Summary

This woman shouted for ‘Kevin’ to come to the desk. I shrunk in my seat, hoping she would see the note on the chart about my gender change. But she just kept yelling for Kevin. I finally had to get up and cross the room in a walk of shame. Will I ever go back there? No way.

– Connie, 31, Miami, Florida

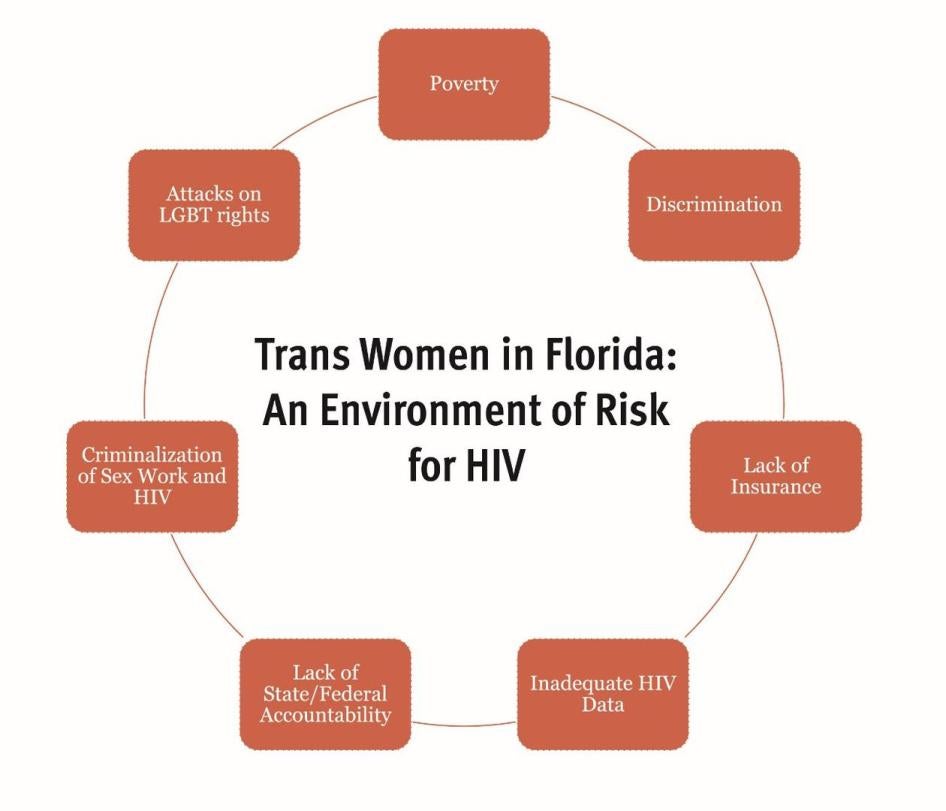

Connie is HIV-positive, one of many transgender women in Florida facing the challenge of finding health care that is safe, gender-affirming, and affordable. The 1.4 million transgender and gender-non-conforming people in the United States generally face multiple barriers, from family rejection to non-acceptance and abuse at school, and pervasive discrimination in employment, housing, and health care. Social and economic marginalization as a result of these factors lead to higher rates of suicide, poverty, violence, and incarceration, particularly for trans people of color. This is a severe and compound environment of risk for HIV that demands a robust response – one that the state of Florida, and the federal government, are failing to deliver.

Nationally, rates of HIV are declining as treatment becomes more effective and, if administered regularly, can eliminate the potential for transmission of the virus. Rates of HIV among transgender men appear to be low, though more study is needed. But among transgender women, rates of new HIV infection have remained at crisis levels for more than a decade. One of four trans women, and more than half of African-American trans women are living with HIV, rates that are far higher than the overall prevalence of HIV in the US of less than one percent. Transgender women are testing positive for HIV at rates higher than cisgender men or women, and racial disparities are stark: HIV prevalence is more than three times higher among African-American transgender women than their white or Latina counterparts.

Since 2010, the National HIV/AIDS Strategy has recognized trans women as a “key” population whose needs must be addressed. Trans people frequently experience disrespect, harassment, and denial of care in health care settings, and many avoid seeking health care as a result. HIV policymakers know what to do: ample evidence indicates that to be effective, health care services for trans individuals must be affordable, gender-affirming, and should be integrated with transition-related care. This is particularly important for HIV care. If forced to choose, trans women will frequently prioritize Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) over HIV care, making it essential to combine these services in a “one-stop shop.”

Numerous pilot programs across the country have demonstrated that providing integrated HIV care that engages and respects trans women is feasible and successful in reducing HIV risk and improving health outcomes. But this investigation of HIV prevention and care for trans women in south Florida found that trans women are navigating a difficult landscape that state and federal authorities have not done nearly enough to address. Services are fragmented, integrated care is limited, and cost and lack of insurance leave medical and mental health care out of reach. To the extent that such services exist, they are more a result of community demand and local advocacy efforts rather than federal or state policy, which contain no targeted requirements or standards to ensure that trans women are receiving the services they need.

The problem is not money. As a state with one of the country’s highest rates of HIV infection, Florida receives hundreds of millions of dollars from the Ryan White program, the federal government’s primary vehicle for funding HIV prevention and treatment services. The state HIV budget has increased more than 15 percent in the last three years. Nationwide and in Florida, more than half of people living with HIV receive care through a Ryan White funded program. Ryan White services are important for transgender women – when they stay in treatment in Ryan White programs, their health outcomes are significantly better than when they do not.

Despite a wide network of public and private providers in the metropolitan areas of Miami and Fort Lauderdale, only a handful of HIV clinics are consistently identified as providing what is recognized best practice, and to some experts, the standard of care, for transgender women. State HIV officials told Human Rights Watch that all Ryan White funded clinics “welcome” trans patients, but there was no systemic monitoring of the issue to determine whether this is the case, and evidence from the ground suggests otherwise. In fact, Human Rights Watch found that many transgender women experienced disrespect, harassment, and denial of services in health care settings, and that such experiences often result in avoidance of health care altogether.

The Ryan White program covers medications for patients under the AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP). The federal government sets core criteria, but states can also cover medications for needs and conditions related to HIV, such as mental health and hepatitis C medications. In 21 states, ADAP covers hormone replacement medications for the purpose of gender transition – an important part of ensuring that HIV care meets the health needs of transgender women. Florida is not one of these states, and federal policy does not require it to do so.

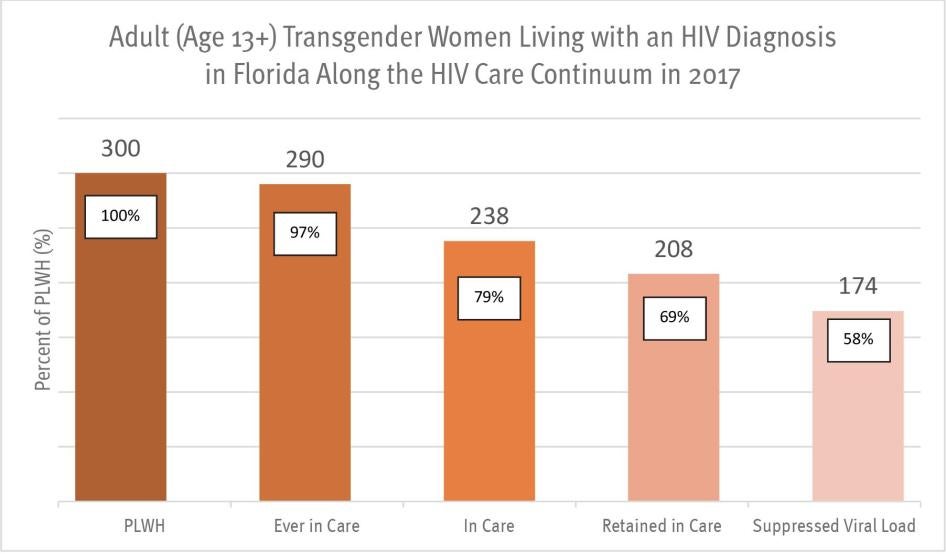

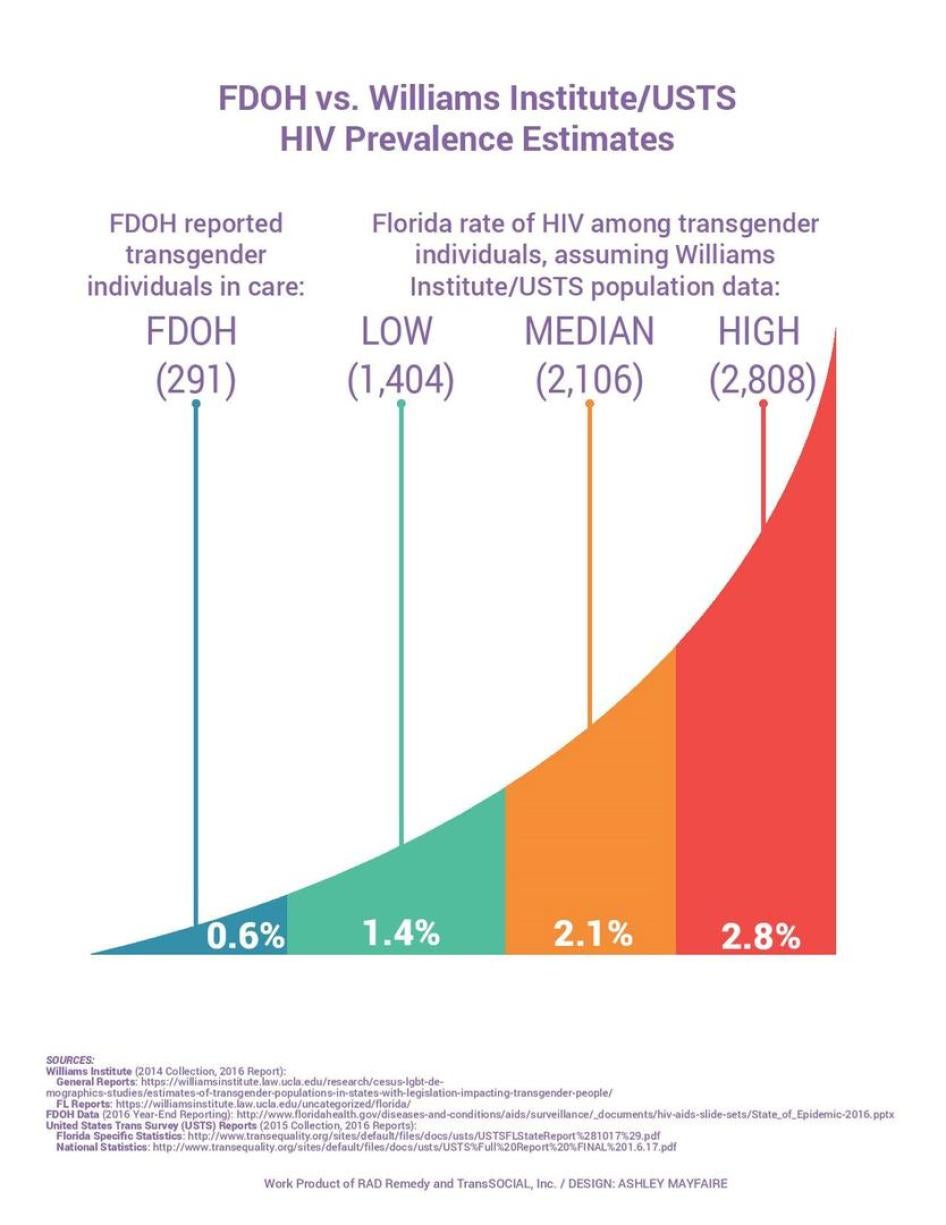

Underlying this lack of targeted government policy is the lack of accurate information about HIV risk and infection among trans women in Florida. The failure to collect accurate or complete HIV data among trans people is an ongoing problem. Decades into the epidemic, neither the state nor the federal government know how many trans women are living with HIV. Most states, including Florida, have only partially implemented federal recommendations for how to improve data collection for HIV among trans populations, and though Florida’s data on trans women is improving, they remain incomplete. Estimates developed from other experts indicate that the number of transgender people living with HIV in Florida may be five to ten times higher than reported by the state.

Given that government response is driven by data, the undercounting of HIV prevalence means trans women are left out of many federal and state programs intended to monitor or improve HIV services. Often perceived by policymakers as a population too small to help, conditions for trans women on the ground remain unknown, unchanged, or inadequate. Over thirty years into the epidemic, the stark reality is that trans women are at an extremely high risk of HIV, but as a distinct population remain largely invisible to the federal and state HIV surveillance and monitoring systems that guide government response.

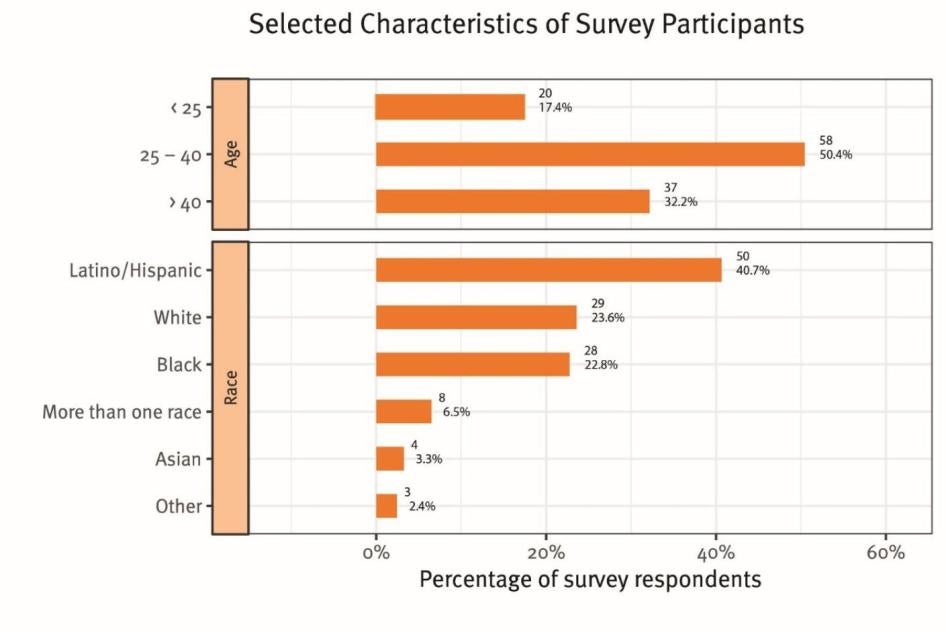

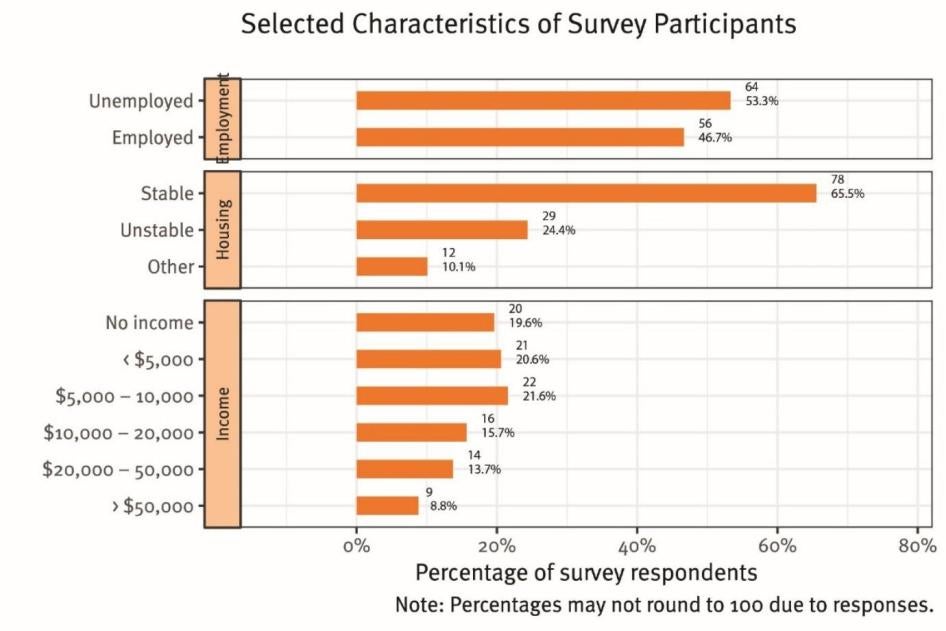

For this report, Human Rights Watch investigated access to health care, including HIV prevention and treatment, for women of trans experience in south Florida. We administered 125 survey questionnaires among trans women in Miami-Dade and Broward counties, two counties with the highest rates of new HIV infections in the country. These questionnaires, and the more than 100 interviews with trans women, their advocates, and HIV service providers indicated that many trans women in south Florida, particularly women of color, experience high HIV risk as a result of multiple factors, with poverty and lack of health insurance standing out as primary vulnerabilities. More than 63 percent of survey participants reported income of less than $10,000 per year, more than half were unemployed, and one of three were in “unstable” housing situations. This data is consistent with national surveys showing that many trans people live in extreme poverty and are three times more likely to be unemployed than those in the general population.

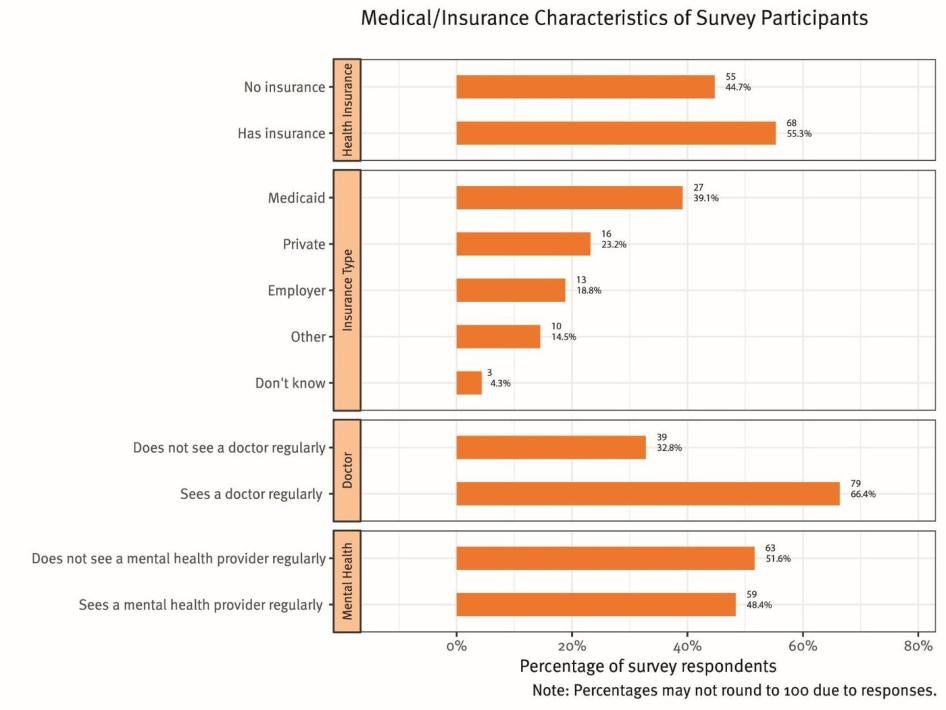

Nearly half of survey participants – 45 percent – had no health insurance. This alarming reality is tied to Florida’s refusal to expand its Medicaid program under the Affordable Care Act, a decision that has left hundreds of thousands of low income and working Floridians without access to health insurance. It is a decision that has a severe impact on transgender women, who are among the most impoverished residents of the state. Medicaid expansion could dramatically improve access to health care for trans individuals, many of whom would be included in its coverage of adults without dependents. Access to Medicaid could increase options for trans women as they attempt to locate gender-affirming health care in their community, providing vital access to HIV prevention and treatment.

Nationally, one of five trans women has been incarcerated, with African-American trans women three times more likely to face arrest than their white counterparts. Many trans women often turn to sex work in order to survive, leaving them vulnerable to police abuse and criminal charges that can begin, and perpetuate, a cycle of unemployment and lack of income. In the Human Rights Watch survey, more than half of respondents said they had been arrested at least once. Involvement in the criminal justice system increases HIV risk – even short jail stays have been shown to have negative health outcomes. Jails and prisons are also dangerous places for trans women, who report alarming rates of sexual assault in detention.

As trans women in Florida and throughout the US are struggling to access HIV prevention and care, the Trump administration has pressed forward with policies that will erode key LGBT rights protections and erect new barriers to their enjoyment of the right to health. The right to health does not guarantee to everyone a right to be healthy. Rather, its realization requires governments to implement policies that promote access to health care without discrimination, with particular attention to those facing the most barriers to care – low income persons, women, minorities, people with disabilities, and others.

Since Inauguration Day 2017, President Trump has moved in the opposite direction with a policy agenda that has sought repeal of the Affordable Care Act, restrictions on Medicaid access, and the rollback of regulations that protect LGBT Americans from discrimination. The rights of trans people are specifically threatened, with attempts to ban trans soldiers from the military, eliminate protections in federal law and policy that protect trans people from discrimination in employment and health care on the basis of gender identity, and weaken protections for transgender federal prisoners. For trans women, who face pervasive discrimination in employment and health care settings, the rollback of existing protections could have a particularly devastating impact.

In this increasingly hostile environment, trans women are in greater danger than ever and in greater need of federal and state support. For health officials, few questions remain about what to do to reduce HIV infection among trans women. But without commitment by both federal and state policymakers to take these steps and remain accountable for doing so, the lives and health of trans women will remain at risk, and the crisis will continue.

Recommendations

To the President of the United States:

- Re-establish federal leadership addressing the HIV epidemic in the United States, including appointment of a director and staff for the Office of National HIV/AIDS Strategy and making appointments to the President’s Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS comprised of public health experts, community leaders, and representatives of groups most heavily impacted by HIV, including trans women.

- Withdraw the executive order issued October 12, 2017 that permits unregulated health insurance plans inconsistent with the requirements of the Affordable Care Act.

- Withdraw the executive order issued May 4, 2017 instructing the Department of Health and Human Services to amend regulations for conscience-based objections to preventive care provisions of the Affordable Care Act.

To the Department of Health and Human Services:

- Protect and support expansion of the Medicaid program to ensure access to health care for low income people. Withdraw support for state waiver provisions that would reduce access to health services.

- Either defend the interpretation of section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act to protect against discrimination on the basis of gender identity, or introduce new legislation codifying those same protections.

- To the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA):

- Implement policy regulations and guidance to states ensuring the protection of LGBT individuals from discrimination in insurance coverage. This includes the revision of Medicaid regulations to address denials on the basis of perceived gender incongruity.

- Establish policies, monitoring, and evaluation procedures to promote gender-affirming care, including hormone replacement therapy, in all sites receiving Ryan White program funds, and support coverage of hormone replacement therapy in the AIDS Drug Assistance Program.

To the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention:

- Conduct a systematic review of implementation of the CDC Guidance for Working with Transgender HIV Data to ensure that states are taking effective steps to implement the Guidance and improve HIV data collection for trans communities.

- Identify states in need of technical assistance and prioritize provision of services accordingly.

- Report on steps taken and progress toward development of a national “indicator” for data collection on HIV among transgender communities as set forth in the National HIV/AIDS Strategy Update for 2020.

To the US Bureau of Prisons:

- Withdraw revisions to the Bureau of Prisons Transgender Offender Manual that weaken protections for transgender prisoners.

- Ensure that all regulations comply with Prison Rape Elimination Act requirements in order to reduce sexual assault in detention.

To the Congress of the United States:

- Stop attempts to repeal or further dismantle the Affordable Care Act without an adequate replacement.

- Support expansion of the Medicaid program to ensure access to health care for low income people.

- Pass legislation protecting LGBT persons from discrimination in health care, employment, and public accommodation.

- To the Senate: ratify the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights.

To the State of Florida:

- To the Governor of the State of Florida:

- Expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act to ensure access to health care for low income people including adults living in poverty with no dependents, and to reduce poverty in the state.

- To the Florida State Legislature:

- Repeal HIV-specific criminalization laws.

- Support criminal justice reform including alternatives to incarceration and decriminalization of consensual, adult sex work.

- To the Department of Health:

- Issue a public report on progress to date and timelines for implementation of CDC Guidance for Working with Transgender HIV Data.

- Establish policies, procedures, and monitoring systems to ensure that gender-affirming care is integrated with HIV care and services in all health care settings, including all sites receiving Ryan White funds.

- Participate in the federal ECHO program to evaluate and improve the quality of HIV services for transgender people.

- Ensure coverage for hormone replacement therapy in the AIDS Drug Assistance Program in all geographic areas and increase awareness of its availability.

- To the Office of Health Care Administration:

- Develop explicit policy ensuring Medicaid coverage for transgender health care.

Methodology

This report is based on research conducted between June 2017 and June 2018 in the south Florida counties of Miami-Dade and Broward. Human Rights Watch utilized a mixed-method approach that combined quantitative survey and qualitative interviews and legal and policy analysis. The research focuses on access to health care, including HIV prevention, for individuals who self-identified as women of trans experience – a term that was intended to reflect a variety of experiences and expressions – and that was left to the individual to define.

In addition to basic demographic information, the questions emphasized access to health care, including HIV care, access to HIV prevention, and interaction with the criminal justice system. Human Rights Watch identified respondents primarily through organizations providing social services to transgender people in the two counties and through the personal networks of peer interviewers. This approach produced a diverse group of respondents but should not be considered a representative sample of trans individuals in these counties, as survey participants were likely to be connected to health and HIV services.

For the quantitative component of the research, Human Rights Watch trained 15 peer interviewers in the administration of a survey, human rights documentation, and research ethics, including the importance of informed consent and confidentiality. Peer interviewers were diverse in age, gender identification, and ethnicity and were selected on the recommendation of, and in some cases were themselves representatives of, organizations providing services for transgender people in Miami-Dade and Broward counties. Of 125 questionnaires, 81 were administered by peer interviewers and 44 were administered directly by Human Rights Watch.

Survey participants were all Florida residents in Miami-Dade or Broward Counties who self-identified as women of trans experience; the survey tool made no inquiry into the definition of that term. The responses to the survey’s demographic options showed that 41 percent identified as Latina/Hispanic, 24 percent as White/Caucasian, 23 percent as Black/African-American, 4 percent as Asian and 7 percent as other or as “more than one race;” ages reported ranged between 19 and 70 (see Graph I).[1]

Peer interviewers were paid a nominal stipend for their training time and administration of the survey. Gift cards were provided to interviewees to reimburse them for travel and related expenses.

All participants were informed of the purpose of the survey, its voluntary nature, and the ways in which the information would be used. All participants provided oral consent to be interviewed and consent was noted on each survey form. Participants were assured Human Rights Watch would not publish their names; all names of survey participants reported are pseudonyms. Survey results were tabulated and analyzed by Human Rights Watch.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed more than 100 advocates, health care providers, public defenders, sheriff and jail officials, members of state HIV planning councils, federal health and criminal justice officials, and national experts on transgender health. The Florida Department of Health HIV/AIDS Section responded to written questions in writing and responded on behalf of Miami-Dade and Broward County departments of health; Broward County Department of Health officials also met with Human Rights Watch in person. Documents were obtained from the Florida Department of Health, Broward County Department of Health, Broward County Sheriff’s Office, and Hollywood, Florida Police Department. All documents cited are publicly available or on file with Human Rights Watch. Pseudonyms are used for anyone not interviewed in their official capacity to protect privacy and confidentiality.

Background

Discrimination, Abuse, and Health Risks Among Transgender People

In the United States, an estimated 1.4 million people (0.6 percent of the population) identify as transgender. Transgender or “trans” is an umbrella term intended to be inclusive of the full range of nuance and diversity of gender expression and identity among those who may not identify with the sex they were assigned at birth.[2] Trans women were assigned male sex at birth but identify as women; trans men were assigned female sex at birth but identify as men.

Trans and gender-non-conforming people tend to face barriers in multiple aspects of life, from family rejection to non-acceptance and abuse at school, and pervasive discrimination in employment, housing and health care. Social and economic marginalization as a result of these factors are linked to higher rates of suicide, poverty, and incarceration, particularly for trans people of color. According to a survey conducted in 2015 by the National Center for Transgender Equality (NCTE), trans people were more than twice as likely as the US population as a whole to live in poverty and three times as likely to be unemployed.[3] A staggering 40 percent of respondents had attempted suicide, compared to 1.6 percent in the US population.[4] Violence was a fact of everyday life, with nearly half reporting having been sexually assaulted at one point and one in ten reporting sexual assault within the last year.[5]

In the national survey, African-American and Latino/a trans respondents fared worse than their white counterparts nearly across the board, reporting lower income, less access to health care and health insurance, as well as higher rates of homelessness, employment discrimination, and incarceration.[6] Trans people of color were more likely than white trans people to report abuse by the police as well as victimization while in jail or prison.[7] This is consistent with data collected under the federal Prison Rape Elimination Act indicating that African-American and Latina trans women report sexual assault in detention at higher rates than white women.[8] Violence and hate crimes against trans people have increased in recent years, though accurate data is hindered by lack of reporting and misinformation regarding the gender identity of victims.[9] FBI data show that reported hate crimes against trans people increased by 44 percent between 2015 and 2016.[10] At least 21 trans individuals, mostly women of color, have been killed in 2018, five of them in Florida.[11]

Barriers to Health Care and Services

Trans people in the US face both socio-economic barriers and discrimination in access to health care and services. Trans people are less likely than the general population to have health insurance and more likely to rely on publicly funded insurance than private or employer-provided coverage.[12] The 2015 US Transgender Survey indicated that one of three trans people had needed to see a doctor in the last year but could not afford to do so.[13] Trans people face outright denial of services as well as harassment in health care settings. A 2017 national survey by the Center for American Progress found that one in three trans respondents said that they had been turned away by a medical provider on the basis of their gender identity; one in five reported being subject to harsh or abusive language in a health care setting; and one in three reported unwanted physical or sexual contact by a medical provider.[14] A common response to these conditions is avoidance of health care altogether – one national survey found that one in four trans people stopped seeking health care as a result of bad experiences in health care settings.[15]

Health Care for Transgender People

As do all people, transgender individuals have diverse physical and mental health concerns, some that are related to their trans experience and some that are not. Standards of care for medical and mental health providers to treat transgender patients have evolved significantly in the last decade. The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) takes care to distinguish gender non-conformity from the clinical diagnosis of gender dysphoria.[16] According to WPATH and the American Psychiatric Association, there is nothing inherently pathological about gender non-conformity; gender dysphoria is a mental health condition in which one is experiencing clinically significant distress or social/occupational impairment as a result of gender non-conformity.[17] This diagnosis remains controversial as it is perceived as stigmatizing and pathologizes distress which, in the view of many, originates largely from societal prejudice and discrimination.[18] However, the diagnosis remains relevant as a basis for medical and surgical interventions for transgender and gender non-conforming people who wish to pursue them, and in many cases, as a prerequisite for insurance coverage for these treatments.[19]

One principle that is widely accepted is that effective health care for trans people should be respectful, safe, and culturally appropriate – a large number of health experts, provider organizations, and transgender advocates have published detailed guidelines on how to provide “gender-affirming” services in health care settings.[20] Recommendations for best practices not only include clinical standards for care but emphasize the importance of respectful and knowledgeable staff interaction with patients – use of gender-affirming pronouns, avoiding assumptions about gender identity or expression, recognizing that a patient’s official identity documents may not match their gender expression, and other considerations.[21] Underpinning these practices is a recognition of the evidence that failure to implement gender-affirming services will result in avoidance of health care for transgender patients. As stated by the University of California at San Francisco Center for Excellence in Transgender Health Care (CETH), “Providing a safe, welcoming, and culturally appropriate clinic environment is essential to ensure that transgender people not only seek care but return for follow up.”[22]

An example of the importance of gender-affirming policies in health settings is provided by Connie, a 31-year-old trans woman living in Miami, Florida. Connie’s driver’s license does not yet reflect her transition to female, so in her first visit to a local health clinic she asked them to note her current name and gender identity on the chart. However, on her second visit she was in the waiting room with other patients, and she heard her birth name called out loudly to summon her to the reception desk. Connie recalled:

This woman shouted for ‘Kevin’ to come to the desk. I shrunk in my seat, hoping she would see the note on the chart about my gender change. But she just kept yelling for Kevin. I finally had to get up and cross the room in a walk of shame. Will I ever go back there? No way.[23]

Transgender Women and HIV

Data are scarce and incomplete but alarming — both globally and domestically, trans women are heavily burdened by the HIV epidemic. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), existing studies show that nearly one of five transgender women around the world are living with HIV – this is a prevalence rate of 19 percent, compared to a rate of 0.8 percent in the general global adult population.[24] Globally, transgender women are 49 times more likely to acquire HIV during their lifetime than the general population of reproductive age.[25] HIV prevalence among trans men appears to be much lower, but data remain limited and more research is needed (see text box). WHO and UNAIDS, the leading international agencies charged with addressing the HIV epidemic worldwide, have designated transgender women as a “key population” along with men who have sex with men, prisoners, people who inject drugs, and sex workers. Because HIV among people within these groups (and their intimate partners) account for 40-50 percent of the global HIV epidemic, WHO and UNAIDS have declared that “without addressing the needs of key populations, a sustainable response to HIV will not be achieved.”[26]

In the United States, the National HIV/AIDS Strategy also designates transgender women as a “high-risk” and “key” population as studies indicate an HIV prevalence ranging from 22 percent to as high as 56 percent among transgender women of color.[27] This is grossly disproportionate to the overall prevalence of HIV in the US, which is under one percent.[28] In a recent survey of nine million HIV tests nationwide, transgender women had the highest percentage of positive results of any gender category.[29] Racial disparities are stark: HIV prevalence is more than three times higher among African-American transgender women than their white or Latina counterparts.[30]

HIV in the United States

More than 1.1 million people in the US are living with HIV, and one in seven are unaware of their infection.[31] Over the past decade, the number of people living with HIV has increased as treatment has become more effective. For the first time in the history of the epidemic, the number of new infections has begun to decrease overall, but still remains high among specific populations.[32]

In recent years, treatment has become the cornerstone of both HIV prevention and care. Public health and HIV experts have increasingly emphasized the importance of early and universal access to anti-retroviral medication not only to improve individual outcomes, but to reduce the risk of transmission to others. The approach characterized as “Treatment as Prevention” has gained traction globally and in the US as research confirms that sufficient suppression of the virus through anti-retroviral therapy can effectively eliminate the risk of transmission from one person to another and in communities as a whole.[33] Key to the success of this approach is the ability of the person to become aware of their status and to sustain a lifetime course of anti-retroviral medication that must be taken on a daily basis.[34]

Increased access to treatment has reduced new infections nationwide, but rates of infection remain high among certain groups, including gay, bisexual, or other men who have sex with men; African-American men and women; Latino men and women; people who inject drugs; youth 13-24 years old; people in the southern United States; and transgender women.[35]

Race and Poverty

Many factors combine to place trans women, and particularly women of color, at high risk of HIV. In the United States, HIV has become a disease of social, economic, and racial exclusion. Trans women are disproportionately impacted by many of these forces of marginalization, facing what has been characterized by HIV experts as “multiple, concurrent HIV risks and underlying vulnerabilities.”[36]

In the US HIV epidemic, racial disparities are extreme, with African-Americans comprising 12 percent of the US population, but 44 percent of new HIV infections. Though new infections have decreased among Americans overall, they continue to increase among African-Americans.[37] Indeed, African-Americans comprise the highest percentage of people living with HIV, people becoming newly infected, and people living with AIDS.[38]

African-American people in the US are more likely to be poor than white people, and poverty is one of the primary drivers of the HIV epidemic.[39] In contrast to sub-Saharan Africa’s HIV epidemic affecting the entire population, HIV in the United States is concentrated in impoverished urban areas and small towns, with the highest concentration of people living with HIV and new HIV infections occurring in the US South.[40] In some impoverished areas of the US, HIV prevalence has been found to be higher than in many African countries where the HIV epidemic is severe.[41]

As noted above, many transgender people live in poverty – the 2015 US Transgender Survey indicated that nearly one in three had an income of less than $10,000 per year, with 55 percent living on less than $25,000 per year.[42] In their 2015 report, “Paying an Unfair Price: Financial Penalties for Being Transgender in America,” the Center for American Progress found that discrimination in school, employment, housing and health care, as well as an inability to obtain gender-affirming identity documentation, combined to force many transgender people into poverty and into underground economies such as sex work for daily survival.[43]

Sex Work and Incarceration

People who exchange sex for money or life necessities are at increased risk for HIV, a risk that impacts some trans women who engage in sex work. This risk results from not only a higher number of sexual partners but, in many cases, from environmental factors such as poverty, homelessness, and substance use – all factors that have been independently associated with HIV risk and poor health outcomes.[44] In addition, Human Rights Watch and others have documented increased HIV risk to sex workers from the harmful consequences of criminalization: police harassment, arrest, and incarceration have been found to be associated with higher HIV risk, less access to medical care, and impaired ability to manage HIV medications.[45] A criminal history after conviction on prostitution charges creates a significant barrier to employment that perpetuates poverty and the necessity of sex work in order to meet one’s basic needs.

Trans women experience high rates of incarceration, with one in five trans women reporting having been in jail or prison.[46] The rate of incarceration for African-American trans women is three times as high as it is for white trans women – some studies indicate that half of African-American trans women report a history of incarceration.[47] Incarceration creates numerous barriers to HIV prevention and care – condoms are not available in the majority of prisons and jails in the United States; access to HIV medications and treatment is often inadequate or in many jails, non-existent; and linkage to medical care upon re-entry is uneven at best.[48]

In addition to incarceration itself as an HIV risk factor, transgender women experience alarming rates of sexual assault in prison. According to federal Prison Rape Elimination Act data for 2015, more than one-third of incarcerated trans women reported assault by other prisoners or staff.[49] African-American and Latina trans women are more likely to be victims of assault in jail or prison than their white counterparts.[50] Most HIV-positive prisoners were HIV-positive prior to their incarceration. However, a lack of HIV prevention measures and failure to provide safe environments for trans prisoners – such as the widespread practice of placing trans women in male prison facilities — increases HIV risk in correctional settings.[51]

Mental Health Issues and HIV

Trans people report experiencing high rates of mental health conditions including anxiety, depression, and substance use disorders. Many report anxiety, depression, and trauma resulting from societal factors – including stigma, discrimination, harassment, violence, and other mistreatment based on their gender non-conformity.[52] While cautioning against assuming that all mental health issues are related to gender identity, transgender health experts have identified distress and trauma from familial and societal non-acceptance as key to understanding and treating trans individuals.[53] Many transgender people seek mental health services to help them cope with the effects of prolonged concealment of their gender identity and harms resulting from attempts to express this identity in hostile environments.[54]

Mental health issues have been correlated with increased risk of HIV and poorer outcomes once infected. Depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, sexual abuse, post-traumatic stress disorder, and substance use disorders all have been associated with higher risk of acquiring and transmitting HIV in men who have sex with men, youth, people who use drugs, and transgender women.[55] People living with HIV experience higher rates of anxiety, depression, and substance use disorders than people without HIV, with trans women reporting higher rates of anxiety and depression, and reporting lower quality of life, than other groups living with HIV.[56]

Anxiety, depression and other mental health issues reduce one’s ability to adhere to a daily regimen of anti-retroviral medications, a key determinant of maintaining one’s health and wellbeing while living with HIV. For this reason, access to mental health services is considered an integral component of HIV care.[57]

|

Transgender Men and Barriers to Health Care Trans men face many of the same barriers to health care as trans women: a shortage of gender-affirming health settings, lack of knowledgeable providers, and denials of insurance coverage for basic health services – pap smears, mammograms and other services – that are perceived as “gender incongruent.” Trans men are significantly more likely to live in poverty and to lack health insurance than cis-gender men.[58] Research on health issues for trans men, including HIV research, remains extremely limited. The prevalence of HIV among trans men appears to be significantly lower than that among trans women – ranging from one to three percent in most studies – but still higher than in the general US population.[59] Many trans men have sex with cis-gender men who identify as gay or bisexual, placing them at increased risk of HIV infection.[60] Engaging in sex work and the use of alcohol or drugs also increase HIV risk. However, HIV testing among trans men remains low.[61] For trans men, sex with cis-gender men can be a complex issue, especially for those who are navigating the gay and bisexual community for the first time. Diego Herrera is a staff member working on transgender programs at Sunserve, a non-profit organization serving the LGBT community in Broward County. He told Human Rights Watch that many trans men are secretive about engaging in sex with cis-gender men, making HIV screening and referrals to prevention or treatment services difficult. Lots of trans men are having sex with men, but they do not feel comfortable being open about it. The community is not that supportive of it. Some fear homophobia, and for others it contradicts the ‘masculine’ identity that they are working to develop. There are guys that I know that have a lot of sexual partners, some for money – they need PrEP and HIV testing but won’t do it.[62] In addition, many trans men having sex with men report preferring to get health services in settings that focus on men who have sex with men, but often feel excluded or unwelcome in these environments. This may contribute to lower HIV testing rates and lower access to condoms, lubricant, and other methods of HIV prevention among trans men than among cis-gender men.[63] To date, HIV risk among trans men has not been accurately assessed or prioritized by federal or state HIV policymakers. Inadequate data as well as barriers to health care, including lack of access to affordable, gender-affirming care and HIV prevention services jeopardize the health of trans men. |

Barriers to Access to Medical and Mental Health Care

Trans people generally face formidable barriers in accessing gender-affirming health care. For many trans women with HIV, medical and mental health services remain out of reach. A national survey published in 2016 by the Transgender Law Center’s Positively Trans Project examined the health needs and concerns of trans people living with HIV. The majority (84 percent) of respondents were women, and 41 percent of respondents had a history of incarceration in prison, jail, or immigration detention. Forty-three percent reported income of less than $12,000 per year.[64] The methodology of the survey skewed toward respondents who were likely to be connected with some type of health care rather than those who might be more isolated. Even so, 41 percent of respondents had not seen a doctor for six or more months following their HIV diagnosis.

The primary reason given for not seeing a doctor after their diagnosis was a previous or anticipated discrimination by a health care provider. Cost was also cited as a major factor in failing to access care. African-American and Latino/a respondents reported lower income and were less likely to have health insurance than white respondents. When asked to list their number one health concern, the top concern identified by more than 60 percent of respondents was a need for “gender-affirming and non-discriminatory health care.” The next-highest concerns were hormone therapy and mental health care, including trauma recovery. HIV care was fifth on the list of concerns.[65]

For trans women with HIV, the first priority in addressing their needs is to ensure access to health care that provides them with fundamental respect and dignity. In 2017, a nationwide group of HIV-positive transgender leaders convened by AIDS United issued recommendations for best practices in health care. These leaders stated, “Due to the disproportionate impact of HIV on transgender and gender expansive communities, it is critical that clinics and support services are welcoming, inclusive and competent in serving this population.”[66]

For trans people, services that support them in transition or maintenance of their gender identity are not optional aspects of health care – they are fundamental to affirming individual identity and meeting established standards of transgender health care. The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH), for example, includes as its core principles:

· Exhibit respect for patients with non-conforming gender identities

· Provide care that affirms patients’ gender identities and reduces gender dysphoria, when present

· Become knowledgeable about the health care needs of gender non-conforming people

· Match the treatment to the specific needs of patients, particularly their gender expression and their need for relief from gender dysphoria

· Seek patients’ informed consent before providing treatment[67]

Trans women frequently prioritize hormone replacement therapy over other health concerns.[68] For this reason, access to hormone therapy is of the utmost importance for trans women living with HIV.[69] Public health and HIV experts, experts in transgender HIV care and, most importantly, trans women living with HIV identify access to transition care, including HRT, as fundamental to effective HIV care for trans women. The Center for Excellence in Transgender Health recommends “bundling” HIV care with HRT and other health services sought by trans women.[70] The AIDS United statement emphasizes the importance of a “one-stop shop” where trans people can receive HIV care as well as comprehensive transgender-focused health services.[71] The WHO states that for transgender women living with HIV, “transition care was perceived as vital pre-requisite for subsequent health care” and recommends that governments prioritize gender-affirming care in developing their plans for addressing HIV in this key population.[72]

The availability of hormone replacement therapy is an essential component of the standard of care for transgender people, and HRT plays an important role in HIV prevention and treatment. As CETH states, “HIV and its treatment are not contraindications to hormone therapy. In fact, providing hormone therapy in the context of HIV care may improve engagement in and retention in care as well as decrease viral load and increase adherence.”[73] Hormone therapy reduces anxiety and depression, factors known to increase HIV risk as well as to interfere with adherence to HIV medications.[74] The National Association of State and Territorial AIDS Directors stated, “Medication adherence among transgender people is heavily dependent on the availability of gender-affirming health services and continued hormone therapy.”[75]

Evidence suggests that in addition to reducing anxiety and depression, access to HRT can be an important factor in reducing HIV-related risk behaviors for trans women. Transition therapy has been found to increase quality of life for trans people including improved employment prospects that may reduce the necessity to engage in sex work.[76] Moreover, for trans women, sex with men can provide gender validation.[77] Numerous studies among trans women indicate that HIV-related risk behaviors – including unprotected sex and sex work – are often related to what has been characterized as an “unmet need for gender affirmation.”[78] Some trans women describe taking risks to have sex with men in order to confirm femininity and affirm their identity as women. Women also describe the relief obtained by access to HRT and other gender-affirming services, either under medical supervision or from street hormones for those who could not access health care.[79] For trans individuals, ensuring access to hormone replacement therapy is an indispensable element of the standard of care for both HIV prevention and treatment.

Federal Policies Contribute to HIV Risk for Transgender Women

Throughout the course of the HIV epidemic, federal agencies have been slow to respond to issues of HIV among transgender people. In 2010 the first US National HIV/AIDS Strategy announced its vision:

The United States will become a place where new HIV infections are rare and when they do occur, every person regardless of age, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity or socio-economic circumstance, will have unfettered access to high-quality, life-extending care, free from stigma and discrimination.[80]

The Strategy established three primary goals: 1) reducing new HIV infections; 2) increasing access to care and optimizing health outcomes for people living with HIV; and 3) reducing health-related disparities. In 2015, the Office of National HIV/AIDS Policy released the National HIV/AIDS Strategy Updated to 2020, a document that reaffirms the vision of the original strategy and summarizes progress made toward the three goals using a group of 17 “indicators” for measurement of whether specific targets had been reached.[81] Overall, most people who stay in medical care are achieving viral suppression, but the failure to effectively link people to care after diagnosis and retain them in care for treatment adherence are recognized as key problem areas that are having a severe impact on continued high rates of HIV infection among certain groups. As a consequence, the Update identifies linkage to, and retention in, medical care as top priorities for agencies involved in the nation’s HIV response.[82]

The Strategy identified HIV among transgender women as a serious concern and acknowledged the problem of inadequate access to gender-affirming health care:

Transgender individuals are particularly challenged in finding providers who respect them and with whom they can have honest discussions about hormone use and other practices, and this results in lower satisfaction with their care providers, less trust and poorer health outcomes.[83]

Stating that “historically, efforts targeting this specific population have been minimal,” the 2010 Strategy identified transgender women, particularly women of color, as a “high-risk” population and urged that Congress and relevant federal agencies fund and implement targeted programs for prevention, treatment and support services.[84]

In this context, the needs of transgender women are addressed in numerous provisions of the Update, including a continuing recognition that the dearth of “culturally competent” care for transgender individuals that results in poor health outcomes and a call to establish a new “indicator” for improved data collection of HIV among the transgender population.[85]

But the reality is that despite ample, even overwhelming, evidence of the need to implement culturally competent care and how to do so effectively, implementation of these intentions on the ground is incomplete, fragmented and not incorporated into policy requirements, monitoring, or evaluation.

Some concrete steps were taken under the Obama administration to address trans health care and the alarming risk of HIV infection for trans women. Medicaid expansion was offered to states with the federal government footing most of the bill. The anti-discrimination protections in the Affordable Care Act were interpreted by the Department of Health and Human Services to include discrimination based on gender identity. The CDC issued technical guidance to states to improve their HIV data collection for trans populations and federally funded initiatives such as the Ryan White program, the nation’s largest source of funding for HIV care and services, began to utilize a two-step gender identification process for its clients.[86] But implementation was incomplete, new HIV infections among trans women continued to rise, and the Trump administration is taking numerous steps to undo progress in increasing access to health care.

For example, Medicaid coverage, essential to access to health care generally as well as to HIV prevention, is being undermined by the Trump administration and Congress in a variety of ways. Government respect for transgender rights, including the right to health, is moving in the wrong direction. The burdens faced by transgender women in nearly every aspect of life are occurring in an environment of federal policy that not only remains insufficiently protective of LGBT people’s rights but has also seen the rollback of many recent gains.

LGBT people are protected by a patchwork of laws and regulations that vary in scope and geography. There are no federal laws that explicitly protect persons from discrimination on the basis of either sexual orientation or gender identity. However, under the Obama administration, federal agencies issued a series of rules and regulations based on sexual orientation and gender identity to decrease discrimination in federally funded programs. The departments of Education, Justice, Housing and Urban Development, and Health and Human Services, among others, issued guidance or regulations clarifying that discrimination based on sexual orientation and/or gender identity is impermissible under federal law.[87]

Since 2017, the Trump administration has reversed many of those positions, withdrawing anti-discrimination protections and opposing inclusive interpretations of federal anti-discrimination laws in court.[88] Most recently, the administration has enacted two rules that significantly weaken anti-discrimination protections in federally funded health care activities and programs. These actions are likely to exacerbate health disparities for a population that is already significantly at risk. The first is proposed changes to the protections offered to LGBT people under the Affordable Care Act. Section 1557 prohibits discrimination in health care based on race, color, national origin, sex, age, or disability. In 2016, the Department of Health and Human Services issued a rule clarifying that discrimination based on “sex” includes discrimination based on gender identity and pregnancy status.[89]

The rule would have ensured that transgender people could not be denied care or coverage – including for transition-related services – because of their gender identity. However, shortly after the rule was introduced, eight states and religiously affiliated health care providers challenged it in court, and a federal judge in Texas enjoined it from taking effect.[90] Reversing the Obama administration’s decision to defend this interpretation in court, the Trump administration has indicated that it no longer considers section 1557 to protect against discrimination based on gender identity or pregnancy status.[91] Though the text of section 1557 has not changed, the administration’s re-interpretation of the rule has left transgender people without legal protection and signaled that federal agencies will no longer advance trans-inclusive interpretations of provisions prohibiting discrimination on the basis of sex. In October 2018, the New York Times reported that the administration is considering narrowing the definition of “sex” to male and female for all federal agencies, a move that could eliminate protection against discrimination for transgender and intersex people in employment, education, health care and other areas of life.[92]

The Department of Health and Human Services issued a proposed rule that would give sweeping discretion to providers to discriminate against LGBT people on the grounds of moral and religious belief.[93] The regulation would broaden existing protections for religious objectors by codifying vague, open-ended definitions that would invite discrimination against LGBT people, women and others.[94] In the absence of any provisions that would mitigate harm, these redefinitions risk greatly exacerbating discrimination and barriers to access women and LGBT people already experience. Other actions by the Trump administration include attempts to bar transgender persons from military service and weakening protections for transgender prisoners in the federal Bureau of Prisons. Passage of laws in numerous states that invite discrimination against LGBT persons in health care, adoption, and public accommodations combine with federal action to create a hostile environment that jeopardizes the health of transgender women.[95]

JoAnne Keatley, Director Emeritus of the UCSF Center for Excellence in Transgender Health, is concerned that any momentum for trans women with HIV that did exist will be lost as the Trump administration creates, what she calls, an environment that is “hostile to LGBT rights, but particularly hostile to transgender people.”[96]

In June 2018, the Trump administration released a report on the National HIV/AIDS Strategy indicating that on several key fronts progress had been made and reaffirming the commitment to end the nation’s HIV epidemic.[97] But, as noted by leading HIV advocacy organizations, the administration report did not acknowledge the major policy shifts that threaten continued progress, from attacks on Medicaid to the failure to appoint a director for the Office of National HIV/AIDS Strategy or members to the President’s Advisory Council in HIV/AIDS (PACHA). As noted in an AIDS United press release, “HIV policy does not occur in a vacuum.”[98] Cecilia Chung is a trans woman, national HIV policy advocate, and former member of PACHA. Chung told Human Rights Watch, “Without health care, and without respect for trans people’s rights, we will never end the HIV epidemic in this country.[99]

The federal response has produced some visibility for HIV risk among trans women as well as a patchwork of initiatives and grants. But the crucial issue of whether HIV care is integrated with trans health care and provided in a gender-affirming setting has not been translated into federal policy.

This policy void is most problematic in relation to the Ryan White HIV/AIDS program, a statutory program that since 1996 has provided the majority of national funding for medical care, medication and support services for people living with HIV.[100] Administered by HRSA and implemented by the states, Ryan White is a safety net program – eligibility for Ryan White programs, including the AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP) that helps pay for medications, is based on income and availability of health insurance. Ryan White patients must have an HIV diagnosis and income of less than 400 percent of the federal poverty level.[101] Ryan White is intended to be the provider of last resort – the program is available for those who have no insurance, but it can also supplement services that are left uncovered by insurance and, in the case of medications, help pay some premium costs and co-pays to ensure access to HIV medications.[102] Care and services offered through Ryan White funded programs are critical to the US HIV response: an estimated 52 percent of people living with HIV — 550,462 people in 2016 — utilize Ryan White. Ryan White patients have significantly better health outcomes, as these services have proven to be vital to their health; 85 percent of Ryan White patients have achieved viral suppression compared to 49 percent nationwide.[103]

The purpose of the Ryan White program is to ensure care for those who have no other options, and in states like Florida with limited access to Medicaid, the program is of lifesaving importance for trans women living with HIV. According to HRSA’s annual Ryan White report for 2016, there are 7,166 transgender clients in Ryan White programs nationwide, 355 of whom reside in Florida. Most are trans women (93 percent) and African-American (54 percent). An overwhelming majority live in extreme poverty: 78 percent live at or below the federal poverty level, earning less than $12,000 per year.[104] Though lower than for Ryan White clients overall, viral suppression rates for transgender clients are high (79 percent), much higher than the national average of viral suppression of 49 percent, illustrating the importance of the Ryan White program to transgender women living with HIV. Ryan White-funded clinics clearly help trans women once they enter and stay in the program – but as with other key groups impacted by the US HIV epidemic, there are troubling gaps in engagement and retention in care.

The necessity of gender-affirming care to engage and keep trans women in HIV care is well established, as is the feasibility of implementing this approach. In 2012, HRSA began funding a Special Project of National Significance (SPNS) project called the Transgender Women of Color Initiative (TWOC). TWOC was a demonstration project for improving HIV care at nine sites – both health facilities and community organizations. One of the primary elements of this project was the integration of trans-related health care, including HRT, with HIV care at several of the sites. None of the TWOC sites was in Florida, but for more than five years this project has demonstrated how a focus on providing gender-affirming care — from putting posters with images of trans people on the wall in a clinic to helping with documentation to ensuring availability of HRT — can improve HIV outcomes for trans women of color, and full results are expected to be published in fall of 2018.[105]

The quality of HIV care for trans individuals is included in one federal demonstration project, but participation by states and clinical providers is optional. HRSA is funding a project to offer technical assistance to state health departments and Ryan White-funded health care providers to improve the quality of HIV care to high-risk populations. The project, called the ECHO project, commenced in July 2018, and is designed to respond to requests for assistance from clinics whose data indicate health disparities for any of four groups, including transgender people. Transgender HIV experts will be available to consult on ways to increase trans engagement and retention in care. But whether entities will reach out for assistance with trans clients remains to be seen. According to one administrator for the HRSA ECHO program, response from providers is uncertain:

We are not sure that trans issues will be addressed. It is a time commitment to participate – ten hours of training a month, data reports monthly, consultant involvement – this is a lot of time for a very small population.[106]

Another HRSA-funded project commencing in 2018 will support 26 clinics around the US to implement evidence-based approaches to HIV care for high risk populations, including transgender people. Yet no policies or standards require federally funded HIV care to be provided in a gender-affirming setting and there is no systematic monitoring or evaluation of this issue by the federal government.

JoAnne Keatley has published extensively on the importance of integration of care and provided technical assistance for the TWOC project. According to Keatley, “Even before the TWOC project, we had the evidence we need – we know what to do to improve HIV outcomes for trans women. We have been working for decades to incorporate these findings into federal policy.”[107]

In the absence of federal standards or guidance, integration of HIV care with trans health care remains aspirational, limited, and incomplete in many states such as Florida. As discussed in detail below, Florida HIV officials provide funding to clinics that promote and offer gender-affirming care, but information from the ground indicates that they are also funding sites that do not. The AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP) provides HIV medications to those without health insurance, but in many states, including Florida, medications necessary for gender transition care are missing. Although millions of federal dollars are being administered, states implement Ryan White funding without policy guidance or compliance standards from the federal government for ensuring that gender-affirming care is implemented. According to Florida Department of Health HIV program officials:

After a thorough search we could find no HRSA or Ryan White regulations that addressed gender-affirming care for transgender women living with HIV.[108]

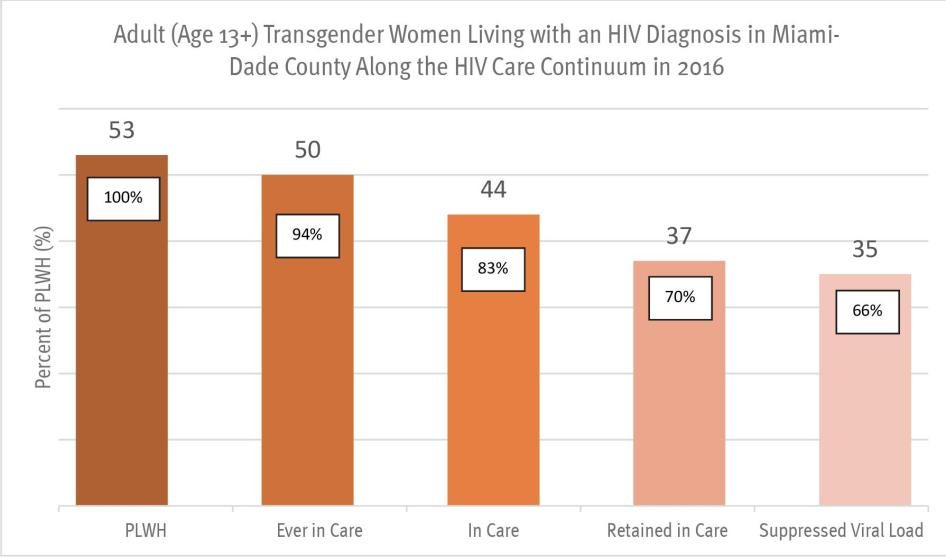

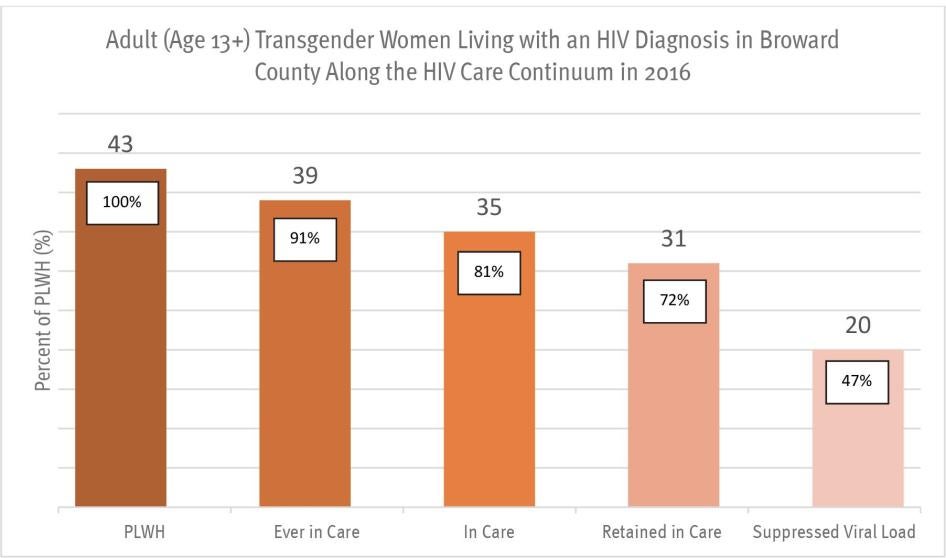

HIV in Florida

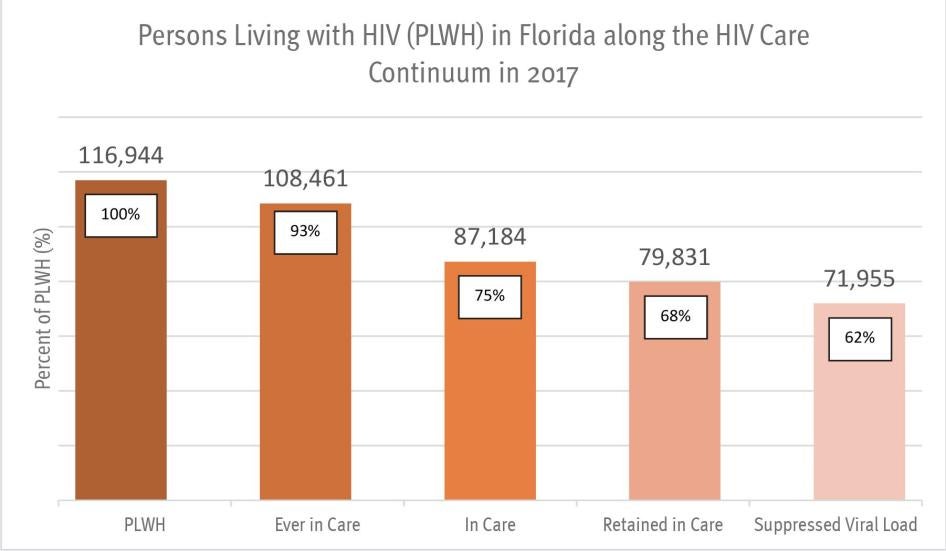

The state of Florida, along with the rest of the US south, lies at the center of the nation’s HIV epidemic. With more than 116,000 people known to be living with HIV, Florida accounts for 11 percent of HIV cases in the US.[109] Florida has the nation’s third highest rate of new HIV infections, and the epidemic is concentrated in urban areas of the state. The cities of Miami, Fort Lauderdale and West Palm Beach accounted for 47 percent of the state’s new HIV infections in 2016.[110] The rates of HIV infection in Miami-Dade and Broward counties are the highest in the nation. In 2017, the metropolitan areas that included Miami-Dade and Broward counties ranked first and second in the US in the rate of new HIV infections.[111]

Racial disparities are stark. In Florida, one in every 151 adults is known to be living with HIV; one in 295 whites, one in 49 African-Americans and one in 155 Hispanics.[112] African-Americans are 15 percent of the state’s population, but account for 42 percent of adult HIV infection cases and 50 percent of adult AIDS diagnoses. Hispanic people comprise 24 percent of Florida’s adult population but represent 31 percent of HIV infection cases and 24 percent of AIDS cases.[113] The rate of HIV infection in Florida is five times higher for Black men than white men, and 12 times higher for Black women than white.[114]

Florida surveillance data indicate that male-to-male sexual contact is the primary mode of transmission for both those living with HIV and new infections, followed by heterosexual contact and injection drug use.[115] As discussed in detail below, this data does not accurately reflect either cases or transmission modes among the transgender population.

State Response to HIV

In the US, the federal government is the primary source of funding for state HIV response, and the severity of the epidemic in Florida has resulted in what the statewide HIV Prevention and Care Plan calls “one of the nation’s most comprehensive programs for HIV/AIDS surveillance, education, prevention, counseling, testing, care, and treatment.”[116] In fiscal year 2017-2018, Florida’s HIV budget totaled nearly $300 million, mostly from federal sources. This budget has increased in the last three years by 15.6 percent. [117]

In Florida, lack of other insurance options has resulted in a significant reliance on Ryan White. One in five people in Florida is uninsured, the third-highest percentage in the nation.[118] More than half of people living with HIV in the state rely on care and services from the Ryan White Program.[119] Florida has a very restrictive Medicaid program and many people cannot afford to purchase private insurance, do not receive it from their employer, or are not eligible for federally subsidized insurance premiums under the Affordable Care Act. An estimated 384,000 people fall into this “coverage gap” in the state.[120] In Florida, the majority of Ryan White clients are African-American men, have incomes under 100 percent of the federal poverty level (less than $13,860 per year for an individual), and have no insurance.[121]

Florida’s extensive public HIV program has produced mixed results. Significant improvement has occurred over the last decade: Between 2008 and 2017, there was an 18 percent decline in HIV cases diagnosed, a 51 percent decline in AIDS cases diagnosed, and a 47 percent decline in HIV-related deaths.[122] Some recent trends are promising. Between 2014 and 2016, more Floridians with HIV entered medical care, remained in care, and became virally suppressed.[123] In the state ADAP program, 9 of 10 clients have achieved viral suppression.[124]

However, new infections have increased since 2013. Rates of new infection are highest among men who have sex with men (a category that erroneously includes many trans women), particularly young men of color.[125] The number of patients who fail to remain in treatment for HIV is concerning; of persons diagnosed with HIV, 92 percent are linked to care, but only 66 percent remain in care and 60 percent become virally suppressed.[126] Despite improvement in some areas, Florida is still struggling to bring its HIV epidemic under control.[127] In 2018, state HIV officials reported that many of the targets set in the previous year – including reducing new HIV infections, reducing new infections among African-American and Hispanic people, and reducing rates of infection among Hispanics – had not been met.[128]

Florida faces many challenges in effectively managing HIV. With 20 million people, it is the fourth most populous state in the US, a vast geographical area both urban and rural. Floridians are multi-ethnic (17 percent African-American and 24 percent Hispanic or Latino, according to 2017 census estimates) and there is a considerable transient population comprised of migrant workers as well as seasonal and part-time residents.[129] Its fiscal policy is conservative, with a constitution that prohibits state income taxes – the last tax increase occurred in 1988 and increased the sales tax by one percent.[130] Under Republican Governor Rick Scott, health and education budgets have experienced deep cuts.[131] In 2017, public health funding in Florida as a percentage of the budget ranked 40th in the nation; effective health care policy, comprised of factors such as percent uninsured, health spending, and vaccination coverage, ranked 46th among 50 states.[132]

In 2018, the legislature failed to pass a bill that would have permitted syringe exchange programs to operate statewide, leaving Miami-Dade as the only county with a syringe exchange program. Rejection by conservative legislators of proven public health and harm reduction approaches to injection drug use are problematic as the state, and the US, faces an unprecedented epidemic of drug overdose and increasing rates of HIV, hepatitis C, and other illnesses from injection drug use.[133]

The policy most detrimental to Florida’s ability to manage its HIV epidemic is the state’s failure to expand its Medicaid program. Under the Affordable Care Act, states have the option to expand eligibility guidelines for their Medicaid programs with payment largely covered by the federal government.[134] Florida is one of 18 states that have rejected this option despite Florida’s very restrictive Medicaid eligibility guidelines for its state program. Florida limits Medicaid eligibility both categorically (one must be disabled, parents of dependent children, a pregnant woman, or in need of long-term care) and income (for example, parents and caretakers’ income cannot be higher than 29 percent of the federal poverty level, or more than $7,380 per year).[135]

Medicaid expansion has benefited people living with HIV, primarily by ensuring coverage for a core group of comprehensive medical services without exclusion for pre-existing conditions.[136] In Medicaid expansion states, Medicaid coverage for people living with HIV rose 11 percent, with the most significant gains in coverage experienced by people with the lowest incomes and people of color.[137] Medicaid expansion has the potential to significantly mitigate HIV risk as well; expansion has been shown not only to increase access to comprehensive health services but to reduce poverty, a primary driver of HIV risk in the US.[138] Because Medicaid expansion regulations incorporate the anti-discrimination provisions of the Affordable Care Act, expansion is particularly important for LGBT people and other groups experiencing discrimination in health care.[139]

Broader eligibility under Medicaid expansion extends not only to working people with higher incomes, but to adults without dependent children. For Floridians, and for many trans women, this is a key factor as the Florida Medicaid program is limited to adults with dependent children, pregnant women or people with disabilities. In Florida, 87 percent of people who fall into the health insurance “coverage gap” as a result of failure to expand Medicaid are adults without dependent children, and 47 percent are people of color.[140]

Findings

For this report, Human Rights Watch administered 125 questionnaires to women of trans experience in Miami-Dade and Broward counties, gathering demographic information as well as information related to access to health care, including HIV prevention and treatment. The surveys and additional interviews with trans women, their advocates, HIV providers, and others indicated that many trans women in south Florida, particularly Latina and African-American women, live in an environment of high HIV risk as a result of multiple factors, with poverty and lack of health insurance standing out as primary vulnerabilities. Lack of income was associated with high rates of participation in sex work and with high rates of involvement with the criminal justice system – factors that increase HIV risk. These findings are consistent with other surveys of trans women in Florida, such as the one conducted by the 2015 US Transgender Survey, showing high rates of poverty and criminal justice involvement for trans women, particularly women of color.[141]

This severe and compound environment of risk for HIV demands a robust response from both state and federal government. There is ample evidence of how to provide effective health care, including HIV care, for trans women. But in south Florida, trans women face a fragmented landscape for health care that fails to ensure that effective, integrated HIV care is available at a cost that transgender women can afford. With no explicit or coordinated policies to ensure systematic monitoring and evaluation of HIV prevention or care for trans women, accountability is lacking. Policy development is hindered by lack of accurate or complete data regarding HIV among transgender women, a continuing problem that perpetuates a cycle of perceiving this at-risk population as “too small to help” at both the state and federal levels. Criminalization of sex work and HIV promote unemployment, poverty, and stigma that make access to health services more difficult. Few questions remain about what needs to be done, but without commitment by policymakers to do it, trans women will continue to experience grossly disproportionate disparities in access to health and HIV prevention and care.

Trans Women Face Barriers to Health Care in Florida

Trans women in Miami-Dade and Broward counties face multiple challenges that impact access to health care. As part of the research for this report, Human Rights Watch conducted a survey of 125 trans women with the assistance of local organizations and trans health advocates. The results below indicate severe socio-economic deprivation and a fragile existence for the majority of trans women interviewed.

The survey results reveal many trans women experience extreme poverty, with 63 percent of participants reporting income of less than $10,000 per year (20 percent of survey participants had no income; 21 percent reported income under $5,000 per year; 22 percent reported income between $5000 and $10,000 per year). More than half (53 percent) were unemployed. One third reported that their housing situation was “unstable” or “other” than stable (see Graph II).

These were not the most marginalized trans women living in areas with scarce resources. The survey was distributed through organizations providing services to trans women and participants were more likely to be connected to health care than in a more randomized sample. Also, the surveys were distributed in two major metropolitan areas with extensive health and HIV care infrastructure. Yet the results below indicate significant gaps in coverage and access to health insurance or care (see Graph III).

Of trans women surveyed, 45 percent had no health insurance. Of those that had health insurance, 39 percent had Medicaid and 23 percent reported having private insurance. Sixty-six percent see a doctor regularly (defined as twice a year or more) and 48 percent see a mental health provider regularly. Of those who did not see a doctor regularly, 38 percent said they could not afford it.

In detailed survey responses, many women described bad experiences with medical providers and their struggles to access gender-affirming care:

“Every time you walk into the doctor’s office, you become a science experiment.” – Ellen, age 44.[142]

“When I transitioned, my doctor wouldn’t see me after that. I couldn’t get in to see them. I had an infection and they wouldn’t call in the antibiotics. It was an ordeal. It was scary. I just felt bad about how they treated me.” Susan, age 22.[143]

“I used to go to Jackson hospital, but I haven’t been there in over a year. They are terrible. Not knowledgeable about trans health. They misgendered me. I don’t feel comfortable or trust them.” – Barbie, age 65.[144]

Many described cost and lack of insurance as the key factor in lack of health care:

“I made $450 a month and was working for ten years. Was denied Obamacare. Very hard to find insurance in Florida.” – Valerie, age 50.[145]

“I have diabetes. Hormones and diabetes medications cost $500 a month, I can’t afford that.” – Diana, age 54.[146]

Knowledge of where to get an HIV test was high, with 91 percent reporting that they knew where they could get tested. Nearly one quarter (23 percent) of survey participants reported that they were HIV-positive. To place this result in context, many surveys were distributed through agencies that provide referrals for HIV-related services. More than one in three (35 percent) trans women living with HIV had no health insurance. However, 88 percent of women living with HIV reported seeing a doctor regularly, and most were taking HIV medications (92 percent). With 77 percent of women living with HIV reporting that they had achieved an undetectable viral load, these results indicate the importance of the Ryan White safety net in states such as Florida, where many are without insurance and Medicaid has not been expanded.

Many of the women, including those living with HIV, described a difficult process for finding care that centered around safety and trust concerns.

Misty Eyez is a trans woman who works as an educator, trainer and case manager for trans women at Sunserve, an NGO in Broward County. Eyez described the fear of going to the doctor:

Many trans women are not comfortable leaving their house during the day. Therefore, going to the doctor can be an ordeal. For many reasons, some feel they have to put themselves totally together with the dress, the wig, the makeup in order to go out of the house, and then will they be safe in public, on the street, or on the bus? And how will they be treated when they get there? It is very lonely and isolating.[147]

Lack of Gender-Affirming Care Impedes HIV Response

For trans women, including those living with HIV, gender-affirming health care is not optional. Not all trans women want hormone replacement therapy (HRT), but for many it is central to their wellbeing and their number one health care priority. As Morgan Mayfaire, a trans man and co-director of TransSOCIAL, an advocacy organization for trans people living with HIV in Broward and Miami-Dade counties, told Human Rights Watch: “In this community, HRT is all. You will walk through a moat full of alligators to get your hormones.”[148]

This is true even for women living with HIV, which is one reason that HIV and trans health experts consider integration of HRT and HIV care to be critically important. The WHO, the Center for Excellence in Transgender Health at the University of California at San Francisco, the Fenway Institute, and others clearly identify integration of HRT and HIV care to be a best practice for HIV care for trans individuals.[149] The trans leaders convened by AIDS United emphasized the importance of a “one-stop shop” providing HRT and HIV treatment:

Due to financial hardship, housing instability, trauma due to a very real fear of violence in their lives, and distrust of medical personnel, trans people often fall out of care. If trans people are to successfully engage in and remain retained in care, clinical settings must design care that accounts for this reality. [As a best practice] Providers should consider establishing trans medical homes that address all health needs in a “one-stop shop” to retain and engage people in a consistent level of preventive and primary care.[150]

According to Dr. Madeline Deutsch, an expert in transgender health at the University of California at San Francisco, integration of HRT with HIV treatment should be considered not only a best practice, but the standard of care for trans people living with HIV:

Hormone therapy can increase engagement in care and increase adherence to anti-retroviral medication. It may not yet be considered a standard of care, but it should be. Not providing hormone therapy with HIV care is akin to providing HIV care in a Latina neighborhood without any Spanish speakers available.[151]

In south Florida, finding health care in a gender-affirming environment is difficult, and for trans people living with HIV the options are limited. Human Rights Watch interviewed trans women and their advocates, Ryan White providers, public health officials, and organizations in each county whose primary mission includes directing trans people either recently diagnosed with, or living with, HIV to appropriate medical services. These latter resources, many of which are small non-profit agencies, make it their priority to stay abreast of which clinics offer gender-affirming care, including HRT, to trans HIV patients so they can make effective referrals for care. It is a fluid situation that often depends on the presence of an individual trans-friendly or trans doctor, case manager, or another key employee. Based upon these sources, three to five clinics in each county were consistently identified as providing gender-affirming integrated HIV care to transgender people.