High school girls in Kabul, Afghanistan, line up to go home after classes in 2017.

© 2017 Paula Bronstein for Human Rights Watch

Girls sit for lessons on a stairwell inside a school building. Overcrowding—compounded by the demand for gender segregation—means that schools typically divide their days into two or three shifts, resulting in a school day too short to cover the full curriculum.

© 2017 Paula Bronstein for Human Rights Watch

Girls sit for lessons on a stairwell inside a school building. Overcrowding—compounded by the demand for gender segregation—means that schools typically divide their days into two or three shifts, resulting in a school day too short to cover the full curriculum.

© 2017 Paula Bronstein for Human Rights Watch

Girls cover their faces to protect themselves from the stench of a filthy and malfunctioning restroom in their school. at this school, girls have no toilets of their own and their only option is to use the ones on the far side of the buildings where the boys study. They do not have locking doors and are several minutes’ walk from a water point.

© 2017 Paula Bronstein for Human Rights Watch

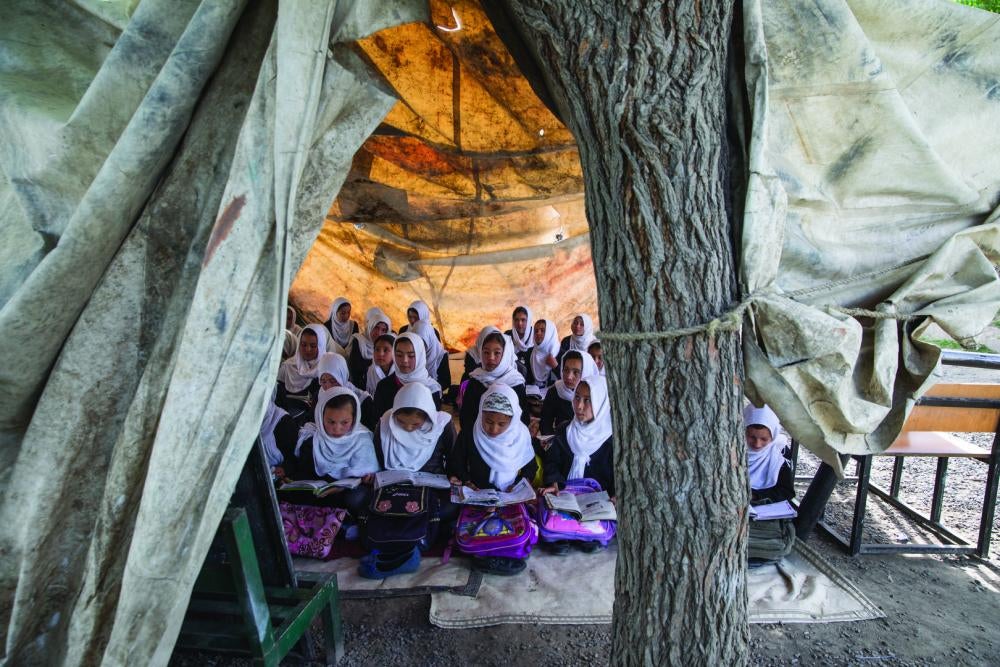

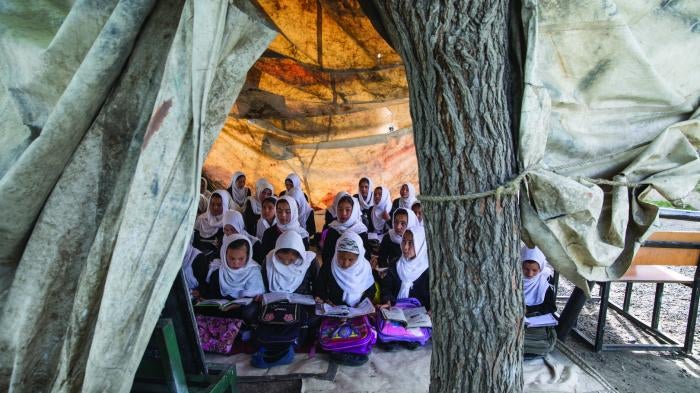

Girls study in a tent held up by a tree in a government school in Kabul, Afghanistan. Forty-one percent of all schools in Afghanistan do not have buildings and even when they do, they are often overcrowded, with some children forced to study outside.

© 2017 Paula Bronstein for Human Rights Watch

A member of Afghanistan’s security forces patrols on a hill overlooking Kabul. In recent years, security has steadily worsened across the country, including in the capital, which has repeatedly endured attacks targeting civilians. Many families struggling to educate their children face dangers such as gun battles, targeted attacks against girls' education, bombings, kidnapping, harassment, and common crime.

© 2017 Paula Bronstein for Human Rights Watch

Razor-wire surrounds a government school in Kabul, Afghanistan. Rising insecurity discourages families from letting their children leave home—and families are usually more reluctant to send girls to school in insecure conditions than boys.

© 2017 Paula Bronstein for Human Rights Watch

A 10-year-old girl sorts through rubbish to salvage plastic containers that she can sell. She leaves home at 6 a.m. and returns at 5 p.m. She does not go to school and works to help support her large family that includes nine brothers and four sisters. None of her siblings attend school.

© 2017 Paula Bronstein for Human Rights Watch

Two sisters, ages 9 and 5, work on the streets of Kabul selling chewing gum, earning about US$2 per day. At least a quarter of Afghan children between ages 5 and 14 work for a living or to help their families.

© 2017 Paula Bronstein for Human Rights Watch

A girl begs on the streets of Kabul, Afghanistan. Girls are most likely to work in carpet weaving or tailoring, but significant numbers also engage in street work, such as begging or selling items on the street.

© 2017 Paula Bronstein for Human Rights Watch

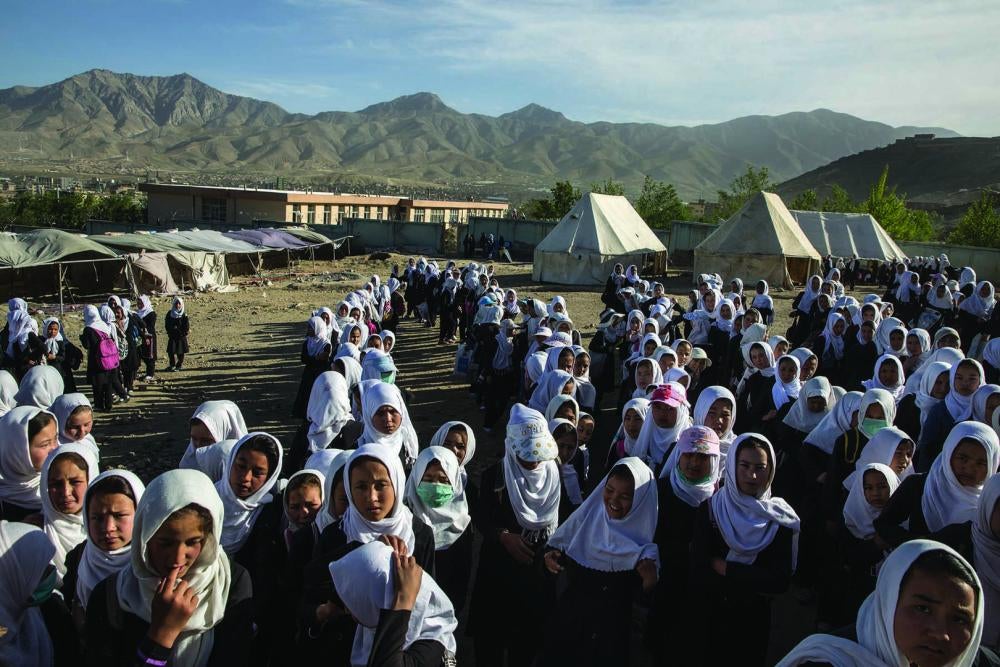

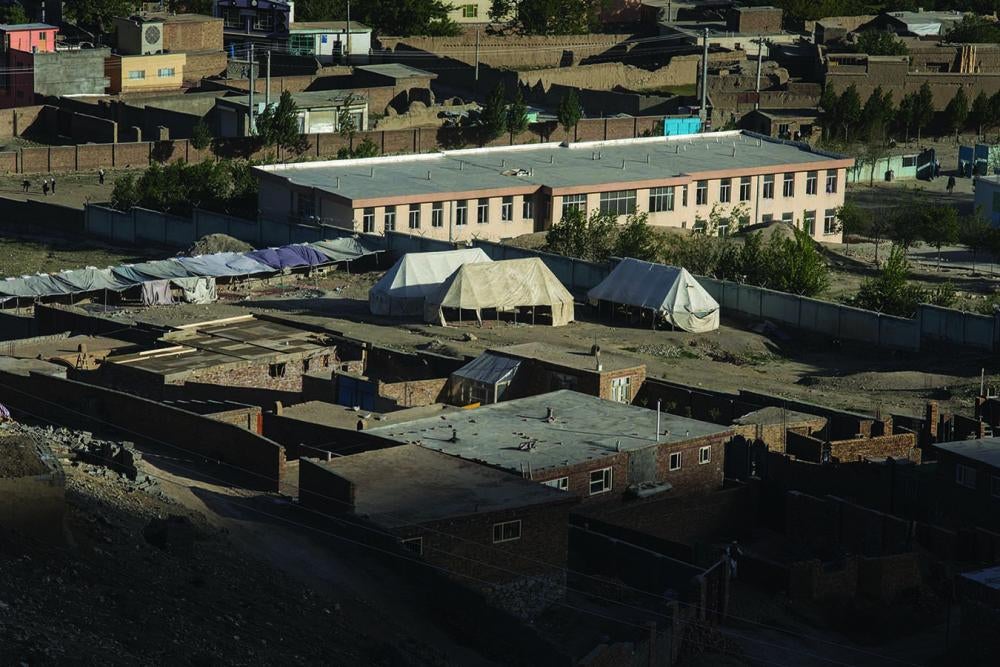

At this Kabul government school, the tents in the vacant lot are a girls' school where over 600 girls study. The buildings in the lot beyond the tents were paid for by international donors; they house a boys' school. Some girls are permitted to study in the buildings during the third shift of classes, after the boys have finished their studies for the day.

© 2017 Paula Bronstein for Human Rights Watch

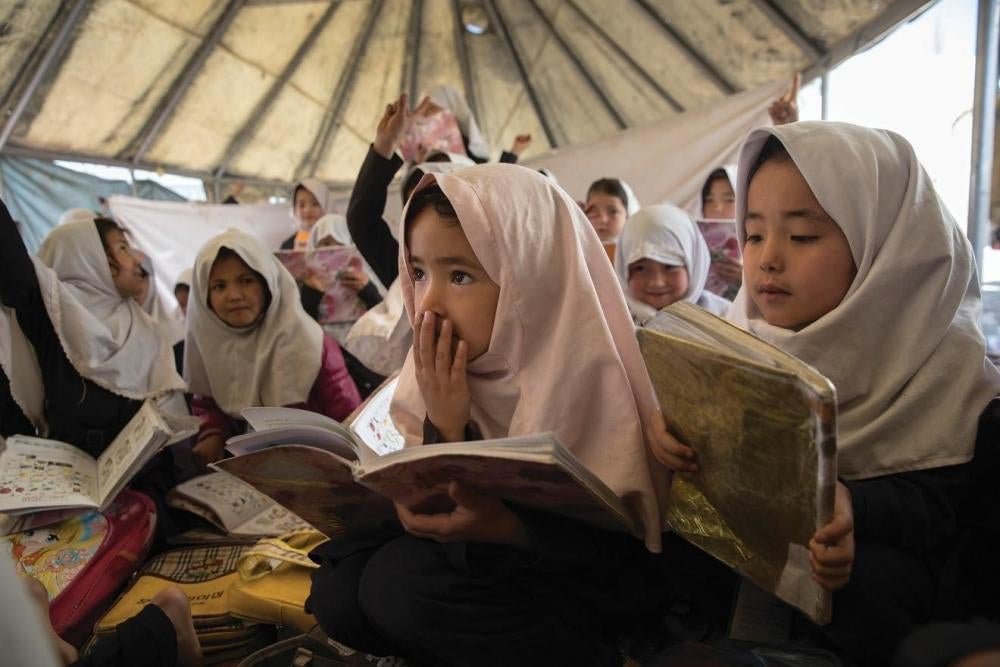

A class at a community-based education program in Kabul, Afghanistan. Community-based education programs are funded through and operated by nongovernmental organizations with the expectation that the government provides oversight. These programs—often referred to as “classes” rather than schools, as they are often based in homes—frequently consist of a single class of 25 or 30 students. They are designed to provide access to education in communities where there is no nearby school.

© 2017 Paula Bronstein for Human Rights Watch

Two classes take place back-to-back with only a cloth partition separating them. Even if girls can attend school, whether they stay often depends on the quality of the education.

© 2017 Paula Bronstein for Human Rights Watch

Boys study in the library of their government school in Kabul, Afghanistan. Girls are not allowed to use the boys' library at this school—instead they have a separate and much smaller library, with no table and chairs, few books, and it is not open for general study and reading but instead remains locked.

© 2017 Paula Bronstein for Human Rights Watch

Sixteen years after the US-led military intervention that ousted the Taliban government, an estimated two-thirds of Afghan girls do not go to school. And as security in the country has worsened, the progress that had been made toward the goal of getting all girls into school may be heading in reverse—a decline in girls’ education in Afghanistan.