Summary

In 2016, the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) signed a peace accord, establishing a landmark opportunity to halt the serious abuses and atrocities that had long accompanied a decades-long armed conflict.

Following a FARC ceasefire starting in mid-2015, conflict-related abuses in Colombia decreased. Homicide rates dipped to the lowest in decades, reports of forced displacement were significantly lower, and levels of a number of other abuses declined as well.

But in many areas of Colombia, hopes that the accord would bring peace were soon frustrated. One such place is Tumaco—the country’s second-largest Pacific port. In this area, close to the border with Ecuador, civilians have, for many years, endured horrific abuses at the hands of right-wing paramilitaries and their successor groups, as well as the FARC.

Before the peace accord, in 2014, Human Rights Watch documented abuses committed in Tumaco by the FARC and the Rastrojos—a group that emerged from paramilitary death squads. These included killings, disappearances, kidnappings, torture, forced displacement, and sexual violence.

Human Rights Watch returned to Tumaco in June and August of 2018 to determine how much had changed. We found that flaws in the demobilization of FARC guerrillas—and in their reincorporation into society—helped prompt the formation of FARC dissident groups. These groups have continued to engage in atrocities similar to those attributed to the FARC during the conflict. Pervasive drug trafficking has helped fuel their growth. And levels of serious abuse are again increasing in Tumaco.

Groups including “People of Order,” “United Guerrillas of the Pacific,” and the “Oliver Sinisterra Front” have battered urban neighborhoods and rural hamlets of Tumaco. They kill and disappear those who dare defy them, rape women and girls, recruit children, and force thousands to flee. Additionally, the “Gaitanist Self-Defenses of Colombia,” a group that emerged out of a flawed paramilitary demobilization in the early 2000s, engaged in serious abuses in Tumaco in 2016 and 2017 during a largely foiled attempt to take control of part of the area.

In researching this report, Human Rights Watch conducted more than 70 interviews, including with victims, their relatives, judicial authorities, prosecutors, community leaders, and residents. We consulted a wide range of other sources and documents, including victims’ testimony taken by public officials in Tumaco.

In all, we documented abuses against more than 120 victims in Tumaco since mid-2016, including 21 killings, 14 disappearances, 11 cases of rape or attempted rape, and 24 cases of recruitment or attempted recruitment, among other types of abuse. These cases represent only a fraction of the cases reported by government authorities. And many abuses go unreported, due in part to the tight social control imposed by armed groups in vulnerable neighborhoods and rural communities in Tumaco.

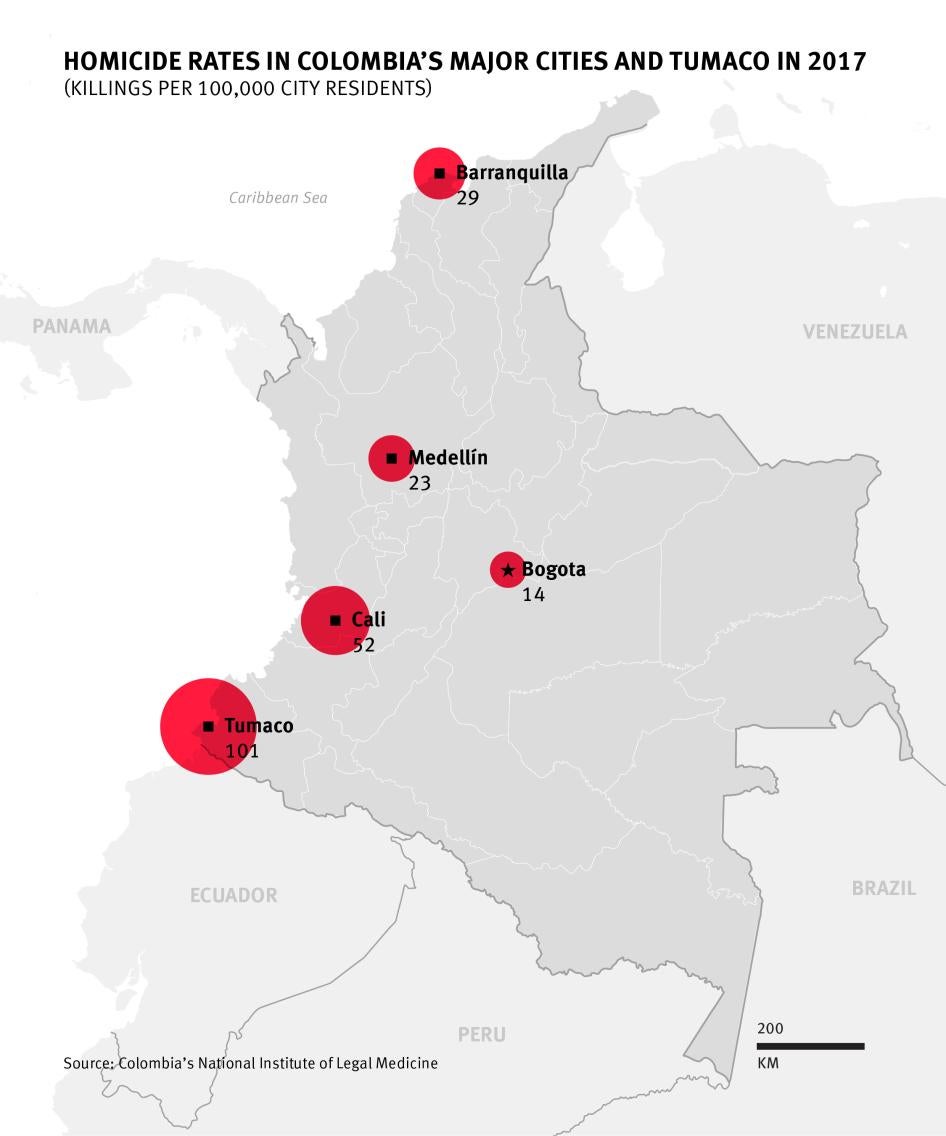

While not all recent homicides in Tumaco are due to FARC dissident groups, homicide rates there have spiked: in 2017 the rate was four times the national average and data through September show killings are up nearly 50 percent in 2018. Three prosecutors investigating these murders, as well as two human rights officials who take testimony from the relatives of victims, told Human Rights Watch they believe that FARC dissident groups have committed the majority of them. Civilians are often killed as the groups seek to terrorize or impose rule in poor urban neighborhoods and rural communities. In May 2018, for example, a 26-year-old fisherman was found dead in an estuary, his hands tied with a rope. His body was riddled with dozens of gunshot wounds. A sign on his chest read, “for thieving and snitching.”

Victims of these murders include community leaders. Since 2015, Colombia has seen a significant increase in such cases nationwide. Tumaco, with at least seven community leaders reported killed since January 2017, is among the municipalities most affected. In October 2017, for example, José Jair Cortés, a community leader who had fled a death threat, was shot and killed as he returned to visit his ailing wife in the rural area of Alto Mira y Frontera. A commander of the Oliver Sinisterra Front had, a month earlier, threatened Cortés and his colleagues who served on the local Neighborhood Action Committee.

In March 2018, the Oliver Sinisterra Front kidnapped three employees of the Ecuadorian newspaper El Comercio who were reporting on the group’s operations in Mataje, Ecuador. The group held the men hostage for two weeks, demanding that the Ecuadorian government release three imprisoned members. On April 11, the group released a pamphlet announcing that the three men had died. The Ecuadorian and Colombian governments say the Oliver Sinisterra Front murdered them. Their bodies were found in rural Tumaco in mid-June.

FARC dissident groups have also been responsible for multiple disappearances in Tumaco. Residents believe that the bodies of the disappeared are thrown into the sea, into estuaries, or into rivers.

And armed groups in Tumaco, including FARC dissident groups, are also committing rape. Nowhere else in Colombia is sexual violence by armed groups so widespread. From January 2017 through the end of September 2018, 74 people in Tumaco were victims of “crimes against sexual integrity” (including rape and other sexual crimes) related to armed conflict, according to Colombia’s Victims’ Registry. For example, Human Rights Watch documented the case of a 14-year-old girl who was raped in rural Tumaco in October 2017. Four armed men arrived at her home one night around 11 p.m. and told her parents that “the commander” had asked for the girl. They took her away, returning her the next morning with various wounds. She told her parents that several men had raped her.

FARC dissident groups have established control over residents’ movements between neighborhoods throughout urban Tumaco. When people cross an “invisible border” into neighborhoods where they are not known to the group in control—or when they enter, in particular, from an area dominated by a rival group—they may be killed, threatened, or disappeared.

The widespread abuses in Tumaco are illustrative of atrocities in other municipalities along Colombia’s Pacific Coast. Residents and members of humanitarian organizations operating in other municipalities told Human Rights Watch of similar incidents. In November 2017, the country’s Constitutional Court noted in a ruling that the situation in Tumaco “reflects the generalized violence affecting Afro-Colombian communities and indigenous people in all the Pacific region of Nariño,” the province where Tumaco is located.[1] The court concluded that the zone is suffering a “grave humanitarian crisis.”

In early 2018, the Colombian government launched a powerful military and police operation to curb abuses by armed groups, deploying thousands of security officers to Tumaco and nine neighboring municipalities in Nariño Province. The operation helped arrest scores of people but data through September 2018 shows that serious abuses in Tumaco are continuing at comparable rates or have actually increased. As noted above, Tumaco’s already high homicide rate shot up further during the first nine months of 2018.

Impunity remains the norm for abuses in Tumaco. Of the more than 300 murders committed there since 2017, only one person has been convicted. No one has been charged, let alone convicted, for any of the disappearances, child recruitment, or forced displacement. One important reason for the poor results is the insufficient number of judges, prosecutors, and investigators available to handle such cases in Tumaco.

Authorities also have failed to provide adequate assistance to victims of displacement as they flee their homes. Officials’ efforts to assist displaced people, required under Colombian law, have been poorly supported. Shelter for victims has been inadequate, and delivery of humanitarian aid has often been delayed.

Recommendations

To the Administration of President Iván Duque:

- Ensure that displaced people in Tumaco promptly receive the humanitarian aid to which they are entitled under Colombian law.

- Ensure that the national police and armed forces implement an effective strategy in Tumaco to protect local residents from armed groups.

- Increase efforts to reduce coca cultivation in Tumaco, including by implementing plans to replace coca crops with food crops.

- Work with the municipal and provincial governments to ensure that residents have adequate access to public services.

- Work with the municipal and provincial governments to ensure that survivors of sexual violence receive the aid and protection to which they are entitled under Colombian law.

- Monitor failures to implement current laws and policies related to gender-based violence in Colombia, with a particular focus on sexual violence perpetrated by armed actors.

- Ensure effective protection of community leaders in Tumaco.

- Endorse the Safe Schools Declaration.

To the Attorney General:

- Increase the number of investigators and prosecutors in Tumaco handling forced displacement, disappearances, sexual violence, child recruitment, and other serious abuses.

- Ensure protection for all investigators and prosecutors working in Tumaco.

- Continue investigations into the alleged existence of houses where FARC dissident groups torture and dismember people.

- Implement protection programs for victims of gender-based violence, so that victims who report violence receive adequate and durable protection, including in cases of sexual violence by armed actors.

- Monitor and ensure that allocated budgets are sufficient for adequate resources and staffing levels needed to address sexual violence by armed actors.

To the Magistrates’ Council:

- Increase the number of “specialized judges” assigned to try serious crimes, including aggravated murder, kidnappings, and child recruitment.

To the Mayor of Tumaco:

- Provide adequate shelter in Tumaco for displaced people and victims of sexual violence. Ensure that shelters protect victims and provide dignified living conditions.

Methodology

In researching this report, Human Rights Watch conducted more than 70 interviews with a wide range of actors. These included abuse victims, their relatives, and other residents of rural and urban areas of Tumaco, as well as community leaders, judicial authorities, prosecutors, church representatives, local human rights officials, and members of international organizations. Due to security concerns, we did not speak with members of armed groups.

The vast majority of the interviews were conducted in the municipality of Tumaco during visits in June and August 2018, though some interviews were also conducted in Pasto and Bogotá, as well as by telephone. All interviews were conducted in Spanish.

In our research, we also drew on official statistics and consulted a wide range of other sources and documents, including court rulings, official reports, testimony taken by public officials in Tumaco, publications by nongovernmental organizations, and news articles.

Many interviewees feared reprisals and spoke with us on condition that we withhold their names and other identifying information. Details about individuals, as well as interview dates and locations, have been withheld when requested or when Human Rights Watch believed the information could place someone at risk; all such details are on file with the organization.

Human Rights Watch provided transport, snacks, and water during the interviews but did not make any payments to interviewees. Where appropriate, Human Rights Watch provided contact information for organizations offering legal, social, or counseling services, or linked those organizations with survivors.

Human Rights Watch makes every effort to abide by best practice standards for ethical

research and documentation of sexual violence, including with robust informed consent procedures, measures to protect interviewees’ privacy and security, and interview techniques designed to minimize the risk of retraumatization. Interviewees were explicitly told that their participation was voluntary, and could choose not to answer particular questions and could end the interview at any time. In some cases, at the request of the interviewee or because the interviewee demonstrated signs of potential for re-traumatization, the Human Rights Watch researcher did not ask the survivor to describe details of abuses. For reasons of security and privacy, survivors are identified by pseudonyms.

Interviews with victims, their relatives, or witnesses were conducted in confidential settings. We informed all participants of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and how the information would be used. Each participant orally consented to be interviewed.

In this report, the term “disappearance” refers to cases containing the two elements of the offense of “enforced disappearance” as it is defined in Colombian criminal law and interpreted by Colombia’s Constitutional Court. The two elements are: 1) the deprivation of liberty of a person by any means, followed by hiding them and 2) a lack of information about the whereabouts of the person, or the refusal to recognize their deprivation of liberty or give information about the person’s whereabouts. Under Colombian law, anyone can be criminally liable for an “enforced disappearance,” irrespective of whether the person is a private individual, a participant in an armed conflict, a state agent, or someone acting with the support or acquiescence of state agents.

In this report, the term “FARC dissident group” is used broadly to include groups that were created or led by former FARC guerrillas after the group’s demobilization. These include fighters who either rejected the demobilization or who, after demobilizing, chose for whatever reason to be part of another armed group. (Some people in Colombia prefer to use the term “FARC dissident group” to refer only to groups that rejected the demobilization.)

All translations from the original Spanish to English are by Human Rights Watch unless specified otherwise.

Background

Peace Agreement with the FARC

The Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) started peace talks in October 2012 to end their decades-long armed conflict.

In August 2016, the parties reached an accord in Havana, Cuba.[2] The accord included agreement on six points, including on issues relating to political participation, victims’ rights, and drug policy. The accord, however, was narrowly defeated in an October 2, 2016, national plebiscite.[3] The government and the FARC engaged in renewed negotiations, including government talks with opponents of the accord, reaching a new agreement in November 2016.[4]

On June 26, 2017, the UN mission in Colombia verified that FARC guerrillas who accepted the agreement with the government had handed their weapons over to the mission.[5] In total, the government verified that 6,200 former FARC fighters, as well as 3,300 militiamen, had demobilized under the accord (the demobilization of FARC members in Tumaco is discussed in detail below).[6] In September, the demobilized guerrilla group formally announced its political party, the Revolutionary Alternative Force of the Common People (FARC political party).[7]

The peace process brought an overall decrease in conflict-related abuses in Colombia, starting with a FARC ceasefire in mid-2015. In 2017, Colombia had the lowest homicide rates in at least a decade (data through early October 2018, however, suggests homicide rates are again increasing).[8] The number of people displaced annually, typically more than 200,000 before the accord, was around 100,000 in 2017.[9]

The benefits of the accord, however, have not reached many areas of Colombia, including Tumaco.

Tumaco

The municipality of Tumaco, in southwestern Colombia, is home to about 210,000 residents, 95 percent of whom identify as Afro-Colombian.[10] Slightly over half of the municipality’s population lives in the city of Tumaco, Colombia’s second-largest Pacific port.[11] The city straddles two islands–Morro and Central–as well as a larger territory on the mainland. Much of Tumaco’s rural population lives on indigenous reserves and on land that is collectively owned and governed by what are termed Afro-Colombian “community councils.”

According to government figures from 2011, the most recent year for which such data was available at time of writing, about half of Tumaco’s population faces unmet basic needs such as adequate housing and public services.[12] Government figures show that over 15 percent of Tumaco residents live in extreme poverty.[13]

Tumaco is among the world’s largest sources of coca—the raw material of cocaine. The United Nations Office on Drug and Crime (UNODC) reports that in 2017, roughly 19,000 acres were under coca cultivation in Tumaco. Despite a 16 percent decrease compared to 2016, more coca was planted in Tumaco than in any other municipality in Colombia, which is by far the world’s largest coca producer.[14]

Tumaco’s local government institutions are chronically mismanaged and corrupt. In 2016, Colombia’s Inspector General’s Office barred former Tumaco mayor Neftalí Correa Díaz from holding public office for 14 years, after accusing him of irregularities in awarding a contract to provide internet service to 36 schools in the city.[15] On March 5, 2018, the Inspector General’s Office suspended mayor Julio Cesar Rivera Cortés from office, arguing that he had arbitrarily removed officials from the city’s hospital so he could fill their positions with political allies.[16] (He returned to office in June after the end of his three-month suspension.)[17]

Tumaco and other municipalities along Nariño’s Pacific coast have long suffered horrific abuses at the hands of right-wing paramilitaries and their successor groups, as well as left-wing guerrillas. As Colombia’s Constitutional Court found in 2014, “the Pacific region of Nariño has, historically, been a strategic point of great importance for several armed groups which have tried to control the area to handle drug trafficking routes, consolidate their military strategies and press and control productive projects” in the area.[18] These groups, the court found, have engaged in such serious abuses as terrorist attacks, homicides, threats, enforced disappearances, and sexual violence.[19]

Government figures show that more than 500,000 people have left their homes in Tumaco since the year 2000.[20] On July 10, 2018, the Special Jurisdiction for Peace—a body created to try alleged perpetrators of abuses committed during the long conflict with the FARC—prioritized the abuses committed by the FARC and Colombian Armed Forces in Tumaco, as well as in two neighboring municipalities, Ricaurte and Barbacoas, and concluded that the three municipalities “had suffered a profound impact in their social structures, leadership, and local identity due to the armed conflict.”[21]

FARC Demobilization in Tumaco

The main FARC unit operating in Tumaco was the mobile column “Daniel Aldana,” which operated in urban areas and in southern rural areas.[22] The “Mariscal Sucre” column of the FARC was adjacent to it and operated farther north.[23]

Starting in August 2016, guerrilla fighters from these two units gathered in an area known as El Playón, in rural Tumaco, to prepare for their demobilization.[24] After the peace accord was signed in November 2016, most members moved to La Variante, in Tumaco, a Transitional Local Zone for Normalization (Zona Veredal Transitoria de Normalización, ZVTN)–one of the areas designated in the peace accord for the laying down of weapons.[25]

The FARC demobilization in Tumaco was undercut by a range of factors which contributed to the formation of dissident groups. According to researchers and government officials interviewed by Human Rights Watch, these included:

- The “Daniel Aldana” column did not fully agree with the peace process, in part because, unlike other units, it reached its peak of power during the peace negotiations and thus had the most to lose by laying down its weapons.[26] It was also less politically oriented and more deeply embedded in crimes and drug trafficking than other FARC units.[27]

- The FARC demobilization in Tumaco was led by FARC commander Henry Castellanos Garzón, whose nom de guerre was “Romaña” and who had not served in Tumaco during the war.[28] He appears not to have known about several hundred of them; about 500 FARC militiamen operating in Tumaco were not identified as such by the FARC until August 2018–a year after the agreed deadline.[29]

- The demobilization zone lacked electricity and potable water when the FARC arrived there, which may have led some guerrilla fighters to abandon the peace process.[30]

- The Gaitanist Self-Defenses of Colombia (AGC), a group that emerged after a flawed demobilization of paramilitary death squads in the 2000s, tried to obtain control over Tumaco in 2016 and 2017.[31] Analysts indicate that some FARC commanders supported the creation of armed bands to impede the arrival of the AGC.[32]

- Some armed groups threatened FARC guerrillas as they demobilized.[33] It is likely that some guerrillas abandoned the process because they felt their security was not guaranteed.

- The demobilization occurred in a context where there were extensive opportunities for criminal money-making, given large-scale drug trafficking and production in the area.[34]

- Local drug dealers tried to take advantage of the demobilization process to escape extradition to the US. As part of the peace process, the FARC submitted to the Colombian government a list of its members in Tumaco, but that list included the names of several drug dealers known not to be members of the FARC.[35] Government officials told Human Rights Watch that the FARC in Tumaco sold places on the list to drug traffickers who sought to benefit from justice provisions in the peace accord such as a guarantee against extradition for crimes committed before December 1, 2016.[36]

Armed Groups in Tumaco since FARC’s Demobilization

The groups currently operating in Tumaco–or that have operated in Tumaco since the FARC started its demobilization—that Human Rights Watch has identified as responsible for abuses include the following:

People of Order (Gente del Orden, PO)

The People of Order were formed in mid-2016, mostly by young people who had worked for the FARC in urban Tumaco.[37]

Humanitarian organizations operating in Tumaco, analysts, and press reports indicate that many of these fighters had previously been part of the Rastrojos, a paramilitary successor group that the FARC expelled from urban Tumaco in 2013.[38] Its members put themselves under FARC control in order to avoid being killed, reports indicate.[39]

According to humanitarian organizations operating in the area, many FARC members who later joined the People of Order initially choose not to demobilize within the terms of the FARC accord because of poor treatment they received from FARC commanders–including insults and orders that they perform heavy work—in El Playón, where the FARC units in Tumaco gathered prior to the demobilization.[40]

The People of Order were initially commanded by Yeison Segura Mina, alias “Don Y,” a former FARC guerrilla who did not demobilize, and who, Tumaco residents and researchers indicate, received money from local FARC commanders to guarantee the safety of demobilized FARC guerrillas and support social projects in Tumaco.[41] On November 12, 2016, FARC guerrillas summoned Don Y to a meeting about the disbursal of these funds in San Pedro del Vino, in Tumaco. Don Y attended the meeting with over 20 Tumaco social leaders whom he had supported in social projects, one of them told Human Rights Watch.[42] Don Y was killed there.[43]

Don Y’s brother, Victor David Segura Palacios, alias “David,” then took command of the People of Order and renamed it the United Guerrillas of the Pacific.[44] Analysts told Human Rights Watch that David blamed some members of the People of Order for supporting the FARC in killing his brother and declared them a “military objective.”[45] In January over 300 People of Order members sent a letter to Tumaco’s mayor and other authorities publicly announcing they wanted to demobilize within the FARC peace accord.[46]

After the FARC rejected them, 126 fighters, 27 of whom were children, demobilized individually–not through the FARC pact–under the leadership of fighters known as “Pollo” and “Cardona.”[47] The rest joined David in the United Guerrillas of the Pacific.[48]

United Guerrillas of the Pacific (Guerrillas Unidas del Pacífico, UGP)

As noted above, the United Guerrillas of the Pacific were formed between late-2016 and early 2017 under the leadership of David, the brother of the murdered Don Y.[49]

In threatening pamphlets that appeared in Tumaco in March and April 2017, the UGP declared members of the People of Order who demobilized to be their “military objective” because they believed that some had been involved in the murder of Don Y.[50] Some People of Order members were reportedly killed by UGP fighters.[51]

The UGP currently operates in several municipalities in Nariño. In Tumaco, it operates in neighborhoods of the city, as well as in northern parts of the municipality such as Pital de la Costa and San Juan de Pueblo Nuevo.[52] Humanitarian workers operating in the area told Human Rights Watch that they estimated that the UGP have at least 250 fighters.[53]

On September 8, 2018, UGP commander David died during a joint operation against the UGP by police and navy officers.[54] Credible press reports indicate that the UGP are now commanded by a man known as “Borojó.”[55]

Oliver Sinisterra Front (Frente Oliver Sinisterra, OSF)

The Oliver Sinisterra Front was created in late 2017 by former FARC guerrilla commander Walter Patricio Artízala Vernaza, alias “Guacho,” in Alto Mira y Frontera, a rural area in southern Tumaco.[56] Guacho had been a mid-level commander there during his time in the FARC beginning around 2006—this experience, analysts indicate, left him extensive connections with coca growers and international and local drug dealers that he later used to create the OSF.[57]

The Front has disseminated several pamphlets arguing that the peace process with the FARC was a “fraud” by the government. Yet humanitarian organizations working in Tumaco told Human Rights Watch they doubt that position is sincerely held, and said that they believe it is more likely a pretext aimed at advancing the OSF’s drug trafficking interests.[58]

Since late 2017, the OSF has hired many of the 126 fighters who formerly belonged to the People of Order and had demobilized and survived attacks by the United Guerrillas of the Pacific.[59] They operate in urban areas of Tumaco and some people still call them “People of Order.”[60]

OSF operates in several urban neighborhoods in Tumaco—acting jointly with former members of the People of Order—and in several rural areas, including on the border with Ecuador, as well as in the Ecuadorian province of Esmeraldas.[61]

In June 2018, a Colombian prosecutor estimated OSF’s strength at about 450 members (including unarmed militiamen).[62]

Guacho has become well-known and one of the government’s most wanted men since three Ecuadorian press workers (journalist Javier Ortega, photographer Paúl Rivas and their driver, Efraín Segarra) were kidnapped in March near the border and–days later—killed.[63] The Colombian and Ecuadorian governments have blamed the OSF for their kidnapping and murder. (See section on disappearances, dismemberment, and kidnapping below.)

On September 15, 2018, the Colombian government announced that Guacho had been wounded in a military operation in Nariño and that the armed forces were “cordoning” the area to find him.[64] But on September 18, government authorities said they could not confirm whether he had been hurt.[65] Guacho remained at large as of this writing in December 2018.

Gaitanistas Self-Defenses of Colombia (Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia, AGC)

The AGC were founded in the Urabá region of Antioquia in 2006 as a result of a deeply flawed demobilization of paramilitary groups.[66] They are also known variously as Clan del Golfo, Clan Úsuga, and Urabeños.

The group fields its own full-time fighters and has hired criminals operating in diverse areas of Colombia. The full-time fighters operate in several rural areas of the country and are organized into blocs led by regional and front commanders. The subcontractors are members of local gangs who are hired by AGC commanders.[67]

Staff members at humanitarian organizations operating in Tumaco say that in 2016 the AGC was trying to take control over areas of Tumaco held by the FARC.[68] In 2017, however, the AGC was mostly expelled from the territory by the FARC and the People of Order.[69] Analysts say that currently AGC only operates in a few neighborhoods in the urban central island of Tumaco.[70]

Group led by “Mario Lata”

Several Tumaco residents and a local judicial official told Human Rights Watch that a new group has emerged in Tumaco led by Mario Manuel Cabezas Muñoz, alias “Mario Lata.”[71]

“Mario Lata” is 28-year-old former FARC guerrilla fighter, according to his criminal record.[72] In 2009, he was part of Los Rastrojos and, some press reports indicate, he could have been part of paramilitary death squads prior to that.[73] He has been imprisoned several times, including, most recently, in March 2016, when he was arrested and charged with murder.[74] In October 2016, the Attorney General’s Office reported that he was “coordinating” from prison a group called “The New People” (La Nueva Gente) that operated in Tumaco and was implicated in acts of murder and extortion.[75] In April 2018, however, a judge released him because he had been in pre-trial detention too long.[76] The criminal process against him remains pending.

Between July 26 and 28, 2018, shootouts in several neighborhoods in Tumaco caused more than 600 people to flee their houses.[77] Tumaco residents told Human Rights Watch that the shootouts were between a group of fighters working for the United Guerrillas of the Pacific that had been paid to work for “Mario Lata” and another group of United Guerrillas of the Pacific fighters.[78]

Widespread Abuses

Killings

FARC dissident groups have been responsible for multiple killings in Tumaco.

At least 210 people were killed in Tumaco in 2017, making the annual homicide rate there at least 100 per 100,000 people, more than four times the national rate.[79] Preliminary government data shows that 195 people were killed between January and October 2, 2018—an increase of 47 percent over the same period in 2017.[80]

Three prosecutors investigating these cases, as well as two human rights officials who take testimony from the relatives of victims, told Human Rights Watch they believe that FARC dissident groups have committed the majority of the homicides.[81] Colombia’s police report that over 70 percent of the homicides in Tumaco in 2018 through early October were committed by hitmen (“sicariato”) and over 50 percent involved tit-for-tat killings among armed groups.[82] One scholar estimates–based on the historic links between homicides and armed groups in Tumaco, the weapons used for the killings, and the neighborhoods reporting most murders—that around 80 percent of the homicides in Tumaco are committed by armed groups, mainly FARC dissident groups.[83]

In researching this report, Human Rights Watch documented 21 killings in Tumaco committed since mid-2016. These include four separate murders of community activists and the murder of eight people in a single-incident, allegedly committed by police officers.

In some cases, people not involved with armed groups are apparently killed in “retaliation” for killings of people in other neighborhoods, several residents told Human Rights Watch.[84] We interviewed a woman whose 20-year-old son was killed in November 2017 as he was entering a Tumaco neighborhood. An eyewitness told his mother that some 40 men arrived in a boat and asked him to locate someone for them. The victim said he did not know where the person was, so one of the men ordered him to get on his knees and shot him. His mother believes he was killed because the dissident group that controls her neighborhood had killed a man from the killers’ neighborhood earlier that day.[85]

At times, FARC dissident groups employ flamboyantly brutal violence in an apparent effort to terrorize the populace. A 26-year-old fisherman was found in an estuary, his hands tied with rope, on May 6, 2018. His body was riddled with dozens of gunshot wounds, as well as apparent machete wounds, a relative of the victim told Human Rights Watch. One foot was almost dismembered. A sign on his chest read, “for thieving and snitching.”[86]

Killings of Community Leaders

Murder of human rights defenders is a serious problem in Colombia. The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, which uses a broad definition of human rights defenders that includes many Afro-Colombian, indigenous, and community leaders, identified 121 killings of human rights defenders in 2017.[87] As of November 30, 2018, the High Commissioner had documented 74 such cases and was verifying 57 others.[88]

Tumaco, with at least seven community leaders reported killed since January 2017, is the municipality with the most such killings since 2017.[89] Human Rights Watch documented four such cases, including four where evidence points to a FARC dissident group as the perpetrator:

José Jair Cortes, a member of Alto Mira y Frontera’s community council, was shot and killed on October 17, 2017, while he was visiting his ailing wife in Alto Mira y Frontera, a rural area in southern Tumaco.[90]

In September 2017, “Cachi,” a commander of the Oliver Sinisterra Front, had called Cortes and other members of the Neighborhood Action Committee to a meeting in Mataje, Ecuador. Cachi told the neighborhood leaders to gather people for a protest against the forced eradication of coca plantations, an eyewitness told Human Rights Watch.[91] The leaders told “Cachi” they wouldn’t support the protest, so he told them that they would become a “military objective” of the Oliver Sinisterra Front.[92] Eighteen people from the community, including 15 members of the Neighborhood Action Committee, fled to the city of Tumaco on September 26, one of them told Human Rights Watch.[93]

Cortes had protective measures from Colombia’s Unit of National Protection (Unidad Nacional de Protección, UNP), consisting of a cellphone, a bulletproof vest, and money for transportation.[94] But on the day of the killing he was not wearing his vest, apparently because he thought doing so would draw attention to himself and expose him to more danger.[95]

Luz Jenny Montaño, a community and religious leader, was killed on November 12, 2017 in the Tumaco neighborhood of Viento Libre.[96] In August 2018, the Attorney General’s Office said it had issued arrest warrants against three members of the United Guerrillas of the Pacific.[97]

Margarita Estupiñán Uscátegui, the president of the Neighborhood Action Committee of El Recreo neighborhood, a neighborhood association in the rural hamlet of Vaquerío, was shot and killed on July 3, 2018.[98] A group of armed men shot Estupiñán when she was entering her house that night, according to press reports.[99] Her body had four bullet wounds, two in the head and two in the back.[100]

In August 2018, the Attorney General’s Office said it had issued arrest warrants against five members of the Oliver Sinisterra Front for involvement in the murder.[101] One of the alleged gunmen was arrested on September 6, 2018.[102]

Holmes Alberto Niscue, a leader of the indigenous Awá reserve Gran Rosario, in southern Tumaco, was killed on August 19, 2018. Two men approached him and asked him to go with them, community leaders said in a press release. When he refused, the men shot him three times in the head, according to the press release.[103]

Niscue had received death threats from the Oliver Sinisterra Front in June, according to press reports and leaders of his indigenous community.[104] According to press reports, the Front apparently accused him and other leaders of the reserve of having called the army prior to a June 4, 2018 military operation that killed seven dissidents.[105] On May 29, the leaders of the indigenous reserve had convened a meeting to tell Front members they had to leave the reserve.[106] In response to these threats, the UNP granted Niscue a bulletproof vest and a cellphone.[107]

Massacre by police

On October 5, 2017, seven people were killed in a 300-person protest against the eradication of coca in the rural hamlet of El Tandil, in Tumaco.

The National Police initially alleged that the Oliver Sinisterra Front had fired “at least five cylinder bombs” and later “fired indiscriminately with rifles and submachine guns” at protesters and members of the security forces.[108]

On October 6, however, the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office visited the area and collected testimony from witnesses who said that the Front had not attacked the protest and that the protest instead was “attacked by members of the anti-narcotics police.”[109] Human Rights Watch reviewed testimony taken by government officials with two relatives of victims who corroborated this account.[110]

On December 22, 2017, the Attorney General’s Office announced it would charge the army and police commanders in charge of the operation with murder.[111] Prosecutors had yet to file those charges as of this writing in December 2018.[112] A prosecutor told Human Rights Watch that he and his colleagues have struggled to identify the perpetrators because police delayed investigators’ access to information about the police operation.[113]

Disappearances, Dismemberment, and Kidnapping

FARC dissident groups have committed multiple disappearances in Tumaco. As of September 2018, the Attorney General’s Office was investigating 42 cases of alleged “enforced disappearances” committed between January 2017 and September 2018.[114] Yet the number of disappearances could be much higher. Many missing people are never reported, residents, prosecutors, and human rights officials told Human Rights Watch.[115]

In researching this report, Human Rights Watch documented 14 disappearances that have occurred in Tumaco since mid-2016. In eight cases, we spoke directly with victims’ relatives. In the remaining six, we examined testimony by victims’ relatives taken by government officials and the staff of humanitarian organizations. In 9 of 14 cases, there is credible evidence, including testimony of witnesses and threats to relatives looking for the disappeared, that armed groups operating in Tumaco were responsible for the abuses. Several of the cases are detailed below.

Residents believe that the bodies of the disappeared of Tumaco were thrown into the sea, into estuaries, or into rivers.[116] Several victims’ relatives told Human Rights Watch that they went to look for the bodies of loved ones at a beach known as Bajito Vaqueria. We received credible allegations from local rights groups, humanitarian organizations working in Tumaco, and the press indicating that at least 15 bodies have been found in rivers, estuaries, or the sea since September 2016.[117]

Residents also believe that many bodies are thrown into scrubland along the road to Pasto known as El Tigre. Several victims’ relatives told us they had looked for bodies there. “If someone doesn’t come back home by 6 am,” a community leader told Human Rights Watch, “we first go to El Tigre and then to the morgue.”[118] On January 3, 2018, the decaying body of an unidentified man was found, with hands tied, in El Tigre.[119]

In May 2018, Colombia’s inspector general said that some people who are disappeared are tortured and dismembered and that there are several houses where such torture is carried out.[120]

Many Tumaco residents told Human Rights Watch that they know of such houses in their neighborhoods.[121] Yet there is limited corroborating evidence. Following the inspector general’s report, prosecutors raided several houses, but could not find evidence that people had been tortured or dismembered there.[122] Colombia’s National Institute of Legal Medicine has registered two cases of people being dismembered in Tumaco since January 2017.[123]

Some residents believe this practice has been learned from other armed groups that formerly operated in the city.[124] Indeed, in 2014, Human Rights Watch interviewed residents of two neighborhoods who said the Rastrojos maintained three houses there where they repeatedly took victims to dismember them.[125]

Kidnapping and Killing of Ecuadorian Press Workers

On March 26, 2018, three Ecuadorian press workers (journalist Javier Ortega, 32; photographer Paúl Rivas, 45; and their driver, Efraín Segarra, 60) were kidnapped in Mataje, Ecuador, near the Colombian border. They worked for the Ecuadorian newspaper El Comercio and were visiting the area to gather information on the operation of armed groups. [126]

On April 2, Colombian news outlet Noticias RCN released a 22-second video in which the men, seen in chains, delivered a message to Ecuadorian President Lenin Moreno. The victims said that they were being held by the Oliver Sinisterra Front which demanded that the Ecuadorian government release three detainees from the group and annul an agreement with Colombia to fight terrorism.[127]

On April 11, the Front released a pamphlet saying that “landings” by the Ecuadorian and Colombian authorities in the area “had produced the death” of the three press workers.[128] The next day, Noticias RCN said it had seen photos of their dead bodies–their deaths were confirmed by President Moreno the next day.[129]

Colombian and Ecuadorian authorities blamed the Oliver Sinisterra Front for their murders. In July, the Colombian Attorney General’s Office charged a Front fighter for his alleged role in the kidnapping and subsequent murder.[130]

Selected Disappearance Cases

Andres Perdomo, 26, and Iván Mejia, 33, arrived in Tumaco from the province of Tolima on June 6, 2018—and visited the rural area of Guayacana, where they hoped to sell beauty products.[131]

Maria Amezquita, Andres’s mother, told Human Rights Watch she tried to contact him on June 7, but could not reach him. Four days later, Iván’s mother called her to say that the hotel in Guayacana had reached out to let her know that the young men had checked in but had not returned on the night of June 7.

Maria sold her TV to buy a bus ticket to Tumaco, where, with Iván’s mother, she undertook a search. They posted posters of their sons in the city of Tumaco, visited places in Guayacana where they had been, and asked authorities for help. In late June, they found Iván’s luggage in a restaurant in Guayacana. The owner said the pair had asked her to take care of it but had never come back. As of writing, the mothers have not been able to find Andres and Iván. A prosecutor investigating the case described evidence suggesting a FARC dissident group was responsible for the disappearances.

José (pseudonym), 35, disappeared on December 2017 from his neighborhood in the city of Tumaco. He was helping his wife get ready for a saint’s-day feast when he stepped out, saying he would be back shortly.[132] He never came back.

His family never heard from him or found his body. They have not reported the crime, for fear of reprisals from an armed group that was operating in that neighborhood at the time of José’s disappearance, a relative told us. The relative would not identify the group, but according to a local researcher and press reports it was the People of Order.[133] “Sometimes people ask us how we can live like this, but we get used to it,” a relative of José told us.

Mario (pseudonym) disappeared in April 2018 from a rural town in Tumaco. The night of his disappearance, five armed men arrived at his house and told him and his wife that they had to leave. [134] When Mario refused to leave, one of the men hit him in the head with a gun, and the attackers told his wife to leave. She went to a neighbor’s house, but the men held Mario. The next day, at 8 a.m., his wife went to the city of Tumaco. She has not heard from Mario since.

Pedro (pseudonym) disappeared in February 2018 from a neighborhood in urban Tumaco. The afternoon of his disappearance, two armed men approached him as he was leaving his house with his girlfriend, his girlfriend said in testimony Human Rights Watch reviewed. The men pointed a gun at Pedro’s head. She asked what was going on, but the men told her to be silent, saying that she and Pedro were “snitches” and that she had a few hours to leave the neighborhood. The men took Pedro and she fled, crying, taking refuge later that day at a relative’s house in a rural town in Tumaco.[135]

Juan Pablo (pseudonym), a 21-year-old soldier, disappeared on April 9, 2017. He had gone to a nightclub with friends, his mother and sister told Human Rights Watch, and when he did not return the next day, they asked his friends what they knew.[136] One friend said Juan Pablo had been at the club until 2 a.m. that night, and had gone to a birthday party afterwards. He had stayed at the birthday party until around 5 am, they learned from another friend. His mother looked for him at Bajito Vaqueria, the beach where dead people are often found, as well as in the morgue. The family also asked around in the neighborhood where the birthday party had taken place but people there told them to leave: “They told us that his relatives couldn’t go in, that they would kill us,” Juan Pablo’s mother told Human Rights Watch. She had visited that neighborhood several times before.

Juan (pseudonym), a 37-year-old moto-taxi driver, disappeared in February 2018, his parents told Human Rights Watch.[137] The day after Juan’s disappearance, a man told his parents that Juan had taken a passenger to the neighborhood of Viento Libre at around 5 p.m., on the center island of Tumaco. Residents said a man in Viento Libre had stolen the motorbike that Juan was driving, and when he tried to get it back, a FARC dissident group killed him and buried his body, but his body has not been found. The motorbike was found in another neighborhood a week later. The owner of the motorbike had to pay 500,000 COP (around US$160) for its return. The owner did not tell Juan’s parents who had sold him back the motorbike, they said.

Josue (pseudonym), a 37-year-old moto-taxi driver, disappeared in January 2017, his wife told Human Rights Watch.[138] On the night of his disappearance, Josue was working in the city of Tumaco. When he did not return at 10 p.m. as he usually did, his wife called some friends who said they had last seen him an hour earlier. She went to the morgue the next day and filed a criminal complaint. She also searched the El Tigre wasteland. A friend of Josue’s asked “permission” to enter a neighborhood controlled by a group different from the one that controlled Josue’s neighborhood, so that they could look for him. The friend stopped the search later, Josue’s wife told us, because a man approached him in the street and told him to stop looking for Josue. The man said he would “put the family in danger” if he continued the search, his wife said.

Josue’s wife continued looking for him but had no luck anywhere. Every time she hears that a body has been found in Tumaco, she said, she goes to see whether it is Josue: “At least I would have more peace,” she said, “if I knew what happened to him.”

Sexual violence

Armed groups in Tumaco, including FARC dissident groups, also commit rape and other sexual abuses. From January 2017 through the end of September 2018, 74 people in Tumaco were victims of “crimes against sexual integrity” (including rape and other sexual crimes) related to armed conflict, according to Colombia’s Victims’ Registry—by far the highest such figure for any municipality in Colombia.[139] Official statistics likely vastly underrepresent the true scope of sexual violence in Tumaco, as many cases go unreported.

Prosecutors, human rights officials, and humanitarian health workers told Human Rights Watch that many victims do not report crimes in part because they fear retaliation.[140] Sometimes victims report the crimes but do not disclose that the perpetrators belonged to an armed group. Human Rights Watch interviewed three women who said they had not reported crimes against them.

Human Rights Watch documented 11 cases of rape or attempted rape that have occurred in Tumaco since mid-2016, including the cases detailed below. In seven of the cases we interviewed the victims; in the others we examined testimony given by the victims to government officials, staff at humanitarian organizations, and others. In seven of the 11 cases, victims identified the perpetrators as apparent members of an armed group because the men said they belonged to a group, the victims had seen the men before and knew they were members of a group, or the men were armed, hooded, and wearing military-style clothing.

A prosecutor and two human rights officials told us that in many cases women become sexual partners of armed men as a result of sexual exploitation. As one put it, “they can’t say ‘no’ to the commander.”[141] Human Rights Watch documented six cases in which women decided to leave their homes after armed men ordered them or their daughters to become their sexual partners. In three of the cases, when the women refused, the armed men threatened to rape them or kill them or their relatives.[142]In the three others, parents fled with their children, fearing that armed men would recruit them or rape them.[143] One woman who fled from a town in rural Tumaco described what happened to her:

[One afternoon in] May 2018, I was in my house [when] an armed young man from one of the groups arrived. He said that we [had] to have a relationship. I answered that I was not interested. He got upset and said that he was in command of the zone and that he was going to sleep there whether I liked it or not. He left [for a moment], and I seized the moment to leave with my son to a neighbor’s house, in hiding. The next day, we went to [the city of] Tumaco.[144]

Selected Cases of Rape or Attempted Rape

Gabriela (pseudonym), a 14-year-old girl, was raped in mid-October 2017 in a town in rural Tumaco. Four armed men arrived at Gabriela’s house one night around 11 p.m., Gabriela’s teacher, who learned of the events from Gabriela’s parents, told Human Rights Watch.[145] The men told Gabriela’s parents that “the commander” had asked for the girl, and they took her away. The armed men returned Gabriela to her house the next morning with various wounds. She told her parents that several men had raped her. The family promptly sought medical attention for Gabriela at a nearby hospital, and when she was out of danger, they left home, fearing reprisals for having reported the case.

María (pseudonym) was raped in May 2018. The night she was raped, a group of armed men approached her in the streets of a neighborhood in Tumaco and forced her to go with them, an official of a humanitarian organization who had spoken with María told Human Rights Watch.[146] The men took her to a nearby house where another man raped her. She identified the perpetrator as the commander of the People of Order in the neighborhood, whom she had seen before. The perpetrator told her she should not report the crime because the group knew her and would retaliate. The commander, whose name is withheld for privacy and security reasons, was killed a few months later. The victim fled Tumaco.

Natalia (pseudonym) was raped in July 2017. One night that month, a group of men appeared at her house in rural Tumaco, saying they were part of an armed group and needed help attending to a guerrilla fighter who was ill.[147] The armed men forced her and her husband out of the house. One of the men took her to a hill, where he raped her. Natalia returned to her house where, hours later, her husband arrived, with bruises all over his body. Days later, the family fled their home.

Gladys (pseudonym), 35, went for a walk in a Tumaco neighborhood with her children, ages 5, 10, and 12, one evening in early November 2016, arriving home at around 9 p.m.[148] Gladys laid down to sleep, but soon heard a noise at the door. At first, she thought it was a cat and waited, listening. Some 20 minutes later, she went to the door to see what might have made the noise and an armed man barged into the house, grabbed her, and tried to rape her, Gladys said. She yelled, and he eventually left through a window. The pressure of his fingers left a scar on Gladys’s neck, which she still had when Human Rights Watch interviewed her.

The next day, at night, the man returned to Gladys’s house and told her that if she reported the abuse to the police, he would kill her. She was afraid to report the crime and did not do so until a year-and-a-half later, in July 2018.

Gladys recognized the man at the time of the attack and identified him as a member of an armed group that was operating in her neighborhood. She would not identify the group in her interview with Human Rights Watch. Weeks after the crime, Gladys left for the rural area of Tumaco where she was still living when we interviewed her. She explained that she had relocated from her town to “forget a bit what happened.”

Fatima (pseudonym), 28, was abducted one night in mid-2016 while waiting on a Tumaco city street for friends who were going to pick her up to go to a nightclub.[149] Three men took her from behind and forced her into a car. They drove her to a house in another neighborhood, where three men held her for five days, naked. Her captors never allowed her to cover up, and a man shrouded by a hood repeatedly raped her.

Then they took her to another house where the same hooded man raped her again, and two others repeatedly hit her on her knees. Fatima asked why they were assaulting her, but they did not respond, she told Human Rights Watch.

A few days later, the men released Fatima, dressed, on a populous street in downtown Tumaco, where a woman helped her flag down a police officer. But Fatima has never reported the rapes. She fears retaliation against her or her two siblings. A few weeks after the men released her, Fatima fled Tumaco. She had not received medical, psychosocial, or other care for the rapes when Human Rights Watch interviewed her.[150]

A “group” was operating in her neighborhood when the events occurred, Fatima said, and she believes members were responsible for the assault because they were armed and wearing hoods.

Daniela (pseudonym), 27, was raped one night in August 2016 in a rural town in Tumaco.[151] As Daniela left her house, two armed men threw her to the floor in the street, punched her in the head, and tied her hands. For about an hour, they took turns raping her, she said.

Daniela eventually fainted. The men left her in the street, with her hands tied, and her relatives found her the next morning. The attack left her with scars on her hands and face. She never received post-rape medical or psycho-social care, and Daniela never reported the crime to authorities for fear of reprisals. Her rapists told her they would kill her if she “opened her mouth,” Daniela told Human Rights Watch. She thought the men belonged to an armed group that was then operating in her town because they were wearing hoods, black clothes, and boots.

Daniela left home for a few days after the attack to live with her sister in urban Tumaco, but she eventually went back to her village. She lives in fear, as several “groups” constantly come and go, she told Human Rights Watch. “Too many things have happened to me, and I have them on my mind,” she said. “Sometimes I sit and cry to myself.”

Human Rights Watch interviewed two women who were raped in the same town as Daniela, and they described similar attacks.[152]

Recruitment and Use of Children

FARC dissident groups have recruited children in Tumaco. As of September 2018, the Attorney General’s Office was investigating 21 cases of child recruitment committed in Tumaco since January 2017.[153]

Group members ask children to join, often offering them pay, and threaten to kill them or their families if they decline, residents, human rights officials, and officials of humanitarian organizations operating in Tumaco told Human Rights Watch.[154] Many Tumaco residents said that children were more vulnerable to recruitment due to poverty and lack of economic opportunities.[155]

Human Rights Watch documented 10 cases in which families fled their towns or neighborhoods after a group attempted to recruit a child in their family.[156] Victims of attempted recruitment include boys and girls as young as 15. The following is the testimony of a mother displaced from her town in rural Tumaco in April 2018:

[One morning in] April a bunch of men arrived at my hamlet offering my 15-year-old son work with them. I told them my son was not going to get involved with them. They insulted me and said that if I didn’t accept, they would kill me and my family, that we should leave the hamlet. That night, we fled to [the city of] Tumaco.[157]

On July 27, 2018, a grenade exploded in a classroom in a primary school in Tumaco at around 2:15 p.m., three teachers told Human Rights Watch.[158] The classroom is normally used by roughly 30 seven-year-old children at that hour, but it was empty that day because the children and teachers were attending a cultural event. Part of the classroom’s roof and the metal door were broken. The school was closed when Human Rights Watch visited a few days later, and some of the children were attending classes at another school’s cafeteria, a few blocks away. “I can’t get over the pain of thinking that the children could have been there,” a teacher told Human Rights Watch.

The attack appears to have been carried out by an armed group operating in the neighborhood. That week, there were shootouts nearby that caused more than 600 people to flee their homes.[159] Tumaco residents told Human Rights Watch that the shootouts were between a group of fighters working for the United Guerrillas of the Pacific that had been paid to work for “Mario Lata” and another group of United Guerrillas of the Pacific fighters.[160]

There are often shootouts in the early morning hours between rival armed groups around the school, teachers said. When Human Rights Watch visited, we found a bullet casing in the school’s main door. To reduce the risk that students would be trapped in a shootout, which is more likely to occur when its dark, the school decided in June to establish an “emergency schedule,” allowing students to arrive at 7 am, by which time it is light out, instead of 6:30 am.[161]

Colombia has not endorsed the Safe Schools Declaration, an inter-governmental political commitment drafted under the leadership of Norway and Argentina in 2015. Countries that endorse the declaration commit to take several common-sense steps that can make it less likely that students, teachers, and schools will be attacked during times of armed conflict. These steps also help mitigate the negative consequences when such attacks occur.[162] These include conducting more investigations and prosecutions of war crimes involving students, teachers, and schools; improving monitoring and reporting of such attacks; acting faster to restore access to education when schools are attacked; and using a set of guidelines to minimize the use of schools and universities for military purposes, such as for bases or barracks.[163] As of November 2018, 82 countries around the world have endorsed the Safe Schools Declaration, including 13 Latin American countries.[164]

Use of Antipersonnel Landmines

The 1997 Mine Ban Treaty, to which Colombia is a party, comprehensively bans antipersonnel landmines. Their use is a violation of international law.[165] Yet the Oliver Sinisterra Front is planting landmines in rural areas of Tumaco, residents of those areas, human rights officials, humanitarian workers and a prosecutor told Human Rights Watch.[166] The Colombian army has also blamed the Front for planting landmines in Tumaco.[167]

According to government figures, two civilians died and three were injured by antipersonnel landmines in Tumaco between January and August 30, 2018.[168] It is unclear, however, whether these incidents were caused by landmines planted by FARC dissident groups or by landmines planted in the area years earlier.

FARC dissident groups often plant landmines on coca plantations to deter forced eradication by security forces, according to a prosecutor, a human rights official, and officials of a humanitarian organization working in Tumaco.[169] In May 2018, two government employees eradicating coca as part of the Presidential Program Against Illegal Crops (Gestion Presidencial contra Cultivos Ilícitos, PCI) were injured by a landmine.[170] In October 2018, one policeman who was eradicating coca in Tumaco was killed by a landmine.[171]

Extortion, Restrictions on Movement, Social Control, and Threats

FARC dissident groups have established tight control over Tumaco residents in both rural areas and urban neighborhoods. According to Colombia’s Victims’ Registry, more than 2,300 Tumaco inhabitants reported threats from armed groups between 2017 and 2018—one of the highest figures in Colombia.[172]

One form of such control is control over residents’ movements between neighborhoods throughout the city of Tumaco.[173] The groups station people at the entrances to neighborhoods, which are often accessed only by a single street. These guards closely monitor the people who enter the neighborhoods.[174] When people not known to the group in control—or people known to come from an area dominated by a rival group—enter, they may be killed, threatened, or disappeared.[175]

Fears of crossing such “invisible borders” cause people to limit the areas of the city in which they travel.[176] The borders ensure a group’s absolute control over its neighborhood. “Groups don’t allow people in because they want to have the community terrorized,” one community leader explained, “so they can do whatever they want.”[177]

Within the neighborhoods they control, FARC dissident groups constrain residents’ movements and activities. They often set specific hours when people can enter or leave.[178] Several residents told Human Rights Watch that they need to return to their neighborhoods before a certain hour to avoid being attacked—or at least body-searched and interrogated.[179]

The groups have established “regulations” for the towns and neighborhoods they control. For example, on April 14, 2018, the Oliver Sinisterra Front circulated a pamphlet in a town in the municipality of Barbacoas, close to Tumaco, indicating they would “establish order in the communities.” The pamphlet said there would be “no room” for “thieves, snitches, rapists and kidnappers” and that public institutions would close at 10 p.m. for “security” reasons.[180]

A resident of a rural area of Tumaco said that the Front appoints people in each town to enforce compliance with the rules.[181] For minor infractions, they may require community labor, such as cleaning the streets.[182] Retribution for serious offenses can include torture or death. “That’s how they punish people,” the resident said, “so others won’t make mistakes.”

The groups also impose “fees” on residents who break rules.[183] These are sometimes a way of obtaining money from people for arbitrary reasons, such as for chatting with neighbors. “They just make the reason up…it’s a way of raising money, and they are the authority,” a community leader said.[184]

The groups regulate daily conflicts.[185] In the city of Tumaco, for example, a woman whose husband was killed in May 2017 told Human Rights Watch that she was afraid of claiming the inheritance because armed men associated with her husband’s lover had told the family they should not claim it.[186] In another case, a woman told us that an armed group had tortured and killed armed men who, for several days, had escorted her home in an intimidating way.[187] “Some people trust the groups more than the law” to solve their problems, she told Human Rights Watch.

FARC dissident groups carry out widespread extortion of businesses in Tumaco, according to residents, businessmen, human rights officials, and prosecutors.[188] Victims are usually owners of businesses, including small stores. At times, FARC dissident groups also extort street vendors, teachers, and fishermen.[189] Sometimes they detain people for a few hours to force them—or the companies they work for—to pay.[190]

Forced Displacement

Government figures show that violence and threats have displaced more than 9,000 people from Tumaco since 2017, giving the municipality one of the highest rates of forced displacement in Colombia.[191] Yet, as with other abuses, the actual figures are likely higher; humanitarian and human rights officials who work with victims told Human Rights Watch that armed groups have, at times, forbidden civilians from reporting their displacement.[192]

Many people leave for fear of being caught in shootouts. FARC dissident groups explicitly tell others to leave their homes or villages because they have not obeyed orders or simply because the groups want their houses or land. The following are testimonies of families who have had to leave their homes due to such threats[193]:

Carlos (pseudonym):

On [a day in] April 2018, two armed men arrived [at my house] around 7 p.m. They said I had to leave my land. I asked why, since I didn’t owe them anything. They answered that if they found me there the next day, I would die, and so would my son. On Saturday [the next day], I left for a friend’s house first thing in the morning.

Dalila (pseudonym):

[One day] in January 2018, around 8 p.m., I was in my house [in rural Tumaco] when we heard a shootout. We left the house to see what had happened. A group of armed men had killed a man. They threatened us, saying that if we reported the case, they would kill us. So that same night, we fled to the house of a relative in [another town in rural Tumaco].

Judith (pseudonym):

[One day in] March 2018, in the afternoon, I was in my house [in rural Tumaco] when I heard people screaming. When I left, I saw that men had my brother. They were hitting him. They are dissidents from Guacho’s group and they were upset because my brother didn’t want to join the group. I told them to leave him and tried to release him, but they threatened to kill us both. Then people from the community appeared. The armed men told us that we had one hour to leave the town. That same night we took a canoe to [the city of] Tumaco.

Justo (pseudonym):

On [a day in] December 2017, a group of armed men arrived at my neighborhood [in urban Tumaco], saying that we had 24 hours to leave our houses. Right now, I’m living in a relative’s house [in rural Tumaco].

Inadequate Protection and Accountability

Police and Military Response

In the months following the peace accord in August 2016, Tumaco’s then-mayor, and the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office warned of the urgent need to establish a strong state presence in Tumaco after the FARC’s demobilization.[194] Humanitarian organizations operating in Tumaco believe that the government’s delay in doing so contributed to the emergence of armed groups in Tumaco.[195]

When Police General Oscar Naranjo took office as vice-president in March 2017, he prioritized the situation in Tumaco and the Colombian government has since launched a series of initiatives to increase the number of police and military officers in the area. In January 2018, the government launched the “Atlas campaign,” increasing the number of security officers in the area and restructuring military and police units already operating there. The government announced that in total, 9,000 security officers would protect residents of Tumaco and nine neighboring municipalities.[196] In May, the government said it would increase the number to 11,200 officers.[197]

In April, the government lunched operation “Tumaco Seguro,” aiming to establish police and military presence around strategic points in the city of Tumaco.[198]

While these initiatives appear to have increased the number of armed group members arrested in Tumaco, they might not lead to significant gains in accountability. As explained in the next section, there are few prosecutors, investigators, and judges available to handle the cases.[199]

And despite the new initiatives, FARC dissident groups in Tumaco appear to be committing serious abuses at a disturbing rate. As noted above, preliminary data from October shows a 47 percent increase in homicide rates in Tumaco compared to the same period in 2017, and a large portion of the increase is likely due to armed groups.

Preliminary data from Colombia’s Victims’ Registry, moreover, shows that 32 people reported crimes against sexual integrity by armed groups between January and October 1, 2018, a rate on par with the 42 such cases reported in all of 2017.[200] And preliminary data from Colombia’s Institute of Legal Medicine shows that 14 people were reported missing between January and September 2018, compared to 16 during the same period in 2017.[201]

According to Tumaco residents, armed conflict analysts, and humanitarian organization officials, the initiatives so far have not worked as planned for several reasons:

- Coca cultivation and drug trafficking enables armed groups to thrive economically.[202]

- Poverty and lack of economic opportunities makes it easier for armed groups to recruit fighters, including children, allowing them to replace members who are captured or killed.[203]

- Police and army officers do not have a permanent presence in the neighborhoods, allowing unarmed men stationed at the entrance of neighborhoods to call fighters when police and army officers enter.[204]

- Prosecutors, judicial authorities, residents, and officials of humanitarian organizations told Human Rights Watch that security forces too often tolerate armed groups or commit abuses themselves.[205] On October 8, 2018, a judge sent four navy officers to pre-trial detention on allegations that they were extorting Tumaco residents.[206] Residents’ distrust of authorities, family links to members of armed groups, and fear of reprisals also limit residents’ cooperation with authorities in many cases.[207]

When President Iván Duque took office in August 2018, he prioritized actions to capture or kill high-level commanders, especially Guacho.[208] On September 8, 2018, David was killed during a joint operation by police and navy officers against the United Guerrillas of the Pacific.[209]

Accountability

The Attorney General’s Office has so far largely failed to ensure justice for serious abuses by armed groups, including FARC dissident groups, in Tumaco.

As of September 2018, prosecutors were investigating 512 cases of murder committed in Tumaco since January 2017. They had indicted people in 17 cases and had convicted only one.[210] They had not charged, let alone convicted, anyone for enforced disappearance, child recruitment, or forced displacement committed since January 2017.[211]

One significant exception is prosecution of those believed responsible for the killing of human rights defenders. Prosecutors have issued arrest warrants against the alleged perpetrators of the seven killings which were documented by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights since 2017.[212]

A key shortcoming is that the municipality of Tumaco only has one judge–known as a “specialized judge” under Colombian law–to try a range of serious crimes, including aggravated murder, kidnappings, child recruitment, and trafficking of more than 5 kilograms of illicit drugs.[213] In August 2018, the single judge was handling 517 cases, scheduling hearings on Saturdays—unusual in Colombia—to cope with the backlog.[214]

In 2014, Human Rights Watch identified the overwhelming caseload of prosecutors as a key barrier to accountability in Tumaco. The number of prosecutors has since increased from 11 to 19, but caseload continues to be a problem.[215]

The only prosecutor investigating disappearances, extortion, and forced displacement in Tumaco in August 2018 was handling 1,500 investigations. These included 600 cases of enforced disappearance.[216] (In addition, prosecutors based in Pasto and Bogotá were investigating some Tumaco cases, but the Tumaco prosecutor has to take many of these to trial.)[217]

In addition to the prosecutor handling disappearances, extortion, and forced displacement, two prosecutors in Tumaco are investigating homicides. Each of them was handling some 750 cases as of August 2018.[218] Two other prosecutors take these cases, as well as others involving serious crimes, to trial.[219] Among the remaining prosecutors, two are in charge of minor crimes, such as robbery, one is in charge of cases where the alleged criminal is caught in “flagrante,” and two are tasked with investigating and prosecuting sexual violence crimes (see section below discussing shortcomings in prosecuting these cases).[220]

The limited number of investigators also impedes prosecutions, several prosecutors told Human Rights Watch. The Technical Investigation Unit (Cuerpo Técnico de Investigaciones, CTI), a body charged with providing investigative and forensic support to prosecutors in criminal cases, had about 10 investigators when we visited Tumaco.[221] A prosecutor told us that there are often no investigators available to take sexual violence reports, for example, because the CTI investigators assigned to that task are called to other tasks, such as participating in house searches or removing corpses.[222]

Tumaco’s prison, located in the rural area of Buchely, is overcrowded.[223] In June 2018, cells with a capacity for 256 prisoners held 584, more than twice as many, a prosecutor told Human Rights Watch.[224] Some prisoners were sleeping in hallways and bathrooms, she said. In March 2018, Colombia’s ombudsperson asked the Constitutional Court to close the Buchely prison and transfer the inmates elsewhere. The prison, he reported, had poor infrastructure–the sewage floods the patio of the prison when it rains, there is insufficient personnel to guard and protect inmates, and health services for inmates are deficient.[225]

According to victims, their families, and prosecutors, another obstacle to justice is that many abuses by armed groups go unreported due to fear of reprisals.[226] As noted above, several relatives of disappeared people and sexual violence survivors whom we interviewed had not reported the crimes. And when cases are reported, pervasive fear of retaliation among witnesses, victims, and their families impedes cooperation with investigations. In many cases, victims tell prosecutors they want to take back their criminal complaints, a prosecutor and an official from the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office told Human Rights Watch, because they fear retaliation or have received threats.[227] While a prosecutor can continue a prosecution in the absence of a complaint, it is difficult to prosecute the crime if key witnesses or survivors are too afraid to cooperate with authorities.

Justice officials also face serious security risks in carrying out their work in Tumaco. On July 11, 2018, three CTI officials were shot dead on the road between Pasto and Tumaco. Their bodies and the truck they were driving were later burned.[228] The Attorney General’s Office blamed members of the Oliver Sinisterra Front. [229]

|