Summary

In May 2005, an Israeli military court convicted a soldier of "severe intentional harm" to a civilian and sentenced him to twenty months in prison. The soldier was charged with shooting an unarmed Palestinian man in the southern Gaza town of Rafah in October 2003. This was, as the Israeli daily Ha'aretz observed, "the harshest punishment imposed on an IDF [Israel Defense Forces] soldier in the four and a half years of fighting in the territories."[1]

That same month, on May 19, 2005, the IDF announced that it had opened a Military Police (mezah) investigation into the May 4 shooting deaths of two Palestinian teenagers in the West Bank town of Beit Lakia. The teenagers were among a large group that reportedly threw stones at bulldozers Israel was using to construct a metal and concrete barrier, or wall, in the West Bank.[2] The IDF had suspended the officer who opened fire the day after the incident. As one experienced journalist wrote, "Such a swift acknowledgement by the military of improper behavior in the fatal shooting of Palestinians is rare."[3]

It remains unclear if these two developments represent a change in IDF policies regarding unlawful use of force resulting in deaths and serious injury to Palestinian civilians. Those policies until now have been characterized by inaction and cover-up. Such a change would therefore be most welcome.

In recent months several high-profile killings have drawn Israeli and international attention to the army's failure to conduct thorough and impartial investigations where there is credible evidence of unlawful use of force against civilians-none more so than the October 5, 2004, incident in which Givati Brigade soldiers shot a thirteen-year-old Gaza schoolgirl. An internal IDF debriefing immediately after the incident found that the company commander had "not acted unethically."[4] Fellow soldiers then released a communications tape to the media showing that another soldier had warned the commander that the victim was "a little girl." The tape recorded the commander saying, "Anything that's mobile, that moves in the zone, even if it's a three-year-old, needs to be killed."[5] On the tape he also states that he "confirmed the kill" by firing at the girl's body at close range. The IDF responded by opening a Military Police investigation that yielded a five-count indictment against the commander, but the charges did not include murder or manslaughter.[6] The commander's trial was still ongoing as of this writing in early June 2005.[7]

Between September 29, 2000, and November 30, 2004, more than 1600 Palestinian civilians not involved in hostilities, including at least 500 children, were killed by Israeli security forces, and thousands more were seriously injured.[8] The IDF informed Human Rights Watch that as of May 10, 2004, it had criminally investigated just seventy-four alleged cases of unlawful use of lethal force, less than 5 percent of the civilian deaths in nearly four years of what is commonly known as the al-Aqsa intifada, or uprising.[9]As of June 6, 2005, the IDF had not responded to a February 2005 request for updated information on indictments and convictions since its May 2004 communication.[10]

There are two situations in which the death or serious injury of civilians should be investigated. The first is in situations of armed conflict where there is prima-facie evidence or there are credible allegations of unlawful killings, or where all feasible precautions were not taken to protect civilians and other protected persons, resulting in preventable or unjustifiable civilian casualties. International humanitarian law (IHL) requires that armed forces distinguish at all times between combatants and non-combatants, and absolutely prohibits any deliberate killing of civilians. It also requires that armed forces observe the principles of military necessity and proportionality.

Independent and impartial investigations are also required when death or serious injury results from the use of lethal force under circumstances that do not constitute armed conflict. In this case, human rights principles and the standards related to the use of force in policing and law enforcement contexts apply. Almost all of the cases of death and serious injury investigated in this report occurred in circumstances that cannot fairly be characterized as situations of armed conflict.

In any military occupation, the line between armed hostilities and law enforcement can blur. However, both IHL and standards governing the use of lethal force in law enforcement were established with the explicit intent to provide protection for civilians. Therefore, where indications of armed conflict conditions are ambiguous, the government should investigate to ensure that civilians are receiving the protection to which they are entitled under both IHL and human rights law.

The recent investigations and prosecutions cited earlier notwithstanding, Human Rights Watch has found that Israeli military's investigative practices and procedures are not impartial, thorough, or timely. The military rarely has brought wrongdoers to justice, and existing practices have exerted little deterrent effect. In May 2004, for example, Zvi Koretzki was convicted for the negligent killing of sixteen-year-old Muhammad `Ali Zaid; he was demoted and sentenced to two months of imprisonment.[11] In contrast, the same court system handed down a sentence of six months to a defendant who had stolen a mobile phone, cigarette lighter and $500 cash. Conscientious objectors have been sentenced to twelve months in prison.

Apart from the Koretzki case, Human Rights Watch is aware of only one other conviction of an IDF soldier for negligent killing in the past four years:the February 2005 sentencing of a soldier for the shooting death of a Palestinian at a West Bank checkpoint. Human Rights Watch is also aware of two cases of convictions for inflicting "serious intentional harm" (including the October 2003 incident mentioned at the beginning of this report) and two convictions for unlawful use of a weapon that resulted in serious injury or death.[12] In no other case of which Human Rights Watch is aware has an IDF soldier been convicted of any criminal offense for killing or injuring a Palestinian.

At the heart of the problem is a system that relies on soldiers' own accounts as the threshold for determining whether serious investigation is warranted. Instead of initiating impartial investigations in such cases, the IDF relies on operational de-briefings, which Israeli officials have misleadingly referred to as "operational investigations," "field investigations," or "military investigations." The frequent discrepancies between IDF accounts of civilian deaths and injuries, on the one hand, and video, medical, and eyewitness evidence on the other hand, is the result in part of the IDF's practice of asking soldiers to "investigate" other soldiers from the same unit or command, without seeking and weighing testimony of external witnesses. Exculpatory claims of soldiers are taken at face value, at best delaying and at worst foreclosing a prompt and impartial investigation worthy of the name. So-called "operational investigations" may serve a useful military purpose, but they do not constitute proper investigations: they are wholly inadequate to determine whether there is evidence of a violation of human rights or humanitarian law, and they serve as a pretext for maintaining, incorrectly, that an investigation has taken place. Another critical weakness of this current system is the absence of victim involvement in the investigative process, and the demonstrated failure of the IDF to solicit or take seriously testimonies of victims or non-IDF witnesses as a basis for checking the reliability of soldiers' accounts.

This critique of the system and its flaws is nothing new. Different aspects of Israeli security forces' impunity in the OccupiedPalestinianTerritories have been aired in commissions and court cases, newspaper articles, and Knesset meetings for more than twenty years. Investigators rarely consult Palestinian witnesses, even though human rights groups and victims' families frequently present the Judge Advocate General's (JAG) office with directly relevant testimony from these witnesses. In the rare instances in which investigators recommended prosecution, the victims have tended to have foreign connections capable of producing external political pressure. The trial of the soldier who shot and killed Tom Hurndall, ongoing as of early June 2005, is a case in point (see below). When investigations do occur, deaths and injuries to Palestinians are treated less seriously than other infractions or violations, and differently from cases where those harmed by the IDF are Jewish Israelis.[13]

What is new is the mounting number of deaths and injuries of civilians that should, but do not, receive the serious investigation they deserve. All civilian deaths and injuries in the 1988-93 Palestinian uprising were investigated, although the quality of the investigations was often poor.[14] Following the outbreak of clashes in late September 2000, the IDF changed this policy, saying that deaths of civilians in the OccupiedPalestinianTerritories would no longer be routinely investigated because the situation was "approaching armed conflict" and that investigations would be limited to "exceptional cases." The IDF's explanation fails to take into account its obligation to investigate deaths and serious injuries of civilians where there is prima facie evidence or there are credible allegations of serious violations of international humanitarian law, or where deaths occur when lethal force is used in law enforcement rather than armed conflict circumstances.

Militaries investigate allegations of wrongdoing by their soldiers for reasons of self-interest, among other reasons. They do so because members of the armed forces must be accountable to their superiors in order to maintain operational efficiency, enforce discipline, and uphold the integrity of the armed forces. In a functioning democracy, the accountability of individuals entrusted with the use of lethal force is essential.

Armies, furthermore, are obliged under IHL to investigate and criminally punish those responsible for serious violations of the laws of war. Israel has ratified the Fourth Geneva Convention and has a duty to prevent war crimes and other violations of humanitarian law. In certain circumstances, IHL holds commanders criminally liable for the crimes committed by their subordinates.[15]

Israel's duty to investigate alleged wrongdoing by its soldiers is reinforced by its obligations under international human rights law. Israel has signed and ratified a number of treaties that oblige it to investigate violations and bring perpetrators to justice. These treaty obligations together form an effective deterrent against unlawful killings, torture, and other serious human rights abuses. These are the obligations to:

- Investigate serious human rights violations;

- bring to justice and discipline and punish those responsible;

- provide an effective remedy for the victims of human rights violations;

- provide fair and adequate compensation to the victims and their relatives; and

- establish the truth about what happened.

An "effective remedy" for a serious human rights violation requires a prompt, thorough, and effective investigation capable of determining whether criminal wrongdoing has occurred and, if so, identifying the person(s) responsible. An effective remedy also includes access by the victim or complainant to the investigatory procedure, and, when appropriate, the payment of compensation. Remedies must be effective in practice, not just in theory, with a strong enough element of public scrutiny to ensure true accountability. A key requirement is that those investigating an alleged crime must be effectively independent from those implicated in the events in question.

The Israeli military's system for investigating wrongdoing by Israeli soldiers fails all of these requirements. The system is opaque, cumbersome, and open to command pressure. Victims and their representatives have little practical access to the investigation process. Furthermore, it is not independent.As a result, only a handful of perpetrators have been brought to justice. The Knesset has passed legislation that effectively prevents almost all future compensation claims. The system does not provide justice or truth or meaningful reparation.

The most significant factor underlying impunity is the reluctance of the JAG's office to investigate incidents, even when witnesses are accessible and the breach of international law is clear. JAGs are able to receive complaints, or at their own initiative open a preliminary investigation in any case where, in their opinion, there is an offense that a military court is competent to address.[16]

The JAG's office has shown that there are some abuses that it will not tolerate, such as sexual violence, in which it has often quickly and effectively identified and located the perpetrators and brought proceedings against them. Action in these cases contrasted strongly with those involving death or serious injury of Palestinians, in which case the default response has been to whitewash or ignore possible abuses. Many such cases drop off the radar screen entirely. In two cases of severe beatings of Palestinians while in IDF custody detailed below, for instance, one of which resulted in the man's death, an IDF spokesman responded to Human Rights Watch inquiries saying, "The incident is unknown to us."

Another factor is the practical inability of most victims, i.e. Palestinians living in the OccupiedPalestinianTerritories, to initiate a complaint. When the IDF declines or refuses to investigate, there are no alternative forms of accountability. The West Bank and Gaza Strip are ruled under military law: Palestinians cannot seek prosecution of Israelis in Israeli military courts, or in the courts administered by the Palestinian Authority. In theory, victims or their representatives can appeal a decision not to indict to the JAG and, if unsuccessful, to the High Court of Israel. None of the families interviewed by Human Rights Watch were aware of this option, which in any case would be limited to those with the financial resources and connections to obtain Israeli representation. Under prevailing conditions of strict closure, which sharply restrict freedom of movement in the OccupiedPalestinianTerritories and between the territories and Israel, Palestinians find it extremely difficult to have physical access to Israeli institutions.

In many other countries, other institutions have the power to investigate human rights abuses. Unlike Mexico or Northern Ireland, Israel has no national human rights institution to receive complaints of human rights violations. Unlike Turkey, Colombia, or the Russian Federation, Israel is not subject to the jurisdiction of a regional human rights court. Israel's ongoing problems of military, security service, and police impunity will continue to fester until Israel chooses to strengthen its own accountability mechanisms.

The IDF has argued that investigating civilian deaths would harm the special nature of combat operations, and that only "exceptional" cases should be pursued, without indicating what the criteria would be. While it is true that not all deaths or injuries of civilians need trigger an independent investigation, the IDF's position cannot be reconciled with Israel's obligations under the international human rights and humanitarian law treaties that it has ratified. There are clearly established standards for determining whether particular actions have violated IHL in situations of armed conflict or constitute unlawful use of force in policing situations. The IDF should adhere to those standards.

The IDF has also maintained that armies elsewhere facing similar levels of hostilities do not carry out such investigations, sometimes citing U.S. practices in Iraq and Afghanistan, and has argued that the practical difficulties of investigating civilian deaths in the OccupiedPalestinianTerritories are simply too much for the system to bear.

In fact, the U.S. does not itself follow a "best practices" approach, with consequences in Iraq that are similar to those of Israel in the occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip.[17] There are, however, other positive examples. In the last fifteen years, countries such as Britain, Canada, and Belgium have reformed their military justice systems and introduced external accountability mechanisms. While those countries did not face armed conflict situations, their relevance should not be dismissed out of hand, because they do include, for instance, British military and police engagement in the Northern Ireland conflict.There is, moreover, an emerging consensus in international law that military justice should not be used to try military personnel in cases where civilians are victims, and that military justice systems should investigate only offences that are strictly military in nature.[18] The challenge for Israel is to ensure that its practices evolve to meet international standards and benefit from good practice elsewhere.

Apart from emerging standards, though, Israel's existing obligations are clear. If lethal force is used in situations of armed hostilities, Israeli forces must distinguish at all times between civilians and combatants, never direct attacks at a civilian population or individual civilians, and refrain from attacks that indiscriminately harm civilians. Israel has an obligation to conduct independent and impartial investigations in all cases involving prima facie evidence or credible allegations that troops violated these principles. When performing law enforcement functions, Israeli forces should be provided with the equipment and training necessary for this purpose and should not use firearms except when strictly necessary to defend themselves or others against the imminent threat of death or serious injury, and then only to the extent necessary to avert the actual danger faced. Curfew enforcement and control of demonstrations, for instance, should comply with law enforcement standards, and rules of engagement should be changed to reflect this. Deaths and serious injuries to civilians in these circumstances, when there is not a situation of active armed hostilities, should always be investigated. When the circumstances of a death or serious injury are unclear, the authorities should err on the side of investigating, with the objective of providing the greatest possible protection to the civilian population.

Conducting serious investigations can be difficult in circumstances of military occupation. Every Israeli official interviewed by Human Rights Watch emphasized the difficulty of obtaining witness testimony. Undoubtedly many witnesses are reluctant to cooperate with IDF investigations, for reasons ranging from fear of retribution to cynicism about the intentions and effectiveness of the investigators. Yet, as the cases reviewed in this report show, there are many cases in which IDF investigators simply do not attempt to contact witnesses to abuse, even when they are readily available.

There is much the Israeli authorities can do to improve the accountability of their armed forces for arbitrary killings and other serious human rights abuses against civilians. The government of Israel should:

- Establish an independent body to receive and investigate complaints of serious human rights abuses committed by IDF soldiers and the agents of the Israel Security Service (Shin Bet).

- Ensure that international norms are reflected in the operational and training manuals of the Military Police.

- Publicize widely information on how to file complaints, including in the Hebrew and Arabic media and on the internet.

- Ensure that when a complaint is not upheld after an investigation, the complainant is given a reasoned decision in writing, in his or her own language, which sets out the evidence as well as the investigative findings.

- Establish clear guidelines and procedures for all individuals involved in organizing and obtaining witness testimony of individuals residing in Area A, which is under Palestinian Authority jurisdiction[19]; and

- Compensate all individuals who have suffered harm as a result of unlawful or criminal behavior by state agents and amend current laws that make such compensation effectively inaccessible or unavailable to victims.[20]

These and other changes are practical, possible, and necessary if Israel wishes to develop a justice system that effectively counters the impunity now granted to its security forces.

Recommendations

To the Government of Israel

Use of Force

Under international law, Israeli forces in the OccupiedPalestinianTerritories are obliged to restore and ensure public order and safety, and respect and protect civilians. The means and manner of law enforcement and military operations must conform to the standards of international humanitarian and human rights law.

In law enforcement situations, Israeli military forces should abide by the standards set forth in the U.N. Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials and the U.N. Code of Conduct for Law Enforcement Officials, and be provided with the equipment and training necessary for this purpose. Israeli forces should not use firearms in law enforcement situations, except when strictly necessary to defend themselves or others against the imminent threat of death or serious injury, and only in proportion to the actual danger presented. Curfew enforcement and control of demonstrations should comply with law enforcement standards, and rules of engagement should be changed to reflect this.

If, in the context of law enforcement, lethal force is used, Israeli forces must comply with the principles of human rights law. These principles include:

- The exercise of restraint in the use of force, acting in proportion to the seriousness of the threat and the legitimate objective to be achieved.

- Ensure that assistance and medical aid are rendered to any injured or affected person at the earliest possible moment.

If, in the context of armed hostilities, lethal force is used, Israeli forces must comply with the principles of international humanitarian law. These principles include:

The obligation to distinguish, at all times, between civilians and combatants.

The prohibition against attacking the civilian population or individual civilians and their property.

The obligation to refrain from indiscriminate attacks.

The principle of proportionality namely, the military advantage of an attack cannot be outweighed by the impact on civilians or civilian objects.

Accountability

The government of Israel should:

Allocate sufficient resources to monitor civilian casualties throughout the occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip. Military authorities should keep records, and observe and analyze trends, related to specific units and commanders, as well as tactics, to ensure accountability and minimize civilian casualties. These statistics should be made public on a regular basis.

Maintain an official record of all complaints received against IDF personnel by date, location, alleged incident type, and action taken. Statistics regarding substantiated complaints and investigations should be made public on a regular basis. Statistics on all disciplinary proceedings taken by the IDF should be collected in sufficient detail and reviewed at a sufficiently high level to enable IDF authorities to identify patterns of wrongful behavior, and to adopt any necessary preventive or corrective measures. These statistics should be made public on a regular basis.

End the practice of relying on operational debriefings or "field investigations" into alleged civilian killings in determining whether to open criminal investigations.

End exclusive military jurisdiction over cases in which soldiers are accused of serious human rights abuses against civilians in non-combat circumstances.

Establish an independent body to receive and investigate complaints of human rights abuses and breaches of international humanitarian law committed by Israeli security personnel, including members of the IDF, the Border Guard, Israel National Police, and the Israel Security Service (Shin Bet). This independent body should have the capacity to initiate investigations of alleged wrongdoing on its own, and not simply in response to complaints. It should be staffed by competent, qualified, and impartial experts, who are functionally and practically independent of the suspected perpetrators and the agency they serve. The independent body should have sufficient personnel and adequate resources to carry out its responsibilities.

Provide the independent body with all information, as well as technical and financial resources, necessary to investigate fully all aspects of complaints, as well as to review patterns of abuse. Investigators should have unrestricted access to places of custody and the alleged incident, as well as to documents and persons it deems relevant. The independent investigative body should be empowered to summon witnesses and compel their testimony, and to demand the production of evidence and all relevant operational orders and related briefing materials. The body should have the ability to recommend for criminal prosecution any individual when credible evidence exists that the person has committed a crime.

Remove alleged perpetrators from active duty or from the areas where the incident under investigation took place while the investigation is underway.

Publicize widely information on how to file complaints, and contact details of investigating bodies, in the Hebrew and Arabic media, including media outlets in the occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip, and on the Internet. Complaint filing procedures should include a telephone hotline capable of receiving anonymous witness testimony. The process of registering a complaint should be straightforward, and persons making the complaint should be assured of confidentiality if they so request. All complaints for which evidence or credible allegations of wrongdoing exist should be investigated.

Bring to justice all individuals responsible for wrongdoing in a timely manner. Punishments should be commensurate with the gravity of the crime, including judicial as well as administrative penalties for all individuals guilty of unlawful killings, torture, or other serious violations of human rights and international humanitarian law.

Ensure that when a complaint is not upheld by an investigation, the complainant receives a decision in writing, in his or her own language, which sets out the evidence as well as the findings of the completed investigation. The investigation should establish a clearly auditable trail, one that demonstrates that a robust, impartial, and expeditious investigation took place and why the investigators reached the conclusions they did.

Establish clear guidelines to all individuals involved in organizing and obtaining witness testimony of individuals residing in areas under the jurisdiction of the Palestinian Authority and not normally under IDF control, including basic procedures on how to identify and search for witnesses or complainants, support services for witnesses or complainants, and appropriate interview and liaison techniques. Ensure these guidelines are shared with Palestinian District Coordination Office (DCO) officials responsible for facilitating Palestinian testimony. Clearly inform all witnesses and complainants of the procedures available to assist their giving of testimony, including the guarantee of non-arrest and facilitation of travel. Enable the use of video conference facilities for individuals unable to travel. Witnesses should be protected from intimidation and retaliation.

Ensure effective access by families and their legal representatives to any hearing and to all relevant investigatory information. Ensure that families can practically exercise the right to present other evidence.

Enable compensation of all individuals who have suffered harm as a result of unlawful or criminal behavior by state agents by taking the following steps:

Amend Sections 5 and 5A of the Civil Torts Law (State Liability), 5712 1952, to allow individuals who suffered harm as a result of unlawful or criminal behavior by state agents to receive compensation.

Create a compensation commission to expedite claim proceedings for all compensation awards under a reasonable monetary threshold.

Make all victims of unlawful or criminal behavior aware of their right to receive compensation, and of the means to obtain it.

Apply Article 77 of the 1977 Penal Code pertaining to personal liability of perpetrators and monetary compensation for victims.

Make applicable in the occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip, as well as in Israel, victims' rights provisions of the Offense Victims Rights Act (2001).

I. Introduction

Ruwaida al-Hajin and her two sons were killed by thousands of tiny, dart-like flechette rounds one Friday night in August 2002, during a summer holiday picnic. That same month Fatima Abu Dhahir was shot while sleeping in her front yard to avoid the heat. These and many other civilians are the faceless victims of lethal force used by the soldiers of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF). Their deaths may have resulted from the unlawful use of lethal force or simply be the unfortunate result of incidents of armed conflict. But no one will ever know precisely what happened, because their deaths were never impartially investigated.

The situation is different for Ahmad Abu `Aziz, a six-year-old who died in June 2002 when he went out to buy a bar of chocolate. His death, recorded on video, was investigated by the IDF, as were some seventy other cases. But because Israeli military investigations are shrouded in secrecy and the results rarely made public, no one can judge whether the investigations were impartial or if they had any result. The soldier alleged to have killed Ahmad along with his little brother and three other civilians is unlikely to stand trial. At the time of Human Rights Watch's inquiry, he had reportedly left the army and was traveling overseas.

It is the army's lack of accountability that has produced what a military court in 1989 termed this "bitter fruit."[21] This lack of accountability has reinforced the widely held belief that the Israeli army does not hold its forces responsible for the wrongful killing, injury, or ill-treatment of Palestinian or foreign civilians. Unlawful practices have gone uninvestigated and unchecked. With greater discipline and accountability on the part of Israeli forces, many civilians would not have been maimed or killed. And the lack of accountability is reflected in a surreal public relations war, in which the IDF first publishes inaccurate and self-serving accounts of victims' deaths and later claims moral victory on the very few occasions when it finally agrees to investigate them.

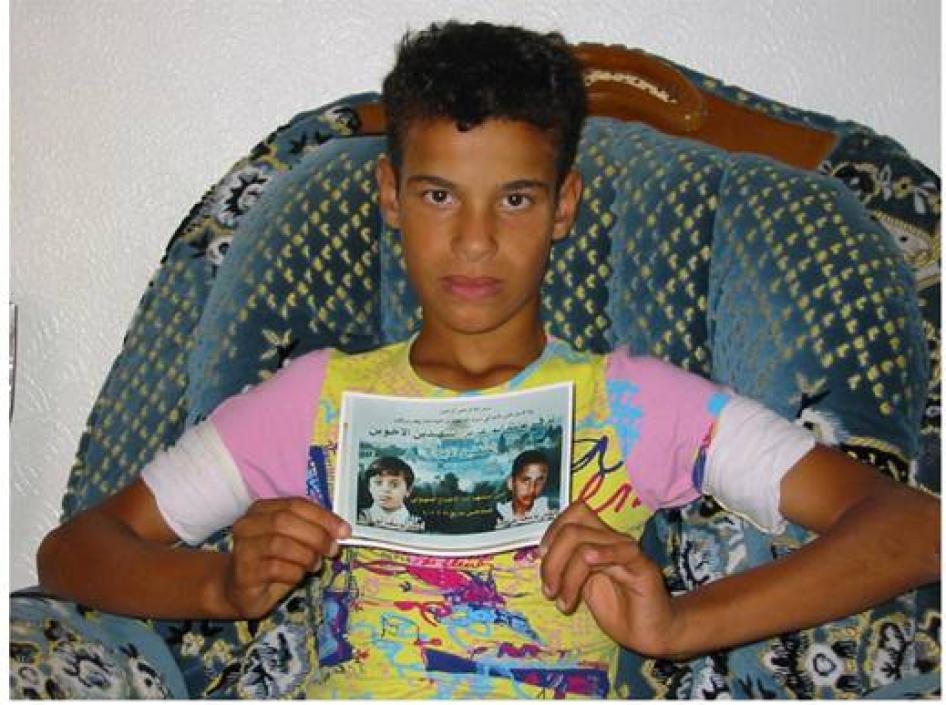

The brother of Ahmad and Jamil Abu-Aziz holds of a photo of his brothers, killed by IDF tank fire on June 21, 2002. An indictment was issued for a soldier for allegedly killing the two brothers and two others to enforce a curfew. According to media reports in January 2004, the soldier had left Israel.

2002 Miranda Sissons/Human Rights Watch

The public outcry in the several incidents in which the IDF has injured Israeli civilians illustrates how arguments against conducting proper investigations to some extent rest on the assumption that those injured or killed may be Palestinians but not Israeli Jews. The case of Gil Na'amati, who was shot in the knee by IDF soldiers while participating in an unarmed demonstration against the West Bank separation barrier on December 26, 2003, is illustrative: Na'amati, an Israeli citizen, had recently completed his military service in a combat unit. In the public outcry that followed, the IDF reportedly opened both a special investigation and a Military Police investigation into this shooting. Chief of Staff Moshe Ya'alon was quoted as saying, "The Israeli army is not given orders to shoot at Israeli demonstrators, but under the circumstances, one cannot blame the soldiers for having made a mistake." The soldiers, he said, "did not believe they were dealing with Israelis."[22]

As already noted, these problems are not new. Those Israeli soldiers who wrongfully kill or injure Palestinian civilians in the occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip have enjoyed effective impunity for decades.[23] Israeli public officials, human rights groups, journalists, and others have deplored this impunity at least since the formation of the Karp Commission in 1982.[24] The Karp Commission concluded, in May of that year, "The key lies not in the technical monitoring of the investigations, nor in criteria for investigative techniques, nor in the legal angle - but rather a radical reform of the basic concept of the rule of law in its broadest and most profound sense."[25]

Pressure for a proper investigation rises every time a high-profile killing takes place, but Israeli authorities have taken no serious steps to improve the accountability of the armed forces, create an independent investigation system, or reform the military justice system.

There is no reason this state of affairs should persist. Other armies have learned lessons from their own failures of accountability, by improving investigation procedures in these cases, transferring military cases to civilian jurisdiction, and revising their military justice laws. The IDF and its civilian authorities must do more to ensure that the IDF fulfills its duty to investigate impartially all suspicious civilian deaths and credible allegations of wrongdoing. It owes this duty to the civilians of the West Bank and Gaza Strip, whose lives depend on it. It owes this duty to its soldiers and officers, to protect them against unwarranted allegations of war crimes. And it owes this duty to the Israeli public, which has the right to expect a transparent, efficient, and accountable military that abides by international norms that the state of Israel has pledged to uphold.

About This Report

This report examines the Israeli army's failure to investigate adequately allegations of wrongdoing by Israeli soldiers since the outbreak of clashes in September 2000. It addresses three major questions. First, it examines how the army's policy on investigations has operated since September 2000, and the obstacles to accountability it has created. Second, it assesses the impact of "operational investigations," in which allegations of wrongdoing are "investigated" by the colleagues of the alleged perpetrator. These debriefings may be appropriate for learning operational lessons, but they in no way constitute impartial investigations into suspicious incidents. Third, it looks at how the Military Police investigations opened since September 2000 have been conducted - and what can be done to improve them.

This report is based on field research conducted from April to August 2003, previous Human Rights Watch fieldwork and reports, and additional research and interviews in 2005. It is based on more than 150 interviews with victims, families, military officials, nongovernmental organizations, and intergovernmental groups. It also draws from meetings and written correspondence with the IDF from 2001 to 2005, as well as public statements and legal submissions by government officials. Human Rights Watch particularly wishes to thank the staff of the International Organizations Unit of the Office of the IDF Spokesperson, who were considerably more responsive to our requests for meetings in 2003-2004 than in previous years.

During the course of its fieldwork in 2003, Human Rights Watch researched some thirty cases of alleged wrongdoing by members of the IDF. The majority of these cases were incidents that had taken place at least six to twelve months earlier, allowing sufficient time for an investigation to take place. Others took place during Human Rights Watch's period of fieldwork. Human Rights Watch in February 2005 requested from the IDF any update in the status of each case, and as of early June 2005 had received no response.

In selecting cases for examination, Human Rights Watch concentrated on those cases of alleged wrongdoing that the IDF had publicly committed to investigate. In the great majority of these cases, the killings very clearly happened outside a situation of armed conflict. Human Rights Watch also followed up cases that it had itself presented earlier to the IDF for investigation. For the sake of comparison, Human Rights Watch also documented a number of cases of alleged wrongdoing that appeared to merit investigation, but no mention of investigation had been made. Reasons of space do not allow us to discuss in the report every troubling case.

II. Why Investigate?

Investigations are essential to justice. Their quality and impartiality affect almost every aspect of disciplinary or judicial proceedings, from identification of the perpetrator to the strength of the evidence and the decision to indict or dismiss. Efficient investigative procedures and resort to an impartial judicial process are essential safeguards against abuse and impunity - and against the pain, terror, and suffering that they cause.

At the most basic level, armies investigate allegations of wrongdoing by their soldiers for reasons of self-interest. Members of the armed forces must remain accountable to their superiors in order to maintain operational efficiency, enforce discipline, and maintain respect for principles of international humanitarian law (IHL). In almost all armies, the procedures for military investigations and disciplinary or judicial proceedings were originally based on the need to punish service-related offences such as desertion, insubordination, theft, or mutiny. The more frequent the military operations, the more important it becomes that patterns of unlawful or negligent behavior are detected and stopped.

A further reason to investigate is to uphold the integrity of the armed forces, ensuring that ill-disciplined or unlawful acts by soldiers do not discredit the army or the country they defend and represent. The accountability of individuals entrusted with the use of lethal force is an essential part of any functioning democracy. Functioning democracies require that the military be accountable to the civilian authorities. The greater the role the military plays in the daily life of a country, the more important this accountability becomes.

Investigations are required to ensure respect for the laws that govern the use of force in armed conflict: international humanitarian law. The advantages of such respect are obvious. It minimizes the suffering caused by armed conflict. It encourages higher morale and a sense of professionalism within the armed forces, and prevents the commission of war crimes. It increases the likelihood of reciprocal behavior by other government or quasi-governmental parties, minimizing the possibility of a downward spiral in which each party attempts to inflict the most pain, cruelty, and suffering. Respect for IHL also helps ease post-conflict transition, by lessening the trauma and bitterness that develop when war crimes or crimes against humanity are committed. Lastly, efficient and impartial investigations can forestall pressures for international tribunals to take up serious violations of IHL on the grounds that the responsible government had failed to do so.

Investigations are similarly essential into incidents in which security forces use lethal force in policing and law enforcement circumstances. In situations where military authorities exercise police powers, their conduct is governed by the U.N. Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials and the U.N. Code of Conduct for Law Enforcement Officials. These international standards are clear: in policing situations, firearms should be used only when their use is "strictly unavoidable in order to protect life," and then only in proportion to the danger presented.[26] In order to ensure accountability for the possible wrongful use of force, it is important to carry out thorough, prompt, and impartial investigations into all incidents resulting in death or serious injury to determine that lethal force was used properly and, if it was not, to ensure that soldiers and commanders are held accountable for the wrongful deaths or injuries. The investigation should determine the cause and circumstance of the death or injury, who is responsible, and any patterns or practices that may have resulted in the violation of the rights of the victims.

Legal Obligations

Military forces also conduct investigations and discipline or punish wrongdoers because they have specific obligations under domestic and international law to uphold rights, prevent crimes, punish perpetrators, and ensure that victims have access to an effective remedy. Military forces are official state organs, with clear organizational hierarchies and enforceable chains of command. There are no excuses for non-accountability.

Israel has occupied the West Bank, Gaza Strip, East Jerusalem, and Golan Heights since 1967. New administrative structures were introduced in the Oslo process, but Israel continued to exercise substantial military authority throughout the West Bank and Gaza, as well as overall responsibility against external threats.[27] Since the redeployment of Israeli troops into Palestinian urban areas in early and mid 2002, Israeli forces have strengthened further their wide-reaching control over Palestinian daily life.

International Humanitarian Law

There are two overlapping bodies of international law that apply to Israel's conduct in the OccupiedPalestinianTerritories. The first is international humanitarian law (IHL). This includes principles of customary international law, the 1907 Hague Regulations annexed to the Convention (IV) Respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land, and the 1949 Fourth Geneva Convention Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War (Fourth Geneva Convention), which Israel has ratified.

The Hague Regulations are widely considered part of customary international law, and the Israeli authorities accept their applicability to the occupied territories. Article 43 of the Hague Regulations clearly states that the occupying power "shall take all the measures in his power to restore, and ensure, as far as possible, public order and safety" in the territory it occupies. In 1981, the Israeli High Court of Justice ruled that the Israel Defense Forces are obliged to investigate alleged wrongdoing by soldiers in the occupied territories as part of the authorities' obligation to maintain law and order.[28]

The duties of the occupying power, and the rights of the population under its authority, are set out further in the Fourth Geneva Convention. All protected persons shall be treated humanely and without discrimination.[29] This includes respecting family, honor, rights, the lives of persons, and private property. An occupying power is specifically prohibited from coercion, carrying out reprisals and imposing collective punishments. Violence to life and person, cruel treatment and torture, taking of hostages, and outrages upon personal dignity (including humiliating and degrading treatment) are absolutely prohibited "at any time and in any place whatsoever."[30]

The convention includes a mechanism to enforce the duty of humane treatment. It requires the occupying power to investigate and punish those responsible for serious violations of this duty. Article 146 requires the occupying power to investigate and prosecute "grave breaches" of the convention, defined in Article 147. It also requires the occupying power to provide effective penal sanctions for those who commit grave breaches, or those who order them to be committed. Article 147 defines grave breaches as, among other things, willful killing, torture or inhuman treatment, willfully causing great suffering or serious injury to body or health, as well as extensive property destruction "not justified by military necessity" and the taking of hostages.[31] Other breaches of the Geneva Conventions should also be investigated, prevented, and prosecuted.

When considering which legal standards apply to a particular situation, military and political leaders must distinguish between a legitimate military response in situations of armed confrontation, such as exchanges of fire between Israeli forces and Palestinian armed groups, and law enforcement and public security requirements. This is particularly the case in a situation of protracted military occupation.[32] Declaring a situation to be a "state of armed conflict" does not negate the obligation of the occupying power to apply law enforcement standards to maintain checkpoints, conduct raids on civilian homes and shops, or control civilian protests, even if some of these turn violent and require dispersal by soldiers or law enforcement officials.

Likewise, when a situation reaches a level of intensity that requires regulation by the laws of armed conflict, Israeli forces are obliged to observe customary international principles of military necessity, proportionality, and distinction. In essence, the primary goal of military necessity is to use the least amount of force needed to gain the submission of an enemy at the earliest possible moment.[33] Military necessity does not allow an armed force to take measures that violate the laws of war, or that do not have a military purpose. The rule of proportionality places a duty on combatants to choose means of attack that avoid or minimize damage to civilians. Intentional attacks against civilians are absolutely prohibited: the principle of distinction requires that combatants "shall at all times distinguish between the civilian population and combatants, and between civilian objects and military objectives, and accordingly shall direct their operations only against military objectives."[34] Attacks that are not aimed at military targets, (or, because of the method of attack used, cannot reliably be aimed at military targets) are indiscriminate and forbidden.[35] Combatants must take "all feasible precautions" to minimize incidental loss of civilian life, and to verify that the objectives to be targeted are not civilians or civilian objects.[36]

The Israeli authorities also have duties under customary international law to prevent war crimes and crimes against humanity. Those who commit or condone war crimes, such as the willful killing of civilians, are individually criminally responsible for their actions. In certain circumstances, IHL also holds commanders criminally liable for war crimes or crimes against humanity committed by their subordinates.[37] The responsibility of superiors for crimes committed by their subordinates is commonly known as command responsibility. Although the concept originated in military law, it is increasingly accepted that command responsibility includes the responsibility of civil authorities for abuses committed by persons under their direct authority.[38] The doctrine of command responsibility has been upheld in recent decisions by the international criminal tribunals for Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia, and is codified in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.[39]

There are two forms of command responsibility. The first is direct responsibility for orders that are unlawful, such as when a military commander orders rapes or intentional attacks on civilians. The second is imputed responsibility, when a superior fails to prevent or punish crimes committed by a subordinate acting on his or her own initiative. This kind of responsibility depends on whether the superior had actual or constructive notice of the subordinates' crimes, and was in a position to stop or punish them. If a commander had such notice and still failed to take appropriate measures to control his subordinates, to prevent their crimes, or to punish offenders, he can be held criminally responsible for their actions.[40] Israeli officials who are aware of willful killings or other grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions committed by their soldiers, but do not seek out or punish those responsible, may be held individually criminally liable for the actions of their subordinates.

International Human Rights Law

International humanitarian law applies to situations of belligerent occupation as well as situations where hostilities rise to the level of armed conflict. The application of IHL does not pre-empt the application of international human rights law - particularly non-derogable rights such as the right to life. In situations as complex as Israel's long-term occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip, both legal regimes complement and reinforce each other. The two bodies of law share similar normative frameworks, areas of common content, and many instances of overlapping protections. The application of both regimes also ensures that no individual, regardless of nationality or participation in combat, is left without some form of humanitarian protection.[41]

Israel has signed and ratified numerous human rights treaties, but argues that its resulting obligations do not apply to the OccupiedPalestinianTerritories. This position has been rejected by the relevant U.N. treaty bodies responsible for monitoring Israel's compliance with its treaty commitments. Most recently, in August 2003, the U.N. Human Rights Committee, composed of individual experts who examine the compliance of states with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), stated that:

in the current circumstances, the provisions of the [ICCPR] apply to the benefit of the population of the OccupiedTerritories, for all conduct by [Israeli] authorities or agents in those territories that affect the enjoyment of rights enshrined in the Covenant and fall within the ambit of State responsibility of Israel under the principles of public international law.[42]

Israel's duty to investigate is thus reinforced by its obligations under international human rights law. Israel has ratified at least five treaties that oblige it to investigate violations, bring perpetrators to justice, and to provide an effective remedy or fair and adequate compensation to victims. They include the ICCPR (ratified by Israel in 1992), the U.N. Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT, ratified by Israel in 1991), the International Covenant on the Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD, ratified by Israel in 1991), the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW, ratified by Israel in 1991), and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC, ratified by Israel in 1991).[43]

Regional and international human rights bodies characterize these obligations as a "duty of guarantee": not only are countries bound to refrain from violating the rights of an individual, but they must also honor five basic obligations, which together form the cornerstone of the international system to protect human rights.[44] These are the obligations to:

Investigate serious violations of human rights;

bring to justice, and discipline or punish, those responsible;

provide an effective remedy for the victims;

provide fair and adequate compensation to the victims and their relatives; and

establish the truth about what happened.

These duties are complementary one does not substitute for another. Together, they comprise the most effective deterrent for the prevention of human rights violations. A state is accountable for human rights violations not only if it infringes rights through direct acts or negligence, but also if it fails to take appropriate steps to investigate facts, curb criminal behavior, and compensate the victims and their relatives.

The obligation to investigate wrongdoing, prosecute offenders, and compensate the victims is strongest in cases of the most serious human rights abuses, such as: torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment; extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions; and "disappearances." The rights to life and freedom from torture and ill-treatment are among the most strongly-protected of all human rights. No state may derogate from its obligation to protect these rights, even in states of emergency. They are widely recognized as having reached the status of customary international law.[45]

Whatever situation they may be in, individuals are always protected from arbitrary deprivation of life. But when hostilities occur, the decision of what constitutes an arbitrary deprivation of life is interpreted by using IHL standards, which in this situation operates as lex specialis.[46]In this context, judging whether someone was killed or injured unlawfully will depend on whether the possible perpetrator obeyed the principles of proportionality, military necessity, and distinction discussed above.

In many cases, this means not just determining whether the individual followed his or her rules of engagement, but also whether these rules were appropriate in the first place. Declaring a situation to be one of armed conflict is not a blank check, and does not let people fire a weapon at will. Nor can it ever justify torture, ill-treatment or sexual abuse, which are forbidden at all times.

What Makes a Good Investigation?

If investigations are to promote accountability, they must meet international standards of thoroughness, timeliness, and impartiality.

Human rights bodies such as the U.N. Human Rights Committee, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) have discussed in detail the practical criteria that distinguish good investigations from bad. In cases of the most serious human rights violations, disciplinary or administrative action is not enough to satisfy the state's obligation to provide an effective remedy. According to the doctrine of the U.N. Human Rights Committee,"Whereextrajudicial executions, enforced disappearance or torture are concerned, it is essential for the remedies to be judicial in nature."[47]

The ECHR has developed more than a decade's worth of jurisprudence on investigations into alleged unlawful killings in Turkey and Northern Ireland. It has laid out standards of investigation into alleged human rights violations:

[T]he notion of an 'effective remedy' entails, in addition to the payment of compensation where appropriate, a thorough and effective investigation capable of leading to the identification and punishment of those responsible, and including effective access for the complainant to the investigatory procedure.[48]

Remedies must be effective in practice, not just in theory, with a sufficient element of public scrutiny to ensure true accountability.[49] In particular, alleged violations of the right to life

deserve the most careful scrutiny. Where events lie wholly or largely within exclusive knowledge of the authorities... strong presumptions of fact will arise in respect of injuries and death which occur. Indeed, the burden of proof may be regarded as resting on the authorities to provide a satisfactory and convincing explanation.[50]

The ECHR has also said that those responsible for or carrying out an investigation into unlawful killing by state agents must be independent from those implicated in events meaning "not only a lack of hierarchical or institutional connection, but also a practical independence."[51] In addition, the court has held that a prompt response by the authorities in investigating the use of lethal force is essential. Once a matter has come to their attention, the authorities must act on their own initiative, without waiting for a victim's relatives to lodge a formal complaint.[52] Unwarranted delaysin taking witness statements and opening investigation proceedings, or unexplained failure to make progress after a reasonable time, were each signs of ineffective investigations, the court found.[53]

Perhaps the most useful guide to investigation procedures is the U.N. "Principles on the Effective Prevention and Investigation of Extra-Legal, Arbitrary and Summary Executions." These principles establish a thorough and widely respected set of standards for the investigation of alleged killings by security forces and the subsequent legal proceedings.[54] Although they are non-binding, the principles represent a detailed guide to good practice in investigating alleged unlawful killings. The principles include requirements for:

thorough, prompt, and impartial investigation of all suspected cases of extra-legal, arbitrary, and summary executions;

an independent commission of inquiry for those cases in which the established investigative procedures are inadequate because of lack of expertise or impartiality, and for cases in which there are complaints from the family of the victim about these inadequacies or other substantial reasons;

protection from violence or intimidation for complainants, witnesses, families, and investigators;

removal from power or control over complainants, witnesses, families, or investigators of anyone potentially implicated in extra-legal, summary or arbitrary executions;

access by families and their legal representatives to any hearing and to all relevant information, and the right to present other evidence;

a detailed written report on the methods and findings of the investigation to be made public within a reasonable time;

government action to bring to justice persons identified by the investigation as having taken part in extra-legal, arbitrary and summary executions;

responsibility of superiors, officers or other public officials for acts committed under their authority if they had a reasonable opportunity to prevent such acts; and

fair and adequate compensation for the families and dependents of victims of extra-legal, arbitrary and summary executions within a reasonable period of time.

The texts of the sections of the Principles related to investigations and legal proceedings are reproduced in Appendix C of this report. In a meeting with representatives of the Criminal Investigation Division (CID) of the Israeli Military Police on July 13, 2003, Human Rights Watch asked whether international guidelines were incorporated into the CID's investigation manuals. Human Rights Watch was told, "We have Israeli law in our manuals... International law is with the JAG [Judge Advocate General]."[55]

Very few military judicial systems conform to the guidelines above. Many fail to reach basic standards of competence, due process, or judicial independence. Most of the cases recounted in this report involved deaths of civilians in circumstances other than armed hostilities. Some of these cases may constitute extrajudicial executions-i.e., murder. This is why it is crucial that thorough, impartial, and professional investigations take place. These are standards that apply to every country. Precisely because separate military jurisdiction all too often promotes impunity, and because military judicial systems often fail to provide most basic fair trial guarantees, "a consensus is taking shapewith regard to the need to exclude serious human rights violations committed by members of the armed forces or the police from the jurisdiction of military tribunals," and "military personnel lose their exemption from [ordinary domestic] jurisdiction so that the rights of victims can be taken fully into account."[56] Military judicial systems should investigate and punish only those offences that are strictly military in nature, such as internal issues of discipline. The U.N. Human Rights Committee and other treaty bodies, the Special Rapporteur on Torture,the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, country mechanisms of the Commission on Human Rights and Inter-American Court of Human Rights have all reached similar conclusions, in countries such as Guatemala, Lesotho, the Philippines, Peru, Morocco, the Russian Federation, Croatia, Chile, Brazil, and Uzbekistan.[57]

III. Israel's Investigations Policy

During the first Palestinian uprising (intifada), which began in late 1987, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) ostensibly acted in accordance with General Staff Command 33.0304, which required the opening of a Military Police investigation in every case in which a civilian was killed by IDF soldiers, except if involved in combat activities.[58] In practice, this policy was poorly implemented.[59] Nongovernmental organizations strongly criticized the adequacy, timeliness, and partiality of these investigations, pointing to a repeated failure to interview Palestinian witnesses, ethnic stereotyping, careless procedures, and inexplicable delays in investigation progress.[60] In 1994 Brigadier GeneralAmnon Strashnov, Judge Advocate General from 1988-1993, acknowledged the loose standards followed by the Judge Advocate General's (JAG) office when he described the lenient standards his office used in charging, trying, and sentencing soldiers as the "intifada factor."[61]

The IDF used a broad definition of "combat activities" several times between 1993 and September 2000 when justifying its refusal to investigate killings. For example, the IDF refused to investigate the 1996 killings of forty-seven Palestinian civilians and thirteen members of the Palestinian security forces during clashes at the opening of a highly controversial tunnel near Jerusalem's al-Aqsa mosque compound, stating it had designated the events as "combat incidents."[62] The IDF similarly refused to investigate its soldiers' conduct in the killing of six Palestinian civilians and two security force members during the May 2000 demonstrations on the 52nd anniversary of the first Arab-Israeli war.[63]

Within three weeks of the outbreak of current violence, in late September 2000, more than 120 Palestinians were killed by Israeli security forces, and over 4,800 injured. Thirteen Palestinian citizens of Israel were killed by the national police. In the outcry that followed, the government of Israel set up a formal commission of inquiry, known as the Orr Commission, to examine the deaths of the thirteen Israeli citizens.[64] In the cases of deaths of Palestinian residents of the occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip, the IDF determined that the situation was "approaching armed conflict," and informed governments and human rights groups that these and subsequent killings would not be investigated.[65] In January 2001 IDF representatives told Amnesty International that three investigations had been opened into killings of civilians. By this stage, some 300 Palestinians had been killed, including at least 85 children.[66]

The IDF's policy of non-investigation was immediately criticized - and not just by human rights groups. The report of the Sharm el-Sheikh Fact Finding Committee, headed by former U.S. Senator George Mitchell, described Israel's use of the term "armed conflict" as "overly broad, for it does not adequately describe the variety of incidents reported since late September 2000." The report's authors, charged with finding a means to return to a peace process, then underlined the consequences of Israel's policy decision not to investigate:

Moreover, by thus defining the conflict, the IDF has suspended its policy of mandating investigations by the Department of Military Police Investigations whenever a Palestinian in the territories dies at the hands of an IDF soldier in an incident not involving terrorism... . We believe, however, that by abandoning the blanket "armed conflict short of war" characterization and by re-instituting mandatory Mmilitary Police investigations, the [Government of Israel] could help mitigate deadly violence and help rebuild mutual confidence.[67]

From 2001to 2002, this IDF policy continued with little public scrutiny. This began to change after an unprecedented series of suicide attacks against Israeli civilians in March 2002 led to major Israeli military operations throughout the West Bank. During these operations, thousands of Palestinians were injured, arrested, or made homeless. Israeli troops forced Palestinians civilians to assist military operations and used others to shield themselves from danger.[68] Troops looted and damaged the property of civilians and of the Palestinian Authority.[69] In April 2002 the IDF carried out a major military operation in Jenin refugee camp. A Human Rights Watch investigation at the time confirmed that at least twenty-two of the confirmed Palestinian deaths in the operation were civilians, including children and physically disabled and elderly people.[70] When the Israeli government reversed its earlier decision to cooperate with a United Nations fact-finding team on events in Jenin, the question of the behavior and accountability of Israeli military forces received greater scrutiny, for a short while, both in Israel and abroad.[71] The Israeli government opened Military Police investigations into several cases of looting and the forced use of civilians in military operations, but did not investigate any cases of civilian deaths.[72]

In the following twelve months - and in the wake of several high-profile civilian killings - Israeli military officials developed a more cohesive public relations strategy. Faced with increasing scrutiny from Israeli journalists, parliamentarians, and nongovernmental groups, military spokespersons and members of the JAG's office emphasized the frequency with which Military Police investigations were being opened but no such increase occurred regarding cases in which civilians were killed.[73]In 2002, the new chief of staff, Moshe Ya'alon, ordered that initial "operational investigations" into civilian deaths cross his desk within three days of any incident, and that the findings of regional command level investigations-in both cases inquiries conducted without investigative standards-be given to him within three weeks.[74] The JAG's office released more detailed information regarding the number and nature of Military Police investigations, and agreed to make biannual presentations to the Knesset's Law, Constitution, and Legal Affairs Committee.[75] Human Rights Watch asked the chief military prosecutor in July 2003 whether the increased information meant any change in underlying policy regarding investigations, and was told that it did not.[76]

Between September 30, 2000, and May 10, 2004, the IDF opened a total of 506 Military Police investigations into alleged wrongdoing by Israeli soldiers in the OccupiedPalestinianTerritories. In comparison to investigations into deaths and injuries, investigations into property damage or theft and beatings and ill-treatment were more frequent (see Graph 2): just seventy-four of these investigations were into alleged cases of unlawful use of lethal force causing death or injury.[77] Fifteen individuals were indicted as a result. One soldier was convicted of (negligently) killing a Palestinian and was sentenced to two months' imprisonment.[78] The soldier responsible for killing a sixteen-year-old student served only a fraction of the time to which five Israeli conscientious objectors had been sentenced a few months earlier.[79]

During the same period some 500 Palestinian children and 2,500 Palestinian adults were killed. Estimates of how many of the Palestinians killed were civilians vary considerably, and range as high as 75 percent.[80] In January 2004, Israeli journalist Akiva Eldar reported that the Shin Bet had defined fewer than 600 of the 2,500 Palestinians killed as "terrorist."[81] According to the Israeli human rights organization B'Tselem, between the beginning of the intifada and the end of November 2004, 3,040 Palestinians were killed by Israeli security forces, including 606 children, in the OccupiedPalestinianTerritories. B'Tselem concluded that at least 1,661 of those killed (including 531 children under the age of 18) were not involved in hostilities when they were killed.[82] The number of official investigations into alleged wrongful use of lethal force equals just two percent of the total number killed (see Graph 1) and only 15 percent of the number of children killed, despite the fact that many deaths occurred in non-combat circumstances and the extreme unlikelihood that many of the children killed were legitimate targets. During this period, Human Rights Watch itself notified the JAG's office of more than sixty specific suspected cases of unlawful killing or injury.

When the IDF refuses to investigate its actions, there are no alternative forms of accountability. Unlike many other countries, there is no other institution with the power to investigate human rights abuses to which Palestinian victims and their families can effectively turn. The West Bank and Gaza Strip are ruled under military law: Palestinians cannot seek prosecution of Israelis in Israeli military courts, or in the courts administered by the Palestinian Authority. They must therefore seek recourse through Israeli civilian institutions, even though they almost always lack the mobility or resources to access them.[83] Unlike Mexico or Northern Ireland, Israel has no national human rights institution, nor any independent commissioner for complaints about human rights violations committed by the army. Unlike Turkey, Colombia, or the Russian Federation, Israel is not subject to the jurisdiction of a regional human rights court, such as the Inter-American Court of Human Rights or the European Court of Human Rights. At best, Palestinians living in the West Bank or Gaza Strip may employ Israeli lawyers to petition Israel's High Court of Justice to order the IDF to investigate if they can overcome the severe logistical and financial barriers to doing so.

Graph 1: Palestinian Deaths, IDF Lethal Force Investigations and Indictments.[84]

Graph 2: IDF Military Police Investigations in the Occupied PalestinianTerritories as of May 2004, by Investigation Type.[85]

IDF Arguments

The IDF, in response to petitions before the High Court of Israel, has used several arguments to support its policy of non-investigation.[86] The first is that investigations would harm the special nature of combat operations. The second is that other armies facing a similarly intense level of hostilities do not investigate civilian deaths. The third, discussed in section VI of this report, is that the practical difficulties of investigating civilian deaths in the OccupiedPalestinianTerritories are simply too much for the system to bear.

The IDF argues that combat operations have "unique characteristics" and serve an important national interest. To subject military personnel to investigation would discourage them from taking the risks required for successful combat operations, and place an unjustified burden on morale and the chains of command. The State Attorney's Office, responding to a petition to open an investigation of the July 2002 bombing of a Gaza apartment building that killed Salah Shihada, a leader of Hamas's military wing, and fifteen civilians, including nine children, cited an earlier High Court of Israel decision rejecting a petition for criminal prosecution on account of negligence, in which the Court wrote that "the unique characteristics of active operations sometimes constitute considerations negating the presence of a public interest in the instigation of criminal proceedings, even if criminal liability is present."[87] In its ruling the Court acknowledged that in ordinary cases "there is a clear public interest in deterring offenders from similar acts in the future," but concluded that "in cases of negligence committed during active operations, there is, at the present, almost no need for such deterrence."[88] The state argued in the Shihada case that Court's reasons for not authorizing criminal investigations in negligence cases "during active operations" should be an even greater barrier to such investigations in "combat operations," where "the possible ramifications of a criminal investigation for the chain of command and the willingness of commanders to perform their functions are extremely dramatic. Taking these policy considerations into account, it is clear that the cases in which a criminal investigation will be instigated with regard to combative operations shall be exceptional and unusual."[89]

In a meeting with Col. Daniel Reisner, assistant military advocate general, on May 5, 2002, Human Rights Watch asked what kinds of cases were "exceptional" enough to warrant investigation. Colonel Reisner did not reply directly. Instead, he said "[t]here is a big question regarding criminal investigation during armed conflict. The gravity of the crime [required to trigger an investigation] increases during armed conflict. International practice is not clear."[90] Col. Reisner did not indicate if acts more serious than simple negligence would meet the gravity test; nor did he address the fact that many deaths and injuries did not occur in circumstances of armed hostilities.

The IDF's position cannot be reconciled with Israel's obligations under international humanitarian law or international human rights law. The government of Israel has ratified numerous treaties that contain explicit requirements to prevent violations of human rights or the laws or war and to discipline and bring to justice those responsible. This does not mean that every soldier's error must be followed by higher-level investigation or court-martial but that all cases with prima facie evidence or credible allegations of serious wrongdoing should be investigated professionally and impartially. Mere operational debriefings (described in section IV) absolutely fail this test. No state can fulfill its responsibility to maintain public order if agents who abuse their authority or misuse lethal force are allowed to do so unchecked.

The IDF's second argument is to characterize the entire situation in the OccupiedPalestinianTerritories since late September 2000 as one of armed conflict, and assert that no other army investigates civilian killings in such circumstances.In support of its case, it has cited the lack of U.S. investigations in Afghanistan and Iraq, as well as the final report of a committee appointed by the prosecutor of the International Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia to review the NATO bombing of the former Yugoslavia.[91] When asked by Knesset member Gil'ad Arden in 2003 whether there was an army that handed investigations over to an external body, Major-General Dr. Menachem Finkelstein answered only in terms of U.S. practice:

[R]egarding your question, there is no similarity. I can give you examples. When the United States sent troops to Kosovo or to Eritrea, and to Somalia, there were cases in Somalia where hundreds were killed on the Somali side, and 18 on the American. If you think that in these cases there were investigations there were not. At the same time, I think that in this matter, we do not need to learn from the Americans. We have our measures and our ethical standards. I think that there is no comparison ... ."[92]

In the same Knesset hearing, Finkelstein publicly stated his commitment to ensuring Israel's conformity to best practices. "They [human rights groups] say to me, and I accept, that the Israeli army has to behave differently from the United States army. Completely acceptable to me. But, here I say to them: show me an alternative route to take."[93]

This argument ignores the fact that many killings of Palestinian civilians, including almost all of the cases investigated in this report, occurred when the army acted in law enforcement situations. When military forces engage in policing, they should be held to policing and law enforcement standards. Those standards are clearly articulated, and require timely, thorough, and impartial investigations into killings of civilians.

There are positive, practical alternatives to Israeli (and United States) practices in this regard, particularly when troops are accused of committing abuses in non-combat situations. There is the example of Canada, for example, which chose to investigate wrongdoing by Canadian troops accused of abusing prisoners while deployed in Somalia in 1993, and made sweeping changes to its military justice system as a result. Information on Canada's reform process is widely available, including on the Internet.[94] The IDF has likewise failed to acknowledge a decade of U.K. reforms to investigation procedures in Northern Ireland. Ongoing complaints against abuses by the militarized Royal Ulster Constabulary and the British army recently resulted in an independent police complaints commission and ombudsman, and an independent assessor of military complaints.[95] While the U.K. explicitly defined Northern Ireland as a law enforcement situation, not armed conflict, it does provide indicators for positive change.

There is at present no international law that requires civilian investigation of combat killings. However, the IDF's routine failure to conduct investigations extends to killings and serious injuries inflicted in clearly non-combat situations, when law enforcement standards apply. International law requires provision of an effective remedy for civilian deaths and injuries where there is credible information or prima facie evidence of excessive or unlawful use of force.

IV. Overview of the Military Justice System

Israel's military justice system is based on Military Justice Law 5715-1955, and subsequent amendments (hereafter referred to as the MJL).[96] The law sets out the powers of the IDF's chief legal officer, the Judge Advocate General, and the composition and powers of courts martial and appeals courts. It defines offences for which soldiers may be punished, including looting (Art. 74); illegal use of arms (Art. 85); negligence (Art. 124); obstructing a military policeman (Art. 126); non-compliance with orders (Arts. 123 and 133); and non-prevention of an offence (Art. 134). Soldiers do not bear criminal responsibility for non-compliance with an order "when the order given him is manifestly illegal" (Art. 125). In addition, soldiers may be charged with crimes under the Israeli penal code. Murder and manslaughter, for example, are not included in the MJL. Charges for these crimes would be brought under the penal code.