Lonely Servitude

Child Domestic Labor in Morocco

Summary

Latifa L. was 12 years old when she began working as a domestic worker in Casablanca, Morocco’s largest city. She said she was “really scared,” but a recruiter reassured her that her future employers “would be very kind” and would pay her well.

It turned out to be an empty promise.

Once in Casablanca—a five-hour bus journey from home—Latifa discovered that she was the only domestic worker for a family with four children. She said she toiled without a break from six in the morning until midnight, and was charged with cooking, laundry, cleaning floors, washing dishes, and caring for the children, including a two-year-old girl. She had no days off and was only allowed to eat twice daily—at 7 a.m. and at midnight after her work was done—she said. Latifa also said her employer frequently berated her and sometimes beat her, sometimes with a shoe when she broke something or when one of the children cried.

At first she did not tell her parents about the abuses because she felt obliged to help them financially, she told Human Rights Watch. But eventually she had enough. “I don’t mind working,” she said, “but to be beaten and not to have enough food, this is the hardest part of it.” In early 2012 she went to a public phone and asked her father if she could return home. He agreed, and with assistance from a nongovernmental organization (NGO), Latifa was able to return to school.

*****

In Morocco, thousands of children—predominantly girls and some as young as eight—work in private homes as domestic workers. Known as petites bonnes, they typically come from poor, rural areas hoping for a better life in the city and the opportunity to help their family financially. Instead, they often encounter physical and verbal violence, isolation, and seven-day-a-week labor that begins at dawn and continues until late at night. They are poorly paid and almost none attend school.

In 2005, Human Rights Watch issued a report “Inside the Home, Outside the Law: Abuse of Child Domestic Workers in Morocco.” In 2001, tens of thousands of girls under the age of 15—some 13,500 in the greater Casablanca area and up to 86,000 nationwide according to the government and an independent research organization—worked as domestic workers in violation of Moroccan and international law that prohibit employing children under 15. The report documented domestic work by girls as young as five years old, some of whom worked for as little as US4¢ an hour, for 100 or more hours per week, without rest breaks or days off. The girls we interviewed said that their employers frequently beat and verbally abused them, denied them education, and sometimes refused them adequate food or medical care.

This report follows up on our previous work by assessing what progress has been made in eliminating child domestic labor in Morocco since 2005, and what challenges remain. Although no nationwide surveys similar to the 2001 studies are currently available, our 2012 research—including interviews with 20 former child domestic workers in Casablanca and rural sending areas, as well as interviews with nongovernmental organizations, government officials, and other stakeholders—suggests that the number of children working as domestic workers has dropped since 2005, and that fewer girls are working at very young ages. Public education campaigns by the government, NGOs, and United Nations (UN) agencies, together with increased media attention, have raised public awareness regarding child domestic labor and the risks that girls face. “When I first went to Morocco 10 years ago, no one wanted to talk about the issue,” an International Labour Organization (ILO) official said. “Now, child domestic labor is no longer a taboo subject.” Government efforts to increase school enrollment have shown notable success and helped reduce the number of children engaged in child labor.

But while the numbers of child domestic workers have declined, many children—overwhelmingly girls—still enter domestic work at much younger ages than the 15-year-old minimum age limit. Laws prohibiting the employment of children under 15 are still not effectively enforced, and, according to the girls we interviewed, working conditions for those entering domestic work are often abusive and exploitative. Domestic workers generally —children and adults alike—are still excluded from Morocco’s Labor Code, and as a result do not enjoy the rights afforded to other workers, including a minimum wage or limit to their hours of work. Some girls from poor, rural areas are lured into domestic work by deceptive intermediaries and feel pressure to help support their family, particularly, girls said, if a parent has become ill, disabled, or lacks regular income.

As a result, child domestic labor in Morocco remains a serious problem. Further efforts are needed to enforce the country’s legal prohibition against employing children under 15, protect girls who are legally old enough to work, and end the abuse and exploitation of young Moroccan girls in private homes.

Under-Age Employment

Moroccan and international law prohibit employing children under the age of 15. The Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which Morocco ratified in 1993, prohibits economic exploitation and employing children in work that is likely to be hazardous, interfere with their education, or harm their health or development. The ILO Convention No 182 on the Worst Forms of Child Labor, which Morocco ratified in 2001, states that children under 18 may not be employed in work that is likely to harm their health, safety, or morals. Prohibited labor includes work that exposes them to physical, psychological, or sexual abuse; forces them to work for long hours or during the night; or unreasonably confines them to employers’ premises.

Despite this, girls who enter domestic work in Morocco are sometimes much younger than 15. A 2010 survey of domestic workers under 15 from 299 sending families by Institution Nationale de Solidarité avec les Femmes en Détresse (INSAF), the Casablanca-based NGO that works to prevent child domestic labor and to assist former child domestic workers, found that 38 percent of the girls were between the ages of 8 and 12. Of the 20 former child domestic workers whom Human Rights Watch interviewed for this report, 15 had started work at ages 9, 10, or 11. All but four had been employed as domestic workers during some period between 2005 and 2012, the period of our inquiry. The youngest had begun working when she was eight years old.

Deceptive Intermediaries

Intermediaries—as in Latifa’s case—often approach girls’ families as recruiters, typically promising good working conditions and kind employers. Prospective employers typically pay intermediaries 200-500 Moroccan dirhams (US$22-57) for finding a domestic worker. As a result, intermediaries have a financial incentive not only to recruit domestic workers, but also to convince them to change employers periodically so they can collect additional fees.

The girls we interviewed said that intermediaries often told them little in advance about their working conditions or job responsibilities, which often include cooking and preparing meals, dishwashing, doing laundry, washing floors and carpets, shopping for the family, caring for young children, walking older children to and from school, preparing their lunches, and serving guests. Younger girls may initially not be expected to cook, but typically take on such responsibilities as they get older. Girls as young as eight said that they were expected to carry out most of the household responsibilities for families of up to eight members.

Abusive and Exploitative Working Conditions

Child domestic workers may work long hours for very low wages. On average, the girls Human Rights Watch interviewed earned 545 dirhams per month (approximately $61), far below the minimum monthly wage of 2,333 dirhams (approximately $261) for Morocco’s industrial sector. While some girls earned as much as 750 dirhams per month ($84), one said she earned only 100 dirhams ($11), and several did not even know their wages, which are typically negotiated between the parents and the intermediary or prospective employer. In almost every case, the girl received no money directly; her wages were paid directly to her father or another family member.

In addition to the wages paid to a girl’s family, employers typically provide domestic workers with food and accommodation. Although it is difficult to estimate the monetary value of these “in-kind” payments, the evidence gathered for this report suggest that their value does not make up the gap between a typical domestic worker’s cash salary and the prevailing minimum wage. Some child domestic workers said they had private rooms, but others slept in their employer’s living room, in the kitchen, or in a closet, sometimes on a blanket on the floor. Some ate with their employer’s family and received adequate food, while others—like Samira who said she was only given olive oil and bread, or Latifa who said she was only allowed to eat early in the morning and once late at night after she finished her work—often went hungry.

For some child domestic workers, the work day begins early in the morning and does not end until late at night. Although Morocco’s Labor Code sets a limit of 44 hours per week for most workers, the code does not address domestic workers, and therefore sets no limit for domestic work. Some interviewees had free afternoons or evenings, but others began working at 6 a.m. and continued until nearly midnight, with few breaks. One described pressure to work continuously, saying, “The woman [employer] wouldn’t let me sit. Even if I was finished with my tasks … if she saw me sitting, she would shout at me.” Of the twenty former child domestic workers interviewed, only eight said their employer gave them a weekly day of rest. The others said they worked seven days a week, sometimes for up to two years.

Eleven of the twenty girls interviewed said their employers beat them, and fourteen of the twenty described verbal abuse. One girl who began working when she was nine years old said: “[My employer] used every bad word she could think of…. When I didn’t do something as she wanted, she started shouting at me and took me into a room and started beating me. This happened several times a week.” Girls said their employers beat them with their hands, belts, wooden sticks, shoes, and plastic pipes.

The privacy of the home makes child domestic workers uniquely vulnerable to sexual harassment or rape by male household members. Aziza S. said she was only 12 when her employer’s 22-year-old son tried to rape her. Amal K. also told us she experienced sexual violence by the son of her employer when she was 14. “The eldest son came into my room and did things to me,” she said. “He told me not to tell anyone…. I was afraid he would hurt me if I told.”

Domestic work severely limits a child’s ability to continue her education. Of the twenty former child domestic workers interviewed, only two said they had completed the third grade before beginning work. None were allowed to attend school while employed: Souad B., for example, said her employer had refused her request to attend school without giving a reason. A 2010 study by INSAF found that 21 percent of child domestic workers were still in school and worked during school holidays, but that 49 percent had dropped out of school to work and 30 percent had never attended at all.

Child domestic workers we interviewed said they experienced extreme isolation. Most worked in an unfamiliar city, far from family and friends. Some girls speak Tamazight, the Berber language spoken by many people in central Morocco, and cannot easily communicate in Arabic, the language spoken by the majority of Moroccans. Many interviewees said they were not allowed outside their employer’s home and had limited contact with their families while employed. Some said they were allowed to call their families but that their employers monitored their phone conversations so that they could not speak freely.

Few of the 20 former child domestic workers interviewed had any idea where they could turn for help if they experienced violence, ill-treatment, or exploitation. None said they had approached police directly or knew of a government entity that could offer them assistance. Without money and unfamiliar with their surroundings, they could not return home alone. Many described pressure to continue working even under abusive conditions to provide income for their families.

Some eventually appealed to their families for permission to return home. Only two of the girls whom Human Rights Watch interviewed actively sought help outside their own family. One was Aziza S., who said she ran to a local bus stop after her employer’s son tried to rape her. She asked a bus driver for help, and he took her to a local police station. In another case, a girl who had been beaten by her employer with a belt confided in a local hairdresser, who referred her to a local NGO for help.

Progress

According to government statistics, Morocco has made significant progress in recent years in reducing overall rates of child labor and increasing the number of children who attend school. The number of children engaged in all forms of child labor dropped from 517,000 in 1999 to 123,000 in 2011, according to government surveys. The number of children working as domestic workers also appears to have declined, although no recent data is available to establish exact numbers. At the same time, the number of children completing primary school increased—from 62 to 85 percent between 2002 and 2010.

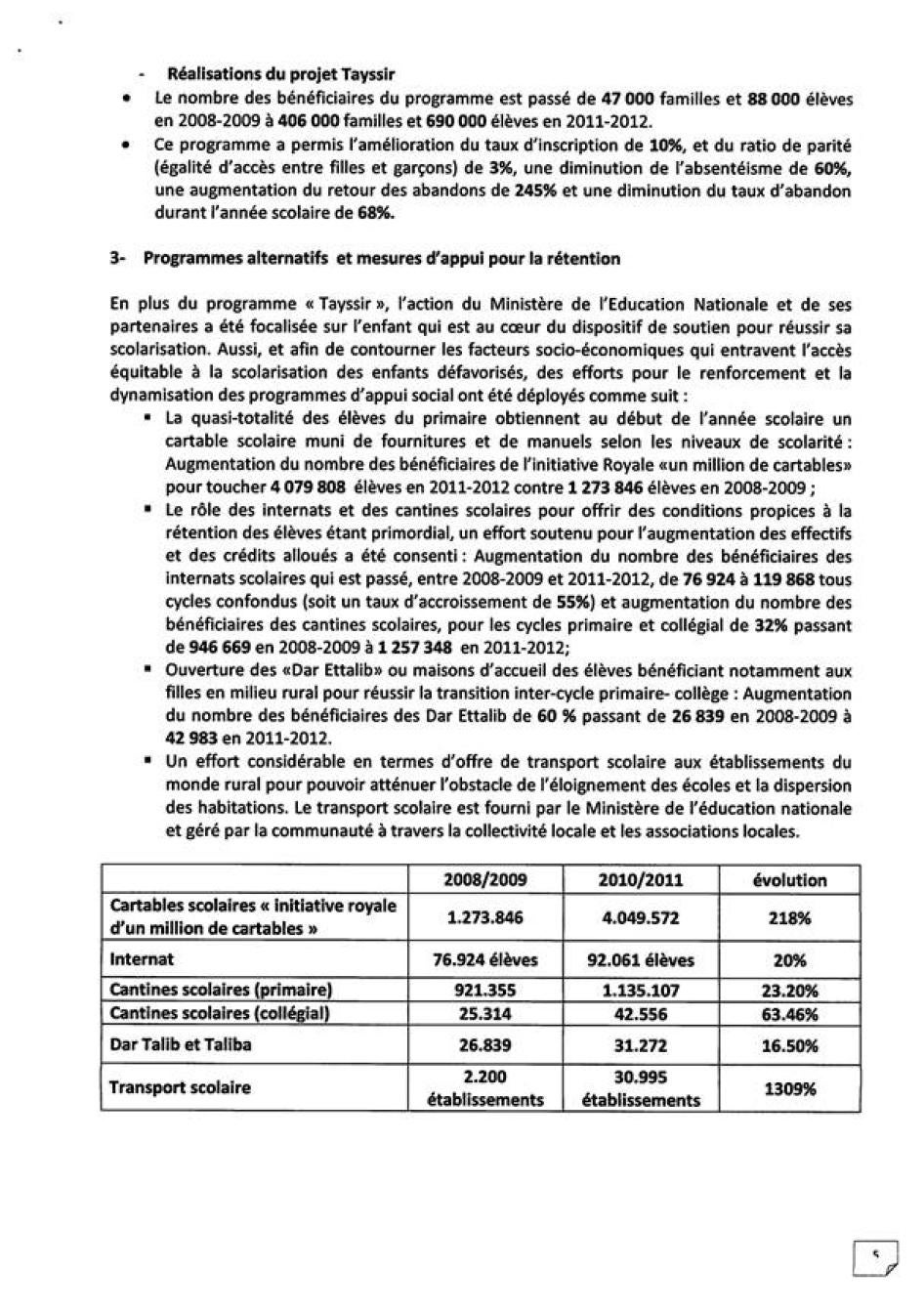

Government efforts to increase school enrollment and provide financial support for poor families that may feel pressure to send their children to work have boosted efforts to reduce child labor. One important initiative has been a cash allowance program that gives 60-140 dirhams ($7-16) to the families as a monthly stipend for each child attending school. According to the Ministry of Education, the program benefited 690,000 students in poor rural areas from 2011 to 2012, and an independent assessment found that it cut drop-out rates among recipients by 68 percent over three years. The government has also provided book bags and other supplies to more than 4 million primary age students and expanded cafeteria meals by 32 percent from 2008 to 2012.

In five cities, the government has set up Child Protection Units to assist children who are victims of violence or mistreatment, which may include child domestic workers who have fled abusive employers. The Ministry of Employment and Professional Development has established a central Child Labor Unit and child labor focal points at 43 inspectorates, and, together with ILO and UNICEF, has trained labor inspectors and other government officials to enforce child labor laws. In 2010, a government decree expanded the types of labor that are considered hazardous and thus prohibited for children under 18. The decree prohibits some tasks relevant to child domestic workers, but does not specifically prohibit children from performing domestic work.

Since 2006, the government has also been developing a draft law on domestic work that would for the first time, formalize the sector and establish key rights (such as a weekly day of rest and annual leave) for domestic workers. The draft law would reinforce the existing legal prohibition on domestic work by children under 15 and require the authorization of a parent or guardian for the employment of children between the ages of 15 and 18. The proposed law requires written contracts for all domestic workers to be filed with the labor inspection office. In May, Minister of Employment and Professional Development Addelouehed Souhail told Human Rights Watch that adopting the law was a government priority in 2012. At the time of writing, however, the law had not yet been presented to parliament.

Moroccan NGOs have also conducted public education campaigns to discourage child domestic labor, including outreach to families in sending communities, and have created programs to assist girls who are employed below the legal age or victim to abuse or exploitation. NGOs also credit national media with helping to decrease child domestic labor by paying greater attention to the issue in recent years.

More Action Needed

Despite these positive steps, existing mechanisms to assist vulnerable children or address child labor are not sufficient to address the unique characteristics of child domestic labor. Labor inspectors, for example, may not access private households to identify child domestic workers. Furthermore, according to government-supplied information inspectors have imposed no fines against employers of child domestic workers. Child Protection Units, intended to assist children who are victim to violence or mistreatment, only operate in five cities. Child domestic workers we interviewed said they were unaware of services that the units might provide, and even the most active unit, in Casablanca, has only assisted a small number of child domestic workers. Criminal prosecutions against employers responsible for physical abuse of child domestic workers are still rare, although in 2012 a woman was sentenced to 10 years in prison for the death of a 10-year-old domestic worker after severe beatings.

The government should establish more effective mechanisms to identify and remove girls who are employed below the minimum age or who are above the minimum age but victim to violence or exploitation. Continued public education is needed to inform both sending families and potential employers about the law and the risks of child domestic labor. According to INSAF’s 2010 study, for example, 76 percent of families in sending areas still were unaware of laws prohibiting the employment of children under age 15.

National legislation to regulate domestic work is needed to ensure that domestic workers of all ages—including girls above the minimum age of employment—enjoy basic labor rights and decent working conditions. The government should amend proposed domestic worker law to comply with the 2011 ILO Convention 189 on Decent Work for Domestic Workers and adopt it quickly.

Human Rights Watch urges Morocco’s government to adopt additional measures to effectively eliminate child domestic labor, taking into account the particular isolation and vulnerability of girls employed as domestic workers. These should include special mechanisms to identify girls subject to illegal, abusive, and exploitative child domestic labor, investigate these cases, and provide appropriate assistance, including shelter, family reunification, re-entry into school, and when appropriate, sanctions or criminal prosecution of employers.

Without such action, young girls will continue to be lured into exploitation and physical abuse in private homes, foregoing their right to an education, family contact, and the opportunity to develop to their fullest potential.

Key Recommendations

To the Moroccan Government

- Strictly enforce 15 as the minimum age for all employment;

- Continue and expand public awareness campaigns regarding child domestic labor and relevant laws;

- Create an effective system to identify and remove child domestic workers who are illegally employed or subject to abuse, provide them with medical and psychosocial assistance, and facilitate their entry into school;

- Amend the proposed domestic worker law to ensure compliance with the 2011 ILO Convention 189 on Decent Work for Domestic Workers, and present the law to Parliament for adoption;

- Ensure that all children under the age of 15 enjoy their right to a free and compulsory basic education, and expand initiatives which are designed to increase school enrollment among girls who are vulnerable to child domestic labor;

- Prosecute individuals under the Moroccan Criminal Code who are responsible for violence or other criminal offenses against child domestic workers.

Detailed recommendations can be found at the end of this report.

Methodology

This report is based on research conducted between April 2012 and August 2012, including two field visits to Morocco in April and May and in July of 2012. We conducted interviews in Casablanca, Rabat, Marrakech, and the Imintanoute region of Chichaoua province, speaking with former child domestic workers, government officials, lawyers, teachers, and representatives of NGOs, UNICEF, and the International Labor Organization.

We interviewed 20 former child domestic workers who ranged in age from 12 to 25 at the time of interview, and who began working as domestic workers between the ages of 8 and 15. All but 4 of the 20 were still under the age of 18 at the time of the interview. They had worked in a total of 35 households for periods ranging from 1 week to 2.5 years. All but four had been employed as a domestic worker during some period between 2005 and 2012, the period of our inquiry. Those whose employment was prior to 2005 (with a few exceptions, as noted) are not quoted in this report.

We interviewed seven former child domestic workers in Casablanca, Morocco’s largest city, where many child domestic workers find employment, and the remainder in the Imintanoute region, a poor, rural area southwest of Marrakech which is known as a sending area for child domestic workers. Interviewees were identified with the assistance of NGOs that provide programs and services for former child domestic workers. Interviews were conducted in private in Arabic or Tamazight (Berber), with interpretation provided by a Human Rights Watch research assistant. Interviews were given on a voluntary basis, and no incentives were offered or provided to persons interviewed. We have changed the names of all former child domestic workers quoted in this report in order to protect their privacy.

Former child domestic workers who have left domestic work and are in NGO programs may be more likely to have suffered abuse or exploitation and therefore may not be considered representative of the general population of child domestic workers. Thus, the interviews in this report are not necessarily typical of all child domestic workers in Morocco, but their experiences are illustrative of the challenges and abuses that many child domestic workers may face.

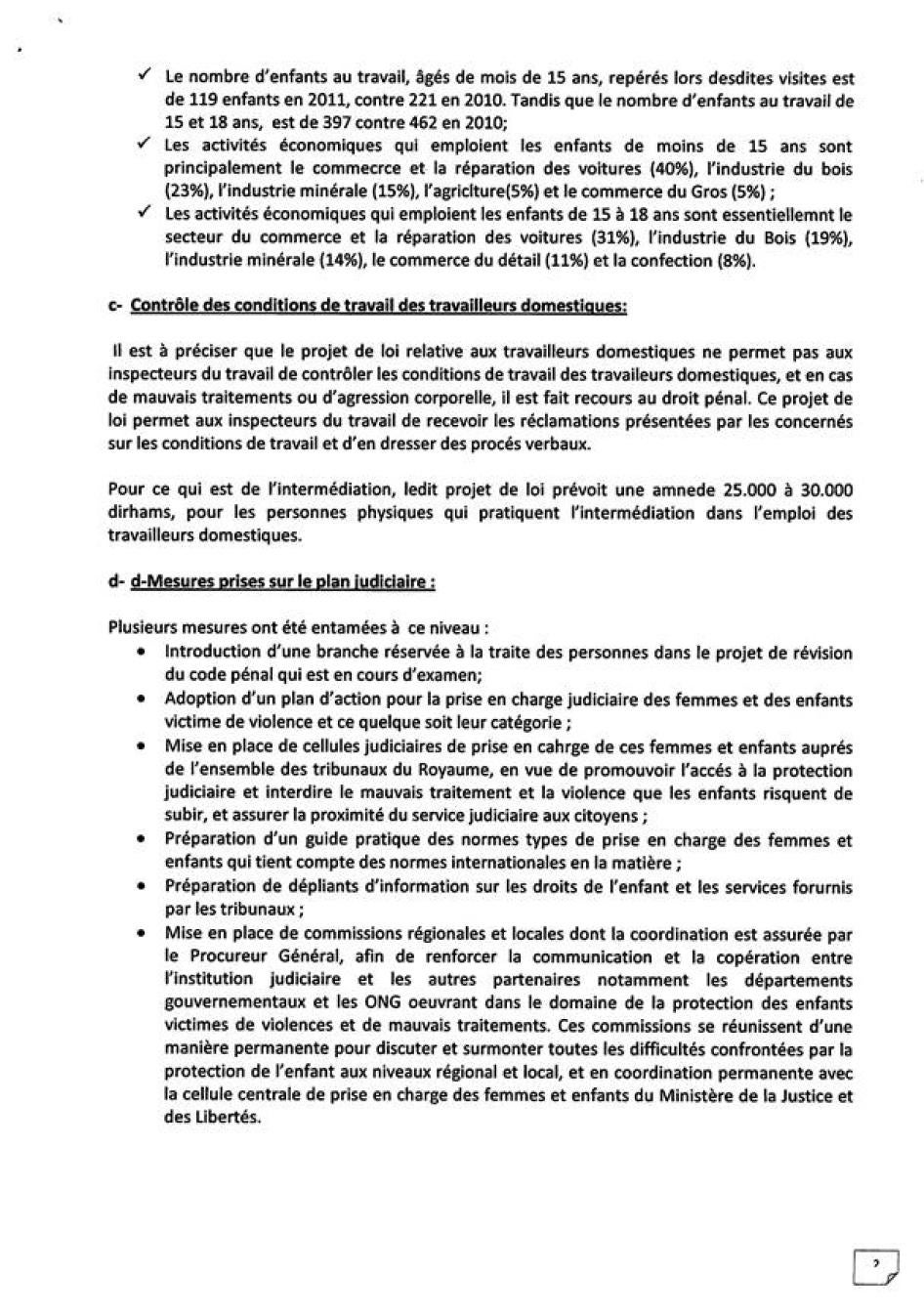

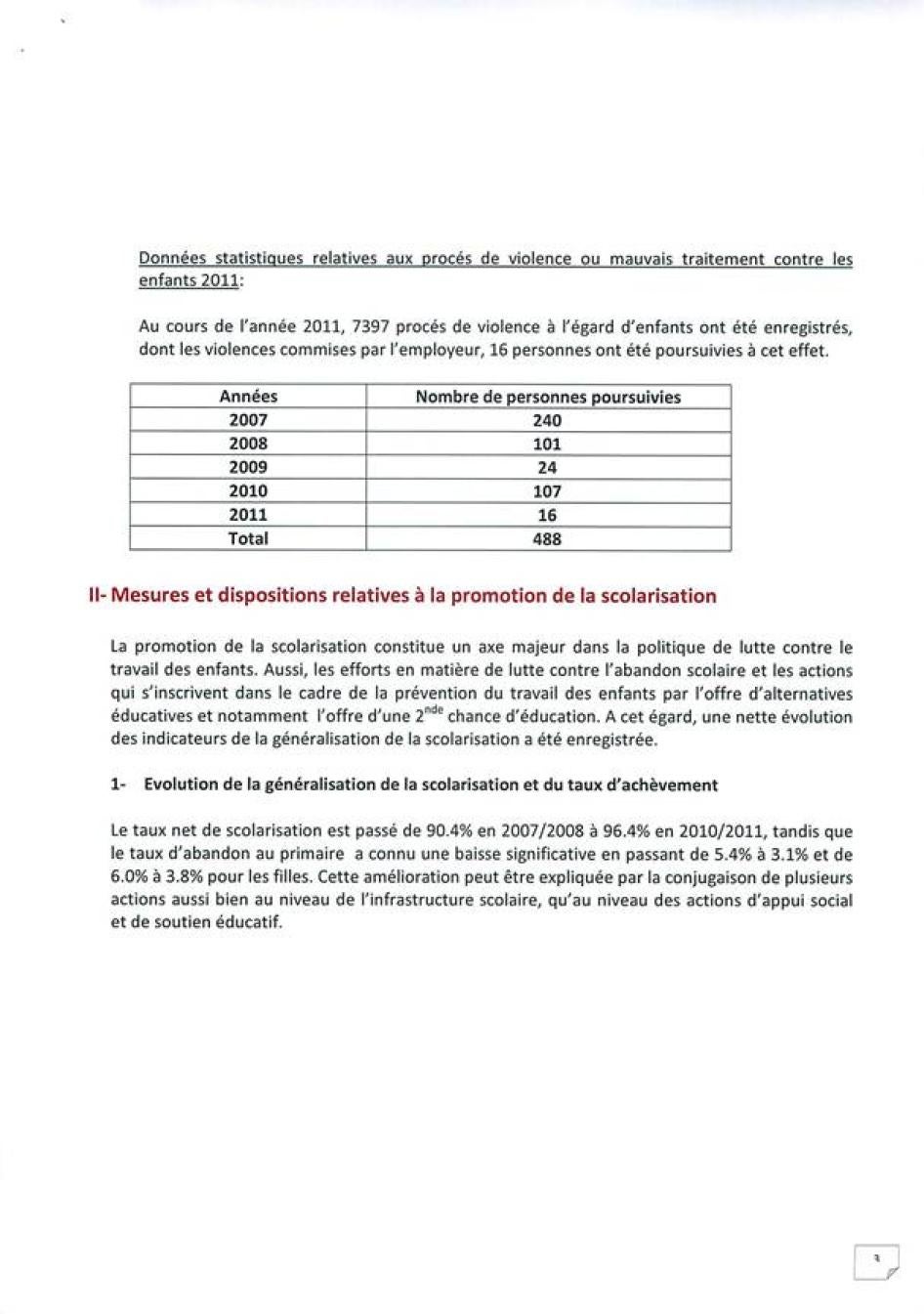

During our field mission, Human Rights Watch met with the minister of employment and professional training; the minister of solidarity, women, family, and social development; and representatives of the Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Health, Ministry of Education, Ministry of Higher Education, and the General Council of the government. We also met with staff of the Casablanca Child Protection Unit (CPU), which operates under the direction of the Ministry of Solidarity, Women, Family, and Social Development, and the independent National Human Rights Council. Following our field mission, we requested additional information through the Interministerial Delegation for Human Rights (a governmental body set up in 2011 to elaborate and implement government policy on human rights) regarding existing government initiatives to address child domestic labor and enforcement of relevant existing laws. Information received from the Interministerial Delegation as of June 15, 2012, is reflected in the body of the report and reprinted in the appendix. We also reviewed available secondary sources, including available surveys, government reports, NGO reports, news stories in the media, and other relevant materials.

Despite the cooperation noted above, authorities impeded our work by informing us at the beginning of 2012 that they would not allow our Morocco-based research assistant, Brahim Elansari, to attend any meeting between Human Rights Watch and government officials. Despite Human Rights Watch’s protests that it alone should decide who is to represent it, authorities have refused to lift its ban on Mr. Elansari’s participation in official meetings and events.

In this report, “child” and “children” are used to refer to anyone under the age of 18, consistent with usage under international law.

This is Human Rights Watch’s second report on child domestic labor in Morocco, and our 20th report documenting abuses against domestic workers, including both children and migrant domestic workers, who are often more vulnerable to abuse and exploitation compared to other domestic workers. We have documented abuses against child domestic workers in El Salvador, Guatemala, Guinea, Indonesia, Morocco, and Togo, and abuses against migrant domestic workers in Bahrain, Cambodia, Indonesia, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Malaysia, Singapore, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and the United States.

This is also our 43rd report on child labor. In addition to the work noted above relating to child domestic labor, we have investigated bonded child labor in India and Pakistan, the failure to protect child farmworkers in the United States, child labor in Egypt’s cotton fields, child labor in artisanal gold mining in Mali, the exploitation of migrant child tobacco workers in Kazakhstan, the use of child labor in Ecuador’s banana sector, the use of child labor in sugarcane cultivation in El Salvador, child trafficking in Togo, the economic exploitation of children as a consequence of the genocide in Rwanda, and the forced or compulsory recruitment of children for use in armed conflict—one of the worst forms of child labor—in Angola, Burma, Burundi, Chad, Colombia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, India, Liberia, Nepal, Somalia, Sri Lanka, Sudan, and Uganda.

I. Child Domestic Work in Morocco

Globally, the International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that between 50 and 100 million people —at least 83 percent women and girls—work as domestic workers.[1] Across Africa and the Middle East, domestic work makes up an estimated 4.9 percent (Africa) to 8 percent (Middle East) of total employment.[2] Over 15 million domestic workers are children under age 18, making up nearly 30 percent of all domestic workers worldwide.[3]

Currently, there are no accurate statistics regarding the numbers of children working as domestic workers in Morocco. No specific surveys on child domestic work have been conducted since 2001, when a government survey found that 23,000 girls under the age of 18 (including 13,580 girls under age 15) worked as child domestic workers in the greater Casablanca area alone. A 2001 study by the Norwegian-based Fafo Institute for Applied Social Science estimated that nationally between 66,000 and 86,000 girls under 15 were working as domestic workers.[4] The government of Morocco reported to the ILO that it planned a new survey on child domestic workers in greater Casablanca in 2010, with results and data to be extrapolated to the national level.[5] In June 2012, the government reported that the survey was being prepared, but had not yet been completed.[6]

Despite the lack of credible data, the number of child domestic workers in Morocco appears to be on the decline. Virtually all of the actors whom Human Rights Watch interviewed, including local NGOs, UNICEF, ILO, local teachers, and government officials, reported that the practice appears to be less common than when Human Rights Watch published its first report in 2005.

NGOs and other organizations point to several reasons for the decline, including efforts by NGOs, UN agencies and the government to raise public awareness about the dangers of child domestic work; increased attention to the phenomenon by the Moroccan media (including coverage of high-profile criminal cases against employers for abuses against child domestic workers such as the death of a 10-year-old child domestic worker named Khadija in 2011); and government and NGO efforts to expand educational opportunities and keep children in school, particularly targeting poor rural areas that are common sending areas for child domestic workers.

The Moroccan High Commission for Planning, a ministerial entity with primary responsibility for producing economic, social, and demographic statistics, reported a substantial decline in child labor generally between 1999 and 2011. [7] Based on surveys of 60,000 families, it found that in 2011, 2.5 percent of children between ages 7 and 15 were working (a total of 123,000 children), compared to 9.7 percent of the age group (517,000 children) who were working in 1999. [8] The survey found that 91.7 percent of child labor was in rural areas, and that 6 in 10 working children were male. The survey estimated that 10,000 children under age 15 were working in the cities (compared to 65,000 in 1999), and of these, 54.3 percent (or approximately 5,430) were working in “services,” which could include domestic work. [9]

While the High Commission for Planning annual survey suggests a much lower number of child domestic workers than found by the 2001 surveys, both NGOs and UN agencies expressed skepticism about the relevance of the findings for child domestic work. A UNICEF representative said, “We are concerned about the statistics. The survey does not cover all children involved in child labor, such as children in invisible work like domestic work.”[10] UNICEF stressed the need for accurate statistics on child domestic labor, based on clear indicators and methodology that would effectively identify children working in the sector.[11] The president of INSAF said, “If you look at the official figures, they do not correspond to what we have experienced on the ground. We don’t have concrete numbers, but our feeling is that the problem is bigger than the official reports.”[12] UN and other independent studies have found that household surveys often underestimate the extent of child labor, particularly in the illegal or informal sectors, because of household members’ unwillingness to report such labor.[13]The government, in its 2012 report to the Committee on the Rights of the Child, also acknowledged that the “real scale is still hard to quantify due to several reasons: it is “clandestine”; labor inspectors are unable to go inside houses; and thirdly, it is difficult for these young and often illiterate girls who come from rural areas to have access to redress mechanisms.” [14]

Despite evidence that child labor generally and child domestic labor specifically is on the decline, Human Rights Watch’s findings suggest that child domestic labor is still a serious problem in Morocco. Continuing efforts are needed to eliminate it.

Characteristics of Child Domestic Workers: Age, Origin, and Schooling

The vast majority of child domestic workers in Morocco come from poor rural areas to work in larger cities such as Casablanca, Rabat, Marrakech, Tangiers, Agadir, or Fes. Some of these girls begin working at ages as young as eight or nine. The 2001 government survey of child domestic workers in greater Casablanca found that 59.2 percent of the girls were under the age of 15. A 2010 study by INSAF surveying child domestic workers under the age of 15 from 299 sending families found that 62 percent were between the ages of 13 and 15, and 38 percent between the ages of 8 and 12.[15] Of the 20 former child domestic workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch, the youngest began working at age 8, and 15 (or 75 percent of those interviewed) began work at ages 9, 10, or 11. (Due to the small number of those interviewed and how interviewees were identified, however, this group should not be considered a representative sample.)

Although Moroccan law requires compulsory education until age 15, child domestic workers typically have little schooling. Of the twenty former child domestic workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch, only two had completed the third grade before beginning to work. Most told us they only attended one or two years of school before going to work, and six (30 percent of those interviewed) had never attended school at all.

Similarly, the 2010 INSAF survey of child domestic workers found that 30 percent of those surveyed had never attended school. Forty-nine percent of the child domestic workers INSAF surveyed had dropped out of school, while 21 percent were still in school but worked during school holidays. While 43 percent of the girls left school for financial reasons, 25 percent cited the distance between the school and their home as a reason for not continuing their education.[16]

Virtually all of the child domestic workers in Morocco are girls. Domestic work is a highly gendered sector of employment, traditionally regarded as “women’s work” because of its focus on cooking, housecleaning, child care, and other tasks carried out within the home. The ILO estimates that domestic workers are overwhelmingly female—83 percent worldwide. [17]

Reasons for Working

The majority of girls interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they entered domestic work because they believed their family needed the income they could provide. Karima R., who began working at age 10, told Human Rights Watch, “I went to work because my family was poor. I needed to help my family.” [18] In some cases, the parents’ income was not enough to support the family, while in others, girls went to work when a parent died, or their fathers became ill or disabled and were no longer able to work, leaving their children’s domestic work as the family’s only source of income. Nadia R., for example, explained that her father was a farmer, and that “when there was rain there was work, but when there was no rain, there was no work.” [19]

INSAF’s 2010 survey of 299 “sending” families in 5 regions of Morocco found that only 9 percent of the families had any regular income and that 94 percent of the mothers and 72 percent of the fathers were illiterate.[20]

Although some of the girls interviewed said they were reluctant to leave school, many nonetheless expressed a strong sense of obligation to help their family. Najat S. left school in grade three when she was nine years old. She said, “My father was sick, so my mother asked me and my sister to work. I wanted to continue my studies, but when I saw my father was sick, I wanted to work.” [21] Zohra H.’s father died when she was 10. She said when an intermediary came to their house proposing that Zohra go to work as a domestic worker, her mother initially refused, but Zohra convinced her that she wanted to work in order to help the family. [22]

In other cases, the girls had no desire to work, but felt they had no choice. Amina K. was 10 when she first started working as a domestic worker. She said, “My father asked me to go to work. He didn’t say why. I didn’t want to go and didn’t know where I was going, but my father forced me to go.”[23]

The girls often agreed to work without any understanding of the conditions or treatment they would endure. In many cases, intermediaries approach families with job opportunities, typically promising good working conditions. Nadia R., for example, was told that her prospective employers were teachers and would treat her well.[24] An intermediary told Latifa L. that her employers would be “very kind.”[25] Malika S. said that she knew other girls her age who were working as domestic workers, but that “they were telling me only the good things, not how the treatment really was.”[26] Leila E. said, “I was happy to go to work and I thought that nothing bad would happen to me.”[27]

Recruitment into Domestic Work

The Role of Intermediaries

Intermediaries work as brokers, arranging for girls from poor rural areas to work in the cities as domestic workers, and receiving fees from the employers for finding domestic workers to work in their homes. Once an agreement is reached, the intermediary typically accompanies the girl, often by bus, to the employer’s home.

Of the 20 former child domestic workers Human Rights Watch interviewed, 10 reported that an intermediary arranged for at least 1 of their jobs. Most did not know the amount of the intermediary’s fee, but one girl reported that her employer had paid 200 dirhams (US$23), while another said that in her case, her employer paid 500 dirhams ($57). Local NGOs reported that fees may range up to 1500 dirhams ($167).[28] NGOs report that in some cases, the families of child domestic workers are also expected to pay the intermediary. If the family does not have the money in advance, the girl is expected to work without salary for one to three months in order to cover the fee.[29]

Malika S. described the process in her case: “The intermediary came to my village and came to my house and asked if I wanted to work. He was a man from another place, not from my village. He said the family would take me and treat me well.”[30]

Although most girls knew that they were to be employed as domestic workers, some intermediaries deceived the girls and their families about the nature of their employment. Fatima K. was told that she would only be answering phones, and instead, found herself responsible for household tasks for a family of eight.[31] Hanan E. went to Agadir at age 11, believing that she was going to stay with a family and attend school. When she arrived, she realized she was expected to do domestic work instead. When Hanan told her employer that her father had said she was there to study, the woman replied that “he did not know the arrangement.”[32]

Because intermediaries only receive fees upon the placement of a domestic worker, it is also to their advantage to convince the domestic worker and her family to change employers so that they can collect more fees. Aicha E. worked 14 hours a day for a verbally abusive employer before being placed in a much better situation with an employer who treated her well and did not expect her to work extremely long hours. Aicha said, “The woman treated me like her daughter. I liked working there.”[33] Aicha was only allowed to stay with that employer for a few months, however, before an intermediary convinced her father that she could get a better salary elsewhere. The next employer, like the first, was abusive and forced her to work from 7 a.m. until 11 p.m.

Other Recruitment

Girls may also be recruited for domestic employment through casual or family networks. For example, Najat S. said that a woman from a neighboring village who was not an intermediary approached her family after her father fell sick regarding another family that was looking for a domestic worker.[34] Rabia M. also said she found out about her job from a woman in a neighboring village who was not an intermediary.[35] Fatima K.’s job was arranged by a friend of her father’s.[36] Souad B.’s job was arranged by her older sister, who was already working as a domestic worker in Casablanca, she told us.[37]

In other cases, former child domestic workers said they did not know how their employment was arranged and that the negotiations were typically handled by their parents. The girls often knew little about their employers or working conditions until they arrived at their employer’s household.

II. The Life of a Child Domestic Worker

Fatima K. started working when she was nine, she told Human Rights Watch.[38] She was told that her job would be answering phones, but on arrival in Casablanca, she realized that she would be the only domestic worker in a household with five children. She was expected to wake before dawn to make breakfast for the children and work non-stop until 11 p.m. She prepared meals, washed dishes, cleaned the floor, took care of the employer’s baby, did shopping, and served guests. “I got very tired,” she said.

Fatima’s employer beat her and verbally abused her. “At the beginning, she was just slapping me,” Fatima said, “but the second time, she used a plastic plumbing pipe. She beat me when I broke something or when I got in a dispute with her son. She slapped me on my face and on my shoulder.”

When Fatima fell ill, she said, she didn’t dare ask her employer for medicine or to take her to the doctor. “If I asked her [for medicine], she would say that I was there to work, not to be taken care of, and if she gave me medicine, she would deduct the cost from my salary,” she said.

Fatima worked for the employer for two years with no holidays. “The most difficult part was not seeing my mother during that period,” she said. “I didn’t even get to talk to her on the telephone.”

*****

Girls employed as domestic workers are responsible for a range of household tasks, depending on their age. They may cook and prepare meals, wash dishes, do laundry, wash floors and carpets, do shopping for the family, care for young children, walk older children to and from school, help them prepare their lunches, and serve guests. Younger girls are often not expected to cook but may be expected to take on such responsibilities as they get older. Fatima said that initially, she did little cooking, only preparing simple dishes such as eggs, but within six months, was asked to prepare more complicated dishes and to cook couscous. [39]

Girls who begin work at young ages often find themselves unprepared for such responsibilities. At age 11, Hanan E. was expected to care for a baby, but said she didn’t know how.[40] Zohra H. initially didn’t know how to do laundry and said she asked her mother to teach her when she was allowed to go home to visit.[41]

Most of the girls interviewed were the only domestic worker employed by the household, and in some cases, were expected to carry out most of the household tasks for families of up to eight members. In a few cases, the family employed more than one domestic worker to share the tasks.

Long Hours and Lack of Rest

Although the Moroccan Labor Code sets 44 hours per week as the limit for the industrial sector, there is no minimum set by law for the hours worked by domestic workers. As a result, child domestic workers are at the mercy of their employer. A few described working just a few hours a day or having several hours off in the afternoon or evening, while others began working early in the morning and did not finish until evening, with little opportunity for rest. In the most extreme cases, girls described beginning work at 6 a.m. and continuing until midnight. The child domestic worker often was expected to be the first one up in the morning and the last person to bed at night. Fatima K. said, “The woman would not accept it if she came into the kitchen in the morning and found that I was not there.” [42] She described the pressure to work continuously: “The woman [the employer] wouldn’t let me sit. Even if I was finished with my tasks she wouldn’t let me sit. I had to act as if I was working because if she saw me sitting, she would shout at me.” [43] Malika S., who began working at age 11, typically began work at 6 a.m. She said, “The house was big. In this house, you never stop working. When I finished cleaning the floor, the woman asked me to do it again.” [44]

Most of the girls worked seven days a week with no day off. Najat S., who started work at age nine, said she worked for two years without receiving a day off or the chance to go home to visit her family.[45] Hanan E., who started work at age eleven, also told us she worked for more than two years with no days off. She typically worked from 5 or 6 in the morning until midnight. If she tried to rest, her employer would shout at her. Hanan said, “I felt very tired and that the woman did not care about me.”[46]

Wage Exploitation

As of July 1, 2011, the minimum wage for the industrial sector in Morocco was 2,230.80 dirhams (US$254) per month. It increased to 2,333.76 dirhams ($265) per month on July 1, 2012.[47] No minimum wage is currently established for domestic work.

The girls interviewed by Human Rights Watch, on average, earned 545 dirhams ($61) per month, barely one-quarter of the minimum wage for industrial jobs, often for working hours far in excess of the 44 hours per week set by the labor code for the industrial sector. While some earned as much as 750 dirhams ($84) per month, Nadia R. told us she earned only 100 dirhams ($11) per month and several said that they had no idea of their wages. In almost all cases, their wages were negotiated by an intermediary or their parents, and were paid directly to their parents.

In addition to their cash salary, domestic workers who live with their employers are also provided with room and board, which is discussed below. Although it is difficult to estimate the monetary value of these “in-kind” payments, the evidence gathered for this report suggests that their value does not come close to making up the gap between a typical domestic worker’s cash salary and the prevailing minimum wage. International standards state that payments in kind should represent only a limited portion of domestic worker’s remuneration.[48]

Beginning at age nine, Najat S. spent two years working in a Casablanca household for 350 dirhams ($40) per month, she told Human Rights Watch. Her employer allowed her a few hours rest in the afternoon, but she still typically worked 12 hours a day, 7 days a week, for a total of 84 hours per week. On an hourly basis, her wages averaged about 1 dirham ($0.11) per hour, less than 10 percent of Morocco’s formal minimum wage.[49]

Hanan E. said she earned 250 dirhams ($28) per month while working for more than two years without a day off. She said she typically worked 18 hours a day, from 5 or 6 a.m. until midnight, or over 120 hours per week, for less than half a dirham per hour. After she left the job, her father told her that her employer had reduced her wages over time, paying even less than the agreed 250 dirhams per month, claiming that she was deducting money to cover clothes and food for Hanan. Hanan said that the employer never bought her clothes and that the food she provided was often inedible.[50]

Several girls expressed fear that their employer would deduct money from their wages and that this would cause hardships for their families. Fatima K. did not know how much her family received for her work, but said that when she became ill, she did not ask her employer for medicine for fear that the cost would be deducted from her salary. She once broke a vase that belonged to her employer, and said, “The woman threatened to tell my father, so when I saw him, I told him that everything was okay. I wanted to tell him that I wanted to come home, but I never did because I was afraid the woman would tell him about the vase and she would deduct the cost from my wages.”[51]

Girls who worked in multiple households reported that their wages typically increased over time. Even after years of employment, however, only one former child domestic worker reported receiving more than 750 dirhams per month. Even at this wage, however, such an experienced domestic worker made only 34 percent of the minimum wage of the formal sector, often for far longer hours of work.

None of the girls interviewed said they received any spending money of their own. Latifa L. said that if there was some money left after she finished shopping for the family, she would use it to call her family from a public phone.[52] Although most of the girls said that their employer provided them with essentials like soap and toothpaste, very few of the girls said that their employer provided them with clothes or other items. Amina M. said that when she needed soap or shampoo, sometimes her employer would provide them, but not always. “Sometimes I’d ask but she refused, so I stopped asking.”[53] Zohra H. said that she brought personal items and toiletries from her family’s home when she visited.[54]

Verbal and Physical Violence

The majority of the former child domestic workers Human Rights Watch interviewed described both verbal and physical abuse by their employers. Fatima K. said: “The woman beat me whenever I did something she didn’t like. She beat me with anything she found in front of her. Sometimes with a wooden stick, sometimes with her hand, sometimes with a plastic pipe. When I asked her not to beat me with such things, she would say, “It’s not up to you what I can beat you with.”[55]

Aziza S., who started working in Casablanca when she was nine, said, “The woman never spoke to me with respect. She used every bad word she could think of. She talked to me badly. When I didn’t do something as she wanted, she started shouting at me and took me into a room and started beating me. This happened several times a week. She beat me with her hands and pinched me. Once she beat me with a stick.”[56]

Employers beat girls if tasks were not completed to their satisfaction or if the girl broke something, the girls told us. In some instances, girls took the blame for incidents involving the employers’ children. Fatima K. said that once her employer slapped her on the face because the employer’s daughter broke a laptop computer. “I wasn’t even there,” said Fatima, “but the woman blamed me.”[57]

The 20 former child domestic workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch worked in a total of 35 different households. They reported physical beatings in 19 of those 35 households and verbal abuse, typically shouting or insults, in 24 of 35.

Sexual Violence and Harassment

The isolation of child domestic workers in private homes puts them at particular risk of sexual violence from male members of the household in which they work. Aziza S., 13, said she started working in Casablanca when she was 9. Her employer had two sons; the eldest was 22 years old. Aziza told Human Rights Watch: “One time when the woman traveled, the son got drunk and tried to rape me. I pushed back and ran away.… I didn’t know where the police were, but there was a bus stop near my employer’s house. I ran to the bus stop and told the bus driver my story. He took me to the police.”[58]

The police took Aziza to a shelter run by social services; she never returned to her employer and said she did not know if the police conducted an investigation.

Fatima K., now fifteen, worked at a house in Casablanca for two years beginning when she was nine. She said that her employer’s oldest son, age 20, would often beat her and that once when she was alone in the house, he entered from the back door and approached her from behind, covering her mouth with his hand. Her employer came home before he did anything further, but Fatima said that she was afraid of being alone with him.[59]

Amal K., now 25, worked for several households beginning when she was 9 years old. [60] She told Human Rights Watch that she was sexually assaulted in two of the households where she worked. She said when she was 14: “The eldest son came into my room and did things to me. He told me not to tell anyone. I didn’t tell anyone. I was afraid he would hurt me if I told.” One of the other sons once tried to force her to kiss him in the kitchen, she told us.

Amal also described an assault that took place in a different household when she was 19:

In one house where I worked, the husband tried to rape me. He grabbed me by force and tried to take off my clothes. The woman came in and he slapped me on the face. He said he was punishing me because I was not willing to do some work. I didn’t tell the woman what really happened because I was frightened that he might do something bad to me. I was 19 years old. In that case, I was an adult, so what would happen to someone who was younger?[61]

Food Deprivation and Living Conditions

Several of the girls said their employers did not give them enough food and that they were often hungry. Hanan E. said her employer sometimes gave her leftovers that had become inedible.[62] Samira B. said that she was given olive oil and bread twice a day. “I didn’t get breakfast until I cleaned the floor, did the other morning tasks, and cooked lunch. I didn’t get dinner until the family slept. The family ate lunch but didn’t leave me any food.”[63] Samira’s employer often beat her, and she said that even though she was often hungry, she didn’t ask for more food because she was scared.

Latifa L. also said she received only two meals a day. She ate breakfast at 7 in the morning, but had no other food until receiving dinner at around midnight. She finally left the house because, she said, “I felt tired and there was not enough food. I don’t mind working, but to be beaten and not to have enough food, this is the hardest part of it.”[64]

A few girls reported that they ate with their employer’s family and received the same food as the family ate, while others said they ate separately, often eating what was left over from the employers’ meal. If there was no food left over, sometimes the girls would be allowed to prepare something else, but in other cases, the girl would simply not eat. Zohra H. said that for breakfast, she was given cheese and a bit of bread, and for lunch, she ate eggs, tomato, and onion. She received no food after lunch. When the family had dinner, they did not give her any food. She said she was sometimes hungry but didn’t ask for more. “I was shy and I was afraid that she [the employer] would beat me if I asked her.”[65]

Some of the girls had their own room and their own bed to sleep in at night, but others said they slept on the couch in the living room, in a closet, or on the floor. For nearly a year, Zohra slept on the floor in a closet, with one blanket to sleep on, and another to cover herself. She said, “At night it was sometimes cold.”[66] Samira B. said she slept on blankets on the kitchen floor.[67]

Isolation

Child domestic workers often travel long distances from their homes to work as domestic workers. Girls interviewed by Human Rights Watch typically found themselves in a strange city, where they knew no one apart from their employers’ families. Many of the girls were not allowed outside of their employer’s home.

Many child domestic workers interviewed said they had limited or no contact with their own families during their employment. Fatima K. worked for her employer for two years, beginning at age nine, without seeing or speaking to her mother.[68] In other cases, girls were allowed to call their families, but their employer stayed near the phone during the call to monitor their conversations so that the girls were not allowed to speak freely. Leila E. was an exception: she said her employer bought her a cellphone so that she could speak to her family once a week.[69]

Malika S. said that her employer repeatedly refused her requests to contact her father. Finally she lied and said she was ill so that she could call her brother. Once she reached him, she asked him to come fetch her.[70] Hafida H. was able to speak with her family once a week by telephone and go home to visit for two weeks each year. However, she said that she was not able to get used to living at her employer’s house and said that, “I felt like I was living in a prison.”[71]

Most of the girls Human Rights Watch interviewed, even those enduring routine violence and exhausting working conditions, said they did not consider running away. They stayed because they were not familiar with the city and did not know where to go or who to approach for help. Aziza S., who started working in Casablanca when she was nine, explained, “I never thought about it [running away], because I didn’t know the neighborhood. I didn’t know anyone. I only knew what I could see from the window.”[72] Some of the girls also faced language barriers if they spoke Tamazight and did not understand Arabic, the language spoken by the majority of Moroccans.

Lack of Access to Education

None of the child domestic workers Human Rights Watch interviewed were allowed to attend school by their employers. Karima R. said, “My employer told my parents I would be allowed to go to school, but I never was able to go. The woman never told me why.”[73] Souad B. said she once asked her employer if she could attend school, but her employer refused without giving a reason.[74] Although a few of the girls interviewed initially were promised an education, most of the girls entered domestic work knowing that they were hired to work and had no expectation of going to school.

For some, seeing the children of their employer or other children in the neighborhood attend school when they had no such opportunity was particularly difficult. When Karima R. was asked about the most difficult aspect of being a domestic worker, she replied, “The hardest part was when I saw other girls going to school and I was forced to stay at the house.” [75]

Lack of Protection and Pressure to Keep Working

Few of the girls described any government intervention in their situations, including those employed illegally because they were under the minimum age for employment and those who experienced physical or psychological abuse.

None of the girls interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they approached the police or knew of any government entity that could offer them assistance. Only two dared to appeal outside their family for assistance. Aziza S. fled her employer’s home when the employer’s son tried to rape her. She said, “I didn’t know where the police were, but there was a bus stop near my employer’s house. I ran to the bus stop and told the bus driver my story. He took me to the police.”[76] She said the police then took her to social services. At age 10, Karima R. worked for an employer who, she said, verbally abused her and treated her badly. Karima heard about Bayti, an NGO that assists vulnerable children, from a local hairdresser. When her employer beat her with a belt, Karima told the hairdresser, who took her to Bayti.[77]

A social assistant[78] working with former child domestic workers said:

The majority of the girls do not know of any kind of assistance or of any law that protects them if they are subject to violence. Some flee and try to find their intermediary or go home, if they know the way. Sometimes they get lost. Often girls change household because of how they are treated, or they lie to the employer and give a pretext, for example, that their mother is sick, so they can go home.[79]

In some cases of underage employment or abusive treatment, NGOs intervene. For example, Bayti came to the house where Souad B. worked to speak with her about her working conditions after Souad’s older sister, who also worked as a domestic worker in Casablanca, asked the organization to check on Souad.[80] In other cases Human Rights Watch documented, INSAF, the NGO described above, approached the families of girl domestic workers to educate them about the risks of domestic work and to offer monthly stipends if they agreed to bring their daughters home and enroll them in school.

A number of girls said they left their employer by appealing to their families to allow them to come home. Some families agreed only reluctantly, or tried to convince the girl to keep working, even under abusive conditions, in order to maintain income for the family. For example, Amina K., who began working at age 10, said, “It was difficult to convince my father to let me go,” she said. “I told him that the woman was beating me and wouldn’t let me leave the house.” Even once Amina returned home, she said her father wanted her to go to work someplace else, but she refused. “He tried to convince me, but I was tired of working.” [81]

Nadia R. started working at age 12 because her father was making only an irregular income in agriculture. After a month, she said, she came home and told her family that she wanted to go to school and didn’t want to work. “They tried to convince me to stay at the employer’s house, but I refused, so they sent another sister to work for the same family.”[82]

Some of the girls continued to work, enduring physical violence and exhausting working conditions without complaint because of their sense of obligation to their family. Hanan E., who said she would often work from 5 or 6 a.m. until midnight and that her employer often beat her, told us she did not tell her parents the truth about her situation. “I told them everything was okay. I didn’t want them to be sad.”[83]

Positive Experiences

Some of the former child domestic workers described positive experiences with their employers. As mentioned above, Leila E. said that her employer bought her a cell phone so that she could call her family once a week, and that on Sundays, the children in the family often invited her to accompany them to the beach.[84] Rabia M. said that her employer sometimes took her out for sweets in the afternoon.[85] Yasmina M. said that on her day off, Sundays, a daughter from the house took her to the hammam (public bath).[86]

Malika S. worked in three different households by the time she was twelve. She said that the third household was the best: “They were kind with me. They treated me well, they took me outside, they took me with them when they went places. I did the same tasks in that house as the others, but the woman was helping me. I didn’t have any days off, but the work wasn’t hard.”[87]

However, even when treated kindly by their employers, former child domestic workers often described the difficulty of being separated from their family, their sadness at not attending school, and their belief that such work was inappropriate for young girls. Najat S., who began work at age nine, had several hours of rest every afternoon and said that her employers were “nice.” However, she said she missed her family a lot and often cried because she was lonely.[88] All of the girls Human Rights Watch interviewed believed that domestic work was not appropriate for children. Rabia M., age 14, said, “They are too young and they work hard. This kind of work should only be for older people.”[89]

The Future

Sixteen of the twenty former child domestic workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch were back in school through the assistance of INSAF and Bayti, NGOs that assist former child domestic workers. The others were working in other jobs or receiving vocational training through the Association Solidarité Feminine, another NGO. Without exception, the girls who were back in school said they were happy to be studying. None expressed a desire to return to domestic work. Malika R. said, “I don’t like working in houses. In all the houses where I worked, the children were going to school.... Now I am happy I am going to school.” [90]

Najat S. said that in the future, she hopes to become an architect or an engineer. Rabia M. and Zohra H. both said they wanted to become a teacher.[91] Fatima K., who worked in three different households, said, “I would like to do a job to keep girls from working as child domestic workers because I know how they feel.” Hanan E., who was repeatedly beaten by her employer, said she wanted to become a police investigator. “If you are a police investigator, you defend and protect yourself,” she said. “You don’t have to wait for someone else to defend and protect you.”

III. Legal Framework

Moroccan Law

Morocco’s Labor Code sets 15 as the minimum age for employment. Employing children under the age of 15 is sanctionable by fines ranging from 25,000 to 30,000 dirhams ($2,811 to $3,373). In the case of repeated offenses, the fine may be doubled, or the employer may be sentenced to prison for up to three months.[92] Employers who physically abuse child domestic workers are subject to prosecution under Morocco’s Criminal Code. For example, individuals who willfully injure a child or deprive a child of food or care can be imprisoned for one to three years, and adults who have custody of a child and perpetrate such abuse may be subject to two to five years’ imprisonment.[93]

On December 29, 2004, Morocco issued a decree outlining specific forms of dangerous work prohibited for children under the age of 18. On November 16, 2010, it issued a revised decree, further elaborating types of labor that are prohibited for children. The new decree added new elements relevant to child domestic workers, for example, exposure to dangerous biological agents or other dangerous chemicals (for example, harsh chemicals that may be used for cleaning), carrying weights above 8 kg (for girls age 15) or weights above 10 kg (for girls 16 and 17); tasks that expose females to the risk of falling or slipping; or tasks where the person has to squat or bend over constantly.[94] It does not specifically prohibit children from performing domestic work.

Domestic workers are excluded from Morocco’s Labor Code and therefore do not enjoy many of the basic rights extended to workers in the formal sector and in agriculture. Under the Labor Code, other workers are guaranteed a minimum wage (with one set for industry, trade and other professions, and another set for the agricultural sector), enjoy a standard work week of 44 hours (for non-agricultural workers), with a daily work period not to exceed 10 hours. Employees must also receive a full day of rest each week.

In 2006, the government began preparing a draft law to regulate domestic work. The law was approved by the Government Council on October 12, 2011, and submitted to Parliament on October 27, 2011. Following elections in November 2011, the new government decided to re-examine it.[95] In May 2012, the Minister of Employment and Professional Training, Addelouehed Souhail, told Human Rights Watch that adopting the law was a “priority” for his ministry and for the government,[96] but at the time of writing, the law had not yet been adopted.

Like the existing Labor Code, the draft law explicitly forbids the employment of children under the age of 15 as domestic workers, and specifies that any individual employing a child under the age of 15 for domestic work may be subject to a fine of 25,000 to 30,000 dirhams ($2,811 to $3,373). Repeated offenses are punishable by fines of 50,000 to 60,000 dirhams ($5,622 to $6,746) and imprisonment of one to three months.

New provisions in the draft law that are not included in existing law include required authorization by a guardian for the employment of children between 15 and 18 for domestic work, and fines of 25,000 to 30,000 dirhams ($2,811 to $3,373) for intermediaries and any person who employs a child between the ages of 15 and 18 without the authorization of their guardian.

The draft law also specifies working conditions for domestic workers generally, which affect children who are above age 15 and thus legally able to work. For example, the draft law states that domestic workers should not be given work that involves excessive danger, exceeds the capacity of the worker, or could affect morally accepted behavior. However, the specified fines for violating this provision are very low: only 300 to 500 dirhams.

Other key provisions of the draft law include the following:

- A requirement for an employment contract, signed by both the worker and employer and deposited with a labor inspection office;

- A weekly rest period of 24 consecutive hours;

- Annual paid holiday of a day and a half for each month of work;

- Rest during national and religious holidays and time off for family events;

- Compensation in the event of dismissal after at least one year of service.[97]

The draft law is a welcome effort to extend labor protections to domestic workers. However, the draft law is not fully in compliance with the ILO Convention 189 Concerning Decent Work for Domestic Workers (“Domestic Workers Convention”), a new international labor treaty adopted in 2011 to establish international standards for domestic work. For example, the Domestic Worker Convention specifies that working hours for domestic workers should be equivalent to those for other sectors. Although the Moroccan Labor Code sets 44 hours per week as the limit for other workers, the draft law does not set any limits to the hours of work for domestic workers.

The Domestic Workers Convention also specifies that domestic workers should enjoy minimum wage coverage where it exists. The draft law, in contrast, states that wages for domestic workers should not be less than 50 percent of the minimum wage for the industrial sector. In meetings with Human Rights Watch, officials from the Ministry of Employment and Vocational Training explained that “in-kind” payments to domestic workers, including food and accommodation, could account for the remaining 50 percent. The convention, however, specifies that payments in kind should be a “limited” proportion of domestic workers’ remuneration, and the recommendation associated with the convention further specifies that a limit should be set on in-kind payments to allow a salary necessary for the maintenance of domestic workers and their families.[98]

The proposed law allows the accumulation of weekly rest (for up to two months), yearly leave (for up to two years) and the postponement of a worker’s entitled rest for national or religious holidays. Such accumulation provisions can lead to workers being legally forced to work for long periods without breaks, impeding their right to adequate rest. ILO Recommendation 201 accompanying the Domestic Workers Convention recommends that weekly rest not be accumulated for more than 14 days.[99]

NGOs have also criticized the draft law for not including mechanisms to identify and remove child domestic workers from illegal, exploitative, or abusive work situations, and for not providing them with rehabilitative services.[100]

International Law

Several international instruments relate to child domestic work, including the following:

Convention on the Rights of the Child: Morocco ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child in June 1993. The convention states that children have a right “to be protected from economic exploitation and from performing any work that is likely to be hazardous or to interfere with the child’s education, or to be harmful to the child’s health or physical, mental, spiritual, moral or social development.”[101] The convention requires governments to take appropriate legislative, administrative, social, and educational measures in this regard, and especially to provide for a minimum age of employment, appropriate regulation of work hours and conditions of employment, and appropriate sanctions to ensure enforcement.[102]

The Committee on the Rights of the Child last reviewed Morocco’s compliance with the Convention on the Rights of the Child in 2003. The Committee said that it was “deeply concerned” at the situation of child domestic workers in Morocco and urged the government to take all necessary measures to prevent and end the practice of children working as domestic servants, through a comprehensive strategy.[103]

The government of Morocco submitted its third periodic report on compliance with the Convention on the Rights of the Child in mid-2012. The Committee will likely review the report in 2013.

Worst Forms of Child Labor Convention: Morocco ratified the ILO Convention 182 Concerning the Prohibition and Immediate Elimination of the Worst Forms of Child Labor (“Worst Forms of Child Labor Convention”) on January 26, 2001. The Convention obliges all ratifying states to “secure the prohibition and elimination of the worst forms of child labour as a matter of urgency.”[104] It is one of the most widely ratified labor conventions, with 174 states parties.

The Convention prohibits “slavery or practices similar to slavery, such as the sale and trafficking of children,” “forced or compulsory labor,” as well as “work which, by its nature of the circumstances in which it is carried out, is likely to harm the health, safety or morals of children.” [105] Exactly what constitutes such types of work is left to be determined by states parties, in consultation with employer and worker organizations and in consideration of international standards, in particular the ILO Worst Forms of Child Labor Recommendation. This recommendation, also adopted in 1999, outlines factors which should be considered in determining the worst forms of child labor. Of particular relevance to child domestic work, the recommendation suggests that work “which exposes children to physical, emotional or sexual abuse” and “work under particularly difficult conditions, such as work for long hours or during the night, or work which does not allow for the possibility of returning home each day” should be considered among the worst forms of child labor. [106]

In 2011, the ILO Committee of Experts on the Application of Conventions and Recommendations noted measures taken by the Moroccan government to implement the Worst forms of Child Labor Convention, but expressed its deep concern at the “exploitation” of children under the age of 18 as domestic workers in conditions similar to slavery or under other hazardous conditions. The Committee reminded the government that work done under such conditions should be eliminated as a matter of urgency and also urged the government to adopt the domestic worker bill as a matter of urgency. It requested the government to take immediate steps to conduct thorough investigations and robust prosecutions of persons who subject children under age 18 to forced or hazardous domestic labor and urged that “sufficiently effective and dissuasive penalties are imposed in practice.”[107]

Domestic Workers Convention: In June 2011, members of the International Labour Organization voted overwhelmingly to adopt ILO Convention 189 Concerning Decent Work for Domestic Workers (Domestic Workers Convention), the first international treaty to establish global labor standards for domestic workers.[108] Under the Convention, domestic workers are entitled to the same basic labor rights as other workers in their country, including weekly days off, minimum wage coverage, limits to their hours of work, overtime compensation, social security, and clear information on the terms and conditions of work. The convention obliges governments to take measures to protect domestic workers from violence and abuse, and to regulate private employment agencies that recruit and employ domestic workers.

Regarding children, the Convention requires governments to set a minimum age for domestic work that is in line with the ILO’s Minimum Age Convention[109] and Worst Forms of Child Labor Convention, and to ensure that domestic work performed by children under the age of 18 but above the minimum age of employment does not does not deprive them of compulsory education or interfere with opportunities to participate in further education or vocational training.[110]

To provide further guidance to states, the ILO also adopted a non-binding Recommendation 201 Concerning Decent Work for Domestic Workers (Domestic Workers Recommendation). The recommendation urges states to identify types of domestic work that, by their nature or the circumstances in which they are carried out, are likely to harm the health, safety, or morals of children, and to prohibit and eliminate such child labor.[111] The recommendation also urges states to take special measures to protect domestic workers above the minimum age of employment but below the age of 18, including by:

- strictly limiting their hours of work to ensure adequate time for rest, education and training, leisure activities and family contacts;

- prohibiting night work;

- placing restrictions on work that is excessively demanding, whether physically or psychologically; and

- establishing or strengthening mechanisms to monitor their working and living conditions.[112]

Morocco voted in favor of adoption of the Domestic Workers Convention at the International Labor Conference in June 2011, but as of October 2012, had not yet ratified the Convention. The Minister of Employment and Vocational Training, Addelouehed Souhail, told Human Rights Watch in May 2012 that as soon as Morocco adopts its domestic law on domestic workers, it will ratify the Domestic Workers Convention.[113]

IV. Moroccan Government Efforts to Address Child Domestic Labor

Education

Education in Morocco is free and compulsory until age 15. The 2011 Constitution stipulates that basic education is the right of a child and an obligation of the family and state. [114] Moroccan law further specifies that all children should be registered for school at age six, and that parents and guardians are responsible to ensure school attendance until age fifteen. Those that do not comply may be subject to a fine of 120-800 dirhams (US$13-90). [115]

Although the compulsory schooling law is poorly enforced, the Moroccan government has made significant efforts to increase school enrollment for Moroccan children. Increasing school enrollment and retention not only helps fulfill Morocco’s obligation to ensure children’s right to education, it can also help reduce child domestic labor, as girls who remain in school are less likely to enter domestic work.

According to government statistics cited by the World Bank, in 2002 only 62 percent of Moroccan children (56 percent of girls and 67 percent of boys) finished primary school.[116] By 2010, that figure had risen to an estimated 85 percent. Gender gaps also narrowed, with 82 percent of girls and 87 percent of boys completing primary school in 2010. Between 2007 and 2010, the number of primary school-aged children who were out of school decreased from 380,029 to 207,749.[117]

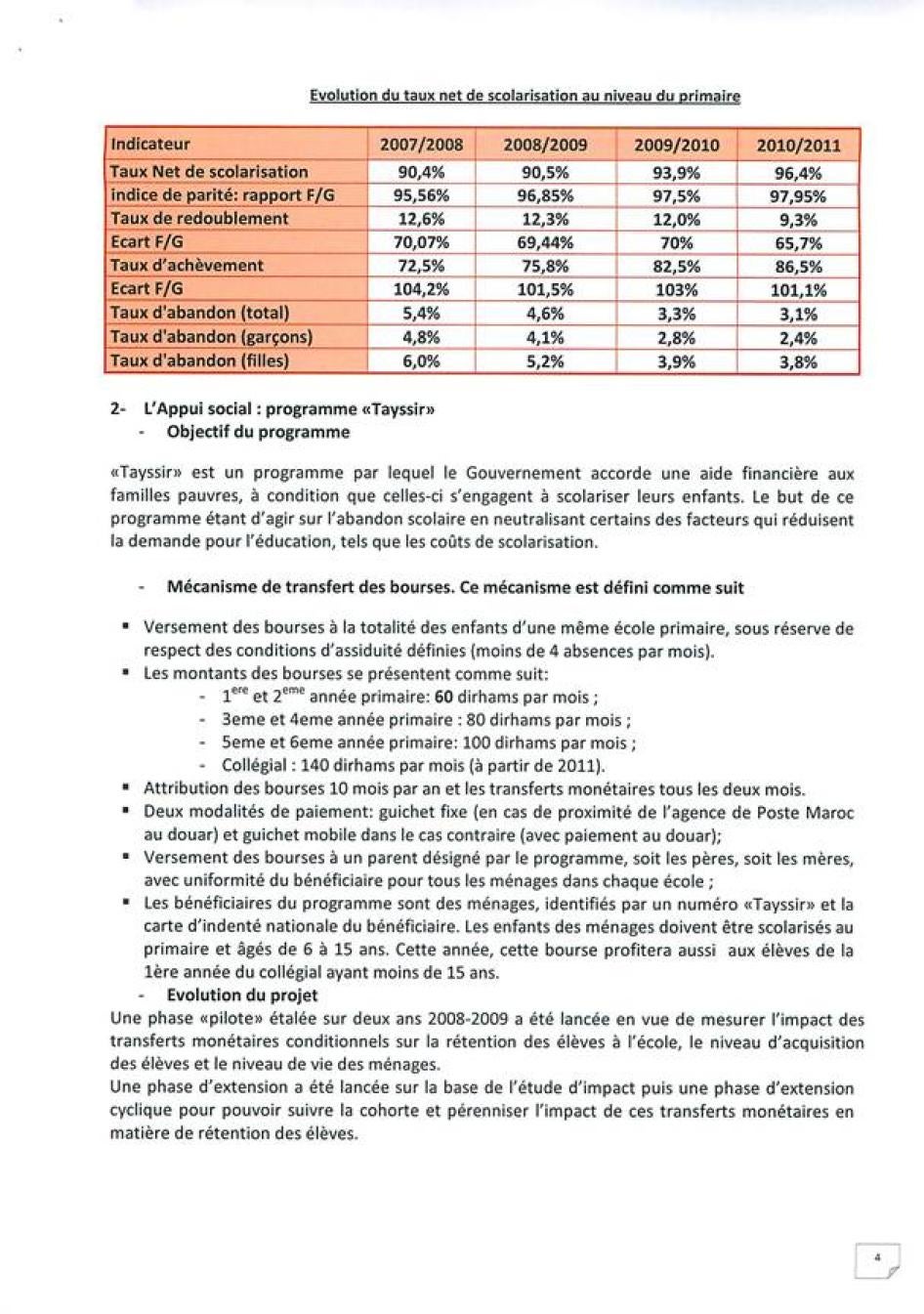

In 2008, the government launched the “Tayssir” program to provide financial help to poor families, on the condition that they send their children to school. The goal of the program was to increase school enrollment by alleviating schooling costs and financial pressures on families to send their children to work. Monthly cash allowances were given to families of children who missed no more than four days of school per month, ranging from 60 dirhams ($7) per month for children in the first or second year of primary school to 140 dirhams ($16) per month for those in middle school.[118]

The Tayssir program began with 88,000 students from 47,000 families in poor, rural areas as beneficiaries. By the 2011-2012 school year, it had expanded to included 690,000 students from 406,000 families.[119] According to the government, the program decreased absenteeism by 60 percent and the annual dropout rate by 68 percent. It also increased the return of students who had previously dropped out of school by 245 percent.[120]