Summary

On October 22, 2015, a car bomb exploded outside a Shia mosque in the town of Tuz Khurmatu, reportedly killing five people and wounding 40. The next day, at around 8 p.m., a car pulled up outside the home of “Aziz,” 32, a local laborer. According to Aziz’s wife, five men wearing black uniforms, masks, and the yellow logos of Kata’ib Hezbollah (an Iraqi Shia group that is part of the Popular Mobilization Forces), demanded that Aziz and his father “Sabah,” 70, “come with us.” Aziz’s wife has not seen them or received any information about their whereabouts since. “The next day, I went to the local police, the courthouse, and the intelligence office, but [they] all said they did not have any information,” she told Human Rights Watch in February 2018. “I am scared my husband will never come back, nor my father-in-law. How can I live without them?”

Aziz and Sabah, like thousands of other Iraqi men, were arbitrarily arrested and forcibly disappeared by government forces and allied local armed groups that have since been integrated as state forces as part of the fight against the Islamic State (also known as ISIS) that began in 2014.

Enforced disappearance is defined under international law as the arrest or detention of a person by state officials or by agents of the State or by persons or groups of persons acting with the authorization, support or acquiescence of the State, followed by a refusal to acknowledge the arrest or to reveal the person’s fate or whereabouts. The prohibition also entails a duty to investigate cases of alleged enforced disappearance and prosecute those responsible. In the cases documented by Human Rights Watch in this report, family members could obtain no information about the fate or whereabouts of the detainees and detainees were not allowed any contact with the outside world. Human Rights Watch also tried to obtain information on the whereabouts and well-being of those who had been arrested but received no response by the time of publication. The detentions can therefore be qualified as enforced disappearances.

The International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, which Iraq is a party to, codifies the prohibition on enforced disappearances and, among other things, sets out the obligations of states to prevent, investigate, and prosecute all cases of enforced disappearances.

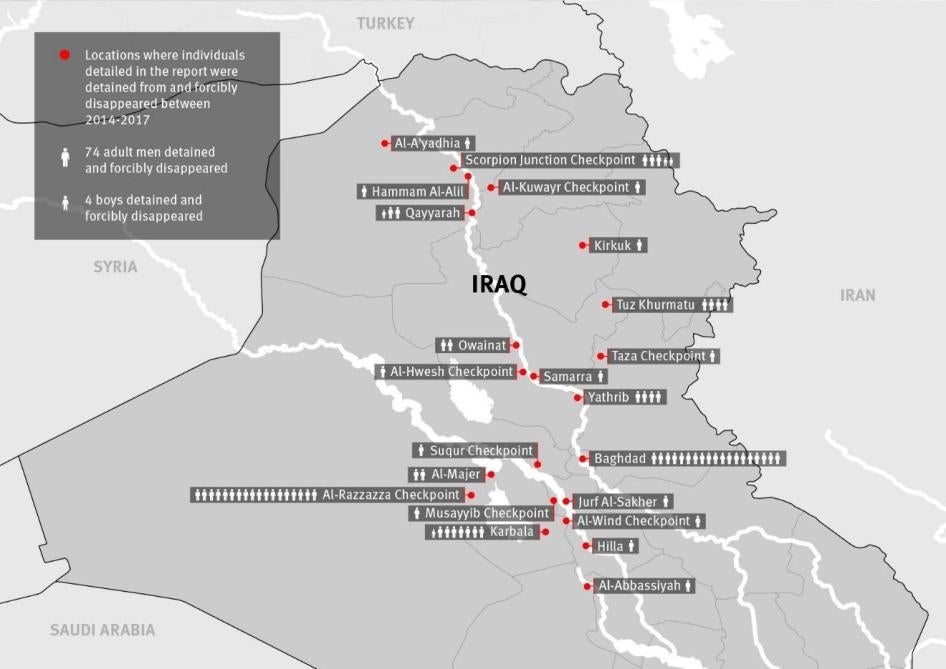

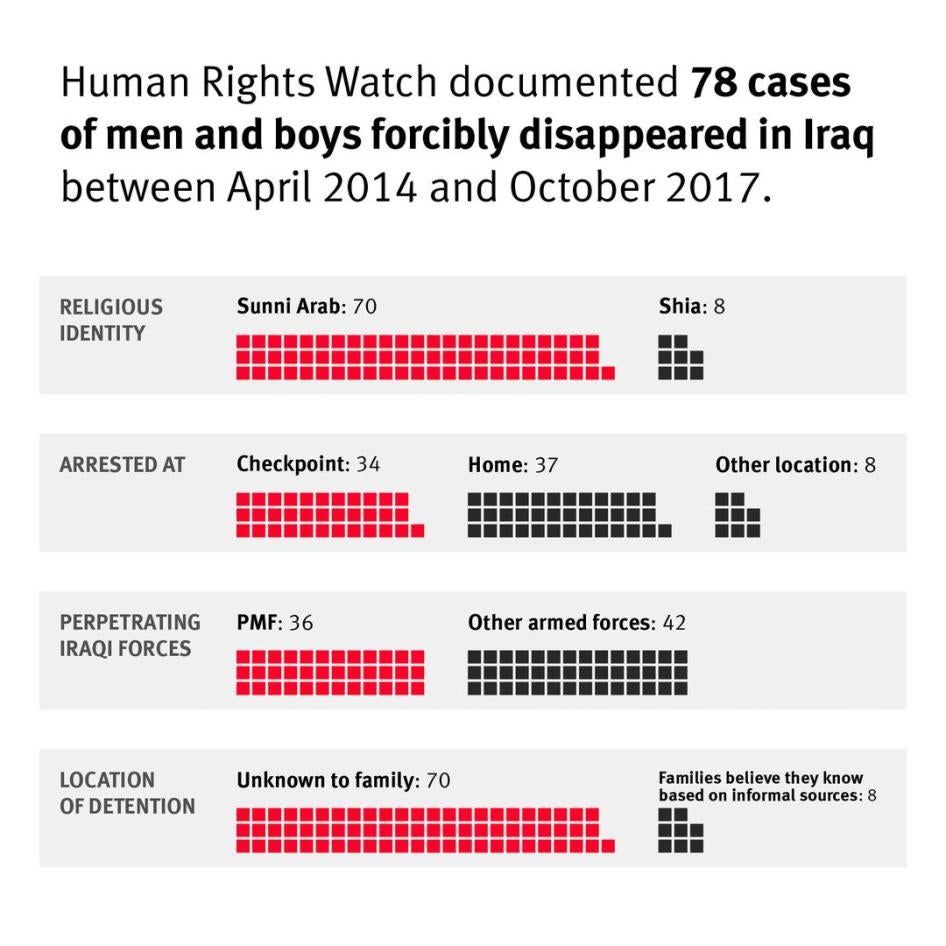

In this report, Human Rights Watch draws on research it has published on enforced disappearances in Iraq since 2014, and has documented an additional 74 cases of men and four cases of boys who were detained by Iraqi military and security forces between April 2014 and October 2017 and forcibly disappeared. While in four cases families believed they knew where their relatives were being held through informal sources of information, for the 74 other cases, their fate remains unknown. In 30 of these cases the individuals were detained in 2014, 22 in 2015, 14 in 2016 and 12 in 2017. In three additional cases, men who were detained and disappeared in 2014 and 2015 were released between 34 and 130 days later. Those released indicated that they had been detained by the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) or the National Security Service (NSS) in unofficial places of detention.

Almost all cases of individuals disappeared by security forces that Human Rights Watch has documented are male. Human Rights Watch has documented only one recent incident of a woman’s disappearance, in 2016.

With the exception of eight individuals who were disappeared during clashes between Iraqi forces and followers of the Shia cleric Mahmoud al-Sarkhi in 2014, all the cases Human Rights Watch documented for this report were Sunni Arab males. Their families all said that they believed the disappearances took place because of their religious, tribal or familial identity, which Iraqi forces used to impute a sympathy for ISIS and Al-Qaeda. Human Rights Watch is not aware of specific evidence linking the individuals disappeared to ISIS. The youngest disappeared victim was 9 years old, and the oldest 70, with the majority of the disappeared in their thirties.

Military and security forces apprehended 34 of the men and boys at checkpoints as part of terrorism screening procedures and another 37 from their homes. All of the disappearances at checkpoints but one targeted individuals who are from or lived in areas that were under ISIS control for varying periods of time between 2014 and 2017. Nineteen of the home arrests took place in Baghdad. In most of these cases, the security forces gave the families of those detained no reason for the arrests, although the families suspect they were related to their identity as Sunni Arab in combination with where they were from, or what family or tribe they belonged to. In at least six of these cases, the circumstances of arrest or what arresting officers said to the families indicated that they were likely or at least potentially related to the fight against ISIS.

In five home arrest cases, the arrests from homes took place following anti-ISIS military operations. In eleven cases, they took place as part of mass roundups and disappearances of individuals after major security incidents such as the 2014 fighting between the supporters of Mahmoud al-Sarkhi and security forces and the 2015 car-bombing in Tuz Khurmatu.

In another five cases, the Counter Terrorism Service (CTS), the Ministry of Interior’s Intelligence and Counter Terrorism Office, and PMF detained men from areas formerly under ISIS control in locations other than their homes and checkpoints. These locations include the Kirkuk courthouse, a displacement camp, Baghdad International Airport, and the Yathrib local police station. In another case, a Federal Police officer was arrested off the street in Samarra likely by the PMF. Another man was detained by a PMF member outside the Civil Directorate in Tuz Khurmatu. In each case the men were taken without explanation, according to witnesses to the arrest.

As is often the case with enforced disappearances, in a number of cases documented in this report, the enforced disappearance was accompanied by other human rights abuses including arbitrary arrest and detention; ill-treatment; and extrajudicial execution. Under international law, all suspects, including those linked to terrorism, are supposed to receive due process. These obligations require ensuring fairness and due process in investigations and prosecutions, as well as humane treatment of those in custody. Enforced disappearances may themselves amount to torture or inhuman or degrading treatment, both for the detainee and members of their family.

In the cases documented in this report, families of those arrested and witnesses of operations said that security officers did not present search or arrest warrants. In cases in which a reason for the arrest was given, it was always linked to terrorist allegations, typically to ISIS. None of the families Human Rights Watch interviewed knew whether their relatives had been brought before a judge in the allotted amount of time. Researchers observed that thousands of prisoners facing terrorism charges are held for months before they see a judge, during which time they are not allowed to communicate with legal counsel or with their relatives, nor do their families receive notification about their whereabouts.

Under Iraqi criminal procedure, which remains fully in force because the government has not invoked a state of emergency, police may detain suspects only after a court-issued arrest warrant and must bring suspects before an investigative judge within 24 hours in order to mandate their continued detention.

In three cases, family members who witnessed their relatives’ detention alleged that forces used excessive force, in one case leading to a death of another relative present during the apprehension process. In four other cases witnesses said security forces threatened the use of force.

At the time of arrest, in five instances authorities also seized phones, laptops, and in one instance a PlayStation. While Iraq’s counterterrorism law, provision 6(2) states that, “All funds, seized items, and accessories used in the criminal act or in preparation for its execution shall be confiscated,” the families in each instance said these items had not been used for terrorist purposes and that the arresting officers made no attempt to justify the seizures or return the items following an investigation.

Relatives of eight of the disappeared alleged that the PMF, NSS, and the Kurdistan Regional Government's Asayish (intelligence service), likely held their family members in unofficial places of detention, but said they did not know about how they were treated. However, three of the relatives who were detained themselves along with their disappeared relative but subsequently released all said they were physically abused by the PMF or NSS while in detention. None of these three men knew where exactly they had been held, none were charged or cleared for release through any legal process, and all were held incommunicado until their release.

These cases call into question the assertions by the PMF commission, the PMF’s governing body, that PMF groups do not detain any individuals in Iraq. They legally have no mandate to do so, the PMF commission has told Human Rights Watch. They may assist the judicial process in carrying out arrests, the commission has said, but then they should hand the individuals over as soon as possible to the relevant government forces who have a mandate to detain and interrogate.

Many relatives and witnesses have made allegations to Human Rights Watch of extortion linked to the release of prisoners, with officers demanding money from families to facilitate release. Amnesty International has documented cases in which families have paid exorbitant ransoms to armed forces in an attempt to secure their relatives’ release. In one case documented in this report, a father said an Asayish officer asked for a bribe in order to facilitate his son’s release. The father said he refused, saying he did not have the means, and his son has not been released since.

The most recent disappearances included in the report took place in October 2017. Between October 2017 and the time of publication, Human Rights Watch continued to receive reports of disappearances across Iraq. At the time of publication, the families of the disappeared whom Human Rights Watch interviewed for this report still had no information on the fate and whereabouts of their disappeared relatives.

The enforced disappearances documented in this report were conducted by a range of military and security actors. Human Rights Watch documented five by the CTS, Iraq’s elite counterterrorism special forces established by US-led coalition forces after 2003, and 12 by the NSS, a body dedicated to collecting information about armed, political, or religious groups threatening Iraq’s national security and monitoring international organizations and actors in country. Both the CTS and the NSS report to the prime minister. In some cases, the NSS carried out disappearances in conjunction with SWAT (Special Weapons And Tactics), a unit within the Ministry of Interior.

Human Rights Watch documented 14 cases in which units known as the prime minister's forces perpetrated enforced disappearances in Baghdad in 2014, all while former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki was still in office. Thirteen of those cases took place on April 21, 2014, nine days before Iraq’s scheduled parliamentary elections, in two Baghdad neighborhoods.

Researchers documented four cases in which the Ministry of Interior’s Intelligence and Counter Terrorism Office was responsible for disappearances and one case in which the Federal Police were responsible. The Federal Police, also under the command of the minister of interior, functions like many countries’ national guard or reserve forces. It was created to respond to domestic conflicts requiring a military deployment beyond the capacity of local police, whilst avoiding the political difficulties raised by deploying the army domestically.

The highest number of disappearances documented by Human Rights Watch, 36 cases, was perpetrated by different groups within the PMF. The PMF brought together many pro-government forces under the single banner after ISIS took control of Mosul in June 2014 after former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki and Iraq's supreme Shia religious cleric, Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Husseini al-Sistani, called for men to join the fight against ISIS. In February 2016, Prime Minister al-Abadi issued Order 91, officially incorporating the PMF as an “independent military formation” within Iraq’s security forces under the prime minister’s command. On November 26, Iraq’s parliament passed a law formalizing the decision. Until then, PMF groups operated extra-legally but with the support and acquiescence of the Iraqi government. The PMF took part in Iraqi military operations alongside other Iraqi forces, erecting checkpoints and carrying out security screenings based on databases of individuals wanted by the Iraqi state.

Of the documented disappearances attributed to the PMF in this report, witnesses said 28 were carried out by the Hezbollah Brigades, one by the Badr Organization, and one by Asa’ib Ahl Al-Haqq. The witnesses said they based their identification of the perpetrators on the flags and logos of the groups involved in the detentions. In six cases witnesses could not specify which PMF group was responsible for the disappearances, but did attribute them to the PMF based on the official PMF flags and logos. The disappearances occurred in or at checkpoints around A'yadhia, Hilla, al-Hwesh, Jurf al-Sakher, Karbala, al-Majer, Musayyib, Razzazza, Samarra, Tuz Khurmatu, Yathrib, and the town of Owainat, between July 2014 and October 2017, including two after November 2016, once the PMF had been formally placed under the command of al-Abadi.

The research also suggests that PMF groups have targeted the men of certain communities who lived under ISIS for arbitrary detentions and enforced disappearances, including residents of Jurf al-Sakher, whose residents fled their homes in October 2014.

For this report researchers documented three disappearances attributed to the security forces of the Kurdistan Regional Government, the Asayish. However, Human Rights Watch has documented many more Asayish disappearances between 2015 and 2017, mostly in the context of military operations against ISIS. The Asayish or Peshmerga (military forces of the Kurdistan Regional Government) has detained and disappeared individuals either at checkpoints or from Kurdistan Regional Government-controlled camps since 2015.

Human Rights Watch spoke to 53 families of currently disappeared persons who had first-hand knowledge of the disappearance. Of these, 38 families requested information regarding their missing relatives from Iraqi authorities but received none. In cases in which families did not seek information about their relatives, they said they refrained from doing so because they feared inquiries would seriously jeopardize the safety of their relatives—most families hope that Iraqi forces will release the disappeared after a period of secret, illegal detention.

In the course of research, Human Rights Watch wrote letters to the human rights advisor to the Prime Minister’s Advisory Council in Baghdad as well as the Kurdistan Regional Government’s coordinator for international advocacy with a list of questions as well as a list of those who vanished after being detained, querying the whereabouts and well-being of those who had been arrested and providing approximate dates and locations of where each person was last seen. On September 18, the Kurdistan Regional Government responded with information about the number of individuals detained for ISIS affiliation through 2017 and its arrest procedures. It did not respond to any of Human Rights Watch’s specific queries, including on the whereabouts of individuals included in the report. Baghdad authorities provided no response.

All 53 families said they were too scared to speak to Human Rights Watch about the disappearance unless they were guaranteed anonymity because they feared retaliation by the security forces.

Alkarama Foundation, a Geneva-based human rights organization, has also expressed concern over threats and physical attacks on rights activists, including attacks on two activists supporting the families of the disappeared in February and March 2018.

Those families that chose to take action reported approaching a range of actors including courts, prisons, the Ministry of Interior’s Inspector General, the speaker of parliament, and other parliamentarians, as well as the Office of the Prime Minister. In all cases, interviewees said that none of the government officials they approached helped them obtain any information about their disappeared relatives. None of the families had a clear idea of which authority they should contact to have the best chances of identifying their relatives’ whereabouts. In addition, none of the families interviewed said they contacted the Iraqi High Commission for Human Rights (IHCHR), the national human rights institution, seemingly because they did not believe the commission could play an effective role in assisting them to find their relatives. One family submitted an urgent action to the Committee on Enforced Disappearances, the body of independent experts which monitors implementation of the International Convention for the Protection of all Persons from Enforced Disappearance which Iraq ratified in 2010. None of the other families knew about the work of the committee.

Most of the families who went to prisons in search of their relatives said they went to Baghdad’s International Airport Prison and the prison at Muthana, an old military base in Baghdad, now home to a group of detention facilities. According to lawyers and penitentiary workers, the Muthana prison complex and the airport prison are both run by the Baghdad Operations Command (which represents a mix of different forces), Military Intelligence, a secret service branch known as Mukhabarat under the command of the prime minister, and a group called the Tactical Unit under the command of the Ministry of Interior. Families told Human Rights Watch that it is widely believe that those who have disappeared following their detention are either dead or in one of these two prison complexes.

Inès Osman, Coordinator of the Legal Department at Alkarama Foundation told a Human Rights Watch researcher in August 2018 that since May 2014, Alkarama submitted 145 urgent actions on cases of enforced disappearances in Iraq to the Committee on Enforced Disappearance. As of March 2018, family members in only six cases ultimately discovered the whereabouts of their relatives but never due to official communications from the authorities. She said the authorities responded to communications from the committee, but generally the responses merely stated the authorities checked their prisons and other databases and did not find the individual, or that the family should file a complaint with the Human Rights Directorate within Iraq’s Ministry of Interior.

The enforced disappearances documented in this report are part of a much wider pattern in Iraq. This report does not include already published research that Human Rights Watch conducted into thousands of men and boys being held in the context of the military operations against ISIS, including the operation to retake Fallujah from May to June 2016, leaving at least 643 men missing from Saqlawiya and 70 from Karma, and Mosul from September 2016 to July 2017. In a December 2017 report, Flawed Justice: Accountability for ISIS Crimes in Iraq, Human Rights Watch documented the authorities in Mosul holding at least 7,374 individuals on charges of affiliation with ISIS, largely without notifying their families, many of whom tried to obtain information about them, and without letting them communicate with their families, amounting to wide-scale enforced disappearances. Researchers estimated that the detention numbers were far greater, a concern supported by an Associated Press article published on March 21, 2018, based on its review of leaked ministry of interior documents on the prison system and other government sources.

Iraq faces serious security challenges, including in its fight against ISIS. However, the state has a responsibility to ensure that the law enforcement response complies with its own laws and international human rights obligations.

Iraq’s new federal government, which will be established in the coming weeks, based on elections which took place in May 2018, and the Kurdistan Regional Government, should make combatting enforced disappearances and investigating past incidents a priority, thus demonstrating their commitment to respecting and protecting the rights of all populations in Iraq. Authorities should do this by establishing an independent commission of inquiry to investigate all cases of enforced disappearances and custodial deaths nation-wide at the hands of military, security, and intelligence forces across all official and unofficial detention facilities The commission should: a) be mandated to recommend cases for prosecution; b) include working groups on data collection, legislative reform, and investigations into individuals’ fate and whereabouts; c) have the authority to recommend cases for prosecution and report publicly on its findings within one year; d) establish a mechanism to compensate victims of enforced disappearance and their families; and e) establish a nationwide register of forcibly disappeared persons, or another streamlined mechanism to allow families to seek information about relatives disappeared and ensure the fulfilment of family rights to truth, justice, and reparations.

Enforced disappearances have plagued Iraq for decades. Widescale protests in 2013 demanded the release of individuals arbitrarily detained and that the government provide information to the families of missing persons arrested in previous years. The Iraqi government seems to acknowledge that this was a problem of the past but has not admitted that government forces and government affiliated groups continue to carry out enforced disappearances.

Iraqi authorities have a duty to investigate cases of enforced disappearance. Instead of simply registering families' complaints of disappearances without follow-up, the courts should order prompt, impartial, and independent investigations. Those in command of the specific law enforcement authorities, including the prime minister and minister of interior, must direct forces to release disappeared persons or charge and prosecute them in fair proceedings where they are afforded their full rights, including the right to communicate with their families and for their place of detention to be made known at all times to their families, legal representative, and other interested parties. Authorities should hold members of the military and security forces responsible for any abuses to account and should compensate victims of enforced disappearance, including the families of the disappeared person.

Each and every case of disappearance needs to be resolved by speedy investigation. If the person is in detention they should be charged or released, if they have died their families should be given full details of the circumstances of the death. Their bodies should be returned to their families.

Human Rights Watch also calls on the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, France, and other states providing military, security, and intelligence assistance to Iraq to urge the Iraqi authorities to investigate allegations of enforced disappearances and to investigate the role of their own assistance in these alleged violations. These states should suspend military, security, and intelligence assistance to units involved in these violations and explain any suspension or end to military assistance publicly. The states should maintain the suspension of assistance until the government adopts measures to end these serious human rights violations.

Recommendations

To Independent Law Enforcement Authorities

Investigations and Prosecutions

- Promptly investigate existing allegations of enforced disappearances, locate and release those held illegally by military and security forces, and prosecute the perpetrators of enforced disappearances.

- Prosecute law enforcement officers of all ranks, including those with superior authority, who are found to be responsible for enforced disappearances. Punish commanding officers and others in a position of government authority who ordered or knew of these abuses.

- Promptly charge detainees against whom there is credible evidence of crimes, in proceedings that adhere to international due-process standards, including stating the location of all detainees, and release all others, providing reparation to those unlawfully detained.

To Iraq’s Newly Formed Federal Government and the Kurdistan Regional Government

- Urgently provide information on the fate and whereabouts of the disappeared people. If the person is in detention they should be charged or released, if they have died their families should be given full details of the circumstances of the death. Their bodies should be returned to their families.

- Immediately suspend, pending a full investigation, any official against whom there is credible evidence that they participated in an enforced disappearance.

- Establish an independent commission of inquiry to investigate all cases of enforced disappearances and custodial deaths nation-wide at the hands of military, security, and intelligence forces across all official and unofficial detention facilities. The commission should: a) be mandated to recommend cases for prosecution; b) include working groups on data collection, legislative reform, and investigations into individuals’ fate and whereabouts; c) have the authority to recommend cases for prosecution and report publicly on its findings within one year; d) establish a mechanism to compensate victims of enforced disappearance and their families; and e) establish a nationwide register of forcibly disappeared persons, or another streamlined mechanism to allow families to seek information about relatives disappeared and ensure the fulfilment of family rights to truth, justice, and reparations.

- Ensure that the range of authorities that families of the missing contact to help locate their relatives are informed about the commission and how to contact it. Provide prompt and substantive responses to queries from the Committee on Enforced Disappearances.

- Recognize the competence of the Committee on Enforced Disappearances to receive and consider individual and inter-state communications pursuant to articles 31 and 32 of the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, in addition to the urgent actions the committee currently considers, by making the required declarations.

Protection

- Coordinate a national strategy among all government bodies and authorities with records of disappeared persons for handling disappearances, which includes a plan for data sharing, with full respect for international data protection standards, for the purpose of effectively locating and disappeared persons.

- Publicly announce a clear and straightforward pathway for reporting disappeared persons so that families can effectively report their cases, without fear of reprisals.

- Make strong and repeated public statements at the highest government levels that clarify that all military, security, and intelligence forces should comply with the law, and that all detained people must be brought to court within 24 hours, as stipulated by Iraqi law.

- Ensure that only bodies with an official mandate to detain and investigate individuals are engaging in detentions.

- Ensure that all detention facilities and detaining authorities maintain a centralized record that is open to the inspection of detainees and their representatives, that includes the names of all detainees, including the dates they were detained, the date the legal authority for their detention expires, the legal basis for their detention, and when they were brought before a judge.

- Ensure that detaining authorities notify family members of the detained, within 12 hours of the arrest, of the time and place of arrest and the place of detention.

- Allow detainees access to a lawyer of their choice or a state-appointed lawyer from the moment of detention.

- Ensure that detainees are only held in official places of detention.

- Ensure that the Iraqi High Commission for Human Rights (IHCHR) has unfettered and unannounced access to all places of detention, as well as sufficient powers of investigation.

International Cooperation

- Clarify the fate and whereabouts of all individuals whose cases are pending before the United Nations human rights mechanisms.

- Ensure serious and independent investigations by effectively collaborating with the relevant United Nations special procedures, including by accepting the requests for country visits made by the Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances and the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, and inviting the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism to visit Iraq to investigate and make appropriate recommendations to combat the phenomenon of enforced disappearances, arbitrary detention, and torture.

To Iraq’s Newly Elected Parliament

- Hold a debate on the abuses by security forces with the view to adopting a motion to compel Iraqi authorities to establish an independent, impartial, multiagency commission of inquiry to investigate the abuses.

To Iraq’s New Federal Government, Kurdistan Regional Government and Parliament

- Ensure the effective implementation of the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance by ensuring that all relevant criminal, civil, and family legislation, as well as policies and practices are consistent with the numerous obligations undertaken by Iraq when it acceded to the Convention, including:

- Codifying an enforced disappearance as a separate and autonomous crime under domestic criminal legislation and ensuring that it carries penalties commensurate with the gravity of the crime.

- Abolishing article 40 of the Penal Code which establishes that an act is not an offense if a public official or public servant commits the act in implementation of an order from a superior which they are obliged or feel obliged to obey.

- Criminalising the responsibility of superior commanders, military, and civilian, as required by article 6 of the Convention.

- Pass legislation to ratify and implement the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture (OPCAT) and set up a National Preventative Mechanism for inspecting all detention centers in Iraq.

To the Iraq High Commission for Human Rights and Independent Human Rights Commission in Kurdistan Region

- Strenuously press the government to open transparent investigations into cases of disappearances and extrajudicial killings.

- Demand that the government respond in a timely and transparent manner to requests for information on cases presented by the commission to the authorities.

- Call for free and unfettered access to all places of official and unofficial detention countrywide.

- Urge the government to establish a list of all places of detention and ensure that detainees are not being held in other, unofficial places of detention.

To Iraq’s Bilateral and Multilateral Donors including the United States, United Kingdom, France, and Germany

- Urge Iraqi authorities to take all necessary measures to fully implement the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance.

- Urge Iraqi authorities to account for the whereabouts of those disappeared, put an end to the practice of enforced disappearances, and ensure the criminal justice system can independently and effectively investigate cases and prosecute the perpetrators.

- Urge authorities to publicly report, in no later than one year, on progress toward accountability for the documented violations.

- Urge authorities to establish a centralized structure for handling disappearance cases.

- Vet for human rights abuses and laws-of-war violations all Iraqi and Kurdistan Regional Government forces that currently receive military aid and security assistance.

- Investigate whether foreign military assistance, including weapons and munitions transfers and military training, contributed to the violations documented in this report. Suspend military, security, and intelligence assistance to units involved in these violations and explain publicly any suspension or end to military assistance, including the grounds for doing so, until the government adopts measures to end these serious human rights violations.

- Governments that provide financial assistance or military aid should ensure their assistance is not contributing to the commission of further serious violations by the armed forces including by assessing if Iraqi authorities are taking genuine steps to investigate and prosecute allegations of serious violations, including enforced disappearances.

- Ensure that any ongoing or future training of military, security, or intelligence forces includes robust instruction on the principles and application of the laws of war and human rights, particularly with regard to detainees.

- Undertake regular joint monitoring visits to military, security, and intelligence forces’ training sites to assess training effectiveness, including on human rights.

- Ratify and implement the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, including its provisions on universal jurisdiction for prosecuting the crime.

Methodology

For this report, Human Rights Watch has drawn on research it has published on enforced disappearances since 2014, and additional interviews carried out from early 2016 to March 2018 with the family members, lawyers, and community representatives of 78 individuals currently forcibly disappeared, as well as three who had themselves been disappeared and were subsequently released. Researchers reviewed court and other official documents relating to the disappearance cases. Researchers called interviewees in July 2018 to confirm their situation was unchanged.

Researchers consulted with international nongovernmental organizations working on cases of disappearances, as well as local lawyers and other legal experts.

Human Rights Watch researchers spoke to interviewees in person when possible, but in some cases did so over the telephone, in Arabic or Kurdish. Researchers informed all interviewees about the purpose and voluntary nature of the interviews, the ways in which they would use the information, and obtained consent from all interviewees, who understood they would receive no compensation for their participation. For reasons of personal security, Human Rights Watch has withheld the names and identifying information of the interviewees and the disappeared.

On July 27, Human Rights Watch sent Government of Iraq and Kurdistan Regional Government authorities a list of questions, soliciting information regarding the documented enforced disappearances. We also provided both authorities with a list of the names of all the disappeared whose families gave us permission to do so, as well as additional identifying information and information about their disappearance, with a request for a response on the whereabouts of each.

On September 18, the Kurdistan Regional Government responded with information about the number of individuals detained for ISIS affiliation through 2017 and its arrest procedures. It did not respond to any of Human Rights Watch’s specific queries, including on the whereabouts of individuals included in the report. Baghdad authorities provided no response.

Human Rights Watch maintains a dialogue with the Iraqi federal government and Kurdistan Regional Government authorities and is grateful for the cooperation we received to assess the facts presented in this report and any resulting recommendations.

Background

In 2009, a representative for the International Committee of the Red Cross stated Iraq was probably facing one of the highest numbers of missing people in the world after three conflicts–a war with Iran in the 1980s, the first Gulf War in 1991, and the US-led military operation in 2003.[1] The International Commission on Missing Persons, which has been working in partnership with the Iraqi government to help recover and identify the missing, estimates that the number of missing people in Iraq could range from 250,000 to one million people.[2]

In 2010 Iraq acceded to the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (hereinafter the Convention). However, it did not recognize the competence of the Committee on Enforced Disappearances (CED) to receive and consider individual and inter-State communications from individuals claiming to be victims of violations under articles 31 and 32 of the Convention.[3] As a result individuals and organizations can only file complaints under article 30 of the Convention (urgent actions). In the case of urgent actions filed under article 30, technically the CED does not adopt a decision on the cases, however communications filed under articles 31 and 32 can result in the CED adopting a decision or publishing a report.

The CED pointed out in its 2015 review of Iraq’s compliance with the Convention that while provisions of articles 322, 324, 421, 423, 424, 425, and 426 of the Iraqi Penal Code and article 92 of the Criminal Procedure Code No. 23 of 1971 criminalize certain acts incorporated in the definition of the crime of enforced disappearance, according to authorities, the crime itself, as defined by the Convention does not exist in Iraqi law.[4] The Iraqi Supreme Criminal Tribunal Act No. 10 criminalized enforced disappearance as a crime against humanity, but that was restricted to offences committed between 1968 and 2003.[5] An initiative to pass a new law prohibiting enforced disappearances as a distinct crime in 2015 and again in 2017 has been stalled in parliament.[6]

In addition, article 40 of the Penal Code establishes that an act is not an offense if a public official or public servant commits the act in implementation of an order from a superior which they are obliged or feel obliged to obey.[7] This may have an impact on the implementation of the obligation under article 6 of the Convention to bring all those involved in the perpetration of enforced disappearances to justice.[8]

Iraq should criminalise the responsibility of superior commanders, military and civilian, as required by article 6 of the Convention, which states criminal responsibility should apply to superiors who:

(i) Knew, or consciously disregarded information which clearly indicated, that subordinates under his or her effective authority and control were committing or about to commit a crime of enforced disappearance;

(ii) Exercised effective responsibility for and control over activities which were concerned with the crime of enforced disappearance; and

(iii) Failed to take all necessary and reasonable measures within his or her power to prevent or repress the commission of an enforced disappearance or to submit the matter to the competent authorities for investigation and prosecution.

Iraq’s Criminal Procedure Code allows police and “crime scene officers” to detain and interrogate criminal suspects.[9] It defines crime scene officers in a broad manner, making it impossible for Iraqi defense lawyers to ascertain which forces have a detention mandate.[10] Iraq has many different groups that make up its military and security forces, with many groups straddling the divide between military and law enforcement operations and falling under the command of the prime minister, the minister of interior, or minister of defense. These groups are conducting arrests in and outside the context of military operations, sometimes leading to disappearances.

Human Rights Watch researchers did not ask all of the groups whose role in disappearances is documented in this report whether they have a mandate to arrest, however leaders of the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) and National Security Service (NSS) told Human Rights Watch researchers on several occasions that they do not have the authorization to do so. Lawyers and judges as well as the deputy head of the Ministry of Interior’s Intelligence and Counter Terrorism Office in Mosul have said that in their view only Ministry of Interior forces have the legal authority to detain and interrogate civilians.[11] These sources said only the Intelligence and Counter Terrorism Office can detain and interrogate those suspected under the counterterrorism law.

While authorities did not respond to Human Rights Watch’s inquiries into what steps families should take if relatives are detained but they have no information regarding their whereabouts. Iraq’s response to the concluding observations on the report of Iraq concerning the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance in May 2017, stated:

[T]he Supreme Judicial Council, represented by the Presidency of the Public Prosecution Service, is vigorously addressing all requests from relatives of disappeared persons whose fate is unknown. It receives the requests from the Human Rights Division that was established in the Presidency of the Public Prosecution Service … [and] [t]he Human Rights Department in the Ministry of Defence also receives through its hotlines complaints and requests from citizens for research and investigations into the fate of missing persons, which are conducted without delay in cooperation with the military sectors and in coordination with the security services in order to bring the sufferings of victims’ families to an end.[12]

However, Alkarama has reported that in its work assisting families file complaints with the Committee on Enforced Disappearances, it has “witnessed that the above mentioned mechanisms for investigating the fate of the disappeared are ineffective.”[13] Furthermore, it documented incidents where relatives “inquiring about the fate and whereabouts of the disappeared with the Iraqi authorities, including after filing claims at police stations, were also subjected to enforced disappeared [sic], in what appears to be a clear act of retaliation.”[14]

In its 2015 concluding observations of Iraq’s compliance with its obligations under the Convention, the Committee on Enforced Disappearances raised concern at the lack of accurate and disaggregated statistical information on those disappeared.[15]

Patterns of Disappearance and Responsible Forces Since 2014

In the 78 cases of enforced disappearances Human Rights Watch documented for this report between April 2014 and August 2017, military and security forces apprehended 34 of the men and boys from checkpoints, and another 37 from their homes. In another five cases, Federal Police, Ministry of Interior’s Intelligence and Counter Terrorism Office, and the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) disappeared men from areas formerly under Islamic State (also known as ISIS) control in locations other than their homes and checkpoints. These locations include Kirkuk courthouse, a displacement camp, Baghdad International Airport, and the Yathrib local police station. In another case, a Federal Police officer was detained likely by the PMF off the street, and in a final case, a man was detained by a PMF member outside the Civil Directorate in Tuz Khurmatu. Most of the disappearances were of Sunni men and boys.

Under Iraq’s Criminal Procedure Code, police may detain suspects only after a court-issued arrest warrant, and they must bring suspects before a judge within 24 hours in order to mandate their continued detention.

According to witnesses or family members however, as far as they knew, in all the cases documented here, forces detained the individuals without any court order, arrest warrant, or other document justifying arrest, and often did not provide a reason for the arrest. In cases in which a reason was given, it was always linked to terrorist allegations, typically linked to ISIS. None knew whether their relatives had been brought before a judge in the allotted amount of time. Researchers observed that thousands of prisoners facing terror charges are held for months before they see a judge, during which time they are not allowed to communicate with their relatives, and during which time their families generally receive no notification about their whereabouts and fail to obtain information about their relatives despite their best efforts.

The United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners requires notification of family and communication with them, a requirement numerous officials in Iraq told researchers they see as a legal obligation.

In all of the 78 cases Human Rights Watch documented in this report however, families were unable to communicate with their detained relatives or obtain any information about them through official channels, either through their own requests for information, or through Human Rights Watch.

All of those disappeared from checkpoints but one were Sunni men and boys from areas that fell under Islamic State control for varying periods of time, and the disappearances took place as part of terrorism screening procedures. The apprehensions from homes were in some cases security sweeps of residents residing in areas formerly under the control of ISIS while others were seemingly targeted arrest operations.

The disappearances were carried out by a range of security forces, including, the Anbar Operations Command, Counter Terrorism Service (CTS), PMF, Federal Police, Ministry of Interior’s Intelligence and Counter Terrorism Office, National Security Service (NSS), SWAT (Special Weapons And Tactics), Prime Minister’s Special Forces (a set of units charged with the protection of the Prime Minister, the International Zone in Baghdad, as well as the city itself), and Kurdistan Regional Government’s Asayish Forces.

The accounts of the disappearances documented for this report focus on both the forces involved in the disappearances, and the location and manner in which they took place. The accounts represent a snapshot of disappearances perpetrated by the different actors in Iraq between 2014-2017. Given the small sample size these findings cannot be viewed as representative of disappearances in Iraq, they do however highlight certain key actors, weaknesses within the system of law enforcement, and potential trends.

Detentions at Checkpoints as Part of Terrorism Screening Procedures

Human Rights Watch has documented 33 cases in which Iraqi security forces at checkpoints disappeared Sunni men and boys from areas that fell under ISIS control, and one more instance where the individual detained was not from former ISIS-controlled areas. The disappearances took place between July 2014 and October 2017 and were carried out by the Anbar Operations Command, Asayish, CTS, and PMF.

Anbar Operations Command

Human Rights Watch has documented one case in which the Anbar Operations Command, an integrated military and security command, was implicated in the enforced disappearance of eight Sunni men who were displaced by the fighting against ISIS in Anbar governorate from a checkpoint in October 2017.

“Ziad,” 38, a laborer, and his family fled from the town of al-Baghdadi in Anbar, 180 kilometers northwest of Baghdad, along with 50 other families in August 2014, when ISIS took control, inviting airstrikes and other attacks from the Iraqi army, Ziad’s wife “Rawan,” 29, said.[16] Their family fled to different areas, ending up in 2017 in a camp for the displaced in Nineveh. According to Rawan, in October 2017 her family as well as other families from al-Baghdadi left the camp in four government buses to return home since their town had been retaken by Iraqi forces in 2015. When the busses reached Suqur checkpoint, the main checkpoint between Anbar and Baghdad, she said soldiers in uniforms with the Anbar Operations Command insignia, who man the checkpoint, screened the identity cards of the men on the buses, and then forced her husband and seven other men from the group to remain with them without explanation, before escorting the rest of the group to al-Khalidiya Central Camp in eastern Anbar. “Since then I have had no news of my husband,” she said, and added that she was too fearful to pursue more information on his whereabouts and wellbeing.

Asayish

Human Rights Watch documented a case in which Peshmerga forces operating a checkpoint near the frontline with ISIS in 2015 detained two individuals and apparently handed them over to the custody of Asayish forces, as is the general practice in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq.[17]

On the night of October 30, 2015, after an airstrike on the ISIS-controlled town of Qayyarah in Nineveh governorate, some civilians including “Malik,” 23, and his cousin “Maqsud,” 27, fled, according to Malik’s father, “Sufyan,” 52.[18] Sufyan said he spoke to his son, who said they were heading in the direction of al-Kuwayr, a village in the area where Peshmerga were present and manning a checkpoint at the time. He said he never heard from his son again and his son’s phone was then switched off.

Several months later, Sufyan said he attended a meeting in Qayyarah between a tribal sheikh and a group of Peshmerga officers. He said he asked a Peshmerga officer who was there about his son and cousin. The officer remembered them and said he had been present at the checkpoint and had transferred them and other young men he had detained into the hands of the Asayish. He put Sufyan in touch with an Asayish officer, who then asked Sufyan for about US4,800, to facilitate his release. Sufyan refused, saying he did not have the means. Since then he has tried to obtain information on their whereabouts but has failed.

In another instance, Asayish forces running a checkpoint in the disputed territories disappeared another man. “Ayman,” 37, described to his father how he was detained by Asayish security forces on April 14, 2016 at the Taza checkpoint, 15 kilometers south of Kirkuk city. According to his father, Ayman told him the Asayish took him to a facility in Sulaymaniyah governorate. He said Ayman was never given a reason for the arrest and never brought before a judge during his time there. He also was not allowed any contact with his family or a lawyer. Eventually, on December 28, 2016 the Asayish handed Ayman to the Ministry of Interior’s Intelligence and Counter Terrorism Office in Kirkuk and nearly one year later, on December 11, 2017, he was taken to court and convicted under provision 4 of the counterterrorism law for a bombing in 2015 on a street in Kirkuk city and sentenced to 15 years. His father said he learned the details of what happened when he first saw his son in court in December 2017, before which he contacted various authorities trying to locate him but was unable to do so.[19]

Counter Terrorism Service

During the battle for Mosul, the CTS established a central screening checkpoint south of Mosul from October 2016 to August 2017, known as Scorpion Junction. Human Rights Watch has documented five enforced disappearances by the CTS of Sunni men and boys, who had lived in the Mosul area under ISIS from Scorpion Junction in August 2017. In all cases, the interviewees said they knew CTS was responsible for the disappearances because of the officers’ uniform logos.

CTS forces manning the checkpoint detained “Atheer,” 15, and his brother “Saddam,” 17, from Tal Afar, on August 28, 2017, their mother said.[20] She said CTS forces took her sons, both students due to go back to school in September, out of the family’s car at the checkpoint after inspecting their identity cards.

We were all in a car together, the officers stopped the car, and took them out of the car, and said we would see them again in four days. I have no idea why they wanted to question them, they are just boys. While we were there, I saw the officers take at least 10 people who really looked like boys out of buses transporting large numbers of displaced families.

She said that despite the assurances from the officers that her sons would return in four days, since their arrest they have vanished and no government entity has given her any information about their fate or whereabouts, despite her requests for information.

CTS officers at Scorpion Junction also detained “Ali,” 43, from Tal Afar, on August 20, 2017 after checking his identity card while he was in his car, according to his wife who was with him. She contacted the security forces to try to locate her husband but was unable to.[21] “Latifa,” 33, said the same thing happened to “Salahaden,” 41, and “Badir,” 60, her husband and father from Samarra, as the three of them were passing the checkpoint in their car and an officer checked their identity cards on August 30, 2017.[22] She said that she has not seen her relatives since and that despite multiple requests, no government entity gave her any information about their fate or whereabouts.

All the families who had relatives detained at Scorpion Junction said they feared inquiring more forcefully into their relatives’ whereabouts, worried that it might worsen the circumstances of their relatives who were being held or lead to their own arrest.

PMF

The highest number of disappearances documented by Human Rights Watch, 36 cases, was perpetrated by different groups of the PMF. The PMF brought together a number of new and preexisting armed groups under one banner soon after ISIS took control of Mosul in June 2014 and former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki and Iraq's supreme Shia religious cleric Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Husseini al-Sistani called for men to join the fight against ISIS. In February 2016, Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi issued Order 91, officially incorporating the PMF as an “independent military formation” within Iraq’s security forces under the prime minister’s command. On November 26, Iraq’s parliament passed a law formalizing the decision. Until then, PMF groups operated with the support or acquiescence of the Iraqi government, taking part in Iraqi military operations alongside other Iraqi forces, and erecting checkpoints and carrying out security screenings based on databases of individuals wanted by the Iraqi state.

Of the 36 documented PMF disappearances in this report, witnesses said 26 of them took place when PMF forces detained the individuals at checkpoints. Of those 26 cases, witnesses say they believed, based on the flags and logos they saw, that Hezbollah Brigades carried out 24 of the disappearances. In two instances witnesses did not know which PMF forces were responsible.

One of the disappearances occurred at a checkpoint in Musayyib, another at the al-Hwesh checkpoint located along the road between Samarra and Tikrit, 57 kilometers north of Yathrib, one in Yathrib, one in Hilla, two in the town of Owainat, 10 kilometers south of Tikrit, one at al-Wind checkpoint, south of Jurf al-Sakher, another at a checkpoint in Jurf al-Sakher and 18 at al-Razzazza checkpoint, between May 2015 and January 2017.[23]

All of the documented cases of men disappeared by the PMF from these checkpoints were Sunni and from areas that had come under ISIS control.

Disappearances at al-Hwesh Checkpoint

On January 20, 2017, “Hussein,” a 27-year-old friend of “Abad,” 30, offered to drive Abad and his family, from Kirkuk to their home town, Yathrib, Hussein told Human Rights Watch.[24] Although everyone possessed security clearance from a range of forces including the PMF group Saraya al-Salam, Iraqi Army, intelligence forces, and local police forces, men wearing civilian clothes stopped them at al-Hwesh checkpoint at around 4 p.m. The checkpoint is permanent; located along the road between Samarra and Tikrit, 57 kilometers north of Yathrib; and manned by intelligence officers, local police, PMF intelligence officers, and Saraya al-Salam, he said. Hussein said a few of the PMF officers began asking the family where they were going and where they came from. They then arrested him and the family has heard nothing of him since.

Disappearances at Musayyib Checkpoint

On June 15, 2015, PMF forces at a checkpoint in Musayyib, a town in Babil governorate, detained “Tahir,” 31, a truck driver from Mosul, according to his brother and “Hasiba,” a teacher from Mosul who witnessed the events.[25] Hasiba said she was coming back from Baghdad, where she went to collect her retirement salary, to Mosul, via the route that passed through the Musayyib checkpoint, which was being manned by masked men wearing black uniforms and carrying two flags. She said one flag bore the Hezbollah logo. She told researchers she saw the masked men stop about 30 civilian cars while she was at the checkpoint, taking the men out, blindfolding and handcuffing them, and putting them in a bus. She said they forced the women and children to hail rides to Kirkuk but kept the men and the cars. Tahir’s brother said he had spoken to his brother on June 15 as he was arriving at the checkpoint in Musayyib, after which his brother hung up and then stopped replying to his calls, with his phone later switching off. He has not spoken to his brother since June 15, 2015 and has been too scared to pursue more information.

Disappearances at Owainat Checkpoint

At 11:30 a.m. on July 7, 2014, cousins “Samer,” 19, and “Anah,” 22, both unmarried students from Tikrit, vanished as they traveled from Tikrit south to the town of Owainat in Anah’s car, according to Samer’s father.[26] He said he was in touch with his son until they were arriving in Owainat, after which their phones were switched off. He said the next day, a friend who is a PMF member and also works in the penitentiary system called him saying Hezbollah forces had detained the two cousins en route, and they were being held in Samarra prison, an official detention facility. Samer’s father said two months later, he traveled to Samarra Operations Command and registered Samer and Anah’s names as missing. At the same time, he spoke to guards at two prisons in Baghdad but in both instances the guards said they checked their database and had no prisoners by his son’s names. In the nearly four years since their disappearance he has requested but not been able to obtain any official acknowledgement that they are being held by government forces or any information about their fate or whereabouts.

Disappearances at al-Razzazza Checkpoint

Sunni Arab families across Iraq speak with fear about al-Razzazza checkpoint in Karbala governorate, a checkpoint established in 2014 by Hezbollah Brigades as a response to ISIS presence in Anbar and the main checkpoint for travelers passing from Anbar to Baghdad, Karbala, or Babil. Hezbollah forces manned the checkpoint, until it was dismantled in 2017.

The families with relatives taken at al-Razzazza checkpoint, said they went to different courts to request information on their whereabouts and showed Human Rights Watch the related paperwork, including stamped court documents. In all of the cases, the families tried to obtain information through official channels about their disappeared relatives but did not receive any. In all but one case, the disappeared men never returned home.

On May 23, 2015, a group of four men, “Hakim,” 37, “Mahmood,” 33, “Matashar,” 34, and “Abdul,”35, all taxi drivers from the same tribe, displaced from their homes in al-Zangourah, Anbar governorate, were en route to collect humanitarian assistance in al-Khalidiya, also in Anbar, along the highway between Ramadi and al-Khalidiya, according to Hakim’s brother.[27] His brother said that at about 3 p.m. Hakim called him and told him that he and the three other men had been stopped by Hezbollah Brigades at al-Razzazza checkpoint and that they were detaining them. His phone was switched off after that, and their families are all too afraid to contact Hezbollah to search for their relatives, the brother said. The men have been missing since then.

On November 13, 2015, law student “Nasim,” 26, was on a bus from Karma, in Anbar governorate where he is from, to Baghdad to start a new university semester, his brother told Human Rights Watch.[28] He said he spoke to Nasim at 11:30 a.m., just before Nasim was to pass through al-Razzazza checkpoint. He said shortly afterwards, Nasim’s phone switched off. That night, Nasim’s father called the bus driver to ask about his son’s whereabouts. The driver told him that Hezbollah forces manning the checkpoint had removed Nasim from the bus, seemingly without cause, his brother said. Nasim’s family registered his name with the Anbar Provincial Council, they said, and asked about him at Muthana Airport prison in Baghdad but prison guards said he was not there.

“Akil,” 34, from then ISIS-controlled al-Qaim, was in a car with a group of fellow civil servants from the Ministry of Industry and Minerals on November 15, 2015 according to his father.[29] He said they were trying to get to Baghdad with ministry paperwork they had smuggled out of the city. At around 10:30 p.m., they were passing through al-Razzazza checkpoint where Hezbollah forces detained Akil, the other workers told his father later. He said he has tried to get news of his son including by contacting staff at the Ministry of Industry and Minerals by phone but that he has received no response.

On December 20, 2015, Hezbollah forces at al-Razzazza checkpoint detained “Wisam,” 63, and his son “Amir,” 22, according to Wisam’s father “Khalaf,” from al-Qaim, but allowed Khalaf’s wife and five daughters who were also traveling with them to go through.[30] Six days later, the same forces at the checkpoint detained Khalaf’s cousin “Abdul Razzaq,” 19, letting his mother, who was with him, go. He said he has been trying to locate all three men ever since, and has appeared before judges at three separate courts in Anbar governorate, with judges signing documents of proof of disappearance and opening an inquiry into their whereabouts, but has obtained no information.

“Nawar,” 53, from al-Qaim made it to al-Razzazza checkpoint with his two sons “Bilal,” 24 and “Yassar,” 21, both students, having fled ISIS on January 4, 2016, having tried but failed to escape several times before.[31] He described how his sons were detained by Hezbollah at the checkpoint, despite assurances from a fighter that there was no evidence against them. He said:

We arrived at the checkpoint at 3 p.m., after two days of traveling and being screened at two previous checkpoints. I saw Hezbollah forces at the checkpoint and a caravan with their logo on it behind the checkpoint. First, they searched all of our bags, then one masked man came up to us and asked where we were from and what tribe we were from. He took our identity cards and returned a few minutes later with another masked man who took Bilal into the caravan, and a few minutes later, came and took Yassar away in the same direction. One of the guys came out of the caravan, handed me my identity card and said, “Your sons have nothing against them, but we need to investigate them and then we will let them go.”

Nawar said he left, went straight to the Anbar Provincial Council office, then to the Ministry of Interior’s inspector general, the speaker of parliament, numerous members of parliament, until finally, he got a letter on March 29 from the Prime Minister’s Office ordering the Ministry of Interior to locate the men. He said he has not received any information from the Ministry of Interior or any other government entity about the fate and whereabouts of his sons since.

“Jabar,” 68, from al-Qaim, said that according to his sons’ wives, Hezbollah detained his sons “Naif,” 39, and “Azam,” 21, both laborers, at al-Razzazza checkpoint on March 3, 2016 as they were traveling with their families to Baghdad. He said Hezbollah forces released the women and children traveling with Naif and Azam, who said that they provided no reason for detaining the two men.[32] One of his son’s wives called him to tell him what happened after their husbands were detained, once the women and children had made it to Baghdad.

“Abd al-Khalaq,” 52, was traveling from Baghdad to Mosul on March 12, 2016 in a shared taxi, his wife told Human Rights Watch.[33] She said he was returning to their house and his shop in Mosul, which he had to abandon two years earlier because of ISIS’ control of the city. She told researchers he called her at around 9 a.m. just as he was arriving at al-Razzazza checkpoint. An hour later, she said that when she tried him on his phone it was switched off. “We had sent a driver we knew to meet him in Rutba, about 300 kilometers west of Razzazza,” she explained. “So at 2 p.m. I called the driver, who said he had never arrived there. I kept calling his number at around 6 p.m. his phone was on again but no answer, and then it turned off 15 minutes later.” She traveled to Karbala governorate and Baghdad governorate where she said she contacted prisons, and intelligence offices, as well as the courts seven times, but has been unable to locate him.

“Shamal,” 37, from al-Qaim, said he was on the phone with his brother “Salam,” 33, a shopkeeper, on January 12, 2016 when Salam and other relatives were fleeing toward Baghdad because of fighting between government forces and ISIS in al-Qaim.[34] When they arrived at al-Razzazza checkpoint, his brother hung up, and very soon after, his phone was turned off, Shamal said. Shamal, has not heard from Salam since. Several hours later, Salam’s wife called Shamal, and said that Hezbollah forces at the checkpoint had detained Salam. Shamal said her taxi driver drove her on to Amiriyat al-Fallujah camp for the displaced. He said the family has had no news of Salam since.

Home Arrests

Human Rights Watch documented 37 cases in which individuals were detained by military or security forces from their homes. In 19 cases individuals were detained from their homes in Baghdad. In five cases, these arrests happened after anti-ISIS military operations and in three cases, they happened after other major security incidents.

Detentions from Homes in Baghdad

Human Rights Watch documented 19 cases in which individuals were detained from their homes in Baghdad and disappeared. In most of the cases, the families of those detained were given no reason behind the arrest, although they suspect it was related to their identity as Sunni Arabs and that the arrests were broadly linked to counterterrorism operations, a justification used across Iraq for arrest campaigns.

These detentions were carried out by a range of the prime minister’s security forces, NSS, SWAT, and Ministry of Interior intelligence forces between April 2014 and July 2016. Those responsible for the detentions identified themselves at the time or were identified by witnesses.

Ministry of Interior Intelligence and Counter Terrorism Office

On August 28, 2014, six officers identified themselves as Ministry of Interior intelligence forces when they detained “Khaled,” 27, a laborer, from his home in Baghdad’s al-Kifah street at 1:30 a.m., according to his brother who was also home at the time.[35] His brother said they entered their house and asked Khaled and his wife basic questions about their names, ages. They then accused them of hiding weapons and conducted a search, saying they were looking for weapons. They did not find any weapons but Khaled’s brother said he saw them handcuff Khaled and take him away, confiscating his phone too. His brother said he went to several security offices, prisons, and courts, all in Baghdad, but could not find Khaled or any information about where he was. “I have no idea why they targeted us and took my brother,” he said.

National Security Service and SWAT

In one case, a woman living in Baghdad said NSS and SWAT forces, who she could recognize because of the logos on their uniforms, detained her unmarried son “Shaiab,” 28, on July 13, 2015 from their home.[36] NSS and SWAT forces are both under the Ministry of Interior. She said the forces first came to her house on July 11, 2015 but did not take her son who was sick and in bed then. She said when they returned two days later, the same forces said his name matched that of a wanted ISIS member and took him away. A relative who works for the government told her Shaiab was being held at the Baghdad International Airport prison. She said she tried to get access to the prison but was turned away by an officer saying her son was not there. She said she visited another prison in Baghdad but still could not find him. Since his detention she has not seen him and no government entity has given her any information about his fate or whereabouts, she said.

“Fawad,” 55, was a pilot with the Iraqi Air Force, his brother, “Laqman,” told Human Rights Watch.[37] On August 20, 2014, Laqman said he saw about 12 civilian and security vehicles pull up outside their house in al-Mada'an neighborhood of Baghdad, and officers entered the house, demanding to arrest the “terrorist pilot.” He said Fawad fled the house and remains in hiding. Nearly two years later, Laqman said that on July 24, 2016, at around 6 p.m., he was home when eight armed men arrived in a black vehicle and detained three of his other brothers: “Bashar,” 51, a civil servant, and “Muhammad,” 46, and “Abduladem,” 43, both mechanics. Laqman said he contacted a range of officials trying to find out what happened to his brothers. In response, he said he received two official letters, which he showed to Human Rights Watch.

One dated June 18, 2017, from the Intelligence and Counter Terrorism Office to the Head of the Security and Defense Commission, stated the three brothers are not wanted, nor in custody. A second letter dated May 29, 2017, from the High Judicial Council, requested all ministries and courts to search for the brothers. Laqman said no ministries or courts responded to the letter or took any apparent action in response to the request.

Finally, Laqman said he spoke to two individuals working in the penitentiary system who told him confidentially all three were held by the NSS, but said they were too scared to share more details. Laqman said he was too scared to search for them, worrying he might get detained himself, and has not been able to contact his brothers or obtain any other information about their fate and whereabouts.

Prime Minister’s Forces

Close to midnight on June 13, 2014, a group of armed men stating they were the Prime Minister’s Special Forces, and wearing green and brown uniforms, stormed the home of “Kamal,” 55, a laborer in the Dora neighborhood in Baghdad, his wife said.[38] She said they broke down the door, dragged Kamal from his bed into the kitchen, and confiscated his phone and laptop, before detaining and taking him away. His wife said they did not provide any reason for the arrest but that Al-Qaeda and ISIS supporters were present in the area where they lived. She said she went to a range of different security offices, courts, and prisons asking about her husband but has not located him or received any information about what happened to him.

Baghdad Arrests of April 21, 2014

Researchers spoke to the families of 13 men detained in Rahmania and Sheikh Ali neighborhoods of Baghdad nine days before Iraq’s scheduled parliamentary elections. At the time, Nouri al-Maliki was still prime minister. Witnesses to the arrests did not observe anything that allowed them to identify the reason for the disappearances but, a community representative living in Sheikh Ali told Human Rights Watch he knew of many Sunni neighborhoods targeted at the same time, linked to the government’s concerns around Al-Qaeda and ISIS recruitment in this and other neighborhoods. He did say however, that he believed there was a chance the arrests were instead linked to the elections and concerns around who local imams would tell the residents to vote for.[39]

He said he had drawn up a list of all the detentions that day, going house to house and interviewing each family and said that in total on April 21, forces detained 40 men from the neighborhood, including one blind man.

Those interviewed were not sure which of the various forces under the prime minister’s control including his Special Forces, Counter Terrorism Forces, or Mukhabarat, were responsible.

According to the sister of laborers “Abdullah,” 38, and “Qais,” 35, at around 2 a.m. on April 21, 2014, she saw several black vehicles with falcon stickers, a logo of members of several different Iraqi forces, on the doors pull up outside their home in Rahmania neighborhood, Baghdad.[40] She said 10-12 officers in black with red berets entered their home and said they were from the Prime Minister’s Office. They asked for her brothers and then drove away with them without explanation, she said. After two days of silence, she said she went to the Ministry of Interior, where officials said they had no information about her brothers’ whereabouts. She tried to visit Baghdad International Airport prison and Abu Ghraib prison but officials there told her that her brothers were not held in either facility.

Additionally, at around 2 a.m., a team of four officers detained “Omar,” 38, from his home in neighboring Sheikh Ali neighborhood of Baghdad, his wife said.[41] According to her, they entered the house and identified themselves as forces from the Prime Minister’s Office. She said they had the falcon logo on their uniforms. They handcuffed her husband and took him away without providing any reason. Since then, she said she contacted numerous prisons in Baghdad and in neighboring governorates trying to find him but the guards at all the prisons told her he was not a detainee there.

The wife of “Hardan,” 42, told Human Rights Watch that men wearing black uniforms and red berets introduced themselves as forces from Muthana airport prison and entered their home on Haifa street in Sheikh Ali neighborhood at 2:15 a.m.[42] She said they took her husband, stating they needed to speak with him and instructed her to go to the Muthana airport prison in the morning to pick him up. She said when she appeared at Muthana airport at 6 a.m. the next day, the officers said they could not find him in their database. She has not heard from him since.

The sister of “Hussam,” 57, a water truck driver and “Dawad,” 42, an employee at the Youth Ministry, told Human Rights Watch she saw a group of forces in black Humvees and a pickup truck, all with the falcon logo, arrive outside their home the same neighborhood. Five officers came to the door and demanded entry, detained her brothers at 2:30 a.m. saying they needed to question them but would bring them home shortly.[43] She said their family said they contacted every security, intelligence, prison, and judicial office they could think of for information, with each one saying they had no knowledge of the detention or whereabouts of her brothers.

According to the sister of “Khalil,” 47, a primary school teacher, forces came to their home at the same time, in the same neighborhood. As several men barged into their home and stormed upstairs demanding to take Khalil, his two sisters went running after them. “They had cut the electrical wires to our house, so we could not turn on the lights. A few of them told his sisters to wait a room and closed the door, ordering them to stay there. As they did that, I asked one of them who sent them. He said they were forces linked to Maliki’s Dawlat al-Qanoon [State of Law] coalition,” Khalil’s sister said.[44] She said they went to the speaker of parliament a few days later, asking for his help, but he did not follow up or contact them again.

The same thing happened to “Sufian,” 35, a taxi driver, according to his aunt who was home at the time. The wife of “Mahnad,” 42, a construction worker, said the men who took her husband at the same time and in the same neighborhood identified themselves as military intelligence officers.[45]

Home Arrests During Anti-ISIS Military Operations

Human Rights Watch documented five cases, in which PMF and Ministry of Interior’s Intelligence and Counter Terrorism officers disappeared Sunni men and boys during or after military operations against ISIS. The disappearances took place between June 2015 and August 2017.

According to his wife, who was present at the time, at 5 p.m. on September 9, 2014, PMF detained “Yusuf,” 60, a farmer, from his home in al-Abbasiyyah sub-district in Samarra, at a time when the area was seeing continuous ISIS attacks targeting military installations. She was able to identify the arresting forces as members of the PMF because of their flags and logos on their uniforms. She said they provided no reason for taking him.[46] At the time, she said that she had seen forces wearing the logos of both Badr and Saray Ashura in the area, as well as the Federal Police. His family has inquired at a prison in Baghdad but received no information since, she said.

“Akram” told researchers that at 2:30 p.m. on June 6, 2015, 50 masked men in eight Humvees flying the flags of Hezbollah, which he recognized, arrived at his home in the village of al-Majer, near Ramadi in Anbar governorate, after it was retaken from ISIS.[47] He said the fighters demanded to detain his sons “Ahmed,” 24, and “Ibrahim,” 22, both university students. Akram told Human Rights Watch that Hezbollah forces detained approximately 44 men from the village that day, none of whom had been released according to their families. Akram has not had any communication with his sons since their detention and has been too scared to seek information about where they currently are or why they are being detained.