Summary

On April 23, 2017, Yameen Rasheed was found with 34 stab wounds in the stairwell of his apartment building in Malé, the capital of the Maldives. He died shortly after being taken to the hospital. Rasheed was a prominent blogger and social media activist known for his satirical commentaries on Twitter and his blog, The Daily Panic. His ridiculing of public figures had enraged politicians and religious extremists. He had received threats on social media. After his death, the police made some arrests, but said that they believed the attack was the work of angry Islamists, rather than being politically motivated. His family does not trust the justice process. A year after his son’s death, Hussain Rasheed wrote in the Indian Express:

The truth is that the Maldives is a dangerous place for anyone who dares to criticise the ruling regime, or who expresses opinions about the state of society. As the president himself warned following Yameen’s murder: “Anything can happen.” There is total impunity.

The Maldives is an archipelago in the Indian Ocean. Increasingly autocratic measures by the Maldives president, Abdulla Yameen Abdul Gayoom, who took office following a disputed election in 2013, are eroding fundamental human rights in the island country, including freedom of association, expression, peaceful assembly, and political participation. Recent governmental decrees that block opposition parties from contesting elections, the arrest of Supreme Court justices, and the crackdown on the media all reflect government steps to silence critics. Religious extremists and criminal gangs—including many that enjoy the patronage of politicians—assault dissenters with impunity. Social media trolls threaten those deemed to have criticized Islam or the ruling party.

Ahead of the presidential elections scheduled for September 23, 2018, the government has moved to expand its use of broad and vaguely worded laws to intimidate, arbitrarily arrest, and imprison its critics. Among these are counterterrorism laws widely used against opposition activists and politicians; anti-defamation laws used against the media and social media activists who criticize the president or his policies; and restrictions on assembly that prohibit or severely limit peaceful rallies and protests.

This report, based on interviews with journalists, lawyers, human rights defenders, political activists, and others in June and July 2018, examines how the government is using and abusing such laws, and the crippling effects this has had on the Maldives’ nascent democracy and struggling civil society.

Targeting Freedom of Speech

The Maldives has a long history of using criminal defamation laws to stifle dissent, but threats to the media and opposition critics increased after the August 2016 enactment of the Anti-Defamation and Freedom of Expression Act. The law sets heavy fines for content or speech that “contradicts a tenet of Islam, threatens national security, contradicts social norms, or encroaches on another’s rights, reputation, or good name.” Failure to pay the fine is punishable with imprisonment for up to six months and the closure of the newspaper or media office. The law also requires journalists to reveal the sources of alleged defamatory statements, a provision that contravenes the constitution.

Raajje TV, among the biggest private broadcasters in the Maldives, has repeatedly been targeted by the authorities for defamation. The opposition-aligned network has already been fined several times under the 2016 law by the regulatory Maldives Broadcasting Commission. Journalists deemed sympathetic to the opposition were arrested after anti-government protests in March 2018, and some have recently reported threats by criminal gangs apparently hired by ruling party politicians.

Concern over attacks by hired gunmen are not unfounded. Ismail Hilath Rasheed, a blogger and former editor of the Maldivian newspaper Haveeru, was stabbed on June 5, 2012. He had been previously arrested and had his blog shut down by the government for “anti-Islamic material.” Hilath survived the attack and told journalists that his assailants had named three senior political and religious figures during the attack, and that they had been promised “entry to heaven” for murdering someone who “defended freedom of religion and gay rights.” A government official said that while the government condemned the attack, “Hilath must have known that he had become a target of a few extremists.” No one was arrested for the attack.

Ahmed Rilwan, a journalist with the Maldives Independent and well-known blogger, has been missing since August 8, 2014. Rilwan used the Twitter handle @moyameehaa to criticize corruption and religious extremism, and had received numerous threats on social media. Shahindha Ismail, the founder and executive director of the Maldivian Democracy Network, said she was threatened for calling for religious tolerance. Journalist Zaheena Rasheed was forced to leave the country because she was featured in an Al Jazeera documentary, “Stealing Paradise,” which exposed systematic corruption at the highest levels of the Maldives government. Such attacks on activists and journalists have had a chilling effect on speech. As one activist told Human Rights Watch:

It’s made me more cautious. I don’t like to go out alone at night. It’s made me more paranoid.… It’s more problematic because, thinking about the impact it would have on my family or people close to me, rather than myself. But I do try to limit self-censoring myself as much as I can, but then there are moments when I do have to go back and change things just because of how that might impact my own safety.

Targeting Political Opposition

The Yameen government has issued decrees that include blocking opposition parties from contesting elections. In February 2018, two Supreme Court justices were arrested on politically motivated charges after rulings that favored the opposition. The authorities have jailed opposition leaders under vaguely defined provisions of the counterterrorism law, restricted protests, and arrested peaceful protesters.

After decades of autocratic rule, in 2008 the Maumoon Abdul Gayoom government amended the constitution to allow for multiparty elections, separation of powers, and media freedom. In November 2008, Mohamed Nasheed of the opposition Maldivian Democratic Party defeated Gayoom and was inaugurated as the country’s first democratically elected leader. Nasheed was forced out of office in February 2012 after opposition protests. In elections in September 2013, Nasheed won more votes, but did not have an absolute majority. The Supreme Court, in a controversial decision, annulled the results of the first round of elections, prompting a second election. The results were similar to the annulled elections, with Nasheed still receiving the most votes but not an absolute majority. This led to a runoff between Nasheed and Yameen, who had the second highest number of votes. In the runoff, Yameen narrowly beat Nasheed.

The government launched criminal proceedings against Nasheed and arrested him in February 2015, denying him access to legal counsel. In March, a three-judge bench unanimously found Nasheed guilty on terrorism charges and sentenced him to 13 years in prison. Under international pressure, Nasheed was granted permission to travel to the United Kingdom for spinal surgery in January 2016. He has since remained in exile, while his political supporters and party members have been repeatedly targeted.

In February 2018, President Yameen declared a state of emergency to annul a Supreme Court ruling that quashed the convictions of nine opposition leaders, including Nasheed. In May, the Election Commission announced that it would nullify any primary results in which the nominee failed to meet the qualifications for president, including those convicted of criminal offenses. Nasheed, who was convicted in 2015, stepped down as a presidential candidate.

During the 45-day state of emergency, Yameen’s administration arrested former President Gayoom, the chief justice and another justice of the Supreme Court, and a court administrator. The crackdown resulted in considerable international criticism of the government. The United Nations high commissioner for human rights, Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, declared that Yameen’s actions were “tantamount to an all-out assault on democracy.”

During and after the state of emergency, the government used the Anti-Terrorism Act of 2015, with its overly broad and ambiguous provisions, to prosecute acts of political dissent. The law includes as acts of terrorism “disrupting public services” for the purpose of “exerting an undesirable influence on the government or the state,” a definition that could apply to protests. Of the scores of opposition figures and activists detained during the state of emergency in 2018, most were charged with committing “acts of terrorism.”

In 2015, hundreds were arrested after a May Day protest. The Human Rights Commission of the Maldives received complaints of police brutality and beatings in custody. While no police officer was prosecuted, protesters faced serious charges. For instance, five men and a woman were convicted of assault with a dangerous weapon. While some of those accused had beaten a police officer, others were convicted because they had thrown water and coke bottles.

In addition, the government has used the Freedom of Peaceful Assembly Act of 2013, which severely restricts citizens’ rights to hold protests or gather for rallies or other political events. Police have sought to limit speech and expression by arresting and questioning individuals who participate in opposition protests, releasing them after many hours or longer. A journalist described one such protest to Human Rights Watch:

We sat there—the police told us to go behind the barricades but they kept pushing the barricades until they were behind us. Then they arrested us for crossing the barricades. They used pepper spray in our faces. They took us to the Atholhuvehi police detention. All the women got strip searched twice—they said it was the “normal” procedure. We were held until about 10 p.m. We think we were released because of the uproar over all the arrests.

The government has also misused provisions of the penal code to charge political activists and journalists with “obstruction of justice” and other vaguely worded offenses. The penal code prohibits public statements that are contrary to government policy and Islam, threaten the public order, or are libelous. Journalists and publishers are compelled to practice self-censorship.

The crackdown by the Yameen government has already drawn international censure. In February 2018, after the state of emergency was declared, the UN Security Council was briefed on the situation, while the United States State Department called on the Maldives government to respect its “international human rights obligations and commitments.”

In July 2018, the European Union warned that it could use targeted sanctions, including a travel ban or asset freeze, against individuals and entities responsible for undermining the rule of law, committing human rights violations, or obstructing an inclusive political solution. India urged the Maldives government “to return to the path of democracy and ensure credible restoration of the political process and the rule of law before the elections are conducted.”

Donors and other countries with influence in the Maldives should encourage President Yameen’s government to change its autocratic course, create an environment that will ensure free and fair participation in the upcoming elections, uphold protections provided under the constitution including freedom of expression, and respect the fundamental rights of all people in the Maldives under international human rights law.

Key Recommendations

- Drop all prosecutions and release anyone being held for the peaceful exercise of their basic rights, including the right to peaceful expression and assembly. This includes all criminal investigations and terrorism charges brought against individuals for their criticism of government officials, institutions, or judicial decisions.

- Immediately and unconditionally release Chief Justice Abdulla Saeed, Justice Ali Hameed, and others currently in custody who were detained during the state of emergency for exercising their rights to peaceful assembly and freedom of expression.

- Implement the Supreme Court ruling of February 1, 2018, to annul the criminal cases against the nine opposition leaders, and release any of the nine currently in custody.

- End politically motivated detentions of opposition members, journalists, and activists.

Methodology

This report is based on field research and interviews conducted in the Maldives in June and July 2018, and on interviews with Maldivians and other informed sources living outside the Maldives.

Human Rights Watch interviewed victims of rights violations and their families, journalists, bloggers, social media activists, human rights activists, opposition party leaders and members, lawyers, and judges. Human Rights Watch also reviewed legal documents related to cases brought against opposition activists currently in detention. We also examined social media content that led to threats against journalists and activists.

Most interviews were conducted in person, but several were conducted by phone or email. We have withheld the names and other details of the interviewees to safeguard their identity. We paid no remuneration or other inducement to victims and witnesses who spoke with us.

In July 2018, we provided a summary of the findings to the government of the Maldives, but have received no response at time of writing.

I. A Troubled History

After gaining independence in 1965 following 78 years as a British protectorate, the Maldives endured decades of political repression. This eased in 2008 when the constitution was amended to allow for multiparty elections, separation of powers, and freedom of the press.

In 1968, the Maldives elected Ibrahim Nasir by referendum in the 54-member unicameral parliament, the People’s Majlis. There was no opposing candidate. When Nasir retired under pressure in 1978 amid charges of corruption, his chief rival, Maumoon Abdul Gayoom, became president after parliament approved his candidacy, a decision confirmed by public referendum. This system returned Gayoom to office five times until 2008. As the Economic and Political Weekly noted in a 2008 editorial, Gayoom’s 30-year “iron-fisted rule” was marked by “cronyism, nepotism, corruption, and stifling of any political dissent.”[1]

In September 2003, the death of an inmate in Maafushi Prison at the hands of prison officers sparked unprecedented protests in Malé. While Gayoom ordered riot police to quell the protests and declared a state of emergency, local and external pressure continued to mount. Violent protests erupted again in August 2004, initially sparked by the detention of several political activists. The demonstrations intensified when police baton-charged and beat protesters. An economic downturn made worse by the December 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami fueled more protests.

Popular pressure for reform mounted, compelling Gayoom to announce a roadmap for reforms, including the promise of a new constitution, establishment of a human rights commission, and lifting of the prohibition on political parties.[2] However, it was not until 2008 that President Gayoom ratified a new constitution that paved the way for the first multiparty presidential elections. The new constitution also mandated a separation of powers between the branches of state, establishing an independent judiciary and freeing the legislature from executive control.

Precarious Transition

In November 2008, opposition leader Mohamed Nasheed of the Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP) defeated President Gayoom of the Dhivehi Rayyithunge Party (DRP), winning 54 percent of the vote.[3] Nasheed—who had previously been imprisoned 23 times under Gayoom and subjected to torture and 18 months of solitary confinement after publishing articles critical of the president—was inaugurated as the country’s first directly elected leader in relatively free and fair elections.[4]

However, with more freedom under the new constitution, religious scholars who were formerly suppressed began to propagate narrow interpretations of Islam.[5] This was exacerbated by the fact that when Nasheed came to power, he was in a coalition with the religious conservative Adhaalath Party. The Adhaalath Party publicly undermined Nasheed as sacrilegious, using the term laadheenee (secular) against him and his supporters.[6] In May 2011, Gayoom’s DRP, in alliance with other opposition parties, launched a series of protests against the Nasheed government. Nasheed stepped down on February 7, 2012. He claimed he had been forced out, and MDP party officials called the event a coup.[7]

Vice President Mohammed Waheed Hassan of the Gaumee Itthihaad Party was sworn in as president. MDP called for early elections, but as opposition protests mounted, Waheed called for elections to be held the following year. In the first round of voting on September 7, 2013, Nasheed received 45 percent of the vote while his opponent, Abdulla Yameen Abdul Gayoom of the Progressive Party of Maldives (PPM), received 25 percent.[8] Incumbent President Waheed came in last. With no clear majority, a second round runoff was required under the constitution, which was scheduled for September 27, 2013.[9] However, in a controversial 4-3 vote on September 27, the Supreme Court cancelled the runoff and annulled the first round results.[10] In the second round, Yameen won by 51 percent to Nasheed’s 49 percent—a difference of just over 6,000 votes. The MDP initially disputed the results, but, saying he wanted to avoid any violence, Nasheed conceded.[11]

Political Crackdown

On taking office, President Yameen’s government expanded the use of broad and vaguely worded laws to arrest, intimidate, and imprison its critics. Among these are counterterrorism laws widely used against opposition activists and politicians; anti-defamation laws used against the media and social media activists who criticize the president or his policies; and restrictions on assembly that prohibit or severely limit peaceful rallies and protests.

On February 22, 2015, the Maldives Criminal Court issued a warrant for Naheed’s arrest. He was physically dragged to court and was not permitted to consult a lawyer.[12] On March 13, he was found guilty of terrorism in a unanimous verdict by the three-judge bench and sentenced to 13 years in prison.[13]

Following an alleged assassination attempt against the president in which a device exploded on a speedboat he was traveling on, Yameen declared a state of emergency on November 4, 2015.[14] He lifted it a week later, following international condemnation and concerns about its potential impact on tourism.[15] Under international pressure, on January 16, 2016, Nasheed was granted permission to leave for the UK to undergo spinal surgery “under the condition to serve the remainder of the sentence upon return to the Maldives after surgery.”[16] In May 2016, the UK government granted Nasheed refugee status.[17]

Since then, Nasheed has effectively campaigned from London and, more recently, from the MDP’s headquarters in Colombo, Sri Lanka. In August 2016, he accused President Yameen of corruption, saying that as head of a state-owned company, Yameen had sold nearly US$300 million worth of oil to Myanmar’s military junta, circumventing international EU and US sanctions.[18] The situation continued to deteriorate through 2018, as the president’s office increasingly interfered in legislative and judicial affairs. When the Supreme Court was hearing an opposition plea seeking his removal from power, Yameen said he “had a duty to interfere in the running of the court if it was losing its way.”[19]

On February 1, 2018, the Supreme Court ordered the immediate release of nine political prisoners, ruling that their trials had violated the constitution and international law, and were “politically motivated.”[20] President Yameen denounced the ruling as “illegal,” and on February 5 declared a 15-day state of emergency “to hold these justices accountable.”[21] He stated that the Supreme Court had “attempted to subvert the government and hold hostage the work of the government by obstructing the work of the executive.”[22] The emergency decree suspended several constitutional protections, banned public assemblies, and granted security forces sweeping powers to arrest and detain. Supreme Court Chief Justice Abdulla Saeed and Justice Ali Hameed were arrested the next day. Former President Maumoon Abdul Gayoom, Yameen’s half-brother, was also arrested. The remaining three Supreme Court justices reversed the ruling on the opposition leaders, stating they were doing so “in light of the concerns raised by the president.”[23]

The declaration of emergency was widely condemned internationally.[24] The UN high commissioner for human rights, Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, stated that “what is happening now is tantamount to an all-out assault on democracy.”[25] Yameen, however, extended the state of emergency on February 20.[26] He finally lifted it on March 22, after several opposition leaders had been arrested.[27]

On May 20, the Election Commission announced that it would nullify any primary results in which the nominee failed to meet the qualifications for president outlined in the 2008 constitution. Article 109(f) provides that the president cannot have been sentenced to more than 12 months in prison for a criminal offense within the past three years. Because Nasheed was sentenced to 13 years in prison on terrorism charges in 2015, he is not eligible to run. In effect, the commission left only President Yameen eligible to contest the elections.[28]

II. International and Domestic Legal Standards

The Maldives is party to the core international human rights treaties.[29] The current situation in the country has raised particular concerns about the rights to freedom of expression, association, peaceful assembly, and political participation.

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which the Maldives has ratified, provides in article 19 that everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression, including the freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive, and impart information and ideas through any media, regardless of frontiers.[30]

The ICCPR further provides in article 21 that “everyone has the right to peaceful assembly,” and in article 22 that “everyone has the right to freedom of association with others.”[31] Article 25 states that “every citizen shall have the right and the opportunity … to vote and to be elected at genuine periodic elections” that reflect the will of the voters.[32] The UN Human Rights Committee, the independent body of experts that monitors state compliance with the ICCPR, has stressed the importance of freedom of expression in a democracy:

The free communication of information and ideas about public and political issues between citizens, candidates and elected representatives is essential. This implies a free press and other media able to comment on public issues without censorship or restraint and to inform public opinion.[33]

Under international law, the right to freedom of expression is not absolute. Given its paramount importance in any democratic society, however, the Human Rights Committee has held that any restriction on the exercise of this right must meet a strict three-part test. Such a restriction must be “provided by law”; be imposed for the purpose of safeguarding respect for the rights or reputations of others, or the protection of national security, public order, public health, or morals; and be necessary to achieve that goal.[34]

These liberties are recognized in the 2008 Maldives Constitution. Article 27 of the constitution provides that “everyone has the right to freedom of thought and the freedom to communicate opinions and expression in a manner that is not contrary to any tenet of Islam.” Article 28 provides that “everyone has the right to freedom of the press, and other means of communication, including the right to espouse, disseminate and publish news, information, views and ideas. No person shall be compelled to disclose the source of any information that is espoused, disseminated or published by that person.”[35] Article 30(a) provides that “every citizen has the right to establish and to participate in the activities of political parties,” and article 32 provides that “everyone has the right to freedom of peaceful assembly without prior permission of the State.”[36]

III. Criminalizing Free Expression

Following 30 years of severe restrictions on freedom of expression and media under President Gayoom, the 2008 constitution sought to reverse this pattern by codifying media freedom and freedom of expression in a new bill of rights. Article 28 of the constitution states:

Everyone has the right to freedom of the press, and other means of communication including the right to espouse, disseminate and publish news, information, views and ideas. No person shall be compelled to disclose the source of any information that is espoused, disseminated or published by that person.[37]

However, journalists in the Maldives have faced growing harassment and threats, creating an environment of fear and self-censorship among the press.[38] There has also been a rise in violent attacks on journalists, most notably the near-fatal stabbing of Ismail Hilath Rasheed in 2012; the disappearance of Maldives Independent journalist Ahmed Rilwan in August 2014; and the murder of blogger Yameen Rasheed in April 2017. Other events and policies that have threatened media freedom in the Maldives include cyber-attacks against media outlets and the use of vaguely formulated offenses in laws such as “obstructing the discharge of police duties” against journalists.[39]

Anti-Defamation and Freedom of Expression Act

The greatest threat to media freedom and freedom of expression in recent years is the Anti-Defamation and Freedom of Expression Act, which President Yameen signed into law on August 11, 2016.[40] The law, better known as the Defamation Act, criminalizes “defamatory” speech and action as well as comments against “any tenet of Islam” or comments that “threaten national security” or “contradict general social norms.”[41]

Human Rights Watch believes that criminal defamation laws should be abolished, as criminal penalties are always disproportionate punishments for reputational harm and infringe on peaceful expression. Criminal defamation laws are open to easy abuse, resulting in very harsh consequences, including imprisonment. As repeal of criminal defamation laws in an increasing number of countries shows, such laws are not necessary for the purpose of protecting reputations, particularly of government officials.

The Defamation Act came into effect against the backdrop of the state-owned Maldives Marketing and Public Relations Corporation (MMPRC) corruption scandal involving the embezzlement of approximately US$84 million through the sale and lease of islands.[42] Media outlets, especially those aligned with the opposition, published allegations that public officials in the government and opposition had benefited from the embezzlement scheme.[43] Instead of investigating the allegations, the Yameen government arrested former Bank of Maldives branch manager Gasim Abdul Kareem, who had helped expose the scam. He was convicted in a closed trial of leaking confidential client data and sentenced to eight months and 12 days in prison, but was released for time served.[44]

The 2016 law criminalizes defamation and imposes hefty fines for news outlets, journalists, or individuals who are found guilty. The fines range from 50,000 to 2 million Maldivian rufiyaa (MVR) (US$3,200 to $130,000) for media outlets, and from MVR50,000 to 150,000 ($3,200 to $9,600) for individual journalists. Those convicted may appeal only after first paying the fine. Media outlets that fail to pay the fines can have their licenses suspended or revoked; journalists who fail to pay face prison terms of between three and six months. The evidentiary burden lies with the accused, and journalists may have to reveal their sources in order to prove the truth behind any claims made, which directly contravenes article 28 of the constitution. Broadcasters have been charged for things said by a third person in a live broadcast.[45] The broad and vague provisions of the law give wide discretion to the authorities to target media outlets and journalists who are critical of the government.[46]

Arbitrary Rulings by the Maldives Broadcasting Commission

The Defamation Act empowers the Maldives Broadcasting Commission (MBC) and the Maldives Media Council (MMC) as the principal authorities to receive complaints, investigate them, and act against media outlets and journalists in cases of defamation allegations. The MBC is the regulatory body for all broadcast media in the country, while the MMC is the regulatory body concerned with print and online media.

Membership in the MBC is decided by parliament, on recommendation of the president, whereas those working in print and online media vote for members of the MMC, who are themselves journalists working in print and online media. The difference in mandate, composition, and method of appointment to both the MBC and MMC is highly significant, since only broadcast media have been fined under the act at time of writing. There is a disparity even among cases against broadcasters. The only time the state broadcaster, Public Service Media, was charged, it was fined by a much smaller amount than opposition-aligned broadcasters.[47]

In addition, article 27 of the act allows the MBC to investigate cases of libel of its own accord if it so chooses. In 2017, the MBC fined MediaNet, a cable TV service provider, MVR500,000 ($32,000) for not blocking broadcast of an Al Jazeera documentary, “Stealing Paradise,” which exposed systematic corruption, abuse of power, and criminal activities at the highest levels of the Maldives government. In addition to the fine, the MBC ordered MediaNet to issue a public apology for broadcasting content that “threatened national security.”[48] Zaheena Rasheed, an editor at the Maldives Independent who was interviewed on camera as a source for the documentary, had to leave the Maldives out of fear of arrest or violence after receiving threats.[49]

The defamation law has been repeatedly used in politically motivated cases to target Raajje TV, among the largest private broadcasters in the Maldives and one sympathetic to former President Nasheed and his party. According to the chief operating officer of Raajje TV, Hussain Fiyaz Moosa, the MBC has fined Raajje TV multiple times under the 2016 law for a total of MVR1.7 million ($110,000).[50]

In one case in April 2017, MBC fined Raajje TV MVR1 million ($65,000) for airing a speech at an opposition rally in October 2016 that was deemed defamatory toward President Yameen because it accused him of corruption and of using public funds for personal gain.[51] In a statement emailed to the Committee to Protect Journalists, Raajje TV described the actions as “politically motivated and with the aim of muzzling free media in the Maldives.”[52] In February 2018, Raajje TV said that it was suspending its regular broadcast “amid continued harassment, threats and intimidations,” including arson attacks and threats of violence against its staff.[53] Three Raajje TV journalists were arrested after an anti-government protest on March 16. In April, Raajje TV said that they had credible information a criminal gang had been paid by ruling party politicians to attack Chief Operating Officer Fiyaz.[54]

After the government declared a state of emergency in February 2018, the MBC warned media stations they could face closure if they were deemed “a threat to national security, incited unrest with false information or endangered the public interest.”[55]

Counterterrorism Laws

Human Rights Watch has found that national counterterrorism laws frequently contain legal definitions of terrorism that are overbroad and vague. As a basic legal principle, such laws fail to give reasonable notice of what actions are covered. Many are so broad that they cover common crimes that should not reasonably be deemed terrorism or acts that should not be considered crimes at all. Their scope leaves them susceptible to arbitrary and discriminatory enforcement by the authorities—often against religious or ethnic communities, political parties, or other groups.[56]

In October 2015, the government enacted the Anti-Terrorism Act in the face of widespread criticism from the political opposition and international observers. The law lays out a broad definition of terrorist activities and specifies that the conduct of these activities shall be construed as terrorism if carried out with the purpose of “negatively influencing the government or state” or “illegally promoting religious or political views.” The opposition argued that the law, with its broad stipulations, would be used to stifle and criminalize opposition activities.[57]

The opposition had reason for concern. Prior to enacting the 2015 law, the government had used the Prevention of Terrorism Act of 1990 to prosecute opposition leaders. In the most well-known case, the government led by President Waheed initiated a case of terrorism against former President Mohamed Nasheed, shortly after he resigned from office, for the arrest of then-Criminal Court Judge Abdulla Mohamed in 2012. The government alleged that the arrest was an act of kidnapping, which it construed as terrorism under the 1990 law.[58] In February 2015, under President Yameen, the government arrested Nasheed on terrorism charges. After a brief closed-door trial at which he was not permitted a defense counsel, Nasheed was convicted on March 13 and sentenced to 13 years in prison, a decision the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights called “vastly unfair, arbitrary and disproportionate.”[59]

In 2016, the leader of the Adhaalath Party, Sheikh Imran Abdulla, was also convicted of terrorism. A political ally of President Yameen, the Adhaalath Party broke away in 2015. Together with MDP leaders, Imran joined an anti-government protest held on May Day of 2015. Although Imran called for nonviolent protests, the court ruled that though his speech he had “incited violence and struck fear in the hearts of the people.”[60] Imran was convicted of terrorism and sentenced to 12 years in prison.[61]

The Anti-Terrorism Act of 2015 defines the crime of “encouraging terrorism,” an act that carries a prison sentence of between 10 to 15 years, as “a speech or statement perceived by the public as encouragement of terrorism.” The law includes as acts of terrorism “disrupting public services” for the purpose of “exerting an undesirable influence on the government or the state,” a definition that could apply to street protests. After protests when President Yameen declared a state of emergency in February 2018, scores of demonstrators were charged under the Anti-Terrorism Act.

The law was also used to prosecute the two Supreme Court justices out of the five who had unanimously ruled in favor of the opposition in the February 1 ruling, as well as former President Gayoom. The government charged at least six other opposition figures, including members of parliament and a former police commissioner.[62]

Penal Code

The government has used a number of other provisions in criminal law to suppress dissent.[63] Section 530 of the penal code criminalizes the obstruction of justice, while section 532 is related to resisting or obstructing a law enforcement officer or custodial officer. Section 533 covers the obstruction of administration of law or other government function, and section 610 deals with rioting and forceful overthrow of the government.[64] The police and courts have used these provisions against opposition activists, journalists, and others to prevent criticism of the government and its policies.[65] A journalist and human rights activist said that he was arrested and charged with “obstruction of justice” for providing assistance to foreign journalists who were producing a report on the Maldives.[66]

In June 2018, former President Gayoom, former Chief Justice Abdulla Saeed, and former Supreme Court Justice Ali Hameed were each sentenced to 19 months in prison under section 530 of the penal code for obstruction of justice.[67] The three were charged for refusing to provide the police with their phones during an investigation into other alleged criminal offenses. The police subsequently charged them with offenses under the Anti-Terrorism Act as well.

IV. Threats and Attacks by Extremist Groups

Extremist groups in the Maldives, often endorsing violent ultra-nationalist or Islamist ideology, have harassed and attacked media outlets and civil society groups. These groups target those who criticize the government on social media, publish material they deem as offensive to Islam, or promote the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people or other political causes the groups oppose. Some groups are affiliated with gangs with reported links to prominent politicians.

Activists and bloggers who have received threats on social media platforms said that the police often fail to respond to their complaints or do so cursorily, even when violent attacks have followed the threats. The most prominent cases in recent years have been that of Ahmed Rilwan, a journalist who was abducted and went missing in August 2014; Yameen Rasheed, a blogger and activist who was stabbed to death in April 2017; and Ismail Hilath Rasheed, who was stabbed and wounded in 2012.

Particularly after 2008, many young activists in the Maldives began using blogs to express their views or discuss a wide range of topics and interests.[68] Poets, photographers, social commenters, artists, and sometimes even politicians have contributed to an internet-based blogging community informally dubbed the “MV Blogosphere.”[69] But the rise of extremist religious groups, coinciding with increasing state censorship, has had a chilling effect on free speech.

On October 1, 2012, Dr. Afrasheem Ali, a member of parliament of the PPM and a religious scholar known for his sermons supporting gender equality and other liberal views, was stabbed to death outside his apartment in Malé.[70] Hussain Humaam Ahmed, a 20-year-old gang member at the time, was convicted and sentenced to death by the Criminal Court in 2014.[71] However, human rights activists have raised concerns about the case, saying that Humaam had a history of mental illness and was not provided with a defense lawyer, while other suspects, including those who had previously threatened Afrasheem, were not properly prosecuted.[72] The Supreme Court upheld the verdict in June 2016, and as of August 2018, Humaam remained on death row.[73]

Ismail Hilath Rasheed

In November 2011, the Ministry of Islamic Affairs ordered the Communications Authority of Maldives (CAM) to shut down a blog for commentary supporting Sufism and LGBT rights. The ministry said that the site contained “anti-Islamic material.”[74] The blogger, Ismail Hilath Rasheed, was editor of the Maldivian newspaper Haveeru.

Hilath had earlier reported that he had received anonymous death threats in March 2011.[75] On December 10, 2011, Hilath organized a rally on religious tolerance during which he was attacked by 10 assailants who threw stones at him, one of which fractured his skull. The police made no arrests, although participants at the rally photographed the attackers.[76]

Instead, a few days after the event, the police arrested Hilath and detained him for nearly a month before releasing him without charge. Hilath continued to receive threats following his release. On the evening of June 5, 2012, unidentified attackers stabbed him in the neck near his house in Malé.[77] The police did not make any arrests, prompting Hilath to allege that political figures were backing those who carried out the attack. In an interview with Minivan News in 2012, he said that his assailants had named three senior political and religious figures in the country and had presented their “compliments.” “I was told by a friend of these gang members that [two of these figures] met this gang and told them to murder me, and that it would not be a sin, and that in fact they would go to heaven because I had blogged about freedom of religion and gay rights.”[78] After the attack, a government official commented that while the government condemned the attack, “Hilath must have known that he had become a target of a few extremists.… We are not a secular country. When you talk about religion there will always be a few people who do not agree.”[79]

On June 8, 2016, Hilath published a blog post saying that it was his last one and he was retiring from public life.

Ahmed Rilwan

Ahmed Rilwan, a journalist with the Maldives Independent and well-known blogger, has been missing since August 8, 2014. He was 28 years old when he was last seen. Rilwan used the Twitter handle @moyameehaa (“madman”) to write about corruption in Maldivian politics and about the connections among politicians, criminal gangs, and Islamist extremist groups operating in the islands. He had received numerous threats via social media.

Rilwan was last seen at about 12:45 a.m. on August 8 at the ferry terminal linking the capital, Malé, to the neighboring island of Hulhumale, where Rilwan lived. Eyewitnesses told police that at about 2 a.m., they saw a man in dark clothes being forced at knifepoint into a red car parked outside Rilwan’s apartment in Hulhumale. Rilwan’s family alleged the police withheld information about the vehicle and the witness reports when they reported Rilwan missing.[80]

In September 2014, the Maldivian Democracy Network, a human rights organization, published findings of an independent investigation into Rilwan’s apparent abduction that identified known members of the Kuda Henveiru gang, which is linked to radical Islamist groups. They identified gang members who had followed Rilwan the evening he went missing and another gang member who owned the car in which Rilwan was reportedly taken.[81] In the weeks after Rilwan went missing, police said they detained five people for questioning, all of whom were released, and one of whom reportedly fled the Maldives shortly thereafter.[82] According to a report by the Bangkok based nongovernmental organization Forum-Asia, the Maldives police did not officially confirm Rilwan as missing until April 2, 2016.[83] In a statement, Chief Inspector Abdulla Satheeh confirmed as “new findings” what the 2014 investigation had found, “that members of Malé’s Kuda Henveiru gang had followed Rilwan for over two hours on the night he went missing.”[84]

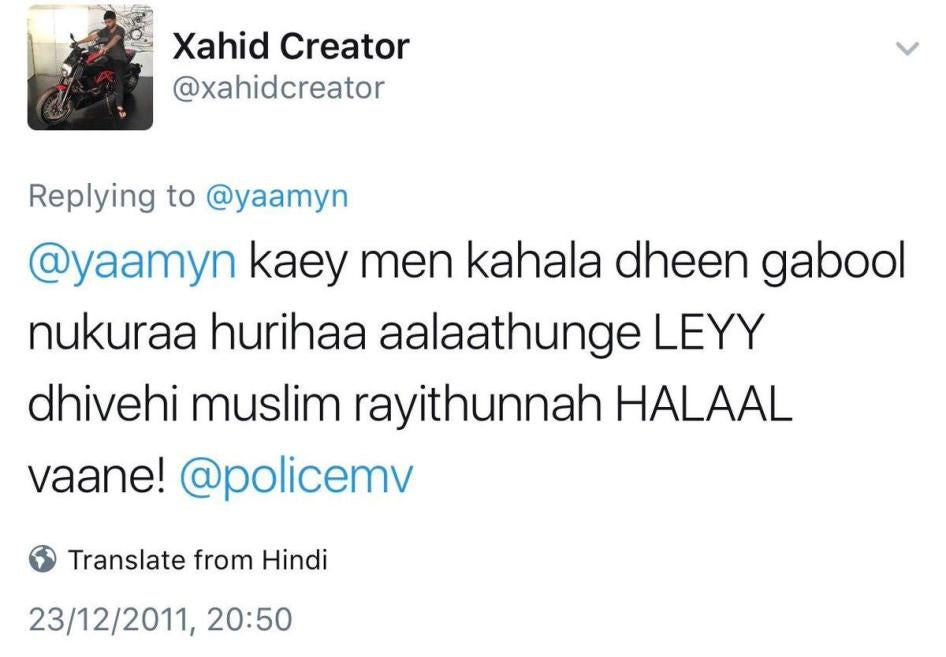

Given the long delays, Rilwan’s colleagues and family have criticized the police for failing to undertake a credible investigation.[85] On February 7, 2017, Rilwan’s family filed a civil claim against the police for refusing to disclose information on Rilwan’s case.[86] According to a lawyer who has been involved in the case, Rilwan had received numerous threats since 2011, some from known Twitter accounts, like @xahidcreator, which has targeted other social media activists. Zaheena Rasheed, who had worked with Rilwan at the Maldives Independent, told Human Rights Watch: “We worked on a story about these gangs shutting down activists on social media platforms. [Before the attack] he had been getting threats accusing him of being anti-Islamic.”[87]

On August 2, after the Maldives criminal court acquitted two men of abducting Rilwan, the judge called the police and prosecution negligent, careless, and said they had failed to conduct a thorough investigation.[88] At a campaign rally on August 7, 2018, President Yameen, who has repeatedly refused to meet with Rilwan’s family, declared that the journalist was dead—a claim he retracted and apologized for after coming under criticism.[89]

Maldives Independent and “Stealing Paradise”

In the weeks following Rilwan’s disappearance, the staff of the Maldives Independent received further threats. On September 25, 2014, a man pounded on the outer office door and then struck a rusty machete into it. The CCTV cameras outside the office captured footage of the man, identified as “a renowned gangster,” minutes before the camera was removed following the attack.[90]

Later that day, Zaheena Rasheed, a colleague of Rilwan’s, received a text message that read: “You will be killed or disappeared next, be careful.”[91] She told Human Rights Watch that a few days after that she was surrounded by a group of men on the street in Malé who said, “Is this the woman we plan to disappear?” Up until then, she said, the threats had been anonymous, but following Rilwan’s disappearance, those sending the threats had grown bolder.[92]

On September 7, 2016, Al Jazeera broadcast “Stealing Paradise,” a documentary that exposed a US$1.5 billion money laundering scheme involving Singaporean and Malaysian businesspeople and senior figures in the Maldives government. Rasheed appears as a source in the documentary. After a member of the governing party warned on state television that contributors to the documentary would be arrested, Rasheed left the country.[93]

Yameen Rasheed

On April 23, 2017, Yameen Rasheed, 29, was found with severe stab wounds in the stairwell of his apartment building in Malé. After police arrived on the scene, they took him to the hospital in the back of a police car, without calling for an ambulance that could have reached the building in minutes due to its proximity to the hospital. He died shortly after being taken to the hospital.[94]

Yameen, as he was known publicly, was a prominent blogger and social media activist known for his satirical commentaries on Twitter and his blog, The Daily Panic. His ridiculing of the hypocrisy of public figures appealed to a growing following, while attracting the spite of those he was criticizing, including politicians, religious authorities, and extremists. In 2010, Yameen began receiving threats through comments on his blog as well as his social media accounts. In a blog post made on December 8, 2010, he commented on a string of menacing comments left by someone whose IP address he traced to the police.[95]

In December 2011, Yameen posted photos on his blog of the mob that threw stones at Hilath’s rally on religious freedom. According to Aisha Rasheed, Yameen’s sister, this is what brought him to the forefront of the extremists’ attention. The messages, primarily written in Dhivehi, threatened Yameen with violence and death.[96] One threat read: “Handhaan kuraathi [remember] your days are numbered.”[97] While some threats came anonymously, others were from known persons, some even holding high-level positions in the government or ruling party.

For instance, a council member of the ruling Progressive Party of Maldives, who allegedly goes by the screen name @xahidcreator on Twitter, openly and regularly trolled Yameen on the platform.[98] In one of many tweets, which are now deleted, the council member had written that the blood of disbelievers such as Yameen would be “halal” (acceptable under Islamic law) for Maldivian Muslim citizens.

In another tweet directed at Yameen, the council member wrote, “I did say it will happen, before Hilath was taken care of,” and proceeded to thank the police for protecting Muslim Maldivians. The tweet is in apparent reference to the attack on Hilath, for which the police made no arrests.[99]

Yameen was also targeted by an activist on Facebook who goes by the name Siru Arts. The page regularly posts content that promotes Islamist militancy, and brands Maldivian human rights defenders by the derogatory term laadheenee (secular).[100]

Since August 2014, Yameen had led the campaign to find the truth about what had happened to the missing journalist Ahmed Rilwan, writing frequently about the government’s failure to conduct a thorough investigation. He received threats in response to these blog posts as well.

In September 2014, Yameen filed an official complaint about the threats with the police, who did not respond to him or follow up with him on the complaint. Yameen continued to tag the police on Twitter about the threats as he received them, reminding them about the complaint that he filed.[101] According to his family, it was not until December 2016 that the police finally said they were investigating two specific text messages Yameen had received from the same number, which they said they were ultimately unable to trace.[102]

The police have argued that they had been investigating the threats.[103] According to Yameen’s family, however, the police pursued only one angle—that the crime was perpetrated by religious extremists, rather than by gangs with links to political figures. Following this line of investigation, the police reportedly asked Yameen’s colleagues at work if he had talked to them about religion and, in one instance, asked a colleague who wore a burqa if Yameen had ever tried to convince her to remove it.[104] In August 2017, police stated that a group of young men, unaffiliated with any organization, had killed Yameen. Police also said that the killing was not politically motivated, but carried out by religious extremists.

By June 2017, the police had arrested eight suspects, and the trial of six of the eight suspects began in September.[105] The hearings have all been held behind closed doors. The prosecutor general’s office told Yameen’s family that the case involved a number of secret witnesses, whose identities had to be protected.[106] On June 7, 2018, the court scheduled the first open hearing in the case, but abruptly canceled it at the request of defense lawyers.[107] After two further cancellations, the first open hearing was held on July 30.[108]

Yameen’s family filed a negligence suit against the police at the Civil Court for failing to follow up on leads from the threats Yameen had received.[109] However, the court declared that the case was out of its jurisdiction and that it should have been filed at the National Integrity Commission.[110] The family has since appealed the case at the High Court, but apart from a preliminary hearing, no progress has been made.

Shahindha Ismail

Shahindha Ismail is the founder and executive director of the Maldivian Democracy Network (MDN), the first human rights organization in the Maldives. On December 20, 2017, President Yameen said in a public speech that because Islam was the only religion in the Maldives, there is no room for any other religion. Ismail responded on Twitter: “Religions other than Islam exist in the world because Allah has made it possible. No other religion would exist otherwise, is it not?”

On December 28, the news website Vaguthu Online accused Ismail of advocating for other religions in the Maldives and branded her an apostate. After the article appeared on Vaguthu Online, Ismail received death threats via Twitter and Facebook calling for violence against her, including one that claimed to be “one of hundreds who will cut people like that to pieces.”[111] She said that those threatening her have also threatened violence against her daughter. She asked for and received police protection, but gave it up after the police repeatedly questioned her about whom she was meeting.[112]

Following the publication of the original article on Vaguthu Online, the Ministry of Islamic Affairs issued a statement urging the citizens of the Maldives to refrain from making statements in support of any religion other than Islam.[113] The police then launched an investigation against Ismail under the Religious Unity Act, which criminalizes actions that “may lead to religious conflict in the Maldives,” and carries a prison sentence of up to five years.

A Chilling Effect

Various journalists and writers told Human Rights Watch that the spate of attacks and threats had led them to change how they write, or, in some cases, to stop blogging altogether. One activist who is active on social media said:

If I post anything about Yameen or Rilwan they will basically try to downplay its importance by calling them as deserving of what happened because they were mocking religion, and if I was promoting them, that would be the same fate that I would face as well.… It’s made me more cautious. I don’t like to go out alone at night. It’s made me more paranoid.… It’s more problematic because, thinking about the impact it would have on my family or people close to me, rather than myself. But I do try to limit self-censoring myself as much as I can, but then there are moments when I do have to go back and change things just because of how that might impact my own safety.[114]

Another independent journalist who had a blog described the threats he received:

In 2016, I started a blog and posted on Twitter. On March 8, 2016, there was a women’s rights march in Malé. I was holding a poster that said that 90 percent of those flogged for zina [sex outside of marriage] are women. After that protest, I started being trolled by the same people who threatened Shahindha. This happened to me and several others. The troll accused me of being against Islam—it happened a lot immediately after the protest, and still happens. I have written a few articles about Yameen, but it’s too dangerous to publish them. Of my friends, 20 out of 30 have changed their activities. One is completely off social media.[115]

The threats have included abductions. One activist said that he was aware of four to five abductions of activists who had fallen afoul of Islamist groups. “This is not even done privately—it happens from cafés, from the street. Sometimes they force the person to say his shahada to prove he is a Muslim.”[116] Another journalist who had been detained on multiple occasions said that he had become more cautious about what he wrote since he and his wife had a child. “I have to think about my family and what would happen to them if I am detained,” he said.[117]

A lawyer who has defended activists and opposition members said that after one of Mohamed Nasheed’s lawyers, Mahfooz Saeed, was stabbed in the head as he headed home on September 4, 2015, she and other lawyers have taken greater precautions. “We don’t walk home alone at night, or we text each other when we reach home,” she said.[118]

An activist who no longer lives in the Maldives said that he does not feel safe because these threats are made by people with political protection. “There is really no difference between these gangs, trolls, and others that make threats,” he said. “I was followed. I was threatened. And I have no faith that there will be action because I believe all this is happening with the full knowledge of this government.”[119]

V. Political Participation and Freedom of Assembly

Before 2008, Maldivians did not have a constitutional right to freedom of assembly. The mass protests that erupted in 2004 eventually led to political reforms, the first multiparty democratic elections, and the ratification of the 2008 constitution. By early 2012, however, after then-President Mohamed Nasheed was removed from office, authorities began tightening their grip in ways reminiscent of Maumoon Abdul Gayoom’s 30-year authoritarian rule. Although the 2008 constitution provides for “freedom of peaceful assembly without prior permission of the State,” subsequent laws have curtailed the right.

Freedom of Peaceful Assembly Act

The Freedom of Peaceful Assembly Act of 2013 mandates organizers of assemblies to inform the police of any planned gatherings, and gives the police wide discretion in granting permission.[120] For instance, under article 33 of the law, police may broadly restrict the right to assembly if the gathering poses a threat to national security, or to maintain public safety, establish public order in accordance with legislation, protect “public morals,” or protect the rights and freedoms of individuals.

The act also allows police to restrict demonstrations to designated areas and limits access to journalists, including when police are dispersing a protest. The Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative criticized these restrictions, noting that “giving the police the discretion to establish a perimeter from which the media can report on assemblies and protests undermines its ability to serve as an effective watchdog on the content, conduct, and dispersal of protests.”[121] The law also sets proximity restrictions on certain offices and buildings, such as the police and military headquarters, president’s office, schools, mosques, and courts, which, in a small, densely packed island such as Malé, means that there are very few locations where people can gather. The law also prohibits any protests in airports, ports, and tourist resorts, thus restricting the rights of tourist resort employees to strike and curtailing their already minimal bargaining power with employers.[122]

In 2016, the government amended the law to impose further restrictions. The amendments require that any gatherings held in Malé must obtain prior permission from the police, unless the gathering is held at a location pre-approved by the Ministry of Home Affairs, limited to one closed-off location in the city. This, for all practical purposes, has rendered the right to freedom of assembly meaningless under the law.[123] Throughout 2017, police dispersed dozens of protests and political gatherings on the grounds that they violated the law.

Arbitrary Arrest, Detention during Protests

In the largest opposition protest to take place in Malé since 2004, on May 1, 2015, some 20,000 protesters from outlying Maldivian islands converged on the capital to protest against government “tyranny and injustice” and call for the release of former President Nasheed and other members of the opposition who had been detained.[124] The police arrested at least 192 people, including three opposition leaders, and used pepper spray and teargas against the protesters.[125] One activist described how the police broke up the protest:

The police started driving cars into groups of protesters to scare everyone.

I was arrested around 7 p.m. They put me in cuffs and then pepper sprayed my face. For a few hours I could barely open my eyes. They put me in a pickup and hit me with a truncheon on the head and all over my body. I was hit about 15 times, and they hit the others in the pickup as well. The Human Rights Commission visited the prison to check on us and said they would investigate my case. They saw I had been beaten. But nothing happened.[126]

In the first few hours after the protest, 17 detainees were released, and another 50 were released a week later. Some 125 detainees were held without charge more than two weeks after the protests.[127] While no police officer was prosecuted, protesters faced serious charges. For instance, five men and a woman were convicted of assault using a dangerous weapon. While some of those accused had beaten a police officer, others were convicted because they had thrown water and coke bottles.[128] They were later granted clemency.

On April 3, 2016, journalists from various media organizations held a peaceful demonstration outside the president’s office to protest media restrictions, the proposed criminal defamation law, and the failure to locate missing journalist Ahmed Rilwan.[129] According to activists, the police sprayed protesters with pepper spray and beat them with batons.[130] Nineteen journalists were arrested.[131] The police allegedly moved their barricade behind the protesters, and then arrested them on allegations of breaking the police barricade.

The arrest included seven female journalists who were strip searched twice while in custody before being released without charge later that day. One of them described what happened:

We were protesting outside the president’s office. The signing of the bill was imminent. We sat there—the police told us to go behind the barricades, but they kept pushing the barricades until they were behind us. Then they arrested us for crossing the barricades. They used pepper spray in our faces. They took us to the Atholhuvehi police detention. All the women got strip searched twice—they said it was the “normal” procedure. We were held until about 10 p.m. We think we were released because of the uproar over all the arrests.[132]

Through July 2016, the Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP) and other opposition parties organized frequent protests in Malé against President Yameen’s government. In August 2016, as the government moved forward with plans to pass the Anti-Defamation and Freedom of Expression Act, local media organizations mobilized against it, calling themselves the “Defence of Article 27 Movement,” which gained considerable support on social media.

Following the declaration of a state of emergency on February 5, 2018, protests again broke out in Malé. Police were granted sweeping powers of arrest, and several hundred protesters and opposition party members were detained over the following days and weeks.

Human Rights Watch interviewed several members of the opposition MDP who described increased surveillance and threats of arrest. One of them said he had been an MDP youth wing member and quite active on social media criticizing the government, particularly on corruption issues. On February 8, he joined 50 others at a protest during the state of emergency. He said that special operations police officers arrested several protesters. He, however, managed to get away and continued to use social media to organize other events and encourage people to protest. He was eventually discovered and arrested on March 8. The police confiscated his cellphone and demanded his passcode, which he refused to provide. He was held at Dhoonidhoo detention center for 11 days. He said he was questioned about the protests and about his Facebook and Twitter posts:

The police wanted to know the source of things I had posted. I told them I just pasted [from others’ posts]. They said it was “terrorism,” but I have no idea if that was the actual charge. But when it’s convenient for them they can use it.[133]

Political Parties Act

The Political Parties Act, enacted in 2013, severely limits space for political pluralism in the country.[134] The law imposes a minimum membership of 10,000 for all political parties operating in the country.

In September 2013, the Supreme Court ruled that the restriction was against the constitutional freedom to form and join political parties, as well as internationally accepted norms.[135] In 2015, an amendment was made to the Political Parties Act, which dissolved parties with membership under 3,000 members, and stipulated that public funding would only be provided for parties with memberships exceeding 10,000.[136] With this amendment, of the 16 political parties that were registered at the time, 10 were dissolved.[137] The minimum requirement for eligibility for public funding also meant that smaller parties faced greater hurdles in conducting their activities.

The 2013 law also included a requirement that party members have their fingerprints on file at the Election Commission. The requirement did not affect the ruling Progressive Party of Maldives (PPM), as it had been submitting forms with fingerprints since its inception. Other parties, including the MDP, were liable to lose membership, unless members were re-registered with their fingerprints.[138] By the time the deadline for re-registering members expired, all major political parties, except for the PPM, had a drastic drop in membership.[139] As parties are given state funding proportionate to their membership, all parties other than PPM suffered in their financial standing, affecting their ability to operate and conduct activities. Opposition political parties have since complained that this has taken a toll on their campaign efforts.[140]

In May 2018, the Maldives Election Commission announced it would reject the presidential candidacy of anyone with a criminal conviction, effectively banning the four main opposition leaders from running.[141] The commission also threatened to dissolve the opposition MDP if its sole candidate, former President Nasheed, contested the party’s May 30 primaries. On June 29, 2018, Nasheed withdrew his name as a potential candidate, and the MDP chose parliamentary group leader Ibrahim Mohamed Solih instead.[142]

VI. Threats to the Judiciary

From independence in 1965 through the 1990s, there was virtually no legal profession in the Maldives and no legal aid. There was no national code of criminal procedure, and most trials were based on confessions obtained through coercion or torture.[143] Prior to 2008, the Maldivian judiciary functioned essentially as a branch of the executive. The president appointed all judges and could dismiss them at will. The 2008 Maldives Constitution for the first time made the judiciary formally independent from the executive.[144]

Politicization of the Judicial Service Commission

The 2008 constitution established the Judicial Service Commission (JSC) to make recommendations on the appointment and removal of judges to all courts including the Supreme Court, investigate complaints against them, and take disciplinary action as warranted. During a transitional two-year period from August 2008 to August 2010, the JSC was to vet and reappoint or dismiss all sitting judges, a process that quickly became politicized. The existing judges had all been handpicked and appointed by Gayoom and remained loyal to him, and because the opposition had a majority in parliament, it controlled the JSC’s composition.

The JSC published evaluation criteria for judges, setting low standards and allowing judges who had been found guilty of misconduct or had pending cases against them to continue to sit on the bench. Disregarding concerns raised by a number of observers, the JSC went ahead with the oath-taking of the judges behind closed doors and instated them as permanent judges.[145] As a result, all but six judges appointed under Gayoom remained in office.[146]

On June 8, 2010, the five members of the transitional Supreme Court serving in this period declared themselves reappointed, setting off a showdown with then-President Nasheed. The government dissolved the bench on August 7, 2010, and then appointed a four-member appellate bench by decree. In response, parliament passed the Judges Act, which established the permanent Supreme Court. The five judges who had been sitting on the transitional bench were appointed to the seven-member permanent bench, with the JSC appointing two additional judges.[147] Thus, despite the creation of a process to vet judges, the same people remained in place. As the UN special rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers observed in 2013: “The 2008 Constitution completely overturned the structure of the judiciary, yet the same people who were in place and in charge, conditioned under a system of patronage, remained in their positions.”[148] Explaining why the judiciary had failed to act as a check on executive power, one former judge said:

It’s because the same people remained. That’s the simple answer to that. The 2008 constitution was a golden opportunity to reform the judiciary, but we lost that opportunity.[149]

On January 12, 2012, President Nasheed ordered the arrest of Abdulla Mohamed, chief judge of the Criminal Court, on the grounds that he had refused to investigate allegations of corruption involving a number of high-ranking politicians. In 2011, the JSC had found Judge Abdulla guilty of misconduct. On appeal, the Civil Court suspended the ruling, and Judge Abdulla was allowed to remain on the bench. The crisis culminated in Nasheed’s resignation on February 7, 2012, after which he was charged with the illegal arrest and detention of Judge Abdulla.

On December 11, 2014, after the Yameen government reduced the size of the Supreme Court bench, the JSC removed Chief Justice Ahmed Faiz and Justice Muthasim Adnan, returning the court to a five-member bench.[150] Faiz and Adnan had written dissenting opinions in several controversial cases, including the decision to annul the first round of presidential elections held in September 2013.[151]

The JSC has continued to function as a highly politicized body. A 2016 Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative report determined that flaws in the commission’s composition impacted its vetting and appointment of judges, resulting in a politicized judiciary. The report found that the Supreme Court failed to guarantee fair trial rights and excessively targeted independent institutions and lawyers.[152]

Following its review in 2015 under the UN Universal Periodic Review (UPR) process, the Maldives accepted recommendations from the UN Human Rights Council to reform the JSC process of selecting and appointing judges, review the oversight body’s composition, and implement recommendations made by the UN special rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers.[153] However, the government has not implemented these changes.[154]

Intimidation of Judges and Lawyers

Lawyers interviewed by Human Rights Watch said the threat of transfer to a remote island is one way the executive keeps judges in check.[155] Many small islands lack good hospitals and schools as well as courtrooms, requiring long commutes and posing extreme difficulties for judges with families.

The judiciary uses the threat of contempt charges and suspension against lawyers who speak against court rulings. Lawyers representing opposition politicians, independent institutions, or activists are more likely to be found in contempt, reflecting the political bias of the court.[156] One judge told Human Rights Watch that court rulings are made under the influence of powerful people, and judges who try to act independently are at risk.[157]

On August 21, 2017, the Department of Judicial Administration, the administrative arm of the Supreme Court, warned lawyers that they could face legal action, including suspension and disbarment, if they criticized or misrepresented judicial rulings in public. On September 10, the Supreme Court suspended 54 lawyers who had attempted to file a petition calling for judicial reform. The lawyers were barred from practicing, pending an investigation for contempt of court, interfering with the independence of the judiciary, and signing an “illegal” document. The 54 lawyers comprised the entire legal teams for prominent opposition politicians and one-third of all licensed private practice lawyers.[158]

One lawyer told Human Rights Watch:

I’ve been suspended four times and summoned twice for contempt. I was summoned because I gave press statement that judges had not been given a chance to make submissions on sentencing. I was given a warning. Then, after the state of emergency was declared in February [2018], I asked how the judge was going to conduct the trial since the Criminal Procedure Code was suspended. I said to the press that he would conduct it arbitrarily. I was accused of offending and demeaning the court and had to apologize. Every time you say something there is always a threat of suspension, always a threat of contempt.[159]

In June 2014, in response to a Supreme Court order, the Home Ministry dissolved the Maldives Bar Association, a privately founded association representing some 900 Maldivian lawyers. The reason given was that the association had failed to change its name after the Supreme Court stated that as a private group, it did not have the legal mandate to represent or speak on behalf of the entire profession. A Home Ministry letter also said the organization had failed to submit an annual report as per regulations.[160]

Both the UN special rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers and the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative have recommended that the Maldives re-establish a bar association to provide “a mechanism of protection for its members against undue interference in their legal work [and] also monitor and report on their members’ conduct, ensuring their accountability and applying disciplinary measures in a fair and consistent manner.”[161] One lawyer explained, “There is really no avenue—we tried three times to establish a bar association, but the Ministry of Home Affairs does not give permission for it.”[162]

February 2018 Arrests of Supreme Court Justices

On February 1, 2018, the Maldives Supreme Court overturned the convictions of nine members of the opposition, including former President Nasheed, who had been sentenced to 13 years in prison on terrorism charges in 2015. The ruling read:

Upon deliberation of the petitions submitted to the Supreme Court in relation to the politically motivated cases based on criminal investigations in violation of the Constitution of Maldives and international human rights treaties to which Maldives is a party, and influencing judges, and in violation of due process, and taking into account of the writ jurisdiction of the Supreme Court, we hereby decide that the abovementioned cases ought to be judicially reevaluated in accordance with law and until a fair retrial, the following named persons shall be released with immediate effect.[163]

The ruling then listed the nine opposition members. After the ruling, Nasheed, who had been granted asylum in the UK, declared he would contest the presidential elections slated for September. President Yameen denounced the ruling as “illegal,” and on February 5 declared a 15-day state of emergency “to hold these justices accountable.”[164]

The decree granted security forces sweeping powers to arrest and detain, and suspended several constitutional protections, including the right of accused to remain silent, the right not to be arbitrarily arrested, and habeas corpus.[165] On February 6, Chief Justice Abdulla Saeed and Justice Ali Hameed were arrested. That same day, the remaining three Supreme Court justices reversed the ruling, stating they were doing so “in light of the concerns raised by the president,” and warned that any criticism of the legitimacy of the Supreme Court would be interpreted as contempt of court.[166]

On June 13, the Maldives Criminal Court sentenced Chief Justice Saeed and Justice Hameed each to 19 months in prison after being found guilty of “obstructing justice” for refusing to hand over their mobile phones to police. In addition, both have been charged with accepting bribes and delivering verdicts according to special interests. On March 10, both were charged under the Anti-Terrorism Act for allegedly attempting to overthrow the government.

Defense lawyers representing former President Gayoom and the two Supreme Court justices have described many procedural irregularities. Gayoom’s lawyer recused himself from the case, citing “grave procedural defects,” as well as the court’s refusal to reschedule hearings despite risks to Gayoom’s health at the time.[167] A second lawyer also walked out of the case in protest of the court’s refusal to slow down the pace of the trial.[168]

In another trial involving the chief justice, held during the 2018 state of emergency, the lawyer, having noted several irregularities with the proceedings, asked the presiding judge if he was going to continue the trial arbitrarily, to which the judge reportedly responded “yes.” The court subsequently suspended the lawyer, former Attorney General Husnu Al Suood, for telling the media that the judge had admitted to conducting an arbitrary hearing.[169]

The defense attorney for Ilham Ahmed, a detained opposition member of parliament, was arrested on suspicion of hiding Ilham’s phone from the police.[170]

Maldives Human Rights Commission

While the Maldives National Human Rights Commission should function as a check on state abuses, it has failed to operate independently from the government.

A national human rights commission was set up following public protests over the deaths of five detainees in police custody in 2003. It was not until 2006 that the parliament formerly mandated the Human Rights Commission of the Maldives (HRCM). However, the commission never established itself as an independent voice for the victims of human rights violations, consistently failing to investigate complaints of abuse filed with it.[171]

The commission nonetheless included criticism of the human rights situation in the country in its submission to the UN Human Rights Council ahead of the second Universal Periodic Review of the Maldives. In response, in September 2014 the Maldives Supreme Court charged all five members of the commission with treason.[172] The court also issued an 11-point guideline to restrict the commission’s engagement with international human rights mechanisms.[173]

Human Rights Watch interviewed a former member of the HRCM who said that the government had made “a deliberate attempt … to ensure that the commissioners are people who they could control.”[174] He said:

The whole purpose of the human rights commission has been to validate what the government is doing, because their silence is what the government uses to justify their actions internationally.… Freedom of religion, the issue of the death penalty, issues related to women, issues relating to the LGBT community—these were things that, even if it was brought up, they were quickly dismissed as not being applicable to the Maldives.… Right now, what’s happening is that the president handpicks the people he sends to the parliament, and the parliament is controlled by the government. So obviously, any names submitted by the president will not be rejected by the parliament. So there’s basically no scrutiny, no oversight in that process. Based on [the commissioners’] performance so far, it looks like they are more concerned about holding onto their jobs than actually doing what they are supposed to do.[175]

Recommendations