Summary

Since 2016, over 400 human rights defenders have been killed in Colombia—the highest number of any country in Latin America, according to the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR).

In November 2016, the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia, FARC) guerrillas reached a landmark peace accord, leading to the demobilization of the country’s then-largest armed group. The agreement included specific initiatives to prevent the killing of human rights defenders. Separately, that year the Attorney General’s Office decided to prioritize investigations into any such killings occurring as of the beginning of 2016.

However, killings of human rights defenders have increased as armed groups have swiftly stepped into the breach left by the FARC, warring for control over territory for coca production and other illegal activities.

The work of some rights defenders—opposing the presence of armed groups or reporting abuses—has made them targets. Others have been killed during armed groups’ broader attacks on civilians. The killings have exposed an underreported pattern of violence and abuse in remote parts of Colombia where law enforcement and judicial processes rarely reach. This absence of state institutions has left countless communities undefended.

Between April 2020 and January 2021, Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 130 people in 20 of Colombia’s 32 states to identify the dynamics behind the killings of human rights defenders, and to assess government efforts to prevent such killings or hold those responsible to account. Interviewees included judicial authorities, prosecutors, government officials, human rights officials, humanitarian workers, human rights defenders, and police officers.

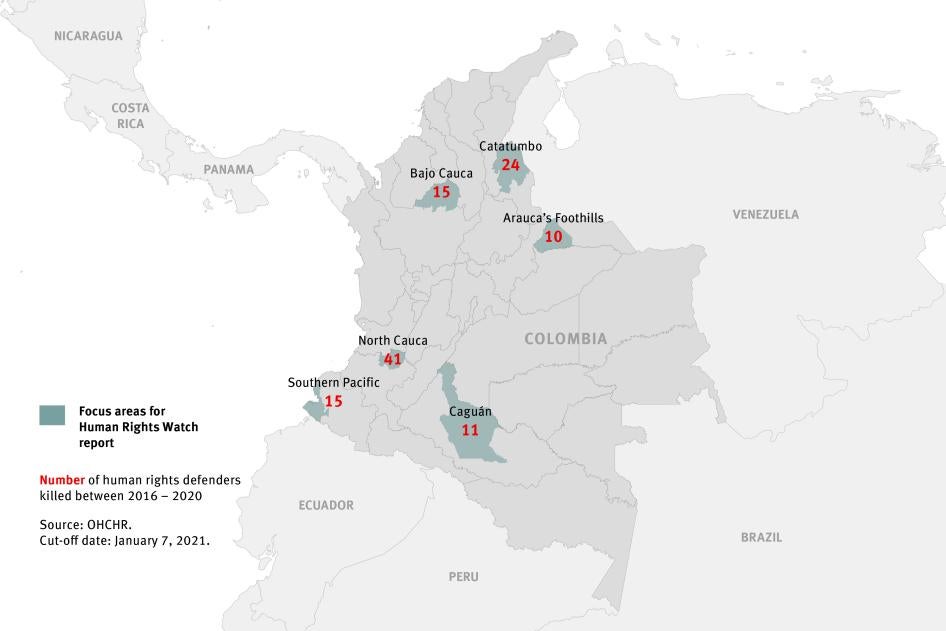

This report documents killings of human rights defenders in six of the areas that have been most affected by such crimes: the northern region of Cauca state, the Catatumbo region of North Santander state, the Southern Pacific region in Nariño state, the Bajo Cauca region of Antioquia state, the Caguán region of Caquetá state, and the foothills region of Arauca state. It explains the dynamics of violence leading to the killings of human rights defenders in these areas, as well as regional contexts influencing such crimes.

The report also examines each of the government’s policies to prevent and address killings of human rights defenders, as well as the shortcomings in their implementation.

Killings of Human Rights Defenders after the Peace Accord

Authorities’ failure to exercise effective control over many areas previously controlled by the FARC has in large part enabled the violence against human rights defenders. The government has deployed the military to many parts of the country but has failed simultaneously to strengthen the justice system and ensure adequate access to economic and educational opportunities and public services. Human Rights Watch’s research shows that these failures have significantly limited government efforts to undermine armed groups’ power and prevent human rights abuses.

The 2016 peace accord included plans to address illegal economies, lack of legitimate economic opportunities, and weak state presence—factors that have for decades allowed armed groups, including the FARC, to thrive.[1] But implementation of the plans has generally been slow. In June 2020, the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies—charged under the peace accord with verifying progress in its implementation—concluded that only 33 of the 88 objectives required to be met by 2019 had been completed.[2] Most of the objectives that had been met concerned demobilization of the FARC and reintegration of its fighters into society. Aspects of the accord relating to a comprehensive rural reform, as well as a new drug policy, had met “delays” indicating “a low probability that the objectives [under the accord] will be completed in the mid- and long-term.”[3]

The killing of human rights defenders in Colombia is a multi-faceted problem.

The limited state presence in many, mostly rural, areas means social organizations—including Neighborhood Action Committees, Afro-Colombian community councils, and Indigenous groups—often play a prominent role in performing tasks typically assigned to local government officials, including protecting at-risk populations and promoting government plans. This increases the visibility of the social organizations’ leaders, including human rights defenders, exposing them to risks.

Armed groups often oppress human rights defenders, trying to use them to impose “rules” within communities. That increases the possibility that groups will target them for real or perceived non-compliance or for allegedly supporting an opposing party.

Support by human rights defenders for some initiatives started under the peace accord has also placed them at risk. Human rights defenders have been killed for supporting or participating in projects to replace coca crops—the raw material of cocaine—with food crops. Many peasants in Colombia grow coca because it is their only profitable crop, given weak local food markets, inadequate roads to transport their products for sale, and lack of formal land titles. Government plans to give peasants economic and technical support for crop substitution have often been implemented slowly and face fierce opposition by armed groups, who may use violence and threats to force communities to continue growing coca.

Indigenous leaders are disproportionately represented among those killed. According to OHCHR’s numbers, 69 Indigenous leaders have been killed since 2016, making up approximately 16 percent of the 421 human rights defenders who have been killed in that period. Only 4.4 percent of Colombia’s population is estimated to be Indigenous.

According to OHCHR, 49 women human rights defenders have been killed since 2016. Sixteen women rights defenders were killed in 2019, compared to 10 in 2018. As of December 2020, OHCHR had documented five such killings in 2020, and was verifying 10 others. At least three women human rights defenders have been raped since 2016, according to OHCHR and the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office’s Early Warning System.

Government Steps to Address Killings of Human Rights Defenders

To address killings of human rights defenders in a sustained manner over the long term, it is critical that the government tackle the root causes of the problem. That will require a focused effort to permanently reduce the power of armed groups and organized crime through a range of measures, including criminal investigations aimed at dismantling these groups, as well as a more effective and substantial civilian state presence in remote regions. However, because of the immense profitability of the illegal drug trade, and the ability of criminal groups to corrupt authorities—even where there is a state presence—it is likely that new groups will continually step in to replace those that have disappeared, and keep engaging in violence and attacks on human rights defenders. It is crucial that the Colombian government adopt meaningful measures to stem this decades-long cycle, including by considering alternative approaches to drug policy that would reduce the profitability of the illegal drug trade.

At the same time, the government can and should immediately provide adequate protection to human rights defenders, and ensure that crimes against them are effectively investigated. For this report, Human Rights Watch examined each of the government’s systems, plans, and policies to protect human rights defenders.

Mechanisms to Protect Rights Defenders and Prevent Abuses

The Colombian government has two longstanding systems in place that have proven important to the protection of human rights defenders, though both suffer from insufficient funding and other constraints:

- The National Protection Unit, an office under the Ministry of the Interior, has been charged since 2011 with protecting people at risk. To its credit, it has granted individual protection measures to hundreds of human rights defenders, providing cellphones, vehicles, bulletproof vests, or bodyguards. However, while the National Protection Unit provides individual protection schemes in response to reported threats, many community leaders killed had not received threats or been able to report them to prosecutors, as required to access protection.

- The Early Warning System in the National Ombudsperson’s Office has a presence in multiple regions of the country where there are few other state actors, and specifically monitors threats to rights. Colombian law requires authorities to respond rapidly to prevent potential abuses flagged by the office through what are called “early warnings,” and the office has issued scores of such alerts identifying risks to human rights defenders in hundreds of municipalities in the country. However, national, state, and municipal authorities charged with taking action based on the Early Warning System’s recommendations have repeatedly failed to do so or have reacted in a pro-forma and unsubstantial way, leading to scant impact on the ground.

Additionally, in recent years, Colombian authorities have created an array of other mechanisms, some of which were established under the 2016 peace accord. The administration of President Iván Duque has superficially promoted these mechanisms, often giving the impression that it is taking action, even while most of these systems are barely functional, or have serious shortcomings. The problems with these mechanisms include:

- The large number of protection mechanisms, which diffuses resources and wastefully duplicates efforts.

- Slow implementation of government plans to protect entire at-risk communities and non-governmental organizations that protect rights. The government has yet to implement a 2018 comprehensive Ministry of the Interior protection plan. Efforts by the National Protection Unit to implement its own collective protection programs have faced significant budgetary and other constraints.

- Failure by President Duque’s administration to periodically convene the National Commission of Security Guarantees, a body charged with designing policies to prevent killings of human rights defenders. Their work has to date been unsubstantial and had no concrete results.

- The vague and unclear mandate of a 2018 action plan by the Ministry of the Interior to protect human rights defenders, known as the Timely Action Plan, which has meant it has scant impact on the ground.

- Failure by the Office of the Presidential Advisor for Stabilization and Consolidation to implement a plan announced in 2019 to protect civilians who participate in plans to replace coca crops, including human rights defenders.

- Lack of progress in implementing a 2019 plan by the Ministry of the Interior to protect community leaders in Neighborhood Action Committees.

- Lack of progress in developing a new policy to protect human rights defenders and other community leaders, which has been under discussion between the Ministry of the Interior and human rights groups since August 2018.

Accountability Efforts

Efforts to bring perpetrators to justice have been more meaningful. Authorities have passed directives and created specialized units to prosecute killings of human rights defenders, achieving significant progress compared to previous periods in Colombian history.

However, many investigations and prosecutions face significant hurdles, particularly with regard to the “intellectual authors” of many killings. Key shortcomings include:

- Too few prosecutors, judges, and investigators in the areas most affected by these killings.

- Failure to date to create a “special team” of judges President Duque announced in May 2019 to try cases involving killings of human rights defenders.

- Limited capacity of special bodies created under the peace accord to handle these cases—including the Special Investigation Unit and the Police’s Elite Team—, including few staff members; some have faced budget cuts.

- Limited support—often marred by delays—from police officers and the military for prosecutors and investigators visiting crime scenes.

To meet its obligations under international human rights law, the Duque administration should undertake serious efforts to fund and implement policies to prevent the killings of human rights defenders and protect their rights. Authorities should substantially increase the capacity of judicial authorities and prosecutors to bring those responsible for the killings to account.

In the longer term, authorities should initiate a process to simplify and strengthen prevention and protection mechanisms under Colombian law. They should ensure civil society groups and international human rights and humanitarian agencies participate meaningfully in that process. The aim should be to coordinate existing mechanisms, overhauling, or abrogating those that are ineffective or have an unclear mandate.

Unless the government takes serious action, many more human rights defenders are likely to be killed, leaving hundreds of vulnerable communities undefended.

Recommendations

To the Administration of President Iván Duque of Colombia:

- Initiate a process with meaningful participation by civil society groups and international human rights and humanitarian agencies operating in Colombia to simplify and strengthen prevention and protection mechanisms under Colombian law, including by overhauling or abrogating ineffective mechanisms that have an unclear mandate such as the Timely Action Plan (Plan de Acción Oportuna de Prevención y Protección para los Defensores de Derechos Humanos, Líderes Sociales, Comunales y Periodistas, PAO), coordinating other existing mechanisms, and ensuring these mechanisms are responsive to the needs of human rights defenders, regardless of ethnicity, race, gender or other protected status.

- Ramp up efforts to increase state presence in remote areas of the country and address root causes of violence, including by implementing the so-called Territorial Development Programs (Programas de Desarrollo con Enfoque Territorial, PDET), which seek to increase the presence of state institutions in remote municipalities across Colombia.

- Work with the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office to develop guidelines that ensure that the Inter-Agency Commission for the Rapid Response to Early Warnings (Comisión Intersectorial para la Respuesta Rápida a las Alertas Tempranas, CIPRAT), which is charged with deciding on responses to early warnings by the Ombudsperson’s office, responds promptly and effectively to early warnings, and to ensure meaningful evaluation of past responses and their impact.

- Improve the operation of the National Protection Unit, including by working with Congress to increase its budget, increasing the number of analysts on staff, transferring protection schemes for government officials to the National Police, easing the requirements to grant protection, working with affected communities to develop protection schemes suitable to rural areas’ risks and conditions, with a focus on ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation and other characteristics that may affect their risk and needs.

- Overhaul the National Protection Unit’s collective protection program, including by transferring it to the Ministry of the Interior, combining it with the Comprehensive Program of Security and Protection (Programa Integral de Seguridad y Protección para Comunidades y Organizaciones en los Territorios), significantly increasing its budget, and easing the requirements to grant protection.

- Implement and work with Congress to fully fund collective protection programs as established under the 2018 Comprehensive Program for Security and Protection, as well as the National Commission of Security Guarantees (Comisión Nacional de Garantías de Seguridad) and the National Process of Guarantees (Proceso Nacional de Garantías).

- Implement and work with Congress to fund the Comprehensive Program of Guarantees for Women Leaders and Human Rights Defenders (Programa Integral de Garantías para Mujeres Lideresas y Defensoras de Derechos Humanos), which seeks to address and prevent killings of women human rights defenders, expanding on the existing pilot projects in Putumayo and Bolivar.

- Implement and work with Congress to fund the special team of judges charged with trying cases of killings of human rights defenders and expand the program to include judges charged with overseeing earlier stages of the criminal process (known as “supervisory judges”).

- Ramp up efforts to help develop local prevention plans in all municipalities and states, including by working with Congress to ensure they have an appropriate budget, providing adequate training for local officials in charge of implementing the plans, and establishing a meaningful process for evaluating implementation, with a focus on ethnicity, gender, race, and other characteristics that may affect individuals’ risk and needs integrated throughout.

- Upgrade the rank of the Elite Team, which handles homicides of human rights defenders, within the hierarchy of Colombia’s National Police and increase its budget and staff.

- Continue using OHCHR’s tally of human rights defenders killed in the country as the official figure.

- Provide greater support to prosecutors investigating killings of human rights defenders, including by increasing the amount of time military helicopters devote to transporting prosecutors investigating crimes to places that security considerations render difficult to reach.

To the Colombian Congress:

- Ensure adequate budget for agencies and programs in charge of preventing and addressing killings of human rights defenders.

- Reform the Code of Criminal Procedure to ensure that alleged perpetrators of killings of human rights defenders seeking reduced sentences are required to provide exhaustive information on the killing and the armed groups involved, including by identifying people who gave the orders or approved of the crime.

To the Attorney General’s Office:

- Prioritize investigations into “intellectual authors” (people who gave the orders or approved) of killings of human rights defenders, including through plea bargaining with other perpetrators of these crimes.

- Pass an internal directive to ensure that prosecutors offering plea bargains to defendants allegedly involved in killings of human rights defenders require that they provide exhaustive information on the killings and the armed groups involved, including on the “intellectual authors,” while ensuring that perpetrators who cooperate receive protection from retaliation.

- Work with Congress to increase the staff and budget of the Special Investigation Unit, strengthen its capacity to investigate crimes and bolster the implementation of the unit’s investigative projects.

- Increase the number of prosecutors and investigators in areas most affected by killings of human rights defenders, as well as their technical capacity to investigate such crimes.

- Prioritize investigations into the financing sources of armed groups.

- Improve coordination and sharing of information between the Special Investigation Unit and other units within the Attorney General’s Office, including those in charge of “citizen security,” “organized crime,” and “criminal economies.”

To the Superior Council of the Judiciary:

- Work with the executive branch to establish the special team of judges charged with trying the killings of human rights defenders, as well as to increase the number of judges charged with overseeing criminal investigations (known as “supervisory judges”) in areas most affected by killings of human rights defenders.

- Provide training to criminal judges to ensure that rulings regarding killings of human rights defenders indicate, when possible, the motivation behind the homicide, whether the defendant belonged to an armed group, and the broader context in which the homicide took place.

- Establish a mechanism to assess the work of judges in cases of killings of human rights defenders.

- Establish the category of “human rights defender” in the judicial branch’s statistical information system to ensure that information regarding such cases is publicly available and disaggregated by ethnicity, gender, race, age, and other demographic factors.

- Publish rulings in cases of killings of human rights defenders on the council’s website.

To the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office:

- Strengthen the work of the early warning system, including by working with Congress to increase its budget and staff.

- Continue documenting killings of human rights defenders in the country, including by cooperating with OHCHR.

- As the technical secretariat of the National Process of Guarantees, which is charged with establishing measures to prevent abuses against human rights defenders, help ramp up implementation of the process, including by establishing mechanisms to assess implementation of the measures it established, with a focus on ethnicity, gender, race and other factors that may affect the level of risk and needs of human rights defenders.

To the Inspector General’s Office:

- Carry out prompt, exhaustive, and meaningful disciplinary investigations into the conduct of government officials who fail to take action to prevent killings of human rights defenders, in accordance with Directive 2 of 2017.

- Monitor the implementation by local authorities, including police officers, of local prevention plans.

To State and Municipal Governments:

- Work with the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office and the Inspector General’s Office to identify and address risks faced by human rights defenders with a focus on ethnicity, gender, race, and other characteristics that may affect their risk.

- Prioritize funds to design and implement local prevention plans.

- Promote the implementation of the Comprehensive Program of Security and Protection, a collective protection program.

To donor governments, including the United States and the European Union:

- Continue supporting key agencies in charge of preventing and addressing killings of human rights defenders in Colombia, particularly the Early Warning System and the Attorney General’s Office Special Investigation Unit.

- Press Colombian authorities to strengthen or overhaul existing prevention, protection and accountability mechanisms in the country, in line with the recommendations in this report, including by conditioning security assistance on reforms that ensure that these mechanisms are meaningfully implemented, have substantial impact on the ground, and meet the specific needs of human rights defenders at risk.

- Condition security assistance to Colombia on verifiable and concrete improvements in human rights in the country, particularly on killings of human rights defenders.

- Assess US drug and security policies and programs in Colombia to ensure that they help to address the root causes of killings of human rights defenders by strengthening the presence of civilian state institutions—not only security forces—in remote regions of the country, and exploring new avenues to reduce the power and corrupt influence of armed groups.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 130 people in 20 states in Colombia for this report. These included:

- 40 human rights defenders;

- 39 prosecutors or investigators;

- 25 officials of the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office or the Inspector-General’s Office;

- 16 officials of international human rights and humanitarian agencies operating in Colombia; and

- 10 officials of the Duque administration.

Interviews were conducted between April 2020 and January 2021. Due to restrictions linked to the Covid-19 pandemic, the vast majority were by telephone. All interviews were in Spanish.

Additionally, Human Rights Watch sent information requests to multiple Colombian government agencies, including the Ministries of Interior and Defense, the Attorney General’s Office, the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office, the Inspector General’s Office, the National Protection Unit, the Superior Council of the Judiciary, the Office of the Presidential Advisor for Stabilization and Consolidation, the Presidential Advisor on Human Rights, and the Office of the High Commissioner for Peace. The responses we received are reflected in the relevant sections of the report.

The report also draws on official statistics and documents from the Colombian government, publications by international and national humanitarian and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and news articles. The report cites OHCHR’s figures of human rights defenders killed in the country, which the Colombian government considers official.[4] We also cite figures by Colombia’s Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office, a government body independent of the executive, which normally reports more cases than OHCHR.

The report builds on findings in previous Human Rights Watch reports, including on Tumaco (December 2018), Catatumbo (August 2019), and Arauca (January 2020).[5]

Many of the interviewees feared for their security and only spoke to Human Rights Watch on condition that we withhold their names and other identifying information. We also withheld details about their cases or the individuals involved when requested, or when Human Rights Watch believed that publishing the information would put someone at risk. In footnotes, we may use the same language to refer to various interviewees, to preserve their anonymity.

We informed all participants of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and how the information would be used. Each participant orally consented to be interviewed.

Human Rights Watch did not make any payments or offer other incentives to interviewees. Care was taken with victims of trauma to minimize the risk that recounting their experiences would further traumatize them. Where appropriate, Human Rights Watch provided contact information for organizations offering legal, social, or counseling services, or linked survivors with those organizations.

In accordance with the UN General Assembly’s 1998 declaration on human rights defenders, “human rights defender” is defined broadly in the report as “everyone… [who] individually and in association with others … promote[s] and … strive[s] for the protection and realization of human rights and fundamental freedoms at the national and international levels.”[6] The definition hinges solely on the tasks carried out by the defender and does not require that they be part of a rights group or NGO.[7] OHCHR and the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office in Colombia also use the declaration’s definition to document killings of rights defenders in the country. In applying the definition to Colombia’s circumstances, the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office has identified several categories of rights defenders, including:[8]

- Communal leaders: people who defend human rights as part of their work on Neighborhood Action Committees, a unit of social organization.

- Indigenous leaders: people who defend Indigenous peoples’ rights; including Indigenous authorities; spiritual Indigenous leaders; and members of the “Indigenous guard,” groups recognized under Colombian law that patrol Indigenous territories armed only with wooden canes that are mostly of symbolic value.

- Peasant leaders: people who defend rights of peasants, including those claiming peasants’ rights to property over their land and restitution of land stolen during the armed conflict, and those promoting programs to replace coca crops with food.

- Afro-Colombian leaders: people who defend rights of Afro-Colombian groups and individuals, including traditional Afro-Colombian authorities and activists on community councils—a form of collective self-government.

- Community leaders: other people in rural areas who defend human rights without belonging to Neighborhood Action Committees, including leading figures in rural areas who formerly belonged to a committee.

- Trade unionists: people who defend rights through trade unions, including those promoting and protecting the right to enjoy just and favorable conditions of work.

- Victims’ rights activists: people who defend rights of victims of the armed conflict, including those seeking justice, truth-telling, reparations and guarantees of non-repetition for abuses committed during the armed conflict and those belonging to groups of victims of forced displacement.

- Women’s rights activists: people who defend women’s rights, including by asserting gender equality and sexual and reproductive rights.

Additionally, people in Colombia use the term “social leader” to describe a range of local activists and leaders who may or may not be considered human rights defenders.[9]

I. Background

Colombia has had the highest number of human rights defenders killed since 2016 in any country in Latin America.[10]

More than 400 human rights defenders have been killed nationwide in Colombia since 2016, according to OHCHR.[11] Despite a peace process with the FARC, reported killings have increased each year as armed groups have stepped into the breach left by the FARC, fighting for control over territory, engaging in illegal activities, and using violence against civilians to enforce their control.

The work of rights defenders, such as opposing the presence of armed groups or reporting abuses, has sometimes made them targets. Some have been killed during broader attacks by armed groups against civilians. OHCHR documented:

- 41 such killings in 2015 (including 39 men and 2 women);

- 61 in 2016 (including 57 men and 4 women);

- 84 in 2017 (including 70 men and 14 women);

- 115 in 2018 (including 105 men and 10 women);

- 108 in 2019[12] (including 92 men and 16 women); and

- 53 as of December 2020 (including 48 men and 5 women), and was verifying 80 others.[13]

The Covid-19 pandemic has slowed verification of cases in 2020 significantly.[14]

Other sources report even higher figures. The Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office has documented 710 cases since 2016, while Somos Defensores, a rights group, has reported 600.[15] Both the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office and Somos Defensores report an increase in killings of human rights defenders between 2019 and 2020.[16]

The Colombian government considers OHCHR’s figures to be official.[17] However, in August 2020, the presidential advisor on human rights, Nancy Patricia Gutiérrez, told Human Rights Watch that her office was working on a unified “protocol” to document these cases and had yet to decide which body would implement it.[18]

Human rights defenders have also faced other abuses. The Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office has registered 2,829 threats against human rights defenders occurring between January 2016 and June 2020, including 859 against women human rights defenders.[19] Most of them were death threats.[20] At least three women human rights defenders have been raped since 2016, according to OHCHR and the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office’s Early Warning System.[21]

Violence and Armed Conflicts in Colombia

Numerous armed groups operate in Colombia. Their size, structure, and origin vary widely.

Prior to its demobilization, which ended in 2017, the FARC was the largest armed group in the country. In June 2017, the UN mission in Colombia verified having received the weapons of the FARC guerrillas who accepted the agreement with the government.[22] In total, the government verified that 6,200 former FARC fighters, as well as 3,300 militia members (who provided support to armed groups in urban areas) had demobilized under the accord.[23]

But other major armed groups were not part of the peace negotiations and continued to operate. These include, most notably, the National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional, ELN), a leftist guerrilla group created in 1964, as well as the Gaitanist Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia, AGC), an armed group that emerged from a flawed demobilization of right-wing paramilitary death squads in the mid-2000s and is also known as “Clan del Golfo,” “Clan Úsuga” and the “Urabeños.”[24]

Additionally, some armed groups, known in Colombia as “FARC dissident groups,” emerged from the FARC’s demobilization. A minority of FARC fighters rejected the terms of the peace agreement and did not demobilize.[25] Most notable are former fighters of the FARC’s Eastern Bloc who continue to operate under the leadership of Miguel Botache Santillana, alias “Gentil Duarte,” mostly in eastern parts of the country.[26] They operate under different “fronts,” mainly the 1st, 7th and 40th.[27]

Other FARC fighters disarmed initially but then joined or created new groups, partly in reaction to inadequate reintegration programs and attacks against former fighters. For instance, in August 2019, Luciano Marín Arango, alias “Iván Márquez,” the FARC’s former second-in-command and top peace negotiator, announced he was taking up arms again.[28] He and other former FARC commanders created an armed group called “FARC Second Marquetalia,” after the area where the FARC was created in the 1960s.

FARC dissident groups vary significantly in size, organization, and engagement in violence. Some have been estimated to have over 300 fighters, with a high level of organization.[29] Others have a weak chain of command and limited level of organization.[30] They also vary in their degree of autonomy.[31] While some small groups operate autonomously, others have clear connections to larger, more organized armed groups, including other FARC dissident groups.[32]

There are other small armed groups (or criminal organizations) in Colombia. These include groups that emerged from the paramilitary demobilization in the mid-2000s, such as Puntilleros in Meta and Vichada,[33] as well as other criminal organizations, such as Contadores in Nariño, Rastrojos in North Santander, La Mafia (more recently, called Comandos de la Frontera, or Border Commands) in Putumayo and Caparros in Antioquia.[34] All of these groups are deeply involved in the drug trade.

Many armed groups stepped into the breach left by the FARC, and they fight each other for control over territory and illegal activities.[35] The situation in affected areas is highly dynamic, as the groups battle for control of illegal economies and land, seek to expand their operations, and at times establish mostly temporary alliances.[36]

Authorities’ failure to exercise effective control over many areas reclaimed from the FARC has in large part enabled this dynamic. The government has deployed the military to many parts of the country but has failed simultaneously to strengthen the justice system, improve protection for the population, and ensure adequate access to economic and educational opportunities and public services.[37] Human Rights Watch’s research shows that the failures have significantly limited government efforts to undermine armed groups’ power and prevent abuses.[38]

Applicable Legal Frameworks

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) lists several groups as parties to continuing armed conflicts, according to thresholds established under international humanitarian law.[39] In particular, the ICRC notes government forces are engaged in non-international armed conflicts against:

- The National Liberation Army;

- The Gaitanist Self-Defense Forces of Colombia;

- The Popular Liberation Army (Ejército Popular de Liberación, EPL), also known as “Pelusos,” a splinter group from a guerrilla that demobilized in the 1990s; and

- Former fighters of the FARC’s Eastern Bloc (operating mainly through the 1st, 7th and 40th fronts).

Additionally, according to the ICRC, fighting between the ELN and the EPL in the northeastern region of Catatumbo amounts to a non-international armed conflict.[40]

It is unclear whether other FARC dissident groups can be considered parties to armed conflict. While they vary significantly in size and level of organization, several FARC dissident groups do not appear to fulfill the thresholds under international humanitarian law to be in and of themselves parties of an armed conflict.[41] Consequently, whether each of them is a party to the conflict depends on the extent to which it is genuinely linked with parties to the conflict, particularly the former Eastern Bloc, or with other FARC dissident groups, in practice creating a single group that satisfies the requirements to be a party to the conflict under international humanitarian law.[42]

Profile of Victims

As of December 2020, OHCHR has documented 421 killings of human rights defenders in Colombia since 2016.[43] The main categories of human rights defenders killed in that period, as identified by OHCHR, include the following (see the Methodology section above for a definition of each category):[44]

- Communal leaders: 130 cases

- Community leaders: 67 cases

- Indigenous leaders: 69 cases

- Peasant leaders: 33 cases

- Afro-Colombian leaders: 18 cases

- Trade unionists: 12 cases

- Victims’ rights activists: 10 cases

Indigenous leaders are disproportionately represented among those killed. According to OHCHR, approximately 16 percent of all the human rights defenders killed since 2016 were Indigenous leaders. Only 4.4 percent of Colombia’s population is estimated to be Indigenous.[45]

Data from OHCHR and the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office suggest that defending human rights homicide in Colombia may put women at a heightened risk of violence. Between 10 and 15 percent of the human rights defenders killed in Colombia since 2016 were women.[46] Comparatively, women account for roughly 8 percent of the total number of homicides in the country between 2016 and November 2020.[47]

There are common patterns in the areas where these killings take place. Of all killings of human rights defenders occurring between 2016 and December 2020, according to OHCHR:[48]

- 70 percent occurred in rural areas (only 9 percent in Colombia’s 13 “main cities”).[49]

- 98 percent occurred in municipalities where armed groups operate, including organized crime groups and parties to the armed conflicts.

- 97 percent occurred in municipalities with illegal economies, including drug trafficking and production, illegal mining, extortion, illegal logging, and smuggling.

- 92 percent occurred in municipalities with drug trafficking and production.

- 47 percent occurred in municipalities with illegal mining.

- 91 percent occurred in municipalities with murder rates of over 10 per 100,000 people, which the World Health Organization considers the threshold for “endemic violence.”[50]

- 100 percent occurred in municipalities with poverty levels (measured on the basis of a government “multidimensional poverty index”) above the national average.[51]

- 57 percent occurred in municipalities that the government considered in 2017 to be historically the “zones most affect by the armed conflict.”[52]

- 52 percent occurred in municipalities where the government has announced “Territorial Development Programs” (PDET), an initiative created by the peace agreement with the FARC for areas highly affected by the armed conflict, poverty, lack of state presence, and illegal economies.[53]

Profile of Perpetrators

Colombian authorities have yet to identify those responsible for many cases of killings of human rights defenders (see section on accountability, below). However, based on progress achieved in investigations and prosecutions of 257 cases of killings occurring between 2016 and December 2020 and documented by OHCHR, the Attorney General’s Office believes that armed groups are responsible for the majority of those cases, 174.[54]

Authorities believe public security forces were the perpetrators in another 10 cases (including 6 under investigation in the military justice system), and say that evidence in 78 others points to people who did not have links to armed groups or who acted in their “own interest.”[55]

Cases involving armed groups allegedly include:[56]

- FARC dissident groups:[57] 62 cases

- Small armed groups (known in Colombia as “groups of ordinary organized crime,” or “type C” groups):[58] 35 cases

- Gaitanist Self-Defense Forces of Colombia: 24 cases

- ELN guerrillas: 23 cases

- EPL: 12 cases

- Caparros: 6 cases

- Organized crime groups (known in Colombia as “organized criminal organizations” or “type B” groups):[59] 11 cases

- Contadores: 1 case

II. Regional Case Studies

Since 2016, human rights defenders have been killed in 28 of Colombia’s 32 states and in roughly 20 percent of the country’s municipalities.[60]

This section examines the underlying violence connected to the killings of human rights defenders in six of the areas that have been most affected: North Cauca, Catatumbo, Southern Pacific, Bajo Cauca, Caguán, and Arauca’s foothills.[61] While these areas suffer some of the largest numbers of killings of human rights defenders, their totals represent only roughly 30 percent of cases committed nationwide between 2016 and 2020.[62]

North Cauca (Cauca state)

Cauca state is in southwestern Colombia. The population of its northern region—encompassing the municipalities of Buenos Aires, Caldono, Caloto, Corinto, Guachené, Jambaló, Miranda, Padilla, Puerto Tejada, Santander de Quilichao, Suárez, Toribío and Villa Rica—has for decades endured abuses by armed groups often seeking to profit from the region’s gold mines and coca fields or from moving drugs.[63]

Several armed groups operate today in North Cauca, including the ELN and groups that emerged from the demobilization of the FARC.[64]

The ELN, with roughly 50 armed fighters in the region, operates mostly in the west, towards the Pacific coast.[65] Two FARC dissident groups, the Jaime Martínez and the Dagoberto Ramos mobile columns, have reached an agreement between each other regarding the areas where they operate, according to prosecutors and local human rights officials.[66] They have close ties to fighters from the FARC’s former Eastern Bloc, which rejected the peace accord and operates under the leadership of Miguel Botache Santillana, alias “Gentil Duarte,” in mostly eastern parts of the country.[67]

The Jaime Martínez mobile column operates mostly in western parts of North Cauca, while the Dagoberto Ramos mobile column operates largely in central and northern parts.[68] Additionally, some credible reports indicate that fighters of the “FARC Second Marquetalia,” a dissident group led by the FARC former second-in-command Luciano Marín Arango, alias “Iván Marquez,” have recently arrived in some western parts of North Cauca.[69] Armed groups have engaged in numerous abuses in North Cauca, including killings, child recruitment, forced displacement, and threats.[70]

The Duque administration has repeatedly deployed soldiers to the area. In August 2019, the Ministry of Defense announced it would send 1,350 soldiers to Cauca, including 600 charged with fighting drug trafficking.[71] In October 2019, President Duque said he would deploy 2,500 additional soldiers, as part of a “rapid deployment force.”[72] Additionally, in December 2020, the Ministry of Defense told Human Rights Watch that it had increased the number of soldiers in three military units in Cauca.[73]

However, the situation in North Cauca has not improved. Armed groups continue to control mostly rural areas and engage in heinous abuses.[74] The region saw a stark increase in the number of recorded homicides, from 155 in 2017 to 379 in 2019.[75] In 2020, homicides declined at least in part due to the lockdown measures imposed in connection to the Covid-19 pandemic.[76] Authorities reported 306 homicides in North Cauca between January and late-November 2020.[77]

The situation remains highly dynamic, as the many armed groups fight for control over illegal economies and land, and seek to expand their operations.[78] In past decades, local activists and rights defenders would seek to intervene before armed groups on behalf of their communities, including to end specific abuses or to understand the groups’ “rules.” But in today’s dynamic situation, people often do not know whom they can talk to, or what the groups’ “rules” are.[79]

Armed groups have killed a high number of human rights defenders in North Cauca since 2016. OHCHR had documented 41 cases as of December 2020, while the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office had documented 96, as of September 2020.[80]

Roughly half of the cases documented by OHCHR and the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office involve leaders from the Indigenous Nasa communities.[81] Many of them have been killed because they oppose the presence of armed groups, and particularly drug trafficking, in their territories.[82] Under Colombian law, Indigenous communities are entitled to arrest and try people who commit crimes on their territories.[83]

This includes enforcement by the Nasa “Indigenous guard”— people who patrol their territory with Indigenous wooden staffs or canes that are mostly of symbolic value.[84] The Nasa people have seized weapons and drugs, and have arrested, tried, and convicted members of armed groups in their territory, including for threats and killings.[85] “They [the armed groups] have weapons, cars, and money, they have everything to wage war against us; we only have our Indigenous canes that symbolize our authority, our peaceful resistance, and our defense of the territory,” an Indigenous leader told Human Rights Watch.[86]

|

Eider Arley Campo Hurtado, 20, was killed by members of a FARC dissident group on March 5, 2018. Campo Hurtado, a member of the Indigenous guard, promoted the rights of Indigenous people on local radio and had been a Nasa authority in 2017.[87] On the day he was killed, nine fighters from a FARC dissident group attacked his community and released a fighter who had been imprisoned by the Indigenous community.[88] The fighters fled. Members of the Indigenous guard went after them, and the armed group opened fire, killing Campo Hurtado. Later that day, the Indigenous guard arrested eight fighters, all Indigenous, for the killing. They were convicted and sentenced to between 20 and 40 years in prison. “This is a vicious cycle [involving] those who bear the weapons and try to use our own people to control Indigenous territory. We are here to impede that; that is why they kill us,” Indigenous authorities said in the ruling in the case.[89] |

|

Cristina Bautista Taquinás, a 30-year-old Nasa Indigenous authority, was killed on October 31, 2019,[90] after her community was alerted that the Dagoberto Ramos mobile column had taken two community members hostage, according to a survivor and judicial authorities who examined the case.[91] Taquinás, as well as other Indigenous authorities and members of the Indigenous guard, went to the scene and managed to release the hostages. Gerardo Ignacio Herrera, alias “Barbas,” a commander of the Dagoberto Ramos mobile column, was one of the fighters at the scene, and the Indigenous guard parked a car in the middle of the road to block his flight. Members of the armed group then opened fire on the Indigenous guard for roughly 15 minutes, a survivor told the press.[92] “They were firing at us from everywhere,” she said. The fighters killed five Nasa people, including Taquinás, and injured several others. In November 2020, one member of the Dagoberto Ramos mobile column was charged in connection with the killing.[93] |

Peasant leaders have also been targeted in North Cauca. OHCHR has reported 6 killed since 2016; the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office has reported 22.[94]

Armed groups involved in drug trafficking in the region–especially the FARC dissident groups–often attack peasant leaders in retaliation for their support of government plans to replace coca crops with food, peasant leaders and prosecutors told Human Rights Watch.[95]

Cauca has one of the highest acreages of coca cultivation of any region in Colombia, and several government programs there provide economic and technical support to farmers who replace their coca crops with food.[96] Peasant leaders and others involved, as well as those who want the programs expanded, are “threatened verbally and ordered to leave the region,” or at times, “mentioned in armed groups’ statements as a ‘military objective,’” a peasant leader told Human Rights Watch.[97]

In January 2021, the Attorney General’s Office told Human Rights Watch that it was investigating 276 threats against human rights defenders and other local leaders in North Cauca occurring since 2016, including 16 against peasant leaders.[98] However, prosecutors told Human Rights Watch that the number of investigations is likely much higher. For example, one senior prosecutor in the area said that his office receives roughly 25 reports of threats against human rights defenders a week.[99]

Armed groups have also targeted Afro-Colombian leaders in North Cauca. OHCR reports one killed since 2016; the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office reports six.[100] Many others have been threatened.[101] Afro-Colombian leaders are often targeted because they oppose illegal mining and extortion of artisanal miners in the region, prosecutors, Afro-Colombian leaders, and local human rights officials told Human Rights Watch.[102] The groups extort more than 400 million COP (roughly US$100,000) a day from miners, a prosecutor told Human Rights Watch.[103] Extortion of legal miners, along with illegal mining, is a source of significant economic gain for FARC dissident groups and smaller criminal groups in the region.[104]

Security forces’ tolerance and possible collusion enables illegal mining in the region, prosecutors, human rights officials, and Afro-Colombian leaders told Human Rights Watch.[105] “Backhoes and mining supplies go through police and military checkpoints, and, despite criminal complaints, [authorities] do not conduct control operations,” an Afro-Colombian leader said.[106]

Catatumbo (North Santander state)

Catatumbo is a region of the northeastern state of North Santander, on the border with Venezuela. Comprised of 11 municipalities—Ábrego, Convención, El Carmen, El Tarra, Hacarí, La Playa, Ocaña, San Calixto, Sardinata, Teorama, and Tibú—it is an important source of cocaine, which is trafficked to other parts of Colombia and to Venezuela.[107]

Armed groups in Catatumbo include the ELN, the EPL, and an armed group that emerged from the demobilization of the FARC and calls itself the 33rd Front. Since early 2018, the ELN and the EPL have engaged in brutal fighting over territory, in part because in 2018 the EPL moved toward areas of Catatumbo occupied by the ELN.[108] In the second half of 2020, fighting among them appeared to reach a halt as the ELN recovered its territory and EPL fighters moved closer to the border.[109] Additionally, Rastrojos, an organized crime group, operates in the nearby municipalities of Puerto Santander and Cúcuta, where in recent times it has often engaged in fighting with the ELN.[110]

In October 2018, the Colombian government launched the “Force of Rapid Deployment 3” (Fuerza de Despliegue Rápido No. 3, FUDRA 3), which increased the number of military officers in Catatumbo by 5,600.[111] The new force was added to the army’s 30th Brigade, the 30th Engineer Battalion “José Alberto Salazar Arana,” and the Vulcano Task Force, a special military unit that has operated in Catatumbo since 2011 and has 4,000 officers.[112] The Ministry of Defense told Human Rights Watch that in 2020 it had increased the number of soldiers in the FUDRA 3 unit.[113]

However, the military strategy has made little impact on the situation in Catatumbo. Homicide numbers in the region rose from 190 in 2017 to 228 in 2019.[114] In 2020, homicides declined at least in part due to the lockdown measures imposed in connection to the Covid-19 pandemic.[115] Authorities reported 179 homicides between January and late-November 2020.[116] Armed groups continue to commit serious abuses, including against human rights defenders.[117]

Since 2016, 24 human rights defenders have been killed in Catatumbo, OHCHR reported, including 17 leading figures on local Neighborhood Action Committees.[118] The Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office reported 29 cases.[119] Some of them were not targeted for their work, but killed during armed groups’ attacks against civilians.[120]

|

Frederman Quintero Ramírez, a 32-year-old community leader, was killed on July 30, 2018. Around 3 p.m. that day, the perpetrators appeared at a bar and shot indiscriminately, killing 10 people, including Quintero Ramírez.[121] As they left, the perpetrators shouted that they belonged to the EPL, a ruling against one of them indicates.[122] Armed men appeared in El Tarra the day after the massacre, ordering residents to leave the area, three statements reviewed by Human Rights Watch asserted.[123] The July 30 attack appears to have been intended against members of the ELN who had failed to comply with an agreement with the EPL regarding the price of cocaine, a prosecutor told Human Rights Watch.[124] The EPL fighters were misinformed about the location of the ELN fighters; all the victims were civilians.[125] As of November 2020, authorities had convicted four EPL members and indicted three others for the massacre.[126] |

Five human rights defenders killed in Catatumbo since 2016 appear to have been targeted because an armed group accused them of links to an opposing party to the conflict, a prosecutor, an investigator, and a local human rights official told Human Rights Watch.[127] Colombia’s Attorney General’s Office found that none of the victims were members of armed groups.[128] But both the ELN and the EPL have conducted such killings to threaten people and ensure that they do not support the other party.[129] In two other cases, human rights defenders appear to have been killed because they interacted with government forces.[130]

|

Héctor Santiago Anteliz, the 52-year old president of a Neighborhood Action Committee, was killed on June 22, 2018. That afternoon, five members of the ELN appeared at his house and ordered him to accompany them, to discuss an issue with their commander.[131] The next day, a man from a nearby community called Anteliz’s family to report that they had found him dead,[132] with four bullet wounds, including one to the mouth. A prosecutor investigating the case says evidence suggests that Anteliz was killed because the ELN suspected he had links to the EPL.[133] |

|

Nelly María Amaya, 43, was killed on January 16, 2016. Amaya had in the past been president of a Neighborhood Action Committee and was a well-known community leader in San Calixto.[134] Around 7 p.m. on the day she was killed, two armed men arrived by motorcycle at her store; one shot her five times, and she died at the scene.[135] Evidence gathered by the Attorney General’s Office suggests that the EPL killed her because she sold food to army soldiers, an investigator told Human Rights Watch.[136] The EPL, which had threatened her in the past, distributed a pamphlet after her death saying that she had been killed for providing food to the army.[137] A member of the EPL is facing trial for the killing.[138] |

|

On February 11, 2018, EPL fighters killed Deiver Quintero Pérez, a community leader who organized sports activities to keep children away from armed groups in El Tarra.[139] Around 1 p.m. that day, two armed men abducted him from his workplace.[140] His body was found a few hours later, by a river, with several bullets in his head.[141] In August 2019, a member of the EPL was sentenced to 25 years in prison for the murder.[142] Evidence gathered by prosecutors indicates that the EPL killed Quintero because they believed he was cooperating with the government.[143] |

Armed groups in Catatumbo try to use human rights defenders and other local leaders to exercise control over communities. Several leaders told Human Rights Watch that the ELN, the EPL and the FARC dissident group in the region often summon them to meetings.[144] One of them told Human Rights Watch:

It is not an invitation…. They come to your house and tell you that you have to be in a given place on a given day, one cannot ask why… and they tell you that if you don’t go… you will bear the consequences.[145]

At the meetings, members of armed groups give local leaders “instructions.” For example, they establish times for circulation on the roads or order them to ensure that strangers, soldiers, and government officials do not enter their communities.[146] They threaten local leaders to ensure compliance. For instance, a communal leader told Human Rights Watch of a meeting in which a member of an armed group said, “X did not obey, and you saw what happened to him; now his widow is trying to collect money to buy a coffin.”[147]

Threats against local leaders have increased in Catatumbo since 2016, prosecutors and human rights officials told Human Rights Watch.[148] Often, armed groups threaten local leaders not to support government crop substitution programs, or not to tell people about the groups’ activities.[149] A community leader told Human Rights Watch:

They tell us… ‘Be careful, if we see you talking to people you should not be talking to, like snitches… you know, we can easily find you, and you will have to pack your stuff and leave’…. That is why we are afraid to speak, even with you people from human rights [groups].[150]

In January 2021, the Attorney General’s Office told Human Rights Watch that it was investigating 105 cases of threats against human rights defenders and other local leaders committed in Catatumbo since 2016, including 32 in 2019 and 39 between January and December of 2020.[151] Colombia’s Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office said that the number of threats against human rights defenders is much higher than the number being investigated.[152]

Southern Pacific (Nariño state)

The Southern Pacific region of the southwestern state of Nariño consists of the municipalities of Tumaco and Francisco Pizarro.

Several armed groups operate in the Southern Pacific region, including four that emerged from the FARC: the Oliver Sinisterra Front, United Guerrillas of the Pacific, and, more recently, the Alfonso Cano Western Bloc and the 30th Front.[153] An armed group called Contadores also operates in the municipality. Tumaco has one of the highest number of hectares with coca in Colombia, and all the armed groups there are deeply involved in producing and trafficking cocaine.[154]

All armed groups in the region abuse civilians, and the dynamics of violence in the municipality are ever-changing.[155] “We are subject to the movement of the groups,” an afro-Colombian leader told Human Rights Watch. “Before, it was the People of Order, after that the United Guerrillas of the Pacific, then Contadores, now the Oliver Sinisterra Front, and who knows what will come next? They make their alliances, then break them and fight, then make pacts to pit some groups against others … and all of us have to follow their orders, restrictions, and threats.”[156]

In January 2018, the government launched the “Atlas Campaign,” increasing the number of security officers in Tumaco and Francisco Pizarro and restructuring military and police units already operating. The government announced that a total of 9,000 security officers would protect rural and urban residents of these municipalities and eight others in Nariño.[157]

The military strategy has achieved few results in preventing abuses.[158] In Tumaco, for instance, 269 people were killed in 2018, compared to 210 in 2017 and 152 in 2016.[159] Homicides dropped in 2019, in large part due to an agreement that armed groups reached in December 2018 to halt their fighting for control of neighborhoods.[160] Authorities reported 175 homicides in Tumaco between January and late-November 2020.[161] Armed groups continue to control many of Tumaco’s urban neighborhoods and rural areas, engaging in serious abuses against civilians and imposing their own “rules.”[162]

While OHCHR and the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office have not reported killings of human rights defenders in Francisco Pizarro, such killings occur in high numbers in Tumaco. According to OHCHR, Tumaco is the municipality with the highest number of human rights defenders killed since 2016, with 15 such cases.[163] The Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office ranks Tumaco third since 2016, with 20 cases.[164] Human rights defenders killed in Tumaco include Afro-Colombian, Indigenous, and other local leaders.[165]

In at least three cases, armed groups killed human rights defenders after accusing them of collaborating with the military, the Attorney General’s Office reports.[166]

|

Holmes Alberto Niscué, a 40-year-old leader from Gran Rosario, an Indigenous Awá territory in Tumaco, was killed on August 19, 2018. Two men approached him in a bar and shot him four times, including in the face. Niscué had received death threats from the Oliver Sinisterra Front in June, and the National Protection Unit had moved him out of Tumaco to ensure his protection.[167] On the day he was murdered, Niscué had returned to Tumaco for a meeting.[168] According to press reports and a local prosecutor, the front accused him and other Awá leaders of having called in the army prior to a June 4, 2018, military operation in which six FARC dissidents, including a commander of the front, died.[169] Two members of the Oliver Sinisterra Front were on trial for Niscué’s homicide at time of writing.[170] |

|

Argemiro Manuel López Pertuz, 46, was killed on March 17, 2019, in the rural area of Guayacana, in Tumaco. Around 9 p.m., two men arrived at his house and shot him 12 times, killing him and injuring his wife and sister.[171] López Pertuz was president of Guayacana’s Neighborhood Action Committee and led the crop substitution program for 200 families.[172] Evidence gathered by prosecutors suggests he was killed by members of the Contadores who accused him of collaborating with the military.[173] In April 2019, the Attorney General’s Office announced the arrests of two members of the Contadores in connection with the killing.[174] They were awaiting trial at time of writing.[175] |

In three other cases, prosecutors believe armed groups killed human rights defenders because they supposedly failed to comply with the groups’ orders or “rules,” including not to collaborate with opposing armed groups. An Afro-Colombian leader told Human Rights Watch:

Whoever opposes their [drug trafficking] business is killed, whoever reports [them] to the army is killed, whoever fails to comply with their orders is killed, whoever behaves like a snitch with the opposing [armed group] is killed.[176]

|

Jose Cortés Sevillano, 55, president of a Neighborhood Action Committee, was killed on the night of September 6, 2019, when two armed men appeared at a bar and shot him.[177] Evidence suggests that the Oliver Sinisterra Front killed him, having accused him of providing information to the Contadores.[178] |

|

Rodrigo Salazar Quiñones, 44, an Awá Indigenous leader from the Piguambí Palangala in Tumaco, was killed on July 9, 2020.[179] Around 11:30 p.m., two men approached him when he was leaving his home, and shot him. Salazar Quiñonez had reported multiple threats from armed groups since 2014 and the National Protection Unit had granted him three bodyguards and an armored car.[180] But in 2020, the National Protection Unit decreased his protection scheme to just one bodyguard and a cellphone. When Salazar Quiñonez was killed, his bodyguard was not with him.[181] Prosecutors told Human Rights Watch that Contadores killed Salazar Quiñonez.[182] Evidence gathered by the Attorney General’s Office indicates that Salazar Quiñonez had placed a fence in the access road to his indigenous territory in order to prevent the spread of Covid-19.[183] Contadores apparently killed him because the fence limited the movement of their fighters in the area. As of November 2020, prosecutors had charged one Contadores fighter in connection with the murder.[184] |

In addition to killings, threats against human rights defenders in Tumaco have increased since 2016, judicial investigators, humanitarian workers, and community leaders report.[185] The Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office has registered 44 threats against human rights defenders in Tumaco since 2016, including 11 against women.[186] Many are connected to community leaders’ support for coca crop substitution plans, or to their opposition to armed groups’ presence on their land, community leaders and local human rights officials reported.[187]

In January 2021, the Attorney General’s Office told Human Rights Watch that it had open 61 investigations into threats against human rights defenders and other local leaders occurring in Tumaco since 2016.[188] However, a local senior prosecutor told us the number of such investigations is much higher.[189]

Bajo Cauca (Antioquia state)

Bajo Cauca, a region in the north of Antioquia state, comprises six municipalities: Cáceres, Caucasia, El Bagre, Nechí, Tarazá, and Zaragoza.

Several armed groups operate in Bajo Cauca, including the Gaitanist Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AGC), which emerged from the demobilization of right-wing paramilitaries; the Caparros, a splinter of the AGC formed around 2017; the ELN; and the so-called 18th Front and 36th Front, two groups that emerged from the FARC.[190]

Bajo Cauca has illegal gold mines and significant coca production.[191] All five armed groups are disputing territory, mostly to control coca crops, drug trafficking routes, and illegal gold mines— and to extort businesses.[192] Violence connected to armed groups’ disputes has increased since 2017, yielding a surge in the number of killings, threats, and forced displacement, as well as an expansion of violence to the neighboring state of Córdoba.[193]

OHCHR documented 15 killings of human rights defenders in Bajo Cauca occurring between 2016 and 2020, while the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office documented 34.[194] At least nine of the human rights defenders were members of Neighborhood Action Committees.[195] Other defenders killed included peasant and community leaders.[196]

Members of Neighborhood Action Committees are often at risk because both armed groups and government forces try to use them to learn what is going on in rural communities, and to communicate messages to the communities.[197] Consequently, armed groups often accuse them of collaborating with the opposing party or of failing to comply with their own “orders.”[198]

In four cases, armed groups apparently killed human rights defenders because they supposedly did not obey their “orders,” including to pay extortion or to refrain from supporting government forces or other armed groups.[199]

|

On February 16, 2017, members of the AGC killed Eberto Julio Gómez Mora, 47, president of a Neighborhood Action Committee in the municipality of Cáceres. Two men arrived at Gómez Mora’s house around 7 p.m. and shot him. In February 2018, two members of the AGC were sentenced to almost 18 years in prison for the homicide. The court concluded that they had killed Gómez Mora because the owner of the land he was working had not made an extortion payment.[200] |

|

Winston Manuel Cabrera, the 47-year-old president of a Neighborhood Action Committee in El Bagre, was killed on the morning of June 29, 2016, when a man approached him as he was leaving his house and shot him six times. On September 25, 2019, a court sentenced a member of the AGC to almost 18 years in prison for the homicide. The court concluded that the group had ordered him killed for being a “collaborator of the guerrillas.”[201] |

In at least eight other cases, armed groups killed human rights defenders who were involved in coca crop substitution plans, prosecutors told Human Rights Watch.[202] In three of the eight cases, evidence indicates that part of the reason for the killings was that the human rights defenders opposed armed groups’ extortion of the beneficiaries of coca substitution plans.[203] Armed groups extort beneficiaries, forcing them to pay roughly 10 percent of the COP 2.000.000 (US$ 518) that they receive every two months under the plans, according to prosecutors, judicial investigators, local human rights officials and community leaders.[204] In other cases, armed groups killed human rights defenders because of their support for or participation in the plans. A communal leader described the situation to us this way:

We want to support [coca] substitution, but they [the armed groups] do not let us, they threaten us, they do not let us leave our situation of poverty and, in addition, the government has failed us, so we do not have any other option than to sow [coca] or they will kill us or, worse, we will have to pack up and take our wife and children who knows where.[205]

|

Miguel Emiro Pérez Villar, 45, president of a Neighborhood Action Committee and a widely known promoter of coca crop substitution plans, was killed on October 22, 2017.[206] Around 1:30 p.m., three members of the Caparros entered Pérez Villar’s house, and one of them shot him. The court that convicted the shooter concluded that Pérez Villar was killed because he supported crop substitution plans despite an “order” from the Caparros that no one should take part in such plans.[207] The shooter was sentenced to over 20 years in prison. |

|

Eladio de Jesús Posso Espinosa, 38, a Neighborhood Action Committee member who participated in the coca crop substitution program, was killed on October 31, 2018.[208] Days before his killing, Posso Espinosa had received a coca substitution payment, which he still had in a pocket when he was found dead.[209] Judicial authorities believe he was killed because he refused to make an extortion payment.[210] “His homicide was a message” to other beneficiaries of the coca substitution program, an investigator said.[211] In November 2020, police killed Emiliano Alcides Osorio Macena, “Caín,” the then-commander of Caparros, for whom there was an outstanding arrest warrant for Posso Espinosa’s homicide.[212] |

Threats against human rights defenders have increased in Bajo Cauca since 2016, local human rights officials and prosecutors told us. Many are related to the implementation of coca crop substitution plans.[213] In some cases, armed groups tell civilians either to “comply [with their orders] or leave the area.”[214] In January 2021, the Attorney General’s Office told Human Rights Watch that it had opened 16 investigations into threats made against human rights defenders and other local leaders in Bajo Cauca since 2016.[215] But a local senior prosecutor and a judicial official indicated that the number of investigations is higher.[216] They said that many cases do not appear in the Attorney General’s Office records.[217]

Caguán (Caquetá state)

Caguán, an area in the southwestern state of Caquetá, comprises the municipalities of San Vicente del Caguán and Cartagena del Chairá.

The FARC guerrillas historically controlled big swaths of Caguán. The vacuum created by their demobilization was soon filled by FARC dissident groups known as the 7th, 40th and 62nd fronts.[218] Since mid-2017, the groups have coordinated their activities, including by agreeing on division of control over territory in Caguán, according to judicial investigators, analysts, and the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office.[219] Additionally, some credible reports indicate that fighters from the “FARC Second Marquetalia,” have recently arrived in some western parts of San Vicente del Cagúan bordering the state of Meta.[220]

The 7th and 62nd fronts today mostly operate in the southern area of Yarí, while the 40th Front operates in the municipality of San Vicente del Caguán.[221] Some sources believe that the three fronts are in the process of joining forces as the Jorge Briceño Front.[222] As part of their efforts to control the population and drug trafficking routes, the groups have engaged in serious abuses, including killings, child recruitment, and threats.[223]

Between 2016 and 2020, OHCHR documented 11 killings of human rights defenders in Caguán, while the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s office documented 14.[224] Most victims were members of Neighborhood Action Committees,[225] which, given limited government presence in the area, often conduct tasks normally associated with local officials.[226]

In three cases, human rights and judicial officials believe community leaders were killed because FARC dissident groups suspected them of links to former FARC guerrillas whose demobilization they consider a betrayal of their cause.[227]

In three other cases, human rights and judicial officials believe community leaders were killed because they did not comply with armed groups’ “orders,” including to pay extortion fees.[228] Like the FARC in the past, FARC dissident groups have distributed “manuals” establishing “rules” for civilians, local human rights officials and leaders of Neighborhood Action Committees told us, and have imposed severe punishments on those failing to comply.[229]

|

Yunier Moreno Jave, 47, a Neighborhood Action Committee member, was killed on the morning of September 8, 2019.[230] Two armed men appeared at his house and shot him six times.[231] Prosecutors, aid workers, and a local human rights official say the killers were apparently from the 62nd Front, which had accused Moreno Jave of selling marijuana, an activity the group has banned.[232] Since early 2019, the 62nd Front had circulated pamphlets announcing a “social cleansing” of people who broke their “rules,” including bans on selling drugs and stealing.[233] |

Leaders of Neighborhood Action Committees are frequently threatened and attacked because of their support for coca crop substitution plans.[234] As in other regions, the government has asked communal leaders in Caguán to complete a range of tasks required to implement the plans, including convening community meetings and communicating program details. Such tasks have increased their visibility, often increasing their risk.[235]

Armed groups also extort people participating in coca substitution plans, forcing them to pay a portion of the government benefits, a communal leader, a local human rights official and a member of a humanitarian organization told Human Rights Watch.[236] At times, the armed groups have coerced communal leaders into extorting beneficiaries on the groups’ behalf. “Those who refuse to do it are threatened or killed,” a communal leader who fled Caguán told Human Rights Watch.[237]

In January 2021, the Attorney General’s Office told Human Rights Watch that it had 212 open investigations into threats against human rights defenders and other local leaders ocurring in Caquetá since 2016, including 37 against leaders in Cartagena del Chairá and San Vicente del Caguán.[238] However, a prosecutor with detailed knowledge of the cases said the number of cases under investigation is over 400. Like others, the prosecutor said that many cases are not registered in the Attorney General’s Office records.[239] Human rights officials believe the number of threats is even higher, as many cases are never reported.[240]

Arauca’s foothills (Arauca state)

Saravena, Fortul, and Tame are municipalities in an area of the state of Arauca known as the foothills.

Two armed groups operate in Arauca: the ELN and the Martín Villa 10th Front, which emerged from the FARC. They enjoy significant power and exercise tight control over the population. Members have committed numerous abuses—including killings, kidnappings, sexual violence, child recruitment, and forced labor—to assert and maintain control.[241]

OHCHR has documented 10 killings of human rights defenders in Arauca’s foothills since 2016, while the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s office has documented 12 since 2016.[242]

According to judicial investigators and local human rights officials, armed groups killed three human rights defenders because they did not comply with “norms” the groups had established.[243] In three other cases, armed groups appear to have killed human rights defenders because they opposed child recruitment.[244]

|

Demetrio Barrera Díaz, a 32-year-old Indigenous leader, was killed around noon on February 24, 2019, in Tame. Two men approached on a motorbike, as he was riding his own motorbike with his sister. They asked his name and shot him seven times, as he responded.[245] His sister survived. Relatives and acquaintances of Barrera Díaz told judicial authorities that the FARC dissident group operating locally had asked him to send them Indigenous children to join their ranks—and had threatened him when he refused.[246] |

Armed groups have threatened human rights defenders in Arauca state. In January 2021, the Attorney General’s Office told Human Rights Watch that it had 53 open investigations into threats against human rights defenders in Arauca since 2016, including 9 against peasant leaders and 6 against Indigenous leaders.[247] However, a prosecutor with detailed knowledge of the cases and a human rights official said that the total under investigation was higher—and that many additional cases are never reported.[248] In many cases, armed groups threaten human rights defenders to ensure compliance with the groups’ “rules,” such as attending the groups’ meetings, paying extortion fees, or rejecting operations by the army.[249]

III. Government Action to Prevent Abuses and Protect Defenders

Colombia has a broad range of policies, mechanisms, and laws designed to prevent abuses against human rights defenders and other people at risk. However, implementation has been inadequate. Each of the policies and the shortcomings in implementation are discussed below.