Under Siege

Indiscriminate Bombing and Abuses in Sudan’s Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile States

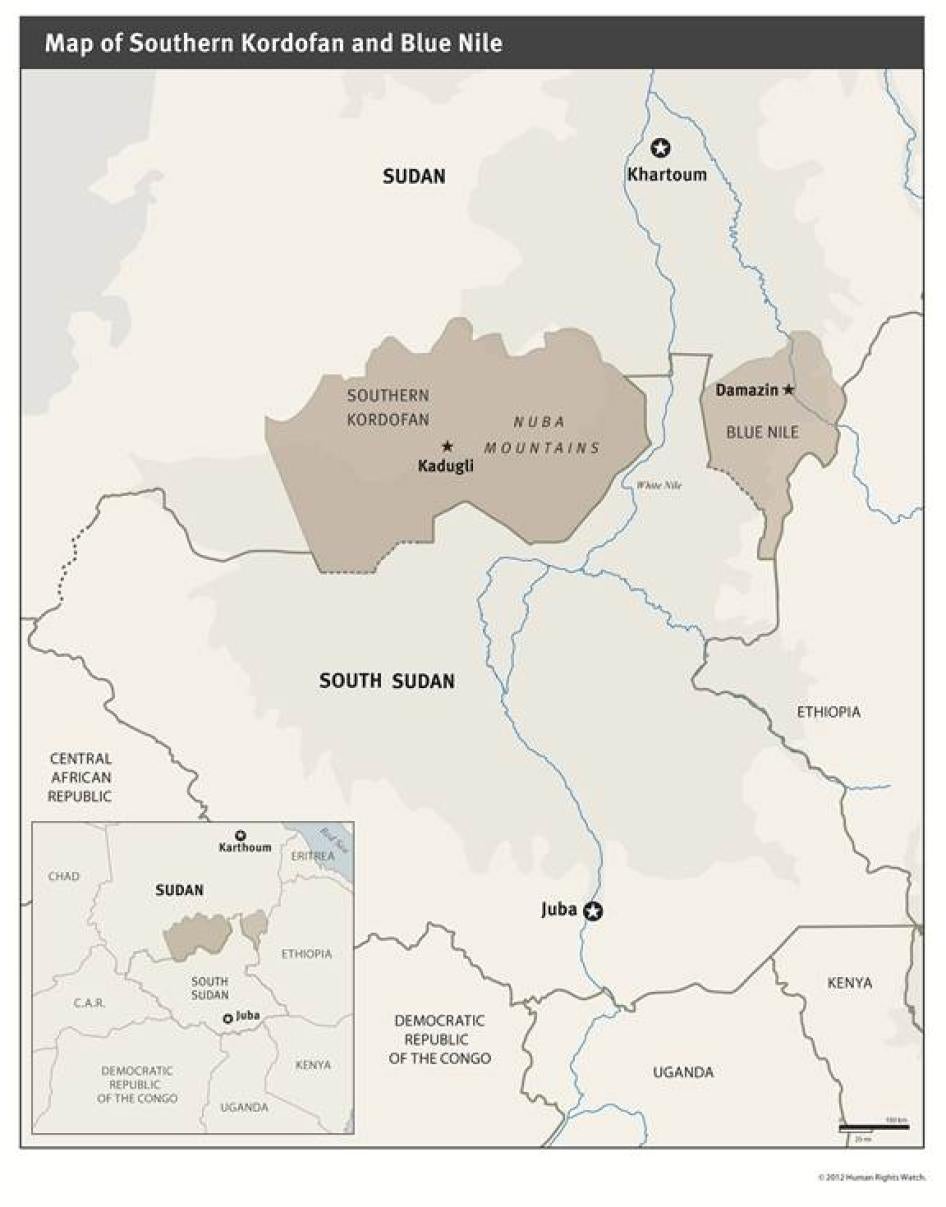

Map of Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile

Summary

On June 5, 2011, conflict broke out in Southern Kordofan state, Sudan, between Sudanese forces and the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA), the southern rebel movement whose forces were in Sudan under the terms of the 2005 peace agreement that ended the civil war. Tensions over security arrangements in the state and the narrow re-election victory of incumbent governor Ahmed Haroun, who is wanted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for serious crimes in Darfur, triggered the conflict. Fighting spread to neighboring Blue Nile state in September 2011. Days later, Sudan banned the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement - North (SPLM -North), the successor to SPLM after South Sudan’s independence in July 2011, and arrested scores of its members.

Since the conflict started, Sudanese forces have carried out indiscriminate aerial bombardment and shelling in populated areas, killing and injuring civilians and causing serious damage to civilian property including homes, schools, clinics, crops, and livestock. Government forces, including Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) and Popular Defense Forces (PDF), have also conducted ground attacks on villages during which they deliberately burned and looted civilian property, and arbitrarily detained people. Soldiers have also assaulted and raped women and girls.

The evidence documented suggests that the Sudanese government has adopted a strategy to treat all populations in rebel held areas as enemies and legitimate targets, without distinguishing between civilian and combatant. This apparent approach lies at the heart of the serious violations of international humanitarian law documented in this report. Human Rights Watch also received reports of abuses by SPLA-North forces, including indiscriminate shelling and unlawful detentions, but did not have access to the relevant areas or individuals to confirm reports.

This report is based on five separate fact-finding missions to Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile states in Sudan, and to Unity and Upper Nile states in South Sudan, in 2011 and 2012. Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 200 displaced people and refugees and staff from eight international and national organizations, and documented the human rights impact of the armed conflict on civilian populations, including Sudan’s indiscriminate bombing in populated areas and its refusal to allow critical humanitarian goods and services into Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile.

The researchers documented serious violations by Sudanese forces, including the deliberate killing of civilians, forced displacement, and destruction of civilian property as well as the arbitrary arrests, detention and in some cases presumed enforced disappearances of civilians. In one example, Issa Daffala Sobahi, a guard for a government official belonging to the SPLM, was arrested, beaten, shackled, called “kufar” [infidel] by Sudanese government forces and was detained in a facility inside a military compound with other civilians. He told Human Rights Watch: “They took people to the river and shot them. I myself was taken to the river with three others on the second day. They killed two of us.” He managed to escape from the prison compound.

An estimated 900,000 people have been displaced or severely affected by the conflict, and over 210,000 now live in refugee camps in South Sudan and Ethiopia. Large areas of land in Blue Nile state in particular, are now abandoned. Sudan’s abusive tactics, reminiscent of those used in Darfur and during the long civil war, including the de facto blockading of humanitarian assistance, have worsened already poor conditions.

The international response to this crisis has been muted, eclipsed largely by efforts to address deteriorating relations and resumption of conflict between Sudan and South Sudan in April 2012. The African Union (AU) and United Nations (UN) have repeatedly urged the parties to the conflicts in Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile to agree to modalities for aid delivery, which they finally did in August 2012. But because of delays caused by Sudan, the agreement has not been implemented. Hundreds of thousands of people continue to face deprivation, including serious hunger and poor health conditions.

The AU, UN, League of Arab States, and countries with interest and involvement in Sudan including China, the United States, Qatar, and European Union member states, should urgently address the deteriorating human rights situation by insisting Sudan end use of all tactics that violate the laws of war, and allow humanitarian aid groups to have unfettered access to all affected populations in line with international law.

These key international actors should firmly impose clear deadlines on the Sudanese government in particular to allow aid to civilian populations. They should also impose sanctions on those responsible for serious human rights and humanitarian law violations, and seek to establish a UN-mandated investigation into the allegations of serious violations of international law that have occurred since June 2011, with a view to holding those responsible for serious crimes accountable.

The lack of justice for serious crimes committed during the North-South conflict and Darfur also appears to have emboldened those engaged in the South Kordofan and Blue Nile conflicts. The key international actors should ask Sudan to cooperate with the ICC’s investigation into crimes in Darfur, including by ensuring that President Omar al-Bashir, Ahmed Haroun, and other suspects appear before the International Criminal Court to face charges of serious crimes committed in Darfur.

Recommendations

To the Government of Sudan

- Immediately stop indiscriminate attacks; parties to the conflict must at all times distinguish between civilians and combatants and between civilian objects and military objectives;

- Order an end to all attacks directed at civilians by government forces, including the Sudan Armed Forces and Popular Defense Forces, which violate the laws of war, and hold those responsible to account by effective investigations and prosecution;

- Immediately release all arbitrarily detained civilians, end ill-treatment and torture of all detainees, and ensure those detained on a lawful basis enjoy full due process rights; hold officers responsible for violations of the prohibition on arbitrary detention and ill-treatment of detainees to account by effective investigations and prosecution;

- In accordance with obligations under international law, urgently facilitate unimpeded access by humanitarian aid groups to deliver assistance to civilians in all parts of Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile;

- Permit safe passage for all civilians attempting to leave areas where there is active fighting and bombings;

- Allow access for international monitors, including human rights officers, to Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile states;

- Ratify the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court and ensure that Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir, Ahmed Haroun, and other suspects appear before the court to face charges on serious crimes committed in Darfur.

To the Sudan People’s Liberation Army-North

- Safeguard the neutrality and civilian nature of refugee camps and internally displaced persons (IDP) settlements by avoiding, to the extent feasible, locating forces in and near any refugee or IDP camps in Unity or Upper Nile states, South Sudan, or conducting military activity, including recruitment, in or near camps;

- Investigate and hold to account soldiers accused of crimes against civilians, including displaced persons and refugees, and including sexual violence against women and girls;

- Direct forces operating in Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile, to the extent feasible, not to locate themselves or military equipment in places populated by civilians;

- Permit safe passage of all civilians attempting to leave areas where there is active fighting and bombings.

To the United Nations Security Council

- Demand the immediate end to indiscriminate bombing and that all parties strictly adhere to the principle of distinction required by the laws of war;

- Demand the immediate end to all attacks on civilians by Sudanese government forces, including the Sudan Armed Forces and Popular Defense Forces, in violation of the laws of war, and make it clear that those responsible must be held to account;

- Urgently press both parties to facilitate unimpeded access by international humanitarian groups to civilians in need in Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile, pursuant to their legal obligations, and insist access be permitted within a specified time frame;

- Press both parties to permit access for international monitors to Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile states;

- Request the UN Secretary General to authorize an independent inquiry into, and publicly report on, serious breaches of the laws of war by all parties to the conflict in Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile since the conflict started. Where possible, the inquiry should seek to identify, those who, due to their individual or command responsibility for such violations, should be subjected to further criminal investigations and/or targeted sanctions;

- Impose targeted sanctions against Sudanese and SPLM -North or SPLA-North officials deemed to be responsible for serious crimes including the failure to end indiscriminate bombing and other human rights violations, and for blocking humanitarian access to Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile states in violation of international law;

- In view of the evidence of the commission of serious violations of international humanitarian law against civilians by the Sudanese armed forces, expand the existing arms embargo on Darfur to apply to the two states.

To the African Union and League of Arab States

- Demand the immediate end to indiscriminate bombing and that all parties strictly adhere to the principle of distinction required by the laws of war;

- Demand the immediate end to all attacks directed against civilians by Sudanese government forces, including the Sudan Armed Forces and Popular Defense Forces, in violation of the laws of war, and make it clear that those responsible must be held to account;

- Urgently press both parties to facilitate unimpeded access by international humanitarian groups to civilians in need in Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile, pursuant to their legal obligations, and insist access be permitted within a specified time frame;

- Press both parties to permit access for international monitors to Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile states;

- Request the UN Secretary General to authorize an independent inquiry, and publicly report on, alleged violations of international human rights and international humanitarian law in Sudan’s Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile states. Where possible, the inquiry should identify those who, due to their individual or command responsibility for such violations, should be subjected to further criminal investigations and/or targeted punitive sanctions.

To Key Nations involved in Sudan including the United States, China, Qatar, South Africa, European Union, and its Member States

- Demand the immediate end to indiscriminate bombing and that all parties strictly adhere to the principle of distinction required by the laws of war;

- Demand the immediate end to all attacks directed against civilians by Sudanese government forces, including the Sudan Armed Forces and Popular Defense Forces, in violation of the laws of war, and make it clear that those responsible must be held to account;

- Urgently press both parties to facilitate unimpeded access by international humanitarian groups to civilians in need in Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile, pursuant to their legal obligations, and insist access be permitted within a specified time frame;

- Press both parties to permit access for international monitors to Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile states;

- Support and actively work for the urgent establishment of an independent UN mandated inquiry to investigate and publicly report on alleged violations of international human rights and international humanitarian law in Sudan’s Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile states, and where possible identify individuals who, due to their individual or command responsibility for such violations, should be subjected to further criminal investigations and/or targeted punitive sanctions;

- Impose targeted sanctions against Sudanese and SPLM-North and SPLA-North officials deemed to be responsible for crimes, including the failure to end indiscriminate bombing and other human rights abuses, and for blocking humanitarian access to Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile states in violation of international law.

To UNHCR and Humanitarian Organizations Working in Refugee Camps in South Sudan’s Unity and Upper Nile States

- In Upper Nile State, increase the capacity of refugee registration teams, to ensure the timely registration of new arrivals and ensure they have full access to schools, clinics, shelter and food;

- Create activities for adolescents and young people, including secondary schooling or other structured activities to reduce the risk of adolescent recruitment;

- Develop initiatives, such as expanding pilot projects for fuel-efficient stoves, to reduce risk of sexual violence to women and girls when collecting firewood;

- Create opportunities for female-headed households, for income generating activities or other assistance so that widows and other vulnerable women are able to provide basic needs for their children.

Methodology

The report is based on five separate fact-finding missions to Sudan and South Sudan, each lasting about ten days, in August 2011, April 2012, and October 2012. Human Rights Watch visited villages and displaced communities in Sudan’s Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile states, and also refugee camps in Unity and Upper Nile states in South Sudan. Through interviews, site visits, and examination of physical evidence, Human Rights Watch documented various human rights violations committed during the armed conflict in both states, and assessed the impact of Sudan’s humanitarian blockade on the civilian population.

Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 120 refugees and displaced persons in Southern Kordofan, Sudan, and in Unity, South Sudan. Researchers also interviewed more than 75 refugees and displaced persons in Blue Nile, Sudan, and Upper Nile, South Sudan. Interviews were conducted mainly in Arabic, but also in local languages through local translators. They were conducted both privately and in groups, in towns, villages, remotes settlements in rural areas, and in refugee camps in South Sudan.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed representatives of UN agencies and international nongovernmental organizations and religious organizations, Sudanese civil society activists and human rights monitors, local community leaders, and officials from the rebel Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North and Sudan People’s Liberation Army-North. We informed all persons interviewed of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and the ways in which data would be collected and used. The names and other identifying information of some of our interlocutors have been withheld in order to protect their personal security.

While no officials from the Sudanese government were interviewed due to Human Rights Watch’s lack of access to government controlled areas, the report takes note of Sudan’s response to the August 30, 2011, joint press release by Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International on the situation in Southern Kordofan, in addition to the government’s extensive response, issued on August 16, 2011 by its mission to the United Nations office in Geneva, to the report of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, released in early August 2011.

I. Background

Just as South Sudan was set to become an independent nation in July 2011 under the terms of the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA),[1] tensions were rising in Sudan between the ruling National Congress Party (NCP) and remaining forces of the former southern rebel Sudan People’s Liberation Movement Army (SPLA) still present in Sudan, over political and security arrangements in Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile states.

Fighting broke out in Southern Korfodan on June 5, 2011, triggered in part by disputed state elections in which the incumbent candidate for governor, Ahmed Haroun, claimed a narrow victory. Haroun, like Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir, is subject to an arrest warrant by the ICC for crimes committed in Darfur. The fighting spread to Blue Nile on September 1, 2011.

President al-Bashir declared a state of emergency and dismissed Malik Agar, the SPLM governor of Blue Nile, replacing him with a military commander. In the following weeks, Sudanese authorities banned SPLM-North, seized their offices, arrested scores of party leaders and members across the country, and imposed new media restrictions and banned other parties for their alleged links to South Sudan.[2]

Both Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile states, bordering the now-independent South Sudan, have populations with longstanding ties to the former southern rebel SPLA during Sudan’s long civil war. In view of the political and ethnic diversity in the two states, the CPA provided they would have popular consultations whereby residents could evaluate the government arrangements in their state and make amendments to accommodate their needs, while remaining part of a federal Sudan.[3]

Instead, renewed conflict interrupted the consultations. In the 18 months prior to the publication of this report, Sudan was engaged in a conflict with SPLA-North forces in the two states, as well as fighting rebel groups in Darfur for the past nine years. Sudan’s tactics in Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile – like those used in Darfur and during the civil war in Southern Sudan -- include aerial bombing using cheap, unguided bombs, and ground attacks on communities presumed to support SPLA by virtue of living in rebel held areas or shared ethnic ties.

These tactics suggest a deliberate strategy of the Sudan government to treat all populations in rebel held areas as enemies and legitimate targets, without distinguishing between civilian and combatant. This goes to the heart of the serious violations of international humanitarian law documented in this report. Failing to distinguish between civilian and military is strictly prohibited by international humanitarian law. Also prohibited by international humanitarian law is treating a whole town, village, or other area as a single military target, when there are separate and distinct military objects along with a similar concentration of civilians or civilian objects.[4] Violations of these prohibitions may amount to war crimes.

The Sudan government has also deployed large numbers of Popular Defense Forces (PDF), auxiliary forces drawn from local communities, capitalizing on pre-existing local tensions to fight ground wars expediently.

Hundreds of thousands of people have fled their homes, lost their livelihoods, separated from family members and are living without sufficient food, water, shelter, or hygiene. Conflict is expected to intensify throughout the dry season which starts annually in October, and to result in more hunger, deprivation, and refugee flows into teeming refugee camps in South Sudan that already host more than 175,000 Sudanese.

II. Southern Kordofan

Southern Kordofan, Sudan’s only oil-producing state, lies north of the border with South Sudan. Fighting started on June 5, 2011, between SAF and SPLA forces stationed in Kadugli, the state capital, and Um Durein town, and quickly spread to other towns and villages where both forces were present under the terms of the CPA.

During the first days of fighting in Kadugli town, UN human rights observers documented serious human rights violations by government forces, including killings, arbitrary arrests, and widespread destruction and looting of civilian property. [5] Since the fighting started, Sudanese forces have pursued a campaign of indiscriminate bombing in populated areas in rebel-controlled territory. [6] Such attacks could amount to war crimes and crimes against humanity.

As of the beginning of December 2012, Sudanese government forces maintain control over Kadugli and other main towns and areas near Dilling, Talodi, Dellami, Rashad, Abbasiya, and Abu Jibeiha. The SPLA-North controls large areas of the countryside around Kadguli, particularly in El Buram, Um Durein, and Heiban localities, and mountainous areas northwest of Kadugli. In February 2012, SPLA-N forces overtook government positions on the road to South Sudan, thereby securing a route south to Yida refugee camp in South Sudan.

Indiscriminate Bombing and Shelling

In the 18 months between June 2011 and December 2012, Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) have carried out hundreds of bombings, shelling, and rocket attacks on civilian areas across the Nuba Mountains where the rebels have control. The strikes varied in frequency and intensity, from several times per month to several times per day. Sudanese monitors reported 106 bombs were dropped in the month of October 2012, and 125 in the first half of November alone. [7]

The bombings have killed, maimed, and injured civilians in their homes, while farming, fetching water, or attending village markets, and have destroyed homes, crops, livelihoods, clinics, and schools, and forced people to abandon their homes and livelihoods. The persistent bombing has terrorized the population; most families have dug foxholes near their homes or moved to sheltered areas, and even small children now refer to the “Antonovs,” the common name for the cargo planes used by Sudan to drop bombs.

Human Rights Watch investigated bombing incidents in four localities – Kadugli, Um Durein, Heiban and Dellami – through direct observation of the bombings and through witness interviews, examination of bomb fragments, craters and other physical evidence.[8] Typically the bombings used unguided munitions that are dropped from Antonov cargo planes or other aircrafts flying at high altitude. Such methods do not allow for accurate delivery. Use of weapons in a civilian area that cannot accurately be targeted at a military objective makes such strikes inherently indiscriminate, in violation of international humanitarian law.[9]

In addition to evidence that Sudan is bombing and shelling indiscriminately, Human Rights Watch found evidence that Sudan is also using cluster bombs despite emerging international prohibitions on the munitions.[10]

The vast majority of bomb victims that Human Rights Watch documented are civilians. Most of these are women, children, and the elderly. Of 122 treated for aerial bombardment wounds at a hospital near Kauda in the past 18 months, 110 were civilians according to medical staff who spoke to Human Rights Watch.

In all incidents investigated, witnesses and victims told Human Rights Watch that there were no military targets, such as a rebel presence, in the vicinity at the time of the bombings. While Human Rights Watch could not confirm the absence of SPLA combatants in the vicinity when the bombings took place, evidence gathered by Human Rights Watch about the incidents suggests that no effort was made to identify and avoid civilian objects, and that the weapons predominately used by Sudanese air forces cannot accurately be targeted in a manner that distinguishes between civilians and potential military targets.

In addition to strictly observing the principle of distinction (that is, parties to the conflict must at all times distinguish between civilians and combatants and between civilian objects and military objectives)[11] parties have an obligation to take constant care to spare the civilian population, civilians, and civilian objects. In this regard SPLA-North fighters should not operate or initiate attacks from residential areas and to the extent feasible should avoid operating in populated civilian areas where their presence is likely to have a harmful impact on civilians.[12]

Examples of civilian victims wounded by use of indiscriminate bombing include Huwaida Hassan, mother of seven, who was seriously injured by a bombing on the Heiban market around mid-day on October 2. The bomb fragments sliced into her belly. Two elderly women and a teenage girl were among the others injured. Fadila Tia Kofi, a woman in her 70s, was injured by bomb fragments at around 11 a.m. on September 11, 2012, while working at her garden near her home in Lima village, western Kadugli locality. “I heard the sound of a plane and I fell to the ground. A big piece of metal cut my toes,” she told Human Rights Watch at her home in October 2012. “I don’t know why the bombs come. I work, I farm. Now I crawl.” All the toes of her right foot were amputated and she can no longer walk. [13]

In March 2012, a bomb fell near 16-year-old Daniel Omar, while he was grazing cattle. Fragments immediately severed one arm and injured the other so badly that it was later amputated. “I still have pain in the wounds,” he told Human Rights Watch from a hospital bed in Southern Kordofan in late April 2012.

Five members of a single family – including three teenaged sisters -- died when shells hit and set ablaze their home outside of Um Sirdiba in Um Durein locality, on the night of February 17, 2012. Four sisters sleeping in one room burned to death. Their father, Samuel Dellami, died soon afterward. His brother told Human Rights Watch in April, 2012: “Before he died, he said ‘where are my daughters?’ No one answered because we were all confused. This is the only thing he said. People cried and after that, we picked the dead bodies and buried them.”

On February 18, 2012, bombs were dropped on Angolo, in El Buram locality, injuring Halima Tiya Turkan, age 35, while she and her daughter were hiding in a cave to escape an approaching airplane. “My brother was hit by an Antonov on Friday and on Saturday we were going to his funeral. We saw an Antonov and ran into the caves. A bomb dropped near the opening of the cave where I was with my daughter and shrapnel entered inside,” she told Human Rights Watch. “The shrapnel hit me on the side, until my intestines came out.” [14]

In one of the most lethal strikes, 13 civilians were killed while fetching water and shopping at the market at Kurchi, in Um Durein locality on June 26, 2011. Explosions from several bombs killed five children and three women. Bomb fragments maimed and injured more than 20 others, paralyzing an eight-year old girl from the waist down.[15]

Bombs have also damaged or destroyed civilian property including clinics, schools, market stalls and other structures. On January 13, 2012, a bombing in Al Ganaya, in El Buram, destroyed a church and home. Human Rights Watch observed unexploded missiles, reportedly fired in November 2011, lodged beneath and near a secondary school in Korungu, Kadugli locality, rendering the school unusable and the area dangerous. Sudanese monitors also reported that bombing damaged a church in Darea, Dalami locality, on December 31, 2011; a bible school in Heiban on February 1, 2012; a clinic in Kurchi, Um Durein locality, on February 6, 2012; a primary school in Um Sirdiba on February 17, 2012; and a clinic at Kolulu on October 24, 2012, in an incident that also killed one civilian and injured two others.

Attacks and Abuses by Government Forces

At the start of the conflict in June 2011, government forces, including the paramilitary Popular Defense Forces (PDF) and the Central Reserve Police, an auxiliary force, in Kadugli, shelled and bombed residential neighborhoods, looted and burned down homes and churches, shot at civilians, killed civilians including UN staff, and arrested scores of people suspected of links to the SPLM. The UN’s Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) documented these patterns of abuse, which Human Rights Watch and others warned could amount to crimes against humanity, and recommended an independent and comprehensive human rights investigation.[16] Sudan has vigorously refuted the UN’s findings.[17]

In the 18 months that followed, Sudanese ground forces carried out numerous other attacks on villages, killing civilians, destroying property, and arbitrarily arresting and detaining large numbers of people in violation of applicable international law.

Attacks on Villages

Human Rights Watch received reports of numerous cases in which Sudanese government or allied forces deliberately killed civilians, detained and placed hundreds at risk of enforced disappearance, and destroyed and looted civilian property. These actions constitute serious violations of customary international law prohibitions regarding the protection of civilians and civilian property, and may constitute war crimes in non-international armed conflicts.[18]

In El Taice, a town in El Buram locality that changed hands several times in 2011, witnesses told Human Rights Watch that SAF soldiers occupying the village at different times shot and killed civilians, destroyed homes and forcibly apprehended and took away hundreds of people. Hanan Kafi Raha, a 19-year-old mother of two who witnessed an attack in early 2012, told Human Rights Watch in April: “I saw the SAF pushing people out of the caves down to the vehicles parked near the foothills. There were maybe 15 vehicles. They were crowding people into the trucks.” Witnesses did not know the fate of most of those civilians detained in El Taice in early 2012. Most of them are presumed to be in government custody or living in government areas, but government restrictions have prevented families from getting information about their fates or re-uniting with them.

Civilians from Troji, another village in El Buram locality, described a similar pattern of detentions and subsequent disappearances when government forces captured the town in December 2011. Scores of people were detained while trying to gather remnants of the destroyed harvest from their fields or while going to fetch water, or were forcibly removed from places they had taken refuge in the mountains. Their whereabouts are still unknown, and as the Sudanese government has not provided any apparent information on their fate, they are presumed victims of enforced disappearances.[19]

Human Rights Watch has received information about other attacks on villages, but could not access the attack sites. A Sudanese citizen journalist group, Nuba Reports, documented compelling evidence of a May 18, 2012 ground attack on Gardud El Badry, a village near Al Abassiya, by SAF, PDF, and the Central Reserve Police, known as “Abu Tira.” A cell phone video clip, corroborated by witness interviews, shows a group of the attackers tying up a Nuba youth and thuggishly insulting him and demanding to know where the cows are, presumably for looting. The boy, an 18-year- old student, was detained for 10 days and recounted how he was beaten with whips.[20]

The group also obtained a similar cell phone video clip of an earlier attack on Um Bartumbu village, south of Al Abassiya, in November 2011, in which PDF forces are seen torching the village. The damage shown in the video clip was reportedly confirmed by the Satellite Sentinel Project’s imagery.[21]

Displaced civilians in Sabat, in Habila locality, northeast of Kadugli, told Human Rights Watch in August 2011 how a large group of government soldiers and militia from Burumbeta and Khor el Dileib villages burned the houses of civilians who were presumed to be SPLA supporters in Khor el Dileib, then attacked Sarafaya village, which had been intermittently under SPLA control, in July 2011, without attempting to distinguish civilians from possible rebel soldiers. Ismail Naway, a farmer who fled the town with his wife and eight children, recalled: “They came in pick-ups and by foot and had kalash, jeem [types of automatic weapon], and rockets. They were attacking the whole village. They wanted to kill people and take animals. I saw them kill one person before we left.”

Civilians displaced from Harazaya, a village near Kadugli town, told Human Rights Watch how 50 families fled the village upon receiving a warning that government forces from the neighboring village Harazaya Zuruq were preparing to attack on January 3, 2012. Witnesses saw the soldiers drive six vehicles to a position nearby, fire shells at the village, then torch houses and loot animals and other property.[22]

Arbitrary Arrest and Detention

At the outbreak of conflict in June 2011 in Kadugli, government forces arrested and detained scores of people suspected of supporting SPLM or SPLA during house-to-house searches and at checkpoints. Witnesses from Kadugli told Human Rights Watch and UN human rights monitors that government forces had lists of names of Nuba people wanted for their real or perceived links to the SPLM, and were arrested on this basis.

In one example, Mohammed M., a 33-year- old former accountant in the Southern Kordofan Ministry of Health and SPLM member, told Human Rights Watch that in July 2011 national security officials arrested him in El Obeid town (North Kordofan), where he had fled after conflict erupted. He was detained by military intelligence forces in El Obeid then transferred to Kadugli, where he stayed for nearly a year in military detention before he managed to escape. Mohammed said he was forced to confess to being a SPLA soldier under pressure, after he was badly beaten. “Soldiers tied my hands and legs and whipped my back until it was bleeding. They ordered me to ‘talk’ but I did not know about what. Then I was tortured whenever SPLA won a military victory.”[23]

Civilians with real or perceived links to the SPLM-North continue to face threat of arrest inside government areas, according to people Human Rights Watch interviewed. In one example, Sudanese security officials in Kadugli arrested Sara L., a 22-year-old mother of two, at her home on October 24, 2012, and detained her for three days because of her suspected links to the SPLM-North. Security officials had previously detained her father for 14 days in September because of his work with a Nuba cultural organization. Sara L. was shackled, beaten and detained with 35 other women in a national security detention facility inside Kadugli town. Upon her release, she fled to a rebel-controlled village outside Kadugli, traveling on her own at night.

On August 22, 2012, national security officials arrested Omaia Abdelatif Hassan Omaia, an employee with the Ministry of Finance and a member of SPLM-North, near Abu Jubeiha, in eastern Southern Kordofan state. At this writing he is understood to remain in detention at a government’s official’s house in Rashad and is at risk of torture.[24]

In early November dozens of people were arrested in Kadugli following the rebel group’s shelling of the town, and accused of collaborating with rebels; more than 30 women remain in detention without charge and have reportedly been denied access to lawyers or family. [25] In Dilling, north of Kadugli, dozens of civilians, including an elderly man with chronic health problems, were reported detained by national security and military intelligence officials following weeks of skirmishes between government and rebel forces in the area. [26] Human Rights Watch was not able to confirm the circumstances of these detentions, but understands they have not been charged or moved into a civilian detention facility.

In situations of internal armed conflicts, the deprivation of liberty is governed by both international humanitarian law and by human rights law. These laws prohibit arbitrary detention, ill-treatment of detainees and provide for due process protections for detainees. Under certain circumstances, individuals may be detained on security grounds without being charged with an offense, but in such exceptional cases, detention must be absolutely necessary, temporary and reviewed periodically to determine if there is a legal basis for continued detention.[27]

Sudan should make known the names of all those in detention, their whereabouts, release those arbitrarily detained and ensure the full application of procedural safeguards and due process rights to those detained on lawful grounds.

Sexual Violence

Government forces have also subjected women and girls to sexual violence. Its prevalence is difficult to determine, and commonly in situations of armed conflict sexual and gender based violence is underreported, but focus groups of refugee women in Yida identified sexual violence as a pressing concern while fleeing their homes in Nuba Mountains, as well as an ongoing concern in the camp.[28]

In one horrific incident in November 2011, PDF soldiers stationed at Jau, a military base near the South Sudan border, assaulted and raped two Nuba girls, ages 14 and 16, who were traveling from Angolo, in El Buram locality, to the Yida refugee camp in South Sudan.[29] In El Taice, Human Rights Watch interviewed victims and witnesses of sexual violence by government soldiers at different times in November 2011 and early 2012. Halima T., a young woman in her twenties, told Human Rights Watch that her aunt was raped by government soldiers. “I saw my aunt being raped. We were in the mountain together, and they came and took her. She was raped near the mountain… afterward they took her to Kadugli.”

Human Rights Watch previously documented reports of rape in Kadugli and Heiban in 2011 shortly after conflict broke out. Several people also told researchers that they heard of rape incidents involving government soldiers or allied militia in late 2011 and early 2012 in Dalami, Troji, and Dammam, but researchers could not confirm specific incidents.[30]

Sudan has an obligation to protect women and girls from all acts of sexual violence and to hold perpetrators accountable. If committed during armed conflict, sexual violence could amount to a war crime, which Sudan has a duty to investigate and prosecute. Non-state armed groups also have an obligation to prevent sexual violence and should investigate and appropriately punish perpetrators.[31]

Ongoing Displacement

Since the war began, hundreds of thousands of people have fled their homes in both government and rebel-held areas to escape bombing and ground attacks or arrest. The UN estimates more than half a million people have been displaced or “severely affected” in Southern Kordofan state, and of these, there are 350,000 in rebel-held areas, 207,000 in government-held areas, and 65,000 have gone to Yida refugee camp in South Sudan.[32]

Ongoing conflict is forcing people to flee locations all over the Nuba Mountains. In July and August 2012, for example, fighting in northeastern localities of Rashad and Abbasiya forced thousands to flee. People have also fled fighting near government-controlled Talodi town on numerous occasions since the outbreak of conflict, particularly in March and April 2012, when SPLA-North attempted to take control of the town. In Kadugli, many people fled after rebel forces shelled government positions in the town in October and November. 18 civilians reportedly died in the shelling.[33]

In addition, Sudan’s indiscriminate bombing in civilian areas keeps many from returning home, even if their homes are in rebel-held areas. Amna Kuku Tia, age 70, from Lofo village, told Human Rights Watch in October 2012 that she is afraid to leave the hills of Korungu where she settled at the outbreak of war to return to Lofo because she anticipates more shelling and bombing there. “I don’t have the legs to run anymore so I am better here in the rocks.”

One of the most difficult consequences is separation of family members. Nearly everyone in rebel-held areas said they had family members in government-held areas they could not join because of the government’s movement restrictions. “We all have family we cannot see,” Sumaya, a 37-year-old mother of four children living in Khartoum, told Human Rights Watch. Sadiq al-Nur, a 58-year-old lab technician from Khartoum was trapped with his daughter while visiting his second wife and their three children before the conflict started, and is afraid to return home to his other family members. “I am stuck. This door is closed.”

Denial of Access to Food, Water, Health, Education

Sudan’s abusive tactics have caused a large-scale humanitarian crisis. Hundreds of thousands of civilians, many of them forcibly displaced, urgently need shelter, food, access to potable water, healthcare, and education for their children. Yet the Sudanese government has blocked access to all goods and services from outside rebel-held areas, including desperately needed humanitarian aid.

Since the beginning of the conflict, the government has restricted freedom of movement of civilians into and from rebel-held areas by closing roads and denying travel permission, and has repeatedly denied access to those areas by UN and international aid groups requesting permission to assess needs and provide aid. These restrictions have created a de facto blockade of humanitarian aid to rebel-held areas of both Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile.

Nuba communities rely on their own agricultural production for food, but were largely unable to cultivate in 2011 due to insecurity and indiscriminate bombing. In some places, witnesses told Human Rights Watch researchers they saw Sudanese forces destroy food and water supplies, wiping out food stocks in those areas. In Troji, for example, SAF soldiers set fire to stores of grain and to fields, destroyed grinding mills, looted cattle, and destroyed boreholes during fighting in December 2011.

Staple foods like sorghum are either unavailable at markets or simply too expensive for most of the local population. Many people survived on leaves, nuts, wild fruits, and hunting, preferring to stay in Nuba eking out enough to survive than attempt the long journey to Yida refugee camp in South Sudan.

The Korongu mek [traditional leader] told Human Rights Watch in October 2012 that 18 people in his area had died of hunger since July, while in April the deputy commissioner of Um Sirdiba reported 14 had died in Abu Hashim village. Conditions were especially difficult from June to August, when people sought food at local clinics and hospitals, and several hundred arrived every day at the Yida refugee camp.[34] A household survey conducted in rebel-held parts of Southern Kordofan in August found that the food situation had further deteriorated with 81.5% of families living on one meal per day and serious malnutrition among children.[35]

Local officials and aid workers expect increased fighting will drive tens of thousands more to Yida camp, and cause more acute hunger for those who remain in the rebel-held areas. The current harvest, which is providing some food, is not expected to last beyond December.

Sudan’s de facto blockade not only deprives people of food in the markets, it also deprives civilians of medicine and supplies, including vaccines against smallpox and preventable disease. Human Rights Watch observed a farmer and a trader, both badly wounded by an October 24, 2012 market bombing at Kursi village in Korungu locality, with serious wounds from metal fragments which an attendant said were still lodged inside their bodies. The men were in excruciating pain, lying on rope beds in a mud-hut clinic that had no doctors, painkillers or medical supplies.

Many teachers, like doctors and other civil servants, are not able to leave Kadugli or other government towns to report for work in rebel-controlled areas. Their absence is a pressing concern for many parents who see little choice but to send children walking, sometimes for days, to Yida camp for rudimentary schooling.

Sudan’s de facto blockade of humanitarian assistance violates international humanitarian law, which provides that where a warring party cannot provide assistance, it should permit impartial humanitarian organizations to access civilians and assist them and that humanitarian personnel should enjoy the freedom of movement essential to the exercise of their functions. Only in case of imperative military necessity may their movements be temporarily restricted.[36] International humanitarian law also strictly prohibits parties to an armed conflict from destroying objects indispensable to the survival of civilian populations and deliberately causing a population to suffer from hunger.[37]

Yida Refugee Camp Concerns

An estimated 65,000 refugees have moved to the Yida refugee camp in South Sudan since June 2011. While the rate of arrival declined from several hundred per day to 177 per week in late October 2012, the rate of new arrivals again increased in November, with 2,100 arriving in a week, the majority women and children, primarily because of insecurity and lack of food.[38] Camp administrators expect tens of thousands more will arrive by year’s end, due to fighting and food shortages.

The overriding protection concern in Yida is its proximity to the border -- at 11 km from the border, it is 39 km shy of the 50 km international standard [39] --and the presence of military personnel. The SPLA, SPLA-North, and Darfur rebels have all visited the teeming camp, compromising the civilian character of the camp and posing a security threat to refugees. The presence of any soldiers also poses a special threat to women and girls, who identified rape and sexual violence as an ongoing concern in Yida, particularly while collecting firewood. [40]

In September and October 2012, SPLA-North soldiers reportedly entered the camp and rounded up large numbers of men and boys including students and staff of NGOs, detaining many for days. The episode, which SPLA-North commanders justified as an effort to disarm the camp, underscored the vulnerability of unaccompanied minors. SPLA-North, in particular, should ensure such violations do not recur and that the civilian character of the camp is preserved.

III. Blue Nile

In September 2011, the conflict spread from Southern Kordofan to neighboring Blue Nile state when fighting erupted in Damazin, the state capital, between government forces and SPLA-North. Witnesses from Damazin told Human Rights Watch that during the clashes government soldiers used tanks and heavy weapons to target civilian property, including residential homes and the Malik Agar cultural center. Soldiers and national security forces then rounded up suspected members of the SPLM-North, many of whom are still presumed detained, and looted civilian property extensively.[41]

In the months that followed, Sudanese forces, in an attempt to rout out rebel forces, attacked villages in Roseris, Geissan, Kormuk, and Bau localities and bombed indiscriminately across the state, forcing the civilian population to seek shelter in the bush and hills where they lacked food, shelter, access to clean water and sanitation, and health care.

In addition to indiscriminate aerial bombings, government forces have shelled populated areas, and, along with allied militias, burned and looted homes and other civilian property. The government-led attacks have killed and injured scores of civilians, destroyed property, and displaced tens of thousands of civilians largely from ethnic groups with perceived links to rebel groups.

Since September 2012, Sudanese government forces have intensified attacks with increased strikes on populated areas in Bau and Kormuk localities, perhaps to forcibly displace the civilian population away from rebel-controlled areas. Evidence obtained by Human Rights Watch from displaced civilians from Blue Nile point to repeated indiscriminate attacks that have harmed civilians and damaged their properties that could amount to war crimes.

The bombing, shelling and attacks have continued to displace civilians in Blue Nile. More than 140,000 refugees have fled Blue Nile and crossed the border into South Sudan and Ethiopia, but tens of thousands remain displaced inside the state. The situation appears increasingly dire. Some displaced families reported they had to reduce their food intake in October and November to one meal every five days.[42]

As in Southern Kordofan, the government has largely shut off Blue Nile from the outside world by restricting movement into rebel-held areas and refusing to allow aid groups to those areas, effectively blockading the region.

Indiscriminate Bombing and Shelling of Civilian Areas

Sudan’s indiscriminate bombing and shelling has killed, maimed, and injured scores of civilians since September 2011 and destroyed civilian property including markets, homes, schools, farms, and the offices of an aid group.

Human Rights Watch visited more than a dozen bomb sites in Blue Nile state during two visits in April and October 2012, and interviewed dozens of victims of the bombardments and attacks, including refugees in South Sudan as well as internally displaced civilians inside Blue Nile who abandoned their villages and farms, mainly because of the consistent bombardments. On both visits, researchers visited bomb sites and examined evidence.

Researchers also examined the remnants of barrel bombings at bomb sites near Yabus in late October 2012. Barrel bombs are improvised crude devices filled with nails and other jagged pieces of metal that become deadly projectiles upon impact.

These and other unguided munitions are often dropped from Antonov cargo planes or other aircrafts flying at high altitude. Such methods do not allow for accurate delivery. Use of weapons including bombs and shells in a civilian area that cannot accurately be targeted at a military objective makes such strikes inherently indiscriminate, in violation of international humanitarian law.[43]

Witnesses in Blue Nile described several recent indiscriminate bomb attacks on, and shelling of, towns and villages in Kormuk and Bau localities in which civilians were killed. In one example during an August 2012 attack on Wadega village, west of Kormuk, Jubara Salim saw a shell kill his neighbor, whom he knew as Ahmed, while he was working in the field. He had not seen any rebel forces in the vicinity either before or during the shelling that killed Ahmed. He said the shelling takes place every two or three days in Wadega.[44]

When the shell hit, it cut Ahmed’s body into pieces. It was difficult to even identify him. We all ran away when the shelling started. And when we came back we just found pieces of him. When there is shelling, you don’t hear any noises before… It’s not like the Antonov bombings where you can hear the planes coming and can look up and see them and have time to run.

He was the fourth civilian Salim had seen killed since the conflict began in September 2011; the other three were killed during aerial bombardments. The indiscriminate bombing and shelling has spread palpable fear among the civilian population in Blue Nile. In all areas Human Rights Watch visited in Sudan including IDP camps, residents had dug foxholes for shelter in the event of a bomb attack.

Tahani Nurin, a mother of seven, fled from Surkum in late 2011 to escape the bombardments which hit the area around her home as many as three times a day. As a consequence of the relentless attacks, she and a group of 25 civilians started to walk in the direction of South Sudan when what she described as a barrel bomb hit them along the way as they rested and prepared food. The bomb killed her 17-year-old daughter Fatallah and two others, including a 12-year-old child.[45]

When [the bomb] hit, there was just smoke and dust and I couldn’t see anything. Moments later I saw my daughter and I called to her to see if she was injured. And then I saw the blood of my daughter. Within minutes the Antonov dropped a second bomb.

Refugees in South Sudan who arrived from villages around Tamphuna and the Ingessana Mountains told Human Rights Watch that since September 2012 they had noticed more frequent use of planes flying at high altitude and dropping bombs in rapid and multiple succession.[46] As a result of the more intense bombardments, victims and witnesses reported an increase in the number of deaths.

In late October 2012, Al-Tahir Jubatala said he fled to the refugee camp from his village in the Tamphuna area, near Kormuk, because of the intensification of bombardments and shelling.[47] A bomb landed on his house around July, killing all his livestock and destroying his house, and killed a neighbor from the village. He told Human Rights Watch that he endured months of bombardments so that he could harvest his crops to feed his family, but after the destruction of his home he was forced to leave his harvest behind, hoping it would feed the community’s elderly and frail who left to take shelter in the surrounding bush, unable to make the arduous journey to South Sudan during the rainy season.

Another villager from Tamphuna, Osman Mahmoud Mohamed, said that since September 2012, the army’s tactics have expanded from dropping crude bombs to more conventional weaponry, including rockets. “If you go to Tamphuna now, you find every house has a hole in it. The army is constantly hitting us,” he said.

One morning [in October 2012], I came back from looking for food and saw an explosion kill Ibrahim Gumus. He was 300 meters away. First I saw lots of dust and then I ran toward him. He was in one of the last houses in the village. Ibrahim had injuries to the head and he died after two hours. There was dark blood coming out of his mouth. No one else died that day. He was a 35-year-old butcher, with one wife and five children.[48]

Refugees in South Sudan as well as internally displaced civilians inside Sudan told Human Rights Watch that they often fled their homes because of the increased intensity and frequency of the bombardments, bringing only what they could carry. They abandoned their crops and farmlands which were often their only source of income and food. Many spent several months on the move with limited access to food and health care. When food ran out, they boiled bitter and sometimes poisonous roots that needed to be boiled for hours before becoming edible.

One group of five farmers from Gordala village near Wadega who arrived in the Doro refugee camp in late October 2012 with their families, had fled because of the intensification of the bombardments, forced to leave behind their food stocks from the recent harvest and family members who were too old and frail to make the journey:

We have farms and we didn’t want to leave because we were waiting for the harvest. But we were scared because the shelling became very intense and we were afraid that maybe the government would block the road to Doro so we left everything on the farms and came… Only the elderly are there. They can’t cross at this time. The mud, rain, and distance… is too difficult for them. They have our harvest to survive on, that’s all they have.[49]

Those who continue to be displaced in Blue Nile told Human Rights Watch they had limited access to food, water, and medicine and were surviving on wild fruits and plants. Human Rights Watch also saw recent photos of families in Chali district, preparing grubs and other insects to sustain themselves.[50] The displaced have no access to hospitals and their children have no access to school.

Zainab Ali, a 37-year-old woman from a village near Yabus, told Human Rights Watch that when Antonovs bombed close to her village in November 2011, she was pregnant and fell hard on the ground, causing her sustained pain.[51] When she and her family hid in the bush, they did not use any mosquito nets for fear that the Sudanese air force would spot the white fabric from the air. She said that living in the bush had increased the family’s health problems including greater susceptibility to malaria. Her cousin’s 10-year-old daughter died in the bush because there was no hospital to treat her after she fell ill with stomach pains and bloody diarrhea.[52] The family continues to live in Blue Nile.

Kareema Nasr, age 35, another internally displaced woman from Yabus, said the main problem for displaced peoples is hunger and health care, since they can no longer access their farms and the hospitals have closed.[53] One of Nasr’s daughters died shortly after her birth in the bush. Nasr believes the death was related to her malnourishment, her illness during the pregnancy, and to the fact that she did not have a midwife to assist her because she was hiding. In order to earn an income, she now pans for gold fragments, which can be sold in Ethiopia to buy basic food stuffs to sustain the family.

Attacks on Civilians

In areas near the frontline of the Blue Nile conflict between government forces and the SPLA-N, Sudanese ground forces have attacked villages from the ground and killed civilians even in areas that Human Rights Watch could find no evidence that there had been a rebel presence or threat or other legitimate military targets. In one incident shortly after outbreak of fighting, on September 3, soldiers at a checkpoint between Damazin and the neighboring town of Roseris shot dead two family members and the driver of Shukri Ahmed Ali, the local administrator of Roseris and SPLM member, apparently believing the he was in the car.[54]

After fighting broke out in Damazin, Sudan’s forces moved south, advancing on Kormuk, a rebel stronghold they captured in November 2011. Community leaders who fled to South Sudan told Human Rights Watch that Sudan government forces clashed with SPLA-North forces and conducted military operations in dozens of villages along the main road to Kormuk, and in villages in and around the Ingessana mountains.

Clashes have continued in that area and in the past three months there has been a reported intensification of aerial attacks, particularly near the village of Gebanit in Bau locality. According to one local Ingessana leader, he had recorded at least 29 civilian fatalities, including nine women and nine children, as a result of aerial bombardments and ground attacks in the area between May and July 2012.[55] He and other community members told Human Rights Watch that no rebels lived or operated near the villages.

One of the villagers, a 98-year-old man, was killed in in May 2012, when security forces launched an assault against another village near Gebanit called Gaman al-Tom. According to a witness, camouflaged trucks and land cruisers mounted with heavy weapons arrived at the village at 6 a.m. and started shooting. He said the shooting was not directed at any military target or at the rebels, since none lived in or operated out of the village. “When the shooting started, the rest of the village climbed up the mountains but the old man could not climb. After a few hours the military entered the village and burned everything. We ran down after they left and found the old man inside his house. He was totally burnt.”[56]

Witnesses told Human Rights Watch that in many locations, including the area around Damazin, they saw Popular Defense Forces (PDF), an auxiliary force drawn from Fellata and other nomadic ethnic groups whose members Sudan is actively recruiting.[57] Sudan has also deployed large numbers of PDF in Southern Kordofan. According to witnesses, they are active in the Ingessana mountain region and have attacked groups of refugees as they were fleeing.

A 25-year-old woman and her mother-in-law from a village around Gebanit said that they had witnessed multiple attacks by PDF militia at different times during the conflict, most recently in October 2012 as they tried to flee to South Sudan. She said the men, who were not in uniforms, were armed with AK-47s; they shot and killed her brother, a civilian. Previously, in May, the militia raided her village and kidnapped the wife of her brother-in-law.[58]

The Jalaba [Arab nomads] came to our village with cars and starting firing over our heads. I was there. … I ran one direction and she ran the other way into the direction of the Jalaba and she was caught. I saw her being captured and put in the car. They came and shot randomly at people and then just ran off.[59]

She told Human Rights Watch that in June, the militia shot at villagers while they were harvesting and she saw them kidnap three people including two women. She said that she and other villagers had wanted to flee earlier but that the road out of the mountain had been blocked by the militia so they felt captive. After months of sustained bombardments and increasing ground attacks by Sudanese military, they attempted to leave by taking unused routes and walking through thorny grasslands.

Saudi Idris, a 25-year-old woman from a village near Gabaneet, a witness to a separate attack, said that after the militia had burned down their village in June 2012, her community had no choice but to take refuge and live in the surrounding mountains. She said the attack that destroyed her village lasted for five hours after the militia arrived in seven vehicles. “They got down from their cars and they started the fires with a small matchbox. They went house to house and burned each of them down. They burned all our houses, all of our clothes.”[60]

She explained to Human Rights Watch how she and her group of 35 adults were ambushed by militia in October as they tried to flee to South Sudan. The militia shot and killed three of the 20 men in the group at Jabal al-Tien; seven others were missing after the group scattered. “For 15 days we were walking without shoes and water. When they shot at us we just took our kids and ran barefoot,” she said. “We also had no food in Jabal al-Tien. We had taken some seeds with us but they had run out.”

The woman’s mother-in-law, Batul Musa, said she was forced to abandon her mother during the attack. “When we were attacked at Jabal Al-Tiem, I was carrying my elderly mother on my back. I had to throw her on the ground and hide her in the tall grass. I don’t know if she’s alive or dead. Her name is Mariam.”[61]

Under international law, all parties to the conflict are required to take all feasible precautions to minimize civilian casualties during military operations, and deliberate targeting of civilians and extra judicial killings are always strictly prohibited and constitute war crimes.[62]

Arbitrary Arrests, Extrajudicial Executions

In September 2011, as fighting broke out in Damazin and other towns where SPLA-North forces were present, witnesses told Human Rights Watch, government forces rounded up and placed in prolonged detention, verbally and physically abused, and killed civilians based on their presumed ties to SPLM-North and its armed wing, SPLA-North.[63]

A 26-year-old man from Roseris, now living in South Sudan, told Human Rights Watch that national security officers arrested and removed him from his house, accusing him and his 36-year-old brother of being SPLA-North soldiers, and detained them in a crowded cell for more than three weeks. “They tied our hands and put us in the land cruiser and beat us with belts, feet, hands and said, ‘We are going to use you,’ and ‘You will see many things,’” he recalled. “If you complained that people are sick [the commander] would say, ‘Let them die, they are kufar [infidels].”[64]

During his detention, he saw other inmates badly beaten and, on one occasion, he saw a military officer shoot two men in the head at close range outside the cell, killing them instantly. Upon his release, the national security officials pressured him to work with them and ordered him to check in every day; he eventually managed to leave the area.

Issa Daffala Sobahi, a 33-year-old guard for a state minister who is a known SPLM-North member in Damazin, told Human Rights Watch that soldiers arrested him on the morning of September 2, 2011 at the minister’s home, beat and shackled him, and insulted him by calling him “kufar” [infidel] and saying, “You don’t know Allah.” He said they held him in a detention facility in their military compound with other civilians arrested that morning.

“They took people to the river and shot them,” he told Human Rights Watch. “I myself was taken to the river with three others on the second day. They killed two of us.” Soldiers threatened to kill him, but did not. “They said, ‘You are all with Malik [Malik Agar, the SPLM-N governor], we are going to kill you,” he recalled. Later the same day, he saw the soldiers shoot a woman who was carrying a baby as she resisted arrest. He managed to escape from the prison compound that night.[65]

Scores of detainees were released only after being forced to renounce their political affiliation, according to reports from local groups and former detainees. Many people remain in detention because of their real or perceived links to the SPLM-North. The African Center for Justice and Peace studies reported that 92 men have been detained in prisons in Blue Nile and Sennar states since September 2011, mostly because of their real or perceived links to SPLM-North. The detainees have yet to be charged with any crimes, and many reported that they had been beaten while in custody.[66]

In the context of a non-international armed conflict, arbitrary detention – detention not conducted on a lawful basis - is prohibited, and all detentions should comply with the applicable standards on treatment of detainees in both international humanitarian law and human rights law. Sudan should make known the names of all those in detention, their whereabouts, release all those detained without legal basis, and ensure full due process rights and safeguards apply to all those detained on a legal basis .

Refugee Camp Conditions for Women and Girls

As of November 2012, 110,000 refugees from Blue Nile have registered in four refugee camps in South Sudan run by the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCR) and humanitarian agencies, and 30,000 have sought shelter in Ethiopia.[67]

According to refugees at the camps interviewed by Human Rights Watch, female-headed households make up a significant proportion of many of the communities present in the camps – as many as 50 percent of some of the camp communities.[68] Female refugees and protection officers in the Doro camp told Human Rights Watch that female-headed households are one of the groups most vulnerable to exploitation at the camp and are in need of more protection and resources. “It’s very difficult for women to carry their rations after food distributions,” said a female refugee from Surkum. “Sometimes they get help, and sometimes the men ask for money to help. If the women can’t find a way, they have to give away a portion of their rations for the help.”[69]

The reliance on others, particularly male community members, and the lack of livelihood options for female-headed households also makes women more vulnerable to sexual exploitation and abuse. While female-headed households are able to register for camp food distributions, they have no ability or means to buy their children clothes and other basic necessities that are not included in the ration.

The risk of attack while outside the camp is one of the gravest safety and security concerns faced by female refugees. According to a Sexual and Gender-Based Violence Rapid Assessment of the Doro camp released by the Danish Refugee Council in October, 2012, “incidents of physical and sexual assault happen mostly in firewood collection places outside the camp and sometimes at water points within the camp.”[70]

Female refugees expressed similar concerns to Human Rights Watch at the Jamam camp. Aisha A., a 17-year-old member of the Women’s committee, acknowledged that “there are a lot of problems for women and girls here. When women and girls collect wood in forests, men force themselves on the women. [The perpetrators] are the local people from the [host] community. They touch the women by force.”[71]

Women in Jamam camp regularly walk 1.5 hours each way, sometimes alone, at least once a day to collect firewood for cooking and to sell. According to Aisha, the sister of one rape victim had described how the young woman had been raped while collecting firewood outside the camp. She said that the victim had remained silent about the attack and not sought out medical or psychological support. “Some of the women feel ashamed so they never tell anyone. They can only talk about it to a close female friend,” she said.[72] Given such barriers, the total number of cases is not known, however Human Rights Watch was told by service providers and camp residents that the threat of physical harm or rape whilst collecting fire wood was a constant threat and concern.

The proximity of Jamam camp to a South Sudanese military base also has security implications for the women and exposes them to greater risk of sexual violence. Aisha also described an attempted rape of a woman who was milking her cows near a market outside the camp.

She [the victim] told me that a number of soldiers [from the South Sudan army] passed by. One of them came to her and told her that she has to carry his bag, and that he would be taking her home to spend the night with him. He told her ‘you’re not going home tonight.’ He gave her some money and told her to wait at the spot or he will shoot her. After she sat down and cried, her brother and some refugees found her and took her away” before the soldier had returned.[73]

Aid workers told Human Rights Watch that women and girls at the camps faced other gender-based abuses including sexual harassment and domestic violence.[74]

VI. International Response

The international response to humanitarian law and human rights violations in Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile has been muted and largely eclipsed by attention to the deteriorating relations and conflict between Sudan and the newly independent South Sudan.

Neither the AU nor the UN has explicitly condemned Sudan’s indiscriminate bombing, or endorsed the August 2011 findings and recommendations of the UN’s Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights to independently investigate violations of international human rights and humanitarian laws in Southern Kordofan. Governments and international organizations have urged the parties to the conflict to negotiate a ceasefire and agree to aid access, rather than insist on an end to indiscriminate bombing, attacks, and other abuses.

In May 2, 2012, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 2046, adopting an AU roadmap to address the conflict between Sudan and South Sudan, urged Sudan and SPLM-North to accept the Tripartite Proposal, submitted by the AU, UN, and League of Arab States (LAS), to permit humanitarian access in the two states, and to negotiate political and security arrangements with the help of the AU’s High-level Implementation Panel (AUHIP) and Chair of the Intergovernmental Authority on Development IGAD. In August 2012, the parties finally agreed to terms for access, but largely because of Sudan’s inaction, an initial assessment never occurred. International donors and agencies have openly begun to doubt that Sudan will ever allow aid in.

International actors engaged on Sudan need to urgently re-focus attention on the serious human rights violations that underlie and co-exist with the growing humanitarian crisis and press for justice for such crimes. They should seek a UN mandate to establish an international inquiry into all alleged breaches of international humanitarian and human rights law since the conflict started in June 2011. The inquiry should include investigation into the roles of individuals responsible, in both government and rebel forces, with a view to identifying those who bear individual and command responsibility for serious crimes committed. The investigation should also seek to identify those responsible in the Sudanese government for the policy of preventing access to humanitarian aid for the civilian population in the two states.

The lack of justice for serious crimes committed during the North-South conflict and Darfur appears to have emboldened those engaged in the conflicts documented in this report, which are characterized by many of the same tactics. The AU, UN, EU, LAS, and individual states bilaterally should make clear that there will be consequences, including individual sanctions on those responsible for serious violations. They should also call for Sudan to cooperate with the ICC’s investigation into crimes in Darfur, including by ensuring that President Omar al-Bashir, Ahmed Haroun, and other ICC suspects appear before the court to answer the charges against them.

Acknowledgments

Jehanne Henry, senior researcher in the Africa division of Human Rights Watch, and Samer Muscati, emergencies researcher in the Women’s Rights Division (WRD), authored this report based on research conducted in Sudan and South Sudan with Tirana Hassan and Daniel Williams, researchers in the Emergencies division, and Gerry Simpson, advocate in the Refugees division, in August 2011, April 2012, and October 2012.

The report was reviewed and edited by Leslie Lefkow, deputy director of the Africa division, Janet Walsh, deputy director of WRD, and Elise Keppler, senior counsel in the International Justice Program. Babatunde Olugboji, deputy program director, and Aisling Reidy, senior legal advisor, provided program and legal reviews.

Amr Khairy, the Arabic language website and translation coordinator, arranged for translation of this report into Arabic. Kyle Hunter and Matthew Rullo, associates for the Emergencies division and WRD, respectively, assisted with trip planning. Lindsey Hutchison, senior associate in the Africa division, prepared this report for publication, as well as provided editing and formatting assistance. Multimedia production was provided by Michael Onyiego, freelance videographer, Ivy Shen, multimedia production associate, and Jessie Graham, senior multimedia producer. Additional production assistance was provided by Grace Choi, publications director, Kathy Mills, publications specialist, and Fitzroy Hepkins, administrative manager.

Human Rights Watch wishes to thank the scores of victims and witnesses in Sudan, and their relatives, who talked to Human Rights Watch, sometimes at great personal risk, as well as the Sudanese activists who continue to document and report on abuses.

[1]The 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement, between the Sudanese government and the former southern rebel Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army, effectively ended Sudan’s 22-year civil war. The agreement created a national unity government, in which Sudan’s ruling National Congress Party shared power with the SPLM, for a six-year interim period that ended with South Sudan’s independence on July 9, 2011. It also contained special protocols for governing the border states of Southern Kordofan, Blue Nile, and Abyei, known as “the Three Areas.”

[2] See ”Sudan: Political Repression Intensifies,” Human Rights Watch news release, September 21, 2011, http://www.hrw.org/news/2011/09/21/sudan-political-repression-intensifies

[3] Comprehensive Peace Agreement, Chapter V, “The Resolution of the Conflict in Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile States,” available at http://unmis.unmissions.org/Portals/UNMIS/Documents/General/cpa-en.pdf

[4] See Rules 1 and 13 in ICRC Customary International Humanitarian Law, Volume I Rules, Jean-Marie Henckaerts andLouise Doswald-Beck, 2005. This is a customary norm in both international and non-international armed conflict and binding on all parties to the conflict. See also Additional Protocol to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and Relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflict (Additional Protocol I) adopted June 8, 1977, 1125 U.N.T.S. 3, entered into force December 7, 1978, art. 51(5)a.

[5]See “Thirteenth Periodic Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the situation of human rights in Sudan,” August 2011, available at http://www.ohchr.org/EN/Countries/AfricaRegion/Pages/SDPeriodicReports.aspx

[6] See “Sudan: Crisis Conditions in Southern Kordofan,” Human Rights Watch new release, May 4, 2012, http://www.hrw.org/news/2012/05/04/sudan-crisis-conditions-southern-kordofan; “Sudan: Southern Kordofan Civilians Tell of Air Strike Horor,” Human Rights Watch new release, August 30, 2011, http://www.hrw.org/news/2011/08/30/sudan-southern-kordofan-civilians-tell-air-strike-horror

[7] See “Humanitarian Situation Report on South Kordofan and Blue Nile States, Sudan,” South Kordofan & Blue Nile Coordination Unit, 15 October – 15 November 2012, on file with Human Rights Watch.

[8]See Human Rights Watch news releases, footnote 6.

[9] International law prohibits indiscriminate attacks which are those: (a) which are not directed at a specific military objective; (b) which employ a method or means of combat which cannot be directed at a specific military objective; or (c) which employ a method or means of combat the effects of which cannot be limited as required by international humanitarian law; and consequently, in each such case, are of a nature to strike military objectives and civilians or civilian objects without distinction. See Rule 12 in ICRC Customary International Humanitarian Law, Volume I Rules, op. cit.. This is a customary norm in both international and non-international armed conflict and binding on all parties to the conflict. See also Additional Protocol I, art. 51(4).

[10]Sudan has expressed its intention to sign the 2008 Convention on Cluster Munitions, prohibiting cluster munitions, and has denied using them in Southern Kordofan. See ”Sudan: Cluster Bomb Found in Conflict-Zone,” Human Rights Watch news release, May 24, 2012, http://www.hrw.org/news/2012/05/24/sudan-cluster-bomb-found-conflict-zone.

[11]See Rule 1 in ICRC Customary International Humanitarian Law, Volume I Rules, op. cit.; see also Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts (Additional Protocol II), 8 June 1977, 1125 UNTS 609, entered into force December 7, 1978, article 13 (2).

[12]See Rules 15 and 22 in ICRC Customary International Humanitarian Law, Volume I Rules, op. cit.; see also Additional Protocol II, article 13 (1).

[13]Human Rights Watch interview with Fadila Tia Kofi, Lima village, Southern Kordofan, October 31, 2012.

[14]In both Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile states, people habitually used the term “Antonov” to refer to any military aircraft, whereas the Sudanese military uses aircraft of different makes, including Antonovs.