Summary

They kept on having a friendly tone: ‘Yes, we’re looking for the right date, we’re more than happy to receive you, let’s look for a date.’ But they never said anything [regarding a solid date]. It was plausible deniability. I think what it shows is that there must be a lot to hide in Papua.

—Former UN Special Rapporteur Frank La Rue, describing the response of Indonesian officials to his 2012-13 request to visit Papua

Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo—popularly known as Jokowi—announced on May 10, 2015, that the government would immediately lift longstanding access restrictions on accredited foreign journalists seeking to report from the provinces of Papua and West Papua (referred to as “Papua” in the rest of this report). The president’s announcement sparked optimism that Indonesia would soon end its decades-long restrictions not only on foreign reporters, but also on UN officials, representatives of international aid groups, and others seeking to work in Papua.

The access restrictions—fueled by government suspicion about the motivations of foreign nationals in a region troubled by widespread public dissatisfaction with Jakarta and a small but persistent pro-independence insurgency—have limited in-depth reporting on Papua, have done little to prevent negative portrayals of Jakarta’s role there, and continue to be a lightning rod for Indonesia’s critics.

To date, however, President Jokowi’s welcome announcement has produced almost as much confusion as clarity. This report—based on interviews with 107 journalists, editors, publishers, NGO representatives, and academics—traces the history of access restrictions in Papua and developments since the president’s announcement. It shows that access restrictions are deeply ingrained, that parts of the government are strongly resisting change, and that a genuine opening of the provinces will require more sustained and rigorous follow-through by the Jokowi administration.

For at least 25 years and likely much longer, foreign correspondents wanting to report from Papua have had to apply for access through an interagency “clearing house,” supervised by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and involving 18 working units from 12 different ministries, including the National Police and the State Intelligence Agency. The clearing house has served as a strict gatekeeper, often denying applications outright or simply failing to approve them, placing journalists in a bureaucratic limbo. In some periods, the process operated as a de facto ban on foreign media in Papua. While the government appears to have eased its restrictions over the past decade, the process for foreign correspondents to acquire official permission to travel to Papua has remained opaque and unpredictable at best.

Bobby Anderson, a social development specialist and researcher who worked in Papua from 2010 to 2015, described the government’s clearing house screening of foreign media access to Papua as “illogical and counterproductive.”[1] He told us:

The clearing house system of consensus voting means any one person has veto power, which generally means that the opinion of the most paranoid person in the meeting carries the day. These restrictions fuel all manner of speculation about Papua: the notion that the Indonesian government has “something to hide” finds purchase. But the Indonesian government finds itself in the illogical position where they hear of inflammatory reporting and this actually makes them impose restrictions, and then those restrictions prevent good journalists from writing of the complexities of the place.[2]

President Jokowi’s May 10 announcement, while greeted by acclaim in some quarters, produced backlash in others. And it was not followed with an official presidential instruction, allowing room for non-compliance by government agencies and security forces opposed to the change. Various senior officials have since publicly contradicted the president’s statement. Even the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which said it had “liquidated” the clearing house, said that prior police permission is required for access to Papua and that foreign journalists should inform the ministry of likely sources and schedules.

Other parts of the government have pushed back more strongly. On August 26, 2015 Indonesia’s Ministry of Home Affairs announced a new, even more restrictive regulation that would have required foreign journalists to get permission from local authorities as well as the State Intelligence Agency (Badan Intelijen Negara) (BIN) before reporting anywhere in the country. President Jokowi revoked the rule the following day and Minister of Home Affairs Tjahjo Kumolo subsequently apologized to the president for the “confusion” created by the now-canceled regulation. But the willingness of some senior officials to even consider such measures is an alarming indicator of the disregard for media freedom among some elements of Jokowi’s government.

The problem is not only limited to the barriers that keep foreign journalists out of Papua, but also extends to the conditions facing those who get in, including surveillance, harassment, and at times, arbitrary arrest by Indonesian security forces. This is particularly true of journalists seeking to report on Papuan social or political grievances or on the practices of the military, police, and intelligence agencies.

While there are no comparable access restrictions for Indonesian journalists in Papua, they too—particularly ethnic Papuan journalists—face serious obstacles to reporting freely on developments in Papua. Reporting on corruption and land grabs can be dangerous anywhere in Indonesia, but national and local journalists we spoke with say that those dangers are magnified in Papua and that, in addition, journalists there face harassment, intimidation, and at times even violence from officials, members of the public, and pro-independence forces when they report on sensitive political topics and human rights abuses. Journalists in Papua say they routinely self-censor to avoid reprisals for their reporting. That environment of fear and distrust is magnified by the security forces’ longstanding and documented practice of paying journalists to be informers and even deploying agents to work undercover as Indonesian journalists. These practices are carried out both to minimize negative coverage and to encourage positive reporting about the political situation.

In addition to the obstacles facing journalists, staff members of international nongovernmental organizations, academics, and some foreign observers have been denied access to Papua. The security forces closely monitor the activities of international groups that the government permits to operate in Papua—those that seek to address human rights concerns get particular scrutiny. Government documents leaked in 2011 revealed that the government and security forces routinely consider foreigners in Papua to be assisting the armed separatist Free Papua Movement (Organisasi Papua Merdeka or OPM) through funding, moral support, and the documentation of poor living conditions and human rights abuses.

International NGOs that the government asserts are involved in “political activities” have been forced to cease operations, their representatives banned from travel to the region. Over the past six years, the Indonesian government has barred on-the-ground operations in Papua of organizations including the International Committee for the Red Cross and the Dutch development group Cordaid. Peace Brigades International (PBI), an international organization that promotes nonviolence and human rights protection in conflict areas, ceased its operations in Papua in 2011 due to what it described as unremitting government surveillance, harassment, and intimidation of its staff and volunteers. As a former Papua-based PBI representative told the story: “PBI staff were refused permission to work as the police and intelligence services launched an official investigation into the organization’s status. National Indonesian staff started to receive threatening phone calls.”

Government restrictions on foreigners have extended to United Nations officials and academics Indonesian authorities perceive as hostile. In 2013 the government rejected the proposed visit of Frank La Rue, then the UN special rapporteur on freedom of expression, because he insisted on including Papua on his itinerary. Foreign academics who do get permission to visit the region have been subjected to surveillance by the security forces. Those perceived to have pro-independence sympathies have been placed on visa blacklists.

***

The Indonesian government has legitimate security concerns in Papua stemming from periodic attacks, mainly targeting police and security forces, by OPM fighters. However, the threat from an insurgency does not provide a legal justification for the broad-brush and indefinite restrictions on freedoms of expression, association, and movement that the Indonesian government has long imposed on Papua. Any such restrictions, including those on non-nationals, must be based in law, narrowly construed in application and time to address a particular government concern, and proportionate to achieving a specific aim.

Past restrictions have far exceeded what is permissible under Indonesia’s international law obligations. The government should promptly and officially end its restrictions on travel to Papua by foreign media outlets and nongovernmental organizations, and take all necessary steps to ensure that Indonesians and foreign nationals alike who go to Papua are not subjected to threats, harassment, arbitrary arrests, and other abuses.

Removing access restrictions alone, of course, will not resolve the underlying political tensions and conflict in Papua or dispel the suspicions of Indonesian officials, but it is an essential step toward broader respect for rights: shining a light on Papua, not keeping it hidden from view, is the best way to ensure the region has a rights-respecting future.

Key Recommendations

Human Rights Watch Urges President Jokowi and Relevant Indonesian Authorities to:

- Issue a presidential instruction (Inpres) lifting restrictions on foreign media access to Papua and West Papua and direct all government ministries and state security forces to immediately comply with the order;

- Direct all government ministries and state security forces to end special restrictions on the operations of international nongovernmental organizations in Papua and West Papua, and to allow their staff free access the region;

- Instruct the National Police to immediately stop requiring accredited foreign correspondents to apply for travel permits, or surat jalan, to report from Papua and West Papua;

- Create a formal mechanism for foreign journalists to report instances of surveillance, harassment, and intimidation while reporting in Papua, and ensure a prompt response to such incidents;

- Stop placing undercover agents inside media organizations; and use informants only to obtain information on genuine criminal offenses, not as a form of harassment.

Methodology

This report is based largely on Human Rights Watch interviews with 107 journalists, editors, publishers, representatives of domestic and international nongovernmental organizations, and academics between April and October 2015. Among these were 80 interviews with individuals based in Papua in the cities of Jayapura, Manokwari, Sorong, Timika, and Wamena, and 27 with individuals based elsewhere, including in Jakarta as well as in Washington DC, London, Boston, Florence, Melbourne, and Sydney.

We interviewed a total of 16 current and former Indonesia-based foreign correspondents by phone or via email. We also interviewed Indonesian government officials—including Siti Sofia Sudarma, director of information and media at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Frank La Rue, former UN special rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression.

Interviews were conducted in English or Indonesian. Human Rights Watch informed those interviewed of the interview’s purpose and the issues that would be covered. They were informed that they could discontinue the interview at any time or decline to answer any specific question. No incentives were offered or provided to the interviewees.

Human Rights Watch wrote to Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo on August 18, 2015, and to General Badrodin Haiti, chief of the Indonesian National Police, on August 27, 2015, to inform them of our research findings and request feedback. At the time of publication we had not received a response to either letter. Copies of the letters can be found in the appendices to this report.

We have provided anonymity for many of the interviewees referred to in this report to protect their identity and to prevent possible retaliation against them, as indicated in the relevant citations. Real names have been used in cases where the incidents described have already appeared in the media.

Human Rights Watch also reviewed a range of published material, including news media, postings on Facebook, Whatsapp, and other Internet sites, as well as video clips relating to specific attacks on journalists. The report also draws on academic research, relevant reports, and articles published in Indonesia and international media.

Glossary

BAIS |

Badan Intelijen Strategis, or the military intelligence. |

|

BIN |

Badan Intelijen Negara, or the State Intelligence Agency |

|

ICRC |

International Committee of the Red Cross |

|

ICCPR |

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights |

|

Inpres |

Instruksi Presiden, or Presidential Instruction, a form of executive authority in Indonesia |

|

KNPB |

Komite Nasional Papua Barat, or the National Committee for West Papua |

|

Kopassus |

Komando Pasukan Khusus, Indonesia’s Special Forces Unit |

|

MFA |

Ministry of Foreign Affairs |

|

MHA |

Ministry of Home Affairs |

|

OPM |

Organisasi Papua Merdeka, or the Free Papua Movement, an armed pro-independence opposition group established in 1965. |

|

PBI |

Peace Brigades International |

|

PDIP |

Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle |

|

Surat Jalan |

An official government-issued travel document often required for access to Papua. |

|

SKP |

Papuan Catholic Human Rights Office of Justice and Peace |

|

UNHCR |

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees |

I. Political Strife in Papua and Fears of Foreign Influence

We never restrict journalists [from working on Papua]. We merely

manage them.

—Senior Commander Agus Rianto, National Police spokesman, May 2015[3]

The provinces of Papua and West Papua are in the easternmost part of Indonesia, more than 3000 kilometers from Jakarta.[4] The indigenous population in this region is Melanesian, ethnically distinct from other Indonesians, but also internally diverse, comprising over 300 distinct ethno-linguistic groups.

Recent years have seen a growing sense of “pan-Papuan” identity in response to the political opening that followed Suharto’s resignation, the still-strong military presence in the region, and the influx of non-Papuans; both “transmigrants” and economic migrants such as ethnic Bugis, Makassarese, and Torajans from southern Sulawesi.[5] This trend, however, has been counteracted by the carving up of Papua over the same period into two provinces and ever smaller administrative units within the provinces, the latter often defined along ethnic and clan lines.

The roots of the pro-independence movement and Papua’s small but persistent armed insurgency go back to the 1960s. Many Papuans in Indonesia assert they are victims of an historical injustice, robbed of the independence promised to them by their former Dutch colonizers. While the rest of Indonesia gained international recognition in 1949 following a war with its Dutch colonial rulers, the Dutch retained control of Papua into the 1960s. In the later years of Dutch rule, colonial officials in the region had been preparing Papua for independence by encouraging Papuan nationalism and by allowing the establishment of political parties and nascent institutions of state.[6]

However, rather than handing over control of the territory to Papuans, the Dutch instead agreed in 1962 to transfer authority over the territory to a United Nations Temporary Executive Authority, and then to Indonesia within a year,[7] on condition that by the end of 1969 an “Act of Free Choice” would be created to determine Papua’s future status.[8] Every adult Papuan would be eligible to participate in this act of self-determination.[9]

Instead of creating a process of universal suffrage, the Indonesian authorities decided to conduct the referendum through “representative” assemblies.

With the agreement of the Dutch and the United Nations, the so-called Act of Free Choice was created by Indonesia in July 1969, and the referendum was held in August with United Nations assistance.[10] The assemblies chose just 1,026 Papuans to participate.[11] The majority of the 1,022 who actually did participate were nominated by the Indonesian authorities and then voted on behalf of the rest of the population through eight regional councils.[12] According to one historian’s account, the Indonesian military used intimidation and coercion against the delegates.[13] The result was a unanimous vote for continued integration with Indonesia.

Indonesia has always maintained that, as a former part of the Netherlands East Indies, West New Guinea (as it was then named) was a legitimate part of Indonesia. Government officials have further claimed that the level of education was so low in the territory that the “one man, one vote” principle could not be applied.

The Act of Free Choice is considered by many Papuans to be a fraudulent basis for Indonesian annexation of the territory, and fuels the continuing demand for “historical rectification” and a new act of self-determination.

Militant opposition to Indonesian rule in Papua actually predates the Act of Free Choice, beginning with the Free Papua Movement (Organisasi Papua Merdeka, or OPM), Papua’s armed insurgency which was established in 1965, four years before Indonesia formally took control of the region.[14] OPM guerrillas have since maintained a low-level, armed guerrilla war targeting mainly members of the Indonesian security forces, but they also on occasion have targeted migrants and transmigrants[15] from other parts of Indonesia, as well as foreign workers and journalists.[16]

The conflict between Indonesian security forces and the OPM has fueled human rights abuses against the local population.[17] State security forces in Papua repeatedly fail to distinguish between violent acts and peaceful expression of political views. The government has denounced flag-raisings and other peaceful expressions of pro-independence sentiment in Papua as treasonous. Heavy-handed responses to peaceful activities have included serious human rights violations.[18]

The Indonesian government’s restrictions on access to Papua by foreign journalists, international nongovernmental organization representatives, and UN monitors are rooted in official fears of foreign influence on the region’s pro-independence movement.

As Michael Bachelard, an Australian former-Jakarta based foreign correspondent who has made two officially-approved reporting trip to Papua, has written:

To the extent that Indonesians think of Papua at all, they think of a huge, rich, empty land mass that’s vulnerable to exploitation and interference from foreign powers. The blame, they believe, rests on “ABDA”: Americans, British, Dutch and Australians. Australia, thanks to perceptions of its role in East Timor’s Independence and the noisy pro-Papua activist movement it hosts, is especially suspicious [to Indonesians].[19]

In the past four years, Human Rights Watch has documented dozens of cases in which prison guards and police, military, and intelligence officers have used unnecessary or excessive force when dealing with Papuans exercising their rights to peaceful assembly and association.[20] The government also frequently arrests and prosecutes Papuan protesters for peacefully advocating independence or other political change.[21]

More than 60 Papuan activists are in prison on charges of treason.[22] Human Rights Watch takes no position on the right to self-determination, but opposes the imprisonment of people who peacefully express support for self-determination.

The Origins of Restrictions on Foreign Journalists

Indonesian government restrictions on foreign media go back to the country’s first president, Sukarno (1945-1966), who required all prospective foreign correspondents to acquire journalist visas before traveling to Indonesia.[23] While the rigor and reach of the restrictions, in Papua as elsewhere in Indonesia, have varied with political developments in the country, Papua has been deemed off-limits to journalists more often than almost any other region.

Concerns with the role of foreign journalists in Papua existed even before Indonesia took control of the region in 1963. When making a speech supporting Indonesian control over West New Guinea in Yogyakarta on May 4, 1963, Sukarno lambasted “foreign journalists who wrote that West Irian people dislike Indonesia, that they prefer the Dutch.” Sukarno said that those journalists were “arbitrary in their writing.”[24]

Indonesian officials were particularly suspicious of the intentions of Australian journalists seeking to report from Papua. Former Indonesian Foreign Minister Ali Alatas (1988-1999) accused Australian media of being overtly sympathetic to Papuan independence in their reporting on the region in the 1960s:[25]

The Australian press in general was in favor of the Dutch position in Papua, and therefore many of them very often wrote articles that were critical of Indonesia and damaging of the Indonesian position and many of them had to pay with occasionally being declared persona non grata.[26]

The government further tightened its access restrictions to Papua by foreign correspondents in the run-up to and during the 1969 Act of Free Choice. The Indonesian government brought dozens of foreign journalists to Papua in a tightly controlled press tour in 1968 in which each journalist was accompanied by two military minders.[27] Those restrictions prompted the Jakarta Foreign Correspondents Club to lodge a formal protest with the Ministry of Information.[28] The Indonesian government limited foreign correspondents’ access to Papua to tightly controlled “guided tours organized through the military,” which intimidated potential sources into silence, according to journalist complaints.[29] In his book By-Lines, Balibo, Bali Bombings: Australian Journalists in Indonesia, Ross Tapsell, noting the impact of those restrictions after 1969, concluded: “Papua was effectively sealed off from the outside world.”[30]

During the “New Order” government of President Suharto (1965-1998), visas for foreign correspondents specifically excluded their access to “outer regions” of the country including East Timor, Papua and Aceh.[31] Access to those regions required a surat jalan (travel document) provided by either a high-ranking government official or the Ministry of Information.[32] During the 1960s and 1970s, foreign correspondents permitted access to Papua and other “outer region” conflict areas complained of the military’s “tactics of intimidating journalists.”

At some point during the New Order period, the process for vetting journalists seeking access to Papua was formally centralized in the clearing house described in the following section.

II. Vetting of Foreign Journalists by 12 Different Ministries

The Clearing House

Until President Jokowi’s speech in May 2015, Indonesia required that all Indonesia-based foreign correspondents seeking to report from Papua go through a labyrinthine “clearing house” process managed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.[33]

Although Human Rights Watch was unable to determine exactly when the clearing house process was established, Siti Sofia Sudarma, who formerly coordinated the process as director of information and media at the ministry, said it was created “long before” she began working at the ministry in 1991.[34] Many Indonesian and foreign journalists we spoke with believed that it, or some similar process, had been in effect for much of the New Order period.

Sudarma explained that the clearing house was an interagency committee of “18 working units from 12 ministries,”[35] including representatives from agencies and ministries such as the National Police, the State Intelligence Agency (Badan Inteliien Negara)(BIN), and military intelligence (Badan Inteliien Strategis)(BAIS).[36] She said that “national security” was the motivation and that Papua was only one of several conflict zones subject to the clearing house process over the past few decades.[37] Indonesia’s immigration law empowers the foreign ministry to prohibit foreign citizens from traveling to “certain areas.”[38]

The clearing house application process required journalists seeking to travel to Papua to provide an extremely detailed account of their reporting plans that former Australian correspondent Sian Powell described as “calculated to make it difficult [for foreign correspondents].”[39] Michael Bachelard, a former Jakarta-based correspondent for Fairfax Media from 2012 to 2015, described the onerousness of access application demands, which he said required journalists to violate their “duty to protect their sources and keep [sources’] confidentiality.”[40] He said:

[I] had to provide details of who [I was planning on] interviewing and when interviews would be conducted. Interviewees had to be willing to confirm interviews with the [foreign ministry] and [media] organizations had to confirm [interview] requests on their letterhead. It didn’t allow for any flexibility – putting the cart before the horse, so to speak – [because] interviewees had to be identified by their own foreign affairs department, though we may not even get permission to go.[41]

Reporting on “political and human rights issues” in Papua was typically forbidden.[42] A former Jakarta-based foreign correspondent granted a Papua access permit recalled that foreign ministry personnel made it clear he “couldn’t report on anything related to [Papuan] separatism.”[43] The Indonesian government approved the 2014 Papua access permit of Mark Davis, correspondent for Australia’s SBS News, on the condition that “I wouldn’t film or contact the armed resistance and that I would fairly represent the Indonesian government’s position [on Papua].”[44]

The government also imposed specific geographical restrictions on some of the Papua access permits it issues. Hamish Macdonald, world editor for Australia’s The Saturday Paper, said his Indonesian foreign ministry approval to travel to Papua in November 2013 for book research “gave approval to limited places — Jayapura and nearby areas. [I was] denied approval to visit [the towns of] Wamena, Timika, and Merauke — no explanation.”[45] And several journalists told us that official permission for foreign media to visit Papua’s PT Freeport Indonesia Grasberg mining complex in Timika is particularly difficult to obtain,[46] though this restriction is not absolute.[47]

The timing and basis for clearing house decisions was entirely opaque, with no reasons given for delayed or rejected applications. And foreign correspondents we spoke to who ultimately succeeded in obtaining permits reported application processing times ranging from one month to five years.

In a 2015 article, Bachelard explained that journalists take the permit requirement seriously in part because they do not want to jeopardize their other reporting:

As the Indonesia correspondent for The Age and The Sydney Morning Herald, I have a stay permit, a work permit, and a visa that allow me to live and work in Indonesia and travel to any of its 17,000 islands and dozens of provinces, but for one exception—West Papua.[48] For that, I need a special permission letter, a 'surat jalan.’ If I went there without such a letter, I’d jeopardize all my other permits, and possibly Fairfax’s permission to maintain a bureau in Jakarta at all.[49]

There are no publicly available statistics documenting the number of foreign correspondents who have applied for Papua access permits over the past few decades or how many received them. As detailed below, the evidence we were able to collect suggests that while obtaining official permission has almost always been difficult, the numbers have varied somewhat depending on policies and priorities in Jakarta.

A period in which the restrictions seem to have been eased were the years immediately following Suharto’s ouster in 1998. One correspondent who travelled to Papua on three separate reporting trips in 1999, 2000, and 2002, respectively, described the application process in those years as “always easy.”[50] “Under [former President] Gus Dur,[51] it was not a problem to get a ‘surat jalan’ to visit Papua.”[52]

Another foreign correspondent who received official permission to visit Papua in 2002 also described a fairly relaxed access regime. “The first thing was MFA [Ministry of Foreign Affairs] permission, but the real key was the police, a permission letter from there. That involved going to [National Police] headquarters a few times, filling-in forms. They put up barriers, but it was not impossible [to get access]. There were a lot of [foreign correspondents] going [to Papua] then.”[53] Another Jakarta-based correspondent who applied for Papua access at the end of 1998, however, wasn’t granted access until 2003. “[It was] one of those things in which you have outstanding requests [for access]. You’re not banging on the door every day, but you’re waiting for permission.”[54]

By 2004, the Indonesian government was again stringently applying Papua access requirements. TB Hasanuddin, an Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDIP) legislator who serves on the Indonesian parliament’s “Commission I” said that then President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, in power from 2004-2014, tightened the restrictions early in his first term.[55] “Under President SBY [Yudhoyono], access to Papua and Aceh were made stricter. His argument then was security. He did not want security problems in the two areas to be muddled with international reporting.”[56]

In February 2006, Indonesia’s then Minister of Defense, Juwono Sudarsono, openly defended restrictions on foreign media access to Papua. He was quoted as saying “Indonesian unity and cohesion would be threatened by foreign intrusion” and expressed concern and that reporters could be “used as a platform” by Papuans to publicize alleged abuses.[57] Juwono indicated that the ban extended to representatives of foreign churches and international nongovernmental organizations (INGOs).[58]

All of the foreign correspondents we spoke to who have applied for Papua access permits since 2003 described an unpredictable and opaque process that often resulted in access denials, delays, or a lack of response entirely. “You never got a ‘no,’ you just got a ‘not now,’” said a former foreign correspondent based in Jakarta from 2002 to 2006.[59] Indonesian political commentator Julia Suryakusuma attributed the lack of responsiveness of the clearing house to an intentional “‘go slow’ approach which enables the government to deny there is a ban on foreign journalists visiting Papua.”[60] The Ministry of Foreign Affairs justifies the often slow processing by claiming applicants “did not fulfill the administrative requirements properly” and failed to provide the necessary details of their planned Papua travels.[61]

Former Jakarta-based correspondent for The Australian from 2003-2006, Sian Powell, was skeptical about the official reasoning for the Papua permit system and its slow issuance process. “One of the lines [given by the foreign ministry] was that they wanted to protect foreign journalists from volatile elements in Papua, but they cared a lot more about keeping journalists away from insurgents there and native Papuans who were most disaffected and upset, particularly by Indonesian military incursions.”[62]

Former Jakarta-based correspondent for the Australian Financial Review Morgan Mellish summed up the frustrations of many of his peers when he wrote in 2007:

The difficulties for Western journalists start well before you arrive in Papua. To get a surat jalan requires the approval of Indonesia’s Department of Foreign Affairs (Deplu), the State Intelligence Body (BIN) and the Indonesian police. Our permits were among only a handful approved this year and took about six months to get. The vast majority of applicants are knocked back by Deplu[63] on the trumped-up grounds that the country’s easternmost province is too dangerous for journalists.[64]

A foreign correspondent based in Jakarta from 2005 to 2013 said that the foreign ministry’s lack of responsiveness to Papua access requests rendered the process a fruitless annual ritual. “We couldn’t go [to Papua]. We put in a request once a year…just for the sake of doing it, not expecting it to be granted. Almost everyone [in the foreign press corps] did it. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs just didn’t answer.”[65]

In 2013, Australian Associated Press correspondent Karlis Salna was able to force a permit decision, but only after a series of failed attempts. “[Salna] applied for entry a dozen times in two years, but it wasn’t until he texted the Indonesian foreign minister’s spokesman to say he was visiting West Papua even without a permit and that the government could deal with the fallout if he was arrested that Salna was allowed in.”[66]

Some foreign correspondents have reported that a second easing of the clearing house approval process for Papua seems to have started in 2013, a trend reflected in official foreign ministry statistics: data show that the ministry approved 5 of 11 such requests in 2012, 21 of 28 in 2013, and 22 of 27 in 2014. But even in the very recent past, obstacles have remained in place.

Rohan Radheya, a Dutch freelance photojournalist who applied in The Hague for a journalist visa to Papua in July 2014, said that although the Indonesian embassy informed him that the approval process was “around two weeks,” officials never responded to his application.[67] Radheya said that his case is not an outlier. “I know many journos who got ignored [by Indonesian visa issuance offices], and they simply never heard something again [after submitting a Papua access application].”[68]

A Europe-based documentary film maker who submitted an application in January 2015 told Human Rights Watch that his approval has been plagued by months of unexplained delay by the Indonesian embassy processing the application. On July 9, the journalist told Human Rights Watch that seven months later, there is still “no word” from the Indonesian authorities on the status of her application.[69]

In 2014, then Minister of Foreign Affairs Marty Natalegawa implicitly acknowledged the continuing restrictions, stating that while the government supported greater access by journalists and nongovernmental organizations to Papua, government concerns about their safety made lifting access restrictions problematic.

Natalegawa’s claim is one that most foreign correspondents have heard repeatedly.[70] As one journalist told us: “At every government press conference we would ask ‘Why can’t [foreign] journalists go to Papua?’ and they always said it was unsafe for us to go.”[71] Although the government has some reason to be concerned about the safety of foreign citizens in Papua, those concerns do not warrant the convoluted and restrictive bureaucratic process that Jakarta has long imposed. While there have been serious attacks on foreigners in Papua, they have been infrequent.[72]

President Jokowi’s Commitment to Lifting the Restrictions

Beginning today, Sunday, I allow the foreign journalists if they want to go to Papua just like the other regions.

—President Jokowi, after attending a grand harvest in Merauke district, Papua, May 10, 2015.[73]

On May 9, Indonesian President Jokowi declared a complete lifting of restrictions on foreign media access to Papua and, as indicated in the quote above, he delivered on that commitment on the following day.[74] He then reiterated the message during his first annual state of the nation address on August 14.[75] This change was of a piece with a larger initiative by Jokowi, signaled in his campaign and early on in his tenure as president, to take a new approach to Papua. Other measures have included planned new investments in infrastructure, economic development projects, and release of some political prisoners.

While Jokowi’s announcements on media access marked a symbolic fulfillment of a promise he made as a presidential candidate in June 2014 to open Papua to both foreign journalists and international nongovernmental organizations,[76] he did not provide details or put the change in writing via a presidential instruction.[77] And, since his announcement, various Indonesian government officials and senior commanders of the country’s security forces have made a series of confusing or contradictory statements that suggest a lack of a coherent, unified policy on lifting foreign media access restrictions to Papua.

Then Coordinating Minister for Political, Legal and Security Affairs, Tedjo Edhy Purdijatno, appeared to contradict Jokowi’s announced lifting of those restrictions on May 11. Tedjo asserted that foreign correspondents would continue to require special access permits to Papua and that the government would continue to “screen” foreign journalists seeking that access.[78] Tedjo also questioned the integrity of foreign media reporting of Papua, which he said “describes that the situation [in Papua] is full of [human rights] violations. I think it is not true.”[79]

On May 12, National Police spokesman and Senior Commander Agus Rianto asserted that the government would continue to restrict foreign correspondents’ Papua access through an entry permit system.[80] Rianto justified the need to maintain foreign media access restrictions to Papua to prevent foreign media from talking to “people who opposed the government” as well as to block the access of “terrorists” who might pretend to be journalists as a means to travel to Papua.[81] Rianto did not elaborate.

On May 19, the then commander of the Indonesian Armed Forces, General Moeldoko, stated that foreign media would continue to require Papua access permits from the clearing house.[82] Moeldoko warned that the Indonesian government would expel any foreign journalists whose Papua reporting is perceived by the government to “undermine our government and state” or whose reports “contain defamation that triggers unrest.”[83] On June 22, Moeldoko told reporters that the military was considering appointing military escorts for foreign media who travel to Papua.[84] Moeldoko justified the possible deployment of those military guards as necessary to “guide and protect [journalists] in case any dangerous situation arises,” without elaborating.[85]

On May 26, Tedjo told reporters that a team including Indonesian military and National Police would continue to tightly monitor foreign journalists who report from Papua.[86] Tedjo defended the agency’s policy by asserting that, “We aren’t spying on them [the journalists]. We’re simply monitoring their activities.”[87] Tedjo also asserted that the clearing house, which approves or rejects foreign media access applications to Papua, was essential “to preserve national interests and national sovereignty.”[88]

That same day, Minister of Defense Ryamizard Ryacudu warned that foreign media access to Papua was conditional on an obligation to produce “good reports.”[89] Ryacudu did not precisely define “good reports,” but he explicitly equated foreign journalists’ negative reporting Papua with “sedition” and threatened expulsion for any foreign journalist whose reporting displeases the government.[90]

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs has added to the confusion about the government’s official policy on foreign media access to Papua. On June 17, the director general of information in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Esti Andayani, announced that the government had “abolished” the clearing house.[91] Andayani did not elaborate on precisely when the government had abolished the body or what access control procedures, if any, had replaced the clearing house system.

On June 22, Minister of Foreign Affairs Retno Marsudi denied that the government had ever systematically barred foreign media from access to Papua:[92]

The refusals [of foreign media access] in 2014 were made because of incomplete procedures or warnings regarding the security situation in the areas in Papua where they wanted to go. Otherwise, from the data we have, there have been no deliberate actions to restrict foreign journalists’ access into the province.[93]

Marsudi supported that assertion by stating that the government had approved a total of 22 foreign media access permits to Papua in 2014 and that there had been “nearly no refusal” of such applications.[94] Marsudi added that foreign correspondents “should have no problem visiting Papua” as long as they “fulfill all required procedures,” without specifying those procedures or whether they continued to require approval of the ministry’s clearing house.[95]

On August 7, Siti Sofia Sudarma, director of information and media in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, told Human Rights Watch that the government had “liquidated” the clearing house in line with President Jokowi’s May 10 directive.[96] Sudarma said that Indonesia-based accredited foreign correspondents “could [now] go to Papua freely, without notifying the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.”[97] Sudarma said that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs would only continue to screen the applications of foreign-based journalists applying for accreditation to report from Indonesia based on the requirements of its Immigration Law.[98] Article 8 of the Immigration Law obligates all foreign nationals entering Indonesia, including journalists, to have a valid entry visa.[99]

However, the apparent abolition of the clearing house has not eliminated the need for foreign correspondents to apply for special permission to visit Papua. According to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, all Indonesia-based accredited foreign correspondents still need to apply for and receive a surat jalan (travel document) from the National Police’s Security Intelligence Agency before traveling to Papua.[100] This requirement is based on Indonesia’s police law, which states that that the police have the obligation to “supervise” foreign citizens in Indonesia in coordination with “related institutions.”[101]

According to Sudarma, “Theoretically, all foreigners who want to travel from Jakarta to other cities, they should ask for a surat jalan. But the police selectively enforce the surat jalan policy [and] now it is only Papua [that requires a surat jalan].[102] The National Police have not responded to requests from Human Rights Watch for details about the permit application process.

On August 26, 2015, the Ministry of Home Affairs announced a new regulation that would have required foreign journalists to get permission from local authorities as well as the State Intelligence Agency before doing any reporting in the country.[103] President Joko Widodo revoked the rule the following day and Minister of Home Affairs Tjahjo Kumolo subsequently apologized to the president for the “confusion” created by the now-canceled regulation.[104] But the willingness of some senior officials to even consider such measures is an alarming indicator of the continuing confusion and apparent disregard for media freedom among some elements of Jokowi’s government.

There are indications that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is continuing to require accredited foreign correspondents to apply for Papua access permits. The Jakarta Foreign Correspondents Club has not compiled any statistics of its members’ efforts to access Papua since May 10.[105] However, a Jakarta-based foreign correspondent showed Human Rights Watch a copy of correspondence with the ministry from July 2015 in which an official from Sudarma’s Information and Media Directorate had informed the journalist that access to Papua required both a surat jalan from the Police Security Intelligence Agency as well as a “letter of notification” to the directorate specifying “your purpose, time and places of coverage in Papua.”[106] The ministry did not specify how long the application process would take and why the ministry was still regulating accredited foreign media Papua access more than two months after President Jokowi announced a lifting of such restrictions.

Marie Dhumieres, a Jakarta-based French correspondent, got a police permit to go to Papua in September 2015. On October 1, she flew from Jayapura, Papua’s provincial capital, to Pegunungan Bintang to interview pro-independence activists from the West Papua National Committee. She returned to Jakarta the following day, but a week later the police detained one Papuan activist who had travelled with her and two of his friends, and questioned them about Dhumieres.[107] She expressed her dismay about those arrests by tweeting: “So Mr @jokowi, foreign journalists are free to work anywhere in Papua but the people we interview get arrested after we leave?”[108]

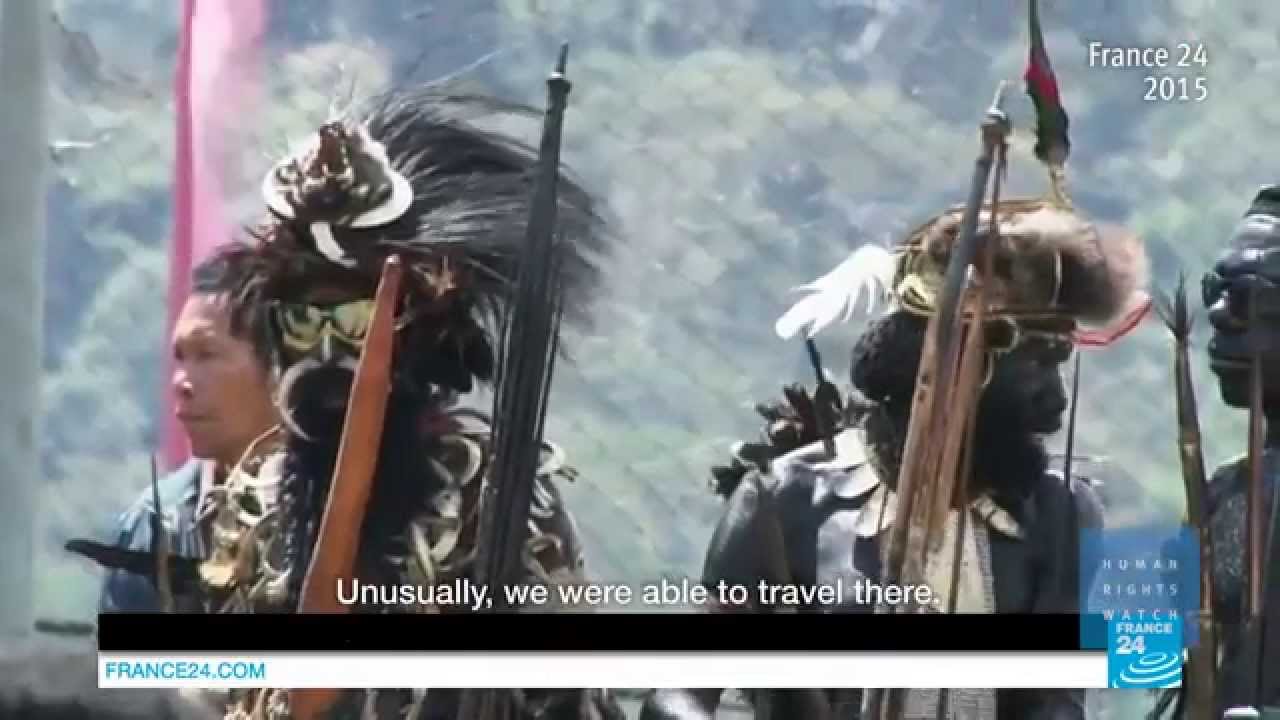

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs is also giving mixed signals to foreign-based reporters seeking Papua access who are applying for journalist visas from outside of Indonesia. Cyril Payen, the Bangkok-based correspondent for France 24 television, said that the Indonesian embassy in Bangkok processed his application for a journalist visa to visit in 15 days and that his reporting trip occurred without any harassment or interference.

They gave me a press visa and the embassy said you don't need to go to police, or go to immigration [when you are in Papua].” Whether I was lucky or not, I don't know. They really opened up. [The embassy staffer] said “Just go, there are no more restrictions.”[109]

However, another foreign journalist who has been trying for several months to get the Indonesian embassy to issue him a visa to report from Papua said that the embassy has imposed lengthy delays on the processing of his visa application. He said:

“We submitted everything that was required according to guidelines I was emailed from the embassy months ago. This included a letter of recommendation for our visit and interview from a leading provincial official in Papua.” Eight days later, when he called the Indonesian embassy, “[The Indonesian staff] muddled around a strange half hour discussion before revealing that we needed to provide more letters of recommendation from our intended interviewees, plus to reveal who our fixer would be.”[110]

Johnny Blades and Koroi Hawkins of Radio New Zealand made a reporting trip to Papua in October 2015 after a months-long application process through the Indonesian embassy in Wellington. Blades attributed that delay to bureaucratic confusion over President Jokowi’s policy to lift foreign media access restrictions. “It's still not clear that various wings of government understand the role that journalists are supposed to fill. I detected a kind of suspicion among various officials that foreign journalists are agents tasked with destabilizing Papua region,” said Blades.[111]

III. Surveillance, Harassment, and Intimidation of Foreign Correspondents in Papua

Foreign correspondents who were actually granted access to Papua are often targets of surveillance, as well as occasional harassment and intimidation by government officials and security forces personnel. Not all correspondents who are able to report from Papua experience such abuses: for example, one former Jakarta-based foreign correspondent who received permission for a reporting trip in 2006 said that permission did not require her to have any contact with Papua-based security forces.[112] However, nearly all of the others we spoke with say they did.

Morgan Mellish, a former Jakarta-based correspondent for the Australian Financial Review, described how security forces and intelligence agents obstructed him and two colleagues during their September 2006 reporting trip to Papua. The Indonesian government had granted Mellish Papua access to report on Papua’s resource extraction industries. Mellish wrote that he travelled to Papua with ABC Jakarta correspondent Geoff Thompson and The Australian’s Jakarta correspondent Stephen Fitzpatrick. They obtained their travel permits in Jakarta. “But this didn’t stop the overzealous and at-times thuggish secret police from trying to stop us reporting at almost every turn. There may be some good will in Jakarta toward solving West Papua’s problems, but it’s clear the security forces on the ground remain a law unto themselves,” he wrote.

“All three of us were tailed by plainclothes police and threatened for attempting to interview human rights activists and Papuan community leaders… in Timika, I received similar treatment. I was having lunch with two Freeport employees when an intel[ligence officer] marched in and aggressively demanded to know who we’d talked to and to see our notes. To try and resolve the tension, my assistant offered to photocopy several pages of notes from a press conference with the Papuan governor. A Freeport employee later apologized and said the company had little control over the intels,” he said.[113]

The foreign ministry requires some foreign correspondents who are granted Papua access permits to be escorted by a minder from the State Intelligence Agency (Badan Intelijen Negara)(BIN). The foreign ministry justifies BIN minders for foreign correspondents in Papua as “mainly for their own security.”[114] This rule is by no means not absolute. The government did not require six of the former foreign correspondents Human Rights Watch interviewed who visited Papua on government access permits to have government escorts. Others, including Michael Bachelard, former Jakarta correspondent for Fairfax Media, said that the official minder that the foreign ministry sought to impose on his January 2013 Papua reporting trip never showed up.[115] On Bachelard’s second Papua reporting trip in November 2014, he again had no official minder.[116]

Kresna Astraatmadja, an Indonesian television producer who worked on a French reality show filmed on a small island near Raja Ampat, Papua, said that the conditions of foreign ministry permission to film on the island obligated the production crew to accommodate two BIN officials to monitor their activities. “[The intel officers] did nothing but sit down the whole day. I was busy with the production [so] I rarely saw them. Later I learned that the two [agents] had left the island earlier. Maybe they were bored to death on that small and isolated island.”[117]

Other journalists are not so fortunate. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs required one foreign correspondent, who travelled to Papua in 2008 to report on the region’s HIV-AIDS epidemic, to have a military intelligence official accompany him for the entirety of his six-day trip. Although the journalist successfully evaded his minder on numerous occasions in order to secure interviews with sources whom his minder might object to, such as a local religious leader, the minder’s presence had a chilling effect on the journalist’s reporting:

One of the conditions [of Papua access] was that we had to have an intel guy with me and pay for his accommodations, transport, and food. He was with me the whole time. He wasn’t too bad. He was actually pretty incompetent, getting close to retirement. But his presence limited what I could do. He would listen in on conversations and create an uncomfortable environment [in interviews]. Just because my minder was there, it spooked everybody.[118]

The foreign ministry’s Papua access approval for Hamish Macdonald of Australia’s The Saturday Paper trip to Papua in December 2014 with an Associated Press correspondent included two reasonably discrete official escorts. “[The minders were] two diplomats accompanying us to ‘keep watch.’ They stood back [and] let us draw our own conclusions.”[119]

However, the absence of an official minder is no guarantee that foreign correspondents will not encounter surveillance, harassment, or intimidation by plainclothes or uniformed security forces and intelligence personnel while reporting in Papua. Another former Jakarta-based foreign correspondent, who travelled to Papua without an access permit on account of the difficulties in securing official permission, told Human Rights Watch how plainclothes security personnel followed him while he was doing interviews in Timika on for a business-related story.[120] Mark Davis, correspondent for Australia’s SBS News, similarly described how during his officially approved 2014 trip to Papua to report on the region’s political situation, he was “constantly followed and filmed by seen and unseen [plainclothes military] forces.” He recorded one of them on a motorcycle, following and stopping in accordance to his car’s movement.[121]

A former Jakarta-based foreign correspondent from 2006-2009, who received official permission to travel to Papua in September 2006 to do a package of stories on social and political conditions there, described the police response after he and his television crew had filmed a pro-Papuan independence ceremony about an hour outside of the Papua provincial capital of Jayapura:

On the way back to Jayapura, we were pulled over by police and quite aggressively interrogated before being let go. We were followed [by police] once we arrived in Timika. [We] arrived at the hotel and within an hour, the cops arrived. We had dubbed the footage, hid the other tape and handed them our generic tape. We were taken to the police station for three to four hours. Our fixer was taken to a different room. We phoned the Australian Embassy…and [the police] let us go. We then returned to Jakarta [and] eventually got the film out of Papua.[122]

Government surveillance of foreign correspondents in Papua also extends to the information on their laptop computers. A former Jakarta-based correspondent who visited Papua with an official access permit in 2003 to do a business-related story, noticed that security forces were “keeping tabs on me” when he identified what appeared to be police “goons” in the lobby of his Jayapura hotel, monitoring his movements:[123]

In Jayapura I came back to my hotel and found my laptop had been damaged. It was clear I was being monitored. Somebody had tried to open and turn on the laptop, and it had been damaged. It was nothing like what would have resulted from a [room] cleaner picking it up. It was obviously different from that.[124]

Arrests and Deportations of Journalists

The onerous access restrictions and the risks of surveillance, harassment, and intimidation by security forces tasked to monitor the movements of known foreign correspondents prompts some journalists to enter Papua without official entry permits. A former Jakarta-based foreign correspondent, who made two such unaccredited reporting trips in 2000 and 2002, was able to freely report on a range of social, political, and economic topics without interference or reprisal.[125] But since 2003, Jakarta-based accredited foreign correspondents rarely take the risk of trying to access Papua without an official permit due to fears of “immediate expulsion” if detained and of run-ins with Papuan security forces.[126]

One journalist went to Papua in 2011 without a permit, seeking to report on a strike at the Freeport mine complex in Timika. The journalist disregarded Indonesian government regulations requiring journalists to have official permission to travel to Papua because “foreign correspondents [in Jakarta] had told me that my struggle to get permission [to visit Papua] would be impossible.”[127] His presence in Timika during the miners’ strike prompted scrutiny by local police. He told Human Rights Watch:

I flew first to Jayapura, hung out for a day, then went to Timika…. I told everyone I was a British travel agent who runs exotic bespoke tours. I [later] got pulled over by the police. They took me to the police station. I was there for an hour. The preconception [among Timika police] is that foreigners don’t come here unless they work for Freeport. So if you don’t work for Freeport, why are you here? They didn’t push hard. They could have Googled my name [to determine if I was a journalist] but they didn’t. They didn’t ask who I know [in Timika], made no effort to ask about my contacts and there was no sustained interrogation.[128]

Other journalists who have entered Papua without the appropriate travel document have been arrested, and deported. In September 2006, police in Papua arrested, interrogated, and subsequently expelled a five-person Australia Channel Seven television crew for attempting to report without accreditation.[129] In March 2010, police in Jayapura detained[130] and subsequently deported two French journalists, Baudouin Koenig and Carole Lorthiois, for working without an official Papua entry permit.[131]

More recently, police arrested and detained Thomas Dandois and Valentine Bourrat, French journalists producing a documentary for Franco-German Arte TV, on August 6, 2014, in Wamena on suspicion of “working illegally” in Papua without official media accreditation.[132] That same day, police also detained Areki Wanimbo, the head of a Papuan indigenous people’s council in Wamena, whom the two French journalists had interviewed that day.[133]

On August 14 the Papua police spokesman, Sulistyo Pudjo, suggested that the two journalists would face “subversion” charges for allegedly filming members of the armed separatist Free Papua Movement (OPM). Pudjo alleged that the Arte TV journalists “were part of an effort to destabilize Papua.”[134]

On October 24, 2014, a Jayapura court convicted Dandois and Bourrat of “abusive use of entry visas” and released them on October 27 based on time-served.[135] The arrest and prosecution of Dandois and Bourrat prompted a rare public challenge to Papua access restrictions for foreign media by the Jakarta Foreign Correspondents Club. On September 29, 2014, the JFCC issued a statement that described those restrictions as “a sad reminder of the Suharto regime, and a stain on Indonesia’s transition to democracy and claims by its government that it supports a free press and human rights.”[136] The Wamena district court acquitted Areki Wanimbo on May 8, 2015, due to lack of evidence.[137]

IV. Abuses against Indonesian Journalists in Papua

[Police] were curious to see an ethnic Papuan taking photos of the protest. They beat me and asked questions later.

–Octavianus Pogau, chief editor of the Suara Papua news portal, Jayapura, May 2015[138]

Harassment and Intimidation by Officials, Security Forces, and Pro-Independence Activists

Indonesian journalists, including those who are based in Papua, are generally not limited by the access restrictions that hinder foreign correspondents’ reporting.[139] Nonetheless, Indonesian journalists in Papua, particularly native Papuans, are still vulnerable to harassment, intimidation, and violence from government officials, security forces, and pro-independence activists.

Rohan Radheya, a Dutch freelance journalist who has made four officially unauthorized reporting trips to Papua in the last two years, said that concern about the Papua access restrictions for foreign correspondents should not overshadow what he describes as daily “threats and intimidation” against local journalists.[140] “They are good journalists, they have a good network and some of the [Papuan journalists] I met, they have bullet holes, they have been stabbed by [Indonesian security] forces, and they continue to wake up in the morning and just go about and do their jobs.”[141]

Ross Tapsell, who chronicled decades of Papua access restrictions on foreign media in his 2015 book By-Lines, Balibo, Bali Bombings: Australian Journalists in Indonesia, echoed concerns about the serious occupational hazards facing local reporters in Papua:

It’s important to remember that many local Papuan journalists face threats and intimidation from security forces on a regular basis simply for doing their job. It is difficult for them to report on issues involving local politicians, human rights, and the role of security forces in the region. There are numerous stories that simply can’t be published in the local press. So let’s not forget local journalists, and more broadly the restrictions on freedom of expression in the Papua provinces.[142]

The Pacific Journalism Review reported a “significant escalation” in threatening actions by elements of the security forces toward journalists in Papua in 2011.[143] These included harassing messages and death threats via mobile phone text messages and voice mails.[144]

Papuan journalists told Human Rights Watch that harassment and intimidation by Indonesian security forces is routine. Although that harassment and intimidation is often via anonymous text messages and phone calls, many journalists say there is evidence that elements of the security forces are responsible. Victor Mambor, the Papua provincial chairman of Indonesia’s Alliance of Independent Journalists and editor of the Tabloid Jubi, perhaps the leading online source of news on Papua, described such harassment as designed to undermine journalists’ confidence.

I cannot count how many SMS, email, or social media [threats] that I have received. The accusations are always that I am a foreign agent. The threat is often to kill me, or to attack my office. Or burn my office. That’s why I often change my cell phone numbers. I have lost count of how many times. Maybe 300 times? I always think [the harassers] want to disturb me mentally. I always delete their threats. I don’t want to be influenced [by them].[145]

Duma Tato Sando, the managing editor at Cahaya Papua, a small daily newspaper in Manokwari, said that security force personnel will often pressure him to kill stories that document human rights abuses.[146] He said:

For me, covering human rights abuses in Papua is not easy. In Manokwari, usually an intelligence officer will call and ask that the news story to be “pending.” They like to say, “Please do not publish it.” Sometimes they even ask me for background information, such as places, names, times [of incidents of human rights abuses] because they do not know that their own men did the beating or the shooting. I have too many cases [of such harassment] to recall one-by-one. I got most calls from Kodim and BIN offices.[147]

Journalists in Papua also report harassment and intimidation by security forces as a reprisal for unflattering media coverage. Patrix Barumbun Tandirerung, deputy publisher of Cahaya Papua, said the local assembly speaker in the Teluk Wondana regency threatened to kill him for a story that criticized the work habits of assembly members and compared the hygiene of their facilities to that of an “animal den.”[148]

Veronica Asso, a Wamena-based blogger, reported on what she considered to be a suspicious roadside checkpoint she encountered in downtown Wamena on May 19, 2015. The roadblock was manned by two men wearing shorts claiming to be police officers. The two men, who were in fact police officers, impounded Asso’s motorcycle for not having proof-of-ownership papers on her person. She said:

I wrote about that incident and published it on my blog on March 20. It was just a regular blog, telling my audience about the incident. One hour later [a fellow journalist] called me and told me that the Wamena chief traffic officer wanted to see me in the police precinct. I was surprised. They made me wait for two hours in the police waiting room. Around 20 officers taunted and bullied me. They called me the “indigenous woman” who dares to write bad things about the police. A policewoman suggested to her friends that I be charged and jailed. After two hours, the head of the traffic desk asked me why I did not confirm my blog with him first. [He] admitted that the two men [from the roadblock] were his officers. He said nothing about [their failure to wear] uniforms. But he basically asked me not to continue writing about that case. I decided not to write [about it] again. I also told [fellow] journalists that I would temporarily pause my blogging. Wamena is a small town. Even a blog about policemen could get me in trouble.[149]

A threat of violence from a State Intelligence Agency (BIN) officer in 2014 prompted Jo Kelwulan, then chief editor of Tabloid Noken, a newspaper owned by the Papuan Customary Council, to end publication of his popular weekly newspaper. The officer did not mention the specific reasons for the threat, but Kelwulan believes the Tabloid Noken’s coverage emphasis on land-grabbing, human rights abuses, and impunity among security officers had prompted the officer to try to close the paper.[150] The threat succeeded. Kelwulan shuttered Tabloid Noken in November 2014. Kelwulan said:

[The intelligence officer] told my uncle in a very serious tone to advise me to stop publishing Tabloid Noken. He said that the tabloid had reached the point where [security forces] could not prevent [violent] acts against the tabloid and against me personally. I discussed this with some close friends. We thought that it would be better to cease publishing Tabloid Noken rather than to face something unexpected. The BIN did not specifically mention stories that they had objected to. My guess is that they were not happy because we were publishing stories related to the views popular among many Papuans.[151]

Octavianus Danunan, publisher and chief editor of Radar Timika, an Indonesian newspaper owned by the Jawa Pos group in Surabaya, described threats of physical violence to himself, his staff, and his newspaper facilities as a constant worry. He said there were multiple sources of serious harassment and intimidation:

[There are] threats of being killed, being burned. The threats could come from rogue elements of the military, the police, the OPM guerrilla fighters, and many thugs as well as [military] deserters in Timika. This is a place where you don’t know if the man entering your front door has a gun inside his bag or under his shirt. Freeport workers once threatened to burn this office. It was a serious threat.[152]

Security forces are not the only sources of intimidation and harassment against journalists in Papua. Representatives of the pro-independence National Committee for West Papua (Komite Nasional Papua Barat) (KNPB) also have a reputation for trying to derail media coverage of KNPB events. KNPB organizers of a pro-independence protest in Manokwari in 2014 attempted to prohibit media coverage of their event and reportedly tried to assault a Radio Sorong journalist at the scene.[153] In August 2014, KNPB activists attempted to ban journalists from covering the funeral of murdered KNPB activist Martinus Yohame.[154]

When the Suara Papua news website in Jayapura chose not to cover a KNPB press conference in April 2015 on the arrest of three KNPB activists in Nabire, the paper’s chief editor received a menacing call from a senior KNPB leader who “asked me about whether I am on the Papuan side or the Indonesian [government’s] side.”[155]

Ika Sanduy, a camerawoman for Papua Barat TV, a state-owned station, said that KNPB activists are particularly suspicious of who they perceive to be non-native Papuan journalists who cover KNPB events. “It’s difficult for someone like me,” she said. “I am neither a full-blood Papuan nor an Indonesian. I am having problems from both [pro-independence and pro-government] sides.”[156]

Violence against Journalists

In recent years, several Papuan journalists have died violently in circumstances that raise questions about possible complicity by economic interests threatened by their reporting, security forces, or some combination of both. The naked body of Ardiansyah Matra’is, who worked for the Tabloid Jubi, was found on July 30, 2010, handcuffed to a tree in the River Gudang Arang, bearing signs of torture.[157] Matra’is had reported on sensitive issues including corruption, illegal logging, and unresolved cases of human rights violations in Papua. Shortly before his killing he had received threatening text messages that warned him to “be prepared for death.”[158] Despite the evidence that he had been murdered, Papua police closed the investigation into Matra’is’ death in September 2010, concluding that he had likely committed suicide.[159]

Patrix Barumbun Tandirerung, the deputy publisher of the Cahaya Papua, said violence against his reporters from a variety of sources[160] is a constant concern:

I have to deal with violence against our reporters almost every month. Some cases only involve verbal threats. Some are quite serious. The perpetrators have ranged from soldiers to clan leaders.[161]

Some attacks by government officials on journalists in Papua are notable for their brazen nature. On May 9, the regent of Biak Numfor, Thomas Ondy, physically attacked Fiktor Palembangan, a journalist with the Cenderawasih Pos newspaper in Jayapura, a subsidiary of the Surabaya-based Jawa Pos group that is generally viewed as closely aligned with the Indonesian government. Palembangan had reported on a fire that destroyed the regency’s market.[162] Ondy later apologized for the assault and justified his actions as a reprisal for Palembangan’s alleged failure to “mention Biak authorities’ efforts to extinguish the fire.”[163]

Journalists who cover public protests are particularly vulnerable to assaults by both uniform and plainclothes security forces. Octavianus Pogau, chief editor of the pro-independence Suara Papua news portal in Jayapura, described being assaulted by officers while covering a KNPB protest in Manokwari in 2012:

On October 23, 2012, some plainclothes police officers assaulted me when [I was] covering a student protest outside the University of Papua campus in Manokwari. I saw some of [the police officers] earlier [behind] the police barricades. They are police intelligence people. I was trying to take photos [of the protest] when those officers approached me. Those intel police, one of them holding a gun, cornered me near a kiosk, one of them saying: “What are you doing here?” Others [policemen] held my neck and hands. I said I was taking pictures. They immediately hit me. I told them I was a journalist. But they kept hitting me. I was bleeding from my nose and my head.[164]

Pogau said that social media coverage of his assault prompted an apology by the Manokwari police chief. Pogau says he did not file charges against his attackers due to his unfamiliarity with the procedures of doing so and also because physical signs of his injuries had healed by the time he had a medical examination.[165]

The security forces in Papua have also targeted female journalists. Aprila Wayar, the chief editor of Tapa News in Jayapura, which promotes ethnic Papuan views, told Human Rights Watch that police assaulted her in 2015 while covering a KNPB rally.[166] Wayar said that her efforts to file criminal charges against her attacker were unsuccessful and that police have failed to investigate the assault:

On August 15, 2014, I was covering a KNPB demonstration. My press card’s chain was broken [so] I did not hang [my press card] around my neck, but put it inside my pocket. I have covered the police beat for five years. I guess they already know my face. They should know that I am a journalist. While I was taking photos, suddenly an intel [police intelligence officer] in plainclothes asked me who I was. Five other police officers in uniform surrounded me. That intel [grabbed me by] my neck, asking me what I was doing taking photos. But a [native] Papuan police officer shouted, “She’s a journalist! She’s a journalist!” The [intel] let me go but with some threatening words.[167]

Both Pogau and Wayar assert that their ethnic identity as native Papuans is the source of reflexive suspicion and aggression by non-Papuan security forces who seek to interfere with their reporting activities. Wayar noted that although she was familiar with the intelligence agent who attacked her, “he did not recognize my face. It made me realize that in these Indonesian intels’ eyes, all [native] Papuans look the same: dark skin, curly hair.” Pogau said that security forces routinely question whether native Papuan journalists are working as journalists or as pro-independence activists:

Every time a Papuan journalist is in trouble [with security forces], the reaction among Indonesian police or [non-Papuan] journalists is always to question [the journalist’s] capacity. Their viewpoint is more or less similar to that of the police officers who beat me. They were curious to see an ethnic Papuan taking photos of the protests. They beat me and asked questions later.[168]

Journalists who attempt to cover incidents at or near the massive Freeport mine complex in Timika have been subjected to violence by Freeport personnel while security forces allegedly stood aside. Duma Tato Sanda, the managing editor of the aforementioned Cahaya Papua daily newspaper in Manokwari, narrowly escaped serious injury when striking Freeport workers attacked him in Timika in October 2011. He told Human Rights Watch:

On October 10, 2011, I covered a protest of Freeport employees in Timika. I was riding my motorcycle. While entering a crowded street…a Freeport worker stopped a motorcyclist in front me. The worker asked for his ID but the motorcyclist couldn’t show one. [A group Freeport workers] hit him…. Then that [same] Freeport worker approached me and asked for my identity [card]. Five seconds later, he hit me. The other [Freeport workers] beat me, they kicked me. I immediately abandoned my motorcycle and my bag, running away to save my life. They chased me, throwing stones. A motorcycle taxi suddenly stopped and offered me a ride. He sped away with me. [The Freeport workers] threw stones. If I had not worn my helmet that day, I might be dead. I got bruises on my face, my shoulders, hands, and feet. I reported the attack to the Timika police, but no investigation was made against the attackers.[169]

Self-Censorship

The harassment, intimidation, and violence faced by journalists in Papua from multiple sources encourages a pernicious form of self-censorship, as reporters avoid coverage of topics, groups, and individuals that might elicit violent reprisals. Jo Kelwulun, chief editor of the Manokwari Express in Manokwari, describes self-censorship by journalists in Papua as an essential survival skill:

Journalists in Papua should self-censor themselves. I think all of them have to do that. It’s not only for their own financial needs, but also their own safety. Violence is rampant against journalists in Papua. I don’t know how many journalists have been beaten in my 15 years of reporting [in Papua]. It’s too many.[170]

Agusta Bunay, a Papua Barat TV presenter, said that self-censorship becomes reflexive among journalists, fearful of violent reprisals by “the Indonesian security establishment or rowdy elements of the Papuan [pro-independence] groups.”[171] The result of that censorship is a tendency among journalists in Papua to limit their reporting to one-dimensional official statements issued by government agencies and the security forces. “If you read all the news reports in all newspapers in Manokwari, you will see that their sources are almost all, almost 100 percent, government officials. Their sources are always government officials, police officers or military officers.”[172]

Ness Makuba, a journalist with state-owned Radio Republik Indonesia in Sorong, abandoned his investigation into the August 2014 killing of KNPB activist Martinus Yohame after Makuba’s first report on the death prompted an angry phone call from a Papua police spokesman.[173] Although Makumba had personally travelled with police officers and viewed Yohame’s body and noted what appeared to be fatal bullet wounds, the police spokesman demanded to know why Makuba had not sought further police confirmation of what happened. Makuba said due to the spokesman’s concern about his reporting, he “dared not continue” with any additional reporting into the killing.[174]

Irwanto Tenggowijaya, the owner of the Timika Express, a small pro-military newspaper in Timika closely associated with Timorese migrants, described how a recent story his paper ran on police corruption linked to a local illegal gambling den fueled a furious response from a senior local police official.[175] That response, which included a veiled threat of reprisal against Tenggowijaya’s business interests in Timika, prompted him to self-censor any follow-up reporting on the story. He said:

I went to see the [reporters] and told them to “tone down” their reporting. It was basically [an instruction] to quietly stop the publication [of stories related to police corruption]…Journalists usually do running news. “Toning down” means they should quietly stop the news [on a certain topic].[176]

Fake Journalists and Informants

I know many Indonesian journalists who worked as military and police informers in Jayapura and Manokwari. What these journalists-cum-informers have been doing is actually damaging trust in Papua. We live in fear. We live suspecting one another.

–Octavianus Pogau, Suara Papua chief editor in Jayapura, May 2015.[177]

The Indonesian government and security forces pay journalists in Papua to provide them with information and favorable media coverage. They further undermine media freedom in Papua by placing paid agents to work undercover as journalists for local media companies. Those agents act as informers within media companies and produce news that is slanted to fit the government narrative of the situation in Papua.