Summary

Oh Jung Hee is a former trader in her forties from Ryanggang province. She sold clothes to market stalls in Hyesan city and was involved in the distribution of textiles in her province. She said that up until she left the country in 2014, guards would regularly pass by the market to demand bribes, sometimes in the form of coerced sexual acts or intercourse. She told Human Rights Watch:

I was a victim many times … On the days they felt like it, market guards or police officials could ask me to follow them to an empty room outside the market, or some other place they’d pick. What can we do? They consider us [sex] toys … We [women] are at the mercy of men. Now, women cannot survive without having men with power near them.

She said she had no power to resist or report these abuses. She said it never occurred to her that anything could be done to stop these assaults except trying to avoid such situations by moving away or being quiet in order to not be noticed.

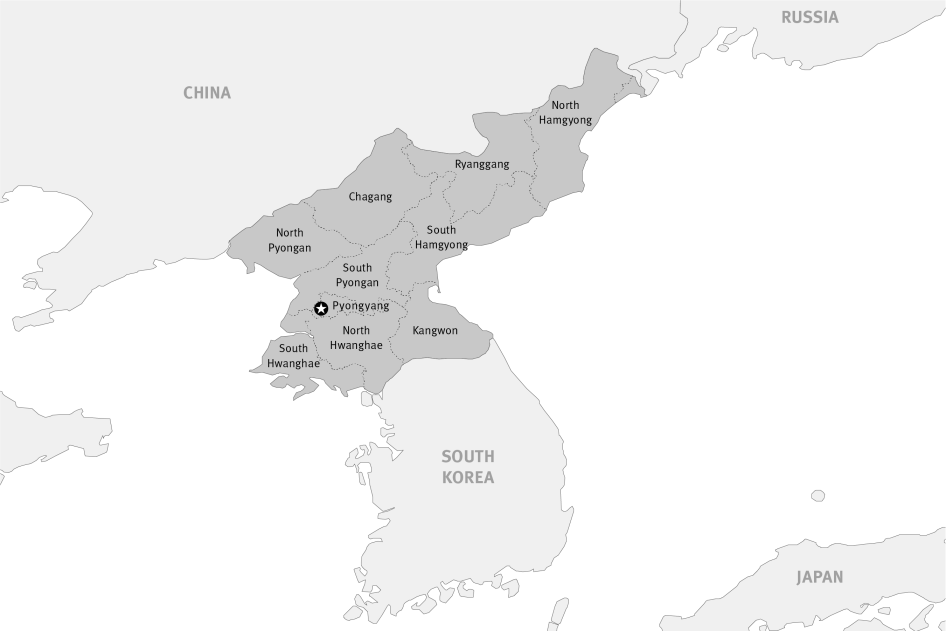

Park Young Hee, a former farmer in her forties also from Ryanggang province who left North Korea for the second time in 2011, was forced back to North Korea from China in the spring of 2010 after her first attempt to flee. She said, after being released by the secret police (bowiseong) and put under the jurisdiction of the police, the officer in charge of questioning her in the police pre-trial detention facility (kuryujang) near Musan city in North Hamgyong province touched her body underneath her clothes and penetrated her several times with his fingers. She said he asked her repeatedly about the sexual relations she had with the Chinese man to whom she had been sold to while in China. She told Human Rights Watch:

My life was in his hands, so I did everything he wanted and told him everything he asked. How could I do anything else? … Everything we do in North Korea can be considered illegal, so everything can depend on the perception or attitude of who is looking into your life.

Park Young Hee said she never told anybody about the abuse because she did not think it was unusual, and because she feared the authorities and did not believe anyone would help.

The experiences of Oh Jung Hee and Park Young Hee are not isolated ones. While sexual and gender-based violence is of concern everywhere, growing evidence suggests it is endemic in North Korea.

This report–based largely on interviews with 54 North Koreans who left the country after 2011, when the current leader, Kim Jong Un, rose to power, and 8 former North Korean officials who fled the country–focuses on sexual abuse by men in official positions of power. The perpetrators include high-ranking party officials, prison and detention facility guards and interrogators, police and secret police officials, prosecutors, and soldiers. At the time of the assaults, most of the victims were in the custody of authorities or were market traders who came across guards and other officials as they traveled to earn their livelihood.

Interviewees told us that when a guard or police officer “picks” a woman, she has no choice but to comply with any demands he makes, whether for sex, money, or other favors. Women in custody have little choice should they attempt to refuse or complain afterward, and risk sexual violence, longer periods in detention, beatings, forced labor, or increased scrutiny while conducting market activities.

Women not in custody risk losing their main source of income and jeopardizing their family’s survival, confiscation of goods and money, and increased scrutiny or punishment, including being sent to labor training facilities (rodong danryeondae) or ordinary-crimes prison camps (kyohwaso, literally reform through labor centers) for being involved in market activities. Other negative impacts include possibly losing access to prime trading locations, being fired or overlooked for jobs, being deprived of means of transportation or business opportunities, being deemed politically disloyal, being relocated to a remote area, and facing more physical or sexual violence.

The North Koreans we spoke with told us that unwanted sexual contact and violence is so common that it has come to be accepted as part of ordinary life: sexual abuse by officials, and the impunity they enjoy, is linked to larger patterns of sexual abuse and impunity in the country. The precise number of women and girls who experience sexual violence in North Korea, however, is unknown. Survivors rarely report cases, and the North Korean government rarely publishes data on any aspect of life in the country.

Our research, of necessity conducted among North Koreans who fled, does not provide a generalized sample from which to draw definitive conclusions about the prevalence of sexual abuse by officials. The diversity in age, geographic location, social class, and personal backgrounds of the survivors, combined with many consistencies in how they described their experiences, however, suggest that the patterns of sexual violence identified here are common across North Korea. Our findings also mirror those of other inquiries that have tried to discern the situation in this sealed-off authoritarian country.

A 2014 United Nations Commission of Inquiry (UN COI) on human rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) concluded that systematic, widespread, and gross human rights violations committed by the North Korean government constituted crimes against humanity. These included forced abortion, rape, and other sexual violence, as well as murder, imprisonment, enslavement, and torture on North Koreans in prison or detention. The UN COI stated that witnesses revealed that while “domestic violence is rife within DPRK society … violence against women is not limited to the home, and that it is common to see women being beaten and sexually assaulted in public.”

The Korea Institute for National Unification (KINU), a South Korean government think tank that specializes in research on North Korea, conducted a survey with 1,125 North Koreans (31.29 percent men and 68.71 percent women) who re-settled in South Korea between 2010 and 2014. The survey found that 37.7 percent of the respondents said sexual harassment and rape of inmates at detention facilities was “common,” including 15.9 percent that considered it “very common.” Thirty-three women said they were raped at detention and prison facilities, 51 said they witnessed rapes in such facilities, and 25 said they heard of such cases. The assailants identified by the respondents were police agents–45.6 percent; guards–17.7 percent; secret police (bowiseong) agents –13.9 percent; and fellow detainees–1.3 percent. The 2014 KINU survey found 48.6 percent of the respondents said that rape and sexual harassment against women in North Korea was “common.”

The North Koreans we spoke with stressed that women are socialized to feel powerless to demand accountability for sexual abuse and violence, and to feel ashamed when they are victims of abuse. They said the lack of rule of law and corresponding support systems for survivors leads most victims to remain silent–not seek justice and often not even talk about their experiences.

While most of our interviewees left North Korea between2011 and 2016, and many of the abuses date from a year or more before their departure, all available evidence suggests that the abuses and near-total impunity enjoyed by perpetrators continue to the present.

In July 2017, the North Korean government told the UN committee that monitors the implementation of the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) that just nine people in all of North Korea were convicted of rape in 2008, seven in 2011, and five in 2015. The government said that the numbers of male perpetrators convicted for the crime of forcing a woman who is his subordinate to have sexual intercourse was five in 2008, six in 2011, and three in 2015. While North Korean officials seem to think such ridiculously low numbers show the country to be a violence-free paradise, the numbers are a powerful indictment of their utter failure to address sexual violence in the country.

Sexual Abuse in Prisons and Detention Facilities

Human Rights Watch interviewed eight former detainees or prisoners who said they experienced a combination of verbal and sexual violence, harsh questioning, and humiliating treatment by investigators, detention facility personnel, or prison guards that belong to the police or the secret police (bowiseong).

Six interviewees had experienced sexual, verbal, and physical abuse in pre-trial detention and interrogation facilities (kuryujang)–jails designed to hold detainees during their initial interrogations, run by the MSS or the police. They said secret police or police agents in charge of their personal interrogation touched their faces and their bodies, including their breasts and hips, either through their clothes or by putting their hands inside their clothes.

Human Rights Watch also documented cases of two women who were sexually abused at a temporary holding facility (jipkyulso) while detainees were being transferred from interrogation facilities (kuryujang) to detention facilities in the detainees’ home districts.

Sexual Abuse of Women Engaged in Trade

Human Rights Watch interviewed four women traders who experienced sexual violence, including rape, assault, and sexual harassment, as well as verbal abuse and intimidation, by market gate-keeper officials. We also interviewed 17 women who were sexually abused or experienced unwanted sexual advances by police or other officials as they traveled for their work as traders. Although seeking income outside the command economy was illegal, women started working as traders during the mass famine of the 1990s as survival imperatives led many to ignore the strictures of North Korea’s command economy. Since many married women were not obliged to attend a government-established workplace, they became traders and soon the main breadwinners for their families. But pursuing income in public exposed them to violence.

Traders and former government officials told us that in North Korea traders are often compelled to pay bribes to officials and market regulators, but for women the “bribes” often include sexual abuse and violence, including rape. Perpetrators of abuses against women traders include high-ranking party officials, managers at state-owned enterprises, and gate-keeper officials at the markets and on roads and check-points, such as police, bowiseong agents, prosecutors, soldiers, and railroad inspectors on trains.

Women who had worked as traders described unwanted physical contact that included indiscriminately touching their bodies, grabbing their breasts and hips, trying to touch them underneath their skirts or pants, poking their cheeks, pulling their hair, or holding their bodies in their arms. The physical harassment was often accompanied by verbal abuse and intimidation. Women also said it was common for women to try to help protect each other by sharing information about such things, such as which house to avoid because it is rumored that the owner is a rapist or a child molester, which roads not to walk on alone at night, or which local high-ranking official most recently sexually preyed upon women.

Our research confirms a trend already identified in the UN COI report:

Officials are not only increasingly engaging in corruption in order to support their low or non-existent salaries, they are also exacting penalties and punishment in the form of sexual abuse and violence as there is no fear of punishment. As more women assume the responsibility for feeding their families due to the dire economic and food situation, more women are traversing through and lingering in public spaces, selling and transporting their goods.

The UN COI further found “the male dominated state, agents who police the marketplace, inspectors on trains, and soldiers are increasingly committing acts of sexual assault on women in public spaces” and “received reports of train guards frisking women and abusing young girls onboard.” This was described as “the male dominated state preying on the increasingly female-dominated market.”

Almost all of the women interviewed by Human Rights Watch with trading experience said the only way not to fall prey to extortion or sexual harassment while conducting market activities was to give up hopes of expanding one’s business and barely scrape by, be born to a powerful father with money and connections, marry a man with power, or become close to one.

Lack of Remedies

Only one of the survivors of sexual violence Human Rights Watch interviewed for this report said she had tried to report the sexual assault. The other women said they did not report it because they did not trust the police and did not believe police would be willing to take action. The women said the police do not consider sexual violence a serious crime and that it is almost inconceivable to even consider going to the police to report sexual abuse because of the possible repercussions. Family members or close friends who knew about their experience also cautioned women against going to the authorities.

Eight former government officials, including a former police officer, told Human Rights Watch that cases of sexual abuse or assault are reported to police only when there are witnesses and, even then, the reports invariably are made by third parties and not by the women themselves. Only seven of the North Korean women and men interviewed by Human Rights Watch were aware of cases in which police had investigated sexual violence and in all such cases the victims had been severely injured or killed.

All of the North Koreans who spoke to Human Rights Watch said the North Korean government does not provide any type of psycho-social support services for survivors of sexual violence and their families. To make matters worse, they said, the use of psychological or psychiatric services itself is highly stigmatized.

Two former North Korean doctors and a nurse who left after 2010 said there are no protocols for medical treatment and examination of victims of sexual violence to provide therapeutic care or secure medical evidence. They said there are no training programs for medical practitioners on sexual assault and said they never saw a rape victim go to the hospital to receive treatment.

Discrimination Against Women

Sex discrimination and subordination of women are pervasive in North Korean. Everyone in North Korea is subjected to a socio-political classification system, known as songbun, that grouped people from its creation into “loyal,” “wavering,” or “hostile” classes. But a woman’s classification also depends, in critical respects, on that of her male relatives, specifically her father and her father’s male relations and, upon marriage, that of her husband and his male relations. A woman’s position in society is lower than a man’s, and her reputation depends largely on maintaining an image of “sexual purity” and obeying the men in her family.

The government is dominated by men. According to statistics provided by the DPRK government to the UN, as of 2016 women made up just 20.2 percent of the deputies selected, 16.1 percent of divisional directors in government bodies, 11.9 percent of judges and lawyers, 4.9 percent of diplomats, and 16.5 per cent of the officials in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

On paper, the DPRK says that it is committed to gender equality and women and girl’s rights. The Criminal Code criminalizes rape of women, trafficking in persons, having sexual relations with women in a subordinate position, and child sexual abuse. The 2010 Law on the Protection and Promotion of the Rights of Women bans domestic violence. North Korea has also ratified five international human rights treaties, including ones that address women and girl’s rights and equality, such as the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and CEDAW.

During a meeting of a North Korean delegation with the CEDAW Committee, which reviewed North Korean compliance between 2002 and 2015, government officials argued all of the elements of CEDAW had been included in DPRK’s domestic laws. However, under questioning by the committee, the officials were unable to provide the definition of “discrimination against women” employed by the DPRK.

Park Kwang Ho, Councilor of the Central Court in the DPRK, stated that if a woman in a subordinate position was forced to engage in sexual relations for fear of losing her job or in exchange for preferential treatment, it was her choice as to whether or not she complied. Therefore, he argued, in such a situation the punishment for the perpetrator should be lighter. He later amended his statement to say that if she did not consent to having sexual relations, and was forced to do so, the perpetrator was committing rape and would be punished accordingly.

Key Recommendations

The Government of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK):

- Issue clear and binding public orders to all members of the government–including the police, the Ministry of State Security, the armed forces, judges, lawyers, managers at state-owned enterprises, and party officials–that rape and other acts of sexual violence be promptly and thoroughly investigated and prosecuted.

- Require the police to rigorously investigate and prosecute sexual violence cases, regardless of the position or status of the alleged perpetrators.

- Institute means to anonymously complain about sexual violence by government officials and collect statistics on complaints, anonymous or otherwise, as well as prosecutions and disciplinary actions as a result of complaints or investigations.

- Reform national laws to criminalize all forms of gender-based violence, including sexual assault, sexual abuse, rape, and marital rape, and ensure effective enforcement of those new provisions.

- Publicly acknowledge the pervasive problem of violence against women and girls in North Korea and launch a nationwide campaign to educate the public on the problem, emphasizing that all forms of such violence, including sexual and domestic violence and rape, are illegal and should be reported, investigated, and prosecuted.

- Gather credible data on the numbers of complaints, charges, investigations, prosecutions, and convictions in cases of sexual and gender-based violence, as well as sentencing data. Publicly release this data.

- Develop health and social services for survivors of sexual and gender-based violence, including counseling, medical assistance, and programs to help women to overcome stigma. Establish reproductive health and sexual education programs and basic education on core issues of non-discrimination and reduction of stigma against survivors of sexual violence.

To South Korea, the United States, Japan, the UK, the European Union, Other Concerned Governments, UN Agencies, and INGOs with a Presence in North Korea:

- Publicly and privately urge the government of the DPRK to undertake the reforms recommended in this report.

- Establish mandatory women’s rights and sexual and gender-based violence related trainings for all staff members who will be engaging in any activities with North Koreans to ensure that their engagement does not exacerbate existing gender bias that contributes to violence against women.

- Assist the North Korean government in developing policies and programs that aim to prevent violence against women, provide accountability for perpetrators, and assist survivors.

- Continue and expand support for reforms and services assisting survivors of sexual violence, especially funding for counseling, medical assistance, technical assistance regarding educational, legal and judiciary reform, and training of law enforcement agencies in North Korea.

Methodology

North Korea rarely publishes data on any aspect of life in the country. When it does, it is often limited, inconsistent, or otherwise of questionable utility. North Korea strictly limits foreigners’ access to the country and contact between local residents and foreigners, and does not, to our knowledge, allow independent human rights research of any kind in the country. Human Rights Watch did not conduct any interviews in North Korea for this report.

This report is based on interviews and research conducted by Human Rights Watch among North Koreans in South Korea and other countries in Asia, between January 2015 and July 2018, focusing on sexual violence against women in North Korea by state actors and the government response in such cases. Human Rights Watch interviewed a total of 106 North Koreans (72 women, 4 girls, and 30 men) outside the country. Among them, 57 North Koreans left the country after 2011, when North Korea’s current leader Kim Jong Un came to power.

All interviews were conducted in Korean by Human Rights Watch staff. All interviewees were advised of the purpose of the research and how the information would be used. They were advised of the voluntary nature of the interview and that they could refuse to be interviewed, refuse to answer any question, and terminate the interview at any point. Around half of interviews were recorded, with the interviewees’ consent, for later reference. All interviewees were given the choice to refuse having the interview recorded.

Human Rights Watch did not remunerate any interviewees for doing interviews. For those interviewees who had to miss their workday to make time for the interview, Human Rights Watch provided minimum wage compensation for their lost time. For those living far away from the venue of the interviews, Human Rights Watch covered transportation costs.

All participants verbally agreed to participate in the interviews before setting up the meetings and again at the start, and, as needed, during the interview. In all cases, interviews were conducted in surroundings chosen to enable interviewees to feel comfortable, relatively private, and secure.

In addition to individual interviews, Human Rights Watch conducted three group discussions–each time with two to four North Koreans living in South Korea, accompanied by sexual violence counsellors and/or experts with close relationships with North Korean interviewees. These informal gatherings aimed to gather background information on sexual violence in North Korea. These group settings aimed at creating a safe space for interviewees who were accompanied by people they trusted. These group discussions helped ensure quality control by providing helpful points of reference and factual cross-checks on the accounts of others interviewed separately. The participants were informed of the purpose of the discussion before agreeing to take part in the meeting. The meetings took place in private closed offices where the interviewees felt comfortable. The sessions were not recorded.

All of the survivors interviewed for this report expressed concern about possible repercussions for themselves or their family members in North Korea and asked to remain anonymous. To protect these individuals and families, all names used in this report are pseudonyms. Human Rights Watch also did not include in the report any personal details that could help identify victims and witnesses quoted in the report.

We also conducted interviews, on top of the 106 interviews with North Koreans, with experts familiar with issues concerning sexual and gender-based violence among North Koreans, health workers and counsellors, activists, NGO workers, legal experts, and academics. We also obtained and reviewed relevant documents available in the public domain from UN agencies, local NGOs in South Korea providing support to North Koreans, North Korean government agencies, researchers, and international analysts. These documents helped provide important insight into the context and background of sexual and gender-based violence against women in North Korea.

North Koreans who flee the country are almost always called “defectors” by North Koreans, South Koreans, foreign experts and observers, researchers, journalists, NGO workers, government officials, and so on. This report, however, refers to them simply as “North Koreans” or as “escapees”: the word “defector” presupposes a political motivation for leaving that may or may not be present. North Koreans leave their country for many reasons, including for economic and medical reasons.

Terminology In conducting research for this report, it became clear that the version of the Korean language used in the North lacks some of the vocabulary commonly used in the South, as well as in international discussions conducted in English on sexual and gender-based violence, domestic violence, and related subjects. Accordingly, when documenting abuses, we asked victims for direct factual explanations of what happened to them, avoiding labels, and have used their descriptions in recounting what they witnessed or experienced. When we use terms such as “rape” and “sexual violence” in the report, we are using definitions derived from international standards, as summarized below, and not direct translations of terms used in North Korea. North Korean People’s Understanding There is no precise equivalent in the version of the Korean language used in the North for “domestic violence.” The North Koreans we spoke with said the concept would have to be rendered as “men who hit their women.” They said that they understand the North Korean word for rape (ganggan) as unwanted vaginal penetration with a penis and accompanying physical violence, and that sexual violence that involved physical violence but does not involve penetration with a penis would have to be rendered as “violence with sexual connotations.” According to the North Koreans, sexual abuse or unwanted sexual advances without significant physical violence could be vaguely described as “situations with a sexual undertone when women feel uncomfortable or ashamed.” International Definitions In this report, Human Rights Watch uses the following definitions, which are derived from international standards: Sexual violence is “any sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act, unwanted sexual comments or advances, or acts to traffic, or otherwise directed, against a person’s sexuality using coercion, by any person regardless of their relationship to the victim, in any setting, including but not limited to home and work. Coercion can cover a whole spectrum of degrees of force. Apart from physical force, it may involve psychological intimidation, blackmail or other threats.” Sexual abuse, a subcategory of sexual violence, is “actual or threatened physical intrusion of a sexual nature, whether by force or under unequal or coercive conditions.” It includes rape, sexual assault, and sex or sexual activity with a minor. Sexual assault includes the use of physical or other force to obtain or attempt sexual penetration and rape. Rape is “penetration–even if slightly–of any body part of a person who does not consent with a sexual organ and/or the invasion of the genital or anal opening of a person who does not consent with any object or body part.” Sexual harassment is unwelcome “sexually determined behaviour in both horizontal and vertical relationships, including in employment (including the informal employment sector), education, receipt of goods and services, sporting activities, and property transactions;” including “(whether directly or by implication) physical conduct and advances; a demand or request for sexual favours; sexually coloured remarks; displaying sexually explicit pictures, posters or graffiti; and any other unwelcome physical, verbal or non-verbal conduct of a sexual nature.” |

I. Background

North Korea is one of the most repressive countries in the world. The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK, hereafter North Korea) is an authoritarian, militaristic, nationalist state, which describes itself as “socialist” and defines the country’s political system as a “dictatorship of the people’s democracy.”[1] The government is ruled by the Workers’ Party of Korea (WPK), with Supreme Leader Kim Jong Un holding the top position of chairman. All basic civil and political rights are severely restricted under the rule of Kim and his family’s political dynasty. There is no freedom of expression, association, or public assembly, and no independent civil society. Collective and public punishment are used to silence dissent among its 25 million citizens.[2]

In 2014, a United Nations Commission of Inquiry (UN COI) on human rights in the DPRK established that systematic, widespread, and gross human rights violations–such as murder, imprisonment, enslavement, and torture of North Koreans in prison and detention–committed by the North Korean government constituted crimes against humanity. The UN COI also documented that sexual and gender-based violence is prevalent in all areas of society, from home to work, public space, and in contact with government officials. It also documented some forms of sexual violence, including forced abortions, and rape committed against women in detention and prison, that amounted to crimes against humanity.[3]

According to the Supreme Leader (suryong) system that Kim Il Sung, the founder of the country and grandfather of the current leader, established in 1949, all powers of the state, party, and military are controlled by one unchallengeable leader, and in practice his male heir. The system is built on a guiding ideology that gives primacy to the statements and personal directives of the country’s leader;[4] then to the “Ten Principles of the Establishment of the Unitary Ideological System” of the WPK;[5] the rules of the WPK;[6] the Socialist Constitution;[7] and, finally, domestic laws.[8]

The legal system operates to protect the leadership and its political system, restraining fundamental rights and freedoms, and providing harsh punishment when challenges to these arise. Courts are not independent, and law enforcement generally does not serve the purpose of individual protection, so much as maintaining the political system and the social order it depends on.

Basic services, such as access to jobs, education, food, places of residence, and health care are parceled out depending on a socio-political classification system known as songbun, that grouped people from its creation into “loyal,” “wavering,” or “hostile” classes. The government uses songbun to discriminate among North Korean citizens based on how hard they work at school, in their jobs, or in society more generally, and their perceived political loyalty to the ruling party.[9] A woman’s classification depends on how hard she works or how well she studies, and her perceived political loyalty to the party, as well as the status of her father and her father’s male relatives and, once married, her husband and his male relatives.

All citizens are required to become members of, and participate in, the activities of mass associations that operate under the control and oversight of the WPK. Between ages 7 and 13, all children must become members of the Children’s Union. Their activities are overseen by members of the Kim Il Sung Socialist Youth League, which is made up of students between age 14 and their early 30s, when people may finish higher education degrees. After leaving school, a citizen becomes a member of a relevant mass organization, such as the General Federation of Korean Trade Unions, the Union of Agricultural Working People, or the Socialist Women’s Union of Korea (Women’s Union),[10] depending on employment and marital status. Party membership is the highest aspiration, which only about 15 percent of the population is able to attain. Party members also become officials of the mass associations controlled by the party.[11]

The government seeks to exercise effective control over every aspect of people’s daily lives through a vast surveillance apparatus consisting of a large network of secret informers, officials of mass organizations like the Women’s Union, and neighborhood watch systems (in Korean, inminban).

The inminban is made up of about 20-40 households with one leader appointed to report to the Ministry of People’s Security (in Korean, inmin boanseong, police, or MPS)[12] and/or the Ministry of State Security (in Korean, kukga anjeon bowiseong, often referred to as secret police, bowiseong, bowibu, or MSS) on unusual activities in the neighborhood, with the obligation to scrutinize intimate details of the family life of all residents. It also has the authority to visit homes at any time, even at night, to determine if there are unregistered guests or adulterous activities, and to report these to security organs for action.[13] The goal of this apparatus is to control every aspect of citizens’ lives, and monitor and act against any perceived anti-Communist, anti-state, or anti-revolutionary behavior.

Along with his cult of personality, Kim Il Sung established a doctrine of isolation and extreme nationalism, known as juche sasang,[14] which he promoted in conjunction with a focus on military readiness after the Korean War (1950-1953) ended in a ceasefire (it remains officially unresolved).[15] After Kim Il Sung’s death in 1994, Kim Jong Il elevated the position of the army in the government with the songun (military first) doctrine.[16]

According to figures submitted by the North Korean government to the UN, the government is dominated by men, with just 20.2 percent of female deputies selected in 2014 for the 13th Supreme People’s Assembly, the unicameral deliberative assembly in charge of making laws.[17] There are no women on the all-important National Defense Commission or the Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the WPK, which determines the party’s policies.[18]

Extreme Poverty and Modest Market Reforms

North Korea is one of the world’s poorest countries.[19] According to United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), in December 2017 an estimated 18 million people in the DPRK were experiencing food insecurity, while 200,000 children were acutely malnourished. One in three children under five years of age, and almost half of the children between 12 and 23 months, were anemic.[20]

After its creation in 1948, the DPRK instituted a command economy in which people were largely prohibited from engaging in private economic activities. In the 1950s, the government-created a Public Distribution System (PDS) operated with state supply centers that were supposed to provide food, clothes, and all daily necessities. But it failed to effectively deliver sufficient food to North Korea’s population for decades and was kept afloat by aid and food imports from the Soviet Union and China.

In the early 1990s North Korea faced a financial crisis when its main supporter, the Soviet Union, disintegrated. At the same time, North Korea’s already ill-equipped and mismanaged economy was hit by a series of floods and droughts. This provoked a great famine that killed a still-unknown number of North Koreans. Estimates of deaths from starvation and associated illnesses range from several hundred thousand to 2.5-3 million[21] between 1994 and 1998, the most acute phase of the crisis that the government referred to as the “Arduous March.”[22]

During the famine years, the government used ideological indoctrination to maintain the political system, and prioritized support for people they considered crucial for maintaining the political system and its leadership. That support often came at the expense of those the government deemed to be expendable.[23] The UN COI report concluded that “at the very least hundreds of thousands of innocent human beings perished due to massive breaches of international human rights law. Moreover, the suffering is not limited to those who died, but extends to the millions who survived. The hunger and malnutrition they experienced has resulted in long-lasting physical and psychological harm.”[24]

As China took over as North Korea’s main trading partner and benefactor in the mid-1990s, informal markets (jangmadang) emerged to fill the gap between supply and demand left by the collapsed PDS. These markets were born as illegal, underground “farmer’s markets,” where the major suppliers of food were farmers who privately grew grain and vegetables or raised stock animals outside cooperative farms, and traders who smuggled food from China. The central government allowed provincial governments to engage in food trading, which had previously been its exclusive domain, and largely turned a blind eye to private food trading by individuals.[25]

Although the government stopped providing regular wages and food distribution, it forced men and unmarried women to continue working at their state-owned workplaces, where salaries, if provided, were worth only between one to four kilograms of corn per month.[26] Since many married women were not obliged to attend a government-established workplace, they became the traders, and soon the main breadwinners for their families.[27]

Yoon Soon Ae, a former female trader in her 40s from Ryanggang province, who left North Korea in 2013, told Human Rights Watch:

We were used to being at home and getting everything from our husbands. But suddenly we had to figure out how to buy and sell things, and not to get caught, because everything we did could be considered illegal. It was very scary, but we had no choice, everybody had to rely on trade, a dirty and anti-Communist behavior, to survive.[28]

By July 2002, Kim Jong Il started experimenting with economic liberalization and North Korea officially announced economic reform measures, including legalizing some of the existing markets, adjusting commodity prices and wages, and ending subsidies to failing state enterprises.[29] Yet, the government remained concerned about its loss of control over the markets. In 2005, the government began to reverse the spontaneous liberalization of the markets that had occurred during the preceding decade because government leaders were uneasy with the markets, which they considered dangerous for political stability.[30]

First, the government banned men from selling goods at the markets, limiting such work to women 50 years or older, though enforcement depended on the willingness of local authorities to enforce the bans and the latest central government directives.[31] Younger women who were not allowed in the official markets had to find other ways to trade, and many of them engaged in distribution or inter-regional trade.[32]

Another blow to the markets came in 2009 when the government implemented a drastic de-monetization “reform” that triggered massive inflation and temporarily halted the functioning of the markets. In some cases, traders lost almost everything they had earned because the government had rendered much of the existing currency in the country invalid. Members of the public reacted negatively, making it harder for the government to continue to impose strict restrictions on the markets.[33]

Since 2010, the number of government-approved markets has doubled, reaching 404 by 2016. In that year, approximately 1.1 million people worked as retailers or managers in the markets.[34] Three former North Korean traders, who left North Korea in late 2014, told Human Rights Watch local party officials said they had received directives from Pyongyang in 2013 to stop cracking down on legal trading activities and to lift age restrictions in the marketplaces (jangmadang).[35]

At the same time, government employees and people in position of power at all levels realized there were opportunities within the new system to make money by demanding bribes. They increasingly began to seek bribes from those trying to conduct trade and market activities. Corruption quickly became commonplace, and the ability to receive bribes became an important source of income for many of those in power. According to Transparency International’s 2017 Corruption Perception Index, North Korea ranked 171 out of 180 on the list.[36]

Every North Korean interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that after the Great Famine of the mid-90s, official market gate-keepers started taking bribes from traders and anybody else hierarchically beneath them in the markets.[37] Soon corruption moved beyond the markets and spread into other sectors, with teachers taking money from students,[38] investigators and prison guards from detainees and prisoners,[39] and police across the board.[40] Bribes often had to be paid by junior soldiers to top army officers and WPK officials to obtain party membership.[41]

The UN COI reported that “officials are increasingly engaging in corruption in order to support their low or non-existent salaries.”[42] Some observers have remarked that such behavior amounts to “the increasingly male-dominated state preying on the increasingly female-dominated market.”[43]

II. Women, Society, and Law in North Korea

Women, who account for half the population, are a powerful driving force that pushes one side of the wheels of the cart of the revolution.[44]

–Kim Il Sung, quoted in Rodong Sinmun, North Korea’s official newspaper

Women and Society

According to the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK)’s second report submitted to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) Committee in April 2016, “women in the DPRK, under the wise leadership of the great Comrade Kim Jong Il and the supreme leader Comrade Kim Jong Un as full-fledged masters of the society, fully exercised equal rights with men in all fields of politics, the economy, and social and cultural life, performing great feats in the efforts for the prosperity of the country.” The government also trumpeted “remarkable achievements in the advancement of women and protection and promotion of their rights […] are the fruition born of the DPRK policy of attaching importance to and respecting women, and the patriotic enthusiasm and creative power displayed by women in the building of a thriving nation.”[45]

However, the report also claimed that between 2002 and 2015, the government publicly encouraged women to devote “themselves for the good of the society and collective, building harmonious family, and being exemplary in the upbringing and education of children.”[46]

Traditional Confucian patriarchal values remain deeply embedded in North Korea.[47] Confucianism is an ethical and philosophical system that is strictly hierarchical and values social harmony.[48] A woman’s position in society is lower than a man’s and her reputation depends largely on maintaining an image of “sexual purity,”[49] and on how well she obeys the men in her family.[50]

Traditionally in North Korea, marriage was not considered the union of two private individuals or the fulfillment of romantic sentiments or desires, but the union of two members of society fulfilling their social duty. For this reason, the ruling Workers’ Party of Korea (WPK) restricts any practices that it believed jeopardized the integrity, stability, and purity of this traditional family unit, including open expressions of sexuality.[51] The party also strictly restricts divorce, which it deemed a threat to the nation.[52] After the Great Famine, it became easier to obtain divorces, albeit more difficult for women and depending on one’s abilities to get connections and pay bribes.[53]

In Confucian times, after marriage, women were typically expected to move into their husband’s home, where they had to serve his extended family and were placed at the bottom of the family hierarchy until a first son was born.[54] While there is no longer any expectation for newly married women to move in with their in-laws, these gender roles remain largely intact, despite women’s growing role as economic actors. “Women who get married become blind for three years, deaf for three years, and dumb for three years,” said Paek Su Ryun, a former North Korean trader in her fifties who left in 2010, quoting a famous saying widely used in North Korea to indicate a newly married woman’s subordination to her husband’s family.[55]

According to Lee Chun Seok, a former North Korean school teacher in her forties from Ryanggang province, who left in 2013:

Men are the sky and women are the earth. What men think and say are what matters. We must absolutely obey men, respect them, and treat them with honor.[56]

Women and Girls at Home, School, and Work

Stereotyped gender roles begin in childhood. North Korean women, men, and children who spoke to Human Rights Watch said children grow up in an environment where discrimination against women and girls is constant and accepted. Girls learn they are not equal to boys and cannot resist mistreatment and abuse, and that they should feel shame if they become targets of abuse by men, whether in the home or in public spaces.[57]

North Korean students and teachers who left the country between 2010 and 2016, told Human Rights Watch that in mixed gender classes boys were almost always made leaders and that male teachers usually made decisions in schools, even when a majority of teachers in the school were women.[58]

Social structures and conventions that discriminate against women are also reflected in socially enforced rules of interaction between girls and boys. As teenagers, girls are often asked to use an honorific form when speaking to boys–although there is no reverse requirement. This practice continues through university, extending into the workplace, marriage, and family life.[59] Even according to the law, the minimum age for marriage is different, 18 for men and 17 for girls.[60]

The UN COI observed that women shoulder the responsibility of caring for the family and housework while continuing to be treated as second-class citizens and remain subservient to men at home and in society.[61] The UN COI report said that witnesses revealed that “domestic violence is rife within DPRK society.” It also found violence against women is not limited to private spheres like the home, but that men also beat and sexually assault women in public.[62]The UN COI also reported that “sexual and gender-based violence against women is prevalent throughout all areas of society. Victims are not afforded protection from the state, support services, or recourse to justice.”[63]

The Korea Institute for National Unification (KINU), a South Korean government think tank that specializes in research on North Korea, conducted a survey between 2010 and 2014 with 1,125 North Koreans who had re-settled in South Korea. The survey, based on interviews with 352 men and 773 women, found that 48.6 percent of the respondents said that rape and sexual harassment against women in North Korea was “common.”[64]

North Koreans who fled after 2011 said it is harder for women and girls than for men and boys to be admitted to and attend university,[65] join the military, and, by extension, become a member of the ruling WPK party, the gateway to any position of power in North Korea.[66] According to the 2016 DPRK country report to the CEDAW Committee, only about 20 percent of workers in government agencies are women. As of 2016, women made up 16.1 percent of divisional directors in government bodies, 11.9 percent of judges and lawyers, 4.9 percent of diplomats, and 16.5 per cent of the officials in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.[67]

Lack of Sexuality Education and Awareness of Gender-Based Violence

North Korean schools do not provide adequate education about sexuality and reproductive health. We spoke with 21 North Koreans with knowledge of school practices and all said while girls typically get information about menstruation, female hygiene, and pregnancy, the schools do not address sexuality and provide few, if any, details on how sexual organs or conception work.[68] Some noted that mixed biology classes sometimes include information about differences in animal genitalia and other body parts.[69]

There are no independent statistics on the prevalence of HIV/AIDS in North Korea and the government claims there are zero cases of AIDs in the country.[70] Human Rights Watch interviewed 30 North Korean people who left after 2011 about sexual violence and sexuality in North Korea, including sexually transmitted diseases. None of the interviewees had ever been taught how to have protected sexual relations, nor did they have any knowledge of how to prevent sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV. Two former doctors and one nurse said they had gained limited knowledge about sexually transmitted diseases while working in the DPRK.[71]

The version of the Korean language used in the North lacks specific vocabulary on sexual and gender-based violence, domestic violence, sexual abuse, assault, and harassment. The North Koreans we spoke with explained that family or domestic violence would have to be rendered as “men who hit their women,” and sexual violence that does not involve penetration with a penis as “violence with sexual connotations.”

They said that North Koreans understand the North Korean word for rape (ganggan) as unwanted vaginal penetration with a penis and accompanying physical violence. According to the North Koreans, sexual abuse or unwanted sexual advances without significant physical violence can be vaguely described as “situations with a sexual undertone when women feel uncomfortable or ashamed.”[72]

When the North Korean delegation met with the CEDAW Committee on November 8, 2017, Park Kwang Ho, a Councilor of the Central Court in the DPRK, insisted international standards had been integrated into national law–but then under questioning did not understand what “marital rape” was and asked the committee to explain it.[73]

Councilor Park also maintained that in the case of a woman in a subordinate position being forced to engage in sexual relations because she fears losing her job, or sees it as being required in exchange for preferential treatment, it was the woman’s choice whether to comply. He reasoned that in such cases the punishment for the perpetrator should be lighter because he did not use violence and the impact on the victim was less pronounced. He later amended his comments, saying that if a woman did not consent to having sexual relations and was forced to do so, the perpetrator was committing rape and would be punished accordingly.[74]

The social stigma and lack of knowledge or discussion of sexuality, gender, and sex that North Koreans we spoke with described, leave North Korean women and men unprepared for the realities of sexual activity. People know little about reproductive health, pregnancy, contraception, sexually transmitted diseases, or sexual crimes and seldom talk about these topics. Women are often unable to actively recognize themselves as victims of sexual violence, abuse, exploitation, or rape. Human Rights Watch documented two cases of women raped as young adults during the 1990s who said they did not fully understand what was happening to them.[75]

In the past two decades, information brought into North Korea via smuggled cell-phones and CDs (including pornographic movies) from China has increased.[76] One negative consequence is the increased depiction of women as sexual objects.

There appear to be significant differences in knowledge and viewpoints between people we interviewed from northern and southern provinces, urban and rural areas, and younger and older generations. Urban dwellers in their 20s from the capital in Pyongyang or from northern provinces (such as North Hamgyong and Ryanggang) tend to be more liberal in their views on sexuality than those born in the 1960s and 1970s or those from rural areas. Reasons for these more liberal views include more exposure to cross-border trade, information from the outside world, trafficking networks, and exposure to North Koreans who had spent time in China or other countries.[77]

Social Stigma and Victim Blaming

From an early age, North Koreans are taught stereotypical gender roles that condone violence against women. Victims of rape, domestic violence, sexual abuse, assault, or harassment are blamed for bringing it on upon themselves and made to feel ashamed.

Yoon Jong Hak, a former manager of a state-owned company from North Hamgyong province in his forties, who left North Korea in 2014, asked, “Why would a woman put herself in a position where she can be raped? I only let my wife work sitting at the marketplace, where I know people and she is fine.”[78]

Pervasive social stigma prompts victims to remain silent. “If a woman is raped, it is because she must have been flirting,” said Lee Chun Seok, a former teacher and trader in her late forties.[79] “I was ashamed and scared,” said the former trader Yoon Soon Ae, who was raped. “I never told anybody. In North Korea, it is like spitting in your own face. Everybody would have blamed me.”[80]

The UN COI report emphasized that violence against women, in particular sexual violence, was “difficult to document owing to the stigma and shame that still attaches to the victims” and concluded that its inquiry “may have only partially captured the extent of relevant violations.”[81]

The Role of China and the Experience of Women Forcibly Returned to North Korea

Women desperate to escape North Korea are profoundly vulnerable to deceit and exploitation by traffickers. In the last two decades, illegal networks to transport North Korean women to China have grown, with traffickers promising to assist women in traveling onward to South Korea or other countries, finding jobs in China, or locating Chinese men who will help them survive and send money back home.[82] Many women are trafficked for sale as “brides” or into the commercial sex trade, including through brothels and online sex chatting services.[83]

The Chinese government labels all North Koreans as “illegal economic migrants,” refusing to consider any as asylum seekers and often deporting them back to North Korea, despite the well-documented human rights violations they face there, which includes harsh interrogations, torture, poor detention conditions, and other punishments for having fled. The UN COI report found that people deported from China are typically detained and face extreme abuses in the detention centers.[84]

The UN COI report also found the North Korean government has committed crimes against humanity targeting people who were trying to flee the country, including rape and other forms of sexual violence.[85] The UN COI found “repatriated women who become pregnant while in China are subject to forced abortion.” It described a “climate of impunity that prevails in the interrogation detention facilities that process repatriated persons,” which “allows rape and other acts of sexual violence to be committed by individual guards and to go unpunished.”[86]

Women and Relevant Domestic and International Law

On paper, the DPRK is committed to gender equality and women’s rights. Even before its establishment in 1948, when the Soviet Union established a provisional People’s Committee for North Korea in 1946 with Kim Il Sung as chairman, Kim Il Sung’s provisional government enshrined women’s equality in domestic laws.

In subsequent decades, the government passed other laws protecting women, and ratified international human rights treaties, including the CEDAW in 2001. In 1990, North Korea ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), and followed by ratifying the Optional Protocol on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography in 2014 and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) in December 2016. The government also ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) in 1981.[87]

According to Kim Il Sung, “liberating women socially and realizing sex equality” were part of the “anti-imperialism and anti-feudal democratic revolution,” and were closely related to fulfilling tasks of a “higher level of revolution.”[88]

The Law on Sex Equality of 1946 extended to women equal rights in all spheres of society, provided them with welfare benefits, rights to inherit or share a property, and freedom to marry and divorce, and prohibited arranged marriages, polygamy, concubines, and the buying and selling of women. The law also established the Women’s Union, which operates under the WPK’s political control, to which all married women must belong. The Women’s Union has responsibility to advocate for women’s rights and encourage their social and economic participation and advancement.[89]

These changes translated into the promotion of women’s employment in collectivized enterprises. Most women started working in state-sponsored employment during the 1950s and 1960s, albeit generally with lower work status and salaries than men. The 1972 Socialist Constitution of the DPRK strengthened the legal basis for women’s equality and participation in society with article 77:[90]

Women are accorded an equal social status and rights with men. The State shall afford special protection to mothers and children by providing maternity leave, reduced working hours for mothers with many children, a wide network of maternity hospitals, creches and kindergartens, and other measures. The State shall provide all conditions for a woman to play a full role in society.[91]

In 1987, the government amended the Criminal Code to ban various forms of violence against women, such as rape, trafficking in persons, and sexual relations with girls or a woman in a subordinate relationship. Although a step forward, the definitions included in the amendments are deeply flawed (e.g., rape victims can only be women; consent is not a central consideration) and the punishments are inconsistent (e.g., mild punishment for child abuse).

The North Korean criminal code at present provides that a person[92] convicted of raping a woman using violence, intimidation, or a situation she cannot escape from can be sentenced to up to five years at an ordinary-crimes prison camp (kyohwaso, literally reform through labor center, sometimes also called re-education camps).[93] Those convicted of raping several women, causing undefined “serious harm,” or engaging in conduct resulting in the victim’s death can receive sentences of more than 10 years at the kyohwaso.[94]

Any person who has sexual relations with a woman in an undefined subordinate relationship (bokjong gwanggye, or literally “relationship of obedience”) may be imprisoned for up to one year at a short-term forced labor facility (rodong danryeondae, or labor training center).[95] A person may be imprisoned for up to three years at an ordinary crimes prison camp (kyohwaso)[96] for repeated offenses with several women, undefined “corruption of a woman” (tarak), or triggering her to commit suicide. Sex with underage girls (younger than 15 years) is punishable with up to one year’s imprisonment at a forced labor facility, and up to five years’ imprisonment at an ordinary-crimes prison camp for repeated cases.[97] According to an “addendum to the Criminal Code for ordinary crimes” adopted in December 2007, undefined “extremely grave” crimes of rape and kidnapping that violate socialist culture may receive up to the death penalty.[98]

The DPRK Criminal Code does not specifically prohibit domestic violence. However, the Law on the Protection and Promotion of the Rights of Women of December 2010 bans domestic violence and instructs municipal People’s Committees, institutions, corporate associations, and organizations to “adequately educate residents and employees against domestic violence.”[99] This law does not criminalize domestic violence or marital rape, however, and does not provide punishments for perpetrators.

The operation of law, in reality, is quite different from the law as it exists on paper: the DPRK criminal justice system routinely disregards the basic rights of women and girls. In practice, the constitution, laws, and other legal instruments are used to provide after-the-fact legitimization of ruling party directives, as in other one-party totalitarian systems.[100] As the UN COI report phrased it: “the law and the justice system serve to legitimize violations, there is a rule by law in the DPRK, but no rule of law, upheld by an independent and impartial judiciary. Even where relevant checks have been incorporated into statutes, these can be disregarded with impunity.”[101]

Even formally, North Korean laws are typically vague and do not adhere to international standards. They contain important omissions and lack clear definitions, leaving them open to interpretation and maximizing the discretion of government officials to decide how or indeed, whether to execute the law.[102]

For example, the crime of “rape” is undefined. The relevant provisions of the Criminal Code specify that only women and girls can be victims of rape but does not explain what elements must be present for an act to constitute “rape.” Other terms used but not defined in the law include “serious harm” or “corruption of a woman caused by the crime.” May 2012 amendments to the Criminal Code increased the maximum punishment for rape from 5 to 10 years in kyohwaso [103] and reduced the maximum prison terms for other sexual violence crimes.[104]

The provisions in the 2010 Law on the Protection and Promotion of the Rights of Women express general principles, use indeterminate language, omit definitions of key terms, and provide no guidance about which state agency is in charge of implementing the laws or what concrete actions must be taken and when.[105] There are also important gaps in enforcement and awareness of the laws.

None of the North Koreans we spoke with who had left the country after 2011 were not aware that the 2010 Law on the Protection and Promotion of the Rights of the Women even existed, much less knew of any instances of enforcement of this law.[106] And all of those we spoke with, including people who left the country earlier, emphasized that protections for gender equality enshrined in North Korean law have no bearing on women’s actual experience of inequality.[107] For example, Oh Jung Hee, a former North Korean trader from Ryanggang province, who left the country in 2014, said:

Women are one of the two wheels of the revolution … the government uses such revolutionary words in books or television. They say men must respect women, but that is not real outside of books or talks. The North Korea government says men and women are equal, but in reality, we just work harder, we have no protection, no real voice, and no power.[108]

III. Sexual Violence by Men in Positions of Power

Rape and Sexual Violence by Government Officials

Almost all of the North Korean escapees, including all eight former high ranking officials, we spoke to told us that if a man with power–a high-ranking party official, prison or detention facility guard, Ministry of People’s Security (boanseong, police, or MPS) officer, Ministry of State Security (bowiseong, bowibu, secret police, or MSS) officer, prosecutorial investigator, or soldier–“picks” a woman, she has no choice but to comply with any demands he makes, whether for sex, money, or other favors.[109]

Goh Myun Chul, a former high-ranking secret police agent, told Human Rights Watch that in the late 2000s he used to meet once a month with three or four of his bowibu colleagues at a hotel room in Pyongyang to drink and party.[110] He said:

At some point in the night, each of us picked our favorite actresses from films we watched and asked the hotel lobby staff to bring them to us. Whomever we chose would be at our room door within the hour. Nobody ever turned us down. Then, I thought it was natural they’d be happy we called them. We were powerful and influential, we paid them, and they knew that if we liked them they could call us if they got into trouble or needed a favor.[111]

Several other former government officials told Human Rights Watch that given the hierarchical structure of society, before making any approach North Korean men would consider whether the women they were interested in fell within their purview of influence or not.[112] Song Sang Hyun, a former teacher from North Hamgyong province who left at the end of 2014 and had close friends at the local government, said:

If government officials get close to women, they all have to be submissive to the men, but if it is somebody like me [without power] that tries to get close, they’d push me away and say I stink.[113]

Rape and Sexual Violence in Prisons or Detention Facilities

The 2010 to 2014 KINU survey of 1,125 North Koreans found 37.7 percent of the respondents said sexual harassment and rape of inmates at detention and prison facilities was “common,” including 15.9 percent who considered it “very common.” Among the respondents, 33 women said they were raped at detention facilities or prisons, 51 reported they witnessed rapes in such facilities, and 25 said they heard of such cases. The assailants identified by respondents were police officers (45.6 percent), guards (17.7 percent), secret police agents (13.9 percent), and fellow detainees (1.3 percent).[114]

The UN COI found that temporary detention centers routinely inflict sexual humiliation on repatriated women. Individual guards engage in verbal and physical sexual abuse, including rape, with impunity.[115] As a matter of standard practice, repatriated women entering temporary detention centers are forced to strip fully naked in front of other prisoners and guards. While nude, they are forced to perform a series of squats, ostensibly for the purpose of dislodging contraband hidden in their body cavities and genitals (a practice known as “pumping”). In line with established policies, women are also searched for contraband by female and sometimes male guards who insert their hands into the victim’s vagina, and sometimes their anus. These invasive body searches are conducted by ordinary guards using unsanitary techniques. Those who resist are beaten into submission.

It also found that the invasive body cavity searches performed in the DPRK’s detention centers for repatriated persons: 1) may amount to rape; 2) are illegal under the DPRK’s own laws; 3) are carried out in sexually humiliating overall circumstances; and 4) are not justified by legitimate concerns.[116]

Ordinary prison camp (kyohwaso) officials rape and inflict grave sexual violence on inmates. Although rape is formally prohibited in prison regulations, the UN COI found that “frequent incidences of rape form part of the overall pattern of crimes against humanity” in the camps and are a direct consequence of the impunity and unchecked power that prison guards and other officials enjoy.[117]

The UN COI found that rape is regularly committed in political prison camps (kwanliso, literally “control centers”) despite being formally prohibited, and only occasionally leads to disciplinary action.[118] It reported:

In some cases, female inmates are raped using physical force. In other cases, women are pressed into ‘consensual’ sexual relations to avoid harsh labor assignments, or to receive food. Such cases may also amount to rape as defined under international law, because the perpetrators take advantage of the coercive circumstances of the camp environment and the resulting vulnerability of the female inmates.[119]

Human Rights Watch interviewed eight former detainees or prisoners who experienced a combination of verbal and sexual violence, harsh questioning, and humiliating treatment by investigators, guards, police, and MSS agents in detention facilities between 2009 and 2013.[120] Six interviewees experienced sexual harassment and verbal and physical abuse in pre-trial detention and interrogation facilities (kuryujang), which are secret police (bowiseong) or police jails designed to hold detainees during their initial interrogations.[121] These facilities and local police stations (daegisil or gugumsil) are among the first detention facilities where detainees are usually taken.[122] Those repatriated from China may also be first sent to temporary holding centers (jipkyulso).[123] Interviewees said that secret police (bowiseong) or police agents in charge of their personal interrogation touched their faces and their bodies, including their breasts and hips, either through their clothes or by putting their hands inside their clothes. Human Rights Watch documented two cases of sexual assault at temporary holding facilities (jipkyulso), when women were being transferred from interrogation facilities (kuryujang) to detention facilities in the detainees’ home districts.

Case of Yoon Su Ryun

Yoon Su Ryun, a former smuggler in her thirties from Ryanggang province, left North Korea in 2014. She was smuggling herbal medicines to China in late 2011 when she got caught with a woman from Hyesan city, who was crossing the border at the same spot. The other woman was carrying opium. Yoon Su Ryun and the other woman both managed to escape the border guards, and Yoon Su Ryun, afraid they were searching for her, went into hiding.[124]

After 7 months in hiding, Yoon Su Ryun says she could not take it anymore and decided to turn herself into the authorities. She went to see the secret police (bowiseong) official in charge of her district and then went back home. Later, an agent of the police called her to the police station several times for questioning. In August 2012, the police detained her at a pre-trial detention facility (kuryujang) in her neighbourhood for three days, where she said a police officer raped her. Yoon Su Ryun, who took a counselling course for survivors of sexual and family violence after leaving North Korea, said:

They didn't allow food for me for three days. I was left alone in a dark room and nobody came to me or talked to me. On that day, a new officer came, and he raped me. He didn't say “I’m going to assault you,” he just took off his pants and jumped on me. I was alone and there was no place to escape, nowhere to run. It was a small room, just enough for five people to sit. I couldn't run away, and he was young. And I thought, “If I refuse this, what extra punishment would I have to get?” So, I just gave up ... I was in a hard situation. I was [sexually] assaulted and couldn’t do anything about it.

They can beat you up. Beating is nothing. If they don't like you, they can beat you up more easily than kicking a dog. But what I was most concerned about was my six-year-old daughter. I left her alone at home. I was at the pre-trial detention center of my neighborhood (dong), but if I were sent to the city detention center, I would have no one who could protect me. So, I just wanted to deal with it there and get out. I was so concerned about my daughter and she was alone at home. I didn't even cry at that time. I was just thinking that I should please him there and survive and go back to my daughter as soon as I could.

After raping me, the guard had my meals and clothes brought in. The head of my sector of the neighborhood watch (inminban), an old lady, had sent me food. I did smuggling to make a living, but I didn't commit any other crimes. I participated in all of the Inminban activities and the head of the Inminban was like a mother to me. She helped me a lot. So, she sent me at least one meal per day, but they didn't allow it.

My daughter still has trauma and gets scared when she hears a motorcycle. In North Korea, police officers ride a motorcycle. On the day I was arrested, the police officer came on a motorcycle. I told him that I would go to the detention center myself after calming my daughter a little. Since then, whenever she heard a motorcycle she said, “Mommy, hide! Here comes a police officer.”

I thought I was offering my body so that I could get out of there and go to my kid. At that time, I was not even upset. Rather, I even thought I was lucky. Now that I live here (in South Korea), (I know it’s)s sexual violence and rape.

Now that I think about it ... they wear uniforms and have the law on their side, the way they treat women should not be like [sexual] toys. North Korea has the term “rape” as well, but I didn't think what I experienced was a rape. Here, I came to learn that it was a rape. And it wasn't just me. I thought that's just what happens to female detainees.

Yoon Su Ryun said before speaking to Human Rights Watch she never told anybody about being raped. She said she was scared of rumors spreading about her. She also did not believe the authorities would be willing to help and feared possible retaliation from them.

Yoon Su Ryun also said that two experiences in her early twenties made her think the best option was to keep quiet. Around 2003 or 2004, she said an 18-year-old female student who lived in the neighborhood next to her grandparent’s home had gone to university but was suddenly expelled. Yoon Su Ryun said when the student returned home, people in the area started gossiping about her, saying she had been kicked out of university for sexual misbehavior. Soon after, Yoon Su Ryun’s grandfather told her that the student’s family said the university had expelled the student after she was raped. They told him a soldier had walked into a university dorm room, grabbed the student and raped her. Her roommates managed to run out and escape. The university blamed the student and expelled her. Yoon Su Ryun said:

[University] authorities cannot accept that rape can happen under their watch unless the victim ends up in a near death condition, so she is the one blamed…. She was ashamed and traumatized. Men looked down at her and wouldn’t go near her, so she couldn’t get married. Six years after the expulsion, her parents paid a lot of money to a man in the neighborhood to marry her. But he hit her and told her she was like a dog–less than an animal–in front of other people, including me. Later she went crazy–her parents took her back home and had to lock her in the house. Sometimes she’d escape and be naked outside near her house. The family suffered a lot. I was scared of her, but I was more scared of the gossip that destroyed her life.

In 2004, Yoon Su Ryun and 10 other women in their twenties were on duty guarding a Kim Il Sung revolutionary history research center. Authorities required them to do this every Thursday night from 5 p.m. until 6 a.m. Each woman would stand as sentry for an hour or two while the others slept inside and waited for their turn to guard.

She said that police officers would sometime pass nearby, making their rounds. One of the police officers would routinely go into the room where the women slept, insult them, and tell them to remove the blankets covering them. One Thursday, her cousin did not show up for the duty. Yoon Su Ryun’s mother later told her a police officer had abducted and raped her on her way to the center. Her aunt felt ashamed and did not tell anybody.

In July 2013, Yoon Su Ryun left North Korea and went to China where she got work picking blueberries. Chinese authorities detained her near Changbai mountain and forced her back to North Korea in December 2013. She was sent to a secret police (bowiseong) pre-trial detention facility (kuryujang) in Hyesan city, where a female bowiseong agent searched her anus and vagina, using a gloved finger. In the collective cell, there was a 23-year-old woman who also had been forcibly returned by Chinese authorities to North Korea. She told Yoon Su Ryun about being raped by a secret police (bowiseong) interrogator. She said:

The young woman came close to me and asked how they searched my body after arriving. I told her it had been a woman. [The 23-year-old cellmate] asked if it had not been a man. Then she cried. Later at night, the young woman sat next to me and told me a male bowibu agent told her to take off her clothes one by one, including her underwear. He searched her body. She didn’t have any money … while she was handcuffed, he hit her to scare her, and raped her. She cried. I thought of when I was violated, and I told her to calm down … and said that it was better to do anything the bowibu agent wanted and get his help to go home as soon as possible … I told her that was the best way, the way to continue with her life.

Case of Kim Eun A

Kim Eun A is a former prisoner from North Hamgyong province in her forties, who escaped to China from North Korea in 2015 and then made it to South Korea. She told Human Rights Watch that she had made an earlier unsuccessful attempt to flee and had been sexually assaulted after being forcibly returned from China in early 2012. Kim Eun A said that after she was returned, police held her at a pre-trial detention facility (kuryujang) near the North Korean-Chinese border in North Hamgyong province. The police investigator in charge of her case pressed a metal stick against her breasts and touched her face, arms, and pants around her groin.[125] She said:

He asked me if I had lived with a Chinese man, how it felt sleeping with him and more questions related to sex. Meanwhile, if I didn’t say what he wanted to hear, he’d hit me with a metal stick. He also pressed it against my breast or my face. Almost every time he questioned me, he touched my face, my arms, and grabbed my legs around the groin. At the time, I didn’t think there was anything wrong about it. I felt uncomfortable and I didn’t like it, but no other thoughts came up to my mind.

Kim Eun A said she also had a similar experience with her lawyer after being forcibly sent back by China to North Korea. Defense lawyers work for the government in North Korea. She says that just before her trial, her lawyer questioned her to prepare a document for her trial. She told Human Rights Watch:

During questioning, he asked questions and took notes with a fountain pen. Sometimes, he would stop and poke me with the pen or his hand in different spots on my body … like my arms or breast. He’d also hug me … I didn’t think about it, I didn’t like it and felt embarrassed and disgusted, but I couldn’t do anything.

She never told anybody because she didn’t think it was unusual. She said:

These types of abuse are so normalized by government officials, and any man with more power, that nobody can ever even imagine thinking of filing a case anywhere. The “law people” are themselves the perpetrators, so where could you go? Who is going to want to help when we [the victims] don’t even realize we are being abused? The idea that sexual violence is wrong, that it would not be my fault, that some “law person” could be there to try to protect me could have never even occurred to me while living in North Korea.

During her time in early 2012 at the police pre-trial detention facility (kuryujang) near the border area, Kim Eun A saw other women abused. She recalled: