Summary

We were fired on repeatedly. I saw people killed in a way I have never imagined. I saw 30 killed people on the spot. I pushed myself under a rock and slept there. I could feel people sleeping around me. I realized what I thought were people sleeping around me were actually dead bodies. I woke up and I was alone.

– Hamdiya, 14 years old

Saudi border guards have killed at least hundreds of Ethiopian migrants and asylum seekers who tried to cross the Yemen-Saudi border between March 2022 and June 2023. Human Rights Watch research indicates that, at time of writing, the killings are continuing. Saudi border guards have used explosive weapons and shot people at close range, including women and children, in a pattern that is widespread and systematic. If committed as part of a Saudi government policy to murder migrants, these killings would be a crime against humanity. In some instances, Saudi border guards first asked survivors in which limb of their body they preferred to be shot, before shooting them at close range. Saudi border guards also fired explosive weapons at migrants who had just been released from temporary Saudi detention and were attempting to flee back to Yemen.

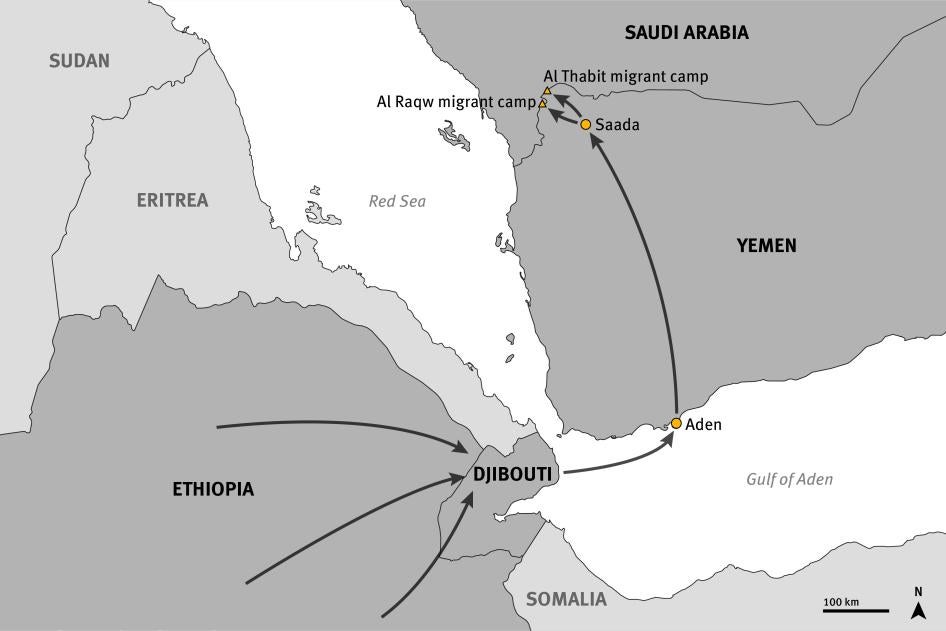

It is estimated that approximately 750,000 Ethiopians live and work in Saudi Arabia. While many migrate for economic reasons, a number have fled because of serious human rights abuses by their government, including during the recent, brutal armed conflict in northern Ethiopia. Ethiopian migrants have for decades attempted the dangerous migration route – known as the “Eastern Route” or sometimes the “Yemeni Route” – from the Horn of Africa, across the Gulf of Aden, through Yemen and into Saudi Arabia. It is estimated that well over 90 percent of the migrants on this route are Ethiopian. The route is also used by migrants from Somalia and Eritrea, and occasionally other east African nations. In recent years, there has been an increase in the proportion of women and girls migrating on the eastern route.

Migrants and asylum seekers described their journey to the Yemen-Saudi border as rife with abuse and controlled by a network of smugglers and traffickers who physically assaulted them to extort payments from family members or contacts in Ethiopia or Saudi Arabia.

Since the armed conflict began in Yemen in 2014, both the government and the Houthi armed group have detained migrants in poor conditions and exposed them to abuse. In 2014, Human Rights Watch documented abuses, including torture, of migrants in detention camps in Yemen run by traffickers attempting to extort payments. In 2018, Human Rights Watch documented how Yemeni guards tortured and raped Ethiopian and other migrants and asylum seekers from the Horn of Africa at a detention center in Aden and worked in collaboration with smugglers to deport migrants in large groups to dangerous conditions at sea. In 2021, Human Rights Watch documented how scores of mostly Ethiopian migrants burned to death after Houthi forces launched projectiles into an immigration detention center in Sana’a, which they controlled, causing a fire. Yemen is also home to one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises, with the vast majority of the population reliant on aid to survive.

Between January and June 2023, Human Rights Watch interviewed 42 Ethiopian migrants and asylum seekers by telephone, who tried to cross the border between Saudi Arabia and Yemen, or the friends and relatives of those who tried to cross. All attempted border crossings between March 2022 and June 2023. Human Rights Watch also analyzed over 350 videos and photographs posted to social media or gathered from other sources filmed between May 12, 2021 and July 18, 2023, and several hundred square kilometers of satellite imagery captured between February 2022 and July 2023. These show dead and wounded migrants on the trails, in camps and in medical facilities, how burial sites near the migrant camps grew in size, the expanding Saudi Arabian border security infrastructure, and the routes currently used by the migrants to attempt border crossings.

Migrants and asylum seekers told Human Rights Watch that after crossing the Gulf of Aden from Djibouti to Aden on often life-threatening journeys, in unseaworthy vessels, overcrowded and with limited food and water, Yemeni smugglers separated them into groups according to their Ethiopian ethnicity. Smugglers then took them to Saada governorate, currently under the control of the Houthi armed group, also known as Ansar Allah, on the border with Saudi Arabia. Smugglers took ethnic Tigrayans to an informal migrant settlement camp called Al Raqw and ethnic Oromo to a camp called Al Thabit, both in Saada.

Many interviewees said Houthi forces controlled the entry and exit into the camps and worked with smugglers to control their stay in Saada. Houthi forces would often extort bribes from the migrants or transfer them to what migrants described as detention centers where people were abused, until they could pay an exit fee. Sometimes, Houthi forces would collect migrants injured during their crossing into Saudi Arabia from hospitals in Saada even when they were injured from an attempted crossing, and forcibly return them to smugglers in the camps.

Interviewees said that the camps in Saada contained tens of thousands of migrants waiting their turn to cross the border into Saudi Arabia. Men, women, and children regularly make crossing attempts in groups of up to 200 people. Migrants who traveled in large groups told Human Rights Watch that their groups had more women than men and a number of unaccompanied children. Those unable to pay the smuggler fees in full were often forced to lead the group and consequently were the most likely to be injured or killed by explosive weapons attacks or shootings.

Saudi border guards were often sighted either patrolling the border area holding rifles or in “cars” or large vehicles with what interviewees said looked like rocket launchers mounted on the rear. Many migrants said they saw cameras tracking their movements mounted on what looked like “street lamps” on the Saudi side of the border.

Border Killings

While Human Rights Watch has previously documented killings of migrants at the border with Yemen and Saudi Arabia since 2014, the killings documented in this report appear to be a deliberate escalation in both the number and manner of targeted killings. This report shows how the pattern of abuses has changed from an apparent practice of occasional shootings and mass detentions to widespread and systematic killings. Such killings would be crimes against humanity if they are both widespread and systematic and part of a state policy of deliberate murder of a civilian population.

Migrants and asylum seekers described the following violations as they attempted to cross into Saudi Arabia.

Explosive Weapon Attacks

People traveling in groups, from four to five people to up to several hundred described being attacked by mortar projectiles and other explosive weapons by Saudi border guards once they had crossed the border from Yemen into Saudi Arabia. In total, Human Rights Watch interviewees described 28 explosive weapons incidents. After leaving camps near the border, migrants would approach or cross the border, often making multiple attempts over a period of months after being “pushed back” by Saudi border guards. Interviewees described seeing Saudi border guards, border guard posts and surveillance cameras and attempting to evade detection, for example by crossing during morning prayers. Human Rights Watch has identified what appear to be border guard posts from satellite images that are consistent with these accounts.

Interviewees had encountered Houthi forces in and travelling to the camps, but consistently described being attacked by Saudi border guards, often describing their uniforms and frequently referring to the effects of explosive weapons being “like a bomb,” mortar or rocket launchers being fired from the “back of cars.” Attacks sometimes lasted for hours or even days.

Once the attacks stopped, survivors were often then approached by Saudi border guards and detained, sometimes for months, by Saudi authorities in Saudi detention facilities. All described scenes of horror: women, men, and children strewn across the mountainous landscape severely injured, dismembered, or already dead. Many who said they managed to escape described the guilt of not being able to carry victims to safety, often after having been severely injured themselves.

Members of the Independent Forensic Expert Group (IFEG) of the International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims, an international group of prominent forensic experts, analyzed videos and photographs both collected from social media by or sent directly to Human Rights Watch showing injured or dead migrants to determine the causes of their wounds. IFEG members concluded that some injuries exhibited “clear patterns consistent with the explosion of munitions with capacity to produce heat and fragmentation,” while others have “characteristics consistent with gunshot wounds” and, in one instance, “burns are visible.”

Large Group Crossings and Deaths

Human Rights Watch interviewed 23 people who attempted to cross into Saudi Arabia as part of large groups that came under fire from explosive weapons. This included one person who watched another group come under fire the day before he attempted to cross, giving a total of 24 large group incidents. The dates and groups sizes indicate that these were all separate incidents. In total, 3,442 people were estimated to have taken part in these large crossings. Ten interviewees estimated that from 11 attempted crossings with a total of 1,278 migrants, they had seen killed or estimated at least 655 deaths. In one of these incidents, a survivor explained that from his group of 170 people, “I know 90 people were killed, because some returned to that place to pick up the dead bodies – they counted around 90 dead bodies.”

For nine additional attempted large group crossings, involving an estimated 1,630 people, interviewees saw people dying around them, but were often too busy fleeing or too traumatized to give an estimate of the number of deaths and instead said how many people returned to the camps. In these nine cases, out of 1,630 migrants, interviewees recounted that 281 people had survived. For example, one interviewee explained “from 150, only 7 people survived that day… There were remains of people everywhere, scattered everywhere.” Another interviewee went to the Saudi border to collect the body of a girl from his village and said “Her body was piled up on top of 20 bodies” explaining that “it is really impossible to count the number. It is beyond the imagination. People are going in different groups day to day. The dead bodies are there.” For the remaining four large group crossings that came under fire from heavy weapons, interviewees were not able to estimate the number of dead or known survivors.

This means Saudi border guards have killed hundreds, possibly thousands, of Ethiopian migrants and asylum seekers.

Small Group Crossings

While Saudi border guards fired explosive weapons at four small group crossings of ten people or less, interviewees said they witnessed no deaths as a result.

Shootings at Close Range

People traveling in smaller groups or on their own said once they crossed the Yemeni-Saudi border they would see Saudi border guards either at a distance in patrol vehicles or sometimes at close range carrying rifles. Many said the border guards shot at them immediately or the border guards would let them approach further into Saudi territory, ask them where they were going, and then fire their rifles at them. Interviewees describe being apprehended by armed border guards and asked in which limb of their body they would prefer to be shot and then the border guard would shoot this limb. People also described guards beating them with rocks and metal bars.

The abuses of Saudi border guards extend beyond firing explosive weapons and shooting at migrants at close range. Some migrants said that after an attack with explosive weapons was complete, the Saudi border guards would descend from their border guard posts and beat survivors. A 17-year-old boy described how Saudi border guards forced him and other survivors to rape two girl survivors after the guards had executed another survivor who refused.

Consequences of Attacks

Human Rights Watch interviewed many people who lost one or more limbs as a result of explosive weapons or shootings at the border and remain stranded in Yemen with limited or no health care and resources to leave. People described an absence of medical treatment at both Al Thabit and Al Raqw camps and Al Gar village, where survivors usually returned after an attack. Some made it to hospitals in Saada and other more severe cases to Sana’a. Usually, the friends and relatives of the victims raised money to help migrants access medical care.

Human Rights Watch estimates that since the start of its investigations in January 2023, at least hundreds of largely Ethiopian migrants have been killed at the border with Saudi Arabia.

There has been no international mechanism mandated to monitor rights violations in Yemen, including abuses against migrants, since the United Nations Human Rights Council-mandated Group of Eminent Experts, was disbanded in 2021 following pressure on Council member states from Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Yemeni, regional, and international civil society groups, including Human Rights Watch, continue to call on UN member states to fill this gap with a mechanism aimed at monitoring the human rights situation in Yemen, and investigating abuses with a view to laying the foundation for accountability and redress.

Negotiations for a new truce in Yemen present an opportunity to incorporate much-needed accountability and redress measures essential for addressing the harms committed against Yemenis, as well as Ethiopian migrants in the country and others. It is critical that discussions meaningfully include all stakeholders, including Yemeni civil society. To date, talks between the warring parties, particularly those between Saudi Arabia and the Houthi armed group, continue to be conducted largely in secret without the participation of Yemeni civil society actors.

While this report is focused on the widespread and systematic abuses committed by Saudi border guards, Human Rights Watch notes that the Houthis play a significant role in perpetrating abuses against migrants along this migration route. Houthi forces’ role in coordinating security and facilitating access to the border for smugglers and migrants in Saada governorate, coupled with its practice of detaining and extorting migrants, amount to torture, arbitrary detention, and trafficking in persons.

In recent years, Saudi Arabia has invested heavily in deflecting attention from its abysmal human rights record at home and abroad, spending billions of dollars to host major entertainment, cultural, and sporting events. These include a Formula 1 motorsport Grand Prix and heavy weight boxing world title fights, purchasing Newcastle United, an English Premier League Football team, and creating the LIV golf tour, which recently announced a merger with the PGA Tour. It has also spent hundreds of millions of dollars on signing global soccer stars for the Saudi Professional League in 2023 such as Cristiano Ronaldo, Karim Benzema, and Sadio Mané.

Recommendations

Saudi Arabia should immediately and urgently revoke any policy, whether explicit or de facto, to deliberately use lethal force on migrants and asylum seekers, including targeting them with explosive weapons and close-range attacks and should urgently investigate and appropriately discipline or prosecute security personnel responsible for abuses, including unlawful killings, wounding and torture at the Yemen border.

Concerned governments should publicly call for Saudi Arabia to end any policy, whether explicit or in effect, to target migrants with explosive weapons and close-range attacks on the border with Yemen and press for accountability for any senior Saudi officials credibly implicated in ongoing mass killings of migrants and asylum seekers. In the interim concerned governments should impose sanctions on Saudi and Houthi officials credibly implicated in ongoing violations at the border, including through facilitating smugglers’ access to the border, as well as through detaining and extorting migrants.

Given the gravity of the abuses outlined in this report, a UN-backed investigation should be established into the killings and abuses against migrants and asylum seekers at the Yemen-Saudi border, including those documented in this report.

Human Rights Watch calls on organizers and participants in major international events sponsored by the Saudi government to speak out publicly on rights issues or, when whitewashing Saudi Arabia’s human rights record is the primary purpose, not to participate.

For many years, Saudi Arabia has been one of the world’s largest arms importers. Concerned governments should suspend any transfers of arms and other military equipment to Saudi Arabia, including arms, training, and maintenance agreements and suspend any ongoing military training and cooperation with Saudi border guard units.

Glossary

Asylum seeker: An asylum seeker is a person who hopes to gain refuge in another country. If a refugee arrives in a country and formally seeks asylum – the right to stay in the country to avoid being sent back to danger in their homeland – that person remains an asylum seeker pending a decision on their case.

Crimes Against Humanity: Crimes against humanity are certain crimes (for example murder, torture, deportation, or apartheid) committed by members of government forces or a non-state armed group that are knowingly committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack on a specific civilian population. Widespread could mean many attacks or one major attack. Systematic means the attack was well planned by those who carried it out.

Excessive Use of Force: Excessive use of force occurs when authorities use more force than is reasonably necessary.

Extrajudicial Killing: An extrajudicial killing is the deliberate killing of a person by governmental authorities or their agents without a trial or other legal basis – that is, outside the protections of the law.

Geolocation: Connecting a piece of visual information to the location where it was originally recorded using visual cues in the image(s). This can include, for example, identifying unique landmarks in a photograph or video with their precise location on a satellite image.

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights: The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) is a multilateral treaty that binds states parties to respect the civil and political rights of individuals, including the right to life, the prohibition of torture, freedom from arbitrary detention, freedom of religion, freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, electoral rights, and rights to due process and a fair trial.

Migrant: A migrant is a person who is moving, either on foot or by other means of transportation, from his or her home country to a secondary country, sometimes passing through one or more countries before reaching the final destination. Reasons for migration can include, but are not limited to, economic reasons, poverty, lawlessness, and environmental disaster. A migrant can be someone who is planning to seek asylum in his or her final destination country.

Pushbacks: Pushbacks are collective expulsions, which prevent people from reaching, entering, or remaining in a particular territory and usually afford summary or no screening for asylum or other protection needs. Pushbacks violate the right to due process in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the customary international law principle of non-refoulement.

Refugee: Generally, a refugee is a person who has been forced to flee their country because of persecution, war, or violence. Under the 1951 Refugee Convention, a refugee is someone who is unable or unwilling to return to their home country because of a well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, or political opinion. Under customary international law, governments are prohibited from forcibly returning refugees to their home country if it would place them in danger.

Smuggling: In this report, smuggling is defined as the illegal transportation of people across an international border, in violation of applicable laws or other regulations, in exchange for financial or other material benefit. There are three fundamental differences between smuggling and trafficking as highlighted below. Consent: The smuggled person agrees to being moved from one place to another. Trafficking victims, on the other hand, have either not agreed to be moved or, if they have, have been deceived by false promises into agreeing, only to then face exploitation. Exploitation: Smuggling ends at the chosen destination where the smuggler and the smuggled person part ways. In contrast, traffickers exploit their victim at the final destination and/or during the journey. Transnationality: Smuggling always involves crossing international borders whereas trafficking occurs regardless of whether victims are taken to another country or moved within a country’s borders.

Trafficking: The United Nations Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children (Trafficking Protocol) defines trafficking as the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring, or receipt of persons through “the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion…or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control of another person, for the purpose of exploitation.”

Methodology

This report is based on interviews with 38 Ethiopian migrants and asylum seekers who tried to cross the Yemen-Saudi border between March 2022 and June 2023, and four relatives or friends of Ethiopian migrants and asylum seekers who tried to cross during the same period. Human Rights Watch also analyzed over 350 videos and photographs posted to social media or gathered from other sources filmed between May 12, 2021 and July 18, 2023, and several hundred square kilometers of satellite imagery. Thirty-two interviewees are male, ten are female, and three are children. All 42 interviews were conducted between January and June 2023.

Human Rights Watch interviewed Ethiopian migrants and asylum seekers in Yemen by telephone. Most interviewees were located in Saada or Sana’a governorates in Yemen.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed humanitarian actors, nongovernmental organizations, and members of civil society in Yemen.

Interviews were conducted in private settings – either completely alone or with the interviewees’ family members present – with assurances of confidentiality. The researcher informed all interviewees about the purpose and voluntary nature of the interviews, and the ways in which Human Rights Watch would use the information. All were told they could decline to answer questions or could end the interview at any time. The researcher told interview subjects they would receive no payment, service, or other personal benefit for the interviews. The researcher for this project used an Ethiopian interpreter and conducted interviews in Amharic and Oromo.

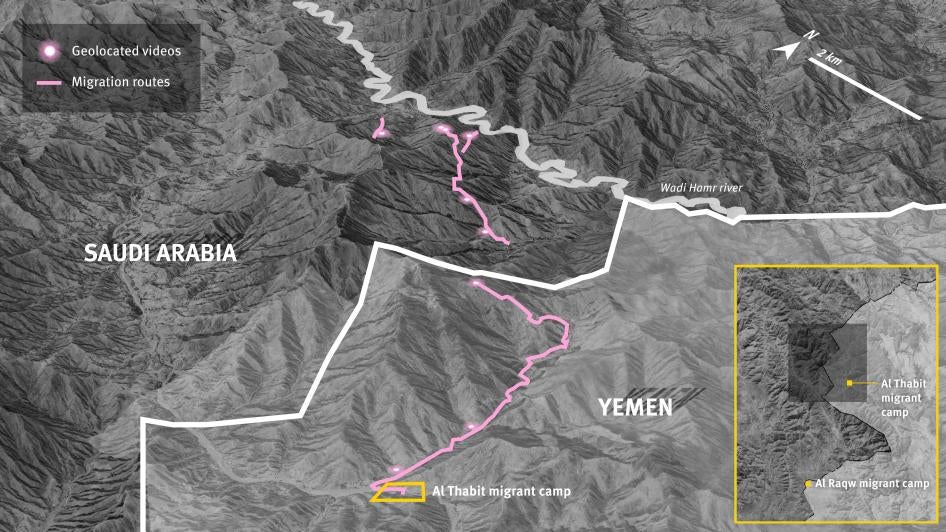

Geospatial and open-source researchers from Human Rights Watch’s Digital Investigations Lab verified the videos and photographs recorded by migrants and border residents that were shared directly with Human Rights Watch and on others’ social media. Human Rights Watch cross referenced 29 of these videos with satellite imagery to map sections of a route used to cross the Yemen-Saudi border. We identified likely Saudi border guard posts near this route which may be responsible for firing at migrants. We verified two videos showing at least three dead or severely wounded migrants inside Saudi territory.

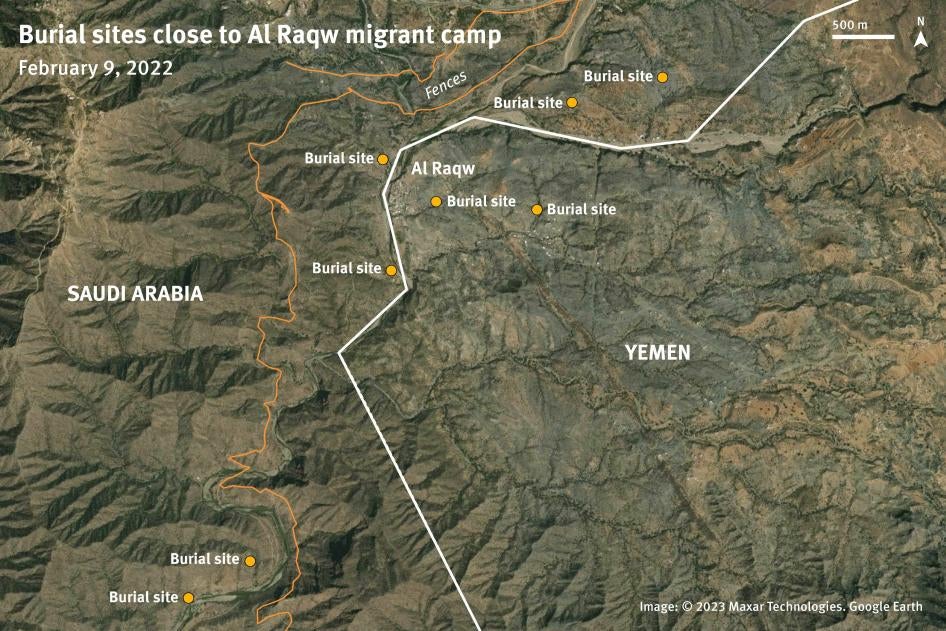

The several hundred square kilometers of satellite images Human Rights Watch analyzed were collected between February 2022 and June 2023. This included over 50 kilometers of the border between Al Raqw camp and Al Gar village, allowing us to assess the development of security infrastructure there, and identify burial sites near migrant camps which have grown considerably since the start of 2022.

Members of the Independent Forensic Expert Group (IFEG), an international group of 42 distinguished forensic experts coordinated by the International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims (IRCT), used 22 videos and photographs collected from social media by or sent directly to Human Rights Watch showing injured or dead migrants to interpret potential causes of wounds.

To protect confidentiality, pseudonyms are used for all interviewees.

Human Rights Watch wrote to the Saudi Arabian Ministry of Interior, Ministry of Defense, and the Human Rights Commission, as well as the Human Rights Ministry of Ansar Allah.

The Houthi authorities replied to our letter on August 19, 2023.

A Dangerous Journey to the Border

A combination of factors, including poverty, drought, conflict, and serious human rights abuses have driven hundreds of thousands of Ethiopians to leave their country and migrate over the past decade. An International Organization for Migration (IOM) report from 2020 found that migration from Ethiopia to Saudi Arabia is highly gendered. Women and girls account for most documented movements, given the high demand for domestic work in Saudi Arabia, while men comprised the majority of undocumented movements.[1] However, the report found that the proportion of women and girls travelling along this corridor has increased in recent years.

Most Ethiopians have traveled by boat across the Gulf of Aden and then by land through Yemen to Saudi Arabia, the final destination country. This dangerous migration route is known as the “Eastern Route” or sometimes the “Yemeni Route.” Human Rights Watch has previously documented how a network of smugglers, traffickers, and authorities in Yemen kidnap, detain, and beat Ethiopian migrants and extort them or their families for money.[2] Migrants who illegally cross into Saudi Arabia usually do so in the mountainous border area separating Yemen’s Saada governorate and Saudi Arabia’s Jizan province. There is evidence that both sides of this border have experienced landmine use and could still have mined areas.[3] IOM’s Displacement Tracking Matrix – which monitors migrant arrivals in Yemen – reported just over 73,000 migrant arrivals in 2022,[4] while in 2023, as of July 31, the figure was already over 86,630.[5] In 2022, the IOM’s Displacement Tracking Matrix found that women and girls made up 24 percent of total migrant arrivals in Yemen and 11 percent were children.[6]

Generally, interviewees said smugglers did not make in-person contact with them inside Ethiopia and directed all travel remotely through telephone calls until migrants reached Djibouti.[7] In a small number of cases, migrants went to known smuggler hotspots to meet with smugglers. Hamdiya, a 14-year-old girl from Hararghe in Oromia who said she left Ethiopia because of financial problems, explained how she contacted smugglers:

We went to Dire Dawa [a federally administered city in eastern Ethiopia near the Oromia and Somali regional borders] and hung around the gate where the smugglers could see we were poor from our clothes. They came to us and asked if we wanted to go to Saudi Arabia… They took us by car to Djibouti.[8]

Interviewees mostly used smugglers to travel all the way from their home in Ethiopia to the northern border of Yemen. Migrants generally paid for their journey in parts: 1) from Ethiopia to Djibouti, 2) from Djibouti to Aden by boat across the Gulf of Aden, 3) from Aden to Saada, and 4) from a migrant camp in Saada governorate to the border. Some interviewees had difficulty affording the whole journey with smuggler assistance and made parts of the journey – particularly once in Yemen – on their own.

Those interviewed described life-threatening journeys[9] as long as three days from Djibouti across the Gulf of Aden to reach Yemen, in most cases in overcrowded boats, with no food or water. Several interviewees described ill-treatment and abuse such as beatings by smugglers or traffickers all the way along the migration route. Many interviewees said the traffickers physically assaulted them to extort payments from family members or contacts in Ethiopia or Saudi Arabia along various points of the route. Yemane, a young man who fled his home in Raya in southern Tigray because of the armed conflict in northern Ethiopia,[10] described how upon his arrival in Yemen traffickers took him to a house and beat him, and held him for ransom:

The smugglers register you, when you cross the sea, you are always assigned to a smuggler. In Ethiopia when you communicate [by telephone] with the smuggler, they give you a code and in Yemen you give the code over [to the Yemeni smuggler]. They ask you, “Who is your owner?” They [the Yemeni smugglers] picked me up by car and took me to somewhere around Aden. There was a house, and I was put inside it. There was torture in that house. They started to beat me. I immediately called my family in Saudi Arabia, and they transferred money for me. I left [that house] after four days.[11]

Yemane eventually made his way with the assistance of smugglers to Al Raqw camp in Saada.

A 14-year-old girl, Hamdiya, said that Ethiopian smugglers in Djibouti demanded money from her before the boat crossing:

In Djibouti the smugglers asked us to pay money for the boat by sea. I didn’t have any money – I had left home with the hope of earning money. But they [the smugglers] asked me to pay 2,000 Ethiopian Birr [US$37] and they kept me [in Djibouti] for a week and they beat me every day and did not give me any food. They [the smugglers] said if you don’t pay [us] they would keep beating me. On day eight they knew I couldn’t pay so they released me.[12]

Human Rights Watch interviewed two girls and eight women for this report. Several female interviewees said smugglers and other migrants sexually assaulted them or other female migrants along the smuggling route. Three of the ten women and girls interviewed for this report were raped by either smugglers or other migrants; two became pregnant as a result. Dahabo, a 20-year-old woman from Oromia in Ethiopia who left her home in search of better work opportunities in Saudi Arabia, described her anguish, “I am pregnant from rape by a smuggler. I am in a mental crisis because of that.”[13]

Baati, a 25-year-old man from Hararghe told Human Rights Watch, “The smugglers took a ransom from us and beat us and called our family [demanding money]. They would take women outside separately, doing whatever they wanted with them.”[14]

Migrant Camps near the Border between Yemen and Saudi Arabia

Migrants told Human Rights Watch that they traveled to two main migrant “camps” along the Yemen-Saudi border in Saada governorate in northern Yemen.[15] Saada has long been a center for migrant arrivals trying to access Saudi Arabia.[16] Migrants said that in general smugglers took Oromo migrants to an area called Al Thabit in the northwest of Yemen and Tigrayan and other ethnicities of the Ethiopian migrants were generally taken to Al Raqw. Even when smugglers did not take migrants on their journey to the border, migrants usually chose to go to migrant camps according to this ethnic split. Interviewees explained that the camps were divided in this way for language purposes.

Al Thabit Migrant Camp

Al Thabit is located about 70 kilometers northwest of Saada and about 4 kilometers east of the Yemen-Saudi border on a riverbed (wadi) prone to flash floods. Satellite imagery shows that the camp started to grow from the end of June 2022, and increased rapidly from July 2022 to March 2023, until it was largely dismantled in early April 2023.

Interviewees who stayed in Al Thabit described it as a crowded makeshift informal settlement filled with tents and rudimentary shelters and surrounded by wire mesh.[17] Hamza, a 19-year-old man from West Hararghe in Oromia in Ethiopia, described the place as being “like an open-air detention center”:

There are some shelters made from plastic sheets…[It] has a compound which is built with wire, you cannot get out.…. There are hundreds of thousands of migrants there. Once you get in you cannot get out. There are guards there, the Houthis guard that area. The Houthis register everyone [that enters]. There is always registration going on. Once you submit a payment to the guards, the smugglers come and take you to the border. Otherwise, you can’t get out of Al Thabit. Sometimes you can go back into Yemen, but you cannot go alone to the border…[18]

Tayya, a 26-year-old man from Hararghe in Oromia, said he fled drought in the summer of 2022 to seek a better life in Saudi Arabia. He confirmed the Houthi presence in Al Thabit and explained how they worked with smugglers to enforce control over the area:

To get into Al Thabit you pay the smugglers. Once you are inside [Al Thabit] you can’t leave. The Houthis have a list of names saying who paid and who didn’t pay. There are Houthi forces everywhere and they work with the smugglers.[19]

Lencho, a 26-year-old man from Arsi in Oromia who tried to cross the border from Al Thabit, said that Houthi forces often took migrants from the camps to what they called “detention centers” in Saada if they could not afford to pay the smuggler fees. Migrants identified the Houthi forces by the green military uniforms they were wearing and the weapons they carried. Lencho described their abusive treatment and confirmed they hold a list of migrants that have paid smuggler fees.

I was in Al Thabit at the time and they [the Houthi forces] took me seven months ago [September 2022] to the largest detention center in Saada and kept me there for three months… I couldn’t pay money so they took me there. In Al Thabit there are so many Houthi forces. They say they are protecting the country, but they are exploiting migrants and they take money from us.[20]

Human Rights Watch received and geolocated a photograph and a video from a Houthi-run center in the southwest outskirts of Saada depicting scores of migrant men and boys in a cramped room sleeping and sitting on blankets. A video recorded outside the north side of the main building shows a migrant man with two open wounds on the left side of his lower back and buttock which are consistent with gunshot or explosive fragment wounds, according to an IFEG pathologist.

Human Rights Watch verified 16 videos shared on social media, including a Facebook livestream, showing a large group of migrants leaving the camp and moving through a pass to the north on April 4, 2023.

Al Raqw

The Al Raqw camp is located 17 kilometers south of Al Thabit camp, just east of the Yemen-Saudi border on the elevated bank of a riverbed that marks the border.

Migrants described Al Raqw as a village-like area where thousands of migrants stay in tents as they prepare to cross the border. Berhe, an 18-year-old youth from Raya in southern Tigray who escaped the conflict there in November 2022, described Al Raqw:

There are no fewer than 50,000 people living there. The biggest number [of people] is migrants…The migrants sleep in tents… There are smugglers and Yemeni people too who work there and depend on migrants.[21]

Interviewees told Human Rights Watch that before entering Al Raqw, smugglers took them to Monabbih district in Saada first. Haben, a 29-year-old man from Tigray, described the process in Monabbih:

In order to go to Raqw you have to pay at Monabbih...There is a detention center in Monabbih where migrants who cannot pay are kept in detention. The Houthis control the security [of the detention facility]. They wear the Houthi, ranger uniform. The Houthis work with the smugglers.[22]

Human Rights Watch analyzed nine photographs taken in late May and early June 2023 sent from a facility in Monabbih that third parties confirmed is used by smugglers to hold migrants before traveling to Al Raqw. The photographs show tens of migrants packed together near bright orange tents inside a fenced off compound. Using these photographs and satellite imagery, Human Rights Watch identified a facility in Monabbih 13.8 kilometers southeast of Al Raqw which matches the description of the “detention center” provided by Haben.

Satellite images of the camp show an increase in the number of tents at the compound from May 2022 to June 2023.

Merhawi, a 26-year-old man from Tigray, described how the migrant camp in Al Raqw has also become increasingly crowded in 2023:

Raqw is so overcrowded because the border is so lethal. People stay in Raqw instead [of crossing]. Just a small number now try to cross but still thousands arrive every day. Due to that there is no work in Raqw. The only way you can survive is if you have money in your pocket.[23]

Satellite imagery demonstrates the large increase in the number of tents in and around Al Raqw from June 2022 to June 2023.

Dynamics of Border Crossings

Migrants cross into Saudi Arabia from Yemen at various points along a 100-kilometers-long mountainous stretch of the border; their routes depend on the migrant camp of departure. Saudi Arabia has deployed border guards along this mountainous route for a number of years.[24]

From Al Thabit: Interviewees told Human Rights Watch that journeys from Al Thabit to the border took between five and seven hours to several days. By geolocating 29 videos shared on social media using satellite imagery and the mountains visible in the background of the videos, Human Rights Watch reconstructed the route from Al Thabit camp to the border and the first kilometers inside the Saudi territory. The route runs for 10 to 15 kilometers until reaching the border and includes steep slopes, ravines, and mountain passes as high as 2,200 meters. People leaving Al Thabit said they generally did so in large groups of between 50 and 300 migrants.

Migrants and asylum seekers who traveled in large groups told Human Rights Watch that their group had more women than men and a number of unaccompanied children. Iftu, a 20-year-old woman from Hararghe in Oromia, left Ethiopia when smugglers convinced her to travel to Saudi Arabia with the promise of better work opportunities. “Most of the group was female,” she said of her border crossing in November 2022. “I was in a group of 250 and 200 were women and 50 were men. There were a lot of kids between 12 and 13 years old.”[25]

Human Rights Watch verified 10 videos shared on TikTok and Facebook between March 6 and April 10, 2023 of Ethiopian migrants crossing from Yemen to Saudi Arabia. The number of migrants in the groups shown in these videos ranges from 22 to roughly 100. Human Rights Watch identified one and a half times more women than men in videos that contained enough detail to determine the presenting genders of the migrants. The ratio of female to male migrants on the trail increased in videos shared on social media after July 30, 2022 to five times more women than men. The ten videos verified by Human Rights Watch were short, averaging just 79 seconds, and likely did not capture the full number of migrants present in each group.

Iftu said that the journey from Al Thabit took five days as her group tried to avoid being seen by the Saudi border guards that patrol the area. “We walked for five days because we were trying to hide from the border guards,” she said. “We were changing our way [to avoid them].”[26]

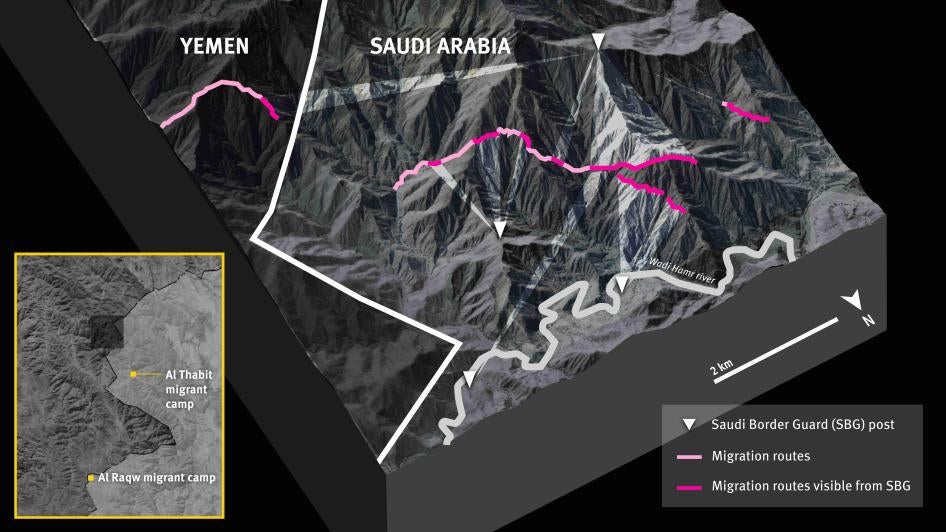

From Al Raqw: Al Raqw’s informal migrant camp settlement is right on the border. Only a river separates it from the Saudi border. Many interviewees said they could see the border crossing, border guard posts and border surveillance equipment they described as “large cameras” from the settlement itself.[27] Human Rights Watch verified 13 videos recorded in or near Al Raqw and shared on social media showing three Saudi border guard posts that overlook the camp from the top of nearby hills. Three of these videos shared on TikTok on March 6, 2023, and April 28, 2023, show newly constructed fences next to one of the border guard posts.

Satellite imagery shows that these fences, spanning 2.7 kilometers, were built in the period between July and December 2022. They appear to be under construction, likely for expansion, and run parallel to other fences which were built prior to 2022. Multiple pick-up trucks are consistently visible on satellite images along the patrol roads and parked at the guard posts. One pick-up truck with an object mounted in the back is regularly parked on a high point where the new fences end. The back of this truck faces the Yemeni border. Human Rights Watch has not been able to determine the purpose and function of the object mounted in the back.

People said that it took 20 to 30 minutes to reach the border from Al Raqw, depending on the size of their group. While four interviewees joined large group crossings from Al Raqw, most crossed from Al Raqw on their own or in small groups of fewer than ten. This is likely due to the proximity of the border to Al Raqw and less need for smuggler guidance.

Killings of Migrants

The scale of the killings of migrants at the border documented in this report far surpasses those documented previously by Human Rights Watch. Saudi Arabia’s abuses against migrants and asylum seekers, committed historically and detailed more recently in this report, have been perpetrated with absolute impunity. In a 2014 report, Human Rights Watch documented how “Saudi border guards would fire warning shots at migrants and on occasion have fired at them directly, injuring or killing them.”[28] A similar pattern was documented in a 2019 report.[29] In 2020, Human Rights Watch showed how Houthi forces in April 2020 forcibly expelled thousands of Ethiopian migrants from northern Yemen using Covid-19 as a pretext, killing dozens and forcing them to the Saudi border.[30] Saudi border guards then fired on the fleeing migrants, killing dozens more, while hundreds of survivors escaped to a mountainous border area. Saudi officials eventually allowed hundreds to enter the country, but then arbitrarily detained them in unsanitary and abusive facilities without the ability to legally challenge their detention or eventual deportation to Ethiopia.

Between January 1 and April 30, 2022, UN experts reported receiving allegations of “artillery shelling and small arms fire allegedly by Saudi security forces causing the deaths of up to 430 and injuring 650 migrants, including refugees and asylum seekers.”[31] They went on to state that this “appears to be a systematic pattern of large-scale indiscriminate cross-border killings.”

In June 2023, the International Organization for Migration’s Missing Migrant Project stated that in 2022 “at least 795 people, believed to be mostly Ethiopians, lost their lives on the route between Yemen and Saudi Arabia, predominantly in Yemen's Saada governorate at the northern border.”[32]

The marked change in pattern of abuses documented at the border from an apparent practice of occasional shootings and mass detentions to widespread and systematic killings documented by UN Experts in 2022 and in this report indicates that the abuses may qualify as crimes against humanity, if there is now a Saudi state policy of murder of civilian migrants.

Killing Migrants with Explosive Weapons

Migrants traveling in groups of all sizes who crossed the border from Yemen into Saudi Arabia described attacks they believed to be by Saudi border guards that were consistent with the use of mortar projectiles and other explosive weapons. Human Rights Watch has confirmed the use of explosive weapons in some of these cases by corroborating witness evidence with pathological analysis of photographic evidence from interviewees showing wounds consistent with blast trauma.

People traveling in groups, from four to five people up to several hundred described being attacked by mortar projectiles and other explosive weapons by Saudi border guards once they had crossed the border from Yemen into Saudi Arabia. After leaving camps near the border, migrants would approach or cross the border, often making multiple attempts over a period of months after being “pushed back” by Saudi border guards. Interviewees described seeing Saudi border guards, border guard posts and surveillance cameras and attempting to evade detection, for example by crossing during morning prayers.

Human Rights Watch has identified what appear to be border guard posts from satellite images that are consistent with these accounts. Interviewees had encountered Houthi forces in and travelling to the camps, but uniformly described being attacked by Saudi border guards as they crossed or neared the border, often describing their uniforms and frequently referring to explosive weapons “like a bomb,” mortar or rocket launcher being fired from the “back of cars.” Attacks sometimes lasted for hours or even days. Once the attacks stopped, survivors were often then approached by Saudi border guards and detained, sometimes for months, by Saudi authorities in Saudi detention facilities. Saudi border guards even told survivors they detained that they know migrants are coming and showed them vantage points “to show how they were killing people.”

All interviewees described scenes of horror: women, men, and children strewn across the mountainous landscape severely injured, dismembered, or already dead. Eleven videos and photographs of injuries and wounds sent directly to Human Rights Watch or collected from social media and assessed by an IFEG pathologist are consistent with injuries from shrapnel and explosive blasts.[33] Human Rights Watch has documented at least 11 incidents where interviewees estimated that at least 70 people had been killed, including eight where they were part of groups of at least 140 people and knew of only a handful of survivors.

“I saw people killed in a way I have never imagined,” said Hamdiya, a 14-year-old girl who crossed the border in a group of 60 in February 2023 that was repeatedly fired upon. “I saw 30 killed people on the spot.”

After witnessing the mass killing, Hamdiya pushed herself under a rock and at one point fell asleep. “I don’t know what happened after that,” she said. “I could feel people sleeping around me. I realized what I thought were people sleeping around me were actually dead bodies. I woke up and I was alone.”[34]

After surviving the attack, other migrants and Yemenis assisted Hamdiya to get to Sana’a. She told Human Rights Watch that while she did not sustain any physical injury, “I have a mental injury. I can’t sleep now. During the night I am so scared. I prefer people to stay awake and talk to me.”[35]

In total, 27 interviewees in separate incidents described 28 explosive weapons attacks from the Saudi Arabian side of the border after they crossed into Saudi Arabian territory. 24 of these incidents involved large group crossings, while four groups of smaller than ten people also experienced explosive weapons attacks. Often people couldn’t accurately name the weapon that had been fired at them. Interviewees used words like “bomb,” “mortar,” and “explosive” interchangeably when describing the explosive weapon. Some interviewees said they saw rocket launchers mounted on top of vehicles that were used to fire explosive weapons at them.

A Note on Saudi Border GuardsThe General Directorate of the Border Guard (GDBG) falls under the Saudi Arabian Ministry of Interior. The GDBG, headquartered in Riyadh, has nine commands or regions: Tabuk, Al Jouf, Northern Region, Eastern Region, Najran, Jizan, Asir, Makkah and Madinah. It is possible other security forces, in addition to Saudi border guards, were also deployed at the border at the time of the attacks documented in this report. A 2020 Carnegie Endowment for International Peace publication said that a new security force under the Ministry of Interior, the al-Afwaj Regiment, had been “tasked with preventing smuggling, trafficking, and infiltrators,” and had been deployed to support the GDBG.[36] In May 2018, the New York Times reported that a Green Beret team of the US Special Forces arrived in Saudi Arabia to train Saudi ground troops responsible for securing the border against Houthi attacks.[37] Based on witness accounts, it has not been possible to identify the exact security force units involved in attacks against Ethiopian migrants at the border with Yemen. In the absence of specific information on specialized units, this report will refer to Saudi security forces at the border as Saudi border guards. |

Crossings from Al Thabit

Interviewees explained that the journey from the Al Thabit camp takes five to seven days. Human Rights Watch verified and geolocated 29 videos that show a migrant trail from the camp, heading north towards the Saudi border before crossing into Saudi territory.

Using satellite imagery, Human Rights Watch identified three Saudi border guard posts located just beyond the border at between 3.5 and 6 kilometers west of Al Thabit. The three posts straddle the riverbed, one to the north and two to the southwest. Human Rights Watch identified an additional four buildings located over a 4.1-kilometer stretch of ridgeline in Saudi territory that runs roughly parallel to the trail migrants use to cross from Al Thabit. The buildings are located along fences and what appear to be patrol roads, indicating they are likely Saudi border guard posts. A further three buildings that appear to be Saudi border guard posts are located closer to the valley floor of Wadi Hamr river between 1.3 to 3.1 kilometers north of the trail from Al Thabit.

Human Rights Watch identified what appears to be a Mine-Resistant Ambush Protected (MRAP) vehicle parked at one of the Saudi border guard posts north of the trail from Al Thabit in satellite imagery from October 11, 2021 to January 1, 2023. An MRAP is a light tactical vehicle that has armor and is designed and engineered to protect it against mines, improvised explosive devices, or small arms fire. The MRAP visibly parked at the Saudi border guard post appears to have a heavy machine gun mounted in a turret on its roof. Human Rights Watch was not able to identify the make or model of the MRAP.

Using a 3D model of the area near Al Thabit, Human Rights Watch identified large sections of the migration route that are visible from four of the likely Saudi border guard posts. This includes the majority of the route Human Rights Watch reconstructed inside Saudi territory.

Consistent with interviewees’ evidence, 10 videos verified and geolocated by Human Rights Watch show migrants in large groups strung out over tens to hundreds of meters along the trail, with large proportions of women, often in brightly colored clothing, and with no visible weapons. Four of these videos shared on TikTok between November 26 and December 4, 2022 show a group of at least 47 migrants in a line approximately 70 meters long passing near the line of sight of what appears to be a Saudi Border Guard post in Saudi territory.

Interviewees consistently stated that that they were in Saudi territory while coming under fire. They did not report a clearly marked border, but they recounted seeing buildings on hilltops which they thought were border guard posts, surveillance cameras and being told by smugglers that they were in Saudi territory, with migrants with debts to smugglers being made to walk first, used as “cannon-fodder.” Interviewees consistently reported both seeing Saudi border guards and trying to evade being seen by them. They frequently referred to seeing Saudi border guards with “cars” with mortars or other explosive weapons on the back. At least nine interviewees reported being approached and detained by Saudi border guards after the firing stopped.

Dahabo, a 20-year-old woman who left her home in Gara Muleta, Oromia in Ethiopia in search of better economic opportunities in Saudi Arabia, described crossing the Yemen-Saudi border in December 2022:

Immediately after we arrived [at the border], they [the Saudi border guards] fired on us…A lot of people were dying. In a group of 200 migrants only 50 people survived.

The people who shot us were Saudi government military – the uniform was multiple colors. It was like green or white or something. Everyone knows it is Saudi military – the smugglers told us – they are Saudi military, they are border guards. Everyone was calling the people who shot at us Saudi military. I couldn’t see the military, the people firing at us. It wasn’t a bullet they were shooting. It was thrown from the back of a car, like a bomb. It kills a lot of people. They fired on a lot of people.[38]

Dahabo said she was then captured by Saudi border guards who told her, “We know you are coming this way.”[39] After four nights she said the Saudi border guards released her and told her, “Don’t ever look back and if you look back, we will kill you.”[40]

Iftu attempted to cross into Saudi Arabia one month earlier, in November 2022:

We walked five days because we were trying to hide from the police [border] guards. We were changing our way [to avoid them]. There was firing from the border guards. They were firing big rocket launchers at us. It was like a bomb. From the 250 people [in the group crossing], 150 died. There were 70 or 80 people who were severely injured and scattered all over the mountain.[41]

Iftu explained how she was able to approximate the number of dead migrants from her group. She explained that after the firing from the explosive weapons ended, Saudi border guards came to her, “showed me the dead,” and collected the remaining survivors together. She added that “after they captured us, they took us to the top of the mountain to show how they were killing people.”[42] She was then taken to a detention center “approximately six hours away from the border” and where she was held for about six weeks. Saudi officials eventually released her and took her back to the border where she was able to cross back into Yemen.[43]

Hadiya, a 20-year-old woman from East Hararghe in Ethiopia, tried repeated crossings from the Al Thabit encampment:

We were there for three months, because we were trying to cross all this time. We would try and cross and then the border guards would push us back and then we would try and again and we would be pushed back, and this happened for 3 months.[44]

Hadiya’s last attempt was in October 2022, she explained the lethal force used by Saudi border guards:

I was with 170 people. Most of them were women, and there were kids also. The Saudi [border guards] were firing at us from the back of a car. I saw them throwing something from a car… When they [the Saudi border guards] fired at us people lost their hands and legs and we couldn’t help them because we had to help ourselves. I saw people killed with my own eyes. I saw 20 people dead while I was walking.[45]

In another case, Hanna, a 20-year-old woman from West Hararghe in Ethiopia explained how she recognized the border guards:

I saw the border guards’ car – it was similar to the color of the border guards uniform color. The color is similar to a grass color – green and white. The car is a small car – it looks like a gun that is on the car. We see from far they are pointing it at us and it looks like a gun. We don’t clearly see people but we see cars – I saw more than 30 cars all over the mountains. Early in the morning they [the border guards] started to fire on us…people started to die…people were screaming – the border guard kept firing at us for 2 hours.[46]

In both cases, after the firing stopped, Hadiya and Hanna were approached and detained by Saudi border guards.

Desta, a 25-year-old man from West Hararghe, said he left Ethiopia because he “couldn’t survive” the poverty. He said that he tried to cross the border three times, the last attempt in January 2023 in a group of about 200 people. His account illustrates how Saudi border guards monitor migrant crossing points from different directions from various border guard posts:

When we arrived at the border [crossing point] there were border guard posts in three directions, south, southwest, and north … We had to run uphill at this place where you have to be strong enough to get on the top of the mountain and quick enough so the southwest border guard post won’t see you.[47]

We rested in Al May because nothing was happening. The border guards couldn’t access this place we thought, but after we arrived [in Al May], those [border guards] on the south border guard post saw us and fired on us where we were resting. We started to run. We were crawling on our hands, and a lot of people died, and some escaped. But after we escaped, we had to go down [the mountain] and then that’s where there is Saudi farmland. Unfortunately, when we got to the farmland …, a Saudi tank was standing there. The tank started to fire on us and killed a lot of people, 185. Most were not killed on the spot; most were wounded… People were injured and waiting for help, but no one came to help them. Only 15 people survived.[48]

A Saudi border post is visible in a video sent to, verified and geolocated by Human Rights Watch. The video shows the bodies of at least two migrants hidden under bushes just north of the trail from Al Thabit into Saudi Arabia. The person recording says the victims were killed three days prior. The border post is visible 1.3 kilometers to the northeast of the person making the recording one second into the video, just before the bodies are exposed.

Bilal, a 25-year-old man from West Hararghe in Ethiopia, tried to cross the border in February 2023. He described the explosive weapons he saw being used against his group of 140 as “like something which is used to shoot down a plane. They fire it from the back of a car.”[49] Bilal then explained how he had been walking with his group when the Saudi border guards struck them with what he said were mortar projectiles:

We walked about eight hours [from Al Thabit] to arrive at that place [where the attack happened]. There is … a space where you take a rest. We stayed there for a few hours… As soon as we started to walk again, the border guards started to fire on us – like ten times.

They [the Saudi border guards] … were firing big things like a mortar …They fired it from the back of a car. We could see where the border guards were positioned. They were in four spots. We lost 130 people that day – the majority were women and there were children there too.[50]

Hamza, 26, from West Hararghe in Ethiopia described reaching the border and seeing a car with “a big gun in its back half a km away.” His group waited overnight after seeing 70 people in another group of 90 being killed from a nearby hilltop.

At lunch it looked clear. We could see the car, but it didn’t move. The smugglers showed us different directions where the border guards are located…where you run. At lunch time we decided, we were 160 people…We started to walk in line, the border guards fired on us… I saw people thrown on the branch of trees, people cut in two and people who lost their body parts.[51]

In one particularly chilling incident in early June 2023, interviewees said Saudi border guards fired explosive weapons on a group of resting migrants after having just released them back at the border. Munira, a 20-year-old-woman from Oromia, explained what happened:

The Saudis picked us up from the detention center in Daer and put us in a minibus going back to the Yemen border. When they released us, they created a kind of chaos; they screamed at us to “get out of the car and get away.” They trapped us into the same lane, they didn’t want us to spread out in case we tried to go back to Saudi I think, and this is when they started to fire mortars – to keep us into the mountain line, they fired the mortar from left and right. When we were one kilometer away, the border guards could see us. We were resting together after running a lot…and that’s when they fired mortars on our group. Directly at us. There were 20 in our group and only ten survived. Some of the mortars hit the rocks and then the [fragments of the] rock hit us…The weapon looks like a rocket launcher, it had six “mouths,” six holes from where they fire and it was fired from the back of a vehicle – it fires several at the same time. They fired on us like rain.

When I remember, I cry... I saw a guy calling for help, he lost both his legs. He was screaming; he was saying, “Are you leaving me here? Please don’t leave me.” We couldn’t help him because we were running for our lives. There are several people who lost their body parts.[52]

An IFEG pathologist reviewed a photograph of the injuries to Munira’s face and concluded that the wounds are consistent with characteristics of a high-speed element like fragmentation.[53] At the time she was interviewed she was receiving basic treatment in a medical center in Qatabir (a district in Saada) and explained she had no choice but to try and cross the border again as soon as she recovers: “We can’t afford life in Yemen, there is no food, and we can’t survive, we will die. Even tonight or tomorrow morning we will try to cross [the border] again.”[54]

Crossings from Al Raqw

As set out earlier in this report, the Al Raqw camp sits on the elevated bank of a river that forms the Yemen-Saudi border. As soon as migrants cross the river, they are in Saudi territory. As with Al Thabit, Human Rights Watch used satellite imagery and videos shared on social media to identify border fences along with what appear to be Saudi Border Guard posts that are set back from the river. Eight videos shared on social media between April 12, 2022 and May 4, 2023 recorded inside the camp, and verified by Human Rights Watch, show that these posts have a direct view of Al Raqw.

Amanuel, 20, from Tigray crossed into Saudi Arabia in May 2022 almost reaching the border fence before:

...we decided to travel in the morning around 9 a.m. After we walked around 30 minutes, there is a fence [on the border]. It is built with iron metal and some wire mesh. You have to cross onto that fence to go into Saudi Arabia. It is not strong, you can easily jump over. 10 meters away from that fence, the border guards threw a big explosive onto us. It was like a mortar – a very big explosive. I was hit by this.[55]

Amanuel crossed in a two-hour walk from Al Raqw into Saudi Arabia in a group of 200 Ethiopians, 40 men and 160 women of mixed ethnicities, in January 2023:

After we crossed the border, …it was midnight and we were sitting in groups of 20 to 30 people... I don’t know what happened, but the border guards fired on us… We were sitting according to our ethnicity. All the Amhara died. The Tigrayan group were sitting separately. We [the Tigrayans] were hit by the impact of the explosion. The people in the direct line of fire of the [explosive] were all killed… I was hit also but not directly.[56]

Berhe was hit on both legs. Other migrants carried him to safety. Berhe sought medical assistance in a hospital in Saada:

The wound I have is on both legs, but the right leg is worse because it is broken. They [hospital in Saada] put metal to support my leg. I couldn’t continue the treatment because I don’t have enough money. I am sleeping inside the compound hospital … under the shade of the tree as I couldn’t afford to stay inside the hospital.[57]

Said, a 25-year-old man from Raya Kobo in Amhara, tried to cross the border in March 2023 and was injured in his face and chest when Saudi border guards fired on his group:

We left Raqw at 3 a.m. and there were 200 of us in the group. Half of our group were women. They got tired and they wanted to sit and take a break…We couldn’t move for a while because it was daylight and we had to wait when the border guards are going to prayer. When we started walking, the border guards fired on us and killed 40 people. I saw these people die… three of my friends, women who were from Raya...were killed in front of me…I don’t want to think about that too much…All of my friend’s stomach came out, and the other one lost both her legs. I couldn’t bury more people because the firing was still coming.[58]

A video shared on Facebook on March 16, 2023 and verified and geolocated by Human Rights Watch shows four wounded migrants in the back of a truck at a location roughly three kilometers east of Al Raqw. An IFEG pathologist determined one of the wounded migrants sustained damage to the muscles and bones in his left leg consistent with explosives damage.[59] The truck appears to be transporting the migrants to get medical assistance.

Merhawi, 26, from Tigray, described himself as a trader that had crossed into Saudi Arabia many times. He explained “the border guards see migrants with a camera, but if they see you carrying trade they won’t kill you.”[60] Merhawi said he then traveled to the border crossing points from Al Raqw to collect the body of his deceased friend who attempted to cross into Saudi Arabia in February 2023:

They [the Saudi border guards] shot him with a bullet not with a mortar, on his leg. They shot him only on the leg, not other parts… I think he bled to death. We know how much he struggled because the place was impacted by his body a lot…. We went to collect his body. We communicated with the border guards…There were three of us that day. The guards didn’t believe us, so they kept one of us behind and let the others go and get the body. We picked the body of my friend up and arrived back in Raqw and buried him.[61]

Numbers of Migrant Deaths

Human Rights Watch has not been able to confirm the exact number of migrants killed in each incident documented during this research. Interviewees often said they estimated how many were killed by subtracting the number of people who ultimately returned to the migrant camps and villages along the border or in hospitals in Saada from the total number in the group that tried to cross the border at the outset. Human Rights Watch notes that some migrants may have returned without interviewees being aware of them doing so; some may have sought medical assistance without other survivors knowing; others may have managed to pass Saudi border guard patrols and get inside Saudi Arabia.

Interviewees who were in groups of hundreds of people have, however, consistently reported witnessing more deaths than they could count and being surrounded by bodies after coming under attack. One interviewee, Fami, a 23-year-old man from West Hararghe, Oromia, recounted how fellow migrants returned to collect bodies after his group was subjected to an explosive weapon attack at the border. Fami estimated that his group numbered 190 people when they tried to cross the border in November 2022 but that only 20 returned to Al Raqw migrant camp. “I know 90 people were killed,” he said, “because some migrants returned to that place to pick up the dead bodies. They counted around 90 dead bodies.”[62]

Jemal, a 40-year-old man from Wollo in Amhara region has lived in Yemen for 19 years. He said that he is friends with many Ethiopian migrants who try to cross the border into Saudi Arabia and he recently went to Saada to give his friend who died while crossing the border in January 2023 a decent burial. When Jemal went to the al-Juhmouri hospital morgue he saw a lot of bodies he identified as looking like local Yemeni nationals but said most looked like Ethiopians. “I cannot say how many numbers of dead there were,” he said, “but many. The bodies were piled upon each other.”[63]

Jemal sent Human Rights Watch a video showing the entrance to a container containing a pile of dead bodies at least four corpses high in the grounds of al-Juhmouri hospital. Jemal also sent another video showing an additional dead body on top of a container located in the southeast corner of the hospital.

Large Group Crossings and Deaths

Human Rights Watch interviewed 23 people who attempted to cross into Saudi Arabia as part of large groups that came under fire from explosive weapons. This included one person who watched another group come under fire the day before he attempted to cross, giving a total of 24 incidents. The dates and groups sizes indicate that these were all separate incidents. In total, 3,442 people were estimated to have taken part in these crossings. Ten interviewees estimated that from 11 attempted crossings with a total of 1,278 migrants, they had seen killed or estimated at least 655 deaths. In one of these incidents, a survivor explained that from his group of 170 people, “I know 90 people were killed, because some returned to that place to pick up the dead bodies – they counted around 90 dead bodies.”[64]

For nine additional attempted large group crossings, involving an estimated 1,630 people, interviewees saw people dying around them, but were often too busy fleeing or too traumatized to give an estimate of the number of deaths and instead said how many people returned to the camps. In these nine cases, out of 1,630 migrants, interviewees recounted that 281 people had survived. For example, one interviewee explained “from 150, only 7 people survived that day… There were remains of people everywhere, scattered everywhere.” Another interviewee went to the Saudi border to collect the body of a girl from his village and said “Her body was piled up on top of 20 bodies” explaining that “It is really impossible to count the number. It is beyond the imagination. People are going in different groups day to day. The dead bodies are there.” For the remaining four large group crossings that came under fire from heavy weapons, interviewees were not able to estimate the number of dead or known survivors.

This means Saudi border guards have killed hundreds, possibly thousands, of Ethiopian migrants and asylum seekers.

Small group crossings

While Saudi border guards fired explosive weapons at four small group crossings of 10 people or less, interviewees said they witnessed no deaths as a result.

Video analysis

Human Rights Watch analyzed two videos that show large numbers of dead migrants strewn across the mountainside. These videos, which were shared on Facebook, appear to have been recorded on the border crossing trail from Yemen to Saudi Arabia. While Human Rights Watch was not able to precisely geolocate these videos, the mountainous terrain, topography and vegetation visible in them are consistent with other videos geolocated to the border area.

The first of the two videos was uploaded to Facebook on November 5, 2022. It shows at least 13 to 20 bodies lying motionless near sparse foliage and rocks. Despite the poor quality of the video, at least two of the bodies are visibly stained with blood. According to an IFEG pathologist, one of the bodies exhibits advanced decomposition. The caption attached to the video claims it shows “Oromo children” who “died at the gate of Saudi Arabia.” The term Oromo children used in this context refers to people from the Oromia region of Ethiopia, not that the bodies are those of children. The uploader has shared multiple videos recorded near Al Thabit on his TikTok page, indicating the migrants may have died near the trail from Al Thabit into Saudi Arabia.

The second video, shared to Facebook on May 18, 2023, shows at least seven dead migrants near a trail, five of whom are female. As the people recording walk through the area, they cover the bodies with cloth and offer water to two more migrants who are limp and appear close to death while speaking Arabic and Tigrinya. At one point someone off camera refers to a migrant as “Tigrayan,” indicating the video may have been recorded near the trail from Al Raqw into Saudi Arabia. Human Rights Watch was unable to determine what killed the migrants shown in these videos.

Burial sites

Human Rights Watch identified at least eight burial sites near Al Raqw, half in Saudi territory, and counted at least 287 graves on a satellite image of June 23, 2023. Four of these sites, the closest to Al Raqw, have grown since February 9, 2022, at which date Human Rights Watch counted 183 graves.

The largest burial site identified by Human Rights Watch is located across the river from Al Raqw on Saudi territory. It grew significantly between February 2022 and June 2023. Human Rights Watch counted 12 graves on a satellite image of February 9, 2022 and 72 on an image of June 23, 2023 at this site.

Human Rights Watch verified a video shared on Facebook on May 16, 2022 showing at least five bodies covered in cloth in the riverbed next to this site. An additional video from the same event that was shared on Twitter on November 12, 2022 shows migrants digging a grave in the burial site and placing one of the bodies into it. The video shows other completed graves in the site made with stones and concrete.

A video recorded at a burial site nearby and shared on TikTok on September 5, 2021 shows a close-up of a similar headstone with a name and a date of birth and death in the Ethiopian calendar on it. Two additional videos recorded at a burial site a kilometer east of Al Raqw and shared on TikTok on December 23 and 25, 2022 show migrants digging what appear to be single body graves. Human Rights Watch cannot confirm how many bodies each grave in the eight identified burial sites holds, but these videos suggest each headstone represents the grave of an individual.

The number of new graves in the burial sites near Al Raqw is not wholly representative of the hundreds or thousands of deaths suggested by interviewees to have occurred since May 2022. Bodies of migrants who were killed while crossing the border are not always retrieved. Humanitarian actors[65] operating services for migrants in Saada also described how some migrants are buried in remote places or left unburied along the route, vulnerable to the elements or wild animals. Human Rights Watch verified two videos shared on Facebook on April 24, 2023 that illustrate this. Migrants in the videos are shown burying victims in an unmarked area on the Yemen side of the border on the trail from Al Thabit to Saudi Arabia. Two other videos shared by the same Facebook page on April 4, 2023 and analyzed by Human Rights Watch show a similar burial in a different remote location. Other bodies that are retrieved may be sent to hospitals in nearby districts and Saada city.[66]

The consistency with which interviewees described witnessing large number of deaths, the use of explosive weapons by Saudi border guards, and the pattern of excessive lethal force against unarmed civilian migrants indicate that Saudi border guards have killed hundreds if not thousands of migrants between March 2022 and June 2023. Human Rights Watch believes that the nature and scale of abuses committed by the Saudi border guards, which follow a pattern identified by UN experts and notified to the Saudi authorities in October 2022, and the similarities in the apparent unlawful killings and other crimes suggest these abuses may qualify as crimes against humanity.

Shootings at Close Range

Interviewees traveling in smaller groups or on their own said once they crossed the Yemen-Saudi border they would see Saudi border guards either at a distance or sometimes at close range carrying rifles. Some said these rifles had optics mounted on them.[67] Many said border guards shot at their groups immediately or that border guards would let the group travel further into Saudi territory, ask the migrants where they were going, and then fire their rifles at them. People also described armed border guards apprehending them, asking them which limb of their body they would prefer to have shot, and then shooting that limb. One interviewee described how Saudi border guards killed a migrant “on the spot” after he refused to rape another migrant in the group.[68]

Some people who were shot survived after fleeing from the border guards back toward Yemen. Others that were shot at, were temporarily detained by Saudi border guards, without medical care. Saudi officials took them close to Yemen, still wounded, and expelled them from Saudi Arabia. Fourteen interviewees were involved in shooting incidents at close range by Saudi border guards. Six interviewees were both targeted by explosive weapons and involved in shootings at close range.

Nuradin, a 23-year-old man from West Hararghe left his home in Ethiopia four years ago because of the economic situation and in search of a better life in Saudi Arabia. After some years spent in Redda, Yemen begging and searching for work, he tried to cross the border in December 2022:

We were confronted by Saudi border guards. They were shouting at us and commanded us to stop... We surrendered and showed them our hands. When they [the Saudi border guards] arrived near us, they shot at us. The man who shot me was only four meters away from me. I was with 45 other people, men and women; most of the group was female. There were only 12 men and there were kids there too. They shot at our legs…The guards were wearing Saudi military uniform, multiple colors with a mix of green and brown. It was obviously a Saudi military uniform. There were eight that shot at us. They were carrying a gun or a sniper rifle that had a camera on it.

I was shot in my neck and I was bleeding…I couldn’t remember too much. There were eight [border guards] when they shot at me. This I remember. After we were shot, we were collected. Many people were shot in different parts of their body. The bullet went through my mouth and out through my neck. I was shot brutally.[69]

Nuradin sent Human Rights Watch a photograph showing his injury. An IFEG pathologist reviewed the photograph and confirmed the injury sustained is consistent with characteristics of a high-speed element, including bullets.[70]

The border guards took Nuradin and four other migrants from his group to a temporary detention facility nearby. They released him five days later in an area close to Al Gar in Yemen on the border. Nuradin did not receive any medical attention while detained and the border guards told other people detained in the facility not to help him and any other wounded migrants. Nuradin said it was “a miracle I survived.” A few days after he was detained, two female detainee migrants helped him manage the bleeding and his injury.