s future, but what can I do? The government ignores us.[80]

—Su, father of a nine-year-old boy with lead poisoning, Henan province, 2010

The villages that Human Rights Watch visited are mostly in rural areas, with villagers relying primarily on small scale agriculture for their livelihood. In one area of Hunan where Human Rights Watch carried out research, the manganese smelting factory that villagers believe is the cause of elevated blood lead levels is situated in the center of several villages. The surrounding areas are large tracts of land for farming. In Shaanxi, the factory rises up over multiple villages, with some homes bordering the factory. In Yunnan, there are small factories dotting the hillside as far as the eye can see with villages all around, on the side of the hill and in the valley. In Henan, where the area is more industrial, the lead factories are situated next to clusters of villages and near schools. All of these areas are poor and the factories are an important source of income for the villages.

In the area of Henan we visited, there are three large lead smelting factories that were in full operation. There are also dozens of smaller factories that we were told had been temporarily shut down because of pollution violations. In Hunan, the main factory in the area we visited was a manganese smelting factory; in Shaanxi it was a zinc and lead smelter. In Yunnan there were dozens of small factories of different types.

Although most of these factories are privately owned, many are connected to the local government in some way, which could present a conflict of interest. In Hunan, for example, the legal representative of the manganese smelter is also a city government official,[81] serving on the National People’s Congress for Hunan province.[82] In Henan one lead smelter is state-owned, while another, which is privately owned, has top local officials on its board, including the chairman of the City People’s Congress.[83] In Shaanxi, local government officials were instrumental in securing the construction of the lead and zinc smelter, even orchestrating forced evictions to ensure that there was a place for the factory to be built.[84]

In each province, the people we spoke with had common complaints: parents and grandparents caring for sick children told us that local governments had given them little or no information on lead poisoning, or they had denied its scope and severity, and had intimidated parents and journalists so they would not call for attention to be paid to their children and demand accountability for those responsible.

Human Rights Watch heard how children are turned away from hospitals, are denied access to testing for blood lead levels, and how test results are withheld or unreliable. Despite strong Chinese environmental laws, Human Rights Watch was told that polluting factories are rarely shut down, and when they are, they often quickly re-open with no apparent change in their operations. Human Rights Watch was told that local police and government officials harass and intimidate, and even arrest, many of those who complain, and when journalists investigate these issues they are told that access to highly contaminated regions is restricted. When Human Rights Watch researchers spoke with government officials in two provinces, we were also told that these areas are off-limits.

Testing Practices

I want to know how sick my son is, but I can’t trust the local test results.

—Dan, mother of a three-year-old with lead poisoning, Hunan province, 2010[85]

In each area visited in Henan, Shaanxi, Hunan, and Yunnan the local governments provided free testing for lead poisoning to children under the age of 14 who local authorities designated to be at high risk for lead poisoning.[86] Testing took place at local hospitals and local Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention clinics.[87] However, according to all the parents we spoke with, families in these high-risk areas were not informed by medical or government workers that the testing sites had been set up; rather people found out about the testing by word of mouth.

Restricted Testing

Evaluating a population’s exposure to lead is an extremely complex process as there are numerous pathways for lead exposure, including via air, water, food, and soil, and the harm that lead in environmental sources can cause is dependent on more than just the concentration of lead. While the exact risk of exposure cannot be precisely measured, the best estimates require monitoring of both blood lead levels and environmental sources of lead and take into consideration factors other than distance from a polluting source.[88] The Chinese government’s designation of testing areas, such as one kilometer from the largest smokestack, are arbitrary and do not reflect the actual area of risk.

Although blood lead testing was available in Henan, Shaanxi, Hunan, and Yunnan, parents and grandparents reported that local government officials had placed arbitrary restrictions, beyond age restraints, on who could be tested. In Henan, the local government mandated that only children from villages that are within one kilometer of the largest smokestack in the nearest factory could be tested.[89] Children who did not fall within these areas were unable to access the free government testing, and in many cases they were prevented from being tested at all, even if the parents were willing to pay for the testing themselves.

One woman, Yan, explained:

Officially our village is four kilometers from the factory but I had heard that some neighbors had found out that their children had lead poisoning. I went to the testing center but the government said they wouldn’t test my son because our village is not within one kilometer of the factory. I brought a complaint to the Office of Letters and Visits but they said the rule is that they will only test people within one kilometer.[90] I took my son to a different city to get tested and his lead level was 32.9μg/dL.[91]

A man, Liu, from a different village in Henan, where palpable heavy pollution made the air thick and hard to breathe told Human Rights Watch:

Our village is not within the government’s one kilometer line, but when it turned out that children in other villages had lead poisoning we wanted to find out if our children also had lead poisoning. There were 56 children in total who needed to get testing. About half of them went, this was early on, and almost all of them showed serious lead poisoning. But then when we wanted to bring in the second group the government wouldn’t test them. They kept making up excuses, like the testing machines were broken. When my son got tested in a different city his level was over 40 μg/dL. All the children who got tested in the second group had lead poisoning and really high lead levels.[92]

Several people from different villages in Henan explained that at the beginning of the local lead poisoning epidemic, children who lived outside of the one kilometer zone could be tested, but according to several accounts, the local government started adding more restrictions and the local hospital began refusing to test people as the extent of the lead poisoning became clear.

A man named Su in Henan told us:

We don’t live in the one kilometer zone, but my son was very sick so the doctor suggested a lead test. I had to pay for it myself, and his result was high, 35.6 μg/dL. This was early on, and we’re lucky because now the hospital won’t do tests for children who live outside the one kilometer mark, even if the parents pay out of pocket.[93]

One woman, in Henan, whose six-year-old child had a lead level of 20 μg/dL explained:

At the beginning, some children in this village had free tests. But then as other people heard about lead poisoning and wanted to have their children tested, it wasn’t free anymore. Now it’s hard to have your child tested at all.[94]

In Shaanxi, where heavy pollution extends far beyond the government’s designated lead-testing area, parents told Human Rights Watch that only children in the villages right next to the factory could be tested. According to one grandmother, “the way the government is doing testing is excluding many children who need help.”[95]

Both the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which China ratified in 1992, and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), which China ratified in 2001, guarantee the right to the highest attainable standard of health.[96] The UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), which oversees states compliance with the ICESCR clarified in its General Comment 14 on the Right to Health, that states are obligated to “[refrain] from denying or limiting equal access for all persons….to preventative…and curative health…”[97] The CESCR has also clarified that a core obligation of the right to health is: “To provide education and access to information concerning the main health problems in the community, including methods of preventing and controlling them.”[98] The government’s refusal to provide access to testing for all children affected by lead poisoning constitutes a violation of the right to health.

Withholding of Test Results

Even parents who were able to access testing for their children reported difficulties in obtaining the results of the tests conducted. Many parents in Yunnan and Shaanxi reported that test results from their children’s lead tests were withheld completely. Some parents in Yunnan and Shaanxi told Human Rights Watch that they never saw any test results. Others were allowed to see the results from initial testing but were prevented from seeing the results from follow-up testing.

Several of the parents Human Rights Watch spoke to in Yunnan said that medical workers told them that their child had a slightly elevated level and that the parents should give them extra milk and vegetables. Those parents told Human Rights Watch that attempts to get the actual results from medical workers were refused.

In Yunnan one woman explained:

All of the children in this village got free testing paid for by the government. The doctor told us that that some of the results were a little bit higher than normal and they should drink more milk. They wouldn’t give us the results; they just told us to give the children milk.[99]

Parents in Yunnan reported they were told that follow up tests were “normal” although they were never allowed to see the result themselves. One mother told us:

The doctor told us all the children in this village have lead poisoning. Then they told us a few months later that all the children are healthy. They wouldn’t let us see the results from the tests though.[100]

According to a grandmother named Bao who Human Rights Watch spoke to in Shaanxi, attempts to access the results of her four-year-old granddaughter’s follow-up lead test were unsuccessful. She said:

Her first test, done at the hospital in our local town was 18 μg/dL. We went back for another test, which we had to pay for ourselves. The doctor said her results were fine. We didn’t believe him so we asked to see the results but he wouldn’t give them and just said the results were fine. We don’t have any power to force him to give them to us so we don’t know what her true result is now.[101]

A man, Dong, who lives in Shaanxi across the street from the smelter, told Human Rights Watch:

The first time my grandson got tested his result was 30 μg/dL. When he had a second test a few weeks later the doctors said he was normal. We didn’t believe that could be right, so we brought him in a third time and they still said it was normal. But they refused to let us see the actual results.[102]

An international NGO working on environmental issues in China told Human Rights Watch that the local CCDC clinics did blood lead testing on communities across China without informing people that they were doing lead tests. According to this NGO, the CCDC clinics did not tell people even when the tests showed that people had lead poisoning.[103]

A professor at a Chinese university who works closely on these issues suggested that the reason the CCDC does not inform people of their results is because they do not have the infrastructure to treat everyone with lead poisoning, and they also do not have the resources to relocate the families who are living in a toxic environment.[104]

Discrepancies in Test Results

In villages in Henan, Yunnan, Hunan, and Shaanxi, parents told Human Rights Watch they are afraid the blood lead test results provided by health workers are incorrect. In a number of cases, those parents had their child tested again by a hospital or a CCDC clinic in a different area. In each case reported to Human Rights Watch, the second test revealed far higher levels of lead in the blood, and parents were gravely concerned that the first test result had been deliberately altered and falsified so that it seemed as if the child’s health was either not at risk or at lower levels of risk.

In Henan, parents told us that at first when the government started testing children in 2009 all the children had very high levels. After a few months, in which there had been consistent results of high blood lead levels indicating that lead poisoning was a big problem in the area, children being tested for the first time started to receive test results indicating much lower levels. This was despite the fact that the factories were still operating as normal and there had been no other changes to the environment or treatment offered to the children. According to parents in Henan and Shaanxi, authorities offered no explanation for the suddenly lower level results. According to many parents we spoke to, suspicion about false results led parents to bring their children to towns outside the contaminated area for testing. In every case these results were much higher than the results that the local hospital or CCDC clinic had provided.

In Henan, a father tearfully described the experience of his daughter, Rong, who was 10-years-old when she was tested for lead poisoning. According to his account, Rong received government sponsored free testing. He went on to say:

She was very thin and not eating and had trouble sleeping. When she got tested her level was over the normal limit, but it wasn’t very high. It was 14.8 μg/dL. We didn’t think that test result could be right, and we had heard of other children being given results that were false, so we took her to another place to be tested. The result of the second test was 25.4 μg/dL. These tests were on the same day! The government doesn’t want to have to give us anything so they make up the results.[105]

A mother told Human Rights Watch about her son who is four-years-old and had been losing weight and frequently had a fever. She said:

He had been feeling sick for a long time and we didn’t know what was wrong with him. In August, when a lot of children were having tests for lead poisoning we took him to the doctor to do the test. His result was 8 μg/dL. In September we took him to a different town to do another lead test. His result was 22 μg/dL.[106]

The parents of a five-year-old girl, Peng told Human Rights Watch that their daughter had been tested for lead poisoning at the local CCDC clinic in September 2009. They were very worried about her health and thought the result of her lead test, which was 15.2 μg/dL, was not right. According to her parents, Peng had not been eating, had lost a significant amount of weight and frequently had fevers. Her father told Human Rights Watch:

We want to take her to the doctor, we want her to have another test, we want her to get better. But we don’t have any money to pay for the test or the doctor. We’re very worried about her, but what can we do?[107]

The mother of a 10-year-old girl from Henan province had a similar experience. At the local CCDC clinic where Xuxu had the government-sponsored test, her result was 25.5 μg/dL. Her mother said:

My daughter is not well. She is really skinny, she doesn’t eat and she doesn’t study well. I took her to the doctor in a different town a few weeks later and they did another lead test. Her result was over 40 μg/dL.[108]

Wei, the mother of a five-year old girl, said:

We are really worried about our daughter. They said the result of her lead test was 16 μg/dL but we don’t believe it. She doesn’t eat, her stomach hurts all the time and she gets fevers easily. We don’t have any money to take her to the doctor.[109]

Purposely withholding tests results violates the right to health. Any efforts to manipulate test outcomes, to alter, or to deliberately falsify test results would be an even more egregious violation. At a minimum as a matter of basic accountability, when there is an inexplicable change in the outcome of testing that has direct health implications, not attributable to an identifiable change of circumstance or specific intervention, the authorities should provide a plausible explanation for the difference. The CESCR specifically states that “the deliberate withholding or misrepresentation of information vital to health protection or treatment” is a violation of the right to health.[110]

Access to Medical Treatment

My children are sick but we didn’t get any medicine. ‘Just drink milk,’ they tell us.

—Peng, mother of a boy with lead poisoning, Henan, 2010[111]

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention lays out guidelines for the treatment of children with elevated blood lead levels. According to these guidelines, when the blood lead level is 10 μg/dL and above, the nutritional and environmental interventions should include reducing the lead hazard and eating foods with calcium and iron. For children who have blood lead levels persistently between 15 μg/dL and 44 μg/dL, the CDC also recommends extensive lab work, lead hazard reduction, neurodevelopment monitoring, environmental investigation and follow-up blood monitoring. For levels above 44 μg/dL, it additionally suggests chelation therapy, a process usually requiring a lengthy hospitalization when a medication is taken that binds to the lead, which is removed from the body in urine. The CDC stresses the necessity of medical supervision and follow-up testing in all interventions.[112]

In Shaanxi, Hunan, Henan, and Yunnan provinces, there is no standardized treatment for lead poisoning. There was widespread confusion among all parents we interviewed about what kind of treatment, if any, is appropriate for lead poisoning.

There is also confusion at the national level. National Ministry of Health guidelines for lead poisoning state that only children under six in higher risk areas should be tested, since, according their guidelines, the number of children in China with levels of 20 μg/dL or higher has decreased in recent years.[113] Not only does this claim run counter to indications that lead poisoning is on the rise in China, the Ministry of Health defines unsafe levels of lead in children at 10 μg/dL and above, not 20 μg/dL or higher. The World Health Organization also identifies a lead level of 10 μg/dL and above as detrimental to physical and mental health.[114] At that level the CDC recommends environmental and nutritional interventions.[115]

Provision of Inappropriate, Inadequate, and Inconsistent Treatment

The most common response we received when we asked about treatment was that parents were told to give their children more of any number of food items. According to parents in Shaanxi, medical workers and government officials told them to give their children apples and garlic.[116] In Henan and Yunnan, parents told Human Rights Watch that they were instructed to give their children milk.[117] However, even the provision of this nutritional treatment was not applied consistently. In no interviews with parents or children did we find the treatment they said their children had received for lead poisoning to be consistent with international standards and best practices.

A small number of parents told us that their children had been given some medicine, although it was unclear what medicine had been administered. While exposure was constant, almost always these “treatments” were sporadic.

A grandmother in Shaanxi, Zheng, whose grandson has lead poisoning, said:

The government gave us some garlic and told us to give our grandson extra garlic. We asked about medicine, something to make him better. They said they wouldn’t give us any because medicine for lead poisoning doesn’t work.[118]

In Shaanxi a grandfather showed us a box of medicine that local officials had given his grandson. He told Human Rights Watch:

We were given some medication by local officials to give to our grandson. We don’t know what it is but we had him take it for a month until the supply ran out and so he stopped taking it. Then a few months later they brought another box of it. We don’t know when or if they’ll bring more.[119]

In Henan, according to some parents we spoke to, only children under six-years-old were to receive any kind of treatment. Others said they did not understand the criteria that determined who received what or why the treatment would improve their children’s health condition.

A grandmother of two children with lead poisoning in Henan told Human Rights Watch that the local government had provided milk for her nine-year-old grandson, not for her one-year-old granddaughter. She said:

There was milk provided for my grandson but not my granddaughter. I don’t know why. I asked them but they didn’t have an answer.[120]

Parents in Henan told us that they did not know why they would get a box of milk one day and then not another for a long period of time, sometimes as long as three months. One father, Su, spoke of his experience trying to get treatment for his son:

My son has a high lead level and is sick all the time. The government is not giving us any help or medication. I went to see a doctor in Zhengzhou [the provincial capital] and he told me to get a certain medication, which I did. It’s really expensive, 1000 RMB ($150) for four months, and said my son should take it for a year. We really can’t afford it but we borrowed money and bought the medication. It has been four months and there is no change in my son’s health. I wish they would just close the factory.[121]

Some parents in Hunan and Henan told Human Rights Watch that their children had been hospitalized to be treated for lead poisoning.[122] According to guidelines put out by a local hospital in Henan, any child with a blood lead level over 25 μg/dL should be hospitalized.[123] However, the guidelines give no indication of what kind of treatment the hospitalized children will receive. In Henan we spoke to several parents whose children had been hospitalized. One woman told us:

First my daughter was tested and her result was 25 μg/dL. But then she was tested again and it was over 40 μg/dL. They told us to bring her to the hospital and we did. She stayed there for a week. They said they gave her medicine but we don’t know if they actually did or what kind of medicine they gave her. When she came home they told us to give her more milk but we don’t know why. She doesn’t seem any better.[124]

According to a father in Henan:

The local government told us that any children who had a blood lead level of over 40 would be hospitalized. They did not tell us what kind of treatment they would receive. My one-and-a-half-year-old had a high level so we brought her to the hospital. But there they did not give her any treatment and moved her to a hotel where there were other children with lead poisoning. We found out that a provincial level official came to town and our local officials wanted to hide these children! They kept them at the hotel for a month. My daughter was never given any treatment.[125]

The lack of clear information about lead poisoning and treatment caused some people not to seek help. A grandmother we spoke to in Henan who has a young granddaughter with a very high blood lead level told us:

A local official said my granddaughter should be taken to the hospital for treatment. But she wasn’t even one-year-old at that time and I was afraid of what they would do to her. The official didn’t explain to me what the treatment was so I didn’t bring her. They never came back to talk about it again.[126]

Some parents in Henan reported that local officials had told them to give their children nutritional supplements. Yet parents said they did not have the financial resources to provide these to their children on their own, nor were they clear about the purpose of the supplements.

In Shaanxi, Henan, and Yunnan, when Human Rights Watch conducted interviews, the factories, believed to be the cause of widespread lead poisoning, were continuing to operate, even while the local governments were dispensing “treatment.” In Hunan, the factory had been temporarily shut down, but parents were concerned that it was already operating at night and would re-open fully in the future.

Treatment guidelines for lead poisoning from the CDC and WHO specify that any treatment should be undertaken in a “lead-free environment,” and the CDC guidelines say that the “single most important factor in managing of childhood lead poisoning is reducing the child's exposure to lead.”[127] The CDC guidelines go on to say that, “Children should NEVER be discharged from the hospital UNTIL THEY CAN GO TO A LEAD-FREE ENVIRONMENT” (emphasis in original).[128]

According to experts from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: “there is no evidence that chelation can prevent adverse developmental and intellectual outcomes in children who continue to be exposed to very high environmental lead concentrations.[129] A team of specialists from Britain’s National Health Service confirm:

There is a risk that chronically poisoned children who receive chelation therapy then return to a high-lead environment soon afterwards while their blood lead concentrations are still high, could be at risk of acute lead toxicity.[130]

Chinese guidelines recommend chelation therapy at a blood lead level of 45 g/dL or higher. While Chinese national guidelines on lead poisoning treatment released by the Chinese Ministry of Health do not explicitly say that a child with lead poisoning should be removed from the area of contamination, they note the importance of identifying the source of the lead poisoning and say that no oral medication for lead poisoning should be taken while there is continued exposure.[131]

Denial of Treatment

One consequence of the denial of testing for lead poisoning, the withholding of test results, or the provision of inaccurate results, is the denial of treatment and financial compensation to children with acute lead poisoning.[132] Children and adults who were excluded from the official testing program because of age or geographic restrictions but who tested positive for lead poisoning in other cities were also refused treatment where they live.[133] While removing the lead hazard is the most critical step towards treatment, children who are still exposed to lead can benefit from certain nutritional supplements and other interventions.

In Henan, in cases where parents were denied treatment at the local hospital or CCDC clinic and took their children to other areas for testing, they reported that even when they showed the local government the results of the lead test, the government refused to give them the compensation offered to children within the one kilometer range. A mother, Yan, who took her son to a nearby town for testing after the local CCDC clinic refused to test him, told us:

The result of my son’s lead test was 32.9 g/dL.[134] We showed our local officials that our son’s lead level was way over the safe level and that he should receive extra food and compensation from the government like other children who were tested. But they refused to give us anything because we are not within one kilometer. We’ve gone to complain a few times but we won’t anymore. We are afraid to make the local officials angry. There is nothing we can do now for our son.[135]

A man, Liu, took two groups of children from the same village to be tested for lead poisoning. The first group was tested locally, but the second group was refused testing and Liu had to take them to a different town for testing. Liu told Human Rights Watch that the children in the first group who were tested locally and had lead poisoning received milk and a small amount of monetary compensation from the local government. The children in the second group, who were refused testing locally, were denied compensation when they brought evidence of their high blood levels to officials.[136]

The father of a ten-year-old girl, Rong, told Human Rights Watch how she had two lead tests on the same day, one at the local CCDC clinic and one in a town further away. The result from her free at the local CCDC clinic, 14.8 μg/dL was much lower than the one at nearby town, which was 25.4 μg/dL. Rong’s father explained:

To get compensation from the government or to receive free milk and garlic, a child had to have a lead level over 25 μg/dL. Even though her other test result was high, Rong’s free government test was under the 25 μg/dL mark, so she did not receive any milk and we did not receive any compensation.

A woman in Henan, whose one-and-a-half-year-old son had very high levels of lead, said that because they had not been within the official testing zone her son was refused treatment:

My son is in poor health. He doesn’t eat, he can’t sleep, and he gets sick really easily. He can’t talk at all and can’t walk. We know his development has been affected by the lead poisoning. We have not been given any lead poisoning medication or any other kinds of help. We haven’t gotten anything at all from the government.[137]

A mother in Henan told us that her son could not receive treatment because her family members are migrants and their residence permit is from a different part of the province. She said:

We are living within the one kilometer mark and my son got tested for free. His test was high, over 40 μg/dL. He’s sick, he doesn’t eat and he’s lost so much weight. But they wouldn’t give him any medicine because his residence permit is not from here.[138]

As a party to the ICESCR, China is obligated to ensure that access to health facilities is available on a non-discriminatory basis, including on the basis of social origin.[139] However, many of China’s domestic migrant workers who are employed in parts of the country other than the province of their residence permit are denied access to health care. This practice violates the Chinese government’s obligations to ensure non-discriminatory access to available health care.

Protection from Re-exposure

When Human Rights Watch visited Henan, Shaanxi, and Yunnan, the factories surrounding the villages were still in operation. In Hunan, although the factory in the middle of the villages had been officially closed, villagers told us they were suspicious that the factory was already operating at night. The majority of families we interviewed said they could not move away from the factories because they lacked the financial means to do so.[140] People were clearly angry that the factories had not been closed (or had been closed and then re-opened), but there was a lack of understanding about the extent to which staying in the polluted areas would continue to be harmful to their children, even if the children were on “treatment.”[141]

Human Rights Watch interviewed a grandmother in Henan, who lives close to a lead processing plant. Her grandchildren, who live with her, both have lead poisoning, the six-year-old granddaughter having a lead level over 30 μg/dL. The grandmother told us: “The government has given us milk but not any information about lead poisoning.”[142]

In Henan a father to a girl with lead poisoning told us:

The factory should be closed. We have lived here for years and the factory is newer. We are worried about our daughter but we have no ability to move. What can we do?[143]

A mother in Hunan, whose three-year-old has a lead level of over 30 μg/dL said:

My son is sick, always has a cold and a temperature, he doesn’t eat much anymore. He’s not taking any medicine. My only hope is that the factory will not re-open because there’s nothing I can do for his health. Maybe if he lives in a cleaner environment he will get better.[144]

In Henan, some children in villages where officials acknowledged the lead poisoning were moved to new schools, ostensibly away from the toxicity of their village. But parents told Human Rights Watch that the new schools were not safer. A grandfather said:

The new school is not safe! The only difference is that the government has not tested the children in this area so they can claim there is not a problem. But children from this area who already go to the school have been tested in other places and have high levels too. One child whose parents I know had a level of lead of over 30 μg/dL. How is that safe?[145]

Parents and grandparents were distraught over temporary relocation in Shaanxi as well, where the factory is still in operation. One parent told us:

Our children are bused to a school in the town, so that they are not going to school in the pollution. But they still live here, sleep here, and eat this food. And the factory has been re-opened and is still polluting everything. If the government really wanted to help our children they would shut the factory down.[146]

China’s Law for the Protection of Minors requires schools and departments of health to provide children with “the necessary hygienic and healthcare conditions and make efforts to prevent diseases.”[147] Moreover, the law stipulates that: “Schools, kindergartens and nurseries may not conduct education or teaching among minors in such school buildings or places or with such facilities as are dangerous to their personal safety or health.”[148]

The Convention on the Rights of the Child requires states to take appropriate measures to combat disease and malnutrition through the provision of “clean drinking water, taking into consideration the dangers and risks of environmental pollution.”[149]

Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that:

Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care…[150]

Article 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which obligates states to provide for the health of its citizens, also implicates the right to a healthy environment. The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has clarified that the right to health imposes on states:

The requirement to ensure an adequate supply of safe and potable water and basic sanitation; the prevention and reduction of the population’s exposure to harmful chemicals or other detrimental environmental conditions that directly or indirectly impact upon human health.[151]

Access to Information

Is it safe for my grandchildren to be living so near the lead factory?

—Xu, Grandmother of children with lead poisoning, Henan, 2010[152]

Withholding of Information

In Hunan, Henan, Shaanxi, and Yunnan, parents told Human Rights Watch that they found out that the local factories were polluting at toxic levels only when they realized that children were getting sick. Parents in each place told Human Rights Watch they received no information about the factories, the pollution, health risks associated with the pollution, including any risk of lead poisoning, or about the medical consequences of lead poisoning.

In addition to not being able to obtain test results for lead poisoning, parents in Hunan, Henan, Yunnan, and Shaanxi routinely told Human Rights Watch they had not received information about what lead poisoning is, its impact, or its treatment. Almost none of the parents and grandparents we interviewed had an understanding of what lead poisoning is. Although many of their children have blood lead levels that are considered dangerously high, neither the local health workers nor government officials had explained the health consequences of lead poisoning and how to prevent it.

In the shadow of a lead processing factory in Henan, Human Rights Watch spoke to the grandmother (who is the primary caretaker) of a one-year-old girl, who, at the age of nine-months, had a lead level of over 40 μg/dL. She said: